BEST1 is a chloride channel that is activated by calcium. Vaisey and Long demonstrate that ionic currents through BEST1 inactivate by an allosteric mechanism in which the binding of a C-terminal peptide to a surface-exposed receptor controls a physically distant inactivation gate within the pore.

Abstract

Bestrophin proteins are calcium (Ca2+)-activated chloride channels. Mutations in bestrophin 1 (BEST1) cause macular degenerative disorders. Whole-cell recordings show that ionic currents through BEST1 run down over time, but it is unclear whether this behavior is intrinsic to the channel or the result of cellular factors. Here, using planar lipid bilayer recordings of purified BEST1, we show that current rundown is an inherent property of the channel that can now be characterized as inactivation. Inactivation depends on the cytosolic concentration of Ca2+, such that higher concentrations stimulate inactivation. We identify a C-terminal inactivation peptide that is necessary for inactivation and dynamically interacts with a receptor site on the channel. Alterations of the peptide or its receptor dramatically reduce inactivation. Unlike inactivation peptides of voltage-gated channels that bind within the ion pore, the receptor for the inactivation peptide is on the cytosolic surface of the channel and separated from the pore. Biochemical, structural, and electrophysiological analyses indicate that binding of the peptide to its receptor promotes inactivation, whereas dissociation prevents it. Using additional mutational studies we find that the “neck” constriction of the pore, which we have previously shown to act as the Ca2+-dependent activation gate, also functions as the inactivation gate. Our results indicate that unlike a ball-and-chain inactivation mechanism involving physical occlusion of the pore, inactivation in BEST1 occurs through an allosteric mechanism wherein binding of a peptide to a surface-exposed receptor controls a structurally distant gate.

Introduction

The human bestrophin 1 (BEST1) gene was discovered by genetic linkage analysis of patients with an eye disease known as Best vitelliform macular dystrophy (Marquardt et al., 1998; Petrukhin et al., 1998). It is now recognized that bestrophin proteins (BEST1–4 in humans) form pentameric chloride (Cl−) channels that are directly activated by intracellular calcium (Ca2+; Sun et al., 2002; Qu et al., 2003, 2004; Tsunenari et al., 2003; Hartzell et al., 2008; Kane Dickson et al., 2014; Vaisey et al., 2016). Mutations in BEST1 are responsible for other retinopathies; these include adult-onset macular dystrophy (Seddon et al., 2001), autosomal dominant vitreochoidopathy (Yardley et al., 2004), and autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy (Burgess et al., 2008). Of the disease-causing mutations that have been analyzed, most disrupt channel activity, which suggests a causal relationship between channel function and disease. In further support of a direct role in the physiology of the eye, a recent study using retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells that were derived from induced pluripotent stem cells showed that BEST1 is indispensable for mediating the Ca2+-dependent Cl− currents in these cells (Li et al., 2017). The broad tissue distribution of bestrophin proteins suggests additional functions outside of the eye (Bakall et al., 2008; Hartzell et al., 2008). Of particular note, these functions may include regulation of cell volume (Fischmeister and Hartzell, 2005; Milenkovic et al., 2015).

Human BEST1 contains 585 amino acids. The highly conserved N-terminal region comprising amino acids 1–390 is sufficient to produce Ca2+-dependent Cl− channel function when expressed in mammalian cells (Xiao et al., 2008). Electrical recordings of purified chicken BEST1 (amino acids 1–405, which shares 74% sequence identity with human BEST1) in planar lipid bilayers showed that the channel is directly activated by the binding of Ca2+ ions (K1/2 ∼17 nM) to “Ca2+ clasps” on the cytosolic surface of the channel (Kane Dickson et al., 2014; Vaisey et al., 2016).

In addition to activating the channel, Ca2+ has been shown to have an inhibitory effect on BEST1 currents. In whole-cell recordings of human BEST1 the current initially increases after patch break-in and then runs down on a timescale of minutes (Xiao et al., 2008). The rate of rundown is faster at higher (μM) concentrations of Ca2+. C-terminal truncations of BEST1 reduce or abolish current rundown, suggesting that the C-terminal region is involved in the mechanism of current rundown (Xiao et al., 2008). Other studies on human BEST3, which gave no currents when expressed as the full-length gene in HEK 293 cells, identified an “autoinhibitory motif” (356IPSFLGS362) within an analogous C-terminal region, and alanine substitutions within this motif activated Cl− currents (Qu et al., 2006, 2007).

The x-ray structure of chicken BEST1 revealed that the channel is formed from a pentameric assembly of BEST1 subunits and contains a single ion conduction pore along the channel’s fivefold axis of symmetry (Kane Dickson et al., 2014). The pore is ∼95 Å long and contains two constrictions: the "aperture" and the "neck." The aperture is located at the intracellular entrance of the pore and is lined by the side chains of V205. Following the aperture, the pore widens though a 50-Å-long inner cavity before narrowing again within the neck, the walls of which are lined by three highly conserved hydrophobic amino acids from each subunit (I76, F80, and F84). After the neck, the pore widens again through the remainder of the membrane region and extends to the extracellular side. The neck spans ∼15 Å of the inner leaflet of the membrane and is a hot spot for disease-causing mutations (Milenkovic et al., 2011). Using a combination of mutagenesis, electrophysiology, and x-ray crystallography, we have shown that the neck functions as a gate that opens and closes in response to the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration to permit ion flow through the pore in a Ca2+-dependent manner (Vaisey et al., 2016). Simultaneous mutation of the residues that line the neck to alanine (a construct denoted “BEST1TripleA”) renders the channel constitutively active and independent of the Ca2+ concentration (Vaisey et al., 2016). Mutation of the neck does not alter the ion selectivity properties of the channel, either with regard to the preference for anions over cations or with regard to the relative permeabilities among permeant anions (Vaisey et al., 2016). The aperture controls distinct properties of the channel. The V205A mutation has no effect on the Ca2+ dependence of the channel, indicating that the aperture does not function as the Ca2+-dependent gate. On the other hand, we showed that the V205A mutation dramatically alters the relative permeabilities among anions and that the aperture functions as a size-selective filter. In the structure, a C-terminal tail from each subunit, which contains the region corresponding to the autoinhibitory motif identified by the Hartzell laboratory, adopts an extended conformation following the final α-helix (S4b) and wraps around the cytosolic domains of two other subunits (Kane Dickson et al., 2014; Figs. 2 B and 3 A). How the C-terminal tail and its interaction with BEST1 affect channel behavior is unclear.

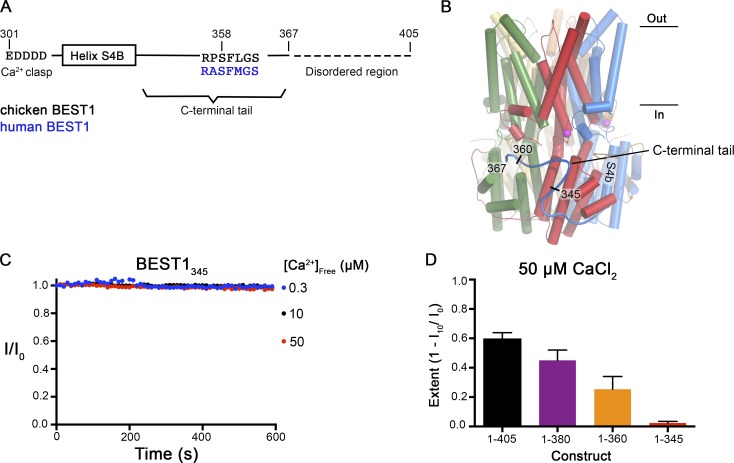

Figure 2.

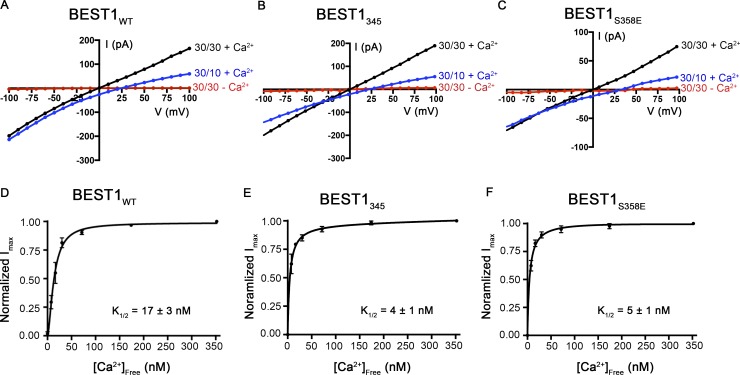

Truncations of the C-terminal tail disrupt Ca2+-dependent inactivation of BEST1. (A) Schematic of the C-terminal region of BEST1, showing residues that contribute to the Ca clasp, helix S4b, and the C-terminal tail. The inhibitory sequence, contained within this tail, is annotated for both chicken and human BEST1. (B) Structure of BEST1WT highlighting the position of a C-terminal tail from one of the five identical subunits. The perspective is from within the membrane, with subunits colored individually, α-helices depicted as cylinders, Ca2+ ions shown as magenta spheres, and the approximate boundaries of the membrane indicated. Helix S4b and truncation points within the C-terminal are labeled. (C) Bilayer electrophysiology shows that BEST1345 does not undergo Ca2+-dependent inactivation. Experimental conditions are identical to those for Fig. 1, A and B. (D) The extent of inactivation in 50 µM Ca2+ is shown for different C-terminal truncations of BEST1. Experiments were performed as in C, and at least three independent experiments were performed for each construct to calculate SD.

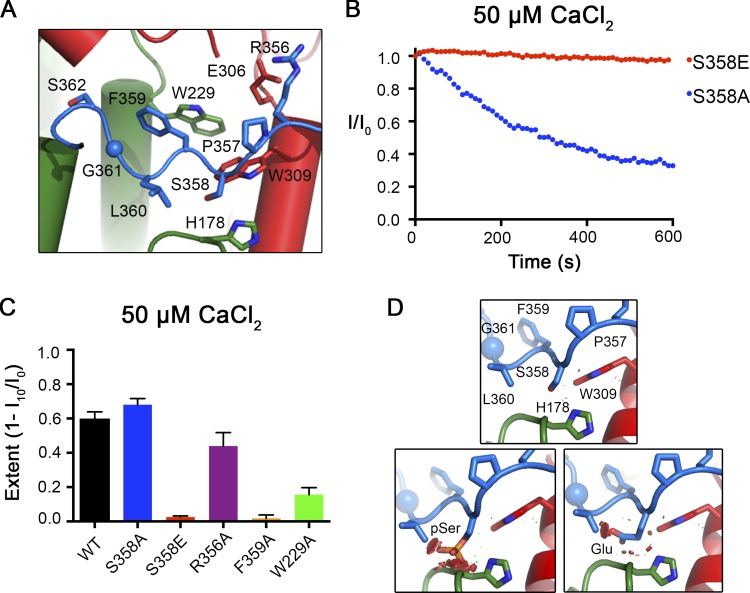

Figure 3.

Mutations within the inactivation peptide or its receptor can prevent inactivation. (A) Close-up view of the 356RPSFLGS362 sequence of BEST1 as illustrated in Fig. 2 B. (B) The Ca2+-dependent inactivation of BEST1S358A and BEST1S358E, using 50 µM Ca2+, was recorded as described in Fig. 1 A. (C) The extent of inactivation is shown for different mutants. Experiments were performed as in B, and at least three independent experiments were performed for each construct to calculate SD. (D) Modeling shows that mutation of S358 to glutamate or its phosphorylation would cause steric clashes. The top panel shows a stick representation of S358 of the inactivation peptide (blue-colored carbon atoms) and surrounding contacts with the receptor (green- and red-colored carbon atoms). The bottom panels show that modeling of a phosphoserine (left) or S358E mutation (right) would cause clashes, which are depicted as red dots.

In this study we sought to investigate the molecular causes of current rundown in BEST1. Using bilayer electrophysiology we determine that rundown is an intrinsic property of the channel that can now be characterized as inactivation. Using mutagenesis, electrophysiology, and biochemical approaches, we identify the principal components of the channel responsible for inactivation: a C-terminal inactivation peptide, a cytosolic receptor, and an allosterically controlled inactivation gate.

Materials and methods

Cloning, expression, and purification of BEST1

All constructs of chicken BEST1 (comprising amino acids 1–405, 1–380, 1–360, 1–345, or mutants thereof) were cloned into the pPICZa plasmid (Invitrogen), encode an affinity tag at their C termini (Glu-Gly-Glu-Glu-Phe) that is recognized by an anti-tubulin antibody (YL1/2; Kilmartin et al., 1982), and were transformed into Pichia pastoris (Invitrogen) by electroporation (BioRad Micropulser). Transformants were selected on YPDS agar plates containing 1,000–2,000 µg/ml Zeocin (Invitrogen). Resistant colonies were grown to OD600 ∼20 in liquid culture using glycerol as a carbon source (BMG, Invitrogen) at 30°C, collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in buffered minimal methanol medium (Invitrogen; containing 0.7% methanol and 200 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6) for 24 h at 27°C. Cells (typically ∼40 g from 2 liters of culture) were harvested by centrifugation, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Cryolysis was performed using a Retsch, Inc., model MM301 mixer mill equipped with two 35-ml vessels each containing ∼6 g of cells (3 × 3.0 min at 30 cycles per second).

Lysed cells were resuspended (using ∼10 ml of buffer for each gram of cells) in solubilization buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 75 mM NaCl, 75 mM KCl, 0.1 mg ml−1 DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich), a 1:600 dilution of Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Set III, EDTA-free (CalBiochem), and 0.5 mm 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulphonyl fluoride hydrochloride (Gold Biotechnology). 0.14 g of n-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DDM; Anatrace) was added per 1 g of cells. The pH was adjusted to pH 7.5 using 1 M NaOH, and the sample was agitated for 45 min at room temperature. After extraction, the sample was centrifuged at 43,000 g at 12°C for 40 min and filtered using a 0.45-µM polyethersulphone membrane. The BEST1 protein was affinity purified using YL1/2 antibody coupled to CNBr-activated sepharose beads according to the manufacturer’s protocol (GE Healthcare). For each 1 g of cell lysate, 1.0–2.0 ml of resin was added, and the mixture was rotated at room temperature for 1 h. The mixture was applied to a column support and washed with approximately five column volumes of buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 75 mM NaCl, 75 mM KCl, and 3 mM DDM. Elution was performed using four column volumes of elution buffer: 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 75 mM NaCl, 75 mM KCl, 3 mM DDM, and 5 mM Glu-Glu-Phe peptide (synthesized by Peptide 2.0). The elution fraction was concentrated to a volume of 0.5 ml using a 100,000 D concentrator (Amicon Ultra; EMD Millipore) before further purification by size exclusion chromatography (SEC; Superose 6 increase 10/300 GL; GE Healthcare).

Reconstitution into liposomes for planar lipid bilayer recordings

The SEC-purified protein (in gel filtration buffer: 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 3 mM n-decyl-β-D-maltoside [Anatrace]) was reconstituted into liposomes. A 3:1 (wt/wt) mixture of POPE (Avanti) and POPG (Avanti) lipids was prepared to 20 mg ml−1 in reconstitution buffer (10 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.6, 450 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EGTA, 0.19 mM CaCl2), and the lipids were solubilized by adding 8% (wt/vol) n-octyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (Anatrace) and incubated with rotation for 30 min at room temperature. Purified protein was mixed with an equal volume of the solubilized lipids to give a final protein concentration of 0.2–1 mg ml−1 and a lipid concentration of 10 mg ml−1. Samples were then dialyzed (8,000 D molecular mass cutoff) for 16–48 hours at 4°C against 2–4 liters of reconstitution buffer to remove detergent. Liposomes were then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Electrophysiological recordings

Frozen liposomes were thawed and sonicated for ∼10 s using an Ultrasonic Cleaner (Laboratory Supplies Company). All data are from recordings made using the Warner planar lipid bilayer workstation (Warner Instruments). Two aqueous chambers (4 ml) were filled with bath solutions. Chlorided silver (Ag/AgCl) wires were used as electrodes, submerged in 3 M KCl, and connected to the bath solutions via agar–KCl salt bridges (2% [wt/vol] agar, 3 M KCl). The bath solutions were separated by a polystyrene partition with an ∼200-µM hole across which a bilayer was painted using POPE:POPG in n-decane (3:1 [wt/wt] ratio at 20 mg ml−1). Liposomes were fused under an osmotic gradient across the bilayer (Miller, 2013) with solutions consisting of 30 mM KCl (cis side) or 10 mM KCl (trans side), 20 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.6, and 0.21 mM EGTA/0.19 mM CaCl2 ([Ca2+]free ∼300 nM) or 1 µM CaCl2. Liposomes were added, 1 µl at a time, to the cis chamber to a preformed bilayer until currents were observed. Solutions were stirred using a stir plate (Warner Instruments) to aid vesicle fusion and made symmetrical by adding 20 mM KCl (from a 3 M KCl stock) to the trans side. Unless noted, all reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All electrical recordings were taken at room temperature (22–24°C).

For inactivation experiments, after obtaining stable currents in symmetrical conditions, CaCl2 was added to both cis and trans chambers, and solutions were stirred while recording. For Ca2+ reactivation experiments, 10 mM EGTA was added to the cis chamber to deactivate channels with their cytosolic side facing this direction. Using a perfusion system (Nanion Technologies), the trans chamber was then perfused with 20 ml (five chamber volumes) of bath solutions containing EGTA–Ca buffers (mixtures of 1 mM EGTA and 1 mM EGTA–Ca made according to Bers et al. [1994]) to yield varying concentrations of [Ca2+]free from ∼0 to ∼350 nM. The [Ca2+]free in these solutions was estimated using the maxchelator software (Schoenmakers et al., 1992) and was verified using standard solutions (Invitrogen; pH adjusted to 7.6 with NaOH) and Fura-2 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Currents were recorded using the Clampex 10.4 program (Axon Instruments) with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments) and were sampled at 200 µs and filtered at 1 kHz. Data were analyzed using Clampfit 10.4 (Axon Instruments), and graphical display and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software. In all cases, currents from bilayers without channels are subtracted. Error bars represent the SEM of at least three separate experiments, each in a separate bilayer. We define the side to which the vesicles are added as the cis side and the opposite trans side as electrical ground, so that transmembrane voltage is reported as Vcis–Vtrans. Ion channels are inserted in both orientations in the bilayer.

Fab purification

Monoclonal antibodies against BEST1WT were raised in mice by the Monoclonal Antibody Core Facility of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and selected for cocrystallization aids as described (Kane Dickson et al., 2014). The antibodies were expressed in mouse hybridoma cells, purified by ion exchange chromatography, and cleaved using papain (Worthington) to generate Fab fragments. The Fab fragments were purified using ion exchange chromatography (Resource S; GE Healthcare), dialysed into buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 75 mM NaCl, 75 mM KCl, and further purified using SEC (Superose 6 increase 10/300 GL; GE Healthcare) using the same buffer.

Fab binding assay

To assess binding of the Fab to BEST1WT and BEST1S358E, 10 nM Fab was incubated (>30 min at 4°C) with various concentrations of BEST1 ranging from 1 to 200 nM in buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 75 mM NaCl, 75 mM KCl, 1 mM DDM) containing either 5 mM EGTA or 10 µM CaCl2. 400 µl of each mixture was loaded onto an SEC column (Superose 6 increase 10/300 GL; GE Healthcare), which was equilibrated in the same buffer, and the fraction of unbound Fab was quantified from the area under the elution peak corresponding to free Fab (at 27.5 ml using tryptophan fluorescence on a Shimadzu RF-20AXS fluorescence detector), which is well separated from the peaks for BEST1 and BEST1-Fab complex (22.8 and 20.7 ml, respectively), in comparison to a Fab control. For high-affinity BEST1–Fab interactions (e.g., Kd < 50 nM), the binding of Fab to BEST1 will deplete the amount of free BEST1 in the assay at low concentrations of BEST1 (e.g., <50 nM), and thus, the actual binding may be tighter than indicated by a fit of the data (as described in Figs. 5 D and 6 D). We indicate this by reporting Kd values as ≤X nM, where X is the value derived from the fit.

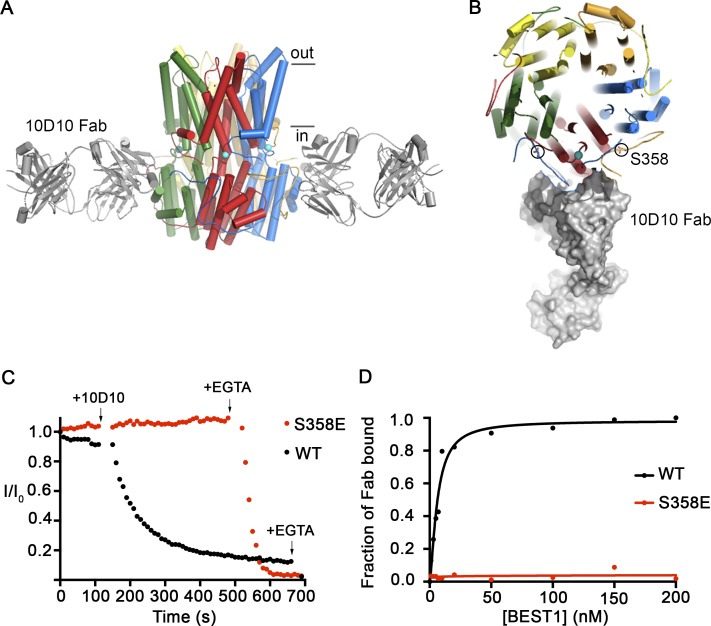

Figure 5.

The 10D10 Fab inhibits ionic currents of BEST1WT but not BEST1S358E. (A) Structure of the BEST1WT–10D10 complex, viewed from the side, showing approximate boundaries of the membrane. For clarity, two 10D10 Fabs are drawn (three are omitted). (B) A slice of the representation from A, viewed from the top, depicting one 10D10 Fab in surface representation (four are omitted for clarity). Two S358 residues from different subunits are circled. (C) The Ca2+-dependent inactivation of BEST1WT and BEST1S358E currents in 10 µM Ca2+ was recorded as described in Fig. 1 A. 200 nM 10D10 Fab was added to both cis and trans sides at the indicated time (arrow; for both BEST1WT and BEST1S358E), followed by the addition of 10 mM EGTA near the end of the experiment (arrow). (D) The relative binding of 10D10 Fab to BEST1WT and BEST1S358E was assayed by determining the amount of free 10D10 Fab as a function of the concentration of BEST1 (Materials and methods). The curves correspond to fits of the following: fraction of Fab bound = [BEST1]h/(Kdh + [BEST1]h), where Kd is the equilibrium dissociation constant, h is the Hill coefficient, and [BEST1] is the total concentration of BEST1. The derived parameters for BEST1WT are Kd ≤ 6 nM and h = 1.5, while BEST1S358E had no detectable binding to the 10D10 Fab.

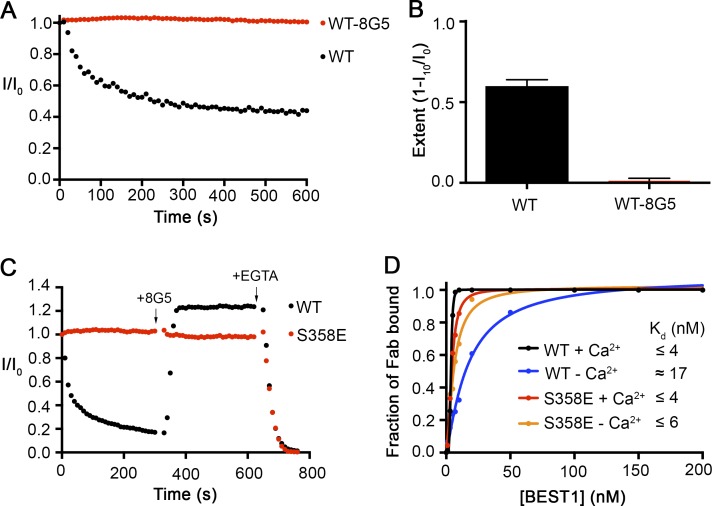

Figure 6.

The 8G5 Fab prevents inactivation of BEST1WT. (A) The Ca2+-dependent inactivation of BEST1WT and BEST1WT–8G5 complex. Recordings were done as described in Fig. 1 A, using 50 µM Ca2+. For the experiment with the 8G5 Fab, after currents for BEST1WT were obtained, 8G5 Fab was added (300 nM final concentration) to the cis and trans chambers, and the chambers were stirred for 2 min before the start of the recording. 50 μM CaCl2 was added at the start (time = 0) of each recording. (B) Extent of inactivation in 50 µM Ca2+ after 10 min is plotted for BEST1WT and the BEST1WT–8G5 complex. Data are derived from A, and at least three separate experiments were performed to calculate SE. (C) Rescue of inactivated BEST1WT channels by 8G5. From time = 0, currents from BEST1WT and BEST1S358E were recorded using 100 µM Ca2+ conditions. At the 5-min mark, 300 nM 8G5 Fab was added to both sides of the bilayer. At the 10-min mark, 10 mM EGTA (final concentration) was added to both sides of the bilayer to chelate free Ca2+. Solutions were stirred for the duration of the experiment. (D) The relative binding of 8G5 Fab to BEST1WT and BEST1S358E was assayed by determining the amount of free 8G5 as a function of the concentration of BEST1 in conditions containing either 10 µM Ca2+ (+Ca2+) or 5 mM EGTA (−Ca2+; Materials and methods). The curves correspond to fits of the following: fraction of Fab bound = [BEST1]h/(Kdh + [BEST1]h), where Kd is the equilibrium dissociation constant, h is the Hill coefficient, and [BEST1] is the total concentration of BEST1. Derived Kd values are indicated.

Limited proteolysis analysis

15 µg purified BEST1 protein at ∼0.6 mg ml−1, in 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 3 mM n-decyl-β-D-maltoside, and ∼10 µM Ca2+ was mixed with 1:556 wt/wt ratio of Asp-N (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The reaction was terminated by addition of 1 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulphonyl fluoride hydrochloride. The samples were heated at 80°C in SDS buffer containing 500 mM dithiothreitol for 5 min before separation by SDS-PAGE using a 12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and then stained using Coomassie blue. For experiments analyzing the Ca2+ dependence of proteolysis, varying concentrations of free Ca2+ were obtained by adding EGTA–Ca buffers (for 10 nM to 750 mM [Ca2+]free) or 5 µM to 1 mM CaCl2 during the reaction. For Western blot analysis, ∼50 ng of BEST1 protein was run on SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Trans-Blot SD; Biorad). Membranes were blocked with 5% milk powder (in TBST solution: 0.1% Tween 20, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) overnight at 4°C and then incubated with 690 ng ml−1 primary antibody (YL1/2) for 1 h at room temperature in TBST containing 2% powdered milk. After three washing steps in TBST milk, the membrane was incubated with 50 ng ml−1 secondary antibody (Goat Anti-rat HRP; Zymed) for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were washed again, and chemiluminescence was detected via enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagent (Luminata Forte; Millipore) using a Chemidoc XRS imager (Biorad).

Results

Purified BEST1 exhibits Ca2+-dependent inactivation

To make comparisons with the structure of chicken BEST1 (Kane Dickson et al., 2014), we recorded currents using purified protein of the same construct (denoted BEST1WT) in planar lipid bilayers. We have shown previously, using planar lipid bilayer electrophysiology, that BEST1WT, which contains amino acids 1–405, recapitulates Ca2+ dependence and anion selectivity properties of human BEST1 (Vaisey et al., 2016). Here we investigate current rundown.

At ∼300 nM [Ca2+]free, and in symmetric 30 mM KCl conditions, ionic currents through BEST1WT generated by 1-s pulses to ±100 mV from a holding voltage of 0 mV were relatively stable over time, decreasing by only ∼11% after 10 min of recording (Fig. 1 B). At higher concentrations of [Ca2+]free, we observed substantial decreases in the ionic currents over time (current rundown) using the same voltage protocol (Fig. 1, A–C). At 100 µM Ca2+, ionic currents were reduced by ∼85% after 10 min.

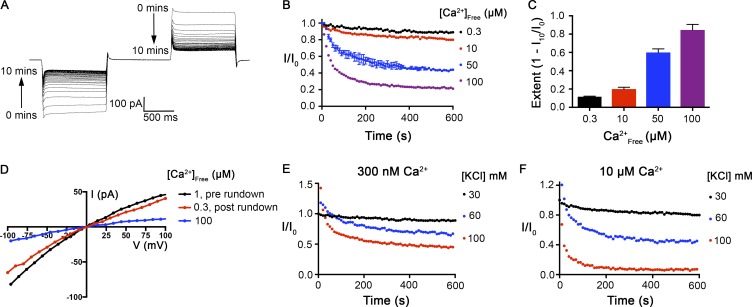

Figure 1.

The Ca2+-dependent inactivation of purified BEST1WT in planar lipid bilayers. (A) Representative current traces. Using symmetric 30 mM KCl and 100 µM Ca2+, currents were recorded with the following protocol: From a holding potential of 0 mV, the voltage was stepped to −100 mV for 1 s, returned to holding for 1 s, and then stepped to +100 mV for 1 s before returning to the holding potential again. This protocol was repeated every 10 s for 10 min with continuous stirring of the solutions. The trace shown here is digitally low-pass filtered to 20 Hz to remove noise caused by stirring. (B) Ionic currents decrease over time as a function of [Ca2+]free. The value of I/I0 is calculated as the current value at ±100 mV at each time point (from 200-ms windows near the end of the 1-s pulses) as a fraction of the current value at the start of the experiment (I0). Desired free Ca2+ concentrations were achieved using 0.21 mM EGTA/0.19 mM CaCl2 for 300 nM Ca2+ or adding additional CaCl2 to solution containing ∼1 µM CaCl2 at the start of the experiment to achieve 10–100 µM free Ca2+. Bath solutions were stirred for the duration of the recordings. Error bars represent ±SD and were derived from three independent experiments shown for the recording at 50 µM [Ca2+]free. (C) Extent of inactivation at each Ca2+ concentration, calculated as 1 − I10/I0, where I10 is the current value observed at the end of the experiment (10 min), as performed in B, and I0 is the current value at the start of the experiment. Values for currents at −100 and +100 mV were averaged. Three independent experiments were used to compute SD. (D) Current rundown is reversible. After 10 mM EGTA was added to the cis chamber to deactivate the channels with their cytosolic regions facing this side of the bilayer, currents were measured in symmetric 30 mM KCl conditions using the following protocol: From a holding potential of 0 mV, the voltage was stepped to test values between −100 and +100 mV, in 10-mV increments, for 2 s at each voltage. After a further 1-s step to −100 mV, the voltage was returned to 0 mV. The I-V relationships were obtained by plotting the test voltages versus average currents (from 200-ms windows) near the end of the 2-s pulses. Recordings were made first using [Ca2+]free of ∼1 µM (prerundown; black). Currents were then recorded 10 min after the addition of 100 µM CaCl2 to the trans chamber (blue). Finally, currents were recorded after perfusion-mediated replacement of the trans chamber with solution containing [Ca2+]free of ∼300 nM (postrundown; red). (E and F) Inactivation depends on [KCl]. Current recordings were made as in B at three different KCl concentrations, as indicated, in solutions containing [Ca2+]free of either ∼300 nM (E) or 10 µM (F).

To test whether current rundown is a reversible property, we induced rundown using 100 µM [Ca2+]free and then restored the [Ca2+]free concentration to 300 nM using perfusion. As shown in Fig. 1 D, most of the current was recovered by returning to 300 nM [Ca2+]free. Because rundown is observed in a reconstituted system using purified BEST1 with minimal buffer components (K+, Na+, Cl−, Ca2+, EGTA, and HEPES; Materials and methods), is dependent on [Ca2+]free, and is reversible, we refer to it as Ca2+-dependent inactivation and conclude that inactivation is an inherent property of the channel.

The dependence of inactivation on [Ca2+]free that we observed is less dramatic than the rundown observed for human BEST1 using whole-cell patch clamp, in which ionic currents decreased by ∼90% after 10 min with 11 µM [Ca2+]free (Xiao et al., 2008). We wondered whether a difference in salt concentration might be responsible for the difference since these previous whole-cell studies used 146 mM CsCl and most of our studies used 30 mM KCl. Indeed, we found that the rate and extent of BEST1 inactivation depends on the concentration of KCl, with higher concentrations causing faster and more extensive inactivation (Fig. 1, E and F). Thus, inactivation is modulated by both [Ca2+]free and [KCl]. In this study, we focus on the effects of Ca2+ on BEST1 inactivation, and unless otherwise noted, recordings were performed using 30 mM KCl, which we note is within the physiological range for intracellular Cl−.

An inactivation peptide and its receptor site

Previous observations by the Hartzell laboratory characterized a C-terminal sequence motif (e.g., amino acids 356IPSFLGS362 of human BEST3) as being autoinhibitory (Qu et al., 2007; Xiao et al., 2008). In the x-ray structure of BEST1WT, the corresponding region (356RPSFLGS362) is contained within the C-terminal tail (amino acids 326–367) of each subunit that adopts an extended conformation and wraps around the cytosolic portion of two adjacent subunits (Fig. 2, A and B). (The amino acids following residue 367 are disordered in the structure.) To begin to investigate the function of this peptide and the C-terminal tail we tested the properties of various C-terminal deletions. We found that a construct spanning amino acids 1–345 of BEST1 does not exhibit inactivation (Fig. 2, C and D). Constructs spanning 1–360 and 1–380 inactivate somewhat but to a lesser extent than BEST1WT (Fig. 2 D). Our data demonstrate a direct role for the C-terminal tail in inactivation, and we now refer to it as the “inactivation peptide.”

To probe more specifically how the inactivation peptide contributes to Ca2+-dependent inactivation, we studied channels with mutations in the 356RPSFLGS362 sequence. From the x-ray structure, we observe that the 356RPSFLGS362 peptide binds to the cytosolic surface of the channel and makes a series of van der Waals and hydrogen-bonding interactions with two different subunits (Fig. 3 A). Of particular note, S358 of the inactivation peptide packs closely with H178 and W309 (Fig. 3, A and D). Phosphorylation of S358 in human BEST1 or the S358E mutation, which would mimic the phosphorylated state, has been shown to prevent current rundown in whole-cell recordings (Xiao et al., 2009). Accordingly, we found that the S358E mutant of chicken BEST1 does not inactivate, whereas the S358A mutant inactivates similarly to BEST1WT (Fig. 3, B and C). Modeling of a glutamate or phosphoserine at position 358 in the x-ray structure produces atomic clashes (Fig. 3 D), and this indicates that the conformation of the inactivation peptide observed in the structure could not be accommodated when S358 is phosphorylated or mutated to glutamate. The logical hypothesis that follows is that disruption of the inactivation peptide from its receptor binding site that was identified in the structure prevents inactivation.

Additional mutagenesis supports this hypothesis. The interactions between the inactivation peptide and its receptor, which involve residues that are conserved between human and chicken BEST1, include a salt bridge between R356 of the inactivation peptide and E306 of one subunit and a hydrophobic interaction between F359 of the inactivation peptide and W229 of another subunit (Fig. 3 A). We find that disruption of the R356–E306 salt bridge by the R356A mutation has a modest effect on inactivation. Disruption of the F359–W229 hydrophobic interaction by introducing an F359A mutation in the inactivation peptide essentially eliminates inactivation. Congruently, the W229A mutation of the receptor site substantially reduces it (Fig. 3 C). Notably, the mutation of W229 to glycine has been identified in patients with Best vitelliform macular dystrophy (Lin et al., 2015).

The aforementioned mutant channels in which inactivation was disrupted possess otherwise normal Ca2+-dependent activation and ion selectivity properties. Currents of BEST1345 and BEST1S358E recorded in asymmetric conditions of 10 mM KCl on the trans side and 30 mM KCl on the cis side of the bilayer gave reversal potentials very close to BEST1WT (BEST1WT = 25.1 ± 0.8 mV, BEST1345 = 23.4 ± 0.3 mV, and BEST1S358E = 24.0 ± 1.0 mV; Fig. 4, A–C), demonstrating indistinguishable selectivity profiles for Cl− versus K+. Chelation of Ca2+ using EGTA abolishes these currents, indicating that the channels are still Ca2+ dependent (Fig. 4, A–C). Furthermore, titration of the [Ca2+]free, using perfusion-mediated solution exchange, activated BEST1S358E and BEST1345 in a dose-dependent manner with similar K1/2 values to BEST1WT (Fig. 4, D–F; Vaisey et al., 2016). For all of the constructs with perturbed C-terminal tails or receptor sites that we tested, we find that channels with disrupted inactivation properties have normal Cl− selectivity and normal Ca2+-dependent activation. Collectively with our previous work showing that distinct regions of the channel control Ca2+-dependent activation and ion selectivity (Vaisey et al., 2016), we conclude that activation, inactivation, and ion selectivity are separate properties that can be disrupted individually by mutations or deletions.

Figure 4.

Chloride-selective, Ca2+-dependent channels are formed by BEST1345 and BEST1S358E. (A–C) Example I-V relationships are shown for voltages stepped from −100 to +100 mV for BEST1WT (A; adapted with permission from Vaisey et al., 2016), BEST1345 (B), and BEST1S358E (C) for indicated conditions (cis/trans KCl concentrations in millimolar and 300 nM Ca2+ [+Ca2+] or 10 mM EGTA [−Ca2+]). (D–F) Reactivation of BEST1 currents by increasing the [Ca2+]free. After observing currents in symmetrical solutions, 10 mM EGTA was added to the cis side to deactivate channels with their cytosolic side facing that direction. Then, using perfusion, the [Ca2+]free in the trans solution was varied from ∼0 to 350 nM with a Ca–EGTA buffer system (Materials and methods). The Ca2+ response curves for BEST1WT (D; adapted from Vaisey et al., 2016), BEST1345 (E), and BEST1S358E (F) are plotted as average currents observed at −100 mV for different [Ca2+]free as a fraction of current recorded from the [Ca2+]free = 350 nM condition (Imax). Three separate experiments were used to calculate SD, and the data were fit to a one-site binding model.

Antibodies that bind to the cytosolic region of the channel modulate inactivation

Our laboratory developed a cohort of monoclonal antibodies against BEST1 as part of our efforts to determine the x-ray structure of the channel and used a Fab fragment of one of these (denoted 10D10) for structure determination (Kane Dickson et al., 2014). The antibodies, which bind to structured regions of the channel, provide potential tools to probe channel function. In the x-ray structure, five 10D10 Fabs bind to the channel (one per subunit) by interacting with a large cytosolic surface that contains portions of the C-terminal tails of two adjacent subunits (amino acids 344–350 of one subunit and 363–365 of another; Fig. 5, A and B). The antibodies are bound at a distance from the pore and would not occlude it. Using bilayer electrophysiology, we found that addition of 10D10 Fab to BEST1WT under conditions that would normally give rise to slow inactivation (10 µM [Ca2+]free) caused ionic currents to diminish rapidly (Fig. 5 C). In contrast, addition of 10D10 during recordings of BEST1S358E, which does not inactivate, had no effect (Fig. 5 C). We determined that this difference in effect is caused by a difference in binding. To assess the binding affinity of the Fab, we incubated the antibody with different amount of BEST1 and quantified the amount of free Fab (Materials and methods). Although 10D10 binds to BEST1WT with high affinity (Kd ≤ 6 nM), it has no apparent binding to BEST1S358E (Fig. 5 D). Interestingly, S358 is ∼14 Å away from the antibody in the structure, ruling out a direct interaction with this residue (Fig. 5 B), but 10D10 does contact other regions of the C-terminal tail. The inability of 10D10 to bind to BEST1S358E supports the hypothesis that the S358E mutation causes a large portion of the C-terminal tail to dislodge, and this disrupts the binding site for 10D10, which includes residues 345–355. On the basis of the binding location of 10D10 and the biochemical and electrophysiological analyses presented herein, we hypothesize that the binding of 10D10 promotes inactivation of the channel and does so by stabilizing the binding of the inactivation peptide to its receptor.

We tested whether other antibodies might have different effects on BEST1 function and identified one Fab (denoted “8G5”) that prevents inactivation. The epitope for 8G5 has not yet been determined, but we suspect that it is on the cytosolic portion of the channel. Currents recorded from BEST1WT were stable after the addition of 8G5 under conditions where BEST1WT would inactivate substantially on its own (50 µM Ca2+; Fig. 6, A and B). Further, we found that 8G5 is able to rescue inactivated BEST1WT channels. After inactivation of BEST1WT to ∼17% of its initial current level (using 100 µM Ca2+), the addition of 8G5 rapidly restored the current level to ∼120% of its initial value, and the currents remained stable over the time course of the experiment (5 min; Fig. 6 C). On the other hand, the addition of 8G5 to BEST1S358E, which does not inactivate, had no effect on current levels (Fig. 6 C). For both BEST1WT and BEST1S358E, the currents were reduced to zero when EGTA was added, which indicates that 8G5 does not prevent deactivation (Fig. 6 C). Unlike 10D10, which we have previously shown binds to BEST1WT with high affinity (Kd ∼15 nM) only in the presence of Ca2+ (Kane Dickson et al., 2014), we found that the 8G5 Fab binds to BEST1WT and BEST1S358E with high affinities both in the presence of Ca2+ and when Ca2+ was removed by EGTA (Fig. 6 D). Thus, the variable effect of 8G5 on BEST1WT and BEST1S358E is caused by differences in the abilities of these channels to inactivate and not because of differences in 8G5 antibody binding.

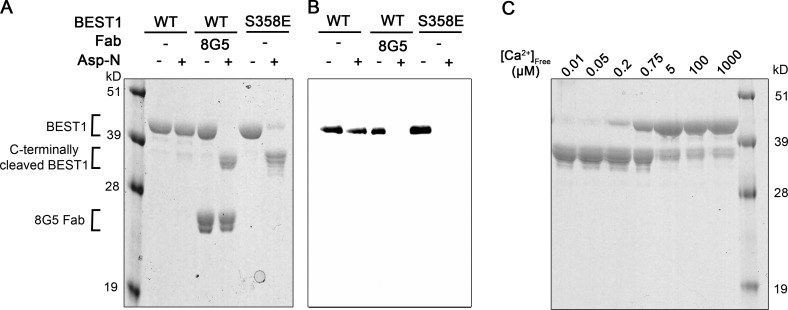

Limited proteolysis supports a link between peptide binding and inactivation

Based on the aforementioned analyses, we hypothesized that the binding of the inactivation peptide to its receptor causes the channel to inactivate and that mutations that disrupt binding impair inactivation. An unlatched peptide—that is, one that is not bound to its receptor site—would presumably be more susceptible to proteolytic cleavage than one that is bound, and so we tested this hypothesis by evaluating the protease susceptibility of constructs that inactivate and those that do not. Detergent-solubilized BEST1WT was resistant to proteolytic cleavage by the endoprotease Asp-N under conditions where we observe inactivation in the bilayer (∼10 µm [Ca2+]free; Fig. 7 A). On the other hand, dramatic cleavage was observed for BEST1S358E, which does not inactivate, under the same conditions (Fig. 7 A). A Western blot using an antibody that recognizes a C-terminal tag indicated that cleavage occurs within the C-terminal region of BEST1S358E (Fig. 7 B), and this was confirmed with mass spectrometry. The data suggest that binding of the inactivation peptide to its receptor causes inactivation. In further support of this hypothesis, we find that varying [Ca2+]free within the range that causes inactivation dramatically affects the proteolytic susceptibility of the C-terminal tail (Fig. 7 C). At >200 nM [Ca2+]free, the C-terminal tail is resistant to cleavage by Asp-N, indicating that it was bound to its receptor, whereas it was readily cleaved at lower [Ca2+]free.

Figure 7.

Conditions or mutations that prevent inactivation result in increased susceptibility of the C-terminal tail to proteolytic cleavage. (A) Protease susceptibility of BEST1WT, BEST1WT-8G5, and BEST1S358E. Purified proteins (in detergent and [Ca2+]free ∼10 µM) were incubated with and without Asp-N endoproteinase for 1 h at room temperature and analyzed by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie staining. Bands corresponding to the 8G5 Fab and to uncleaved and C-terminally cleaved BEST1 are indicated. (B) Western blot of analogous SDS-PAGE gel from A using an antibody (YL1/2) that targets the C-terminal affinity tag used for purification of BEST1. (C) Protease susceptibility depends on [Ca2+]free. SDS-PAGE analysis of BEST1WT that had been treated with Asp-N protease for 1 h at room temperature using different [Ca2+]free.

We wondered if the 8G5 antibody, which prevents inactivation of BEST1WT, would have a similar effect. Indeed, we found that addition of 8G5 to BEST1WT made the C-terminal region of BEST1WT susceptible to proteolytic cleavage by Asp-N (Fig. 7, A and B). These results suggest that binding of the 8G5 Fab or mutagenesis of S358 to glutamate prevent inactivation by disrupting the binding of the inactivation peptide to its receptor.

The neck is the inactivation gate

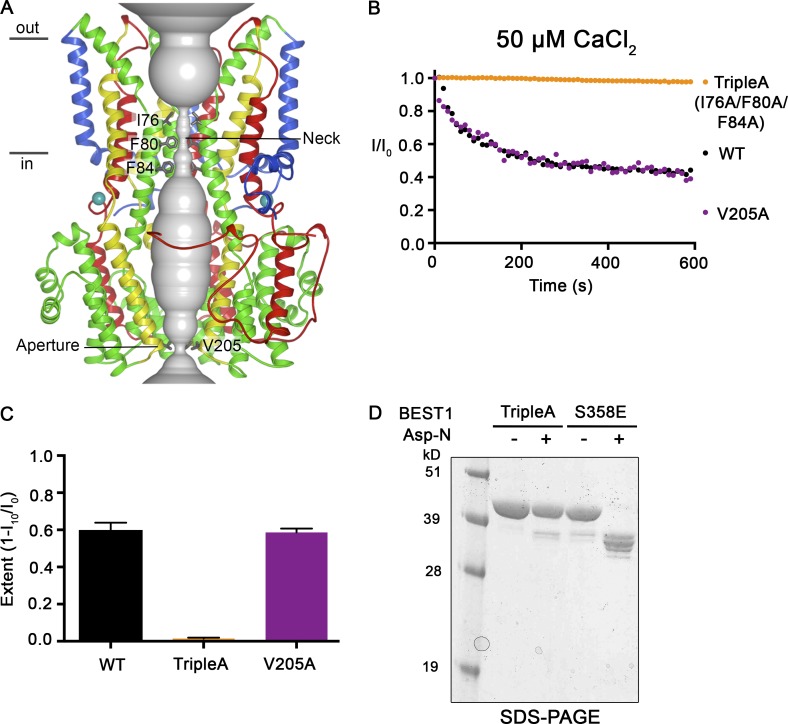

Because the receptor for the inactivation peptide is located on the surface of the channel and distant from the pore, the binding of the inactivation peptide must function to induce conformational changes in the pore that impede ion flow. We sought to identify the region within the pore that constitutes the inactivation gate, that is, the region within the pore that undergoes the conformational changes that impede ion flow during inactivation. Our attention was drawn to the two constrictions in the pore, which seemed to be likely candidates: the neck constriction, the walls of which are lined by three highly conserved hydrophobic residues (I76, F80, and F84) from each subunit, and the aperture, which is less well conserved and lined by the V205 side chains of the subunits (Fig. 8 A; Kane Dickson et al., 2014). We previously showed that the V205A mutation within the aperture has no effect on the Ca2+ dependence of the channel (Vaisey et al., 2016). Instead, the V205A mutation abolishes the lyotropic permeability sequence among anions exhibited by BEST1WT, which indicates that the aperture imparts certain ion selectivity properties to the channel (Vaisey et al., 2016). Fig. 8 shows that ionic currents through BEST1V205A inactivate equivalently to BEST1WT, which suggests that the aperture constriction is not responsible for channel inactivation (Fig. 8, B and C).

Figure 8.

Mutations within the neck, but not within the aperture, prevent Ca2+-dependent inactivation. (A) Structure of BEST1WT with ribbon representations shown for three subunits (two in the foreground are removed for clarity). The ion pore (gray tube) is depicted as a representation of the minimal radial distance from the central axis to the nearest van der Waals protein contact. Secondary structural elements are colored according to the four segments of the channel (S1, blue; S2, green; S3, yellow; and S4 and C-terminal tail, red) that contain corresponding transmembrane regions, and the Ca2+ ions are depicted as teal spheres. Approximate boundaries of a lipid membrane are indicated. (B) The Ca2+-dependent inactivation of BEST1WT, BEST1TripleA (I76A/F80A/F84A), and BEST1V205A, using 50 µM Ca2+, was recorded as described in Fig. 1 A. (C) The extent of inactivation in 50 µM Ca2+ is plotted for BEST1WT, BEST1TripleA, and BEST1V205A. Experiments were performed as in B, and at least three independent experiments were performed to calculate SD. (D) Like BEST1WT, BEST1TripleA is resistant to proteolytic cleavage by Asp-N in the presence of ∼10 µM [Ca2+]free. The BEST1TripleA and BEST1S358E (as a positive control for proteolytic cleavage) were incubated with or without Asp-N for 1 h at room temperature using conditions identical to those for Fig. 7 A. The samples were assayed by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie staining.

Although the neck resembles the classic potassium channel selectivity filter in terms of its narrowness and length, our previous studies demonstrated that the neck is not involved in ion selectivity but instead functions as the activation gate (Vaisey et al., 2016). Mutations of the neck wherein all three hydrophobic residues are replaced with alanine (I76A, F80A, and F84A; denoted “BEST1TripleA”) had no effect on relative ion permeabilities but produced a channel that is constitutively open and did not require Ca2+ for channel activity (Vaisey et al., 2016). Here we show that current recordings of BEST1TripleA do not inactivate (Fig. 8, B and C). A previously determined x-ray structure of BEST1TripleA showed that the only conformational difference from the BEST1WT structure is a widening at the neck caused by the smaller alanine side chains (Vaisey et al., 2016). Of note for the present discussion, Ca2+ ions are bound within the Ca2+ clasps, and the five inactivation peptides, one from each subunit, are bound in their receptor sites in the structure of BEST1TripleA. Like BEST1WT, and unlike BEST1S358E, detergent-solubilized BEST1TripleA does not exhibit susceptibility to cleavage by Asp-N at ∼10 µM [Ca2+]free, further confirming that the inactivation peptide is bound to the channel, even though BEST1TripleA does not inactivate. The TripleA mutant must nullify the effects on the neck that occur in the wild-type channel as a result of the inactivation peptide binding to its receptor. We conclude that the neck functions as both the activation gate and the inactivation gate in bestrophin channels: the neck forms a seal that opens with Ca2+-dependent activation and closes because of Ca2+-dependent inactivation.

Surface-exposed acidic residues may mediate the Ca2+ dependence of inactivation

We next sought to investigate how Ca2+ influences inactivation. The only Ca2+ binding sites that could be identified from the crystallographic analyses, which used Ca2+ concentrations as high as 5 mM, were the Ca2+ clasp binding sites (Kane Dickson et al., 2014). We previously showed that the Ca2+ clasps function as high-affinity Ca2+ sensors (K1/2 ∼17 nM) that underlie the channel’s Ca2+-dependent activation (Vaisey et al., 2016). We observe increases in the rate and extent of inactivation up to concentrations of 1 mM Ca2+ (Fig. 9 A), which suggests that rather than binding to a discrete second site, Ca2+ may be interacting with a more diffuse charged surface. In regions proximal to and including the C-terminal tail, there are several surface-exposed acidic amino acids: E117, D118, E119, D323, E324, E328, E340, and D342 (Fig. 9, B and C). In the x-ray structure these residues create a distinctly electronegative surface that could potentially interact with Ca2+ (Fig. 9 B), and consistent with a diffuse interaction, the residues do not appear geometrically arranged to create a high-affinity Ca2+ binding site (Fig. 9 C). A previous study showed that mutation of one of these in human BEST1 (D323N) produces channels that had less Ca2+-dependent rundown in whole-cell recordings (Xiao et al., 2008). In accord with these findings, we observe that BEST1D323N inactivates to a lesser extent than BEST1WT (Fig. 9, D and E). The effect is greater when D323 is mutated alanine (Fig. 9, D and E). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that the Ca2+ dependence of inactivation results from Ca2+ interacting with D323 and the other nearby acidic residues. Although additional analysis is needed, the proximity of the electronegative patch to the receptor site for the inactivation peptide suggests a mechanism whereby Ca2+ interaction with the electronegative patch promotes and/or stabilizes the binding of the inactivation peptide to its receptor.

Figure 9.

Surface-exposed acidic residues near the inactivation peptide may underlie the Ca2+ dependence of inactivation. (A) The Ca2+-dependent inactivation of BEST1WT as shown in Fig. 1 A, with additional recordings using 500 µM and 1 mM [Ca2+]free. (B) Surface representation of BEST1 colored by electrostatic potential. Red, −5 kT e−1; white, neutral; blue, +5 kT e−1. (C) Structure of BEST1 with same perspective as in B. The C-terminal tail of one subunit is shown in blue. Acidic residues that create an electronegative patch on the surface are drawn as red sticks. The Ca2+ ions in the Ca2+ clasps are shown as magenta spheres. (D) The Ca2+-dependent inactivation of BEST1WT, BEST1D323A, and BEST1D323N. Recordings were made as described in Fig. 1 A using 50 µM Ca2+. (E) Extent of inactivation in 50 µM Ca2+. Experiments were performed as in D, and at least three independent experiments were performed to calculate SD.

Discussion

In this study we have used bilayer recordings to show that the BEST1 channel inactivates. Using the x-ray structure of BEST1 as a framework, recordings of wild-type and mutant channels have enabled identification of the regions of the channel involved in inactivation and provide insight into the molecular mechanisms of this regulatory behavior.

Electrophysiological recordings of purified BEST1 channels with truncations or point mutations demonstrate the essential role of the C-terminal tail in inactivation. Inactivation is disabled by truncating the C-terminal tail at amino acid 345, by mutation of S358 within the C-terminal tail to glutamate, by mutation of the neighboring F359 to alanine, or by mutation of W229 to alanine within its receptor site. Inactivation is also prevented by binding of a Fab antibody fragment (8G5). When the 8G5 antibody is bound to BEST1WT or when S385 is mutated to glutamate (BEST1S358E), the C-terminal tail becomes dramatically susceptible to proteolysis. These findings suggest that disruptions to the tail that alter its interaction with the channel prevent inactivation. Thus, the C-terminal tail acts as a regulatory appendage to the BEST1 channel, reminiscent of the ball and chain, or N-type, inactivation mechanism of voltage-gated channels (Armstrong and Bezanilla, 1977; Hille, 2001; Zhou et al., 2001). However, rather than acting as a pore blocker, as is well established for the inactivation peptide of voltage-gated channels (Choi et al., 1991; Zhou et al., 2001), we propose that the C-terminal tail of BEST1 acts as an inactivation peptide through an allosteric mechanism. In BEST1, binding of the inactivation peptide to its receptor on the cytosolic surface of BEST1 causes inactivation by inducing conformational changes within the pore. In lieu of additional structural information, we do not know with certainty what state of the channel the previously determined x-ray structure of BEST1 represents (Kane Dickson et al., 2014), but based on the narrow dimensions of the neck, the bound C-terminal tail, and the fact that the structure is determined in complex with the 10D10 Fab that seems to enhance inactivation, the x-ray structure most likely represents a Ca2+-bound inactivated state.

S358 is perfectly conserved among human BEST1–4, and there is considerable conservation of the inactivation peptide sequence and its receptor site. This sequence conservation suggests that all bestrophin channels undergo some extent of inactivation. The sequence variations in these regions also seem to engender the channels with different properties. For instance, currents through BEST3 have been difficult to record at all unless the region corresponding to the inactivation peptide is removed or altered (Qu et al., 2006, 2007). Distinct inactivation behaviors of bestrophin channels may add to the breadth and intricacy of the physiological functions of this family of channels.

Our data indicate that the neck within the pore acts as the inactivation gate. On the basis of the dimensions of the neck in the x-ray structure of BEST1 and the hydrophobic nature of the residues that form the walls of the neck (I76, F80, and F84), we hypothesize that the neck acts to prevent ions from flowing through it because it is simply too narrow for hydrated ions to fit within it. This hydrophobic seal mechanism has been proposed previously for BEST1 on the basis of the dimensions of the neck in the structure (Aryal et al., 2015; Rao et al., 2017). We have previously shown the neck functions as the activation gate by controlling the flow of Cl− though the pore in a Ca2+-dependent manner (Vaisey et al., 2016). Thus, in the wild-type channel, the neck functions as a variable constriction within the pore that is responsible for both Ca2+-dependent activation and Ca2+-dependent inactivation. A hypothetical scheme is illustrated in Fig. 10. At low concentrations of Ca2+, the Ca2+ clasps are empty and the neck is sealed shut; this corresponds to a closed, nonconductive state of the ion pore. The binding of Ca2+ ions to the clasps causes local changes that induce changes within the neck, which presumably include its widening, and these transition the channel into a conductive—open or activated—state. The natures of the conformational changes within the Ca2+ clasp and the neck, and their magnitudes, are not yet clear. After opening, the channel begins to inactivate, and higher concentrations of Ca2+ increase the rate and extent of inactivation. Inactivation involves binding of the C-terminal tail—the inactivation peptide—to its cytosolic receptor located on the surface of the channel.

Figure 10.

Hypothesized mechanisms for activation and inactivation in bestrophin channels. In the Ca2+-free state of the channel the neck is sealed shut, and the channel is nonconductive. The binding of Ca2+ ions to the high-affinity Ca2+ clasps causes dilation of the neck, which now permits ions to flow through it. In both the Ca2+-free closed and Ca2+-bound open states, the inactivation peptides (one from each subunit) are not engaged with their receptors. In the presence of higher (e.g., μM) concentrations of Ca2+, the inactivation peptides bind to their receptor sites on the cytosolic surface of the channel (the dashed line indicates that this tail binds on the back surface). Inactivation peptide binding causes conformational changes in the channel that allosterically control the conformation of the neck of the pore, causing it to transition into a nonconductive conformation. The aperture does not have a role in activation or inactivation. Instead, the aperture functions as a size-selective filter that permits the passage of small ions and requires them to become at least partially dehydrated as they move through it and thereby gives rise to the lyotropic sequence of permeability among permeant anions (Vaisey et al., 2016).

Although further study is needed to be conclusive, our data suggest that a patch of acidic residues on the cytosolic surface of the channel, which include D323, are involved in the Ca2+ dependence of inactivation, in that Ca2+ interaction with this region stimulates and/or stabilizes the binding of the inactivation peptide to its receptor. The binding of the inactivation peptide to its receptor induces conformational changes in the neck that seal it shut. The gating processes are reversible; lowering the Ca2+ concentration can restore inactivated channels to activated ones and also deactivated ones depending on the ultimate Ca2+ concentration.

Similar to inactivation in voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels, inactivation in BEST1 follows the open state of the channel. A key difference is that although transitions to the inactivated state in voltage-gated channels are largely independent of voltage, and thus, inactivation is primarily state dependent (Armstrong and Bezanilla, 1977; Hille, 2001), inactivation of BEST1 is strongly dependent on [Ca2+]free. The concentrations of Ca2+ that cause inactivation of BEST1 are orders of magnitude higher than what is necessary for activation, and this suggests that that inactivation in bestrophin channels is caused by a process that is distinct from activation.

It is clear from our data presented here and previously (Vaisey et al., 2016) that the aperture is not responsible for either activation or inactivation. Mutations of the aperture can have dramatic effects on ion selectivity, but they have had no effect on activation or inactivation properties of the channels. All of the data thus far suggest that the aperture remains relatively fixed in size throughout the gating transitions and functions as a size-selective filter that prevents large anions and other species from permeating through the channel; this property gives BEST1 its characteristic lyotropic sequence of anion permeability (Vaisey et al., 2016).

Various lines of evidence suggest that inactivation of bestrophin channels has physiological relevance. Whole-cell recordings of human BEST1 in HEK239 cells demonstrated that changes in cell volume modulate the rundown of BEST1 currents, which we now know is caused by inactivation, and that the phosphorylation state of S358 within the inactivation peptide is involved in this process (Xiao et al., 2009). The S358 residue in human BEST1 can be phosphorylated by PKC and dephosphorylated by protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A; Xiao et al., 2009). Dephosphorylation of S358 would favor inactivation, and this at least partially underlies the inhibition of human BEST1 that is observed when cells are exposed to hypertonic solutions (Xiao et al., 2009). Furthermore, ceramide, which is released during cell shrinkage, is an activator of PP2A and can mimic the effects of hypertonic stress (Xiao et al., 2009). Although the regulation of S358 phosphorylation in vivo is not fully understood, it has been shown that human BEST1 coimmunoprecipitates with PP2A in RPE cells (Marmorstein et al., 2002). Thus, the inactivation of BEST1 and its modulation by PKC and PP2A may be important regulatory mechanisms in the physiology of RPE cells. In addition to inactivation depending on the cytosolic concentration of Ca2+ and the phosphorylation state of S358, it is clear from our experiments that the concentration of KCl modulates inactivation, with higher (>30 mM) concentrations increasing its extent and kinetics. This dependence on the salt concentration, and possibly Cl− in particular, may also contribute to volume-regulating properties of BEST1 in physiologically relevant ways.

Approximately 200 mutations in BEST1 have been associated with retinal degenerative disorders (Hartzell et al., 2008). Those mutations that have been characterized are predominantly associated with reduced Cl− currents (Sun et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2006, 2007; Marchant et al., 2007; Davidson et al., 2009; Milenkovic et al., 2011), but most of the mutations remain unstudied, and some of these could affect BEST1 inactivation. A fairly recent study identified a mutation of BEST1 in a patient with autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy that produced currents that were actually larger than the wild-type channel when expressed in HEK293 cells (Johnson et al., 2015). This mutation causes a frame shift that produces a channel comprising only the first 366 amino acids. Based on the findings presented here and previously by the Hartzell laboratory, this mutant would have impaired inactivation, which further suggests that defects in inactivation of BEST1 may be pathological.

Current rundown is a commonly observed phenomenon among ion channels (Becq, 1996) and also occurs in TMEM16A, another Ca2+-activated Cl− channel (Ni et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2014; Dang et al., 2017) . Rundown can represent an intrinsic property of the channel or be caused by the depletion of cellular factors that are necessary for channel activity. Here, using a reconstituted system, we have shown that current rundown in BEST1 is caused by inactivation and is an intrinsic property of the channel. The extent and kinetics of inactivation depend on the cytosolic concentration of Ca2+, and inactivation can occur under physiological levels of Ca2+. We have identified a C-terminal peptide that is necessary for inactivation and identified its receptor site on BEST1. Our data indicate that binding of the inactivation peptide to its receptor causes the channel to inactivate through an allosteric mechanism by closing a structurally distant gate that resides in the neck of the pore. Mutations of the inactivation peptide, mutations of its receptor site, or mutations within the neck can prevent inactivation. Additionally, our experiments point to the involvement of an acidic cytosolic region in how cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations modulate inactivation. These studies provide a framework to further understand the molecular mechanisms and physiological roles of bestrophin channels.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to David Gadsby (Rockefeller University) for helpful discussions. We thank the staff of the microchemistry and proteomics core at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

G. Vaisey received funding and mentorship from the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds Predoctoral Fellowship Program. This work was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health grant R01 GM110396 (to S.B. Long) and a core facilities support grant to Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (P30 CA008748).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: G. Vaisey and S.B. Long conceived of and designed the project. G. Vaisey performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and prepared the figures. G. Vaisey and S.B. Long wrote the manuscript.

Kenton J. Swartz served as editor.

References

- Armstrong C.M., and Bezanilla F.. 1977. Inactivation of the sodium channel. II. Gating current experiments. J. Gen. Physiol. 70:567–590. 10.1085/jgp.70.5.567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryal P., Sansom M.S.P., and Tucker S.J.. 2015. Hydrophobic gating in ion channels. J. Mol. Biol. 427:121–130. 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakall B., McLaughlin P., Stanton J.B., Zhang Y., Hartzell H.C., Marmorstein L.Y., and Marmorstein A.D.. 2008. Bestrophin-2 is involved in the generation of intraocular pressure. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49:1563–1570. 10.1167/iovs.07-1338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becq F. 1996. Ionic channel rundown in excised membrane patches. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1286:53–63. 10.1016/0304-4157(96)00002-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers D.M., Patton C.W., and Nuccitelli R.. 1994. A practical guide to the preparation of Ca2+ buffers. Methods Cell Biol. 40:3–29. 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)61108-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess R., Millar I.D., Leroy B.P., Urquhart J.E., Fearon I.M., De Baere E., Brown P.D., Robson A.G., Wright G.A., Kestelyn P., et al. . 2008. Biallelic mutation of BEST1 causes a distinct retinopathy in humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82:19–31. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K.L., Aldrich R.W., and Yellen G.. 1991. Tetraethylammonium blockade distinguishes two inactivation mechanisms in voltage-activated K+ channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 88:5092–5095. 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang S., Feng S., Tien J., Peters C.J., Bulkley D., Lolicato M., Zhao J., Zuberbühler K., Ye W., Qi L., et al. . 2017. Cryo-EM structures of the TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel. Nature. 552:426–429. 10.1038/nature25024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson A.E., Millar I.D., Urquhart J.E., Burgess-Mullan R., Shweikh Y., Parry N., O’Sullivan J., Maher G.J., McKibbin M., Downes S.M., et al. . 2009. Missense mutations in a retinal pigment epithelium protein, bestrophin-1, cause retinitis pigmentosa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 85:581–592. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischmeister R., and Hartzell H.C.. 2005. Volume sensitivity of the bestrophin family of chloride channels. J. Physiol. 562:477–491. 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell H.C., Qu Z., Yu K., Xiao Q., and Chien L.-T.. 2008. Molecular physiology of bestrophins: Multifunctional membrane proteins linked to best disease and other retinopathies. Physiol. Rev. 88:639–672. 10.1152/physrev.00022.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. 2001. Ion channels of excitable membranes. Sinauer Associates Incorporated, Sunderland, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A.A., Bachman L.A., Gilles B.J., Cross S.D., Stelzig K.E., Resch Z.T., Marmorstein L.Y., Pulido J.S., and Marmorstein A.D.. 2015. Autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy is not associated with the loss of bestrophin-1 anion channel function in a patient with a novel BEST1 mutation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 56:4619–4630. 10.1167/iovs.15-16910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane Dickson V., Pedi L., and Long S.B.. 2014. Structure and insights into the function of a Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-) channel. Nature. 516:213–218. 10.1038/nature13913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmartin J.V., Wright B., and Milstein C.. 1982. Rat monoclonal antitubulin antibodies derived by using a new nonsecreting rat cell line. J. Cell Biol. 93:576–582. 10.1083/jcb.93.3.576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhang Y., Xu Y., Kittredge A., Ward N., Chen S., Tsang S.H., and Yang T.. 2017. Patient-specific mutations impair BESTROPHIN1's essential role in mediating Ca2+-dependent Cl- currents in human RPE. eLife. 6:e29914 10.7554/eLife.29914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y., Gao H., Liu Y., Liang X., Liu X., Wang Z., Zhang W., Chen J., Lin Z., Huang X., and Liu Y.. 2015. Two novel mutations in the bestrophin-1 gene and associated clinical observations in patients with best vitelliform macular dystrophy. Mol. Med. Rep. 12:2584–2588. 10.3892/mmr.2015.3711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant D., Yu K., Bigot K., Roche O., Germain A., Bonneau D., Drouin-Garraud V., Schorderet D.F., Munier F., Schmidt D., et al. . 2007. New VMD2 gene mutations identified in patients affected by Best vitelliform macular dystrophy. J. Med. Genet. 44:e70 10.1136/jmg.2006.044511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein L.Y., McLaughlin P.J., Stanton J.B., Yan L., Crabb J.W., and Marmorstein A.D.. 2002. Bestrophin interacts physically and functionally with protein phosphatase 2A. J. Biol. Chem. 277:30591–30597. 10.1074/jbc.M204269200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt A., Stöhr H., Passmore L.A., Krämer F., Rivera A., and Weber B.H.. 1998. Mutations in a novel gene, VMD2, encoding a protein of unknown properties cause juvenile-onset vitelliform macular dystrophy (Best’s disease). Hum. Mol. Genet. 7:1517–1525. 10.1093/hmg/7.9.1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic A., Brandl C., Milenkovic V.M., Jendryke T., Sirianant L., Wanitchakool P., Zimmermann S., Reiff C.M., Horling F., Schrewe H., et al. . 2015. Bestrophin 1 is indispensable for volume regulation in human retinal pigment epithelium cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 112:E2630–E2639. 10.1073/pnas.1418840112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic V.M., Röhrl E., Weber B.H.F., and Strauss O.. 2011. Disease-associated missense mutations in bestrophin-1 affect cellular trafficking and anion conductance. J. Cell Sci. 124:2988–2996. 10.1242/jcs.085878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C. 2013. Ion channel reconstitution. Springer Science & Business Media, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y.-L., Kuan A.-S., and Chen T.-Y.. 2014. Activation and inhibition of TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channels. PLoS One. 9:e86734 10.1371/journal.pone.0086734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrukhin K., Koisti M.J., Bakall B., Li W., Xie G., Marknell T., Sandgren O., Forsman K., Holmgren G., Andreasson S., et al. . 1998. Identification of the gene responsible for Best macular dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 19:241–247. 10.1038/915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z., Wei R.W., Mann W., and Hartzell H.C.. 2003. Two bestrophins cloned from Xenopus laevis oocytes express Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-) currents. J. Biol. Chem. 278:49563–49572. 10.1074/jbc.M308414200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z., Fischmeister R., and Hartzell C.. 2004. Mouse bestrophin-2 is a bona fide Cl(-) channel: Identification of a residue important in anion binding and conduction. J. Gen. Physiol. 123:327–340. 10.1085/jgp.200409031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z., Cui Y., and Hartzell C.. 2006. A short motif in the C-terminus of mouse bestrophin 3 [corrected] inhibits its activation as a Cl channel. FEBS Lett. 580:2141–2146. 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z.Q., Yu K., Cui Y.-Y., Ying C., and Hartzell C.. 2007. Activation of bestrophin Cl- channels is regulated by C-terminal domains. J. Biol. Chem. 282:17460–17467. 10.1074/jbc.M701043200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao S., Klesse G., Stansfeld P.J., Tucker S.J., and Sansom M.S.P.. 2017. A BEST example of channel structure annotation by molecular simulation. Channels (Austin). 11:347–353. 10.1080/19336950.2017.1306163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenmakers T.J., Visser G.J., Flik G., and Theuvenet A.P.. 1992. CHELATOR: an improved method for computing metal ion concentrations in physiological solutions. Biotechniques. 870–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon J.M., Afshari M.A., Sharma S., Bernstein P.S., Chong S., Hutchinson A., Petrukhin K., and Allikmets R.. 2001. Assessment of mutations in the Best macular dystrophy (VMD2) gene in patients with adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy, age-related maculopathy, and bull’s-eye maculopathy. Ophthalmology. 108:2060–2067. 10.1016/S0161-6420(01)00777-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H., Tsunenari T., Yau K.-W., and Nathans J.. 2002. The vitelliform macular dystrophy protein defines a new family of chloride channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:4008–4013. 10.1073/pnas.052692999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunenari T., Sun H., Williams J., Cahill H., Smallwood P., Yau K.-W., and Nathans J.. 2003. Structure-function analysis of the bestrophin family of anion channels. J. Biol. Chem. 278:41114–41125. 10.1074/jbc.M306150200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaisey G., Miller A.N., and Long S.B.. 2016. Distinct regions that control ion selectivity and calcium-dependent activation in the bestrophin ion channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 113:E7399–E7408. 10.1073/pnas.1614688113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q., Prussia A., Yu K., Cui Y.-Y., and Hartzell H.C.. 2008. Regulation of bestrophin Cl channels by calcium: Role of the C terminus. J. Gen. Physiol. 132:681–692. 10.1085/jgp.200810056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q., Yu K., Cui Y.-Y., and Hartzell H.C.. 2009. Dysregulation of human bestrophin-1 by ceramide-induced dephosphorylation. J. Physiol. 587:4379–4391. 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley J., Leroy B.P., Hart-Holden N., Lafaut B.A., Loeys B., Messiaen L.M., Perveen R., Reddy M.A., Bhattacharya S.S., Traboulsi E., et al. . 2004. Mutations of VMD2 splicing regulators cause nanophthalmos and autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy (ADVIRC). Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45:3683–3689. 10.1167/iovs.04-0550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K., Cui Y., and Hartzell H.C.. 2006. The bestrophin mutation A243V, linked to adult-onset vitelliform macular dystrophy, impairs its chloride channel function. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47:4956–4961. 10.1167/iovs.06-0524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K., Qu Z., Cui Y., and Hartzell H.C.. 2007. Chloride channel activity of bestrophin mutants associated with mild or late-onset macular degeneration. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48:4694–4705. 10.1167/iovs.07-0301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K., Zhu J., Qu Z., Cui Y.Y., and Hartzell H.C.. 2014. Activation of the Ano1 (TMEM16A) chloride channel by calcium is not mediated by calmodulin. J. Gen. Physiol. 143:253–267. 10.1085/jgp.201311047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M., Morais-Cabral J.H., Mann S., and MacKinnon R.. 2001. Potassium channel receptor site for the inactivation gate and quaternary amine inhibitors. Nature. 411:657–661. 10.1038/35079500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]