Multiple methods are employed to reveal the effects of mercury(II) ions and mechanisms of dysfunction caused by them on isolated mitochondria.

Multiple methods are employed to reveal the effects of mercury(II) ions and mechanisms of dysfunction caused by them on isolated mitochondria.

Abstract

Mercury (Hg) is a toxic environmental pollutant that exerts its cytotoxic effects as cations by targeting mitochondria. In our work, we determined different mitochondrial toxicity factors using specific substrates and inhibitors following the addition of Hg2+ to the mitochondria isolated from Wistar rat liver in vitro. We found that Hg2+ induced marked changes in the mitochondrial ultrastructure accompanied by mitochondrial swelling, mitochondrial membrane potential collapse, mitochondrial membrane fluidity increase and Cytochrome c release. Additionally, the effects of Hg2+ on heat production of mitochondria were investigated using microcalorimetry; simultaneously, the effects on mitochondrial respiration were determined by Clark oxygen-electric methods. Microcalorimetry could provide detailed kinetic and thermodynamic information which demonstrated that Hg2+ had some biotoxicity effect on mitochondria. The inhibition of energy metabolic activities suggested that high concentrations of Hg2+ could induce mitochondrial ATP depletion under MPT and mitochondrial respiration inhibition. These results help us learn more about the toxicity of Hg2+ at the subcellular level.

Introduction

Heavy metals are extremely dangerous substances among pollutants due to their stability and toxicity even at very low concentrations. Mercury (Hg) is one of the most toxic environmental contaminants, and exists in a wide variety of physical and chemical states. Mercury occurs as elemental mercury and as inorganic and organic compounds (mercury vapor, mercury liquid, mercury salts, short-chain alkylmercury compounds, alkoxyalkylmercury compounds, and phenylmercury compounds), all with different toxicological properties.1 The toxic effects of Hg vapor and Hg compounds are a consequence of mercury accumulation in the central nervous system, whereas the kidney and liver are affected by micromercurialism.2,3

Mitochondria play crucial roles in different cellular functions such as energy generation, redox state homeostasis, cell proliferation, and cell death due to environmental stresses.4,5 In addition, mitochondrial dysfunction is implicated in cancers, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases.6–9 Due to their biological features, mitochondria are extremely vulnerable to exogenous pollutants, including highly toxic heavy metals.10 Mercury toxicity consequences include the potential to induce DNA damage and disrupt cellular processes, like mitochondrial functions.11,12 The exposure to Hg2+ is shown to cause the following in rat cell line PC21: impairment of cell viability, intracellular ROS formation, deregulation of intracellular antioxidants, and oxidative damage associated with mitochondrial dysfunction (respiratory inhibition and mitochondrial membrane potential collapse).13,14 In spite of the known widespread toxicity of mercury, mechanism(s) underlying the mercury-induced mitochondrial dysfunction are still poorly elucidated.

Based on these observations, we attempted to clarify the influence of Hg2+ on isolated rat mitochondria from the aspect of mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) and energy metabolism. Using the characteristic signals of MPT pore (MPTP) opening, mitochondrial swelling was monitored by UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy, while the changes of mitochondrial transmembrane potential (Δѱ) and mitochondrial membrane fluidity were detected by fluorescence spectroscopy. We postulated that Hg-induced MPT was the reason for the high level of Cytochrome c being released from the mitochondrial matrix. Cytochrome c, an essential player in the respiratory chain that shuttles electrons from complex III to complex IV, can inhibit the electron transfer process and thus lower the ATP levels.15 From the aspect of energy metabolism, the thermogenic curve of isolated rat mitochondria and the effect of Hg2+ on it were studied by the means of microcalorimetry. Additionally, mitochondria are the main sites for cellular aerobic respiration and ATP synthesis.16 So, we analyzed the influence of Hg2+ on the mitochondrial respiratory function and mitochondrial ATP level.

Materials and methods

Animals and chemicals

Female Wistar rats (about 150 g) were purchased from the Hubei Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Wuhan, China), and housed in ventilated micro-isolator cages with free access to water and food in a constant temperature room (22 ± 2 °C). Animals were handled according to the Guidelines of the China Animal Welfare Legislation, as approved by the Committee on Ethics in the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the College of Life Sciences, Wuhan University.

Bovine serum albumin (BSA, 66.435 kDa), mercury chloride (HgCl2), oligomycin, rotenone, valinomycin, HEPES, sucrose, EDTA and ethylene glycol bis(2-aminoethyl) tetraacetic acid (EGTA) were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO); sodium pyruvate was obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd, (China). All other reagents were of analytical reagent grade, and all solutions were prepared with aseptic double-distilled water.

Isolation of mitochondria

Liver mitochondria were isolated according to the literature.17 Briefly, fresh rat liver samples were quickly removed, placed in a beaker and washed in ice-cold homogenization buffer: twice with solution A (220 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, 2 mM Tris-HCl and 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). Then the liver tissue (about 2 g) was finely minced and suspended in 40 mL of solution A and 0.4% (w/v) BSA was added. After chilling in ice-cold water, the suspension was homogenized with a glass handheld homogenizer and then centrifuged at 3000g for 4 min. The supernatant was carefully decanted and centrifuged at 17 500g for 5 min. The pellet was diluted by gently resuspending in solution B (220 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl and 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) and subjected to further centrifugation at 17 500g for 5 min twice. The final mitochondrial pellet was preserved in solution C (220 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose and 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). All of the above steps were strictly operated at 0–4 °C and the isolated mitochondria were used within 3 h in order to guarantee high-quality fresh mitochondrial preparation. Mitochondrial protein concentrations were determined by the Biuret method. BSA was used as a standard for protein measurement.18,19

Mitochondrial ultrastructure

Mitochondria (1 mg protein per mL) were incubated with or without different concentrations of Hg2+, fixed for 30 min at 4 °C using 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide and dehydrated.20 A JEM-100CX transmission electron microscope (TEM) was used to observe the basic mitochondrial ultrastructure.

Mitochondrial swelling

Mitochondrial swelling was measured by monitoring the decrease of absorbance at 540 nm over 600 s at 25 °C.20 Mitochondria (0.5 mg protein per mL) were suspended in 0.2 mL of MAB solution (200 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris-MOPS, 20 μM EGTA-Tris, 5 mM succinate, 2 μM rotenone, and 3 μg mL–1 oligomycin, pH 7.4) and incubated with different concentrations of Hg2+. Spectra were recorded using a microplate reader (Victor X5, PerkinElmer, America).

Mitochondrial inner membrane H+ and K+ permeabilization

Mitochondrial inner membrane (MIM) permeabilization of H+ or K+ was respectively detected in potassium acetate and potassium nitrate media.21 Mitochondria (0.5 mg protein per mL) were suspended in a potassium acetate buffer, which contained 135 mM KAc, 0.1 mM EGTA, 5 mM HEPES, 0.2 mM EDTA, 2 μM rotenone and 1 μg ml–1 valinomycin, pH 7.4. 1 μg ml–1 valinomycin was used to permeabilize the MIM to K+ and KNO3 was used alternatively in the potassium nitrate medium.22 The instrument and experimental parameters were the same as described above, in “Mitochondrial swelling”.

Mitochondrial membrane potential

For mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ) measurements, a cationic lipophilic fluorescent dye rhodamine 123 (Rh123) which can permeate the inner membrane and accumulate in the polarized mitochondrial matrix was used.23 Isolated mitochondria (0.5 mg protein per mL) were suspended in MAB solution (0.2 mL) as described above. The Rh123 fluorescence intensity was continuously visualized and monitored using a microplate reader (Victor X5, PerkinElmer, America) set at 488 nm excitation and 535 nm emission wavelengths at 25 °C.

Mitochondrial membrane fluidity

Mitochondrial membrane fluidity was measured by the fluorescence anisotropy changes of HP-labeled mitochondria.24 HP was a kind of membrane lipid-bound probe molecule which interacted with polar and solvent-accessible regions of the lipid bilayer and with protein sites in biological membranes.25 Mitochondria (0.5 mg protein per mL) were suspended in buffer MAB (2 mL) with HP (3 μM) added and incubated for 1 min before measuring. The values of steady-state anisotropy (r) of HP-labeled mitochondria could be obtained at λex = 520 nm and λem = 626 nm using a fluorescence spectrometer (LS55, PerkinElmer, America) at 25 °C. The anisotropy (r) is defined by the following equation:26

| r = (IVV – GIVH)/(IVV + 2GIVH) | 1 |

Steady-state fluorescence anisotropy values were obtained by measurements of IVV and IVH, i.e., the fluorescence intensities polarized parallel and perpendicular to the vertical plane of polarization of the excitation beam, respectively. G = IVV/IHV is the correction factor for instrumental artifacts.

Mitochondrial Cytochrome c release

Mitochondrial samples were incubated with different concentrations of Hg2+ for 15 min. The suspension was then centrifuged for 5 min at 17 500g. The supernatant was analyzed using a Cyt c ELISA Kit (Shanghai Hua Yi Bio Technology Co. Ltd, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol.24 The 96-well plates were precoated with anti-Cyt c polyclonal antibody and 50 μL samples were added and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Then a HRP–antibody conjugate was added and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. A chromogenic agent was added to the wells and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min sequentially. The wells were washed three times with washing buffer before each of the above steps. Finally, 50 μL of stop solution were added. The absorption at 450 nm was recorded using a microplate reader (Victor X5, PerkinElmer, America).

Mitochondrial respiratory activities

The mitochondrial respiratory rate was assessed by the consumption of oxygen using a Clark-type electrode and the Oxygraph software (Hatchtech, Dorchester, UK).27 Mitochondria (1 mg protein per mL) were added into a closed glass chamber equipped with magnetic stirring at 25 °C. The chamber was filled with respiration buffer MRB (1 mL, containing 250 mM sucrose, 20 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 5 mM K2HPO4, 2 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM rotenone, pH 7.4). Different mitochondrial respiratory rates were initiated by adding 5 mM succinate (state 4); 5 mM succinate and 100 μM ADP (state 3) and 5 mM succinate and 30 μM DNP (uncoupled state).

Mitochondrial microcalorimetry determination

The metabolic thermogenic curves of isolated mitochondria were obtained by using a TAM air isothermal calorimeter (TA, America) by the ampoule method.27,28 In the experiment, each sealed ampoule contained 2 mL of sample (5 mg protein per mL energized mitochondria suspension with different concentrations of Hg2+) and 23 mL of air, which provided sufficient oxygen for the mitochondria metabolism. The ampoules with samples were put into the microcalorimetric system and the temperature was controlled at 30 °C. Meanwhile, a computer was used to record the power–time curves and the heat output of mitochondria continuously. In this experiment, we used pyruvate as energy source and buffer (220 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl and 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) to supply the osmotic pressure.

Mitochondrial ATP content

The isolated mitochondrial ATP content was assessed by a luciferin–luciferase reaction with a commercially available ATP Assay Kit (Beyotime, S0026).24 The luminescence intensity from the reaction was proportional to the ATP concentration in the assay solution and was measured using a microplate reader at 25 °C (Victor X5, PerkinElmer, America).

Results

Mitochondrial ultrastructure

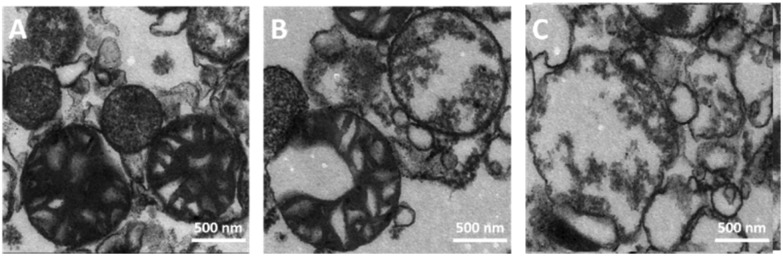

The mitochondrial ultrastructure with and without treatment of Hg2+ was investigated by TEM. Fig. 1A shows that the normal mitochondria isolated from rat liver maintained their integrity, with the ultrastructure containing a well-defined outer membrane, narrow intermembrane space, and dense cristae. As shown in Fig. 1B and C, the Hg2+-treated mitochondria were obviously swollen with decreased matrix electron density, clustered cristae, and enlarged inner membrane space, which was the most direct evidence of MPT occurrence. Furthermore, high concentrations of Hg2+ caused a severe matrix swelling, with the outer membrane damaged (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. Mitochondrial ultrastructure was ruptured by the addition of 0 (A), 10 (B) and 40 (C) μM Hg2+.

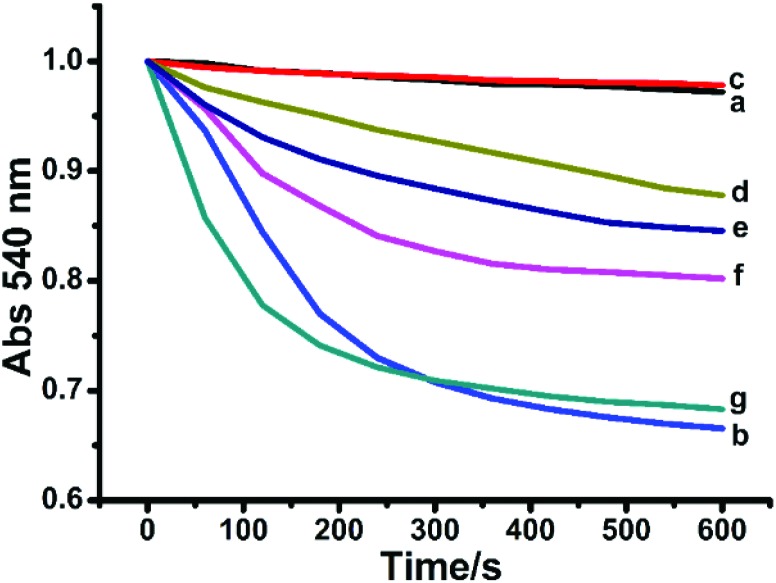

Mitochondrial swelling

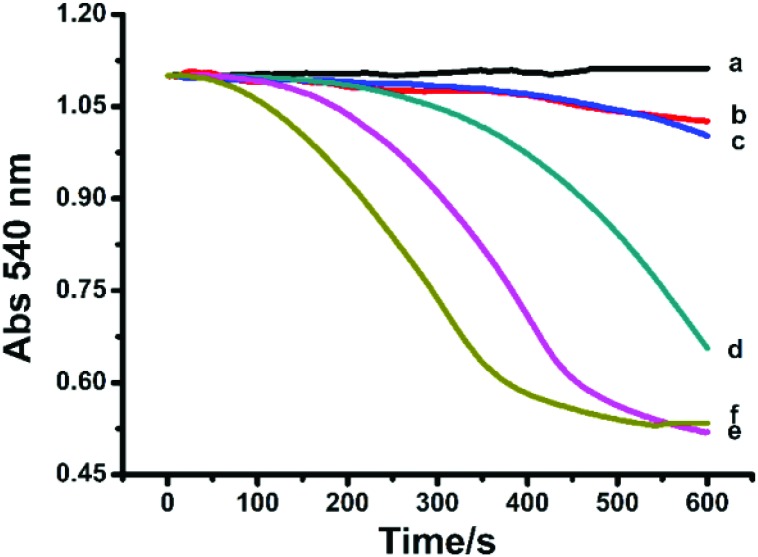

Mitochondrial swelling as an indicator of membrane permeability was monitored with the change of absorbance at 540 nm.20,29 As shown in Fig. 2, compared to the control, Hg2+ (5–40 μM) induced mitochondrial swelling with a dose-dependent effect. The spectroscopic measurements were in accordance with the TEM observation on the mitochondrial swelling.

Fig. 2. Swelling of succinate-energized rat liver mitochondria with Hg2+. c (Hg2+)/μM (a–f): 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 40.

MIM permeabilization to H+ and K+

The effects of Hg2+ on the permeabilization of the MIM to H+ and K+ were evaluated by the swelling of non-respiring mitochondria suspended in potassium acetate and potassium nitrate media, respectively.17 HAc can cross the MIM, then enter into the mitochondrial matrix, and dissociate into the acetate anion and H+, producing a proton gradient. The H+ gradient across the mitochondrial membrane was disrupted by the addition of Hg2+. The effect of Hg2+ on the permeabilization of the MIM to H+ displays a dose-dependent nature (Fig. 3A). The ability of Hg2+ to permeabilize K+ was tested by swelling of non-respiring mitochondria suspended in KNO3. The mitochondrial inner membrane freely permeates nitrate, but swelling is observed only under conditions of K+ permeabilization. Fig. 3B shows that Hg2+ enhanced the permeabilization of the MIM to K+ with a dose-dependent effect.

Fig. 3. Effect of Hg2+ on permeabilization to H+ (A) and K+ (B) by the MIM. c (Hg2+)/μM (a–f): 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 40.

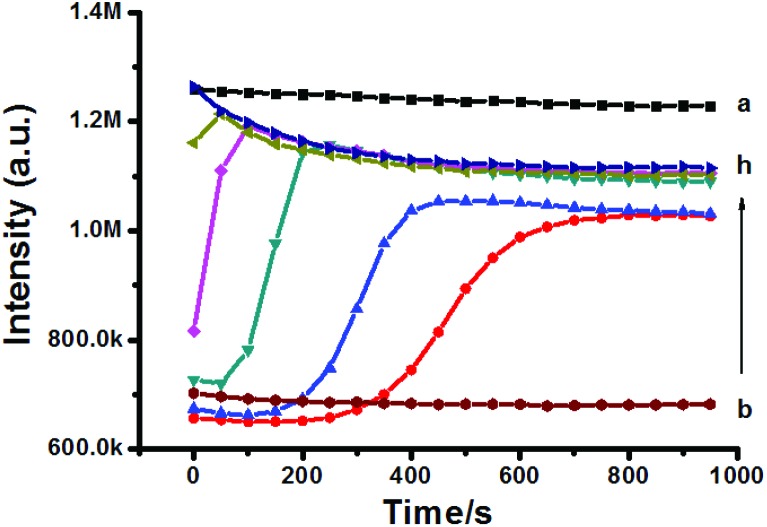

Mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ)

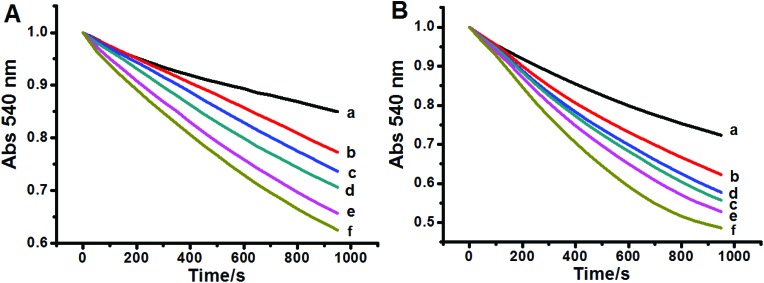

Due to its cationic property, Rh123 can accumulate in the MIM; thus trapping inside the sub-cellular organelle leads to fluorescence quenching. Once the Δѱ decreased, Rh123 was released into the medium and its fluorescence intensity increased subsequently. As shown in Fig. 4, mitochondrial Δψ significantly decreased with different concentrations of Hg2+.

Fig. 4. Effect of Hg2+ on Δψ collapse. The intensity of Rh123 in the buffer MAB without mitochondria is shown as trace a. c (Hg2+)/μM (b–h): 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 40.

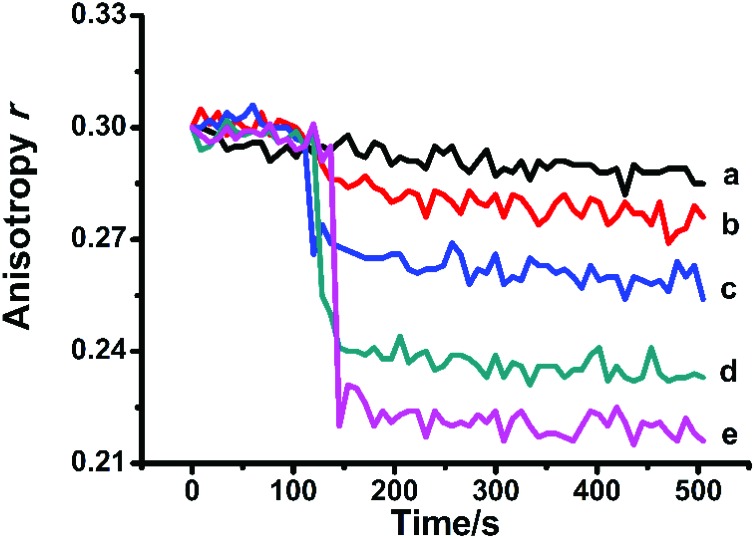

Mitochondrial membrane fluidity

Mitochondrial MPT was accompanied by fluidity changes of mitochondrial membranes.25,30 The membrane fluidity changes can be evaluated by the changes of fluorescence anisotropy (r) of HP. As shown in Fig. 5, the anisotropy was continuously monitored. The addition of Hg2+ caused an obvious decrease of the anisotropy of HP, which can be attributed to the increase of Brownian motion or energy transfer between identical chromophores.

Fig. 5. Hg2+ increased the fluidity of the MIM. c (Hg2+)/μM (a–e): 0, 5, 10, 20, and 40.

Mitochondrial Cytochrome c release

Cytochrome c is believed to reside solely in the mitochondrial intermembrane crista spaces under normal physiological conditions.13 The opening of the MPTP caused mitochondrial swelling and released the apoptosis-initiating factor and Cytochrome c from the intermembrane space to the cytosol, which activates the caspase family of proteases, the primary trigger leading to the onset of apoptosis.31Table 1 shows that the release of Cytochrome c increased from isolated mitochondria incubated with Hg2+ during the incubation period.

Table 1. Effect of Hg2+ on the Cytochrome c release of liver mitochondria.

| Hg2+ (μM) | OD (450 nm) | Cytochrome c (nM) |

| 0 | 0.212 | 20 ± 2 |

| 10 | 0.255 | 23 ± 3 |

| 20 | 0.276 | 25 ± 5 |

| 40 | 0.281 | 26 ± 5* |

Mitochondrial respiration

The effect of Hg2+ on the mitochondrial respiratory rate is shown in Table 2. In the absence of Hg2+, the low respiration rate value of state 4 indicated an intact MIM and the high rate value of state 3 indicated that the respiratory chain and ATP synthase were intact.32 The respiratory control ratio (RCR, the respiration rate ratio of state 3 to state 4) was another important parameter that reflected the coupling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation.33 After exposure to Hg2+, state 4, state 3 and DNP-uncoupled respiration rates as well as the RCR were inhibited (Table 2). This demonstrated that Hg2+ might damage the mitochondrial respiratory chain.

Table 2. The effect of Hg2+ on the respiration of isolated mitochondria.

| Hg2+ (μM) | State 4 | State 3 | RCR | DNP |

| 0 | 12.51 ± 0.82 | 35.97 ± 1.28 | 2.89 ± 0.29 | 33.11 ± 2.26 |

| 5 | 12.05 ± 0.93 | 34.27 ± 1.55 | 2.87 ± 0.35 | 28.98 ± 1.36 |

| 10 | 11.06 ± 1.01 | 32.68 ± 1.96 | 2.81 ± 0.22 | 24.57 ± 1.42 |

| 15 | 10.35 ± 1.26* | 29.17 ± 1.73* | 2.75 ± 0.24* | 17.21 ± 1.57 |

| 20 | 9.64 ± 0.62** | 24.33 ± 1.11** | 2.69 ± 0.16** | 14.65 ± 0.86* |

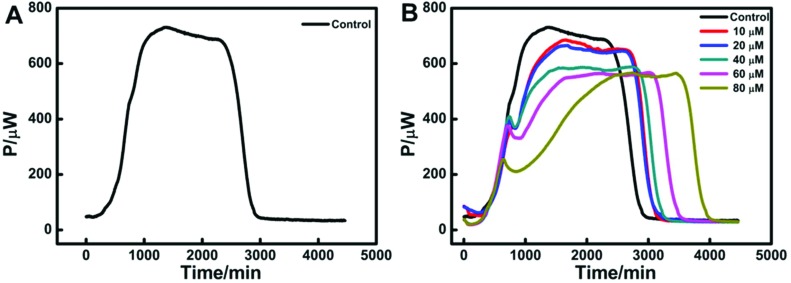

Metabolic thermogenic curves of isolated mitochondria

The heat flux curve of isolated mitochondria energized by pyruvate revealed mitochondrial metabolism.27 The thermogenic curve could be divided into four phases: lag phase, activity recovery phase, stationary increase phase and decline phase.28 As shown in Fig. 6A, mitochondria had a slow process of recovery to adapt to a new physiological environment in the first 500 min. An obvious activity recovery phase suggested that the isolated mitochondria had a good degree of metabolic activity. After the short activity recovery, mitochondria had a stationary increase phase that lasted about 1000 min. Then mitochondria had a decline phase when the environment nutrition exhausted. Fig. 6B displays the corresponding metabolic curves of isolated mitochondria with different concentrations of Hg2+ and the shape is similar to that of the control. However, the stationary increase phase had an obvious effect with the addition of Hg2+. Moreover, the lag phase, the activity recovery phase and the decline phase were difficult to separate with the increase in Hg2+-concentration.

Fig. 6. (A) Thermogenic curve of isolated rat mitochondria energized by pyruvate without Hg2+; (B) the heat flux curves of energized mitochondria metabolism at different concentrations of Hg2+.

Thermokinetic parameters of mitochondria

To study the effect of Hg2+ on mitochondria, the heat production processes were analyzed by thermokinetics. As shown in Fig. 6B, if the heat output power is P0 at time 0, and Pt at time t, then the thermokinetic equation is:

| Pt = P0 exp (kt) or lnPt = lnP0 + kt | 2 |

The growth rate constant (k1) can be obtained from the activity recovery phase as described above in eqn (2), and the same applies to the decline rate constant (k2). And, other parameters were obtained from Fig. 6B directly, which included the maximum power output (Pm), the maximum power output time (tm) and the total heat output (Q) as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Values of the metabolism parameters of isolated mitochondria.

| Hg2+ (μM) | k 1 (10–3 min–1) | R 1 | k 2 (10–3 min–1) | R 2 | P m (μW) | t m (min) | Q (J) |

| 0 | 1.11 | 0.9975 | –1.65 | 0.9951 | 731.4 | 1366 | 89.2 |

| 10 | 0.97 | 0.9954 | –2.37 | 0.9994 | 685.5 | 1666 | 89.5 |

| 20 | 0.73 | 0.9979 | –2.18 | 0.9988 | 665.7 | 1689 | 88.4 |

| 40 | 0.55 | 0.9939 | –2.00 | 0.9946 | 588.8 | 2741 | 84.6 |

| 60 | 0.39 | 0.9981 | –2.82 | 0.9962 | 567.3 | 3027 | 86.8 |

| 80 | 0.19 | 0.9926 | –1.83 | 0.9957 | 565.4 | 3448 | 88.3 |

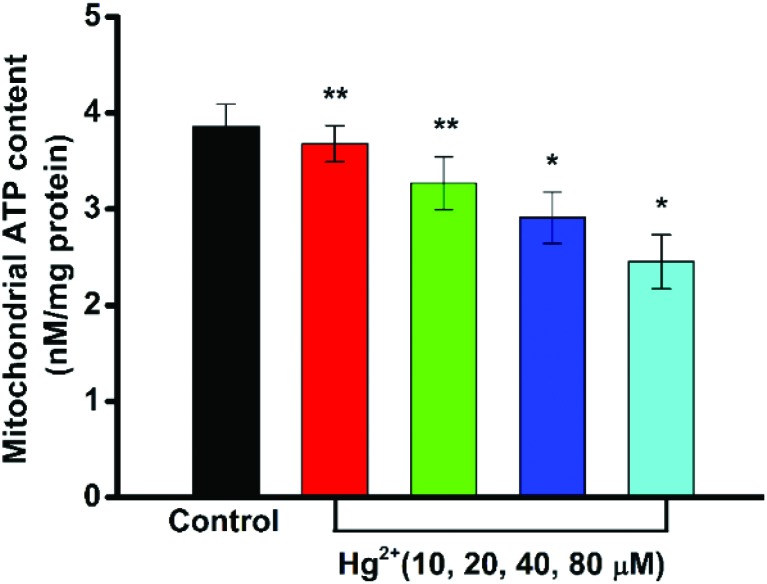

Mitochondrial ATP content

The mitochondrion is at the core of cellular energy metabolism, being the site of maximum ATP generation through oxidative phosphorylation.34 The determination of ATP levels can provide an indirect measure of the mitochondrial function. As shown in Fig. 7, the mitochondrial ATP levels were significantly decreased by Hg2+ in a concentration-dependent manner.

Fig. 7. Effect of Hg2+ on the content of mitochondrial ATP. Values are represented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 of the deviation from the control group.

Discussion

Mitochondrial dysfunction has been implicated in a multitude of diseases and pathological conditions – the organelles that are essential for life can also be major players in contributing to cell apoptosis and necrosis. The MPTP can be defined as a voltage-dependent, nonselective high-conductance inner mitochondrial membrane channel of unknown molecular structure, which allows solutes up to 1500 Da to pass freely in and out of mitochondria.35 The MPTP opens under conditions of calcium overload; the opening is greatly enhanced by adenine nucleotide depletion, elevated phosphate, and oxidative stress. The opening of the MPT pore in vivo produces ATP pool exhaustion, disturbance of Ca2+ homeostasis, and efflux of various apoptotic factors from mitochondria. Mitochondrial swelling is a hallmark of mitochondrial dysfunction and is one of the most important indicators of the MPTP opening.36 Hg2+ (5–40 μM) induced a dose-dependent mitochondrial swelling (Fig. 1), indicating that the mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization function was disturbed and mitochondrial matrix concentration changes may be caused by MPTP opening. In most cases, MPTP opening was accompanied by the change of membrane fluidity related to the increase of membrane permeability.26,30

The MIM is freely permeable to only oxygen, water and some proteins. The swelling of non-energized mitochondria in the KAc medium was a valinomycin-dependent process and was only possible when the MIM was additionally permeabilized by valinomycin.37 Acetate anions and H+ go through the MIM and then dissociate in the matrix, producing a proton gradient. The proton gradient is important for ATP synthesis and the activity of the respiratory chain enzyme complex.38 Meanwhile, most of the oxygen consumed is derived from H+ leakage across the mitochondrial membrane during mitochondrial respiration state 4.39 As shown in Fig. 2A, Hg2+ could destroy this proton gradient to induce the opening of the inner MPTP, so that many proteins could influx into the intermembrane space and others could influx into the matrix consequently.

Similarly, the mitochondrial osmotic swelling of non-energized mitochondria in the potassium nitrate medium was used to evaluate the passive potassium permeability of the MIM. Due to the unique permeability of the MIM to nitrate (NO3–), optimal osmotic swelling only occurred under conditions of K+ permeability.40 As shown in Fig. 2B, Hg2+ enhanced the K+ conductance of the MIM with a dose-dependent effect. Intracellular K+ is a predominant ion that acts as a repressor of apoptotic effectors, and the depletion of K+ may serve as a key step in apoptosis.41 The K+ influx induces the decrease of Δѱ, which explains the MPT and, thus, mitochondrial swelling, disruption of the outer membrane, and Cytochrome c release.42 The increase in K+ permeability may accompany an increased permeability to protons. In light of this, our data on H+ and K+ permeability (Fig. 2) were consistent with the data on mitochondrial swelling (Fig. 1), Δѱ (Fig. 3), and Cytochrome c (Table 1) in this article.

The Δѱ is the driving force for ATP production. Loss of Δѱ would impair the cell's energy metabolism. At higher concentrations of Hg2+, the Δѱ collapsed in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3). Once mitochondria underwent MPT, cations could move through the inner membrane, and thus the Δѱ changed.

HP accumulates mainly in the polar, solvent-accessible regions of the lipid bilayer and the protein regions of the MIM.21 When HP is excited with polarized light, the resulting fluorescence is also polarized. Since the main cause of fluorescence depolarization is rotational diffusion of the fluorophore during the excited lifetime, fluorescence polarization measurements can be used to determine the rotational mobility of the fluorophore, which reflects the fluidity of the membrane. A high polarization value indicates low membrane fluidity or high structural order.43 A change in the Δѱ on a biological membrane could alter the dynamic behavior of the mitochondrial membrane, which was consistent with our results of membrane fluidity changes. With the addition of Hg2+, the membrane fluidity decreased as probed by HP (Fig. 4), indicating that the inner membrane protein regions involved in MPTP formation were changed.

In the tested concentration range, Hg2+ induced the release of Cytochrome c (Table 1), which was supposed to be one of the proteins triggering apoptosis, from mitochondria to the cytosol. Summarizing the above results, we concluded that Hg2+ could trigger the MPTP opening and then induce abnormal changes in the mitochondrial ultrastructure (swelling and membrane fluidity) and functions (membrane permeability, Δѱ). These events had inherent links with the damage of the respiratory chain, such as the inhibition of respiration and energy metabolism.

The power–time curves display the process of mitochondrial metabolic activity which demonstrated that isolated energized mitochondria sustained the energy metabolism appropriately (Fig. 6A). As shown in Fig. 6B, we found some alterations of the mitochondrial metabolic thermogenic curves with the addition of Hg2+. To be more specific, we analysed the relationship between the thermogenic parameters and the concentrations of Hg2+ respectively. We could find that the Hg2+-exposure changes of the stationary increase rate constant (k1), the maximum power output time (tm) and the maximum power output (Pm) decreased with the addition of Hg2+. These findings clearly demonstrated that Hg2+ induced MPTP opening could disturb the energy metabolic processes at the same time.

As is known, the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and oxidative phosphorylation represent the major components of aerobic respiration44 and the respiration electron transport chain located on the MIM for the energy currency production.45 There was a reduction in respiration at high respiration rates such as coupled to the ATP level (state 3) at the tested concentration (Table 2). ATP is required for the apoptotic process and MPTP opening which later leads to massive ATP depletion and necrosis.46 The stimulation for state 4 respiration and inhibition for uncoupler-stimulated (DNP) respiration indicated that Hg2+ might have coupling effects on mitochondria which was confirmed to induce a decrease in the intracellular ATP content in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 7). This reduction of the mitochondrial ATP content indicated that the mitochondrial dysfunction resulted from the decrease in the ability of oxidative phosphorylation. Meanwhile, the decreased respiration rates of state 4 demonstrated that Hg2+ might damage the MIM and increase the membrane permeability, which could be proved by the results of mitochondrial swelling experiments (Fig. 1).

To investigate the mechanism of MPT induced by Hg2+, the functions of MPT inhibitors (DTT, EDTA, CsA, ADP and RR) were studied for their influence on mitochondrial swelling in the presence of 40 μM Hg2+ (Fig. 8). DTT, a thiol reagent and an antioxidant, could protect the S-sites of the inner membrane components.47 Due to its active –SH, DTT could obviously prevent the Hg2+-induced swelling. EDTA inhibited the Hg2+-induced swelling indicating its possible role in preventing MPT by chelating metal ions.48 CsA is a well-established inhibitor of MPT and was able to close the MPTP by erecting a tight combination with the protein Cyp D, which was located in the MPTP and was important for controlling the opening of the MPTP.49

Fig. 8. Protective effects of DTT, EDTA, CsA, ADP and RR on the mitochondrial swelling caused by 40 μM Hg2+. Control (a), 40 μM Hg2+ (b), 40 μM Hg2+ and 50 μM DTT (c), 40 μM Hg2+ and 40 μM EDTA (d), 40 μM Hg2+ and 20 μM CsA (e), 40 μM Hg2+ and 250 μM ADP (f), and 40 μM Hg2+ and 20 μM RR (g).

ADP could modulate MPT by controlling the conformation of ANT, which was considered as another component of MPTP.50 ADP also demonstrated significant protective effects on Hg2+-induced mitochondrial swelling, indicating that Hg2+ was able to change the ANT conformation when inducing MPT. Ca2+ was known to cause MPT by accumulating in the mitochondrial matrix and inducing MMP loss.51 In the presence of RR, Ca2+ is unable to permeate into the matrix and the swelling is prevented. In our study, RR hardly prevented Hg2+-induced mitochondrial swelling, showing that Hg2+ was unable to influence Ca2+ regulation. Considering the protective effects of these reagents, we concluded that the mechanism of Hg2+-induced mitochondrial dysfunction was complex and partial free Hg2+ was able to open the MPTP in a Ca2+-independent manner.

Conclusions

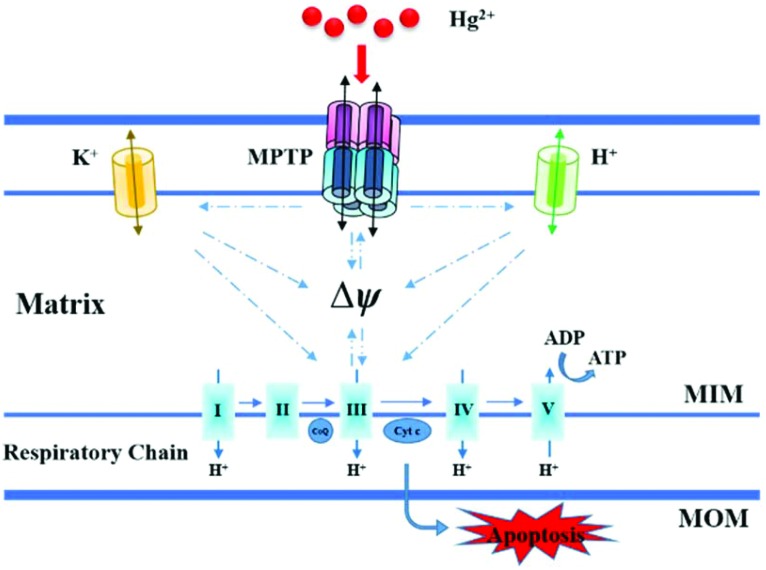

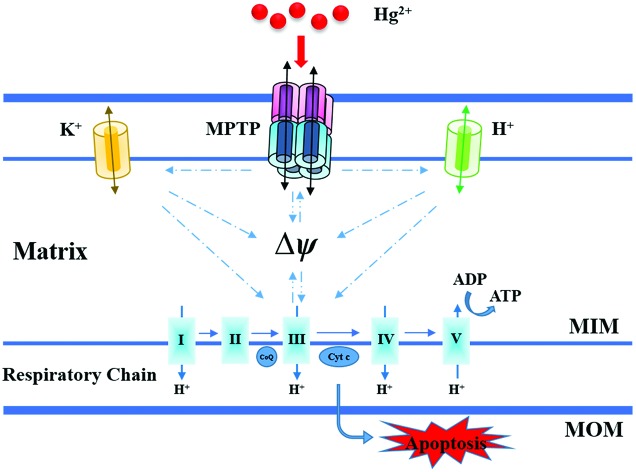

Our results collected from isolated mitochondria showed that Hg2+ damaged the mitochondrial ultrastructure, induced mitochondrial swelling, and promoted membrane fluidity. Moreover, it was observed that Hg2+ increased MIM permeabilization to H+/K+, collapsed the Δѱ, and caused Cytochrome c release indicating the occurrence of MPT, which is proposed and elucidated briefly in Fig. 9. The inhibition of energy metabolic activities suggested that high concentrations of Hg2+ could induce mitochondrial ATP depletion under MPT and mitochondrial respiration inhibition. The findings may contribute to understand the complex, varied patterns of Hg2+ toxicity and minimize the Hg2+-induced mitochondrial damage.

Fig. 9. Proposed mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction induced by Hg2+.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21573168, 21303126, 21463008, and 21763005).

References

- Tchounwou P. B., Yedjou C. G., Patlolla A. K., Sutton D. J. EXS. 2012;101:133–164. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7643-8340-4_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzi G., LaPorta C. A. M. Toxicol. 2008;244:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson T. W., Magos L., Myers G. J. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:1731–1737. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R. E., Williams M. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012;342:598–607. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.192104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes P. S., Yoon Y., Robotham J. L., Anders M. W., Sheu S. S. Am. J. Physiol.: Cell Physiol. 2004;287:817–833. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esterhuizen K., van F. H., Louw R. Mitochondrion. 2017;35:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed M. Z., Tabassum H., Parvez S. Protoplasma. 2017;254:33–42. doi: 10.1007/s00709-015-0930-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra F., Arbini A. A., Moro L. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2017;1858:686–699. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier F. P., Boneh A., Dennett X., Chow C. W., Cleary M. A., Thorburn D. R. Neurology. 2002;59:1406–1411. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000033795.17156.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh S., Goldstein A., Koenig M. K., Scaglia F., Enns G. M., Saneto R., Anselm I., Cohen B. H., Falk M. J., Greene C., Gropman A. L. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. Genomics. 2015;17:689–701. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roubicek D. A., Souza-Pinto N. C. Toxicol. 2017;391:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt L. H., Luz A. L., Cao X., Maurer L. L., Blawas A. M., Aballay A., Pan W. K. Y., Meyer J. N. DNA Repair. 2017;52:31–48. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belyaeva E. A., Sokolova T. V., Emelyanova L. V., Zakharova I. O. Sci. World J. 2012;2012:1–14. doi: 10.1100/2012/136063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesci S., Trombetti F., Pirini M., Ventrella V., Pagliarani A. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2016;260:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein J. C., Waterhouse N. J., Juin P., Evan G. I., Green D. R. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:156–162. doi: 10.1038/35004029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoitzing H., Johnston I. G., Jones N. S. BioEssays. 2015;37:687–700. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Dong J. X., Wu C., Li X. Y., Chen J., Zhang H., Liu Y. J. Membr. Biol. 2017;250:195–204. doi: 10.1007/s00232-017-9947-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang X., Wu C., Zhang B. R., Gao T., Zhao J., Ma L., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. Chemosphere. 2017;184:1108–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. R., Jia Z. G., Chen J. H. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:9160–9168. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b06768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. Y., Gao J. L., Gao T., Dong P., Ma L., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016;301:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong P., Li J. H., Xu S. P., Wu X. J., Xiang X., Yang Q. Q., Jin J. C., Liu Y., Jiang F. L. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016;308:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X. Y., Chen X. Y., Liu Y. J., Zhong H. M., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:29865. doi: 10.1038/srep29865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X. Y., Liu Y. J., Chen K., Jiang F. L., Hu Y. J., Liu D., Liu Y., Ge Y. S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;143:1090–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Liu J. Y., Dong J. X., Xiao Q., Zhao J., Jiang F. L. Toxicol. Res. 2017;6:822–830. doi: 10.1039/c7tx00204a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricchelli F., Jori G., Gobbo S., Tronchin M. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991;1065:42–48. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90008-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricchelli F., Gobbo S., Moreno G., Salet C. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9295–9300. doi: 10.1021/bi9900828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L., Gao T., He H., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. Toxicol. Res. 2017;6:621–630. doi: 10.1039/c7tx00079k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Ma L., Xiang X., Guo Q. L., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. Chemosphere. 2016;153:414–418. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.03.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., He H., Xiang C., Fan X. Y., Yang L. Y., Yuan L., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. Toxicol. Sci. 2017;161:431–442. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfx218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricchelli F., Beghetto C., Gobbo S., Tognon G., Moretto V., Crisma M. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003;410:155–160. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00667-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nageswara R. M., Marschall S. R. Circ. Res. 2007;100:460–473. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M. P. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1504:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace K. B., Starkov A. A. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2000;40:353–388. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes P. S., Yoon Y., Robotham J. L., Anders M. W., Sheu S. S. Am. J. Physiol.: Cell Physiol. 2004;287:817–833. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton M. Biochem. J. 1999;341:233–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santo-Domingo J., Demaurex N. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1797:907–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poburko D., Santo-Domingo J., Demaurex N. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:11672–11684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.159962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoszka J. E., Waymire K. G., Levy S. E., Sligh J. E., Cai J. Y., Jones D. P., MacGregor G. R., Wallace D. C. Nature. 2004;427:461–465. doi: 10.1038/nature02229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosetti F., Baracca A., Lenaz G., Solaini G. FEBS Lett. 2004;563:161–164. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00294-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlid K. D. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1275:123–126. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(96)00061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarczyk P., Barker G. D., Halestrap A. P. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2008;1777:540–548. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönfeld P., Gerke S., Bohnensack R., Wojtczak L. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2003;1604:125–133. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(03)00043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricchelli F., Jori G., Gobbo S., Nikolov P., Petronilli V. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005;37:1858–1868. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adlam V. J., Harrison J. C., Porteous C. M., James A. M., Smith R. A. J., Murphy M. P., Sammut I. A. FASEB J. 2005;19:1088–1095. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3718com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollihue J. L., Rabchevsky A. G. Mitochondrion. 2017;35:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi Y., Shimizu S., Tsujimoto Y. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1835–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingenberg M. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2008;1778:1978–2021. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Kuroda S., Tada M., Houkin K., Iwasaki Y., Abe H. Brain Res. 2003;960:62–70. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03767-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halestrap A. P. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2010;38:841–860. doi: 10.1042/BST0380841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarana C., Sripetchwandee J., Sanit J., Chattipakorn S., Chattipakorn N. Arch. Med. Res. 2012;42:333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoratti M., Szabò I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1241:139–176. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(95)00003-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]