Summary

Background

Although the FibroTest has been validated as a biomarker to determine the stage of fibrosis in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) with results similar to those in chronic hepatitis C (CHC), B (CHB), and alcoholic liver disease (ALD), it has not yet been confirmed for the prediction of liver‐related death.

Aim

To validate the 10‐year prognostic value of FibroTest in NAFLD for the prediction of liver‐related death.

Method

Patients in the prospective FibroFrance cohort who underwent a FibroTest between 1997 and 2012 were pre‐included. Mortality status was obtained from physicians, hospitals or the national register. Survival analyses were based on univariate (Kaplan‐Meier, log rank, AUROC) and multivariate Cox risk ratio taking into account age, sex and response to anti‐viral treatment as covariates. The comparator was the performance of the FibroTest in CHC, the most validated population.

Results

7082 patients were included; 1079, 3449, 2051, and 503 with NAFLD, CHC, CHB, and ALD, respectively. Median (range) follow‐up was 6.0 years (0.1‐19.3). Ten year survival (95% CI) without liver‐related death in patients with NAFLD was 0.956 (0.940‐0.971; 38 events) and 0.832 (0.818‐0.847; 226 events; P = 0.004) in CHC. The prognostic value (AUROC / Cox risk ratio) of FibroTest in patients with NAFLD was 0.941 (0.905‐0.978)/1638 (342‐7839) and even higher than in patients with CHC 0.875 (0.849‐0.901; P = 0.01)/2657 (993‐6586).

Conclusions

The FibroTest has a high prognostic value in NAFLD for the prediction of liver‐related death. (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01927133).

1. INTRODUCTION

The FibroTest has been validated as a biomarker for the diagnosis of the stages of fibrosis in NAFLD1, 2 with results similar to those in CHC,3, 4, 5 CHB,5, 6 and ALD,7, 8 although no study has validated its prognostic value for liver‐related death. This could be due to the natural history of NAFLD, with lower incidence of liver‐related death and higher non‐liver‐related causes of mortality in comparison with the viral or alcoholic liver diseases. In a study of FibroTest in 2312 patients with type 2 diabetes or dyslipidemias, we found a significant prognostic value of FibroTest, for the overall survival.9 In type 2 diabetes, FibroTest predicted cardiovascular events and improved the Framingham‐risk score. For the prediction of liver‐related death the number of events at 10 years was too small (n = 7) for any conclusion. Therefore, the primary aim was to assess the prognostic value on liver‐related death, and we focused on subjects of the FibroFrance program followed since 1997 in the department of Hepatology for chronic liver diseases in Pitié‐Salpêtrière hospital), and compared the performances of FibroTest in NAFLD to those of CHC, in order to have a sufficient sample size.

The second aim was to assess the prognostic values of apolipoprotein‐A1 (ApoA1) and haptoglobin, two hepatoprotective proteins10, 11, 12, 13 also associated with lower risk of non‐liver mortality, including cancer and cardiovascular related deaths. The third aim was to assess the prognostic performance of two new quantitative tests, assessing the severity of NASH (NashTest‐2)14 and of steatosis (SteatoTest‐2).14

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

The design was an analysis of fresh serum specimen recorded in a non‐interventional prospective cohort. Patients followed by the Hepatology department were from the “Groupe Hospitalier Pitié Salpêtrière cohort” of FIBROFRANCE, a program organized in 1997 to assess the burden of chronic liver diseases in France (Clinical trial French registry no.: DRCD‐2013‐1 and ClinicalTrials.org no.:CT01927133). STROBE statements were followed (Table S1). The protocol was approved by the institutional review board, regulatory agency and performed in accordance with principles of Good Clinical Practice. All patients provided written informed consent before entry. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

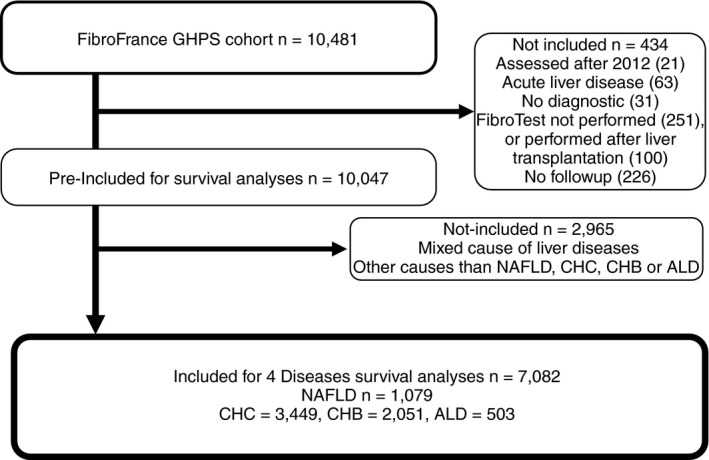

Patients with a FibroTest performed before 2013, without previous liver transplantation, and without acute liver disease, were selected (Figure 1). Follow‐up and treatments were scheduled according to the updated international guidelines.15, 16 In patients with baseline cirrhosis ultrasonography (US) examination was performed every 6 months, and AFP was recommended every 6 months.

Figure 1.

Flow sheet of population subsets

2.2. Non‐invasive liver biomarkers

FibroTest (BioPredictive Paris,France;FibroSURE LabCorp Burlington, NC, USA) is a in vitro multi‐analyte serum test including the serum concentrations of α2‐macroglobulin, apolipoprotein A1, haptoglobin, total bilirubin, and GGT, adjusted for age and gender. Alpha‐2‐macroglobulin, apolipoprotein A1 and haptoglobin were measured using an automatic nephelometer BNII (Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany). The recommended pre‐analytical and analytical procedures were applied.17 The scores of these biomarkers range from 0 to 1.00, the highest scores being attributed to the most severe lesions.

To compare the FibroTest use in our cohort since 1997, to other tests which were validated in 2005 for transient elastography‐probe‐M (TE) and 2006 for FIB4, we performed a post hoc analysis of FIB4 performance cases with NAFLD who had simultaneous measurements of TE and FIB4.

To assess the possible impact of NASH or Steatosis on the survival, we also assessed as possible risk factors two validated updated blood tests, the NashTest‐2 and the SteatoTest‐2. NashTest‐2 combined 11 components with different weights, including the seven components of FibroTest, plus alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, cholesterol and triglycerides.13 SteatoTest‐2 combined with different weights, 10 out of the 11 components of NashTest‐2, without bilirubin, but with fasting glucose.14

2.3. Follow‐up and outcomes

Patients attended the Hepatology Department when justified by abnormal liver tests, or at least once a year in case of cirrhosis. The duration of follow‐up was calculated from the baseline date, defined as the date when the serum used for their first analyses of liver biomarkers was collected, to the date of a lethal event occurred. Survivals were not censored at transplantation time. This interval was censored at the time of last follow‐up.

The mortality rate and incidence of cardiovascular events were determined during follow‐up. The causes of death were collected from the French national registry (CepiDc Inserm), according to the 10th International classification of Diseases. Mortality status obtained by physician, hospital or national register.

Cause of death was classified as liver‐related, cardiovascular‐related, cancer‐related, and others, according to WHO codes (who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010). The codes considered as diagnosis of cardiovascular‐related death were: ischemic heart diseases (I20‐I25), cardiac arrest (I46), heart failure (I50), cerebrovascular diseases (I63 and I64) and cardiogenic shock (R57.0). The codes for liver‐related death were: liver fibrosis and cirrhosis of liver (K74), non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis (K75.8), portal hypertension (K76.6), oesophageal varices bleeding (I85.0), hepatocellular carcinoma (C22.0) and cholangiocarcinoma (C22.1). Death coded as R99 (other ill‐defined and unspecified causes of mortality) was considered as unknown cause of death.

2.4. Statistical methods

Survival analyses (events defined as death) were based on univariate (Kaplan‐Meier, Logrank, time‐dependent area under the ROC curve AUROC), and multivariate Cox‐risk‐ratio analyses, taking into account age, gender and response to antiviral treatment as covariates. The independent prognostic value of each FibroTest component was assessed for each liver disease. The main endpoint was the performance of the FibroTest for liver‐related death in NAFLD, compared to results observed in CHC, the most validated population.

The association between ApoA1, haptoglobin and the non‐liver causes of deaths (cardiovascular and non‐liver cancer‐related deaths), were assessed by AUROCs and Cox univariate and multivariate analyses, including three major prognostic factors, age, gender and A2M as marker of cirrhosis. To prevent colinearity, FibroTest was not used as a marker of cirrhosis as ApoA1 and haptoglobin were components of FibroTest.

In sensitivity analyses, we performed multivariate Cox models to assess if the FibroTest significant prognostic value at 10‐year persisted after adjustment by gender, BMI (cutoff = 27 kg/m2), and T2‐diabetes, in NAFLD compared to CHC. Analyses were repeated after exclusion of NAFLD patients with alcohol consumption missing, or with rare alcohol consumption but under the standard definition of consumption at risk (daily alcohol consumption ≥30 g for men and ≥20 g for women), and also after excluding patients with HIV‐PCR missing or positive.

All statistical analyses were performed using NCSS‐12.0 and R softwares, including timeROC library.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of included subjects

After the exclusion of 434 patients mainly due to previous transplantation, absence of baseline fibrosis biomarker and absence of follow‐up, and 2965 patients with mixed or other causes of chronic liver disease, a total of 7082 patients with NAFLD (n = 1079), CHC (n = 3449), CHB (n = 2051), and ALD (n = 503) were included (Figure 1). Besides the causes of liver disease there was no significant differences between the pre‐included and included subset characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients according to populations at inclusion

| GHPS cohort pre‐included | NAFLD, CHC, CHB, ALD | NAFLD only | CHC only | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | 10 481 (100%) | 7082 (100%) | 1079 (100%) | 3449 (100%) |

| Age median (interquartile) | 48.8 (39.5‐59.0) | 47.6 (39.0‐57.6) | 56.7 (48.4‐64.7) | 48.0 (41.0‐57.5) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female number (percent) | 4168 (39.6) | 2678 (37.8) | 463 (42.9) | 1423 (41.3) |

| Male | 6313 (60.4) | 4404 (62.2) | 616 (57.1) | 2026 (58.7) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Asian | 870 (8.5) | 708 (10.0) | 67 (6.2) | 181 (5.3) |

| Caucasian | 6392 (62.4) | 4112 (58.1) | 819 (75.9) | 2363 (68.5) |

| North‐African to Middle East origin | 1173 (11.5) | 806 (11.4) | 112 (10.4) | 439 (12.7) |

| Subsaharan | 1810 (17.7) | 1456 (20.5) | 81 (7.5) | 466 (13.5) |

| Missing | 236 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Liver disease | ||||

| ALD | 520 (5.0) | 503 (7.1) | 0 | 0 |

| CHB | 2079 (19.9) | 2051 (29.0) | 0 | 0 |

| CHC | 3554 (34.0) | 3449 (48.7) | 0 | 3449 (100) |

| NAFLD | 1233 (11.8) | 1079 (15.2) | 1079 (100) | 0 |

| Other and mixed | 3064 (29.3) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Viral suppression | ||||

| No suppression | 7935 (75.7) | 4570 (64.5) | NA | 2992 (86.7) |

| Suppression inclusion | 2546 (24.3) | 2512 (35.4) | NA | 457 (13.3) |

| Excess alcohol | ||||

| Yes | 846 (8.7) | 799 (13.8) | 37 (4.5)a | 235 (8.5) |

| No | 6532 (91.3) | 4982 (86.2) | 792 (95.5) | 2517 (91.5) |

| Missing | 3103 | 1301 | 250 | 697 |

| HIV infection | ||||

| Yes | 728 (7.4) | 643 (5.6) | 12 (1.1) | 454 (14.8) |

| No | 9157 (92.6) | 6041 (90.4) | 1061 (98.9) | 2610 (85.2) |

| Missing | 596 | 398 | 6 | 385 |

| Type 2 diabetes | ||||

| Yes | 967 (9.2) | 832 (11.8) | 386 (35.8) | 267 (7.7) |

| No | 9514 (90.8) | 6250 (88.2) | 693 (64.2) | 3182 (92.3) |

| Fibrosis stage by FibroTest | 10230 | 7082 | 1079 | 3449 |

| Missing or not applicable | 251 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F0 | 4882 (47.7) | 3105 (43.8) | 633 (58.7) | 1143 (33.1) |

| F1 | 1958 (19.1) | 1364 (19.3) | 217 (20.1) | 682 (19.8) |

| F2 | 735 (7.2) | 574 (8.1) | 70 (6.5) | 349 (10.1) |

| F3 | 1075 (10.5) | 833 (11.8) | 81 (7.5) | 516 (15.0) |

| Cirrhosis (F4) | 1581 (15.5) | 1206 (17.0) | 78 (7.2) | 759 (22.0) |

| F4.1 (>0.74‐0.85) | 640 (6.3) | 496 (7.0) | 38 (3.5) | 341 (9.9) |

| F4.2 (>0.85‐0.95) | 614 (6.0) | 471 (6.6) | 25 (2.5) | 298 (8.6) |

| F4.3 (>0.95‐1.00) | 327 (3.2) | 239 (3.4) | 15 (1.4) | 120 (3.5) |

| FibroTest | 0.30 (0.15‐0.59) | 0.34 (0.16‐0.63) | 0.24 (0.13‐0.43) | 0.45 (0.21‐0.71) |

| ActiTest | 0.23 (0.11‐0.47) | 0.26 (0.12‐0.50) | 0.22 (0.11‐0.39 | 0.36 (0.18‐0.61) |

| ApolipoproteinA1 | 1.45 (1.22‐1.68) | 1.45 (1.24‐1.68) | 1.48 (1.24‐1.68) | 1.45 (1.24‐1.71) |

| Haptoglobin | 1.01 (0.63‐1.44) | 0.95 (0.59‐1.35) | 1.23 (0.88‐1.64) | 0.90 (0.56‐1.28) |

| A2M | 2.06 (1.59‐2.82) | 2.24 (1.68‐2.97) | 1.70 (1.36‐2.21) | 2.66 (1.94‐3.39) |

| GGT | 46 (25‐107) | 46 (25‐100) | 58 (33‐124) | 53 (28‐108) |

| Bilirubin | 9 (7‐14) | 10 (7‐15) | 9 (6‐13) | 10 (7‐14) |

| ALT | 39 (25‐68) | 41 (26‐70) | 39 (26‐60) | 53 (32‐87) |

| Deaths | 1541 (14.9) | 1026 (14.5) | 240 (22.2) | 449 (13.0) |

| Liver‐related | 564 (5.4) | 457 (6.5) | 38 (3.5) | 226 (6.6) |

| Cardiovascular | 203 (1.9) | 117 (1.7) | 52 (4.8) | 40 (1.2) |

| Non‐liver cancer | 329 (3.1) | 179 (2.5) | 69 (6.4) | 63 (1.8) |

| Other causes | 223 (2.1) | 141 (2.0) | 49 (4.5) | 56 (1.6) |

These patients with NAFLD had rare alcohol consumption but under the standard definition of consumption at risk (mean daily alcohol consumption ≥30 g for men and ≥20 g for women).

Between patients with NAFLD patients and those of the comparator group with CHC there were two main significant differences associated with the prognosis, one negatively associated, an older age (median 56.7 years old; IQR 48.4‐64.7) vs 48.0 (41.0‐57.5; P < 0.001), and one positively associated, the lower severity of fibrosis presumed by FibroTest (median; IQR) 0.24; 0.13‐0.43 vs 0.45 (0.21‐0.71) including a lower prevalence of cirrhosis 6.8% vs 22.0% (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

3.2. Survivals

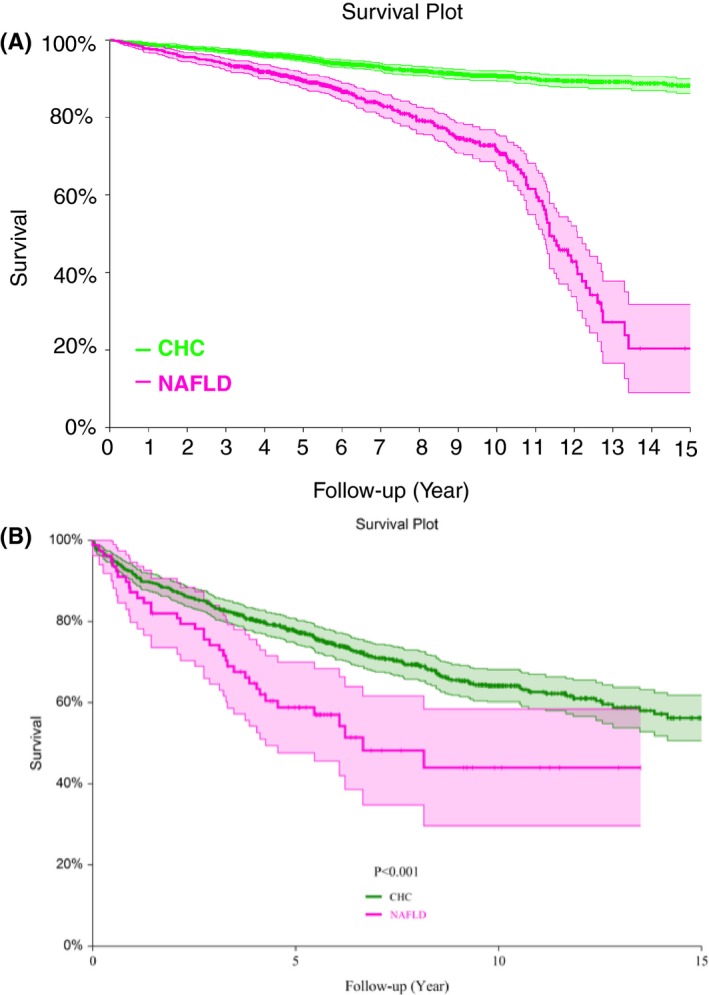

The median (range) follow‐up was 6.0 years (0.1‐19.3), with a 15‐year‐overall survival of 0.725 (0.704‐0.746) among the 10 047 pre‐included patients (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Survivals. All survivals were unadjusted Kaplan‐Meier curves. A, 10‐year‐overall survival was 0.824 (0.813‐0.835) among the 7082 included patients. B, 10‐year‐overall survival in NAFLD was 0.689 (0.647‐0.730), lower than 0.832 (0.818‐0.847) in CHC, and 0.891 (0.891‐0.922) in CHB, but much higher than in ALD 0.408 (0.345‐0.472). All P < 0.001. C, 10 year‐liver‐related survival was, in NAFLD 0.956 (0.940‐0.971), higher than 0.921 (0.910‐0.932; P = 0.004) in CHC, slightly lower than 0.969 (0.960‐0.979; P = 0.04) in CHB, but much greater than in ALD 0.585 (0.515 0.655; P < 0.001).

The 10 year‐overall‐survivals according to the four chronic liver diseases included were all significantly different (P < 0.001), in NAFLD 0.689 (0.647‐0.730), lower than 0.832 (0.818‐0.847) in CHC, and 0.891 (0.891‐0.922) in CHB, but much higher than in ALD 0.408 (0.345‐0.472) (Figure 2B).

The 10 year‐liver‐related survivals according to the four chronic liver diseases included were, in NAFLD 0.956 (0.940‐0.971), higher than 0.921 (0.910‐0.932; P = 0.004) in CHC, slightly lower than 0.969 (0.960‐0.979; P = 0.04) in CHB, but much higher than in ALD 0.585 (0.515‐0.655; P < 0.001) (Figure 2C).

The overall survival of patients with NAFLD was lower than in patients with CHC since the fifth year of follow‐up. This was not explained by a difference in cirrhosis prevalence at baseline (Figure 3A,B). This difference was explained by the older age in NAFLD vs CHC patients, and the associated non‐liver‐related deaths.

Figure 3.

Overall survivals according to presence or absence of cirrhosis at baseline. Patients with NAFLD had lower survivals whatever the absence or presence of cirrhosis. A, Patients without cirrhosis at baseline. B, Patients with cirrhosis at baseline

There was a dramatic difference in the survivals among NAFLD patients 50 years of age or older (Figure S1A), mainly due to the number of non‐liver‐related cancers (Figure S1B), and of the cardiovascular‐related deaths (Figure S1C), despite less liver‐related deaths in the CHC patients (Figure S1D).

Among patients younger than 50 years of age there was no difference between NAFLD vs CHC overall survivals (Figure S2A), including no difference between non‐liver‐related cancers deaths (Figure S2B), with an early difference in cardiovascular‐related deaths (Figure S2C), but compensated by less liver‐related deaths (Figure S2D).

3.3. FibroTest prognostic performance for survival without liver‐related deaths (primary endpoint)

Liver‐related deaths occurred in 38 cases (19 liver cancers, including 16 hepatocellular carcinoma and three intra‐hepatic‐ cholangiocarcinoma in NAFLD group vs 226 (87 liver cancers, including 84 hepatocellular and 3 cholangiocarcinoma) in the CHC group.

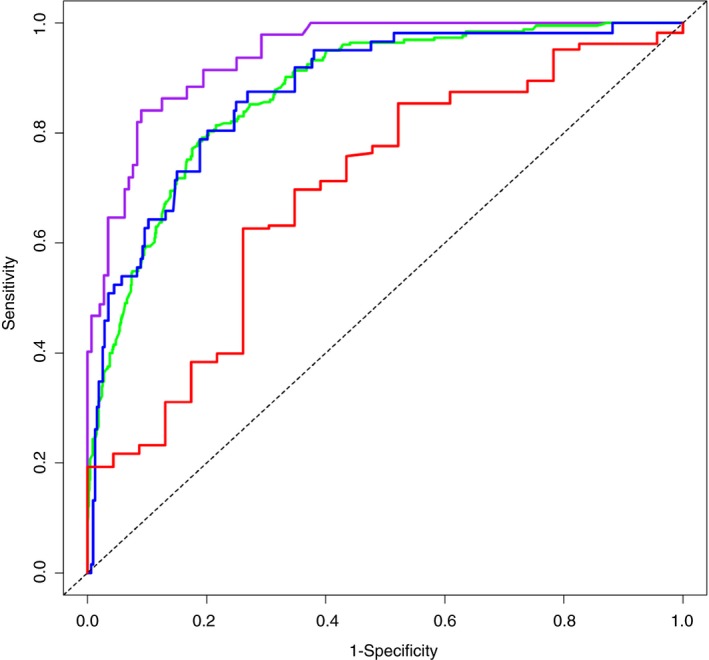

The prognostic values, AUROC (mean; 95% CI) and Cox‐risk‐ratio (mean; 95% CI) of FibroTest for the prediction of 10 year‐liver‐related survivals in 1079 patients with NAFLD were highly significant (P < 0.001) 0.941 (0.905‐0.978), 1224 (264‐5613), vs random. AUROC in NAFLD was higher than in 3449 CHC 0.875 (0.849‐0.901; P = 0.01), Cox‐risk‐ratio 1839 (721‐4690), not different than in 2051 CHB 0.848 (0.723‐0.974; P = 0.09), and then in 503 ALD, 0.695 (0.575‐0.816; P = 0.06) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Prognostic performances (AUROCs) of FibroTest. AUROC of FibroTest 0.941 (0.905‐0.978) (mean; 95% CI) purple line, for the prediction of 10 year‐liver‐related survivals in 1079 patients with NAFLD was significantly higher than in 2051 CHC 0.875 (0.849‐0.901; P = 0.01) green line, and not different than in 2051 CHB 0.848 (0.723‐0.974; P = 0.09) blue line, and then in 503 ALD, 0.695 (0.575‐0.816; P = 0.06) red line

Proportionality assumption was respected for the Cox model (Figure S3).

All the five quantitative components of FibroTest were associated (AUROCs) with liver‐related deaths both in NAFLD as in CHC (Table S2).

When post hoc analyses in the same patients compared FibroTest to FIB4 in 209 cases with NAFLD (29 liver related‐deaths), there was no significant difference in AUROCs, FibroTest (0.935; 0.876‐0.993) vs FIB‐4 (0.866; 0.739‐0.994; P = 0.32). There was also no significant difference in AUROCs, in 401 cases (7 liver related‐deaths), FibroTest (0.939; 0.859‐1.00) vs transient elastography (0.923; 0.790‐1.00; P = 0.72). The applicability of TE‐M was only 74.3% (436/587) (Table S3).

3.4. FibroTest prognostic value for survival without non‐liver‐related deaths

Deaths from any causes occurred in NAFLD 240 patients vs 449 in the CHC group. The AUROC for the prediction of overall‐survival in patients with NAFLD was low, 0.507 (0.443‐0.571) and much lower than its AUROC in patients with CHC, 0.738 (0.708‐0.768; P < 0.001), as expected according to the higher prevalence of liver‐related deaths in CHC (6.6%, n = 226) vs NAFLD (3.5%, n = 38) (Table 1).

Cardiovascular‐related deaths occurred in 52 NAFLD vs 40 CHC patients. AUROC for the prediction of survival without cardiovascular deaths in patients with NAFLD was significant vs random, 0.584 (0.478‐0.6921) and not different than in CHC, 0.614 (0.525‐0.703; P = 0.73).

Non‐liver‐cancer‐related deaths occurred in 69 NAFLD vs 63 CHC patients. FibroTest had no significant predictive value for survival without non‐liver‐cancer‐related deaths in patients with NAFLD, AUROC = 0.370 (0.275‐0.463), and was significant in CHC, 0.613 (0.535‐0.690; P = 0.001). In the 69 patients with NAFLD and non‐liver‐cancer‐related deaths, the prevalences of different type of cancers were expected in comparison with the general population prevalences, and without difference with those observed in CHC.

Other‐related deaths occurred in 81 NAFLD vs120 CHC patients. FibroTest had no significant predictive value for survival without other‐related deaths in patients with NAFLD 0.398 (0.307‐0.489) and was significant in CHC, 0.580 (0.524‐0.638; P = 0.002).

3.5. Number of events and cumulative probability of death according to Fibrotest cutoffs

Most of the 10‐yr mortality in cirrhotic patients was related to liver‐related deaths both in NAFLD and CHC. In non‐cirrhotic patients, whatever the stages of fibrosis presumed by FibroTest, there was a lower mortality related to liver deaths in NAFLD as compared to CHC (Table S4).

3.6. ApoA1 and haptoglobin prognostic values for survival without liver‐related deaths

Low ApoA1 was associated in patients with NAFLD, with cardiovascular‐related deaths (P = 0.009) (Table 2A), and with all causes of deaths (P < 0.001) (Table 2), independently of age, gender, and fibrosis severity estimated by A2M. In CHC ApoA1 was associated with non‐liver‐related cancer death and all causes of death (Table 3).

Table 2.

Prognostic values (Cox model) of ApoA1 and haptoglobin in NAFLD patients. (A) ApoA1 in NAFLD patients (n = 1079) and cardiovascular deaths (n = 52). (B) Hapto in NAFLD patients (n = 1079) and cardiovascular deaths (n = 52). (C) ApoA1 in NAFLD patients (n = 1079) and non‐liver cancer deaths (n = 69). (D) Hapto in NAFLD patients (n = 1079) and non‐liver cancer deaths (n = 69). (E) ApoA1 in NAFLD patients (n = 1079) and all deaths (n = 240). (F) Hapto in NAFLD patients (n = 1079) and all deaths (n = 240)

| Variable | Exp(B) | 95% CI | P‐value | R² |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | ||||

| ApoA1neg | 3.366 | 1.357‐8.351 | 0.009 | 0.058 |

| A2M | 1.637 | 0.273‐9.817 | 0.590 | 0.003 |

| Age | 1.070 | 1.042‐1.098 | 0.000 | 0.189 |

| Male gender | 2.094 | 1.074‐4.084 | 0.030 | 0.040 |

| (B) | ||||

| Hapto neg | 0.566 | 0.203‐1.578 | 0.277 | 0.010 |

| A2M | 1.772 | 0.299‐10.510 | 0.529 | 0.004 |

| Age | 1.068 | 1.040‐1.097 | 0.000 | 0.174 |

| Male gender | 2.740 | 1.436‐5.228 | 0.002 | 0.077 |

| (C) | ||||

| ApoA1neg | 0.913 | 0.410‐2.036 | 0.825 | 0.000 |

| A2M | 0.232 | 0.040‐1.332 | 0.101 | 0.021 |

| Age | 1.056 | 1.033‐1.080 | 0.000 | 0.150 |

| Male gender | 0.989 | 0.591‐1.655 | 0.965 | 0.000 |

| (D) | ||||

| Hapto neg | 0.135 | 0.039‐0.474 | 0.002 | 0.071 |

| A2M | 0.256 | 0.047‐1.397 | 0.115 | 0.019 |

| Age | 1.054 | 1.030‐1.078 | 0.000 | 0.140 |

| Male gender | 1.000 | 0.616‐1.624 | 0.999 | 0.000 |

| (E) | ||||

| ApoA1neg | 2.659 | 1.733‐4.078 | 0.000 | 0.065 |

| A2M | 1.968 | 0.845‐4.584 | 0.117 | 0.008 |

| Age | 1.058 | 1.046‐1.071 | 0.000 | 0.235 |

| Male gender | 1.244 | 0.938‐1.651 | 0.130 | 0.008 |

| (F) | ||||

| Hapto neg | 0.465 | 0.278‐0.776 | 0.003 | 0.029 |

| A2M | 2.076 | 0.902‐4.776 | 0.086 | 0.010 |

| Age | 1.056 | 1.044‐1.069 | 0.000 | 0.215 |

| Male gender | 1.566 | 1.195‐2.051 | 0.001 | 0.035 |

Table 3.

Prognostic values (Cox model) of ApoA1 and haptoglobin in CHC patients. (A) ApoA1 in CHC patients (n = 3349) and cardiovascular deaths (n = 40). (B) Hapto in CHC patients (n = 3349) and cardiovascular deaths (n = 40). (C) ApoA1 in CHC patients (n = 3349) and non‐liver cancer deaths (n = 63). (D). Hapto in CHC patients (n = 3349) and non‐liver cancer deaths (n = 63). (E) ApoA1 in CHC patients (n = 3349) and all deaths (n = 449). (F) Hapto in CHC patients (n = 3349) and all deaths (n = 449)

| Variable | Exp(B) | 95% CI | P‐value | R² |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | ||||

| ApoA1neg | 1.787 | 0.712‐4.484 | 0.216 | 0.007 |

| A2M | 0.444 | 0.055‐3.598 | 0.447 | 0.003 |

| Age | 1.072 | 1.046‐1.100 | 0.000 | 0.123 |

| Male gender | 2.413 | 1.157‐5.032 | 0.019 | 0.025 |

| (B) | ||||

| Hapto neg | 0.287 | 0.093‐0.893 | 0.031 | 0.021 |

| A2M | 0.538 | 0.064‐4.503 | 0.568 | 0.002 |

| Age | 1.070 | 1.044‐1.098 | 0.000 | 0.115 |

| Male gender | 2.679 | 1.320‐5.439 | 0.006 | 0.034 |

| (C) | ||||

| ApoA1neg | 2.572 | 1.243‐5.323 | 0.011 | 0.027 |

| A2M | 1.084 | 0.201‐5.840 | 0.925 | 0.000 |

| Age | 1.047 | 1.026‐1.069 | 0.000 | 0.078 |

| Male gender | 1.395 | 0.805‐2.419 | 0.236 | 0.006 |

| (D) | ||||

| Hapto neg | 0.337 | 0.139‐0.816 | 0.016 | 0.024 |

| A2M | 1.321 | 0.240‐7.260 | 0.749 | 0.000 |

| Age | 1.045 | 1.024‐1.067 | 0.000 | 0.071 |

| Male gender | 1.689 | 0.994‐2.870 | 0.053 | 0.016 |

| (E) | ||||

| ApoA1neg | 5.590 | 4.298‐7.271 | 0.000 | 0.215 |

| A2M | 1.766 | 0.937‐3.327 | 0.079 | 0.005 |

| Age | 1.053 | 1.045‐1.060 | 0.000 | 0.233 |

| Male gender | 1.434 | 1.164‐1.767 | 0.001 | 0.019 |

| (E) | ||||

| Hapto neg | 2.224 | 1.777‐2.783 | 0.000 | 0.075 |

| A2M | 1.268 | 0.662‐2.431 | 0.474 | 0.001 |

| Age | 1.052 | 1.044‐1.060 | 0.000 | 0.223 |

| Male gender | 2.052 | 1.674‐2.516 | 0.000 | 0.074 |

High haptoglobin was associated in patients with NAFLD, with cardiovascular‐related deaths (P = 0.03) (Table 2B), and with all causes of deaths (P = 0.003) (Table 2F), independently of age, gender and fibrosis severity estimated by A2M. In CHC high haptoglobin was associated with cardiovascular‐related deaths, and with non‐liver‐related cancer death (Table 2D). In CHC, and contrarily to NAFLD low haptoglobin was associated with all causes of death, as expected by the high prevalence of liver‐related deaths in CHC and the low level of haptoglobin in cirrhosis (Table 3).

3.7. Prognostic performance of NASH or Steatosis biomarkers

A total of 680 patients with NAFLD had FibroTest together with new NashTest‐2 and SteatoTest‐2 (Table S5). For liver‐related deaths, in univariate analysis, despite the limited number of events (n = 17) the two biomarkers of NAFLD had significant predictive value, but only the significance of NashTest‐2 persisted when adjusted on FibroTest (Table S5B). The other causes of deaths were not associated with elevated NashTest‐2 or SteatoTest‐2. For all causes of deaths, there was even a negative association with NashTest, significant both in uni and multivariate analyses (Table S5C,D).

3.8. Prediction of deaths among patients with cirrhosis

Staging of NAFLD into seven categories using FibroTest predicted decreasing 5‐year survival without related‐deaths in F4.3 vs F4.2 and F4.1 as validated previously in CHC and CHB (Figure S5).

3.9. Sensitivity analyses

Exclusion of NAFLD patients with alcohol consumption missing (n = 250), or with rare alcohol consumption but under the standard definition of consumption at risk (daily alcohol consumption ≥30 g for men and ≥20 g for women) (n = 37) (Table S6), or with missing or positive HIV PCR (n = 18) (Table S7) does not change significantly the mains comparisons between survivals or the prognostic performances of FibroTest.

The multivariate analyses showed that the FibroTest significant prognostic value at 10‐year persisted after adjustment by gender, BMI (cutoff = 27 kg/m2), and T2‐diabetes, in NAFLD compared to CHC.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we validated the performance of FibroTest for the prognostic of patients with NAFLD, both for the survival without liver‐related deaths the primary aim, and for the overall survival. We also confirm that FibroTest has prognostic value for cardiovascular‐related deaths in patients with NAFLD, mainly due to the prognostic value of ApoA1.

This long‐term follow‐up of a prospective cohort has several strengths and limitations.

4.1. Strengths

The first strength was the sample size and the long‐term follow‐up, which permitted to analyse a total of 240 deaths in the NAFLD group including 38 liver‐related deaths, much more than in our previous study in two different cohorts which analysed 172 deaths with only seven liver‐related deaths.9 The only other long‐term prognostic study published included 360 patients with NAFLD and analysed 83 deaths with 17 liver‐related deaths.18 Without a direct comparison of tests in the same patients, in intention to diagnose analysis, it is hazardous to compare indirectly the non‐invasive biomarkers.5 However, the AUROC of FibroTest 0.941 (0.905‐0.978) for liver‐related deaths, observed in our cohort seems in the upper range of the performances observed in the other study, 0.853 (0.738‐0.938) for the best patented blood test (Hepascore), 0.778 (0.663‐0.880) for the best non‐patented test (FIB4), and 0.885 (0.818‐0.947) for transient elastography.18 Here in the post hoc analyses, despite the low number of events, we retrieved same upper range of FibroTest vs FIB4 and transient elastography, in the same patients (AUROC = 0.943; 0.890‐0.971) vs FIB‐4 (0.906; 0.797‐0.957; P = 0.33), and 0.954 (0.865‐0.985) vs 0.903 (0.552‐0.982; P = 0.38) respectively.

For the first time, as presumed by quantitative blood tests, we were able to assess if the severity of NASH and steatosis at baseline were predictive of survivals, independently of baseline fibrosis severity. Indeed, in the subset population with all these tests, despite the limited number of events (n = 17) NashTest‐2 and SteatoTest‐2 had significant predictive value. As expected, only the significance of NashTest‐2 persisted when adjusted on FibroTest.

We confirmed our previous results in type 2‐diabetes, that FibroTest predicted cardiovascular events, and improved the Framingham‐risk score.9 For the first time we observed that FibroTest was also predictive of cardiovascular‐related deaths, both in NAFLD patients with and without diabetes and also among CHC patients.

There is evidence that low ApoA1 and low haptoglobin are two blood biomarkers of mortality risk, besides their performance for the diagnosis of cirrhosis.10, 11 They both mediate hepatoprotection. In healthy volunteers testing acetaminophen, these proteins were differentially expressed before acetaminophen intake in subjects with an increase in transaminases vs those without.19 Similarly, in patients with drug‐induced liver injury, higher serum levels of these proteins were predictive of transaminase recovery.12 We also recently observed that individuals with lower ApoA1 or haptoglobin could be at a higher risk of developing primary liver cancer, irrespective of the presence of cirrhosis (T. Poynard et al. unpublished data.) ApoA1 was associated with an increased risk of overall cancers in a meta‐analysis based on 28 epidemiologic studies as well as in a recent prospective cohort.10, 11 Here we also found a significant association between low ApoA1 and non‐liver‐related cancer deaths in CHC, but not in NAFLD patients. In NAFLD low ApoA1 was associated with all causes of death, and as expected, with cardiovascular mortality as extensively validated in patients with cardiovascular diseases.

For haptoglobin we found in NAFLD patients an unexpected association between high haptoglobin and cardiovascular deaths and all causes of deaths. We have no clear explanation of this association. Recent progress in the comprehension of the interactions of haptoglobin and ApoA1 in diabetics for the risk of cardiovascular mortality suggests first to analyse the prevalence of haptoglobin 2‐2 haplotype individuals among our patients with NAFLD.20, 21 In these individuals, the oxidative modification of ApoA1 appears to be responsible for inducing inflammation in diabetic individuals with haptoglobin 2‐2 genotype. In this scenario the “good cholesterol” (High Density Lipoprotein) can go “bad” and increase Low Density Lipoprotein‐induced inflammation (File S2).

4.2. Limitations

First, we have not performed an external validation. However, the prognostic value of FibroTest in NAFLD was already validated for overall survival and the risk of cardiovascular events in diabetic patients of the FibroFrance project,9 and its diagnostic performance has been extensively validated in NAFLD patients.16

Even if this study had the longest follow‐up and the higher number of events in comparison with the other published prognostic study in NAFLD, the number of events was still low. We found the same prevalence of primary liver cancer associated deaths than in the other prognostic studies, but more cases are needed to validate the prognostic value of biomarkers for liver cancer occurring in non‐cirrhotic NAFLD or for the prediction of cholangiocarcinoma.

We did not analyse the predictive value of evolving risk factors during follow‐up, such as alcohol intake or diabetes. We also did not analyse the predictive value of steatosis, being overweight, tobacco, coffee, chocolate or cannabis consumption, physical exercise or long‐term drug use, all factors that could be associated not only with fibrosis but also with cardiovascular deaths.

Finally, we did not compare the prognostic value of FibroTest with other patented blood tests, and the post hoc comparisons vs FIB4 and transient elastography, validated 8 years later than Fibrotest, had a limited statistical power. For diagnostic performances, no biomarkers or elastography methods have been demonstrated superior to FibroTest in face to face study, and using intention to diagnose analysis, for chronic viral hepatitis and alcoholic liver disease.5, 8, 16 To assess liver fibrosis in NAFLD, EASL guidelines recommends the use of either NAFLD‐Fibrosis‐score, FIB‐4 score, Fibrometer, ELF as well as Fibrotest. To assess the liver‐related prognosis in NAFLD there is so far no guidelines.

In Conclusion, the FibroTest has a high predictive value for survival without liver disease in patients with NAFLD, as already observed in chronic viral hepatitis and alcoholic liver disease.

AUTHORSHIP

Guarantor of the article: TP.

Author contributions: TP, MM: Experiment conception and design; TP, MM, VP, JM, MR, PL, FC, VT, OL, FIB, OR, DT, VR: Experiment performance; MM, TP, OD, YN, AN, FD: Data analysis; MM, TP, OD, CH: Drafting of the paper.

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declaration of personal interests: Thierry Poynard is the inventor of FibroTest test, founder of BioPredictive, the patent belong to the public organization Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris. Valentina Peta, Olivier Deckmyn, Mona Munteanu, Yen Ngo, and An Ngo are full employee of BioPredictive. The other authors have nothing to declare: Raluca Pais, Joseph Moussalli, Marika Rudler, Pascal Lebray, Frederic Charlotte, Vincent Thibault, Olivier Lucidarme, Françoise Imbert‐Bismut, Chantal Housset, Dominique Thabut, and Vlad Ratziu. Writing assistance: none.

Munteanu M, Pais R, Peta V, et al. Long‐term prognostic value of the FibroTest in patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease, compared to chronic hepatitis C, B, and alcoholic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:1117‐1127. 10.1111/apt.14990

Funding information

Valentina Peta, Olivier Deckmyn, Yen Ngo, An Ngo and Fabienne Drane Mona Munteanu, are full employees of BioPredictive.

The Handling Editor for this article was Professor Stephen Harrison, and it was accepted for publication after full peer‐review.

REFERENCES

- 1. Munteanu M, Tiniakos D, Anstee Q, et al. Diagnostic performance of FibroTest, SteatoTest and ActiTest in patients with NAFLD using the SAF score as histological reference. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:877‐889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Poynard T, Lassailly G, Diaz E, et al. Performance of biomarkers FibroTest, ActiTest, SteatoTest, and NashTest in patients with severe obesity: meta‐analysis of individual patient data. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Imbert‐Bismut F, Ratziu V, Pieroni L, et al. Biochemical markers of liver fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;357:1069‐1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chou R, Wasson N. Blood tests to diagnose fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:807‐820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Houot M, Ngo Y, Munteanu M, et al. Systematic review with meta‐analysis: direct comparisons of biomarkers for the diagnosis of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C and B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:16‐29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu XY, Kong H, Song RX, et al. The effectiveness of noninvasive biomarkers to predict hepatitis B‐related significant fibrosis and cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e100182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Naveau S, Essoh BM, Ghinoiu M, et al. Comparison of Fibrotest and PGAA for the diagnosis of fibrosis stage in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:404‐411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thiele M, Madsen BS, Hansen JF, et al. Accuracy of the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Test vs Fibrotest, elastography and indirect markers in detection of advanced fibrosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;5085:30016‐30017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Perazzo H, Munteanu M, Ngo Y, et al. FLIP Consortium. Prognostic value of liver fibrosis and steatosis biomarkers in type‐2 diabetes and dyslipidaemia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1081‐1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Melvin JC, Holmberg L, Rohrmann S, Loda M, Van Hemelrijck M. Serum lipid profiles and cancer risk in the context of obesity: four meta‐analyses. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;2013:823849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Katzke VA, Sookthai D, Johnson T, Kühn T, Kaaks R. Blood lipids and lipoproteins in relation to incidence and mortality risks for CVD and cancer in the prospective EPIC‐Heidelberg cohort. BMC Med. 2017;15:218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peta V, Tse C, Perazzo H, et al. Serum apolipoprotein A1 and haptoglobin, in patients with suspected drug‐induced liver injury (DILI) as biomarkers of recovery. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0189436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Poynard T, Munteanu M, Charlotte F, et al. Diagnostic performance of a new noninvasive test for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis using a simplified histological reference. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:569‐577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Poynard T, Peta V, Munteanu M, et al. The diagnostic performance of a simplified blood test (SteatoTest‐2) for the prediction of liver steatosis. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin C, et al. Diagnosis, staging and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68:723‐750. 10.1002/hep.29913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. European Association for the Study of the Liver(EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) . EASL‐EASD‐EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1388‐1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Poynard T, Munteanu M, Deckmyn O, et al. Applicability and precautions of use of liver injury biomarker FibroTest. A reappraisal at 7 years of age. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boursier J, Vergniol J, Guillet A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and prognostic significance of blood fibrosis tests and liver stiffness measurement by FibroScan in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;65:570‐578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Borlak J, Chatterji B, Londhe KB, et al. Serum acute phase reactants hallmark healthy individuals at risk for acetaminophen‐induced liver injury. Genome Med. 2013;5:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Asleh R, Blum S, Kalet‐Litman S, et al. Correction of HDL dysfunction in individuals with diabetes and the haptoglobin 2‐2 genotype. Diabetes. 2008;57:2794‐2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Reddy ST, Van Lenten BJ, Ansell BJ, Fogelman AM. Mechanisms of disease: proatherogenic HDL–an evolving field. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2:504‐511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials