Summary

Cystic fibrosis is a chronic, life-shortening illness that affects multiple systems and results in frequent respiratory infections, chronic cough, fat malabsorption and malnutrition. Poor sleep is often reported by patients with cystic fibrosis. Although objective data to explain these complaints have been limited, they do show poor sleep efficiency and frequent arousals. Abnormalities in gas exchange are also observed during sleep in patients with cystic fibrosis. The potential impact of these abnormalities in sleep on health and quality of life remains largely unstudied. This review summarizes what is known about sleep in children with cystic fibrosis, and implications for clinical practice. This report also highlights new evidence on the impact of sleep problems on disease-specific outcomes such as lung function, and identifies areas that need further exploration.

Keywords: Sleep, Cystic Fibrosis, Sleep-Disordered Breathing, Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Children, Adolescents, Hypoxemia

Introduction

More than a quarter of all children will suffer from sleep disturbances at some point in their childhood (1). Sleep disturbances have a significant negative impact on mood, behavior, academic performance and cognitive function (2–8). Poor sleep increases susceptibility to certain infections such as the common cold (9) and is associated with elevated serum inflammatory markers (9–11). Furthermore, sleep disorders are linked to the development of obesity, hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance (12–15).

As sleep problems have the potential to be so consequential, their high prevalence among children with chronic respiratory diseases, such as cystic fibrosis (CF), raises particular concern (1, 16). Cystic fibrosis is a lethal genetic disease that affects approximately 30,000 individuals in the United States and is the most common genetic disease in Caucasians (17). A progressive decline in lung function occurs over time, due to a combination of lower airway inflammation and recurrent respiratory infections, that culminates in respiratory failure (18, 19). The median age of survival for a person with CF is about 47 years (17).

Cystic fibrosis also affects other organ systems, including the pancreas and liver, resulting in fat malabsorption, vitamin deficiencies and protein-calorie malnutrition (17, 18). Cystic Fibrosis Related Diabetes (CFRD), from a combination of insulin deficiency and insulin resistance, is a common complication, and one that has a negative impact on lung function, nutritional status and survival (20). Pulmonary hypertension, frequently seen among patients with CF who have advanced lung disease, is also associated with significant morbidity and mortality (21). The protein that is affected in CF, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), has been identified in immune cells (lymphocytes) and neural cells (anterior hypothalamus and spinal cord), although understanding of its role in these areas is still emerging (22).

Sleep disorders are known to have an adverse impact on several areas that are relevant to the health of children with CF. However, direct studies of the effects of poor sleep in this population have not been numerous. For example, although insufficient sleep is increasingly recognized as a risk factor for early mortality, particularly among young adults (23), the true prevalence of sleep disruption in CF remains uncertain. Furthermore, little is known about which patients with CF might be at risk for sleep disorders, when or even how to screen these individuals for sleep disturbances, or what is the optimal treatment strategy to address these sleep problems. Therefore, to address this gap in the literature, we undertook a review of all the publications on sleep in children with CF that were featured in Pubmed, EMBASE and Scopus up until March 2018. We used the keywords “cystic fibrosis” and “sleep” to search for relevant publications. We then manually sorted through all of the publications to identify the ones that pertained to children (age ≤ 18 years). We identified fifteen polysomnography and seven actigraphy studies (Table 1). Seven of these studies also included adults with CF. The majority were cross-sectional analyses of children with CF. A few of the cross-sectional studies also included healthy age-matched controls for comparison. Only one out of the twenty-two studies was a randomized controlled trial. This review critically evaluates the current literature on sleep in pediatric CF and also explores the available evidence for the impact of sleep disturbances on the care of these individuals.

Table 1: A Summary of Relevant Studies Evaluating Sleep in Children with CF.

| Study | Design | Sample Size; Age (Mean & Range) CF | Sample Size; Age (Mean & Range) Controls | FEV1 PPD (Mean & Range) | Assessment Tools | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tepper et al 1983(46) | Cross-sectional | 6; 15y (10–16y) | 0 | N/A | Polysomnography | Reduced ventilation during REM sleep was associated with nocturnal hypoxemia in patients with CF |

| Villa et al 2001 (37) | Case-control | 19; 13.1m (3–36m) | 20; age-matched | N/A | Polysomnography | Nocturnal SpO2 was worse in infants with CF who had respiratory symptoms vs asymptomatic infants/controls |

| Naqvi et al 2008 (25) | Cross-sectional | 24; 14.2y | 14; 10.7y (historical) | N/A | Questionnaire, Polysomnography, CO2 levels | Children with CF vs controls had lower sleep efficiency, reduced REM sleep; Sleep efficiency was associated with FEV1 PPD but not nocturnal SpO2 or CO2 levels |

| Ramos et al 2009 (61) | Cross-sectional | 63; 7.6y (2.3–14.5y) | 0 | N/A | Questionnaire, Polysomnography | 56% of subjects had OSA; OSA group was younger (age < 6 years), more likely to be Black, & had more upper airway obstruction (tonsillar hypertrophy, rhinosinusitis) |

| Ramos et al2011 (62) | Cross-sectional | 67; 8y(5–10y) | 0 | N/A | Questionnaire,Polysomnography | 57% of children with CF had OSA; 18% had moderate OSA (Obstructive Apnea Index between 5–10); OSA group had worse nocturnal hypoxemia but similar TST and sleep efficiency |

| Spicuzza et al 2012 (36) | Case-control | 40; 6m-11y | 18; age-matched | 78.6 (72–98) | Polysomnography | CF vs controls had higher AHI (7.3 vs 0.5), lower nocturnal SpO2, lower sleep efficiency, more arousals, reduced REM sleep; Subjects with CF who had a higher AHI were younger (age < 6y) & had more upper airway obstruction |

| Ramos et al 2013 (50) | Cross-sectional | 67; 8y (5–10y) | 0 | 78.5 (67–93) | Polysomnography | 27% of subjects had nocturnal SpO2<85%; 6% had SpO2<90% for >5%TST; Hypoxemia linked to lower FEV1 PPD & higher AHI; 13.4% of the subjects had AHI ≥5 |

| Paranjape et al 2015 (39) | Retrospective review | 10; 9.6y | 10; 9.6y | 87 (36–115) | Polysomnography, CO2 levels, airflow analysis | Lower nocturnal SpO2, higher respiratory rate & more inspiratory flow limitation in CF vs snoring controls; TST, AHI, sleep efficiency and duration of REM sleep were similar between the groups |

| Silva et al 2016 (26) | Cross-sectional | 33; 12y (6–18y) | 0 | N/A (z-score-1.76) | Questionnaire, Polysomnography, CO2 levels | Children with CF had low sleep efficiency & high WASO based on normative data; Frequency of arousals, SpO2 & CO2 levels were normal; Awake SpO2 negatively associated with AHI; Positive correlation between nocturnal SpO2 & FEV1 |

| Waters et al 2017 (27) | Cross-sectional | 46; 11.1y (8.2–13.4y) | 0 | 75.7 (19–125) | Questionnaire, Polysomnography | 74% of subjects with CF had > 1 apnea or hypopnea per hour of sleep; 24% had nocturnal hypercapnia; FEV1 PPD linked to change in nocturnal CO2 levels & respiratory rate during sleep |

| Muller et al 1980 (48) | Case-control | 20; 18.2y (8.8–29.3y) | 5; 26.2y (22.4–30.4y) | 35.7 | Polysomnography, magnetometers | Largest decline in SpO2 occurred during REM sleep due to reduction in functional residual capacity with further worsening due to periods of hypoventilation during sleep |

| Francis et al 1980 (49) | Case-control | 20; 18.2 (8.8–29.3y) | 5; 26.2y (22.4–30.4y) | 35.7 | Polysomnography, magnetometers | CF vs controls had lower daytime & nocturnal SpO2 & had greater declines in SpO2 during sleep; In subjects with CF fall in SpO2 during REM sleep was worse than during non-REM sleep; Fall in SpO2>3% during REM sleep was associated with pulmonary hypertension |

| Castro-Silva et al 2009 (38) | Cross-sectional | 40; 12.8y (6–28y) | 20; 15.5y (historical) | 65.3 | Questionnaire, Polysomnography | 15% of subjects with CF and clinical lung disease had SpO2<90% for >30%TST; 37% had SpO2<85%; FEV1 PPD<64% predicted likelihood of nocturnal hypoxemia with approximately 90% sensitivity, 80% specificity |

| Suratwala et al 2011 (35) | Prospective observational | 25; 14y (8–20y) | 25; 14y (7–20y) (historical) | 92 | Questionnaire, Actigraphy, Polysomnography | CF vs controls had more arousals, lower nocturnal SpO2 but similar TST, sleep efficiency, WASO; Lower SpO2 was associated with worse glucose tolerance |

| Veronezi et al 2015 (63) | Cross-sectional | 34; 15.9 (6–33y) | No | 70.9 (12–100) | Questionnaire, Polysomnography | No correlation between FEV1 PPD and AHI; Awake SpO2 negatively associated with AHI |

| Amin et al 2005 (24) | Case-control | 44; 11.9y | 40; 12.6y | 74 | Questionnaire, Actigraphy | CF vs controls had lower sleep efficiency & more arousals; FEV1 PPD correlated positively with TST, sleep efficiency & negatively with frequency of arousals |

| Vandeleur et al 2017 (31) | Case-control | 87; 12.2y (7.1–18.9y) | 55; 12.1 y (7.1–18.2y) | 78.2 (25–125) | Questionnaires, Oximetry, Actigraphy | No differences in sleep-wake times between CF & controls; Subjects with CF vs controls had lower TST, poorer sleep efficiency, more arousals, higher WASO; FEV1 PPD & nocturnal SpO2 levels correlated positively with TST, sleep efficiency & negatively with WASO & frequency of arousals |

| Vandeleur et al 2017 (55) | Prospective Observational | 87; 12.2y (7.1–18.9y) | 0 | 78.2 (25–125) | Questionnaire, Actigraphy, Oximetry | Multiple respiratory co-morbidities (reduced lung function, nocturnal cough, asthma) & non-respiratory co-morbidities (CF-related diabetes, use of nocturnal tube feeds) were associated with reduced TST and poor sleep efficiency in subjects with CF |

| Vandeleur et al 2017 (32) | Case-control | Child: 47; 10y (7.1–12.9) Teen: 40; 15.8y (13.1–18.9) | Child: 35; 10.6y (7.1–12.8) Teen: 20; 15.5y (13.3–18.3) | Child: 81 (36–112) Teen: 81 (25–125) | Questionnaire, Actigraphy, Oximetry | CF vs controls had reduced TST, increased WASO, lower sleep efficiency, lower nocturnal SpO2, worse sleep quality; Poor sleep associated with increased depressive symptoms in children but not adolescents/controls; In all subjects with CF, poor sleep was linked to impaired quality of life |

| Cavanaugh et al 2016 (73) | Prospective Observational | 50; 11.6 (6–18y) | 0 | 100.4 | Actigraphy | 80% of subjects had a sleep efficiency<90%; Sleep efficiency was negatively associated with inattentiveness & hyperactivity; Neither sleep efficiency nor WASO linked to quality of life |

| Castro-Silva et al 2010 (34) | Randomized Controlled trial | 19; 13.8 (7–28y) | 10 in Placebo group | 74.1 (27–98) | Questionnaires, Actigraphy | Negative correlation between FEV1 PPD & sleep onset latency; 83% of subjects had poor sleep efficiency & 95% had WASO> 60min at baseline; Melatonin improved sleep efficiency, latency |

| Fauroux et al 2012 (30) | Prospective Observational | 80; 24y (25 were ≤18y) | 0 | 41 (46 in children) | Questionnaires, Actigraphy, Oximetry, CO2 levels | Subjects had low sleep efficiency & excessive arousals based on normative data; 18% had SpO2<90% for >10% TST (correlated with daytime SpO2 levels & FEV1 PPD); 47% had hypercapnia (correlated with daytime CO2 levels) |

| Meltzer et al 2012 (33) | Case-Control | 45; 7.2y (3–12y) | 45; 7.2y (3–12y) | 107.2 | Questionnaire | CF vs controls had different sleep-wake times, reduced TST, more symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing; Health perception impacted reporting of sleep complaints in CF |

| Cepuch et al 2017 (28) | Cross-sectional | 70; 14–25y | 0 | N/A | Questionnaire | Poor sleep associated with greater anxiety, depression & aggressive symptoms in adolescents with CF |

| Tomaszek et al 2018 (29) | Cross-sectional | 95; 14–25y | 0 | 66.7 | Questionnaire | Insomnia identified in 38% of adolescents with CF; Poor sleep quality associated with poor mood, impaired quality of life |

Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI); Carbon dioxide (CO2); Cystic Fibrosis (CF); Forced expiratory volume in one second percent predicted (FEV1 PPD); Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA); Oxygen Saturation (SpO2); Rapid Eye Movement (REM) Sleep; Total sleep time (TST); Wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO);

Poor sleep quality

Children with CF report poor sleep quality with difficulties initiating sleep, frequent awakenings, snoring, and trouble breathing (24–29). Daytime sleepiness is also a problem for these children (24, 25, 30–32). Sleep complaints may be especially common among patients with poorer health (33). On actigraphy and polysomnography, children with CF, in comparison to healthy controls, tend to have a shorter total sleep time, lower sleep efficiency, increased frequency of arousals, and a longer duration spent in wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO) (24, 25, 30–32, 34–36). The amount of time spent in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep might be lower in children with CF (25, 36, 37), although this is not universally supported (26, 35, 38, 39). Children with CF may have a prolonged sleep onset latency (26, 30, 34) but this finding also is not consistently supported (25, 31, 35, 38).

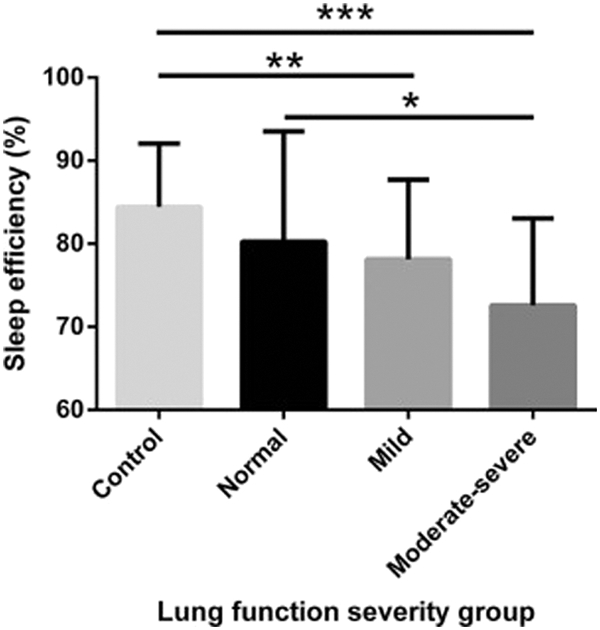

Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) percent predicted, a measure of lung function commonly used as a marker of CF disease severity (19, 40), has been linked to sleep efficiency in children with CF (Figure 1) (24, 25, 31). Children who have a lower FEV1 % predicted tend to have a lower sleep efficiency, longer sleep latency, and more awakenings, and they spend a longer time in WASO (24, 31, 34). Sleep duration and efficiency have both been shown to independently predict FEV1 % predicted in children with CF (24, 31).

Figure 1:

Sleep efficiency of control children and children with CF across 3 different groups of FEV1 (normal [≥90%], mild [70%−89%], moderate-severe [<70%]). A significant difference was found in the children with CF across the 3 groups (P = .03) after controlling for sex, age, and SES (univariate analysis). A significant difference was measured between CF patients with normal lung function vs CF patients with moderate-severe lung function (*P < .05). A significant difference also was measured between control children and CF patients with mild (**P < .01) and moderate-severe (***P < .001) lung function but not those with normal lung function (P = .08). Reprinted from Journal of Pediatrics, 182, Vandeleur M, Walter LM, Armstrong DS, Robinson P, Nixon GM, Horne RS, How Well Do Children with Cystic Fibrosis Sleep? An Actigraphic and Questionnaire-Based Study, 170–176, Copyright (2017), with permission from Elsevier.

Although adults in comparison to children with CF also complain of poor sleep and tend to have more severe lung disease, objective findings of sleep disturbance have been scarce in this group (41–44). Compared to healthy controls, adults with CF have more sleep fragmentation, a higher frequency of arousals, and a larger number of sleep stage transitions per hour of sleep (41, 42, 45). Both adolescents and adults with CF who have pulmonary hypertension, as compared to those who have normal pulmonary artery pressures, have lower sleep efficiency (21). They also have lower lung function, worse exercise tolerance, and greater abnormalities on chest radiography (21). Whether the severe lung disease or the pulmonary hypertension itself predisposes these individuals to poor sleep quality needs further study.

Nocturnal hypoxemia

Individuals with CF often experience a significant decline in their oxygen saturation during sleep from what is believed to be a sleep-related reduction in lung volumes and ventilation (46, 47). This desaturation is worse during REM sleep as compared to non-REM (NREM) or slow-wave sleep (37, 46–49). Clinically significant nocturnal hypoxemia has been observed in children with moderate-severe CF lung disease (38, 46, 50). Compared to healthy controls, children with CF, including those with no clinical evidence of lung disease, tend to have lower nocturnal oxygen saturations and a higher frequency of desaturation episodes, despite having similar, normal daytime saturations (25, 31, 32, 35, 36, 38, 51). Unlike in adults with the disease where the degree of hypoxemia during sleep has been shown to be worse than that observed during exercise (44), in children with CF the oxygen nadir during sleep and exercise appear to be similar (52).

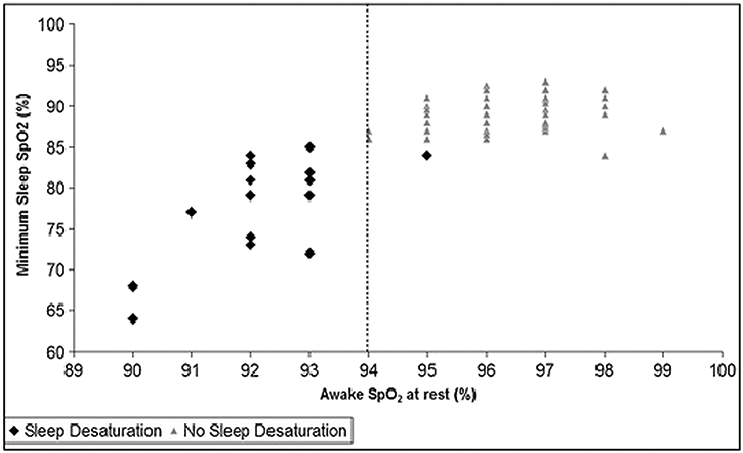

In both children and adults, oxygen levels during sleep have been shown to vary with awake resting oxygen saturation and markers of CF lung disease severity such as FEV1 % predicted, Schwachman-Kulczycki clinical disease severity score, and findings on chest radiography and computed tomography (26, 27, 30, 38, 41, 50–54). An awake resting oxygen saturation < 94% (Figure 2) or an FEV1 % predicted < 64% may predict likelihood of nocturnal hypoxemia to an extent that could be clinically useful (38, 41, 52).

Figure 2:

Relationship between the minimum sleep SpO2 and awake SpO2 at rest in sitting position. The vertical line represents the threshold (awake SpO2 = 94%) that best separates patients who did desaturate (diamonds) from those who did not desaturate (triangles). Reprinted from Sleep and Breathing, Sleep findings and predictors of sleep desaturation in adult cystic fibrosis patients, 16, 2012, 1041–1048, Perin C, Fagondes SC, Casarotto FC, Pinotti AF, Menna Barreto SS, Dalcin Pde T, © Springer-Verlag 2011, with permission of Springer.

Nocturnal hypoxemia has been linked to poor subjective sleep quality, a reduced sleep efficiency and total sleep duration among children and adults with CF (38, 41, 43, 55, 56). The frequency of elevated pulmonary artery systolic pressures and pulmonary hypertension is higher among patients with CF who experience desaturations during sleep (21, 41, 49). Patients with pulmonary hypertension also have hypoxemia during exercise (21, 41), and lower daytime oxygen saturations as compared to those without this comorbidity (21). Nocturnal hypoxemia may be the missing piece in a mechanistic link between poor sleep and CF disease severity, given that low oxygen levels during sleep are independently associated with severe CF lung disease and disrupted or fragmented sleep.

Nocturnal Hypercapnia

Both children and adults with CF can have impaired ventilation, as documented by elevated carbon dioxide (CO2) levels (hypercapnia) during sleep (27, 30, 35, 41, 46, 57). The presence of pulmonary hypertension has been associated with higher daytime and nocturnal CO2 levels (21, 41). The CO2 levels also have been noted to rise following treatment of nocturnal hypoxemia with supplemental oxygen (45, 47, 58, 59). Notably though, these studies were conducted largely in adults with CF and most children with the disease tend to have normal CO2 levels, both during wakefulness and sleep (26, 39).

Nocturnal hypercapnia, when present, has been associated with poor subjective sleep quality (30, 43), low lung function (27, 41, 57), and reduced nocturnal oxygen saturations (26, 41). Differences in FEV1 % predicted have been observed between children with CF who experience any increase in their CO2 levels during sleep and those whose nocturnal CO2 levels are unchanged (68 vs 83%, respectively) (27). However, this relationship between nocturnal CO2 levels and FEV1 % predicted is not straightforward (26, 35). Abnormalities in nocturnal CO2 levels have been noted in children with CF who have normal lung function (35) whereas no differences in nighttime CO2 levels have also been observed between those with normal vs abnormal FEV1 % predicted values (26). More work is clearly needed to better understand this important relationship between lung function and nocturnal hypercapnia. Data on the impact of nocturnal hypercapnia on objective measures of sleep quality, such as sleep duration and sleep efficiency, is also sparse.

Increased respiratory rate during sleep

Compared to healthy controls, patients with CF have a higher respiratory rate during NREM sleep (39, 44, 60). Adults with CF who experience tachypnea while awake tend to have lower nocturnal oxygen saturations and worse hypercapnia (41). Among children with CF, an increased respiratory rate during sleep has been associated with a lower FEV1 % predicted and poor nutritional status (27). However, any additional clinical significance of having tachypnea during sleep remains to be demonstrated.

Obstructive sleep apnea

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) refers to a range of disorders, from primary snoring to obstructive or central sleep apnea, that affect respiration during sleep. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), a common and consequential form of SDB, is characterized by repeated cessation or diminution of airflow during sleep, due to upper airway obstruction and despite adequate continued respiratory effort. The frequency of OSA is higher among young children with CF as compared to healthy controls (36, 61–63). Polysomnography in children with CF between 6 months and 11 years of age reveals moderate OSA (apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 5) in approximately 46% (36). Risk factors for OSA in children with CF are similar to those in other populations and include age less than 6 years, black race, nasal obstruction (from inflammation of the nasal mucosa and sinuses or nasal polyps), mouth breathing, and tonsillar hypertrophy (36, 61).

Nocturnal oxygen saturations are lower among children with CF who have OSA as compared to those who do not (27, 36, 50, 61, 62). However, the severity of the SDB in these children does not appear linked to the degree of pulmonary impairment as measured by the FEV1 % predicted (27, 63). Furthermore, sleep efficiency and frequency of arousals also seem no different in childhood CF with and without OSA (61). This raises the possibility that, despite the high prevalence of SDB in children with CF, the OSA might not explain the increased burden of sleep complaints. However, in the two studies that have evaluated the potential relationship between lung function and SDB to date, all or most of the participants had a normal AHI (27, 63). The possibility also remains that children with SDB may have subtle inspiratory microarousals not readily detected by standard polysomnography but still impactful on sleep quality (64–66). Application of these more advanced techniques might lead to better identification of sleep disturbances among patients with CF.

Another important area where a scarcity of data exists concerns the impact of SDB on health outcomes among children with CF. For example, OSA has been shown to have a negative impact on inflammatory and immune processes (9). The sleep disorder has also been implicated in the development of insulin resistance (14, 15). Yet, whether patients with CF who have SDB, as compared to those who do not, have more infective pulmonary exacerbations remains unknown. The prevalence of CFRD among children with and without OSA also has not been identified.

Impact of sleep disturbances

Insufficient or inadequate sleep has been associated with an increased risk for mortality among non-CF adults (23, 67). A large, systematic review and meta-analysis of adults without CF identified a relative risk for all-cause mortality of 1.06 annually for every one-hour reduction in total sleep time from 7 hours (67). Children with CF have been commonly reported to have a sleep duration that is less than 7 hours (26, 27, 30, 32, 34, 35, 39, 46, 62). This is particularly problematic as children, in comparison to adults, have higher daily sleep requirements.

In healthy children, inadequate sleep has been linked to impairments in quality of life, poor academic performance, inattentiveness, and problems with mood and behavior (3–8, 68–70). The frequency of these deficits, particularly with regards to attention and executive functioning, is elevated among children with OSA (4, 5, 7, 69, 71). While children with CF also suffer from many of these same problems, whether the presence of sleep disturbances has any additional adverse impact is not well understood. Compared to healthy controls, children with CF have greater deficits in executive functioning, memory and attention (72, 73). Significant neurocognitive impairments have also been noted among adults with CF in comparison to healthy controls, with inferior performance in areas of serial reaction and simple arithmetic (56). Adults with CF admitted with a pulmonary exacerbation, in comparison to those who are stable, have a lower number of correct responses per minute on serial addition and subtraction tasks (74). In both of the adult studies, significant differences in subjective and objective sleep quality also emerged between the groups (56, 74). Similar studies looking at neurocognitive performance and sleep are still needed among children with CF. Children and adults with CF who report poor subjective sleep quality also report reduced quality of life (29, 75, 76). Areas that appear to be impaired, especially among the adolescents, include physical, social and emotional functioning; vitality; and health perception (32). Poor mood is another consequence of inadequate sleep among children with CF (32). Subjective complaints of insomnia, and more objective measures of poor sleep, such as a lower sleep efficiency and a longer time spent in WASO, have all been associated with inattentiveness, hyperactivity and a greater frequency of anxiety and depressive symptoms (28, 29, 32, 77).

Insufficient sleep has been associated with the presence of elevated serum inflammatory markers even among healthy subjects (10). Adolescents who have symptoms of insomnia, and an average total sleep time of ≤ 7 hours as opposed to ≥ 8 hours per night, have higher levels of serum inflammatory markers (11). The detrimental effects of inadequate sleep on inflammation are relevant to patients with CF as the primary pathology in CF lung disease is chronic airway inflammation (18). Whereas elevated serum inflammatory markers have been reported in patients with CF, no associations were found between these biomarkers and sleep in the single study that has investigated this possibility (35).

In non-CF individuals, poor sleep has been shown to increase the susceptibility to certain infections, such as rhinovirus (9). Reduction in the total sleep time also is associated with a decreased response to the influenza A vaccine (9). These observations could carry significance for patients with CF as the majority of pulmonary exacerbations are triggered by viral infections. However, the relationship between frequency of pulmonary exacerbations and sleep disruption has not been evaluated among children with CF. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a pathogen commonly seen in the lungs of patients with CF, changes its phenotype and potentially becomes more resistant to host defenses in the setting of hypoxia (78). Although colonization with Pseudomonas aeruginosa has been long recognized as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with CF (79), data on colonization rates among those with and without sleep disturbances are lacking.

Reduced sleep duration also is associated with an increased risk for hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance among healthy children (12, 14, 15). A 60-minute increase in total sleep time lowers fasting glucose levels and degree of insulin resistance (15). A negative correlation between nocturnal oxygen saturations and daytime glucose levels that is independent of age and body mass index has been identified in children with CF (35). However, the authors did not observe any associations with other sleep parameters or markers of disease severity such as FEV1 % predicted (35). Given the known relationships between poor sleep and glucose in the general population, this is an area that is ripe for future study.

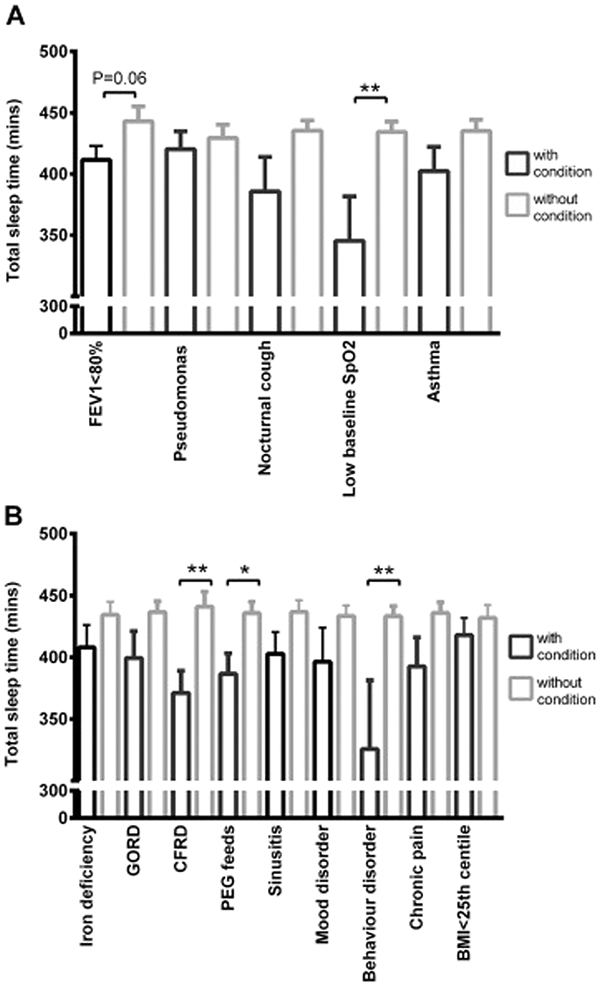

Potential causes for sleep disturbances

Several factors are known to have a negative impact on sleep in patients with CF (Figure 3). Medications such as albuterol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, fluoroquinolone antibiotics and prednisone, that are often used by children with CF, either as part of their maintenance regimen or during disease exacerbations, all have insomnia listed as a side-effect. Nighttime cough is cited frequently by children with CF as a cause for their awakenings from sleep (24, 27, 55). Compared to healthy controls, children with CF, and particularly those with more severe lung disease, have a higher frequency of nocturnal cough (80). On actigraphy, the presence of nocturnal cough is associated with a shorter total sleep time, lower sleep efficiency, and longer time spent in WASO (55).

Figure 3:

Total sleep time of children with CF, with and without (A) respiratory co-morbidities or (B) non-respiratory co-morbidities. Data presented as mean ± SEM * p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01. Reprinted from Journal of Cystic Fibrosis, 16(6), Vandeleur M, Walter LM, Armstrong DS, Robinson P, Nixon GM, Horne RSC, What keeps children with cystic fibrosis awake at night?, 719–726, Copyright (2017), with permission from Elsevier.

Children with asthma, another respiratory condition that is characterized by airway inflammation and airflow obstruction, also have a high frequency of sleep disturbances, often due to the presence of a nighttime cough (16). The approximately 20% of patients with CF who also have asthma, in comparison to those without this comorbidity, tend to have a lower sleep efficiency, and spend a longer duration in WASO (55, 81).

Approximately 20% of adolescents and 40% of young adults with CF have CFRD (20). Sleep duration, but not sleep efficiency or duration of WASO, appears to be affected in patients with CF who have this co-morbid condition (55). However, no temporal relationship has been reported, meaning that whether insufficient sleep may precede and contribute to risk for CFRD remains unknown.

Malnutrition is a common problem among patients with CF and, in particular, among those with poor lung function or comorbidities like CFRD (18). Poor nutritional status is a known risk factor for mortality before the age of 18 years among individuals with CF (79). These patients, therefore, often utilize enteral feedings at night to provide additional nutrition (82). However, this might lead to disruptions in the normal circadian rhythm and potentially worsen sleep quality in patients with CF. Children with CF who receive nocturnal tube feeds, in comparison to those who do not, tend to have a shorter total sleep time, lower sleep efficiency and longer duration of WASO (55).

Gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain (29, 83–85), acid reflux (16, 86, 87), flatulence and loose, malodorous stools (18) are also potential sources of sleep disruption in these children. Frequent trips to the bathroom for defecation have been quoted by children and their parents as a cause for their nocturnal arousals (24). Results from esophageal pH monitoring and intraluminal impedance probes suggest that approximately 55–70% of children with CF may have reflux (86, 87). Patients with CF who have reflux, as compared to those who do not, tend to have lower lung function, and earlier acquisition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (87). Although reflux has been associated with increased frequency of respiratory symptoms (88), poor sleep quality, and more fragmented sleep (89) in other pediatric populations, the single study that has looked at the impact of reflux on sleep in children with CF found no abnormalities in sleep efficiency, duration or time spent in WASO (55).

Sleep disturbances including difficulties with sleep-onset and maintenance, frequent arousals, increased sleep fragmentation and daytime sleepiness are frequently observed among children with chronic pain (90). Children and adolescents with CF also struggle with chronic pain (29, 83–85). Although an association between pain and poor quality of life has been well established (83–85), few data exist on how chronic pain affects sleep quality in CF. Only a small fraction of children with CF who describe pain also report symptoms of insomnia (84, 85). The intensity of the pain may be higher though among patients with poorer sleep quality (29).

Factors that are not disease-specific, such as the presence of a behavior disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in particular, or poor sleep hygiene also could have an adverse impact on sleep in childhood CF (55). Differences in sleep/wake times among patients with CF and controls also have been proposed as a potential cause for inadequate sleep in this population (33), although this finding has not been universally supported (31, 32). A sleep phase delay has been recently identified among adults with CF, which the authors went on to speculate might be part of a larger circadian rhythm disturbance stemming from defective CFTR function in the hypothalamus (91). As none of the previous studies in this population have identified significant abnormalities in sleep/wake times or sleep latency (41, 42), more work is needed to determine whether patients with CF are truly at increased risk for a sleep phase delay or circadian rhythm disturbance.

Treatment of sleep disturbances

Given the strong associations between hypoxemia and the development of pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale, the primary goal of treatment in patients with CF has always been to correct the nocturnal hypoxemia. Several small single-night crossover studies, mostly in adults with CF, have demonstrated improvements in oxygen saturation during sleep following the use of nocturnal supplemental oxygen (45, 47, 58). However, this did not translate to better sleep efficiency or fewer arousals (47, 58).

A long-term, randomized trial of nocturnal supplemental oxygen among adults with CF all of whom had severe lung disease found similar mortality rates, lung function, nutritional status, frequency of hospitalizations and gas-exchange parameters between the oxygen versus room air groups (92). The groups did not differ in terms of mood, cognitive function and exercise capacity. Better school and work attendance was observed in the oxygen group as compared to the room air group (92). Although this difference was thought to have arisen from better sleep quality in the oxygen group, neither group underwent any formal sleep assessments. The use of nocturnal supplemental oxygen has been associated with an increase in CO2 levels. In all of the crossover studies, CO2 levels were higher with supplemental oxygen than on room air (45, 47, 58). Progressive hypercapnia has been reported among 34 adults with CF who were on supplemental oxygen for either daytime or nighttime hypoxemia, with approximately 35% requiring non-invasive positive pressure ventilation within 12 months (59). Patients with a baseline CO2 value > 49 mmHg were found to be most likely to develop progressive hypercapnia and fail oxygen therapy within a year (59).

Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) has proven effective in preventing the fall in minute ventilation from NREM to REM sleep in patients with CF (47). Direct comparisons of NIPPV to supplemental oxygen have found similar improvements in nocturnal oxygen saturations and a reduced incidence of hypercapnia (47, 58, 60). Patients with CF who are switched to NIPPV due to progressive hypercapnia also show an improvement in their CO2 levels (59). No improvements in total sleep time, sleep efficiency, or frequency of arousals have been documented with NIPPV (47, 58, 93), although the frequency of respiratory events during sleep might be lower on NIPPV than with supplemental oxygen or room air (47, 93). Improvements in exercise capacity, chest symptoms and dyspnea scores have also been shown with NIPPV use (60). Nonetheless, adherence to NIPPV is significantly lower than that to supplemental oxygen (4.3h vs 6.5h per night, respectively) (60). A long-term study of NIPPV in adults with CF found stabilization in the rate of lung function decline within the first year of use (94). Although the NIPPV group had experienced a greater decline in their lung function in the year prior to the study as compared to the non-NIPPV group and were potentially sicker, by year 1 of NIPPV use, the rate of decline in lung function was similar between the two groups (94).

Despite this encouraging evidence in support of the use of NIPPV among patients with CF, no guidelines exist on when to initiate this therapy. Interestingly, although positive airway pressure therapy is recommended for treatment of persistent OSA in children (71), this review did not uncover published data on the use of continuous positive airway pressure or NIPPV specifically for SDB in children or adults with CF. Results of a survey of medical providers in France found that NIPPV was being used among patients with CF during pulmonary exacerbations that were associated with severe hypercapnia or when evidence emerged for daytime hypercapnia (94). A different survey of pediatric specialists in the United Kingdom and Australia found that less than 5% of children with CF were being prescribed NIPPV (95). The median age of initiation was 14 years. As with the results from France, NIPPV was largely being used during acute pulmonary exacerbations, as a bridge to lung transplantation, or to promote airway clearance. Among the 36 centers that participated in the survey, only 17 performed polysomnography prior to initiation of NIPPV. The majority of centers used either pulse oximetry alone or in combination with capnometry to assess need for NIPPV (95). However, nocturnal hypoxemia and hypercapnia can precede the daytime gas-exchange abnormalities. Use of NIPPV may reverse some of these abnormalities, stabilize lung function, and slow down disease progression. Better guidelines are needed on when and how to screen patients with CF for sleep disorders and abnormalities in nocturnal gas-exchange.

Although children and adults with CF frequently complain of difficulties with initiation and maintenance of sleep, little information is available on medical management of these problems in patients with CF. As benzodiazepines can depress respiration, they should probably be used with caution in patients with CF. Zolpidem, a commonly used non-benzodiazepine hypnotic, has been associated with an increased risk of respiratory infections (96) and should also be used with caution. Melatonin has been used in healthy children to promote sleep and has proven to be efficacious in those with sleep phase delays (97). A randomized, double-blinded, placebo controlled trial of melatonin in children with CF demonstrated significant improvements in sleep efficiency, and a trend towards improvement in sleep-onset latency in the melatonin group (34). Given the potential for patients with CF to have sleep phase delays and other circadian rhythm disturbances, this is an area that warrants future study.

Future Directions and Implications for Clinical Practice

Sleep disruption is both significant and consequential among children with CF. Poor sleep has the potential to affect lung health, frequency of infective exacerbations, nutritional status, academic performance, mood, and quality of life in these children. Evidence suggests that children with CF in comparison to those without the disease have more sleep complaints and, possibly, a higher frequency of sleep disturbances. Patients with CF may be inherently at risk for sleep problems due to defective CFTR function in the hypothalamus and other areas that control the circadian rhythm. Yet, neither children nor adults with CF are routinely screened for the presence of sleep disorders. Despite the availability of validated screening tools for SDB (98) and other sleep disturbances in healthy children, none have been consistently applied among patients with CF.

Objective data on sleep in children with CF are limited and often conflicted. Growing evidence from other pediatric populations highlight the potential utility of certain advanced signal analysis techniques where standard polysomnography has been less informative (64–66, 99). A closer look at the microstructure of sleep, or an evaluation of dynamics of sleep-stage transitions, might provide better insight into sleep fragmentation among children with CF. This information could also be of value to clinicians as they decide which patients would benefit from further evaluation for sleep disturbances.

Although nocturnal derangements in gas-exchange have long been recognized to precede any daytime abnormalities, children with CF do not routinely undergo polysomnography or even overnight pulse oximetry monitoring to look for these pathologies. Given known links between low lung function and the risk for poor sleep quality and nocturnal hypoxemia, perhaps all children with CF who have an abnormal baseline FEV1 % predicted should be screened for sleep disturbances. Those who have a daytime resting oxygen saturation that is ≤ 94% may also benefit from this evaluation or at least overnight pulse oximetry monitoring to assess for nocturnal hypoxemia.

A paucity of data also exists with regard to treatment recommendations for children with CF who have sleep disorders. Despite the plethora of information on the benefits of adenotonsillectomy for the treatment of OSA in children, no one has systematically evaluated this in children with CF. Among otherwise healthy children, adenotonsillectomy has been shown to promote weight gain, and improve sleep quality, and quality of life (71). However, whether these same gains can be achieved in children with CF is remains unknown.

In general, better guidelines for screening children with CF for sleep disturbances and improved recommendations to help direct therapy for patients with sleep disorders are urgently needed. The latter is of particular importance as treating these problems may help to slow lung function decline, and improve health outcomes of patients with CF.

Practice Points.

Children with cystic fibrosis have complaints about their sleep, as well as poor sleep efficiency and frequent arousals on actigraphy and polysomnography

Nocturnal hypoxemia and hypercapnia occur frequently during sleep in patients with cystic fibrosis and can precede daytime gas-exchange abnormalities

The frequency of obstructive sleep apnea is high among young children with cystic fibrosis and is associated with lower nocturnal oxygen saturations

Clinical markers of cystic fibrosis disease severity, such as lung function and awake oxygen saturation, may help to identify patients at increased risk for sleep disorders

Research Agenda.

A more thorough understanding of sleep disturbances in patients with cystic fibrosis using a combination of standard polysomnography measures and more advanced, signal analysis techniques

Identifying which patients with cystic fibrosis might be at increased risk for sleep disorders. Are patients with more severe lung disease at higher risk? Are individuals with certain mutations more likely to experience sleep problems?

Evaluating the health impact of sleep disorders in patients with cystic fibrosis – effects on academic performance, mood, behavior, quality of life, infection risk, risk for cystic fibrosis-related diabetes, and disease-specific outcomes (lung function, frequency of pulmonary exacerbations)

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Shakkottai is supported by an NIH training grant, T32NS007222

Abbreviations:

- (CO2)

Carbon dioxide

- (CF)

Cystic fibrosis

- (CFRD)

Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes

- (CFTR)

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- (FEV1)

Forced expiratory volume in one second

- (NIPPV)

Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation

- (NREM)

Non-rapid eye movement

- (OSA)

Obstructive sleep apnea

- (REM)

Rapid eye movement

- (SDB)

Sleep-disordered breathing

- (WASO)

Wakefulness after sleep onset

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest pertinent to this review.

References

- 1.Owens J Classification and epidemiology of childhood sleep disorders. Prim Care. 2008;35(3):533–46, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Brien LM, Mervis CB, Holbrook CR, Bruner JL, Klaus CJ, Rutherford J, et al. Neurobehavioral implications of habitual snoring in children. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):44–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chervin RD, Ruzicka DL, Archbold KH, Dillon JE. Snoring predicts hyperactivity four years later. Sleep. 2005;28(7):885–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chervin RD, Ruzicka DL, Giordani BJ, Weatherly RA, Dillon JE, Hodges EK, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, behavior, and cognition in children before and after adenotonsillectomy. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):e769–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Brien LM. The neurocognitive effects of sleep disruption in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18(4):813–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Brien LM, Lucas NH, Felt BT, Hoban TF, Ruzicka DL, Jordan R, et al. Aggressive behavior, bullying, snoring, and sleepiness in schoolchildren. Sleep Med. 2011;12(7):652–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonuck K, Freeman K, Chervin RD, Xu L. Sleep-disordered breathing in a population-based cohort: behavioral outcomes at 4 and 7 years. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):e857–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Brien LM. Sleep-Related Breathing Disorder, Cognitive Functioning, and Behavioral-Psychiatric Syndromes in Children. Sleep Med Clin. 2015;10(2):169–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irwin MR. Why sleep is important for health: a psychoneuroimmunology perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:143–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park H, Tsai KM, Dahl RE, Irwin MR, McCreath H, Seeman TE, et al. Sleep and Inflammation During Adolescence. Psychosom Med. 2016;78(6):677–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez-Mendoza J, Baker JH, Vgontzas AN, Gaines J, Liao D, Bixler EO. Insomnia symptoms with objective short sleep duration are associated with systemic inflammation in adolescents. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;61:110–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kong AP, Wing YK, Choi KC, Li AM, Ko GT, Ma RC, et al. Associations of sleep duration with obesity and serum lipid profile in children and adolescents. Sleep Med. 2011;12(7):659–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonuck K, Chervin RD, Howe LD. Sleep-disordered breathing, sleep duration, and childhood overweight: a longitudinal cohort study. J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):632–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koren D, Gozal D, Philby MF, Bhattacharjee R, Kheirandish-Gozal L. Impact of obstructive sleep apnoea on insulin resistance in nonobese and obese children. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(4):1152–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudnicka AR, Nightingale CM, Donin AS, Sattar N, Cook DG, Whincup PH, et al. Sleep Duration and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Splaingard ML. Sleep Problems in Children with Respiratory Disorders. Sleep Medicine Clinics. 2008;3(4):589–600. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry 2016 Annual Data Report. . Bethesda, Maryland: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elborn JS. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2016;388(10059):2519–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harun SN, Wainwright C, Klein K, Hennig S. A systematic review of studies examining the rate of lung function decline in patients with cystic fibrosis. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2016;20:55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moheet A, Moran A. CF-related diabetes: Containing the metabolic miscreant of cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52(S48):S37–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziegler B, Perin C, Casarotto FC, Fagondes SC, Menna-Barreto SS, Dalcin PT. Pulmonary hypertension as estimated by Doppler echocardiography in adolescent and adult patients with cystic fibrosis and their relationship with clinical, lung function and sleep findings. Clin Respir J. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reznikov LR. Cystic Fibrosis and the Nervous System. Chest. 2017;151(5):1147–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akerstedt T, Ghilotti F, Grotta A, Bellavia A, Lagerros YT, Bellocco R. Sleep duration, mortality and the influence of age. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(10):881–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amin R, Bean J, Burklow K, Jeffries J. The relationship between sleep disturbance and pulmonary function in stable pediatric cystic fibrosis patients. Chest. 2005;128(3):1357–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naqvi SK, Sotelo C, Murry L, Simakajornboon N. Sleep architecture in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis and the association with severity of lung disease. Sleep Breath. 2008;12(1):77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silva AM, Descalco A, Salgueiro M, Pereira L, Barreto C, Bandeira T, et al. Respiratory sleep disturbance in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Rev Port Pneumol (2006). 2016;22(4):202–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waters KA, Lowe A, Cooper P, Vella S, Selvadurai H. A cross-sectional analysis of daytime versus nocturnal polysomnographic respiratory parameters in cystic fibrosis during early adolescence. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16(2):250–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cepuch G, Gniadek A, Gustyn A, Tomaszek L. Emotional states and sleep disorders in adolescent and young adult cystic fibrosis patients. Folia Med Cracov. 2017;57(4):27–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomaszek L, Cepuch G, Pawlik L. The evaluation of selected insomnia predictors in adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fauroux B, Pepin JL, Boelle PY, Cracowski C, Murris-Espin M, Nove-Josserand R, et al. Sleep quality and nocturnal hypoxaemia and hypercapnia in children and young adults with cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(11):960–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vandeleur M, Walter LM, Armstrong DS, Robinson P, Nixon GM, Horne RS. How Well Do Children with Cystic Fibrosis Sleep? An Actigraphic and Questionnaire-Based Study. J Pediatr. 2017;182:170–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vandeleur M, Walter LM, Armstrong DS, Robinson P, Nixon GM, Horne RSC. Quality of life and mood in children with cystic fibrosis: Associations with sleep quality. J Cyst Fibros. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meltzer LJ, Beck SE. Sleep Patterns in Children with Cystic Fibrosis. Child Health Care. 2012;41(3):260–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Castro-Silva C, de Bruin VM, Cunha GM, Nunes DM, Medeiros CA, de Bruin PF. Melatonin improves sleep and reduces nitrite in the exhaled breath condensate in cystic fibrosis--a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Pineal Res. 2010;48(1):65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suratwala D, Chan JS, Kelly A, Meltzer LI, Gallagher PR, Traylor J, et al. Nocturnal saturation and glucose tolerance in children with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2011;66(7):574–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spicuzza L, Sciuto C, Leonardi S, La Rosa M. Early occurrence of obstructive sleep apnea in infants and children with cystic fibrosis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1165–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villa MP, Pagani J, Lucidi V, Palamides S, Ronchetti R. Nocturnal oximetry in infants with cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84(1):50–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Castro-Silva C, de Bruin VM, Cavalcante AG, Bittencourt LR, de Bruin PF. Nocturnal hypoxia and sleep disturbances in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44(11):1143–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paranjape SM, McGinley BM, Braun AT, Schneider H. Polysomnographic Markers in Children With Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):920–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schluchter MD, Konstan MW, Drumm ML, Yankaskas JR, Knowles MR. Classifying severity of cystic fibrosis lung disease using longitudinal pulmonary function data. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(7):780–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perin C, Fagondes SC, Casarotto FC, Pinotti AF, Menna Barreto SS, Dalcin Pde T. Sleep findings and predictors of sleep desaturation in adult cystic fibrosis patients. Sleep Breath. 2012;16(4):1041–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jankelowitz L, Reid KJ, Wolfe L, Cullina J, Zee PC, Jain M. Cystic fibrosis patients have poor sleep quality despite normal sleep latency and efficiency. Chest. 2005;127(5):1593–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Milross MA, Piper AJ, Norman M, Dobbin CJ, Grunstein RR, Sullivan CE, et al. Subjective sleep quality in cystic fibrosis. Sleep Med. 2002;3(3):205–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bradley S, Solin P, Wilson J, Johns D, Walters EH, Naughton MT. Hypoxemia and hypercapnia during exercise and sleep in patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest. 1999;116(3):647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spier S, Rivlin J, Hughes D, Levison H. The effect of oxygen on sleep, blood gases, and ventilation in cystic fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129(5):712–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tepper RS, Skatrud JB, Dempsey JA. Ventilation and oxygenation changes during sleep in cystic fibrosis. Chest. 1983;84(4):388–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Milross MA, Piper AJ, Norman M, Becker HF, Willson GN, Grunstein RR, et al. Low-flow oxygen and bilevel ventilatory support: effects on ventilation during sleep in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(1):129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muller NL, Francis PW, Gurwitz D, Levison H, Bryan AC. Mechanism of hemoglobin desaturation during rapid-eye-movement sleep in normal subjects and in patients with cystic fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;121(3):463–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Francis PW, Muller NL, Gurwitz D, Milligan DW, Levison H, Bryan AC. Hemoglobin desaturation: its occurrence during sleep in patients with cystic fibrosis. Am J Dis Child. 1980;134(8):734–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramos RT, Santana MA, Almeida Pde C, Machado Jr Ade S, Araujo-Filho JB, Salles C. Nocturnal hypoxemia in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2013;39(6):667–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van der Giessen L, Bakker M, Joosten K, Hop W, Tiddens H. Nocturnal oxygen saturation in children with stable cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47(11):1123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Versteegh FG, Bogaard JM, Raatgever JW, Stam H, Neijens HJ, Kerrebijn KF. Relationship between airway obstruction, desaturation during exercise and nocturnal hypoxaemia in cystic fibrosis patients. Eur Respir J. 1990;3(1):68–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frangolias DD, Wilcox PG. Predictability of oxygen desaturation during sleep in patients with cystic fibrosis : clinical, spirometric, and exercise parameters. Chest. 2001;119(2):434–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uyan ZS, Ozdemir N, Ersu R, Akpinar I, Keskin S, Cakir E, et al. Factors that correlate with sleep oxygenation in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42(8):716–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vandeleur M, Walter LM, Armstrong DS, Robinson P, Nixon GM, Horne RSC. What keeps children with cystic fibrosis awake at night? J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16(6):719–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dancey DR, Tullis ED, Heslegrave R, Thornley K, Hanly PJ. Sleep quality and daytime function in adults with cystic fibrosis and severe lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(3):504–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Milross MA, Piper AJ, Norman M, Willson GN, Grunstein RR, Sullivan CE, et al. Predicting sleep-disordered breathing in patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2001;120(4):1239–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gozal D Nocturnal ventilatory support in patients with cystic fibrosis: comparison with supplemental oxygen. Eur Respir J. 1997;10(9):1999–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dobbin CJ, Milross MA, Piper AJ, Sullivan C, Grunstein RR, Bye PT. Sequential use of oxygen and bi-level ventilation for respiratory failure in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2004;3(4):237–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Young AC, Wilson JW, Kotsimbos TC, Naughton MT. Randomised placebo controlled trial of non-invasive ventilation for hypercapnia in cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2008;63(1):72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramos RT, Salles C, Gregorio PB, Barros AT, Santana A, Araujo-Filho JB, et al. Evaluation of the upper airway in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(12):1780–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramos RT, Salles C, Daltro CH, Santana MA, Gregorio PB, Acosta AX. Sleep architecture and polysomnographic respiratory profile of children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2011;87(1):63–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Veronezi J, Carvalho AP, Ricachinewsky C, Hoffmann A, Kobayashi DY, Piltcher OB, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2015;41(4):351–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chervin RD, Burns JW, Subotic NS, Roussi C, Thelen B, Ruzicka DL. Correlates of respiratory cycle-related EEG changes in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep. 2004;27(1):116–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chervin RD, Burns JW, Ruzicka DL. Electroencephalographic changes during respiratory cycles predict sleepiness in sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(6):652–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Immanuel SA, Pamula Y, Kohler M, Martin J, Kennedy D, Saint DA, et al. Respiratory cycle-related electroencephalographic changes during sleep in healthy children and in children with sleep disordered breathing. Sleep. 2014;37(8):1353–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yin J, Jin X, Shan Z, Li S, Huang H, Li P, et al. Relationship of Sleep Duration With All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hershner SD, Chervin RD. Causes and consequences of sleepiness among college students. Nat Sci Sleep. 2014;6:73–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Landau YE, Bar-Yishay O, Greenberg-Dotan S, Goldbart AD, Tarasiuk A, Tal A. Impaired behavioral and neurocognitive function in preschool children with obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47(2):180–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moyer CA, Sonnad SS, Garetz SL, Helman JI, Chervin RD. Quality of life in obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review of the literature. Sleep Med. 2001;2(6):477–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dehlink E, Tan HL. Update on paediatric obstructive sleep apnoea. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(2):224–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Piasecki B, Stanislawska-Kubiak M, Strzelecki W, Mojs E. Attention and memory impairments in pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis and inflammatory bowel disease in comparison to healthy controls. J Investig Med. 2017;65(7):1062–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Piasecki B, Turska-Malinska R, Matthews-Brzozowska T, Mojs E. Executive function in pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis, inflammatory bowel disease and in healthy controls. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(20):4299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dobbin CJ, Bartlett D, Melehan K, Grunstein RR, Bye PT. The effect of infective exacerbations on sleep and neurobehavioral function in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(1):99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bouka A, Tiede H, Liebich L, Dumitrascu R, Hecker C, Reichenberger F, et al. Quality of life in clinically stable adult cystic fibrosis out-patients: associations with daytime sleepiness and sleep quality. Respir Med. 2012;106(9):1244–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Forte GC, Barni GC, Perin C, Casarotto FC, Fagondes SC, Dalcin Pde T. Relationship Between Clinical Variables and Health-Related Quality of Life in Young Adult Subjects With Cystic Fibrosis. Respir Care. 2015;60(10):1459–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cavanaugh K, Read L, Dreyfus J, Johnson M, McNamara J. Association of poor sleep with behavior and quality of life in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2016;14(2):199–204. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kamath KS, Krisp C, Chick J, Pascovici D, Gygi SP, Molloy MP. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Proteome under Hypoxic Stress Conditions Mimicking the Cystic Fibrosis Lung. J Proteome Res. 2017;16(10):3917–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McColley SA, Schechter MS, Morgan WJ, Pasta DJ, Craib ML, Konstan MW. Risk factors for mortality before age 18 years in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52(7):909–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van der Giessen L, Loeve M, de Jongste J, Hop W, Tiddens H. Nocturnal cough in children with stable cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44(9):859–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kent BD, Lane SJ, van Beek EJ, Dodd JD, Costello RW, Tiddens HA. Asthma and cystic fibrosis: a tangled web. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49(3):205–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schwarzenberg SJ, Hempstead SE, McDonald CM, Powers SW, Wooldridge J, Blair S, et al. Enteral tube feeding for individuals with cystic fibrosis: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation evidence-informed guidelines. J Cyst Fibros. 2016;15(6):724–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Blackwell LS, Quittner AL. Daily pain in adolescents with CF: Effects on adherence, psychological symptoms, and health-related quality of life. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sermet-Gaudelus I, De Villartay P, de Dreuzy P, Clairicia M, Vrielynck S, Canoui P, et al. Pain in children and adults with cystic fibrosis: a comparative study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(2):281–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lechtzin N, Allgood S, Hong G, Riekert K, Haythornthwaite JA, Mogayzel P, et al. The Association Between Pain and Clinical Outcomes in Adolescents With Cystic Fibrosis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(5):681–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maqbool A, Pauwels A. Cystic Fibrosis and gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16 Suppl 2:S2–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Robinson NB, DiMango E. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in cystic fibrosis and implications for lung disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(6):964–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Halpern LM, Jolley SG, Tunell WP, Johnson DG, Sterling CE. The mean duration of gastroesophageal reflux during sleep as an indicator of respiratory symptoms from gastroesophageal reflux in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26(6):686–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Machado R, Woodley FW, Skaggs B, Di Lorenzo C, Splaingard M, Mousa H. Gastroesophageal reflux causing sleep interruptions in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56(4):431–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Allen JM, Graef DM, Ehrentraut JH, Tynes BL, Crabtree VM. Sleep and Pain in Pediatric Illness: A Conceptual Review. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016;22(11):880–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jensen JL, Jones CR, Kartsonaki C, Packer KA, Adler FR, Liou TG. Sleep Phase Delay in Cystic Fibrosis: A Potential New Manifestation of Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Regulator Dysfunction. Chest. 2017;152(2):386–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zinman R, Corey M, Coates AL, Canny GJ, Connolly J, Levison H, et al. Nocturnal home oxygen in the treatment of hypoxemic cystic fibrosis patients. J Pediatr. 1989;114(3):368–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Regnis JA, Piper AJ, Henke KG, Parker S, Bye PT, Sullivan CE. Benefits of nocturnal nasal CPAP in patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest. 1994;106(6):1717–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fauroux B, Le Roux E, Ravilly S, Bellis G, Clement A. Long-term noninvasive ventilation in patients with cystic fibrosis. Respiration. 2008;76(2):168–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Collins N, Gupta A, Wright S, Gauld L, Urquhart D, Bush A. Survey of the use of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation in U.K. and Australasian children with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2011;66(6):538–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Huang CY, Chou FH, Huang YS, Yang CJ, Su YC, Juang SY, et al. The association between zolpidem and infection in patients with sleep disturbance. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;54:116–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cummings C, Canadian Paediatric Society CPC. Melatonin for the management of sleep disorders in children and adolescents. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;17(6):331–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chervin RD, Hedger K, Dillon JE, Pituch KJ. Pediatric sleep questionnaire (PSQ): validity and reliability of scales for sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, sleepiness, and behavioral problems. Sleep Med. 2000;1(1):21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chervin RD, Fetterolf JL, Ruzicka DL, Thelen BJ, Burns JW. Sleep stage dynamics differ between children with and without obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2009;32(10):1325–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]