Abstract

Purpose

Knowledge about offenders and knowledge about victims has traditionally been undertaken without formal consideration of the overlap among the two. A small but growing research agenda has examined the extent of this overlap. At the same time, there has been a minimal amount of research regarding offending and victimization among minority youth, and this is most apparent with respect to Hispanics, who have been increasing in population in the United States.

Materials & Methods

This study explores the joint, longitudinal overlap between offending and victimization among a sample of Puerto Rican youth from the Bronx, New York.

Results

Results indicate: (1) an overlap between offending and victimization that persists over time, (2) a considerable overlap in the number, type, direction, and magnitude of the effect of individual, familial, peer, and contextual factors on both offending and victimization, (3) some of the factors related to offending were only relevant at baseline and not for the growth in offending but that several factors were associated with the growth in victimization, and (4) various risk factors could not explain much of the overlap between offending and victimization.

Conclusions

Theoretical, policy, and future research directions are addressed.

Introduction

Theoretical and empirical research on offending has generated an important amount of descriptive information about the nature and progression of delinquency and crime over the life course (Farrington, 2003). Though to a lesser degree, a similar strand of theoretical and empirical work has focused on the nature and correlates associated with victimization, but less so with respect to its progression over time (Miethe & Meier, 1994). Collectively, these investigations have made use of several criminological perspectives which while focused on one outcome or the other, also bear relevance for understanding both outcomes.

At the same time however, research on offending and victimization— as well as research on offenders and victims—has tended to proceed without consideration of the knowledge that has accumulated across both outcomes; that is, with a few exceptions (Higgins, Jennings, Tewksbury, & Gibson, 2009), much of the research has tended to concentrate only among offending and offenders or only among victimization and victims without acknowledging the shared overlap between the two (Gottfredson, 1981; Schreck et al., 2008). And while there is a growing knowledge base with respect to the overlap among offenders and victims (Broidy, Daday, Crandall, Klar, & Jost, 2005; Chen, 2009; Higgins et al., 2009; Loeber et al., 2005; Klevens et al. 2002; Schreck et al., 2008; Silver et al., 2010), the limited research that has been conducted on the overlap between offending and victimization has tended to focus on mainly normative samples of white youth, using a limited set of risk factors, and with limited attention to the longitudinal—especially within-person—patterning of offending and victimization (for a detailed review, see Lauritsen & Laub, 2007).

This study seeks to explore the victim-offender overlap generally, and the extent to which criminological risk factors from individual, familial, peer, and contextual domains help understand and explain the overlap between victimization and offending. Importantly, this study considers this issue via longitudinal data from a large sample of Puerto Rican youth residing in the Bronx, New York followed through the transition between childhood and adolescence. Two features of these data and our investigation are worth noting. First, these data provide important descriptive information regarding Hispanics’ offending and victimization, which is important because the empirical knowledge rests mainly on information from whites and African-Americans. Second, results gleaned from our effort will also bear relevance for the social sciences more generally especially because of the increased attention paid to Hispanics with respect to their population growth (U.S. Census, 2000), immigration and migration patterns (Martinez & Valenzuela, 2006; Pew Hispanic Center, 2009; Suro, 2005)—especially as the number of foreign born Hispanics grew from 21.1 million to 27.3 million between 2000 and 2007 (Pew Hispanic Center, 2009), and exposure to – and involvement in – the criminal justice system (Lopez & Livingstone, 2009). Consideration of the questions noted above with these particular data is important as it may provide further evidence regarding the generality of criminological perspectives for understanding offending and victimization across race/ethnic groups—with a concerted focus on the ever-increasing Hispanic population. Before we present an analysis of this issue, we outline the theoretical frameworks and requisite risk factors we consider for understanding offending, victimization, and their overlap, as well as a broad overview of the minimal literature on Hispanic offending and victimization.

Theoretical framework and prior research

A number of theoretical perspectives have implications for explaining the overlap in offending and victimization such as routine activities/lifestyles, social bonding, delinquent peers, subcultural, and self-control as well as neighborhood influences. Perhaps the most noted and commonly assessed of these perspectives is routine activities/lifestyles (Felson, 1986, 1992; Jensen & Brownfield, 1986; Mustaine & Tewksbury, 2000; Osgood et al., 1996; Sampson & Lauritsen, 1990; Schreck et al., 2008; Smith & Ecob, 2007; Taylor et al., 2008). This perspective emphasizes opportunity, exposure, and engagement in at-risk lifestyles and activities (e.g., drug and alcohol use, out of home recreation, and contact with potential offenders in unsupervised settings) that facilitate criminal events, and a number of empirical investigations have generated a common set of findings.

Several studies have documented that victims, offenders, and victim-offenders comprise distinct groups of individuals (Mustaine & Tewksbury, 2000). Along these lines, Klevens, Duque, and Clemencia (2002) demonstrated that individuals that were classified solely as victims tended to avoid risky lifestyle activities, but this was not the case for individuals who were identified as both victims and offenders. Similarly, Dobrin (2001) found that criminal offending increased an individual's risk for homicide victimization, and this risk was still apparent net of the effect of individual and neighborhood characteristics (see also Piquero et al., 2005). Broidy et al. (2005) also reported that homicide victims were often previously involved in criminal activity, yet there was still a subset of homicide victims that were noncriminals. In addition, Loeber et al. (2005) found that a number of child, family, school and demographic risk factors were related to violence and later involvement in homicide among boys in the Pittsburgh Youth Study.

Furthermore, Osgood and colleagues (1996) argue (from a routine activities perspective) that time spent with delinquent peers in the absence of adult supervision increases a youth's likelihood for crime and delinquency. As such and given the strong relationship between offending and victimization, spending large amounts of time in unstructured and unsupervised activities is likely to increase a youth's risk for experiencing victimization.1 Schreck et al. (2004) have found support for this linkage and have suggested that not only do criminal/ delinquent peers provide the context wherein the learning process takes place for offending, but that they are also not necessarily the peer group best suited for protecting a youth from victimization. In addition, Osgood et al. (1996) suggest that peers make delinquency more appealing because they can provide an opportunity for – as well as participate in – the act specifically (e.g., co-offenders). This assistance along with the tangible and intangible rewards that peers provide such as an increase in status or reputation serve to increase the probability that a youth will engage in delinquency and do so more frequently. This increased involvement in delinquency specifically places them at a greater risk of victimization (Felson, 1986, 1992; Jensen & Brownfield, 1986; Mustaine & Tewksbury, 2000; Osgood et al., 1996; Sampson & Lauritsen, 1990; Schreck et al., 2008; Smith & Ecob, 2007; Taylor et al., 2008). Therefore, routine activities/ lifestyles perspective is particularly relevant for explaining the victim-offender overlap because routine activities specifically and unstructured socializing more generally structures opportunities for both offending and victimization.

Additionally, other research has also demonstrated that child, family, peer, and environmental factors are important correlates of delinquency, including early aggression, poor family management, delinquent peer association, and drug availability (Chung et al., 2002; Hawkins et al., 1992; Loeber et al., 1998). Comparatively, concentrated poverty, racial heterogeneity, and family disruption have been identified as adverse conditions that are disproportionately observed in urban and disadvantaged neighborhoods (Coulton et al., 1995), which are also the neighborhoods where minorities, including Hispanics, tend to disproportionately reside. Several others studies have also demonstrated higher involvement in crime and delinquency among youth who reside in disadvantaged neighborhoods, and these youth also report elevated levels of exposure to violence and neighborhood problems (Elliott et al., 1996; McCord et al., 2001).

Delinquency among Hispanic youth

Although comparisons across race/ethnicity in delinquency and crime are rare because of data limitations, there is a small albeit growing knowledge base on Hispanics and delinquency (Morenoff, 2005). Early studies indicated that Hispanic youth display a pattern of offenses closer to that of Whites than of Blacks, while Hispanic adults display a pattern closer to that of Blacks than of Whites (Rodriguez et al., 1984). Chavez et al. (1994) provided evidence of the high levels of violence exhibited by Hispanic youth, a finding that has since been replicated for both male and female Hispanic youth (Jennings et al., 2009). Further, Cuellar and Curry (2007) reported that violent offending specifically was most frequently endorsed among a sample of Hispanic teenage females in El Paso. They also demonstrated that marijuana use emerged as the drug of choice, and nearly 10% of the Hispanic females reported heavy use of alcohol or cocaine or other inhalants.

Aside from the descriptive evidence regarding the nature of Hispanic delinquency and crime, researchers have also explored the factors associated with Hispanic offending. For example, Rodriguez and Weisburd (1991) presented ethnographic research highlighting the salience of family bonds as a protective factor for offending. Similarly, relying on a large sample of Puerto Rican males, Pabron (1998) reported that the frequency, duration, intensity, and the priority of the associations between the parent and the youth was particularly important for abstaining from delinquency. Other research has also noted the significance of family conflict and unsupervised socializing with peers as they relate to Hispanic youth and delinquency (Samaniego & Gonzales, 1999; Yin et al., 1999).

Pérez et al.‘s (2008) recent analysis of a large sample of Hispanic youth identified gender, physical abuse, academic problems, and prior criminal history as key correlates of self-reported violence. Their results also demonstrated the salience of ethnic-specific risk factors for violent delinquency, and these stressors were associated with acculturation processes. That is, Hispanic youth who reported experiencing intergenerational conflict with their parents over the importance of Hispanic values, customs, and way of life were more likely to report involvement in violence. Similarly, Hispanic youth who reported that they faced discrimination in the classroom also were more likely to report violence. Finally, Maldonado-Molina et al. (2009) examined the longitudinal relationship between several risk factors and delinquency, and observed that delinquent attitudes, delinquent peer association, and exposure to violence were significantly related to Hispanic offending.

Victimization among Hispanic youth

There have been a limited number of investigations surrounding Hispanic victimization generally, and among Hispanic youth in particular; yet, as the Hispanic population has increased in the last several decades, research has consistently shown that Hispanics are victimized at disproportionately high rates (Walker et al., 2007). For example, Crouch and colleagues (2000) found that Hispanic youth were victimized at higher rates compared to White youth regardless of income. Similarly, Fitzpatrick (1999) found that Hispanic high school students faced a significantly greater odds of being victimized compared to other racial groups. Intimate partner violence was also reported to be higher for Hispanic adults compared to Whites (Caetano et al., 2000; Cunradi et al., 2000; Field & Caetano, 2003).

Despite the consistency of the findings reviewed above regarding the disproportionate victimization rates of Hispanics, other research using more recent data suggests more similarities (or a lesser degree of disparity) between the rates of victimization among Hispanics compared to Whites and other ethnic groups. For instance, data from the mid-to-late 1990s indicated that there was no variation in the rates of childhood abuse for Hispanics compared to other races/ethnicities (Arroyo et al., 1997; Lau et al., 2003). Rennison (2002) showed that rates of violent victimization were disproportionately high in the early 1990s, yet these rates began to decline for Hispanics to the point where the differences in the victimization rates between Hispanics and non-Hispanics were marginal by 2000.

Thus, while the victimization rates appeared to be converging for Hispanics and non-Hispanics, additional research has since identified differences upon further dissection of the overall victimization rate. For example, relying on data collected from the National Crime and Victimization Survey (NCVS), Catalano (2004)found that non-Hispanics were more likely to be victims of rape and sexual assault. In contrast, Hispanics were more likely to be victims of aggravated assault and robbery (Catalano, 2006). Most of these finding have been recently replicated, particularly with regard to Hispanics’ disproportionate likelihood for experiencing robbery (Rand, 2009). In addition, Brown and Benedict's (2005) descriptive analysis of self-reported victimization from 230 Hispanic youth residing in an urban area suggested that Hispanic males reported more victimization than Hispanic females, and that the rate of victimization for the Hispanic youth was considerably higher than the national victimization rates of their non-Hispanic peers. In addition, Cuellar and Curry (2007) identified a high rate of physical and sexual abuse among Hispanic female adolescents. Thus, while Hispanic victimization research has revealed some inconsistencies, it is clear that Hispanics,and specifically Hispanic youth, are an at-risk ethnic group for victimization, just as the research reviewed earlier identified Hispanic youth as an at-risk group for delinquency.

Current study

The various theoretical frameworks reviewed above and the limited but emerging research examining delinquency and victimization among Hispanic youth suggest that there is likely to be a considerable degree of overlap between Hispanic victims and offenders. Also, there is likely to be a noticeable degree of shared similarity between how certain risk factor domains (e.g., individual, familial, peers, contextual) relate to both offending and victimization. Yet, these two observations have not been jointly and longitudinally linked among Hispanics. Acknowledging these possibilities, the current study explores the overlap between offending and victimization in a large, longitudinal sample of Puerto Rican youth residing in the Bronx, New York. Such an investigation is important considering that it will add not only to the body of research linking offending and victimization and its determinants, but will also add to the limited empirical knowledge regarding offending, victimization, and their overlap among Hispanics. A preliminary, descriptive analysis of these issues is especially warranted given that no comparable baseline exists in the criminological literature.2

Method

Data

Data for this study come from a sample of youth who participated in the Boricua Youth Study (BYS) (Bird et al., 2006a,b), a longitudinal study of Puerto Rican children and adolescents (initially aged 5 to 13 years). Three annual waves of child and parent-report data were collected between summer 2000 and fall 2004. A household was eligible if (1) there was at least one child residing in the household 5 through 13 years old and identified by the family as being of Puerto Rican background, and (2) at least one of the child's parents or primary caretakers residing in the household also self-identified as being of Puerto Rican background (Bird et al., 2006a). The sampling process yielded 1,414 eligible youth in Bronx, New York of which 1,138 were interviewed (completion rate=80.5%) (Bird et al., 2006a,b; Bird et al., 2007). Sample retention in the two yearly follow-ups was 89.4 percent at wave 2 and 85.6 percent at wave 3. Regarding survey administration, Bird et al. (2006a) reports that interviews were administered using laptop computers in the youth's home and were programmed in both English and Spanish. The use of a computerized protocol helped avoid missing data, inappropriate skips, and out-of-range codes. The interview audiotapes were also obtained for the purposes of quality control. Because missing data was less than 3–4%, mean replacement was used when data was missing for any of the measures used in the analysis. Overall, there were a roughly equivalent number of males and females in the sample (51.36% male). The average age of the Bronx youth was 9.51 (time 1). At baseline, 47.5% of children were ages 5 to 9 and 52.5% of children were older than 9 years. Table 1 provides summary statistics for all of the variables that were used in the analysis, and these variables are described below.

Table 1.

BYS sample descriptive statistics (n=1,138)

| Variables | M | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 0.52 | – | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Welfare | 0.46 | – | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Age (wave 1) | 9.51 | 2.57 | 5.00 | 15.00 |

| Sensation-Seeking | 3.63 | 2.52 | 0.00 | 10.00 |

| Peer Relationships | 4.00 | 1.19 | 0.00 | 5.00 |

| Peer Delinquency | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 2.00 |

| Parent-Child Relationships | 0.77 | – | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Coercive Discipline | 0.38 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 3.00 |

| Cultural Stress | 0.12 | – | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| School Environment | 3.30 | 3.04 | 0.00 | 14.00 |

| Offending (wave 1) | 0.83 | 1.61 | 0.00 | 17.00 |

| Offending (wave 2) | 0.60 | 1.36 | 0.00 | 14.00 |

| Offending (wave 3) | 0.54 | 1.52 | 0.00 | 23.00 |

| Victimization (wave 1) | 4.10 | 5.85 | 0.00 | 66.00 |

| Victimization (wave 2) | 3.35 | 5.35 | 0.00 | 55.00 |

| Victimization (wave 3) | 3.12 | 5.20 | 0.00 | 48.00 |

Dependent variables

Offending

This was an additive scale based on a common self-report delinquency measure and contained approximately 30 items (Elliott et al., 1985; see Appendix A). Each youth reported either “yes” or “no” to whether they participated in a number of delinquent acts in the prior year, and the number of “yes” responses were summed in order to create a delinquency variety scale (Hindelang et al., 1981). Example items include: “On purpose broken or damaged or destroyed something that did not belong to you?”; “Taken something from a store without paying for it?”; “Carried a hidden weapon?”; “Hit, slapped, or shoved other kids or gotten into a physical fight with them?”; “Skip school without an excuse?”; “Drunk any beer, wine, or any other liquor?”; “Smoked marijuana, weed, pot, or phillies (or blunts)?”; and “Attacked someone with a weapon or to seriously hurt or kill them?”

We recognize that the measures of delinquency differed by age group, yet we retained the delinquency scales as originally developed in the BYS for two reasons. First, we intended to remain as consistent as possible with other publications that have used the BYS delinquency scales, so that study findings regarding the scales could be considered and compared across studies. Second, recognizing the potential issues that could emerge with using different items in the delinquency scale, we undertook a supplemental analysis in which we investigated the prevalence of cases for which the different delinquency scales were used over time. Although fewer than one in five youth were administered the different scales across waves because their developmental age progressed out of the specified range (i.e., from ages 5 to 9 to age 10 and older), fewer than one percent of the sample had nonzero counts of delinquency across the three waves. Nevertheless, we removed these cases from the analysis and examined how or if the scales varied across the two samples. We found that the distribution of delinquency across waves and by site was virtually similar with or without these youth.3

Victimization

This measure was based on Richters and Martinez's (1993) exposure to community violence scale as modified by Raia (1995). Youth responded to a series of questions about whether they experienced violence themselves, saw violence happen to others, or heard about violence happening to someone they knew (see Appendix B). This measure was weighted such that if the violence happened to the youth (e.g., direct victimization) the response was coded as 3, if the youth saw the violence happen to others (e.g., indirect victimization) then the response was coded as a 2, and if the youth heard about the violence happening to someone they knew (e.g., indirect victimization) then the response was coded as a 1. Finally, each of the youth's weighted responses to a series of questions gauging exposure to a number of violent events was summed in order to create the weighted victimization scale, where higher values represented greater victimization.4

Independent variables

Individual factors

An individual factor measuring sensation-seeking was included, and was comprised of ten items that assessed the level of the youth's preference for thrill- and adventuring-seeking behavior (α = 0.72) (Russo et al., 1991,1993; Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990). This measure was coded such that higher values indicated the youth's greater preference for thrill- and adventure-seeking behaviors. A second individual ethnic-specific factor was included measuring cultural stress. This measure was comprised of thirteen items derived from the Hispanic Stress Inventory (Cervantes et al., 1990), and the scale reflected different aspects of stress that Hispanics experience with a particular focus on acculturation (α = 0.78). This measure was coded such that higher values indicated youth's experiencing a greater degree of cultural stress (Maldonado-Molina et al., 2009; Pérez et al., 2008). Three demographic variables were also included as individual factors. Sex was a dichotomous variable (1 = male, 0 = female). Age was a continuous measure representing the youth's age at the time of their wave 1 interview. The third demographic measure indicated whether the youth's family was on welfare or receiving some type of public assistance other than social security. Families on welfare or receiving public assistance were coded as 1, and those families not on welfare or receiving public assistance were coded as 0.

Familial factors

A continuous measure was included to assess the quality of the parent-child relationship, and was based on the summation of twelve items, with a representative item being “How often do your parents/ caretakers do things with you?” (α=0.75) (Farrington & Welsh, 2007; Loeber et al., 1998). Higher values indicated that the youth had a greater sense of the quality of the parent-child interactions (or positive parent-child interactions). A second parenting measure was a 6-item scale reflecting the extent of the parent's use of coercive disciplining techniques such as ignoring or acting cold toward the youth when they did something wrong or yelling or swearing at the youth when they did something wrong (α=0.67) (Farrington & Welsh, 2007; Goodman et al., 1998). Higher values indicated the parent's greater use of coercive disciplining techniques.

Peer factors

Two continuous measures were included as peer factors, one measuring the quality of the youth's relationship with their peers and the other assessing the proportion of the youth's peers that were engaged in delinquency (Akers, 1998; Akers & Sellers, 2009). The peer relationships factor was comprised of five items representing the youth's sense of belonging, feeling liked, and getting along well with others (α=0.58) (Hudson, 1992). Higher values indicated a greater sense of belonging and experiencing positive peer relationships. The peer delinquency scale reflected the number of the youth's peers that were engaged in a series of delinquent acts, where the response options ranged from 0=none of them, 1=only a few of them, 2=about half of them, to 3=most of them (α=0.85) (Loeber et al., 1998). Higher values represented the youth reporting having a greater proportion of delinquent peers.

Contextual factors

One continuous measure was included as a contextual factor that gauged the quality of the school environment. This 8-item scale assessed the negative characteristics of the school where the youth attended such as whether kids at school were involved in gangs, whether there were fist fights at school, or shootings, knifings, or razor blade attacks at school (α=0.55). Higher values represented a poorer or more negative school environment.

Analytic strategy

Prior to the multivariate analysis, we present a series of bivariate crosstabulations examining the association between victimization and offending at each wave in order to illustrate the prevalence of the victim-offender overlap and how this overlap persists over time. Following these bivariate comparisons, structural equation modeling in Mplus (version 5.2; Muthén & Muthén, 2008) was used to examine baseline predictors of the (change in the) frequency of offending and victimization over time. These multivariate analyses proceeded through two phases. First, latent growth models were fit to determine the functional form of the trajectories of offending and victimization independently. The latent intercept and slopes were allowed to co-vary and a Poisson distribution was specified. Once the form of these trajectories was determined, they were modeled simultaneously to obtain the unadjusted estimate of the correlation between the latent intercepts and slopes for each behavior. These unadjusted estimates indicated the initial overlap between baseline offending and victimization, as well as their growth over time.

Second, we tested the structural model relating the baseline individual, familial, peer, and contextual factors to the latent intercept and slopes representing the trajectories of offending and victimization. The structural model was built in steps. First, bivariate relations were modeled between the outcomes and each individual, familial, peer, and contextual factor. Second, the variables/factors with significant bivariate associations were added to the structural model one at a time. Non-significant paths (p > .05) were excluded in each step. Fit of the structural models was assessed with a likelihood ratio difference test comparing nested models, where two times the difference in log likelihoods is asymptotically chi-square with degrees of freedom equal to the difference in degrees of freedom between the two models. A statistically significant likelihood ratio chi-square suggests that the null hypothesis in favor of the reduced model should be rejected (Muthén & Muthén, 2004). Given the distribution of the outcome variables (i.e., Poisson), traditional goodness-of-fit indices, such as the CFI, RMSEA and SRMSR, were not calculable for these models. All parameters in each analysis phase were estimated with maximum likelihood estimation.

Results

As shown in Table 2, a crosstabulation of the prevalence of the victim-offender overlap indicates a statistically significant association between victimization and offending and this association is observed at waves 1 (χ2 = 63.95,p<.001),2 (χ2 = 36.93,p<.001),and 3 (χ2 = 40.95, p<.001). Several additional details are worth noting. First, the prevalence of being both a non-victim and a non-offender is fairly stable over time, representing roughly one-third of the sample. Second, the prevalence of victim-only is sizeable, ranging from 32.4% to 43.8% of the sample. Third, and in contrast to the victim-only group, the prevalence of offender-only is quite low and is actually the least prevalent group (ranging from 4.3% to 9.1%). Combined, this indicates that the substantial majority of youth who reported offending are also reporting victimization, e.g., they are victim-offenders. Specifically, 27.4% of the youth are victim-offenders at wave 1,18.2% at wave 2, and 15.3% at wave 3.

Table 2.

Prevalence of the victim-offender overlap (n=1,138)

| Time | Non-Victims and Non-Offenders |

Victims Only |

Offenders Only |

Victim- Offenders |

χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | 354 (31.1%) | 369 (32.4%) | 103 (9.1%) | 312 (27.4%) | 63.95*** |

| Wave 2 | 404 (35.5%) | 452 (39.7%) | 75 (6.6%) | 207 (18.2%) | 36.93*** |

| Wave 3 | 416 (36.6%) | 499 (43.8%) | 49 (4.3%) | 174 (15.3%) | 40.95*** |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

In addition, 4.3% of the youth were victim-offenders at all three waves, suggesting that there are a very small proportion of “chronic” victim-offenders and this prevalence closely mirrors the prevalence of chronic offenders that have been identified in criminal career research (Piquero et al., 2003, 2007). This small group of chronic victim-offenders displayed significantly higher levels of risk for nearly all of the individual, familial, peer, and contextual factors and a significantly greater frequency of offending and victimization across all three waves. Specifically, they were more likely to be male (χ2 =4.98, p<.05), older (t =4.74, p<.001), reported a greater preference for thrill and adventure-seeking activity (t=6.71, p<.001), had a greater number of delinquent peers (t=1.96, p = .05), reported their parents’ greater use of coercive disciplining techniques (t=1.65, p = .10), and attended more negative school environments (t=2.43, p<.05). Regarding their frequency of victimization and offending, the chronic victim-offenders reported offending nearly six times as frequently (wave 1: t=6.43, p<.001; wave 2: t=6.67, p<.001; wave 3: t=5.15, p<.001) and being victimized more than three times as frequently compared to those who were not chronic victim-offenders (wave 1: t=7.04, p<.001; wave 2: t=7.44, p<.001; wave 3: t=5.72, p<.001).

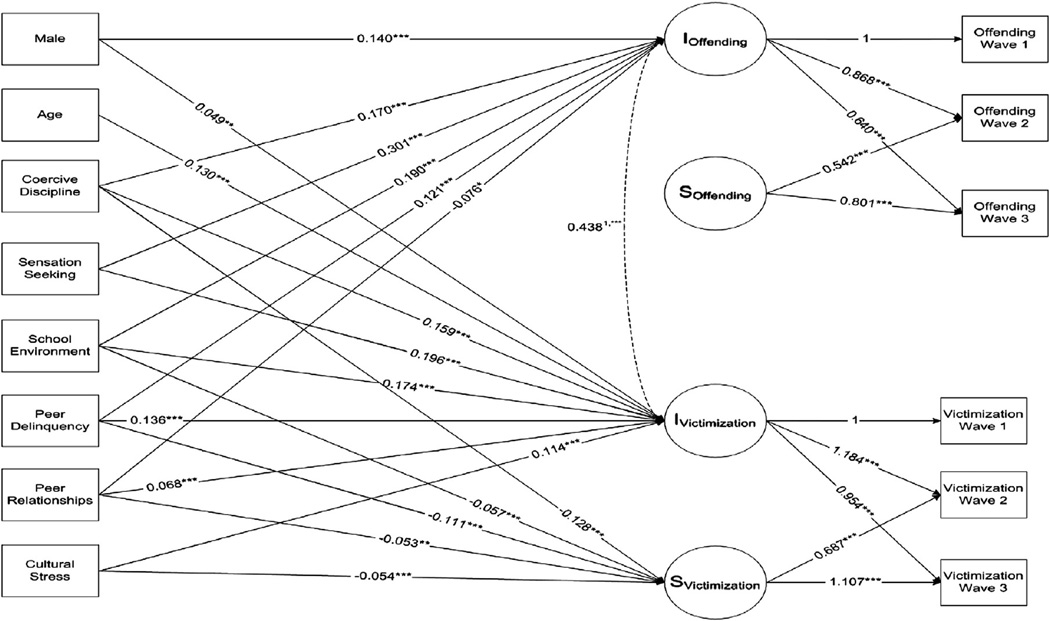

Following the bivariate victim-offender overlap comparisons described above, the structural equation results indicated that the growth in victimization and offending were best represented with latent intercept and linear slope terms. Tests for quadratic terms were not significant. Regarding the victimization-offending overlap, the standardized unadjusted correlation between the growth in victimization and offending was 0.409 (SE=0.07, p<0.001) and the unadjusted correlation in the intercept terms was 0.538 (SE=0.04, p<0.001). Substantively, this suggests that the intercept and slope terms had a moderate to strong relationship with respect to offending and victimization. All of the baseline individual, familial, peer, and contextual factors showed significant bivariate associations with the growth in victimization and offending. Thus, all of these factors were considered for inclusion in the final structural model. However, welfare status and the quality of the parent-child relationship were not significantly related to either the intercepts or slopes of victimization or offending when considered with the other factors, and were excluded from the final model. The final structural model is depicted in Fig. 1. The likelihood ratio chi-square test for this model was significant (χ2 (32)=408.10, p<0.001), indicating that it fit the data better than the unadjusted model of the trajectories of victimization and offending alone.

Fig. 1.

Structural model depicting standardized paths among individual, familial, peer, and contextual factors and the trajectories of offending and victimization.

With regard to the individual factors and their relationships with offending, gender (β=0.140, p<0.001) and sensation seeking (β=0.301, p<0.001) were positively and significantly associated with offending at time 1 (the intercept) indicating that being male and having a preference for thrill and adventure-seeking behaviors were related to self-reported offending frequency at baseline. The familial factor of coercive discipline (β=0.170, p<0.001) was also positively and significantly related to offending at baseline: youth who reported their parent's use of coercive disciplining techniques self-reported more offending. Both peer delinquency (β=0.121, p<0.001) and peer relationships (β=−0.076, p<0.050) were significantly related to baseline offending; however the direction of the effects were different. Youth who reported having more delinquent peers self-reported more offending, whereas youth who reported having more positive peer relationships (e.g., social support) self-reported less offending. Finally, the contextual factor of negative school environment (β=0.190, p<0.001) was positively and significantly associated with baseline offending, suggesting that youth who were attending a school with a more negative environment self-reported more offending. In contrast, the growth in offending was not significantly associated with any of the baseline individual, familial, peer, or contextual factors when estimated simultaneously in the structural model.

Turning toward the individual factors and their relationships with victimization, gender (β=0.049, p<0.010), age (β=0.130, p<0.001), sensation seeking (β= 0.196, p<0.001), and cultural stress (β=0.114, p<0.001) were all positively and significantly related to victimization at baseline (the intercept). Males, older youth, youth who had a preference for thrill and adventure-seeking activities, and youth who reported experiencing higher levels of cultural stress self-reported more victimization. The familial factor of coercive discipline (β=0.159, p<0.001) was also positively and significantly associated with victimization at baseline, suggesting that youth who reported that their parents used coercive disciplining techniques also self-reported a greater frequency of victimization. Finally, both peer factors and the contextual factors were positively and significantly associated with self-reported victimization at baseline. Specifically, youth who reported more delinquent peers (β=0.136, p<0.001), more positive peer relationships (β=0.068, p<0.001), and attending a school with a more negative environment (β=0.174, p<0.001) self- reported more victimization. Also, cultural stress (β=−0.054, p< 0.001), coercive discipline (β=−0.128, p<0.001), peer delinquency (β=−0.111, p<0.001), peer relationships (β=−0.053, p<0.010), and attending a school with a negative environment (β=−0.057, p<0.001) all showed significant inverse associations with the trajectory of self-reported victimization (the slope).

Ultimately, there was a considerable degree of overlap in the number, type, and the direction and magnitude of the effect of the individual, familial, peer, and contextual factors on both offending and victimization. For instance, the individual factors of gender and sensation seeking, the familial factor of coercive discipline, both peer measures (the proportion of the youth's peers involved in delinquency and the level of the youth's positive relationships with their peers), and the contextual factor of attending a negative school environment were all positively and significantly associated with offending and victimization at baseline (the intercepts) (with the exception of peer relationships which was significant for both outcomes, yet the direction of the effect for offending was negative and the direction of the effect for victimization was positive). Although none of the factors were significantly associated with the growth in offending (the slope), cultural stress, coercive discipline, peer delinquency, peer relationships, and attending a negative school environment were significantly associated with the growth in victimization (the slope).

Importantly and in addition to the risk/protective factor results, the findings indicate that when modeling these outcomes simultaneously and considering the significance of these shared risk factors, the final standardized adjusted correlation between the intercepts of offending and victimization at baseline was 0.438 (SE=0.02, p<0.001). Similarly, the standardized adjusted correlation between the growth (the slopes) in offending and victimization was 0.571 (SE=0.02, p<0.001). Thus, the victim-offender overlap is robust longitudinally and cannot be explained away by the shared similarity of a number of individual, familial, peer, and contextual factors.

Discussion

This study explored the victim-offender overlap among Hispanic youth, and incorporated a number of individual, familial, peer, and contextual risk factors that have been linked to both victimization and offending (Chung et al., 2002; Hawkins et al., 1992; Higgins et al., 2009; Loeber et al., 1998; Maldonado-Molina et al., 2009). Knowledge with respect to the overlap and factors associated with offending and victimization is important for both theory and policy, but this line of research has not been routinely examined largely because of the lack of longitudinal data on both offending and victimization among the same persons. Moreover, due to data limitations these issues have not yet been investigated among Hispanic youth, whose offending and victimization have been ill-studied in criminology. To provide information with respect to this issue and population, this study examined the link between offending and victimization in a longitudinal sample of Puerto Rican youth in the Bronx. Several key findings emerged from our study.

First, the bivariate crosstabulations illustrated that: (1) there is a rather stable group of youth (approximately one-third) that are not offending or being victimized, (2) the prevalence of victim-only youth is larger than that of offender-only youth, and (3) about 5% are chronic victim-offenders who report being both an offender and a victim across each of the three waves. Also, this victim-offender group exhibits significantly higher levels of risk across nearly all of the individual, familial, peer, and contextual factors and reports a significantly greater frequency of victimization and offending over time. Unexpectedly, the percent of youth who were victim-offenders decreased over time. At baseline, 27 percent of the respondents were victim-offenders, followed by 18 percent one year later, and 15 percent at the third measurement occasion. One might hypothesize that delinquency decreases over time, but perhaps not at such young age. It is also possible that the types of delinquent acts are not fully captured in the delinquency measures included in this study. Since few longitudinal studies have examined the overlap between victimization and offending, future studies should focus on examining the relation between both direct and indirect victimization and offending over time.

Second, the structural equation model analysis, which allowed us to simultaneously estimate the equations for both victimization and offending, uncovered a significant and substantively moderate/strong association between self-reported victimization and offending. A more fully specified structural equation model incorporating several individual, familial, peer, and contextual risk factors showed that while significant paths existed between the risk factors and both victimization and offending, these direct paths only marginally reduced (by 18%) the victim-offender overlap association. Consistent with other research investigating the victim-offender overlap, findings indicate that the nature and degree of the association between victimization and offending cannot be accounted for by the commonality or shared similarity between risk factors across a series of domains. One final observation is worth noting. Although risk factors were not significantly associated with the growth in offending (the slope), cultural stress, coercive discipline, peer delinquency, peer relationships, and attending a negative school environment were significantly associated with the growth in victimization (the slope). This highlights the importance of static risk factors for initial levels of – but not changes in – offending, while at the same time indicating that longitudinal changes in victimization are related to static risk factors. Thus, regardless of the shared overlap between offending and victimization, the manner in which baseline risk factors relates to the longitudinal patterning of these two outcomes appears to be different and may point to further consideration of the role of static and dynamic risk factors in the transition from childhood to adolescence.

Several limitations are important to acknowledge. First, although our results are similar to those examining the victim-offender overlap with normative but largely White youth, the BYS is comprised of only one ethnicity (Hispanics) and of only one Hispanic sub-group (e.g., Puerto Ricans), thus limiting ethnic-group comparisons as well as comparisons among Hispanics of different origins. However, the fact that our results are consistent with prior research using other samples of White and African American youth suggests that the victim-offender overlap is generalizable to Hispanics in general and Puerto Ricans specifically, with the understanding that Puerto Ricans are not necessarily representative of all Hispanics as there is a considerable degree of variability among Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Central Americans, Mexicans, Dominicans, etc. We encourage future research to attempt to unpack the variability that may exist within Hispanic populations with regard to the victim-offender overlap when data permit. Second, this study used self-report data collected from a large sample of Bronx youth; so, the extent to which these findings may apply to Puerto Ricans in different locations and contexts, or mirror those findings that may be discovered using official data with Hispanics remains open. Third, this study focused only on one developmental period of the life-course (late childhood/early adolescence), and future research should examine whether the degree or nature of the victim-offender overlap is observed in and/or persists into other developmental periods such as middle to late adolescence and young adulthood, especially when other forms of (domestic) offending and victimization emerge. Fourth, this study relied on static as opposed to dynamic risk factors. While most prior research has used static risk factors (Chung et al., 2002; Hawkins et al., 1992; Loeber et al., 1998), some research has suggested that life changes or turning points relate to changes in offending (Horney et al., 1995; Piquero et al., 2002). However, because most datasets focusing on life events contain information for young adults, extant studies typically focus on changes in marriage and employment. Thus, we can assume that these Hispanic youth who were an average of 9, 10, and 11 years old at wave 1, 2, and 3 would not have been subjected to these life changes or turning points, but still indicates that changes in life events among this age range (neighborhoods, schools, etc.) may be worth consideration with respect to their relation to offending and victimization. Additionally, by utilizing static risk factors we were able to determine that static risk factors do not appear to be related to the growth in offending, whereas some of these same factors appear to be related to both the baseline level and changes over time in victimization. Nevertheless, future research is encouraged to use both static and dynamic risk factors when data permits in order to investigate if they have similar or different effects on victimization and offending over time. Fifth, it is important to note that some of the scales had relatively low reliabilities. Although these measures were pre-tested at length and have been used in many other longitudinal delinquency studies and have also been previously published in other BYS studies, we acknowledge that the majority of these measures were tested and validated with predominantly white samples, and it may be the case that future research should make an effort to develop more culturally-relevant measures. Finally, while this study included several individual, familial, peer, and contextual risk factors that have been identified as salient for increasing victimization and offending risk, they only partially reduced the magnitude of the victim-offender overlap, suggesting that other risk factors and additional theoretical perspectives may be relevant.

The results from this study also have import for policy. For example, Karmen (2007) has indicated that victim assistance programs tend to serve populations that they consider to be the “most” deserving or “true” victims. As such, victim-offenders are often an overlooked client population as they are perceived to have some culpability in their victimization due to their offending involvement. Similarly, treatment and rehabilitation programs tend to focus only on offenders with the intention of reducing or curtailing their future offending, all the while incidentally ignoring their victimization experiences. The results from the current and other victim-offender overlap studies suggest that as programs and policies become more informed and cognizant that victims and offenders are often one in the same, then more comprehensive treatment regimens targeting the totality of the client's specific needs and issues are likely to be most effective. Our analysis also has implications for prevention and intervention efforts. Findings highlight the need to educate service workers that offenders and victims have a large degree of overlap and that treatment of one involves treatment of the other and that the overlap cannot be dismissed or neglected. Additionally, knowledge of the risk factors that we identified that were related to the growth in victimization (e.g., cultural stress, peer delinquency) is particularly important from an intervention perspective because it may help identify some areas where interventions may be able to make a small but salient impact on reducing a Hispanic youth's risk for future victimization.

Conclusion

This study has several implications for Hispanic research and policy. This study adds to the limited research examining offending among Hispanics, as well as contributing to the lack of research investigating victimization among Hispanics. Further, this study provides a unique contribution to the Hispanic offending and victimization literatures as there is currently no research that has assessed the victim-offender overlap among Hispanics. In sum, this study identified several individual, familial, peer, and contextual factors that were associated with the victim-offender overlap among Hispanics. We also identified a number of risk factors such as cultural stress, coercive discipline, peer delinquency, peer relationships, and attending a negative school environment that were significantly associated with the growth in victimization, but not the growth in offending. Moreover, it appears that extant theory has historically been situated in a position to explain both victimization and offending, yet the intersections of these processes and how they may inform theoretical discussions surrounding the victim-offender overlap seems less developed. We hope that this research has taken a step forward in this regard, and encourage future research to continue to examine the generalizabilty of the victim-offender overlap in order to further promote theorizing as well as providing evidence-based policy proscriptions.

Acknowledgement

The study was supported by NIMH grant RO-1 MH56401 (Dr. Bird, principal investigator), NIH grant 5P60 MD002261-02 (Dr. Canino, principal investigator) funded by the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities, and NIAAA grant K01-AA017480 (Dr. Maldonado-Molina, principal investigator). The authors would like to offer a sincere thanks to Hector Bird and also acknowledge the important contributions of Vivian Febo, Ph.D., Iris Irizarry, M.A., Linan Ma, MSPH, and of all of the dedicated staff who participated in this complex study.

Appendix A

Self-Reported Delinquency Scale - Items by Age Group. All items begin with “In the past year, have you…”

| Ages 5–9 | Ages 10 & Over |

|---|---|

|

|

Appendix B

Self-Reported Victimization Scale. All items begin with “In the past year, have you…1) personally experienced being; 2) seen someone you know being; and/or 3) heard about someone you know being”

|

Footnotes

Gottfredson and Hirschi's (1990) general theory provides another framework for explaining why individuals are involved in crime and delinquency and experience victimization. The underlying premise of the theory is that inadequate socialization in the family early in childhood leads to failure in developing adequate self-control which, in turn, increases a youth's risk for crime and delinquency when the opportunity arises. The link between low self-control and offending has been well documented (Gottfredson, 2006; Pratt & Cullen, 2000), and recent studies have also found an association between low self-control and victimization as well (Baron et al., 2007; Holtfreter et al., 2008; Piquero et al., 2005; Schreck, 1999; Schreck, Wright, & Miller, 2002). In addition, subcultural approaches have been linked to retaliatory behavior that invites opportunities for both offending and victimization (Anderson, 1999; Eitle & Turner, 2002; Jacobs & Wright, 2006; Kennedy & Baron, 1993; Singer, 1987; Stewart, Schreck, & Simons, 2006; also see Felson, 1992). Specifically, youth who are exposed to violence in their neighborhoods often display higher rates of involvement in violence (Eitle & Turner, 2002; Nofziger & Kurtz, 2005).

It is unknown the extent to which longitudinal patterns of offending and victimization will replicate among Hispanics because such an empirical analysis has not been conducted. Additionally, extant research has not explored how various risk factors operate among Hispanics with respect to the offender/victimization overlap. Thus, the current study is not only a replication of previous efforts investigating the longitudinal linkage between offending and victimization, but also an original investigation into the victim-offender overlap among Hispanic youth and the extent to which various risk factors relate to both outcomes and their joint occurrence.

It is important to note here that caution should be taken when interpreting the results because although a large number and range of items were included to measure delinquency, the descriptive statistics suggest that the offending measure was highly skewed. Nevertheless, we were aware of this skewness, and this is the reason that we estimated the SEM model using a Poisson distribution.

Some readers may observe that the victimization variable assumes a seriousness progression with direct experience being coded as highest and hearing about violence to someone they know as less serious. This is certainly debatable, because for some respondents it may be more traumatic to hear about particular violence than to personally experience it. Future research should further explore different methods of measuring personal and vicarious victimization. Furthermore, the frequency of victimization, like the offending frequency, was positively skewed with a relatively low prevalence. Specifically, not surprisingly, it was more common for the BYS participants to report experiencing indirect forms of victimization compared to reporting direct personal victimization. Having said this, there was a varying percentage of youth reporting personal victimization for each and every item included in the overall victimization measure (2–8%), followed by 7–23% reporting seeing this happen to someone else, and 9–16% reporting knowing it happen to someone but they were not there.

References

- Akers RL. Social learning and social structure: A general theory of crime and deviance. Boston: Northeastern University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Akers RL, Sellers CS. Criminological theories: Introduction, evaluation, and application. Fifth edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York, NY: W. W. Norton; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo JA, Simpson TL, Aragon AS. Childhood sexual abuse among Hispanic and non-Hispanic college women. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1997;19:57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Baron SW, Forde D, May FM. Self-control, risky lifestyles, and situation: The role of opportunity and context in the general theory. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2007;35:119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Canino GJ, Davies M, Duarte CS, Febo V, Ramirez R, et al. A study of disruptive behavior disorders in Puerto Rican youth: I. Background, design, and survey methods. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:1032–1040. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000227878.58027.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Davies M, Duarte C, Shen S, Loeber R, Canino GJ. A study of disruptive behavior disorders in Puerto Rican youth: II. Baseline prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates in two sites. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:1042–1053. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000227879.65651.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Shrout PE, Davies M, Canino G, Duarte CS, Shen S, et al. Longitudinal development of antisocial behaviors in young and early adolescent Puerto Rican children at two sites. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:5–14. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242243.23044.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broidy LM, Daday JK, Crandall CS, Klar DP, Jost P. Exploring demographic, structural, and behavioral overlap among homicide offenders and victims. Homicide Studies. 2005;10:155–180. [Google Scholar]

- Brown B, Benedict W. Student victimization in Hispanic high schools: A research note and methodological comment. Criminal Justice Studies. 2005;18:255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Cunradi CB, Schafer J, Clark CL. Intimate partner violence and drinking patterns among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the U.S. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;11:123–138. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S. Criminal Victimization 2003. U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics: Washington D.C.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S. Criminal Victimization 2005. U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics: Washington D.C.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Padilla AM, Snyder NS. Reliability and validity of the Hispanic Stress Inventory. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1990;12:76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez EL, Oetting ER, Swaim RC. Dropout and delinquency: Mexican American and Caucasian non-Hispanic youth. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1994;23:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. The link between juvenile offending and victimization: The influence of risky lifestyles, social bonding, and individual characteristics. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2009;7:119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Chung I, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Gilchrist LD, Nagin DS. Childhood predictors of offense trajectories. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2002;39:60–92. [Google Scholar]

- Coulton CJ, Korbin JE, Su M, Chow J. Community level factors and child maltreatment rates. Child Development. 1995;66:1262–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch JL, Hansan RF, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Resinick HS. Income, race/ethnicity, and exposure to violence in youth: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:625–641. [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar J, Curry TR. Prevalence and co-morbidity between delinquency, drug abuse, suicide attempts, physical and sexual abuse and self-mutilation among delinquent Hispanic females. Hispanic Journal of Behavior Sciences. 2007;29:68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Clark C, Schafer J. Neighborhood poverty as a predictor of intimate partner violence among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the United States: A multilevel analysis. Annals of Epidemiology. 2000;10:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrin A. The risk of offending on homicide victimization: A case control study. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2001;38:154–173. [Google Scholar]

- Eitle D, Turner RJ. Exposure to community violence and young adult crime: The effects of witnessing violence, traumatic victimization, and other stressful life events. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2002;39:214–237. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Ageton S. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D, Wilson WJ, Huizinga D, Sampson RJ, Elliott A, Rankin B. The effects of neighborhood disadvantage on adolescent development. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1996;34:389–426. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP. Developmental and life-course criminology: Key theoretical and empirical issues—the 2002 Sutherland Award Address. Criminology. 2003;41:221–225. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, Welsh BC. Saving children from a life of crime: Early risk factors and effective interventions. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Felson M. Linking criminal choices, routine activities, informal control, and criminal outcomes. In: Cornish DB, Clarke RV, editors. The reasoning criminal: Rational choice perspectives on offending. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986. pp. 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Felson RB. Kick ‘em when they're down: Explanations of the relationship between stress and interpersonal aggression and violence. The Sociological Quarterly. 1992;33:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Field CA, Caetano R. Longitudinal model predicting partner violence among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1451–1458. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000086066.70540.8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick KM. Violent victimization among America's school children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:1055–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Hoven CW, Narrow WE, Cohen P, Fielding B, Alegria M, et al. Measurement of risk for mental disorders and competence in a psychiatric epidemiologic community survey: The National Institute of Mental Health methods for the epidemiology of child and adolescent mental disorders (MECA) study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1998;33:162–173. doi: 10.1007/s001270050039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson MR. On the etiology of criminal victimization. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 1981;72:714–726. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson MR. The empirical status of control theory in criminology. In: Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevins KR, editors. Taking stock: The status of criminological theory. Volume 15. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 2006. pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T. A general theory of crime. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Morrison DM, O'Donnell J, Abbott R, Day LE. The Seattle Social Development Project: Effects of the first four years on protective factors and problem behaviors. In: McCord J, Tremblay RE, editors. Preventing adolescent antisocial behavior: Interventions from birth through adolescence. New York: Guilford Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GE, Jennings WG, Tewksbury R, Gibson CL. Exploring the link between low self-control and violent victimization trajectories in adolescents. Criminal Justice & Behavior. 2009;36:1070–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Hindelang MJ, Hirschi T, Weis JG. Measuring delinquency. Beverly Hills: California: Sage; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Holtfreter K, Reisig MD, Pratt TC. Routine activities, low self-control, and fraud victimization. Criminology. 2008;46:189–220. [Google Scholar]

- Horney J, Osgood DW, Marshall IH. Criminal careers in the short-term: Intra-individual variability in crime and its relation to local life circumstances. American Sociological Review. 1995;60:655–673. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson W. The Walmyr Assessment Scales Scoring Manual. Tempe, AZ: WALMYR; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs BA, Wright R. Street justice: Retaliation in the criminal underworld. Cambridge: New York, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings WG, Piquero NL, Gover AR, Pérez D. Gender and general strain theory: A replication and exploration of Broidy and Agnew's gender/strain hypothesis among a sample of Southwestern Mexican American Adolescents. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2009;37:404–417. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen GF, Brownfield D. Gender, lifestyles, and victimization: Beyond routine activity theory. Violence and Victims. 1986;1:85–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmen A. Crime victims: An introduction to victimology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy LW, Baron SW. Routine activities and a subculture of violence: A study of violence on the street. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1993;30:88–112. [Google Scholar]

- Klevens J, Duque LF, Clemencia R. The victim-offender overlap and routine activities: Results from a cross-sectional study in Bogota, Columbia. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17:206–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Garland AF, Hough RL, Landsverk J. Race/ethnicity and rates of self-reported maltreatment among high-risk youth in public sectors of care. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8:183–194. doi: 10.1177/1077559503254141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritsen JL, Laub JH. Understanding the link between victimization and offending: New reflections on an old idea. Crime Prevention Studies. 2007;22:55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB. Antisocial behavior and mental health problems: Explanatory factors in childhood and adolescence. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Pardini D, Homish L, Wei E, Crawford A, Farrington DP, et al. The prediction of violence and homicide in young men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:1074–1088. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MH, Livingstone G. Hispanics and the criminal justice system: Low confidence, high exposure. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Molina M, Piquero AR, Jennings WG, Bird H, Canino G. Trajectories of delinquency among Puerto Rican children and adolescents at two sites. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2009;46:144–181. doi: 10.1177/0022427808330866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez R, Valenzuela A, editors. Immigration and crime: Ethnicity, race, and violence. New York: New York University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McCord J, Widom CS, Crowell NA, editors. Juvenile crime, juvenile justice. Panel on juvenile crime: Prevention, treatment, and control. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Miethe TD, Meier RF. Crime and its social context: Toward an integrated theory of offenders, victims, and situations. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff JD. Racial and ethnic disparities in crime and delinquency in the United States. In: Tienda M, Rutter M, editors. Ethnicity and causal mechanisms. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 139–173. [Google Scholar]

- Mustaine EE, Tewksbury R. Comparing the lifestyles of victims, offenders, and victim-offenders: A routine activity theory assessment of similarities and differences for criminal incident participants. Sociological Focus. 2000;33:339–362. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén B. Mplus User's GuideM. Third Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén B. Mplus (Version 5.2) Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nofziger S, Kurtz D. Violent lives: A lifestyle model linking exposure to violence to juvenile violent offending. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2005;42:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, Wilson JK, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Routine activities and individual deviant behavior. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:635–655. [Google Scholar]

- Pabron E. Hispanic adolescent delinquency and the family: A discussion of sociocultural influences. Adolescence. 1998;33:941–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DM, Jennings WG, Gover AR. Specifying general strain theory: An ethnically relevant approach. Deviant Behavior. 2008;29:544–578. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Hispanic Center. Statistical portrait of Hispanics in the United States, 2007. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero AR, Brame R, Mazerolle P, Haapanen R. Crime in emerging adulthood. Criminology. 2002;40:137–169. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero AR, Farrington DP, Blumstein A. The criminal career paradigm: Background and recent developments. In: Tonry M, editor. Crime and justice: A review of research. Vol. 30. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press; 2003. pp. 359–506. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero AR, Farrington DP, Blumstein A. Key issues in criminal career research: New analyses of the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Cambridge University; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero AR, MacDonald JM, Dobrin A, Daigle L, Cullen FT. Studying the relationship between violent death and violent arrest. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2005;21:55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt TC, Cullen FT. The empirical status of Gottfredson and Hirschi's general theory of crime: A meta-analysis. Criminology. 2000;38:931–964. [Google Scholar]

- Raia JA. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Los Angeles: University of California; 1995. Perceived social support and coping as moderators of children's exposure to community violence. [Google Scholar]

- Rand MR. Criminal victimization, 2008. (Ncj 227777) Washington, DC: Department of Justice: Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rennison CM. Hispanic victims of violent crime, 1993–2000. (Ncj 191208) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice: Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Richters JE, Martinez P. The Nimh Community Violence Project: I. Children as victims of and witnesses to violence. Psychiatry. 1993;56:7–21. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez O, Burger W, Banks L. Crime rates among Hispanics, blacks, and whites in New York City. Hispanic Pew Research Bulletin. 1984;7:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez O, Weisburd D. The integrated social control model and ethnicity. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 1991;18:464–479. [Google Scholar]

- Russo MF, Lahey BB, Christ M, Frick PJ, McBurnett K, Walker JL, et al. Preliminary development of a sensation-seeking scale for children. Personality and Individual Differences. 1991;12:399–405. [Google Scholar]

- Russo MF, Stokes GS, Lahey BB, Christ M, McBurnett K, Loeber R, et al. A sensation seeking scale for children: Further refinement and psychometric development. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1993;15:69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Samaniego RY, Gonzales NA. Multiple mediators of the effects of acculturation status on delinquency for Mexican-American adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:189–210. doi: 10.1023/A:1022883601126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Lauritsen JL. Deviant lifestyles, proximity to crime, and the offender-victim link in personal violence. Journal of Research in Crime Delinquency. 1990;27:110–139. [Google Scholar]

- Schreck CJ. Criminal victimization and low self-control: An extension and test of a general theory of crime. Justice Quarterly. 1999;16:633–654. [Google Scholar]

- Schreck CJ, Fisher BS, Miller JM. The social context of violent victimization: A study of the delinquent peer effect. Justice Quarterly. 2004;21:23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Schreck CJ, Stewart EA, Osgood DW. A reappraisal of the overlap of violent offenders and victims. Criminology. 2008;46:871–906. [Google Scholar]

- Schreck CJ, Wright RA, Miller JM. A study of individual and situational antecedents of violent victimization. Justice Quarterly. 2002;19:159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Silver E, Piquero AR, Jennings WG, Piquero NL, Liebe M. Assessing the violent offending and violent victimization overlap among discharged psychiatric patients. Law & Human behavior. doi: 10.1007/s10979-009-9206-8. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer SI. Victims in a birth cohort. In: Wolfgang ME, Thornberry TP, Figlio RM, editors. From Boy to Man, From Delinquency to Crime. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1987. pp. 163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ, Ecob R. An investigation into causal links between victimization and offending in adolescents. British Journal of Sociology. 2007;58:633–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EA, Schreck C, Simons R. “I ain't gonna let no one disrespect me”: Does the code of the street reduce or increase violent victimization among African American adolescents? Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2006;43:427–458. [Google Scholar]

- Suro R. Attitudes toward immigrants and immigration policy: Surveys among Latinos in the U.S. And in Mexico. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor TJ, Freng A, Esbensen F, Peterson D. Youth gang membership and serious violent victimization: The importance of lifestyles and routine activities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1441–1464. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census US. Population projections of the United States, by age, sex, race, and Hispanic Origin: 1993 to 2050. Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Walker S, Spohn C, DeLone M. The color of justice: Race, ethnicity, and crime in America. 4 ed. New York: Wadsworth; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z, Katims DS, Zapata JT. Participation in leisure activities and involvement in delinquency by Mexican American adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1999;21:170–185. [Google Scholar]