Abstract

Aim

Paediatric haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a stressful treatment with an impact on health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), and supportive interventions are needed. This study evaluated the effects of music therapy during and after HSCT.

Methods

This was a randomised clinical pilot study of 29 patients aged 0–17 years who underwent HSCT at Karolinska University Hospital in Huddinge, Stockholm, Sweden, between February 2013 and May 2017. The music therapy group comprised 14 children who received the music therapy during hospitalisation. Fifteen children in the control group received the intervention after discharge. Music therapy was offered twice a week for four to six weeks. The patients’ HRQoL, pain and mood were evaluated at admission, discharge and after six months. The instruments for HRQoL included the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 generic core scales.

Results

The scales showed that the music therapy group had a higher estimated physical function (adjusted p = 0.04) at the time of discharge, and the control group showed improved results after the intervention in all domains (p = 0.015).

Conclusion

Despite the small sample, we found improved HRQoL after music therapy, which suggests that it could be a complementary intervention during and after paediatric HSCT.

Keywords: Children, Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Health‐related quality of life, Music therapy, Paediatric cancer

Abbreviations

- HRQoL

Health‐related quality of life

- HSCT

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- PedsQL 3.0 cancer module

Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory 3.0 cancer module

- PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales

Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 generic core scales

Key notes.

Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation is a stressful treatment, where supportive interventions are needed.

We provided 29 children aged 0–17 years with music therapy, 14 during their hospital stay and 15 after discharge, to evaluate its impact on their health‐related quality of life.

The music therapy group had a higher estimated physical function at discharge, and the control group showed improved results after the intervention in all domains.

Introduction

Paediatric haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is increasingly being used to treat haematopoietic malignant and non‐malignant diseases 1. There is an improvement in the overall survival rate, but children still suffer from physical and mental strain due to the considerable amount of medical treatment, complications such as graft versus host disease, infections and the risk of relapses. The child is also isolated for a period of time, due to the intense treatment and risk of infections 2. This treatment affects the child's entire family, including their family relationships, and the health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) of the child and the parents is reduced 3.

During HSCT, the child's anxiety increases as they undergo many procedures, but an improvement in their HRQoL takes place first after four to 12 months 4. The lowest scores for HRQoL are observed one month and three months after HSCT, and it takes one to three years to return to the same level of HRQoL as they had before HSCT 4, 5, 6.

Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation is a life‐threatening procedure, and post‐traumatic stress disorder and post‐traumatic stress symptoms have been reported in HSCT survivors 3. Stuber et al. 7 reported that 80% of children showed moderate post‐traumatic stress symptoms three months after HSCT.

Children under three years of age are at risk of developing increased cognitive functioning problems at a later stage, due to, among other things, the use of total body irradiation, where the young child's nerve system is more vulnerable 8.

When a child is exposed to a trauma, all family members are affected. The parents often rate children's HRQoL lower than the children themselves 3, 9. Previous studies have also defined a relationship between a decreased quality of life for the child and impaired parental emotional functioning 10.

Musical interventions, defined as music medicine or music therapy, are used in medical settings to improve the patient's well‐being. Music medicine is the use of specially selected prerecorded or live music and is often managed by a professional other than a music therapist. Music therapy is a relational, interaction‐based form of therapy that includes the triad of the music, the child and the music therapist 11, 12.

Numerous studies have reported the effect of both music therapy and music medicine in paediatric cancer patients and also young adults going through HSCT 13, 14, 15, 16. However, only one study of music therapy for six children who underwent HSCT has been published, and the authors reported reduced levels of anxiety after the intervention 17.

A systematic review of 52 trials on music medicine and music therapy, which included six paediatric studies, concluded that music interventions had positive effects on the anxiety, pain, fatigue and HRQoL of adult cancer patients but did not draw any firm conclusions on the effect it had on children 18. So far, no study has estimated the HRQoL of children undergoing HSCT and receiving music therapy.

The aim of this study was to evaluate both the short‐term and long‐term impacts of music therapy on the well‐being of children going through HSCT. Due to ethical demands, the control group was offered music therapy after discharged, which made it possible to identify the effect of early and late interventions.

Our hypothesis is that music therapy could reduce anxiety, improve mood, support the mental health recovery and influence the rate and degree of physical recovery after allogeneic HSCT.

Methods

Patients

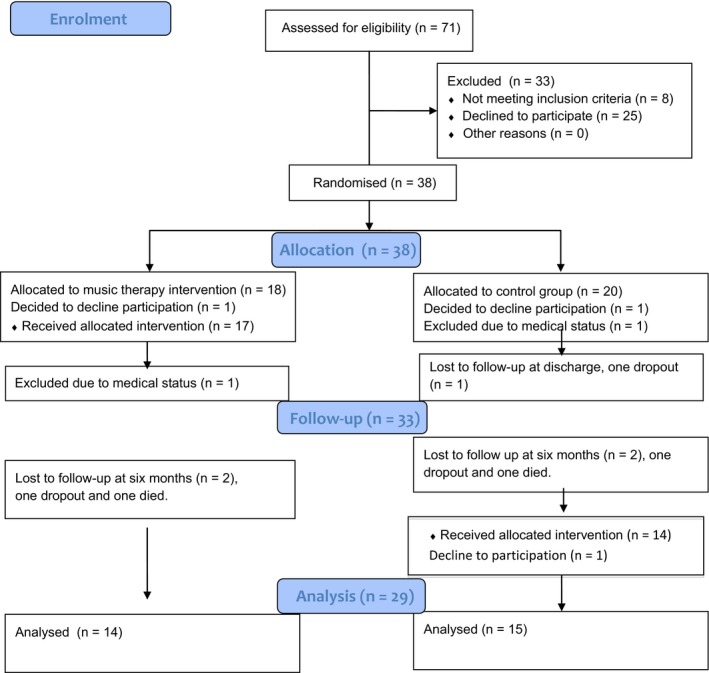

Between February 2013 and May 2017, children aged 0–18 years who were undergoing HSCT at Karolinska University Hospital in Huddinge, Stockholm, Sweden, were asked to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were hearing difficulties and language barriers. We contacted 63 patients and their parents, and 38 paediatric patients from two months of age to the age of 17 were initially included. Of the 18 patients in the music therapy group, one patient was excluded because their medical status deteriorated, two patients dropped out, and one child died. In conclusion, 16 children in the music therapy group were analysed at time of discharge having received the intervention in hospital, and 14 children in the music therapy group were analysed at the six‐month follow‐up (Fig. 1). The control group consisted initially of 20 patients, but three children dropped out, one patient was excluded because of their medical status, and one patient died. In summary, at the six‐month follow‐up, the control group consisted of 15 patients who had received the intervention after being discharged from hospital (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Music therapy for children undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplantation a randomised clinical trial.

Informed consent was obtained from both the children and parents. The children were at time of admission randomised to the music therapy group or control group. Clinical data, Lansky score and transplantation procedures are presented (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population, including 38 children who underwent HSCT at Karolinska University Hospital in Huddinge 2013–2017

| All patients | Music group | Control group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N= | 38 | 18 | 20 |

|

Age, mean median |

6.6 (0.2–17) 5 |

7.1 (0.5–17) 6 |

6.2 (0.2–16) 5 |

| Gender (M/F) | 23/15 | 9/9 | 14/6 |

| Diagnoses | |||

| Non‐malignant | 27 | 11 | 16 |

| AML/ALL | 8 | 5 | 3 |

| MDS | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Donor | |||

| MRD/URD/Haplo | 10/23/5 | 5/10/3 | 5/13/2 |

|

Donor age, mean median |

24.5 (0–53) 25 |

25.5 (0–53) 26.5 |

24 (2–45) 23.5 |

| Conditioning | |||

| MAC/RIC | 11/27 | 6/12 | 5/15 |

| TBI‐based | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Chemo‐based | 30 | 14 | 16 |

| SC source (BM/PBSC/CB) | 31/6/1 | 15/2/1 | 16/4/0 |

| Performance score at start of conditioning/Lansky (%)a | 90 (40–100) | 90 (40–100) | 90 (40–100) |

| Performance score at discharge/Lansky (%)b | 80 (30–100) | 80 (30–90) | 82 (70–100) |

ALL = Acute lymphoid leukaemia; AML = Acute myeloid leukaemia; BM = Bone marrow; CB = Cord blood; F = Female; Haplo = Haploidentical donor; HSCT = Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation; M = Male; MAC = Myeloablative conditioning; MDS = Myelodysplastic syndrome; MRD = Matched related donor; PBSC = Peripheral blood stem cells; RIC = Reduced intensity conditioning; SC = Stem cell; TBI = Total body irradiation; URD = Unrelated donor.

Includes all patients n = 38.

Includes patients analysed at discharge n = 33.

Music therapy was offered twice a week over a period of four to six weeks, and each session lasted approximately 45 minutes. The patients were hospitalised until they received HSCT and then they were monitored by an outpatient paediatric ward at the hospital.

The control group received standard medical care and ordinary psychosocial support. After discharge from the inpatient ward, the control group was offered music therapy at the outpatient paediatric ward twice a week for four to six weeks. The primary aim of our study was to compare HRQoL from baseline and after discharge from the inpatient ward.

Due to ethical demands, the control group received music therapy after they left hospital after their HSCT procedure. This enabled us to use a crossover design that included both groups. The music therapy group was measured between baseline and discharge, when they received the intervention, and at six months. The control group received music therapy between discharge and six months, but was measured at baseline, at discharge and at six months.

The Stockholm Ethics Committee at Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden, approved the study.

Protocol

The music therapy sessions took place in the child's hospital room, and the child was invited to sing, play on different musical instruments and listen to music with the music therapist. Parents could participate if the child wished (Appendix S1). This interaction and communication were used to create a relationship between the music therapist and the child 19. It was essential that the music therapist made the child feel safe and that the sessions were flexible, varied and person‐centred 20. The guidelines for the music therapist were to discover the child's musical preferences and adapt to the child's energy, needs and physical state and enabling the child to be in the present 20. The setting of the music therapy was required to provide a holding structure to keep the affect level within the child's windows of tolerance 21 and secure a therapeutic space stable enough to help both the child and their parents to stay emotional regulated 22.

When the music therapist was working with children under 18 months of age, the primary focus was on the interaction between the infant and parent and the child's body language showed the child's degree of commitment.

Procedures

Subject to their age, the children and their parents completed a set of questionnaires three times: at admission, at the time of discharge and at six months after the HSCT. The questionnaires were answered in the hospital. The research nurse assisted by reading the questions for the patients, when necessary. The parents answered their questions at the same time.

At each music therapy session start and end in the intervention group, a research nurse documented the mood of the children. At the same occasion, the child estimated his pain; for children under the age of four, the parents valued the pain observing the facial and bodily expression of the child. The children in the control group were recorded twice a week during their corresponding treatment period in the hospital, using the same survey.

Measures

To evaluate the children's HRQoL, we used the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 generic core scales (PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales) and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 3.0 cancer module (PedsQL 3.0 cancer module). These measurements are taken to evaluate HRQoL in children aged two to 18 years of age. Children under the age of two were not included in these questionnaires.

The PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales includes 23 items, divided into physical functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning and school functioning. The PedsQL 3.0 cancer module includes 27 items, divided into pain and hurt, nausea, procedural anxiety, treatment anxiety, worry, cognitive problems, perceived physical appearance and communication.

The children were able to answer the questions themselves from five to 17 years of age, and the parent proxy reports of their child's HRQoL covered two to 17 years of age. Patients aged eight to 17 and parents rated the items on a five‐point Likert scale, and children aged five to seven years of age rated the items on a three‐point scale. A higher score indicated a better HRQoL.

For children 0–17 years of age, the research nurse documented subjectively mood on a five‐point scale: depressed, sad, neutral, positive and happy before and after each music therapy session. For children under the age of four, the Astrid Lindgren Children's Hospital Pain Scale was used 23. This scale was used in combination with physiological parameters and verbal communication with parents.

The children in the music therapy group aged four to 17 completed a self‐assessment by visual analogue scale regarding pain before and after each session.

The patients in the control group were documented twice a week during the treatment period with the corresponding survey by the research nurse, and the children completed the self‐assessment regarding pain.

Lansky play performance scale was documented by the doctor during the HSCT and demonstrated the child's disease severity from 0 to 100% (Table 1).

Statistical analyses

To compare the differences between the groups before and after the music therapy, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U‐test was used regarding the PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales and PedsQL 3.0 cancer module.

We also used the paired t‐test to calculate the effect sizes within groups.

To examine differences within the same group, the Wilcoxon's signed‐rank test was used. We performed Bonferroni's corrections for multiple comparisons within blocks and adjusted the p values.

Finally, the pain and the mode scales were evaluated using linear regression with cluster‐robust standard errors (individuals as cluster).

Results

In total, 29 of the 38 participants (76%) who agreed to take part completed the entire study: 14 in the music therapy group and 15 in the control group (Fig. 1). The mean age of the entire study cohort before exclusions was 6.6 (0.2–17) years, and the median age was five years (Table 1). Nine children were under the age of two, two in the music therapy group and seven in the control group.

A summary of the PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales and the PedsQL 3.0 cancer module scores at baseline, at discharge and at six months is shown (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Scores for 18 children at ages 5 to 17 and 25 parents’ proxy report by PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales

| MT group children Suma (N) | C group children Suma (N) | Difference, p valuesb | MT group parents Suma (N) | C group parents Suma (N) | Difference, p valuesb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Physical functioning | ||||||

| Admission | 49.00 (9) | 71.33 (9) | 54.02 (14) | 66.19 (11) | ||

| Discharge | 54.43 (9) | 60.16 (8) | 0.01 | 37.47 (14) | 60.76 (10) | 0.54 |

| Six months | 57.40 (7) | 75.06 (7) | 0.096 | 54.17 (12) | 70.73 (9) | 0.94 |

| 2. Emotional functioning | ||||||

| Admission | 56.67 (9) | 60.56 (9) | 52.86 (14) | 58.18 (11) | ||

| Discharge | 55.00 (9) | 63.75 (8) | 0.77 | 48.21 (14) | 69.00 (10) | 0.029 |

| Six months | 57.86 (7) | 80.71 (7) | 0.4 | 60.83 (12) | 71.67 (9) | 0.48 |

| 3. Social functioning | ||||||

| Admission | 61.11 (9) | 71.67 (9) | 69.55 (14) | 65.45 (11) | ||

| Discharge | 57.96 (9) | 72.50 (8) | 0.7 | 67.50 (13) | 73.50 (10) | 0.34 |

| Six months | 64.28 (7) | 80.00 (7) | 0.85 | 73.33 (12) | 68.06 (9) | 0.36 |

| 4. School functioning | ||||||

| Admission | 53.12 (8) | 53.98 (9) | 42.36 (9) | 45.92 (9) | ||

| Discharge | 54.22 (8) | 45.00 (8) | 0.38 | 38.57 (7) | 48.75 (8) | 0.31 |

| Six months | 50.00 (5) | 73.57 (7) | 0.028 | 48.00 (5) | 51.88 (6) | 1.0 |

| Total | ||||||

| Admission | 54.84 (9) | 64.38 (9) | 57.00 (14) | 59.70 (11) | ||

| Discharge | 56.08 (9) | 60.35 (8) | 0.21 | 49.15 (14) | 65.04 (10) | 0.1 |

| Six months | 55.96 (7) | 77.34 (7) | 0.11 | 61.22 (12) | 67.88 (9) | 0.57 |

The music therapy group (MT) received therapy between admission and discharge and the control group (C) between discharge and follow‐up at six months.

A higher scoring indicates a better HRQoL.

The p‐values are not adjusted.

Table 3.

Scores for 13 children at ages 5 to 17 and 13 parents’ proxy report by PedsQL 3.0 cancer module

| MT group children Suma (N) | C group children Suma (N) | Mean difference, p valuesb | MT group parents Suma (N) | C group parents Suma (N) | Mean difference, p valuesb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pain and hurt | ||||||

| Admission | 60.00 (5) | 62.50 (8) | 56.25 (6) | 50.00 (7) | ||

| Discharge | 45.00 (5) | 57.14 (7) | 0.61 | 50.00 (6) | 64.58 (6) | 0.47 |

| Six months | 57.50 (5) | 81.25 (6) | 0.46 | 56.25 (6) | 47.50 (5) | 0.27 |

| 2. Nausea | ||||||

| Admission | 54.00 (5) | 64.38 (8) | 59.17 (6) | 54.28 (7) | ||

| Discharge | 46.00 (5) | 57.86 (7) | 0.57 | 32.24 (6) | 49.17 (6) | 0.42 |

| Six months | 64.00 (5) | 77.50 (6) | 0.78 | 50.21 (6) | 64.00 (5) | 0.86 |

| 3. Procedural anxiety | ||||||

| Admission | 65.00 (5) | 63.54 (8) | 84.72 (6) | 44.05 (7) | ||

| Discharge | 45.00 (5) | 59.52 (7) | 0.46 | 73.61 (6) | 59.72 (6) | 0.1 |

| Six months | 51.67 (5) | 59.72 (6) | 0.86 | 72.22 (6) | 55.00 (5) | 0.93 |

| 4. Treatment anxiety | ||||||

| Admission | 46.67 (5) | 86.46 (8) | 80.56 (6) | 80.95 (7) | ||

| Discharge | 60.00 (5) | 82.14 (7) | 0.035 | 75.00 (6) | 91.67 (6) | 0.12 |

| Six months | 71.67 (5) | 91.67 (6) | 1.0 | 81.94 (6) | 80.00 (5) | 0.23 |

| 5. Worry | ||||||

| Admission | 51.67 (5) | 73.96 (8) | 59.72 (6) | 64.28 (7) | ||

| Discharge | 58.33 (5) | 78.57 (7) | 0.053 | 63.89 (6) | 70.83 (6) | 0.87 |

| Six months | 63.33 (5) | 83.33 (6) | 0.78 | 76.39 (6) | 71.67 (5) | 0.65 |

| 6. Cognitive problems | ||||||

| Admission | 58.00 (5) | 77.19 (8) | 63.89 (6) | 77.08 (6) | ||

| Discharge | 62.50 (4) | 68.21 (7) | 0.33 | 63.75 (5) | 73.12 (6) | 0.78 |

| Six months | 64.00 (5) | 80.00 (6) | 0.67 | 62.08 (5) | 72.00 (5) | 0.54 |

| 7. Perceived physical appearance | ||||||

| Admission | 50.00 (5) | 84.52 (7) | 76.39 (6) | 72.62 (7) | ||

| Discharge | 41.67 (5) | 84.52 (7) | 0.4 | 35.00 (5) | 70.83 (6) | 0.054 |

| Six months | 65.00 (5) | 91.67 (6) | 0.049 | 59.17 (5) | 73.33 (5) | 0.54 |

| 8. Communication | ||||||

| Admission | 50.00 (5) | 82.30 (8) | 70.14 (6) | 80.56 (6) | ||

| Discharge | 55.00 (5) | 75.00 (7) | 0.25 | 47.50 (5) | 81.67 (5) | 0.046 |

| Six months | 61.67 (5) | 80.56 (6) | 0.93 | 45.83 (5) | 70.83 (4) | 0.22 |

The music therapy group (MT) received therapy between admission and discharge and the control group (C) between discharge and follow‐up at six months.

A higher scoring indicates a better HRQoL.

The p values are not adjusted.

Regarding the PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales at time of discharge, the total scores for the children in the music therapy group improved in contrast to the control group, whose total score decreased (Table 2).

When we used the PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales to examine the four different domains at discharge, the music therapy group had a statistically significant higher physical function level (adjusted p = 0.04) and a non‐significant increased school functioning score compared to the control group (Table 2).

Both groups had decreased mean differences of emotional and social function at discharge (Table 4).

Table 4.

Scores for 17 children at ages 5 to 17 and 24 parents’ proxy by PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales

| MT group children Mean differencea and (N) | C group children Mean differencea and (N) | Effect size Cohen's d Small 0.2 Medium 0.5 Large 0.8 | MT group parents Mean differencea and (N) | C group parents Mean differencea and (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Physical functioning | |||||

| Admission–discharge | 5.42 (9) | −12.28 (8) | 0.59 | −16.55 (14) | −8.31 (10) |

| Discharge–six months | 1.25 (7) | 18.37 (7) | 0.49b | 12.54 (12) | 12.95 (9) |

| 2. Emotional functioning | |||||

| Admission–discharge | −1.67 (9) | −1.25 (8) | −0.015 | −4.64 (14) | 8.00 (10) |

| Discharge–six months | 8.57 (7) | 22.14 (7) | 0.21b | 12.50 (12) | 6.11 (9) |

| 3. Social functioning | |||||

| Admission–discharge | −3.15 (9) | −1.25 (8) | −0.059 | −2.02 (13) | 5.00 (10) |

| Discharge–six months | 12.62 (7) | 11.43 (7) | −0.04b | 5.23 (11) | −2.50 (9) |

| 4. School functioning | |||||

| Admission–discharge | 1.25 (7) | −9.48 (8) | 0.26 | −10.18 (7) | 4.38 (8) |

| Discharge–six months | −13.75 (5) | 33.57 (7) | 0.62b | 13.00 (5) | 11.04 (6) |

| Total | |||||

| Admission–discharge | 1.23 (9) | −6.06 (8) | 0.32 | −7.85 (14) | 2.78 (10) |

| Discharge–six months | 2.63 (7) | 21.38 (7) | 0.49b | 11.73 (12) | 5.82 (9) |

Mean difference and effect size, analysed by paired t‐test.

The music therapy group (MT) received therapy between admission and discharge.

The control group (C) received music therapy between discharge and follow‐up at six months.

A higher scoring indicates a better HRQoL.

The effect size refers to control group as treatment group.

In the PedsQL 3.0 cancer module questionnaire, the mean differences in the music therapy group increased compared to the control group at hospital discharge in four of the eight items and these were treatment anxiety, worry, cognitive problems and communication (Table 5). The control group had decreased mean differences in eight items (Table 5).

Table 5.

Scores for 12 children at ages 5 to 17 and 12 parents’ proxy by PedsQL 3.0 cancer module

| MT group children Mean differencea and (N) | C group children Mean differencea and (N) | Effect size Cohen's d Small 0.2 Medium 0.5 Large 0.8 | MT group parents Mean differencea and (N) | C group parents Mean differencea and (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pain and hurt | |||||

| Admission–discharge | −15.00 (5) | −7.14 (7) | −0.15 | −6.25 (6) | 10.42 (6) |

| Discharge–six months | 12.50 (5) | 29.17 (6) | 0.22b | 6.25 (6) | −12.50 (5) |

| 2. Nausea | |||||

| Admission–discharge | −8.00 (5) | −12.14 (7) | 0.1 | −24.93 (6) | −12.50 (6) |

| Discharge–six months | 18.00 (5) | 24.17 (6) | 0.08b | 15.97 (6) | 22.00 (5) |

| 3. Procedural anxiety | |||||

| Admission–discharge | −20.00 (5) | −3.57 (7) | −0.25 | −11.11 (6) | 12.50 (6) |

| Discharge–six months | 6.67 (5) | 6.94 (6) | 0.004b | −1.39 (6) | 3.33 (5) |

| 4. Treatment anxiety | |||||

| Admission–discharge | 13.33 (5) | −4.76 (7) | 0.63 | −5.56 (6) | 5.56 (6) |

| Discharge–six months | 11.67 (5) | 12.50 (6) | 0.02b | 6.94 (6) | −10.00 (5) |

| 5. Worry | |||||

| Admission–discharge | 6.67 (5) | −2.38 (7) | 0.54 | 4.17 (6) | 1.39 (6) |

| Discharge–six months | 5.00 (5) | 5.55 (6) | 0.01b | 12.50 (6) | <−0.01 (5) |

| 6. Cognitive problems | |||||

| Admission–discharge | 1.25 (4) | −11.43 (7) | 0.38 | −3.92 (5) | −3.96 (6) |

| Discharge–six months | 6.25 (4) | 17.08 (6) | 0.22b | 3.23 (4) | 4.25 (5) |

| 7. Perceived physical appearance | |||||

| Admission–discharge | −8.33 (5) | −1.39 (6) | −0.27 | −36.67 (5) | −1.39 (6) |

| Discharge–six months | 23.33 (5) | 8.33 (6) | −0.46b | 17.71 (4) | 6.67 (5) |

| 8. Communication | |||||

| Admission–discharge | 5.00 (5) | −8.33 (7) | 0.38 | −16.67 (5) | 1.67 (5) |

| Discharge–six months | 6.67 (5) | 9.72 (6) | 0.07b | 16.67 (4) | −6.25 (4) |

Mean difference and effect size, analysed by paired t‐test.

The music therapy group (MT) received therapy between admission and discharge and the control group (C) between discharge and follow‐up at six months.

A higher scoring indicates a better HRQoL.

The effect size refers to control group as treatment group.

At discharge, differences were observed between the parent groups in the PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales, with the parents in the control group reporting improved functioning in three of the four domains (Table 2). In the PedsQL 3.0 cancer module scores at discharge, the parents in the music therapy group only reported increased functioning in the worry domain and the parents in the control group reported perceived increased functioning in five of the eight items (Table 3).

At six months, the control group's total score increased in all domains of the PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales. With regard to the four domains, the main difference between the groups was seen in school functioning (Table 2). In the total score of the PedsQL 3.0 cancer module (Table 3), all items improved in both groups at six months.

There were no significant statistical differences between the two parental groups at six months (Tables 2 and 3). The parents from the music therapy group reported increased scoring, indicating a higher HRQoL, in 11/12 items, where the control group's parents reported a decreased in five, of which one was only minimal, from 12 items (Tables 4 and 5).

At admission and discharge, there were no differences between the groups regarding disease severity based on the Lansky scale (Table 1).

When measuring the effect sizes, namely Cohen's d, we noticed that many items approximately medium‐sized and even the non‐significant values were 0.3–0.6 (Tables 4 and 5).

When we adjusted for multiple comparisons, the domain of physical functioning in the music therapy group and the increased results in the PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales in the control group after intervention still remained significant. The other results became non‐significant.

The mood in the music therapy group increased significantly after music therapy session (p = 0.000) compared to the control group. The pain decreased in the music therapy group after intervention, but was not statistically significant compared to the control group.

Discussion

In a previous study, we found that heart rate significantly decreased in the music therapy group four to eight hours after intervention compared to the control group, representing reduced stress levels and potentially lowering the risk of post‐traumatic stress disorder (p = 0.001) 24. Emotional regulation can be seen as one intermediate explanatory variable that contributed to the reduced heart rates in the music therapy group, and it was also a central component for mental health. Music experiences, such as listening to familiar preferred music, singing, creating music and improvising, may indicate an impact on emotion regulation and decreasing activity in the amygdala 25. The amygdala is part of the limbic system, and it regulates our emotions and affects our vital functions, such as heart rate and breathing. One study reported that when listening to music, this evoked a positive mood and could affect the recovery of hormones and cytokines in a positive way after acute stress in healthy adult volunteers 26.

For this study, we used child self‐assessment and parent proxy report questionnaires, including both the PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales and the PedsQL 3.0 cancer module, that are often used in studies in combination with medical parameters for children with cancer. Both these questionnaires have demonstrated reliability 27. The music therapy group demonstrated significantly better results than the control group in physical functioning and less signs of treatment anxiety and worry at the time of discharge. Interestingly, previous research in this field reported that the child's HRQoL showed the lowest values in physical functioning at one and three months post‐HSCT 5, 28, and anxiety was seen as an important negative factor for survivors of paediatric cancer 29. As earlier studies have also demonstrated, music interventions can reduce anxiety in both adult and children cancer patients 17, 18. Even pain may decrease after music intervention 13, 18, but in this study, there was no significant difference between the groups. In contrary, the children's mood in the music therapy group was estimated to be significantly improved (p = 0.000).

Our second aim was to evaluate the effects of the music intervention when the children were treated in the outpatient ward, where the control group received music therapy. Comparing the results between discharge and at the six‐month follow‐up in the control group, all domains in the PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales increased (p = 0.015), as well as all items in the PedsQL 3.0 cancer module. Previous research has reported that HRQoL starts to improve during the first four to 12 months after HSCT 4 and a smaller group of children experienced reduced HRQoL during the entire first year post‐HSCT 28.

At six months, the music therapy group showed improvements in all items and domains except school functioning. Notably, the improvement in physical functioning, signs of less treatment anxiety and worry that the music therapy group reported at discharge remained stable at six months. For children in this vulnerable situation, all effects that point to improved physiological function and reduced anxiety are of great importance, even moderate ones.

Previous research reported poorer HRQoL related to conditions such as graft versus host diseases, HSCT performed with unrelated donor, female gender, HSCT in older children and adolescents 4, 6, 30. When we compared the two study groups, our study did not explain the differences in HRQoL at discharge as there was no difference between the groups regarding these parameters (Table 1).

Music may have different effects on the child than on the parents because the relationship between the child and the music therapist is not easily accessible to the parent. Also, what happens within the child in connection with music therapy is their own self‐perception. In our study, which analysed the parent proxy reports, the control group parents reported several improvements between baseline and discharge, but the music therapy parents perceived less ability on all issues, except the subject of worry. Similarly, at six months, the parents in the control group reported decreased mean values in several items, in contrast to their children's overall increased estimations. In summary, our study demonstrated inconsistent agreement between the parents’ perceptions of their child's HRQoL and the child's self‐reported HRQoL, in line with previous research 9. This is an area for further research.

The Lansky performance scale for the music therapy group decreased after the intervention. This scale was performed by the doctor, and the physical functioning was scored by the child (adjusted p = 0.04). Interestingly, the doctor measured a lower disease severity compared to the children themselves.

The main limitation of our study was the small sample size, which reduced power and made it more difficult to find significant results. Also, the small sample size meant that we could not rely on large‐sample assumptions regarding cluster‐robust standard errors. Also, the Bonferroni's correction was conservative when tests were positively dependent.

Conclusion

This study focused on the HRQoL of children receiving music therapy after HSCT from their own perspective, but also their parents, as well as the Lansky scale scores estimated by the doctors. The combination of reduced heart rate values four to eight hours after the intervention in the music therapy group and the improved HRQoL reported by both groups suggests that music therapy can be an effective, complementary intervention during and after HSCT.

Funding

This study was supported by the Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation, Ekhaga Foundation, Swedish Research Council and the Stockholm County Council (ALF project).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 Fact‐box “Practical hints”.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the children and parents for taking part in our study. We want to thank the research nurses Charlotta Hausmann and Eva Martell for all their help with the questionnaires and recruitment, and we also want to thank Britt‐Marie Svahn, who inspired this study.

References

- 1. Miano M, Labopin M, Hartmann O, Angelucci E, Cornish J, Gluckman E, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation trends in children over the last three decades: a survey by the paediatric diseases working party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2007; 39: 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Remberger M, Ackefors M, Berglund S, Blennow O, Dahllöf G, Dlugosz A, et al. Improved survival after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in recent years. A single‐center study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2011; 17: 1688–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Packman W, Weber S, Wallace J, Bugescu N. Psychological effects of hematopoietic SCT on pediatric patients, siblings and parents: a review. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010; 45: 1134–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tremolada M, Bonichini S, Pillon M, Messina C, Carli M. Quality of life and psychosocial sequelae in children undergoing hematopoietic stem‐cell transplantation: a review. Pediatr Transplant 2009; 13: 955–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rodgers C, Wills‐Bagnato P, Sloane R, Hockenberry M. Health‐related quality of life among children and adolescents during hematopoietic stem cell transplant recovery. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2015; 32: 329–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tanzi EM. Health‐related quality of life of hematopoietic stem cell transplant childhood survivors: state of the science. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2011; 28: 191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stuber ML, Nader K, Yasuda P, Pynoos RS, Cohen S. Stress responses after pediatric bone marrow transplantation: preliminary results of a prospective longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991; 30: 952–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Simms S, Kazak AE, Golomb V, Goldwein J, Bunin N. Cognitive, behavioral, and social outcome in survivors of childhood stem cell transplantation. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2002; 24: 115–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Parsons SK, Tighiouart H, Terrin N. Assessment of health‐related quality of life in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: progress, challenges and future directions. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2013; 13: 217–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rodday AM, Terrin N, Parsons SK. Measuring global health‐related quality of life in children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant: a longitudinal study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013; 11: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garred R. The ontology of music in music therapy. Voices 2001; 1 http://doi.org/10.15845/voices.v1i3.63. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Trondalen G. Relational music therapy: an intersubjective perspective. Dallas, TX: Barcelona Publishers, 2016: 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nguyen TN, Nilsson S, Hellstrom AL, Bengtson A. Music therapy to reduce pain and anxiety in children with cancer undergoing lumbar puncture: a randomized clinical trial. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2010; 27: 146–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barrera ME, Rykov MH, Doyle SL. The effects of interactive music therapy on hospitalized children with cancer: a pilot study. Psychooncology 2002; 11: 379–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Robb SL, Burns DS, Stegenga KA, Haut PR, Monahan PO, Meza J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of therapeutic music video intervention for resilience outcomes in adolescents/young adults undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Cancer 2014; 120: 909–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sahler OJ, Hunter BC, Liesveld JL. The effect of using music therapy with relaxation imagery in the management of patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation: a pilot feasibility study. Altern Ther Health Med 2003; 9: 70–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Robb SL, Ebberts AG. Songwriting and digital video production interventions for pediatric patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation, part I: an analysis of depression and anxiety levels according to phase of treatment. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2003; 20: 2–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bradt J, Dileo C, Magill L, Teague A. Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; (8): CD006911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. MacDonald RAR, Kreutz G, Mitchell L. Music, health, and wellbeing. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012: 40–62. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bradt J. Guidelines for music therapy practice in pediatric care. Dallas, TX: Barcelona Publishers, 2012: 363–75 [Ebook]. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Siegel DJ. The developing mind: toward a neurobiology of interpersonal experience. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 1999: 253–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fosha D, Siegel DJ, Solomon MF. The healing power of emotion: affective neuroscience, development, and clinical practice. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co, 2009: 78–81, 132–3. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lundqvist P, Kleberg A, Edberg AK, Larsson BA, Hellstrom‐Westas L, Norman E. Development and psychometric properties of the Swedish ALPS‐Neo pain and stress assessment scale for newborn infants. Acta Paediatr 2014; 103: 833–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Uggla L, Bonde LO, Svahn BM, Remberger M, Wrangsjö B, Gustafsson B. Music therapy can lower the heart rates of severely sick children. Acta Paediatr 2016; 105: 1225–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moore KS. A systematic review on the neural effects of music on emotion regulation: implications for music therapy practice. J Music Ther 2013; 50: 198–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koelsch S, Boehlig A, Hohenadel M, Nitsche I, Bauer K, Sack U. The impact of acute stress on hormones and cytokines, and how their recovery is affected by music‐evoked positive mood. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 23008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Katz ER, Meeske K, Dickinson P. The PedsQL™ in pediatric cancer. Cancer 2002; 94: 2090–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brice L, Weiss R, Wei Y, Satwani P, Bhatia M, George D, et al. Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL): the impact of medical and demographic variables upon pediatric recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011; 57: 1179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McDonnell GA, Salley CG, Barnett M, DeRosa AP, Werk RS, Hourani A, et al. Anxiety among adolescent survivors of pediatric cancer. J Adolesc Health 2017; 61: 409–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tremolada M, Bonichini S, Basso G, Pillon M. Perceived social support and health‐related quality of life in AYA cancer survivors and controls. Psychooncology 2016; 25: 1408–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Fact‐box “Practical hints”.