Abstract

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is a pulmonary disease caused by Aspergillus induced hypersensitivity. It usually occurs in immunocompetent but susceptible patients with bronchial asthma and cystic fibrosis. If ABPA goes undiagnosed and untreated, it may progress to bronchiectasis and/or pulmonary fibrosis with significant morbidity and mortality. ABPA is a well-recognized entity in adults; however, there is lack of literature in children. The aim of the present review is to summarize pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, clinical features, and treatment of ABPA with emphasis on the pediatric population. A literature search was undertaken through PubMed till April 30, 2018, with keywords “ABPA or allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis” with limitation to “title.” The relevant published articles related to ABPA in pediatric population were included for the review. The ABPA is very well studied in adults. Recently, it is increasingly being recognized in children. There is lack of separate diagnostic criteria of ABPA for children. Although there are no trials regarding treatment of ABPA in children, steroids and itraconazole are the mainstay of therapy based on studies in adults and observational studies in children. Omalizumab is upcoming therapy, especially in refractory ABPA cases. There is a need to develop the pediatric-specific cutoffs for diagnostic criteria in ABPA. Well-designed trials are required to determine appropriate treatment regimen in children.

KEY WORDS: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, children, itraconazole, omalizumab, steroids

INTRODUCTION

A number of Aspergillus species, particularly Aspergillus fumigatus, cause diseases in humans.[1] Depending on quantity and virulence of inhaled Aspergillus, and host's genetic susceptibility and immunity, Aspergillus can cause saprophytic (e.g., aspergilloma), invasive (especially in immunocompromised patients), or allergic (Aspergillus-mediated asthma, hypersensitivity pneumonia and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis [ABPA]) pulmonary diseases.[2] ABPA is a pulmonary disease caused by Aspergillus-induced hypersensitivity. It usually occurs in immunocompetent but susceptible patients with bronchial asthma and cystic fibrosis (CF).[3,4,5] If ABPA goes undiagnosed and untreated, it may progress to bronchiectasis and/or pulmonary fibrosis with significant morbidity and mortality. ABPA was first described by Hinson et al. in 1952 in asthmatic subjects.[6] Since then, there have been many advances in the understanding of pathophysiology and various treatment options for ABPA. ABPA is well-recognized entity in adults. It is increasingly being recognized in children in recent years. ABPA is one of reasons for poorly controlled asthma with significant morbidity in children. The use of oral steroids, the mainstay treatment of ABPA, may cause adverse effects in growing children. The aim of the present review is to summarize pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, clinical features, and treatment of ABPA with emphasis on the pediatric population.

METHODS

A literature search was undertaken through PubMed till August 31, 2016, with key words “ABPA or allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis” with limitation to “title,” The search was repeated on April 30, 2018, for relevant new articles. The relevant published articles, especially related to ABPA in pediatric population, were studied for writing this review.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Although A. fumigatus is mostly responsible for ABPA,[7] other species of Aspergillus (Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus flavus, etc.) and other fungi (Stemphylium lanuginosum, Helminthosporium species, Candida species, etc.) have been occasionally reported in association with ABPA.[8] The disease caused by fungi other than Aspergillus is known as allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis (ABPM) and Candida albicans is most common cause for ABPM.[9] Out of many fungi, only few (Aspergillus, Candida etc.) causes human diseases including ABPA and ABPM because these are thermotolerant fungi which can grow both in environment and at body temperature whereas mesophilic fungi (that are unable to grow at body temperature) and thermophilic fungi (that are unable to grow in environment) do not cause ABPM.[10]

Agarwal et al.,[11] in a systematic review and meta-analysis, reported the prevalence of Aspergillus sensitization (AS) and ABPA in asthmatic adults of 28% (95% confidence interval [CI] 24–34) and 12.9% (95% CI 7.9–18.9), respectively. With time, there is increasing trend of ABPA prevalence in adults which may be due to increased awareness about ABPA among physicians and ready availability of laboratory investigations.[11]

ABPA in asthmatic children is not as common as in adults and it may be due to lack of well-conducted epidemiological studies in children. Slavin et al.[12] probably reported the first pediatric case of ABPA in 1970. Since then, there are case reports and small case series in asthmatic children.[13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] Imbeau et al.[21] described the three youngest (<2 years of age) asthmatic children with ABPA. The one of the first prevalence study of ABPA in children was from India where ABPA was reported in 15% of children with perennial asthma and in 6.5% of total asthmatic children screened.[21] Recently, a study from North India in children with poorly controlled asthma reported prevalence of AS and ABPA as 29% and 26%, respectively.[23] Shah et al.[24] reported familial occurrence of ABPA in 4.9% of 164 patients. However, ABPA in asthmatic children seems to be underdiagnosed as latent period up to 10 years before diagnosis had been reported.[14]

ABPA in CF patients is not uncommon, even in pediatric age group. A systematic review including 64 studies reported the prevalence of ABPA in CF of 8.9% (95% CI: 7.4%–0.7%), and it was more in adults as compared to children (10.1% vs. 8.9%; P < 0.0001).[25] The studies including mainly CF children had reported the prevalence of ABPA from 4.7% to 10.0%.[26,27,28,29,30] The probable youngest CF child with ABPA had symptoms from the age of 11 months, though she was diagnosed with ABPA at age of 3.5 years.[31] A study from India, reported ABPA in 18.2% (95% CI: 6.9%–35.4%) children with CF.[32]

Although sensitization to Aspergillus is common in asthmatic and CF patients (20%–25% of asthmatic patients and 31%–59% of CF patients), only a small percentage of these patients develop ABPA.[3,4,5] A few authors tried to identify the risk factors for ABPA in CF children. Jubin et al.[33] reported an association between long-term azithromycin therapy and Aspergillus colonization (odds ratio = 6.4, 95% CI: 2.1–19.5). Ritz et al.[34] showed that bronchial colonization with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia was a risk factor for ABPA and higher cumulative doses of inhaled corticosteroids, and longer duration of Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization were risk factors for A. fumigatus sensitization in CF children. In study from India, age more than 12 years, low-cystic fibrosis score, and presence of atopy and eosinophilia were risk factors for ABPA in CF children.[32]

ABPA had been described very rarely in nonasthmatic, non-CF children. Amin et al.[35] reported a case of ABPA in nonasthmatic 18 years male. Boz et al.[36] reported ABPA in a 11-year-old girl following active pulmonary tuberculosis. Recently, two cases of ABPA in children were reported with non-CF bronchiectasis.[37]

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Although underlying pathophysiology of ABPA is not yet clearly understood, Aspergillus spores adhere to preactivated epithelium in genetically susceptible patients with asthma or CF and grow into hyphae. After bronchial penetration, Aspergillus antigens activate immune response resulting in bronchial/bronchiolar inflammation and destruction.[3] The CD4+ Th2 cells along with their cytokines (especially interleukin [IL]-4) play an important role in pathogenesis of ABPA.[38]

Genetic factors

The balance between human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-antigen D-related molecules associated with susceptibility to ABPA (DR2, DR5, and possibly, DR4 or DR7) and resistance to ABPA (HLA-DQ2) determine the course of ABPA in patients with asthma and CF.[39] A number of genetic factors have also been identified in association with ABPA including CF transmembrane conductor regulator gene mutations,[40] SP-A2 (genes encoding surfactant protein-A),[41] IL-4 alpha-chain receptor polymorphisms,[42] IL-10 polymorphisms,[43] toll-like receptor polymorphisms,[44] integrin β3 polymorphisms,[45] chitinase polymorphisms,[46] A disintegrin and metalloprotease 33 gene,[47] protocadherin 1 polymorphisms,[48] and mannan-binding lectin[49] polymorphism.

The host factor may also play a role in colonization and penetration of Aspergillus into respiratory epithelium, for example, impaired mucus clearance in CF may contribute to greater bronchial adherence of Aspergillus.[28]

Why does ABPA develop only in a proportion of Aspergillus sensitive asthmatic and CF patients? Knutsen et al.[38] hypothesized that ABPA develops in genetically susceptible patients with asthma and CF who have increased frequency and/or activity of A. fumigatus specific CD4+ Th2 cells.

Pathology of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

In ABPA, there is cylindrical bronchiectasis of central airways especially those to upper lobes.[3,5,28] Pathological bronchial specimens in ABPA, although not necessary for diagnosis, shows bronchial tree dilatation and lumen filled with mucus plugs containing eosinophils, macrophages, Charcot–Leyden crystals, and occasionally hyphal fragments.[3,5]

DIAGNOSIS OF ALLERGIC BRONCHOPULMONARY ASPERGILLOSIS

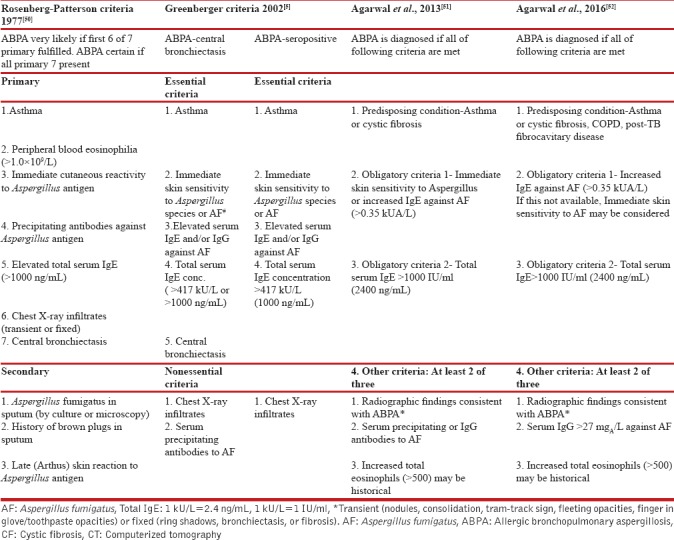

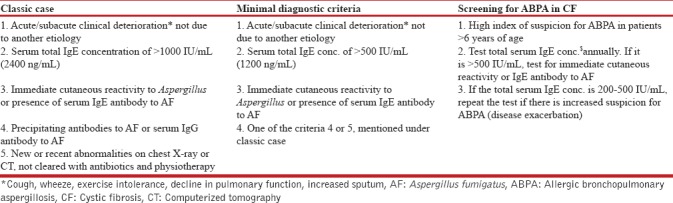

The diagnostic criteria for ABPA are described in adults, and the same is used in pediatrics as there are no separate criteria for children. In 1977, Rosenberg–Patterson criteria[50] were proposed for diagnosis of ABPA [Table 1]. The criteria for diagnosis of ABPA in asthmatic patients were later modified by Greenberger.[5] Recently, Agarwal et al. proposed new diagnostic criteria in 2013[51] and later modified in 2016 [Table 1].[52] The simple cutaneous sensitivity test (skin prick test) may be a useful screening test, as ABPA is very unlikely in patients with a negative skin test.[40] The cutoffs of total IgE for ABPA in children are not well defined. A pediatric study from India suggested a cutoff of total IgE of 1200 IU/ml for ABPA in children.[23] For ABPA in CF, Nelson et al.[53] proposed that at least five of the following seven criteria had to be present for diagnosing ABPA in CF patients, namely, wheezing, increased total serum IgE, positive specific IgE to A. fumigatus, serum Aspergillus IgG precipitins, positive skin test, radiological pulmonary infiltrates, and bronchiectasis. Recently, CF Foundation Consensus has laid down the diagnostic criteria of ABPA in CF as well as criteria for screening for ABPA in CF patients [Table 2].[28] Diagnosis of ABPA in CF patients may be difficult due to overlapping clinical features (frequent exacerbations with bronchial obstruction, pulmonary infiltrate, and bronchiectasis).[28] The central bronchiectasis, one of the diagnostic criteria for ABPA in asthma, cannot be used for CF patients as it is not uncommon in CF patients even without ABPA.

Table 1.

Changing diagnostic criteria for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in asthma with time

Table 2.

Diagnostic criteria for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis[28]

Patients with ABPA in asthma, in addition to diagnostic criteria, may have sputum containing A. fumigatus, mucus impactions, and peripheral blood eosinophilia.[5] Culture of A. fumigatus from the sputum is a nonspecific finding as many patients with asthma or CF without ABPA have Aspergillus on sputum cultures.[54]

Recombinant Aspergillus fumigatus allergens

About 22 recombinant A. fumigatus allergens (named from rAsp f 1 to rAsp f 22) had been identified.[3,5] A. fumigatus allergens, namely. rAsp f 1, rAsp f 2, rAsp f 3, rAsp f 4 and rAsp f 6 had mixed results in differentiating ABPA from sensitization both in asthmatic and CF patients.[55,56,57] A recent systematic review suggested that a combination of rAsp antigens may be more helpful than a single rAsp for diagnosis of ABPA, though grade of evidence was low to very low.[58] Therefore, to define the exact role of recombinant A. fumigatus allergens in diagnosing ABPA, especially in children, there is need for further research.

The thymus and activation-regulated chemokine[59] and basophil activation test (CD63 and CD203c)[60] were also found useful in differentiating ABPA from AS in CF patients.

RADIOLOGICAL FINDINGS

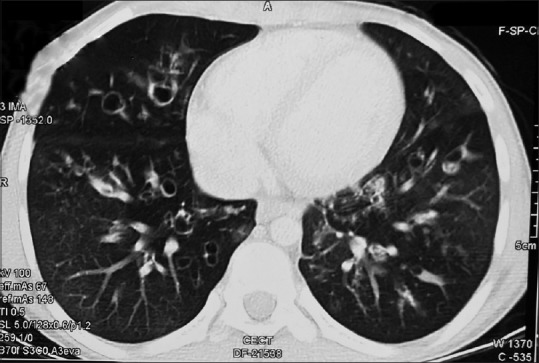

High-resolution computerized tomography (HRCT) is the investigation of choice to delineate lung lesions in ABPA. In ABPA, central bronchiectasis and fleeting shadows are the most common radiological findings both in children and adults.[19] Figure 1 shows a chest X-ray of child with advanced ABPA revealing bronchiectasis and fibrosis. Bronchiectasis in CT chest in a child with ABPA is shown in Figure 2. Other CT findings in ABPA include: tram-line shadow, dilated and totally occluded bronchi (bronchocele), glove-finger shadow, air-fluid levels within dilated bronchi, bronchial wall thickening, parallel-line shadows, ring shadow, toothpaste shadow, parenchymal abnormalities (homogeneous consolidation, collapse, and parenchymal scarring) with predilection for upper lobes, cavities, and mass-like lesion.[19,61,62] High-attenuation mucus (HAM), seen as opaque shadow in dilated bronchi that is denser than associated paraspinal muscle shadow, is considered almost pathognomonic for ABPA.[51] The hilar lymphadenopathy had also been reported in ABPA in children.[63] Recently, Dournes et al.[64] reported that inverted mucoid impaction signal (presence of mucus with high T1 and low T2 signal intensity) on noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging was 94% (95% CI: 73%–99%) sensitive and 100% specific (95% CI: 96%–100%) for diagnosing ABPA in CF patients.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray of a child with advanced allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis showing bronchiectasis and fibrosis; note that bronchiectasis is more in central part

Figure 2.

A computed tomography chest in child with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis showing bronchiectasis

LUNG FUNCTION TESTS

Kraemer et al.[65] reported severe progressive deterioration in all lung function parameters, volume of trapped gas, and effective airway resistance in CF children with ABPA.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND STAGES

ABPA patients, both children and adults, may present with poorly controlled asthma, wheezing, constitutional symptoms (fever, weight loss), mucopurulent expectoration, increased cough, dyspnea, chest pain, and hemoptysis.[3,5,14] ABPA in CF patients may be associated with exacerbation of symptoms, weight loss, and a marked increase in productive cough.[28] Even life-threatening presentation of ABPA in CF children has been reported.[66] Physical examination is usually not remarkable except for crackles and rhonchi. ABPA is frequently misdiagnosed initially for other diseases mainly tuberculosis, particularly in developing countries.[67] ABPA should be suspected in asthmatics who had difficult to control asthma despite good compliance to therapy. The diagnosis of ABPA should be suspected in children with CF who show wheezing, transient pulmonary infiltrates and had exacerbations responding poorly to antibiotics.

Patterson et al.[68] proposed five stages of ABPA progression: (1) acute; (2) remission; (3) exacerbation; (4) corticosteroid-dependent asthma; and (5) fibrosis (end stage). The acute stage has most of the features of disease and responds well to steroids. In remission stage, usually, there is no clinical or laboratory evidence of ABPA. The exacerbation stage has recurrence of acute stage of ABPA. The corticosteroid-dependent asthma stage is characterized by recurrent exacerbations of ABPA and severe asthma. Patients with fibrotic stage have severe dyspnea and cyanosis, and there is extensive bronchiectasis, cavitary lesions, and fibrosis in lungs, and they have poor prognosis. Kumar[69] divided patients with ABPA into three forms: mild (ABPA serologic positive; ABPA-S), moderate (ABPA with central bronchiectasis; ABPA-CB), and severe (ABPA with central bronchiectasis and other radiologic features; ABPA-CB-ORF). One more radiological classification based on HAM had been proposed by Agarwal et al.[70] that include ABPA-S, ABPA-CB, and ABPA-CB-HAM. Recently, Agarwal et al.[52] suggested the seven stages of ABPA: stage 0 (asymptomatic-ABPA criteria are fulfilled in a patient of controlled asthma), Stage 1 (Acute-ABPA criteria positive along with uncontrolled symptoms), Stage 2 (response-clinically better with total IgE decreased by >25% from baseline), Stage 3 (exacerbation-clinically worsened with total IgE increased >50% from baseline), Stage 4 (remission-clinically improved with total IgE at baseline or increase is <50%), Stage 5 (treatment dependent-≥2 exacerbations in 6 months or worsening on tapering steroids), and Stage 6 (advanced-extensive bronchiectasis and cor pulmonale). The ABPA in advanced stage may be complicated by cor pulmonale and pulmonary thromboembolism even in children.[71] There is no separate staging of ABPA for children. It has been suggested that early recognition and treatment may prevent the progression of ABPA from mild form to moderate and severe forms.[5]

TREATMENT OF ALLERGIC BRONCHOPULMONARY ASPERGILLOSIS

The goals in the treatment of ABPA should be: (1) suppression of inflammatory response using corticosteroids; (2) to eradicate colonization and/or proliferation of A. fumigatus in lungs using antifungal agents; (3) to limit ABPA exacerbations by high index suspicion and prompt investigation; and (4) to prevent end-stage fibrotic disease.[3,28,38] Thus, corticosteroids and antifungal agents are the two mainstay modalities of treatment for ABPA.

CORTICOSTEROIDS

Systemic (oral) corticosteroids, usually prednisolone, are the most effective treatment for the acute phase of ABPA both in asthma and CF.[3,5,28] In asthmatic patients with ABPA, the recommended dosage of prednisolone is 0.5 mg/kg/day for the first 2 weeks, followed by a progressive tapering over the next 12–16 weeks.[3,38] Another regimen for steroids include high dose that is prednisolone 0.75 mg/kg for 6 weeks, 0.5 mg/kg for another 6 weeks, and then tapering for total duration of 6–12 months. A RCT in adults with asthma had shown that medium and high dose of steroids were equally effective for ABPA, though high-dose steroids had more side effects.[72] Long-term steroid therapy is not recommended for ABPA except for stage IV (steroid-dependent asthma) where the minimal dose of steroids is required to stabilize the patient.

Higher dosage of corticosteroids had been recommended for ABPA in CF patients. For ABPA in CF patients, CF Foundation Consensus Conference report recommended an initial dose of prednisolone as 0.5–2.0 mg/kg/day (maximum 60 mg) for 1–2 weeks, then 0.5–2.0 mg/kg/day every other day for 1–2 weeks, and then taper in next 2–3 months.[28] Children on oral steroids should be monitored for side effects including cushingoid facies, hypertension, weight gain, height, and osteoporosis if used for long time or repeatedly.

Pulse methylprednisolone

Cohen-Cymberknoh et al.[73] used high-dose pulse methylprednisolone (10–15 mg/kg/d for 3 days per month) and itraconazole in nine patients with CF and ABPA (4 males, 5 females, age 7–36 years) with improvement in clinical and laboratory parameters and minor side effects. Thomson et al.[74] used pulse methylprednisolone to manage severe ABPA in four CF children out of which three children responded well although with troublesome side effects.

ANTIFUNGAL DRUG-ITRACONAZOLE

For allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in asthma

A Cochrane meta-analysis, evaluating the role of azoles in ABPA in asthma, included three randomized controlled trials (RCT) and concluded that itraconazole improves clinical outcome in ABPA.[75] Adrenal suppression with inhaled corticosteroids and itraconazole is a potential concern. An RCT in adults compared monotherapy with steroids versus monotherapy with itraconazole in acute stage of ABPA and found that steroids were better.[76] There is hardly any study evaluating the efficacy of itraconazole for ABPA in asthmatic children, and it is difficult to recommend antifungal triazoles as first-line treatment with steroids in children with ABPA; though it used frequently based on data from adults. The itraconazole dose recommended for children include 5 mg/kg/day, maximum 400 mg/day (in two divided doses if total daily dose exceeds 200 mg).[28] The total duration of therapy should be 3–6 months.[28]

For allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis patients

Skov et al.[77] reported 21 CF patients with ABPA (8–30 years of age, 17 were below 18 years) where the use of itraconazole (200–600 mg/day) with or without steroids decreased sputum culture for Aspergillus, precipitating antibodies and IgE levels, and increased FEV1 without significant side effects. Lebeau et al.[78] used itraconazole (200 mg/day) in three CF children of ABPA (aged 8,10, and 11 years); two children responded but third child had liver abnormality requiring stoppage of treatment. There has been no RCT till date on the use of itraconazole in CF children with ABPA. The CF Foundation Consensus report recommended the use of itraconazole for ABPA in CF if there is a slow or poor response to steroids, for relapse of ABPA, in corticosteroid-dependent ABPA, and in cases of corticosteroid-induced toxicity.[28]

OMALIZUMAB (RECOMBINANT ANTI-IgE ANTIBODY)

For allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in asthmatic patients

Aydin et al.[79] reported the benefits of omalizumab in 14 adult asthmatics with ABPA in the form of decreased exacerbations, lesser oral steroids use, and better pulmonary function. There is hardly any study of omalizumab use in asthmatic children with ABPA. A small RCT involving 13 adults patients with asthma and ABPA reported that the use of omalizumab resulted in significantly lower number of exacerbations as compared to placebo.[80]

Recently, an asthmatic women with refractory ABPA was successfully treated with a combination of omalizumab and mepolizumab (an anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody).[81] There were two more adult cases who were treated successfully with mepolizumab.[82,83]

For allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis patients

van der Ent et al.[84] first described the use of omalizumab in a 12-year-old CF girl with ABPA and there was a dramatic and rapid improvement of respiratory symptoms and lung function after a single dose. Nové-Josserand et al.[85] reported the steroid-sparing effect of omalizumab in 32 CF patients with ABPA (21 adults and 11 children) in a multicentric retrospective study. Li et al.[86] also reported the beneficial effect of omalizumab in patients with ABPA in a review of 102 cases from 40 published records that included both asthmatic and CF patients and both adults and children. A recent Cochrane review found only one RCT and that was also terminated prematurely and suggested further large trials of omalizumab in CF patients with ABPA.[87]

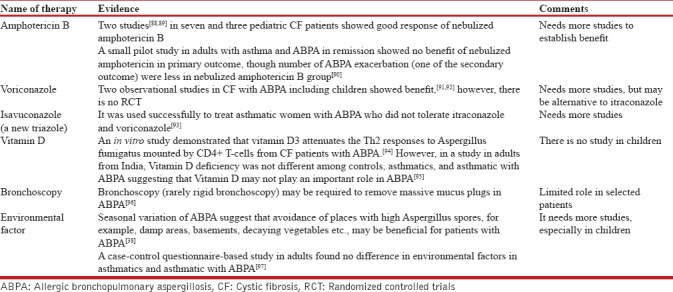

The role of other adjuvant therapies in ABPA is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Miscellaneous therapy for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

MONITORING FOR TREATMENT RESPONSE

The treatment of ABPA should be monitored by clinical features (including lung function tests), serum total IgE levels and chest imaging (X-ray or HRCT).[3,4] The total IgE level is a useful marker of disease activity in ABPA, and it can be used to monitor patients for “exacerbations.” A study in adults with ABPA suggested that total IgE decreased at least 25% from baseline along clinical improvement after therapy and it increased by >50% with exacerbation.[98] The Aspergillus-specific IgE is not useful to monitor response to treatment.[98] Although there are no such studies in children.

CONCLUSIONS

ABPA in children with asthma is increasingly being recognized. The ABPA is not uncommon in children with CF. Early and aggressive treatment of ABPA is crucial for preventing the serious sequelae of central bronchiectasis, pulmonary fibrosis, severe impairment in lung function and cor pulmonale. Corticosteroids and azoles are mainstay of treatment for ABPA in asthma and CF, though there is lack of RCTs regarding usefulness of azoles for ABPA in children. Omalizumab may be a potential therapy for refractory ABPA in asthma and CF patients. There is not much evidence available for other adjuvant therapies for ABPA. Monitoring of patients with ABPA is recommended using clinical, laboratory (mainly total IgE), and radiological parameters.

There is need for more vigilance for diagnosing ABPA in asthmatic children. The role of itraconazole and voriconazole in asthmatic and CF children with ABPA is yet to be established. Future research, particularly RCTs, is needed for other adjuvant therapies before they can be used for ABPA.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geiser DM, Klich MA, Frisvad JC, Peterson SW, Varga J, Samson RA, et al. The current status of species recognition and identification in Aspergillus. Stud Mycol. 2007;59:1–10. doi: 10.3114/sim.2007.59.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soubani AO, Chandrasekar PH. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Chest. 2002;121:1988–99. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.6.1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tillie-Leblond I, Tonnel AB. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Allergy. 2005;60:1004–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agarwal R. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Chest. 2009;135:805–26. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberger PA. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:685–92. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.130179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinson KF, Moon AJ, Plummer NS. Broncho-pulmonary aspergillosis; a review and a report of eight new cases. Thorax. 1952;7:317–33. doi: 10.1136/thx.7.4.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latgé JP. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:310–50. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.2.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lake FR, Tribe AE, McAleer R, Froudist J, Thompson PJ. Mixed allergic bronchopulmonary fungal disease due to Pseudallescheria boydii and Aspergillus. Thorax. 1990;45:489–91. doi: 10.1136/thx.45.6.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chowdhary A, Agarwal K, Kathuria S, Gaur SN, Randhawa HS, Meis JF, et al. Allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis due to fungi other than Aspergillus: A global overview. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2014;40:30–48. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.754401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolnough K, Fairs A, Pashley CH, Wardlaw AJ. Allergic fungal airway disease: Pathophysiologic and diagnostic considerations. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2015;21:39–47. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D, Jindal SK. Aspergillus hypersensitivity and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in patients with bronchial asthma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:936–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slavin RG, Laird TS, Cherry JD. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in a child. J Pediatr. 1970;76:416–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(70)80482-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chhabra SK, Sahay S, Ramaraju K. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis complicating childhood asthma. Indian J Pediatr. 2009;76:331–2. doi: 10.1007/s12098-009-0020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwerk N, Rochwalsky U, Brinkmann F, Hansen G. Don't forget other causes of wheeze. ABPA in a boy with asthma. A case report and review of the literature. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:307–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohshima M, Futamura M, Kamachi Y, Ito K, Sakamoto T. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in a 2-year-old asthmatic boy with immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44:297–9. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki K, Iwata S, Iwata H. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in a 9-year-old boy. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161:408–9. doi: 10.1007/s00431-002-0942-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah A, Bhagat R, Panchal N. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with clubbing and cavitation. Indian Pediatr. 1993;30:248–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banerjee B, Joshi AP, Sarma PU, Roy S. Evaluation of clinico-immunological parameters in pediatric ABPA patients. Indian J Pediatr. 1992;59:109–14. doi: 10.1007/BF02760911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah A, Pant CS, Bhagat R, Panchal N. CT in childhood allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:227–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02012505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bedi RS. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Indian Pediatr. 1991;28:1520–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chetty A, Bhargava S, Jain RK. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in Indian children with bronchial asthma. Ann Allergy. 1985;54:46–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imbeau SA, Cohen M, Reed CE. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in infants. Am J Dis Child. 1977;131:1127–30. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1977.02120230073013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh M, Das S, Chauhan A, Paul N, Sodhi KS, Mathew J, et al. The diagnostic criteria for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in children with poorly controlled asthma need to be re-evaluated. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:e206–9. doi: 10.1111/apa.12930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah A, Kala J, Sahay S, Panjabi C. Frequency of familial occurrence in 164 patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101:363–9. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maturu VN, Agarwal R. Prevalence of Aspergillus sensitization and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45:1765–78. doi: 10.1111/cea.12595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feanny S, Forsyth S, Corey M, Levison H, Zimmerman B. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis: A secretory immune response to a colonizing organism. Ann Allergy. 1988;60:64–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marchant JL, Warner JO, Bush A. Rise in total IgE as an indicator of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 1994;49:1002–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.10.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevens DA, Moss RB, Kurup VP, Knutsen AP, Greenberger P, Judson MA, et al. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis – State of the art: Cystic fibrosis foundation consensus conference. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(Suppl 3):S225–64. doi: 10.1086/376525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skov M, McKay K, Koch C, Cooper PJ. Prevalence of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis in an area with a high frequency of atopy. Respir Med. 2005;99:887–93. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simmonds EJ, Littlewood JM, Evans EG. Cystic fibrosis and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:507–11. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.5.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mussaffi H, Greif J, Kornreich L, Ashkenazi S, Levy Y, Schonfeld T, et al. Severe allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in an infant with cystic fibrosis and her asthmatic father. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;29:155–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(200002)29:2<155::aid-ppul11>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma VK, Raj D, Xess I, Lodha R, Kabra SK. Prevalence and risk factors for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in Indian children with cystic fibrosis. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:295–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jubin V, Ranque S, Stremler Le Bel N, Sarles J, Dubus JC. Risk factors for Aspergillus colonization and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45:764–71. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ritz N, Ammann RA, Casaulta Aebischer C, Schoeni-Affolter F, Schoeni MH. Risk factors for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and sensitisation to Aspergillus fumigatus in patients with cystic fibrosis. Eur J Pediatr. 2005;164:577–82. doi: 10.1007/s00431-005-1701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amin MU, Mahmood R. Multiple bronchoceles in a non-asthmatic patient with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58:514–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boz AB, Celmeli F, Arslan AG, Cilli A, Ogus C, Ozdemir T, et al. A case of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis following active pulmonary tuberculosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44:86–9. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De H, Azad SM, Giri PP, Pal P, Ghosh A, Maitra A, et al. Two cases of non-cystic fibrosis (CF) bronchiectasis with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;20:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knutsen AP, Slavin RG. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in asthma and cystic fibrosis. Clin Dev Immunol 2011. 2011:843763. doi: 10.1155/2011/843763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knutsen AP, Kariuki B, Santiago LA, Slvin RG, Wofford JD, Bellone C, et al. HLADR, IL-4RA, and IL-10: Genetic risk factors in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Pediatr Asthma Allergy Immunol. 2008;21:185–90. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marchand E, Verellen-Dumoulin C, Mairesse M, Delaunois L, Brancaleone P, Rahier JF, et al. Frequency of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene mutations and 5T allele in patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Chest. 2001;119:762–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.3.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saxena S, Madan T, Shah A, Muralidhar K, Sarma PU. Association of polymorphisms in the collagen region of SP-A2 with increased levels of total IgE antibodies and eosinophilia in patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1001–7. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Risma KA, Wang N, Andrews RP, Cunningham CM, Ericksen MB, Bernstein JA, et al. V75R576 IL-4 receptor alpha is associated with allergic asthma and enhanced IL-4 receptor function. J Immunol. 2002;169:1604–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brouard J, Knauer N, Boelle PY, Corvol H, Henrion-Caude A, Flamant C, et al. Influence of interleukin-10 on Aspergillus fumigatus infection in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1988–91. doi: 10.1086/429964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang JE, Warris A, Ellingsen EA, Jørgensen PF, Flo TH, Espevik T, et al. Involvement of CD14 and toll-like receptors in activation of human monocytes by Aspergillus fumigatus hyphae. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2402–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2402-2406.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiss LA, Lester LA, Gern JE, Wolf RL, Parry R, Lemanske RF, et al. Variation in ITGB3 is associated with asthma and sensitization to mold allergen in four populations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:67–73. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200411-1555OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chatterjee R, Batra J, Das S, Sharma SK, Ghosh B. Genetic association of acidic mammalian chitinase with atopic asthma and serum total IgE levels. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.030. 208.e1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reijmerink NE, Kerkhof M, Koppelman GH, Gerritsen J, de Jongste JC, Smit HA, et al. Smoke exposure interacts with ADAM33 polymorphisms in the development of lung function and hyperresponsiveness. Allergy. 2009;64:898–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.01939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koppelman GH, Meyers DA, Howard TD, Zheng SL, Hawkins GA, Ampleford EJ, et al. Identification of PCDH1 as a novel susceptibility gene for bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:929–35. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1621OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaur S, Gupta VK, Shah A, Thiel S, Sarma PU, Madan T, et al. Elevated levels of mannan-binding lectin [corrected] (MBL) and eosinophilia in patients of bronchial asthma with allergic rhinitis and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis associate with a novel intronic polymorphism in MBL. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;143:414–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenberg M, Patterson R, Mintzer R, Cooper BJ, Roberts M, Harris KE, et al. Clinical and immunologic criteria for the diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86:405–14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-86-4-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Agarwal R, Chakrabarti A, Shah A, Gupta D, Meis JF, Guleria R, et al. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: Review of literature and proposal of new diagnostic and classification criteria. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43:850–73. doi: 10.1111/cea.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agarwal R, Sehgal IS, Dhooria S, Aggarwal AN. Developments in the diagnosis and treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2016;10:1317–34. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2016.1249853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nelson LA, Callerame ML, Schwartz RH. Aspergillosis and atopy in cystic fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;120:863–73. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.120.4.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Vrankrijker AM, van der Ent CK, van Berkhout FT, Stellato RK, Willems RJ, Bonten MJ, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus colonization in cystic fibrosis: Implications for lung function? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1381–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hemmann S, Menz G, Ismail C, Blaser K, Crameri R. Skin test reactivity to 2 recombinant Aspergillus fumigatus allergens in A fumigatus-sensitized asthmatic subjects allows diagnostic separation of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis from fungal sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:601–7. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fricker-Hidalgo H, Coltey B, Llerena C, Renversez JC, Grillot R, Pin I, et al. Recombinant allergens combined with biological markers in the diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis patients. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:1330–6. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00200-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Oliveira E, Giavina-Bianchi P, Fonseca LA, França AT, Kalil J. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis’ diagnosis remains a challenge. Respir Med. 2007;101:2352–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muthu V, Sehgal IS, Dhooria S, Aggarwal AN, Agarwal R. Utility of recombinant Aspergillus fumigatus antigens in the diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: A systematic review and diagnostic test accuracy meta-analysis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2018 doi: 10.1111/cea.13216. doi: 10.1111/cea.13216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Latzin P, Hartl D, Regamey N, Frey U, Schoeni MH, Casaulta C, et al. Comparison of serum markers for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:36–42. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Katelari A, Tzanoudaki M, Noni M, Kanariou M, Theodoridou M, Kanavakis E, et al. The role of basophil activation test in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and Aspergillus fumigatus sensitization in cystic fibrosis patients. J Cyst Fibros. 2016;15:587–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Panchal N, Bhagat R, Pant C, Shah A. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: The spectrum of computed tomography appearances. Respir Med. 1997;91:213–9. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(97)90041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huppmann MV, Monson M. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: A unique presentation in a pediatric patient. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:879–83. doi: 10.1007/s00247-008-0824-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shah A, Kala J, Sahay S. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with hilar adenopathy in a 42-month-old boy. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:747–8. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dournes G, Berger P, Refait J, Macey J, Bui S, Delhaes L, et al. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis: MR imaging of airway mucus contrasts as a tool for diagnosis. Radiology. 2017;285:261–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017162350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kraemer R, Deloséa N, Ballinari P, Gallati S, Crameri R. Effect of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis on lung function in children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1211–20. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-423OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Skowronski E, Fitzgerald DA. Life-threatening allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in a well child with cystic fibrosis. Med J Aust. 2005;182:482–3. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ragosta KG, Clayton JA, Cambareri CB, Domachowske JB. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis masquerading as pulmonary tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:582–4. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000130078.79239.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patterson R, Greenberger PA, Radin RC, Roberts M. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: Staging as an aid to management. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:286–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-3-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kumar R. Mild, moderate, and severe forms of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: A clinical and serologic evaluation. Chest. 2003;124:890–2. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Agarwal R, Khan A, Gupta D, Aggarwal AN, Saxena AK, Chakrabarti A, et al. An alternate method of classifying allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis based on high-attenuation mucus. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Azad C, Jat KR, Aggarwal P. Bronchial asthma with ABPA presenting as PTE. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2013;17:188–9. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.117078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Dhooria S, Singh Sehgal I, Garg M, Saikia B, et al. A randomised trial of glucocorticoids in acute-stage allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis complicating asthma. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:490–8. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01475-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cohen-Cymberknoh M, Blau H, Shoseyov D, Mei-Zahav M, Efrati O, Armoni S, et al. Intravenous monthly pulse methylprednisolone treatment for ABPA in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2009;8:253–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thomson JM, Wesley A, Byrnes CA, Nixon GM. Pulse intravenous methylprednisolone for resistant allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006;41:164–70. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wark PA, Gibson PG, Wilson AJ. Azoles for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis associated with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;3:CD001108. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001108.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Agarwal R, Dhooria S, Singh Sehgal I, Aggarwal AN, Garg M, Saikia B, et al. A randomized trial of itraconazole vs. prednisolone in acute-stage allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis complicating asthma. Chest. 2018;153:656–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Skov M, Høiby N, Koch C. Itraconazole treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in patients with cystic fibrosis. Allergy. 2002;57:723–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.23583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lebeau B, Pelloux H, Pinel C, Michallet M, Goût JP, Pison C, et al. Itraconazole in the treatment of aspergillosis: A study of 16 cases. Mycoses. 1994;37:171–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1994.tb00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Aydın Ö, Sözener ZÇ, Soyyiğit Ş, Kendirlinan R, Gençtürk Z, Mısırlıgil Z, et al. Omalizumab in the treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: One center's experience with 14 cases. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2015;36:493–500. doi: 10.2500/aap.2015.36.3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Voskamp AL, Gillman A, Symons K, Sandrini A, Rolland JM, O’Hehir RE, et al. Clinical efficacy and immunologic effects of omalizumab in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3:192–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Altman MC, Lenington J, Bronson S, Ayars AG. Combination omalizumab and mepolizumab therapy for refractory allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1137–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Terashima T, Shinozaki T, Iwami E, Nakajima T, Matsuzaki T. A case of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis successfully treated with mepolizumab. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18:53. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0617-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oda N, Miyahara N, Senoo S, Itano J, Taniguchi A, Morichika D, et al. Severe asthma concomitant with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis successfully treated with mepolizumab. Allergol Int. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2018.03.004. pii: S1323-8930(18)30038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.van der Ent CK, Hoekstra H, Rijkers GT. Successful treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with recombinant anti-igE antibody. Thorax. 2007;62:276–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.035519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nové-Josserand R, Grard S, Auzou L, Reix P, Murris-Espin M, Brémont F, et al. Case series of omalizumab for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis patients. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52:190–7. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li JX, Fan LC, Li MH, Cao WJ, Xu JF. Beneficial effects of omalizumab therapy in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: A synthesis review of published literature. Respir Med. 2017;122:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jat KR, Walia DK, Khairwa A. Anti-IgE therapy for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in people with cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:CD010288. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010288.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Proesmans M, Vermeulen F, Vreys M, De Boeck K. Use of nebulized amphotericin B in the treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis. Int J Pediatr 2010. 2010:376287. doi: 10.1155/2010/376287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Laoudi Y, Paolini JB, Grimfed A, Just J. Nebulised corticosteroid and amphotericin B: An alternative treatment for ABPA? Eur Respir J. 2008;31:908–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00146707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ram B, Aggarwal AN, Dhooria S, Sehgal IS, Garg M, Behera D, et al. A pilot randomized trial of nebulized amphotericin in patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Asthma. 2016;53:517–24. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2015.1127935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Glackin L, Leen G, Elnazir B, Greally P. Voriconazole in the treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis. Ir Med J. 2009;102:29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hilliard T, Edwards S, Buchdahl R, Francis J, Rosenthal M, Balfour-Lynn I, et al. Voriconazole therapy in children with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2005;4:215–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jacobs SE, Saez-Lacy D, Wynkoop W, Walsh TJ. Successful treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with isavuconazole: Case report and review of the literature. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx040. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kreindler JL, Steele C, Nguyen N, Chan YR, Pilewski JM, Alcorn JF, et al. Vitamin D3 attenuates Th2 responses to Aspergillus fumigatus mounted by CD4+T cells from cystic fibrosis patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3242–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI42388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Agarwal R, Sehgal IS, Dhooria S, Aggarwal AN, Sachdeva N, Bhadada SK, et al. Vitamin D levels in asthmatic patients with and without allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2018;61:344–9. doi: 10.1111/myc.12744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Gupta N, Gupta D. A rare cause of acute respiratory failure – Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2011;54:e223–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Agarwal R, Devi D, Gupta D, Chakrabarti A. A questionnaire-based study on the role of environmental factors in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Lung India. 2014;31:232–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.135762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Sehgal IS, Dhooria S, Behera D, Chakrabarti A, et al. Utility of IgE (total and Aspergillus fumigatus specific) in monitoring for response and exacerbations in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2016;59:1–6. doi: 10.1111/myc.12423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]