Abstract

A variety of factors influence parent responses to pain behaviors they observe in their adolescents with chronic pain. Certain parental responses to pain, such as attention or overprotection, can adversely impact adolescent adaptive functioning and correspond to poor clinical outcomes.

Objectives:

It was hypothesized that the relationship between adolescent pain behaviors and functional disability was mediated by maladaptive parenting (protective, monitoring, solicitousness) responses.

Methods:

Participants were 303 adolescents and their mothers presenting to a pain clinic. Adolescents completed measures of functional disability and pain intensity; mothers completed measures assessing adolescent pain behaviors, their own catastrophizing about their adolescent’s pain, and responses to pain. A path model tested the direct and indirect associations between pain behaviors and disability via three parenting responses, controlling for average pain intensity and parent pain catastrophizing.

Results:

Greater pain behavior was associated with increased protective responses (α path, p < .001); greater protective behavior was associated with increased disability (β path, p = .002). Including parenting responses in the model, the path between pain behaviors and disability remained significant (c’ path, p < .001). The indirect path between pain behaviors and disability via parenting responses was significant for protective responses (p < .02), controlling for pain intensity and parent pain catastrophizing. The indirect effect of protective responses explained 18% of the variance between pain behaviors and disability.

Discussion:

Observing adolescent pain behaviors may prompt parents to engage in increased protective behavior which negatively impacts adolescents’ functioning, even after controlling for the effects of parental pain catastrophizing.

Keywords: pain behaviors, disability, parenting responses, pediatric pain, adolescents

INTRODUCTION

The familial context is crucial to understanding the social and communicative aspect of the pain experience in adolescents. A number of parent and family factors have been associated with pain-related disability in youth, including the family environment, parent-child interactions, and parenting behaviors [1]. On a daily basis, parents observe their adolescent’s experience of pain, interpret their adolescent’s behavior when they are in pain, experience emotional reactions to this information, and make decisions about how to respond to these pain expressions. Parental underestimation of pain may lead to dismissive and minimizing responses, while overestimation of pain may contribute to parents engaging in excessive solicitous and protective behaviors that may then impair the adolescent’s independent functioning. Thus, parental behaviors are a critically important factor in shaping the adolescent’s pain experience and determining how the adolescent copes with and functions in daily life.

Within the pediatric pain literature, specific parent behaviors (e.g., criticism, reassurance) have been associated with greater child-reported pain intensity and disability [2]. While an overly protective parent response has been a primary focus of past studies [3–5], research suggests that poor outcomes are likely a function of both the adolescent’s observation of a distressed parent and reception of overly protective gestures from him/her [6]. The adverse impact of several other parental behaviors (e.g., overly solicitous behaviors, parent monitoring) has also been highlighted [5, 7, 8]. Of those, parent monitoring, previously considered a relatively adaptive parenting response, may not be as benign as previously believed [9, 10], particularly for an anxious, vigilant child to whom it might signal parent distress [11]. Overly solicitous behaviors, such as providing special treats and extra care, are thought to reinforce pain behaviors if provided in response to pain-related impairment at the expense of adaptive, independent coping, particularly for anxious or depressed children [12]. These behaviors have traditionally been measured using the Adult Responses to Children’s Symptoms (ARCS), a parent self-report of responses to children’s chronic pain [5, 13]. Developmentally sensitive subscales for adolescents were identified and include five domains of parenting behaviors - protect, solicitous, monitor, minimize and distract [14, 15]. Continuing to understand the interpersonal factors influencing parenting behaviors remains an important clinical and empirical task. The parental empathy model has provided one framework for conceptualizing the role of these factors.

In the parental empathy model for pediatric chronic pain [16], top-down (e.g., parental catastrophizing) and bottom-up (e.g., parent-observed pain behaviors) processes have been proposed to influence a parent’s appreciation of, distress about, and behavioral response to their adolescent’s pain. A key “bottom up” process is the parent observation of their adolescent’s pain behaviors. Pain behaviors are a means of communicating about the pain experience and have been highlighted as an important aspect of the biopsychosocial conceptualization of pain [17, 18]. Pain behaviors take many forms including verbal (i.e., complaining), nonverbal (i.e., sighing), facial (e.g., wincing) and physical gestures (i.e., limping). Measurement of pain behaviors have included complex observational systems (e.g., [19, 20]) and objective questionnaires [21, 22], including the recently developed PROMIS pain behaviors scale [23]. Parent-reported adolescent pain behaviors have been associated with significantly greater adolescent-reported functional disability, pain catastrophizing, depressive symptoms, and poorer quality of life [24].

According to the parental empathy model, “top down” processes may also affect a parent’s interpretation of their child’s pain behaviors. Intrapersonal factors such as parental pain history, past experiences, worries about pain, and pain beliefs can contribute to their responses [16]. Specifically, parent pain catastrophizing has an important and negative impact on both parent well-being and child functioning [25–27]. The relationships among these processes and behaviors are likely nuanced, complex and dynamic. For example, results suggest that parent pain catastrophizing partially mediates the association between parent-reported child pain behavior and protective responses [4], such that greater observed pain behaviors were associated with more protective responses in the context of greater parental catastrophizing. While this study incorporated similar variables in mediational analyses, it investigated only protective responses, used an adult-derived pain behavior questionnaire, and focused solely on youth with IBD. Connelly et al. [8] found that child-reported pain intensity and interference were linked to greater subsequent use of protective and monitoring parenting behaviors in children with arthritis, which in turn led to increased child disability. However, this study did not assess pain behaviors.

Thus far, studies in the pediatric pain literature have included only some aspects representing these top-down and bottom-up processes of parent interpretation of their child’s pain, and have primarily focused on the relationship between parental responses, parental catastrophizing, and child disability. There is a gap in knowledge about parent observation of their child’s pain behaviors – which is a critically important factor in the initial process of knowing and responding to a child’s pain. This study takes the next logical step to replicate findings regarding the relationship between parenting responses and functional disability, while expanding upon prior literature by directly including pain behaviors in the model, and controlling for other parent factors known to adversely impact youth outcomes, such as parent pain catastrophizing. Finally, investigating parenting behaviors in the context of parent-adolescent relationships is particularly salient given the conflict and stress that can emerge during the developmental period of adolescence [28].

This current study examined whether maladaptive parenting responses (protectiveness, solicitiousness, and monitoring) would mediate the relationship between parent-observed adolescent pain behaviors and adolescent-reported functional disability. We hypothesized that each of these parenting responses would mediate this relationship and be associated with greater levels of functional impairment while controlling for parental catastrophizing about their adolescent’s pain and pain intensity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Participants were 303 adolescents and their accompanying mother who presented to an interdisciplinary pediatric pain management clinic between July 2010 and January 2016. Patients were eligible for this study if they 1) were between the ages of 12 and 18; 2) presented to the pain clinic with pain lasting greater than or equal to 3 months; 3) had no significant developmental delays or impairments; 4) could read and understand written English and 5) attended the clinic appointment with an adult caregiver. Because caregivers were primarily mothers, and parenting responses to pain have varied between males and females [29], the sample was restricted to only maternal caregivers. The majority of patients were referred to the pain clinic from other pediatric subspecialty clinics such as rheumatology, gastroenterology, and orthopedics.

Procedures

This study was part of a broader investigation of the psychosocial functioning and characteristics of children and adolescents with chronic pain. Portions of this dataset have been used in other published studies [24, 26], the aims of which were different from this study. Families were introduced to the study at their first visit to the Pain Management Clinic by the psychologist or an advanced practice nurse. Written consent was obtained from the parent and child if the family was interested in participating. No compensation was provided. The study was approved by the hospital’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Mothers completed measures of demographics, their perception of their adolescent’s pain behaviors, and reported on their parenting responses to pain. Adolescents completed measures of pain intensity and functional disability.

Demographic and Clinical Information

Parents provided basic demographic information, including their adolescent’s sex, age, race, and ethnicity. Information about pain duration and pain location was obtained from the family and/or the pain physician’s report in the electronic medical record.

Pain Intensity

Pain intensity was rated by adolescents using a numeric visual analogue scale (VAS) [30], a 10 cm line divided into 11 numbered points ranging from 0 to 10 with the anchors “no pain” and “worst imaginable pain”. Patients reported highest, lowest, and average pain intensity over the last two weeks. For statistical analyses, average pain intensity was used. VAS scales are validated for children 8 years old and older [31].

Functional Disability

The Functional Disability Inventory (FDI) is a 15-item, self-report measure assessing the difficulty performing daily activities due to pain [32]. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0, “no trouble,” to 4, “impossible.” The total score is calculated by summing the items and ranges from 0–60 with a higher score indicating greater pain-related disability. This measure is well validated in ages 8–17 across many pain conditions, has high internal consistency, high test-retest reliability, and good predictive validity [32–34]. FDI scores can be categorized as no/minimal (0–12); moderate (13–29); and severe (30+) disability [33].

Adolescent Pain Behaviors

The Adolescent Pain Behavior Questionnaire (APBQ) is a 23-item, parent-report measure to assess parent perceptions of an adolescent’s expressions of pain [24]. Parents are asked to report how often in the last 4 weeks they have observed verbal and nonverbal pain behaviors using a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 0, “never,” to 5, “almost always.” A total score is calculated by summing the items and ranges from 0 to 115. Higher scores indicate greater parent-reported pain behaviors. This measure has high internal consistency, is reliable, and is validated for adolescents 11 years and older [24].

Adult Response to Children’s Symptoms

The Adult Response to Children’s Symptoms (ARCS) is a 29-item, parent report measure designed to assess the frequency of specific parental behaviors to their child’s pain [13]. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert, ranging from 0, “never” to 4, “always.” Noel et al. [14] re-analyzed the measure through factor analysis, and for adolescents, a five factor model was identified with the following subscales: Minimize, Monitor, Protect, Solicitousness, and Distract. For each subscale, a total is calculated by averaging the responses for the items that correspond to that subscale. This measure is validated for youth from 7–18 years old [13, 14]. In this study, descriptive data was provided for all subscales, but only the Protect, Monitor, and Solicitousness subscales were included in the analyses.

Pain Catastrophizing Scale (Parent Report)

This 13-item questionnaire is adapted from the Pain Catastrophizing Scale, a measure developed to assess coping styles among adult chronic pain patients [35]. A child-report version of the PCS (PCS-C) was designed for youth with pediatric chronic pain [36]. The parent version of the PCS (PCS-P) is adapted for caregivers to evaluate the degree to which they worry and catastrophize about their child’s pain [25]. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale [ranging from “Not at all” (0) to “Extremely” (4)] and are summed to create a total score, which higher scores indicating increased worry. There is good evidence for construct and criterion validity [25].

Statistical Analyses

All data were entered and analyzed using SPSS Version 22 [37]. Descriptive data were computed for demographic information, including age, sex, race, and ethnicity. Descriptive analyses were also conducted for adolescent pain characteristics (intensity, duration, and location), as well as for functional disability, adolescent pain behaviors, parent pain catastrophizing, and parent responses to pain symptoms. Overall, less than 3% of items within the dataset were incomplete.

We employed a path model to test which parent-reported pain behaviors were linked directly to adolescent functional disability and also indirectly via self-reported parenting responses (protective, solicitous, and monitoring). This is consistent with our hypothesis that observing greater pain behaviors would lead to parenting behaviors that would in turn lead to greater functional disability while controlling for the parent’s level of catastrophizing and the adolescent’s average pain intensity. Mplus software (Version 8) was used to test these hypothesized paths [38]. Missing data for these analyses was handled via maximum likelihood estimation with auxiliary correlates under the missing at random assumption in three steps. In the first step, total scores for functional disability, parenting response, and adolescent pain behaviors were computed only for participants with no missing item data. In the second step, the functional disability, parenting response, and adolescent pain behaviors items most highly correlated with their respective total scores were identified [39]. In the third step, all analysis variable total scores, items (4 for the FDI, 2 for the APBQ, & 5 for the ARCS) identified from the second step, as well as participant age and sex, were included as auxiliary correlates of missing data (c.f., Graham, 2003 [40]) in all mediation analyses.

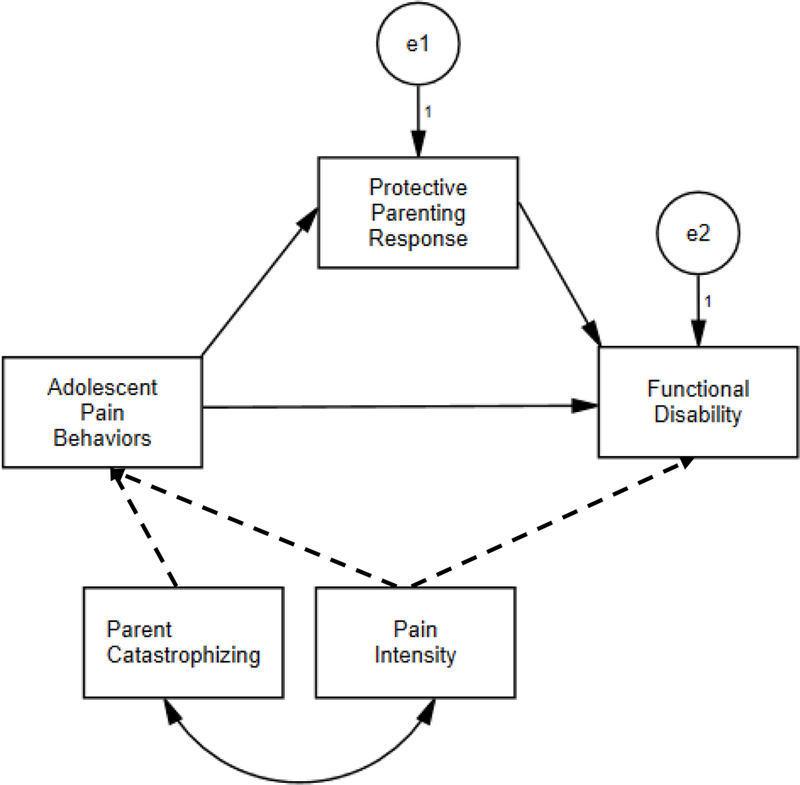

The following empirically supported fit indices were used to determine optimal model fit: model chi-square (χ2) values closer to zero with p < 0.05, RMSEA values < 0.06, SRMR values < 0.08, CFI values > 0.95. [38, 41]. We examined the path models’ fit using the above indices and the significance of each path in the complete model (α path = pain behaviors (APBQ) → parenting response (ARCS protect, solicitous, monitor), β path = parenting response (ARCS protect, solicitous, monitor) → functional disability (FDI), c’ path = pain behavior (ABPQ) → functional disability FDI) (see Figure 1). We controlled for the influence of average pain intensity on functional disability (FDI) and pain behaviors (APBQ). Additionally, we controlled for the effect of parent catastrophizing about their child’s pain (PCS-P) on parental perceptions of pain behaviors (ABPQ).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized mediation model for pain behaviors, parental responses to pain, and functional disability, controlling for pain intensity and parent pain catastrophizing.

To reduce the probability of Type I error in the path model, we used 5000 bootstrap draws for all mediation model analyses to generate a sampling distribution of αβ values centered at the value of αβ in the sample data [42]. A 95% confidence interval (CI) for the indirect (αβ) pathway that does not include zero represents significant mediation.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Participants of this study were 303 adolescents and their mothers. Adolescent mean age was 15.1 years (SD = 1.7). The majority of adolescents were female (N = 241, 79.5%) and Caucasian (N = 255, 84.2%). Parent participants were exclusively mothers.

Pain Characteristics

Participants reported moderate average pain intensity (M = 5.8, SD = 1.9), with lowest pain intensity reported as 3.4 (SD = 2.3) and highest pain intensity as 8.2 (SD = 1.8). Approximately 65.3% (N = 198) of adolescents had a pain duration longer than one year and 85.5% (N = 259) experienced daily pain. Most common pain complaints were abdominal (N = 87, 28.7%) and back pain (N = 82, 27.1%). (see Tables 1 & 2). Approximately half (45.2%) of participants reported having an immediate family member with chronic pain.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Age (M, SD) | 15.1 (1.7) |

| Sex (N, %) | |

| Female | 241 (79.5) |

| Male | 62 (20.5) |

| Race (N, %) | |

| Caucasian | 255 (84.2) |

| Black or African American | 14 (4.6) |

| Asian | 3 (1.0) |

| Biracial | 9 (3.0) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 4 (1.3) |

| Other | 3 (1.0) |

Table 2.

Pain Characteristics

| Pain Location (N, %) | |

| Abdominal or Flank | 87 (28.7) |

| Back Pain | 82 (27.1) |

| Headache or Migraine | 9 (3.0) |

| Leg or Limb Pain | 13 (4.3) |

| Fibromyalgia | 42 (13.9) |

| Joint Pain | 33 (10.9) |

| Other | 35 (11.6) |

| Pain Duration (N, %) | |

| 3–6 Months | 59 (19.5) |

| 7–11 Months | 46 (15.2) |

| 1–3 Years | 124 (40.9) |

| More than 3 years | 74 (24.4) |

Outcome Measures

Adolescents reported moderate levels of pain-related disability on the FDI (M = 23.4, SD = 11.2) [33]. Average APBQ total score was 51.8 (SD = 20.9), with considerable variability in scores (range 3 to 114). On the ARCS, parents described a variety of response to their adolescents’ pain with monitor (M = 12.6, SD = 2.8), protect (M = 7.9, SD = 4.3) and distract (M = 7.6, SD = 2.3) behaviors occurring most frequently, and minimizing endorsed least often (see Table 3). These values are consistent with those reported by Noel et al. [14] in their adolescent sample. Parents reported moderate levels of pain catastrophizing (M = 27.5, SD = 10.8).

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics

| M | SD | N | α | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Disability Inventory | 23.5 | 11.2 | 288 | .88 | 0–60 |

| Adolescent Pain Behavior Questionnaire | 51.8 | 20.9 | 246 | .93 | 0–115 |

| Visual Analog Scale | 0–10 | ||||

| Average Pain Intensity | 5.8 | 1.9 | 295 | ||

| Highest Pain Intensity | 8.2 | 1.8 | 296 | ||

| Lowest Pain Intensity | 3.4 | 2.3 | 296 | ||

| Adult Response to Children’s Symptoms | |||||

| Protect | 7.9 | 4.3 | 272 | .74 | 0–23 |

| Monitor | 12.6 | 2.8 | 291 | .77 | 0–11 |

| Minimize | 2.7 | 2.5 | 291 | .70 | 0–13 |

| Distract | 7.6 | 2.3 | 292 | .68 | 0–12 |

| Solicitousness | 4.5 | 2.4 | 291 | .62 | 0–11 |

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale (Parent) | 27.5 | 10.8 | 286 | .93 | 0–52 |

Correlations

Greater adolescent-reported disability was associated with increased parent-reported pain behaviors, higher average pain intensity and use of protecting, solicitous, monitoring, and distracting parenting behaviors in response to pain. Functional disability was not related to a minimizing parent response and showed a small but significant relationship to parent pain catastrophizing. Higher pain intensity was significantly correlated with greater solicitous and monitoring parenting behaviors. Greater parental catastrophizing about their adolescent’s pain and increased parent-reported pain behaviors were associated with significantly greater use of all parenting techniques (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlations between Outcome Variables

| Protect | Monitor | Minimize | Distract | Solicit | VAS | APBQ | FDI |

PCS-P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protect | - | .36** | .22** | .28** | .58** | .12 | .42** | .30** | .29** |

| Monitor | - | −.08 | .41** | .36** | .12* | .31** | .12* | .38** | |

| Minimize | - | .12* | .13* | .04 | .31** | .04 | .20** | ||

| Distract | - | .31** | .10 | .36** | .17** | .31** | |||

| Solicit | - | .21** | .39** | .24** | .37** | ||||

| VAS | - | .32** | .41** | .17** | |||||

| APBQ | - | .40** | .36** | ||||||

| FDI | - | .16* | |||||||

| PCS-P | - |

Note.

Significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

Significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

VAS (Visual Analog Scale)

APBQ (Adolescent Pain Behavior Questionnaire)

FDI (Functional Disability Inventory)

PCS-P (Pain Catastrophizing Scale- Parent)

Path Modeling

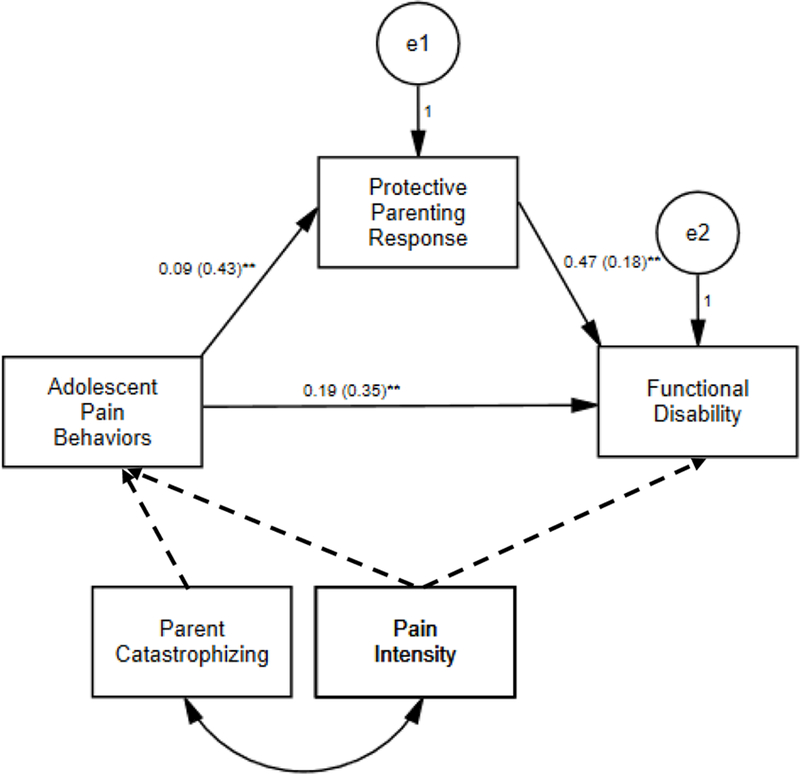

We tested a path model of the direct and indirect associations among observed pain behaviors and adolescent functional disability via parenting responses while controlling for the influence of average pain intensity on functional disability and pain behaviors and the effect of parental pain catastrophizing on parent-reported pain behaviors. The following indices for the fit of the mediation model to the sample data were observed: χ2 (1) = 91.04, p < .01; CFI = .97; RMSEA <0.001, SRMR = .09 which indicates adequate fit. Greater observed adolescent pain behaviors were associated with greater protective parenting responses (α path, APBQ → ARCS protect, b = 0.09, p < .001), and greater protective parenting was associated with increased functional disability (β path, ARCS → FDI, b = 0.47, p = .002). With the inclusion of parenting responses in the model, the c’ path between greater pain behaviors and increased functional disability remained significant (APBQ → FDI path, c’ = 0.19, p < .001), indicating a partially mediated pathway. The indirect path between pain behaviors and functional disability via parenting response was significant for protective parenting (αβ = 0.04, p < .02, 95% CI = 0.01, 0.07,) but not significant for solicitous or monitor behaviors (see Figure 2). The indirect effects of protective parenting in this model explained 18% of the variance in the association between pain behaviors and functional disability.

Figure 2.

Protective parenting responses partially mediate the relationship between parent-reported pain behaviors and functional disability, controlling for pain intensity and parent pain catastrophizing. Note: Standardized estimates in parentheses; indirect (αβ) pathway = 0.041 (95% CI: 0.013, 0.074)

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether presumed negative parenting responses to pain, namely solicitous, protective and monitoring behaviors, mediated the relationship between parent-reported pain behaviors and adolescent-reported functional disability. The models tested in this study incorporate multiple individual and parent factors thought to influence the outcomes of adolescents with chronic pain. This study focused specifically on adolescence, which is a developmental period categorized by emotional lability and more intense conflicts with parents [28] and provides additional context to the manner in which parents respond to their adolescent’s pain behaviors. All three parenting behaviors (solicitous, protective and monitoring) showed significant positive correlations with functional disability, parent pain catastrophizing and pain behaviors, with protective responses most strongly correlated with greater disability and pain behaviors in adolescents.

Protective parenting behaviors partially mediated the relationship between pain behaviors and functional disability when controlling for average pain intensity and parent pain catastrophizing. In other words, greater observed pain behaviors were associated with increased disability via increased protective parenting responses, above and beyond the adolescent’s pain or the parent’s tendency to catastrophize about their adolescent’s pain. Similar relationships were not found for solicitous or monitoring behaviors. These findings are consistent with past literature on the association between overprotectiveness and disability in pediatric chronic pain and highlight the significance of overprotective parenting even in the presence of other importance parenting factors, such as parent pain catastrophizing, which has also been shown to be associated with adolescent functional disability.

Closer inspection of the ARCS subscales may give insight why protective parenting specifically is linked to adolescent functional disability. Several of the items on the Protect subscale describe parenting behaviors that specifically restrict activity (i.e. allowing a child to stay home from school or allowing him to sleep in) in a manner that is not developmentally typical and directly contributes to impairment (i.e., allowing a child to sleep in leads to tardy or truancy issues at school). In contrast, the solicitous subscale is comprised of items such as bringing special treats or giving special privileges which are actions that may be culturally normal in many instances (i.e., it is common to bring a small gift or treat to brighten the day of someone who is sick) and may not uniformly worsen coping or deliberately restrict typical daily routines. On the 4-item Monitor scale, one item could be interpreted as a problem solving approach (i.e., asking the adolescent what they can do to help them) while the others may be viewed as less adaptive because they maintain a focus on symptoms (i.e., asking how the adolescent feels or how they are doing). Excessive parent attention to pain as categorized by these latter items on the Monitor scale may inhibit the adolescent from using independent coping behaviors (i.e., distraction). Alternatively, parent monitoring of adolescent emotional responses may be useful in some instances. A recent study suggested a subtype of pain behaviors that involves emotional disclosure of pain-related distress may prove to be adaptive and functionally different from other pain behaviors [43]. Parent monitoring that includes empathetic attention and evokes adolescent emotional disclosure may enhance emotion regulation and improve adolescent outcomes. Thus, the mixed findings in the literature for the Monitor subscale may reflect two distinct components of parent monitoring- which may be either adaptive or maladaptive in relation to adolescent functioning.

Parental vigilance and ability to recognize and respond to pain behaviors may in turn vary based upon other intrapersonal characteristics. Parents with higher pain catastrophizing showed a greater tendency to monitor their adolescent’s behaviors, possibly making them more accurate in noticing pain behaviors, or in turn, over-interpreting behaviors as being induced by pain. Our results showed that greater observation of pain behaviors and greater parent pain catastrophizing were significantly associated with using all parenting responses; thus, witnessing pain behaviors likely demands some kind of response from parents. Notably, protective behavior remained a partial mediator even after controlling for the effects of parent pain catastrophizing on parent-reported pain behaviors. Receiving restrictive and limiting forms of parenting may also inadvertently maintain attention to pain, reinforcing the adolescent’s perception of disability, need for caution and behavioral restriction.

Future research should examine the transactional nature of parent-adolescent dyads in terms of how pain behaviors, parent responses to those behaviors and adolescent disability vary over time. A recent study using smartphone technology and ecological data collection has begun to capture this dynamic relationship [8]. Among youth with juvenile arthritis, increased pain intensity and interference were documented following parental use of protective responses. However, parents, in turn, relied on increased monitoring and protective response after children reported more than usual pain intensity and interference, likely manifested in part by increased behavioral cues and expressions of pain [8]. Thus, results of our study complement these findings

This study should be interpreted based on the following limitations. The cross-sectional nature limits the ability to identify causation. Additionally, parenting responses and adolescent pain behaviors are likely not fixed, but fluctuate daily based on pain intensity, activity level, mood and context. Collection of data at multiple time points might afford a greater ability to determine if changes in functional disability coincide with changes in parenting strategies, which change occurs first (parenting style or adolescent impairment), and how pain behaviors vary in relation to these two factors. Consistent with other pediatric studies [44, 45], the sample was comprised of mostly Caucasian, female adolescents and results may fail to generalize beyond this subset of participants. Parent-report measures were completed by mothers, making it difficult to ascertain if the same results would be replicated for other caregivers (fathers, other primary caregiving adults). While pain behaviors were not verified by an objective coding system, they were assessed using a brief measure developed specifically for adolescents in a clinical setting experiencing chronic pain [24]. A recent study has suggested that certain pain behaviors, such as disclosure of pain-related distress, may be adaptive if used in a goal-directed manner to increase communication and processing of emotions [17]. However, the measure used in this study did not include items assessing this pain behavior, which should be investigated in the future. Finally, the internal consistency of the ARCS solicitous scale in this study was relatively low.

In clinical practice, the empathy model may be a useful frame work for helping parents identify the adolescent pain behaviors they observe and respond to. Providing explicit guidance to parents about avoiding overprotective behaviors continues to be an important parent-focused intervention. From a research perspective, recent studies have emphasized the inclusion of parenting factors in intervention studies [7, 15]. With availability of technological advances (personal devices), novel treatment approaches might include interactive coaching and prompts for parents if they identify the use of parenting responses known to worsen pain-related disability. Additionally, incorporating the nuanced assessment of pain behaviors more routinely into pediatric research is necessary. Brief, psychometrically robust tools to assess pain behaviors have been developed in the adult pain literature (i.e. PROMIS measures, [46–48]) and have just been published for pediatric use as well [23, 46], which bodes well for a more sophisticated understanding of the well-established connection between protective parenting responses and functional disability.

Acknowledgments

S. Kashikar-Zuck is supported by a National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS)/NIH Grant K24AR056687

Footnotes

There are no potential conflicts of interest for any of the authors related to the publication of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Palermo TM, Chambers CT. Parent and family factors in pediatric chronic pain and disability: An integrative approach. Pain 2005; 119(1–3): 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chambers CT, Craig KD, Bennett SM. The impact of maternal behavior on children’s pain experiences: an experimental analysis. J Pediatr Psychol 2002; 27(3): 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simons LE, Claar RL, Logan DL. Chronic pain in adolescence: parental responses, adolescent coping, and their impact on adolescent’s pain behaviors. J Pediatr Psychol 2008; 33(8): 894–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langer SL, Romano JM, Mancl L, et al. Parental Catastrophizing Partially Mediates the Association between Parent-Reported Child Pain Behavior and Parental Protective Responses. Pain Res Treat 2014; 2014: 751097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claar RL, Guite JW, Kaczynski KJ, et al. Factor structure of the Adult Responses to Children’s Symptoms: validation in children and adolescents with diverse chronic pain conditions. Clinical Journal of Pain 2010; 26(5): 410–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sieberg CB, Williams S, Simons LE. Do Parent Protective Responses Mediate the Relation Between Parent Distress and Child Functional Disability Among Children With Chronic Pain? Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2011; 36(9): 1043–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sieberg CB, Smith A, White M, et al. Changes in Maternal and Paternal Pain-Related Attitudes, Behaviors, and Perceptions across Pediatric Pain Rehabilitation Treatment: A Multilevel Modeling Approach. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connelly M, Bromberg MH, Anthony KK, et al. Use of Smartphones to Prospectively Evaluate Predictors and Outcomes of Caregiver Responses to Pain in Youth with Chronic Disease. Pain 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claar RL, Simons LE, Logan DE. Parental response to children’s pain: the moderating impact of children’s emotional distress on symptoms and disability. Pain 2008; 138(1): 172–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palermo TM, Valrie CR, Karlson CW. Family and parent influences on pediatric chronic pain: a developmental perspective. American Psychologist 2014; 69(2): 142–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham NR, Lynch-Jordan A, Barnett K, et al. Child Pain Catastrophizing Mediates The Relationship Between Parent Responses to Pain And Disability in Youth With Functional Abdominal Pain. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peterson CC, Palermo TM. Parental reinforcement of recurrent pain: the moderating impact of child depression and anxiety on functional disability. J Pediatr Psychol 2004; 29(5): 331–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Slyke DA, Walker LS. Mother’s responses to children’s pain. Clinical Journal of Pain 2006; 22(4): 387–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noel M, Palermo TM, Essner B, et al. A developmental analysis of the factorial validity of the parent-report version of the Adult Responses to Children’s Symptoms in children versus adolescents with chronic pain or pain-related chronic illness. J Pain 2015; 16(1): 31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noel M, Alberts N, Langer SL, et al. The Sensitivity to Change and Responsiveness of the Adult Responses to Children’s Symptoms in Children and Adolescents With Chronic Pain. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2016; 41(3): 350–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goubert L, Craig KD, Vervoort T, et al. Facing others in pain: the effects of empathy. Pain 2005; 118(3): 285–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadjistavropoulos T, Craig KD, Duck S, et al. A Biopsychosocial Formulation of Pain Communication. Psychol Bull 2011; 137(6): 910–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Revicki D, et al. Identifying important outcome domains for chronic pain clinical trials: an IMMPACT survey of people with pain. Pain 2008; 137(2): 276–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCahon S, Strong J, Sharry R, et al. Self-report and pain behavior among patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain 2005; 21(3): 223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keefe FJ, Smith S. The assessment of pain behavior: implications for applied psychophysiology and future research directions. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2002; 27(2): 117–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerns RD, Haythornthwaite J, Rosenberg R, et al. The Pain Behavior Check List (PBCL): factor structure and psychometric properties. J Behav Med 1991; 14(2): 155–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osman A, Barrios FX, Kopper B, et al. The pain behavior check list (PBCL): psychometric properties in a college sample. J Clin Psychol 1995; 51(6): 775–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunningham NR, Kashikar-Zuck S, Mara C, et al. Development and validation of the self-reported PROMIS pediatric pain behavior item bank and short form scale. Pain 2017; 158(7): 1323–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynch-Jordan AM, Kashikar-Zuck S, Goldschneider KR. Parent perceptions of adolescent pain expression: the adolescent pain behavior questionnaire. Pain 2010; 151(3): 834–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goubert L, Eccleston C, Vervoort T, et al. Parental catastrophizing about their child’s pain. The parent version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS-P): a preliminary validation. Pain 2006; 123(3): 254–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lynch-Jordan AM, Kashikar-Zuck S, Szabova A, et al. The interplay of parent and adolescent catastrophizing and its impact on adolescents’ pain, functioning, and pain behavior. Clin J Pain 2013; 29(8): 681–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Logan DE, Simons LE, Carpino EA. Too sick for school? Parent influences on school functioning among children with chronic pain. Pain 2012; 153(2): 437–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laursen B, Coy KC, Collins WA. Reconsidering changes in parent-child conflict across adolescence: A meta-analysis. Child Development 1998; 69(3): 817–832. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vervoort T, Huguet A, Verhoeven K, et al. Mothers’ and fathers’ responses to their child’s pain moderate the relationship between the child’s pain catastrophizing and disability. Pain 2011; 152(4): 786–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1994; 23(2): 129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGrath PJ, Walco GA, Turk DC, et al. Core outcome domains and measures for pediatric acute and chronic/recurrent pain clinical trials: PedIMMPACT recommendations. Journal of Pain 2008; 9(9): 771–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker LS, Greene JW. The functional disability inventory: measuring a neglected dimension of child health status. J Pediatr Psychol 1991; 16(1): 39–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kashikar-Zuck S, Flowers SR, Claar RL, et al. Clinical utility and validity of the Functional Disability Inventory among a multicenter sample of youth with chronic pain. Pain 2011; 152(7): 1600–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Claar RL, Walker LS. Functional assessment of pediatric pain patients: psychometric properties of the functional disability inventory. Pain 2006; 121(1–2): 77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess 1995; 7: 524–32. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crombez G, Bijttebier P, Eccleston C, et al. The child version of the pain catastrophizing scale (PCS-C): a preliminary validation. Pain 2003; 104(3): 639–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corp I, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. 2013, IBM Corp: Armonk, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kline RB, Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mazza GL, Enders CK, Ruehlman LS. Addressing Item-Level Missing Data: A Comparison of Proration and Full Information Maximum Likelihood Estimation. Multivariate Behavioral Research 2015; 50(5): 504–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Graham JW. Adding missing-data-relevant variables to FIML-based structural equation models. Struct Eqaut Model Multidiscip J 2003; 10(1): 80–100. [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behav Res 2004; 39: 99–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu L, Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Eqaut Model Multidiscip J 1999; 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cano A, Goubertt L. What’s in a Name? The Case of Emotional Disclosure of Pain-Related Distress. Journal of Pain 2017; 18(8): 881–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kashikar-Zuck S, Goldschneider KR, Powers SW, et al. Depression and functional disability in chronic pediatric pain. Clin J Pain 2001; 17(4): 341–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, et al. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain 2011; 152(12): 2729–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacobson CJ, Kashikar-Zuck S, Farrell J, et al. Qualitative Evaluation of Pediatric Pain Behavior, Quality, and Intensity Item Candidates and the PROMIS Pain Domain Framework in Children With Chronic Pain. Journal of Pain 2015; 16(12): 1243–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeWitt EM, Carle A, Barnett K, et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Promis Pediatric Item Banks in Children with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66: S109–S110. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Varni JW, Stucky BD, Thissen D, et al. PROMIS Pediatric Pain Interference Scale An Item Response Theory Analysis of the Pediatric Pain Item Bank. Journal of Pain 2010; 11(11): 1109–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]