The title compound, C13H16N2O4, consists of a six-membered unsaturated ring bound to a five-membered pyrrolidine-2,5-dione ring and N-bound to a six-membered piperidine-2,6-dione ring and thus has the same basic skeleton as thalidomide, except for the six-membered unsaturated ring substituted for the aromatic ring.

Keywords: crystal structure, thalidomide analogs, pseudomerohedral twinning

Abstract

The title compound, C13H16N2O4, crystallizes in the monoclinic centrosymmetric space group, P21/c, with four molecules in the asymmetric unit, thus there is no crystallographically imposed symmetry and it is a racemic mixture. The structure consists of a six-membered unsaturated ring bound to a five-membered pyrrolidine-2,5-dione ring N-bound to a six-membered piperidine-2,6-dione ring and thus has the same basic skeleton as thalidomide, except for the six-membered unsaturated ring substituted for the aromatic ring. In the crystal, the molecules are linked into inversion dimers by R

2

2(8) hydrogen bonding involving the N—H group. In addition, there are bifurcated C—H⋯O interactions involving one of the O atoms on the pyrrolidine-2,5-dione with graph-set notation R

1

2(5). These interactions along with C—H⋯O interactions involving one of the O atoms on the piperidine-2,6-dione ring link the molecules into a complex three-dimensional array. There is pseudomerohedral twinning present which results from a 180° rotation about the [100] reciprocal lattice direction and with a twin law of 1 0 0 0  0 0 0

0 0 0  [BASF 0.044 (1)].

[BASF 0.044 (1)].

Chemical context

Thalidomide (1) is one of the most notorious drugs in pharmaceutical history because of the humanitarian disaster in the 1950s (Burley & Lenz, 1962 ▸; Stephans, 1988 ▸; Bartlett et al., 2004 ▸; Wu et al., 2005 ▸; Melchert & List, 2007 ▸). Thalidomide possesses a single stereogenic carbon in the glutarimide ring, and it is conceivable that the unexpected teratogenic side effects are ascribed to the (S)-enantiomer of 1 (Blaschke et al., 1979 ▸). However, this has been a matter of debate because considerable chiral inversion should take place during the incubation of enantiomerically pure 1 (Nishimura et al., 1994 ▸; Knoche & Blaschke, 1994 ▸; Wnendt et al., 1996 ▸). Despite the tragic disaster, the unique biological properties of 1 prompted its return to the market in the 21st century for the treatment of multiple myeloma and leprosy (Matthews & McCoy, 2003 ▸; Hashimoto et al., 2004 ▸; Franks et al., 2004 ▸; Brennen et al., 2004 ▸; Luzzio et al., 2004 ▸; Sleijfer et al., 2004 ▸; Kumar et al., 2004 ▸; Hashimoto, 2008 ▸; Knobloch & Rüther, 2008 ▸). Furthermore, a large number of papers on novel medical uses of 1 continue to appear in the biological and medicinal literature (Matthews & McCoy, 2003 ▸; Hashimoto et al., 2004 ▸; Franks et al., 2004 ▸; Brennen et al., 2004 ▸; Luzzio et al., 2004 ▸; Sleijfer et al., 2004 ▸; Kumar et al., 2004 ▸; Hashimoto, 2008 ▸; Knobloch & Rüther, 2008 ▸).

Thus, over the years, there has been increasing interest in thalidomide and its derivatives for the treatment of various hematologic malignancies (Singhal et al., 1999 ▸; Raje & Anderson, 1999 ▸), solid tumors (Kumar et al., 2002 ▸), and a variety of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases (Tseng et al., 1996 ▸). Recent studies have uncovered a variety of mechanisms of thalidomide action. It was reported in 1991 that thalidomide is a selective inhibitor of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) production in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulated human monocytes (Moreira et al., 1993 ▸; Sampaio et al., 1991 ▸). TNF-a is a key pro-inflammatory cytokine, and elevated levels have been linked with the pathology of a number of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, aphthous ulcers, cachexia, graft versus host disease, asthma, ARDS and AIDS (Eigler et al., 1997 ▸). Taken together, the immunomodulatory properties of thalidomide, which are dependent on the type of immune cell activated as well as the type of stimulus that the cell receives, provide a rationale for the mechanism of thalidomide action in the context of autoimmune and inflammatory disease states. Other pharmacologic activities of thalidomide include its inhibition of angiogenesis (D’Amato et al., 1994 ▸) and its anti-cancer properties (Bartlett et al., 2004 ▸). In the late 1990′s it was reported that thalidomide is efficacious for the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM), a hematological cancer caused by growth of tumor cells derived from the plasma cells in the bone marrow (Singhal et al., 1999 ▸; Raje & Anderson, 1999 ▸).

A medicinal chemistry program to optimize the immunomodulatory properties of thalidomide and reduce its side-effects led to the discovery of lenalidomide (2), which is a potent immunomodulator that is ∼800 times more potent as an inhibitor of TNF-α in LPS-stimulated hPBMC (Muller et al., 1999 ▸; Zeldis et al., 2011 ▸). In the US, lenalidomide was approved by the FDA in 2005 for low- or intermediate-1-risk myelodysplastic

Structural optimization of thalidomide, 1 also led to the discovery of pomalidomide (3), which is tenfold more potent than lenalidomide as a TNF-a inhibitor and IL-2 stimulator (Muller et al., 1999 ▸; Zeldis et al., 2011 ▸). Pomalidomide is currently undergoing late-stage clinical development for the treatment of multiple myeloma and myeloproliferative neoplasm-associated myelofibrosis (Galustian & Dalgleish, 2011 ▸; Begna et al., 2012 ▸). In clinical trials for multiple myeloma, pomalidomide has been shown to be effective in overcoming resistance to lenalidomide and thalidomide, as well as the proteosome inhibitor bortezomib (Schey & Ramasamy, 2011 ▸).

These studies have shown the efficacy of a continued search for more pharmacologically active analogs of thalidomide and its derivatives. Focus has previously been on modifying the basic thalidomide skeleton by changing its substituents. However, there have been very few studies on related derivatives where the six-membered ring is changed from an aromatic to an unsaturated ring. In view of the wide interest in these types of compounds for their pharmacological activities, the structure of (3aR,7aS)-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)hexahydro-1H-isoindole-1,3(2H)-dione, 4, is reported where the only change to thalidomide is the substitution of an unsaturated six-membered for the aromatic ring.

As a result of this interest in thalidomide, the crystal structure of this molecule in both the racemic and enantiomerically pure forms have been determined multiple times (Lovell, 1970 ▸, 1971 ▸; Reepmeyer et al., 1994 ▸; Allen & Trotter, 1971 ▸; Caira et al., 1994 ▸; Suzuki et al., 2010 ▸; Maeno et al., 2015 ▸). Two polymorphs of the racemic derivative have been determined crystallizing in the space groups P21/n (Allen & Trotter, 1971 ▸; Suzuki et al., 2010 ▸; Maeno et al., 2015 ▸) and P21/c (Lovell, 1970 ▸) or C2/c (Reepmeyer et al., 1994 ▸; Caira et al., 1994 ▸). The crystal packing in the C2/c structure is determined by intermolecular N–H⋯O hydrogen bonding that is more extensive than that reported for the racemate of thalidomide crystallizing in space group P21/n.

Structural commentary

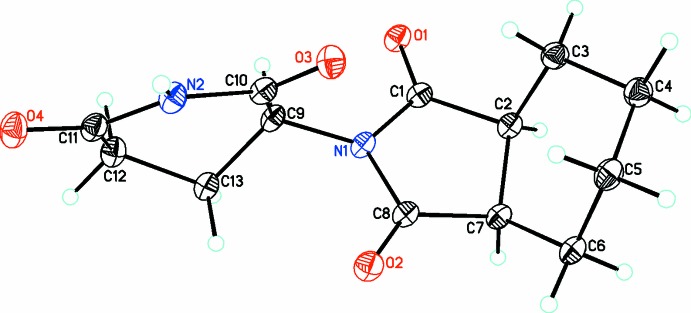

The title compound, C13H16N2O4, 4 (Fig. 1 ▸), crystallizes in the monoclinic centrosymmetric space group, P21/c, with four molecules in the asymmetric unit, thus there is no crystallographically imposed symmetry and it is a racemic mixture. The structure consists of a six-membered unsaturated ring bound to a five-membered pyrrolidine-2,5-dione ring N-bound to a six-membered piperidine-2,6-dione ring and thus has the same basic skeleton as thalidomide, 1, except for the six-membered unsaturated ring substituted for the aromatic ring. In the five-membered pyrrolidine-2,5-dione ring, the atoms O1, C1, N1, C8 and O2 form a plane (r.m.s. deviation of fitted atoms = 0.0348 Å) with C2 and C7 deviating from this plane by −0.186 (7) and 0.219 (7) Å, respectively. The ring itself adopts a conformation in which it is twisted about the C2–C7 axis [P = 257.4 (5) and τ = 22.5 (2); Rao et al., 1981 ▸]. In the six-membered piperidine-2,6-dione ring, the group, O3, C10, N2, C11and O4 is also planar (r.m.s. deviation of fitted atoms = 0.0042 Å). The cyclohexane ring adopts a chair conformation [puckering parameters Q = 0.536 (3), θ = 157.7 (3)° and φ = 324.2 (8)°; Boeyens, 1978 ▸). Otherwise, the metrical parameters for all bonds are in the standard range for such structures.

Figure 1.

The molecular structure of the title compound 4, with the atom-numbering scheme. Atomic displacement parameters are drawn at the 30% probability level.

Supramolecular features

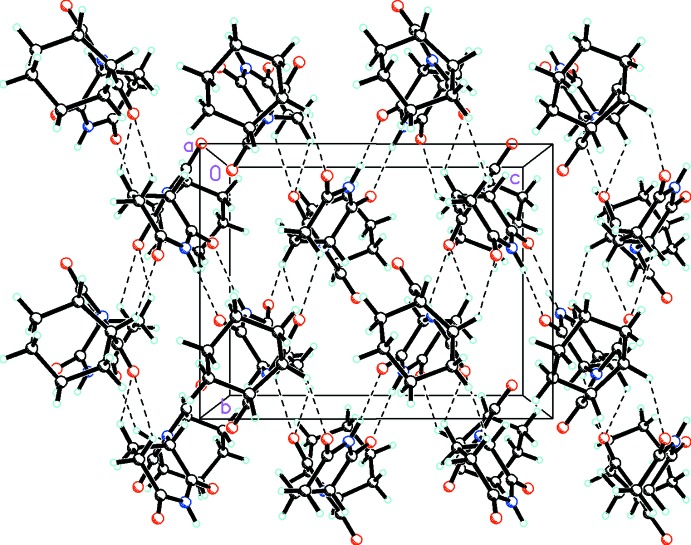

Similarly to the hydrogen-bonding patterns found in both the enantiomerically pure form of thalidomide (Lovell, 1971 ▸; Maeno et al., 2015 ▸) and the racemic P21/n polymorph (Allen & Trotter, 1971 ▸; Suzuki et al., 2010 ▸; Maeno et al., 2015 ▸), the molecules of the title compound are linked into inversion dimers by  (8) (Etter et al., 1990 ▸) hydrogen bonding (Table 1 ▸) involving the N—H group as shown in Fig. 2 ▸. In addition, there are bifurcated C—H⋯O interactions involving O2 with graph-set notation

(8) (Etter et al., 1990 ▸) hydrogen bonding (Table 1 ▸) involving the N—H group as shown in Fig. 2 ▸. In addition, there are bifurcated C—H⋯O interactions involving O2 with graph-set notation  (5). These interactions, along with C—H⋯O interactions involving O4, link the molecules into a complex three-dimensional array.

(5). These interactions, along with C—H⋯O interactions involving O4, link the molecules into a complex three-dimensional array.

Table 1. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °).

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2—H2N⋯O3i | 0.88 (5) | 2.07 (5) | 2.928 (3) | 165 (4) |

| C7—H7A⋯O4ii | 1.00 | 2.42 | 3.150 (3) | 129 |

| C9—H9A⋯O1iii | 1.00 | 2.65 | 3.385 (3) | 130 |

| C12—H12A⋯O2ii | 0.99 | 2.53 | 3.143 (3) | 120 |

| C13—H13A⋯O2 | 0.99 | 2.56 | 3.142 (3) | 118 |

| C13—H13B⋯O2ii | 0.99 | 2.52 | 3.163 (3) | 122 |

Symmetry codes: (i)  ; (ii)

; (ii)  ; (iii)

; (iii)  .

.

Figure 2.

Packing diagram viewed along the a axis showing the extensive N—H⋯O and C—H⋯O interactions (drawn as dashed lines) linking the molecules into a complex three-dimensional array.

Database survey

A search of the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD version 5.39; Groom et al., 2016 ▸) using a skeleton containing the three rings as in thalidomide but without the ketone substituents gave 39 hits but not a single example where the six-membered aromatic ring in the isoindoline moiety is changed to an unsaturated six-membered ring.

Synthesis and crystallization

Some details of the synthesis have been previously reported (Benjamin & Hijji, 2017 ▸). cis-1,2-Cyclohexane dicarboxylic acid anhydride (0.10 g, 0.65 mmol), glutamic acid (0.095 g, 0.65 mmol), DMAP (0.02 g, 0.16 mmol), and ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) (0.040 g, 0.75 mmol) were mixed thoroughly in a CEM-sealed vial with a magnetic stirrer. The sample was heated for 6 min at 423 K in a CEM Discover microwave powered at 150 W. It was then cooled rapidly to 313 K and dissolved in 15 ml of (1:1) ethyl acetate:acetone. The organic layer was washed with 2× 10 ml of distilled water and dried over sodium sulfate (anhydrous). The organic layer was concentrated under vacuum and precipitated with hexanes (30 ml) affording a white solid. Crystals suitable for X-ray experiments were grown by slow evaporation of an ethyl acetate/acetone (1:1) solution. M.p. 463–465 K, (0.12 g, 70%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.0 (s, 1 H, NH), 4.9 (dd, 1 H, 12.5, 5.5 Hz, CHCO), 3.0 (m, 1 H), 2.8 (m, 1 H), 2.8 (m, 1 H), 2.5 (m, 1 H), 1.9 (m, 1 H), 1.7 (m, 3 H),, 1.6 (m, 1 H), 1.4 (m, 4 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) 178.8 (C=O), 178.7 (C=O), 172.7 (C=O), 169.4 (C=O), 48.7 (CH), 39.1 (CH), 38.8 (CH), 30.7 (CH2), 23.1 (CH2), 22.9 (CH2), 21.1 (CH2), 21.05 (CH2), 21.00 (CH2); MS 264 (M +); 236, 210, 179, 154, 112, 82, 67, 54, 41.

Refinement

Crystal data, data collection and structure refinement details are summarized in Table 2 ▸. H atoms were positioned geometrically and treated as riding on their parent atoms and refined with C—H distances of 0.99–1.00 Å and U

iso(H) = 1.2U

eq(C). The H attached to N2 was refined isotropically. There is pseudomerohedral twinning present, which results from a 180° rotation about the [100] reciprocal lattice direction and with a twin law of 1 0 0 0  0 0 0

0 0 0  [BASF 0.044 (1)].

[BASF 0.044 (1)].

Table 2. Experimental details.

| Crystal data | |

| Chemical formula | C13H16N2O4 |

| M r | 264.28 |

| Crystal system, space group | Monoclinic, P21/c |

| Temperature (K) | 123 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 11.4519 (3), 9.2370 (3), 11.8727 (4) |

| β (°) | 90.475 (3) |

| V (Å3) | 1255.87 (7) |

| Z | 4 |

| Radiation type | Cu Kα |

| μ (mm−1) | 0.87 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.42 × 0.34 × 0.18 |

| Data collection | |

| Diffractometer | Rigaku Oxford Diffraction Xcalibur, Ruby, Gemini |

| Absorption correction | Multi-scan (CrysAlis PRO; Rigaku OD, 2012 ▸) |

| T min, T max | 0.822, 1.000 |

| No. of measured, independent and observed [I > 2σ(I)] reflections | 9733, 2626, 2572 |

| R int | 0.024 |

| (sin θ/λ)max (Å−1) | 0.633 |

| Refinement | |

| R[F 2 > 2σ(F 2)], wR(F 2), S | 0.066, 0.208, 1.19 |

| No. of reflections | 2626 |

| No. of parameters | 177 |

| H-atom treatment | H atoms treated by a mixture of independent and constrained refinement |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å−3) | 0.33, −0.35 |

Supplementary Material

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) I. DOI: 10.1107/S2056989018014317/lh5881sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) I. DOI: 10.1107/S2056989018014317/lh5881Isup2.hkl

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2056989018014317/lh5881Isup3.cml

CCDC reference: 1872551

Additional supporting information: crystallographic information; 3D view; checkCIF report

supplementary crystallographic information

Crystal data

| C13H16N2O4 | F(000) = 560 |

| Mr = 264.28 | Dx = 1.398 Mg m−3 |

| Monoclinic, P21/c | Cu Kα radiation, λ = 1.54178 Å |

| a = 11.4519 (3) Å | Cell parameters from 7629 reflections |

| b = 9.2370 (3) Å | θ = 3.7–77.3° |

| c = 11.8727 (4) Å | µ = 0.87 mm−1 |

| β = 90.475 (3)° | T = 123 K |

| V = 1255.87 (7) Å3 | Prism, colorless |

| Z = 4 | 0.42 × 0.34 × 0.18 mm |

Data collection

| Rigaku Oxford Diffraction Xcalibur, Ruby, Gemini diffractometer | 2572 reflections with I > 2σ(I) |

| Detector resolution: 10.5081 pixels mm-1 | Rint = 0.024 |

| ω scans | θmax = 77.5°, θmin = 3.7° |

| Absorption correction: multi-scan (CrysAlisPro; Rigaku OD, 2012) | h = −9→14 |

| Tmin = 0.822, Tmax = 1.000 | k = −10→11 |

| 9733 measured reflections | l = −14→14 |

| 2626 independent reflections |

Refinement

| Refinement on F2 | Primary atom site location: structure-invariant direct methods |

| Least-squares matrix: full | Secondary atom site location: difference Fourier map |

| R[F2 > 2σ(F2)] = 0.066 | Hydrogen site location: mixed |

| wR(F2) = 0.208 | H atoms treated by a mixture of independent and constrained refinement |

| S = 1.19 | w = 1/[σ2(Fo2) + (0.1179P)2 + 1.1244P] where P = (Fo2 + 2Fc2)/3 |

| 2626 reflections | (Δ/σ)max < 0.001 |

| 177 parameters | Δρmax = 0.33 e Å−3 |

| 0 restraints | Δρmin = −0.35 e Å−3 |

Special details

| Geometry. All esds (except the esd in the dihedral angle between two l.s. planes) are estimated using the full covariance matrix. The cell esds are taken into account individually in the estimation of esds in distances, angles and torsion angles; correlations between esds in cell parameters are only used when they are defined by crystal symmetry. An approximate (isotropic) treatment of cell esds is used for estimating esds involving l.s. planes. |

| Refinement. Refined as a two-component twin |

Fractional atomic coordinates and isotropic or equivalent isotropic displacement parameters (Å2)

| x | y | z | Uiso*/Ueq | ||

| O1 | 0.66960 (17) | 0.4309 (2) | 0.56402 (17) | 0.0291 (4) | |

| O2 | 0.67111 (18) | 0.8499 (2) | 0.76606 (18) | 0.0305 (5) | |

| O3 | 0.58392 (17) | 0.8448 (2) | 0.51862 (17) | 0.0299 (5) | |

| O4 | 0.21720 (17) | 0.9000 (2) | 0.64578 (19) | 0.0339 (5) | |

| N1 | 0.64254 (19) | 0.6373 (2) | 0.66901 (18) | 0.0228 (5) | |

| N2 | 0.4008 (2) | 0.8685 (2) | 0.58537 (19) | 0.0263 (5) | |

| H2N | 0.393 (4) | 0.952 (5) | 0.550 (3) | 0.043 (10)* | |

| C1 | 0.7100 (2) | 0.5317 (3) | 0.6160 (2) | 0.0233 (5) | |

| C2 | 0.8368 (2) | 0.5762 (3) | 0.6283 (2) | 0.0240 (5) | |

| H2A | 0.886927 | 0.491448 | 0.648892 | 0.029* | |

| C3 | 0.8713 (2) | 0.6388 (3) | 0.5124 (2) | 0.0288 (6) | |

| H3A | 0.893112 | 0.558146 | 0.461791 | 0.035* | |

| H3B | 0.802837 | 0.688401 | 0.478581 | 0.035* | |

| C4 | 0.9729 (2) | 0.7454 (3) | 0.5201 (2) | 0.0311 (6) | |

| H4A | 1.043151 | 0.695475 | 0.549779 | 0.037* | |

| H4B | 0.990952 | 0.783222 | 0.444218 | 0.037* | |

| C5 | 0.9407 (2) | 0.8704 (3) | 0.5979 (2) | 0.0295 (6) | |

| H5A | 1.003226 | 0.944367 | 0.597275 | 0.035* | |

| H5B | 0.867389 | 0.916344 | 0.571200 | 0.035* | |

| C6 | 0.9248 (2) | 0.8128 (3) | 0.7171 (2) | 0.0278 (6) | |

| H6A | 0.899178 | 0.893048 | 0.766341 | 0.033* | |

| H6B | 1.001037 | 0.777727 | 0.746054 | 0.033* | |

| C7 | 0.8356 (2) | 0.6895 (3) | 0.7240 (2) | 0.0236 (5) | |

| H7A | 0.850009 | 0.636936 | 0.796398 | 0.028* | |

| C8 | 0.7103 (2) | 0.7412 (3) | 0.7241 (2) | 0.0235 (5) | |

| C9 | 0.5186 (2) | 0.6584 (3) | 0.6460 (2) | 0.0236 (5) | |

| H9A | 0.491323 | 0.576348 | 0.597625 | 0.028* | |

| C10 | 0.5061 (2) | 0.7980 (3) | 0.5776 (2) | 0.0239 (5) | |

| C11 | 0.3047 (2) | 0.8261 (3) | 0.6481 (2) | 0.0264 (5) | |

| C12 | 0.3171 (2) | 0.6889 (3) | 0.7153 (2) | 0.0285 (6) | |

| H12A | 0.288711 | 0.606388 | 0.669460 | 0.034* | |

| H12B | 0.267804 | 0.695498 | 0.783153 | 0.034* | |

| C13 | 0.4435 (2) | 0.6608 (3) | 0.7512 (2) | 0.0260 (5) | |

| H13A | 0.470638 | 0.737979 | 0.802975 | 0.031* | |

| H13B | 0.449314 | 0.566826 | 0.790999 | 0.031* |

Atomic displacement parameters (Å2)

| U11 | U22 | U33 | U12 | U13 | U23 | |

| O1 | 0.0298 (9) | 0.0199 (9) | 0.0374 (10) | −0.0011 (7) | −0.0051 (8) | −0.0043 (7) |

| O2 | 0.0306 (10) | 0.0200 (9) | 0.0407 (11) | 0.0001 (7) | −0.0028 (8) | −0.0059 (7) |

| O3 | 0.0280 (10) | 0.0269 (10) | 0.0347 (10) | 0.0042 (7) | 0.0006 (8) | 0.0055 (7) |

| O4 | 0.0266 (9) | 0.0273 (10) | 0.0478 (12) | 0.0052 (8) | −0.0031 (8) | −0.0019 (9) |

| N1 | 0.0226 (10) | 0.0164 (9) | 0.0294 (10) | 0.0004 (8) | −0.0062 (8) | 0.0003 (8) |

| N2 | 0.0260 (11) | 0.0189 (10) | 0.0337 (11) | 0.0043 (8) | −0.0044 (9) | 0.0023 (9) |

| C1 | 0.0265 (12) | 0.0173 (11) | 0.0259 (11) | 0.0017 (9) | −0.0049 (9) | 0.0024 (9) |

| C2 | 0.0245 (11) | 0.0177 (11) | 0.0297 (12) | 0.0005 (9) | −0.0039 (9) | 0.0002 (9) |

| C3 | 0.0297 (13) | 0.0276 (13) | 0.0291 (13) | −0.0027 (10) | −0.0008 (10) | −0.0019 (10) |

| C4 | 0.0306 (13) | 0.0319 (14) | 0.0309 (13) | −0.0046 (11) | −0.0008 (10) | 0.0011 (10) |

| C5 | 0.0286 (13) | 0.0252 (13) | 0.0345 (14) | −0.0050 (10) | −0.0035 (10) | 0.0027 (10) |

| C6 | 0.0250 (12) | 0.0275 (12) | 0.0309 (13) | −0.0053 (10) | −0.0045 (10) | −0.0006 (10) |

| C7 | 0.0240 (11) | 0.0216 (11) | 0.0253 (11) | −0.0020 (9) | −0.0039 (9) | 0.0014 (9) |

| C8 | 0.0250 (11) | 0.0195 (11) | 0.0258 (11) | −0.0010 (9) | −0.0043 (9) | 0.0017 (9) |

| C9 | 0.0219 (11) | 0.0170 (11) | 0.0319 (12) | 0.0015 (8) | −0.0070 (9) | −0.0005 (9) |

| C10 | 0.0253 (11) | 0.0180 (11) | 0.0283 (11) | 0.0021 (9) | −0.0054 (9) | −0.0006 (9) |

| C11 | 0.0242 (12) | 0.0213 (12) | 0.0336 (13) | 0.0007 (9) | −0.0054 (10) | −0.0053 (10) |

| C12 | 0.0245 (12) | 0.0217 (12) | 0.0393 (14) | −0.0016 (9) | −0.0017 (10) | 0.0001 (10) |

| C13 | 0.0239 (12) | 0.0218 (12) | 0.0322 (13) | −0.0007 (9) | −0.0034 (10) | 0.0030 (9) |

Geometric parameters (Å, º)

| O1—C1 | 1.207 (3) | C4—H4B | 0.9900 |

| O2—C8 | 1.208 (3) | C5—C6 | 1.525 (4) |

| O3—C10 | 1.217 (3) | C5—H5A | 0.9900 |

| O4—C11 | 1.213 (3) | C5—H5B | 0.9900 |

| N1—C8 | 1.394 (3) | C6—C7 | 1.532 (3) |

| N1—C1 | 1.397 (3) | C6—H6A | 0.9900 |

| N1—C9 | 1.456 (3) | C6—H6B | 0.9900 |

| N2—C10 | 1.374 (3) | C7—C8 | 1.513 (3) |

| N2—C11 | 1.390 (4) | C7—H7A | 1.0000 |

| N2—H2N | 0.88 (5) | C9—C13 | 1.522 (4) |

| C1—C2 | 1.515 (3) | C9—C10 | 1.531 (3) |

| C2—C7 | 1.544 (3) | C9—H9A | 1.0000 |

| C2—C3 | 1.548 (4) | C11—C12 | 1.503 (4) |

| C2—H2A | 1.0000 | C12—C13 | 1.528 (4) |

| C3—C4 | 1.527 (4) | C12—H12A | 0.9900 |

| C3—H3A | 0.9900 | C12—H12B | 0.9900 |

| C3—H3B | 0.9900 | C13—H13A | 0.9900 |

| C4—C5 | 1.525 (4) | C13—H13B | 0.9900 |

| C4—H4A | 0.9900 | ||

| C8—N1—C1 | 112.6 (2) | C5—C6—H6B | 108.9 |

| C8—N1—C9 | 122.3 (2) | C7—C6—H6B | 108.9 |

| C1—N1—C9 | 123.4 (2) | H6A—C6—H6B | 107.8 |

| C10—N2—C11 | 127.0 (2) | C8—C7—C6 | 113.4 (2) |

| C10—N2—H2N | 118 (3) | C8—C7—C2 | 103.24 (19) |

| C11—N2—H2N | 115 (3) | C6—C7—C2 | 117.1 (2) |

| O1—C1—N1 | 123.9 (2) | C8—C7—H7A | 107.5 |

| O1—C1—C2 | 128.4 (2) | C6—C7—H7A | 107.5 |

| N1—C1—C2 | 107.5 (2) | C2—C7—H7A | 107.5 |

| C1—C2—C7 | 103.9 (2) | O2—C8—N1 | 123.9 (2) |

| C1—C2—C3 | 105.49 (19) | O2—C8—C7 | 128.2 (2) |

| C7—C2—C3 | 113.9 (2) | N1—C8—C7 | 107.8 (2) |

| C1—C2—H2A | 111.1 | N1—C9—C13 | 113.9 (2) |

| C7—C2—H2A | 111.1 | N1—C9—C10 | 107.4 (2) |

| C3—C2—H2A | 111.1 | C13—C9—C10 | 111.9 (2) |

| C4—C3—C2 | 112.8 (2) | N1—C9—H9A | 107.8 |

| C4—C3—H3A | 109.0 | C13—C9—H9A | 107.8 |

| C2—C3—H3A | 109.0 | C10—C9—H9A | 107.8 |

| C4—C3—H3B | 109.0 | O3—C10—N2 | 121.2 (2) |

| C2—C3—H3B | 109.0 | O3—C10—C9 | 122.6 (2) |

| H3A—C3—H3B | 107.8 | N2—C10—C9 | 116.2 (2) |

| C5—C4—C3 | 109.7 (2) | O4—C11—N2 | 119.1 (2) |

| C5—C4—H4A | 109.7 | O4—C11—C12 | 124.1 (3) |

| C3—C4—H4A | 109.7 | N2—C11—C12 | 116.8 (2) |

| C5—C4—H4B | 109.7 | C11—C12—C13 | 112.1 (2) |

| C3—C4—H4B | 109.7 | C11—C12—H12A | 109.2 |

| H4A—C4—H4B | 108.2 | C13—C12—H12A | 109.2 |

| C6—C5—C4 | 109.2 (2) | C11—C12—H12B | 109.2 |

| C6—C5—H5A | 109.8 | C13—C12—H12B | 109.2 |

| C4—C5—H5A | 109.8 | H12A—C12—H12B | 107.9 |

| C6—C5—H5B | 109.8 | C9—C13—C12 | 108.3 (2) |

| C4—C5—H5B | 109.8 | C9—C13—H13A | 110.0 |

| H5A—C5—H5B | 108.3 | C12—C13—H13A | 110.0 |

| C5—C6—C7 | 113.2 (2) | C9—C13—H13B | 110.0 |

| C5—C6—H6A | 108.9 | C12—C13—H13B | 110.0 |

| C7—C6—H6A | 108.9 | H13A—C13—H13B | 108.4 |

| C8—N1—C1—O1 | 179.5 (2) | C9—N1—C8—C7 | −174.9 (2) |

| C9—N1—C1—O1 | −15.2 (4) | C6—C7—C8—O2 | −34.8 (4) |

| C8—N1—C1—C2 | −5.3 (3) | C2—C7—C8—O2 | −162.5 (3) |

| C9—N1—C1—C2 | 160.0 (2) | C6—C7—C8—N1 | 147.1 (2) |

| O1—C1—C2—C7 | −167.9 (2) | C2—C7—C8—N1 | 19.4 (3) |

| N1—C1—C2—C7 | 17.2 (2) | C8—N1—C9—C13 | −67.6 (3) |

| O1—C1—C2—C3 | 72.0 (3) | C1—N1—C9—C13 | 128.4 (2) |

| N1—C1—C2—C3 | −102.9 (2) | C8—N1—C9—C10 | 56.9 (3) |

| C1—C2—C3—C4 | 155.2 (2) | C1—N1—C9—C10 | −107.1 (3) |

| C7—C2—C3—C4 | 41.9 (3) | C11—N2—C10—O3 | 179.1 (2) |

| C2—C3—C4—C5 | −58.7 (3) | C11—N2—C10—C9 | −0.4 (4) |

| C3—C4—C5—C6 | 64.9 (3) | N1—C9—C10—O3 | 25.9 (3) |

| C4—C5—C6—C7 | −55.2 (3) | C13—C9—C10—O3 | 151.6 (2) |

| C5—C6—C7—C8 | −80.1 (3) | N1—C9—C10—N2 | −154.6 (2) |

| C5—C6—C7—C2 | 40.0 (3) | C13—C9—C10—N2 | −28.9 (3) |

| C1—C2—C7—C8 | −21.7 (2) | C10—N2—C11—O4 | −179.6 (2) |

| C3—C2—C7—C8 | 92.6 (2) | C10—N2—C11—C12 | 0.4 (4) |

| C1—C2—C7—C6 | −147.1 (2) | O4—C11—C12—C13 | −151.1 (3) |

| C3—C2—C7—C6 | −32.8 (3) | N2—C11—C12—C13 | 28.9 (3) |

| C1—N1—C8—O2 | 172.5 (2) | N1—C9—C13—C12 | 178.0 (2) |

| C9—N1—C8—O2 | 6.9 (4) | C10—C9—C13—C12 | 55.9 (3) |

| C1—N1—C8—C7 | −9.4 (3) | C11—C12—C13—C9 | −56.1 (3) |

Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, º)

| D—H···A | D—H | H···A | D···A | D—H···A |

| N2—H2N···O3i | 0.88 (5) | 2.07 (5) | 2.928 (3) | 165 (4) |

| C7—H7A···O4ii | 1.00 | 2.42 | 3.150 (3) | 129 |

| C9—H9A···O1iii | 1.00 | 2.65 | 3.385 (3) | 130 |

| C12—H12A···O2ii | 0.99 | 2.53 | 3.143 (3) | 120 |

| C13—H13A···O2 | 0.99 | 2.56 | 3.142 (3) | 118 |

| C13—H13B···O2ii | 0.99 | 2.52 | 3.163 (3) | 122 |

Symmetry codes: (i) −x+1, −y+2, −z+1; (ii) −x+1, y−1/2, −z+3/2; (iii) −x+1, −y+1, −z+1.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by National Science Foundation, Directorate for Mathematical and Physical Sciences grant 1205608 to R. J. Butcher. Qatar National Research Fund grant NPRP 7-495-1-094 to Y. Hijji.

References

- Allen, F. H. & Trotter, J. (1971). J. Chem. Soc. B, pp. 1073–1079.

- Bartlett, J. B., Dredge, K. & Dalgleish, A. G. (2004). Nat. Rev. Cancer, 4, 314–322. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Begna, K., Pardanani, A., Mesa, R., Litzow, M., Hogan, W., Hanson, C. & Tefferi, A. (2012). Am. J. Hematol. 87, 66–68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, E. & Hijji, Y. M. (2017). J. Chem. pp. 1–6.

- Blaschke, G., Kraft, H. P., Fickentscher, K. & Köhler, F. (1979). Arzneim.-Forsch. 29, 1640–1642. [PubMed]

- Boeyens, J. C. A. (1978). J. Cryst. Mol. Struct. 8, 317–320.

- Brennen, W. N., Cooper, C. R., Capitosti, S., Brown, M. L. & Sikes, R. A. (2004). Clin. Prostate Cancer, 3, 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Burley, D. M. & Lenz, W. (1962). Lancet, 279, 271–272.

- Caira, M. R., Botha, S. A. & Flanagan, D. R. (1994). J. Chem. Crystallogr. 24, 95–99.

- D’Amato, R. J., Loughnan, M. S., Flynn, E. & Folkman, J. (1994). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 4082–4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Eigler, A., Sinha, B., Hartmann, G. & Endres, S. (1997). Immunol. Today, 18, 487–492. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Etter, M. C., MacDonald, J. C. & Bernstein, J. (1990). Acta Cryst. B46, 256–262. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Franks, M. E., Macpherson, G. R. & Figg, W. D. (2004). Lancet, 363, 1802–1811. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Galustian, C. & Dalgleish, A. (2011). Drugs Fut. 36, 741–750.

- Groom, C. R., Bruno, I. J., Lightfoot, M. P. & Ward, S. C. (2016). Acta Cryst. B72, 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, Y. (2008). Arch. Pharm. Chem. Life Sci. 341, 536–547.

- Hashimoto, Y., Tanatani, A., Nagasawa, K. & Miyachi, H. (2004). Drugs Fut. 29, 383–391.

- Knobloch, J. & Rüther, U. (2008). Cell Cycle, 7, 1121–1127. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Knoche, B. & Blaschke, G. (1994). J. Chromatogr. A, 666, 235–240.

- Kumar, S., Witzig, T. E. & Rajkumar, S. V. (2002). J. Cell. Mol. Med. 6, 160–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S., Witzig, T. E. & Rajkumar, S. V. (2004). J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 2477–2488. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lovell, F. M. (1970). ACA Abstr. Papers (Winter), 30.

- Lovell, F. M. (1971). ACA Abstr. Papers (Summer), 36.

- Luzzio, F. A. & Figg, W. D. (2004). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 14, 215–229.

- Maeno, M., Tokunaga, E., Yamamoto, T., Suzuki, T., Ogino, Y., Ito, E., Shiro, M., Asahi, T. & Shibata, N. (2015). Chem. Sci. 6, 1043–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Matthews, S. J. & McCoy, C. (2003). Clin. Ther. 25, 342–395. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Melchert, M. & List, A. (2007). Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 1489–1499. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Moreira, A. L., Sampaio, E. P., Zmuidzinas, Z., Frindt, P., Smith, K. A. & Kaplan, G. J. (1993). Exp. Med, 177, 1675–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Muller, G., Chen, R., Huang, S.-Y., Corral, L., Wong, L., Patterson, R., Chen, Y., Kaplan, G. & Stirling, D. (1999). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 9, 1625–1630. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, K., Hashimoto, Y. & Iwasaki, S. (1994). Chem. Pharm. Bull. 42, 1157–1159. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Raje, N. & Anderson, K. (1999). N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 1606–1609. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rao, S. T., Westhof, E. & Sundaralingam, M. (1981). Acta Cryst. A37, 421–425.

- Reepmeyer, J. C., Rhodes, M. O., Cox, D. C. & Silverton, J. V. (1994). J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, pp. 2063–2067.

- Rigaku OD (2012). CrysAlis PRO. Rigaku Oxford Diffraction, Yarnton, England.

- Sampaio, E. P., Sarno, E. N., Galilly, R., Cohn, Z. A. & Kaplan, G. (1991). J. Exp. Med, 173, 699–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schey, S. & Ramasamy, K. (2011). Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs, 20, 691–700. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2008). Acta Cryst. A64, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2015). Acta Cryst. C71, 3–8.

- Singhal, S., Mehta, J., Desikan, R., Ayers, D., Roberson, P., Eddlemon, P., Munshi, N., Anaissie, E., Wilson, C., Dhodapkar, M., Zeldis, J., Siegel, D., Crowley, J. & Barlogie, B. (1999). N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 1565–1571. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sleijfer, S., Kruit, W. H. J. & Stoter, G. (2004). Eur. J. Cancer, 40, 2377–2382. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Stephans, T. D. (1988). Teratology, 38, 229–239. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T., Tanaka, M., Shiro, M., Shibata, N., Osaka, T. & Asahi, T. (2010). Phase Transit. 83, 223–234.

- Tseng, S., Pak, G., Washenik, K., Pomeranz, M. K. & Shupack, J. L. (1996). J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 35, 969–979. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wnendt, S., Finkam, M., Winter, W., Ossig, J., Raabe, G. & Zwingenberger, K. (1996). Chirality, 8, 390–396. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wu, J. J., Huang, D. B., Pang, K. R., Hsu, S. & Tyring, S. K. (2005). Br. J. Dermatol. 153, 254–273. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zeldis, J., Knight, R., Hussein, M., Chopra, R. & Muller, G. (2011). Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1222, 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) I. DOI: 10.1107/S2056989018014317/lh5881sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) I. DOI: 10.1107/S2056989018014317/lh5881Isup2.hkl

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2056989018014317/lh5881Isup3.cml

CCDC reference: 1872551

Additional supporting information: crystallographic information; 3D view; checkCIF report