Abstract

AIM:

The aim of this study is to compare the surgical outcomes of pterygium excision with conjunctival autograft using sutures, fibrin glue (tisseel), and autologous blood for the management of primary pterygium.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

A retrospective study done in 681 eyes with primary nasal pterygium. Excision of the pterygium was performed followed by closure of the bare sclera with conjunctival autograft using interrupted 10-0 monofilament nylon sutures in 173 eyes (Group 1), fibrin glue (tisseel-baxter healthcare corporation, westlake village, ca-91362 USA) in 351 eyes (Group 2), and autologous blood in 157 eyes (Group 3). Patients were followed up for a period of 5–52 months. During follow-up, graft-related complications such as recurrence, graft loss, graft retraction, granuloma if any were noted and compared among the three groups.

RESULTS:

A total of 681 eyes who had primary nasal pterygium were included in this study. Pterygium excision with conjunctival autograft was performed using 10-0 monofilament nylon interrupted sutures in 173 eyes (25.4%), tisseel fibrin glue in 351 eyes (51.54%), and autologous blood in 157 (23.05%) eyes. The mean duration of follow-up was 5–52 months. The overall recurrence rate was 2.9% (20 eyes). In Group 1, recurrence was seen in 5 eyes (2.89%), in Group 2, it was seen in 7 eyes (1.99%) and in Group 3, 8 eyes (5.10%). However, the recurrence rate was not significant (P = 0.160). The rate of graft retraction in the 3 study groups were 12 eyes (6.94%), 10 eyes (2.85%), and 56 eyes (35.67%) with a significant P < 0.001. Granuloma was seen in 2 eyes (1.16%), in Group 1, and in 1 eye (0.64%) in Group 3. Graft loss was seen in 3 eyes (1.73%), 4 eyes (1.14%), 6 eyes (3.82%) in Group 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

CONCLUSION:

The outcomes of the three most commonly performed surgical technique of conjunctival autograft fixation has shown us that all three techniques are equally comparable and can be offered to our patients with equally good results.

Keywords: Autologous blood, conjunctival autografting, fibrin glue, outcomes, pterygium, sutures

Introduction

Pterygium is defined as a degenerative ocular surface disorder with wing-shaped fibrovascular growth of the conjunctival tissue onto the cornea.[1] A number of surgical techniques have been described as methods for management of pterygium, including bare sclera resection, mitomycin c application at different point of time, doses, and concentrations,[2,3] amniotic membrane transplantation and conjunctival autografting.[3] In 1985, Kenyon et al. proposed that a conjunctival autograft of the bare sclera could be used in the treatment of recurrent and advanced pterygium.[4] Since then, conjunctival autografting has become the standard of care in the management of both primary and recurrent pterygium as the procedure offers excellent results regarding recurrence, complication rates, and cosmesis. The most common method of autograft fixation is using sutures. However, it has its own drawbacks such as increased operating time, postoperative discomfort, inflammation, buttonholes, necrosis, giant papillary conjunctivitis, scarring, and granuloma formation.[5] Fibrin glue is widely used due to many advantages such as easy fixation of the graft, shorter surgical time, reduction in complications, and postoperative discomfort but at the same time has some disadvantages also such as high cost, the risk of transmission of infections, and inactivation by iodine preparations,[6,7,8] and it is not easily available to all treating surgeons. Another approach is autologous blood for graft fixation, a technique also known as suture-and glue-free autologous graft fixation. Autologous blood is natural, has no extra cost or associated risks, and can overcome the postoperative irritations to a great extent.[9]

In this study, we have retrospectively analyzed and compared the surgical outcomes of primary pterygium excision followed by fixing the graft to bare sclera using sutures (10-0, Monofilament Nylon sutures, Ethilon, Johnson and Johnson) or fibrin glue (tisseel) or autologous blood for graft fixation. Patients were analyzed for complications and final outcome of each surgical technique. The available literature comparing sutures, fibrin glue, and glue-free conjunctival autograft was scanty, further in view of problems encountered with the sutured graft and the trend toward the increasing use of sutureless grafting for pterygium surgery, a comparative study can throw light on the three techniques simultaneously comparing their merits and demerits; hence, the current study was undertaken.

Patients and Methods

The study was a retrospective comparative study, at a tertiary care hospital in South India. Medical records of patients who underwent pterygium excision with conjunctival autografting between January 2010 and December 2015 were reviewed and included patients with, primary pterygium encroaching the cornea, pterygium excision for cosmetic reasons, patients with primary pterygium having symptoms of irritation watering and redness. The study excluded patients with recurrent pterygium, fleshy pterygium accompanied by symblepharon or limitation of duction, double-headed pterygium, glaucoma filtering bleb, and glaucoma suspects. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study had initially included 737 eyes of 737 patients, keeping a minimum follow-up period of 5–52 months. Out of which 56 patients could not complete the minimum follow up period of 5 months, hence, were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Institutions Ethical Committee.

The study sample consisted of 681 eyes divided into three groups, Group 1: conjunctival autograft with sutures – 173 eyes, Group 2: conjunctival autograft with fibrin glue (tisseel) – 351 eyes, Group 3: conjunctival autograft with autologous blood – 157 eyes. The outcomes following each of the above techniques were analyzed.

Surgical technique

A single surgeon performed all the surgeries. Topical proparacaine Hcl was applied 3 times at an interval of 10 min before the start of the surgery. A 0.5–1cc of 2% xylocaine was injected subconjunctivally into the pterygium tissue. The approximate size of the pterygium was about 6–8 mm horizontally from the apex to the base, and 4–7 mm vertically at the base with an extension of 0.5–3 mm from the limbus onto the cornea. The pterygium was avulsed from the apex using a toothed forceps and a iris spatula. The pterygium body and the underlying fibrovascular tissues were delineated from the conjunctiva and excised using conjunctival forceps. Gentle cauterization was done to achieve hemostasis. The superior or the superotemporal bulbar conjunctiva was selected as a donor site. 1–2cc of 2% xylocaine was injected subconjunctivally to separate conjunctiva from the Tenon's capsule. A small nick incision was made using Vannas scissors and a thin graft of approximately 0.5 mm larger than the bare sclera defect in all directions expect at the limbal end was fashioned. As thin a graft as possible was excised and placed on the bare scleral bed and was fixed using either 10-0 monofilament nylon or fibrin glue or autologous blood. For, autologous blood graft fixation, a thin graft of size slightly bigger than the bare scleral defect was taken, a thin film of capillary blood was allowed to ooze over the bare sclera and the graft was placed over the area for a period of 5–7 min giving gentle pressure for the graft to adhere to the sclera. Overnight patching was done in all the cases and the patient was seen on the postoperative day 1, 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 6 months, and every year thereafter. Postoperatively, patients were started on steroid-antibiotic combinations and tear substitutes for a period of 4 weeks. The groups were analyzed and compared with regard to the postoperative surgical outcomes and complications.

Statistical analysis

Recurrence of the pterygium was considered as primary outcome variable. Edema, subconjunctival hemorrhage, retraction, loss of graft, and granuloma were considered as other outcome variables. Descriptive analysis of all the variables was done using mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables, frequency and proportion for categorical variables. Quantitative parameters were compared across the groups, using ANOVA. Categorical variables across the groups were compared using cross tabulation and Chi-square test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. IBM SPSS Statistics for windows, Version 21.0.(IBM corp, Armonk, NY) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

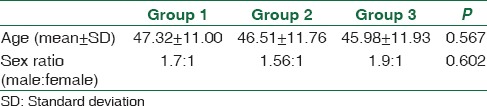

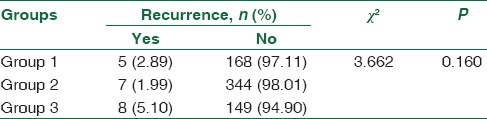

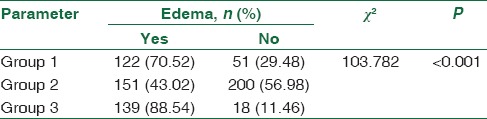

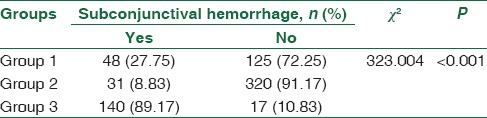

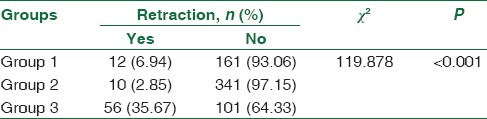

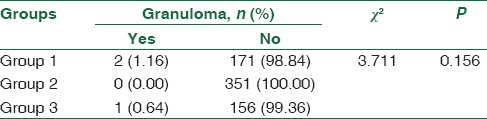

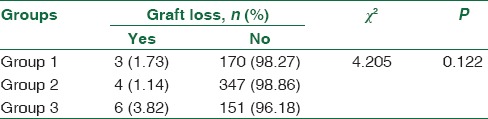

A total of 681 eyes underwent pterygium excision with conjunctival autograft in The Eye Foundation Hospital and Post Graduate training institute. The mean age was 47.32, 46.51, and 45.98 years in Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The male: female ratio was comparable across the study groups. There were no statistically significant differences in age and gender across the study groups [Table 1]. The proportion of subjects, who had recurrence was highest in Group 3, (5.10%), followed By Group 1 (2.89%). In Group 2, the recurrence was lowest as only 1.99% of the subjects had recurrence. However, the differences across the procedures in recurrence rates were statistically not significant [Table 2]. The proportion of subjects, who had edema was 70.52%, 43.025% and 88.54% in Group 1, 2, and 3 respectively. The differences in proportion of edema across the study groups were statistically not significant [Table 3]. The proportion of subjects, who had subconjunctival hemorrhage was 27.75%, 8.835%, and 89.17%, respectively, in Group 1, 2, and 3, respectively [Table 4]. The Proportion of subjects, with graft retraction was 6.94%, 2.85% and 35.67% in Group 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Of the total number of eyes which developed retraction only 2 eyes in Group 1, 1 eye in Group 2, and 4 eyes in Group 3 had recurrence, however, the differences in the proportion of retraction was statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Table 5]. The proportion of subjects, who developed granuloma was 1.16%, 0%, and 0.64% in study Group 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The differences across the study groups in granuloma occurrence were statistically not significant [Table 6]. About 1.73% of the subjects in Group 1 had graft loss. This proportion was 1.14% in Group 2 and 3.82% in Group 3. The differences in graft loss across the study groups were statistically not significant (0.122) [Table 7].

Table 1.

Comparison of age and sex ratio (patient demographics)

Table 2.

Comparison of recurrence across the three study groups

Table 3.

Comparison of graft edema across the 3 study groups

Table 4.

Comparison of subconjunctival haemorrhage across the three study groups

Table 5.

Comparison of retraction across the 3 study groups

Table 6.

Comparison of granuloma across the 3 study groups

Table 7.

Comparison of graft loss across the 3 study groups

Discussion

The main challenge to a successful pterygium excision is the high chance of recurrence and graft-related complications. Many surgical techniques have been brought into practise to reduce the recurrences, none of them have proved fully accepted worldwide. In our study, the overall rate of recurrence was noted as 2.9% (20 eyes out of 681 eyes). As such we do not have any broad consensus over the procedures for the management of pterygium. Conjunctival autografting is considered the gold standard in the management of primary pterygium. Recurrence of pterygium after its surgical excision is the most common and frustrating cause of concern for both the surgeon and the patient. Most of the times, the recurrence after pterygium surgery occur within the first 6 months after surgery.[10] One such method to prevent recurrence is autologous conjunctival grafting. Conjunctival autograft transplantation reestablishes the barrier function of limbus and hence significantly lowers the recurrence rate. It can be either attached with sutures or with biological adhesive-like fibrin glue or with autologous blood.

Suturing of the autograft requires surgical experience and technical skills. Suzuki et al. reported that the use of silk or nylon sutures causes conjunctival inflammation and Langerhans cell migration into the cornea.[11] Increased operation time required for suturing is another problem[12] and may cause patient discomfort, delen formation, symblepharon, or graft tear.[13,14] A study conducted by Coral-Ghanem et al. have shown that among 58 eyes operated for primary pterygium, 15 eyes (25.9%) had recurrence, and the mean time for recurrence was 4.5 months,[15] in our study, recurrence was seen in 5 eyes (2.89%).

Another alternative is to use a biological tissue glue, like fibrin glue, for securing the graft. Advantages of using it are easy fixation of the graft, shorter surgical time; however, the disadvantages are the high cost of the fibrin glue. Koranyi et al. reported the cost of 0.5 ml of fibrin glue is equal to the cost of five 7-0 vicryl sutures.[6] The study by Coral-Ghanem et al. showed a recurrence in 12 eyes (11.3%) out of 106 eyes, on whom fibrin glue was used to fix the graft,[15] our study noted a recurrence in 7 eyes (1.99%).

Another approach is autologous blood graft fixation. A study by Boucher et al. showed a recurrence in 4 patients, out of 20 on whom autologous blood was used for graft fixation, and in our study, there was a recurrence seen in eight patients (5.10%).[16]

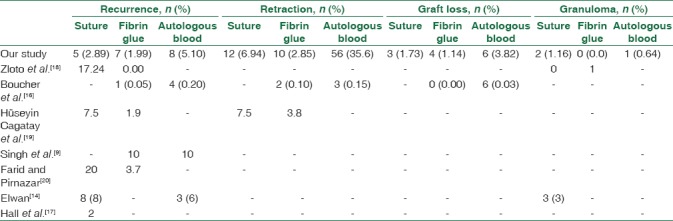

In our study, in a follow-up period of 52 months, complications such as recurrence was noted in five eyes (2.89%) in Group 1, 7 eyes (1.99%) in Group 2 and 8 eyes (5.10%) in Group 3. The highest recurrence rate in Group 3 could be because of weak adhesion bond (blood clot) between the bare sclera and the graft, the coagulam formed will degrade in 48–72 h whereas the “Aprotinin” present in the tissue glue stabilizes the clot and prevents clot degeneration for up to 10 days. In Group 1, the slightly higher incidence could be due to graft loss due to sutures cutting through early in the postoperative period. In a study by zloto et al, the recurrence rate was 17.24 in the suture group whereas in our study the recurrence rate was 2.89%.[18] Conjunctival edema was seen in 122 (70.52%) in Group 1, 151 (43.02%) in Group 2, and 139 (88.54%) in Group 3. Granuloma formation was seen in 2 (1.16%) in Group 1, no patients in Group 2, and 1 (0.64%) in Group 3. A study by elwan showed conjunctival edema in 8 eyes (16%) and 6 eyes (6%), recurrence in 3 eyes (6%), and 8 eyes (8%) and granuloma formation in 0 (0%) and 3 eyes (3%) autologous blood and sutured limbal conjunctival autograft, respectively.[17] A study by Hall et al., there was no recurrence at the end of 3 months in the glue group and 2 recurrences in the suture group. In our study, graft retraction was seen in 12 eyes (6.94%) in Group 1, 10 eyes (2.85%) in Group 2, 56 eyes (35.67%) in Group 3 and was statistically significant (P < 0.001). Retraction of the graft means sliding of the graft from its original position. In our study, retraction of the graft indicates the sliding of the graft from its opposite end with the limbal end being intact. Graft loss was seen in 3 eyes (1.73%) in Group 1, 4 eyes (1.14%) in Group 2, and 6 eyes (3.82%) in Group 3. The graft loss observed in our study seems to be one of the most important causes for the recurrences in patients belonging to Group 3; unfortunately, all the 6 eyes which had graft loss ended up having recurrence. Subconjunctival hemorrhage was seen in 48 eyes (22.75%) in Group 1, 31 eyes (8.83%) in Group 2, and 140 eyes (89.17%) in Group 3, this increase in the incidence of subconjunctival hemorrhage in Group 3 is due to the use of autologous blood for the fixation of the graft.

Subconjunctival hemorrhage was the most common finding in autologous blood group, reasons being obvious we use blood for graft fixation. Graft retraction and graft loss have been found to be more common with autologous blood for graft fixation, could be due to weak adhesion property of autologous blood in comparison with the commercially available fibrin glue preparation. All those who had graft loss had recurrence and it was seen between 5 and 12 months after surgery. Table 8 shows us the various surgical outcomes published in previous studies.

Table 8.

Surgical outcomes in other studies

Conclusion

Our study has thrown light on the surgical outcomes of the three most commonly performed graft fixation techniques of conjunctival autografting, recurrences were seen less in those who underwent autografting with both fibrin glue (tisseel) and suturing when compared to autologous blood. The other most common complication seen with the surgery being graft retraction and graft loss and the incidence was more in the autologous blood Group 3 than with the other two groups. Although there were complications such as recurrence, retraction, graft loss noted in our study, the overall recurrence rate of all the three groups together was just 2.9%, indicating that all three surgical techniques were equally good and can be offered to our patients with very good outcomes. The results of our study may add to the growing volume of data demonstrating the surgical outcomes following pterygium surgery.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hill JC, Maske R. Pathogenesis of pterygium. Eye (Lond) 1989;3(Pt 2):218–26. doi: 10.1038/eye.1989.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayasaka S, Noda S, Yamamoto Y, Setogawa T. Postoperative instillation of low-dose mitomycin C in the treatment of primary pterygium. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:715–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90706-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahar PS, Nwokora GE. Role of mitomycin C in pterygium surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:433–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.7.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenyon KR, Wagoner MD, Hettinger ME. Conjunctival autograft transplantation for advanced and recurrent pterygium. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:1461–70. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)33831-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starck T, Kenyon KR, Serrano F. Conjunctival autograft for primary and recurrent pterygia: Surgical technique and problem management. Cornea. 1991;10:196–202. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koranyi G, Seregard S, Kopp ED. Cut and paste: A no suture, small incision approach to pterygium surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:911–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.032854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foroutan A, Beigzadeh F, Ghaempanah MJ, Eshghi P, Amirizadeh N, Sianati H, et al. Efficacy of autologous fibrin glue for primary pterygium surgery with conjunctival autograft. Iran J Ophthalmol. 2011;23:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilmore OJ, Reid C. Prevention of intraperitoneal adhesions: A comparison of noxythiolin and a new povidone-iodine/PVP solution. Br J Surg. 1979;66:197–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800660318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh PK, Singh S, Vyas C, Singh M. Conjunctival autografting without fibrin glue or sutures for pterygium surgery. Cornea. 2013;32:104–7. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31824bd1fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen PP, Ariyasu RG, Kaza V, LaBree LD, McDonnell PJ. A randomized trial comparing mitomycin C and conjunctival autograft after excision of primary pterygium. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:151–60. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki T, Sano Y, Kinoshita S. Conjunctival inflammation induces langerhans cell migration into the cornea. Curr Eye Res. 2000;21:550–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ti SE, Chee SP, Dear KB, Tan DT. Analysis of variation in success rates in conjunctival autografting for primary and recurrent pterygium. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:385–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.4.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HH, Mun HJ, Park YJ, Lee KW, Shin JP. Conjunctivolimbal autograft using a fibrin adhesive in pterygium surgery. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2008;22:147–54. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2008.22.3.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elwan SA. Comparison between sutureless and glue free versus sutured limbal conjunctival autograft in primary pterygium surgery. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2014;28:292–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coral-Ghanem R, Oliveira RF, Furlanetto E, Ghanem MA, Ghanem VC. Conjunctival autologous transplantation using fibrin glue in primary pterygium. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2010;73:350–3. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27492010000400010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boucher S, Conlon R, Teja S, Teichman JC, Yeung S, Ziai S, et al. Fibrin glue versus autologous blood for conjunctival autograft fixation in pterygium surgery. Can J Ophthalmol. 2015;50:269–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall RC, Logan AJ, Wells AP. Comparison of fibrin glue with sutures for pterygium excision surgery with conjunctival autografts. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;37:584–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.02105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zloto O, Greenbaum E, Fabian ID, Ben Simon GJ. Evicel versus tisseel versus sutures for attaching conjunctival autograft in pterygium surgery: A prospective comparative clinical study. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:61–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hüseyin Cagatay H, Gökçe G, Mete A, Koban Y, Ekinci M. Non-recurrence complications of fibrin glue use in pterygium surgery: Prevention and management. Open Ophthalmol J. 2015;9:159–63. doi: 10.2174/1874364101509010159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farid M, Pirnazar JR. Pterygium recurrence after excision with conjunctival autograft: A comparison of fibrin tissue adhesive to absorbable sutures. Cornea. 2009;28:43–5. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318183a362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]