Abstract

Objective. To examine if personalized learning objectives influenced student engagement and if achievement of objectives could be measured from course assignments.

Methods. Learners created personalized learning objectives that correlated with their own goals within the context of the course. Using a mixed-methods analysis approach, the influence of these objectives on engagement and evidence of achievement of objectives were examined.

Results. Students reported a positive influence of personalized learning objectives on engagement. Additionally, measurement of student progression or achievement of objectives was possible from analysis of the course assignments.

Conclusion. Personalized learning is an important educational design for future pharmacists and health care professionals. Creating personalized learning objectives that build on centralized course objectives and connect to a broader context is one way to achieve the goal of an engaged and expanded learning experience.

Keywords: personalized learning, student engagement, online learning environment, writing intensive, health care system

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, personalized learning has received significant attention in higher education literature. Personalized learning has been used as part of the educational design for advanced pharmacy practice experiences.1 Apart from the pharmacy profession, the concept of personalized learning has been applied in continuing medical and nursing education.2-4 Mehta and colleagues compared curriculum-based and personalized learning paths provided to rheumatologists and found that physicians who completed the personalized learning training are more likely to improve their evidence-based choices.2 The nursing profession, facing severe personnel shortages and multiple paths into the profession, have begun relying on personalized learning academic technology to both attract more people into nursing and to prepare nurses for the lifelong adaptations required for competent practice.3,5

Personalized learning, or personalization, is also not a new concept for web-based learning and can be referred to as an individualized experience facilitating learners’ exploration and incorporation of past and current knowledge and interests.6,7 The desire for personalized learning is based on extensive social cognitive learning evidence that draws on theories of social constructivism (building on learners’ past experiences, “constructed” knowledge), intrinsic motivation (learners’ choices based on interest), and self-determination (need for competence and autonomy). These components strengthen the argument for deeper, more meaningful learning experiences with greater transfer and cognitive flexibility, which is especially important for future health care professionals and lifelong learning.

Outside of the traditional educational theory field is the work of Peter Senge in The Fifth Discipline that describes the traditional educational system of compliance indoctrination – teachers determine goals, and learners meet these goals by supplying teacher-designated “right” answers and largely completing what is asked of them.8 Senge argues that the habit of doing what one is told also has the consequence of separating learners from the big picture – loss of “intrinsic sense of connection to a larger whole.” Self-determination and motivation theory also provide compelling evidence that controlling environments are detrimental to intrinsic motivation and impede future intellectual exploration.9,10 While personalized learning lacks one accepted definition, for the purpose of this study, the authors used the position that personalized learning does not remove centralized learning goals or expectations, but rather allows students to create personalized learning goals explicitly linked to past and current learning experiences and future applications. Furthermore, students report on progress and provide evidence of progress in achieving their personalized learning objectives. In this study, students were asked to connect the learning experience to the “big picture” that Senge warns is often lost in traditional educational designs.

With the goal of fostering learner autonomy and personalization, this study incorporated an explicit personalized learning component in an online course based on issues in the US health care system with a primary focus to investigate two research questions as follows: What influence does writing personal learning objectives have on student engagement with course content? And using course assignments, is it possible to measure progression of achievement of student personal learning objectives?

METHODS

All materials in this study were derived from “Drugs and the U.S. Health Care System,” an elective online course offered to undergraduate, graduate, and pharmacy students at the University of Minnesota. The course focuses on the US health care system and controversial medication issues, such as drug development and advertising, addiction and abuse, health care reform, and end-of-life care. The purpose of the course is to prepare students to be informed, active leaders in ethics-driven debates surrounding the US health care system by creating evidence-based arguments to communicate ideas, engage others, articulate viewpoints, and develop a plan of action related to the content. Once enrolled, students are assigned to a small online discussion group containing seven to ten students. Students remain in the same small group throughout the semester. Each week, students are provided with brief online lectures and selected reading materials concerning the debate topic of the week. Students are asked to discuss and debate a controversial medical topic with their group members, using both a student group leader and a facilitating instructor. The overall goals of this course are to enable students to effectively convey their evidence-based viewpoints and potential solutions for the controversies in health care, and to engage in meaningful debate with others. A full description of this course is available elsewhere.11

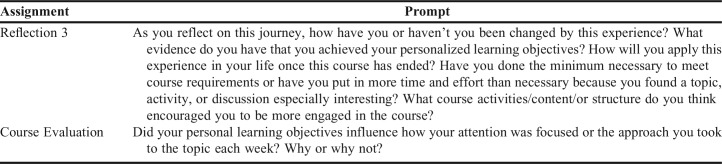

At the beginning of the course, all students are required to write two to three personal learning objectives to intentionally connect the learning experience in the course to their own educational and societal context. Unlike the course learning objectives, personal learning objectives are specific to individual students and their life goals. Course instructors provide feedback regarding the personalized learning objectives and ask students to resubmit the assignment if objectives are already addressed in the general course objectives. This course contains three main study sections. At the end of each section, students submit a reflection assignment to evaluate progress toward personalized goals. Each reflection assignment is one to two pages in length and contains a student's response to specific questions regarding their personalized learning journey. In the third and final reflection, students are asked to reflect on whether they have achieved their personal learning objectives and to provide evidence of achievement. Table 1 shows the writing prompt students are given for the final reflection.

Table 1.

Prompts for Reflection Assignments and Open-Ended Question in Course Evaluation

At the end of this course, all students were invited to voluntarily complete a course evaluation. The course evaluation was developed using the guidelines described by Gaddis and Dillman, Tortora, and Bowker.12,13 Following the initial development of the course evaluation, a pharmacy student took the two surveys using the “Think Aloud” approach, where an investigator sat with a student as she took the evaluation and described what she thought the evaluation was asking her, what she was thinking as she responded, and any difficulties she was having completing the evaluation.14 Based on these responses, the evaluation was revised. The survey was then piloted with five students not involved in the study, resulting in further modifications of the evaluation. The course evaluation was delivered via an email containing a hypertext link, which also ensured the anonymity of responses. Students were sent a single reminder notification to complete the survey. This link was also made available on the course website. Responses for the consent form and evaluations were all collected using Qualtrics (Provo, UT). The course evaluation consisted of 24 questions, 17 of which were close-ended questions, required by the university. The remaining seven questions on the course evaluation were added to specifically address potential redesign of the course. Of these seven, one was open-ended or contained an open-ended field for the student to supply additional comments. The prompt for the open-ended question concerning the personal learning objectives is included in Table 1.

Data sources used in this study were gathered from students who were enrolled in the “Drugs and the U.S. Health Care System” course in fall 2014, spring 2015, fall 2015, and spring 2016. This study included what Patton refers to as a “triangulation of data sources and analytical perspectives to increase the accuracy and credibility of finding.”15 Multiple sources of quantitative and qualitative data were collected for the purposes of increasing the breadth and depth of understanding of the research questions posed.15-17 The quantitative data source includes student-ranked course evaluation responses, while the qualitative data types consist of open-ended responses on the course evaluation, student submissions of the personal learning objectives and three reflection assignments, and a student focus group session.

Qualitative data analysis included content analysis using the Classic Analysis Strategy.18 Sources for analysis included open-ended course evaluation responses, personal learning objectives, and the final reflection assignment. Within themes, student comments and assignments were independently reviewed by two investigators, using the Classic Analysis Strategy, a constant comparison-like approach,18 and a comparison for internal consistency.

The focus group questions were developed using the guidelines described by Krueger and Casey.18 For the student focus group sessions, questions were developed to gather feedback related to the primary research question: did personally crafted learning objectives have any impact on engagement? While questions were developed, a semi-structured question methodology was used to allow for further examination of feedback not anticipated by the investigators. Sessions were scheduled for 90 minutes, recorded with a digital audio recorder, and occurred approximately two weeks following the end of the course; full transcripts of sessions were created. Although focus group sessions were part of the original plan, no students were successfully recruited to participate in focus group sessions related to the course experience despite several attempts. This study was deemed exempt by the University of Minnesota IRB.

RESULTS

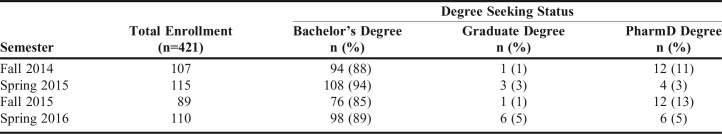

The learners in this course were undergraduate, graduate, and pharmacy students, although most students enrolled were upper-division undergraduate students. Enrollment numbers and a description of student learner type based on degree-seeking status are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographics of Students Who Enrolled in the “Drugs and the U.S. Health Care System” Course in Fall 2014, Spring 2015, Fall 2015, and Spring 2016

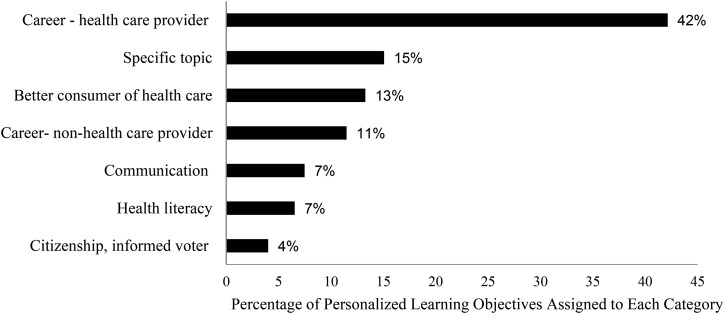

Students submitted 949 personal learning objectives over the four semesters included in the study. Emerging themes were categorized into seven categories: to become a better consumer of health care; to improve communication skills (either oral or written); to improve their personal health literacy or that of those around them (friends, family, campus, community, etc.); to become a more informed citizen or voter; to learn about a specific topic; to develop competencies or knowledge that they can apply to their future career in health care; and to develop competencies or knowledge that they can apply to their future career in a non-health care area. Figure 1 displays the number of personal learning objectives grouped into each category, expressed as a percentage of the whole. Appendix 1 includes examples of personal learning objectives from each category.

Figure 1.

Personal Learning Objectives Emerging Themes

Over the four semesters, 393 students out of 421 successfully completed the course and submitted a third reflection paper. Of these students, 86.5% agreed they had achieved their personal learning objectives. In addition, 5.6% of students stated they had achieved some of them, and 1.0% stated they had not achieved them. Of these 393 students, 6.9% did not address their personal learning objectives in their reflection or state whether they had achieved them.

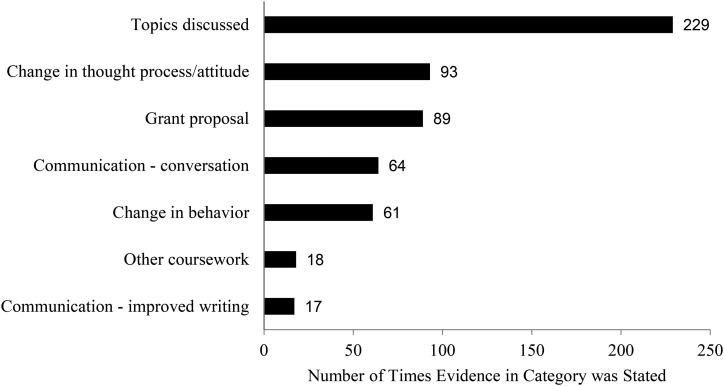

Students were also asked to provide evidence of achievement of their personal learning objectives. The evidence of achievement was divided into seven categories as follows.

Completion of their grant proposal assignment in the course.

The assignment had multiple components, but the final product was a Googlesite containing a mock grant proposal arguing and providing evidence for an idea or program of their creation.

Specific topics discussed in the course.

This included students who integrated information from multiple weeks into a cohesive viewpoint surrounding a topic.

Outside coursework performed for another course.

Examples include a student beginning to consider the practical implications of his research and asking to be involved in projects tied to drug development. Another student was able to contribute to a discussion in another class in greater depth, and another applied knowledge from the class to outreach projects in her student group on campus.

A specific conversation.

Examples include a conversation surrounding a topic in health care with a parent, a supervisor, or a peer. Students commented that they were able to discuss a topic in detail in which they previously had known little about. A few pharmacy students commented on specific conversations with patients, including a conversation after which the patient felt comfortable getting vaccines he was previously not planning to get.

An improvement in their writing skills.

Examples include improved research capabilities to provide evidence for viewpoints, understanding how to choose sources for their audience, and the ability to summarize information succinctly in a way their audience will understand.

A change in behavior.

Examples include students altering their behavior as a patient and asking more questions of their health care team, or playing a more active role in the doctor-patient relationship. Other students commented that they now visit medical news sites or read articles about health care in their spare time. One student gave evidence that she now does research on dietary supplements before taking them, and another discussed how she read through her parents’ health insurance plan options as they were renewing their health insurance. Multiple students discussed a change in career path, such as deciding to pursue a dual MD/MPH program or PharmD/MPH program, or changing to a nursing program.

A change in attitude or thought process.

Examples include a student commenting that he will continue to keep up with what is happening in the health care system after the course is over because he now realizes the huge role it plays in his life. Another student commented that she is no longer concerned about being unable to manage the requirements for written communication in her future career. One student commented that the numerous points of view she encountered in the class have made her much more open to the views of others, and another student shared that she now feels empowered to be a voice toward change in the health care system. Many students commented that, as future health care professionals, they will be mindful of their patients’ health literacy and focus on improved communication with their patients.

Figure 2 shows the number of times each category of evidence was specified in students’ third reflection papers. Note that students did not always give a separate piece of evidence for each personal learning objective, so the total number of pieces of evidence does not match the total number of personal learning objectives stated at the beginning of the semester.

Figure 2.

Evidence of Achievement of Personalized Learning Objective

On the course evaluation, 195 open-ended comments were submitted over four course offerings. Of those, 68% were positive regarding the impact of personalized learning objectives on the educational experience. Three themes emerged from the content analysis of the positive open-ended comments on the course evaluation, and all related to a connection between the course content and broader societal context, albeit in different ways. In the first theme, students stated that the personalized learning objectives and obligation to comment on progression in each of the section reflection papers resulted in a focus on their own academic and career goals as well as how the course content was relevant to them personally. In the second theme, students commented that the personal learning objectives helped make the “less exciting” course topics seem more interesting. They also reported that the more technical content was easier to understand and seemed more immediately useful. In the third theme, students stated the personalized learning objectives encouraged them to engage with their groupmates and groupmates’ individual interests and perspectives in ways they had not experienced in other group discussion settings.

The negative open-ended course evaluation comments were similar in theme and stated that the personalized learning objective component of the course did not have any significant influence. Most of the negative comments also noted that the personalized learning objectives submitted were too general to make a difference in engagement. Several students included suggestions for making personalized learning objectives more “personal,” such as allowing for revision of objectives as the course progressed and new goals emerged.

DISCUSSION

This study supports the positive effect of creating personalized learning objectives on learner engagement, as well as demonstrating that progression toward, or achievement of, personalized learning objectives can be measured through course assignments. Students reported a positive influence of personalized learning objectives on their sense of engagement. Additionally, measurement of student progression or achievement of personalized learning objectives was possible from analysis of the course assignments. Not all students reported a positive influence of the personalized learning objectives on engagement, but several made suggestions for how to improve the personalized learning objective component of the course. These suggestions include allowing for revision of personalized learning objectives at the point of the first reflection assignment to allow for changes in personal goals, as well as grading the personalized learning objective assignment to emphasize its importance (currently, personalized learning objectives are required but not assigned course points).

Student engagement was the primary focus of this study. Numerous research studies have emphasized student engagement as an important indicator of learning and academic success, including online learning environments.19-22 While engagement can be viewed as a multifaceted construct and measured on multiple levels, this study refers to student engagement as self-reported behavioral engagement (ie, effort and perseverance in learning).23,24 Self-reporting is considered to be the most common approach to assessing student engagement.21

Since a diverse set of previous experiences is a basis of current knowledge about the health care system, students’ specific experiences could affect their interest in health care and their learning goals. Understanding the US health care system is fairly challenging not only for undergraduate students, but also professional students pursuing a career in health care. Due to the complexity of the health care system, students likely have various past experiences involving the system, resulting in different attitudes toward career aspirations in health fields and different perceptions regarding health care sectors.25,26 For instance, Anderson and colleagues reveal that among most pharmacy students, the decision to pursue a Doctor of Pharmacy degree was influenced by prior work or volunteer experience in a health care setting.27 Past experiences also determine the expectation for receiving care and the rating of providers.28

A growing emphasis on the provision of health care-related courses has promoted health literacy and facilitated an understanding of the health care system among university students.29-31 Despite this, the use of personalized learning among these courses is sometimes overlooked. Promising research has shown that a personalized learning environment plays a critical role in improving students’ learning outcomes across different educational levels.32 It remains unclear, however, if personalized learning activities promoted in health care courses will yield a positive benefit in terms of student learning performance, especially student engagement, among undergraduate and professional students. Familiarity with the health care system, along with future career paths, stems from past experiences. Personalized learning allows students to create personalized learning objectives explicitly linked to past and current learning experiences and future applications, as well as reporting on progress and providing evidence of progress in achieving personalized learning objectives. This study demonstrates one way to incorporate personalized learning that is both successful and feasible.

CONCLUSION

Personalized learning is an important educational design for future pharmacists and health care professionals. Creating personalized learning objectives that build on centralized course objectives and connect to a broader context is one way in which students can achieve their goals and enrich their learning experience.

Appendix 1. Examples of Personal Learning Objectives from Each Category

Better consumer of health care

Example 1: As a first generation college student, I hope to improve my health/health literacy. I would like to learn how to be able to help my parents navigate through their insurance policies/needs and be aware of alternative health care options.

Example 2: As a member of society, I also interact and a confused by the health care system, especially with health insurance, so I am personally interested in learning more about different policies and plans.

Improve communication skills

Example 1: As a future scientist, I need to be able to write properly in order to clearly communicate my work to others. During this course, I would like to improve my scientific writing abilities and learn how to write to a specific audience.

Example 2: A fundamental component of this course is to gain practice in scientific writing and learn how to write a formal grant proposal. As a student researcher, I am keen on applying the writing skills I gain in this class toward the journal paper I will be composing this semester to summarize my research project summary and findings.

Improve health literacy

Example 1: I am hoping to gain knowledge and insight on health literacy to be able to recognize a patient that may need assistance so that I may create a safe place that encourages questions and encompasses compassion and understanding.

Citizenship/informed voter

Example 1: As a voter who is interested in health care, I would like to be better informed about drug policies so I can critically examine statements made by presidential candidates. I would like to understand what long-term/unintended impact various policy changes may have on the health care system. I would also like to know what areas in the health care system I would want to improve, so if I wanted to talk to lawmakers, I would have specific suggestions.

Example 2: As a citizen and consumer, I often feel that my opinions on health care issues are not valid because I do not actively educate myself about these topics. In this course I will focus on developing a strong foundation in health care issues so that I am able to make educated decisions as a voter and consumer.

Develop knowledge/competency for future career in health care

Example 1: I intend to serve as a physician, specifically a neurosurgeon, in the U.S. Armed Forces. I know that as a military physician, I will need to be familiar with not only the US health care system, but the structure and function of health care systems around the world. By taking this course, I hope to become more conversant with the impact of culture, environment, and economy on the delivery of health care so that I can provide the best quality medical care to my future patients no matter where I am stationed.

Example 2: As a physiology major with the goal of being a future physician, I feel like I lack the adequate amount of knowledge of our health care system. From the classes I have taken thus far in college, I’ve already learned so much about the science behind the medicine for my future career, but I have yet to learn about the health care system as a whole. Through this course I hope to be able to grasp an understanding of our health care system, so that I will be better prepared when I actually get involved in medicine.

Develop knowledge/competency for future career (non-health care)

Example 1: As an economics major, I hope to understand how the health care system affects the economy as a whole. During this course, I will be exploring how the buying and selling of pharmaceutical drugs reacts to the state of the economy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kelley KA, Beatty SJ, Legg JE, McAuley JW. A progress assessment to evaluate pharmacy students’ knowledge prior to beginning advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(4):Article 88. doi: 10.5688/aj720488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta N, Geissel K, Rhodes E, Salinas G. Comparative effectiveness in CME: evaluation of personalized and self-directed learning models. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(S1):S24–S26. doi: 10.1002/chp.21284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elsevier. Sherpath for nursing. https://evolve.elsevier.com/education/nursing/sherpath/?bcrumbs=1. Accessed July 6, 2017.

- 4.Morgan C. Northern Arizona University introduces personalized learning program to help nurses earn BSN degrees. http://dailynurse.com/tag/personalized-learning-program/. Accessed July 6, 2017.

- 5. Institute of Medicine. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed]

- 6.Waldeck JH. Answering the question: student perceptions of personalized education and the construct's relationship to learning outcomes. Commun Educ. 2007;56(4):409–432. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dvořáčková M, Kostolányová K. Complex model of e-learning evaluation focusing on adaptive instruction. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci. 2012;47:1068–1076. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Senge PM. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of The Learning Organization. New York, NY: Doubleday; 2006.

- 9. Deci EL, Ryan RM. The Handbook of Self-determination Research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 2004.

- 10. Elliot AJ, Dweck CS. Handbook of Competence and Motivation. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2005.

- 11.Pittenger AL, LimBybliw AL. Peer-led team learning in an online course on controversial medication issues and the US healthcare system. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(7):Article 150. doi: 10.5688/ajpe777150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaddis SE. How to design online surveys. Train Amp Dev. 1998;52(6):67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dillman D, Tortora R, Bowker D. Principles for constructing web surveys. Presented at the Joint Meetings of the American Statistical Association. Dallas, Texas; 1998.

- 14.Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(3):229–238. doi: 10.1023/a:1023254226592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2002.

- 16. Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2009.

- 17. Creswell JW. Mapping the developing landscape of mixed methods research. In: A. Tashakkori & C. B. Teddlie, eds. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2010:45-68.

- 18. Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2014.

- 19.Lee J, Shute VJ. Educ Psychol. 2010;45(3):185–202. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakker AB, Vergel AIS, Kuntze J. Student engagement and performance: a weekly diary study on the role of openness. Motiv Emot. 2014;39(1):49–62. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fredricks JA, Filsecker M, Lawson MA. Student engagement, context, and adjustment: addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learn Instr. 2016;43:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer KA. Student engagement in online learning: what works and why. ASHE High Educ Rep. 2014;40(6):1–114. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH.School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence Rev Educ Res 2004. Mar 174159–109. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee J-S. The relationship between student engagement and academic performance: is it a myth or reality? J Educ Res. 2014;107(3):177–185. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipsitz LA. Understanding health care as a complex system. J Am Med Assoc. 2012;308(3):243–244. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiersma ME, Plake KS, Newton GD, Mason HL. Factors affecting prepharmacy students' perceptions of the professional role of pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(9):Article 161. doi: 10.5688/aj7409161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson DC, Sheffield MC, Hill AM, Cobb HH. Influences on pharmacy students’ decision to pursue a doctor of pharmacy degree. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(2):Article 22. doi: 10.5688/aj720222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacStravic RS. Loyalty of hospital patients: a vital marketing objective. Health Care Manage Rev. 1987;12(2):23–30. doi: 10.1097/00004010-198701220-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith JA, Zsohar H. Teaching health literacy in the undergraduate curriculum: beyond traditional methods. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2011;32(1):48–50. doi: 10.5480/1536-5026-32.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez J, Phillips E, Fein O. Perspectives on the changing healthcare system: teaching systems-based practice to medical residents. Med Educ Online. 2013;18 doi: 10.3402/meo.v18i0.20746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mascarenhas AK, Atchison KA. Developing core dental public health competencies for predoctoral dental and dental hygiene students. J Public Health Dent. 2015;75(Suppl):S6–S11. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srisawasdi N, Panjaburee P. Technology-enhanced learning in science, technology, and mathematics education: results on supporting student learning. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci. 2014;116:946–950. [Google Scholar]