Abstract

Background

A high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a marker of systemic inflammation and together with the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) is associated with worse outcomes in several solid tumors. We investigated the prognostic value of NLR and PLR in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) treated with primary or adjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy ((C)RT).

Methods

A retrospective chart review of consecutive patients with HNSCC was performed. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and PLR were computed using complete blood counts (CBCs) performed within 10 days before treatment start. The prognostic role of NLR and PLR was evaluated with univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses adjusting for disease-specific prognostic factors. NLR and PLR were assessed as log-transformed continuous variables (log NLR and log PLR). Endpoints of interest were overall survival (OS), locoregional recurrence-free survival (LRFS), distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS), and acute toxicity.

Results

We analyzed 186 patients treated from 2007 to 2010. Primary sites were oropharynx (45%), oral cavity (28%), hypopharynx (14%), and larynx (13%). Median follow-up was 49 months. Higher NLR was associated with OS (adjusted HR per 1 unit higher log NLR = 1.81 (1.16–2.81), p = 0.012), whereas no association could be shown with LRFS (HR = 1.49 (0,83-2,68), p = 0.182), DRFS (HR = 1.38 (0.65–3.22), p = 0.4), or acute toxicity grade ≥ 2. PLR was not associated with outcome, nor with toxicity.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that in HNSCC patients treated with primary or adjuvant (C)RT, NLR is an independent predictor of mortality, but not disease-specific outcomes or toxicity. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a readily available biomarker that could improve pre-treatment prognostication and may be used for risk-stratification.

Keywords: Head and neck, Squamous cell carcinoma, Inflammation, Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, Toxicity

Background

Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) poses an important challenge [1]. Currently, some of the widely used factors are smoking and human papillomavirus (HPV) status, age, performance status, and tumor stage. Nomograms based on baseline characteristics can enhance prognostic prediction [2].

Inflammation is a hallmark of cancer [3], which is shown to play an important role in tumor development and progression [4–6]. An elevation of circulating neutrophil count is thought to be the result of tumor cells releasing cytokines, which stimulate the bone marrow to produce neutrophils [7–9]. Cytokines released by neutrophils also promote angiogenesis leading to tumor growth and metastasis [10–15]. There is an increasing interest in the use of hematological parameters as prognostic factors in malignancies. Neutrophil, lymphocyte, and platelet counts, either as individual values or in relation to each other, could be associated with the cancer prognosis [16, 17]. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is an emerging marker of host inflammation, which reflects the relation between circulating neutrophil and lymphocyte counts. It can be easily calculated from routine complete blood counts (CBCs) with differentiation. The independent prognostic value of NLR has been shown for a variety of solid malignancies [17–20]. In addition to NLR, the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) has also been shown to be a potential prognostic factor [2, 19]. Several studies involving HNSCC have shown an association between inflammation and worse prognosis [21–27]. However, information about the possible value of pretreatment NLR or PLR on toxicity is limited [18–29].

In this study, we retrospectively evaluated the prognostic impact of pretreatment NLR and PLR on oncological outcomes and toxicity in HNSCC patients treated with primary or adjuvant curative-intended (chemo-) radiotherapy ((C)RT). We hypothesized that elevated NLR and/or PLR are associated with detrimental survival; we also explored NRL and PLR associations with acute treatment-related toxicity since it has prognostic value in primary and adjuvant (C)RT for HNSCC [30, 31].

Methods

Patient selection

Medical records of HNSCC patients consecutively treated with primary or adjuvant curative-intent intensity-modulated radiation therapy with or without concomitant systemic therapy between January 2007 and December 2010 at the Department of Radiation Oncology, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital were retrospectively analyzed. Patients diagnosed with oral cavity (OCC), oropharynx (OC), hypopharynx (HC) and laryngeal cancers (LC) were included in the analysis. History of another malignancy within 5 years of diagnosis, prior radiation to the head and neck, non-squamous cell carcinoma histology, distant metastases, lack of differentiated CBC within 10 days before oncologic surgery or RT start, and early abortion of RT were defined as exclusion criteria. This study was approved by the local ethics committee (289/2014).

Treatment and follow-up

The standard treatment was based on institutional policies following the multidisciplinary tumor board decision as previously published [32, 33]. All cases were presented at the weekly institutional interdisciplinary head-and-neck tumor board. After completion of staging examinations and final TNM staging (AJCC), selection of treatment modalities and treatment sequencing were defined. The standard treatment in OCC was to perform surgery followed by adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) [30, 32], while in OC, HC and LC the joint recommendations of the multidisciplinary meeting was primary RT [31, 33]. Case-based decisions were made concerning the use of concomitant systemic therapy and up-front neck dissection. The delivery of radiotherapy, the definition of clinical target volume (CTV) and planned target volume (PTV) followed departmental guidelines [32, 33] based on international recommendations [34–36]. All treatment plans were contoured and calculated using Eclipse treatment planning system (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA). The standard concomitant therapy consisted of cisplatin 100 mg/m2 day 1 in three-week intervals for all patients. In few cases of induction chemotherapy, cisplatin, docetaxel, and 5-fluorouracil were used. Patients not deemed medically fit for cisplatin chemotherapy because of pre-existing co-morbidities were evaluated for weekly treatment with monoclonal antibody cetuximab [37] or carboplatin three weekly. Pre-treatment CBC with differential values was used to calculate NLR and PLR.

Potential causes of changes in the CBC (e.g. infection, steroid use) were identified, and patients were excluded from the analysis. Patients were regularly followed, and toxicities were graded according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.03 (https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf).

Statistical analysis

NLR was calculated by dividing absolute neutrophil count by absolute lymphocyte count measured in peripheral blood. PLR was calculated by dividing absolute thrombocyte count by absolute lymphocyte count. Due to its non-normal distribution, NLR and PLR were loge-transformed to obtain symmetric distributions and then analyzed as continuous variables. Frequencies and percentages are reported for categorical variables, medians with range or interquartile range for continuous variables. The primary endpoint of the study was overall survival (OS), and the secondary endpoints were locoregional relapse-free survival (LRFS) and distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS). Time-to-event was calculated for OS, LRFS, and DRFS from the start of RT to death (OS), locoregional relapse (LRFS), and distant recurrence (DRFS), respectively, with censoring of patients without such events at last follow up. Median times to event were estimated using the Kaplan Meier method. The prognostic value of NLR and PLR, and other variables (i.e. age, gender, smoking status, Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), UICC stage, tumor grade, hemoglobin level) were assessed by univariable Cox regression analysis. Subsequently, multivariable analysis with forward elimination was planned with inclusion of all variables with a p-value < 0.05 in the univariable analysis. The association of NLR and PLR with acute and late toxicities (i.e. pain, dermatitis, mucositis, dysphagia, xerostomia) was examined using logistic regression. Analyses were carried out using SPSS version 23 (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL). The threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and no correction for multiple testing was performed.

Results

Patients

One hundred and eighty-six patients were included in the study. Patients’ and disease characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of patients were male and in good performance status (KPS ≥ 70). The primary tumor was located in the oral cavity or oropharynx in approximately 75% of the cases, and more than half of all patients had UICC stage IVA or IVB disease. Median NLR and PLR were 3.28 and 189, respectively. There was a statistically significant correlation between NLR and PLR (Spearman’s rho = 0.65, p < 0.001). Baseline NLR and PLR were not associated with gender, smoking status, site of the primary tumor, stage of disease or tumor grade.

Table 1.

Patients’ and disease characteristics

| Age | |

| median (range), years | 61 (41–88) |

| ≤ 60, N (%) | 86 (46) |

| > 60 to ≤70, N (%) | 64 (34) |

| > 70 to ≤80, N (%) | 27 (15) |

| > 80, N (%) | 9 (5) |

| Gender, N (%) | |

| female | 40 (22) |

| male | 146 (79) |

| Smoking status | |

| never smoker | 17 (6) |

| previous smoker | 33 (31) |

| current smoker | 58 (54) |

| missing | 108 |

| High risk alcohol consumption | |

| No | 49 (46) |

| Yes | 54 (51) |

| in the past | 4 (4) |

| missing | 79 |

| Karnofsky Performance Status | |

| median (range) | 90 (50–100) |

| > 70, N (%) | 160 (86) |

| ≤ 70, N (%) | 26 (14) |

| Oncological resection of primary tumor | |

| yes | 56 (30) |

| no | 130 (70) |

| Induction chemotherapy | |

| yes | 15 (8) |

| no | 171 (92 |

| Concomitant systemic therapy | |

| no | 38 (20) |

| cisplatin or carboplatin | 125 (67) |

| cetuximab | 23 (12) |

| Site of primary tumor, N (%) | |

| oral cavity | 52 (28) |

| oropharynx | 83 (45) |

| hypopharynx | 27 (15) |

| larynx | 24 (13) |

| UICC stage, N (%) | |

| I | 5 (3) |

| II | 11 (6) |

| III | 44 (24) |

| IV | 126 (68) |

| Tumor grade, N (%) | |

| G1 | 1 (1) |

| G2 | 113 (61) |

| G3 | 72 (39) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | |

| median (IQR) | 13.3 (12.0–14.4) |

| missing | 12 |

| Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio | |

| median (IQR) | 3.28 (2.15–4.70) |

| missing | 20 |

| Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio | |

| median (IQR) | 189 (136–254) |

| missing | 20 |

IQR inter-quartile range, UICC Union for International Cancer Control

Overall survival

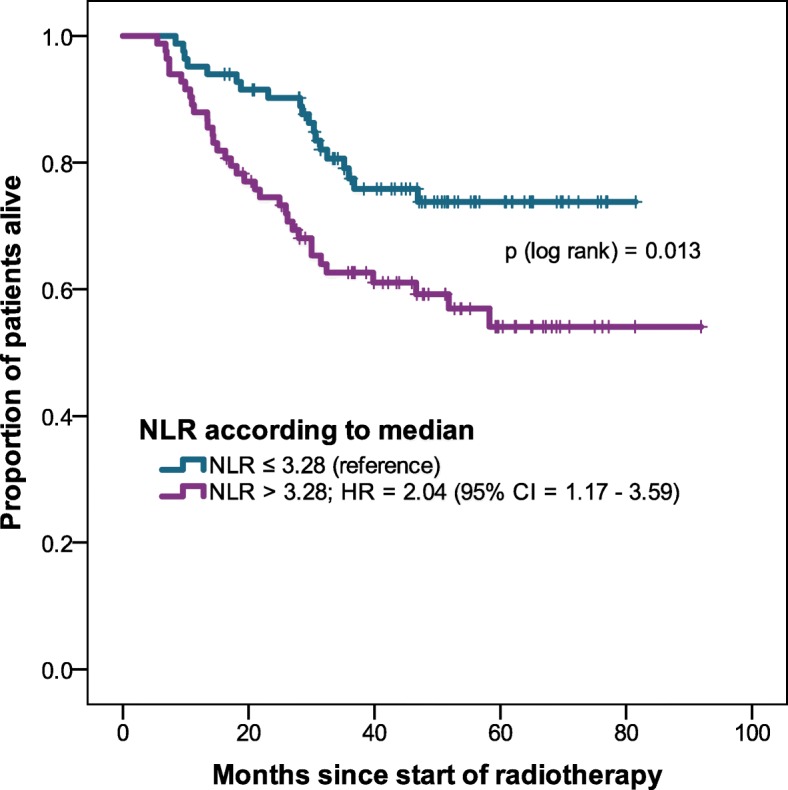

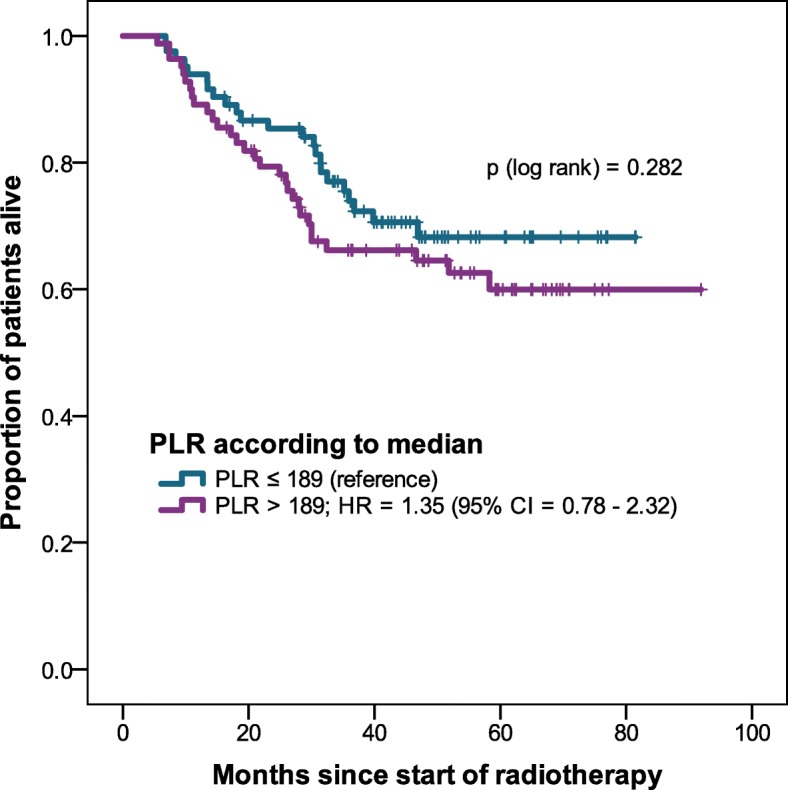

At a median follow-up time of 40 months, 60 patients (32%) died; median OS was not reached. Higher NLR was associated with lower OS (Table 2). When dividing the population into two groups according to the median NLR, there was a significant OS difference between the groups (Fig. 1). For PLR there was a non-significant association between higher PLR and lower OS (Fig. 2). On univariable analysis loge NLR was associated with OS. Also, older age, worse Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS ≤ 70), and UICC stage IV were associated with lower OS. Performance status, UICC stage IV and loge NLR remained of prognostic value in multivariable analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis of overall survival

| univariable analysis | multivariable analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Age | per 10 years older | 1.32 (1.03–1.69) | 0.026* | ||

| Gender | male (vs. female) | 1.17 (0.61–2.25) | 0.639 | ||

| Smoking status | never smoker (vs. current/past) | 0.66 (0.20–2.19) | 0.492 | ||

| Karnofsky Performance Status | per 10 higher | 0.76 (0.62–0.92) | 0.005* | 0.76 (0.62–0.98) | 0.030* |

| UICC stage | IVA-B (vs. I-III) | 1.87 (1.01–3.47) | 0.045* | ||

| Tumor grade | G3 (vs. G1-G2) | 0.91 (0.54–1.54) | 0.731 | ||

| Hemoglobin | per 1 g/dL higher | 0.89 (0.77–1.04) | 0.143 | ||

| log NLR | per 1 log NLR higher | 1.81 (1.16–2.81) | 0.009* | 1.58 (1.01–2.47) | 0.043* |

| log PLR | per 1 log PLR higher | 1.62 (0.99–2.63) | 0.054 | ||

CI confidence interval, G tumor grade, HR hazard ratio, log NLR natural logarithm of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, log PLR natural logarithm of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, UICC Union for International Cancer Control; *statistically significant

Fig. 1.

Overall survival of NLR higher than median vs. equal or lower than median

Fig. 2.

Overall survival of PLR higher than median vs. equal or lower than median

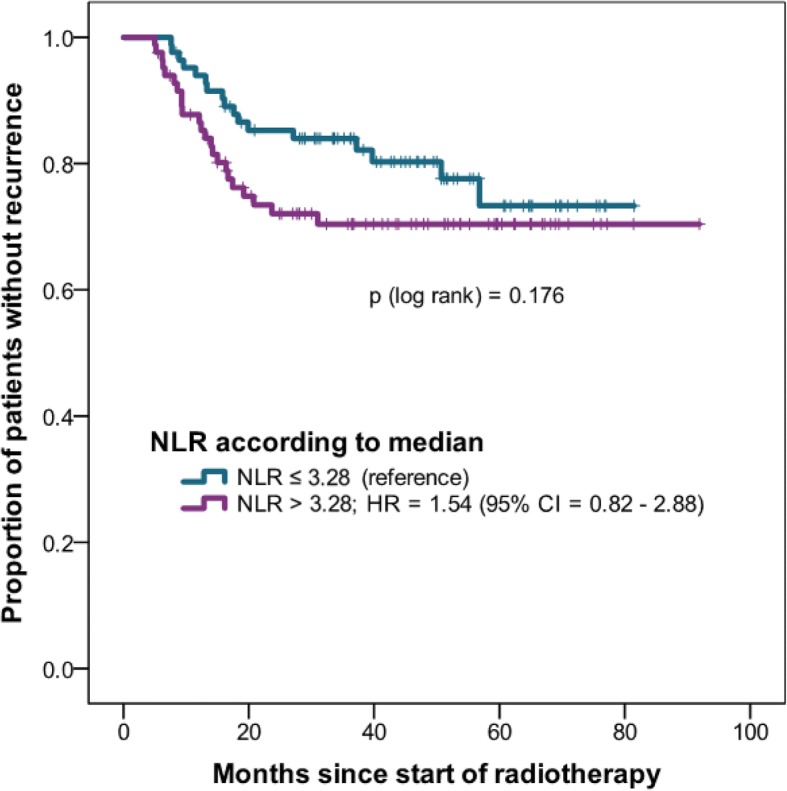

Recurrence

Of the variables tested, only UICC stage IV was associated with increased loco-regional, distant, and any recurrence rate, whereas no association was found for all other variables tested (Table 3). Consequently, no multivariable analyses were conducted. In patients with high NLR, recurrences occurred earlier, but the correlation was not statistically significant (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Univariable Cox regression analysis of recurrence

| Univariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Loco-regional recurrence (38 events) | |||

| Age | per 10 years older | 1.08 (0.80–1.48) | 0.607 |

| Gender | male vs. female | 1.21 (0.53–2.75) | 0.648 |

| Smoking status | never smoker (vs. current/past) | 1.68 (0.34–8.31) | 0.526 |

| Karnofsky Performance Status | KPS over 70 | 0.55 (0.23–1.35) | 0.191 |

| UICC stage | IVA-B (vs. I-III) | 3.43 (1.34–8.78) | 0.010* |

| Tumor grade | G3 (vs. G1-G2) | 0.78 (0.40–1.53) | 0.477 |

| Hemoglobin | per 1 g/dL higher | 0.92 (0.76–1.13) | 0.424 |

| log NLR | per 1 log NLR higher | 1.49 (0.83–2.68) | 0.182 |

| log PLR | per 1 log PLR higher | 1.65 (0.88–3.10) | 0.117 |

| Distant recurrence (20 events) | |||

| Age | per 10 years older | 0.77 (0.49–1.22) | 0.272 |

| Gender | male | 2.48 (0.57–10.7) | 0.224 |

| Smoking status | never smoker (vs. current/past) | 0.04 (0.00–22.86) | 0.314 |

| Karnofsky Performance Status | KPS over 70 | 2.53 (0.34–18.94) | 0.367 |

| UICC stage | IV (vs. I-III) | 9.91 (1.33–74.03) | 0.025* |

| Tumor grade | G3 (vs. lower) | 1.53 (0.64–3.68) | 0.342 |

| Hemoglobin | per 1 g/dL higher | 1.11 (0.84–1.46) | 0.472 |

| log NLR | per 1 log NLR higher | 1.38 (0.65–2.91) | 0.400 |

| log PLR | per 1 log PLR higher | 1.44 (0.65–3.22) | 0.371 |

| Any recurrence (46 events) | |||

| Age | per 10 years older | 1.04 (0.78–1.28) | 0.779 |

| Gender | male | 1.30 (0.61–2.79) | 0.501 |

| Smoking status | never smoker (vs. current/past) | 0.60 (014–2.63) | 0.501 |

| Karnofsky Performance Status | KPS over 70 | 0.74 (0.33–1.65) | 0.457 |

| Localization | larynx or hypopharynx (vs. other) | 1.24 (0.66–2.33) | 0.497 |

| UICC stage | IV (vs. I-III) | 3.49 (1.48–8.24) | 0.004* |

| Tumor grade | G3 (vs. G1-G2) | 0.96 (0.53–1.74) | 0.891 |

| Hemoglobin | per 1 g/dL higher | 0.95 (0.79–1.14) | 0.948 |

| log NLR | per 1 log NLR higher | 1.49 (0.88–2.53) | 0.134 |

| log PLR | per 1 log PLR higher | 1.55 (0.88–2.74) | 0.128 |

CI confidence interval, G tumor grade, HR hazard ratio, log NLR natural logarithm of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, log PLR natural logarithm of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, UICC Union for International Cancer Control; *statistically significant

Fig. 3.

Recurrence-free survival of NLR higher than median vs. equal or lower than median

Toxicity

Rates and grades of the most common acute toxicities are summarized in Table 4. There was no correlation between baseline NLR or PLR and the grade of toxicity (data not shown).

Table 4.

Selected toxicities of 183 patients (toxicities of 3 patients missing)

| G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms prior to radiotherapy | ||||

| Pain | 52 (28) | 30 (16) | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Dysphagia | 52 (28) | 32 (17) | 11 (6) | 0 |

| Acute toxicities | ||||

| Pain | 42 (23) | 91 (49) | 45 (24) | 1 (1) |

| Dermatitis | 44 (24) | 117 (63) | 22 (12) | 0 |

| Mucositis | 31 (17) | 110 (59) | 40 (22) | 0 |

| Dysphagia | 23 (12) | 80 (43) | 70 (38) | 1 (1) |

| Xerostomia | 63 (34) | 8 (4) | 0 | 0 |

Grades according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.03

Discussion

NLR is the object of numerous previously published studies. Not only in oncology but also in other disciplines, blood counts reflecting the complexity of the immune system can be easily obtained at low costs, which may impact daily clinical practice. About 15–20% of all cancer deaths worldwide seem to be associated with underlying infections and inflammatory reactions [38]. Many triggers of chronic inflammation increase the risk of developing cancer. These triggers, for example, include microbial infections such as Helicobacter pylori (associated with stomach cancer), inflammatory bowel disease (associated with bowel cancer) and prostatitis (associated with prostate cancer) [38]. Despite conflicting studies, treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents has been associated with reduced cancer incidence and mortality [38–41]. Increased NLR is associated with poorer outcomes in many solid tumors, be it early or advanced stage cancer [17]. An early decrease in NLR may be associated with more favorable outcomes and higher response rates [42], whereas an increase in NLR in the first weeks of treatment had the opposite effect [42].

In this study with a relatively large cohort of HNSCC patients treated with (C)RT with curative intention, an elevated NLR at baseline was associated with a shorter OS but not with disease recurrence or toxicities. Our findings of a negative prognostic role of NLR are in accordance with other studies [26, 43] that have investigated NLR in HNSCC. In contrast to our results, Rassouli et al. [44] have demonstrated a statistically significant impact of PLR on OS. Worth to note, such associations were observed at various cut-offs in different studies. They have also shown that an increased NLR was not only associated with decreased OS but with higher recurrence rates too [44]; which was not shown in our cohort and another study from the United Kingdom [45].

Along with the increased NLR in malignant disease, a possible explanation for a lower OS could also be a cause of death not attributable to cancer, but other co-morbidities such as a cardiac cause where it could also be shown that an increased NLR is predictive for cardiac mortality [46]. It is also known that smokers have a “smoker’s leukocytosis” [37, 38, 47, 48]. In our cohort, most patients are at least ex-smokers (80%), and at least one third continued smoking during and after radiation. Therefore, it is possible that the patients with a smoker’s leukocytosis have died earlier from smoking-related comorbidities [49].

Several limitations to our study should be considered. First, this was a retrospective analysis with possible selection bias and confounding variables. We included 16 patients (9%) with early-stage disease and 15 (8%) patients who had neoadjuvant chemotherapy, which may have introduced some heterogeneity to our cohort. Second, we were unable to capture data on HPV status systematically. Studies have shown an important interaction between HPV status, immunomodulation and clinical outcome [50]. Therefore, there might be different results in HPV-associated and unassociated tumors [51]. Since this is a retrospective study, there might be unknown causes of CBC changes that have not been identified. Beside patient and tumor-specific factors which may influence the complex cascades of the immune system, it must also be noted that despite clinical benefit, the dichotomization or grouping of continuous variables in statistical analysis is accompanied by a loss of the statistical power. To account for this, NLR and PLR were analyzed as (log-transformed) continuous variables. Lastly, an overestimation of statistical significance due to multiple testing is possible. Although these results should be validated in other cohorts, we reproduced some of the previously reported studies [26, 43] on the interface of systemic inflammatory pathways and OS. Therefore, we provide data on surrogate values for inflammation as predictors of clinical outcomes; however, a causal relationship and its impact on tumor aggressiveness or tumor microenvironment warrants further investigation.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that in HNSCC patients treated with primary or adjuvant (C)RT, NLR is an independent predictor of OS. NLR is a readily available biomarker that could improve pre-treatment risk stratification.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Andreas Geretschläger and Dr. Michael Schmücking for their collaboration with the clinical data.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- (C)RT

(Chemo)radiotherapy

- CBCs

Complete blood counts

- CI

Confidence interval

- DRFS

Distant recurrence-free survival

- G

Tumor grade

- HC

Hypopharyngeal cancer

- HNSCC

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IQR

Inter-quartile range

- LC

Laryngeal cancer

- log NLR

Natural logarithm of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- log PLR

Natural logarithm of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

- LRFS

Locoregional recurrence-free survival

- NLR

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- OC

Oropharyngeal cancer

- OCC

Oral cavity cancer

- OS

Overall survival

- PLR

Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

- RT

Radiotherapy

- UICC

Union for International Cancer Control

Authors’ contributions

Each author had participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content. AD, BB, and AT designed the study. AT performed the statistical analysis. BB collected the data and together with AT, KZ, OE, MW, MS, RG, and DMA interpreted the results. The manuscript was written by BB, AD and AT, and all other authors reviewed and finally approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients provided written consent for the use of their medical data for research purposes. Approval of the regional ethics committee (Kantonale Ethikkommission Bern – 289/2014) was obtained.

Consent for publication

All patients provided written consent for the publication of research performed with their medical data.

Competing interests

No potential conflicts of interests are to declare.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Beat Bojaxhiu, Phone: +41 31 632 2431, Email: beat.bojaxhiu@psi.ch.

Arnoud J. Templeton, Email: arnoud.templeton@claraspital.ch

Olgun Elicin, Email: olgun.elicin@insel.ch.

Mohamed Shelan, Email: mohamed.shelan@insel.ch.

Kathrin Zaugg, Email: kathrin.zaugg@triemli.zuerich.ch.

Marc Walser, Email: marc.walser@psi.ch.

Roland Giger, Email: roland.giger@insel.ch.

Daniel M. Aebersold, Email: daniel.aebersold@insel.ch

Alan Dal Pra, Email: alan.dalpra@med.miami.edu.

References

- 1.Curado MP, Boyle P. Epidemiology of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma not related to tobacco or alcohol. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25(3):229–234. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835ff48c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Templeton AJ, et al. Prognostic role of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2014;23(7):1204–1212. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140(6):883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Callaghan DS, et al. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(12):2024–2036. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f387e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aggarwal BB, Vijayalekshmi RV, Sung B. Targeting inflammatory pathways for prevention and therapy of cancer: short-term friend, long-term foe. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(2):425–430. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumitru CA, Lang S, Brandau S. Modulation of neutrophil granulocytes in the tumor microenvironment: mechanisms and consequences for tumor progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23(3):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tazzyman S, Niaz H, Murdoch C. Neutrophil-mediated tumour angiogenesis: subversion of immune responses to promote tumour growth. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23(3):149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ocana A, et al. Neutrophils in cancer: prognostic role and therapeutic strategies. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):137. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0707-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bekes EM, et al. Tumor-recruited neutrophils and neutrophil TIMP-free MMP-9 regulate coordinately the levels of tumor angiogenesis and efficiency of malignant cell intravasation. Am J Pathol. 2011;179(3):1455–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gregory AD, Houghton AM. Tumor-associated neutrophils: new targets for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2011;71(7):2411–2416. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demers M, Wagner DD. Neutrophil extracellular traps: a new link to cancer-associated thrombosis and potential implications for tumor progression. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(2):e22946. doi: 10.4161/onci.22946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cools-Lartigue J, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(8):3446–3458. doi: 10.1172/JCI67484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donskov F. Immunomonitoring and prognostic relevance of neutrophils in clinical trials. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23(3):200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tazzyman S, Lewis CE, Murdoch C. Neutrophils: key mediators of tumour angiogenesis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2009;90(3):222–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2009.00641.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takenaka Yukinori, Oya Ryohei, Kitamiura Takahiro, Ashida Naoki, Shimizu Kotaro, Takemura Kazuya, Yamamoto Yoshifumi, Uno Atsuhiko. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in head and neck cancer: A meta-analysis. Head & Neck. 2017;40(3):647–655. doi: 10.1002/hed.24986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Templeton AJ, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(6):dju124. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chowdhary M, et al. Post-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts for overall survival in brain metastases treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. J Neuro-Oncol. 2018;139(3):689–697. doi: 10.1007/s11060-018-2914-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Proctor MJ, et al. A comparison of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with cancer. A Glasgow inflammation outcome study. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(17):2633–2641. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guthrie GJ, et al. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: experience in patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88(1):218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.An X, et al. Elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts poor prognosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2011;32(2):317–324. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang HY, et al. Refining the role of preoperative C-reactive protein by neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(11):2690–2699. doi: 10.1002/lary.24105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He JR, et al. Pretreatment levels of peripheral neutrophils and lymphocytes as independent prognostic factors in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2012;34(12):1769–1776. doi: 10.1002/hed.22008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khandavilli SD, et al. Serum C-reactive protein as a prognostic indicator in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(10):912–914. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Millrud CR, et al. The activation pattern of blood leukocytes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is correlated to survival. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perisanidis C, et al. High neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an independent marker of poor disease-specific survival in patients with oral cancer. Med Oncol. 2013;30(1):334. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grimm M, Lazariotou M. Clinical relevance of a new pre-treatment laboratory prognostic index in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2012;29(3):1435–1447. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khoja L, et al. The full blood count as a biomarker of outcome and toxicity in ipilimumab-treated cutaneous metastatic melanoma. Cancer Med. 2016;5(10):2792–2799. doi: 10.1002/cam4.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaverdian N, et al. Pretreatment immune parameters predict for overall survival and toxicity in early-stage non-small-cell lung Cancer patients treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy. Clin Lung Cancer. 2016;17(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolff HA, et al. High-grade acute organ toxicity as positive prognostic factor in adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. Radiology. 2011;258(3):864–871. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tehrany N, et al. High-grade acute organ toxicity and p16(INK4A) expression as positive prognostic factors in primary radio(chemo)therapy for patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2015;191(7):566–572. doi: 10.1007/s00066-014-0801-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geretschlager A, et al. Outcome and patterns of failure after postoperative intensity modulated radiotherapy for locally advanced or high-risk oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:175. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geretschlager A, et al. Definitive intensity modulated radiotherapy in locally advanced hypopharygeal and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma: mature treatment results and patterns of locoregional failure. Radiat Oncol. 2015;10(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13014-014-0323-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gregoire V, et al. CT-based delineation of lymph node levels and related CTVs in the node-negative neck: DAHANCA, EORTC, GORTEC, NCIC, RTOG consensus guidelines. Radiother Oncol. 2003;69(3):227–236. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eisbruch A, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for head and neck cancer: emphasis on the selection and delineation of the targets. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2002;12(3):238–249. doi: 10.1053/srao.2002.32435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisbruch A, et al. Recurrences near base of skull after IMRT for head-and-neck cancer: implications for target delineation in high neck and for parotid gland sparing. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59(1):28–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonner JA, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):567–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mantovani A, et al. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koehne CH, Dubois RN. COX-2 inhibition and colorectal cancer. Semin Oncol. 2004;31(2 7):12–21. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flossmann E, et al. Effect of aspirin on long-term risk of colorectal cancer: consistent evidence from randomised and observational studies. Lancet. 2007;369(9573):1603–1613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60747-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS. Aspirin and the risk of colorectal cancer in relation to the expression of COX-2. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(21):2131–2142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Templeton AJ, et al. Change in neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in response to targeted therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma as a prognosticator and biomarker of efficacy. Eur Urol. 2016;70(2):358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haddad CR, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in head and neck cancer. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2015;59(4):514–519. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.12305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rassouli A, et al. Systemic inflammatory markers as independent prognosticators of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2015;37(1):103–110. doi: 10.1002/hed.23567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong BY, et al. Prognostic value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2016;38(1):E1903–E1908. doi: 10.1002/hed.24346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kruk M, et al. Association of non-specific inflammatory activation with early mortality in patients with ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome treated with primary angioplasty. Circ J. 2008;72(2):205–211. doi: 10.1253/circj.72.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kondo H, Kusaka Y, Morimoto K. Effects of lifestyle on hematologic parameters; I. analysis of hematologic data in association with smoking habit and age. Sangyo Igaku. 1993;35(2):98–104. doi: 10.1539/joh1959.35.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kawada T. Smoking-induced leukocytosis can persist after cessation of smoking. Arch Med Res. 2004;35(3):246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friedman GD, Dales LG, Ury HK. Mortality in middle-aged smokers and nonsmokers. N Engl J Med. 1979;300(5):213–217. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197902013000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rachidi Saleh, Wallace Kristin, Wrangle John M., Day Terry A., Alberg Anthony J., Li Zihai. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and overall survival in all sites of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head & Neck. 2015;38(S1):E1068–E1074. doi: 10.1002/hed.24159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang SH, et al. Prognostic value of pretreatment circulating neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes in oropharyngeal cancer stratified by human papillomavirus status. Cancer. 2015;121(4):545–555. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.