Abstract

This study reports a spatiotemporal characterization of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde in the summer and winter of 2017 in the urban area of Shiraz, Iran. Sampling was fulfilled according to EPA Method TO-11 A. The inverse distance weighting (IDW) procedure was used for spatial mapping. Monte Carlo simulations were conducted to evaluate carcinogenic and non-cancer risk owing to formaldehyde and acetaldehyde exposure in 11 age groups. The average concentrations of formal-dehyde/acetaldehyde in the summer and winter were 15.07/8.40 μg m−3 and 8.57/3.52 μg m−3, respectively. The formaldehyde to acetaldehyde ratios in the summer and winter were 1.80 and 2.43, respectively. The main sources of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde were photochemical generation, vehicular traffic, and biogenic emissions (e.g., coniferous and deciduous trees). The mean inhalation lifetime cancer risk (LTCR) values according to the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) for formaldehyde and acetaldehyde in summer and winter ranged between 7.55 × 10−6 and 9.25 × 10−5, which exceed the recommended value by US EPA. The average LTCR according to the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) for formaldehyde and acetaldehyde in summer and winter were between 4.82 × 10−6 and 2.58 × 10−4, which exceeds recommended values for five different age groups (Birth to <1, 1 to <2, 2 to < 3, 3 to <6, and 6 to <11 years). Hazard quotients (HQs) of formaldehyde ranged between 0.04 and 4.18 for both seasons, while the HQs for acetaldehyde were limited between 0.42 and 0.97.

Keywords: Risk assessment, Formaldehyde, Acetaldehyde, LTCR, Hazard quotient

1. Introduction

One of the main anthropogenic sources of air pollution in urban atmospheres is vehicular exhaust (Lü et al., 2010, 2016; Viskari et al., 2000), with a chief component being volatile organic compounds (VOCs) (Ho et al., 2016; Tunsaringkarn et al., 2012a). The main class of VOCs is aldehyde species, with the primary components being formaldehyde (HCHO, hereinafter FA) and acetaldehyde (CH3CHO, hereinafter AA). These two species have been targeted in numerous toxicological studies owing to their deleterious health effects (Health and Services, 1999; Neghab et al., 2017; Salthammer et al., 2010; Til et al., 1988; Tunsaringkarn et al., 2012b, 2012c). Their ubiquity and importance in ambient air have been documented in many past studies (Lü et al., 2016; Neghab et al., 2017; Sarkar et al., 2017). Owing to rapid global urbanization and population growth, characterizing the concentrations and health effects of these aldehyde species is important as vehicular emissions are a major pollutant source in urban centers (Bauri et al., 2016; Crosbie et al., 2014; Hazrati et al., 2016b; Mannucci and Franchini, 2017; Masih et al., 2016; Morknoy et al., 2011; Rad et al., 2014; Sarkar et al., 2017; Saxena and Ghosh, 2012; Tunsaringkarn et al., 2014).

Formaldehyde and AA can be emitted directly from the source or by secondary production via photochemical reactions (Chi et al., 2007; de Carvalho et al., 2008; de Mendonça Ochs et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2016; Morknoy et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2005). Emissions sources include vegetation and anthropogenic sources such as gas stations, motor vehicle emissions, and bus terminals (Anderson et al., 1996; de Mendonça Ochs et al., 2015; Duan et al., 2012; Lü et al., 2010; Morknoy et al., 2011; Nogueira et al., 2014; Nogueira et al., 2017; Viskari et al., 2000). Concentrations of these species have been reported to depend on meteorological conditions such as temperature, humidity, and wind speed (Lü et al., 2016; Missia et al., 2010; Morknoy et al., 2011). According to United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA), FA and AA are classified as group B1 (human carcinogen) and group B2 (probable human carcinogen) species, respectively (de Mendonça Ochs et al., 2015; Rodrigues et al., 2012; USEPA, 1999a, 1999b). In addition, FA leads to eye irritation, a dry or sore throat, mucous membranes, a tingling sensation of the nose, menstrual disorders, pregnancy problems, and bronchial asthma-like symptoms (Barkhordari et al., 2017; Ho et al., 2016; Kanjanasiranont et al., 2017; Tunsaringkarn et al., 2012c; U.S.EPA, 2000). Furthermore, effects of AA on the human health include headache, vomiting, eye irritation, nausea, mucous membranes, and negative impacts on skin, throat, and the respiratory tract (Kanjanasiranont et al., 2017; Tunsaringkarn et al., 2012c; U.S.EPA, 2000). The ratio of these two species is potentially a useful indicator of emissions sources; for instance, Viskari et al. (2000) and Lü et al. (2010) showed for Finland and China, respectively, that the FA/AA ratio in winter was about 0.69–2.60, while in summer, the FA/AA ratio was about 0.11–2.60 (Lü et al., 2010; Viskari et al., 2000). On the other hand, Anderson et al. (1996), Viskari et al. (2000) and Nogueira et al. (2017) reported FA/AA ratios less than two, indicating that secondary sources contributed significantly to FA and AA concentrations in summer (Anderson et al., 1996; Nogueira et al., 2017; Viskari et al., 2000). Differences in the FA:AA ratio between these studies can be used for identifying sources of FA and AA such as vehicular emissions, fuel containing of ethanol, and biogenic and secondary sources (photochemical generation) (Lü et al., 2016; Nogueira et al., 2014, 2017; Rao et al., 2016; Viskari et al., 2000).

The aim of this study is to report for the first time FA and AA characteristics near main squares in Shiraz city, with discussion of effects on public health. More specifically, the subsequent discussion presents concentrations, spatial and temporal characteristics, production pathways, and a health risk assessment for 11 different age groups. The results of this work have broad implications for other populated areas with vehicular emissions.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study area

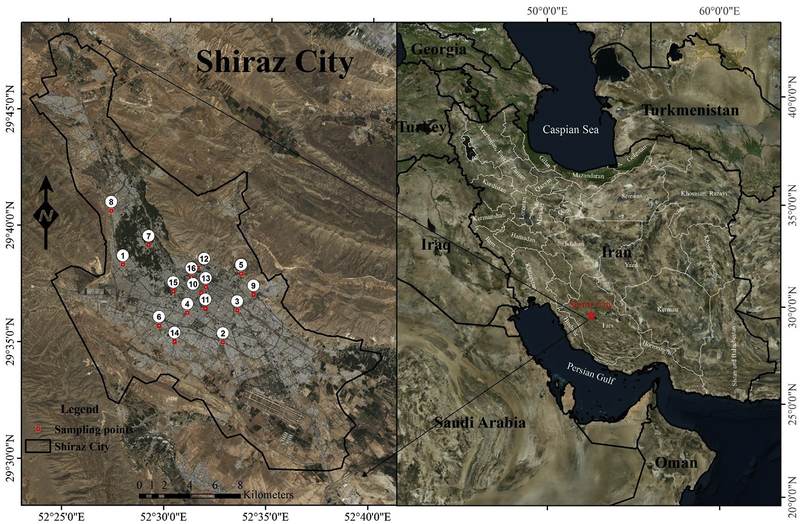

Shiraz is located in the southwestern part of Iran (29°36′N, 52°32′ E) and the capital of the Fars province (Fig. 1). It has a population of ~1.8 million according to the recent census report in 2017, that describes it as the fifth most populated city in Iran (Dehghani et al., 2018; Statistical Centre of Iran (SCI), 2016). Shiraz covers 240 km2 and includes eleven urban terrains with mean population density of nearly 6890 residents per km2 (Statistical Centre of Iran (SCI), 2016). The city is characterized as having a semi-arid climate. This city was categorized as one of the main polluted cities in Iran (Arfaeinia et al., 2017; Dehghani et al., 2018; Fathabadi and Hajizadeh, 2016). The air sampling locations, shown in Fig. 1, were selected based on numerous factors such as vicinity to major populated centers, high levels of traffic congestion, and convenience for sampling.

Fig. 1.

Map of the study region and sampling points (1- Moalem Square; 2 - Rezvan Square (bridge); 3 - Valiasr Square; 4 - Basij Square; 5 - Quran Square; 6 - Pasargad Square; 7 -Ghasrodasht Square; 8 - Ehsan Square; 9 - Haft Tanan Square; 10–15 Khordad Square (crossroad); 11 - Darvazeh Kazeroon Square; 12 - Eram Square; 13 - Imam Hossein Square; 14 -Edalat Square (boulevard); 15 - Sangi Square; 16 - Namazi Square).

2.2. Data collection and analysis

Sampling of FA and AA was performed based on EPA Method TO-11A (USEPA, 1996, 1999a; 1999b). Measurements were conducted over 4 h in the evening (16:00–20:00 local time) in the summer (22 June 2017 to 22 July 2017) and winter (22 December 2017 to 20 January 2018) via active sampling (SKC, Model 222-ml/COUNT) using sorbent sample tubes (Cat. Nos. 226-119-7, SKC, Inc., U.S.A, including high grade silica gel coated with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (2,4-DNPH), 7 mm × 110 mm size, two parts, 150 mg (front)/300 mg (backup) sorbent) at a flow rate of 1.00 L min−1 (sample volume ~ 240.00 L). In addition, potassium iodide was used as an ozone scrubber in the sorbent tubes (Corrêa et al., 2010; Fung and Grosjean, 1981; Fung and Wright, 1990; Possanzini et al., 2002). Samples were collected every sixth day at all 16 monitoring stations, amounting to a total of 160 samples (80 for summer and 80 for winter). Sampling was conducted above street level (at level of 1.5 m). After sampling, sorbent tubes were tagged, protected from light (using aluminum foil), stored at 4°C (using portable plastic cooler box), and transferred to a laboratory. Samples were examined within 48 h after sampling. Temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and pressure were also simultaneously recorded. Temperature (°C), pressure (mb) and relative humidity (%) were determined by a portable instrument (Preservation Equipment Ltd, UK). Additionally, wind speed (m s−1) was measured using a portable anemometer (Campbell Scientific, Inc., USA).

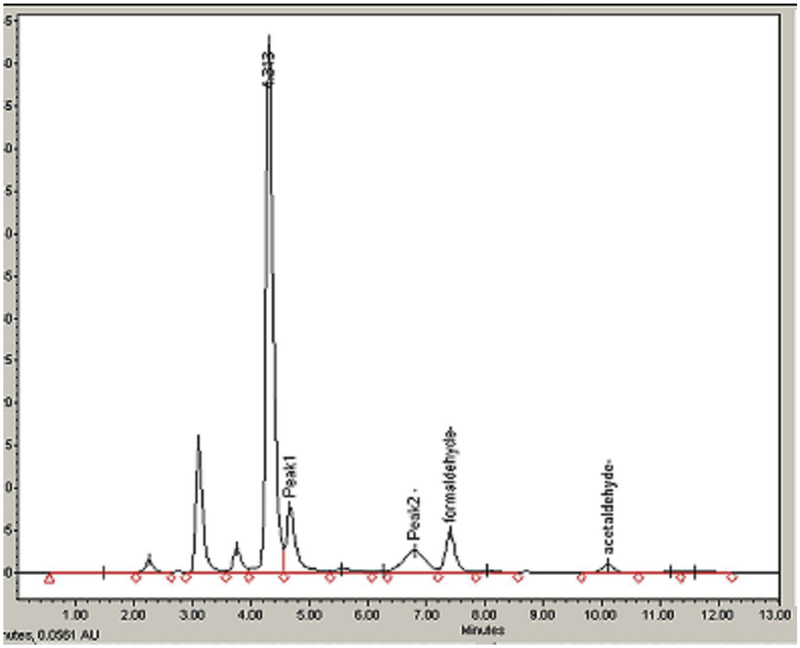

Each part of the sorbent was first poured into separate glass amber vials. Secondly, 3 ml of acetonitrile (HPLC-purity, J.T. Baker, United Kingdom) were added to each amber vial and then capped. Next, each amber vial was shaken for 20 min. Finally, the extracted sample was analyzed using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (HPLC,YL9100, Model Waters 1525, C18 column (reverse phase)) with UV detection at 365 nm (ISO, 2001; Svendsen et al., 2002; Tunsaringkarn et al., 2012c; Vainiotalo and Matveinen, 1993). The 2,4-Dinitrophenylhydrazine coatings were extracted with HPLC-grade acetonitrile. Ten μL of the aliquot was injected into the HPLC instrument. The mobile phase contained 45/55 (v/v) water/acetonitrile blend with a flow rate of 1 mL min−1 for over 30 min in an isocratic run, and the temperature of the oven was 40°C. A typical chromatogram of HPLC for a real sample is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

A typical chromatogram of HPLC for a real sample.

2.3. QA/QC

The calibration curve applied for quantification was comprised of six points ranging from 0.001 to 40 μg m−3, for each target components with coefficients of determination (R2) being 0.997 for FA and 0.989 for AA. The limits of detection (LOD) were computed as three times the standard deviation (SD) of the blank values. Limits of quantitation (LOQ) were quantified as 10 times the SD of the blank values. The LOD and LOQ were 0.001 and 0.0033 μg m−3 for FA, respectively, and 0.001 and 0.0033 μg m−3 for AA. The recovery values of FA and AA ranged from 97.3 ± 2.1% to 99.8 ± 2.8% with relative standard deviations (RDS) less than 3.7% for both species. Furthermore, blank sampling (16 samples) was regularly carried out and the concentrations of FA and AA were always below 0.001 μg m−3.

2.4. Statistical analysis

SPSS analytical software (Version 22.00) was applied for statistical analysis. Relationship between pollutants were compared using Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient for both winter and summer. The FA:AA ratio was computed for summer and winter in order to assess emission of different sources. Additionally, the student’s t-test was applied to quantify the level of statistical significance of correlation coefficients.

2.5. Spatial distributions

ArcGIS software (Version 10.3) was applied for spatial analysis. The inverse distance weighted (IDW) method was used to create raster layers for the mean concentrations of FA and AA to help visually present their distributions around Shiraz. Afterward, the raster calculation function was used to overlay each layer and create mean maps of FA and AA. The IDW technique is defined as follows (Dehghani et al., 2018):

| (1) |

where Di, λi, and α are the distance between station i and an unknown point, the weight of the i sample station, and the weighting power, respectively. Higher weights were assigned to values closer to the interpolated point, following the guidance of past work (Dehghani et al., 2018; Shepard, 1968). The number of stations applied in the interpolation is represented by n, which is 16 in this study. Past works have used the IDW method for spatial topography of pollutants such as BTEX compounds in Shiraz, Iran (Dehghani et al., 2018), SO2 and NO2 in Mumbai (India) (Kumar et al., 2016), particulate matter in California and Pennsylvania (USA) (Li et al., 2016), and Beijing (China) (Li et al., 2014), and atmospheric wet-deposition in Oregon, Nevada, and Washington (USA) (Latysh and Wetherbee, 2012).

2.6. Health risk assessment (HRA)

For assessing the risk to the human health upon exposure to FA and AA, their inhalation lifetime cancer risk (LTCR) and non-carcinogenic risk were estimated. The LTCR was calculated as follows:

| (2) |

Furthermore, the CDI was calculated using Eq. (3):

| (3) |

where C is ambient concentration (μg m−3), CF is a conversion factor (mg/μg), IR is human inhalation rate (m3 day−1), ED is exposure duration (yr), EF is exposure frequency (days year−1), BW is body weight (kg), and AT is average lifetime (yr). The probabilistic calculations were carried out using Monte Carlo simulations (Oracle Crystal Ball (Version 11.1.2.3.000)).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), LTCR values considered as “an acceptable limit for humans” are proposed to range from 1 × 10−5 to 1 × 10−6, but LTCR values less than 1 × 10−6 are recommended by U. S. EPA (Gong et al., 2017; Hazrati et al., 2015, 2016a; Ho et al., 2016; Rovira et al., 2016; Tunsaringkarn et al., 2012a).

Risk assessment for the non-carcinogenic risk of FA and AA was calculated using the parameter called hazard quotient

| (4) |

| (5) |

If HQ exceeds one, the potential risk can be serious. Values ≤ 1 indicate an acceptable hazard level since the dose level is lower than the reference concentration (RfC).

Table 1 shows chosen parameter values applied for risk assessment and sensitivity analysis, including values to compute CDI, HQ, and LTCR. For calculating the chronic daily intake, the average of FA and AA concentrations was utilized.

Table 1.

Risk parameters used for Monte Carlo simulations for calculating HQ, LTCR, and sensitivity analysis for formaldehyde and acetaldehyde.

| Age groups (year) | Reference | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth to <1 | 1 to <2 | 2 to <3 | 3 to <6 | 6 to <11 | 11 to <16 | 16 to <21 | 21 to <61 | 61 to <71 | 71 to <81 | 81 and older | ||

| Inhalation rate (m3 day−1) | 5.4 | 5.4 | 8.9 | 10.1 | 12 | 15.2 | 16.3 | 16 | 14.2 | 12.9 | 12.2 | (EPA, 2011) |

| Body weight (kg) | 9.2 | 11.4 | 13.8 | 18.6 | 31.8 | 56.8 | 71.6 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | (EPA, 2011) |

| Exposure duration (year) | 0.5–1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 | (EPA, 2011) |

| Exposure frequency (day year−1) | 365 | 365 | 365 | 365 | 365 | 365 | 365 | 365 | 365 | 365 | 365 | (EPA, 2011) |

| Averaging time (day) | 365 | 365 | 365 | 1095 | 1825 | 1825 | 1825 | 17885 | 17885 | 17885 | 17885 | (EPA, 2011) |

| Cancer slope factor (CSF) (mg kg−1 day−1)−1 | 2.10 × 10−2 for formaldehyde | (OEHHA, 2009; OEHHA, 2014; Sousa et al., 2011;USEPA, 1996) | ||||||||||

| 1.00 × 10−2 for acetaldehyde | ||||||||||||

| 4.55 × 10−2 for formaldehyde | ||||||||||||

| 7.70 × 10−3 for acetaldehyde | ||||||||||||

| Inhalation reference concentration (RfC) (mg m−3) | Formaldehyde 9.83 × 10−3 and acetaldehyde 9.00 × 10−3 | (CalEPA, 1997; IARC, 1999; OEHHA, 2014; Sousa et al., 2011; USEPA, 1989; 2004; Wu et al., 2003) | ||||||||||

| Formaldehyde 2.00 × 10−1 | ||||||||||||

| Formaldehyde 3.6 × 10−3 (CAPCOA, California EPA) | ||||||||||||

| Formaldehyde 4.55 × 10−2 | ||||||||||||

| Formaldehyde 9.83 × 10−3 | ||||||||||||

| Acetaldehyde 9.00 × 10−3 | ||||||||||||

| Carcinogenicity | Formaldehyde is group B1 | (IARC, 1999) | ||||||||||

| Acetaldehyde is group B2 | ||||||||||||

| CAS no. | 50000 for formaldehyde and 75070 for acetaldehyde | (IARC, 1999) | ||||||||||

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Meteorological conditions

The means of temperature and relative humidity were 40.69 ± 1.55C° and 14.44 ± 1.06%, respectively, during summer, and 19.00 ± 1.31C° and 34.06 ± 1.19% during winter. Moreover, the wind speed was 2.38 ± 0.40 m s−1 in summer and 4.88 ± 0.50 m s−1 in winter. Pressure was also 850.50 ± 1.30 and 851.04 ± 1.11 mb in summer and winter, respectively.

3.2. Formaldehyde and acetaldehyde concentrations

The average (±SD) FA concentration in the summer and winter were 15.07 ± 9.17 and 8.57 ± 5.91 μg m−3, respectively. In addition, for the same seasons, the average concentrations for AA were 8.40 ± 4.29 and 3.52 ± 1.69 μg m−3, respectively. The highest and lowest concentrations for formaldehyde in summer were 37.63 and 3.86 μg m−3 and in winter were 23.01 and 1.82 μg m−3, respectively. In addition, the highest and lowest concentrations for acetaldehyde in summer were 33.83 and 1.56 μg m−3 and in winter were 14.12 and 0.29 μg m−3, respectively. Hence, the results of this study show that FA was as abundant as AA in two seasons. These results are in line with those from Hong Kong (China) (Lui et al., 2017), Bangkok (Thailand) (Morknoy et al., 2011), New York (USA) (Tanner and Meng, 1984), Rome (Italy) (Possanzini et al., 2002), Georgia (USA) (Grosjean et al., 1993), Kuopio (Finland) (Viskari et al., 2000), Bangkok (Thailand) (Tunsaringkarn et al., 2012b), Guiyang, (Southwest China) (Pang and Lee, 2010), Salvador (Brazil) (Rodrigues et al., 2012), and 2 northern California counties (Alameda and Monterey) (Bradman et al., 2017).

For example, Tanner and Meng. (1984) reported that the values of FA in the winter (3.8 ppbv) and autumn seasons (4.4 ppbv) were lower than summer (16 ppbv) and spring seasons (12 ppbv). Also, that same study also observed that AA levels in the summer (8.4 ppbv) and spring seasons (3.5 ppbv) exceeded those in winter (1.0 ppbv) and autumn seasons (3.2 ppbv) (Tanner and Meng, 1984).

Reasons for FA and AA being highest in concentration in the summer and lowest in concentration in the winter could be linked to more efficient photooxidation to produce them in the summer (i.e., higher incident solar radiation) and more effective removal via wet scavenging in the winter. In this regard, the findings of the present study are consistent with those by Lui et al. (2017) (Hong Kong, China), Rodriguez et al. (2017) (San Diego, USA), Granby et al. (1997) (Central Copenhagen, Denmark), Tanner and Meng, 1984 (Rome, Italy), and De Bruin et al., (2008) (in twelve European cities). Photochemical generation of FA and AA is possible due to oxidative degradation of VOCs such as alkenes enhanced by hydroxyl radicals in summer (Duan et al., 2012; Lui et al., 2017; Morknoy et al., 2011; Possanzini et al., 2002). To reinforce the importance of photo-oxidation in forming FA and AA, it is worth noting Morknoy et al. (2011) observed diminished concentrations of FA and AA from day to night by 8% and 6%, respectively (Morknoy et al., 2011).

The findings of the our study show that the mean concentrations of FA and AA were higher than previous studies, specifically those carried out in suburban, urban, and rural areas of either Japan (Naya and Nakanishi, 2005), Sao Paulo, Brazil (Nogueira et al., 2017), or Prince Edward Island, Canada (Gilbert et al., 2005). This is owing to heavy traffic, oxygenated fuels, and proximity to coniferous and deciduous trees in Shiraz. Past work has also linked emissions from coniferous and deciduous trees and blooming periods to high levels of FA and AA; these are in line with the findings of our study especially sampling locations 16 (Namazi Square), 7 (Ghasrodasht Square) and 9 (Haft Tanan Square) (Kesselmeier et al., 1997; Müller et al., 2002; Viskari et al., 2000). Furthermore, the kind of fuels used in Iran include gas, petrol, gasoline consisting of Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), compressed natural gas (CNG), and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). Hence, consuming of fuels such as CNG and gasoline-MTBE by vehicles in Iran can increase the concentrations of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde. In addition, many works stated that the addition of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) to fuels or biodiesel (5%) to diesel fuel enhanced emissions of FA and AA and consuming of fuels such as CNG; such results are in line with the present study (Alvim et al., 2011; Corrêa et al., 2003; Nogueira et al., 2014, 2017; Possanzini et al., 2002; Viskari et al., 2000).

3.3. Comparison of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde concentrations with recommended guidelines

The guidelines for FA and AA in workplaces and in urban ambient air are presented in Table 2. In addition, standard regulated values for FA and AA concentrations in the urban ambient air have not been established in Iran yet as state and local agencies have no monitoring programs. Furthermore, standards for FA and AA in atmospheric ambient air have not been established by the national and international institutions around the world. To our knowledge, the only guideline recommended for FA in urban ambient air is provided for the Japanese general population: 10 μg m−3 (Naya and Nakanishi, 2005). Hence, the results of this work are compared with that guideline and standards proposed for indoor air such as ACGIH, OSHA, WHO, U.S-ATSDR, China, France and others in Table 2. The results of this work shows that the average concentrations of FA were higher than the USA (annual average and 8 h), China (8 h), U.S-ATSDR (indoor), and Japan (urban ambient air), while the average concentrations of AA were lower than recommended values by HSE, ACGIH, OSHA, and Iran-OEL.

Table 2.

Recommended guidelines for formaldehyde and acetaldehyde concentrations in indoor and outdoor air.

| Formaldehyde | |||||

| Country | Guideline values (μg m−3) | Exposure time | Outdoor or indoor | Additional information | Reference |

| Japan | 10 | – | Outdoor | Histopathological changes | (Naya and Nakanishi, 2005) |

| China | 30 | 8-h | Indoor | – | (Salthammer et al., 2010) |

| Finland | 30 | – | Indoor | Individual indoor climate | (Säteri, 2002) |

| 50 | – | Indoor | Good indoor climate | (Säteri, 2002) | |

| 100 | – | Indoor | Satisfactory indoor climate | (Säteri, 2002) | |

| France | 50 | 2 h | Indoor | – | (Salthammer et al., 2010) |

| France | 10 | LTEL | Indoor | – | (Salthammer et al., 2010) |

| Iran-OEL | 370 “C” | – | Indoor | URT; eye irritation; suspected human carcinogen | (ITCOH, 2012) |

| U.S-ATSDR | 49 | – | Indoor | Acute minimal risk revel and changes in human nasal lavage fuid | (Pazdrak et al., 1993) |

| 37 | – | Indoor | Intermediate minimal risk revel and chronic inhalation toxicity in animals | (Rusch et al., 1983) | |

| 10 | – | Indoor | Chronic minimal risk revel and Histological changes in human nasal mucosa | (Holmström et al., 1989) | |

| Canada | 123 | 1 h | Indoor | Eye irritation; Residential indoor air | (Canada, 2005) |

| 50 | 8-h | Indoor | Respiratory symptoms in children. Residential indoor air | (Canada, 2005) | |

| USA | 923 | 8-h | Indoor | Permissible exposure limits;Occupational standards | (OSHA, 2011) |

| 2460 | 15 min | Indoor | Permissible exposure limits;Occupational standards | (OSHA, 2011) | |

| Singapore | 100 | 8-h | Indoor | – | (Salthammer et al., 2010) |

| USA | 33 | 8-h | Indoor | Iinterim REL | (Guideline, 1991) |

| 3 | Annual average | Indoor | Chronic REL | (OEHHA, 2005) | |

| 20 | 8-h | Indoor | Recommendable exposure limit | (NIOSH, 2004) | |

| 150 | 15 min | Indoor | Recommendable exposure limit | (NIOSH, 2004) | |

| Europe | 100 | 30 min | Indoor | Air Quality Guidelines; Sensoryirritation | (RAIS, 2014) |

| Spain | 370 | STEL | Indoor | Occupational exposure | (Campo Ojeda, 2003) |

| OSHA | 923 | – | Indoor | – | (Eller and Cassinelli, 2003) |

| 2460 | STEL | Indoor | – | (Eller and Cassinelli, 2003) | |

| NIOSH | 20 | – | Indoor | – | (NIOSH, 2003) |

| 123 “C” | – | Indoor | – | (NIOSH, 2003) | |

| ACGIH | 370 “C” | – | Indoor | URT; eye irritation; suspected human carcinogen | (ACGIH, 2014) |

| WHO-ROE | 100 | 30 min | Indoor | Nose and throat irritation in humans after short-term exposure | (WHO, 2000) |

| WHO | 100 | 30 min | Indoor | – | (WHO, 1987) |

| Acetaldehyde | |||||

| HSE | 66637 | 8-h | Indoor | – | (HSE, 2011) |

| 92000 | 15 min (STEL) | Indoor | – | (HSE, 2011) | |

| ACGIH | 45025 “C” | 15 min (STEL) | Indoor | URT; eye irritation | (ACGIH, 2014) |

| Iran-OEL | 45025 “C” | – | Indoor | URT; eye irritation | (ITCOH, 2012) |

| OSHA | 360200 | – | Indoor | – | (NIOSH, 1993) |

| ACGIH | 18010 | STEL | Indoor | – | (NIOSH, 1993) |

| 27015 | – | Indoor | Suspect carcinogen | (NIOSH, 1993) | |

“C” = Ceiling limit; URT = Upper respiratory tract; STEL= Short-term exposure limit; REL = Reference exposure limit; U.S-ATSDR= U.S- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; Iran-OEL= Iranian occupational exposure limit; HSE=Health and Safety Executive; WHO-ROE = World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe; LTE = Long-term exposure Limit.

3.4. The ratio of formaldehyde to acetaldehyde (FA to AA)

Table 3 compares the FA:AA ratio in the current study versus data collected in other regions. The FA:AA ratio in the summer and winter were 1.80 and 2.43, respectively. FA:AA ratios in this study were similar to those in Kuopio, Eastern Finland (2.1–2.6), Beijing, China (2.3), Denver, Colorado (2.2), Algiers and Ouargla, Algeria (2.27), and Whiteface Mountain (WFM) in New York State (2.3) (Anderson et al., 1996; Cecinato et al., 2002; Khwaja and Narang, 2008; Rao et al., 2016; Viskari et al., 2000). In contrast, lower ratios were reported in São Paulo (brazil) (0.90) (Nogueira et al., 2017), North-East Guangzhou (China) (0.73–1.64) (Lü et al., 2010), Bavaria (Germany) (1.18) (Müller et al., 2006), Guangzhou (South China) (0.87) (Yu et al., 2008), and Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) (0.67–1.00) (Corrêa et al., 2003). Differences in the FA:AA ratio between these studies is due to the diversity in sampling location (forested, semi-rural, highway, tunnel and urban), meteorology, addition of MTBE, ethanol or biodiesel to fuels, biogenic landscape, and density of anthropogenic sources.

Table 3.

Comparison of seasonal FA:AA ratio (μg m−3/μg m−3) in the current study versus others.

| Mean seasonal FA:AA ratios (μg m−3/μg m−3) | Season | Sources of generation FA and AA | City | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.80 | Summer | Photochemical generation, higher ambient temperature and biogenic sources | Shiraz,Iran | This study |

| 2.43 | Winter | Traffic emission (primary sources), biogenic sources (coniferous and deciduous trees) | Shiraz,Iran | This study |

| 1.3–1.7 | Summer | Intense photochemical generation, Fuel containing of ethanol (hydrous ethanol or gasohol) and the high levels of solar radiation | Sao paulo, brazil | (Nogueira et al., 2017) |

| 0.90 | Winter | The low levels of solar radiation | Sao paulo, brazil | (Nogueira et al., 2017) |

| 2.4–2.6 | Summer | Secondary sources (photochemical generation) | Kuopio, Eastern Finland | (Viskari et al., 2000) |

| 2.1–2.6 | Winter | Traffic emission, biogenic sources or vegetation (both coniferous and deciduous trees), low sunlight irradiation, primary sources (direct vehicular emissions) and secondary sources (inversion) | Kuopio, Eastern Finland | (Viskari et al., 2000) |

| 1.2–2.3 | Spring | Traffic emission and biogenic sources or vegetation (both coniferous and deciduous trees) | Kuopio, Eastern Finland | (Viskari et al., 2000) |

| 2.2 | Summer | High atmospheric photooxidation of alkenes and alkanes | Denver, Colorado | (Anderson et al., 1996) |

| 1.5 | Winter | Low atmospheric photooxidation of alkenes and alkanes | Denver, Colorado | (Anderson et al., 1996) |

| 1.9 | Spring | Mean atmospheric photooxidation of alkenes and alkanes | Denver, Colorado | (Anderson et al., 1996) |

| 2.69 | Summer | Photochemical formation of carbonyls (in haze days) | Beijing, China | (Duan et al., 2012) |

| 2.3 | Summer | The biogenic source of carbonyl compounds and more intensive photochemistry in summer | Beijing (Peking University, in northwest urban),China | (Rao et al., 2016) |

| 1.3 | Winter | The anthropogenic source (traffic emission) | Beijing (Peking University, in northwest urban),China | (Rao et al., 2016) |

| 0.59–1.95 | Summer | Higher ambient temperature, the photochemical reactions and the relatively higher humidity | West Guangzhou (Liwan District), China | (Lü et al., 2010) |

| 0.73–1.64 | Winter | Vehicular exhaust | West Guangzhou (Liwan District), China | (Lü et al., 2010) |

| 0.35–1.49 | Spring | − | West Guangzhou (Liwan District), China | (Lü et al., 2010) |

| 0.27–1.02 | Autumn | − | West Guangzhou (Liwan District), China | (Lü et al., 2010) |

| 0.11–1.45 | Summer | Higher ambient temperature, photochemical generation and the relatively higher humidity | North-East Guangzhou (Tianhe District), China | (Lü et al., 2010) |

| 0.69–1.73 | Winter | vehicular exhaust | North-East Guangzhou (Tianhe District), China | (Lü et al., 2010) |

| 0.04–1.40 | Spring | − | North-East Guangzhou (Tianhe District), China | (Lü et al., 2010) |

| 0.69–1.06 | Autumn | − | North-East Guangzhou (Tianhe District), China | (Lu et al., 2010) |

| 3.1 | Summer | Photochemical production | Metropolitan Area of Sao Paulo (MASP), Brazil | (Nogueira et al., 2014) |

| 2.3 | summer | Photochemical production | Whiteface Mountain (WFM) in New York State | (Khwaja and Narang, 2008) |

| 2.27 | winter | Photochemical production | Algerian territory: Algiers and Ouargla, Algeria | (Cecinato et al., 2002) |

| 0.65 | Winter | Direct vehicle emissions | Metropolitan Area of Sao Paulo (MASP), Brazil | (Nogueira et al., 2014) |

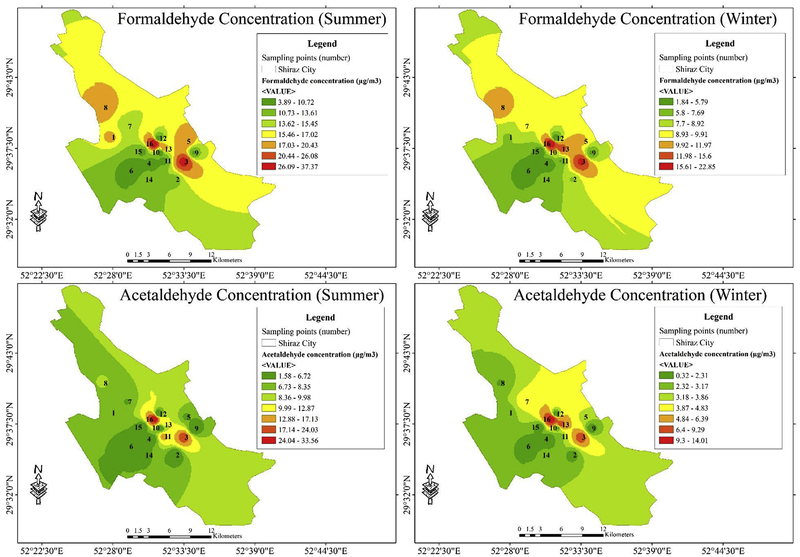

3.5. Spatial analysis of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde in summer and winter

The spatial distributions of FA and AA for summer and winter are shown in Fig. 3. The highest FA and AA concentrations in summer and winter were at locations 16 (Namazi square) and 3 (Valiasr square). This is due to proximity to coniferous and deciduous trees and significant traffic congestion. In addition, the results revealed that both species exhibited a similar spatial pattern between the two seasons. Their concentrations decrease as a function of distance from the main city squares (e.g., Namazi and Valiasr Squares).

Fig. 3.

The spatial distribution of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde in Shiraz during summer and winter.

3.6. Interrelationships between aldehyde concentrations and meteorology

Table 4 shows correlations between FA and AA based on mean concentrations in summer and winter. There were significant positive correlations between the two species in both seasons, suggeestive of similar emissions sources. Others have found similarly strong correlations (e.g., Morknoy et al. (2011), Duan et al. (2012), Huang et al. (2008)). Similarly, in this study a good correlation (high Spearman’s coefficient; r = 0.808 and p-value = 0.000 for FA AA in summer and r = 0.871 and p-value =0.000 for FA AA in winter) was obtained for FA and AA. The correlation coefficients (r) for FA and AA were higher in winter as compared with summer, likely due to more dependence on the emissions sources (e.g., traffic) and less dependence on photochemistry. Statistically significant relationships were found between temperature, FA, and AA in both seasons. No significant correlation was observed between the FA and AA concentrations with either wind speed, pressure, or humidity in the two seasons (p > 0.05).

Table 4.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients (r) between formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and meteorological parameters.

| Pollutant and variable | Formaldehyde | Acetaldehyde | Pressure | Temperature | Humidity | Wind speed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer | |||||||

| Formaldehyde | r | 1.000 | |||||

| P-value | |||||||

| Acetaldehyde | r | .808** | 1.000 | ||||

| P-value | .000 | ||||||

| Pressure | r | .344 | .173 | 1.000 | |||

| P-value | .192 | .522 | |||||

| Temperature | r | .649* | .522* | .090 | 1.000 | ||

| P-value | .004 | .049 | .739 | ||||

| Humidity | r | .028 | .037 | .097 | .042 | 1.000 | |

| P-value | .917 | .891 | .722 | .878 | |||

| Wind speed | r | .412 | .249 | .331 | .003 | .050 | 1.000 |

| P-value | .113 | .353 | .211 | .991 | .853 | ||

| Winter | |||||||

| Formaldehyde | r | 1.000 | |||||

| P-value | |||||||

| Acetaldehyde | r | .871** | 1.000 | ||||

| P-value | .000 | ||||||

| Pressure | r | .229 | .202 | 1.000 | |||

| P-value | .394 | .453 | |||||

| Temperature | r | .520* | .511* | .013 | 1.000 | ||

| P-value | .048 | .005 | .963 | ||||

| Humidity | r | .044 | .069 | .175 | .080 | 1.000 | |

| P-value | .871 | .798 | .517 | .769 | |||

| Wind speed | r | .077 | .001 | .492 | .084 | .096 | 1.000 |

| P-value | .776 | .996 | .055 | .757 | .724 | ||

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (p < 0.01).

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (p < 0.05).

3.7. Health risk assessment

Table 5 shows that the mean LTCRs calculated using CSF = 7.70 × 10−3 for AA (IRIS) in summer for 11 different age groups were between 9.25 × 10−5 and 9.69 × 10−6, which exceed the limit value by the US EPA. In addition, the average LTCRs computed using CSF = 7.70 × 10−3 for AA (IRIS) in winter were between 2.18 × 10−5 and 7.55 × 10−6, also in exceedance of recommended values suggested by the US EPA.

Table 5.

The LTCR calculated for AA and FA according to CSF proposed by IRIS and OEHHA.

| LTCR (summer) for acetaldehyde CSF = 7.70 × 10−3 for acetaldehyde (IRIS) | |||||||||||

| Age groups (year) | |||||||||||

| Birth to <1 | 1 to <2 | 2 to <3 | 3 to <6 | 6 to <11 | 11 to <16 | 16 to <21 | 21 to <61 | 61 to <71 | 71 to <81 | 81 and older | |

| LTCR, 5% | 8.85 × 10−5 | 9.23 × 10−6 | 7.82 × 10−6 | 6.64 × 10−6 | 4.33 × 10−6 | 2.46 × 10−6 | 2.35 × 10−6 | 2.04 × 10−6 | 1.67 × 10−6 | 1.58 × 10−6 | 1.57 × 10−6 |

| LTCR, mean | 5.26 × 10−5 | 5.09 × 10−5 | 4.26 × 10−5 | 4.03 × 10−5 | 2.80 × 10−5 | 1.79 × 10−5 | 1.30 × 10−5 | 1.21 × 10−5 | 1.19 × 10−5 | 9.69 × 10−6 | 9.25 × 10−5 |

| LTCR, 95% | 1.51 × 10−4 | 1.47 × 10−4 | 1.14 × 10−4 | 1.10 × 10−4 | 8.75 × 10−5 | 5.15 × 10−5 | 3.55 × 10−5 | 3.32 × 10−5 | 3.04 × 10−5 | 3.77 × 10−5 | 2.79 × 10−5 |

| LTCR (winter) for acetaldehyde CSF = 7.70 × 10−3 for acetaldehyde (IRIS) | |||||||||||

| LTCR, 5% | 3.62 × 10−6 | 3.64 × 10−6 | 3.07 × 10−6 | 2.93 × 10−6 | 1.91 × 10−6 | 1.2 × 10−6 | 8.11 × 10−7 | 8.45 × 10−7 | 7.81 × 10−7 | 6.79 × 10−7 | 6.06 × 10−7 |

| LTCR, mean | 2.12 × 10−5 | 2.18 × 10−5 | 1.82 × 10−5 | 1.68 × 10−5 | 1.22 × 10−5 | 7.55 × 10−6 | 5.50 × 10−6 | 5.04 × 10−6 | 4.58 × 10−6 | 4.24 × 10−6 | 3.74 × 10−6 |

| LTCR, 95% | 6.01 × 10−5 | 6.19 × 10−5 | 5.11 × 10−5 | 4.65 × 10−5 | 3.62 × 10−5 | 2.16 × 10−5 | 1.56 × 10−5 | 1.36 × 10−5 | 1.03 × 10−5 | 1.20 × 10−5 | 1.07 × 10−5 |

| LTCR (summer) for formaldehyde CSF = 4.55 × 102 for formaldehyde (IRIS) | |||||||||||

| Age groups (year) | |||||||||||

| Birth to <1 | 1 to <2 | 2 to <3 | 3 to <6 | 6 to <11 | 11 to <16 | 16 to <21 | 21 to <61 | 61 to <71 | 71 to <81 | 81 and older | |

| LTCR, 5% | 1.78 × 10−5 | 1.83 × 10−5 | 1.54 × 10−5 | 1.38 × 10−5 | 9.95 × 10−6 | 6.73 × 10−6 | 4.69 × 10−6 | 4.42 × 10−6 | 4.01 × 10−6 | 3.46 × 10−6 | 3.02 × 10−6 |

| LTCR, mean | 5.62 × 10−5 | 5.83 × 10−5 | 4.45 × 10−5 | 4.48 × 10−5 | 3.07 × 10−5 | 1.84 × 10−5 | 1.38 × 10−5 | 1.25 × 10−5 | 1.15 × 10−5 | 1.04 × 10−5 | 9.71 × 10−6 |

| LTCR, 95% | 1.19 × 10−4 | 1.12 × 10−4 | 9.36 × 10−5 | 9.61 × 10−5 | 6.63 × 10−5 | 3.93 × 10−5 | 2.92 × 10−5 | 2.57 × 10−5 | 2.58 × 10−5 | 2.21 × 10−5 | 2.13 × 10−5 |

| LTCR (winter) for formaldehyde CSF = 4.55 × 102 for formaldehyde (IRIS) | |||||||||||

| LTCR, 5% | 9.15 × 10−6 | 9.26 × 10−6 | 8.00 × 10−6 | 6.52 × 10−6 | 5.29 × 10−6 | 2.13 × 10−6 | 2.47 × 10−6 | 2.20 × 10−6 | 1.78 × 10−6 | 5.10 × 10−6 | 1.69 × 10−6 |

| LTCR, mean | 3.01 × 10−5 | 3.12 × 10−5 | 2.69 × 10−5 | 2.31 × 10−5 | 1.76 × 10−5 | 1.05 × 10−5 | 7.81 × 10−6 | 7.00 × 10−6 | 6.26 × 10−6 | 1.01 × 10−5 | 5.54 × 10−6 |

| LTCR, 95% | 7.03 × 10−5 | 7.25 × 10−5 | 6.04 × 10−5 | 5.44 × 10−5 | 4.05 × 10−5 | 2.42 × 10−5 | 1.82 × 10−5 | 1.61 × 10−5 | 1.40 × 10−5 | 1.78 × 10−5 | 1.24 × 10−5 |

| LTCR (summer) for acetaldehyde CSF = 1.00 × 102 for acetaldehyde (OEHHA) | |||||||||||

| Age groups (year) | |||||||||||

| Birth to <1 | 1 to <2 | 2 to <3 | 3 to <6 | 6 to <11 | 11 to <16 | 16 to <21 | 21 to <61 | 61 to <71 | 71 to <81 | 81 and older | |

| LTCR, 5% | 1.22 × 10−5 | 2.44 × 10−5 | 8.16 × 10−6 | 8.87 × 10−6 | 6.22 × 10−6 | 4.25 × 10−6 | 2.96 × 10−6 | 2.57 × 10−6 | 2.07 × 10−6 | 2.15 × 10−6 | 1.97 × 10−6 |

| LTCR, mean | 6.80 × 10−5 | 1.37 × 10−4 | 5.43 × 10−5 | 4.97 × 10−5 | 3.61 × 10−5 | 2.27 × 10−5 | 1.68 × 10−5 | 1.59 × 10−5 | 1.36 × 10−5 | 1.27 × 10−5 | 1.22 × 10−5 |

| LTCR, 95% | 1.84 × 10−4 | 4.06 × 10−4 | 1.56 × 10−4 | 1.36 × 10−4 | 1.03 × 10−4 | 6.20 × 10−5 | 4.72 × 10−5 | 4.56 × 10−5 | 4.00 × 10−5 | 3.77 × 10−5 | 3.57 × 10−5 |

| LTCR (winter) for acetaldehyde CSF = 1.00 × 102 for acetaldehyde (OEHHA) | |||||||||||

| LTCR, 5% | 4.63 × 10−6 | 4.60 × 10−6 | 4.30 × 10−6 | 3.55 × 10−6 | 2.47 × 10−6 | 1.55 × 10−6 | 1.15 × 10−6 | 1.22 × 10−6 | 1.03 × 10−6 | 9.54 × 10−7 | 7.94 × 10−7 |

| LTCR, mean | 2.81 × 10−5 | 2.87 × 10−5 | 2.84 × 10−5 | 2.04 × 10−5 | 1.56 × 10−5 | 9.28 × 10−6 | 7.23 × 10−6 | 6.26 × 10−6 | 5.79 × 10−6 | 5.61 × 10−6 | 4.82 × 10−6 |

| LTCR, 95% | 7.84 × 10−5 | 8.49 × 10−5 | 6.83 × 10−5 | 6.07 × 10−5 | 4.36 × 10−5 | 2.61 × 10−5 | 2.10 × 10−5 | 1.74 × 10−5 | 1.63 × 10−5 | 1.72 × 10−5 | 1.45 × 10−5 |

| LTCR (summer) for formaldehyde CSF = 2.10 × 102 for formaldehyde (OEHHA) | |||||||||||

| Age groups (year) | |||||||||||

| Birth to <1 | 1 to <2 | 2 to <3 | 3 to <6 | 6 to <11 | 11 to <16 | 16 to <21 | 21 to <61 | 61 to <71 | 71 to <81 | 81 and older | |

| LTCR, 5% | 8.27 × 10−5 | 8.20 × 10−5 | 7.30 × 10−5 | 6.20 × 10−5 | 4.74 × 10−5 | 3.01 × 10−5 | 2.43 × 10−5 | 2.03 × 10−5 | 1.72 × 10−5 | 1.58 × 10−5 | 1.58 × 10−5 |

| LTCR, mean | 2.58 × 10−4 | 2.50 × 10−4 | 2.19 × 10−4 | 1.87 × 10−4 | 1. 39 × 10−4 | 8.75 × 10−5 | 6.54 × 10−5 | 6.00 × 10−5 | 5.21 × 10−5 | 4.71 × 10−5 | 4.63 × 10−5 |

| LTCR, 95% | 5.42 × 10−4 | 5.31 × 10−4 | 4.91 × 10−4 | 3.94 × 10−4 | 2.97 × 10−4 | 1.85 × 10−4 | 1.44 × 10−4 | 1.33 × 10−4 | 1.16 × 10−4 | 1.05 × 10−4 | 9.86 × 10−5 |

| LTCR (winter) for formaldehyde CSF = 2.10 × 102 for formaldehyde (OEHHA) | |||||||||||

| LTCR, 5% | 4.17 × 10−5 | 3.77 × 10−5 | 3.61 × 10−5 | 3.33 × 10−5 | 2.32 × 10−5 | 1.41 × 10−5 | 1.05 × 10−5 | 1.05 × 10−5 | 1.17 × 10−5 | 2.27 × 10−5 | 6.81 × 10−6 |

| LTCR, mean | 1.45 × 10−4 | 1.46 × 10−4 | 1.22 × 10−4 | 1.06 × 10−4 | 8.16 × 10−5 | 5.5 × 10−5 | 3.64 × 10−5 | 3.50 × 10−5 | 3.81 × 10−5 | 4.86 × 10−5 | 2.52 × 10−5 |

| LTCR, 95% | 3.41 × 10−4 | 3.38 × 10−4 | 2.94 × 10−4 | 2.27 × 10−4 | 1.90 × 10−4 | 1.19 × 10−4 | 8.31 × 10−4 | 8.06 × 10−5 | 9.11 × 10−5 | 8.24 × 10−5 | 5.69 × 10−5 |

The mean LTCRs calculated using CSF = 4.55 × 10−2 for FA (IRIS) in summer from were between 5.83 × 10−5 and 9.71 × 10−6, which exceed recommended values by the US EPA. The average LTCRs estimated using CSF = 4.55 × 10−2 for FA (IRIS) in winter were between 3.12 × 10−5 and 7.81 × 10−6, and in exceedance of US EPA value.

Average LTCRs calculated using CSF = 1.00 × 10−2 for AA (OEHHA) in summer were between 1.37 × 10−4 and 6.80 × 10−5, which only were in exceedance of set values for ages of 1 to <2 years. The average LTCRs computed with CSF = 1.00 × 10−2 for AA (OEHHA) in winter were between 2.87 × 10−5 and 4.82 × 10−6, which were in exceedance of recommended values by the US EPA.

Moreover, the results of the current study reveal that the average LTCRs calculated using CSF = 2.10 × 10−2 for formalde-hyde (OEHHA) in summer in different age groups were between 4.63 × 10−5 and 2.52 × 10−4, which exceed for 5 different age groups (Birth to <1, 1 to <2, 2 to <3, and 3 to <6 years)

Finally, the average LTCRs estimated using CSF = 2.10 × 10−2 for FA (OEHHA) in winter were between 1.46 × 10−4 and 2.52 × 10−5, which were in exceedance for four different age groups (Birth to <1, 1 to <2, 2 to <3, and 3 to <6 years) according to the set values proposed by the US EPA and WHO.

Hence, the results obtained from this study indicate that Shiraz is especially harmful for children under 6 years of age with the LTCR being more than 1.06 × 10−4. Similar results have been acquired by in the ambient urban atmosphere of Bangkok (Thailand) (Kanjanasiranont et al., 2017), by bus stations of Hangzhou (China) (Weng et al., 2009), and by policemen working outdoors in Greece (Pilidis et al., 2009) with mean LTCR values of FA versus AA reported at 12.84 × 10−4 vs. 2.52 × 10−4, 2.2 × 10−4 vs. 2.7 × 10−5, and 2.06 × 10−4 – 1.75 × 10−3 vs unknown, respectively. For more context, Mølhave et al. (2016) reported average LTCR values for FA and AA as being 6.8 × 10−8 and 8.9 × 10−8, respectively, for indoor air in California.

HQs of FA ranged between 0.04 and 4.18 for both seasons, indicative of the need for concern about non-carcinogenic risk of FA in the study area. In addition, the HQs of AA were limited to only 0.42 and 0.97 for both seasons, which is at “an acceptable level “.

Table 6 shows comparison of the findings of health risk assessment in this work versus other areas. Similar to Shiraz, Rovira et al. (2016) reported that the HQ of FA in Tarragona County, Catalonia (Spain) was more than 1, indicative of non-carcinogenic risk (Table 6) (Rovira et al., 2016).

Table 6.

Comparison of the results of the health risk assessment in the current study versus others.

| HQ and LTCR | Formaldehyde | Acetaldehyde | Location | Outdoor or indoor | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HQ(a) | Mean | 1.53 | − | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (summer) |

| SD | 0.83 | − | ||||

| HQ(a) | Mean | 0.87 | − | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (winter) |

| SD | 0.50 | − | ||||

| HQ(b) | Mean | 0.07 | − | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (summer) |

| SD | 0.04 | − | ||||

| HQ(b) | Mean | 0.04 | − | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (winter) |

| SD | 0.02 | − | ||||

| HQ(c) | Mean | 4.18 | − | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (summer) |

| SD | 2.54 | − | ||||

| HQ(c) | Mean | 2.38 | − | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (winter) |

| SD | 1.64 | − | ||||

| HQ(d) | Mean | − | 0.97 | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (summer) |

| SD | − | 0.57 | ||||

| HQ(d) | Mean | − | 0.42 | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (winter) |

| SD | − | 0.20 | ||||

| LTCR(e) | − | − | 9.25 × 10−5 − 9.69 × 10−6 | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (summer) |

| LTCR(e) | − | 2.18 × 10−5 − 7.55 × 10−6 | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (winter) | |

| LTCR(f) | 5.83 × 10−5 − 9.71 × 10−6 | − | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (summer) | |

| LTCR(f) | 3.12 × 10−5 − 7.81 × 10−6 | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (winter) | ||

| LTCR(g) | − | 1.37 × 10−4 − 6.80 × 10−5 | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (summer) | |

| LTCR(g) | − | 2.87 × 10−5 − 4.82 × 10−6 | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (winter) | |

| LTCR(h) | 4.63 × 10−5 − 2.58 × 10−4 | − | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (summer) | |

| LTCR(h) | 1.46 × 10−4 − 2.52 × 10−5 | − | Shiraz, Iran | Outdoor (in the ambient air) | This study (winter) | |

| HQ | Mean | − | − | Guiyang, China | Indoor Environments | (Li et al., 2008) |

| LTCR | 6.96 × 10−6 − 2.48 × 10−4 | − | ||||

| HQ | Mean | − | − | Five cities (Harbin, Beijing, Shanghai, Changsha, and Shenzhen), China | Residential environment, Indoor | (Zheng et al., 2005) |

| LTCR | 3.41 × 10−3 | − | ||||

| HQ | Mean | − | − | Taipei, Taiwan | Office buildings, Indoor | (Wu et al., 2003) |

| LTCR | 2.06 × 10−4 − 1.75 × 10−3 | − | ||||

| HQ | Mean | Greek, Greece | Policemen- Outdoor | (Pilidis et al., 2009) | ||

| LTCR | 2.01 × 10−4 | |||||

| HQ | Mean | Greek, Greece | Laboratory technicians,Indoor | (Pilidis et al., 2009) | ||

| LTCR | 2.67 × 10−4 | |||||

| HQ | Mean | 0.31 | 0.09 | Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, | Office, Indoor | (Tunsaringkarn et al., 2012c) |

| LTCR | 2.22 × 10−5 | 2.89 × 10−6 | Thailand | |||

| HQ | Mean | 0.16 | 0.05 | Pathumwan district, Bangkok, Thailand | Gasoline Station workers, Outdoor | (Tunsaringkarn et al., 2012c) |

| LTCR | 1.14 × 10−5 | 1.60 × 10−6 | ||||

| HQ | Mean | 2.17 | − | Tarragona County, Catalonia, Spain. | Homes (terrace or balcony), | (Rovira et al., 2016) |

| LTCR | 4.72 × 10−4 − 9.45 × 10−4 | − | Outdoor | |||

| HQ | Mean | − | − | Bangkok, Thailand | Urban environments | (Kanjanasiranont et al., 2017) |

| LTCR | 2.84 × 10−4 | 2.52 × 10−4 | ||||

| HQ | Mean | − | − | Hangzhou, China | Bus stations (for staffs), Outdoor | (Weng et al., 2009) |

| LTCR | 2.2 × 10−4 | 2.7 × 10−5 | ||||

| HQ | Mean | − | − | Hangzhou, China | Bus stations (for costumers and | (Weng et al., 2009) |

| LTCR | 2.2 × 10−4 | 2.7 × 10−5 | passengers), Outdoor | |||

| HQ | Mean | − | − | Hangzhou, China | Railway stations (for staffs), Outdoor | (Weng et al., 2009) |

| LTCR | 2.00 × 10−4 | 4.5 × 10−5 | ||||

| HQ | Mean | − | − | Hangzhou, China | Railway stations (for costumers and | (Weng et al., 2009) |

| LTCR | 2.00 × 10−4 | 4.5 × 10−5 | passengers), Outdoor | |||

| HQ | Mean | − | − | Bangkok, Thailand | Petrol Station Workers, Outdoor | (Kitwattanavong et al. 2013) |

| LTCR | 7.81 × 10−6 − 1.04 × 10−5 | 1.39 × 10−6 − 2.45 × 10−6 | ||||

| HQ | Mean | 0.23 | 0.14 | Bangkok, Thailand | Petrol Station Workers, Outdoor | (Tunsaringkarn et al., 2012a) |

| LTCR | 1.89 × 10−5 | 4.32 × 10−6 | ||||

| HQ | Mean | 0.27 | 0.11 | Bangkok, Thailand | Roadside, Outdoor | (Tunsaringkarn et al., 2012a) |

| LTCR | 1.97 × 10−5 | 3.63 × 10−6 | ||||

| HQ | Mean | 0.40 | 0.19 | Bangkok, Thailand | Pathumwan district (gasoline station workers), Outdoor | (Tunsaringkarn et al., 2012b) |

| LTCR | 1.27 × 10−5 | 2.69 × 10−6 | ||||

| HQ | Mean | − | − | Fortaleza, Brazil | Hospital A, Indoor | (Sousa et al., 2011) |

| LTCR | 1.36 × 10−5 | 1.78 × 10−5 | ||||

| HQ | Mean | Fortaleza, Brazil | Hospital B, Indoor | (Sousa et al., 2011) | ||

| LTCR | 3.57 × 10−5 | 3.35 × 10−6 | ||||

| HQ | Mean | − | − | Californian, United State | Furniture, Indoor | (Mølhave et al., 1995) |

| LTCR | 6.8 × 10−8 − 8.9 × 10−8 | − | ||||

| HQ | Mean | − | − | Californian, United State | Furniture, Indoor | (Mølhave et al., 1995) |

| LTCR | 5.8 × 10−7 − 7.4 × 10−7 | − | ||||

HQ: hazard quotient; ILTCR: integrated lifetime cancer risk.

Rfc for formaldehyde (IRIS) = 9.83 × 10−3 mg m−3 (USEPA 2004).

Rfc for formaldehyde (EPA) = 2.00 × 10−1 mg m−3 (USEPA 1989).

Rfc for formaldehyde (CAPCOA, California EPA) = 3.6 × 10−3 mg m−3 (CalEPA 1997; Wu et al. 2003).

Rfc for acetaldehyde (EPA) = 9.00 × 10−3 mg m−3 (USEPA, 1999a, 1999b, 2004).

CSF = 7.70 × 10−3 (mg kg−1 day−1)−1 for acetaldehyde (IRIS) (Sousa et al., 2011; USEPA, 1996).

CSF = 4.55 × 10−2 (mg kg−1 day−1)−1 for formaldehyde (IRIS) (Sousa et al., 2011; USEPA, 1996).

CSF = 1.00 × 10−2 (mg kg−1 day−1)−1 for acetaldehyde (OEHHA) (OEHHA, 2009).

CSF = 2.10 × 10−2 (mg kg−1 day−1)−1 for formaldehyde (OEHHA) (OEHHA, 2009).

Sensitivity analyses of LTCR results for FA and AA are summarized in Table 7. Factors required included inhalation rate, body weight, averaging time, exposure duration, and exposure frequency. The percentage value relevant to each variable represents the amount of the LTCR accounted for by that variable. The concentration of FA and AA (>94.6%) had the most important effect on lifetime cancer risk in different age groups (11 age groups) for both summer and winter. In addition, FA and AA concentrations were especially influential (>97.20%) for three different age groups (21 to <61, 61 to <71 and 71 to <81 years) for both summer and winter.

Table 7.

Sensitivity analysis of LTCR model for FA and AA according to CFS proposed by OEHHA and IRIS. (C: concentration of the pollutant, IR: inhalation rate, ED: Exposure duration, BW: body weight, EF: Exposure frequency).

| Sensitivity, LTCR (summer) for acetaldehyde CSF = 1.00 × 10−2 for acetaldehyde (OEHHA) | |||||||||||

| Age groups (year) | |||||||||||

| Birth to <1 | 1 to <2 | 2 to <3 | 3 to <6 | 6 to <11 | 11 to <16 | 16 to <21 | 21 to <61 | 61 to <71 | 71 to <81 | 81 and older | |

| C(%) | 99.50 | 99.00 | 98.30 | 99.30 | 99.10 | 98.80 | 99.40 | 99.20 | 99.70 | 99.60 | 99.90 |

| IR (%) | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 00 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.10 |

| BW (%) | 0.40 | 00 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 00 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 00 |

| EF (%) | 00 | 00 | 0.80 | 0.10 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 00 | 0.70 | 00 | 0.10 | 00 |

| Sensitivity, LTCR (winter) for acetaldehyde CSF = CSF = 7.70 × 10−3 for acetaldehyde (IRIS) | |||||||||||

| Age groups (year) | |||||||||||

| C(%) | 99.40 | 98.20 | 97.20 | 97.90 | 98.10 | 99.50 | 98.80 | 99.70 | 98.90 | 99.70 | 99.20 |

| IR (%) | 0.10 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 00 | 0.30 | 00 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.40 |

| BW(%) | 0.40 | 0.10 | 1.90 | 0.20 | 00 | 00 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 00 | 00 | 0.10 |

| EF(%) | 0.10 | 1.20 | 0.50 | 1.60 | 1.50 | 0.5 | 0.70 | 00 | 0.20 | 00 | 0.30 |

| Sensitivity, LTCR (summer) CSF = 4.55 × 10−2 for formaldehyde (IRIS) (USEPA) | |||||||||||

| Age groups (year) | |||||||||||

| Birth to <1 | 1 to <2 | 2 to <3 | 3 to <6 | 6 to <11 | 11 to <16 | 16 to <21 | 21 to <61 | 61 to <71 | 71 to <81 | 81 and older | |

| C(%) | 97.20 | 96.40 | 98.50 | 97.10 | 98.80 | 99.30 | 98.50 | 99.70 | 99.00 | 99.4 | 97.90 |

| IR (%) | 0.90 | 2.50 | 0.80 | 0.50 | 1.10 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.80 |

| BW (%) | 0.10 | 0.90 | 0.40 | 1.30 | 00 | 0.10 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 |

| EF (%) | 0.90 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 1.60 | 00 | 0.30 | 1.30 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 1.30 |

| Sensitivity, LTCR (winter) CSF = 4.55 × 10−2 for formaldehyde (IRIS) (USEPA) | |||||||||||

| Age groups (year) | |||||||||||

| C(%) | 97.60 | 96.80 | 99.60 | 99.10 | 99.40 | 99.50 | 99.80 | 99.40 | 99.70 | 97.40 | 98.90 |

| BW (%) | 0.90 | 1.60 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 00 | 0.20 | 00 | 00 | 0.70 | 1.70 | 0.30 |

| IR(%) | 0.30 | 0.90 | 00 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 00 | 0.10 | 00 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| EF(%) | 1.20 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 00 | 0.30 | 00 | 0.20 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.80 | 0.70 |

| Sensitivity, LTCR (summer) for acetaldehyde CSF = 1.00 × 10−2 for acetaldehyde (OEHHA) | |||||||||||

| Age groups (year) | |||||||||||

| Birth to <1 | 1 to <2 | 2 to <3 | 3 to <6 | 6 to <11 | 11 to <16 | 16 to <21 | 21 to <61 | 61 to <71 | 71 to <81 | 81 and older | |

| C(%) | 98.30 | 97.90 | 98.90 | 99.00 | 99.20 | 98.40 | 98.80 | 99.80 | 99.60 | 99.30 | 97.70 |

| IR (%) | 1.00 | 1.40 | 1.00 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 00 | 00 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 1.40 |

| BW (%) | 0.50 | 0.40 | 00 | 0.80 | 0.40 | 00 | 0.10 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 0.50 |

| EF (%) | 0.20 | 0.30 | 00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 1.10 | 0.10 | 00 | 0.30 | 0.40 |

| Sensitivity, LTCR (winter) for acetaldehyde CSF = 1.00 × 10−2 for acetaldehyde (OEHHA) | |||||||||||

| C(%) | 98.50 | 97.90 | 99.30 | 98.52 | 98.50 | 99.30 | 99.90 | 100 | 99.60 | 99.30 | 98.90 |

| IR (%) | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 0.20 | 0.60 | 00 |

| BW(%) | 0.40 | 1.40 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 00 | 0.20 | 00 | 00 | 0.10 | 00 | 0.10 |

| EF(%) | 0.20 | 00 | 0.10 | 0.90 | 0.20 | 0.50 | 00 | 00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.90 |

| Sensitivity, LTCR (summer) CSF = 2.10 × 10−2 for formaldehyde (OEHHA) | |||||||||||

| Age groups (year) | |||||||||||

| Birth to <1 | 1 to <2 | 2 to <3 | 3 to <6 | 6 to <11 | 11 to <16 | 16 to <21 | 21 to <61 | 61 to <71 | 71 to <81 | 81 and older | |

| C(%) | 94.6 | 98.00 | 98.10 | 98.60 | 99.50 | 98.30 | 98.40 | 99.00 | 98.50 | 99.40 | 98.40 |

| IR (%) | 4.10 | 1.50 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.60 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 00 | 0.10 | 0.70 |

| BW (%) | 1.0 | 0.40 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 00 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 00 |

| EF (%) | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.90 |

| Sensitivity, LTCR (winter) CSF = 2.10 × 10−2 for formaldehyde (OEHHA) | |||||||||||

| Age groups (year) | |||||||||||

| C(%) | 97.40 | 97.90 | 97.70 | 98.80 | 98.50 | 99.10 | 99.20 | 99.90 | 99.40 | 97.20 | 98.80 |

| BW (%) | 0.20 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 00 | 00 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.10 |

| IR(%) | 1.60 | 1.30 | 0.90 | 0.40 | 0.90 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 2.20 | 0.60 |

| EF(%) | 0.80 | 0.10 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 00 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.50 |

4. Conclusions

This work reports on measurements of FA and AA concentrations in the ambient urban atmosphere of Shiraz, Iran in the summer and winter. The major findings of this work are as follows:

The mean (±SD) concentrations of FA and AA in the summer versus winter were as follows, respectively: 15.07 ± 9.17 vs. 8.57 ± 5.91 μg m−3 and 8.40 ± 4.29 vs. 3.52 ± 1.69 μg m−3. The mean FA:AA ratios in the summer and winter were 1.80 and 2.43, respectively.

Significant positive correlations between FA and AA are indicative of the same emission sources in the summer and winter.

The mean inhalation lifetime cancer risk (LTCR), according to IRIS (CSF = 7.70 × 10−3), for AA in summer and winter was between 7.55 × 10−6 and 9.25 × 10−5 and in exceedance of the recommended value by the US EPA. In addition, the mean inhalation LTCR, according to IRIS (CSF = 4.55 × 10−2), for FA in summer and winter was between 7.81 × 10−6 and 5.83 × 10−5, and also in exceedance of the recommended value by the US EPA.

The average LTCR according to OEHHA (CSF = 1.00 × 10−2) for AA in summer and winter was between 4.82 × 10−6 and 1.37 × 10−4, respectively, which only was in exceedance for age bracket between 1 and < 2 years. Furthermore, the average LTCR according to OEHHA (CSF = 2.10 × 10−2) for FA in summer and winter was between 2.52 × 10−5 and 2.58 × 10−4, which was in exceedance for five different age groups (Birth to <1, 1 to <2, 2 to <3, 3 to <6, and 6 to <11 years). Hence, Shiraz’s pollution is especially harmful for children under 6 years of age.

The HQs of FA ranged from 0.04 to 4.18 for both seasons, indicating that the potential risk can be serious in the study area, while the HQs of AA were limited from 0.42 to 0.97, and considered to be less harmful (i.e., “acceptable hazard”).

The findings of this study have implications for public health near populated and congested areas, where exposure to such harmful VOCs can have deleterious effects. This study showed that the main sources of FA and AA in ambient air are mobile sources (traffic emission) with especially high levels during rush hours. Hence, it is suggested that management solutions be considered to reduce concentrations of FA and AA during rush hours.

Acknowledgements

AS acknowledges Grant 2 P42 ES04940–11 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Superfund Research Program, NIH.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.07.037.

References

- ACGIH, 2014. TLVs and BEIs: Based on the Documentation of the Threshold Limit Values for Chemical Substances and Physical Agents and Biological Exposure Indices, Cincinnati, OH. [Google Scholar]

- Alvim DS, Gatti LV, Santos M.H.d., Yamazaki A, 2011. Studies of the volatile organic compounds precursors of ozone in Sao Paulo city. Eng. Sanitária Ambient 16, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LG, Lanning JA, Barrell R, Miyagishima J, Jones RH, Wolfe P, 1996. Sources and sinks of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde: an analysis of Denver’s ambient concentration data. Atmos. Environ 30, 2113–2123. [Google Scholar]

- Arfaeinia H, Kermani M, Aghaei M, Asl FB, Karimzadeh S, 2017. Comparative investigation of health quality of air in Tehran, Isfahan and Shiraz metropolises in 2011–2012. J. Health Field 1. [Google Scholar]

- Barkhordari A, Azari MR, Zendehdel R, Heidari M, 2017. Analysis of formalde-hyde and acrolein in the aqueous samples using a novel needle trap device containing nanoporous silica aerogel sorbent. Environ. Monit. Assess 189, 171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauri N, Bauri P, Kumar K, Jain V, 2016. Evaluation of seasonal variations in abundance of BTXE hydrocarbons and their ozone forming potential in ambient urban atmosphere of Dehradun (India). Air Qual. Atmos. Health 9, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bradman A, Gaspar F, Castorina R, Williams J, Hoang T, Jenkins P, McKone T, Maddalena R, 2017. Formaldehyde and acetaldehyde exposure and risk characterization in California early childhood education environments. Indoor Air 27, 104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CalEPA, 1997. Technical SupportDocument for the Determination of Non-cancer Chronic Reference Exposure Lev-els, Air Toxicology and EpidemiologySection. California Environ-mental Protection Agency, Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- Campo Ojeda A, 2003. Límites de exposicion profesional para agentes químicos en España 2003, Curso de Ecoeficiencia en la Disposición Final de Residuos Sólidos Riesgos a la Salud Humana. AIDIS, p. 18 In Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- Canada, H., 2005. Residential Indoor Air Quality Guideline. Formaldehyde. [Google Scholar]

- Cecinato A, Yassaa N, Di Palo V, Possanzini M, 2002. Observation of volatile and semi-volatile carbonyls in an Algerian urban environment using dinitrophenylhydrazine/silica-HPLC and pentafluorophenylhydrazine/silica-GCMS. J. Environ. Monit 4, 223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Y, Feng Y, Wen S, Lü H, Yu Z, Zhang W, Sheng G, Fu J, 2007. Determination of carbonyl compounds in the atmosphere by DNPH derivatization and LC–ESI-MS/MS detection. Talanta 72, 539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa SM, Arbilla G, Martins EM, Quitêrio SL, de Souza Guimarães C, Gatti LV, 2010. Five years of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde monitoring in the Rio de Janeiro downtown area–Brazil. Atmos. Environ 44, 2302–2308. [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa SM, Martins EM, Arbilla G, 2003. Formaldehyde and acetaldehyde in a high traffic street of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Atmos. Environ 37, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Crosbie E, Sorooshian A, Monfared NA, Shingler T, Esmaili O, 2014. A multi-year aerosol characterization for the greater Tehran area using satellite, surface, and modeling data. Atmosphere 5, 178–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bruin YB, Koistinen K, Kephalopoulos S, Geiss O, Tirendi S, Kotzias D, 2008. Characterisation of urban inhalation exposures to benzene, formaldehyde and acetaldehyde in the European Union. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser 15, 417–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho AB, Kato M, Rezende MM, de Pedro PP, de Andrade AJB, 2008. Determination of carbonyl compounds in the atmosphere of charcoal plants by HPLC and UV detection. J. Separ. Sci 31, 1686–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Mendonça Ochs S, de Almeida Furtado L, Netto ADP, 2015. Evaluation of the concentrations and distribution of carbonyl compounds in selected areas of a Brazilian bus terminal. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser 22, 9413–9423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani M, Fazlzadeh M, Sorooshian A, Tabatabaee HR, Miri M, Baghani AN, Delikhoon M, Mahvi AH, Rashidi M, 2018. Characteristics and health effects of BTEX in a hot spot for urban pollution. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf 155, 133–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J, Guo S, Tan J, Wang S, Chai F, 2012. Characteristics of atmospheric carbonyls during haze days in Beijing, China. Atmos. Res 114, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Eller PM, Cassinelli ME, 2003. NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods: Formalde-hyde Method 2016. Diane Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- EPA, U., 2011. Exposure Factors Handbook 2011 Edition (Final). US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Fathabadi MKF, Hajizadeh Y, 2016. Measurement of airborne asbestos levels in high traffic areas of Shiraz, Iran, in winter 2014. Int. J. Environ. Health Eng 5, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Fung K, Grosjean D, 1981. Determination of nanogram amounts of carbonyls as 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazones by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Chem 53, 168–171. [Google Scholar]

- Fung K, Wright B, 1990. Measurement of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde using 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine-impregnated cartridges during the carbonaceous species methods comparison study. Aerosol Sci. Technol 12, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert NL, Guay M, Miller JD, Judek S, Chan CC, Dales RE, 2005. Levels and determinants of formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acrolein in residential indoor air in Prince Edward Island, Canada. Environ. Res 99, 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Wei Y, Cheng J, Jiang T, Chen L, Xu B, 2017. Health risk assessment and personal exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) in metro carriages—a case study in Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ 574, 1432–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granby K, Christensen CS, Lohse C, 1997. Urban and semi-rural observations of carboxylic acids and carbonyls. Atmos. Environ 31, 1403–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean E, Williams EL, Grosjean D, 1993. Ambient levels of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde in Atlanta, Georgia. Air Waste 43, 469–474. [Google Scholar]

- Guideline IAQ, 1991. Formaldehyde in the Home. State of California Air Resources Board, Research Division. [Google Scholar]

- Hazrati S, Rostami R, Farjaminezhad M, Fazlzadeh M, 2016a. Preliminary assessment of BTEX concentrations in indoor air of residential buildings and atmospheric ambient air in Ardabil, Iran. Atmos. Environ 132, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hazrati S, Rostami R, Fazlzadeh M, 2015. BTEX in indoor air of waterpipe cafês: levels and factors influencing their concentrations. Sci. Total Environ 524–525, 347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazrati S, Rostami R, Fazlzadeh M, Pourfarzi F, 2016b. Benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene concentrations in atmospheric ambient air of gasoline and CNG refueling stations. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 9, 403–409. [Google Scholar]

- Health U.D.o., Services H, 1999. Toxicological Profile for Formaldehyde. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Atlanta. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho SSH, Cheng Y, Bai Y, Ho KF, Dai WT, Cao JJ, Lee SC, Huang Y, Ip HSS, Deng WJ, 2016. Risk assessment of indoor formaldehyde and other carbonyls in campus environments in northwestern China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res 16, 1967–1980. [Google Scholar]

- Holmström M, Wilhelmsson B, Hellquist H, Rosên G, 1989. Histological changes in the nasal mucosa in persons occupationally exposed to formaldehyde alone and in combination with wood dust. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 107, 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HSE, 2011. EH40/2005 Workplace Exposure Limits.

- Huang J, Feng Y, Li J, Xiong B, Feng J, Wen S, Sheng G, Fu J, Wu M, 2008. Characteristics of carbonyl compounds in ambient air of Shanghai, China. J. Atmos. Chem 61, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- IARC, 1999. The IARC Monographs Series. Overall Evaluations of Carcinogenicity to Humans, Acetaldehyde [75-07-0] (Vol. 71, 1999) and Formaldehyde [50-00-0] (Vol. 88, 2004).

- ISO, 2001. Determination of Formaldehyde Andother Carbonyl Compounds -Active Sampling Method. Indoor Air -Part 3. [Google Scholar]

- ITCOH, I.T.C.o.O.H., 2012. Occupational Exposure Limit for Chemical Substances. ITCOH, Tehran. [Google Scholar]

- Kanjanasiranont N, Prueksasit T, Morknoy D, 2017. Inhalation exposure and health risk levels to BTEX and carbonyl compounds of traffic policeman working in the inner city of Bangkok, Thailand. Atmos. Environ 152, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kesselmeier J, Bode K, Hofmann U, Müller H, Schäfer L, Wolf A, Ciccioli P, Brancaleoni E, Cecinato A, Frattoni M, 1997. Emission of short chained organic acids, aldehydes and monoterpenes from Quercus ilex L. and Pinus pinea L. in relation to physiological activities, carbon budget and emission algorithms. Atmos. Environ 31, 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Khwaja HA, Narang A, 2008. Carbonyls and non-methane hydrocarbons at a rural mountain site in northeastern United States. Chemosphere 71, 2030–2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Gupta I, Brandt J, Kumar R, Dikshit AK, Patil RS, 2016. Air quality mapping using GIS and economic evaluation of health impact for Mumbai City, India. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc 66, 470–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latysh NE, Wetherbee GA, 2012. Improved mapping of National Atmospheric Deposition Program wet-deposition in complex terrain using PRISM-gridded data sets. Environ. Monit. Assess 184, 913–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Gong J, Zhou J, 2014. Spatial interpolation of fine particulate matter concentrations using the shortest wind-field path distance. PLoS One 9, e96111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zhou X, Kalo M, Piltner R, 2016. Spatiotemporal interpolation methods for the application of estimating population exposure to fine particulate matter in the contiguous U.S. And a real-time web application. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 13, 749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lü H, Cai Q-Y, Wen S, Chi Y, Guo S, Sheng G, Fu J, 2010. Seasonal and diurnal variations of carbonyl compounds in the urban atmosphere of Guangzhou, China. Sci. Total Environ 408, 3523–3529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lü H, Tian J-J, Cai Q-Y, Wen S, Liu Y, Li N, 2016. Levels and health risk of carbonyl compounds in air of the library in Guangzhou, South China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res 16, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar]

- Lui K, Ho SSH, Louie PK, Chan C, Lee S, Hu D, Chan P, Lee JCW, Ho K, 2017. Seasonal behavior of carbonyls and source characterization of formaldehyde (HCHO) in ambient air. Atmos. Environ 152, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mannucci PM, Franchini M, 2017. Health effects of ambient air pollution in developing countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 14, 1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masih A, Lall AS, Taneja A, Singhvi R, 2016. Inhalation exposure and related health risks of BTEX in ambient air at different microenvironments of a terai zone in north India. Atmos. Environ 147, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Missia DA, Demetriou E, Michael N, Tolis E, Bartzis JG, 2010. Indoor exposure from building materials: a field study. Atmos. Environ 44, 4388–4395. [Google Scholar]

- Mølhave L, Dueholm S, Jensen L, 1995. Assessment of exposures and health risks related to formaldehyde emissions from furniture: a case study. Indoor Air 5, 104–119. [Google Scholar]

- Morknoy D, Khummongkol P, Prueaksasit T, 2011. Seasonal and diurnal concentrations of ambient formaldehyde and acetaldehyde in Bangkok. Water, Air, Soil Pollut 216, 693–702. [Google Scholar]

- Müller K, Haferkorn S, Grabmer W, Wisthaler A, Hansel A, Kreuzwieser J, Cojocariu C, Rennenberg H, Herrmann H, 2006. Biogenic carbonyl compounds within and above a coniferous forest in Germany. Atmos. Environ 40, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Müller K, Pelzing M, Gnauk T, Kappe A, Teichmann U, Spindler G, Haferkorn S, Jahn Y, Herrmann H, 2002. Monoterpene emissions and carbonyl compound air concentrations during the blooming period of rape (Brassica napus). Chemosphere 49, 1247–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naya M, Nakanishi J, 2005. Risk assessment of formaldehyde for the general population in Japan. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 43, 232–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neghab M, Delikhoon M, Norouzian Baghani A, Hassanzadeh J, 2017. Exposure to cooking fumes and acute reversible decrement in lung functional capacity. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med 8, 207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIOSH, 1993. Formaldehyde: Method 2016. NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods (NMAM). Issue 2, dated 15 August 1993-Page 2 of 4. [Google Scholar]

- NIOSH, T.N.I.f.O.S.a.H., 2003. Formaldehyde: Method 2016. NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods (NMAM), 2, pp. 1–7. Washington, DC (U.S.). [Google Scholar]

- NIOSH, N.I.f.O.S.a.H., 2004. International Chemical Safety Cards. Formaldehyde; Atlanta, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira T, Dominutti PA, de Carvalho LRF, Fornaro A, de Fatima Andrade M, 2014. Formaldehyde and acetaldehyde measurements in urban atmosphere impacted by the use of ethanol biofuel: metropolitan Area of Sao Paulo (MASP), 2012–2013. Fuel 134, 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira T, Dominutti PA, Fornaro A, Andrade M.d.F., 2017. Seasonal trends of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde in the megacity of São Paulo. Atmosphere 8, 144. [Google Scholar]

- OEHHA, 2005. Chronic Toxicity Summary, Formaldehyde. California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, California. [Google Scholar]

- OEHHA, 2009. California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment: Acetaldehyde. [Google Scholar]

- OEHHA, O.o.E.H.H.A., 2014. Hot Spots Unit Risk and Cancer Potency Values.

- OSHA, O.S.H.A., 2011. OSHA Factsheet: Formaldehyde. OSHA, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Pang X, Lee X, 2010. Temporal variations of atmospheric carbonyls in urban ambient air and street canyons of a Mountainous city in Southwest China. Atmos. Environ 44, 2098–2106. [Google Scholar]

- Pazdrak K, Górski P, Krakowiak A, Ruta U, 1993. Changes in nasal lavage fluid due to formaldehyde inhalation. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 64, 515–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilidis GA, Karakitsios SP, Kassomenos PA, Kazos EA, Stalikas CD, 2009. Measurements of benzene and formaldehyde in a medium sized urban environment. Indoor/outdoor health risk implications on special population groups. Environ. Monit. Assess 150, 285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possanzini M, Di Palo V, Cecinato A, 2002. Sources and photodecomposition of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde in Rome ambient air. Atmos. Environ 36, 3195–3201. [Google Scholar]

- Rad HD, Babaei AA, Goudarzi G, Angali KA, Ramezani Z, Mohammadi MM, 2014. Levels and sources of BTEX in ambient air of Ahvaz metropolitan city. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 7, 515–524. [Google Scholar]

- RAIS, T.R.A.I.S., 2014.

- Rao Z, Chen Z, Liang H, Huang L, Huang D, 2016. Carbonyl compounds over urban Beijing: concentrations on haze and non-haze days and effects on radical chemistry. Atmos. Environ 124, 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues MC, Guarieiro LL, Cardoso MP, Carvalho LS, Da Rocha GO, De Andrade JB, 2012. Acetaldehyde and formaldehyde concentrations from sites impacted by heavy-duty diesel vehicles and their correlation with the fuel composition: diesel and diesel/biodiesel blends. Fuel 92, 258–263. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez AA, de Loera A, Powelson MH, Galloway MM, De Haan DO, 2017. Formaldehyde and acetaldehyde increase aqueous-phase production of imidazoles in methylglyoxal/amine mixtures: quantifying a secondary organic aerosol formation mechanism. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett 4, 234–239. [Google Scholar]

- Rovira J, Roig N, Nadal M, Schuhmacher M, Domingo JL, 2016. Human health risks of formaldehyde indoor levels: an issue of concern. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part C Environ. Health Sci 51, 357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch GM, Clary JJ, Rinehart WE, Bolte HF, 1983. A 26-week inhalation toxicity study with formaldehyde in the monkey, rat, and hamster. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 68, 329–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthammer T, Mentese S, Marutzky R, 2010. Formaldehyde in the indoor environment. Chem. Rev 110, 2536–2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Säteri J, 2002. Finnish classification of indoor climate 2000: Revised target values, Proceedings of The 9th International Conference on Indoor Air Quality and Climate. Indoor Air; 643–648. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar C, Chatterjee A, Majumdar D, Roy A, Srivastava A, Ghosh SK, Raha S, 2017. How the atmosphere over eastern himalaya, India is polluted with carbonyl Compounds? Temporal variability and identification of sources. Aerosol Air Qual. Res 17, 2206–2223. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena P, Ghosh C, 2012. A review of assessment of benzene, toluene, ethyl-benzene and xylene (BTEX) concentration in urban atmosphere of Delhi. Int. J. Phys. Sci 7, 850–860. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard D, 1968. A two-dimensional interpolation function for irregularly-spaced data In: Proceedings of the 1968 23rd ACM National Conference. ACM, pp. 517–524. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa FW, Caracas IB, Nascimento RF, Cavalcante RM, 2011. Exposure and cancer risk assessment for formaldehyde and acetaldehyde in the hospitals, Fortaleza-Brazil. Build. Environ 46, 2115–2120. [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Centre of Iran (SCI), I., 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen K, Jensen HN, Sivertsen I, Sjaastad AK, 2002. Exposure to cooking fumes in restaurant kitchens in Norway. Ann. Occup. Hyg 46, 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner RL, Meng Z, 1984. Seasonal variations in ambient atmospheric levels of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde. Environ. Sci. Technol 18, 723–726. [Google Scholar]

- Til H, Woutersen R, Feron V, Clary J, 1988. Evaluation of the oral toxicity of acetaldehyde and formaldehyde in a 4-week drinking-water study in rats. Food Chem. Toxicol 26, 447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunsaringkarn T, Morknoy D, Siriwong W, Rungsiyothin A, Nopparatbundit S, 2012a. Carbonyl compounds exposures among gasoline station workers and their associated health risk. J. Health Res 26, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Tunsaringkarn T, Prueksasit T, Kitwattanavong M, Siriwong W, Sematong S, Zapuang K, Rungsiyothin A, 2012b. Cancer risk analysis of benzene, formal-dehyde and acetaldehyde on gasoline station workers. J. Environ. Eng. Ecol. Sci 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tunsaringkarn T, Prueksasit T, Morknoy D, Semathong S, Rungsiyothin A, Zapaung K, 2014. Ambient air’s volatile organic compounds and potential ozone formation in the urban area, Bangkok, Thailand. J. Environ. Occup. Sci 3, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Tunsaringkarn T, Siriwong W, Prueksasit T, Sematong S, Zapuang K, Rungsiyothin A, 2012c. Potential risk comparison of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde exposures in office and gasoline station workers. IJSRP 2, 2250–3153. [Google Scholar]

- U.S.EPA, 2000. Control of Emission of Hazardous Air Pollutants from Motor Vehicles and Motor Vehicle Fuel. Environmental Protection Agency, 2000, EPA-420-R-00–023. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA, 1989. National Center for Environmental Assessment. Formaldehyde; CASRN 50-00-0. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA, 1996. Determination of Formaldehyde in Ambient Air Using Adsorbent Cartridge Followed by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), EPA Method: TO-11A. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA, 1999a. Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) on Acetaldehyde. National Center for Environmental Assessment, Office of Research and Development; Washington, D.C. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA, 1999b. Compendium of Methods for the Determination of Toxic Organic Compounds in Ambient Air, Method TO-11A: Center for Environmental Research Information. Office of Research and Development, Cincinnati. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA, 2004. Integrated Risk Information.

- Vainiotalo S, Matveinen K, 1993. Cooking fumes as a hygienic problem in the food and catering industries. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J 54, 376–382. [Google Scholar]

- Viskari E-L, Vartiainen M, Pasanen P, 2000. Seasonal and diurnal variation in formaldehyde and acetaldehyde concentrations along a highway in Eastern Finland. Atmos. Environ 34, 917–923. [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Tong H, Yan X, Sheng L, Yang J, Liu S, 2005. Determination of volatile carbonyl compounds in cigarette smoke by LC-DAD. Chromatographia 62, 631–636. [Google Scholar]

- Weng M, Zhu L, Yang K, Chen S, 2009. Levels and health risks of carbonyl compounds in selected public places in Hangzhou, China. J. Hazard Mater 164, 700–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu PC, Li YY, Lee CC, Chiang CM, Su HJ, 2003. Risk assessment of formal-dehyde in typical office buildings in Taiwan. Indoor Air 13, 359–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 1987. WHO Air Quality Guidelines for Europe, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 1987. WHO Regional Publications, Copenhagen, Denmark: European Series. [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2000. Air Quality Guidelines for Europe WHO Regional Publications; European Series, No. 91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Wen S, Lü H, Feng Y, Wang X, Sheng G, Fu J, 2008. Characteristics of atmospheric carbonyls and VOCs in forest park in south China. Environ. Monit. Assess 137, 275–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]