Abstract

Previous research on collective action has suggested that both intra‐ and intergroup interactions are important in producing psychological change. In this study, we examine how these two forms of interaction relate to each other over time. We present results from a longitudinal ethnographic study of participation in an environmental campaign, documenting endurance and prevalence of psychological change. Participants, locals (n = 14) and self‐defined activists (n = 14), connected enduring psychological changes, such as changes in consumer behaviour and attitudes to their involvement in the environmental campaign. Thematic analysis of interviews suggested that participants linked the process of change to categorizing themselves in a new environmental‐activist way that influenced their everyday lives beyond the immediate campaign. This recategorization was a result of a conflictual intergroup relationship with the police. The intergroup interaction produced supportive within‐group relationships that facilitated the feasibility and sustainability of new world views that were maintained by staying active in the campaign. The data from the study support and extend previous research on collective action and are the basis of a model, suggesting that intragroup processes condition the effects of intergroup dynamics on sustained psychological change.

Keywords: collective action, intragroup, intergroup, interaction, identity, psychological change, consumer behaviour, environment

Background

Previous studies have shown that participation in collective action can transform participants psychologically in various ways. In a systematic review of the literature, Vestergren, Drury, and Hammar Chiriac (2017) found 19 different types of such psychological changes across 57 studies. A common finding in these studies was that former activists differed from non‐activists a long time after participation in collective action on various demographic, behavioural, and psychological measures, such as marital status (McAdam, 1989), having children (Franz & McClelland, 1994), relationship ties (Shriver, Miller, & Cable, 2003), work–life/career (Profitt, 2001), further involvement (Sherkat & Blocker, 1997), identity (Klandermans, Sabucedo, Rodriguez, & de Weerd, 2002), empowerment (Blackwood & Louis, 2012), radicalization (Marwell, Aiken, & Demerath, 1987), legitimacy (Drury & Reicher, 2000), sustained commitment (Fendrich & Lovoy, 1988), consumer behaviour (Stuart, Thomas, Donaghue, & Russell, 2013), self‐esteem/self‐confidence (Macgillivray, 2005), general well‐being (Boehnke & Wong, 2011), religion (Sherkat, 1998), organizing (Friedman, 2009), knowledge (Lawson & Barton, 1980), and home skills (Cable, 1992).

The majority of studies found that psychological change stayed with the participants beyond participation in collective action; however, some decrease in the acquired changes over time was also found. For example, Marwell et al. (1987) found civil rights activists involved in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference decreased in their commitment to action between 1965 and 1984–1985. Furthermore, Nassi and Abramowitz (1979) found participants in the Berkeley Free Speech movement shifting from being radical to a position in between radical and liberal 15 years after participation (although the former activists were still more radical than the general population). In a six‐wave longitudinal study, German peace movement sympathizers showed a decrease in both macrosocial worries and degree of political activism (Boehnke & Boehnke, 2005).

Even adopting a longitudinal design, most studies failed to produce an account of whether the collective action itself produced the enduring (or declining) changes or addressed the psychological change without offering an explanation beyond level of participation. However, in a survey of participants in the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer camp McAdam (1989) compared participants with camp applicants who did not participate and could thereby establish that participation was a factor in the change.

The present research aimed to extend previous literature by giving an account of the emergence and endurance of psychological changes through participation in an environmental campaign. In the context of the campaign, we present a qualitative analysis of a longitudinal panel study with quantitative measures of interaction and amount of change. In addition, we explore the processes of endurance of these changes illustrated through a case study of consumer behaviour and consumption attitudes.

Explaining occurrence and endurance of psychological change in collective action

There has been some recent progress regarding understanding psychological change in collective action research. Becker and Tausch (2015) and Louis et al. (2017) each suggest that the outcome of the collective action causes and sustains psychological changes. Others point to within‐group processes and appraisal of collective action as the cause of psychological change towards empowerment or new efficacy perceptions (Thomas, McGarty, & Mavor, 2009; Van Zomeren, Leach, & Spears, 2012). The collective action context offers participants a place to re‐assess their perception of collective disadvantage, which in turn motivates future collective action participation (Van Zomeren et al., 2012). Thomas et al. (2009) suggest that to create sustained commitment to collective action a social identity needs to be created with identity relevant norms for emotion, efficacy, and action, through within‐group interaction. These norms create a system of meaning that subsequently form the sustained commitment (Thomas et al., 2009).

In a study of helping behaviours towards international groups, Thomas and McGarty (2009) found that intragroup interaction, in particular outrage norm enhanced, was a key factor in motivating behaviour/commitment to a cause as the outrage norm motivated increased group identification and efficacy beliefs. Social networks influence participation in collective action; the larger our activist network is the more likely we are to sustain our participation and generalize the activist identity, which in turn increases the likelihood to participate in other campaigns (Louis, Amiot, Thomas, & Blackwood, 2016; Thomas, McGarty, & Louis, 2014). The role of intragroup processes in change is also highlighted in sociological studies where they are often referred to as ‘discussions’ within the group between group members (Hirsch, 1990).

In addition to intragroup interaction, there is evidence that intergroup interaction can be important in creating and sustaining psychological change. Intergroup interaction refers to the dynamics in a conflictual relationship between the ingroup of protesters and outgroups (such as police; Drury & Reicher, 2000). The elaborated social identity model (ESIM: Drury & Reicher, 2000, 2009; Reicher, 1996; Stott & Reicher, 1998) suggests that outgroup action changes the context within which participants define themselves and this can be the basis of changed identity. Further, through participation in collective action when participants actualize their shared identity against an opposing force (such as the police) feelings of empowerment may emerge and stay with the participants after the event is over (Drury & Reicher, 2005, 2009). Through the process of empowerment, participants feel agentic and in control of their actions and their world, and are subsequently motivated to sustain their participation.

According to ESIM, the two forms of interaction could interrelate, as the interaction with an outgroup such as the police affects the exchanges within the ingroup (protesters). However, a limitation in many of the previous studies is that the focus has been on either intergroup or intragroup processes. One reason for this limitation is to do with design. First, most studies did not look at interaction per se and have relied on questionnaire survey measures (Fendrich & Lovoy, 1988). Second, where ethnographic designs have been employed these have tended to be largely cross‐sectional rather than panel studies (Drury & Reicher, 2000; Drury, Reicher, & Stott, 2003).

The present research

Context

The study was based on an environmental campaign (the Ojnare campaign) where campaigners aimed to save a piece of forest and the lake Bästeträsk from becoming a limestone quarry on one of Sweden's largest islands, Gotland. The issues and features described below are based on accounts from the participants in the study, information from other people involved in the campaign, media reports, and the first author's own experiences during the time spent in the campaign.

The Ojnare campaign started in 2005 and had its culminating point in late August 2012. When the deforestation work to prepare for the quarry was authorized in mid‐July 2012, members of an environmental youth organization decided to aid locals protesting the quarry and set up camp in the Ojnare forest.

During the first week of August, campaigners were active in the forest trying to obstruct the deforestation machines. During this time, there were about 15 campaigners from different groups in the forest. In the second week of August, the local island police called for reinforcements from the dialogue police in Stockholm, specifically trained to work with protest groups, to ensure that the deforestation work could be carried out without interruptions from the campaigners. During this week, the campaigners continued their active presence in the forest and there were no significant clashes between police and campaigners. In the third week, farmers from the north region of the island (who were dependent on the water from the lake) joined the campaign. Farmers parked their tractors and trailers on routes in and out of the forest to hinder the deforestation machines to reach the area. The number of campaigners actively protesting in the forest was still relatively low.

The fourth week, the last week of August, has come to be referred to as the ‘police‐week’ by campaigners as the police were reinforced by 74 officers, vans, all‐terrain vehicles, horses, and a helicopter. This week was characterized by clashes between the campaigners and the police. During the police‐week, approximately 200 campaigners were active in the forest when the deforestation company was there. The police tried to evict the campaigners by physically removing them to the outskirts of the forest, and in some cases driving them several kilometres away from the area and dropping them off. The actions taken by the campaigners – hiding in the forest, sitting down in front of machines, and so on – were characterized by non‐violence. This pattern of events continued for about a week and ended when the deforestation company withdrew their involvement in the preparation work for the quarry.

Even though the most intense period of the campaign was over, campaigners continued their involvement on various levels during the following 18 months when the interviews for the study took place. A few campaigners stayed in the camp and then moved to a nearby abandoned hospital. The campaign continued by fighting the quarry company in court, and by various events such as rallies and seminars to raise awareness about the issue. The campaigners stayed in contact with each other, gathered in the forest and other places. Campaigners not living in the area stayed in contact via social media and met up in other places in Sweden to raise awareness of the campaign and other environmental issues. Throughout the 18 months of the study, the campaign was ongoing and many campaigners kept interacting in various ways.

This study explores the processes behind collective action participants’ enduring psychological changes through a panel study. In doing so, we explored all possible types of changes in one campaign. To our knowledge, no previous research has explored the process of emergence (or endurance) for the whole range of types of changes in one single campaign. The range of type of changes is of importance as some changes might emerge through one process, for example, intergroup interaction, whereas others might be influenced by intragroup interaction. Furthermore, analysing the number of changes people experience allows us to make claims about endurance, for example, if a specific type of change endures whereas another declines.

The process and endurance of psychological change are exemplified by transformation in consumer behaviours and attitudes. Consumer behaviour is one example of psychological change that participants in collective action can undergo, and the process of change and endurance might be generalizable to other psychological dimensions. Furthermore, studying elements of consumer behaviour change enabled triangulation by obtaining data from external sources.

Change in consumer behaviour can be an important dimension of change, both subjectively and behaviourally. Stuart et al. (2013) found that participants in the Sea Shepherd Conservation Movement changed their diet to become vegetarian, vegan, or at least decrease their meat consumption as a result of being involved in the movement, linked to a change in identity through being part of the group. Further, Salt and Layzell (1985) found a change in style (e.g., clothes) and shopping (e.g., choice of products) among miners’ wives involved in the 1984–1985 UK strike. In the context of an environmental protest, we examined how intergroup interaction might transform intragroup interaction and effect enduring psychological changes.

In this study, we start by outlining the prevalence and endurance of changes reported by the participants in our sample, then defining the process through which the changes emerged, linked by the participants to the conflictual intergroup interaction whereby participants came to (re)categorize themselves. Next, we show how the participants linked the process of endurance to intragroup processes (such as support and communication), which were transformed by intergroup interaction with police. Some previous research has suggested that different level of experience (Barr & Drury, 2009) and different levels of previous participation (Drury & Reicher, 2000) affect the changes; therefore, the participants in our sample are divided into self‐defined activists and locals to allow for comparison. We predicted that the self‐defined activists would have more collective action experience than the locals and consequently to some extent already be radical/politicized or empowered and hence experience less changes than the locals through their participation in the campaign. Lastly, we present a case study based on change in consumer behaviour and attitudes as an example to illustrate the process of emergence and endurance.

Method

Data collection

The study adopted a longitudinal ethnographic approach, and data were gathered through repeated interviews with participants in the campaign, a one‐off interview with significant others, and external sources in the form of sales records from local shops.

Interview data

The participants were sampled from the population of participants in the Ojnare campaign. The first author initially opportunistically approached them during a visit to the camp. The campaigners assisted the researcher with contacts to other campaigners. The inclusion criterion for participation in the study was to have been involved to some extent in the Ojnare campaign. Only one person declined participation, and one activist withdrew participation after the first interview (an additional activist was added as replacement). The total sample (N = 28) is divided into two groups;1 self‐defined activists (n = 14) who travelled to the island to participate (referred to as activists in this study), and locals (n = 14) living in or in close proximity to the area. The distribution of demographic data of the participants is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demography: gender, age, previous participation, and occupation

| Gender | Age | Previous participation | Occupation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Range | Mean | Total | E | S | R | U | |

| Activists | 5 | 9 | 18–43 | 26.43 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 2 |

| Locals | 6 | 8 | 36–78 | 58.21 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

Occupation: E = Employed, S = student, R = retired, U = unemployed.

Semi‐structured interviews were conducted with each participant once a month for 6 months, and then a final seventh interview after 18 months. In total, 196 interviews with the participants were conducted. The interviews were semi‐structured, covering the themes of participants’ perceptions (pre‐ and post‐participation) of themselves, their relation to others, and their view of different campaign actions and campaign issues. The schedule included questions such as ‘tell me a bit about your life’ and ‘tell me about your life before the campaign’. If the participants did not mention any personal changes related to their involvement in the campaign questions such as ‘has anything changed during your time in the campaign?’ were asked. Interviews in months 2–18 also contained follow‐up questions relating to the experiences, construals, and psychological changes reported in previous interviews along with questions about the participants’ lives both within and outside the campaign since the last interview. In addition to the qualitative dimension of the interviews, each interview included a quantitative element to capture the participants’ perceived level of activity in the campaign over time measured on a 7‐point Likert scale. This was followed by asking what that specific number meant and how they had participated (if they had), and what the difference was to previous month(s) (if there was a difference).

The aim of the repeated longitudinal design was to capture participants’ experiences, construals, and the campaign issues over time. Adopting a panel design allowed for systematically collecting data to explore the endurance of the possible changes such as consumer behaviour and attitude change. The interviews ranged from 20 to 180 min (M = 40 min). All interviews were conducted in Swedish by the first author and audio‐recorded. The interviews were transcribed verbatim, and sections relevant to the study were translated into English.

Witness accounts

In addition to the interviews with participants, one interview with a significant other, chosen by the participant, was conducted for each participant. These additional interviews aimed to explore whether someone close to the participants had noticed the changes to add support (or disconfirmation) for the changes reported by the participants. The interviews were based around three questions: ‘can you tell me a bit about X's life?’, ‘can you tell me a bit about X's life before the campaign?’, and ‘have you noticed any changes in X since he/she got involved in the campaign?’ The interviews ranged from 20 to 90 min (M = 40 min).

Behavioural data

To examine whether there was change concerning consumer behaviour among campaign participants more generally, two local supermarkets and one greengrocer in the north of Gotland were approached and information and sales records were obtained. The shops were selected based on their close proximity to the area of the protest. One supermarket did not want to share their sales records. The first author made a visit to the shops 8 months after the police‐week. The sales records contained information about the increase/decrease in products such as meat, organically produced food, and other products stamped with the watermark ‘ecological’ (Swedish: ekologisk) or ‘environmentally friendly’ (Swedish: miljövänlig). The two measure points were 1 month before the police‐week and 8 months after (these two points were chosen as they were regarded to be sufficient to indicate a change between before and after the struggle). For example, an increase in sales of organic products, or decrease in meat sales, after the protest in the forest could indicate that there had been a change in consumer behaviour among those living in the area. The area and population of north Gotland are small; therefore, changes in the sales could be an indicator of the effects of the presence of the campaign, hence function as supplementary data on consumption consequences.

Analytic procedure

Qualitative

To explore the interview data, thematic analysis as described by Attride‐Stirling (2001) and Braun and Clarke (2006) was used. The transcripts of the interviews were repeatedly read through to get a comprehensive sense of the material, and notes were made and passages of interest highlighted. The participants’ accounts of psychological change related to the campaign were separated out to form the subject of analysis. The data on reported changes linked to the campaign were coded into meaning units, words, and sentences with shared content (e.g., ‘I only buy organic and ethically produced shampoo now’) relevant for the study. The meaning units were then summarized before the final step where each unit was labelled (e.g., ‘shopping’), forming the categories. An inter‐rater reliability test of the 12 initial coded types of change in the coding scheme was performed on 10% of the data with a neutral judge, using Cohen's kappa (κ = .86). The test led us to merge the codes self‐esteem and self‐confidence.

Quantitative

In addition to the qualitative analysis, the prevalence and endurance of the categories of change over time were assessed quantitatively. Each category was coded by the authors with 1 (reported change) or 0 (no reported change in the category or previous change no longer apparent). The change was coded based on the participants’ construals of the time before participation in the campaign; hence, the reference point in each case was pre‐participation. The coding of the prevalence and endurance of the categories was also subject for inter‐rater reliability testing using Cohen's kappa on 10% of the data. The test showed a very good level of agreement, κ = .95.

Due to the longitudinal dimension of the study, there was a risk of a social desirability element in participants reporting a consistency in their responses (King & Bruner, 2000). The triangulation of the three data sets (interviews, witness accounts, and behavioural data) was used to identify/check for possible social desirability.

In the data, it was assumed that the participants with the least previous participation would report the most changes. As the changes were not weighted against each other, or the magnitude measured, we only counted if there was a change in each category or not.

One advantage of using both qualitative measures and quantitative measures in this study was the extent to which the qualitative data enabled us to go further than the quantitative data. The mixed method allowed us to add to the numbers (summary of changes) and explore what the changes meant to the participants and the effect these changes had on their lives.

Results

The Results section presents evidence of endurance and prevalence of the changes linked by participants in our sample to their involvement in the campaign, and analysis of these accounts is presented next. We then show how changes were sustained. Lastly, we present a case study on consumer behaviour change as an example to illustrate the sequential interrelation between the processes of enduring changes.

Endurance and prevalence of change

All participants in our sample connected various psychological changes to their involvement in the campaign. The participants reported 11 types of psychological change linked to their involvement in the campaign: personal relationships (e.g., connections with friends or family members), work–life/career (e.g., changing area of work), extended involvement (i.e., getting involved in other campaigns and/or issues), consumer behaviour (i.e., obtaining, use, and disposal of services and products such as shampoo), empowerment (i.e., belief that they can achieve something), radicalization/politicization (i.e., change in beliefs, behaviours, and feelings towards becoming more political, acting in an ‘activist’ way), (ill)legitimacy (i.e., perceived rightness of own and other group's actions), self‐esteem/self‐confidence (i.e., feelings about oneself, such as gaining confidence to stand up for own opinions), well‐being (e.g., feeling better physically), skills (e.g., organizing), and knowledge (e.g., of the judicial system) (for more thorough description of participants’ changes see Vestergren, Drury, & Hammar Chiriac, 2018). Table 2 summarizes the number of changes each activist linked to their involvement, and the endurance of these changes by showing their prevalence over time.

Table 2.

Number of changes and endurance for the group of activists

| Month | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 18 | M/pp | |

| A1 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| A2 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9.43 |

| A4 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8.57 |

| A5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| A6 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| A7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5.71 |

| A8 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4.71 |

| A9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 7 |

| A10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 7.71 |

| A11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 10.57 |

| A12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| A13 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3.43 |

| A14 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| A15 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2.71 |

| M/month | 7.86 | 7.86 | 7.79 | 7.57 | 7.43 | 7.43 | 6.50 | [Group M = 7.49] |

Each type of change every month was assigned the value 1 (e.g., relationship 1 + radicalization 1 + legitimacy 1 + consumer behaviour 1 = 4).

All activists (Table 2) and locals (Table 3) in our sample of participants indicated endurance in the reported changes. The data for the locals are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Number of changes and endurance for the group of locals

| Month | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 18 | M/pp | |

| L1 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5.57 |

| L2 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| L3 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| L4 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| L5 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8.14 |

| L6 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| L7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| L8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6.57 |

| L9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9.86 |

| L10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| L11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| L12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| L13 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5.86 |

| L14 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2.14 |

| M/month | 8.71 | 8.71 | 8.50 | 8.21 | 8.07 | 8.07 | 7.79 | [Group M = 8.30] |

Each type of change every month was assigned the value 1 (e.g., relationship 1 + radicalization 1 + legitimacy 1 + consumer behaviour 1 = 4).

In general, the locals experienced more changes (M = 8.30) than the activists (M = 7.49). However, there were some activists who reported a large number of changes (e.g., A11, A12, and A14), and some locals who reported only a small number of changes (e.g., L13 and L14). Further, the locals’ changes endured to a greater extent (difference between month 1 and month 18 = 0.92) than the activists’ (difference between month 1 and month 18 = 1.36).

The most prevalent and enduring change in both participant groups was personal relationships, closely followed by knowledge (Table 4). Table 4 shows the mean value of each category of extent of change over time for all participants in our sample.

Table 4.

Endurance for each category over time for both participant groups

| Month | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 18 | M | ||

| Relationships | A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Work–life/career | A | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.32 |

| L | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.38 | |

| Extended involvement | A | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 0.61 |

| L | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.83 | |

| Consumer behaviour | A | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.70 |

| L | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.88 | |

| Empowerment | A | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 0.88 |

| L | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.92 | |

| Radicalization/politicization | A | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.58 |

| L | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.71 | |

| (Ill)Legitimacy | A | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0.70 |

| L | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.82 | |

| Self‐esteem/self‐confidence | A | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.63 |

| L | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.59 | |

| Well‐being | A | 1 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.81 |

| L | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.57 | 0.82 | |

| Skills | A | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| L | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.43 | |

| Knowledge | A | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| L | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | |

| Level of activity | A | 5.79 | 5.29 | 4.71 | 4.07 | 3.57 | 2.79 | 2.00 | 4.03 |

| L | 6.57 | 6.43 | 6.29 | 6.00 | 5.71 | 5.71 | 5.14 | 5.98 | |

A = Activist, L = locals.

Mean for each category of change was calculated based on participants’ reported change after participation in the campaign: 1 = reported change, 0 = no change reported or changed back to prior the campaign. Activity was measured by asking participants to rate the statement ‘I regularly participate in the campaign’ 1 = strongly disagree – 7 = strongly agree.

The least common changes among the participants were work–life/career and skills. For some participants, changes decreased over time (Tables 2, 3, 4); however, there is still strong evidence that the psychological changes endured far beyond the immediate event.

Intergroup interaction and categorization

In addressing the origins for the changes, the participants highlighted the conflictual interaction with the police. Most of the interviewees had never had any encounters with the police before their involvement in the campaign; this encounter was a critical part of the participants coming to categorize themselves (and others) in a new ‘activist’ way, and changed participants’ attitudes towards and perceptions of the police:

A7: it felt like they [police] were treating me like I was a terrorist while I felt that what I did was just totally right [ ] I thought that they [police], like they would be on the side that I thought was right [ ] I don't believe in them as much since they according to me do stuff that is wrong [month 1]

The extract above refers to how the police behaviour in the police‐week was seen as typical of the wider category of police. Participants without prior encounters with the police said that before this event they saw the police as a whole as a legitimate force that was on the ‘right side’. As a result of their behaviour being in contradiction with the participants’ expected norms, the police as a whole came to be seen as an illegitimate category. The interaction with the police was reported by all participants in our sample as the key element that brought the whole group together and altered the intragroup interaction:

A6: they [police] made it really messy [the police‐week], [ ] they had no idea what they were doing, so incompetent, all they did was working against themselves, like we got so much bigger… eeer… and stronger [ ] we got stronger, with those not living in the camp full‐time, like we got more contact with those who might live on Gotland and are engaged or became engaged, there were lots of people gathering and coming here then, mostly we got a stronger bond with the entire group [month 1]

In the following extract, a participant talks about how the intergroup interaction created a unity within the group of campaigners, changing the relationships among the campaigners:

A7: Before the police came here it was a divide between the locals and us, like the locals were not really sure about us you know [ ] when the police started misbehaving it was like we were all the same [month 1]

Both activists and locals shared this perception of a new superordinate group:

L10: we were not entirely happy when the youths, the activists, showed up [ ] we didn't see them as part of our campaign they had nothing to do with us [ ] After the police came there was just no doubt about it, they [activists] were there for the same reasons as us and it felt like we were all just one big group of the same [month 4]

Reports from most of our participants suggest that a superordinate identity emerged, or at least the boundaries of the identity became more inclusive to include both locals and activists. All participants in our sample created new or stronger relationships with the ingroup (the other campaigners), and linked this change to the intergroup interaction with the police during the police‐week, where they all became closer and formed enduring relationships with other campaign participants as part of a single group.

Intragroup interaction

Supportive relationships and intellectual support within the group were explained by participants as a function of the intergroup interaction during the police‐week:

L2: If it hadn't been for the, errr, the, the police‐week, I mean they [police] made us tight and being tight means that we support each other, and we talk and learn from each other, it's like I get support for all my thoughts from all the others [ ] the more I talk to the others the more certain I get that I'm right you know [month 4]

Locals, and a few activists who stayed in the area or were in close proximity to the area, continued to have gatherings (such as group walks and festive meals) in the forest even after the police and the deforestation company left:

L7: I think that since I'm still in Ojnare, I mean not actually there everyday but we still hang out everyday and that's what keeps me going [ ] it makes it easier to stay environmentally conscious and politically… eerm you know more active when you're around your people all the time [month 5]

The majority of participants in our sample specifically talked about within‐group relations as the mechanism that kept them the new person they had become through their participation in the campaign:

A2: If it hadn't been for my 24/7 engagement and all the wonderful friends everyday I don't think I would have been me, or well I would probably have gone back to being the old boring me but you just can't when you get so much strength from everyone all the time [month 18]

These within‐group relations contained elements of intellectual support, sometimes referred to as discussions with other group members:

L8: we still gather several times a week, or at least once a week, and have like gatherings around a camp‐fire in the forest, long walks, and just like be with each other [ ] we usually talk about the campaign and what happens and like things [ ] like how to reduce plastic, or the dangers with plastics, and other important things [month 5]

There were also six participants who connected the lack of involvement and continued relations with other ingroup members to their changes:

I: so what do you think makes you feel like, eeer, like you wouldn't do stuff [skipping2 and being a vegan] anymore?

A5: I don't know, but like I said, I don't see the Ojnare‐people anymore and I think that like makes me a bit disconnected from the whole thing [month 6]

The participants in our sample made connections between the intergroup and intragroup interaction in the environmental campaign for the emergence and endurance of their psychological changes.

Case study: Consumer behaviour and endurance

One psychological change that the participants in our sample linked to conflictual interaction with the police and which they also said was sustained by social relations within the campaign was consumer behaviour. Participants reported various changes in consumer behaviour, such as shopping for more eco‐friendly or locally produced goods, choosing organic, ecological and fair‐trade brands, reducing shopping in general, skipping, and changing their diet. These behavioural changes were connected by most of the participants (four participants reported no change) to their participation in the environmental campaign, to the repositioning of the self and change in attitudes as a consequence of the conflictual relationship with the police:

L6: I'm not going to support the state and consumer society. They are not on my side, you saw that in Ojnare, they are all pigs and they treated us like scum. I can't support that eeerr.. hah I guess you can say the police made me radical and stop eating meat…but it's true actually if the police hadn't been such pigs I would never had realized how the world works so maybe I should thank them for making me a new and better person [month 3]

Some participants reported more than one change in this category, such as both changing their diet and eco‐friendly shopping. However, as there was no difference in endurance between the various consumer behaviours reported by each participant they were recorded as one change for each participant that reported more than one. Table 5 outlines the distribution of consumer behaviour change within the sample of activists.

Table 5.

Change in consumer behaviour for the activists per month

| Month | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 18 | M/pp | |

| A1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.57 |

| A6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.86 |

| A12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.43 |

| M/month | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.57 | [Group M = 0.70] |

Mean for each category of change is calculated based on reports from the participants 1 = reported change, 0 = no change reported or changed back to prior the campaign participation.

The mean change for the activists was lower each month than for the locals, shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Change in consumer behaviour for the locals per month

| Month | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 18 | M/pp | |

| L1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L14 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.29 |

| M/month | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | [Group M = 0.88] |

Mean for each category of change is calculated based on reports from the participants 1 = reported change, 0 = no change reported or changed back to prior the campaign participation.

One of the participating locals reported no change concerning any of the consumer behaviours, compared to three activists. Evidence for change in consumer behaviour is provided by additional data sources. The significant others to the participants who reported change in consumer behaviour all talked about a noticeable change in consumer behaviour:

SA5: the change is so huge and it's all from Ojnare. I mean I get that they all got really close and that it changes things like eeer it was really horrible what they had to go through [police‐week] but who would have thought it would make [A5] roll around in skips looking for food [Mother to A5]

The significant other not only reported the change but also gave an account of explanation through intragroup (getting close) and intergroup (police‐week) interaction. In addition to the participants’ and their significant others’ accounts of changes in consumer behaviour, supplementary behavioural data were collected from two shops. One of the shops, a supermarket, reported a 10.4% increase in their sales of organic, ethically, and fair‐trade products such as vegetables and soaps from before the police‐week to 8 months after. The second shop, an independent green grocer, reported having to increase their farming areas to be able to meet the increased demand for organically produced vegetables during the 8 months following the events in the forest. Most activists left the island after the police‐week; therefore, the increase in ethically and organically produced products cannot simply be discounted as an outcome of extra people living in the area, and must be linked to changes in behaviour among campaign participants. The next section aims to illustrate the relation between the change (consumer behaviour) and endurance through a comparative case study.

Consumer behaviour and endurance

The change in consumer behaviour endured for various periods of time for the participants in our sample (Tables 5 and 6). Two participants were chosen to illustrate the relationship between consumer behaviour change and endurance based on their ability to articulate their status of consumer behaviour in an accessible and understandable way. The chosen participants were both female; the activist (A11) was a student in early adulthood, and the local (L4) was full‐time employed and in her early 50s. Excerpts from the interviews with the activist serve to illustrate a change in consumer behaviour that occurred following police‐week but decreased over time (months 1, 3, 6, and 18):

I: you told me earlier that you became a vegan during your stay in the Ojnare camp, why is that?

A11: the camp is mainly vegan, and it's about animal cruelty, its ethically and morally right. I don't want to support that industry [month 1]

In the first interview, the participant had just become vegan as a consequence of participation in the campaign. This change into a vegan diet was still enduring in the third interview:

A11: Yeah, I'm still vegan, of course!

I: so why is being vegan important to you?

A11: It's about saving the earth, and not supporting the…eer, you know, capitalism [month 3]

The participant explained the change using an ethical framework based on fairness as in the first interview. In interview 6, the participant explained that there had been a slight change in diet, it was still a change compared to prior participation in the campaign but no longer as strict:

A11: we always talk about food, and you know what, I'm not so hard on the vegan thing anymore

I: oh, ok, what do you mean?

A11: eer, I'm still vegetarian but…eer, well, it's just easier and I feel better [month 6]

The decrease in the change was even more apparent in the last interview:

A11: you know I moved and stuff, and I mean, eer, I do eat some meat, but only locally produced

I: ok, and why is that?

A11: you know, I want to support the local small farmers…. you know, the milk thing… and it's still like environmentally friendly [month 18]

The participant reported a change in diet from eating meat prior participation to becoming vegan during the campaign, and then decreased in the strictness of diet to a vegetarian diet, and subsequently adding locally produced meat to the diet. Interestingly, an ethical fairness framework was used in justifying the diet throughout the interviews, which was a characteristic of the content of the activist identity. Even though the change decreased, the choices were explained through the content/norms of the identity. There were also reports of increased change and endurance, illustrated here through excerpts from interviews with L4 (months 1, 3, 6, and 18):

I: Your husband said you've become a vegetarian too, why did you make that decision?

L4: eer, my husband has been a vegetarian for years you know, but I, I… well I can't put my entire soul into this [Ojnare] and not follow it through you know

I: but what does it have to do with Ojnare?

L4: mmmm… it's about human rights, I guess that's what it all comes down to, you know saving the environment means fighting the power [month 1]

The local had changed her diet to vegetarian and linked this change to ‘fairness’ content of a new self‐categorization based on the Ojnare campaign. Her dietary change increased a few months into the study:

I: what has happened since last month that made you more towards vegan food?

L4: I don't know really, it just felt like the next thing to do, it's not that big a change

I: what's important about it?

L4: …everything matters in making a bigger change, even small things like this [ ] if we want to change the world we have to start with ourselves… I've learnt that during this campaign [Ojnare] [month 3]

After changing from vegetarian diet to vegan diet, the participant remained vegan throughout the period of the study:

I: [ ] you're still keeping up with the vegan life

L4: yes [month 6]

I: what's important about being a vegan?

L4: I feel better… just physically, joints and stuff … and also making a contribution to the cause

I: cause?

L4: haha, you know, saving the earth, fighting the power, the system… it was just so obvious in Ojnare, how everything is connected, and after seeing how we were treated by the police it's just… it's not like it's a hard choice [month 18]

Both participants justified their dietary choices based on the ethical fairness framework throughout the interviews. The specific change was connected to a larger cause, the ethical fairness content of the identity, an identity that emerged through the interaction with the police.

As suggested by Vestergren et al. (2018), intragroup interaction could facilitate sustainability of personal changes through participation in collective action. To illustrate this in the case of the two participants, we used their reported activity levels in the campaign as a measurement. When asking participants to elaborate on their chosen number of level of activity and what that participation involved they always referred to elements of interactive activity in the campaign such as spending time with other campaigners. Table 7 outlines the relation between the two participants’ dietary change and level of activity, their intragroup relations.

Table 7.

The link between enduring change in consumer behaviour and level of activity

| Month | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 6 | 18 | ||

| A11 | Diet | Vegan | Vegan | Vegetarian | Locally produced meat |

| Activity level | 7 | 7 | 3 | 1 | |

| L4 | Diet | Vegetarian | ‘Vegan’ | Vegan | Vegan |

| Activity level | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |

Activity level was measured by asking participants to rate the statement ‘I regularly participate in the campaign’, on a 7‐point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree).

The level of activity predicted ethical diet for both the participants. The data from the activist (A11) indicated a relation where diet and activity level decreased together, whereas in the data from the local (L4) the activity was consistently high and the level of diet change increased throughout the 18 months. The relationship was consistent throughout the data for most of the participants in our sample, indicating that the level of activity – intragroup interaction – was important in the endurance of psychological changes. In our sample of participants, 75% (21 participants) showed a clear relation between activity level and endurance of change.

Discussion

In this paper, we have documented and analysed the endurance and process of psychological change through participation in collective action in one environmental campaign. In accounts from participants, first we found a variety of types of change that sustained over time. Second, we found a relationship between the emergence of these psychological changes and conflictual intergroup interaction with the police. Third, there was evidence that this intergroup interaction consequently altered the intragroup relations within the group of campaigners, making them more united through a shared social identity. Fourth, the stronger within‐group relations facilitated the sustainability of the psychological changes over time. This was illustrated with a case study of two participants’ change towards consumer behaviours.

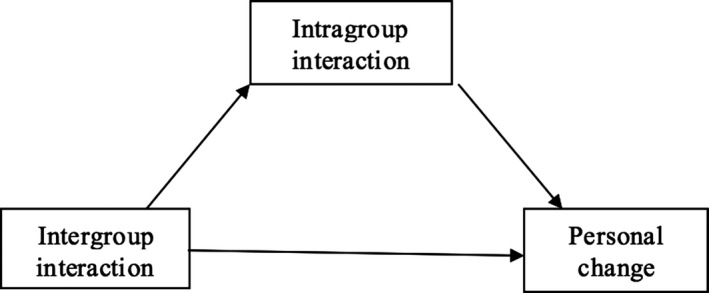

This study extends previous models (Becker & Tausch, 2015; Blackwood & Louis, 2012; Thomas et al., 2009; Van Zomeren et al., 2012) of psychological change and sustained participation in collective action by suggesting the importance of the interrelation between intergroup and intragroup interaction. Further, the study adds a longitudinal analysis of the processes behind the enduring changes, which previous studies lack due to methodological limitations (Drury & Reicher, 2000, 2005; Drury et al., 2003). The results from this study suggest a model, Figure 1, for enduring psychological changes, according to which intragroup processes mediate the effect of intergroup dynamics on enduring psychological change through participation in collective action.

Figure 1.

Mediation model of enduring psychological change.

The conflictual intergroup interaction with the police, the perceived contradiction between expected behaviour and experienced behaviour, created a change in identity boundaries (Drury et al., 2003), which created within‐group support and discussions. These new within‐group relationships helped the participants sustain their beliefs and practices and made the participants more open to arguments as they now identified more with activists.

This is the first time, to our knowledge, that psychological change, process, and endurance have been connected in this way. In this paper, we made the connections using the example of change in consumer behaviour. Consumer behaviour is of importance as an expression of a dimension of social identity (Salt & Layzell, 1985; Stuart et al., 2013). For example, the consumer change in this study had environmental characteristics such as reducing the use of plastics and meat, and this was explained using a wider ‘fairness’ framework. Participants in another type of collective action concerning other issues may have other contents in their consumer behaviour change.

It could be argued that simply participating in the study, through continuous interviews about participation and the campaign, participants were facilitated in keeping the identity salient. However, changes endured throughout the 18 months, and during 12 of those months, no interviews were conducted. Relatedly, the interview format, whereby the same questions are asked each time, might encourage participants to present themselves as consistent in their answers over time, or overstate their continued involvement in the campaign, as an outcome of participating in the study for 18 months. The changes reported by the participants were checked against the supplementary witness accounts from their significant others.

Furthermore, embedding oneself in the research environment entails biases. Drury and Stott (2001) highlighted three key potential biases that arise through ethnographic embeddedness in intergroup conflicts: partiality of access, partiality in observations, and partiality in analysis. Relatedly, in this study there are biases regarding access, responses (observations), and analysis. We will address these three in the given order and discuss how they may have affected the different stages of this study. To make the data collection possible, there was a need for the researcher to embed herself in, and commit to, the campaign. Utilizing this ethnographic approach in sampling of participants is not without implications. The participants were not recruited randomly and equally; rather, the selection process depended on the relationships built between the researcher and the campaigners. Hence, there was a partiality in accessing the participants and the data. This type of partiality in accessing the participants made the campaigners view the researcher as part of the ingroup and most likely affected the participants’ willingness to participate and share information, in line with research on shared identity and cooperation (Drury, Cocking, & Reicher, 2009; Levine & Thompson, 2004). For this reason, contact with other groups involved in the conflict (the police and the mining company) was avoided to be able to keep the relationships with the campaigners and meet the requirements for longitudinal data collection (Drury & Stott, 2001). For this research, it was crucial for the researcher to embed herself with the campaign. Approaching the participants as an external observer could, and most certainly would, have limited the data as the participants would have been more reluctant to give information or been defensive in their responses.

In relation to the second type of bias, partiality in observations, the researcher might have identified with the participants, ‘become one of them’, which in turn might have influenced the information sought, and importance attributed, to certain elements in the interviews. Additionally, the researchers’ pre‐existing knowledge might have influenced the data by regarding some results as more important than others. This could have resulted in the interviewer perceiving some information as more important to the study and thereby given more attention in the interviews, while other issues brought up by the participants might have been ascribed less attention. Furthermore, by the researcher being embedded in the environment and with the participants she had inside knowledge about, for example, events and other group‐related or personal information that could easily have been missed by a researcher who was merely observing.

Considering the third type of bias, partiality in analysis, our shared identity with the participants might have influenced of response that could be found (Willig, 2008), consequently producing accounts that were in line with the first author's and the ingroup's perspective, or presenting the ingroup in a favourable way (Taylor, 2011). However, it cannot be assumed that these are issues that only apply to this type of research. Most researchers have interests, theories, and methodologies they want to support, which might be reflected in their choice of population, methodologies, approaches, and analysis. In fact, as argued by Drury and Stott (2001), the partiality in the data collection might have minimized the partiality in the analysis. By embedding herself in the daily life in the campaign, and with the participants in their daily life, it can be argued that the analysis produced a more accurate and objective account with decreased risk of misunderstandings and inaccurate observations.

To further avoid some of the biases, such as the self‐reports and our own effect on the research, an inter‐rater reliability test (LeCompte & Goetz, 1982) was performed. Furthermore, data were consistently compared to previous research to limit the personal and epistemological affects we may have on the data, and we used additional data sources in the form of witness accounts and external behavioural data to triangulate the results.

The seven participants (six activists and one local) who did not show a clear relation between activity level and endurance of change were all involved in other campaigns throughout the study. That involvement could function to keep their activity level high (through another campaign) and thereby sustain changes. Similar to Drury and Reicher (2000), we found that participants with the least prior participation experienced more change, which could account for the difference in group mean in our sample (see Tables 2 and 3). This also offers an explanation for participants who differed from the pattern; this was A12 and A14's first campaign and A11's first conflictual campaign, and L13 and L14 had extensive participation in collective action in their youth and could therefore be expected to have changed to a ‘political’ identity prior to this campaign. Even though it could be expected that the locals had less previous collective action participation than the activists, future research should more precisely examine the effect of number and type of previous collective actions.

The importance and added richness of the qualitative element are demonstrated in the exploration of intergroup and intragroup interaction, and specifically highlighted in the comparative case study of enduring change in consumer behaviour. The qualitative data demonstrate the relationship between change and process of endurance in a way that the quantified data would have been too limited to demonstrate. The qualitative element enables examination of the reasons behind the change, the subjective effect it has on the participant's life.

The concept of ‘locatedness’ (Di Masso, Dixon, & Pol, 2011; Dixon, 2001; Hopkins & Dixon, 2006) may shed additional light on the process of enduring psychological change, as a part of the perceived intragroup interaction or as a third intertwined dimension of the process. The physical geographical area where the campaign took place could facilitate the endurance of the changes by functioning as a reminder of the cause and the features of the struggle. In addition to intragroup interaction, this in turn could further explain why some participants, such as the locals, experience more enduring change than the activists who left the area (cf. Hopkins & Dixon, 2006). The geographical place itself could function as a contributor to the salience of the social identity, as some identities are defined spatially by a place (Di Masso et al., 2011; Reicher, Hopkins, & Harrison, 2006), and decategorization is less likely to occur when the identity boundaries are still visible (Dixon, 2001). Additionally, the intensity of emotional experiences for many participants, rather than simply the nature of the content of relationship change (from legitimate to illegitimate), could serve to explain the endurance of the psychological changes described here (Swann & Buhrmester, 2014; Swann, Gómez, Seyle, Morales, & Huici, 2009). This, like the role of locatedness, would need to be examined in a future study designed to test the role of different theoretical explanations.

Furthermore, there may be a difference, for example, in what is seen as ‘radical’ by the participants; someone who has never been involved before might see a sit‐down protest as radical, while someone more experienced might see such a sit‐down as societally normative and damage to deforestation equipment as radical. Through the qualitative dimension, especially through the case study of consumer behaviour, this study touches upon the impact of the changes on participants’ lives. However, it does not account for the full magnitude of these psychological changes. For example, there is most likely a difference between the impact changing shampoo brand has on one's life compared to, for example, a breakdown in a relationship. Furthermore, different participants could perceive the same change as being of different magnitude. The present study did not aim to measure the magnitude of each change; however, it demonstrates the need for magnitude to be addressed in future research to further specify and address the psychological changes through participation in collective action, by, for example, asking participants to rate the impact of the change on their lives over time.

A limitation of this study, as many studies of collective action and psychological change, was the lack of pre‐participation data due to the unpredictable nature of collective action, making it difficult finding participants before they know that they will participate. There are some further limitations; the sales records gathered from the shops have the advantage of being behavioural and longitudinal, but cannot be linked to the specific participants who were interviewed. Further, we use ‘level of activity’ as an indicator of ‘support’ and ‘communication’ in the quantitative analysis. We argue that the inference is reasonable as all participants described ‘activity’ as interacting with others. However, distinct support and communication measures should be used to further explore the relationship between intragroup interaction and sustained psychological changes. Finally, whether the mediation model offered here is true for all types of changes through all types of collective actions, such as non‐policed collective actions where there could be a vicarious perceived conflictual intergroup relation with non‐participating outgroups such as large companies, still needs to be examined.

Conclusion

The analysis presented in this paper suggests how intergroup interaction function as a catalyst for psychological changes, for example, in consumer behaviour and consumption attitudes, and by altering the intragroup interaction also affects the endurance of the changes beyond the immediate struggle. Intragroup interaction was shown to be the key factor in sustaining changes such as consumer behaviour. The study extends the field by adopting a longitudinal design enabling the analysis of process and endurance of psychological change through participation in collective action. Future research needs to explore the sustainability of the suggested mediation model on other types of change and other campaigns.

Because the 2nd author of this paper is an editor of this journal, they were blinded throughout all stages of the submission and review process.

Footnotes

The participants are identified by a letter, A for activists and L for locals, along with a number, for example, A1, A14, L1, and L14.

Collecting thrown‐away food in dumpsters/skips outside shops.

References

- Attride‐Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1, 385–405. 10.1177/146879410100100307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barr, D. , & Drury, J. (2009). Activist identity as a motivational resource: Dynamics of (dis)empowerment at the G8 direct actions, Gleneagles, 2005. Social Movement Studies, 8, 243–260. 10.1080/14742830903024333 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J. , & Tausch, N. (2015). A dynamic model of engagement in normative and non‐normative collective action: Psychological antecedents, consequences, and barriers. European Review of Social Psychology, 26, 43–92. 10.1080/10463283.2015.1094265 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood, L. , & Louis, W. (2012). If it matters for the group then it matters to me: Collective action outcomes for seasoned activists. British Journal of Social Psychology, 51, 72–92. 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehnke, K. , & Boehnke, M. (2005). Once a peacenik–always a peacenik? Results from a German six‐wave, twenty‐year longitudinal study. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 11, 337–354. 10.1207/s15327949pac1103_7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boehnke, K. , & Wong, B. (2011). Adolescent political activism and long‐term happiness: A 21‐year longitudinal study on the development of micro‐ and macrosocial worries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 435–447. 10.1177/0146167210397553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cable, S. (1992). Women's social movement involvement: The role of structural availability in recruitment and participation processes. The Sociological Quarterly, 33, 35–50. 10.1111/j.1533-8525.1992.tb00362.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Masso, A. , Dixon, J. , & Pol, E. (2011). On the contested nature of place: ‘Figuera's Well’, ‘The Hole of Shame’ and the ideological struggle over public space in Barcelona. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31, 231–244. 10.1016/j.jenvp.2011.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, J. (2001). Contact and boundaries. ‘Locating’ the social psychology of intergroup relations. Theory & Psychology, 11, 587–608. 10.1177/0959354301115001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drury, J. , Cocking, C. , & Reicher, S. (2009). Everyone for themselves? A comparative study of crowd solidarity among emergency survivors. British Journal of Social Psychology, 48, 487–506. 10.1348/014466608X357893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury, J. , & Reicher, S. (2000). Collective action and psychological change: The emergence of new social identities. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 579–604. 10.1348/014466600164642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury, J. , & Reicher, S. (2005). Explaining enduring empowerment: A comparative study of collective action and psychological outcomes. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 35–58. 10.1002/ejsp.231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drury, J. , & Reicher, S. (2009). Collective psychological empowerment as a model of social change: Researching crowds and power. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 707–725. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01622.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drury, J. , Reicher, S. , & Stott, C. (2003). Transforming the boundaries of collective identity: From the ‘local’ anti‐road campaign to ‘global’ resistance? Social Movement Studies, 2, 191–212. 10.1080/1474283032000139779 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drury, J. , & Stott, C. (2001). Bias as a research strategy in participant observation: The case of intergroup conflict. Field Methods, 13, 47–67. 10.1177/1525822X0101300103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fendrich, J. , & Lovoy, K. (1988). Back to the future: Adult behaviour of former student activists. American Sociological Review, 53, 780–784. 10.2307/2095823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franz, C. , & McClelland, D. (1994). Lives of women and men active in the social protests of the 1960s: A longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(1), 196–205. 10.1037/0022-3514.66.1.196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, E. (2009). External pressure and local mobilization: Transnational activism and the emergence of the Chinese labor movement. Mobilization, 14, 199–218. https://doi.org/10.17813/1086-671X-23-2-135 [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, E. (1990). Sacrifice for the cause: Group processes, recruitment, and commitment in a student social movement. American Sociological Review, 55, 243–254. 10.2307/2095630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, N. , & Dixon, J. (2006). Space, place, and identity: Issues for political psychology. Political Psychology, 27, 173–185. 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00001.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King, M. , & Bruner, G. (2000). Social desirability bias: A neglected aspect of validity testing. Psychology and Marketing, 17(2), 79–103. 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(200002)17:2%3c79:AID-MAR2%3e3.0.CO;2-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klandermans, B. , Sabucedo, J. , Rodriguez, M. , & de Weerd, M. (2002). Identity processes in collective action participation: Farmers’ identity and farmers’ protest in the Netherlands and Spain. Political Psychology, 23, 235–251. 10.1111/0162-895X.00280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, R. , & Barton, S. (1980). Sex roles in social movements: A case study of the tenant movement in New York City. Signs, 6, 230–247. 10.1086/493794 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LeCompte, M. , & Goetz, J. (1982). Problems of reliability and validity in ethnographic research. Review of Educational Research, 52(1), 31–60. 10.3102/00346543052001031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levine, M. , & Thompson, K. (2004). Identity, place, and bystander intervention: Social categories and helping after natural disasters. The Journal of Social Psychology, 144, 229–245. 10.3200/SOCP.144.3.229-245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis, W. , Amiot, C. , Thomas, E. , & Blackwood, L. (2016). The “activist identity” and activism across domains: A multiple identities analysis. Journal of Social Issues, 72, 242–263. 10.1111/josi.12165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Louis, W. , Thomas, E. , McGarty, C. , Amiot, C. E. , Moghaddam, F. M. , Rach, T. , … Rhee, J. (2017, July). Predicting variable support for conventional and extreme forms of collective action after success and failure. Paper presented at 18th General Meeting of the European Association of Social Psychology, Granada. 221/21002

- Macgillivray, I. (2005). Shaping democratic identities and building citizenship skills through student activism: México's first Gay‐Straight Alliance. Equity & Excellence in Education, 38, 320–330. 10.1080/10665680500299783 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marwell, G. , Aiken, M. , & Demerath, N. (1987). The persistence of political attitudes among 1960s civil rights activists. Public Opinion Quarterly, 51, 359–375. 10.1086/269041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAdam, D. (1989). The biographical consequences of activism. American Sociological Review, 54, 744–760. 10.1002/9780470674871.wbespm013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nassi, A. , & Abramowitz, S. (1979). Transition or transformation? Personal and political development of former Berkeley Free Speech Movement activists. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 8(1), 21–35. 10.1007/BF02139137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Profitt, N. (2001). Survivors of woman abuse: Compassionate fires inspire collective action for social change. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 11, 77–102. 10.1300/j059v11n02_05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reicher, S. (1996). ‘The Battle of Westminster’: Developing the social identity model of crowd behaviour in order to explain the initiation and development of collective conflict. European Journal of Social Psychology, 26, 115–134. 10.1002/(sici)1099-0992(199601)26:1%3c115::aid-ejsp740%3e3.0.co;2-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reicher, S. , Hopkins, N. , & Harrison, K. (2006). Social identity and spatial behaviour: The relationship between national category salience, the sense of home, and labour mobility across national boundaries. Political Psychology, 27, 247–263. 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00005.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salt, C. , & Layzell, J. (1985). Here we go! Women's memories of the 1984/85 miners’ strike. London, UK: Co‐operative Retail Services. [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat, D. (1998). Counterculture or continuity? Competing influences on baby boomers’ religious orientations and participation. Social Forces, 76, 1087–1115. 10.1093/sf/76.3.1087 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat, D. , & Blocker, J. (1997). Explaining the political and personal consequences of protest. Social Forces, 75, 1049–1076. 10.1093/sf/75.3.1049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shriver, T. , Miller, A. , & Cable, S. (2003). Women's work: Women's involvement in the Gulf War illness movement. The Sociological Quarterly, 44, 639–658. 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2003.tb00529.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stott, C. , & Reicher, S. (1998). Crowd action as intergroup process: Introducing the police perspective. European Journal of Social Psychology, 26, 509–529. 10.1002/(sici)1099-0992(199807/08)28:4%3c509::aid-ejsp877%3e3.0.co;2-c [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, A. , Thomas, E. , Donaghue, N. , & Russell, A. (2013). ‘We may be pirates, but we are not protesters’: Identity in the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. Political Psychology, 34, 753–777. 10.1111/pops.12016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swann, W. , & Buhrmester, M. (2014). Identity fusion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24, 52–57. 10.1177/0963721414551363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swann, W. , Gómez, A. , Seyle, C. , Morales, F. , & Huici, C. (2009). Identity fusion: The interplay of personal and social identities in extreme group behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 995–1011. 10.1037/a0013668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J. (2011). The intimate insider: Negotiating the ethics of friendship when doing insider research. Qualitative Research, 11, 3–22. 10.1177/1468794110384447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, E. , & McGarty, C. (2009). The role of efficacy and moral outrage norms in creating the potential for international development activism through group‐based interaction. British Journal of Social Psychology, 48, 115–134. 10.1348/014466608X313774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, E. , McGarty, C. , & Louis, W. (2014). Social interaction and psychological pathways to political extremism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 44, 15–22. 10.1002/ejsp.1988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, E. , McGarty, C. , & Mavor, K. (2009). Aligning identities, emotions, and beliefs to create commitment to sustainable social and political action. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13, 194–218. 10.1177/1088868309341563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zomeren, M. , Leach, C. , & Spears, R. (2012). Protesters as “passionate economists”: A dynamic dual pathway model of approach coping with collective disadvantage. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16, 180–199. 10.1177/1088868311430835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestergren, S. , Drury, J. , & Hammar Chiriac, E. (2017). The biographical consequences of protest and activism: A systematic review and a new typology. Social Movement Studies, 16, 203–221. 10.1080/14742837.2016.1252665 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vestergren, S. , Drury, J. , & Hammar Chiriac, E. (2018). How participation in collective action changes relationships, behaviours, and beliefs: An interview study of the role of inter‐ and intragroup processes. (Unpublished manuscript)

- Willig, C. (2008). Introducing qualitative research in psychology. Adventures in theory and method. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]