Abstract

Background

Mental health problems are common among individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and difficulties with emotion regulation processes may underlie these issues. Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is considered an efficacious treatment for anxiety in children with ASD. Additional research is needed to examine the efficacy of a transdiagnostic treatment approach, whereby the same treatment can be applied to multiple emotional problems, beyond solely anxiety. The purpose of the present study was to examine the efficacy of a manualized and individually delivered 10‐session, transdiagnostic CBT intervention, aimed at improving emotion regulation and mental health difficulties in children with ASD.

Methods

Sixty‐eight children (M age = 9.75, SD = 1.27) and their parents participated in the study, randomly allocated to either a treatment immediate (n = 35) or waitlist control condition (n = 33) (ISRCTN #67079741). Parent‐, child‐, and clinician‐reported measures of emotion regulation and mental health were administered at baseline, postintervention/postwaitlist, and at 10‐week follow‐up.

Results

Children in the treatment immediate condition demonstrated significant improvements on measures of emotion regulation (i.e., emotionality, emotion regulation abilities with social skills) and aspects of psychopathology (i.e., a composite measure of internalizing and externalizing symptoms, adaptive behaviors) compared to those in the waitlist control condition. Treatment gains were maintained at follow‐up.

Conclusions

This study is the first transdiagnostic CBT efficacy trial for children with ASD. Additional investigations are needed to further establish its relative efficacy compared to more traditional models of CBT for children with ASD and other neurodevelopmental conditions.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, cognitive behavior therapy, emotion regulation, treatment, mental health

Introduction

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often experience considerable mental health problems, in addition to the core symptoms of atypical social communication and behavioral inflexibility (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Between 30% and 50% of children and adolescents with ASD without intellectual disability meet criteria for at least two psychiatric conditions (Simonoff et al., 2008), and 50%–85% have clinically significant emotional difficulties (Totsika, Hastings, Emerson, Lancaster, & Berridge, 2011). While the most common set of emotional problems revolves around anxiety, there is considerable overlap in both internalizing and externalizing symptom presentation (Hurtig et al., 2009).

Impairments in emotion regulation (ER) may partly explain this interrelated symptomatology (Mazefsky & White, 2014). Emotion regulation is best described as ‘the extrinsic and intrinsic processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions, especially their intensive and temporal features, to accomplish one's goals’ (Thompson, 1994, pp. 27–28). These processes help children adapt and modulate the strength of their emotional responses within a range of situations, and conversely, impairments in ER are associated with both internalizing and externalizing problems (Eisenberg et al., 2001). Recent reviews suggest that ER impairments may function in a transdiagnostic manner, being shared across and maintaining multiple emotional disorders (Aldao, Nolen‐Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010). For example, in the non‐ASD literature, impaired ER processes (e.g., poor emotional awareness, avoidance, excessive rumination) are associated with later onset of anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and eating disorders (Broderick & Korteland, 2004; Kranzler et al., 2016; Nolen‐Hoeksema, Stice, Wade, & Bohon, 2007). Furthermore, in a systematic review of 67 treatment studies that measured change in ER and in symptoms of psychopathology (of anxiety, depression, substance use, eating disorders and borderline personality disorder), improvement in ER was reported in the majority that documented improvements in psychopathology (Sloan et al., 2017).

Likewise, transdiagnostic cognitive behavior therapy (tCBT) has focused on improving ER to address an array of emotional problems in children and adults without ASD (Ehrenreich‐May & Chu, 2013; Newby, McKinnon, Kuyken, Gilbody, & Dalgleish, 2015). Transdiagnostic interventions apply the same underlying treatment principles across mental disorders without tailoring the protocol to specific diagnoses, making it possible to address different emotional responses elicited from the same cues and potentially increasing treatment efficiency (McEvoy, Nathan, & Norton, 2009). With appropriate modifications, tCBT may also be applicable to a variety of developmental levels (Ehrenreich‐May et al., 2017). Recent randomized trials of group‐ and individually‐ provided tCBT with adolescents without ASD have demonstrated improvements on clinician‐rated adolescent anxiety, overall symptom severity, and in the number of primary and secondary psychiatric diagnoses, when compared to waitlist (Chu et al., 2016; Ehrenreich‐May et al., 2017). The few randomized trials that compare the use of tCBT to diagnostic‐specific CBT indicate equivalence between treatment types in adults without ASD in addressing symptoms of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, and panic disorder (Pearl & Norton, 2017). Authors suggest that a benefit of tCBT could be in reducing the need for multiple treatments for common disorders that often present with comorbidities (Reinholt & Krogh, 2014; Titov et al., 2015), functioning as a complement to, rather than a replacement of, well‐established disorder‐specific approaches (Clark, 2009).

Cognitive behavior therapy is considered an efficacious treatment for anxiety in children with ASD. A recent systematic review of 24 CBT studies targeting affective problems in individuals with ASD indicated medium effect sizes for informant and clinician report (Weston, Hodgekins, & Langdon, 2016). Of those studies, 19 were focused on anxiety, 17 involved children and adolescents, 16 were group based, and 14 were randomized controlled trials (with six comparing CBT to treatment as usual or an active treatment condition). Notably, across studies, results revealed a lack of self‐reported change for youth. Other CBT systematic reviews have suggested that this lack of child‐reported change may be because youth with ASD may struggle to express the range of symptoms they experience, due to the affective and communication difficulties of the disorder (Kreslins, Robertson, & Melville, 2015).

Few studies have applied CBT to address emotional problems other than anxiety, for children with ASD. Sofronoff, Attwood, Hinton, and Levin (2007) randomly assigned 10–14‐year‐old children with ASD and anger difficulties to either six weekly 2‐hour sessions of group CBT or waitlist, while parents attended a concurrent psychoeducation group. Post intervention, treatment was associated with greater reductions in parent‐reported child anger, confidence in managing child behavior, and greater child‐reported knowledge of strategies to defuse a hypothetical, anger‐provoking situation. Another pilot study targeted ER skills in 5–7‐year‐olds with ASD using a group‐based, parent‐involved CBT program, and suggested improvements in parent self‐efficacy, child outbursts, and child‐reported strategies compared to a randomly assigned waitlist control group (Scarpa & Reyes, 2011). In adults with ASD, mindfulness‐based group cognitive therapy has been shown to result in reduced anxiety, depression, and rumination using a waitlist RCT design (Spek, van Ham, & Nyklíček, 2013), and group‐based CBT has been associated with reduced depression and stress using a quasi‐experimental design (Mcgillivray & Evert, 2014).

More research is needed to determine how CBT may be used to address multiple emotional problems in children with ASD. To date, no randomized trial of tCBT exists for this population, whereby the same intervention is applied equally to address multiple emotional disorders, including anxiety disorders, mood, or problems with externalizing issues. The current study presents results from a randomized waitlist‐controlled trial of the Secret Agent Society: Operation Regulation (SAS:OR; Beaumont, 2013), a manualized tCBT intervention delivered individually to children with ASD and their primary caregiver. Previous research with SAS:OR has indicated a high level of clinical utility, operationalized as child, parent, and therapist satisfaction, as well as treatment adherence (i.e., attendance, attrition, engagement, homework completion), and treatment fidelity (Thomson, Burnham Riosa, & Weiss, 2015). Compared to children on the waitlist, children receiving therapy were expected to demonstrate improved parent and child‐rated ER (primary outcomes) and reduced mental health problems via clinician‐, parent‐, and child‐report (secondary outcomes) at postintervention, with maintenance of gains between postintervention and follow‐up.

Methods

Study design

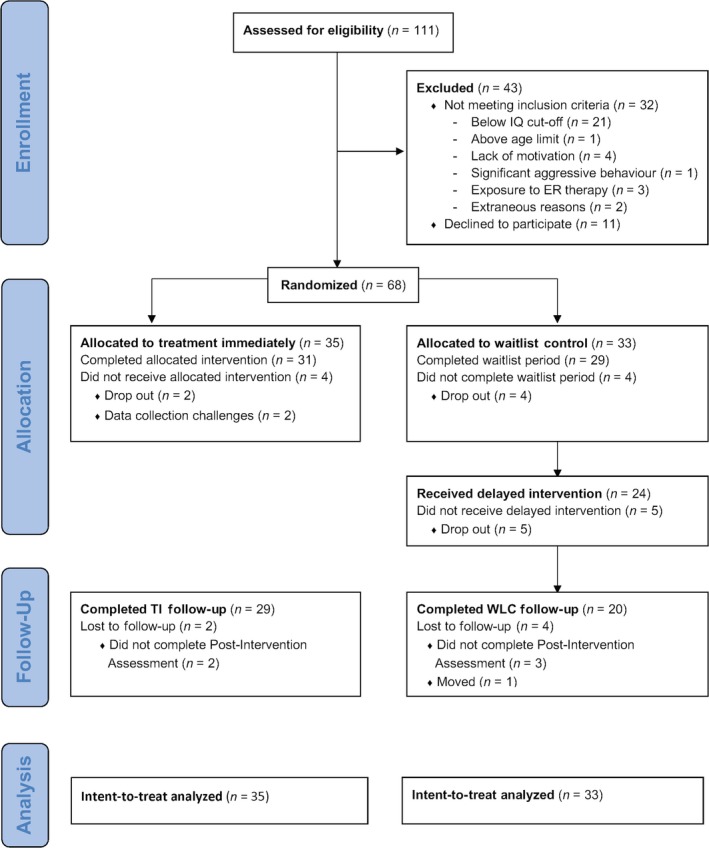

Families were recruited from January 2013 to April 2016 through local autism service e‐newsletters, website postings, and referrals from community healthcare providers. Interested participants completed a telephone intake and a brief online survey, which included the Social Communication Questionnaire – Lifetime Version (SCQ; Rutter, Bailey, & Lord, 2003) and the Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS‐2; Constantino & Gruber, 2012). Participants came to the university where informed consent and assent was obtained; children completed a readiness for therapy interview and the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence – Second Edition (WASI‐II; Wechsler, 2011), and parents completed the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule – Parent Version (ADIS‐P; Silverman & Albano, 1996). Families then returned for a second visit within 2 weeks to complete primary and secondary outcome measures; the ADIS‐P was only readministered at this point if more than 2 weeks had elapsed since the first in‐person assessment. After completing primary and secondary outcome measures (baseline), families were randomly assigned to either a treatment immediate (TI) or a 10–14‐week waitlist (WL) period. Study coordinators randomized participants to TI or WL conditions using an Internet‐based randomization system (Urbaniak & Plous, 2015), which was stratified based on child gender. Treatment allocation was determined at the start of the study, and revealed to coordinators, research assistants, and families only after completing the baseline assessment. As shown in the participant flow figure (Figure 1), for the TI group, all outcome measures were assessed at baseline (Time 1), 10–14 weeks postbaseline (Time 2), and at 10‐week follow‐up (Time 3). Waitlist participants took part in an initial baseline assessment (Time 1) followed by a second assessment of all outcome measures 10–14 weeks postbaseline (Time 2). After the Time 2 (postbaseline) assessment, WL participants received the intervention and were subsequently assessed post‐treatment (Time 3), followed by a 10‐week follow‐up assessment of all outcome measures (Time 4). Participants completed the intervention in 10–14 weeks. An assessment of clinical severity and improvement was completed by an author who was not aware of participants’ treatment condition. See Appendix S1 for the CONSORT checklist.

Figure 1.

SAS:OR CONSORT flow diagram

Ethical considerations

The University Research Ethics Board approved this study. No participants experienced physical harm during participation in the trial. This study was registered with the ISRCTN registry (ISRCTN67079741).

Primary outcomes

Table S1 provides descriptive statistics and internal consistencies of each measure.

Child current self‐reported ER in three emotional states was assessed using the Children's Emotion Management Scales (CEM; Zeman, Cassano, Suveg, & Shipman, 2010): Sadness (12 items), Anger (11 items), and Worry (10 items). Each scale is divided into three subscales: Inhibition (e.g., ‘I hold my worried feelings in’), Dysregulation (e.g., ‘I say mean things to others when I am mad’), and Coping (e.g., ‘I can stop myself from losing my temper’). Children completed the questionnaires alongside a research assistant to ensure that they understood the items. Each item is rated on a 3‐point scale (1 = ‘hardly ever’ to 3 = ‘often’), with higher mean scores reflecting greater inhibition, dysregulation, or coping.

Child current knowledge of ER strategies was assessed using the Dylan is Being Teased (Dylan; Attwood, 2004a) and James and the Maths Test (James; Attwood, 2004b) open‐ended tasks. These activities have been used with children with ASD to assess a child's ability to generate appropriate ER strategies in a hypothetical situation, with the James story depicting a child who is anxious about a test, and the Dylan scenario describing a child coping with anger and bullying (Beaumont, Rotolone, & Sofronoff, 2015; Beaumont & Sofronoff, 2008; Sofronoff, Attwood, & Hinton, 2005). After being read each situation, children were asked to provide strategies to lessen James’ anxiety and Dylan's anger. Verbal responses were recorded verbatim, and the resulting score is the sum of appropriate strategies named for each scenario. Higher scores reflect greater knowledge of appropriate strategies for coping with anger or anxiety.

Parent report of child ER ability was assessed using the 24‐item Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC; Shields & Cicchetti, 1997), which asks about current typical frequency of child behaviors on a 4‐point scale (1 = ‘rarely/never’ to 4 = ‘almost always’). The Lability/Negativity subscale measures reactivity, mood swings, intense emotions, and negative emotional expression, with high scores indicating higher levels of negative affect. The Emotion Regulation subscale measures empathy, understanding of emotions, and appropriate displays of emotion, with higher scores indicating more positive displays. The ERC has been successfully used in several studies assessing the typical ways children with autism manage their experiences, as reported by their parents (e.g., Berkovits, Eisenhower, & Blacher, 2017; Scarpa & Reyes, 2011).

Child ER was also assessed via the Emotion Regulation and Social Skills Questionnaire (ERSSQ‐P; Beaumont & Sofronoff, 2008), a 27‐item parent‐report measure developed for parents of youth with ASD that is used to examine ER processes and social skills, asking parents to describe the child's behavior at the present moment. Emotion regulation ability is assessed using a 5‐point scale (0 = ‘never’ to 4 = ‘always’), with higher scores reflecting greater skills. Overall mean scores are then calculated. The ERSSQ‐P has been found to have high internal consistency and concurrent validity in parents of children with ASD (Butterworth et al., 2014; Einfeld et al., 2017).

Secondary outcomes

The Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition – Parent Rating Scales (BASC‐2; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004) is a parent‐report questionnaire about child psychopathology, used previously to study emotional and behavioral problems in youth with ASD (Volker et al., 2010), and found to have high internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and moderate to high concurrent validity (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). The current study used the Externalizing Problems, Internalizing Problems, Adaptive Skills, and Behavioral Symptoms Index composites. The BASC‐2 asks parents to reference the ‘last several months’; however, at each appointment following baseline, parents were asked with reference to the time since the last appointment.

The ADIS‐P (Silverman & Albano, 1996) is a semistructured diagnostic interview conducted with parents by a clinician to assess symptoms, onset, and severity of a range of mood, anxiety, and behavioral disorders in children. Clinicians generate severity ratings from 0 to 8 for any disorder where children meet criteria, with higher scores indicating more severe presentation. The ADIS‐P has been used in multiple CBT trials for children with ASD (e.g., Storch et al., 2015; Wood et al., 2009). Trained graduate student research assistants and postdoctoral fellows administered the ADIS‐P, under the supervision of a clinical psychologist. Similar to its use in many other CBT studies with children with ASD (McNally Keehn, Lincoln, Brown, & Chavira, 2013; Reaven, Blakeley‐Smith, Culhane‐Shelburne, & Hepburn, 2012; Storch et al., 2013; Ung et al., 2014; Wood et al., 2009), the ADIS‐P was not specifically adapted for children with ASD. While the measure may reflect an overestimation of clinical diagnoses (Mazefsky & White, 2014), it was applied equally for those in our two randomization groups. At baseline, parents were asked about symptomatology over a time span corresponding to DSM‐IV diagnostic criteria (i.e., ‘Has your child's problem of feeling scared or worried when he/she is not with you been going on for at least four weeks?’), with some questions asking if a behavior has ever occurred (i.e., ‘Has your child ever told you, or have you ever noticed, that this happened to him/her?’). At all subsequent assessment time points, items indicating a particular time frame, or whether symptoms have ever been present, were asked as specified in the protocol; questions about symptom severity and interference are asked in reference to the time since the last appointment. Clinician judgments were based on whether the child was exhibiting current (not lifetime) symptoms at a severity and interference level that meet criteria for each diagnosis.

An evaluator assessed child psychopathology severity and posttreatment improvement using the Clinical Global Impression Scale – Severity and Improvement (CGI‐S and CGI‐I; Guy, 1976). The evaluator was the senior author, not involved with direct treatment provision or data collection, nor aware of child treatment condition allocation. Anonymized copies of the ADIS‐P interviews and BASC‐2 score summaries were reviewed to determine the CGI‐S score at each time point (from 0 ‘no illness’ to 6 ‘serious illness’). The CGI‐I score was obtained by documenting observed changes on the ADIS‐P and BASC‐2 (from 0 ‘very much improved’ to 6 ‘very much worse’) in reference to the preceding time point results. The evaluator was provided with the output from the BASC‐2 report and a narrative summary page from the ADIS‐P without identifying information, linked only by ID number and the assessment time point (i.e., Time 1, Time 2, Time 3). These precautions were taken to ensure the evaluator could not discern the treatment condition from the time point but could still report on potential improvement (CGI‐I) from the earlier time point. The CGI‐S and CGI‐I are commonly used methods of measuring psychopathology in CBT trials for children with ASD, and similar to the current study, are based on data provided by parents (e.g., Kerns et al., 2016; Reaven et al., 2012).

Participants

Intent‐to‐treat participants included 68 children with ASD and their parents from the Greater Toronto Area. Children were predominantly male (88.2%, n = 60), 8–12 years of age (M = 9.75, SD = 1.27), and parents were mostly mothers (83.8%, n = 57), with a mean age of 43.9 years (SD = 4.16). Participants met the following inclusion criteria: (a) an ASD diagnosis from a qualified clinician through parental provision of written documentation, (b) scores above the cutoff on the Social Communication Questionnaire – Lifetime Version (SCQ cutoff >14; Rutter et al., 2003) or the Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS‐2 Total T‐Score cutoff >59; Constantino & Gruber, 2012); (c) 8–12 years of age; (d) parent report of child difficulties managing emotions (by describing significant changes in the child's behavior when they feel sad/upset/angry/anxious; or by indicating the child tries to hurt self, others, or breaks things; or by listing and rating several situations in which the child commonly becomes very anxious or angry); and (e) a willingness to attend research and therapy appointments. If a child did not meet clinical cutoffs on the SCQ and SRS‐2, the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord, Rutter, DiLavore, & Risi, 2008) was used to confirm ASD (n = 2). At baseline, we assessed children's motivation to participate in the intervention using a 9‐point Likert scale, ranging from 0 = ‘Not at all’ to 8 = ‘Very, very much’, on the following three questions: ‘how much do you want to be part of the program?,’ ‘how much do you want to change?,’ and ‘how hard you are willing to work?’ Overall, children showed a moderate level of interest (M = 4.74, Median = 4.67, SD = 2.01), ranging from 0 to 8. While we did not require a clinical cutoff for emotion regulation problems, 88% of children had at‐risk or clinically significant emotional problems at baseline (as indicated by at least at‐risk levels on at least one of the following BASC‐2 subscales: Aggression, Conduct Problems, Anxiety, Depression, Anger Control, Emotional Self‐Control, or Negative Emotionality), and 93% met criteria for at least one anxiety, mood or disruptive disorder on the ADIS‐P.

Families were excluded if: (a) the child demonstrated below average intellectual functioning, based on the two‐subtest Full Scale IQ score (<79; FSIQ‐2; Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning) of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence – Second Edition (WASI‐II; Wechsler, 2011), (b) parents reported aggressive or self‐injurious child behaviors that were a serious safety concern, (c) the child was currently receiving behavior therapy or CBT, or (d) the child was receiving any other intervention to address ER. As shown in Figure 1, a total of 32 participants were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria, and 11 participants declined to participate.

Intervention

Secret Agent Society: Operation Regulation. The SAS:OR intervention targets ER in children with ASD through 10 sessions of manualized, individual tCBT (Beaumont, 2013). The original Secret Agent Society (Beaumont et al., 2015) employed a group‐based spy‐themed curriculum to address social skills in children with ASD. SAS:OR employs the same spy theme, and some of the same materials and activities (e.g., use of select computer games, use of the emotion education activities, use of code cards), but omits the social skills curriculum. Instead, SAS:OR includes specific activities meant to improve emotion regulation (e.g., planned systematic exposure, subjective units of distress scaling, mindfulness and acceptance activities, etc.). Sessions involve education, in vivo practice of skills, planning for challenges in the home and at school, and positive reinforcement. Materials include a child and parent workbook, teacher handouts to update the school on each session, a home‐school diary to increase generalization and maintenance of target behavior change in both school and home settings, a computer game, and a high degree of visual material. Systematic exposures, emotion education, and regulation strategies are applied across multiple emotions with a focus on learning and practicing various adaptive ER processes. Sessions progress from teaching basic skills, such as recognizing and labeling emotions in self and others (i.e., emotion education) to more complex skills, such as adjusting responses to difficult emotions using relaxation strategies (response modulation), combined with planned systematic exposure to increasingly distressing family‐informed situations. A parent is involved throughout each session; they follow along in their own manual, provide support to the child and therapist, and help the child transfer skills to school and home environments. A detailed description of the sessions is provided in the feasibility trial (Thomson et al., 2015).

Fidelity

Trained clinical psychology graduate students and postdoctoral fellows provided the therapy. Training involved one full‐day session with a didactic lesson covering material from the manuals, as well as viewing videos of sessions with role‐plays and feedback. Therapists then participated in videotaped mock sessions that were evaluated to ensure a high level of readiness. Treatment fidelity to the manual was monitored by therapist completion of session‐specific checklists of all required activities, as is common in treatment trials (Garbacz, Brown, Spee, Polo, & Budd, 2014). Weekly supervision was provided by the lead clinical psychologist or by postdoctoral fellows (overseen by the clinical psychologist) to address clinical concerns and to review therapy recordings to address fidelity and implementation.

Data analysis plan

Primary and secondary outcomes were examined first using intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis, followed by treatment completer analyses, as is common practice to provide results of those who complete the trial as well as those who have missing data as a result of dropping out (Luby, Lenze, & Tillman, 2012; Meiser‐Stedman et al., 2017; Wood et al., 2009). A sample size of N = 60 was expected to be sufficient to detect large effects, given past studies of CBT interventions for children with ASD (e.g., Reaven et al., 2012), also supported by power analysis (GPower 3.1; with an alpha of .05 and power of 0.8; Cohen, 1988). ITT analyses were conducted using multiple imputation (MI) with SAS 9.4 (Mackinnon, 2010). Multiple imputation is a more rigorous way of handling missing data than simple imputation methods (Li, Stuart, & Allison, 2015), such as last observation carried forward (LOCF), which imputes missing data based on a single value and introduces greater standardized bias than MI (Barnes, Lindborg, & Seaman, 2006; Newgard & Lewis, 2015). With MI, complete datasets are imputed using all available information from the observed data, which are then separately analyzed using standard statistical methods (e.g., ANCOVA, multiple regression). Results from these analyses are then pooled to provide an overall estimate of effects (Sterne et al., 2009). To handle missing data for noncompleters (n = 8; TI = 4, WL = 4), 10 datasets were imputed using an MI regression method under the assumption that data were missing at random, which was confirmed by analyzing missing data patterns. Baseline scores for the variable of interest, and for BASC‐Externalizing,1 were included in the MI procedure. The PROC MIANALYZE statement was run to analyze the imputed datasets using ANCOVA, with treatment condition as the between subject variable, and baseline scores of each variable and BASC‐Externalizing scores as covariates. The overall pooled regression estimate of effects is represented as t‐scores to indicate the unique contribution of the treatment condition to the overall model. Effect sizes were calculated and reported as Cohen's d (Cohen, 1988).

Treatment completer data were analyzed using analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) for each variable, with treatment condition as the between subject variable, and baseline scores of each variable and BASC‐Externalizing scores as covariates (Wood et al., 2015). For children in the TI condition, follow‐up data were collected at 10 weeks posttreatment (those in WL condition received the treatment and did not have a follow‐up time point) and were compared to posttreatment scores using paired samples t‐tests to determine if there was any change in scores over this period. Treatment completer and follow‐up analyses were conducted using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Effect sizes were calculated by transforming partial‐eta squared values to Cohen's d (Cohen, 1988).

Results

Pretreatment comparisons

Child and family characteristics and demographics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics and characteristics by treatment group at randomization

| TI (n = 35) M (SD) or % | WL (n = 33) M (SD) or % | t (df) or χ2 | p‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Child | 9.63 (1.26) | 9.88 (1.29) | −0.81 (66) | .42 |

| Parent | 43.23 (4.54) | 44.65 (3.61) | −1.39 (64) | .17 |

| FSIQ‐2 | 104.23 (14.88) | 101.23 (14.34) | 0.83 (64) | .41 |

| SCQ | 21.69 (4.38) | 19.88 (4.35) | 1.71 (66) | .09 |

| SRS‐2 | 73.40 (9.29) | 73.91 (9.77) | −0.22 (66) | .83 |

| Gender | ||||

| Child (female) | 11.4% | 12.1% | 0.01 | .93 |

| Parent (mothers) | 85.7% | 81.8% | 0.19 | .66 |

| Ethnicity | 0.91 | .34 | ||

| White/Caucasian | 76.7% | 84.6% | ||

| Visible minority | 23.3% | 11.5% | ||

| Prefer not to disclose | 0% | 3.8% | ||

| Psychotropic medication use (Yes) | 40.0% | 27.3% | 1.06 | .30 |

| Parent marital status (married) | 85.7% | 84.8% | 0.01 | .92 |

| Parent graduated from college | 77.1% | 72.7% | 0.73 | .39 |

| Family income (CAD before taxes) | 3.73 | .59 | ||

| <$49,999 | 0% | 3% | ||

| $50,000–$99,999 | 17.1% | 9.1% | ||

| $100,000–$149,999 | 14.3% | 18.2% | ||

| $150,000–$199,999 | 22.9% | 12.1% | ||

| $200,000 or more | 11.4% | 18.2% | ||

| Prefer not to disclose | 20.0% | 15.2% | ||

FSIQ‐2, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence Full Scale IQ – 2 subscales; SCQ, Social Communication Questionnaire‐Lifetime Version; SRS‐2, Social Responsiveness Scale, 2nd Edition.

As shown in Table S2, there were no differences in the proportion of children in each group who met criteria for various anxiety, mood, or disruptive disorders. Of the entire sample (N = 68), 80.8% met for at least one anxiety disorder, 75% met for at least one disruptive disorder, and 63% met for both. Independent samples t‐tests revealed no difference in any measure of ER when comparing children with at least one disruptive behavior disorder, one anxiety disorder, or both, to children without (all p's > .10). Mann–Whitney U‐tests revealed no significant difference in Time 1 ER scores, across any measure, for those with at least one anxiety disorder compared to those with none (all p's > .05). Children with at least one disruptive disorder, and with both an anxiety and disruptive disorder, had greater levels of parent‐reported child emotional lability/negativity at baseline compared to those without disruptive disorders (p = .03), with no other significant differences emerging.

Group differences in Time 1 characteristics were compared using chi‐square tests and t‐tests, for the full sample (N = 68) and for completers (n = 60). No differences emerged in any baseline characteristics or outcome measures for the full sample. When analyzing treatment completer data at Time 1, WL participants had significantly higher BASC‐2 Externalizing symptoms (M = 62.38, SD = 11.60) compared to TI participants (M = 56.13, SD = 8.88), t(58) = −2.35, p = .02, d = .61. Due to this Time 1 difference, all subsequent analyses included pretreatment BASC‐2 Externalizing scores as a covariate.

Intervention adherence

Throughout the intervention, therapists followed checklists that outlined all of the session activities. Therapist adherence to the manualized intervention was measured by compliance with these checklists. Six trained observers recorded therapist performance from session videos on the same checklists on a random selection of 20% (n = 62) of the total sessions for the TI group. Overall treatment integrity was calculated as the percentage of items on the checklist that the therapist performed correctly, which was high (85.8%) across sessions (SD = 0.11, Range = 50%–100%). The same trained observers double‐coded 11% (n = 7) of the sessions using the same session checklists and interrater reliability was excellent (intraclass correlation = .77; Cicchetti, 1994). Since we had multiple observers, we reported intraclass correlation as it is used to assess the consistency, or conformity, of measurements made by multiple observers measuring the same quantity (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979), as opposed to kappa, which is used for binary ratings and assumes the same two raters. Following each session, therapists were asked to report on how involved the child was during the session (engagement) and if the child completed the homework assignment from the week prior (adherence). In‐session engagement was rated on a 5‐point scale (1 = ‘completely uninvolved’ to 5 = ‘completely involved’), while homework completion was rated on a 3‐point scale (1 = ‘none’, 2 = ‘partially’, 3 = ‘fully’). Mean scores were calculated by averaging ratings from all sessions for in‐session engagement, and from nine sessions for homework completion (no homework completion score for first session). Overall, children demonstrated good in‐session engagement (M = 4.43, SD = 0.40, Range: 3.40–5.00) and program adherence (M = 2.54, SD = 0.34, Range: 1.75–3.00). While therapists provided the ratings of how engaged children were in each session, we also received child and parent ratings of session activity satisfaction, ranging from ‘poor’ = 1 to ‘high’ = 5 in a visual analog scale using faces to represent valence. Overall, children reported a high degree of satisfaction with activities (M = 3.92, Median = 4.06, SD = 0.71), as did their parents (M = 4.35, Median = 4.44, SD = 0.51). These forms were completed after each session without the therapist in the room and were left in sealed envelopes.

Treatment outcomes

Intention‐to‐treat analyses

Intent‐to‐treat analyses were conducted with the full sample (N = 68) and are presented in Table 2. Results from the MI revealed a significant treatment effect on two primary ER outcome measures: the parent‐report Lability/Negative subscale of the ERC [t(56.38) = −2.16, p = .04], with a medium effect (d = .58), and the ERSSQ [t(52.80) = 3.20, p < .01], with a large effect (d = .79). There were no significant group differences on any of the child‐reported ER measures. The TI group demonstrated significant medium to large effects compared to WL on several secondary outcome measures, including the parent‐report BASC‐2 Adaptive composite [t(54.20) = 2.83, p <.01, d = .71], BASC‐2 Behavioral Symptoms composite [t(57.59) = −2.12, p = .04, d = .52], ADIS‐P Total Diagnoses [t(50.30) = −2.46, p = .02, d = .61], and the clinician judgment CGI‐Severity [t(54.61) = −2.42, p = .02, d = .60], and CGI‐Improvement [t(44.28) = −2.25, p = .03, d = .57]. No differences emerged on the BASC‐2 Externalizing or Internalizing composites. Bias analyses were conducted on missing data, and Mann–Whitney U‐tests confirmed that those who dropped out from the trial were not statistically different from those who completed the intervention in terms of demographics and outcome measures (all p. > 05).

Table 2.

Multiple imputation analysis for intention‐to‐treat (N = 68)

| Outcome | Baseline | Posttreatment/postwaitlista | t | df | p‐value | Cohen's d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TI M (SE) | WL M (SE) | TI M (SE) | WL M (SE) | |||||

| CEM | ||||||||

| Inhibition | 1.79 (0.07) | 1.91 (0.09) | 1.93 (0.08) | 1.84 (0.09) | 0.74 | 47.71 | .46 | .18 |

| Dysregulation | 1.77 (0.07) | 1.79 (0.09) | 1.78 (0.07) | 1.72 (0.07) | 0.61 | 44.74 | .55 | .15 |

| Coping | 1.96 (0.06) | 2.07 (0.09) | 2.10 (0.06) | 2.01 (0.06) | 1.03 | 49.58 | .31 | .26 |

| James and the Maths Test | 1.80 (0.26) | 2.06 (0.36) | 2.78 (0.30) | 2.10 (0.32) | 1.59 | 48.79 | .11 | .38 |

| Dylan is Being Teased | 2.46 (0.29) | 2.25 (0.32) | 2.47 (0.28) | 2.67 (0.30) | −0.49 | 47.62 | .62 | .12 |

| ERC | ||||||||

| LN | 2.44 (0.07) | 2.39 (0.07) | 2.22 (0.04) | 2.37 (0.05) | −2.16 | 56.38 | .04 | .58 |

| ER | 2.82 (0.08) | 2.94 (0.08) | 3.04 (0.05) | 2.97 (0.06) | 0.84 | 53.61 | .40 | .22 |

| ERSSQ | 1.79 (0.07) | 1.90 (0.07) | 2.16 (0.05) | 1.91 (0.06) | 3.20 | 52.80 | <.01 | .79 |

| BASC‐2 | ||||||||

| Externalizing | 57.71 (1.78) | 61.33 (1.96) | 57.74 (0.94) | 58.17 (0.99) | −0.30 | 45.72 | .76 | .08 |

| Internalizing | 60.91 (2.09) | 62.76 (2.32) | 58.10 (1.08) | 60.79 (1.11) | −1.74 | 56.06 | .09 | .43 |

| Adaptive | 36.03 (1.14) | 37.36 (1.36) | 39.84 (0.66) | 37.10 (0.69) | 2.83 | 54.20 | <.01 | .71 |

| BSI | 68.94 (1.80) | 69.63 (1.66) | 65.49 (0.91) | 68.24 (0.92) | −2.12 | 57.59 | .04 | .52 |

| ADIS‐P | ||||||||

| Total diagnoses | 2.63 (0.32) | 2.78 (0.29) | 1.43 (0.18) | 2.06 (0.18) | −2.46 | 50.30 | .02 | .61 |

| Overall severity | 4.03 (0.31) | 3.97 (0.24) | 2.69 (0.32) | 3.48 (0.33) | −1.69 | 51.76 | .10 | .42 |

| CGI | ||||||||

| Severity | 3.83 (0.28) | 4.03 (0.27) | 2.48 (0.24) | 3.32 (0.25) | −2.42 | 54.61 | .02 | .60 |

| Improvement | – | – | 1.68 (0.25) | 2.52 (0.26) | −2.25 | 44.28 | .03 | .57 |

ADIS‐P = Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM‐IV Parent Version; BASC‐2 = Behavior Assessment for Children, 2nd Edition; BSI = Behavioral Symptoms Index; CEM = Children's Emotion Management Scale; CGI = Clinical Global Impressions Scale; LN = Lability/Negativity; ER = Emotion Regulation; ERSSQ = Emotion Regulation and Social Skills Questionnaire.

Adjusted means reported.

Treatment completer analyses

Treatment completer results were consistent with the ITT analyses (see Table S3). The only difference was the ADIS‐P Overall Severity score, which was significant for treatment completers [F(1, 56) = 4.61, p = .04, d = .57]. We also explored the relationship between changes in parent‐reported child emotion regulation, where significant treatment effects were observed, and changes in BASC‐2 index scores, ADIS‐P Overall Severity, and CGI‐Severity, across the total sample of those who completed Time 1 and Time 2 assessment points (with higher scores = greater improvement). Improvement in parent‐reported child emotional lability and emotion regulation skills (on the Emotion Regulation Checklist) was associated with greater improvement in BASC‐2 Behavioral Symptoms (r = .33, p = .01; r = .31, p = .02) and Adaptive Behavior (r = .44, p = .001; r = .28, p = .04), CGI‐Severity (r = .29, p = .03; r = .31, p = .02), and ADIS Overall Severity (r = .36, p = .004; r = .32, p = .01), respectively. Improvements in parent‐reported ERSSQ was associated with improved BASC‐2 Internalizing (r = .30, p = .02), Behavioral Symptoms (r = .30, p = .002), Adaptive Behavior (r = .42, p = .001), CGI‐Severity (r = .33, p = .01), and ADIS‐P Overall Severity (r = .31, p = .02). Upon further examination of the CGI‐I, 74.2% (n = 23) of the TI group was rated as improved, with 35.5% (n = 11) rated as 0 = ‘very much improved’, 6.5% (n = 2) rated as 1 = ‘much improved’, and 32.3% (n = 10) rated as 2 = ‘minimally improved’ (Guastella et al., 2015); 22.6% (n = 7) did not change, and 3.2% worsened (n = 1; 4 = ‘minimally worse’ to 6 = ‘very much worse’) at posttreatment. In the WL group, 31.0% (n = 9) of children were rated as improved, with 10.3% (n = 3) rated as 0 = ‘very much improved’, 10.3% (n = 3) rated as 1 = ‘much improved’ and 10.3% (n = 3) rated as 2 = ‘minimally improved’; 48.3% (n = 14) exhibited no change, and 20.7% (n = 6) worsened during the waiting period. Percentage of children that improved, did not change, or worsened posttreatment significantly differed between groups, X 2 (2, n = 60) = 11.98, p = .003.

Follow‐up

Follow‐up analyses were conducted for the TI group (n = 29) to determine maintenance of scores from posttreatment. Two participants did not return to complete the follow‐up assessment. Paired samples t‐tests indicated, at the 10‐week follow‐up (M = 75.4 days between T2 and T3, SD = 6.67), no significant differences from posttreatment (Table 3). Treatment gains were maintained for the outcomes that significantly changed following treatment. Clinician CGI‐I scores revealed that of the children who showed improvement posttreatment (n = 21), 28.6% (n = 6) showed continued improvement, 42.9 (n = 9) showed no change, and 28.6% (n = 6) worsened. Of the children who showed no change posttreatment, 42.9% (n = 3) improved, and 57.1% (n = 4) did not change. The one child who worsened showed no change 10 weeks following treatment completion. At the follow‐up time point, the mean CGI‐I was 2.76 (Range = 0.00 to 5.00, SD = 1.12), with a score of 3 indicating no change since the postintervention assessment.

Table 3.

Primary and secondary follow‐up outcomes for treatment completers in TI group (n = 29)

| Outcome | Posttreatment M (SD) | Follow‐up M (SD) | t (df) | p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEM | ||||

| Inhibition | 1.90 (.49) | 1.88 (.47) | 0.32 (27) | .75 |

| Dysregulation | 1.77 (.41) | 1.71 (.43) | 0.99 (27) | .33 |

| Coping | 2.08 (.39) | 2.05 (.45) | 0.45 (27) | .66 |

| James and the Maths Test | 2.89 (2.15) | 2.61 (1.64) | 0.96 (27) | .35 |

| Dylan is Being Teased | 2.61 (1.75) | 2.79 (1.85) | −0.66 (27) | .52 |

| ERC | ||||

| LNa | 2.18 (.42) | 2.12 (.41) | 1.08 (28) | .29 |

| ER | 3.09 (.33) | 3.05 (.43) | 0.82 (28) | .42 |

| ERSSQa | 2.21 (.37) | 2.30 (.41) | −1.83 (28) | .08 |

| BASC‐2 | ||||

| Externalizing | 54.79 (9.28) | 54.93 (9.18) | −0.16 (28) | .88 |

| Internalizing | 55.17 (13.10) | 56.24 (12.36) | −0.82 (28) | .42 |

| Adaptivea | 40.52 (6.64) | 41.00 (7.27) | −0.53 (28) | .60 |

| BSIa | 63.76 (10.66) | 63.62 (9.11) | 0.11 (28) | .91 |

| ADIS‐P | ||||

| Total diagnosesa | 1.07 (1.36) | 1.31 (1.26) | −1.57 (28) | .13 |

| Overall severitya | 2.34 (2.22) | 2.76 (2.21) | −1.04 (28) | .31 |

| CGI | ||||

| Severitya | 2.24 (1.68) | 2.07 (1.58) | 0.76 (28) | .46 |

ADIS‐P = Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM‐IV Parent Version; BASC‐2 = Behavior Assessment for Children, 2nd Edition; BSI = Behavioral Symptoms Index; CEM = Children's Emotion Management Scale; CGI = Clinical Global Impressions Scale; LN = Lability/Negativity; ER = Emotion Regulation; ERSSQ = Emotion Regulation and Social Skills Questionnaire.

Significant changes from baseline to posttreatment.

Discussion

This is the first transdiagnostic CBT trial for children with ASD, employing an RCT design. The intervention is unique for children with ASD, as it is based on a unified conceptual theory of underlying ER processes, rather than a traditionally used diagnosis‐specific approach (Ehrenreich‐May et al., 2017). The current trial indicated moderate to strong effects according to informant measures, however, no change was observed on child‐reported measures. Given that some have suggested children's self‐reports of problem‐solving and suppression skills demand a sophistication of metacognitive awareness beyond a child's developmental level (Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Eggum, 2010), our nonsignificant findings are not unexpected; furthermore, they follow a pattern of nonsignificant child‐reported change observed in a recent meta‐analysis of CBT for individuals with ASD (Weston et al., 2016).

In contrast, parents and clinicians reported large effects for changes in broad conceptualizations of child psychopathology. Treatment was associated with improvements on a composite measure of internalizing and externalizing symptoms (BASC‐2 BSI), adaptive skills (BASC‐2 Adaptive Skills), and overall psychiatric symptom severity (ADIS‐P, CGI‐S). The current trial did not indicate more specific changes in externalizing symptoms, and little change in internalizing symptoms was observed, on the BASC‐2. The BSI is a composite of a number of internalizing and externalizing symptoms that are observable by others, including symptoms of aggression, hyperactivity, depression, social withdrawal, and inattention, as well as atypical behaviors (e.g., talks to self, lacks thought control). In contrast, the Adaptive composite reflects success in activities of daily living, adaptability, communication, leadership, school‐related behavior and social skills. Studies comparing BASC‐2 profiles between children with ASD and matched peers without ASD consistently report that the BSI and Adaptive composites have the largest differences relative to peers and compared to the Internalizing and Externalizing composites (Goldin et al,. 2014; Volker et al.,2010). Children in the current study were often not uniform or singular in their difficulties, and in keeping with the transdiagnostic formulation, the intervention curriculum aimed to address this variability by focusing on ER, as opposed to changes in a single targeted observable behavior, such as avoidance of a known stimulus in anxiety‐specific CBT (Reaven et al., 2012). As such, we may have seen greater change in the scores that best capture heterogeneous difficulties, and where children with ASD have the largest difficulties relative to peers. A CBT intervention that focuses on broad content of ER may, therefore, be best suited to broader maladaptive and adaptive outcomes, rather than to specific symptom change. A direct comparison of tCBT to a diagnostic‐specific approach could elucidate potential differential effects.

Parents reported large changes in children's emotionality (ERC Lability subscale) and in their ability to regulate emotions with social behaviors (ERSSQ), but not in empathy or positive affectivity (ERC Emotion Regulation subscale). This corresponds with treatment targets aimed at reducing negative affectivity. We also did not observe a significant increase in child‐reported ER knowledge, despite such changes being found in other trials targeting social skills or emotions (Beaumont & Sofronoff, 2008; Sofronoff et al., 2005). A number of ER models have differentiated the use of implicit, involuntary ER strategies, which may be employed to manage stressors automatically and without awareness, from explicit, voluntary ones that are consciously employed (Gyurak, Gross, & Etkin, 2011). It may be that the current intervention modifies the involuntary processes that are enacted when children are faced with stressors, through the teaching and practice of ER strategies, and systematic exposure. Children with autism may not be aware in situ of the strategies they are employing to manage their emotional reactions (Mazefsky & White, 2014), or may struggle to communicate their thoughts, and thus may appear more regulated without being able to speak about how they achieve this outcome. The lack of change may also be related to measurement challenges. Concordance with parent‐report measures is often low, and validity may vary due to the child's level of self‐awareness, alexithymia, and familiarity or comfort with the measure (Mazefsky, Kao, & Oswald, 2011). It is possible that children became bored with repeated measurement, and without providing small rewards for effort on each task and more specific prompting for open‐ended tasks (i.e., James and Dylan), we may not have obtained a full picture of their experience. It is interesting to note that the degree of parent‐reported child ER improvement was associated with the degree of improvement on children's BASC‐2 behavioral symptoms and adaptive behavior, and on the CGI‐Severity scores, although the size of the correlations were primarily small. While a mediation analysis exploring whether changes in ER precedes changes in problematic behavior is beyond this study's design, the pattern of findings suggests that the two are at the very least, linked, and further research to test whether ER is a true mechanism of change in this population is warranted (Mazefsky & White, 2014).

Consistent with previous trials, overall gains were maintained between postintervention and follow‐up (Chu et al., 2016; Ehrenreich‐May et al., 2017). Approximately one‐third of children in the treatment group showed minor improvement in clinical severity according to clinician judgment between the end of the intervention and at 10‐week follow‐up, while 20% showed a mild worsening. Some variability in postintervention outcomes should be expected, as children with ASD continue to struggle with many stressors (Wood & Gadow, 2010). In fact, a recent trial indicated that while 84% of children with ASD were designated as post‐CBT responders directly following treatment, this number fell to 53% at 10–26 months posttreatment, with 44% having some loss of gains, 38% maintaining, and 19% showing improvement (Selles et al., 2015). This variability speaks to the need to consider how ongoing support may be provided for children beyond the typical time‐limited nature of manualized CBT.

There are several limitations to these findings. While we employed an evaluator's judgment, this was done using parent‐report information, not direct observation. It is possible that parents’ positive experience participating in the intervention may impact their reporting postintervention. Similarly, therapists were the only raters to report on child engagement, and thus the high ratings may reflect response bias. Additionally, data were not obtained on changes in services or medications, or on the level of school involvement. There is also some question as to the representativeness of the sample. Many parents reported high household incomes and education, self‐identified as White/Caucasian, and all children were required to have sufficient cognitive ability and motivation to participate; it is important to conduct trials more representative of the spectrum to determine effectiveness and generalizability (e.g., Einfeld et al., 2017). Finally, despite randomization, the WL group had higher levels of externalizing symptoms than the TI group at baseline, which was statistically controlled for in all analyses.

Conclusions

Despite the substantial co‐occurrence and moderate correlations among symptoms of emotional problems in children with ASD, current treatment models remain diagnosis specific. The results of this trial set the stage for future research into transdiagnostic approaches that may assist clinicians in working broadly and efficiently. This could include systematic examination of mediating and moderating effects, component analyses of individual activities, and direct observation of target behaviors. The current findings are encouraging, supporting the hypothesis that CBT can be adapted to move beyond current anxiety‐specific frameworks with a greater focus on underlying mechanisms, targeting multiple emotional problems at the same time.

Key points.

This is the first randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of transdiagnostic cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Transdiagnostic CBT targets underlying emotion regulation processes, compared to traditional approaches, which are diagnosis specific.

CBT can be used to improve emotion regulation in children with ASD.

Transdiagnostic CBT results in improved emotional lability and overall severity of mental health problems.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. CONSORT checklist.

Table S1. Descriptive statistics and internal consistencies of baseline measure.

Table S2. Treatment versus waitlist group comparisons of clinically significant psychiatric diagnosis at randomization for full sample (N = 68).

Table S3. Primary and secondary treatment outcomes for treatment completers (n = 60) controlling for pretreatment scores and baseline BASC‐2 externalizing scores.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was provided to the first author via the Chair in Autism Spectrum Disorders Treatment and Care Research, by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research in partnership with Autism Speaks Canada, the Canadian Autism Spectrum Disorders Alliance, Health Canada, Kids Brain Health Network (formerly NeuroDevNet), and the Sinneave Family Foundation. Additional funds from York University. The authors thank the many families who participated in this research, the trainees who acted as therapists in the trial, Dr. Sandra Salem‐Guirgis for supervision, and Lisa Chan and Casey Fulford for their assistance with research coordination. The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

Note

As noted below, in the Treatment Completer group comparison of baseline scores, BASC‐Externalizing was found to differ between groups. We therefore controlled for this in imputation processes for ITT.

References

- Aldao, A. , Nolen‐Hoeksema, S. , & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion‐regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta‐analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 217–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Attwood, T. (2004a). Dylan is Being Teased In Exploring feelings: Cognitive behaviour therapy to manage anxiety (pp. 65–66). Arlington, TX: Future Horizons. [Google Scholar]

- Attwood, T. (2004b). James and the Maths Test In Exploring feelings: Cognitive behaviour therapy to manage anxiety (pp. 65–66). Arlington, TX: Future Horizons. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, S.A. , Lindborg, S.R. , & Seaman, J.W. (2006). Multiple imputation techniques in small sample clinical trials. Statistics in Medicine, 25, 233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont, R. (2013). Secret Agent Society – Operation Regulation (SAS‐OR) Manual. Brisbane, Qld, Australia: Social Skills Training Pty Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont, R. , Rotolone, C. , & Sofronoff, K. (2015). The Secret Agent Society social skills program for children with high‐functioning autism spectrum disorders: A comparison of two school variants. Psychology in the Schools, 52, 390–402. [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont, R. , & Sofronoff, K. (2008). A multi‐component social skills intervention for children with Asperger syndrome: The junior detective training program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 743–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkovits, L. , Eisenhower, A. , & Blacher, J. (2017). Emotion regulation in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 68–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick, P.C. , & Korteland, C. (2004). A prospective study of rumination and depression in early adolescence. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 9, 383–394. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth, T.W. , Hodge, M.A.R. , Sofronoff, K. , Beaumont, R. , Gray, K.M. , Roberts, J. , … & Einfeld, S.L. (2014). Validation of the emotion regulation and social skills questionnaire for young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 1535–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, B.C. , Crocco, S.T. , Esseling, P. , Areizaga, M.J. , Lindner, A.M. , & Skriner, L.C. (2016). Transdiagnostic group behavioral activation and exposure therapy for youth anxiety and depression: Initial randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 76, 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti, D.V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6, 284–290. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, D.A. (2009). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression: Possibilities and limitations of a transdiagnostic perspective. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38(Suppl. 1), 29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (Ed.) (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino, J.N. , & Gruber, C.P. (2012). Social Responsiveness Scale – Second Edition (SRS‐2). Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich‐May, J. , & Chu, B.C. (2013). Transdiagnostic treatments for children and adolescents: Principles and practice. New York, NY: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich‐May, J. , Rosenfield, D. , Queen, A.H. , Kennedy, S.M. , Remmes, C.S. , & Barlow, D.H. (2017). An initial waitlist‐controlled trial of the unified protocol for the treatment of emotional disorders in adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 46, 46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einfeld, S.L. , Beaumont, R. , Clark, T. , Clarke, K.S. , Costley, D. , Gray, K.M. , … & Howlin, P. (2017). School‐based social skills training for young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 43, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, N. , Cumberland, A. , Spinrad, T.L. , Fabes, R.A. , Shepard, S.A. , Reiser, M. , … & Guthrie, I.K. (2001). The relations of regulation and emotionality to children's externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development, 72, 1112–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, N. , Spinrad, T.L. , & Eggum, N.D. (2010). Emotion‐related self‐regulation and its relation to children's maladjustment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 495–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbacz, L.L. , Brown, D.M. , Spee, G.A. , Polo, A.J. , & Budd, K.S. (2014). Establishing treatment fidelity in evidence‐based parent training programs for externalizing disorders in children and adolescents. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17, 230–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, P.R. , Lee, I.A. , Ziv, M. , Jazaieri, H. , Heimberg, R.G. , & Gross, J.J. (2014). Trajectories of change in emotion regulation and social anxiety during cognitive‐behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 56, 7‐15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guastella, A.J. , Gray, K.M. , Rinehart, N.J. , Alvares, G.A. , Tonge, B.J. , Hickie, I.B. , … & Einfeld, S.L. (2015). The effects of a course of intranasal oxytocin on social behaviors in youth diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 444–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy, W. (Ed.). (1976). Clinical global impression scale. The ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology—revised (pp. 218–222). Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Gyurak, A. , Gross, J.J. , & Etkin, A. (2011). Explicit and implicit emotion regulation: A dual‐process framework. Cognitive and Emotion, 25, 400–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtig, T. , Kuusikko, S. , Mattila, M.‐L. , Haapsamo, H. , Ebeling, H. , & Jussila, K. (2009). Multi‐informant reports of psychiatric symptoms among high‐functioning adolescents with Asperger syndrome or autism. Autism, 13, 583–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns, C.M. , Wood, J.J. , Kendall, P.C. , Renno, P. , Crawford, E.A. , Mercado, R.J. , … & Small, B.J. (2016). The treatment of anxiety in autism spectrum disorder (TAASD) study: Rationale, design and methods. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 1889–1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler, A. , Young, J.F. , Hankin, B.L. , Abela, J.R.Z. , Elias, M.J. , & Selby, E.A. (2016). Emotional awareness: A transdiagnostic predictor of depression and anxiety for children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45, 262–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreslins, A. , Robertson, A.E. , & Melville, C. (2015). The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, P. , Stuart, E.A. , & Allison, D.B. (2015). Multiple imputation: A flexible tool for handling missing data. Journal of the American Medical Association, 314, 1966–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord, C. , Rutter, M. , DiLavore, P. , & Risi, S. (2008). Autism diagnostic observation schedule. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Luby, J. , Lenze, S. , & Tillman, R. (2012). A novel early intervention for preschool depression: Findings from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 313–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon, A. (2010). The use and reporting of multiple imputation in medical research – A review. Journal of Internal Medicine, 268, 586–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky, C.A. , Kao, J. , & Oswald, D.P. (2011). Preliminary evidence suggesting caution in the use of psychiatric self‐report measures with adolescents with high‐functioning autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 164–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky, C.A. , & White, S.W. (2014). Emotion regulation: Concepts and practice in autism spectrum disorder. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23, 15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy, P.M. , Nathan, P. , & Norton, P.J. (2009). Efficacy of transdiagnostic treatments: A review of published outcome studies and future research directions. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23, 20–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mcgillivray, J.A. , & Evert, H.T. (2014). Group cognitive behavioural therapy program shows potential in reducing symptoms of depression and stress among young people with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 2041–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally Keehn, R. , Lincoln, A. , Brown, M. , & Chavira, D. (2013). The Coping Cat Program for children with anxiety and autism spectrum disorder: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser‐Stedman, R. , Smith, P. , McKinnon, A. , Dixon, C. , Trickey, D. , Ehlers, A. , … & Dalgleish, T. (2017). Cognitive therapy as an early treatment for post‐traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: A randomized controlled trial addressing preliminary efficacy and mechanisms of action. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58, 623–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby, J.M. , McKinnon, A. , Kuyken, W. , Gilbody, S. , & Dalgleish, T. (2015). Systematic review and meta‐analysis of transdiagnostic psychological treatments for anxiety and depressive disorders in adulthood. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 91–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newgard, C.D. , & Lewis, R.J. (2015). Missing data: How to best account for what is not known. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 314, 940–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen‐Hoeksema, S. , Stice, E. , Wade, E. , & Bohon, C. (2007). Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, S.B. , & Norton, P.J. (2017). Transdiagnostic versus diagnosis specific cognitive behavioural therapies for anxiety: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 46, 11–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaven, J. , Blakeley‐Smith, A. , Culhane‐Shelburne, K. , & Hepburn, S. (2012). Group cognitive behavior therapy for children with high‐functioning autism spectrum disorders and anxiety: A randomized trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 410–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinholt, N. , & Krogh, J. (2014). Efficacy of transdiagnostic cognitive behaviour therapy for anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of published outcome studies. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 43, 171–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, C.R. , & Kamphaus, R.W. (2004). Behavior assessment system for children, second edition (BASC‐2). Bloomington, MN: Pearson Assessments. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M. , Bailey, A. , & Lord, C. (2003). Manual for the Social Communication Questionnaire. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa, A. , & Reyes, N.M. (2011). Improving emotion regulation with CBT in young children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 39, 495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selles, R.R. , Arnold, E.B. , Phares, V. , Lewin, A.B. , Murphy, T.K. , & Stroch, E.A. (2015). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in youth with an autism spectrum disorder: A follow‐up study. Autism, 19, 613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields, A. , & Cicchetti, D. (1997). Emotion regulation among school‐age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q‐sort scale. Developmental Psychology, 33, 906–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P.E. , & Fleiss, J.L. (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin, 86, 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, W.K. , & Albano, A.M. (1996). The anxiety disorders interview schedule for children for DSM‐IV: Clinician manual (child and parent versions). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff, E. , Pickles, A. , Charman, T. , Chandler, S. , Loucas, T. , & Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population‐derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 921‐929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, E. , Hall, K. , Moulding, R. , Bryce, S. , Mildred, H. , & Staiger, P.K. (2017). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic treatment construct across anxiety, depression, substance, eating and borderline personality disorders: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 141–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofronoff, K. , Attwood, T. , & Hinton, S. (2005). A randomised controlled trial of a CBT intervention for anxiety in children with Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 1152–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofronoff, K.V. , Attwood, T. , Hinton, S.L. , & Levin, I. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive behavioural intervention for anger management in children diagnosed with Asperger Syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1203‐1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spek, A.A. , van Ham, N.C. , & Nyklíček, I. (2013). Mindfulness‐based therapy in adults with an autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34, 246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C. , White, I.R. , Carlin, J.B. , Spratt, M. , Royston, P. , Kenward, M.G. , … & Carpenter, J.R. (2009). Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 338, b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch, E.A. , Arnold, E.B. , Lewin, A.B. , Nadaeau, J.M. , Jones, A.M. , De Nadai, A.S. , … & Murphy, T.K. (2013). The effect of cognitive‐behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52, 132–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch, E.A. , Lewin, A.B. , Collier, A.B. , Arnold, E. , De Nadai, A.S. , Dane, B.F. , … & Murphy, T.K. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive‐behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and comorbid anxiety. Depression and Anxiety, 32(3), 174–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R.A. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 25‐52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, K. , Burnham Riosa, P. , & Weiss, J.A. (2015). Brief report of preliminary outcomes of an emotion regulation intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 3487–3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov, N. , Dear, B.F. , Staples, L.G. , Terides, M.D. , Karin, E. , Sheehan, J. , … & McEvoy, P.M. (2015). Disorder‐specific versus transdiagnostic and clinician‐guided versus self‐guided treatment for major depressive disorder and comorbid anxiety disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 35(Suppl. C), 88–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totsika, V. , Hastings, R.P. , Emerson, E. , Lancaster, G.A. , & Berridge, D.M. (2011). A population‐based investigation of behavioural and emotional problems and maternal mental health: Associations with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ung, D. , Arnold, E.B. , De Nadai, A.S. , Lewin, A.B. , Phares, V. , Murphy, T.K. , & Storch, E.A. (2014). Inter‐rater reliability of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM‐IV in high‐functioning youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 26, 53–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbaniak, G.C. , & Plous, S. (2015). Research randomizer (Version 4.0) [Computer software]. Retrieved from http://www.randomizer.org/.

- Volker, M.A. , Lopata, C. , Smerbeck, A.M. , Knoll, V.A. , Thomeer, M.L. , Toomey, J.A. , & Rodgers, J.D. (2010). BASC‐2 PRS profiles for students with high‐functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 188‐199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. (2011). Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence – second edition (WASI‐II). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, L. , Hodgekins, J. , & Langdon, P.E. (2016). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy with people who have autistic spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 49, 41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, J.J. , Drahota, A. , Sze, K. , Har, K. , Chiu, A. , & Langer, D.A. (2009). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 224–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, J.J. , Ehrenreich‐May, J. , Alessandri, M. , Fujii, C. , Renno, P. , Laugeson, E. , … & Storch, E.A. (2015). Cognitive behavioral therapy for early adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and clinical anxiety: A randomized, controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 46, 7–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, J.J. , & Gadow, K.D. (2010). Exploring the nature and function of anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17, 281–292. [Google Scholar]

- Zeman, J. , Cassano, M. , Suveg, C. , & Shipman, K. (2010). Initial validation of the Children's Worry Management Scale. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 381–392. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. CONSORT checklist.

Table S1. Descriptive statistics and internal consistencies of baseline measure.

Table S2. Treatment versus waitlist group comparisons of clinically significant psychiatric diagnosis at randomization for full sample (N = 68).

Table S3. Primary and secondary treatment outcomes for treatment completers (n = 60) controlling for pretreatment scores and baseline BASC‐2 externalizing scores.