Abstract

Objective. To define course objectives for a model global health course in a pharmacy curriculum.

Methods. A modified Delphi process was used to determine a consensus among proposed course objectives. A three-round email panel was sent to members of three special interest groups (SIGs) within the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (Public Health, Global Pharmacy Education, and Health Disparities and Cultural Competence) to recruit educators broadly interested or engaged in this area of education. An initial list of 80 potential course objectives across 11 domains was proposed for inclusion. Objectives that were cumulatively rated as either “extremely important” or “very important” by at least 75%, 80%, and 85% of respondents in each of the three rounds, respectively, were moved forward (first and second rounds) or accepted (third round).

Results. Responses were received from 87, 73, and 70 faculty panel members in the three consecutive rounds. The initial list of proposed objectives was narrowed to 65 objectives (19% reduction), and 38 objectives (53%) after the first and second rounds, respectively. The final list was composed of 20 objectives from seven domains. Global burden of disease and social/environmental determinants of health contained the most objectives selected by consensus.

Conclusion. The process identified a consensus for course objectives for a model global health education course. These objectives can be used by pharmacy faculty to align global health education in the profession.

Keywords: global health, pharmacy education, curricular development

INTRODUCTION

Over recent years, the role of the pharmacist in public health has grown in clarity and popularity, particularly through the provision of immunization and health promotion activities.1-3 However, pharmacist involvement within the realm of global health has lagged behind despite having similar potential for contribution to patient care.4 Part of this hesitancy was because of a partial understanding of what global health is or what it involves, and how pharmacists can support both product and patient-centered activities. Yet, multiple opportunities for pharmacists in global health exist, including involvement in clinical care for the underserved, relief/disaster efforts, regulatory development, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and volunteerism.5-7 Although debated, the most commonly used definition of global health is “an area for study, research, and practice that places a priority on improving health for all people worldwide… [it] emphasizes transnational health issues, determinants, and solutions; involves many disciplines within and beyond the health sciences and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration; and is a synthesis of population-based prevention with individual-level clinical care.”8 Importantly, global health does not refer solely to internationally based activities, but encompasses all efforts aimed to achieve equity for health care across the world, whether that community be local or abroad. As global health has been gaining traction quickly, so has the opportunity and provision of pharmacist services within the field. Accordingly, pharmacy education is an ideal starting point for exposure and integration.

In 2015, the Global Pharmacy Education (GPE) Special Interest Group (SIG) of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) published a white paper discussing the relevance of the 2013 Center for Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) Educational Outcomes to global health education.9 Included were recommendations for pedagogical and assessment opportunities regarding integration of global education into the pharmacy curriculum, and the rationale for this emerging area of curriculum. Notably, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) expressed a commitment to “a global perspective on pharmacy education and patient welfare” in the 2016 Standards, communicating a benefit to this type of education.10 Potential benefits derived from education in global health included an increasing prioritization of this area across other health professions, and increased job marketability of those with global experience. Skills gained through global health education are not only applicable and relevant to a professional role abroad, but also across areas that include the provision of care to the underserved, cultural relativism, humanistic communication and development of care strategies that reflect individual and population-based needs.9

Bailey and DiPietro Mager assessed global health education across 133 US schools and colleges of pharmacy and identified 29 programs offering dual degrees, required courses or affiliations with global centers.11 In addition, they found that more than 50 programs had international experience offerings, in the form of introductory or advanced pharmacy practice experiences (IPPE/APPE), mission/service trips or related experiences.11 However, limited published guidance is available on curricular structures for global health education in pharmacy education. Addo-Atuah and colleagues described an example of implementation of a global health elective course that demonstrated improvement in knowledge, attitudes, and perception of the pharmacists’ role and opportunities.12 Even with the wide availability of global health education across pharmacy curricula and preliminary evidence to support its inclusion, there remains scarce literature regarding course frameworks, objectives or competencies for global health in this area.

With increasing interest in pharmacy involvement in global health, guidance on educational outcomes would be useful to support the development of the skillset to meet the challenges of this area of practice. Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to define course objectives for a model global health course in a pharmacy curriculum achieved through the use of a modified Delphi process among stakeholders in this area of education. This method has been used successfully in other studies related to pharmacy education and, therefore, was adopted for this study so as to formalize and standardize the process.13,14

METHODS

A modified Delphi process was used across a group of pharmacy educators in the US who were engaged or interested in global health education. The process uses a systematic, multistage iterative series of questionnaires (rounds) that seek expert opinion from a panel and work to transform opinion into a consensus. Delphi processes are inherently variable in their application depending on the specific goals, but share a common process.15 Key steps in planning include statement of the problem, identification of experts to provide feedback, and transparency of the goals of the process among experts. From this point, discovery of opinions can proceed, with each round striving toward ultimate consensus. For this study, the goal was to establish consensus on a list of potential educational objectives for a model global health course. After the publication of the GPE SIG white paper on the CAPE educational outcomes, the group was motivated to use a systematic process that could provide more formalized guidance on educational objectives relevant to global health.9 Accordingly, the authors pursued this goal through conceptualization of this study with input from SIG members. The study was approved by investigator institutional review boards as exempt.

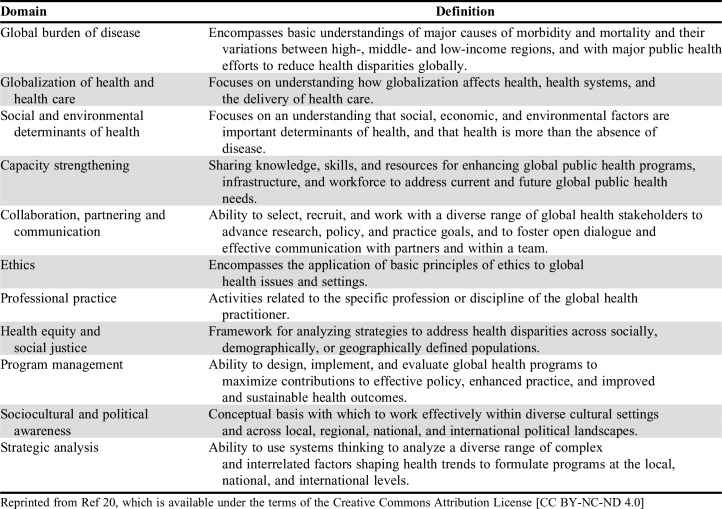

The initial stage of the study involved a compilation of potential objectives on which to structure informational flow through the Delphi, through formal and informal methods. A literature search was conducted on four pharmacy education-related journals: the American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, Pharmacy Education, and Pharmacy.16-19 Each journal was queried using the search terms “global health” and “medical mission” to identify potential publications of interest. Course objectives/competencies were extracted from the relevant literature. In addition, faculty members from the Public Health and GPE SIGs of AACP were informally asked to contribute course objectives/competencies from their own internal resources (such as syllabi), when available. This was done to add contributions of objectives relevant to pharmacy that may not have been formally published in the literature. A full list of objectives was assembled from formal and informal collection methods. The list was organized using an 11-domain structure, adapted from one of the relevant identified publications by Jogerst and colleagues.20 This publication was selected for the organizational structure because it provided guidance on global health competencies for an interprofessional audience endorsed by the Consortium of Universities for Global Health (CUGH) (Appendix 1).21 The authors worked together via consensus to determine the most appropriate domain for each objective, as well as to consolidate duplicates among collected objectives. A final organized list free of duplicates was created for utilization in the modified Delphi process.

Potential stakeholders who could serve as panel members for the process were identified using SIG membership listservs obtained from AACP. Members of three SIGs were identified for participation based on their relationship to the topic area: Public Health, GPE, and Health Disparities and Cultural Competence. This resulted in an initial email list of 703 individuals for panel invitation. Three rounds were conducted in August, September, and October 2016. Each round contained an initial offer for participation, with reminders sent one and two weeks later. The rounds were delivered via email using Qualtrics (Provo, UT).

Each round contained a description of the goals and consent for participation, followed by instructions and a standardized definition of global health. The first section of each questionnaire queried selected demographic information, including type of school/college of pharmacy, years in academic pharmacy, and type of current involvement in global health education. Objectives were organized into their assigned domains and assessed using 5-point Likert scale indicating strength of importance for each objective (5=extremely important, 4=very important, 3=moderately important, 2=slightly important, and 1=not at all important). For the first two rounds, respondents were given an opportunity to suggest changes to current objectives or new objectives within each domain for inclusion.

For the first round, objectives that were cumulatively rated as either “extremely important” or “very important” by at least 75% of respondents were moved forward to the next round. For the second round, the threshold was increased to 80%. For the final round, the threshold for final acceptance was set at 85%, defined as “consensus.” There are no validated levels of consensus used for Delphi processes; accordingly, the investigators chose these thresholds to reflect high levels of agreement, while still allowing for some variability among the diverse opinions collected. For the first two rounds, any suggested revisions to accepted objectives were incorporated into the next round. Objectives that failed to move forward but had suggested revisions also were revised and moved forward to the next round. New objectives were added to appropriate domains when suggested, for testing in the next round. For new or revised objectives, the authors worked toward mutual agreement to filter all suggestions appropriately to the next round. Objectives that failed to meet the criteria to move forward and were not subject to any suggested revisions were discarded.

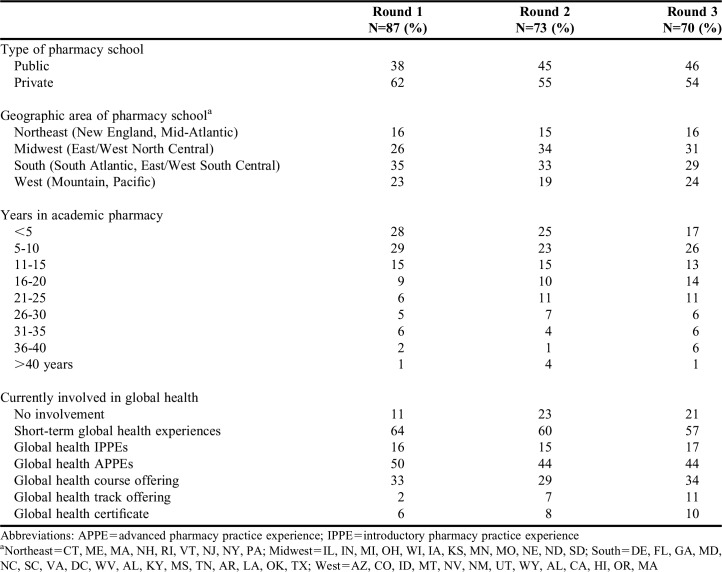

RESULTS

Characteristics of faculty members participating in the panel process are shown in Table 1. Overall, across the three rounds, representation of faculty from private schools ranged from 54% to 61%, slightly more than the proportion of private pharmacy programs nationally (72/139; 51.8%).22 All geographic regions of the country were represented, with the greatest participation from schools in the Midwest and the South. Respondents were also primarily early in their career, with a large proportion (42%-56%) with 10 or fewer years of experience teaching. Finally, the most common type of faculty experience in global health was through short-term global health experiences such as service/mission trips (57%-64%), with the next common exposure being through APPEs (43%-50%). Twenty-eight panel members participated across all three rounds.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Faculty Members Participating in Panels

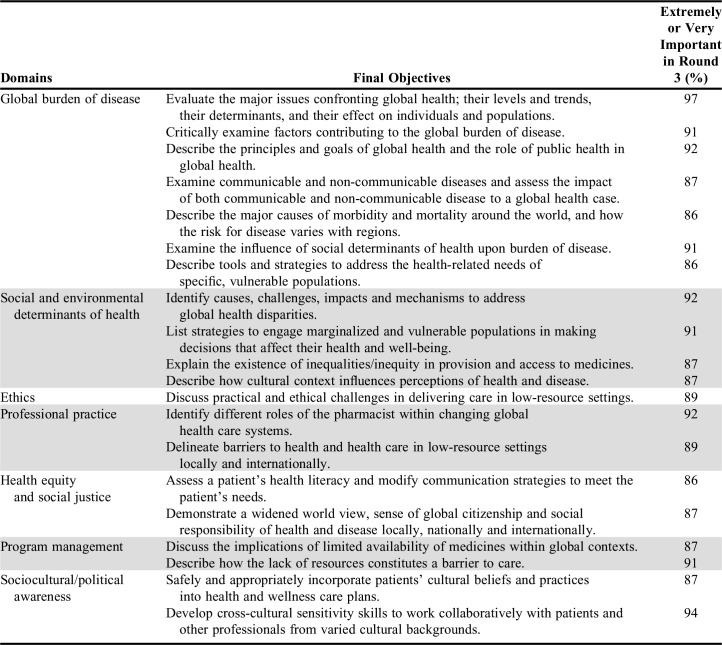

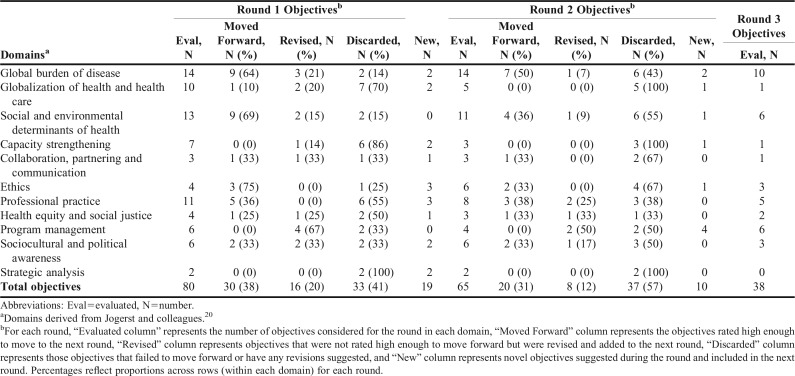

Literature review and informal collection of potential objectives resulted in 155 possible items. The list was refined to 80 objectives after categorization and duplicate removal. These 80 objectives were tested in the first round. This list was refined to 65 objectives (19% reduction) and 38 objectives (53% reduction) after the first and second rounds, respectively. Over the course of the first two rounds, 28 new objectives (18 in first round, 10 in second round) were suggested and subsequently tested (Appendix 2). After the second round, one domain (strategic analysis) no longer contained qualifying objectives. After the third round, four domains (globalization of health and health care; capacity strengthening; collaboration, partnering and communication; and strategic analysis) no longer contained objectives that met criteria for inclusion. Accordingly, the final accepted list (after the third round) consisted of 20 objectives from seven domains (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of Final Consensus Objectives After Round 3

DISCUSSION

The study used a modified Delphi process to identify 20 course objectives for a model global health course within a pharmacy curriculum. Compared to a typical survey questionnaire, which only solicits opinion from respondents, Delphi processes facilitate group transformation of opinion into a consensus through an iterative multistage design. Although they may not be widely known, Delphi processes have been used previously in pharmacy education and across other health professions to aid in curricular development.13,14,23-27 The process provides a level of flexibility, but has a general structure to aid the researcher in achieving successful results.28 It has been proposed as an ideal method for problem-solving, which incorporates feedback from individuals affected by the issue at hand, with use in educational settings demonstrated primarily for curricular planning and goal-setting.29

The final list of objectives contained seven out of the original 11 domains tested. Domains (and descriptions from Jogerst and colleagues20) with all objectives excluded were globalization of health/health care: “understanding how globalization affects health, health systems and the delivery of health care”; capacity strengthening: “sharing knowledge, skills, and resources for enhancing global public health programs, infrastructure, and workforce to address current and future global public health needs”; collaboration, partnering, and communication: “the ability to select, recruit, and work with a diverse range of global health stakeholders to advance research, policy, and practice goals, and to foster open dialogue and effective communication with partners and within a team”; and strategic analysis: “the ability to use systems thinking to analyze a diverse range of complex and interrelated factors shaping health trends to formulate programs at the local, national, and international levels.” Jogerst and colleagues proposed levels of interprofessional global health competency, ranging from skills needed for any student pursuing education with connection to global health, to those students planning significant and sustained engagement in the field.20 The four excluded domains included objectives largely defined within higher levels of this competency framework from a programmatic perspective. Because the experts were considering an introductory global health course, the complexity of these objectives may have contributed to their exclusion within the Delphi process.

Objectives identified under global burden of disease (“basic understandings of major causes of morbidity and mortality and their variations between high-, middle- and low-income regions, and with major public health efforts to reduce health disparities globally”) were the most populous at the beginning and end of the Delphi process, signalling their importance to this area of practice and education. These objectives discuss core knowledge areas that connect health and people across the globe, and logically serve as important foundational components in a global health curriculum. The highest rated objective within this domain (and overall) focuses on contemporary global issues and how they affect health and people on small and large scales. While this objective is considerably broad, it suggests an overarching theme of relevance for courses to consider.

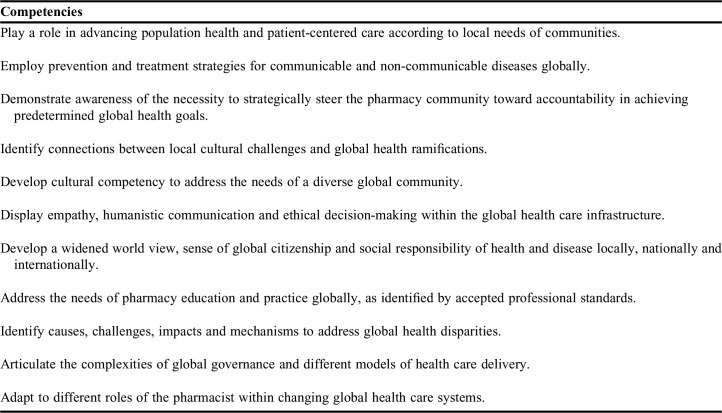

The CAPE report on global health education produced by the GPE SIG includes a list of student competencies achieved by informal consensus of the authors, through a non-systematic process (Appendix 3).9 These competencies provided input to the initial list of objectives in this study. It should be mentioned that there are pedagogical differences between objectives and competencies. Competencies represent broader skills that students should master, while objectives are the more specific abilities needed to accomplish those skills. However, post-Delphi, several bridges between the CAPE competencies and the final course objectives ascertained in this process were evident. Both include a need to examine communicable/non-communicable disease and the importance of cultural context in providing care. Both also recognize the importance of addressing disparities and developing a “widened world view” that contributes to development as a practitioner. These connections are important, as the similarities between the two suggest that the results of this process are widely applicable to the 2013 CAPE Educational Outcomes, which help to support inclusion into pharmacy curricula.30

The present process did not specify as a model global health course whether the emphasis would be on experiential or didactic education. Recent white papers published in AJPE from the GPE SIG have discussed best practices for setting up global/international APPEs, which provide invaluable guidance.31,32 However, global health educational offerings are diverse and extend beyond practice experiences, including standalone didactic courses, didactic structures used to prepare students for international travel, and interprofessional courses. Steeb and colleagues reported that approximately half of pharmacy institutions offered at least one didactic course in global health.33 With several resources available to consider in terms of frameworks, strategic direction, and wider vision statements, this study aimed to create a cohesive resource for curricular enhancement that could have flexibility in both didactic and experiential domains.34-36 However, many of the final accepted objectives might be best achieved in the didactic setting, or in an extended preparation phase for experiential work.

There are limitations to this study to consider. Delphi processes, while systematic, are variable and may have issues regarding the reliability of results, particularly when conducted in an electronic fashion.37 In many forms of this process, the same panel of stakeholders is used throughout all rounds. Therefore, the use of three separate and large panels may have introduced variability into the achievement of consensus results. The authors chose this variation in methodology to gather a broad and representative array of opinions that would be widely applicable across pharmacy schools, thus striving for enhanced external validity. The panel offers were made to more than 700 individuals, with participation ranging from 10% to 13%. If this were a response rate for a survey questionnaire, concerns for nonresponse bias would be paramount. However, participation of all of these individuals in a Delphi would not be feasible or expected. Additionally, larger panels may find consensus more difficult to achieve because of the diversity of opinions rendered. In this study’s Delphi, which included 70-80 individuals, consensus was achieved, indicating a strong agreement among objectives. Therefore, the authors believe that the study found an appropriate balance between internal and external validity. While generally a diverse sample of faculty members participated in the panels, some of their characteristics could also potentially bias their contributions. For instance, the sample consisted of mainly earlier career faculty members, which may lead them to contribute stronger preference for clinical objectives and lesser preference for objectives related to programmatic assessment and strategy. It should be noted that among those participating in the process, 10%-20% of individuals noted no current involvement in global health. They may have been engaged previously or in ways other than those queried by the investigators; however, it is possible that this group of individuals has less expertise on the topic and may have influenced the consensus results. However, the authors ultimately made the decision to include these individuals as their interest in the topic (regardless of current involvement) was thought to contribute a complementary opinion that would increase integration of these objectives with other areas of pharmacy education.

CONCLUSION

Overall, this modified Delphi process was able to successfully identify a list of consensus course objectives for a model global health course for pharmacy curricula. Ideally, the results of the study will guide pharmacy educators on course structure and outcomes in this area, and lead to standardization and improvement of global health education for pharmacists nationwide.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the leadership and members of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy’s Special Interest Groups (SIGs) of Public Health, Global Pharmacy Education, and Health Disparities and Cultural Competency for their intellectual contribution to this process.

Appendix 1. Definitions of Domains from Jogerst and Colleagues20

Appendix 2. Changes to Course Objectives in Each Round of the Modified Delphi Process, Stratified by Organizational Domain

Appendix 3. Global/International Pharmacy Education Student Competencies from Gleason and Colleagues9

REFERENCES

- 1.American Public Health Association. The role of the pharmacist in public health. http://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/07/13/05/the-role-of-the-pharmacist-in-public-health. Accessed January 31, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on the role of health-system pharmacists in public health. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(5):462–467. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strand MA, Miller DR. Pharmacy and public health: a pathway forward. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2014;54(2):193–197. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.13145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steeb DR, Joyner PU, Thakker DR. Exploring the role of the pharmacist in global health. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2014;54(5):552–555. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.13251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angelo LB, Maffeo CM. Local and global volunteer opportunities for pharmacists to contribute to public health. Int J Pharm Pract. 2011;19(3):206–213. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2011.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassali MA, Dawood OT, Al-Tamimi SK, Saleem F. Role of pharmacists in health based non-governmental organizations (NGO): prospects and future directions. Pharm Analyt Acta. 2016;7:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oji V, Weaver SB, Falade D, Fagbemi B. Emerging roles of U.S. pharmacists in global health and Africa. J Biosafety Health Educ. 2013;1:108. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, et al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1993–1995. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gleason SE, Covvey JR, Abrons JP, et al. Connecting global/international pharmacy education to the CAPE 2013 outcomes: a report from the Global Pharmacy Education Special Interest Group. https://www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/GPE_CAPE_Paper_November_2015.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2017.

- 10.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Standards 2016. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2017.

- 11.Bailey LC, DiPietro Mager NA. Global health education in doctor of pharmacy programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(4) doi: 10.5688/ajpe80471. Article 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Addo-Atuah J, Dutta A, Kovera C. A global health elective course in a PharmD curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(10) doi: 10.5688/ajpe7810187. Article 187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrne A, Boon H, Austin Z, Jurgens T, Raman-Wilms L. Core competencies in natural health products for Canadian pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(3) doi: 10.5688/aj740345. Article 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ceresia ML, Fasser CE, Rush JE, et al. The role and education of the veterinary pharmacist. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(1) doi: 10.5688/aj730116. Article 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.RAND Corporation. Delphi method. https://www.rand.org/topics/delphi-method.html. Accessed June 2, 2017.

- 16.American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. http://www.ajpe.org/ . Accessed January 31, 2017.

- 17.Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. http://www.journals.elsevier.com/currents-in-pharmacy-teaching-and-learning/ . Accessed January 31, 2017.

- 18.Pharmacy Education. http://pharmacyeducation.fip.org/pharmacyeducation . Accessed January 31, 2017.

- 19.Pharmacy. http://www.mdpi.com/journal/pharmacy . Accessed January 31, 2017.

- 20.Jogerst K, Callender B, Adams V, et al. Identifying interprofessional global health competencies for 21st-century health professionals. Ann Glob Health. 2015;81(2):239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Consortium of Universities for Global Health. About. https://www.cugh.org/about. Accessed January 31, 2017.

- 22.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Academic pharmacy’s vital statistics. https://www.aacp.org/article/academic-pharmacys-vital-statistics. Accessed January 31, 2017.

- 23.Penciner R, Langhan T, Lee R, McEwen J, Woods RA, Bandiera G. Using a Delphi process to establish consensus on emergency medicine clerkship competencies. Med Teach. 2011;33(6):e333–e339. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.575903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barton AJ, Armstrong G, Preheim G, Gelmon SB, Andrus LC. A national Delphi to determine developmental progression of quality and safety competencies in nursing education. Nurs Outlook. 2009;57(6):313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fried H, Leao AT. Using Delphi technique in a consensual curriculum for peridontics. J Dent Educ. 2007;71(11):1441–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walley T, Webb DJ. Developing a core curriculum in clinical pharmacology and therapeutics: a Delphi study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;44(2):167–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janke KK, Kelley KA, Sweet BV, Kuba SE. A modified Delphi process to define competencies for assessment leads supporting a doctor of pharmacy program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(10) doi: 10.5688/ajpe8010167. Article 167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green RA. The Delphi technique in educational research. SAGE Open. 2014:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 educational outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8) doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. Article 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dornblaser EK, Ratka A, Gleason SE, et al. Current practices in global/international Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences: preceptor and student considerations. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(3) doi: 10.5688/ajpe80339. Article 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alsharif NZ, Dakkuri A, Abrons JP, et al. Current practices in global/international Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences: home/host country or site/institution considerations. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(3) doi: 10.5688/ajpe80338. Article 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steeb DR, Overman RA, Sleath BL, Joyner PU. Global experiential and didactic education opportunities at US colleges and schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(1) doi: 10.5688/ajpe8017. Article 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruno A, Bates I, Brock T, Anderson C. Towards a global competency framework. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(3) doi: 10.5688/aj740356. Article 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Audus KL, Moreton JE, Normann SA, et al. Going global: the report of the 2009-2010 research and graduate affairs committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10) doi: 10.5688/aj7410s8. Article S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fincham JE. Global public health and the Academy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(1) doi: 10.5688/aj700114. Article 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donohoe H, Stellefson M, Tennant B. Advantages and limitations of the e-Delphi technique: implications for health education researchers. Am J Health Educ. 2012;43(1):38–46. [Google Scholar]