Abstract

Background—

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), the first line of therapy for preventing sudden cardiac death in high-risk patients, deliver appropriate shocks for termination of ventricular tachycardia (VT)/ventricular fibrillation. A common shortcoming of ICDs is imperfect rhythm discrimination, resulting in the delivery of inappropriate shocks for atrial fibrillation (AF). An underexplored area for rhythm discrimination is the difference in dynamic properties between AF and VT/ventricular fibrillation. We hypothesized that the higher entropy of rapid cardiac rhythms preceding ICD shocks distinguishes AF from VT/ventricular fibrillation.

Methods and Results—

In a multicenter, prospective, observational study of patients with primary prevention ICDs, 119 patients received shocks from ICDs with stored, retrievable intracardiac electrograms. Blinded adjudication revealed shocks were delivered for VT/ventricular fibrillation (62%), AF (23%), and supraventricular tachycardia (15%). Entropy estimation of only 9 ventricular intervals before ICD shocks accurately distinguished AF (receiver operating characteristic curve area, 0.98; 95% confidence intervals, 0.93–1.0) and outperformed contemporary ICD rhythm discrimination algorithms.

Conclusions—

This new strategy for AF discrimination based on entropy estimation expands on simpler concepts of variability, performs well at fast heart rates, and has potential for broad clinical application.

Keywords: defibrillators, implantable, tachycardia, ventricular, ventricular fibrillation, death, sudden, cardiac, ECG, nonlinear dynamics, inappropriate shock, entropy

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) and ventricular fibrillation (VF) are lethal cardiac arrhythmias, claiming a quarter million lives per year from sudden cardiac death (SCD).1 Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), the first line of therapy for preventing SCD, deliver appropriate shocks for termination of VT/VF.2,3 A common shortcoming of ICDs is inadequate rhythm discrimination, resulting in the delivery of inappropriate shocks for non–life-threatening arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation (AF).

Clinical Perspective on p 561

Even with optimal ICD programming and contemporary technological advances,4–15 about one third of ICD recipients receive inappropriate shocks for AF.15–24 Inappropriate shocks are painful, are associated with substantial psychological stress, decrease quality of life, can initiate more dangerous arrhythmias, and may increase mortality.15,22–25 Minimizing inappropriate shocks, while maintaining high sensitivity for detecting VT/VF, is an essential attribute of - contemporary ICDs.

An underexplored opportunity for rhythm discrimination in patients with ICD is the difference in dynamic properties of AF and VT/VF. In AF, complexities of atrial activation and decremental impulse conduction through the atrioventricular node produce a highly irregular rhythm. As a result, the time series for ventricular activation approaches white noise. In most cases, this sharply differs from arrhythmias that arise from diseased ventricular myocardium.

One approach to characterize this distinctive difference is to measure the information entropy, a concept of uncertainty related to thermodynamic entropy.26 In this context, entropy is fundamentally different from conventional measures of heart rate variability (HRV) in that entropy exploits information on the ordering of the times between ventricular activation and quantifies the degree to which self-similar fluctuation patterns repeat. These self-similar fluctuations are indistinguishable in moment statistics and frequency domain measures of HRV.

We hypothesized that the entropy of rapid cardiac rhythms immediately preceding ICD shocks discriminates AF from VT/VF. We directly compared performances of entropy estimation with those of representative discrimination algorithms used in contemporary ICDs.

Materials and Methods

Adjudicated Rhythm Groups

The intracardiac electrogram data were drawn from a multicenter, prospective cohort of patients with dual- or single-chamber ICDs implanted for primary prevention of SCD. We studied patients with ischemic or nonischemic heart failure, ejection fraction ≤35%, New York Heart Association class I to III symptoms, and no history of VT/VF or SCD. Patients with secondary prevention indication, New York Heart Association class IV heart failure, permanent pacemaker, or pre-existing Class 1 indication for permanent pacemaker were not included in this cohort.

This study includes 119 consecutive patients, who received ICDs equipped with intracardiac electrogram storage that were retrieved for rhythm discrimination and analysis. The ICDs were manufactured by Medtronic (Minneapolis, MN), Boston Scientific (Natick, MA), and St. Jude Medical (St. Paul, MN). During the implant procedure, sensing, pacing, and defibrillation thresholds were tested as per standard protocol. ICDs were programmed at the discretion of the implanting physicians. High VT/VF cutoff zones were encouraged and supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) discriminator algorithms could be enabled. The ICDs were reprogrammed by the treating physician when considered clinically indicated (eg, hemodynamic well-tolerated VT and VT in monitor zone). The electrogram and interval data were downloaded from ICDs using proprietary software obtained from the manufacturers. The entropy calculations were performed offline as described below.

After each shock or after death, all available information, including electrograms before the shock, was reviewed by a committee of ≥3 board-certified clinical cardiac electrophysiologists. The committee blindly adjudicated the type of arrhythmia eliciting the shock (eg, VT, VF, SVT, and AF) and whether the shock was appropriate or inappropriate. An inappropriate shock was defined as an episode that started with a shock not delivered for VT or VF and ended when sinus rhythm was detected. If a patient received repetitive inappropriate shocks for the same rhythm, only the electrogram responsible for the first shock was analyzed. Causes of inappropriate shocks were categorized as SVT (including sinus tachycardia), AF (including atrial flutter), or artifact. Although the categorization of atrial flutter as AF diminished performance estimates, it reflects the common clinical situation in which these arrhythmias often coexist in the same patient populations and share underlying substrates, mechanisms, and management strategies.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating centers (Johns Hopkins University, University of Maryland, Washington Hospital Center, and Virginia Commonwealth University). All patients provided written informed consent.

Entropy Estimation

We optimized the sample entropy27,28 measure and developed the coefficient of sample entropy (COSEn)29 for the specific purpose of AF discrimination in electrograms at all heart rates using very short time series of ventricular activation.

An illustration of the COSEn calculation is provided in the Methods in the online-only Data Supplement. Briefly, sample entropy is the conditional probability that 2 short templates of length m that match within an arbitrary tolerance r will continue to match at the next point m+1. Mathematically expressed, SampEn=ln(A/B), where A denotes ΣAi (total number of matches of length m+1) and B denotes ΣBi (total number of matches of length m+1 and m), in a series of n consecutive intervals, x1, x2,…,xn, where the record may be as short as n=9. By allowing r to vary for sufficient matches and confident entropy estimation, conversion of the final probability to a density by dividing by the matching region volume, and correcting for the mean heart rate, the optimized sample entropy estimate was defined as COSEn. Unlike approximate entropy,26 frequency domain measures, or geometric measures, such as Poincaré plots,30 COSEn is accurate in very short time series.

AF Discrimination

For each patient, entropy analysis was performed only for the episode resulting in the first shock. The adjudicated ICD shock rhythms were considered the gold standard for rhythm diagnosis and compared with AF discrimination based on entropy estimation. Entropy values higher than a threshold (COSEn>−1.20) for 9 consecutive ventricular activation intervals preceding a shock were classified as AF. This threshold was preselected in a prior Holter database29 such that the proportion of AF misclassified as non-AF was equal to the proportion of non-AF misclassified as AF.31 Entropy estimation was also performed on all the electrograms, and intervals of the stored event and analysis of >9 consecutive intervals did not alter the accuracy of detection.

The diagnostic performance of entropy estimation was compared with that of standard metrics of heart rate, HRV, and stability calculated from the same 9 intervals. The heart rate was determined from the mean interval. The coefficient of variation (SD of the intervals divided by the mean) is a common measure of HRV. Stability, another measure of variability, is indexed as the trimmed range (ie, next-tolongest minus next-to-shortest intervals, and therefore, large values indicate less stable rhythms).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were compared using t test and categorical variables were compared using χ2 test. The ability of entropy, stability, HRV, and heart rate to discriminate AF was evaluated using the receiver operating characteristic curve area. We also calculated the sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratios, and predictive probabilities for detecting AF for standard cutoffs of each metric (COSEn≥−1.20; stability≥30 ms; HRV≥0.10; heart rate<180 beats per minute). Logistic regression was used to evaluate whether stability, HRV, or heart rate provided any added discrimination with respect to entropy. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Adjudicated Rhythm Groups

In a multicenter, prospective, observational study of patients with primary prevention ICDs, we identified 119 consecutive patients, who received shocks from ICDs with stored retrievable intracardiac electrograms. Blinded adjudication by expert clinical cardiac electrophysiologists revealed almost half of the shocks delivered were not for VT/VF and AF was responsible for two thirds of these inappropriate shocks (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Adjudicated Rhythm Groups

| AF | SVT | VT | VF | Not AF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients, n | 27 | 18 | 60 | 14 | 92 |

| Age, y | 66±11 | 58±15 | 62±11 | 58±14 | 61±13 |

| Male, % | 81 | 61 | 70 | 50 | 65 |

| Black | 26 | 50 | 20 | 7 | 24 |

| Previous AF | 22 | 17 | 12 | 21 | 14 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 52 | 44 | 62 | 43 | 55 |

| Ejection fraction | 24±11 | 18±7 | 23±8 | 18±10 | 21±8 |

| NYHA | |||||

| Class I | 7* | 33 | 27 | 21 | 27 |

| Class II | 19 | 28 | 27 | 29 | 27 |

| Class III | 74‡ | 39 | 47 | 50 | 46 |

| Dual chamber ICD | 63 | 44 | 38 | 64 | 43 |

| Heart rate, beats per minute | 185±26† | 170±28 | 218±48 | 255±82 | 214±57 |

| HRV (coefficient of variation) | 0.15±0.060§ | 0.015±0.0085 | 0.067±0.10 | 0.086±0.13 | 0.060±0.099 |

| Stability, ms | 87±33§ | 11±8 | 27±60 | 28±52 | 24±53 |

| Entropy (COSEn) | −0.82±0.53§ | −3.2±0.71 | −2.5±0.73 | −2.5±0.88 | −2.7±0.79 |

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; COSEn, coefficient of sample entropy; HRV, heart rate variability; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; VF, ventricular fibrillation; and VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Continuous (mean±SD) and categorical (%) variables were compared between AF and non-AF groups:

P=0.03

P=0.01

P=0.009

P<0.0001.

Interestingly, ICD rhythm discrimination algorithms were enabled in 50% of patients that received AF-induced inappropriate shocks, suggesting half of these AF rhythms had either eluded the discriminators or another algorithm superseded the discriminators to command delivery of a shock. The respective ICD program settings for the AF versus non-AF groups were as follows: VF zone cutoff 191±14 versus 197±14; lowest rate cutoff 167±23 versus 173±22; enabled morphology discriminator algorithms 26% versus 25%; enabled onset algorithms (17% versus 13%); enabled stability algorithms 15% versus 13%; ventricular sensitivity 0.279±0.0139 versus 0.273±0.00932; 1 zone programmed 41% versus 37%; and 2 zones 30% versus 37%; 3 zones 19% versus 9%. Although it is an appealing idea that sensed information from an atrial lead can be used to reduce inappropriate shocks, the presence (63%) or absence of a right atrial lead did not affect the inappropriate shock rate, consistent with previous studies.17,32,33

AF Discrimination

We used a novel, conceptually simple strategy for AF discrimination on the basis of entropy estimation29 of electrograms. Entropy estimation of only 9 intervals of ventricular activation (within ≈3 seconds) accurately distinguished AF from VT/VF. We directly compared performances of entropy estimation with those of representative rhythm discrimination algorithms routinely used in contemporary ICDs. Compared with VT/VF, the AF records had lower heart rate, higher HRV, reduced stability, and higher entropy (Table 1). Analysis of >9 intervals of ventricular activation did not affect the results.

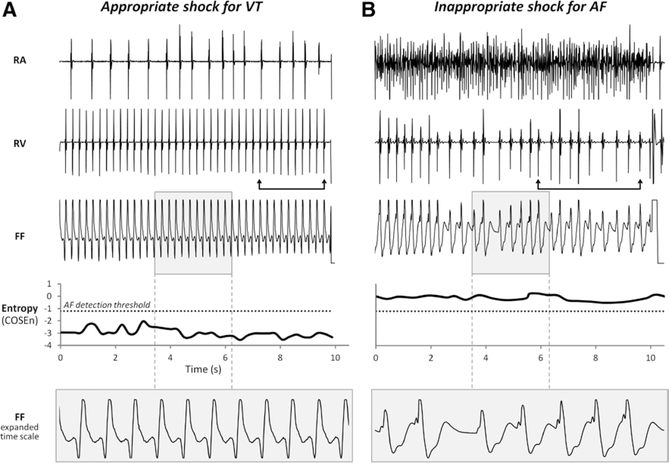

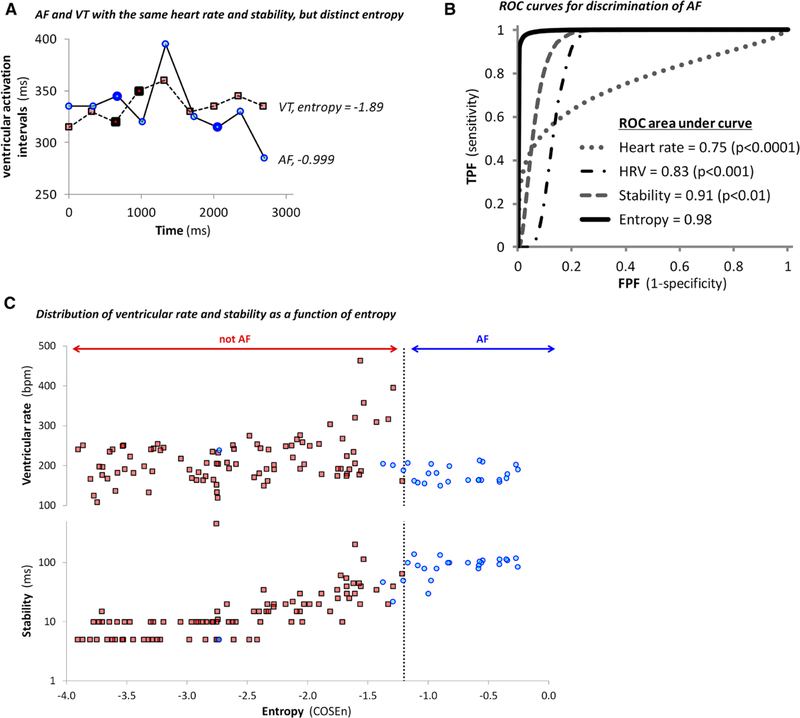

Figure 1 shows illustrative electrograms responsible for an appropriate shock for VT (Figure 1A) and an inappropriate shock for AF (Figure 1B). At all times, the entropy values accurately identified the adjudicated rhythms. Although these rhythms were also discernible on the basis of rate, stability, and morphology of the atrial and ventricular electrograms, other AF and VT/VF records were distinguishable only by entropy (Figure 2A). However, there were no examples of rhythms with comparable entropy and significantly different stabilities in the entire data set.

Figure 1.

Representative preshock electrograms and corresponding entropy values. Bipolar electrograms from right atrial (RA) and right ventricular (RV) leads, unipolar far field (FF) electrograms, plots of entropy values, and an expanded view of the FF electrograms from 2 patients are shown. The bipolar electrograms were recorded from 2 poles in close proximity within the same lead. In contrast, FF electrograms were recorded using an active unipolar lead in the RV and an indifferent electrode outside the heart, and reflect electric activity from a larger portion of the ventricle, similar to surface ECG tracings. The dotted line represents the entropy threshold for atrial fibrillation (AF) detection. The arrows indicate the RV electrogram segment of 9 intervals immediately preceding the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shock that was used for the rhythm discrimination analyses. A, Data from a patient who received an appropriate shock for ventricular tachycardia (VT). The RV rate exceeded the RA rate and the FF electrogram demonstrated a similar morphology among beats. At all times, the entropy values accurately indicated VT/ventricular fibrillation. B, Data from a patient who received an inappropriate shock for AF. The RA electrogram exhibited AF. The ICD was programmed to deliver a shock for heart rates >190 beats per minute. The entropy values consistently indicated AF.

Figure 2.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) discrimination. A, Representative examples of AF and ventricular tachycardia (VT) with identical average heart rates (180 beats per minute) and stabilities (30 ms). These values are similar to the discrimination thresholds used in routine clinical practice. The ventricular activation intervals measured at the right ventricular lead are plotted >3 seconds preceding implantable cardioverter-defibrillators shocks in 2 patients. Shocks were delivered for AF (blue circles) and for VT (red squares). The stability of the 9 ventricular activation intervals preceding each shock was calculated as the trimmed range using the differences in the intervals indicated by the bold symbols. Although the AF and VT were indistinguishable on the basis of stability and heart rate, the entropy of AF (−0.999) was significantly higher than that of the VT (−1.89). B, The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for discrimination of AF from supraventricular tachycardia/VT/ventricular fibrillation by heart rate, heart rate variability (HRV), stability, and entropy. The ROC area under curve (95% confidence interval) for entropy, stability, HRV, and heart rate were 0.98 (0.93–1.0), 0.91 (0.83–0.99; P<0.01 compared with entropy), 0.83 (0.74–0.92; P<0.001), and 0.75 (0.65–0.84; P<0.0001), respectively. C, Plots of ventricular rate (top) and stability (bottom, log10 scale), as a function of entropy for AF (blue circles) and other rhythms (red squares). Although the AF records had a larger stability value (87±33 ms) than other rhythms (24±53; P<0.0001), there was considerable overlap between groups. The HRV in AF was also higher (0.15±0.060 ms) than others (0.060±0.099; P<0.0001), but with even more overlap (data not shown). The ventricular rates in AF were lower (185±26 beats per minute) than others (214±57; P=0.01) but exhibited substantial overlap. The high entropy values of the AF records (−0.82±0.53) set them apart from other rhythms (−2.7±0.79; P<0.0001) more clearly than the range of distribution of stability, HRV, or heart rate.

The high entropy of AF most clearly distinguished this rhythm from VT/VF with receiver operating characteristic curve area of 0.98 (Figure 2B). In a plot of ventricular rate and stability as a function of entropy, the only outlier in the AF group with lower entropy was atrial flutter with 2:1 conduction block to the ventricles (Figure 2C). Although this diminished performance estimates, AF and atrial flutter were grouped together to reflect the typical clinical setting more accurately in which their diagnosis and management often overlap.

Because missing even a single VT/VF episode is potentially fatal, programming a highly sensitive cutoff for AF without compromising VT/VF detection is a practical clinical challenge. On the basis of thresholds commonly used in clinical practice, heart rate, HRV, and stability correctly identified only ≤85% of the non-AF cases (Table 2). In contrast, entropy correctly identified 100% of the non-AF cases using an objectively predetermined threshold. Entropy estimation was also the best AF detector in this data set. In logistic regression analyses, heart rate, HRV, and stability did not improve AF discrimination compared with entropy estimation alone (P>0.3).

Table 2.

AF Discrimination Using Standard Thresholds

| Discriminator Threshold | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Likelihood Ratio | Negative Likelihood Ratio | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate, beats per minute, <180 | 48 (29–68) | 74 (64–84) | 1.9 (1.1–3.1) | 0.70 (0.48–1.03) | 35 (20–53) | 83 (73–90) |

| HRV (coefficient of variation) >0.10 | 85 (66–96) | 85(76–91) | 5.6 (3.4–9.3) | 0.18 (0.072–0.43) | 62 (45–76) | 95 (88–99) |

| Stability, ms >30 | 89 (71–98) | 85(76–91) | 5.8 (3.5–9.6) | 0.13 (0.045–0.38) | 63 (46–78) | 96 (90–99) |

| Entropy (COSEn) >-1.2 | 85 (66–96) | 100 (96–100) | 156 (9.8–2489) | 0.16 (0.069–0.38) | 100 (85–100) | 96 (90–99) |

Sensitivity is the proportion of correct diagnoses of AF among shocks for AF and specificity is the proportion of correct diagnoses of non-AF rhythms among shocks not for AF. Values within brackets are 95% confidence intervals. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; COSEn, coefficient of sample entropy; and HRV, heart rate variability.

Discussion

In this consecutive series of patients with primary prevention ICDs, almost half of the ICD shocks delivered were not for VT/VF and AF was responsible for two thirds of these inappropriate shocks. The ICD firing rates in this cohort are similar to those reported in randomized clinical trials, such as SCD–Heart Failure Trial3 and lower than those reported in Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II.2,19 This novel strategy for discriminating AF from VT/VF based on entropy estimation of 9 ventricular beats from intracardiac electrograms was highly accurate, efficient, and performed well at fast heart rates. Entropy estimation exhibited better rhythm discrimination ability than representative algorithms used in contemporary ICDs.

Entropy estimation has potential for not only reducing inappropriate ICD shocks, but also other clinical applications. AF, the most common sustained arrhythmia and particularly frequent in patients with heart disease, is often asymptomatic and carries a substantially increased stroke risk.34 Diagnosis of asymptomatic AF remains a challenge34 (eg, in patients with single-chamber pacemakers and ICDs).35,36 About 50% of patients with pacemakers have undiagnosed AF,36 but no current single-chamber implantable device reports the amount of time in AF or the AF burden. In addition, knowing the amount of time a patient has AF can guide important clinical decisions (eg, anticoagulation management). Because AF detection based on entropy estimation is conceptually simple and computationally efficient, it may be applied to patients with implantable devices and for screening patients at high risk for development of AF and its complications.

There are some clinical situations, though, in which entropy estimation will be an imperfect AF discriminator. For example, entropy estimation will not distinguish AF from atrial flutter with variable atrioventricular block, but it can distinguish atrial flutter with fixed atrioventricular block, which has much lower entropy. In this study, all types of atrial flutter were categorized as AF. Despite the different dynamics, atrial flutter has a similar clinical profile as AF and is a limitation in entropy analysis for AF detection.

VF or polymorphic forms of VT with very fast ventricular rates may have higher entropy than monomorphic VT and overlap with the high entropy of AF. Because of a finite sampling rate or reconstitution of electrograms stored at lower resolution, the measurement precision of times between ventricular activations decreases at extremely high heart rates and measured intervals may be limited to a small range of values, resulting in more uniform entropy estimates and the possibility of mistaking very fast AF for VT/VF. However, ventricular arrhythmias at even the highest rates and variability had lower entropy than AF in this large data set (Figure 2C). Regardless, even if the discriminatory ability of entropy were to be reduced at extremely high heart rates, this would have little practical impact because the default for most ICDs is to deliver therapy to avoid undertreating potentially lethal arrhythmias.

We compared entropy estimation with representative metrics of stability and HRV used in SVT discriminators of contemporary ICDs. Although other variants of stability are used by different ICD manufacturers, they are mathematically similar and do not seem to affect the incidence of inappropriate shocks.11,15–17,19–21,32,33 Heart rate is the primary determinant for delivery of therapy by ICDs and thus is a surrogate for rhythm discrimination. Recent comparisons of sophisticated discrimination algorithms have demonstrated only a small reduction in inappropriate shocks that was attributed primarily to incorporation of a heart rate cutoff of at least 175 beats per minute.16

The relatively small number of AF cases in this study increased the risk of statistical overfitting of data. Although entropy estimation had a high predictive accuracy for AF detection in 24-hour Holter surface ECG recordings,29 this study is restricted to shorter duration intracardiac electrograms retrieved for rhythm analysis after an ICD shock and as such cannot provide performance estimates for any episodes longer than the electrogram recordings. The performance estimates for entropy did not change over the duration of the electrogram recordings. Additional studies with larger sample sizes and longer electrogram recordings are necessary to validate these findings prospectively and to provide more reliable estimates of discrimination parameters for entropy compared with those used in contemporary ICDs. Because the computational cost for entropy calculation is low, entropy can be continuously monitored by ICDs for the duration of the tachycardia. Like all such measures, entropy estimation is not intended to function alone, and implementation with other rhythm detection features or criteria (eg, rate, sustained high rate) should maximize discrimination accuracy.

How does entropy estimation differ from conventional measures of HRV? Although thermodynamic entropy relates to the distribution of a system among its substates, the information entropy of a time series is often characterized as uncertainty, complexity, disorder, or unpredictability. Entropy estimation is fundamentally different from measures of irregularity or HRV in that it measures the degree to which self-similar heart rate fluctuation patterns repeat. In premature infants, entropy estimation has proven important in early detection of sepsis and reducing mortality.37 We now find that applying entropy estimation for discriminating nonlethal from lethal cardiac arrhythmias is efficient and highly accurate at fast heart rates, where rapid decisions about high voltage shocks must be made. The long-held and fundamental principle that measuring the dynamics of human rhythms can improve healthcare holds true in this life-saving cardiac therapy.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia in man. The consequences of inadequate AF detection are a major public health concern and pose a significant societal burden. Despite recent advances in technology and rhythm discrimination strategies, about one third of patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) receive inappropriate shocks for AF, a nonlethal arrhythmia that does not require such aggressive therapy. Inappropriate shocks are painful, associated with substantial psychological stress, decrease quality of life, can initiate more dangerous arrhythmias, and may increase mortality. Minimizing inappropriate shocks while maintaining high sensitivity for detecting lethal ventricular arrhythmias is an essential attribute of contemporary ICDs. The authors introduce a novel nonlinear strategy for discriminating AF from lethal ventricular arrhythmias on the basis of entropy estimation of very short intracardiac electrogram records from ICDs (ie, 9 heart beats). Entropy performs well at very fast heart rates and requires only 2 to 3 seconds for highly accurate AF discrimination. Entropy estimation fundamentally differs from conventional measures of heart rate variability used in contemporary ICDs to make therapeutic decisions in that entropy quantifies the degree to which heart rate fluctuation patterns repeat themselves. These self-similar fluctuations are indistinguishable in moment statistics and frequency domain measures. Entropy estimation is conceptually simple, computationally straightforward, and easily applicable in ICDs, telemetry monitors, and ambulatory settings. The new paradigm of characterizing short-term human physiological dynamics by their entropy has potential for broad clinical application.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Daniel Hecker (St. Jude Medical), Ward Stephenson Jr (Medtronic), and Allen Wish (Boston Scientific) for providing software for retrieval of intracardiac electrograms. We gratefully acknowledge Barbara Butcher, Sanaz Norgard, Deborah Disilvestre, and Solmaz Masoudi for managing Prospective Observational Study of Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators.

Disclosures

This work was supported by the Donald W. Reynolds Cardiovascular Clinical Center at the Johns Hopkins University, National Institutes Health HL R01 091062 (Dr Tomaselli), and, in part, by an American Heart Association Mid-Atlantic grant-in-aid at the University of Virginia (Dr Moorman). Dr Cheng has received significant consulting fees/honoraria from Biotronik, St. Jude Medical, and modest consulting fees/ honoraria from Medtronic. The other authors have no conflict to report.

References

- 1.Chugh SS, Reinier K, Teodorescu C, Evanado A, Kehr E, Al Samara M, Mariani R, Gunson K, Jui J. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death: clinical and research implications. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;51:213–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Brown MW, Andrews ML; Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II Investigators. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, Domanski M, Troutman C, Anderson J, Johnson G, McNulty SE, Clapp-Channing N, Davidson-Ray LD, Fraulo ES, Fishbein DP, Luceri RM, Ip JH; Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) Investigators. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saeed M, Razavi M, Neason CG, Petrutiu S. Rationale and design for programming implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in patients with primary prevention indication to prolong time to first shock (PROVIDE) study. Europace. 2011;13:1648–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo R, Al-Ahmad A, Hsia H, Zei PC, Wang PJ. Optimal programming of ICDs for prevention of appropriate and inappropriate shocks. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2008;10:408–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein GJ, Gillberg JM, Tang A, Inbar S, Sharma A, Unterberg-Buchwald C, Dorian P, Moore H, Duru F, Rooney E, Becker D, Schaaf K, Benditt D; Worldwide Wave Investigators. Improving SVT discrimination in single-chamber ICDs: a new electrogram morphology-based algorithm. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:1310–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh SN, Poole J, Anderson J, Hellkamp AS, Karasik P, Mark DB, Lee KL, Bardy GH; SCD-HeFT Investigators. Role of amiodarone or implantable cardioverter/defibrillator in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Am Heart J. 2006;152:974.e7–e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams JL, Shusterman V, Saba S. A pilot study examining the performance of polynomial-modeled ventricular shock electrograms for rhythm discrimination in implantable devices. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:930–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dash S, Chon KH, Lu S, Raeder EA. Automatic real time detection of atrial fibrillation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2009;37:1701–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins SL, Lee RS, Kramer RL. Stability: an ICD detection criterion for discriminating atrial fibrillation from ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1995;6:1081–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kühlkamp V, Dörnberger V, Mewis C, Suchalla R, Bosch RF, Seipel L. Clinical experience with the new detection algorithms for atrial fibrillation of a defibrillator with dual chamber sensing and pacing. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999;10:905–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukunami M, Yamada T, Ohmori M, Kumagai K, Umemoto K, Sakai A, Kondoh N, Minamino T, Hoki N. Detection of patients at risk for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation during sinus rhythm by P wave-triggered signalaveraged electrocardiogram. Circulation. 1991;83:162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tateno K, Glass L. Automatic detection of atrial fibrillation using the coefficient of variation and density histograms of RR and deltaRR intervals. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2001;39:664–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang C, Ye S, Chen H, Li D, He F, Tu Y. A novel method for detection of the transition between atrial fibrillation and sinus rhythm. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2011;58:1113–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Rees JB, Borleffs CJ, de Bie MK, Stijnen T, van Erven L, Bax JJ, Schalij MJ. Inappropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks: incidence, predictors, and impact on mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold MR, Ahmad S, Browne K, Berg KC, Thackeray L, Berger RD. Prospective comparison of discrimination algorithms to prevent inappropriate ICD therapy: primary results of the Rhythm ID Going Head to Head Trial. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sweeney MO. Overcoming the defects of a virtue: dual-chamber versus single-chamber detection enhancements for implantable defibrillator rhythm diagnosis: the detect supraventricular tachycardia study. Circulation. 2006;113:2862–2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koneru JN, Swerdlow CD, Wood MA, Ellenbogen KA. Minimizing inappropriate or “unnecessary” implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:778–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daubert JP, Zareba W, Cannom DS, McNitt S, Rosero SZ, Wang P, Schuger C, Steinberg JS, Higgins SL, Wilber DJ, Klein H, Andrews ML, Hall WJ, Moss AJ; MADIT II Investigators. Inappropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks in MADIT II: frequency, mechanisms, predictors, and survival impact. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1357–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman PA, McClelland RL, Bamlet WR, Acosta H, Kessler D, Munger TM, Kavesh NG, Wood M, Daoud E, Massumi A, Schuger C, Shorofsky S, Wilkoff B, Glikson M. Dual-chamber versus single-chamber detection enhancements for implantable defibrillator rhythm diagnosis: the detect supraventricular tachycardia study. Circulation. 2006;113:2871–2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saeed M, Neason CG, Razavi M, Chandiramani S, Alonso J, Natarajan S, Ip JH, Peress DF, Ramadas S, Massumi A. Programming antitachycardia pacing for primary prevention in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators: results from the PROVE trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:1349–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Germano JJ, Reynolds M, Essebag V, Josephson ME. Frequency and causes of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapies: is device therapy proarrhythmic? Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1255–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stempniewicz P, Cheng A, Connolly A, Wang XY, Calkins H, Tomaselli GF, Berger RD, Tereshchenko LG. Appropriate and inappropriate electrical therapies delivered by an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: effect on intracardiac electrogram. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011;22:554–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poole JE, Johnson GW, Hellkamp AS, Anderson J, Callans DJ, Raitt MH, Reddy RK, Marchlinski FE, Yee R, Guarnieri T, Talajic M, Wilber DJ, Fishbein DP, Packer DL, Mark DB, Lee KL, Bardy GH. Prognostic importance of defibrillator shocks in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1009–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sears SF, Lewis TS, Kuhl EA, Conti JB. Predictors of quality of life in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pincus SM, Goldberger AL. Physiological time-series analysis: what does regularity quantify? Am J Physiol. 1994;266(4 Pt 2):H1643–H1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richman JS, Lake DE, Moorman JR. Sample entropy. Methods Enzymol. 2004;384:172–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richman JS, Moorman JR. Physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H2039–H2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lake DE, Moorman JR. Accurate estimation of entropy in very short physiological time series: the problem of atrial fibrillation detection in implanted ventricular devices. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H319–H325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation. 1996;93:1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colquhoun D, Sakmann B. Fast events in single-channel currents activated by acetylcholine and its analogues at the frog muscle end-plate. J Physiol. 1985;369:501–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olshansky B, Day JD, Moore S, Gering L, Rosenbaum M, McGuire M, Brown S, Lerew DR. Is dual-chamber programming inferior to singlechamber programming in an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator? Results of the INTRINSIC RV (Inhibition of Unnecessary RV Pacing With AVSH in ICDs) study. Circulation. 2007;115:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deisenhofer I, Kolb C, Ndrepepa G, Schreieck J, Karch M, Schmieder S, Zrenner B, Schmitt C. Do current dual chamber cardioverter defibrillators have advantages over conventional single chamber cardioverter defibrillators in reducing inappropriate therapies? A randomized, prospective study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:134–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Gold MR, Israel CW, Van Gelder IC, Capucci A, Lau CP, Fain E, Yang S, Bailleul C, Morillo CA, Carlson M, Themeles E, Kaufman ES, Hohnloser SH; ASSERT Investigators. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orlov MV, Ghali JK, Araghi-Niknam M, Sherfesee L, Sahr D, Hettrick DA; Atrial High Rate Trial Investigators. Asymptomatic atrial fibrillation in pacemaker recipients: incidence, progression, and determinants based on the atrial high rate trial. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30:404–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Defaye P, Dournaux F, Mouton E. Prevalence of supraventricular arrhythmias from the automated analysis of data stored in the DDD pacemakers of 617 patients: the AIDA study. The AIDA Multicenter Study Group. Automatic Interpretation for Diagnosis Assistance. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;21(1 Pt 2):250–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moorman JR, Carlo WA, Kattwinkel J, Schelonka RL, Porcelli PJ, Navarrete CT, Bancalari E, Aschner JL, Whit Walker M, Perez JA, Palmer C, Stukenborg GJ, Lake DE, Michael O’Shea T. Mortality reduction by heart rate characteristic monitoring in very low birth weight neonates: a randomized trial. J Pediatr. 2011;159:900–906.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]