Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the efficacy of intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy combined with meibomian gland expression (MGX) for refractory meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) in a prospective study conducted at 3 sites in Japan.

Methods:

Patients with refractory obstructive MGD were enrolled and underwent 4 to 8 IPL-MGX treatment sessions at 3-week intervals. Clinical assessment included the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness questionnaire; noninvasive breakup time of the tear film and interferometric fringe pattern as determined by tear interferometry; lid margin abnormalities, fluorescein breakup time of the tear film, corneal and conjunctival fluorescein staining (CFS), and meibum grade as evaluated with a slit-lamp microscope; meibomian gland morphology (meiboscore); and tear production as measured by the Schirmer test without anesthesia.

Results:

Sixty-two eyes of 31 patients (17 women, 14 men; mean age ± SD, 47.6 ± 16.8 years) were enrolled. The Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness score (P < 0.001), noninvasive breakup time (P < 0.001), and interferometric fringe pattern (P < 0.001) were significantly improved after therapy, with 74% of eyes showing a change in the interferometric fringe pattern from 1 characteristic of lipid deficiency to the normal condition. Meibum grade, lid margin abnormality scores, fluorescein breakup time, and CFS were also significantly improved (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001, and P = 0.002, respectively) after treatment, whereas the meiboscore and Schirmer test value remained unchanged.

Conclusions:

IPL-MGX ameliorated symptoms and improved the condition of the tear film in patients with refractory MGD and is therefore a promising treatment option for this disorder.

Key Words: meibomian gland dysfunction, meibomian gland, intense pulsed light

Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) is a chronic abnormality of meibomian glands characterized by terminal duct obstruction or qualitative or quantitative changes in the glandular secretion of meibum.1 Individuals with MGD thus manifest an imbalance in components of the tear film because of a deficiency of the lipid layer. The goal of MGD therapy is to provide long-term and stable amelioration of the symptoms of this condition by improving the quality of meibum or increasing meibum flow, thereby normalizing the balance between the lipid layer and the aqueous and mucin layers of the tear film and enhancing tear film stability, as well as by reducing inflammation. Common therapies include application of a warm compress; practice of lid hygiene; dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids; forced meibum expression2; intraductal probing3; automated thermal pulsation4; and administration of topical steroids, topical and oral antibiotics including topical cyclosporine and azithromycin, preservative-free artificial tears, lipid-containing eye drops, and topical diquafosol.5,6 Despite the variety of treatment options available, however, many patients with MGD are refractory to treatment and thus do not experience complete or long-term relief of symptoms.

Intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy is widely adopted cosmetically and therapeutically for removal of hypertrichosis, benign cavernous hemangiomas or venous malformations, telangiectasia, port wine stains, and other pigmented lesions.7 A systematic review found that IPL is an effective and well-tolerated treatment option for a range of dermatologic conditions, having been shown to result in reduction in the extent of telangiectasia and the severity of facial erythema.8 The efficacy of IPL therapy for patients with dry eye due to MGD was discovered serendipitously during IPL treatment of facial rosacea.9 Subsequent studies found that IPL is effective for improvement of subjective symptoms and objective findings in patients with mild to moderate MGD or dry eye.10–21 Indeed, the combination of IPL and meibomian gland expression (MGX) was found to ameliorate dry eye symptoms and to improve meibomian gland function in patients with refractory dry eye, a cohort that included not only individuals with MGD but also those with graft-versus-host disease or Sjögren syndrome.13 The efficacy of such combination treatment in patients with moderate to advanced MGD was also recently demonstrated in a single-center study.21

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of IPL combined with MGX for patients with refractory MGD, including those with the most severe stage of the condition, in 3 centers in Japan. Refractory MGD was defined as that which had failed to respond to at least 3 types of conventional therapy prescribed in Japan including topical or systemic anti-inflammatory therapy, topical or systemic antibiotic therapy, topical lubricant eyedrops or ointment, automated thermal pulsation treatment, and intraductal probing over the course of at least 1 year. Given that most patients with MGD have applied a warm compress or practiced lid hygiene at home regardless of disease severity, these home-care remedies were not included as failed therapies in this study.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Itoh Clinic, Mizoguchi Eye Clinic, and Ohshima Eye Hospital, and it adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was performed at each of the 3 participating centers from March to September 2017. Informed consent to study participation was obtained from each patient.

Patients

Individuals with refractory MGD attending Itoh Clinic, Mizoguchi Eye Clinic, or Ohshima Eye Hospital were enrolled in the study. Inclusion criteria included the following: 1) an age of at least 20 years; 2) a diagnosis of obstructive MGD based on the Japanese diagnostic criteria for MGD,22 which encompass ocular symptoms, plugged gland orifices, vascularity and irregularity of lid margins, and reduced meibum expression (meibum grade of >1, where grade 0 = clear meibum easily expressed, grade 1 = cloudy meibum expressed with mild pressure, grade 2 = cloudy meibum expressed with more than moderate pressure, and grade 3 = meibum could not be expressed even with strong pressure)23; 3) failure of at least 3 types of conventional MGD therapy to improve symptoms or objective findings for at least 1 year before study treatment; and 4) a Fitzpatrick24 skin type of 1 to 4 based on sun sensitivity and appearance. Exclusion criteria included the presence of active skin lesions, skin cancer, or other specific skin pathology or of active ocular infection or ocular inflammatory disease.

Experimental Design

Each patient underwent a series of 4 to 8 treatment sessions at 3-week intervals depending on the meibum grade23 (4, 6, or 8 sessions for grades 1, 2, and 3, respectively). Each patient was subjected to clinical assessment, as described below both before treatment at each visit and 4 weeks after the final treatment. All patients were asked to continue their current ocular medications. No patient was allowed to initiate therapy with a new topical or systemic agent for dry eye or MGD during the treatment course.

Clinical Assessment

The noninvasive breakup time (NIBUT) and the interferometric fringe pattern of the tear film were determined with a DR-1α tear interferometer (Kowa, Nagoya, Japan), as described previously.25 Lid margin abnormalities (plugging of meibomian gland orifices and vascularity of lid margins),26 breakup time [fluorescein breakup time (FBUT)] of the tear film and the corneal and conjunctival fluorescein staining score (CFS, 0–9)27 based on fluorescein staining, and meibum grade (0–3)23 were evaluated using a slit-lamp microscope. Morphological changes in the meibomian glands were assessed on the basis of the meiboscore (0–6)28, as determined by noninvasive meibography. Tear fluid production was measured by the Schirmer test, as performed without anesthesia.29 Symptoms were assessed with the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED) validated questionnaire (0–28).30,31

IPL-MGX Procedure

Before the first treatment, each patient underwent Fitzpatrick24 skin typing, and the IPL machine (M22; Lumenis, Yokneam, Israel) was adjusted to the appropriate setting (range, 11–14 J/cm2). At each treatment session, both eyes of the patient were closed and sealed with IPL-Aid disposable eye shields (Honeywell Safety Products, Smithfield, RI). After generous application of ultrasonic gel to the targeted skin area, each patient received ∼13 pulses of light (with slightly overlapping applications) from the right preauricular area, across the cheeks and nose, to the left preauricular area, reaching up to the inferior boundary of the eye shields. This procedure was then repeated in a second pass. Immediately after IPL treatment, MGX was performed on both upper and lower eyelids of each eye with an Arita Meibomian Gland Compressor (Katena, Denville, NJ). Pain was minimized during MGX by application of 0.4% oxybuprocaine hydrochloride to each eye.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD as indicated. Parameters were compared between before and after treatment with the paired Student t test. After testing for homogeneity of variance, we applied the independent t test to compare numerical variables and Fisher exact test to compare categorical variables between patients whose eyes showed a change in the SPEED score from baseline (ΔSPEED) of <5 or ≥5. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

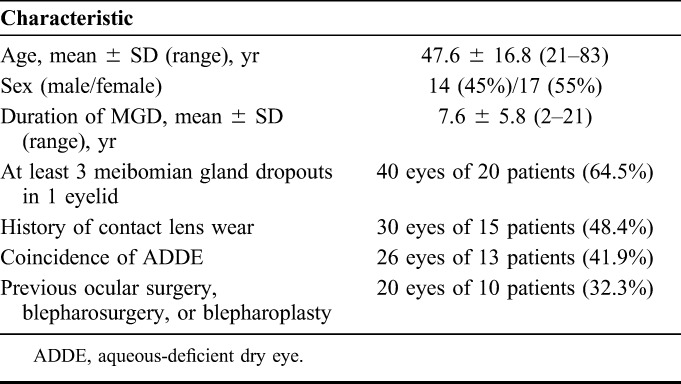

The characteristics of the study patients are presented in Table 1. Sixty-two eyes of 31 patients with refractory obstructive MGD, including 17 women and 14 men, were enrolled in the study. The mean age ± SD was 47.6 ± 16.8 years (range of 21–83 years). The mean duration of MGD ± SD was 7.6 ± 5.8 years (range of 2–21 years). Twenty-six eyes of 13 patients (41.9% of eyes) manifested aqueous-deficient dry eye on the basis of a Schirmer test value of <5 mm. More than half (64.5%) of all eyes had at least 3 dropouts of meibomian glands in 1 eyelid as detected by noninvasive meibography. The average number of IPL-MGX treatments received per patient was 6 (range of 4–8). The frequency of other MGD therapies previously administered is shown in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of 31 Study Patients (62 Eyes)

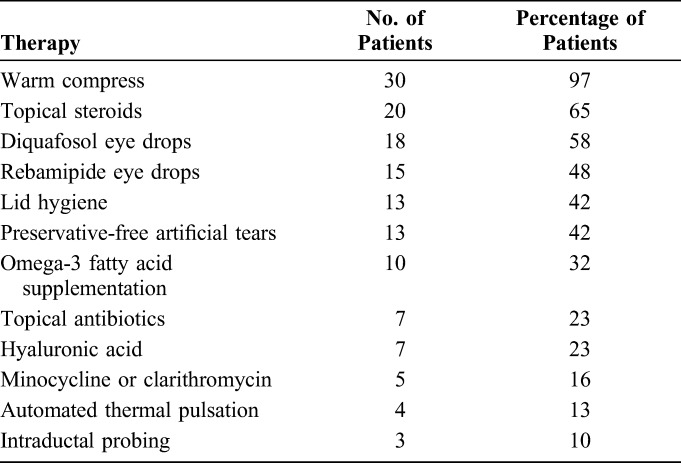

TABLE 2.

Previous Therapies Adopted by 31 Study Patients Without Symptom Improvement

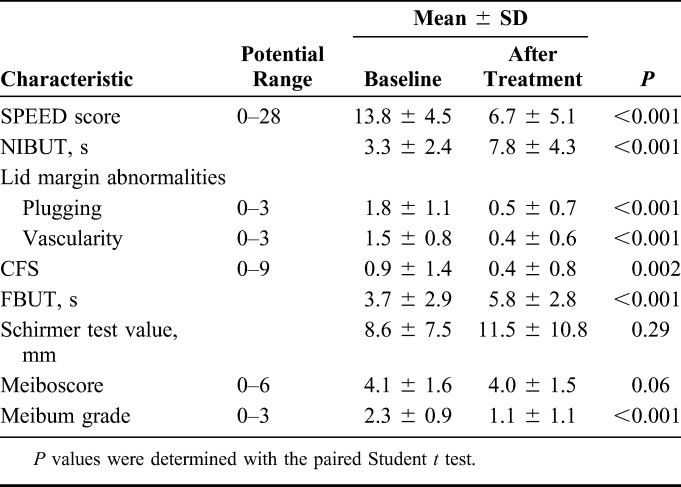

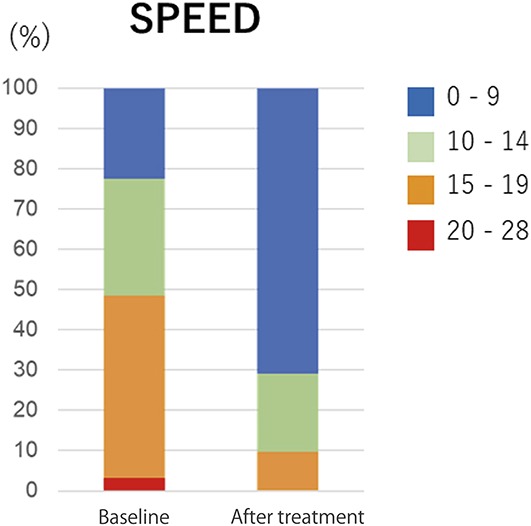

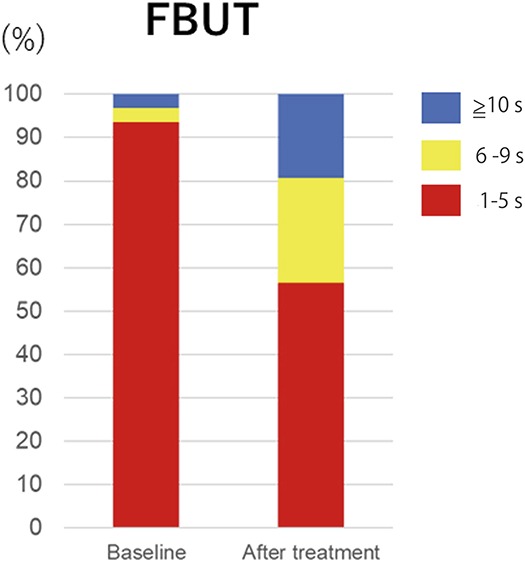

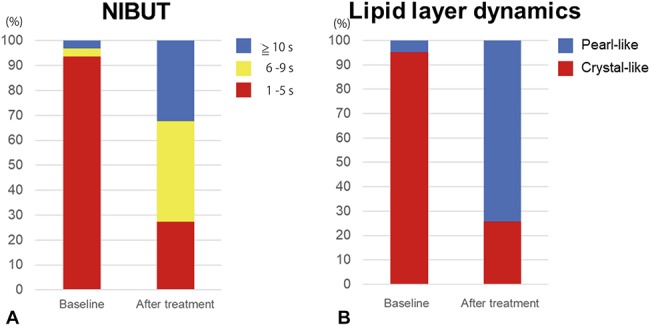

The SPEED score was significantly reduced at 4 weeks after the final IPL-MGX treatment session compared with baseline (P < 0.001), with 81% of the treated eyes showing amelioration of ocular symptoms (Table 3, Fig. 1). The NIBUT and FBUT were significantly prolonged (P < 0.001 for both) at 4 weeks after the final treatment (Table 3), with 70% of treated eyes showing an improvement in the FBUT (Fig. 2) and 84% an improvement in the NIBUT (Fig. 3A). Tear interferometric fringe grading25 was also significantly improved (P < 0.001) at 4 weeks after the final treatment (Fig. 3B), with 74% of treated eyes showing a change in the interferometric fringe pattern from 1 typical of lipid deficiency (crystal-like) to the normal condition (pearl-like). Furthermore, meibum grade, lid margin abnormality scores, and CFS were significantly decreased (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, and P = 0.002, respectively) at 4 weeks after the final treatment (Table 3). By contrast, the meiboscore and Schirmer test value were not significantly improved after treatment (P = 0.06 and P = 0.29, respectively) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of Ocular Assessment Between Before Treatment (Baseline) and 4 Weeks After the Final of a Series of IPL-MGX Treatment Sessions

FIGURE 1.

Change in the SPEED questionnaire score between baseline and 4 weeks after the final IPL-MGX treatment session.

FIGURE 2.

Change in the FBUT between baseline and 4 weeks after the final IPL-MGX treatment session.

FIGURE 3.

Changes in the NIBUT (A) and dynamics of the lipid layer of the tear film, as revealed by a tear interferometric fringe pattern (B) between baseline and 4 weeks after the final IPL-MGX treatment session.

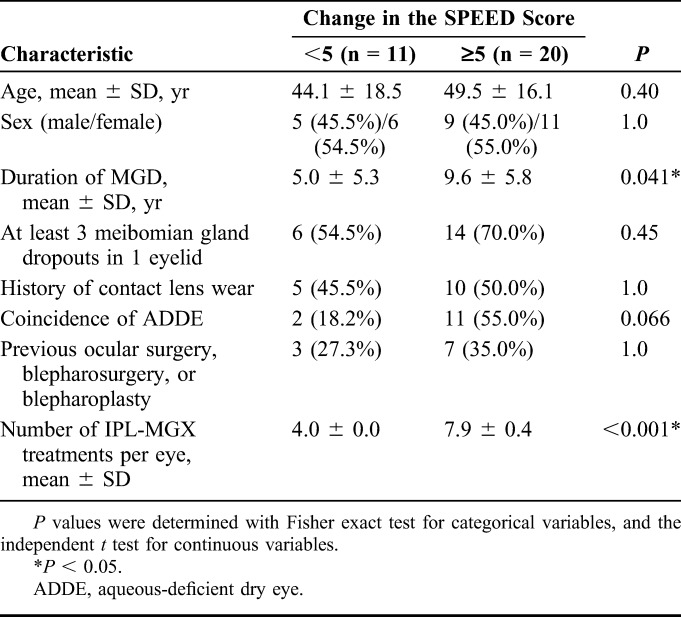

The characteristics of patients who showed a change in the SPEED score for each eye from baseline to 4 weeks after the final treatment (ΔSPEED) of <5 or ≥5 are presented in Table 4. Age did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (P = 0.40). The duration of MGD was significantly longer for the patients with a ΔSPEED of ≥5 than for those with a ΔSPEED of <5 (P = 0.041). Eyes with a ΔSPEED of ≥5 underwent significantly more IPL-MGX treatment sessions than did those with a ΔSPEED of <5 (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in sex distribution or the frequencies of at least 3 meibomian gland dropouts in 1 eyelid, history of contact lens wear, coincidence of aqueous-deficient dry eye, or previous ocular surgery between the 2 groups of patients (P = 1.0, 0.45, 1.0, 0.066, and 1.0, respectively).

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of Patients Who Showed a Change in the SPEED Score of <5 or ≥5 Between Before Treatment (Baseline) and 4 Weeks After the Final of a Series of IPL-MGX Treatment Sessions

DISCUSSION

This is the first prospective and multicenter study to show improvement in the subjective symptoms and objective signs of refractory severe MGD after a series of IPL treatments combined with MGX. Tear film stability, lipid layer dynamics, and meibomian gland function all responded positively to treatment, resulting in improvement in the condition of the tear film in the study patients. This study enrolled patients with refractory severe MGD at 3 centers and did not exclude those with a history of contact lens wear, ocular surgery, or any type of MGD management.

We found that IPL-MGX therapy was effective for management of refractory MGD, being associated with improvement in both lipid layer dynamics (tear interferometric fringe pattern) and NIBUT as determined with the DR-1α tear interferometer. IPL was also shown previously to improve the lipid layer grade as determined with the Tearscope Plus interferometer (Keeler, Windsor, United Kingdom) in patients with MGD.10 This latter study enrolled patients with mild to moderate MGD but not those with refractory MGD, with 82% of the treated eyes showing improvement in the lipid layer grade.10 In this study, after a course of 4 to 8 IPL-MGX treatments, 74% of eyes with refractory MGD showed a change in the tear interferometric fringe pattern from 1 characteristic of lipid deficiency to the normal condition, indicating that the balance between the lipid and aqueous layers of the tear film had improved. The NIBUT is characteristically reduced in patients with MGD.32 The previous study of the lipid layer grade also demonstrated a significant improvement in the NIBUT from 5.28 to 14.11 seconds after treatment of the patients with MGD with IPL.10 In this study, the NIBUT was increased from 3.3 to 7.8 seconds, representing a meaningful clinical improvement, with our previous study having shown that the cutoff value of the NIBUT for dry eye disease as measured by DR-1α is <5 seconds.25

Improvement of meibum quality and expressibility is a key factor in treatment of MGD. We found that meibum quality and expressibility were significantly better after IPL-MGX treatment in this study. Similar results were obtained in previous studies.9,12–15,17,20 IPL application increases skin temperature.10 Whereas the phase-transition temperature of meibum is 28°C in controls, it is >32°C in patients with MGD.33 Although eyelid warming at home has been found to be transiently effective for treatment of MGD,2 the temperature of the eyelid skin was found to increase to 34°C during the application of a warming device but then to decrease rapidly over 10 minutes after device removal.34 Such eyelid warming at home is thus not sufficient to support long-term melting of meibum.34 However, IPL has been found to increase the temperature of small vessels (diameter of < 60 μm) in the targeted skin area to between 45 degrees and 70°C,35 which is likely sufficient to increase the temperature of eyelid skin and the tarsal conjunctiva adjacent to the meibomian glands and thereby to melt meibum.16

Two types of lid margin abnormality—plugging of meibomian gland orifices and vascularity of the lid margin—were evaluated in this study and were found to be significantly improved after IPL-MGX treatment, consistent with the results of previous studies.9,14 IPL therapy is believed to be effective for MGD in part through its heating of the eyelid and consequent melting of meibum.16 Plugging of meibomian gland orifices would therefore be expected to be ameliorated by such treatment. In addition, hemoglobin absorbs light at a wavelength of 580 nm,36 with such absorption during IPL therapy resulting in coagulation of blood in abnormal vessels of telangiectasia and eventually in closure of the vessels and reduced vascularization.9 Such attenuation of abnormal vascularity in patients with MGD seems to reduce both secretion of inflammatory mediators and bacterial growth.9,21

Self-reported ocular symptoms covered by the SPEED questionnaire were significantly ameliorated after IPL-MGX treatment in this study, similar to the results of previous studies.10,13,15,17,18 Twenty-five (81%) and 20 (65%) of the 31 patients in this study thus showed a decrease in the SPPED score of at least 3 or 5 points, respectively. The CFS was also significantly reduced after the treatment sessions, again consistent with previous data.10,14,15,17,20 The patients enrolled in this study had MGD for 7.6 ± 5.8 years, and conventional therapies had not been effective. Indeed, >60% of enrolled eyes showed at least 3 meibomian gland dropouts in 1 eyelid, indicative of the disease severity. Such severe disease was too difficult to manage even with a combination of several conventional therapies. However, a series of IPL-MGX therapy sessions were able to improve subjective symptoms and objective findings including meibum quality and quantity, lid margin abnormalities, and stability and homeostasis of the tear film.

The potential mechanisms for ameliorating subjective symptoms and objective findings of MGD are considered, as mentioned above, to promote melting of meibum,9,16 to attenuate local release of inflammatory factors from the abnormal vessels,18,37,38 and to reduce bacterial load of the eyelid margin.39

There are several limitations to our study. First, the study design was single arm and was based on both eyes of a small number of patients. Further studies with a larger number of patients and a control group are necessary. Second, the duration of follow-up was limited to 4 weeks after the final treatment. Longer follow-up periods will be necessary to assess the long-term effectiveness and safety of IPL treatment. Third, all the patients at each site continued their current medications during the study. A more controlled experimental design will be preferable for future studies. Fourth, IPL treatment is not covered by national insurance in Japan. Although the enrolled patients did not pay for IPL treatment in this study, this situation might introduce inherent bias.

In conclusion, our results suggest that IPL-MGX therapy is effective for patients with refractory MGD whose severe disease is difficult to manage with other conventional therapies. IPL-MGX thus has the potential to help many patients with MGD and is a promising modality for refractory MGD in particular.

Footnotes

R. Arita holds patents on the noncontact meibography technique described in this article (Japanese patent registration no. 5281846; US patent publication no. 2011-0273550A1; and European patent publication no. 2189108A1), is a consultant for Kowa Company (Aichi, Japan) and Lumenis Japan (Tokyo, Japan), and has received financial support from TearScience (Morrisville, NC). The remaining authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nelson JD, Shimazaki J, Benitez-del-Castillo JM, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the definition and classification subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1930–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geerling G, Tauber J, Baudouin C, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on management and treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2050–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maskin SL. Intraductal meibomian gland probing relieves symptoms of obstructive meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2010;29:1145–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greiner JV. A single LipiFlow(R) Thermal Pulsation System treatment improves meibomian gland function and reduces dry eye symptoms for 9 months. Curr Eye Res. 2012;37:272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arita R, Suehiro J, Haraguchi T, et al. Topical diquafosol for patients with obstructive meibomian gland dysfunction. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97:725–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukuoka S, Arita R. Increase in tear film lipid layer thickness after instillation of 3% diquafosol ophthalmic solution in healthy human eyes. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:730–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raulin C, Greve B, Grema H. IPL technology: a review. Lasers Surg Med. 2003;32:78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wat H, Wu DC, Rao J, et al. Application of intense pulsed light in the treatment of dermatologic disease: a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:359–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toyos R, McGill W, Briscoe D. Intense pulsed light treatment for dry eye disease due to meibomian gland dysfunction: a 3-year retrospective study. Photomed Laser Surg. 2015;33:41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craig JP, Chen YH, Turnbull PR. Prospective trial of intense pulsed light for the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:1965–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vora GK, Gupta PK. Intense pulsed light therapy for the treatment of evaporative dry eye disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26:314–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta PK, Vora GK, Matossian C, et al. Outcomes of intense pulsed light therapy for treatment of evaporative dry eye disease. Can J Ophthalmol. 2016;51:249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vegunta S, Patel D, Shen JF. Combination therapy of intense pulsed light therapy and meibomian gland expression (IPL/MGX) can improve dry eye symptoms and meibomian gland function in patients with refractory dry eye: a retrospective analysis. Cornea. 2016;35:318–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang X, Lv H, Song H, et al. Evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of intense pulsed light in the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. J Ophthalmol. 2016;2016:1910694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dell SJ. Intense pulsed light for evaporative dry eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:1167–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dell SJ, Gaster RN, Barbarino SC, et al. Prospective evaluation of intense pulsed light and meibomian gland expression efficacy on relieving signs and symptoms of dry eye disease due to meibomian gland dysfunction. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:817–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rong B, Tu P, Tang Y, et al. Evaluation of short-term effect of intense pulsed light combined with meibomian gland expression in the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2017;53:675–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu R, Rong B, Tu P, et al. Analysis of cytokine levels in tears and clinical correlations after intense pulsed light treating meibomian gland dysfunction. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;183:81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guilloto CS, Garcia MJL, Colmenero RE. Effect of pulsed laser light in patients with dry eye syndrome. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2017;92:509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin Y, Liu N, Gong L, et al. Changes in the meibomian gland after exposure to intense pulsed light in meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) patients. Curr Eye Res. 2018;43:308–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albietz JM, Schmid KL. Intense pulsed light treatment and meibomian gland expression for moderate to advanced meibomian gland dysfunction. Clin Exp Optom. 2018;101:23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amano S, Arita R, Kinoshita S, et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria for meibomian gland dysfunction. Atarashii Ganka (J Eye). 2010;27:627–631. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimazaki J, Sakata M, Tsubota K. Ocular surface changes and discomfort in patients with meibomian gland dysfunction. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1266–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arita R, Morishige N, Fujii T, et al. Tear interferometric patterns reflect clinical tear dynamics in dry eye patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:3928–3934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arita R, Minoura I, Morishige N, et al. Development of definitive and reliable grading scales for meibomian gland dysfunction. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;169:125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Bijsterveld OP. Diagnostic tests in the Sicca syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1969;82:10–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arita R, Itoh K, Inoue K, et al. Noncontact infrared meibography to document age-related changes of the meibomian glands in a normal population. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:911–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shirmer O. Studiun zur physiologie und pathologie der tranenabsonderung und tranenabfuhr. von Graefes Arch Ophthalmol. 1903;56:197–291. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korb DR, Blackie CA, McNally EN. Evidence suggesting that the keratinized portions of the upper and lower lid margins do not make complete contact during deliberate blinking. Cornea. 2013;32:491–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ngo W, Situ P, Keir N, et al. Psychometric properties and validation of the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness questionnaire. Cornea. 2013;32:1204–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pflugfelder SC, Tseng SC, Sanabria O, et al. Evaluation of subjective assessments and objective diagnostic tests for diagnosing tear-film disorders known to cause ocular irritation. Cornea. 1998;17:38–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borchman D, Foulks GN, Yappert MC, et al. Human meibum lipid conformation and thermodynamic changes with meibomian-gland dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3805–3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arita R, Morishige N, Shirakawa R, et al. Effects of eyelid warming devices on tear film parameters in normal subjects and patients with meibomian gland dysfunction. Ocul Surf. 2015;13:321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vural E, Winfield HL, Shingleton AW, et al. The effects of laser irradiation on Trichophyton rubrum growth. Lasers Med Sci. 2008;23:349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fabi SG, Goldman MP. The safety and efficacy of combining poly-L-lactic acid with intense pulsed light in facial rejuvenation: a retrospective study of 90 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1208–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schroeter CA, Haaf-von BS, Neumann HA. Effective treatment of rosacea using intense pulsed light systems. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1285–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Godoy CH, Silva PF, de Araujo DS, et al. Evaluation of effect of low-level laser therapy on adolescents with temporomandibular disorder: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farrell HP, Garvey M, Cormican M, et al. Investigation of critical inter-related factors affecting the efficacy of pulsed light for inactivating clinically relevant bacterial pathogens. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;108:1494–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]