Abstract

Objective

To investigate the safety and efficacy of ABT‐122, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)– and interleukin‐17A (IL‐17A)–targeted dual variable domain immunoglobulin, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) who have experienced an inadequate response to methotrexate.

Methods

Patients (n = 240) were randomized to receive ABT‐122 (120 or 240 mg every week), adalimumab (40 mg every other week), or placebo in a 12‐week double‐blind, parallel‐group study. The primary efficacy end point was the proportion of patients achieving ≥20% improvement in disease activity according to the American College of Rheumatology response criteria (ACR20) at week 12. Secondary and exploratory 12‐week end points included 50% improvement (ACR50) and 70% improvement (ACR70) response rates, and proportion of patients meeting the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) response criteria for ≥75% (PASI75) and ≥90% (PASI90) improvement in skin scores among those with ≥3% of their body surface area affected by psoriasis.

Results

In both ABT‐122 dose groups, ACR20 response rates at week 12 (64.8–75.3%) were superior to that in patients receiving placebo (25.0%) (P < 0.001) but similar to that in patients receiving adalimumab (68.1%). ACR50 and ACR70 response rates were also superior in both ABT‐122 dose groups (36.6–53.4% and 22.5–31.5%, respectively) compared to the placebo group (12.5% and 4.2%, respectively) (P < 0.05). Among eligible patients in the placebo, adalimumab, ABT‐122 120 mg every week, and ABT‐122 240 mg every week treatment groups, PASI75 responses were achieved in 27.3%, 57.6%, 74.4%, and 77.6% of patients, respectively, whereas PASI90 responses were achieved in 18.2%, 45.5%, 48.8%, and 46.9% of patients, respectively. Frequencies of treatment‐emergent adverse events, including infections, were similar across all treatment groups, causing no discontinuations. No serious infections or systemic hypersensitivity reactions were reported with ABT‐122.

Conclusion

Dual neutralization of TNF and IL‐17A with ABT‐122 had efficacy and safety that was similar to, and not broadly differentiated from, that of adalimumab over a 12‐week treatment course in patients with PsA.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic immune‐mediated inflammatory arthritis that is associated with psoriasis 1. Multiple pathways and mediators contribute to the pathogenesis of PsA, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) 2, 3, 4 and interleukin‐17A (IL‐17A) 1, 5, 6, 7, 8. Levels of TNF and IL‐17A–producing CD8+ T cells are elevated in the synovial fluid of patients with PsA 4, 9. Inhibition of either TNF or IL‐17A alone has demonstrated efficacy in improving joint inflammation, features of skin disease, and quality of life in patients with PsA 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, suggesting that TNF and IL‐17A may both contribute to the pathophysiology of PsA. An unanswered question has been whether, assuming that the contributions of TNF and IL‐17A are at least partly independent of one another, dual neutralization of TNF and IL‐17A may provide the opportunity to achieve better control of inflammation in patients with PsA compared to neutralization of either target alone. This hypothesis was supported by observations in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), in whom inhibition of TNF alone significantly raised the levels of IL‐17 and Th17 cells 17, 18, and both cytokines appeared to have separate influences in an ex vivo model 19.

The treatment of PsA with a combination of 2 conventional disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) 20, 21 or a DMARD plus a TNF inhibitor has been reported 10, 11, 15, 22. However, clinical trials simultaneously inhibiting 2 cytokines, TNF and IL‐17A, with biologics have not been reported in patients with PsA. In RA patients, combination therapy involving TNF inhibitors combined with biologic agents that engage other targets, including IL‐1 23, T cells 24, 25, and B cells 26, was associated with an increase in serious adverse events (AEs), including serious infections, and little or no efficacy benefit compared to treatment with a TNF inhibitor alone 23, 24, 25, 26.

ABT‐122 is a dual variable domain immunoglobulin (DVD‐Ig) that was engineered to target both human TNF and IL‐17A and is built on an adalimumab backbone with added IL‐17A binding domains 27. ABT‐122 binds TNF and IL‐17A in a fixed ratio of 1:1 28, with high affinity (KD of 11 pM and 45 pM for human TNF and human IL‐17A, respectively) and has in vitro functional activity in the low pM range 27, consistent with that of anti‐TNF antibodies alone and anti–IL‐17A antibodies alone 29, 30. In phase I studies in patients with RA, ABT‐122 has been shown to have dose‐proportional pharmacokinetics, with an effective half‐life of 10–18 days following dosing every week or every other week 31. In these studies, no clinically significant safety findings were observed with ABT‐122 through 8 weeks of dosing in patients with RA 32. Minor infections, common in phase I studies, were reported, with nasopharyngitis being the most frequent. There were no serious infections or systemic hypersensitivity reactions. In addition, ABT‐122 at clinically relevant doses suppressed the production of high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hsCRP) and chemokines contributing to inflammation 32. Furthermore, in a phase II study in patients with RA, ABT‐122 at 120 mg every week had a safety profile and efficacy similar to that of adalimumab over 12 weeks 33 and similar safety during an additional 24‐week extension 34.

The objective of this phase II trial was to assess the safety and efficacy of ABT‐122 in dosages of up to 240 mg every week over 12 weeks of therapy in patients who had active PsA despite receiving stable treatment with methotrexate.

Patients and Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice from the International Conference on Harmonisation and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. A local independent ethics committee or institutional review board or a central institutional review board (Schulman IRB, Cincinnati, OH) approved the protocol. All patients provided written informed consent.

Patients. Eligible patients (ages ≥18 years) had to have active PsA, defined as a diagnosis fulfilling the criteria of the Classification of Psoriatic Arthritis Study Group 35 for ≥3 months, as well as the presence of ≥3 tender joints and ≥3 swollen joints at screening, and at least 1 psoriatic plaque of ≥2 cm in diameter. Patients also had to have been receiving a stable dosage of methotrexate at ≥10 mg/week for ≥4 weeks. Key exclusion criteria included the following: prior exposure to adalimumab or another TNF inhibitor if the TNF inhibitor was discontinued for lack of efficacy or safety reasons or the drug had not been washed out for ≥5 half‐lives; prior exposure to other non‐TNF inhibitors or IL‐17 inhibitor biologic DMARDs, unless washed out for ≥5 half‐lives; current treatment with conventional synthetic DMARDs other than methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine; having received orally administered prednisone or its equivalent at ≥10 mg/day within 30 days of the baseline visit; current pregnancy or breastfeeding; and presence of active tuberculosis, chronic recurring infections, or active viral infections if the investigator assessed that the patient would be an unsuitable candidate for the study.

Study design . The study was designed as a phase II 12‐week, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group study conducted at 54 sites in Australia, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, New Zealand, Poland, Romania, Spain, and the United States. Following a screening period, patients receiving background methotrexate were randomized 3:3:3:1 to receive ABT‐122 120 mg every week, ABT‐122 240 mg every week, adalimumab (Humira; AbbVie) 40 mg every other week, or matching placebo subcutaneously for 12 weeks. Randomized treatments were assigned at each site via an interactive voice response or web response system, based on a randomization schedule that had been previously generated by the statistics group of the study sponsor.

ABT‐122 and its placebo were prepared from lyophilized powder by a pharmacist at each site who was unblinded with regard to the treatment; prefilled syringes of adalimumab and its placebo arrived ready for use. The patients and all other study site personnel remained blinded with regard to treatment assignments throughout the study. Because the syringes containing ABT‐122 and adalimumab were different in appearance, blinding required that all patients receive injections of ABT‐122 or its matching placebo at every weekly site visit, and adalimumab or its matching placebo at every other weekly site visit.

End point assessments. The primary efficacy end point was a ≥20% improvement in disease activity based on the American College of Rheumatology improvement response criteria (ACR20) 36 compared to placebo at week 12. A secondary end point was to compare the ACR20 response rates between ABT‐122 and adalimumab at week 12, although the study was not powered for these comparisons. Additional efficacy end points included ACR20 response rates as well as ≥50% improvement (ACR50) and ≥70% improvement (ACR70) response rates at each postbaseline assessment (weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12); disease control, defined for this study as a score of <3.2 or <2.6 on the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using hsCRP level (DAS28‐hsCRP) 37 at week 12; mean decrease from baseline in the DAS28‐hsCRP of at least 1.2 at week 12; mean changes from baseline in the DAS28‐hsCRP at each postbaseline assessment; improvement in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) skin scores by ≥50% (PASI50), ≥75% (PASI75), and ≥90% (PASI90) (38) at week 12 in patients who had ≥3% of their body surface area affected by psoriasis at baseline; responses on the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire modified for the spondyloarthritides (HAQ‐S) 39, defined empirically in this study as an improvement (decrease) from baseline of at least 0.5 points; mean changes in the HAQ‐S score at each postbaseline assessment; mean changes from baseline in the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) Enthesitis Index 40 at weeks 4, 8, and 12; and scores of 0 or 1 (full scale 0–6) on the physician's global assessment of psoriasis at week 12.

Safety assessments. Safety was assessed throughout the study period by monitoring the incidence of AEs, vital signs, physical examination findings, and laboratory abnormalities. The severity of the AEs and laboratory abnormalities was judged by the study investigators using the Rheumatology Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0 41. Recorded AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 18.1. Only treatment‐emergent AEs (i.e., those that occurred from the first dose of study drug until 70 days after the last dose) were analyzed.

Statistical analysis. Patients were analyzed based on the intent‐to‐treat principle. The full analysis set, which included all randomized patients who received at least 1 dose of study drug, was used for baseline and efficacy analyses. Baseline characteristics were calculated with summary statistics. For the primary efficacy end point (ACR20 response rates at week 12), it was estimated that a sample size of 66 patients in each ABT‐122 treatment arm and 22 patients in the placebo arm would result in >90% power to detect a 50% difference in response for ABT‐122 compared to placebo, assuming an ACR20 response rate of 20% with placebo and a 1‐sided alpha level of 0.025. The sample size was not designed to detect statistically significant differences between either of the ABT‐122 groups and the adalimumab group. Missing values were imputed as being a nonresponse, unless otherwise noted. The superiority of ABT‐122 at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 compared to placebo or adalimumab was calculated using Fisher's 1‐sided exact test (for categorical variables) or 2‐sided analysis of covariance models, with treatment as the fixed factor and the baseline value of the assessment as the covariate (for continuous variables). No statistical tests compared adalimumab to placebo. Safety was analyzed with summary statistics in all patients who received the study drug.

Results

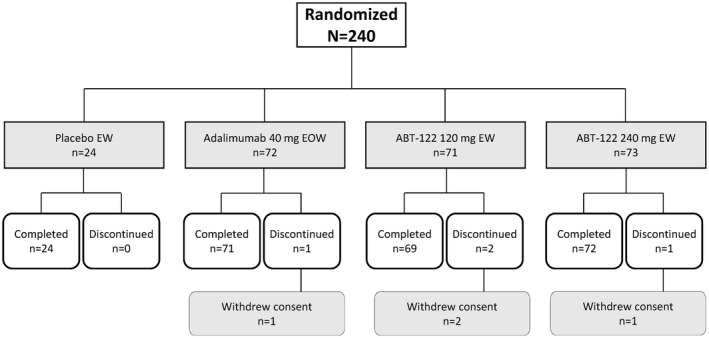

Characteristics of the study patients. A total of 240 patients were enrolled, randomized to a treatment group, and analyzed for treatment efficacy and safety from May 12, 2015 to April 28, 2016 (Figure 1). Approximately 50% of the patients were women; the mean age ranged from 47 years to 51 years, and the mean duration of PsA ranged from 6 years to 8 years (Table 1). Among the eligible patients, 46–67% had ≥3% of their body surface area affected by psoriasis, with a mean PASI score ranging from 9 to 15 across treatment groups at baseline. Four patients (1.7%) who withdrew consent discontinued from the study before its completion (1 patient in the adalimumab group, 2 in the ABT‐122 120 mg every week group, and 1 in the ABT‐122 240 mg every week group) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Disposition of the study patients. EW = every week; EOW = every other week.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline disease characteristics of the study patientsa

| Characteristic | Placebo every week (n = 24) | Adalimumab 40 mg every other week (n = 72) | ABT‐122 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 120 mg every week (n = 71) | 240 mg every week (n = 73) | |||

| Women, no. (%) | 12 (50.0) | 33 (45.8) | 37 (52.1) | 37 (50.7) |

| White, no. (%) | 24 (100) | 70 (97.2) | 70 (98.6) | 70 (95.9) |

| Age, years | 47.7 ± 13.7 | 50.5 ± 12.0 | 51.0 ± 12.4 | 47.4 ± 13.8 |

| Weight, kg | 76.9 ± 17.4 | 86.7 ± 16.0 | 85.4 ± 16.8 | 83.1 ± 18.4 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.8 ± 4.0 | 29.4 ± 5.0 | 29.6 ± 5.3 | 28.3 ± 5.8 |

| Duration of PsA, years | 7.6 ± 7.2 | 8.4 ± 9.2 | 5.9 ± 7.1 | 7.5 ± 8.2 |

| MTX dose, mg/week | 17.4 ± 5.2 | 16.9 ± 4.4 | 15.3 ± 4.5 | 15.3 ± 4.7 |

| Any prior non‐MTX DMARD, no. (%) | 6 (25.0) | 22 (30.6) | 16 (22.5) | 16 (21.9) |

| TJC68 | 19.0 ± 14.7 | 23.4 ± 17.0 | 21.7 ± 14.6 | 23.6 ± 14.3 |

| SJC66 | 13.4 ± 11.4 | 14.0 ± 10.6 | 12.7 ± 10.4 | 14.8 ± 11.8 |

| DAS28‐hsCRP score | 4.6 ± 1.1 | 5.1 ± 1.1 | 5.0 ± 1.2 | 4.8 ± 1.3 |

| HAQ‐S score (range 0–3) | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.6 |

| BSA ≥3%, no. (%) | 11 (45.8) | 33 (45.8) | 43 (60.6) | 49 (67.1) |

| PASI (in patients with ≥3% BSA) (range 0–72) | 8.8 ± 4.6 | 11.9 ± 9.3 | 11.8 ± 9.5 | 14.9 ± 12.9 |

| Enthesitis, no. (%) | 14 (58.3) | 54 (75.0) | 50 (70.4) | 53 (72.6) |

| SPARCC Enthesitis Index (range 0–16) | 2.8 ± 4.1 | 3.7 ± 3.9 | 3.6 ± 4.1 | 4.0 ± 4.1 |

| Dactylitis, no. (%) | 13 (54.2) | 42 (58.3) | 40 (56.3) | 46 (63.0) |

Except where indicated otherwise, values are the mean ± SD. BMI = body mass index; PsA = psoriatic arthritis; MTX = methotrexate; DMARD = disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug; TJC68 = tender joint count based on 68 joints assessed; SJC66 = swollen joint count based on 66 joints assessed; DAS28‐hsCRP = Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein level; HAQ‐S = Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire modified for the spondyloarthritides; BSA = body surface area affected by psoriasis; PASI = Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; SPARCC = Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada.

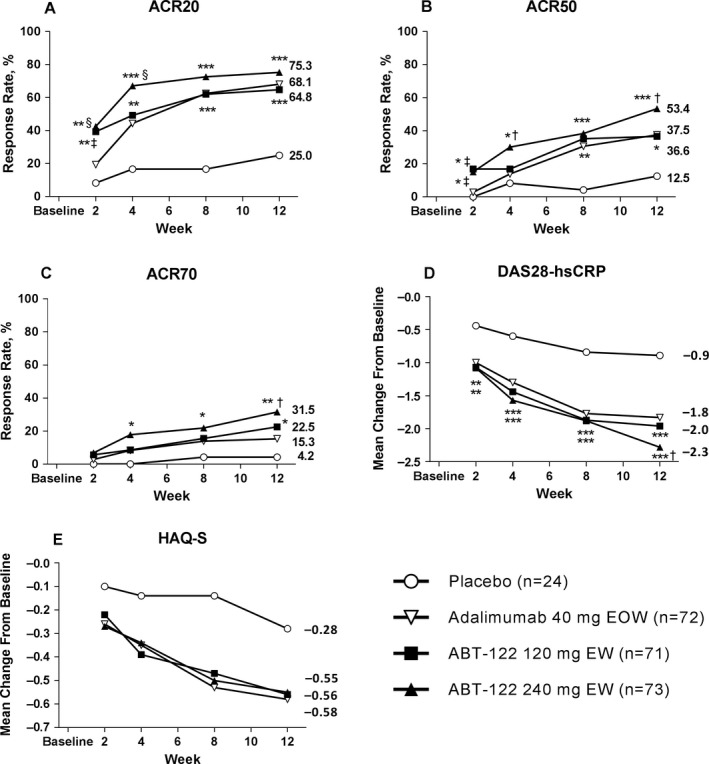

Efficacy. The ACR20 response rates at week 12 (primary end point) for the ABT‐122 120 mg every week and ABT‐122 240 mg every week dose groups (64.8% and 75.3%, respectively) were statistically superior (P < 0.001) to that in the placebo group (25.0%) and comparable to that in the adalimumab group (secondary end point; 68.1%) (Figure 2A). ACR20 response rates at other time points were also statistically significantly greater with ABT‐122 120 mg every week and ABT‐122 240 mg every week compared to placebo: at week 2, 39.4% (P = 0.003) and 42.5% (P = 0.001) versus 8.3%; at week 4, 49.3% (P = 0.004) and 67.1% (P < 0.001) versus 16.7%; and at week 8, 62.0% (P < 0.001) and 72.6% (P < 0.001) versus 16.7%.

Figure 2.

End point analyses in patients with psoriatic arthritis in the different treatment groups. A–C, Proportion of patients achieving ≥20% improvement in disease activity according to the American College of Rheumatology response criteria (ACR20) (A), as well as 50% (ACR50) (B) and 70% (ACR70) (C) improvement response rates, over the 12‐week treatment course (with nonresponder imputation). D, Least squares mean change in the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein level (DAS28‐hsCRP) (with last observation carried forward imputation). E, Mean change in scores on the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire modified for the spondyloarthritides (HAQ‐S) (with last observation carried forward imputation). No statistical testing was done for the mean change in HAQ‐S scores; it was only done for the responder definition of a score increase of ≥0.5. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P < 0.001 for ABT‐122 versus placebo. † = P < 0.05; ‡ = P < 0.01; § = P ≤ 0.005 for ABT‐122 versus adalimumab. EOW = every other week; EW = every week.

Furthermore, at early time points, ACR20 response rates in the ABT‐122 120 mg every week or ABT‐122 240 mg every week groups were statistically significantly superior to that following treatment with adalimumab. At week 2, the ACR20 response rates were 39.4% with ABT‐122 120 mg every week (P = 0.007) and 42.5% with ABT‐122 240 mg every week (P < 0.003) compared to 19.4% with adalimumab. At week 4, the ACR20 response rate was 67.1% with ABT‐122 240 mg every week compared to 44.4% with adalimumab (P = 0.005). However, at later time points (weeks 8 and 12), the ACR20 response rates were comparable between ABT‐122 and adalimumab treatment.

ACR50 responses in both ABT‐122 dose groups were statistically significantly superior to that in the placebo group at week 12: with ABT‐122 120 mg every week and 240 mg every week, 36.6% (P = 0.021) and 53.4% (P < 0.001), respectively, compared to 12.5% in the placebo group. Moreover, the ACR50 response rate at week 12 was statistically significantly superior with ABT‐122 240 mg every week compared to adalimumab (37.5%; P = 0.039) (Figure 2B).

In addition, at some earlier time points, ACR50 responses were statistically significantly greater with ABT‐122 compared to placebo: at week 2, with ABT‐122 120 mg every week and 240 mg every week, 16.9% (P = 0.023) and 15.1% (P = 0.036), respectively, compared to 0% with placebo; and at week 4, with ABT‐122 120 mg every week and 240 mg every week, 16.9% (P not significant) and 30.1% (P = 0.025), respectively, compared to 8.3% with placebo. ACR50 responses at some earlier time points were also statistically significantly greater with ABT‐122 compared to adalimumab: at week 2, with ABT‐122 120 mg every week and 240 mg every week, 16.9% (P = 0.004) and 15.1% (P = 0.009), respectively, compared to 2.8% with adalimumab; and at week 4, with ABT‐122 240 mg every week, 30.1% compared to 13.9% with adalimumab (P = 0.015).

ACR70 responses at week 12 were statistically significantly greater with ABT‐122 120 mg every week (22.5%) (P = 0.034) and ABT‐122 240 mg every week (31.5%) (P = 0.004) compared to placebo (4.2%) (Figure 2C). The ACR70 response rate at week 12 was also significantly greater with ABT‐122 240 mg every week compared to that following treatment with adalimumab (31.5% versus 15.3%; P = 0.017). At earlier time points, the ACR70 response rate with ABT‐122 240 mg every week was significantly greater than with placebo at week 4 (17.8% versus 0%; P = 0.019) and at week 8 (21.9% versus 4.2%; P = 0.038).

The mean change from baseline in the DAS28‐hsCRP score was significantly greater in both the ABT‐122 120 mg every week and ABT‐122 240 mg every week dose groups than in the placebo group at week 2 (−1.07 and −1.08 versus −0.44; P < 0.008 and P < 0.006, respectively), week 4 (−1.44 and −1.57 versus −0.60; both P < 0.001), week 8 (−1.87 and −1.88 versus −0.84; both P < 0.001), and week 12 (−1.96 and −2.28 versus −0.89; both P < 0.001) (Figure 2D). At week 12, the mean change from baseline in the DAS28‐hsCRP score was statistically significantly greater with ABT‐122 240 mg every week (−2.28) compared to that with adalimumab (−1.83; P = 0.012).

Disease control responses based on the proportion of patients achieving DAS28‐hsCRP score thresholds of <3.2 or <2.6 were statistically superior or numerically higher, but not statistically significantly different, in all active treatment groups compared to the placebo group, but differences between each ABT‐122 dose group and the adalimumab group were not statistically significant (see Supplementary Figure 1, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.40579/abstract). At week 12, the response rate based on a DAS28‐hsCRP score of <3.2 was significantly greater in patients receiving ABT‐122 240 mg every week compared to those receiving placebo (68.5% versus 41.7%; P = 0.018). The response rates based on a DAS28‐hsCRP score of <2.6 at week 12 were significantly greater with ABT‐122 120 mg every week (45.1%) and 240 mg every week (52.1%) compared to placebo (16.7%; P = 0.011 and P = 0.002, respectively).

All active treatment groups had clinically important greater mean changes from baseline in the HAQ‐S scores compared to the placebo group; statistical comparisons were not performed (Figure 2E). At week 12, HAQ‐S responses based on a decrease in score of ≥0.5 were generally similar across the active therapy groups, and only the ABT‐122 240 mg every week group showed a statistically significantly greater HAQ‐S response rate compared to the placebo group (54.8% versus 25.0%; P = 0.01) (see Supplementary Figure 2, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.40579/abstract).

The mean change from baseline in the SPARCC Enthesitis Index at week 12 was numerically similar across active therapies. Statistically significantly greater mean changes in the SPARCC Enthesitis Index scores at week 12 were seen with ABT‐122 120 mg every week (−2.8) and 240 mg every week (−2.5) compared to that with placebo (−1.2; P = 0.003 and P = 0.017, respectively) (see Supplementary Figure 3, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.40579/abstract).

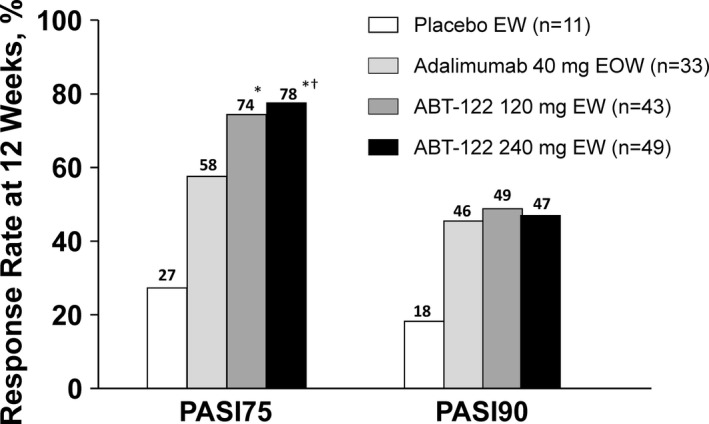

All active treatment groups had higher PASI75 and PASI90 responses compared to the placebo group at week 12 (Figure 3). The PASI75 response at week 12 in those who received ABT‐122 120 mg every week was numerically higher than, but not statistically significantly different from, that in patients who received adalimumab (74.4% versus 57.6%). In the ABT‐122 240 mg every week group, the PASI75 response at week 12 was statistically significantly greater than the response with adalimumab (77.6% versus 57.6%; P = 0.047). PASI90 responses were similar among the treatment groups receiving either ABT‐122 or adalimumab. Furthermore, in all active treatment groups, the PASI90 responses were higher than, but not statistically significantly different from, those observed in the placebo group, possibly because the PASI analyses were limited to the smaller subgroup of patients who had an affected body surface area of ≥3% at baseline.

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients meeting the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) response criteria for ≥75% (PASI75) and ≥90% (PASI90) improvement in skin scores (with nonresponder imputation) at 12 weeks among those with ≥3% of body surface area affected by psoriasis at baseline. * = P < 0.01 for ABT‐122 versus placebo; † = P < 0.05 for ABT‐122 versus adalimumab. EW = every week; EOW = every other week.

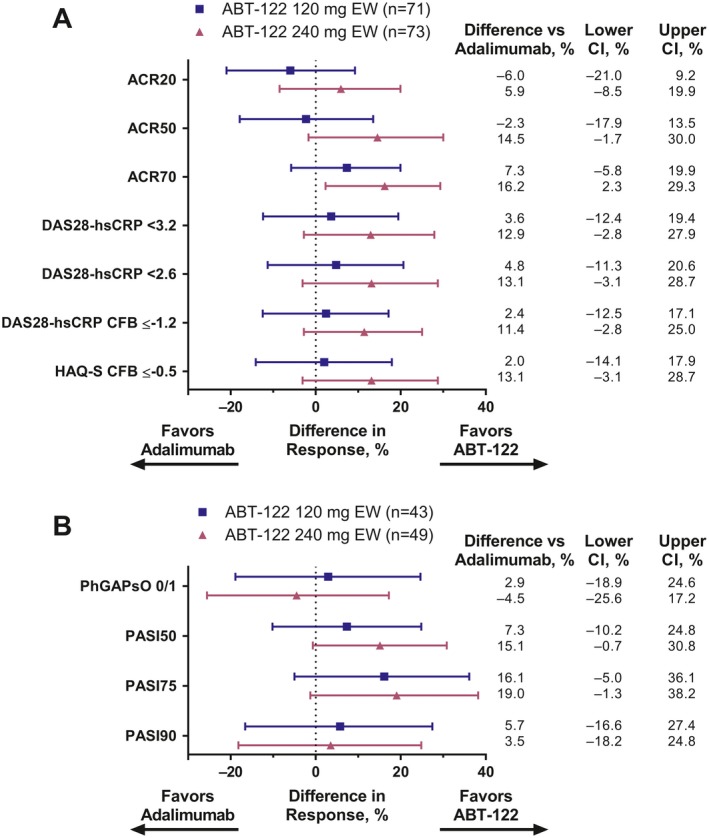

Joint and skin responses to treatment at week 12 mostly favored ABT‐122 over adalimumab, as depicted by the forest plots in Figure 4 (19 of 22 dose‐group comparisons). However, clinically important differences were few, and statistically significant separation was seen for only 1 comparison: the ACR70 response with ABT‐122 240 mg every week (i.e., the 95% confidence interval excluded zero).

Figure 4.

Treatment responses in the joints and skin at 12 weeks in the ABT‐122 120 mg every week or 240 mg every week groups as compared to the adalimumab group. A, Joint responses at 12 weeks were measured according to the American College of Rheumatology response criteria of ≥20% (ACR20), ≥50% (ACR50), and ≥70% (ACR70) improvement, score thresholds of <3.2 and <2.6, as well as change from baseline (CFB) ≤−1.2, for the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein level (DAS28‐hsCRP), and CFB ≤−0.5 in the score on the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire modified for the spondyloarthritides (HAQ‐S). B, Skin responses at 12 weeks in patients with ≥3% body surface area affected by psoriasis at baseline were measured as a score of 0 or 1 on the physician's global assessment of psoriatic disease activity (PhGAPsO) (full scale 0–6) and as the proportion of patients achieving improvement in skin scores according to the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index response criteria of ≥50% (PASI50), ≥75% (PASI75), and ≥90% (PASI90) improvement. All analyses used last observation carried forward imputation. Bars show the difference in response with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). EW = every week.

Pharmacokinetics. The average molar serum concentrations of ABT‐122 in the dosing interval at steady state with dosages of 120 mg every week and 240 mg every week were ~2‐fold and ~4‐fold higher, respectively, compared to the exposure with adalimumab at 40 mg every other week. The mean steady‐state serum concentrations (Ctrough) of ABT‐122 at week 12 were 11.6 μg/ml and 27.3 μg/ml in the 120 mg every week and 240 mg every week treatment groups, respectively. The proportion of subjects with Ctrough concentrations below the limit of quantitation at the 12‐week time point was ~3% in both the ABT‐122 120 mg every week and ABT‐122 240 mg every week groups. Details of ABT‐122 pharmacokinetic results are reported elsewhere 42.

Safety. The frequency of treatment‐emergent AEs was similar across groups, and none led to discontinuation (Table 2). There were 2 reports of serious AEs: 1 in a patient receiving placebo (motor vehicle collision), and 1 receiving ABT‐122 240 mg every week (sick sinus syndrome, with fainting; coded as heart rate decreased, with syncope). The incidence of infections was generally similar across the active treatment groups (range 19.7–27.8%) and placebo group (20.8%); no serious infections were reported in any treatment group. A nonserious event, oral candidiasis, was reported in 2 patients in the ABT‐122 groups. No systemic hypersensitivity or severe injection site reactions occurred with ABT‐122, adalimumab, or placebo. At week 12, the mean decrease from baseline in the neutrophil count was ~20% in both ABT‐122 dose groups (range −20.5% to −20.9%) and in the adalimumab group (−18.6%); however, there were no reports of a neutrophil count decrease with a severity of grade 3 or above in the ABT‐122 groups. The decreased neutrophil count was not found to be associated with infection events. Abnormal values for other laboratory parameters were indicative of generally mild or moderately severe changes and were not clinically meaningful.

Table 2.

Summary of safety dataa

| Event | Placebo every week (n = 24) | Adalimumab 40 mg every other week (n = 72) | ABT‐122 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 120 mg every week (n = 71) | 240 mg every week (n = 73) | |||

| Any TEAE | 11 (45.8) | 38 (52.8) | 33 (46.5) | 31 (42.5) |

| Serious AE | 1 (4.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.4)b |

| Severe AE | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 1 (1.4)b |

| Infection | 5 (20.8) | 20 (27.8) | 14 (19.7) | 15 (20.5) |

| Candidiasis | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.4)c | 1 (1.4)c |

| Nasopharyngitis | 0 | 6 (8.3) | 4 (5.6) | 3 (4.1) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 2 (8.3) | 5 (6.9) | 1 (1.4) | 7 (9.6) |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.8) | 4 (5.5) |

| Leukopeniad | 0 | 2 (2.8) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) |

| Neutropeniad | 0 | 2 (2.8) | 2 (2.8) | 1 (1.4) |

| Neutrophil count grade | ||||

| Grade 1 (1.5–1.9 × 109/liter) | 2 (8.3) | 11 (15.3) | 6 (8.5) | 14 (19.2) |

| Grade 2 (1.0–1.4 × 109/liter) | 0 | 2 (2.8) | 5 (7.0) | 5 (6.8) |

| Grade 3 (0.5–0.9 × 109/liter) | 1 (4.2) | 2 (2.8) | 0 | 0 |

Values are the number (%) of patients. There were no treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) leading to discontinuation, deaths, malignancies, systemic hypersensitivity reactions, severe injection site reactions, serious infections, or grade 4 neutrophil count abnormalities (<0.5 × 109/liter).

Non–drug‐related decreased heart rate/syncope was reported in 1 patient.

Oral candidiasis.

Reported for laboratory values of special interest.

Discussion

ABT‐122 is the first DVD‐Ig for which results have been reported in patients with PsA. The results show that over 12 weeks, the efficacy of ABT‐122 was superior to placebo, and with ABT‐122 at 240 mg every week, the PASI75, ACR50, and ACR70 response rates were superior to those with adalimumab. However, other outcomes were generally similar between the ABT‐122 and adalimumab groups, including the study's primary end point, the ACR20 response, and the PASI90 response. ABT‐122 had an acceptable safety profile over 12 weeks of therapy in patients with PsA who were receiving background methotrexate, with similar incidences of treatment‐emergent AEs across different treatment groups and an infection risk similar to that with placebo and adalimumab, despite the fact that dual inhibition of TNF and IL‐17A provided molar exposures that were equivalent to or higher than those with adalimumab.

Although higher‐dose ABT‐122 did show superiority to adalimumab in terms of the PASI75 skin score response, and also showed higher‐threshold ACR disease activity improvement responses, there was little convincing benefit of either ABT‐122 dose over adalimumab at 40 mg every other week in terms of the effects on multiple other end points, including the PASI90 response. Thus, the relative contribution of anti‐TNF antibodies compared to anti–IL‐17A antibodies to the efficacy observed with ABT‐122 in this study remains unknown.

Our observations from exposure response models with ABT‐122, in which multiple end points, including ACR and PASI response scores, were examined, suggest that the additional benefits with ABT‐122 at higher doses could be related to higher exposures of TNF inhibition. These exposure response models, the results of which will be published separately, did not suggest that the IL‐17A inhibitory action of ABT‐122 contributed to the dose‐related additional efficacy observed with the dosage of 240 mg every week. The exposures of TNF inhibition with ABT‐122 dosages of 120 mg every week and 240 mg every week were 2 times and 4 times higher, respectively, than that with adalimumab at 40 mg every other week. ABT‐122 serum exposure at a dose of 120 mg every week was comparable to or lower than that reported in the labels for the anti–IL‐17A monoclonal antibodies ixekizumab (80 mg every week) or secukinumab (150 mg every 4 weeks or 300 mg every 4 weeks). At a dosage of 240 mg every week, ABT‐122 serum exposure was 2‐fold higher than that of ixekizumab at 80 mg every week, equal to that of secukinumab at 150 mg every 4 weeks, and approximately one‐half that of secukinumab 300 mg every 4 weeks 43, 44.

The affinity and potency of ABT‐122 with regard to its interactions with TNF and IL‐17A were comparable to those of antibodies directed solely against TNF and antibodies directed solely against IL‐17A 27, 29, 30. The PASI90 skin responses in particular suggest that ABT‐122 is functioning largely through its effects on anti‐TNF activity, since the greater efficacy expected with the addition of IL‐17A inhibition 13, 14 was not seen.

Data from RA patients treated in phase I research trials have shown that ABT‐122 rapidly and persistently modulates potential pathophysiologic pathways involved in RA, including reducing the serum levels of chemokines involved in inflammatory cell recruitment into inflamed tissues 32, suggesting that dual inhibition of TNF and IL‐17A provides functional blockade of both of these cytokines. In addition, a genomic and epigenetic analysis of phase II data in patients with RA showed changes in the expression of genes associated with IL‐17A signaling after 4 weeks of treatment, indicating that IL‐17A is inhibited by ABT‐122 45. These data sets suggest that both the anti‐TNF component and the anti–IL‐17A component of the molecule are active.

In addition, in the RA patient trials, changes in the serum levels of associated proteins were observed at 4 and 12 weeks. The measurement of free serum IL‐17A showed a decline in serum levels in patients with RA treated with ABT‐122, which was not seen in those receiving adalimumab treatment alone (data on file) 45. However, analyses of the correlation between changes in gene expression and DNA methylation at week 4 and DAS28‐hsCRP responses at week 12 indicated that the response to ABT‐122 in patients with RA was primarily driven by TNF inhibition, with little added contribution from inhibition of IL‐17A 45.

In light of data from other recent clinical trials, inhibition of IL‐17A does appear to have greater efficacy in terms of its impact on end points in patients with psoriasis 46, 47 and on PsA skin and joint disease end points 12, 13, as compared to its impact on joint disease end points in patients with RA 48, 49. These findings support immunohistologic observations of the importance of Th17 cells and IL‐17A in the pathogenesis of psoriasis 50, 51, 52.

Despite the demonstrated activity of both the anti‐TNF component and the anti–IL‐17A component of ABT‐122, the similar efficacy of ABT‐122 and adalimumab seen in the present study suggests that the effects of ABT‐122 were primarily the result of inhibition of TNF. The anti–IL‐17A property of ABT‐122 may have contributed little additive benefit to the observed treatment effects.

A strength of this study was the ability to directly compare the efficacy of ABT‐122 to that of adalimumab. In addition, it was the first direct study of dual cytokine inhibition in patients with PsA, in whom no evidence of serious AEs or serious infections was observed.

Limitations of this study included its short duration of 12 weeks. Although 12 weeks has been an adequate length of time to assess the efficacy of other biologic agents in terms of improvements in both the skin and the joints 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, it remains a limitation in terms of reaching conclusions with regard to safety. Another limitation is that although an active comparator arm targeting TNF inhibition alone (adalimumab) was included for comparison to ABT‐122, the study had no active comparator with an agent that targeted IL‐17A inhibition alone.

In conclusion, the similarity of the incidence rates of AEs between ABT‐122 and adalimumab adds to a growing database suggesting that inhibition of 2 cytokines may not always be associated with higher incidence of AEs, although direct comparison with the AE profile of combined treatment with 2 single cytokine blockers in patients with PsA was not undertaken, and results could differ from those in the current study. Compared to adalimumab, and despite the dual neutralization of TNF and IL‐17A with a DVD‐Ig, there was not a clearly differentiated efficacy between ABT‐122 and adalimumab over 12 weeks. Due to this lack of adequate efficacy differentiation, further development of ABT‐122 for the treatment of PsA is not being pursued.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. Mease had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design

Mease, Genovese, Weinblatt, Peloso, Chen, Othman, Mansikka, Khatri.

Acquisition of data

Mease, Peloso, Chen, Othman, Li, Mansikka, Khatri, Wishart.

Analysis and interpretation of data

Mease, Genovese, Weinblatt, Peloso, Chen, Othman, Li, Mansikka, Khatri, Liu.

Role of the Study Sponsor

AbbVie funded the study, contributed to the study design, and was involved in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data and in the writing, review, and approval of the publication. All authors contributed to the development of the content. All authors and AbbVie reviewed and approved the final manuscript, but the authors maintained control over the final content. Medical writing support, provided by Richard M. Edwards, PhD, and Michael J. Theisen, PhD, of Complete Publication Solutions, LLC (North Wales, PA), was funded by AbbVie.

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual and trial‐level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications.

These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments

We thank Dana Kappel and Sharon Bak (Operations) of AbbVie for their study contributions. In addition, we thank all of the patients who participated in this clinical trial of an investigational product, ABT‐122, and all study investigators for their contributions.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02349451.

Supported by AbbVie.

Dr. Mease has received consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Genentech, Merck, Sun Pharma, and UCB (less than $10,000 each) and from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, and Pfizer (more than $10,000 each), and has received research support from those companies. Dr. Genovese has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB (less than $10,000 each) and has received research support from those companies. Dr. Weinblatt has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Crescendo Bioscience, Janssen, Pfizer, and Roche (less than $10,000 each) and from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and UCB (more than $10,000 each), and has received research support from Amgen, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Crescendo Bioscience, DxTerity, and UCB. Drs. Peloso, Chen, Othman, Li, Mansikka, Khatri, Wishart, and Liu own stock or stock options in AbbVie.

References

- 1. De Vlam K, Gottlieb AB, Mease PJ. Current concepts in psoriatic arthritis: pathogenesis and management. Acta Derm Venereol 2014;94:627–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mease PJ. Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) in psoriatic arthritis: pathophysiology and treatment with TNF inhibitors. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:298–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ritchlin C, Haas‐Smith SA, Hicks D, Cappuccio J, Osterland CK, Looney RJ. Patterns of cytokine production in psoriatic synovium. J Rheumatol 1998;25:1544–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Partsch G, Steiner G, Leeb BF, Dunky A, Broll H, Smolen JS. Highly increased levels of tumor necrosis factor‐α and other proinflammatory cytokines in psoriatic arthritis synovial fluid. J Rheumatol 1997;24:518–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jandus C, Bioley G, Rivals JP, Dudler J, Speiser D, Romero P. Increased numbers of circulating polyfunctional Th17 memory cells in patients with seronegative spondylarthritides. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2307–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leipe J, Grunke M, Dechant C, Reindl C, Kerzendorf U, Schulze‐Koops H, et al. Role of Th17 cells in human autoimmune arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:2876–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Raychaudhuri SP, Raychaudhuri SK, Genovese MC. IL‐17 receptor and its functional significance in psoriatic arthritis. Mol Cell Biochem 2012;359:419–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mease PJ. Inhibition of interleukin‐17, interleukin‐23 and the TH17 cell pathway in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2015;27:127–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Menon B, Gullick NJ, Walter GJ, Rajasekhar M, Garrood T, Evans HG, et al. Interleukin‐17+CD8+ T cells are enriched in the joints of patients with psoriatic arthritis and correlate with disease activity and joint damage progression. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:1272–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mease PJ, Kivitz AJ, Burch FX, Siegel EL, Cohen SB, Ory P, et al. Etanercept treatment of psoriatic arthritis: safety, efficacy, and effect on disease progression. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:2264–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Ritchlin CT, Ruderman EM, Steinfeld SD, Choy EH, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderately to severely active psoriatic arthritis: results of a double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3279–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mease PJ, Genovese MC, Greenwald MW, Ritchlin CT, Beaulieu AD, Deodhar A, et al. Brodalumab, an anti‐IL17RA monoclonal antibody, in psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Kirkham B, Kavanaugh A, Rahman P, van der Heijde D, et al. Secukinumab inhibition of interleukin‐17A in patients with psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1329–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mease PJ, van der Heijde D, Ritchlin CT, Okada M, Cuchacovich RS, Shuler CL, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin‐17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of biologic‐naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from the 24‐week randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled and active (adalimumab)‐controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT‐P1. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Antoni C, Krueger GG, de Vlam K, Birbara C, Beutler A, Guzzo C, et al. Infliximab improves signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: results of the IMPACT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1150–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kavanaugh A, McInnes I, Mease P, Krueger GG, Gladman D, Gomez‐Reino J, et al. Golimumab, a new human tumor necrosis factor α antibody, administered every four weeks as a subcutaneous injection in psoriatic arthritis: twenty‐four‐week efficacy and safety results of a randomized, placebo‐controlled study. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:976–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen DY, Chen YM, Chen HH, Hsieh CW, Lin CC, Lan JL. Increasing levels of circulating Th17 cells and interleukin‐17 in rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to anti‐TNF‐α therapy. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:R126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hull DN, Williams RO, Pathan E, Alzabin S, Abraham S, Taylor PC. Anti‐tumour necrosis factor treatment increases circulating T helper type 17 cells similarly in different types of inflammatory arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol 2015;181:401–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chabaud M, Miossec P. The combination of tumor necrosis factor α blockade with interleukin‐1 and interleukin‐17 blockade is more effective for controlling synovial inflammation and bone resorption in an ex vivo model. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:1293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sakellariou GT, Sayegh FE, Anastasilakis AD, Kapetanos GA. Leflunomide addition in patients with articular manifestations of psoriatic arthritis resistant to methotrexate. Rheumatol Int 2013;33:2917–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fraser AD, van Kuijk AW, Westhovens R, Karim Z, Wakefield R, Gerards AH, et al. A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, multicentre trial of combination therapy with methotrexate plus ciclosporin in patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:859–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baranauskaite A, Raffayova H, Kungurov N, Kubanova A, Venalis A, Helmle L, et al. Infliximab plus methotrexate is superior to methotrexate alone in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis in methotrexate‐naive patients: the RESPOND study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:541–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Genovese MC, Cohen S, Moreland L, Lium D, Robbins S, Newmark R, et al. Combination therapy with etanercept and anakinra in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have been treated unsuccessfully with methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:1412–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weinblatt M, Combe B, Covucci A, Aranda R, Becker JC, Keystone E. Safety of the selective costimulation modulator abatacept in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving background biologic and nonbiologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs: a one‐year randomized, placebo‐controlled study. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2807–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weinblatt M, Schiff M, Goldman A, Kremer J, Luggen M, Li T, et al. Selective costimulation modulation using abatacept in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis while receiving etanercept: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:228–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Greenwald MW, Shergy WJ, Kaine JL, Sweetser MT, Gilder K, Linnik MD. Evaluation of the safety of rituximab in combination with a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor and methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results from a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:622–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hsieh CM, Cuff C, Tarcsa E, Hugunin M. FRI0303 discovery and characterization of ABT‐122, an anti‐TNF/IL‐17 DVD‐IG molecule as a potential therapeutic candidate for rheumatoid arthritis [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;7 Suppl:495. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mansikka H, Ruzek M, Hugunin M, Ivanov A, Brito A, Clabbers A, et al. FRI0164 safety, tolerability, and functional activity of ABT‐122, a dual TNF‐ and IL‐17A–targeted DVD‐IG, following single‐dose administration in healthy subjects [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74 Suppl 2:482–3. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaymakcalan Z, Sakorafas P, Bose S, Scesney S, Xiong L, Hanzatian DK, et al. Comparisons of affinities, avidities, and complement activation of adalimumab, infliximab, and etanercept in binding to soluble and membrane tumor necrosis factor. Clin Immunol 2009;131:308–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu L, Lu J, Allan BW, Tang Y, Tetreault J, Chow CK, et al. Generation and characterization of ixekizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that neutralizes interleukin‐17A. J Inflamm Res 2016;9:39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khatri A, Goss S, Jiang P, Mansikka H, Othman AA. Pharmacokinetics of ABT‐122, a TNF‐α‐ and IL‐17A‐targeted dual‐variable domain immunoglobulin, in healthy subjects and patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from three phase I trials. Clin Pharmacokinet 2018;57:613–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fleischmann RM, Wagner F, Kivitz AJ, Mansikka HT, Khan N, Othman AA, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacodynamics of ABT‐122, a TNF– and IL‐17–targeted dual variable domain immunoglobulin, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:2283–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Genovese MC, Weinblatt M, Aelion JA, Mansikka HT, Peloso PM, Chen K, et al. ABT‐122, a bispecific dual variable domain immunoglobulin targeting tumor necrosis factor and interleukin‐17A, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to methotrexate. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018;70:1710–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Genovese MC, Weinblatt ME, Mease PJ, Aelion JA, Peloso PM, Chen K, et al. Dual inhibition of tumour necrosis factor and interleukin‐17A with ABT‐122: open‐label long‐term extension studies in rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018. E‐pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, Marchesoni A, Mease P, Mielants H, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2665–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Furst D, Goldsmith C, et al. American College of Rheumatology preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:727–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Prevoo ML, van ‘t Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty‐eight–joint counts: development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:44–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis—oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica 1978;157:238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Daltroy LH, Larson MG, Roberts NW, Liang MH. A modification of the Health Assessment Questionnaire for the spondyloarthropathies. J Rheumatol 1990;17:946–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maksymowych WP, Mallon C, Morrow S, Shojania K, Olszynski WP, Wong RL, et al. Development and validation of the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) Enthesitis Index. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:948–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Woodworth T, Furst DE, Alten R, Bingham CO III, Yocum D, Sloan V, et al. Standardizing assessment and reporting of adverse effects in rheumatology clinical trials II: the Rheumatology Common Toxicity Criteria v. 2.0. J Rheumatol 2007;34:1401–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Khatri A, Othman AA. Population pharmacokinetics of the TNF‐α and IL‐17A dual‐variable domain antibody ABT‐122 in healthy volunteers and subjects with psoriatic or rheumatoid arthritis: analysis of phase 1 and 2 clinical trials. J Clin Pharmacol 2018;58:803–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Taltz (ixekizumab) prescribing information. Indianapolis (IN): Eli Lilly and Company; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cosentyx (secukinumab) prescribing information. East Hanover (NJ): Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Georgantas RW, Ruzek M, Davis JW, Hong F, Asque E, Idler K, et al. Genomic and epigenetic bioinformatics demonstrate dual TNF‐α and IL17a target engagement by ABT‐122, and suggest mainly TNF‐α–mediated relative target contribution to drug response in MTX‐IR rheumatoid arthritis patients [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68 Suppl 10 URL: http://acrabstracts.org/abstract/genomic-and-epigenetic-bioinformatics-demonstrate-dual-tnf-%CE%B1-and-il17a-target-engagement-by-abt-122-and-suggest-mainly-tnf-%CE%B1-mediated-relative-target-contribution-to-drug-response-i/. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, Reich K, Griffiths CE, Papp K, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med 2014;371:326–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Langley RG, Luger T, Ohtsuki M, et al. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2016;375:345–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Genovese MC, Durez P, Richards HB, Supronik J, Dokoupilova E, Mazurov V, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a phase II, dose‐finding, double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:863–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pavelka K, Chon Y, Newmark R, Lin SL, Baumgartner S, Erondu N. A study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of brodalumab in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. J Rheumatol 2015;42:912–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lowes MA, Kikuchi T, Fuentes‐Duculan J, Cardinale I, Zaba LC, Haider AS, et al. Psoriasis vulgaris lesions contain discrete populations of Th1 and Th17 T cells. J Invest Dermatol 2008;128:1207–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Harper EG, Guo C, Rizzo H, Lillis JV, Kurtz SE, Skorcheva I, et al. Th17 cytokines stimulate CCL20 expression in keratinocytes in vitro and in vivo: implications for psoriasis pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol 2009;129:2175–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Johansen C, Usher PA, Kjellerup RB, Lundsgaard D, Iversen L, Kragballe K. Characterization of the interleukin‐17 isoforms and receptors in lesional psoriatic skin. Br J Dermatol 2009;160:319–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials