Abstract

Background

In this study, we aimed at estimating the prevalence and number of stroke survivors with hypertension, recommended pharmacological treatment, and above blood pressure target, according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines and the seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure guidelines.

Methods and Results

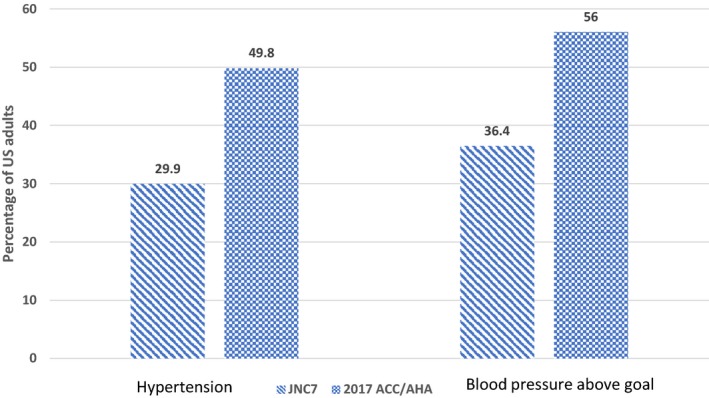

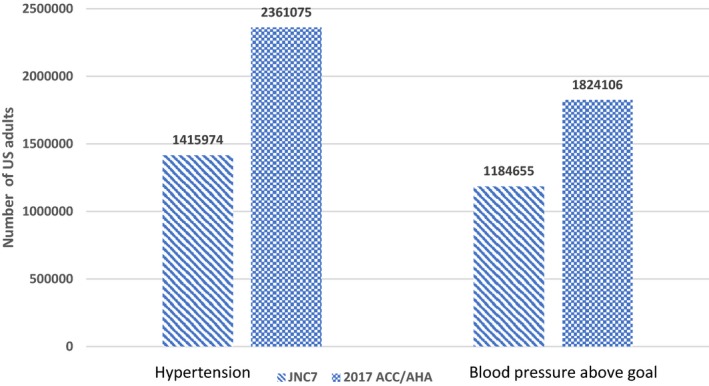

We included participants aged ≥20 years to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys between 2003 and 2014. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys is a series of publicly available, cross‐sectional, national, stratified, multistage probability surveys. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys received approval from the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board. Stroke was determined by self‐report. Blood pressure was estimated according to National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey protocol. Assessment of pharmacological treatment of hypertension was by self‐report. The proportion and number of stroke survivors with hypertension was 49.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 45.4%–54.2%) and 2 361 075 (95% CI, 2 035 251–2 686 899) per the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines versus 29.9% (95% CI, 26.2%–33.7%) and 1 415 974 (95% CI, 1 191 721–1 640 227) per seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure guidelines. Proportion and number of stroke survivors who were not at target blood pressure was 56% (95% CI, 51.2%–60.6%) and 1 824 106 (95% CI, 1 558 846–2 089 366) per 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines versus 36.3% (95% CI, 31.6%–41.4%) and 1 184 655 (95% CI, 984 128–1 385 182) per seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure guidelines.

Conclusions

Compared with seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure, the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association hypertension guidelines would result in a nearly 67% relative increase in the proportion of US stroke survivors diagnosed with hypertension and 54% relative increase in those not within the recommended blood pressure target.

Keywords: 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines, hypertension, JNC7 guidelines, stroke

Subject Categories: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Hypertension, Cerebrovascular Disease/Stroke

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

The implementation of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines will result in a greater number of stroke survivors with hypertension, at goal, and requiring antihypertensive treatments.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

There are anticipated challenges in implementing into practice the new 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines, with potential positive impacts on cardiovascular risk reduction and mortality among stroke survivors.

Hypertension is strongly associated with stroke.1, 2 It also carries a high mortality among patients with stroke and arguably has a stronger association with stroke than any other symptomatic vascular disease entity.2, 3 It is fortunately amenable to interventions including pharmacological treatments. Antihypertensive drugs are among the most prescribed medications in the United States.4 It is purported that greater blood pressure (BP) awareness and treatment has significantly contributed to the decline in stroke mortality in the United States over the past decades.2 Indeed, a meta‐analysis of 14 randomized controlled trials has shown a nearly 30% reduction in the risk of stroke recurrence with BP treatment.5 In the seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC7) guidelines, hypertension was defined for systolic BP (SBP) ≥140 or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥90 mm Hg, and pharmacological treatment in stroke survivors was recommended for SBP ≥140 or DBP ≥90 mm Hg.6 However, epidemiological data have demonstrated that the risk of stroke begins with levels of BP lower than these values.7 In light of these data, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association8 guidelines for prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of hypertension have lowered the cutoff for BP definition of hypertension in individuals at high risk of cardiovascular events, including patients experiencing stroke. In the new guidelines, a SBP ≥130 or DBP ≥80 mm Hg defines hypertension in stroke survivors. The new American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines also recommend initiating antihypertensive treatments and targeting SBP/DBP to <130/80 mm Hg for stroke survivors. It is anticipated that these changes will affect BP distribution among stroke survivors, with significant policy and economic implications. In this analysis, using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2003 to 2014, we estimated the percentage and number of US adult stroke survivors according to the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines and the JNC7 guidelines. Moreover, we estimated the percentage and number of stroke survivors with hypertension recommended for pharmacological treatment on the basis of the 2017 ACC/AHA versus the JNC7 guidelines. We also estimated the percentage and number of US adult stroke survivors taking antihypertensive medication with BP above target, according to 2017 ACC/AHA and the JNC7 guidelines. Finally, we extrapolated the potential impact of the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines on mortality among stroke survivors.

Methods

Data Source and Blood Pressure Measurement

We analyzed a 10‐year period from 2003 through 2014 of the NHANES's data set of adult participants who had at least 3 consecutive BP measurements. NHANES is a series of publicly available, cross‐sectional, national, stratified, multistage probability surveys. As publicly available data, the NHANES data set, the methods used in the analysis, and materials used to conduct the research are available to any researcher for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure. Details pertaining to the survey are available at the NHANES website.9 NHANES received approval from the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board. All participants were asked to sign an informed consent form. Per NHANES protocol, BP is measured by trained physicians (who are annually retrained and certified) using a mercury sphygmomanometer of appropriate size, determined by the participant's mid–right arm circumference. BP is calculated as the mean of the 3 consecutive BP measurements, obtained after 5 minutes of rest and at a 30‐second interval.

Study Variables

History of stroke was determined by self‐reported diagnosis by a healthcare provider. Individuals who had missing data for previous stroke were excluded. Age was divided into 4 categories: 20 to 44, 45 to 64, 65 to 79, and ≥80 years. Race/ethnicity was categorized as non‐Hispanic white (white), non‐Hispanic black (black), Mexican American, and other. Assessment of pharmacological treatment of hypertension was by self‐report. Participants who answered “yes” to both questions “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other healthcare professional that you had hypertension, also called high blood pressure?” and “Are you now taking prescribed medication for high blood pressure?” were considered to be taking antihypertensive medication.

Hypertension Definitions, Recommendations for Antihypertensive Medications, and Blood Pressure Treatment Goals

The JNC7 defined hypertension for levels of SBP ≥140 mm Hg or DBP ≥90 mm Hg. According to the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines, hypertension was defined for levels of SBP ≥130 mm Hg or DBP ≥80 mm Hg. On the basis of the JNC7 guidelines, pharmacological treatment was recommended for stroke survivors for SBP ≥140 mm Hg or DBP ≥90 mm Hg. It was deemed reasonable to achieve a SBP <140 mm Hg and a DBP <90 mm Hg. The 2017 AHA/American Stroke Association guidelines recommend initiating antihypertensive treatment in stroke survivors for SBP ≥130 mm Hg or DBP ≥80 mm Hg and set new target at SBP <130 mm Hg and DBP <80 mm Hg.

The study was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Institutional/Ethics Review Board. A detailed description of the survey is available at the NHANES website.9

Statistical Analysis

Frequency distribution and 95% confidence interval (CI) of BP were calculated across the following BP levels of SBP/DBP: <120/<80, 120 to 129/<80, 130 to 139/80 to 89, and ≥140/90 mm Hg. They were calculated overall and by sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Frequency distribution of hypertension was calculated according to cutoff points defining hypertension in each of the guidelines, overall and by sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Next, we estimated the number and 95% CI of adults with hypertension overall by type of guidelines to the 2007 ACC/AHA guidelines by treatment status. We also calculated the percentage, number, and 95% CI of stroke survivors with hypertension recommended for pharmacological treatment on the basis of the 2017 ACC/AHA and JNC7 guidelines. We then proceeded and calculated the percentage, number, and 95% CI of stroke survivors taking antihypertensive medication with BP above target, according to 2017 ACC/AHA and the JNC7 guidelines.

A binary variable of final “mortality” status (0=alive, 1=deceased) was created from publically used linked mortality NHANES files (2003–2010); a code of 1 indicates that the mortality status was ascertained through a probabilistic match to a National Death Index record (National Center for Health Statistics Surveys 2011 Linked Mortality Files, public‐use data dictionary).10 Mortality rate was computed by BP levels, as defined by the JNC7 and the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines.

All prevalence estimates were weighted to obtain nationally representative estimates.11 All analyses were performed using STATA 14.12 Level of significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

General Characteristics

We identified a total of 6 250 751 weighted participants aged ≥20 years with stroke, including 2 600 312 men (41.6%). Nearly 3 of 5 participants (57.6%) were aged ≥65 years. Overall during the period 2003 through 2014, 34.2% (95% CI, 29.7%–38.9%), 16.0% (95% CI, 13.3%–19.0%), 19.9% (95% CI, 16.5%–23.7%), and 29.9% (95% CI, 26.2%–33.8%) of stroke survivors had SBP/DBP levels of <120/80, 120 to 129/<80, 130 to 139/80 to 89, and ≥140/90 mm Hg. In general, older participants, non‐Hispanic blacks, and women had BP in the higher levels (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Weighted US Adults With Stroke by BP Levels on the Basis of 2003 to 2014 NHANES

| Demographic Variables | BP Classes, mm Hg | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <120/80 | 120–129/<80 | 130–139/80–89 | ≥140/90 | |

| Overall | 34.2 (29.7–38.9) | 16.0 (13.3–19.0) | 19.9 (16.5–23.7) | 29.9 (26.2–33.8) |

| Male sex | 44.5 (35.2–54.2) | 48.3 (37.4–59.4) | 49.0 (38.8–59.2) | 38.2 (31.4–45.5) |

| Age group, y | ||||

| 20–44 | 17.3 (11.7–24.8) | 9.9 (4.5–20.1) | 5.4 (2.5–11.4) | 2.7 (1.0–6.4) |

| 45–64 | 37.1 (29.7–45.0) | 28.8 (20.8–38.2) | 41.8 (32.4–51.7) | 28.5 (22.0–35.9) |

| 65–79 | 30.8 (25.2–37.0) | 45.7 (35.9–55.7) | 34.1 (24.9–44.5) | 37.9 (31.4–44.8) |

| ≥80 | 14.8 (11.0–19.6) | 15.6 (10.8–22.1) | 18.7 (12.5–26.8) | 30.9 (25.1–37.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 74.2 (68.4–79.2) | 72.3 (62.1–80.5) | 76.6 (68.8–82.8) | 66.5 (59.5–72.9) |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 12.6 (9.5–16.4) | 9.7 (6.3–14.4) | 12.4 (8.1–18.3) | 19.1 (14.4–24.8) |

| Mexican American | 6.3 (3.7–10.3) | 6.3 (3.7–10.3) | 2.8 (1.3–5.7) | 4.3 (2.4–7.3) |

| Others | 6.9 (4.2–11.0) | 11.7 (5.6–23.0) | 8.2 (4.8–13.8) | 10.1 (6.6–15.1) |

Data are given as percentage (95% confidence interval). BP indicates blood pressure; NHANES National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Prevalence and Number of Stroke Survivors With Hypertension and Recommended Pharmacological Treatment, According to 2017 ACC/AHA and JNC7 Guidelines

According to the JNC7 guidelines, 29.9% (95% CI, 26.2%–33.7%) of stroke survivors, corresponding to 1 415 974 US population, had hypertension and would be recommended pharmacological treatment. On the other hand, on the basis of the new recommendation, 49.8% (95% CI, 45.4%–54.2%; ie, 2 361 075 stroke survivors) met the criteria for hypertension and would be recommended pharmacological treatment. The total prevalence of hypertension increased by 66.7%, and the number of stroke adult population increased by 945 101, with the new guidelines (Table 2, Figures 1 and 2). An increase in the prevalence and number of stroke population with hypertension and recommended pharmacological treatment was observed across all age, sex, and races/ethnicities in the new recommendation.

Table 2.

Percentage and Number (95% CI) of Weighted US Adults With Stroke Meeting the Definition for Hypertension and Recommended Antihypertensive Medication, According to the 2017 ACC/AHA and the JNC7 Guidelines, on the Basis of the 2003 to 2014 NHANES

| Demographic Variables | JNC7 Guidelinea | 2017 ACC/AHA Guidelinea | Relative % Change Between 2017 ACC/AHA and JNC7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N (95% CI) | % | N (95% CI) | % | |

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 26.0 (21.0–31.7) | 544 927 (399 242–690 612) | 47.7 (40.9–54.6) | 998 589 (786 743–1 210 434 | 83.3 |

| Women | 32.9 (28.2–37.9) | 871 047 (722 893–1 019 200) | 51.4 (46.0–56.8) | 1 362 486 (1 150 703–1 574 269) | 56.4 |

| Age group, y | |||||

| 20–44 | 9.0 (3.7–19.9) | 40 728 (6580–74 875) | 20.1 (10.4–35.1) | 91 248 (32 866–149 629) | 124.0 |

| 45–64 | 25.1 (19.1–32.3) | 407 099 (289 526–524 672) | 49.8 (41.6–58.0) | 805 634 (626 508–984 760) | 97.8 |

| 65–79 | 31.4 (26.0–37.4) | 534 621 (399 670–669 572) | 50.4 (43.6–57.2) | 857 753 (674 005–1 041 501) | 60.4 |

| ≥80 | 44.8 37.1–52.7 | 443 525 (330 020–537 030) | 62.7 (55.0–69.7) | 606 440 (476 538–736 341) | 36.7 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 27.6 (23.5–32.1) | 942 220 (740 594–1 143 845) | 48.5 (43.2–53.7) | 1 653 606 (1 344 611–1 962 601) | 75.5 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 40.3 (33.7–47.3) | 269 942 (191 555–348 328) | 58.8 (51.1–66.1) | 393 720 (294 475–492 964) | 45.8 |

| Mexican American | 25.6 (16.2–37.7) | 59 304 (28 396–90 213) | 36.8 (25.6–49.5) | 85 371 (50 104–120 637) | 43.9 |

| Others | 33.8 (24.1–45.0) | 144 508 (83 131–205 885) | 53.4 (41.2–65.2) | 228 378 (149 611–307 145) | 58.0 |

| Total | 29.9 (26.2–33.7) | 1 415 974 (1 191 721–1 640 227) | 49.8 (45.4–54.2) | 2 361 075 (2 035 251–2 686 899) | 66.7 |

ACC/AHA indicates American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; CI, confidence interval; JNC7, seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Represents both hypertension and recommended antihypertensive medication.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of hypertension and blood pressure above goal according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC7) guidelines.

Figure 2.

Number of participants with hypertension and blood pressure above goal according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC7) guidelines.

Prevalence and Number of US Stroke Survivors Taking Antihypertensive Medication With BP Above Target, According to the 2017 ACC/AHA and JNC7 Guidelines

The total prevalence of adult stroke population taking antihypertensive treatment with BP above goal, according to the JNC7 guidelines and 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines, was 36.3% (95% CI, 31.6%–41.4%) and 56% (95% CI, 51.2%–60.6%), respectively. This represented a 53.9% relative increase in adult stroke survivors with BP above goal. The corresponding number of stroke survivors on antihypertensive medication and above goal was 1 184 655 (95% CI, 984 128–1 385 182) and 1 824 106 (95% CI, 1 558 846–2 089 366), respectively, representing a 639 451 increase in stroke population on antihypertensive medications with BP above goal (Table 3, Figures 1 and 2).

Table 3.

Percentage and Number (95% CI) of Weighted US Adults With Stroke Taking Antihypertensive Medication With BP Above the 2017 ACC/AHA and the JNC7 Guidelines, Treatment Goal, on the Basis of the 2003 to 2014 NHANES

| Demographic Variables | JNC7 Guidelinea | 2017 ACC/AHA Guidelinea | Relative % Change Between 2017 ACC/AHA and JNC7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N (95% CI) | % | N (95% CI) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 31.8 (25.3–39.0) | 469 705 (335 115–604 296) | 51.3 (43.5–59.0) | 757 822 (579 225–936 419 | 61.3 |

| Women | 40.1 (33.9–46.6) | 714 950 (578 974–850 925) | 59.8 (53.7–65.6) | 1 066 284 (888 365–1 244 202) | 49.1 |

| Age group, y | |||||

| 20–44 | 26.9 (11.6–50.8) | 37 060 (3688–70 431) | 51.6 (26.1–76.3) | 71 021 (16 547–125 494) | 91.6 |

| 45–64 | 32.7 (24.7–41.8) | 354 650 (244 564–464 735) | 54.2 (44.5–63.5) | 587 397 (436 089–738 704) | 65.6 |

| 65–79 | 34.6 (27.8–42.0) | 456 174 (335 524–576 824) | 54.3 (46.7–61.8) | 716 870 (560 527–873 213) | 57.1 |

| ≥80 | 46.8 (37.4–56.4) | 336 770 (251 432–422 109 | 62.4 (53.4–70.5) | 448 817 (349 863–547 772) | 33.8 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 34.1 (28.6–40.1) | 763 382 (588 615–938 148) | 54.6 (49.0–60.0) | 1 219 352 (982 414–1 456 290) | 59.7 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 44.3 (36.6–52.2) | 237 953 (163 811–312 093) | 61.8 (53.4–69.4) | 331 963 (238 809–425 117) | 39.5 |

| Mexican American | 36.6 (23.7–51.7) | 53 236 (24 680–81 792) | 46.3 (32.3–60.9) | 67 478 (34 873–100 081) | 26.7 |

| Others | 38.0 (25.4–52.4) | 130 084 (68 856–191 311) | 60.0 (43.9–74.2) | 205 313 (125 873–284 752) | 57.8 |

| Total | 36.3 (31.6–41.4) | 1 184 655 (984 128–1 385 182) | 56 (51.2–60.6) | 1 824 106 (1 558 846–2 089 366) | 53.9 |

ACC/AHA indicates American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; JNC7, seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Represents both hypertension and recommended antihypertensive medication.

Mortality Rate by 2017 ACC/AHA and JNC7 Guidelines Among Stroke Survivors

Mortality rate during the period of 2003 through 2010 was 5.55% among those with a SBP <130 mm Hg or DBP <80 mm Hg; meanwhile, for those with a SBP <140 mm Hg or DBP <90 mm Hg, mortality rate was 8.25%, corresponding to a 32.72% relative mortality reduction.

Discussion

In this top‐down analysis, we found that implementing the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines would result in a nearly 67% increase in the proportion of stroke population with hypertension, and recommended antihypertensive treatment. The number of stroke survivors not at goal would increase by 54% with the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines.

It is established that hypertension increases the risk of stroke in a dose‐response pattern. For example, in a meta‐analysis of individual data of 1 million adults from 61 prospective studies, the risk of stroke was evident for SBP levels as low as 115 mm Hg and DBP starting at 75 mm Hg.7 Cardiovascular prevention benefits in patients with at usually recommended BP goals compared with those at lower goals have been evaluated in 3 pivotal clinical trials. The SPS3 (Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Stroke) trial, which included patients within 18 months of index symptomatic lacunar infarction, found no benefit of intensive BP on cardiovascular prevention. The ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) trial and the SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) did not include patients with stroke and, therefore, no data on stroke secondary prevention were available. In the ACCORD trial, which included only patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus, no benefit on cardiovascular prevention was found.13, 14, 15 In the SPRINT, lowering SBP to <120 mm Hg versus 140 mm Hg in people with a SBP of ≥130 mm Hg and an increased cardiovascular risk, but without diabetes mellitus, resulted in significantly lower rates of fatal and nonfatal major cardiovascular events and death from any cause.15 In subgroup analyses, no benefits on stroke prevention were apparent in both the SPRINT and ACCORD trial. In all, aforementioned studies were limited by the noninclusion of participants with stroke or the inclusion of only a subpopulation of patients with stroke. Their results need to be contrasted with the findings from a recent meta‐analysis of 14 randomized controlled trials of secondary stroke prevention that demonstrated a linear and positive association between BP reduction and the risk of recurrent stroke and cardiovascular events. The authors suggested that a target of <130 mm Hg may be effective for secondary stroke prevention.5 Altogether, these studies were among the catalyzers that helped revise hypertension definition, pharmacological treatment recommendation, and BP targets in the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines. In addition to setting new cutoffs for BP definition, pharmacological treatment recommendations, and targets, the new guidelines have provided a new categorization into 4 levels. As in the JNC7 guidelines, the aim for defining these categories was to facilitate clinical practice and public health decisions. The JNC7 report categories included SBP/DBP levels of <120/80 mm Hg (normal), 120 to 139/80 to 89 mm Hg (prehypertension), 140 to 159/90 to 99 mm Hg (hypertension stage 1), and ≥160/100 mm Hg (hypertension stage 2). The only category unchanged is the “normal BP.” Interventions, including pharmacological and nonpharmacological, are recommended for lower levels of BP.6, 8 The finding that less than one third of stroke survivors have normal BP, according to the new guidelines, is expected to trigger earlier pharmacological interventions (for SBP/DBP >130/90 mm Hg) and lifestyle modifications among stroke survivors. Lifestyle modifications to prevent cardiovascular events in stroke survivors have been well summarized in 3 recent meta‐analyses.16, 17, 18 One of the main findings from these meta‐analyses is a 1.34– to 4.21–mm Hg reduction in SBP with lifestyle changes. Although these studies found no benefit of lifestyle changes on cardiovascular events rates, the reduction in BP observed may be of significant importance at a population level because a 1–mm Hg reduction in SBP has been associated with a 4% reduction in stroke recurrence rate19 and a 10% reduction in mortality rate.20 The duration of follow‐up in studies included in these analyses was usually short, and the pooled number of participants was relatively small, ranging from 2478 to 6373 participants. The benefits of lifestyle interventions on cardiovascular rate reduction in stroke survivors would be more robust with prolonged and multimodal intervention, including pharmacological interventions. This was observed in other secondary prevention programs, such as those for coronary heart disease.21 There is also evidence from observational studies that lifestyle modifications, including abstinence from smoking, low body mass index, moderate alcohol consumption, regular exercise, and healthy diet, decrease the risk of stroke and stroke‐related death.22 Such benefits would, in theory, be greater in stroke survivors than in the general population. However, as shown in this study, fewer than half of stroke survivors would be at goal with the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines, outlining the magnitude of efforts to deploy to implement and disseminate the new guidelines. Lessons from prior guidelines have taught us that improving hypertension control is a complex task that includes, among other factors, patients’ motivation, appropriate communication between clinicians and their patients, and careful cost of medication considerations.6 On a positive note, estimates from NHANES suggest that achieving BP control at a large scale is possible. For example, between 1976 to 1980 and 2007 to 2008, in the general population, the rates of hypertension awareness, treatment, and control have increased from 51% to 81%, 31% to 73%, and 10% to 50%, respectively.23 Attributing these changes to the 7 JNC reports on the detection, evaluation, and treatment of high BP, published between 1977 and 2003, is difficult because several government or professional society programs were ongoing during the same period of time.2 In the general population, the new guidelines will result in a substantial increase in the prevalence and absolute number of people with hypertension in the United States (from 31.9% according to the JNC7 guidelines to 45.6% according to the new guidelines) but in only a small increase in the percentage of Americans recommended pharmacological treatment (from 34.3% to 36.2%).8, 24 These conclusions contrast with a much higher proportion of stroke survivors who will require pharmacological treatment; the percentage of stroke survivors who will be recommended antihypertensive treatment will increase from 29.9% to 49.8%. The societal gain if the new guidelines were fully implemented would be reflected in the lower stroke recurrence rate, as suggested by prior studies that have found that every reduction of 1 mm Hg of BP was associated with a 4% reduction in stroke recurrence.19 Although there may be several barriers to implementing these new guidelines, financial burden is arguably one of the most important hurdles to putting these guidelines into practice. Subsequent simulation analyses from the SPRINT do suggest that intensive BP control would be cost‐effective in the mid‐ and long‐term.25 Subsequent evaluations of the level of adherence to the new guidelines among stroke survivors as well as short‐ and long‐term economic cost analyses are needed.

Limitations

This study has limitations. The diagnosis of stroke was by self‐report. Despite the lack of validation data on self‐reported diagnosis of stroke specifically conducted by NHANES, the use of self‐report in stroke epidemiology studies, including in the United States, has been shown to have a sensitivity and specificity ranging from 78% to 96% and 96% to 98%, respectively.26, 27, 28, 29 Furthermore, we were not able to provide estimates by stroke subtypes. The current study relies on BP obtained at a single visit, unlike the recommended average of multiple BP measurements by the JNC7 and ACC/AHA guidelines. Despite these potential limitations, our study has major strengths, including the rigorous, validated, standardized, and consistent methods for collecting data in NHANES each year and nationwide reach.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings suggest that implementing the ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines will result in significant increase in the proportion of stroke survivors with hypertension, recommended pharmacological treatment, and above BP target. Our results call for preemptive actions to successfully implement the new guidelines in stroke survivors.

Author Contributions

Lekoubou: Study concept and design, data interpretation, and critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. Bishu: Statistical analysis, data interpretation, and critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. Ovbiagele: Study concept and design, critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, and study supervision.

Disclosures

None.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008548 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008548.)

References

- 1. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Després JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER III, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB; American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lackland DT, Roccella EJ, Deutsch AF, Fornage M, George MG, Howard G, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Schwamm LH, Smith EE, Towfighi A; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology . Factors influencing the decline in stroke mortality: a statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:315–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, Bravata DM, Chimowitz MI, Ezekowitz MD, Fang MC, Fisher M, Furie KL, Heck DV, Johnston SC, Kasner SE, Kittner SJ, Mitchell PH, Rich MW, Richardson D, Schwamm LH, Wilson JA; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease . Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2160–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cherry DK, Woodwell DA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2000 summary. Adv Data. 2002;328:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Katsanos AH, Filippatou A, Manios E, Deftereos S, Parissis J, Frogoudaki A, Vrettou AR, Ikonomidis I, Pikilidou M, Kargiotis O, Voumvourakis K, Alexandrov AW, Alexandrov AV, Tsivgoulis G. Blood pressure reduction and secondary stroke prevention: a systematic review and metaregression analysis of randomized clinical trials. Hypertension. 2017;69:171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, Roccella EJ; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee . Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, O'Brien E, Dobson JE, Dahlöf B, Sever PS, Poulter NR. Prognostic significance of visit‐to‐visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet. 2010;375:895–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr, Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:1269–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data . http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/surveys.htm. Accessed November 13, 2017.

- 10. National Center for Health Statistics . https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/datalinkage/Public_use_Data_Dictionary_11_17_2015.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2018.

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Questionnaire, Examination Protocol, and Laboratory Protocol. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes_questionnaires.htm. Accessed November 13, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12. StataCorp . Stata: Release 14. Statistical Software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13. SPS3 Study Group , Benavente OR, Coffey CS, Conwit R, Hart RG, McClure LA, Pearce LA, Pergola PE, Szychowski JM. Blood‐pressure targets in patients with recent lacunar stroke: the SPS3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;382:507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. The ACCORD Study Group . Effects of intensive blood‐pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. SPRINT Research Group , Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, Snyder JK, Sink KM. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood‐pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deijle IA, Van Schaik SM, Van Wegen EE, Weinstein HC, Kwakkel G, Van den Berg‐Vos RM. Lifestyle interventions to prevent cardiovascular events after stroke and transient ischemic attack: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Stroke. 2017;48:174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lennon O, Galvin R, Smith K, Doody C, Blake C. Lifestyle interventions for secondary disease prevention in stroke and transient ischaemic attack: a systematic review. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:1026–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lawrence M, Pringle J, Kerr S, Booth J, Govan L, Roberts NJ. Multimodal secondary prevention behavioral interventions for TIA and stroke: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta‐analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R; Prospective Studies Collaboration . Age‐specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta‐analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heran BS, Chen JM, Ebrahim S, Moxham T, Oldridge N, Rees K, Thompson DR, Taylor RS. Exercise‐based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;6:CD001800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Towfighi A, Markovic D, Ovbiagele B. Impact of a healthy lifestyle on all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality after stroke in the USA. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:146–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kotchen TA. Historical trends and milestones in hypertension research: a model of the process of translational research. Hypertension. 2011;58:522–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Muntner P, Carey RM, Gidding S, Jones DW, Taler SJ, Wright JT Jr, Whelton PK. Potential U.S. population impact of the 2017 ACC/AHA high blood pressure guideline. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:109–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bress AP, Bellows BK, King JB, Hess R, Beddhu S, Zhang Z, Berlowitz DR, Conroy MB, Fine L, Oparil S, Morisky DE, Kazis LE, Ruiz‐Negrón N, Powell J, Tamariz L, Whittle J, Wright JT Jr, Supiano MA, Cheung AK, Weintraub WS, Moran AE; SPRINT Research Group . Cost‐effectiveness of intensive versus standard blood‐pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:745–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Engstad T, Bønaa KH, Viitanen M. Validity of self‐reported stroke: the Tromsø Study. Stroke. 2000;31:1602–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. O'Mahony PG, Dobson R, Rodgers H, James OF, Thomson RG. Validation of a population screening questionnaire to assess prevalence of stroke. Stroke. 1995;26:1334–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Simpson CF, Boyd CM, Carlson MC, Griswold ME, Guralnik JM, Fried LP. Agreement between self‐report of disease diagnoses and medical record validation in disabled older women: factors that modify agreement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:123–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Okura Y, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen S, Rodeheffer HJ. Agreement between self‐report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and stroke, but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1096–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]