Abstract

Acute kidney injury, which is caused by renal ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI), occurs in several clinical situations and causes severe renal damage. There is no effective therapeutic agent available for renal IRI at present. In this study, we performed an experiment based on an in vivo murine model of renal IRI to examine the effect of carnosol. Thirty Sprague-Dawley rats were randomized into three groups (10 rats in each group): the sham, IRI, and carnosol groups. Rats in the carnosol group were injected intravenously with 3 mg/kg of carnosol, and those in the sham and IRI groups were injected intravenously with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide 1 h before ischemia. Rats were sacrificed after 24 h of reperfusion. The blood and kidneys were harvested, renal function was assessed, and histologic evaluation was performed to analyze renal injury. A renal myeloperoxidase activity assay, in-situ apoptosis examination, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunohistochemical assay, and western blot were also performed. Carnosol pretreatment significantly reduced renal dysfunction and histologic damage induced by renal IRI. Carnosol pretreatment suppressed renal inflammatory cell infiltration and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression. In addition, carnosol markedly inhibited apoptotic tubular cell death, caspase-3 activation, and activation of the p38 pathway. Carnosol pretreatment protects rats against renal IRI by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis. Although future investigation is needed, carnosol may be a potential therapeutic agent for preventing renal IRI.

Keywords: apoptosis, inflammation, ischemia-reperfusion injury, kidney

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) caused by renal ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) has frequently been reported by urologists and nephrologists in many clinical situations in the last 2 decades. Nowadays, AKI has become a big problem for both urologists and nephrologists, since it has prolonged the time of hospital stays, reduced the survival rates, and increased the cost of patient cares [3, 15, 28]. Scientists have taken great effort to examine the effect of diverse agents on AKI. However, to our knowledge, there is no effective therapeutic agent available for AKI at present [1, 22]. In consideration of the high accidence of renal IRI in urologic surgeries and renal transplantation, new therapeutic agents are urgently needed to attenuate organ damage induced by AKI.

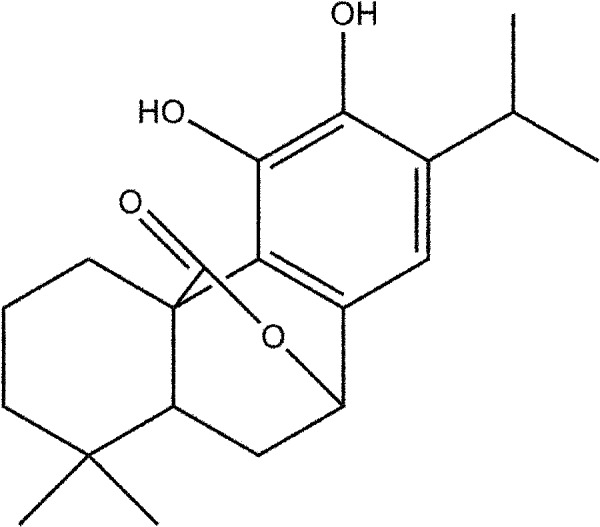

Recently, a series of natural products obtained from plants or traditional Chinese medicines have been used to prevent renal IRI in diverse experimental studies [8, 17, 32]. The mechanisms of renal IRI are known to be related to renal inflammation, oxidative stress, and tubular cell necrosis and/or apoptosis [6, 15, 22]. Thus, natural products that possess anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, or antioxidative activities are worth being examined as potential therapeutic agents in experimental AKI studies. Carnosol (Fig. 1), which is a phenolic diterpene extracted from several dietary herbs, including rosemary, has been reported to possess anticancer activity in a series of studies [11, 24]. Recent reports demonstrated that carnosol may have significant anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects and may protect diverse organs against IRI [18, 25, 31]. Yao et al. [30] reported that carnosol attenuated intestinal IRI-induced hepatic damage through the attenuation of inflammatory mediator production. Tian et al. [27] reported that carnosol markedly ameliorated lung injury induced by intestinal IRI, by inhibiting inflammatory cell infiltration in lung tissues. Therefore, we hypothesized that carnosol may provide a protective effect against renal IRI through its anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic activities. To examine our hypothesis, we performed an experiment based on an in vivo murine model of renal IRI to investigate the potential effect and mechanisms of carnosol.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of carnosol. Carnosol is a phenolic diterpene extracted from several dietary herbs, including rosemary. Its molecular formula is C20H26O4. The formula weight is 330.4.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Carnosol was purchased from the Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody (rabbit anti-rat) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (1:3,000; Beverly, MA, USA). Anti-ED-1 antibody was purchased from AbD Serotec (1:25; Oxford, UK ). The rabbit polyclonal anti-rat p38 or phosphorylated-p38 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (1:1,000; Beverly, MA, USA).

Animals and experimental protocol

All experimental procedures were performed according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) guidelines for the use of laboratory animals and approved by the Ethics Committee of Experimental Animals of Zhejiang University (No. SYXK-2015-0010). Thirty male Sprague Dawley rats (200–260 g) with a mean age of 6 weeks were given free access to rodent diet and water. Rats were randomly assigned to three groups: the sham group (Sham, n=10), IRI group (IRI, n=10), and carnosol group (Car, n=10). Rats in the carnosol group were injected intravenously with 3 mg/kg of carnosol, and those in the sham and IRI groups were injected intravenously with 3 mg/kg of 10% dimethyl sulfoxide 1 h before renal ischemia. The dose and route of carnosol in this study were chosen based on previous reports and a preliminary study we conducted [27, 30].

Renal IRI model

The renal IRI model was previously described [5]. In brief, rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (45 mg/kg). A midline abdominal incision was made, followed by right nephrectomy. The left renal artery was occluded with a nontraumatic microvascular clamp for 45 min, followed by reperfusion for 24 h. Rats in the sham group underwent the same procedure without clamping the left renal artery. During the experiment, we used a heating pad to maintain the body temperature of rats between 36 and 37°C. Rats were then sacrificed 24 h after reperfusion, and the blood and left kidney were collected for analysis.

Renal function assessment

We examined serum creatinine (Scr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels to evaluate renal function. The samples were measured using an Olympus analyzer (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Renal histologic evaluation

Kidney tissues were fixed using 4% buffered paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections (4 µm in thickness) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for routine histopathologic examination. Semiquantitative evaluation of tissue damage was performed by a pathologist in a blind manner, based on previously described criteria [16, 20]. Ten randomly selected high-power fields (magnification, ×400) per section were evaluated and scored. The total histologic score for each section was calculated by adding all the scores.

Renal myeloperoxidase activity assessment

Renal myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity is known as a marker of inflammatory cell infiltration [5]. Thus, we examined it using a commercial assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) as previously described [8].

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Kidney tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) levels were measured using ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Apoptosis assessment

Apoptosis in the kidneys was examined using a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay with a commercial kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) based on the manufacturer’s guidelines. The number of apoptotic cells was counted in ten randomly selected high-power fields (magnification, ×400) per section in a blinded manner.

Immunohistochemical analysis

We used paraffin-embedded renal tissue sections to perform the immunohistochemical analysis. Briefly, 4-µm paraffin sections were deparaffinized, heated in citrate buffer (0.01 M, pH=6.0) for 10 min using a microwave oven, and then incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against ED-1 (1:25, Serotec, Oxford, UK ) or cleaved caspase-3 (rabbit anti-rat) (1:3,000, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA). Antibody binding was detected using an EnVision Detection Kit (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Positively stained cells were quantified by counting cells in ten randomly selected high-power fields (magnification, ×400) per section in a blinded manner.

Western blot

Kidney p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) expression was detected using a Western blot assay. The primary antibody was rabbit polyclonal anti-rat p38 or phosphorylated-p38. The secondary antibody was peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody. Proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence technology and analyzed with the Image J software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0 software (IBM corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All values were reported as means ± SE of the mean (SEM) values. In group comparisons, one-way analysis of variance followed by a Tukey post hoc test and nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Effect of carnosol on renal IRI-induced renal damage

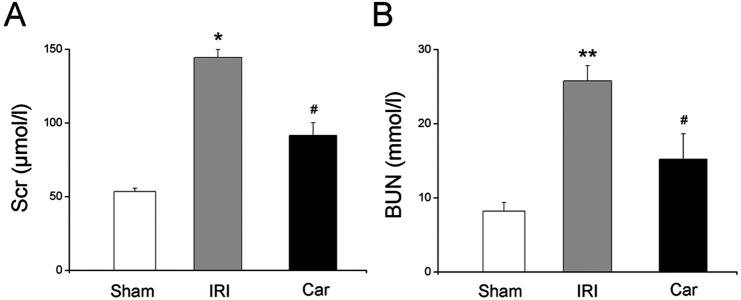

To evaluate the effect of carnosol on IRI-induced renal damage, we examined BUN and Scr levels, the major markers of renal function, in all three groups. Our data showed that renal IRI significantly elevated both BUN and Scr levels of rats (P<0.05). A single dose of carnosol markedly attenuated renal function of rats, which was reflected by the substantial reduction of BUN and Scr levels, compared with those of the IRI group (P<0.05, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The effect of carnosol pretreatment on renal function. (A) Serum creatinine levels. (B) Blood urea nitrogen levels. Bars represent means ± SE; N=10 rats per group. * P<0.05 vs. the sham group; ** P<0.01 vs. the sham group; # P<0.05 vs. the IRI group.

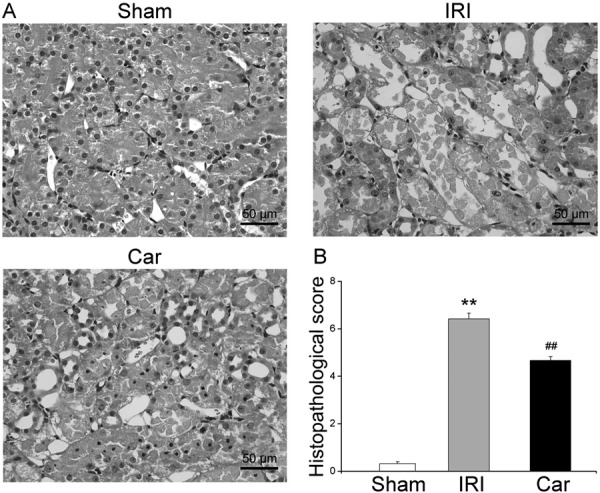

The results of histologic examination further confirmed the attenuation of renal damage by carnosol. H&E-stained sections of rat kidneys from the sham group had a normal tubular appearance, whereas those from the IRI group showed changes indicative of severe tubular cell necrosis, including tubular cell dilation, medullary hemorrhage, and tubular destruction. On the other hand, sections of rat kidneys from the carnosol group displayed less extensive areas of tubular cell necrosis (Fig. 3A). The appearance of tubular cells was also improved by carnosol pretreatment. The results of semiquantitative histologic evaluation showed that carnosol markedly reduced the tubular injury score, from 6.4 ± 0.6 to 4.7 ± 0.4 (P<0.05, Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

The effect of carnosol pretreatment on renal damage. (A) Photos of H&E staining of kidney tissue sections from the sham group, IRI group, and Car group (magnification: ×400). Sections from the sham group had a normal tubular appearance, whereas sections from the IRI group showed severe tubular epithelial cell necrosis. Pretreatment with carnosol significantly improved the above histologic changes. (B) The results of semiquantitative histopathological evaluation confirmed that carnosol significantly reduced the tubular injury score. Bars represent means ± SE; N=10 rats per group. ** P<0.01 vs. the sham group; ## P<0.01 vs. the IRI group.

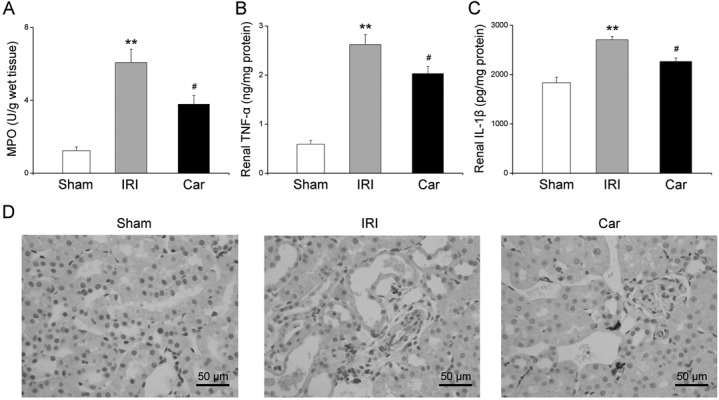

Effect of carnosol on renal IRI-induced inflammatory cell infiltration in kidneys

To evaluate the effect of carnosol on renal IRI-induced inflammation, we examined the level of renal MPO, a major marker of inflammatory cell infiltration. Our data demonstrated that renal IRI induced a substantial increase in the renal MPO level from 1.2 ± 0.2 U/g to 6.1 ± 0.7 U/g compared with that in the sham group (P<0.01). Carnosol pretreatment significantly attenuated the renal MPO level to 3.8 ± 0.5 U/g compared with that in the IRI group (P<0.05, Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

The effect of carnosol pretreatment on renal inflammation. (A) Renal MPO levels. (B) TNF-α levels and (C) IL-1β levels in kidney tissues were examined by ELISA assay. (D) Photos of immunohistochemical staining of ED-1 in rats from the sham group, IRI group, and Car group (magnification: ×400). Bars represent means ± SE; N=10 rats per group. ** P<0.01 vs. the sham group; # P<0.05 vs. the IRI group.

We then examined renal monocyte/macrophage infiltration using ED-1 (a specific monocyte/macrophage marker) immunostaining. As shown in Fig. 4D, the number of cells positively stained for ED-1 was markedly increased in the kidneys of rats in the IRI group, whereas carnosol pretreatment significantly reduced the number of cells positively stained for ED-1.

Effect of carnosol on renal IRI-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in the kidneys

We examined the renal expression of TNF-α and IL-1β, which have been considered the most prominent pro-inflammatory cytokines, using ELISA. Our data showed that renal IRI caused markedly higher expression of both TNF-α and IL-1β in kidney tissues compared with the levels in the sham group (P<0.01). On the other hand, carnosol pretreatment significantly attenuated the increase in TNF-α and IL-1β expression in kidney tissues compared with the levels in the IRI group (P<0.05, Figs. 4B and C).

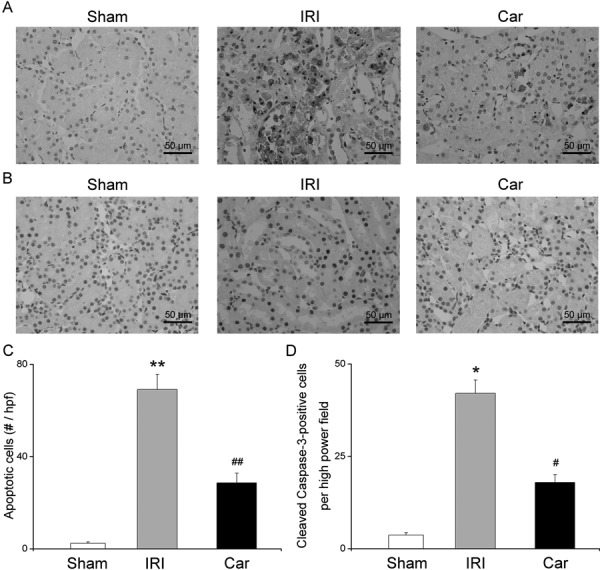

Effect of carnosol on renal IRI-induced tubular apoptosis

To evaluate the effect of carnosol on renal IRI-induced tubular apoptosis, we performed a TUNEL assay. Our data showed that the kidneys of rats in the IRI group exhibited a significant increase in the number of TUNEL-positive cells compared with those of rats in the sham group (P<0.01). On the other hand, few TUNEL-positive tubular cells were found in the kidneys of rats pretreated with carnosol (P<0.01, Figs. 5A and C).

Fig. 5.

The effect of carnosol pretreatment on apoptotic renal tubular death. (A) Photos of TUNEL staining of kidney tissue sections from rats in the sham group, IRI group, and Car group (magnification: ×400). (B) Photos of immunohistochemical staining of cleaved caspase-3 in rats from the sham group, IRI group, and Car group (magnification: ×400). (C) The quantitative evaluation of apoptotic tubular cells. (D) The quantitative evaluation of cleaved caspase-3 positive cells. Bars represent means ± SE; N=10 rats per group. * P<0.05 vs. the sham group; ** P<0.01 vs. the sham group; # P<0.05 vs. the IRI group; ## P<0.01 vs. the IRI group.

Caspase-3 has been reported to be cleaved and activated during apoptosis [29]. To confirm the role of carnosol in inhibiting apoptosis during renal IRI, we examined renal cleaved caspase-3 expression with an immunohistochemical assay. As shown in Fig. 5B, the number of cells stained positively for cleaved caspase-3 was markedly increased in the kidneys of rats in the IRI group, whereas carnosol pretreatment significantly reduced the number of cells stained positively for cleaved caspase-3 (P<0.05, Fig. 5D).

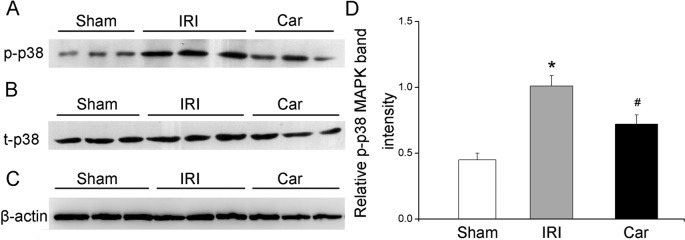

Effect of carnosol on renal IRI-induced p38 MAPK activation

As shown in Fig. 6, the expression of renal phosphorylated p38 MAPK, which is the active form of p38 MAPK, significantly increased in rats in the IRI group compared with that in rats in the sham group (P<0.05). On the other hand, carnosol pretreatment markedly reduced phosphorylated p38 MAPK expression in kidney tissues (P<0.05).

Fig. 6.

The effect of carnosol pretreatment on p38 MAPK activation. (A) Immunoblots of phosphorylated p38 (p-p38) MAPK in kidney tissues. (B) Immunoblots of total p38 (t-p38) MAPK in kidney tissues. (C) Immunoblots of β-actin. (D) Densitometric data of p-p38 MAPK (relative to t-p38 MAPK). Bars represent means ± SE; N=10 rats per group. * P<0.05 vs. the sham group; # P<0.05 vs. the IRI group.

Discussion

Carnosol is a phenolic diterpene extracted from several natural sources, including rosemary. Previous studies have shown that carnosol possesses anticancer activity, and could be used as a therapeutic agent in patients with various cancers including prostate, colon, and breast cancer [10, 11, 24]. In addition, carnosol possesses anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic action and significantly reduces free radical formation in the mammalian body [18, 25, 31, 33]. Recently, a report has demonstrated that carnosol improved hepatic damage induced by intestinal IRI by reducing inflammatory mediators and free radicals [30]. Tian et al. [27] also reported that carnosol markedly attenuated intestinal IRI-induced lung injury by inhibiting inflammatory responses in lung tissues. In this study, we examined the potential effect of carnosol on renal IRI. Our data demonstrated that pretreatment with a single dose of carnosol significantly improved IRI-induced renal tubular damage, which was reflected by improved renal function and histologic features. Previous studies have shown that renal IRI is responsible for the high morbidity and mortality of patients with AKI in both urology and nephrology departments [15, 28]. Based on the fact that no effective therapeutic agent has been available for patients with AKI until recently, we believe that the results of this study are promising, as a single dose of carnosol pretreatment protected kidneys from renal IRI, by significantly suppressing renal inflammation and tubular apoptotic death.

Inflammation, which is considered an important factor in the initiation and maintenance of IRI, is usually characterized by several processes, such as inflammatory cell infiltration, inflammatory cytokine activation, and adhesion molecule overexpression [13, 23]. In addition, inflammation has been reported to influence apoptosis through diverse signaling pathways during IRI [5, 13]. Therefore, the inhibition of inflammation is considered an effective intervention to improve renal IRI. Previous studies have demonstrated that carnosol significantly reduced inflammatory responses in vitro and in vivo [21, 27, 30]. Consistent with the results of those studies, our data showed that carnosol pretreatment markedly reduced renal MPO, which is widely used as a marker of inflammatory cell infiltration. Moreover, carnosol significantly reduced the number of ED-1-positive cells in kidney tissues, which were mainly macrophages and monocytes. Inflammatory cell infiltration plays a crucial role in the development of inflammation by producing cytokines, reactive oxygen species, and proteases. TNF-α and IL-1β are known as the most important pro-inflammatory cytokines, which may cause tissue damage directly and lead to the overexpression of other inflammatory mediators [5, 26]. Our data showed that the expression of TNF-α and IL-1β in kidney tissues was also reduced by carnosol. Reports have shown that depletion of inflammatory cell infiltration improved IRI-induced renal damage [12, 26]. Therefore, the inhibition of inflammatory cell infiltration may be partly linked to the anti-inflammatory action of carnosol during renal IRI.

Previous studies have reported that carnosol significantly suppressed cell apoptosis [14, 33]. Our data showed that carnosol markedly reduced the expression of renal TNF-α, which has been demonstrated to play a key role in the initiation of apoptosis [5, 6]. Therefore, we investigated the effect of carnosol on tubular apoptotic death during renal IRI. In our study, we observed severe tubular cell apoptosis, which was reflected by the widespread distribution of TUNEL-positive cells, in the kidneys of rats in the IRI group 24 h after reperfusion. In contrast, carnosol pretreatment significantly reduced the number of TUNEL-positive cells in the kidneys. Apoptosis is a crucial factor in the whole process of reperfusion. Reports have shown that apoptosis is one of the most important mechanisms of renal IRI [4, 6]. Therefore, the renoprotective action of carnosol may be partly related to its inhibition of tubular apoptotic death. To further investigate the mechanism of the anti-apoptotic effect of carnosol, we examined caspase-3 activation in kidney tissues using a special antibody which could detect the activated caspase-3, i.e., the cleaved caspase-3. Caspase-3 is usually activated during IRI and contributes to the whole process of apoptosis induced by IRI [29]. Alternatively, inhibition of caspase-3 activation significantly attenuates cell apoptosis [2, 13]. Our data showed that the kidneys of rats in the IRI group exhibited significantly higher expression of cleaved caspase-3, whereas carnosol pretreatment markedly attenuated the increase. This result is consistent with a previous study reporting that carnosol treatment markedly reduced caspase-3 activation in neuronal cells [14].

The p38 MAPK signaling pathway has been reported to play an important role in the initiation and maintenance of IRI. Since the p38 MAPK pathway contributes to both inflammation and apoptosis, it is obvious that p38 MAPK activation aggravates renal IRI [5, 6, 19]. On the other hand, downregulation of activated p38 MAPK (the phosphorylated p38) leads to the attenuation of renal IRI [7]. Previous studies have demonstrated that carnosol inhibited p38 MAPK activation in mouse melanoma cells and macrophages [9, 18]. Consistent with these results, our data showed that renal IRI caused a significant increase in the phosphorylated p38 in kidney tissues, whereas carnosol pretreatment markedly attenuated the increase. This result may be related to the anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effect of carnosol, although the precise mechanisms need further investigations.

In summary, our data demonstrated that a single dose of carnosol before renal ischemia significantly attenuated renal damage by improving inflammatory cell infiltration, apoptotic tubular cell death, and p38 MAPK activation in kidney tissues. Although the precise mechanisms and dose limit of carnosol need to be determined in future research, carnosol may be worth developing as a potential therapeutic agent for patients with AKI.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. LY16H280001) and the Department of Science and Technology Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. 2016C33G2010162).

References

- 1.Andreucci M., Faga T., Pisani A., Sabbatini M., Michael A.2014. Acute kidney injury by radiographic contrast media: pathogenesis and prevention. BioMed Res. Int. 2014: 362725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashkenazi A., Dixit V.M.1998. Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science 281: 1305–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellomo R., Kellum J.A., Ronco C.2012. Acute kidney injury. Lancet 380: 756–766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61454-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonventre J.V., Yang L.2011. Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. J. Clin. Invest. 121: 4210–4221. doi: 10.1172/JCI45161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daemen M.A., van ’t Veer C., Denecker G., Heemskerk V.H., Wolfs T.G., Clauss M., Vandenabeele P., Buurman W.A.1999. Inhibition of apoptosis induced by ischemia-reperfusion prevents inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 104: 541–549. doi: 10.1172/JCI6974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devarajan P.2006. Update on mechanisms of ischemic acute kidney injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17: 1503–1520. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doucet C., Milin S., Favreau F., Desurmont T., Manguy E., Hébrard W., Yamamoto Y., Mauco G., Eugene M., Papadopoulos V., Hauet T., Goujon J.M.2008. A p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor protects against renal damage in a non-heart-beating donor model. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 295: F179–F191. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00252.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng L., Ke N., Cheng F., Guo Y., Li S., Li Q., Li Y.2011. The protective mechanism of ligustrazine against renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Surg. Res. 166: 298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang S.C., Ho C.T., Lin-Shiau S.Y., Lin J.K.2005. Carnosol inhibits the invasion of B16/F10 mouse melanoma cells by suppressing metalloproteinase-9 through down-regulating nuclear factor-kappa B and c-Jun. Biochem. Pharmacol. 69: 221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson J.J.2011. Carnosol: a promising anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory agent. Cancer Lett. 305: 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson J.J., Syed D.N., Heren C.R., Suh Y., Adhami V.M., Mukhtar H.2008. Carnosol, a dietary diterpene, displays growth inhibitory effects in human prostate cancer PC3 cells leading to G2-phase cell cycle arrest and targets the 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway. Pharm. Res. 25: 2125–2134. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9552-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jo S.K., Sung S.A., Cho W.Y., Go K.J., Kim H.K.2006. Macrophages contribute to the initiation of ischaemic acute renal failure in rats. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 21: 1231–1239. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfk047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanagasundaram N.S.2015. Pathophysiology of ischaemic acute kidney injury. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 52: 193–205. doi: 10.1177/0004563214556820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S.J., Kim J.S., Cho H.S., Lee H.J., Kim S.Y., Kim S., Lee S.Y., Chun H.S.2006. Carnosol, a component of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) protects nigral dopaminergic neuronal cells. Neuroreport 17: 1729–1733. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000239951.14954.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lameire N.H., Bagga A., Cruz D., De Maeseneer J., Endre Z., Kellum J.A., Liu K.D., Mehta R.L., Pannu N., Van Biesen W., Vanholder R.2013. Acute kidney injury: an increasing global concern. Lancet 382: 170–179. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60647-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Letavernier E., Perez J., Joye E., Bellocq A., Fouqueray B., Haymann J.P., Heudes D., Wahli W., Desvergne B., Baud L.2005. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta/delta exerts a strong protection from ischemic acute renal failure. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16: 2395–2402. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu F., Ni W., Zhang J., Wang G., Li F., Ren W.2017. Administration of Curcumin Protects Kidney Tubules Against Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury (RIRI) by Modulating Nitric Oxide (NO) Signaling Pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 44: 401–411. doi: 10.1159/000484920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo A.H., Liang Y.C., Lin-Shiau S.Y., Ho C.T., Lin J.K.2002. Carnosol, an antioxidant in rosemary, suppresses inducible nitric oxide synthase through down-regulating nuclear factor-kappaB in mouse macrophages. Carcinogenesis 23: 983–991. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.6.983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo F., Shi J., Shi Q., Xu X., Xia Y., He X.2016. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases and Hypoxic/Ischemic Nephropathy. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 39: 1051–1067. doi: 10.1159/000447812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma D., Lim T., Xu J., Tang H., Wan Y., Zhao H., Hossain M., Maxwell P.H., Maze M.2009. Xenon preconditioning protects against renal ischemic-reperfusion injury via HIF-1alpha activation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20: 713–720. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poeckel D., Greiner C., Verhoff M., Rau O., Tausch L., Hörnig C., Steinhilber D., Schubert-Zsilavecz M., Werz O.2008. Carnosic acid and carnosol potently inhibit human 5-lipoxygenase and suppress pro-inflammatory responses of stimulated human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 76: 91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrier R.W., Wang W., Poole B., Mitra A.2004. Acute renal failure: definitions, diagnosis, pathogenesis, and therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 114: 5–14. doi: 10.1172/JCI200422353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharfuddin A.A., Molitoris B.A.2011. Pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 7: 189–200. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singletary K., MacDonald C., Wallig M.1996. Inhibition by rosemary and carnosol of 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA)-induced rat mammary tumorigenesis and in vivo DMBA-DNA adduct formation. Cancer Lett. 104: 43–48. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(96)04227-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singletary K.W.1996. Rosemary extract and carnosol stimulate rat liver glutathione-S-transferase and quinone reductase activities. Cancer Lett. 100: 139–144. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)04082-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takada M., Nadeau K.C., Shaw G.D., Marquette K.A., Tilney N.L.1997. The cytokine-adhesion molecule cascade in ischemia/reperfusion injury of the rat kidney. Inhibition by a soluble P-selectin ligand. J. Clin. Invest. 99: 2682–2690. doi: 10.1172/JCI119457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian X.F., Yao J.H., Zhang X.S., Zheng S.S., Guo X.H., Wang L.M., Wang Z.Z., Liu K.X.2010. Protective effect of carnosol on lung injury induced by intestinal ischemia/reperfusion. Surg. Today 40: 858–865. doi: 10.1007/s00595-009-4170-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uchino S., Kellum J.A., Bellomo R., Doig G.S., Morimatsu H., Morgera S., Schetz M., Tan I., Bouman C., Macedo E., Gibney N., Tolwani A., Ronco C., Beginning and Ending Supportive Therapy for the Kidney (BEST Kidney) Investigators2005. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA 294: 813–818. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.7.813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang B., Jain S., Ashra S.Y., Furness P.N., Nicholson M.L.2006. Apoptosis and caspase-3 in long-term renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats and divergent effects of immunosuppressants. Transplantation 81: 1442–1450. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000209412.77312.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yao J.H., Zhang X.S., Zheng S.S., Li Y.H., Wang L.M., Wang Z.Z., Chu L., Hu X.W., Liu K.X., Tian X.F.2009. Prophylaxis with carnosol attenuates liver injury induced by intestinal ischemia/reperfusion. World J. Gastroenterol. 15: 3240–3245. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng H.H., Tu P.F., Zhou K., Wang H., Wang B.H., Lu J.F.2001. Antioxidant properties of phenolic diterpenes from Rosmarinus officinalis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 22: 1094–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng Y., Lu M., Ma L., Zhang S., Qiu M., Wang Y.2013. Osthole ameliorates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. J. Surg. Res. 183: 347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zunino S.J., Storms D.H.2009. Carnosol delays chemotherapy-induced DNA fragmentation and morphological changes associated with apoptosis in leukemic cells. Nutr. Cancer 61: 94–102. doi: 10.1080/01635580802357360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]