Background/Objective

Sexual double standard (SDS) has long been associated to several dimensions of sexual health. Therefore the assessment of SDS is relevant and requires self-reported measures with adequate psychometric properties. This study aims to adapt the Sexual Double Standard Scale (SDSS) into heterosexual Spanish population and examine its psychometric properties. Method: Using quota incidental sampling, we recruited a sample of 1,206 individuals (50% women), distributed across three groups based on their age (18-34, 35-49 and 50 years old and older). Results: We performed both, Exploratory Factor Analysis and Confirmatory Factor Analysis. An abridged version was yielded, consisting of 16 items distributed into two factors (Acceptance for sexual freedom and Acceptance for sexual shyness). A second-order factor structure was also adequate, which facilitates the use of a global index for SDS. Reliability, based on internal consistency and temporal stability was good for the factors. Evidence of validity is also shown and reported. Conclusions: This adapted version of the SDSS is reliable and valid. The importance for its use to estimate the prevalence of both traditional and modern forms of this phenomenon is discussed.

Keywords: Sexual double standard, Sexual Double Standard Scale, Reliability, Validity, Instrumental study

Resumen

Antecedentes/Objetivo

El doble estándar sexual (DES) se ha asociado a distintas dimensiones de la salud sexual, por lo que su evaluación es relevante y requiere de instrumentos con adecuadas propiedades psicométricas. Se plantea la adaptación a población heterosexual española de la Sexual Double Standard Scale (SDSS) y examinar sus propiedades psicométricas. Método: Mediante un muestreo incidental por cuotas se obtuvo una muestra de 1.206 sujetos (50% mujeres), distribuidos en tres grupos en función de la edad (18-34 años, 35-49 años y 50 años o más). Resultados: Mediante Análisis Factorial Exploratorio y Análisis Factorial Confirmatorio se consiguió una versión de 16 ítems distribuidos en dos factores (Aceptación de la libertad sexual y Aceptación del recato sexual), cuya combinación en un factor de segundo orden permite obtener un índice global de doble estándar sexual. La fiabilidad de consistencia interna y test-retest es óptima para los dos subfactores y sus medidas presentan adecuados índices de validez. Conclusiones: Esta versión adaptada de la SDSS es fiable y válida. Se discute su importancia para detectar la prevalencia de DES tradicional y de expresiones más modernas de este fenómeno.

Palabras clave: Doble estándar sexual, Sexual Double Standard Scale, fiabilidad, validez, estudio instrumental

The Sexual Double Standard (SDS) refers to the social rewarding and praise that men receive, not women, when they are sexually active in their heterosexual interactions (Fasula et al., 2014, Milhausen and Herold, 2002). Individuals with a greater endorsement of traditional SDS assume more sexual freedom to men than to women in some contexts and related to sexual behaviors (e.g., sex before marriage, sex with multiple sexual partners, sexual debut at early ages, casual relationships without commitment, or playing an active role in sex). On the other hand, less adhesion to SDS leads to a greater acceptance of equality between both sexes (Crawford and Popp, 2003, García-Cueto et al., 2015, Sierra et al., 2007).

A better knowledge regarding the prevalence of SDS is of interest in both clinical and psychosocial viewpoints. Previous research has shown that SDS is associated with sexual victimization (Eaton and Matamala, 2014, Sierra et al., 2014a, Sierra et al., 2011), sexual aggression (Eaton and Matamala, 2014, Llor-Esteban et al., 2016, López-Ossorio et al., 2017, Moyano et al., 2017, Sierra et al., 2009), greater risk of sexually transmitted infections (Bermúdez et al., 2010, Bermúdez et al., 2013, Fasula et al., 2014), and lower sexual satisfaction (Haavio-Mannila and Kontula, 2003, Santos-Iglesias et al., 2009).

From a psychosocial viewpoint, it is likely to find a relationship between higher endorsement of SDS and individuals’ predisposition to accept gender inequality. The patriarchal system promotes a masculine structural power (Sidanius, 1993) which establishes which sexual scripts or social representations of sexual behavior are considered normative in a given culture (Simon & Gagnon, 2003), and intrapsychic maps, providing directions about how to feel, think, and behave in particular situations. Individuals determine the type of sexual behaviors that are appropriate according to their own experiences and the assimilation of dominant heterosexual sexual scripts (Simon & Gagnon, 2003). Therefore, in a private sphere, the SDS is a useful mechanism to expand the control and maintenance of patriarchy (Holland, Ramazanoglu, Sharpe, & Thomson, 2004), while the traditional SDS would serve to maintain a dominant paternalism (Glick & Fiske, 2011) through the belief that men must play an active role (vs. a passive women) in sexual encounters. The construct Social Dominance Orientation (SDO; Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994) is defined as an individual characteristic that reflects the degree to which someone desires that his or her own group dominates and be superior over an out-group. Considering that a greater adhesion to SDS indicates a positive attitude towards masculine dominance regarding sexual behaviors, the SDS and SDO should be related. Low scores of SDO are associated with positive attitudes towards equality between men and women (Lippa & Arad, 1999), however, high scores of SDO are associated with negative attitudes towards women's rights (Pratto et al., 1994), hostility toward women (Sibley, Wilson, & Duckitt, 2007), endorsement of traditional gender roles (Christopher & Wojda, 2008), belief that men should initiate sex (Rosenthal, Levy, & Earnshaw, 2012) and that women should tolerate abuse and sexual insinuations without complaining (Russell & Trigg, 2004).

During the last decades, the reported prevalence of SDS has been widely variable. Several explanations could be drawn, such as ideological changes, the use of different methodologies or sociocultural characteristics (Bordini and Sperb, 2013, Crawford and Popp, 2003, Wells and Twenge, 2005). Overall, between 1943 and 1999, sexual behavior and sexual attitudes have become more liberal (Wells & Twenge, 2005). From the 1970s on, in the United States, a unique standard regarding premarital sex has emerged (King, Balswick, & Robinson, 1977). Although in the last decades there is evidence of SDS (see Bordini and Sperb, 2013, Crawford and Popp, 2003), nowadays SDS is expressed by new sexual behaviors such as earlier age for the first intercourse (Ortiz et al., 2011, Peixoto et al., 2016), having a high number of sexual partners (Chi et al., 2015, Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2016) or having a younger sexual partner (Palacios-Ceña et al., 2012, Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2016).

Findings using self-reported measures aimed to distinguish between the individual's perception about society SDS endorsement, and the individual's own endorsement of SDS, revealed that, although most young adults think SDS among society is noteworthy, and relatively stable, the individual's own endorsement of SDS is more susceptible to vary (Milhausen & Herold, 2002). Bordini and Sperb (2013), when referring to the Sexual Double Standard Scale (SDSS; Muehlenhard & Quackenbush, 2011), point out that the variability of this construct could be due to the way respondents tend to answer some of the items, as the respondent may think about SDS given in the society (e. g., “A woman having casual sex is just as acceptable to me as a man having casual sex”), while other items are more likely to measure the acceptance for some sexual behaviors in men and women (e. g., “It's best for a girl to lose her virginity before she's out of her teens”). Therefore, some authors emphasized on using current definitions of the SDS for the appropriate development of self-reported measures (Jonason & Marks, 2009). These recommendations are based in the evidence of some new sexual scripts e.g., discouragement and refusal towards casual sex and without commitment for heterosexual men (Flood, 2013) or in both sexes (Sakaluk, Todd, Milhausen, & Lachowsky, 2014). Finally, Bordini and Sperb (2013) recommend examining SDS among more diverse sample, based on age, social status, education and ethnic background, beyond the overused samples of undergraduate students.

According to Bordini and Sperb (2013), the most highly used standardized self-reported measures to assess SDS are: the SDSS and the Double Standard Scale (DSS; Caron, Davis, Halteman, & Stickle, 1993). The content of parallel items -referring to men and women separately- of the SDSS, differently from the DSS that was adapted to Spanish population by Sierra et al. (2007), enables looking into respondents’ own opinion about the acceptance of some sexual behaviors -liberal vs. shy- in men and women. Answers can be classified as follows: a) individuals who accept a greater sexual freedom for men, b) individuals who support a greater sexual freedom for women, and c) individuals who believe in equal sexual standards between men and women. We consider this classification very useful and parsimonious to evaluate the SDS construct in current sociocultural contexts.

The SDSS consists of 26 items. Six items compare sexual behaviors between men and women (e.g., “A man should be more sexually experienced tan his wife” or “A woman shaving casual sex is just as acceptable to me as a man having casual sex”). The remaining twenty items are grouped into parallel pair of items regarding sexual behavior in men (10) and women (10) (e. g., “It's best for a guy to lose his virginity before he's out of his teens” and “It's best for a girl to lose her virginity before she's out of her teens”). Muehlenhard and Quackenbush (2011) report a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of .73 in women and .76 in men. Other studies have indicated more modest values, about .68 (Boone & Lefkowitz, 2004) or .63 (Lee, Kim, & Lim, 2010). Regarding validity, scores from the SDSS have been associated with more traditional attitudes towards gender roles (Muehlenhard & McCoy, 1991), more conservative sexual attitudes (Boone & Lefkowitz, 2004), with token refusal attitudes or with unwillingness to have sex in women although they are actually ready for sex when they perceive that their partner supports SDS (Muehlenhard & Quackenbush, 2011), and with rape myth acceptance. So far, the factorial structure of the SDSS has not been examined.

Considering that the SDSS is the most widely used measure to evaluate SDS and it is not adapted to the Spanish population, the objective of this instrumental study (Montero & León, 2007) was to investigate the psychometric properties of the Spanish version (factor structure, reliability of internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and some evidence of validity). We tested the following hypotheses:

H1. The SDSS will show an adequate convergent validity with SDS, by positively correlating with the scores from the DSS.

H2. Scores from the SDSS will be positively correlated with social dominance orientation (SDO) or individuals’ predisposition to accept gender inequality and hierarchical relations among social groups (Christopher and Wojda, 2008, Rosenthal et al., 2012, Russell and Trigg, 2004).

H3. Men will obtain higher scores than women in the SDSS, that is, men will agree, to a higher extent, with greater sexual freedom for men than for women (Allison and Risman, 2013, England and Bearak, 2014, Gutiérrez-Quintanilla et al., 2010).

H4. Scores from the SDSS will be positively associated with age (Sprecher, 1989) and negatively with individuals’ education (Sierra, Costa, & Monge, 2012).

Method

Participants

The sample was composed of 1,206 individuals who met the following inclusion criteria: a) being 18 or older; b) Spanish nationality; and c) heterosexual orientation. Participants were recruited from the Spanish general population. A quota convenience sampling method was used to obtain the same number of men and women, distributed across three groups according to age (18-34, 35-49, and 50 years old or older). In order to perform statistical analysis, the sample was randomly divided into two subsamples: Sample 1 (33.33%) and Sample 2 (66.67%). Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of both samples.

Table 1.

Samples sociodemographic characteristics.

| Variables | Sample 1 (n = 402) | Sample 2 (n = 804) | Sample test-retest (n = 103) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 41.69 (13.49) | 41.05 (14.62) | 19.17 (3.69) |

| Range | 18-80 | 18-84 | 18-34 |

| Education (%) | |||

| No studies-Primary Education | 42 (10.45) | 95 (11.82) | |

| Secondary Education | 108 (26.86) | 173 (21.52) | |

| University degree | 252 (62.69) | 536 (66.66) | 103 (100) |

| Mean age at first sexual intercourse (SD) | 18.73 (3.53) | 18.43 (3.31) | 16.23 (1.25) |

| Currently in a relationship (%) | |||

| Yes | 325 (80.85) | 611 (75.99) | 48 (46.60) |

| No | 77 (19.15) | 193 (24.01) | 55 (53.40) |

Furthermore, with the goal to estimate test-retest reliability, we incidentally selected a sample of 103 undergraduate students (85.4% women and 14.6% men), with a mean age of 19.17 years old (SD = 3.69), using the described above inclusion criteria. This group was compared to a sample of 126 undergraduate students who were randomly extracted from the total sample of 1,206 individuals. This group was formed by 75 women (59.5%) and 51 men (40.5%), with a mean age of 19.80 years (SD = 1.04). Both groups were undergraduate students from the University of Granada and they did not differ in relationship status (χ2 1, 228 = .01, p = .906), age of first sexual intercourse (t 193 = -.12, p = .902) or number of sexual partners (t 203 = 1.91, p = .058).

Instruments

Background Questionnaire and Sexual History to obtain information about sex, age, educational level, nationality, sexual orientation, age of first sexual intercourse, and relationship status.

Sexual Double Standard Scale (SDSS; Muehlenhard & Quackenbush, 2011). It consists of 26 items answered in a 4-point Likert scale, which ranges from 0 (disagree strongly) to 3 (agree strongly). Higher scores indicate more acceptance of traditional sexual double standard (greater sexual freedom for men).

Spanish version of the Double Standard Scale (DSS; Caron et al., 1993) from Sierra et al. (2007). It consists of 10 items answered in a 5-point Likert scale: from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). High scores indicate greater adherence to traditional sexual double standard. Internal consistency is equal to .76 in men and .70 in women. Evidence of validity is adequate (see Sierra, Santos-Iglesias, Vallejo-Medina, & Moyano, 2014). For the present study, in Sample 2, Cronbach's alpha was .84.

The Spanish version of the Social Dominance Orientation Scale (SDOS; Pratto et al., 1994) from Silván Ferrero and Bustillos (2007) was used. Its 16 items are answered in a 7-point Likert scale, which ranges from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). Higher scores indicate higher social dominance orientation. Reliability from the original scale was .91 (Pratto et al., 1994). The Spanish version has adequate reliability values (α=.85) (Etchezahar, Prado-Gascó, Jaume, & Brussino, 2014; Silván Ferrero & Bustillos, 2007). In Sample 2, Cronbach's alpha was .78.

Procedure

Guidelines from Elosua, Mujika, Almeida and Hermosilla (2014) were taken into account. As recommended by Muñiz, Elosua, and Hambleton (2013), a forward-translation of the items was conducted from English into Spanish. This was done independently by two human sexual behavior researchers with a high level of English proficiency and an in-depth knowledge of both cultures. When the translations were finished, the two researchers then compared their translations and agreed on a first draft. A bilingual psychologist, who was also expert in sexuality, then evaluated this initial version. Based on a comparison of the original version in English and the Spanish translation, modifications were proposed for 11 of the 26 items. These modifications were integrated into the new version, which was again revised by a panel of experts on the topic, who evaluated the original English version and the modified Spanish translation. These experts evaluated each Spanish item and its degree of equivalence with the corresponding item in the original text. They offered suggestions and, when appropriate, alternative wordings. Thus, when there was not at least 85% agreement in regards to the content comprehension or equivalence of an item, it was changed as suggested by the experts. The Spanish scale was then given to 10 undergraduate students and 10 subjects from the Spanish general population to test whether the items were clearly expressed and understandable. After modifying one of the items, the final version of the scale was obtained.

The participants were recruited among the general Spanish population by means of a nonrandom sampling procedure. Between January and June 2015, the final Spanish version of the SDSS, together with the other two self-reported measures, was administered in pencil and paper format by two evaluators in different universities, social centers and associations. Participants answered the scales, in an individual and private way, and when finished, they handed all the measures in a closed envelope. Some of the respondents, aged between 18 and 54, answered questionnaires available online. The questionnaires were accessible from January until June 2015. The URL of the questionnaires was distributed by means of social networking and by the news service of the University of Granada. No significant differences in the responses to the items from the SDSS were found between both method of recruitment (range of significance from p = .14 to p = .97). The subjects were informed of the purpose of the study, characteristics of the scales, and what their participation entailed. All participants were assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of their answers. The estimated time to complete the questionnaires was 15 minutes.

To calculate the test-retest reliability, the SDSS was administered to university students in their respective classrooms at three different times by one expert researcher. In the first session, after informing the participants of the objectives of the study, its voluntary nature, the confidentiality and anonymity of responses, each participant was given three envelopes and three copies of the questionnaires, along with the informed consent form. All documents had the same code as well as the exact date of the second and third administration (at 4 and 8 weeks, respectively). After answering the scales, the students put them in a sealed envelope and delivered them to the evaluator. The Ethics Committee on Human Research of the University of Granada approved this study.

Results

Exploratory Factorial Analysis (EFA)

Considering recommendations from Neukrung and Fawcett (2014), the sample was randomly divided into two subsamples, one subsample for conducting an EFA and the other subsample for conducting a Confirmatory Factorial Analysis (CFA). In Sample 1 (n = 402), the EFA was performed using FACTOR 10.4. We used the polychoric correlation matrix, and due to the violation of multivariate normality (Mardia's = 53.97), the applied estimation method was Robust Unweighted Least Squares. Confidence interval was estimated using bootstrap sampling with 500 samples. Number of factors was extracted through the Optimal implementation of Parallel Analysis (Timmerman & Lorenzo-Seva, 2011). Rotation was Oblimin. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO = .82) and Bartlett's test of sphericity (χ2 325 = 4740.00, p < .001) indicated the suitability of the data for EFA.

The Parallel Analysis suggested a structure composed by three factors. The first factor was composed of 5 items (7, 17, 20, 23, and 24). This factor comprised items related to virginity and premarital sex. The content of the other two factors was not clearly defined, as some factor loadings were shared between both factors. The first factor could reflect a response bias regarding the content of virginity and premarital sex, as a reflection of the Spanish social context, more than to a theoretical grouping reason. Therefore, we decided to discard items 7 (“I kind of feel sorry for a 21-year-old woman who is still a virgin”), 17 (“I kind of feel sorry for a 21-year-old man who is a still a virgin”), and 24 (“It's best for a girl to lose her virginity before she's out of her teens”) that had exclusively weights in this factor. Thus, the EFA was again performed. From this analysis, a two-factor structure was advised. Item 4 (“It is just as important for a man to be a virgin when he marries as it is for a woman”) -also related to virginity before marriage – did not load in any of the factors and items 2 (again related to virginity: “It's best for a guy to lose his virginity before he's out of his teens”), 5 (“I approve of a 16-year-old girl's having sex just as much as a 16-year-old boy's having sex”) and 8 (“A woman's having casual sex is just as acceptable to me as a man's having casual sex”) yielded similar factor loadings (a difference lower than .15) in both factors. After reviewing the psychometric properties of these items and their theoretical adequacy, we decided to discard these items from the analysis and to perform another EFA. Again, two factors were observed with a total explained variance of 52.73%. As can be seen in Table 2, all factor loadings in their factors were higher than .30 in their inferior Confidence Interval (CI 95%). All the items, except items 14 and 25, were clearly positioned in one of the factors (Acceptance for sexual freedom and Acceptance for sexual shyness) with differences in their factor loadings higher than .15. Although elimination of items 14 and 25 was considered, they were not discarded. Rather, we proceeded to confirm the dimensionality of the scale.

Table 2.

Secondary factor loadings for the SDSS items obtained from EFA.

| Item | Acceptance for sexual freedom | Acceptance for sexual shyness |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | .69 (.58 to .80) | |

| 3 | .71 (.62 to .80) | |

| 6 | .70 (.61 to .79) | |

| 9 | .69 (.57 to .76) | |

| 10 | .81 (.71 to .89) | |

| 11 | .65 (.54 to .75) | |

| 12 | .80 (.72 to .87) | |

| 13 | .76 (.69 to .84) | |

| 14 | -.39 (-.53 to -.28) | .39 (.22 to .49) |

| 15 | .79 (.70 to .91) | |

| 16 | .64 (.50 to .72) | |

| 18 | .62 (.50 to .71) | |

| 19 | .45 (.32 to .58) | |

| 20 | .59 (.40 to .73) | |

| 21 | .59 (.46 to .70) | |

| 22 | .66 (.55 to .73) | |

| 23 | .50 (.32 to .65) | |

| 25 | -.42 (-.53 to -.32) | .45 (.33 to .57) |

| 26 | .61 (.52 to .71) | |

| % explained variance | 38.06% | 14.67% |

Note. 95% Confidence intervals are shown in brackets. Values under .30 in the lower confidence interval limit are omitted. Bold indicates items that are included in final factor scores.

Confirmatory Factorial Analysis (CFA)

Using data from Sample 2 (n = 804), we examined whether some models based on the two-factor structure previously explored would be ratified. Also, in this subsample, data did not follow a multivariate normal distribution (Mardia's = 66.35), therefore a robust method was used: Maximum Likelihood, Robust (ML, R) and again the polychoric matrix was analyzed. Some fit indexes were used to assess the models, including the ratio of Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square to degrees of freedom (S-Bχ2/df), the Non-Normed Fit Index or NNFI, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and its Confidence Interval (CI 90%). CFIs and TLIs greater than .95 (Hu & Bentler, 1999) would indicate a good fit. Regarding RMSEA, values less than .06 indicate a good fit (Byrne, 2014, Hu and Bentler, 1999). Finally a < .08 for the SRMR is considered as indicator of good model (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Analyses were run with EQS 6.1.

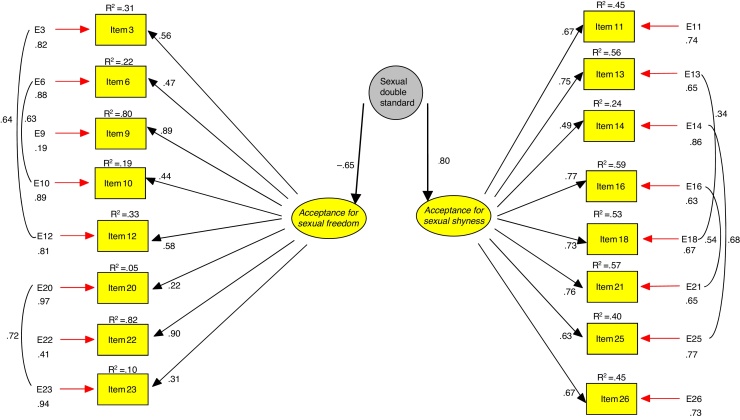

The first model tested was the one finally extracted from the EFA, that is, items 1, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 21, 25 and 26 (factor Acceptance for sexual shyness) and items 3, 6, 9, 10, 12, 20, 22 and 23 (factor Acceptance for sexual freedom). This model showed a poor fit considering some of the indexes: S-Bχ2 = 735.82 with 142 degrees of freedom (p < .01); RMSEA = .072 (.067 to .077), SRMR = .072, NNFI = .94 and CFI = .95. Two out of three fit indexes were below the standard cut off (RMSEA and NNFI). These results were close to be acceptable, however we preferred to search for a better model. Thus, we tested a second model, and we considered the Lagrange multiplier test, which suggested items 1, 15, and 19 should be changed from one factor to another. However, theoretically, the loading of these items in the other factor was not clearly coherent, therefore these items were discarded. Moreover, both factors were covariated, as well as the errors from six pair of items, that were identically written for both men and women (item 20 and 23 were paired, as well as item 14 and 25, items 3 and 12, items 6 and 10, items 16 and 21, and items 13 and 18). After this modification, an optimum fit was obtained considering all indicators. A S-Bχ2 = 332.74 with 95 degrees of freedom (p < .01). The fit indexes such as RMSEA = .056 (CI 90% = .049 to .062), SRMR = .067, NNFI = .96 and CFI = .97 provided a good fit. In addition, considering that it is important to have a global score from the scale, we tested a model replicating previous dimensionality, including a second-order factor. This model also showed a good fit: S-Bχ2 = 429.53 with 114 degrees of freedom (p < .01), with a ratio of 3.7. Also, fit indexes were for RMSEA = .050 (CI 90% = .045 to .056), SRMR = .069, NNFI = .97 and CFI = .97. In Figure 1, the standardized values for the last model can be observed, in which all the items, except item 20, loaded more than .30 in their corresponding factor. This item was kept into the model considering its appropriate psychometric properties.

Figure 1.

Two related factors path diagram with a second order factor. Standardized weights are shown.

Psychometric properties of the items and reliability

For all the items, the range of respondent scores oscillated between 0 and 3, thus, all the answer scores were chosen at least once. Mean scores for all items were slightly lower than the theoretical mean of the scale (1.5) and standard deviations were closed to 1, indicating an adequate distribution of responses. As can be seen in Table 3, all the items have a corrected item-total correlation over .30. The elimination of none of the items would improve Cronbach's ordinal alpha for its subscale. Cronbach's ordinal alpha for subscale Acceptance for sexual freedom was .84, and for subscale Acceptance for sexual shyness was .87. The factor Acceptance for sexual freedom reached higher scores than factor Acceptance for sexual shyness.

Table 3.

Item psychometric properties.

| M (SD) | Corrected item-total correlation | Ordinal Cronbach's alpha if item deleted* | Ordinal Cronbach's alpha* | Total M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptance for sexual freedom | .84 | 11.20 (4.81) | |||

| Item 3 | 0.93 (0.92) | .53 | .82 | ||

| Item 6 | 1.13 (0.87) | .54 | .81 | ||

| Item 9 | 1.85 (0.89) | .62 | .81 | ||

| Item 10 | 1.14 (0.86) | .52 | .81 | ||

| Item 12 | 1.00 (0.90) | .56 | .81 | ||

| Item 20 | 1.68 (0.99) | .36 | .84 | ||

| Item 22 | 1.74 (0.94) | .60 | .82 | ||

| Item 23 | 1.73 (0.97) | .40 | .84 | ||

| Acceptance for sexual shyness | .87 | 6.44 (4.75) | |||

| Item 11 | 0.63 (0.77) | .47 | .86 | ||

| Item 13 | 0.73 (0.81) | .60 | .84 | ||

| Item 14 | 0.79 (.90) | .49 | .87 | ||

| Item 16 | 1.08 (1.00) | .66 | .85 | ||

| Item 18 | 0.79 (0.83) | .59 | .84 | ||

| Item 21 | 0.93 (0.94) | .64 | .85 | ||

| Item 25 | 0.92 (0.94) | .58 | .86 | ||

| Item 26 | 0.57 (0.66) | .49 | .85 | ||

Note. M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation

Calculated based on the 1,206 subjects database.

To examine the temporal stability of this version, Pearson's correlation coefficient was used. Between the first time of data collection (T1) and the second (T2) a 4-week period mediated both times, and the third collection (T3) was conducted after 8-weeks from T1. Overall, test-retest reliabilities were good for Acceptance for sexual freedom and Acceptance for sexual shyness: correlation coefficients over .70 (Table 4). We also used repeated measures ANOVA to examine differences across the three time points. Multivariate analysis revealed no significant effect of time for either Factor 1 [F (2, 192) = 1.16, p = .315] or Factor 2 [F (2, 192) = .27, p = .759].

Table 4.

Four and eight-week test-retest reliability of the abridged version of the SDSS.

| Time 1-Time 2 (4 weeks) | Time 1-Time 3 (8 weeks) | |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptance for sexual freedom | .78*** | .71*** |

| Acceptance for sexual shyness | .75*** | .71*** |

Note. n = 106 (Time 1), n = 102 (Time 2), n = 98 (Time 3)

p < .001.

Evidence of validity

In order to report evidence of validity from both factors and the global score from the SSDS as measures of sexual double standard, we calculated the indexes for each subscale. Regarding the first factor, we obtained the Index of Double Standard for Sexual Freedom (IDS-SF) through the following computation: (Item 9 + Item 10 + Item 12 + Item 20) – (Item 3 + Item 6 + Item 22 + Item 23); and for the second factor, we calculated the Index of Double Standard for Sexual Shyness (IDS-SS) through: (Item 11 + Item 13 + Item 16 + Item 25) – (Item 14 + Item 18 + Item 21 + Item 26). The sum of both indexes provides the Global Index for Sexual Double Standard (GI-SDS). Numbers given to these items correspond to the number provided in the original scale.

As for the convergent validity of this version, Pearson's correlations were computed among IDS-SF, IDS-SS, GI-SDS, DSS, and SDO measures. All indexes of sexual double standard positively correlated with DSS and SDO (see Table 5). Therefore, greater endorsement of traditional sexual standard (IDS-SF) and greater adhesion to double standard regarding sexual shyness (IDS-SS) is positively related to sexual double standard (DSS) and, to a lesser degree, with social dominance orientation (SDO).

Table 5.

Zero-order correlations between the indexes from the SDSS, and scores from DSS and SDO (n = 804).

| IDS-SS | GI-SDS | DSS | SDO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. IDS-SF | .38*** | .83*** | .35*** | .21*** |

| 2. IDS-SS | .82*** | .36*** | .18*** | |

| 3. GI-SDS | .43*** | .23*** | ||

| 4. DSS | .42*** |

Note. IDS-SF: Index of Double Standard for Sexual Freedom; IDS-SS: Index of Double Standard for Sexual Shyness; GI-SDS: Global Index of Sexual Double Standard; DSS: Double Standard Scale; SDO: Social Dominance Orientation

p < .001.

We performed ANOVA to examine differences in the mean scores of the indexes for sexual double standard through the groups created from the sociodemographic variables (sex, age group, and education) (Table 6). Significant differences by sex were found in IDS-SF (F(1, 802) = 46.23; p < .001), IDS-SS (F(1, 802) = 42.05; p < .001) and GI-SDS (F(1, 802) = 65.44, p < .001). For all indexes, men reported to endorse greater sexual double standard. No significant differences were found in the indexes considering groups by age. Regarding education, significant differences were shown in IDS-SF [F(2, 798) = 5.20; p = .006), IDS-SS [F(2, 798) = 6.74; p = .001] and GI-SDS [F(2, 798) = 8.48; p = .000]. Post hoc comparisons through Bonferroni test indicated scores in SDS significantly lower for individuals with university degree.

Table 6.

Difference in the average scores of the SDSS in terms of sex, age and education level (n = 804).

| Variable | Groups | n | M | SD | F | df | p | d/η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDS-SF | ||||||||

| Sex | Male Female |

402 402 |

0.54 -0.27 |

1.87 1.56 |

46.23 | 1, 802 | .000 | 0.47 |

| Age | 18-34 y. 35-49 y. 50-84 y. |

268 268 268 |

0.00 0.14 0.26 |

1.78 1.74 1.79 |

1.50 | 2, 801 | .223 | 0.00 |

| Education | No studies-Primary Education Secondary Education University studies |

94 172 535 |

0.65 0.18 0.02 |

2.02 1.72 1.73 |

5.20 | 2, 798 | .006 | 0.01 |

| IDS-SS | ||||||||

| Sex | Male Female |

402 402 |

0.72 -0.05 |

1.90 1.45 |

42.05 | 1, 802 | .000 | 0.45 |

| Age | 18-34 y. 35-49 y. 50-84 y. |

269 269 269 |

0.22 0.24 0.54 |

1.56 1.63 1.97 |

2.89 | 2, 801 | .056 | 0.00 |

| Education | No studies-Primary Education Secondary Education University studies |

94 172 535 |

0.85 0.50 0.19 |

2.41 1.98 1.48 |

6.74 | 2, 798 | .001 | 0.01 |

| GI-SDS | ||||||||

| Sex | Male Female |

402 402 |

1.27 -0.32 |

3.22 2.32 |

65.44 | 1, 802 | .000 | 0.56 |

| Age | 18-34 y. 35-49 y. 50-84 y. |

267 267 267 |

0.22 0.38 0.81 |

2.68 2.69 3.32 |

2.90 | 2, 801 | .055 | 0.00 |

| Education | No studies-Primary Education Secondary Education University studies |

94 172 535 |

1.51 0.68 0.22 |

3.89 3.12 2.60 |

8.48 | 2, 798 | .000 | 0.02 |

Note. M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation; IDS-SF: Index of Double Standard for Sexual Freedom; IDS-SS: Index of Double Standard for Sexual Shyness; GI-SDS: Global Index of Sexual Double Standard.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to adapt to the heterosexual Spanish population and examine the psychometric properties of the SDSS, a self-reported measure widely used for the assessment of sexual double standard (Bordini & Sperb, 2013). No previous research has analyzed its factorial structure; therefore this was the first goal. As a result from the Exploratory Factor Analysis, a two-factor structure was yielded, that, after some modifications, showed a good fit by a Confirmatory Factor Analysis, which was performed on a second sample. The two-factor structure distinguishes items referred to acceptance of sexual freedom of both men and women, from items related to the acceptance of sexual shyness in both sexes. Both factors are likely to be combined in a second-order factor, which allows the use of a global score. Two factors reached good reliability values, as internal consistency (.84 and .87, respectively) and as a temporal stability (correlation values over .70 for both subscales) after a 4-week and 8-week period. The greatest contribution of this Spanish adaptation, in comparison to the original version, is the reduction of items, from 26 to 16, which significantly improves its reliability, from .73 (in men) and .76 (in women) from the original version (Muehlenhard & Quackenbush, 2011).

Also, the two-factor structure improves its construct validity, thus it overcomes some inconveniences from the original version, already flagged by Bordini and Sperb (2013), when stating that the SDSS actually assessed two constructs: respondent perception regarding double standard and respondent opinion about whether some sexual behaviors are appropriate in men and women. Our interpretation is that both constructs correspond to mixed and parallel items respectively. The content of the items from the reduced version in Spanish vanishes this construct ambiguity, as Factor 1 and Factor 2 are composed by parallel items, and thus they exclusively explore respondent opinion about whether some sexual behaviors in men and women are appropriate.

For both factors, Acceptance for sexual freedom and Acceptance for sexual shyness, some indexes can be calculated, based on the difference between the scores from the items related to men, and the items related to women. Scores from the Index of Sexual Double Standard of Sexual Freedom (ISD-SF) range from -12 (inverted sexual double standard: that is more sexual freedom for women than for men) and + 12 (traditional sexual double standard: in favor of sexual freedom for men than for women). Scores from the Index of Sexual double Standard of Sexual Shyness also oscillate from -12 (modern sexual double standard in favor of more sexual shyness in men than in women) and + 12 (modern sexual double standard in favor of sexual shyness in women than in men). The sum of both indexes provides a Global Index of Sexual double Standard, whose score ranges from -24 (sexual double standard in favor of women) and + 24 (sexual double standard in favor of men). Both indexes are relatively independent, considering the correlation between them (r = .38)

The abridged version of the SDSS will allow to estimate, specifically, the prevalence, not only from the traditional SDS, but from other demonstrations of the SDS, modern or particular from other occidental societies. The traditional SDS consists on the biased assessment of the demonstration of sexual behaviors, which assume more sexual freedom in men than in women (Fasula et al., 2014, Milhausen and Herold, 2002). The factor Acceptance for sexual freedom, because it evaluates the respondent opinion regarding whether some behaviors endorsing sexual freedom are appropriate in men and in women, once some items related to women are reversed, leads to the measurement of sexual double standard. The factor Acceptance for sexual shyness, which assesses respondent opinion regarding whether some sexual behaviors denote sexual shyness, is appropriate in men and women, facilitates, once items referred to men are reversed, and evaluates SDS based on a modern sexual standard, because it refers to sexual behaviors congruent with occidental societies, which endorse egalitarian gender beliefs. This interpretation is founded in the evidence that new heterosexual scripts are turned towards changes to more conservative postures (Allison & Risman, 2013; Sakaluk et al., 2014) through encouraging a negative appraisal of both men and women, when they behave in a sexually explicit manner, promiscuously or as highly sexually experienced. According to Fasula et al. (2014), these new sexual scripts can constitute a frame for a modern/contemporary sexual double standard (as opposite from the traditional one), which is characterized by the acceptance of shyness and conservative postures as more appropriate for women than for men.

Evidence of validity supports two indexes for SDS, as well as the use of a global score. Convergent validity from the global score of both measures: SDSS and the Sexual Double Standard show a positive correlation coefficient, as expected, although modest. Similarly, as hypothesized, the three indexes of SDS (in the context of sexual freedom, sexual shyness, and the global index of the SDS), are positively associated with social dominance orientation, which emphasizes the link between SDO and negative attitudes towards women's rights (Pratto et al., 1994), hostility toward women (Sibley et al., 2007), endorsement of traditional gender roles (Christopher & Wojda, 2008), or belief that men should initiate sex (Rosenthal et al., 2012). Regarding gender differences, men reach greater scores throughout the three indexes, that is, in comparison to women, they are more prone to endorse higher sexual freedom for men, higher sexual shyness for women, and overall, a greater double standard which benefits them. This finding ratifies the validity of the measures, as these gender differences have been largely shown when using other self-reported measures (Allison and Risman, 2013, England and Bearak, 2014, Gutiérrez-Quintanilla et al., 2010). Regarding age, even though differences were not statistically significant, a trend in the expected direction is observed, thus, as the age increases, higher scores are shown by the three indexes. Finally, education was associated with SDS in the expected direction, thus individuals with greater education degrees, report lower levels of SDS, as data from Brazilian and Peruvian women by Sierra et al. (2012) has previously shown.

Shortly, this abridged version of the SDSS adapted into the Spanish population, shows adequate psychometric properties, which makes this self-reported measure a valid and reliable instrument for the assessment of sexual double standard, both traditional and modern. Some limitations are noted. That is, although participants do differ in their sociodemographic characteristics regarding age and education, the sample is not representative of the Spanish population, therefore generalization from these results should be cautious. This caution should be greater regarding test-retest reliability, as findings are obtained from a reduced sample of undergraduate students, and mostly composed by women. Future studies, including more diverse samples, should also provide standard scores for the scale, and also examination of response bias based on sex, in order to show whether the scale remains invariant for both genders, making the SDSS a more robust self-reported measure (Rodríguez-Díaz et al., 2017).

Funding

This study was funded through a research project granted by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad of Spain [grant number PSI2014-58035-R]. The authors express their gratitude to Virgilio Ortega for his contribution during the first phase of this study, through sample recruitment and creation of the database.

Appendix. The abridged Spanish version of the SDSS.

0 = Disagree strongly 1 = Disagree mildly 2 = Agree mildly 3 = Agree strongly

| 1 | (3) It's okay for a woman to have more than one sexual relationship at the same time (Está bien que una mujer compagine más de una relación sexual al mismo tiempo) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | (6) I kind of admire a girl who has had sex with a lot of guys (Siento cierta simpatía por una chica que ha tenido relaciones sexuales con muchos chicos) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | (9) It's okay for a man to have sex with a woman he is not in love with (Está bien que un hombre tenga relaciones sexuales con una mujer de la que no está enamorado) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | (10) I kind of admire a guy who has had sex with a lot of girls (Siento cierta simpatía por un chico que ha tenido relaciones sexuales con muchas chicas) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 5 | (11) A woman who initiates sex is too aggresive (Una mujer que toma la iniciativa sexual es demasiado atrevida) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 6 | (12) It's okay for a man to have more tan one sexual relationship at the same time (Está bien que un hombre compagine más de una relación sexual al mismo tiempo) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 7 | (13) I question the character of a woman who has had a lot of sexual partners (Pongo en duda el carácter de una mujer que ha tenido muchas parejas sexuales) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 8 | (14) I admire a man who is a virgin when he gets married (Admiro a los hombres que llegan vírgenes al matrimonio) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 9 | (16) A girl who has sex on the first date is “easy” (Una chica que tiene relaciones sexuales en la primera cita es una chica “fácil”) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 10 | (18) I question the character of a man who has had a lot of sexual partners (Pongo en duda el carácter de un hombre que ha tenido muchas parejas sexuales) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 11 | (20) A man should be sexually experienced when he gets married (Un hombre debería tener experiencia sexual antes de casarse) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 12 | (21) A guy who has sex on the first date is “easy” (Un chico que tiene relaciones sexuales en la primera cita es un chico “fácil”) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 13 | (22) It's okay for a woman to have sex with a man she is not in love with (Está bien que una mujer tenga relaciones sexuales con un hombre del que no está enamorada) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 14 | (23) A woman should be sexually experienced when she gets married (Una mujer debería tener experiencia sexual antes de casarse) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 15 | (25) I admire a woman who is a virgin when she gets married (Admiro a las mujeres que llegan vírgenes al matrimonio) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 16 | (26) A man who initiates sex is too aggressive (Un hombre que toma la iniciativa sexual es demasiado atrevido) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Note. Number of the item from the original scale appears in brackets. Score from the Index of Double Standard for Sexual Freedom (IDS-SF) can be obtained by the following computation: Item 3 + Item 4 + Item 6 + Item 11) - (Item 1 + Item 2 + Item 13 + Item 14), with scores ranging from -12 (inverted sexual double standard: in favor of more sexual freedom for women than for men) to + 12 (traditional sexual double standard: in favor of more sexual freedom for men than for women). Scores from the Index of Double Standard for Sexual Shyness (IDS-SS) can be obtained by the following computation: (Item 5 + Item 7 + Item 9 + Item 15) - (Item 8 + Item 10 + Item 12 + Item 16), with scores ranging from -12 (modern sexual double standard in favor of more sexual shyness in men than in women) to + 12 (modern sexual double standard, in favor of more sexual shyness in women than in men). The sum of both indexes provides a Global Index for Sexual Double Standard (GI-SDS), with scores ranging from -24 (sexual double standard beneficial to women) to + 24 (sexual double standard beneficial to men).

References

- Allison R., Risman B.J. A double standard for “Hooking Up”: How far have we come toward gender equality? Social Science Research. 2013;42:1191–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez M.P., Castro A., Gude F., Buela-Casal G. Relationship power in the couple and sexual double standard as predictors of the risk of sexually transmitted infections and HIV: Multicultural and gender differences. Current HIV Research. 2010;8:172–178. doi: 10.2174/157016210790442669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez M.P., Ramiro M.T., Sierra J.C., Buela-Casal G. Construcción de un índice de riesgo para la infección por el VIH y su relación con la doble moral y el poder diádico en adolescentes. Anales de Psicología. 2013;29:917–922. [Google Scholar]

- Boone T.L., Lefkowitz E.S. Safer sex and the health belief model: Considering the contributions of peer norms and socialization factors. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality. 2004;16:51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bordini G.S., Sperb T.M. Sexual double standard: A review of the literature between 2001 and 2010. Sexuality & Culture. 2013;17:686–704. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B. Basic Concepts, Applications and Programming (Multivariate Applications Series) (Reprint Edition) Psychology Press; New Jersey: 2014. Structural Equation Modeling with Lisrel, Prelis, and Simplis. [Google Scholar]

- Caron S.L., Davis C.M., Halteman W.A., Stickle M. Predictors of condom related behaviours among first year college students. Journal of Sex Research. 1993;30:252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Chi X., Bongardt D.V.D., Hawk S.T. Intrapersonal and interpersonal sexual behaviors of Chinese university students: Gender differences in prevalence and correlates. Journal of Sex Research. 2015;52:532–542. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2014.914131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher A.N., Wojda M.R. Social dominance orientation, right-wing authoritarianism, sexism, and prejudice toward women in the work force. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2008;32:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford M., Popp D. Sexual double standards: A review and methodological critique of two decades of research. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:13–26. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton A.A., Matamala A. The relationship between heteronormative beliefs and verbal sexual coercion in college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43:1443. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elosua P., Mujika J., Almeida L.S., Hermosilla D. Procedimientos analítico-racionales en la adaptación de tests. Adaptación al español de la batería de pruebas de razonamiento. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología. 2014;46:117–126. [Google Scholar]

- England P., Bearak J. The sexual double standard and gender differences in attitudes toward casual sex among U.S. university students. Demographic Research. 2014;30:1327–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Etchezahar E., Prado-Gascó V., Jaume L., Brussino S. Validación argentina de la Escala de Orientación a la Dominancia Social. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología. 2014;46:35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Fasula A.M., Carry M., Miller K.S. A multidimensional framework for the meanings of the sexual double standard and its application for the sexual health of young black women in the U.S. Journal of Sex Research. 2014;51:170–183. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.716874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood M. Male and female sluts: Shifts and stabilities in the regulation of sexual relations among young heterosexual men. Australian Feminist Studies. 2013;28:95–107. [Google Scholar]

- García-Cueto E., Rodríguez-Díaz F.J., Bringas-Molleda C., López-Cepero J., Paíno-Quesada S., Rodríguez-Franco L. Development of the Gender Role Attitudes Scale (GRAS) amongst young Spanish people. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2015;15:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick P., Fiske S.T. Ambivalent sexism revisited. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2011;35:530–535. doi: 10.1177/0361684311414832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Quintanilla J.R., Rojas-García A., Sierra J.C. Comparación transcultural de la doble moral sexual entre estudiantes universitarios salvadoreños y españoles. Revista Salvadoreña de Psicología. 2010;1:31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Haavio-Mannila E., Kontula O. Single and sexual double standards in Finland, Estonia, and St. Petersburg. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:36–49. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland J., Ramazanoglu C., Sharpe S., Thomson R. Tufnell; London: 2004. The male in the head: Young people, heterosexuality and power. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.T., Bentler P.M. Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jonason P.K., Marks M.J. Common vs. uncommon sexual acts: Evidence for the sexual double standard. Sex Roles. 2009;60:357–365. [Google Scholar]

- King K., Balswick J.O., Robinson I.E. The continuing premarital sexual revolution among college females. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1977;39:455–459. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Kim J., Lim H. Rape myth acceptance among Korean college: The roles of gender, attitudes toward women, and sexual double standard. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:1200–1223. doi: 10.1177/0886260509340536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippa R., Arad S. Gender, personality, and prejudice: The display of authoritarianism and social dominance in interviews with college men and women. Journal of Research in Personality. 1999;33:463–493. [Google Scholar]

- Llor-Esteban B., García-Jiménez J.J., Ruiz-Hernández J.A., Godoy-Fernández C. Profile of partner aggressors as a function of risk of recidivism. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2016;16:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Ossorio J.J., González Álvarez J.L., Buquerín Pascual S., García Rodríguez L.F., Buela-Casal G. Risk factors related to intimate partner violence police recidivism in Spain. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2017;17:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milhausen R.R., Herold E.S. Reconceptualizing the sexual double standard. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality. 2002;13:63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Montero I., León O.G. A guide for naming research studies in Psychology. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2007;7:847–862. [Google Scholar]

- Moyano N., Monge F.S., Sierra J.C. Predictors of sexual aggression in adolescents: Gender dominance vs. rape supportive attitudes. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context. 2017;9:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenhard C.L., McCoy M.L. Double standard/double bind. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1991;15:447–461. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenhard C.L., Quackenbush D.M. Sexual Double Standard Scale. In: Fisher T.D., Davis C.M., Yarber W.L., Davis S.L., editors. Handbook of sexuality-related measures. 3th ed. Routledge; New York, NY: 2011. pp. 199–201. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz J., Elosúa P., Hambleton R.K. Directrices para la traducción y adaptación de los tests: segunda edición. Psicothema. 2013;25:151–157. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2013.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neukrug E., Fawcett R. Cengage Learning; Stamford, CA: 2014. Essentials of testing and assessment: A practical guide for counselors, social workers and psychologists. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz A.P., Soto-Salgado M., Suárez E., Santos-Ortiz M.C., TortoleroLuna G., Pérez C.M. Sexual behaviors among adults in Puerto Rico: A population-based study. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011;8:2439–2449. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios-Ceña D., Carrasco-Garrido P., Hernández-Barrera V., Alonso-Blanco C., Jiménez-García R., Fernández-De las Peñas C. Sexual behaviors among older adults in Spain: Results from a population-based National Sexual Health Survey. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2012;9:121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto C., Botelho F., Tomada I., Tomada N. Comportamento sexual de estudantes de medicina portugueses e seus fatores preditivos. Revista Internacional de Andrología. 2016;14:53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Pratto F., Sidanius J., Stallworth L.M., Malle B.F. Social Dominance Orientation: A Personality variable Predicting Social and Political Attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:741–763. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Díaz F.J., Herrero-Olaizola J.B., Rodríguez-Franco L., Bringas-Molleda C., Paíno-Quesada S.G., Pérez-Sánchez B. Validation of Dating Violence Questionnaire-R (DVQ-R) International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2017;17:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal L., Levy S.R., Earnshaw V.A. Social dominance orientation relates to believing men should dominate sexually, sexual self-efficacy, and taking free female condoms among undergraduate women and men. Sex Roles. 2012;67:659–669. doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0207-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell B.L., Trigg K.Y. Tolerance of sexual harassment: An examination of gender differences, ambivalent sexism, social dominance, and gender roles. Sex Roles. 2004;50:565–573. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaluk J.K., Todd L.M., Milhausen R., Lachowsky N.J. Dominant heterosexual sexual scripts in emerging adulthood: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Sex Research. 2014;51:516–531. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.745473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Fuentes M.M., Salinas J.M., Sierra J.C. Use of an ecological model to study sexual satisfaction in a heterosexual Spanish sample. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2016;45:1973–1988. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0703-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Iglesias P., Sierra J.C., García M., Martínez A., Sánchez A., Tapia M.I. Índice de Satisfacción Sexual (ISS): un estudio sobre su fiabilidad y validez. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 2009;9:259–273. [Google Scholar]

- Sibley C.G., Wilson M.S., Duckitt J. Antecedents of men's hostile and benevolent sexism: The dual roles of social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33:160–172. doi: 10.1177/0146167206294745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius J. The psychology of group conflict and the dynamics of oppression: A social dominance perspective. In: McGuire W., Iyengar S., editors. Current approaches to political Psychology. Duke University Press; Durham, NC: 1993. pp. 183–219. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra J.C., Bermúdez M.P., Buela-Casal G., Salinas J.M., Monge F.S. Variables asociadas a la experiencia de abuso en la pareja y su denuncia en una muestra de mujeres. Universitas Psychologica. 2014;13:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, J. C., Costa, N., & Monge, F. S. (2012, October). Actitudes sexuales machistas en mujeres: análisis transcultural entre Brasil y Perú. Poster presented in XVI Congreso Latinoamericano de Sexología y Educación Sexual. Medellín, Colombia.

- Sierra J.C., Gutiérrez-Quintanilla R., Bermúdez M.P., Buela-Casal G. Male sexual coercion: Analysis of a few associated factors. Psychological Reports. 2009;105:69–79. doi: 10.2466/PR0.105.1.69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra J.C., Monge F.S., Santos-Iglesias P., Salinas J.M. Validation of reduced Spanish version of the index of spouse abuse. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2011;11:363–383. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra J.C., Rojas A., Ortega V., Martín Ortiz J.D. Evaluación de actitudes sexuales machistas en universitarios: primeros datos psicométricos de las versiones españolas de la Double Standard Scale (DSS) y de la Rape Supportive Attitude Scale (RSAS) International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 2007;7:41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra J.C., Santos-Iglesias P., Vallejo-Medina P., Moyano N. Síntesis; Madrid: 2014. Autoinformes como instrumento de evaluación en Sexología Clínica. [Google Scholar]

- Silván Ferrero M.P., Bustillos A. Adaptación de la Escala de Orientación a la Dominancia Social al castellano. Revista de Psicología Social. 2007;22:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Simon W., Gagnon J.H. Sexual scripts: Origin, influences, and change. Qualitative Sociology. 2003;26:491–497. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S. Premarital sexual standards for different categories of individuals. Journal of Sex Research. 1989;26:232–248. [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman M.E., Lorenzo-Seva U. Dimensionality assessment of ordered polytomous items with parallel analysis. Psychological Methods. 2011;16:209–220. doi: 10.1037/a0023353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells B.E., Twenge J.M. Changes in young people's sexual behavior and attitudes, 1943-1999: A cross-temporal meta-analysis. Review of General Psychology. 2005;9:249–261. [Google Scholar]