Abstract

Circadian rhythms are driven by circadian oscillators, and these rhythms result in the biological phenomenon of 24-h oscillations. Previous studies suggest that learning and memory are affected by circadian rhythms. One of the genes responsible for generating the circadian rhythm is Rev-erbα. The REV-ERBα protein is a nuclear receptor that acts as a transcriptional repressor, and is a core component of the circadian clock. However, the role of REV-ERBα in neurophysiological processes in the hippocampus has not been characterized yet. In this study, we examined the time-dependent role of REV-ERBα in hippocampal synaptic plasticity using Rev-erbα KO mice. The KO mice lacking REV-ERBα displayed abnormal NMDAR-dependent synaptic potentiation (E-LTP) at CT12~CT14 (subjective night) when compared to their wild-type littermates. However, Rev-erbα KO mice exhibited normal E-LTP at CT0~CT2 (subjective day). We also found that the Rev-erbα KO mice had intact late LTP (L-LTP) at both subjective day and night. Taken together, these results provide evidence that REV-ERBα is critical for hippocampal E-LTP during the dark period.

Keywords: Circadian clock system, Circadian rhythm, Neuronal plasticity, Long-term potentiation

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Circadian rhythms are based on an internal timing system. The effects of circadian rhythms on learning and memory have been studied. Previous reports showed that mutations in genes responsible for generating circadian rhythms impair learning in several organisms, ranging from Drosophila [1] to mice [2,3] and humans [4]. In mammals, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus is known to be responsible for regulating circadian rhythms [5]. The RNA and protein levels of circadian oscillators are controlled by positive and negative transcriptional feedback loops in the SCN [6]. The SCN, acting as a master clock, coordinates the activity of various oscillators in the brain.

REV-ERBα, which is one of the clock-modulating proteins, represses the transcription of circadian oscillators. REV-ERBα expression rhythms occur at almost 180° out of phase in the SCN and the expression peaks at CT08~CT12 [6]. In addition, REV-ERBα influences the circadian period length but is not required for circadian rhythm generation [7]. According to Gerhart-Hines et al. [8], REV-ERBα controls temperature rhythms and thermogenic plasticity. Furthermore, REV-ERBα in the ventral midbrain drives the circadian oscillations in tyrosine hydroxylase expression, thereby regulating mood [9], and is required for food entrainment [10].

Recent studies have revealed the functions of REV-ERBα in the hippocampus. The expression level of REV-ERBα in the hippocampus shows oscillation that peaks at CT08~CT12 [11], and the lack of REV-ERBα leads to alterations in hippocampus-dependent behaviors [12]. The regulation of the circadian clock in the hippocampus by the REV-ERBα is performed through the interaction with oligophrenin-1, which regulates dendritic spine morphology [13]. However, the role of REV-ERBα in hippocampal synaptic plasticity has not been well characterized. The present study aimed to elucidate the relationship between REV-ERBα and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus through extracellular field recordings during subjective day and night.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Rev-erbα knock-out (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice were maintained in a C57BL/6J background. Mice were housed at a constant room temperature with free access to food and water. The circadian time 0~circadian time 2 (CT0~CT2) group was subjected to a normal 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, with lights switched on at 09:00. The CT12-14 group was subjected to a reversed 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, with lights switched on at 21:00. After entrainment for >14 days under a reversed light-dark photoperiod, mice were maintained under the same photoperiod. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Seoul National University.

Electrophysiology

For extracellular field recordings, transverse hippocampal slices (400-µm-thick) were prepared from brains of adult mice deeply anesthetized with isoflurane using a vibratome [14]. Hippocampal slices were incubated at 32℃ for 30 min and then maintained at 28℃ for at least 1 h before the experiment as described previously [15]. After recovery, the slices were placed in a recording chamber at 25℃, and perfused with oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing 124 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 25 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM glucose, 2 mM CaCl2, and 2 mM MgSO4 at a rate of 1 ml/min. Extracellular field EPSPs (fEPSPs) were recorded from the CA1 area using a glass electrode filled with ACSF (1 MΩ). The Schaffer collateral (SC) pathway was stimulated every 30 s using concentric bipolar electrodes (MCE-100; Kopf Instruments). For measuring LTP, the stimulation intensity was adjusted to produce a fEPSP slope that was approximately 40% of the maximum slope for that slice. All LTP experiments were performed after a stable baseline was recorded. Theta burst stimulation (TBS) protocols were used to induce E-LTP and L-LTP (five pulses of 100 Hz repeated five times at 5 Hz; 10-s inter-train interval for E-LTP and 10-min inter-train interval for L-LTP). Field potentials were amplified, low-pass filtered (GeneClamp 500; Axon Instruments), and then digitized (NI PCI-6221; National Instruments) for measurement. Data were monitored, analyzed online, and reanalyzed offline using the WinLTP program. Representative traces are an average of five consecutive responses and stimulus artifacts were blanked for clarity.

Statistics

Input-output curve and paired-pulse ratio data were analyzed using repeated-measures two-way ANOVA. LTP data (average of the last 5 min of recordings) were analyzed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test. All the data are represented as mean±SEM.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To determine whether REV-ERBα plays an important role in hippocampal synaptic plasticity, we characterized electrophysiological phenotypes in the Rev-erbα KO mice. We first measured synaptic transmissions at hippocampal Schaffer-collateral-CA1-pyramidal (SC-CA1) synapses. As the REV-ERBα expression shows oscillations, the extracellular field recordings were performed during subjective day (CT0~CT2) and subjective night (CT12~CT14).

During the subjective day (CT0~CT2), the input-output relationship was similar between the Rev-erbα KO mice and the WT littermates (Fig. 1A), which suggests that the lack of REV-ERBα expression does not influence basal transmission in SC-CA1 synapses. Furthermore, we performed paired-pulse ratio and confirmed that short-term plasticity is normal in Rev-erbα KO mice (Fig. 1B). To understand whether REV-ERBα influences NMDAR-dependent synaptic plasticity, we performed early long-term potentiation (E-LTP) with theta-burst stimulation (TBS). Loss of REV-ERBα expression did not cause any impairment in the E-LTP (Fig. 1C). Together, these results suggest that the genetic deletion of REV-ERBα does not affect basal synaptic transmission, short-term plasticity, and NMDAR-dependent synaptic plasticity in the hippocampal SC-CA1 pathway during the subjective day.

Fig. 1. Basic synaptic transmission and E-LTP are unaffected in Rev-erbα KO mice on the subjective day. (A) Input-output relationships at the hippocampal Schaffer-collateral-CA1-pyramidal (SC-CA1) synapses showed no significant difference between the WT and Rev-erbα KO mice (WT, 7 slices from 4 mice; Rev-erbα KO, 7 slices from 4 mice; repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, effect of genotype, F(1,12)=0.7524; p=0.9996). (B) The paired-pulse ratios showed no significant difference between the WT and KO mice. (WT, 6 slices from 4 mice; Rev-erbα KO, 7 slices from 4 mice; repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, effect of genotype, F(1,11)=0.4297; p=0.1009). (C) Example traces from baseline and LTP at times indicated by (a) and (b): WT (black) and KO (red). TBS-induced E-LTP was comparable between the WT and KO mice. (WT, 7 slices from 4 mice; Rev-erbα KO, 6 slices from 4 mice; average fEPSP slopes for the last 5 min; WT, 142.7%±8.039%; Rev-erbα KO, 137.7%±9.783%; unpaired t test, p=0.6970).

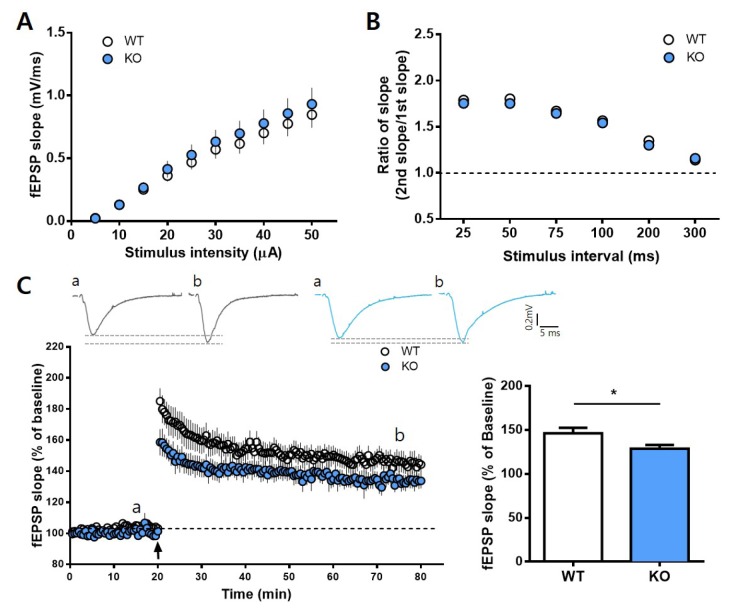

To further examine the association between REV-ERBα and hippocampal synaptic plasticity, we performed extracellular field recordings during the subjective night (CT12~CT14). In the Reverbα KO mice, both the input-output relationship and pairedpulse ratio were normal (Fig. 2A, B), indicating that the deletion of REV-ERBα does not influence basal transmission and short-term plasticity in SC-CA1 synapses. However, E-LTP appeared significantly impaired with a considerably lower potentiation magnitude (Fig. 2C). Therefore, these findings indicate that REV-ERBα has a time-dependent role in regulating the NMDAR-dependent synaptic plasticity.

Fig. 2. E-LTP is impaired in Rev-erbα KO mice during the subjective night. (A) The input-output relationships at SC-CA1 synapses showed no significant differences between WT and Rev-erbα KO mice at CT12~13. (WT, 12 slices from 7 mice; Rev-erbα KO, 12 slices from 7 mice; repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, effect of genotype, F(1,22)=0.5963; p=0.9631). (B) Paired-pulse ratios showed no significant differences between the WT and KO mice at CT12~13. (WT, 12 slices from 7 mice; Rev-erbα KO, 13 slices from 7 mice; repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, effect of genotype, F(1,22)=0.6569; p=0.7418). (C) Representative traces from baseline and LTP at times indicated by (a) and (b): WT (black) and KO (blue). TBS-induced E-LTP was significantly lower in the Rev-erbα KO mice (WT, 11 slices from 7 mice; Rev-erbα KO, 11 slices from 7 mice; average fEPSP slopes for the last 5 min; WT, 146.4%±6.073%; Rev-erbα KO, 128.7%±4.288%; unpaired t-test, p=0.0274). *p<0.05.

The next set of experiments were performed to determine whether L-LTP varies with the time of day in the Rev-erbα KO mice. L-LTP is a type of synaptic plasticity that is dependent on new protein synthesis and protein kinase activation [16]. Previous studies showed that the disruption of hippocampal MAPK oscillations results in theta rhythm oscillation deficits in NF1 mouse models [17]. In the Rev-erbα KO mice, L-LTP was induced normally and the potentiation levels stably lasted for 3 hours. No significant differences in the magnitude of L-LTP were observed between the Rev-erbα KO mice and their WT littermates, both at CT0~CT2 and at CT12~CT14 (Fig. 3A, B). These results indicate that REV-ERBα does not alter the LTP, which is dependent on protein synthesis.

Fig. 3. L-LTP is unaffected in the Rev-erbα KO mice during the subjective day and night. Example traces from baseline and LTP at times indicated by (a) and (b): WT (black) and KO (red or blue). (A) During the subjective day, Rev-erbα KO mice did not exhibit any impairment in the TBS-induced hippocampal L-LTP, and the potentiation level was maintained at a level comparable with that in the WT mice for 3 h (WT, 7 slices from 6 mice; Rev-erbα KO, 6 slices from 6 mice; average fEPSP slopes for the last 5 min; WT, 139.6%±5.199%; Rev-erbα KO, 128.2%±7.817%; unpaired t test; p=0.2388). (B) During the subjective night, Rev-erbα KO mice did not show any deficits in the TBS-induced hippocampal L-LTP (WT, 6 slices from 6 mice; Rev-erbα KO, 6 slices from 6 mice; average fEPSP slopes for the last 5 min; WT, 132.6%±5.213%; Rev-erbα KO, 143.6%±7.963%; unpaired t test; p=0.2736).

The present study shows the electrophysiological role of REV-ERBα in the hippocampus. We found that the magnitude of E-LTP was impaired only at CT12~CT14. The subjective night-specific deficit we observed is consistent with the findings of the previous study by Schnell et al. in that the REV-ERBα expression level peaked during CT08~CT12 [11]. It is interesting that the Reverbα KO mice exhibited impairments in hippocampus-dependent behaviors during CT0~CT4 [12], which includes the condition of subjective day (CT0~CT2) in this study. However, our results showed that the basic synaptic properties, short-term plasticity, and NMDAR-dependent synaptic plasticity are not altered at subjective day (CT0~CT2). The discrepancy in the behavioral and electrophysiological results can be explained by the fact that REV-ERBα is widely expressed during development; therefore, the behavioral effect observed at CT0~CT4 in the Rev-erbα KO mice could be due to developmental brain defects. Thus, further investigation is needed to explain the association, and by performing hippocampus-dependent behavioral tasks at CT12~CT14, we may be able to explain the relationship between behavior and electrophysiology in the Rev-erbα KO mice.

The hippocampus is one of the targets of dopaminergic projections from the midbrain [18]. Moreover, the CA1 region of the hippocampus expresses dopamine receptors [19], and dopamine release during specific time points is important in long-term memory consolidation [20]. A recent study by Broussard and colleagues showed that dopamine regulates synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus [21]. The Rev-erbα KO mice showed dopaminergic hyperactivity [9,12] and significantly higher spontaneous dopamine release from striatal tissue than the WT mice at CT12 [9]. Therefore, we might interpret that the hyperdopaminergic state of the Rev-erbα KO mice may be the tentative mechanism of the significantly lower potentiation magnitude at CT12~CT14.

In several species, learning and memory, synaptic transmission, and LTP are known to show dependence on the time of day [22,23]. According to previous studies by Jilg et al. [24] and Wang et al. [25], Per1-knockout mice showed deficits in hippocampus-dependent long-term spatial learning and Per2-mutant mice exhibited impairments in the hippocampal LTP. Our data reveal that another circadian oscillator, REV-ERBα, is involved in phase-dependent hippocampal LTP dynamics. In addition, the Rev-erbα KO mice exhibited impaired E-LTP at CT12~CT14 with intact L-LTP at both time points, which requires new protein synthesis. The result can be explained by the study by Sakai and colleagues, in which they showed that long-term memory is independent of the circadian rhythm [1]. However, the exact mechanism underlying the regulation of protein synthesis-dependent and protein synthesis-independent synaptic plasticity by Rev-erbα is yet to be discovered.

In summary, REV-ERBα is an important circadian protein for regulating the magnitude of hippocampal E-LTP during the subjective night.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Honor Scientist Program (NRF-2012R1A3A1050385) of Korea. J.E.C was supported by a Fellowship for Fundamental Academic Fields by Seoul National University.

References

- 1.Sakai T, Tamura T, Kitamoto T, Kidokoro Y. A clock gene, period, plays a key role in long-term memory formation in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16058–16063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401472101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia JA, Zhang D, Estill SJ, Michnoff C, Rutter J, Reick M, Scott K, Diaz-Arrastia R, McKnight SL. Impaired cued and contextual memory in NPAS2-deficient mice. Science. 2000;288:2226–2230. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5474.2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckel-Mahan KL. Circadian oscillations within the hippocampus support memory formation and persistence. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012;5:46. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright KP, Jr, Hull JT, Czeisler CA. Relationship between alertness, performance, and body temperature in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R1370–R1377. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00205.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi JS, Hong HK, Ko CH, McDearmon EL. The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: implications for physiology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:764–775. doi: 10.1038/nrg2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature. 2002;418:935–941. doi: 10.1038/nature00965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Preitner N, Damiola F, Lopez-Molina L, Zakany J, Duboule D, Albrecht U, Schibler U. The orphan nuclear receptor Rev-erbα controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell. 2002;110:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerhart-Hines Z, Feng D, Emmett MJ, Everett LJ, Loro E, Briggs ER, Bugge A, Hou C, Ferrara C, Seale P, Pryma DA, Khurana TS, Lazar MA. The nuclear receptor Rev-erbα controls circadian thermogenic plasticity. Nature. 2013;503:410–413. doi: 10.1038/nature12642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung S, Lee EJ, Yun S, Choe HK, Park SB, Son HJ, Kim KS, Dluzen DE, Lee I, Hwang O, Son GH, Kim K. Impact of circadian nuclear receptor Rev-erbα on midbrain dopamine production and mood regulation. Cell. 2014;157:858–868. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delezie J, Dumont S, Sandu C, Reibel S, Pevet P, Challet E. Rev-erbα in the brain is essential for circadian food entrainment. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29386. doi: 10.1038/srep29386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnell A, Chappuis S, Schmutz I, Brai E, Ripperger JA, Schaad O, Welzl H, Descombes P, Alberi L, Albrecht U. The nuclear receptor Rev-erbα regulates Fabp7 and modulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jager J, O'Brien WT, Manlove J, Krizman EN, Fang B, Gerhart-Hines Z, Robinson MB, Klein PS, Lazar MA. Behavioral changes and dopaminergic dysregulation in mice lacking the nuclear receptor Rev-erbα. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28:490–498. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valnegri P, Khelfaoui M, Dorseuil O, Bassani S, Lagneaux C, Gianfelice A, Benfante R, Chelly J, Billuart P, Sala C, Passafaro M. A circadian clock in hippocampus is regulated by interaction between oligophrenin-1 and Rev-erbα. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1293–1301. doi: 10.1038/nn.2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim CS, Nam HJ, Lee J, Kim D, Choi JE, Kang SJ, Kim S, Kim H, Kwak C, Shim KW, Kim S, Ko HG, Lee RU, Jang EH, Yoo J, Shim J, Islam MA, Lee YS, Lee JH, Baek SH, Kaang BK. PKCα-mediated phosphorylation of LSD1 is required for presynaptic plasticity and hippocampal learning and memory. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4912. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05239-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim S, Yu NK, Shim KW, Kim JI, Kim H, Han DH, Choi JE, Lee SW, Choi DI, Kim MW, Lee DS, Lee K, Galjart N, Lee YS, Lee JH. Remote Memory and Cortical Synaptic Plasticity Require Neuronal CCCTC-Binding Factor (CTCF) J Neurosci. 2018;38:5042–5052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2738-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kandel ER, Dudai Y, Mayford MR. The molecular and systems biology of memory. Cell. 2014;157:163–186. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen L, Serdyuk T, Yang B, Wang S, Chen S, Chu X, Zhang X, Song J, Bao H, Zhou C, Wang X, Dong S, Song L, Chen F, He G, He L, Zhou Y, Li W. Abnormal circadian oscillation of hippocampal MAPK activity and power spectrums in NF1 mutant mice. Mol Brain. 2017;10:29. doi: 10.1186/s13041-017-0309-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasbarri A, Packard MG, Campana E, Pacitti C. Anterograde and retrograde tracing of projections from the ventral tegmental area to the hippocampal formation in the rat. Brain Res Bull. 1994;33:445–452. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mu Y, Zhao C, Gage FH. Dopaminergic modulation of cortical inputs during maturation of adult-born dentate granule cells. J Neurosci. 2011;31:4113–4123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4913-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossato JI, Bevilaqua LR, Izquierdo I, Medina JH, Cammarota M. Dopamine controls persistence of long-term memory storage. Science. 2009;325:1017–1020. doi: 10.1126/science.1172545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broussard JI, Yang K, Levine AT, Tsetsenis T, Jenson D, Cao F, Garcia I, Arenkiel BR, Zhou FM, De Biasi M, Dani JA. Dopamine regulates aversive contextual learning and associated in vivo synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Cell Reports. 2016;14:1930–1939. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyons LC, Rawashdeh O, Eskin A. Non-ocular circadian oscillators and photoreceptors modulate long term memory formation in Aplysia. J Biol Rhythms. 2006;21:245–255. doi: 10.1177/0748730406289890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaudhury D, Wang LM, Colwell CS. Circadian regulation of hippocampal long-term potentiation. J Biol Rhythms. 2005;20:225–236. doi: 10.1177/0748730405276352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jilg A, Lesny S, Peruzki N, Schwegler H, Selbach O, Dehghani F, Stehle JH. Temporal dynamics of mouse hippocampal clock gene expression support memory processing. Hippocampus. 2010;20:377–388. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang LM, Dragich JM, Kudo T, Odom IH, Welsh DK, O'Dell TJ, Colwell CS. Expression of the circadian clock gene Period2 in the hippocampus: possible implications for synaptic plasticity and learned behaviour. ASN Neuro. 2009;1:e00012. doi: 10.1042/AN20090020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]