Abstract

This qualitative study aimed to confirm and extend research on meaning making after cancer. In all, 119 adults aged 41 to 88 years (M = 65.50 years and standard deviation = 9.16 years) were interviewed 12 months after diagnosis of oral-digestive cancers. About half tried to understand why they got cancer (43%) and said that cancer changed their view of life (53%). Most (75%) reported that previous life experiences helped them cope with cancer. Cancer survivors made meanings in the areas of existential, social, and personal domains with both positive and negative content. Practitioners may wish to examine meaning making in these areas for those in distress after cancer.

Keywords: cancer, illness perception, meaning, narratives, post-traumatic growth

Introduction

For decades, clinicians and researchers have described “meaning making” after stressful experience as one mechanism of processing and coping with traumatic experience (Park, 2010; Rajandram et al., 2011). Supporting those who are searching for meaning after stressful experience and facilitating new understandings that relieve distress is a core component of meaning-centered therapy, cognitive therapies, and other psychotherapeutic interventions (Cafaro et al., 2016; Hayes et al., 2007; Van der Spek et al., 2017). In this article, we summarize meaning-making concepts and literature, present the results of a qualitative analysis of meaning making in cancer survivors, and discuss these results in the context of the literature and practitioner implications.

Distinguishing searching for meaning, making meaning, and meanings made

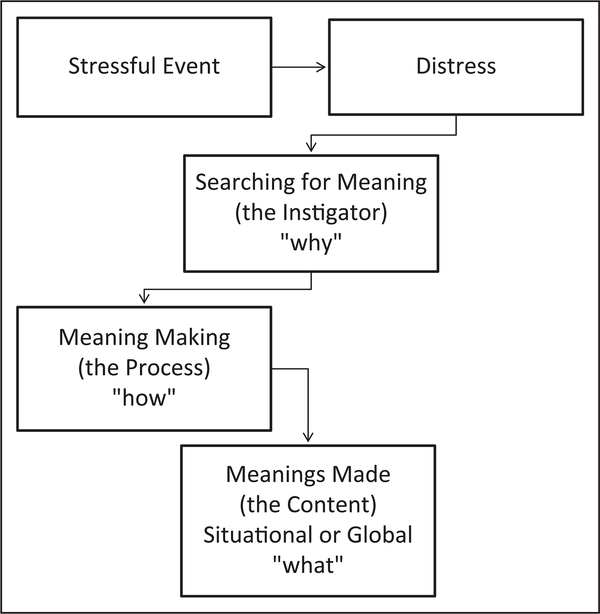

Studies of meaning making after stress may focus on different aspects of meaning making. In this article, we will use the framework presentedin Figure 1. We distinguish between (1)searching for meaning—the “why” that mayinstigate meaning-making processes (Lee,2008); (2)meaning-making processes—cognitiveand emotional processing of meanings andbeliefs—the “how” (Dondanville et al., 2016);from (3) finding meaning—the beliefs and cognitionsor “meanings made”—the “what” (Park,2010). In the following, we briefly set forththese terms as we will use them in presentingour results.

Figure 1.

Meaning-making model.

Searching for meaning.

Estimates of the prevalence of searching for meaning after stressful events vary widely from 6 to 90 percent (Park, 2010) and include searching for meaning after the experience of disasters (Aiena et al., 2016), death of a child (Lichtenthal et al., 2010), combat (Tsai et al., 2015), and cancer (Shand et al., 2015). The differences in prevalence likely relates to differences between the types and severity of stressors studied as well as variability in the measurement approach and time since the stressor. The process of searching for meaning may be brief, ongoing, or delayed (Kernan and Lepore, 2009).

Meaning-making processes.

The process of meaning making occurs as individuals try to make sense of difficult experience and, when appropriate, may be targeted in psychotherapy. Such meaning-making processes may be driven by anxiety (Groarke et al., 2016). The processing that comprises meaning making may arise out of a conflict between cognitions about the stressful experience and one’s existing cognitions about the self and the world through assimilation or accommodation (LoSavio et al., 2017). Through this, discrepancies between the appraised meaning of the stressful event and existing beliefs and goals may be resolved.

Meanings made.

Across meaning-making studies, about 53–75 percent of participants report new meanings made from stressful experience (Park, 2010). These cognitions may be specific to the situation (e.g. why did this event happen) or more global (e.g. beliefs about the self, the world, connection to others, goals, and subjective sense of meaning or purpose) or both (Park, 2010). The meanings made have been termed “stress related growth,” “post traumatic growth,” and “benefit finding”—with some distinctions in definition related to the severity of the stressor and nature of growth. Hereon in this article, we will use the term stress-related growth to refer broadly to growth- or benefit-related meaning making. Reports of perceived growth include changes in worldview, acceptance, family relations, social relations, health behaviors, personal control (Tomich and Helgeson, 2004), as well as new possibilities, spirituality, and personal strength (Tedeschi et al., 1998).

More recently, some studies have contrasted stress-related growth with stress-related “depreciation,” noting that individuals may report growth, depreciation, or both growth and depreciation (Kroemeke et al., 2017; Richardson, 2015). The co-existence of growth and depreciation points to the complexity of human responses to stress (Michelsen et al., 2017).

Meaning making after cancer

A number of studies have examined meaning making after Cancer (Shand et al., 2015). Cancer is for many a stressor and for some a traumatic stressor that can lead to psychiatric diagnoses like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Kangas et al., 2002). Rates of cancer-related PTSD range from 0 to 35 percent, most often in the range of 10 percent (Guglietti et al., 2010; Mundy et al., 2000), similar to rates of PTSD among individuals who have experienced other traumatic stressors (Carlson and Dalenberg, 2000).

The relationship between stress, distress (like PTSD) and meaning making (both processes and meanings made) is complex and debated (Shakespeare-Finch and Lurie-Beck, 2014). Generally, reports of perceived growth are correlated with more anxiety, less depression, and more positive coping (Andrykowski et al., 2017; Helgeson et al., 2006; Kolokotroni et al., 2014; Stanton et al., 2002). This may be consistent with the theory that the drive to reduce distress underlies meaning-making processes (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; ShakespeareFinch and Lurie-Beck, 2014; Shand et al., 2015), such that distress and growth can cooccur and PTSD may occur in part when individuals become “stuck” on maladaptive meanings and ruminations (Cafaro et al., 2016).

A relationship between meaning making and eventual mitigation of distress is suggested in meta-analyses that find time since trauma moderates the relationship between meaning making and depression, that is, with more time since the trauma—presumably for meaning making—there is less depression (Helgeson et al., 2006). Furthermore, this relationship could be consistent with findings that older survivors are more resilient to the stress of cancer—ostensibly having made meaning from previous life stressors (Costanzo et al., 2009), although other interpretations of this finding are possible. However, there are few longitudinal studies, so it is unclear whether meaning making is a response to distress, co-occurs with distress, or influences long-term levels of distress.

Most of the research on cancer and meaning making has been in samples of White upper socioeconomic status women who survived breast cancer (Shand et al., 2015). These studies have primarily focused on stress-related growth (Cordova et al., 2007; Helgeson et al., 2006; Tedeschi et al., 1998). In this body of research, younger cancer survivors report more growth than older survivors do (Kolokotroni et al., 2014). In addition, younger survivors may have differential meaning-making processes of growth linked to perceptions (older women) or coping strategies (younger women; Boyle et al., 2016). However, this research is cross- sectional, so it is difficult to determine how meaning-making strategies may build over time. Meaning making in survivors of other cancers and in older survivors as well as in men has been less studied (Rowland and Bellizzi, 2014).

Aims and hypotheses of this study

Given this background, we completed semi-structured interviews with a group of middle to older age survivors of oral-digestive cancer recruited from the US Veterans Healthcare System. This sample is unique from prior studies of meaning making after cancer being primarily male, middle to older age, and having non-breast cancers. Our goals were threefold: (1) to describe the prevalence of searching for meaning, (2) to describe the nature of meaningmaking processes, and (3) to describe the content of meanings made. In relation to these aims, our hypotheses were (1) some portion of our sample would report searching for meaning; however, we were uncertain of the exact portion who would report searching given the wide range in the literature; (2) that, consistent with a lifespan developmental perspective, participants would anchor their meaning-making processes with past life events; and (3) that the meanings made in this sample would represent both growth and depreciation.

Methods

Study design, setting, and data sources

Participants were identified from the tumor registries. Eligible patients had solid tumors affecting the digestive system, specifically head and neck, esophageal, gastric, or colorectal-cancers, and were excluded if they were in hospice care, had dementia, or psychotic spectrum disorder. Participants completed a semi-structured interview related to meaning making at 12 months post cancer diagnosis as part of a longitudinal cohort– observational study. Complete protocol methods including non-responder information are described elsewhere (Naik et al., 2013).

Variables, data sources, and measurement

Demographics.

Participants reported their age, gender, ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino or not), race, and level of education.

Combat-PTSD screening.

Participants completed the Primary Care PTSD Screen (Prins et al., 2003) and also stated whether they had previous mental health treatment for PTSD.

Cancer information.

Information about the cancer diagnosis, stage, and treatments was obtained from the medical record.

Meaning-making interview.

A semi-structured interview was developed through literature review, team consensus, and piloting (Appendix A). Seven close-ended items introduced different topic areas followed by open-ended items to prompt narrative responses. Open-ended responses were recorded in writing at the time of the interview and typed into the data file after the interview.

Analytical methods

Data were subjected to a thematic analysis focused on identifying content-related codes across participants with subsequent thematic grouping. For the purposes of transparency and confirmability, detailed analytic process is described further here (Meyrick, 2006).

Analytic approach.

The analytic approach was integrated in that it used both theoretic (deductive) and inductive methods. As described in the following, our initial code set was theoretic in that it was based on the literature (Braun and Clarke, 2006). In addition, an inductive approach was used to generate new codes when the data did not fit into the initial code set. We used a semantic analysis, organizing phrases and sentences into code and thematic units by their observable content. Data were analyzed with an excel data file through a recursive team process.

Researcher theoretical stance.

Consistent with the concept of reflexivity (Finlay, 2002), we acknowledge the influence of the researchers on the analysis. Three members of the research team (J.M., A.J., and R.N.-B.) are trained as geropsychologists within the US Veterans Health System where the work was conducted. As such, our data analytic approach is informed by a lifespan developmental framework, our experience providing psychotherapy to older adults adjusting to medical illnesses, and our review of the meaning-making literature. Two members of the research team (L.H. and J.G.) are trained in psychology at the undergraduate level and were employed as research assistants on the project. The other co-author (A.N.) is trained as a geriatrician and was not involved in the data analysis.

Data organization.

Transcribed data were transferred to an excel data base and reviewed to inform the coding process. Participants often provided responses relevant to early prompts in response to later prompts. Thus, each participant was assigned a row, and the full narrative was entered into the first cell on that row.

Generating and refining codes.

The process of generating and refining codes had a development/internal validity component and a second reliability/external validity component. Together the coding for these components lasted 6 months.

Development of internal validity in the coding content.

First, six potential codes were entered into the data base columns consistent with six subscales found on the Benefit Finding Scale (BFS; Tomich and Helgeson, 2004): acceptance, worldview, family, social, personal control, and health behaviors. Two researchers (L.H. and J.G.) independently coded each narrative by copying and pasting phrases and sentences from the narrative into one or more of the existing six code columns or, if they did not fit that content, by placing it into a new column and creating a code name. This coding was discussed in weekly 1-hour review sessions attended by the two initial coders (L.H. and J.G.) and two additional coders (A.J. and R.N.-B.). Coding discrepancies were resolved through team consensus, whereas the creation of new codes and definitions was achieved through team discussion. A recursive process was employed, adjusting codes and code names until the team agreed they had reached saturation of content. After saturation, a final code book was created, naming and defining 18 content codes. Participant ID numbers and code prevalence percentages are provided in the “Results” section as a further indication of internal validity, that is, the coded response applied to more than one individual.

Assurance of reliability and external validity in the coding process.

Next, to insure the reliability of the coding process, the team repeated the process for the entire 119 participants. Two independent reviewers (L.H. and J.G.) coded each narrative, assigning responses to codes according to the coding definitions. Discrepancies were resolved in weekly team meetings through team consensus.

Generating and analyzing themes.

Following the generation of specific codes, two members of the team (J.M. and A.J.) assembled final thematic groupings through a process of discussion and manuscript revision.

Results

Participant characteristics

Participants ranged in age from 41 to 88 years (M = 65.50 and standard deviation (SD) = 9.16); most described their race as Caucasian (79%), and about half (46%) had a high school education or less (Table 1). The majority (98.3%, n = 117) were male, as the sample drew from the US Veterans Health Administration. A small number (13.4%) reported combat-related PTSD symptoms exceeding a screening threshold, and 11.8 percent reported having received treatment for PTSD. Participants had head and neck (33%), esogastric (7%), or colorectal (60%) cancers of American Joint Committee on Cancer Stage I (28%), II (29%), III (24%), or IV (19%); 79 percent received surgery, 56 percent received chemotherapy, and 38 percent received radiation (treatments were not mutually exclusive). Less than half (40%) reported combat exposure during military service.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Variable | Sub category | Statistic |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | ||

| Age (years) | Range 41–88 | 65.50 | 9.16 |

| n | % | ||

| Race | African American or Other | 25 | 21.0 |

| Caucasian | 94 | 79.0 | |

| Education | High school graduate or less | 55 | 46.2 |

| Some college or more education | 64 | 53.8 | |

| Combat | Combat exposed | 71 | 59.7 |

| No combat | 48 | 40.3 | |

| Cancer type | Head and neck | 40 | 33.6 |

| Esogastric | 8 | 6.7 | |

| Colorectal | 71 | 59.7 | |

| Tumor stage | I | 33 | 27.7 |

| II | 35 | 29.4 | |

| III | 28 | 23.5 | |

| IV | 23 | 19.3 | |

| Treatment | Surgery | 94 | 79.0 |

| Chemotherapy | 67 | 56.3 | |

| Radiation | 45 | 37.8 | |

SD: standard deviation.

Themes and codes

Seven themes emerged from the data. The first theme was searching for meaning (1), the next two themes related to meaning-making processes—absent or ambiguous meaning making (2) or lifespan developmental meaning making (3), with the remaining themes pertaining to meanings made—health/bodily (4), existential (5), social (6), and personal (7).

Theme 1: searching for meaning.

Evidence for searching for meaning emerged from responses to close-ended questions (Table 2). About half of the participants (43%) reported searching for meaning in response to “have you ever tried to understand why you got cancer?” Most (72%) stated they felt “settled or very settled” in their understanding of why they got cancer, with only 5 percent stating they felt unsettled and 22 percent neutral. Most (76%) said they never or rarely thought about why they got cancer, with only 10 percent stating they think of it often or very often. Approximately half of the participants (53%) said that having cancer changed their view of life or its meaning for them and fewer said cancer changed their view of death (22%) or religious/spiritual beliefs (19%).

Table 2.

Endorsement of close-ended items on the meaning-making interview.

| Question | Response | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Have you ever tried to understand why you got cancer? | Yes No |

42.9 57.1 |

| 2. Has cancer changed your view of life or its meaning for you? | Yes No |

52.9 47.1 |

| 3. Has cancer changed your view of death or its meaning for you? | Yes No |

21.6 78.4 |

| 4. Have your religious or spiritual beliefs changed as a result of your cancer? | Yes No |

19.3 80.7 |

| 5. How often do you ponder or try to understand why you got cancer? | Never–rarely Sometimes |

76.1 13.7 |

| Often–very often | 10.3 | |

| 6. How satisfied or dissatisfied do you feel you are with your understanding of why you got cancer? | Settled–very settled Neutral |

72.4 22.4 |

| Unsettled–very unsettled | 5.2 | |

| 7. Did any of these life challenges help you to be more prepared to cope with the stress of cancer? | Yes No |

74.8 25.2 |

Theme 2: absent or ambiguous meaning making.

For some, our questions about searching for meaning and making meaning did not fit with their experience of cancer—applying to those who stated they did not reflect on the meaning of cancer, or who did reflect but did not change beliefs, and those who were uncertain.

No reflection.

Across the sample, one in four participants (24%) responded in a manner that reflected an apparent absence of meaning-making processes: “I really don’t know how I would describe it. It’s not something I really talk about. It’s in the past. It’s over” (1066); “No [I] never searched for the meaning of cancer in my life. No life lesson … I just don’t worry about it” (2101).

Reflection, but no change.

For some (27%), comments revealed meaning making but no change: “I appreciated life so much before, it’s hard for me to say. I had an awesome life … I’m one of the luckiest bastards I know” (1070); “[Cancer] hasn’t really changed my view of life that much. If I was younger it may have changed it … I just hope I don’t get it again” (2041).

Uncertain.

Others (20%) expressed uncertainty about their meaning-making process. For example, participants said, “My life is the same … It’s hard to explain. I don’t know” (1066); “No, I don’t know, really” (1043); and “I don’t have an answer for that” (1037).

Theme 3: meaning-making processes.

Participants stated that previous life challenges prepared them to cope with the stress of cancer. Content coding revealed three specific ways— previous life events, military experience, and personal traits.

Learning from previous life events.

Participants (39%) discussed experiences that helped them make meaning and cope:

Addiction. [I] had to have faith in something stronger than me because I couldn’t control it. Gave me a faith that if it was in the will that it could happen… Faith that if it were the higher being’s will I would survive this, and if not that I could go through it with dignity. (2055)

Some spoke more generally: “I have faced hard times and difficulties all my life. I come to expect good and bad times as a part of my life” (2083).

Applying military experiences.

As a veteran sample, military experience was cited (13%) in making meaning: “Combat taught me to expect the unexpected” (2084); “From the combat experience it is the intense training that goes before, and the awareness one gains, which instills a will to survive” (2073). Some comments revealed that the meaning made out of combat helped with cancer:

“What I saw in Vietnam made me accept this stuff for what it is. Some people would say I’m not emotional, but I just learned how to deal with it. I had to …. It made me unaffected by bad things that happen.” (2019)

Capitalizing on traits.

Many (61%) elaborated on personal qualities that influenced meaning making and coping: “I’ve always appreciated my life. We’ve had everything we’ve ever wanted. What we’re doing right now, we’ve been doing every day. We laugh. We can’t let it get us down” (1042) and “I have many weaknesses, but I think one of the strengths I’ve always had is the ability to cope positively with difficult situations. I believe I was born with this ability” (1004).

Theme 4: health and body meanings made.

Our conversations with participants about how they understood cancer revealed meanings made that was for some very specific, situational, and concrete, focusing on health behaviors and their body. Responses also indicated meanings made in relation to future health behaviors.

Specific causal attributions.

Most (73%) described specific reasons they perceived they got cancer such as smoking, diet, and toxic exposures in the military or at work: “[I got cancer from] exposure to Agent Orange. No Life lesson, just in Vietnam and got exposed to Agent Orange” (2084); Age was also cited as an explanation: “I am old. Everybody that is old gets cancer” (2047).

Physical body.

References to the body were woven into meanings (16%): “I think it was there. Something in my body wasn’t correct” (1057); “how fragile the body is, and how quickly you can move down the ladder. But also, how resilient the body is” (1022).

Health behavior.

A subset (15%) reported health behavior change: “I stopped drinking, smoking, and started eating right. I am more health conscious, it makes you realize you can hurt yourself or help yourself” (2060). More negative changes were also cited: “I isolated myself, got lazy, and kept drinking coffee and smoking” (1037).

Theme 5: existential meanings made.

Some of the meaning-making content was more existential in nature as reflected in the coded content below.

Worldview.

Many participants (71%) provided a meaning-making response that reflected a global worldview, including negative, positive, or unchanged views. Many participants made succinct statements about life being “good” or “great” (1058, 2022, 2041, 2053, 2072, 2074, and 2078). Others were more negative: “My outlook on life hasn’t changed—the world is the same. We are in trouble. We have been in trouble” (1051). Still others emphasized the importance of enjoying life, “I believe I have always held a very positive attitude toward life and enjoyed it to the fullest” (2043), and the role of fate, “We’re predestined since before birth … It was meant to be. Everything that happens, happens for a reason” (1023); “I do believe everything happens for a purpose” (2043).

Acceptance.

A majority (72%) cited acceptance: “It just happens. It just happened to happen to me … you can’t change what’s happening. You learn to deal with it” (1026); “It is what it is. There’s nothing else to go about it … I’m not serene, just accepting. There’s really nothing I can do” (1040).

Spirituality.

Comments about spiritual meaning making (62%) were seen, such as “I have gotten close to God. [Cancer] made me realize there is a higher being and I need to get closer to him” (2008); “I don’t believe a higher power selected me to have a specific disease …to me it was the obvious answer. I do believe in a supreme being, but not one who is vengeful, hurtful or cruel” (2096).

Theme 6: social meanings made.

Another theme in meanings made related to the participants’ family and friends.

Family relations.

Some (11%) referred to family: “I learned to appreciate my spouse and her efforts to serve and help me” (2084); “my family who was there for me and we are closer now and I am stronger for it” (2030).

Social relations.

Others (23%) extended beyond family: “It has given me appreciation for family and friends. You have a new-found appreciation. You give the closer things extra thought” (1067); “you see fellow Veterans in the same situation or in worse situations. We share things with each other that you might not share with your family. Everyone here has a sympathetic ear” (2102).

Theme 7: personal meanings made.

Finally, some meanings made were about the individual—the self or life plans that was often, but not always oriented toward finding benefits.

Personal growth.

About one-third (30%) perceived personal growth: “Cancer has definitely changed my life, and also my outlook on life … I needed to re-access things - my, views, habits, outlook, causes and effects to living a clean and productive life” (2049). But, as in other areas, some reported negative perceptions:

Cancer has caused me to reevaluate, but it hasn’t been a helper (1037); “It stops you from doing what you use to do - from enjoying it, from just going to the store normal. It makes you worry. … Being irritable, being upset. I feel like I’m bringing problems on myself. I will be mad and no one will know why. (1051)

New possibilities.

A few participants (7%) reflected on new possibilities: “I just want to do more on my bucket list” (2020); “It’s not the end. It’s a chance to expand your thinking and see life totally, the good and the bad of it” (2055).

Appreciation of life.

Appreciation was identified by some (29%): “I appreciate life more now, it’s nice to have a second chance to get it right” (2023). “It made me appreciate it a lot more. Aces, my life right now, aces” (1042); “Life is a blessing. I’m blessed each day and thankful for each day I have” (2024); “I appreciate life more now, it’s nice to have a second chance to get it right” (2023).

Mortality salience.

Statements about the personal salience of death were also identified (29%): “Death is more definite to me now, after I’ve had cancer. … It just proved to me that we all have to go sometime” (1006); “my feeling of invincibility really got damaged” (2026); For some, these realizations were tied to concepts of appreciation: “I’m getting near the end, and I have to make it clear how I feel about the end of my life. I won’t live forever. I try to volunteer, and am glad I have these memories” (1003).

Discussion

There has been considerable study on meaning making, particularly the potential for growth in the aftermath of stressful experiences, including cancer (Cordova et al., 2007; Helgeson et al., 2006; Tedeschi et al., 1998). In this study, we used semi-structured interviews to confirm and extend this literature by examining the prevalence of searching for meaning, processes of meaning making, and contents of meanings made. Our methods extend previous work in their focus on middle to older age, mostly male survivors of oral-digestive cancers.

Searching for meaning

A simple starting point is to quantify just how frequently individuals do engage in meaning making after a stressful event. The answer depends on how it is asked. In response to discrete yes/no questions, about half of the participants reported searching for meaning of why they got cancer (43%) and said cancer changed their view of life (53%). However, as we coded how participants arrived at meanings and specific meanings made, in some areas up to about three-quarters of the participants gave a response that indicated “meaning making.” This discrepancy may be due to several factors. Perhaps some participants make meaning without identifying it as such, therefore did not endorse searching or changed life views. Perhaps others made meaning without searching or made meanings that they did not see as reflecting a changed view of life. These closeended questions demonstrate that estimating the prevalence of searching for meaning and making meaning is clearly linked to the phrasing of the meaning-making questions. In sum, 43– 73 percent of participant’s responses indicated meaning making, clarifying that many but not all may engage in meaning making after the stress of cancer.

Not searching for or making meaning

The responses to the yes/no questions as well as content of narrative responses revealed that some participants do not identify with meaning making. About one-quarter of the participants specifically stated they had reflected on the meaning of cancer but not changed their views on life or simply had not reflected. Reports of meaning-making studies do not often describe the lack of meaning making in some individuals. Not necessarily searching for or making meaning is an important finding in understanding that the range of responses to stressful events includes a “moving on” or resilient response (Martin et al., 2014). Although not studied here this resilient and/or non-reflective response likely relates to the nature of the stress and how the threat is perceived (Weathers and Keane, 2007), having previously made meanings that are adaptively applied to the present stressor (Thompson et al., 2018), and perhaps the individual’s tendency to be reflective. In short, making meaning and not making meaning are equally valid responses to stressful experience.

Meaning-making processes

Interview responses also provided insights into meaning-making processes and provided support for developmental frameworks. Respondents described meaning-making processes that drew from past experience or personal attributes. Individuals often perceived that having faced and adapted to previous stressors permitted greater resiliency in the face of the cancer stressor, consistent with concepts of resilience (Elder and Shanahan, 2006; McAdams and Bowman, 2001). In this military veteran sample, having survived combat experience in the past was a prism for viewing the cancer experience for a small proportion of the sample (13%). As described by others (Spiro et al., 2016), the long-term effects of military may result in cumulative advantage when coping with subsequent stressors. While having learned from military experience is unique to the veteran experience and would not be found in non-veteran sample, the general principle of learning from previous experience and/or from previous mental health treatment appears relevant and should be further studied.

Meanings made

The meanings made—the beliefs and cognitions—were diverse and ranging from concrete to existential and positive to negative. Meanings were at times specific to the body, toxic exposures, and health consequences and goals. Other contents were related to views of the world— such as worldview, spirituality, and acceptance; views of others—family and friends; and views of the self and one’s self in the world—personal growth, new possibilities, appreciation, and mortality salience. The range of meanings—from concrete to abstract—likely reflects the range of ways that people make meaning and was also influenced by the specific questions we used (e.g. starting with “why do you think you got cancer” may have pulled for a concrete response).

These same themes have been consistently reported in studies of stress-related growth by patients (Tedeschi et al., 1998; Tomich and Helgeson, 2004) and oncology providers (Aldaz et al., 2017). The consistency in findings between this mostly male sample of oral-digestive cancer survivors and previous studies of mostly female breast cancer survivors indicates some commonalities across the human experience, regardless of gender or specific cancer type. The discussion of mortality salience—that the experience of a serious life-threatening illness like cancer has made one’s own inevitable death more salient or real—is a somewhat novel finding and makes sense given the nature of cancer as a life-threatening illness.

Also unique in this study is documenting that meanings made in these domains were not always of perceived growth—at times it was of perceived loss such as families being less close or health behaviors worsening. It is, however, somewhat difficult to categorically call a statement as reflecting “growth” or “depreciation.” For example, is the statement “my feeling of invincibility really got damaged,” positive or negative? It seems possible that for some, growth occurred by shifting to a less idealistic view of life—perhaps less positive, but potentially leading to more resilience.

Applications to practice

Cancer is a prevalent and in many cases increasingly survivable illness. As such, there is a shift to focus on the needs of cancer survivors—and in particular the gap in care that may follow a period of treatment. In that vein, there has been a new emphasis on psychological care for patients beyond their cancer treatment and into survivorship (Artherholt and Fann, 2012). While many adapt to cancer well, about one-third of survivors experience distress (Institute of Medicine, 2005).

Meaning making in cancer survivors has been linked to well-being and adjustment (Park et al., 2008). Thus, using an approach like meaning-centered therapy may be relevant for cancer survivors (Lee et al., 2006a).

Limitations

This study has numerous limitations. Participants were homogeneous in terms of race/ethnicity, gender, and veteran status. We chose to study veterans as this is our clinical setting and the source of the financial support for this study. Additional studies including veterans and non-veterans could clarify potential differences if any. In addition, the responses participants provided were shaped by the prompts we used. Other prompts may be useful in identifying additional relevant content related to meaning-making processes and contents. We used written notes rather than voice recording and transcription, which may have introduced some error into our reporting of participant responses. We did not examine whether responses varied by stressor characteristics such as cancer stage, treatment type/intensity, or initial treatment response, but instead approached the stressor of “cancer” as a unitary phenomenon. In addition, all participants in this study were 12 months post diagnosis. Meanings may change and evolve over time, so it would be interesting to follow survivors as they get further away from diagnosis and treatment. Future studies should examine whether meaning making differs in relation to these characteristics.

Conclusion

In summary, these results support that after cancer, as with other stressful experiences, a portion of survivors engage in rich meaning making that may include benefit finding and also meaning making about perceived losses. Additional research that follows individuals longitudinally across a longer time period may help to clarify the utility of meaning making for reducing distress. When working with adults after cancer treatment, it may be useful to explore experiences of meaning making in adapting to cancer survivorship.

Acknowledgements

Research involved human participants. All participants provided informed consent under IRB-approved procedures.

Funding

The author(s) received the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service (grant no. 5I01RX000104–02). This material is the result of work supported with the resources and the use of facilities at the Boston VA Medical Center and the Houston VA Health Services Research & Development Center of Excellence (HFP90–020) at the Michael E DeBakey VA Medical Center.

Appendix 1

Meaning-making interview questions (category)

1. Have you ever tried to understand why you got cancer? Yes No

2. Why do you think you got cancer? [open ended—meaning made]

3A. If yes, you have tried to understand, How did you come to that understanding. What brought you to think this way?

3B. If no, tell me more about why not. Why is this something you do not think about? [open ended—meaning making process]

4. How often do you ponder or try to understand why you were diagnosed with cancer?

Never Rarely Sometimes Often Very Often

5. How satisfied or dissatisfied do you feel you are with your understanding of why you got cancer?

Very Settled / Neutral Unsettled / Very settledCertain Uncertain Unsettled

6. Imagine explaining to someone close to you the impact of cancer on your life, what would you say? [open ended— meaning made]

7. Have close friends or family influenced the way you think about or understand cancer? [open ended—meaning making process]

8. Has cancer changed your view of life, or its meaning for you? Yes No

9. What is your view of life now? [open ended—meaning made]

10. Has cancer changed your view of death, or its meaning for you? Yes No

11. What is your view death now? [open ended—meaning made]

12. How did having cancer cause you to change your view of death? [open ended—meaning making process]

13. Have your religious or spiritual beliefs changed as a result of your cancer? Yes No

14. If so how? [open ended—meaning made]

15. What qualities within yourself helped you most in coping with cancer? Are there any qualities within yourself that made it harder to cope with cancer? [open ended—meaning making process]

16. Did any life challenges help you to be more prepared to cope with the stress of cancer? (Combat, Death of a loved one, serious illness in a loved one, divorce, family problems, work problems, serious illness in myself, overcoming addiction). Yes No

17. How did these experiences help you to cope with cancer? [open ended—meaning making process]

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aiena BJ, Buchanan EM, Smith CV, et al. (2016) Meaning, resilience, and traumatic stress after the deepwater horizon oil spill: A study of Mississippi coastal residents seeking mental health services. Journal of Clinical Psychology 72(12): 1264–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldaz BE, Treharne GJ, Knight RG, et al. (2017) Oncology healthcare professionals’ perspectives on the psychosocial support needs of cancer patients during oncology treatment. Journal of Health Psychology 22(10): 1332–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrykowski MA, Steffens RF, Bush HM, et al. (2017) Posttraumatic growth and benefit-finding in lung cancer survivors: The benefit of rural residence? Journal of Health Psychology 22(7): 896–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artherholt SB and Fann JR (2012) Psychosocial care in cancer. Current Psychiatry Reports 14(1): 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle CC, Stanton AL, Ganz PA, et al. (2016) Posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors: Does age matter? Psycho-oncology 26: 800–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V and Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cafaro V, Iani L, Costantini M, et al. (2016) Promoting post-traumatic growth in cancer patients: A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of guided written disclosure. Journal of Health Psychology. Epub ahead of print 1 November 2016. DOI: 10.1177/1359105316676332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EB and Dalenberg CJ (2000) A conceptual framework for the impact of traumatic experiences. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 1(1): 4–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova MJ, Giese-Davis J, Golant M, et al. (2007) Breast cancer as trauma: Posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings 14(4): 308–319. [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo ES, Ryff CD and Singer BH (2009) Psychosocial adjustment among cancer survivors: findings from a national survey of health and well-being. Health Psychology 28(2): 147–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondanville KA, Blankenship AE, Molino A, et al. (2016) Qualitative examination of cognitive change during PTSD treatment for active duty service members. Behavioral Research and Therapy 79: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH and Shanahan MJ Jr (2006) The life course and human development In: Lerner RM and Damon W (eds) Handbook of Child Psychology, Vol. 1: Theoretical Models of Human Development (6th edn). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 665–715. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay L (2002) “Outing” the researcher: The provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qualitative Health Research 12(4): 531–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groarke A, Curtis R, Groarke JM, et al. (2016) Post-traumatic growth in breast cancer: How and when do distress and stress contribute? Psychooncology 26: 967–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglietti CL, Rosen B, Murphy KJ, et al. (2010) Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress in women undergoing an ovarian cancer investigation. Psychological Services 7(4): 266–274. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AM, Laurenceau JP, Feldman G, et al. (2007) Change is not always linear: the study of nonlinear and discontinuous patterns of change in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology Review 27(6): 715–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Reynolds KA and Tomich PL (2006) A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 74(5): 797–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (2005) From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R (1992) Shattered Assumptions: Towards a New Psychology of Trauma. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kangas M, Henry JL, and Bryant RA (2002). Posttraumatic stress disorder following cancer: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 22(4), 499–524. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00118-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernan WD and Lepore SJ (2009) Searching for and making meaning after breast cancer: Prevalence, patterns, and negative affect. Social Science and Medicine 68(6): 1176–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolokotroni P, Anagnostopoulos F and Tsikkinis A (2014) Psychosocial factors related to post-traumatic growth in breast cancer survivors: A review. Women Health 54(6): 569–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemeke A, Bargiel-Matusiewicz K and Kalamarz M (2017) Mixed psychological changes following mastectomy: Unique predictors and heterogeneity of post-traumatic growth and posttraumatic depreciation. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V (2008) The existential plight of cancer: meaning making as a concrete approach to the intangible search for meaning. Supportive Care in Cancer 16(7): 779–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V, Cohen SR, Edgar L, et al. (2006a) Meaning making and psychological adjustment to cancer: Development of an intervention and pilot results. Oncology Nursing Forum 33(2): 291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V, Cohen SR, Edgar L, et al. (2006b) Meaning making intervention during breast or colorectal cancer treatment improves self-esteem, optimism, and self-efficacy. Social Science & Medicine 62(12): 3133–3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Currier JM, Neimeyer RA, et al. (2010) Sense and significance: A mixed methods examination of meaning making after the loss of one’s child. Journal of Clinical Psychology 66(7): 791–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoSavio ST, Dillon KH and Resick PA (2017) Cognitive factors in the development, maintenance, and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Current Opinion in Psychology 14: 18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP and Bowman PJ (2001) Narrating life’s turning points: Redemption and contamination In: McAdams DP, Josselson R and Lieblich A (eds) Turns in the Road: Narrative Studies of Lives in Transition. Washington, DC: American psychological Association, pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Martin LA, Moye J, Street RL, et al. (2014) Reconceptualizing cancer survivorship through veterans’ lived experiences. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 32(3): 289–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyrick J (2006) What is good qualitative research? A first step towards a comprehensive approach to judging rigour/quality. Journal of Health Psychology 11(5): 799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen H, Therup-Svedenlof C, Backheden M, et al. (2017) Posttraumatic growth and depreciation six years after the 2004 tsunami. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 8(1): 1302691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy EA, Blanchard EB, Cirenza E, et al. (2000) Posttraumatic stress disorder in breast cancer patients following autologous bone marrow transplantation or conventional cancer treatments. Behaviour Research and Therapy 38(10): 1015–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik A, Martin L, Karel M, et al. (2013) Cancer survivor rehabilitation and recovery: Protocol for the Veterans Cancer Rehabilitation Study (VetCaRes). BMC Health Services Research 13 (1): 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL (2010) Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin 136(2): 257–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Edmondson D, Fenster JR, et al. (2008) Positive and negative health behavior changes in cancer survivors: a stress and coping perspective. Journal of Health Psychology 13(8): 1198–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, et al. (2003) The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): Development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry 9(1): 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rajandram RK, Jenewein J, McGrath C, et al. (2011) Coping processes relevant to posttraumatic growth: An evidence-based review. Supportive Care in Cancer 19(5): 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson KM (2015) Meaning reconstruction in the face of terror: An examination of recovery and posttraumatic growth among victims of the 9/11 World Trade Center attacks. Journal of Emergency Management 13(3): 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland JH and Bellizzi KM (2014) Cancer survivorship issues: Life after treatment and implications for an aging population. Journal of Clinical Oncology 32(24): 2662–2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare-Finch J and Lurie-Beck J (2014) A meta-analytic clarification of the relationship between posttraumatic growth and symptoms of posttraumatic distress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 28(2): 223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shand LK, Cowlishaw S, Brooker JE, et al. (2015) Correlates of post-traumatic stress symptoms and growth in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho-oncology 24(6): 624–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro A, Settersten RA 3rd and Aldwin CM (2016) Long-term outcomes of military service in aging and the life course: A positive re-envisioning. Gerontologist 56(1): 5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Sworowski LA, et al. (2002) Randomized, controlled trial of written emotional expression and benefit finding in breast cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology 20(20): 4160–4168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Park CL and Calhoun LG (eds) (1998) Posttraumatic Growth: Positive Changes in the Aftermath of Crisis. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson NJ, Fiorillo D, Rothbaum BO, et al. (2018) Coping strategies as mediators in relation to resilience and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 225: 153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomich PL and Helgeson VS (2004) Is finding something good in the bad always good? Benefit finding among women with breast cancer. Health Psychology 23: 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, El-Gabalawy R, Sledge WH, et al. (2015) Post-traumatic growth among veterans in the USA: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Psychological Medicine 45(1): 165–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Spek N, Vos J, Van Uden-Kraan CF, et al. (2017) Efficacy of meaning-centered group psychotherapy for cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine 47(11): 1990–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW and Keane TM (2007) The criterion a problem revisited: Controversies and challenges in defining and measuring psychological trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress 20(2): 107–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]