Legumes share a unique association with certain soil-dwelling bacteria known broadly as rhizobia. Through concerted interorganismal communication, a legume allows intracellular infection by its cognate rhizobial species. The plant then forms an organ, the root nodule, dedicated to housing and supplying fixed carbon and nutrients to the bacteria. In return, the engulfed rhizobia, differentiated into bacteroids, fix atmospheric N2 into ammonium for the plant host. This interplay is of great benefit to the cultivation of legumes, such as alfalfa and soybeans, and is initiated by chemotaxis to the host plant. This study on carboxylate chemotaxis contributes to the understanding of rhizobial survival and competition in the rhizosphere and aids the development of commercial inoculants.

KEYWORDS: chemotaxis, plant host exudate, motility, rhizosphere, symbiosis

ABSTRACT

Sinorhizobium meliloti is a soil-dwelling endosymbiont of alfalfa that has eight chemoreceptors to sense environmental stimuli during its free-living state. The functions of two receptors have been characterized, with McpU and McpX serving as general amino acid and quaternary ammonium compound sensors, respectively. Both receptors use a dual Cache (calcium channels and chemotaxis receptors) domain for ligand binding. We identified that the ligand-binding periplasmic region (PR) of McpV contains a single Cache domain. Homology modeling revealed that McpVPR is structurally similar to a sensor domain of a chemoreceptor with unknown function from Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans, which crystallized with acetate in its binding pocket. We therefore assayed McpV for carboxylate binding and S. meliloti for carboxylate sensing. Differential scanning fluorimetry identified 10 potential ligands for McpVPR. Nine of these are monocarboxylates with chain lengths between two and four carbons. We selected seven compounds for capillary assay analysis, which established positive chemotaxis of the S. meliloti wild type, with concentrations of peak attraction at 1 mM for acetate, propionate, pyruvate, and glycolate, and at 100 mM for formate and acetoacetate. Deletion of mcpV or mutation of residues essential for ligand coordination abolished positive chemotaxis to carboxylates. Using microcalorimetry, we determined that dissociation constants of the seven ligands with McpVPR were in the micromolar range. An McpVPR variant with a mutation in the ligand coordination site displayed no binding to isobutyrate or propionate. Of all the carboxylates tested as attractants, only glycolate was detected in alfalfa seed exudates. This work examines the relevance of carboxylates and their sensor to the rhizobium-legume interaction.

IMPORTANCE Legumes share a unique association with certain soil-dwelling bacteria known broadly as rhizobia. Through concerted interorganismal communication, a legume allows intracellular infection by its cognate rhizobial species. The plant then forms an organ, the root nodule, dedicated to housing and supplying fixed carbon and nutrients to the bacteria. In return, the engulfed rhizobia, differentiated into bacteroids, fix atmospheric N2 into ammonium for the plant host. This interplay is of great benefit to the cultivation of legumes, such as alfalfa and soybeans, and is initiated by chemotaxis to the host plant. This study on carboxylate chemotaxis contributes to the understanding of rhizobial survival and competition in the rhizosphere and aids the development of commercial inoculants.

INTRODUCTION

Motility and navigation are two behaviors that bacteria exhibit to choose an optimal environment for survival and growth. Flagellum-driven motility is regulated by a finely tuned sensory array and a two-component signal transduction system that ultimately controls flagellar motor rotation. In Escherichia coli, the initial step in sensing is the binding of a ligand to its cognate methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein (MCP). Ligand binding typically occurs in the periplasmic region (PR) of the chemoreceptor, initiating a molecular stimulus that is transferred through the cytoplasmic membrane. Upon attractant binding, autophosphorylation of the histidine kinase CheA is inhibited. Consequently, the corresponding response regulator, CheY, remains unphosphorylated and inactive, leading to unaltered flagellar motor rotation and a smooth swimming path of the cell. In the absence of ligand binding, CheA phosphorylates and activates CheY, which will bind to the flagellar motor and induce a tumble behavior. During tumbles, the bacterium can randomly reorient to a new direction. This behavior, called a biased random walk, allows the bacterium to swim toward attractants and away from repellents (1–4).

The genomes of bacteria are expected to contain various numbers and types of chemoreceptors that reflect their niche and lifestyle requirements. Denizens of static environments and simple niches are found to have few to no chemoreceptors, while those that share a complex interplay with other organisms or have diverse metabolic capabilities encode far more chemoreceptors in their genomes (4–6). The Alphaproteobacteria typify the latter case, with organisms such as Azospirillum lipoferum, Bradyrhizobium sp. strain BTAi1, and Rhizobium phaseoli containing 63, 60, and 29 predicted chemoreceptors, respectively (7). These organisms colonize the roots of plants and promote plant growth by fixing atmospheric nitrogen and outcompeting plant pathogens. Within the Alphaproteobacteria is the Rhizobiaceae, a bacterial family that forms a species-specific endosymbiosis with members of the Fabaceae plant family. The rhizobium and plant host communicate and undergo highly specific developmental changes that ultimately lead to the formation of a root organ called a nodule. Within these nodules, differentiated bacteroids occupy membranous organelles inside host cells, and the plant provides metabolizable carbon sources to the bacteroids to fuel the fixation of nitrogen gas to ammonium (8–12).

Sinorhizobium (Ensifer) meliloti is the cognate symbiont for alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.), an important forage crop of which the United States produced over 58 million tons in 2016 (13). Alfalfa and other legumes capable of nitrogen-fixing symbiosis can be grown largely free of costly and environmentally deleterious nitrogenous fertilizers that may leach into neighboring ecosystems (14). Plants recruit S. meliloti and other soil microorganisms to the rhizosphere with the plethora of chemicals exuded from the roots. These compounds include amino acids, quaternary ammonium compounds, sugars, and organic acids, to name a few. While not directly involved in the symbiotic process, chemotaxis is critical to competition for root nodule occupancy (7, 15–22).

Nine putative chemoreceptors, namely, McpS through McpZ, and the internal chemoreceptor IcpA are encoded in the genomes of most S. meliloti strains. Previous studies have demonstrated that mcpS was not expressed when cells were motile and chemotactically active. Therefore, it was concluded that McpS is utilized in cellular processes other than chemotaxis (23, 24). The functions of two of the eight chemoreceptors involved in S. meliloti chemotaxis have been elucidated. McpU is a general amino acid receptor, sensing all nonacidic proteogenic amino acids, as well as several nonproteogenic amino acids (16, 25). McpX senses quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs), such as glycine betaine, trigonelline, and choline, through direct binding, and it is the first QAC chemoreceptor described in bacteria (17). Amino acids and QACs are exuded by germinating alfalfa seeds in chemotactically relevant concentrations (15, 17). The PR of McpU and McpX both contain a dCache_1 (dual calcium channels and chemotaxis receptors) domain. The interaction of Cache domains with small molecules is well described. A major fraction of extracellular sensors in prokaryotes employ Cache domains (16, 17, 26–31). Besides McpU and McpX, S. meliloti possesses a third Cache domain containing the chemoreceptor McpV, which has an sCache_2 (single Cache) domain in its PR.

In this work, we screened the ligand profile of the purified McpV periplasmic region (McpVPR) and characterized ligand interaction in direct binding studies. Chemotaxis of S. meliloti wild-type but not mcpV mutant strains to various carboxylates was established with traditional capillary assays, confirming the role of McpV as a carboxylate sensor. We hypothesized that carboxylate exudation by alfalfa recruits its symbiont to the rhizosphere, which was tested by quantifying these compounds in germinating alfalfa seed exudates. The knowledge accrued from this study establishes short-chain carboxylates as another facet of the legume-rhizobium interplay and will inform future research on improving legume symbiosis for the benefit of agriculture.

RESULTS

A structure-based homology search suggests interaction of McpV with acetate.

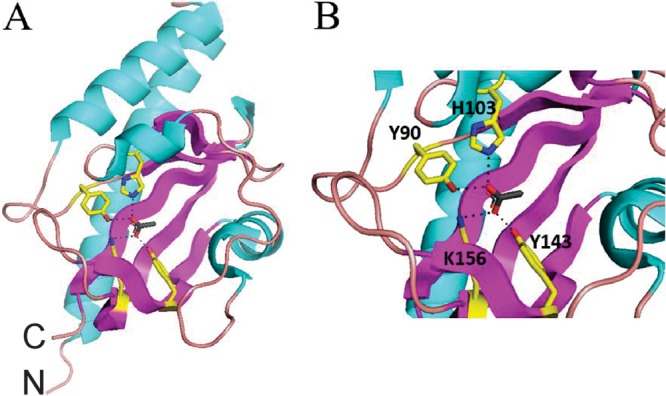

The periplasmic region of McpV (McpVPR) encompasses a conserved sCache (single calcium channels and chemotaxis receptors) signaling domain (27) (amino acid residues 35 to 177; see references 23 and 24). A homology search in the SWISS-MODEL repository revealed that McpVPR shares sequence identity (53.6%) with the sensor domain of Adeh_3718, an uncharacterized chemoreceptor from Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans. (32). SWISS-MODEL generated a structural model of McpVPR using the PR of Adeh_3718 (PDB entry 4K08 [32]). The global mean quality estimate is 0.75, indicating a high-quality model. The PR of Adeh_3718 was crystallized in complex with acetate, suggesting that McpVPR might also bind acetate. In the Adeh_3718 structure, the carboxylate group of acetate forms salt bridges to the side chains of His107 and Lys160, and hydrogen bonds are found with the side chains of Tyr94 and Tyr147. In the homology model of McpVPR, these four ligand-coordinating residues are conserved with the corresponding residues in McpV being identified as His103, Lys156, Tyr90, and Tyr143 (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Homology model of McpVPR using Adeh_3718 (PDB entry 4K08) as a template. Sequence identity over the modeled range is 54%, and the global model quality estimation (GMQE) value is 0.75. (A) Whole-model view. C, C terminus; N, N terminus. (B) Closeup view of the binding pocket, displaying acetate coordination. Residues in close proximity to the ligand are drawn with yellow carbon chains, red oxygen atoms, and blue nitrogen atoms. The dotted lines indicate possible ligand-coordinating bonds to Y90 and H103, which are closest to the upper half of the carboxylate, while K156 and Y143 are closer to the lower half of the carboxylate.

A high-throughput differential scanning fluorimetry assay screens the putative ligand profile of McpV.

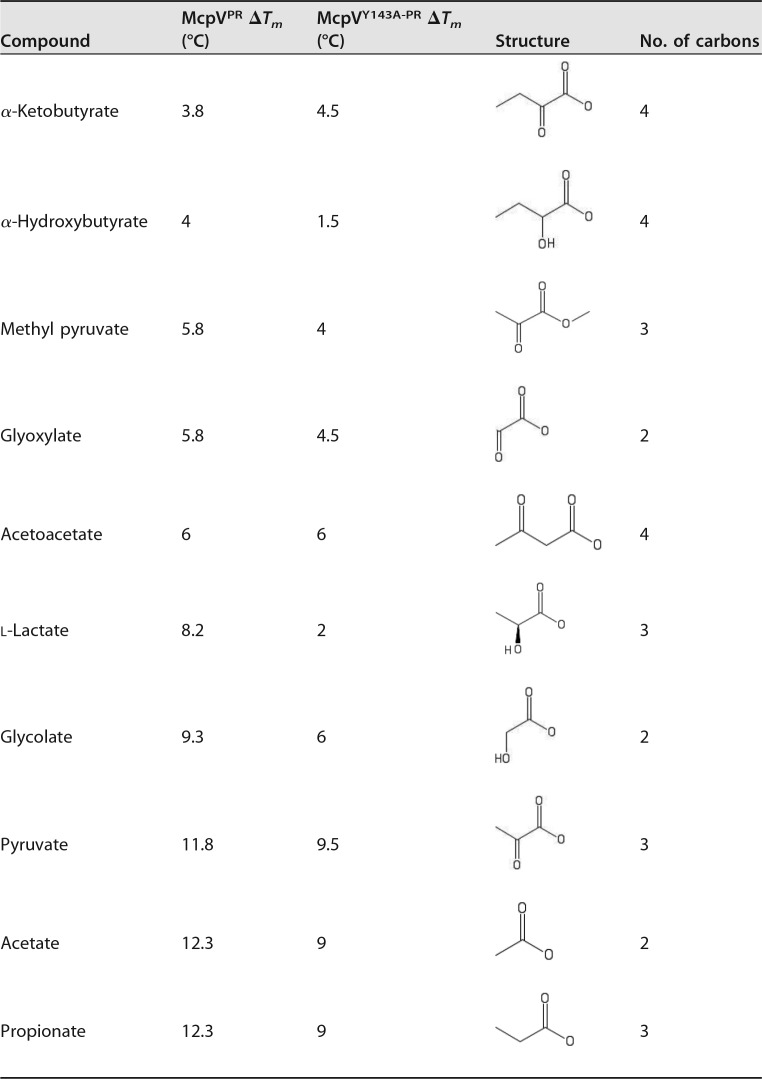

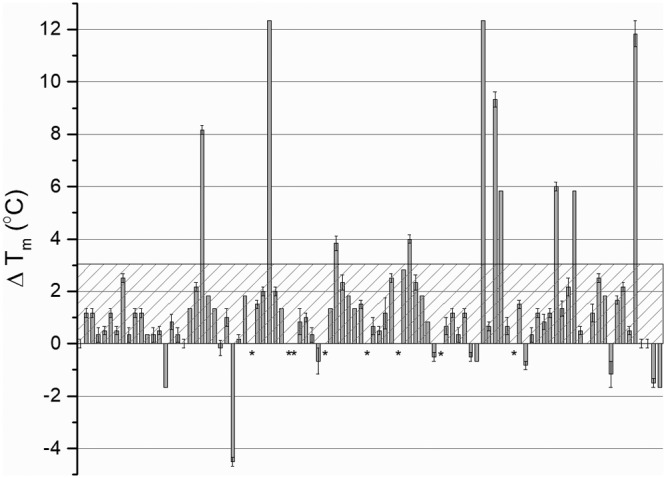

The discovery of acetate in the binding pocket of the homology model suggests carboxylates as possible ligands for McpV. To investigate this possibility, a high-throughput in vitro differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) assay was used to screen the ligand profile of recombinantly expressed and purified McpVPR. A Biolog PM1 plate was used for this screen because it contains a range of carbon sources, such as sugars, carboxylates, nucleotides, detergents, and amino acids (16, 33). The melting temperature (Tm) of the McpVPR in the presence of most compounds was within 2°C of the water control (57°C), and therefore an interaction was defined as a Tm shift greater than 3°C. The screen identified 10 compounds that interacted with McpVPR in monophasic melting reactions (Fig. 2; Table 1). With the exception of methyl pyruvate, all of these compounds are monocarboxylates with chain lengths between two and four carbons. With a ΔTm of 12.3°C, acetate and propionate elicited the greatest thermal shifts. Pyruvate caused the third greatest shift (11.8°C), while glycolate and l-lactate shifted the Tm by 9.3 and 8.2°C, respectively. Acetoacetate, a four-carbon carboxylate, produced the next greatest shift (6.0°C), followed by glyoxylate and methyl pyruvate, the latter being the only ester that caused a significant shift. Finally, α-hydroxybutyrate and α-ketobutyrate elicited the two lowest shifts, 4.0 and 3.8°C, respectively.

FIG 2.

High-throughput DSF screen with Biolog PM1 plate. The ΔTm is the change in thermal stability of recombinant McpVPR in the presence of a compound. The hatched box represents the threshold for a positive interaction. Values above the threshold indicate possible ligand interaction with the protein. Asterisks indicate that no Tm could be deduced from the melting curves. Values are the means and standard deviations from three technical replicates.

TABLE 1.

Compounds that caused the greatest shifts in melting temperature of McpVPR in the thermal denaturation assaya

The structure and length of the carbon chain are provided for comparison. Compounds are sorted according to ascending Tm values of the wild-type protein.

Since Tyr143 is one of the four key residues presumably involved in ligand coordination, we screened the purified McpVY143A-PR variant for its interaction with small molecules using a Biolog PM1 plate. The most drastic change was the reduction of the melting temperature in the absence of a putative ligand from 57 to 42.5°C. The overall ranking of molecules by ΔTm was somewhat maintained (Table 1). Acetate, propionate, and pyruvate induced the three greatest ΔTm of 9.0, 9.0, and 9.5°C, respectively, compared to the approximate 12.0°C shift for each with the wild-type protein. The shift caused by glycolate also decreased from 9.3 to 6.0°C. The shift produced by acetoacetate was 6°C for both the variant and wild-type proteins. The shift elicited by l-lactate was severely reduced from 11.8°C with the wild-type protein to 2.0°C with the variant protein. Glyoxylate and methyl pyruvate caused shifts of 4.5 and 4.0°C, respectively, reduced from approximately 6.0°C compared to that of the wild-type protein. The only carboxylate to cause a greater shift in the substitution variant than in the wild-type protein was α-ketobutyrate, which increased from 3.8°C in the wild-type protein to 4.5°C in the mutant variant. Lastly, α-hydroxybutyrate produced an insignificant shift of 1.5°C with the mutant variant compared to 4°C with the wild-type protein (Table 1).

In conclusion, carboxylates with two to four carbons interact with McpVPR, with the two- and three-carbon carboxylates causing a larger temperature shift than the four-carbon carboxylates. When Tyr143 is substituted for alanine, the stabilizing effect of many of the compounds tested was greatly reduced, implicating this residue in small-molecule interaction.

Chemotaxis of the S. meliloti wild type to carboxylates.

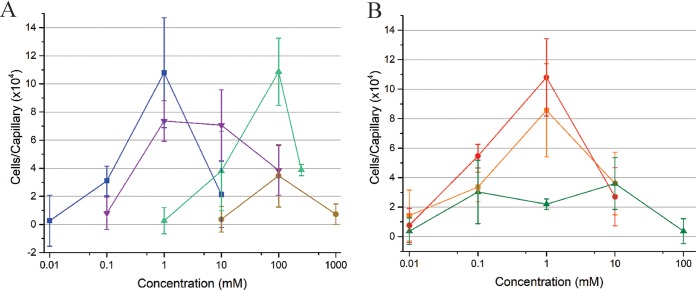

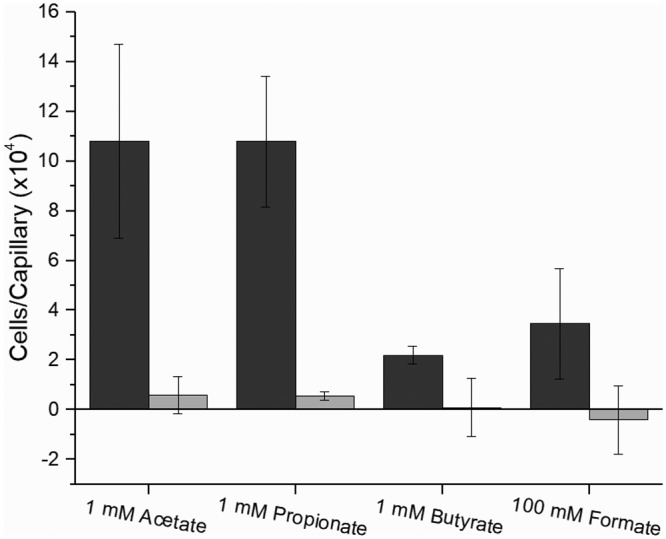

The ultimate reaction that results from ligand-chemoreceptor interaction is the translocation of the bacterium to the source of attractants or away from repellents. The traditional capillary assay allows for chemotactic responses to be quantified and classified (34). Formate, acetate, propionate, and butyrate were all tested to compare the simplest carboxylates of each chain length. Pyruvate, glycolate, and acetoacetate are of physiological relevance and were tested to compare the effects of their different functional groups. Each compound elicited a dose-dependent reaction curve from the S. meliloti wild-type strain (RU11/001) that peaked and subsequently declined, as is characteristic of an attractant chemotactic behavior (Fig. 3). S. meliloti was attracted to acetate, propionate, pyruvate, and glycolate, with a peak attraction at 1 mM and with glycolate also recruiting nearly as many bacteria at 10 mM. The response curve to butyrate formed a broad plateau between 0.1 and 10 mM. Attraction to formate peaked at 100 mM but dropped to near zero at the two flanking concentrations tested. Attraction to acetoacetate was also highest at 100 mM, but its curve shared the profile of acetate and pyruvate rather than that of formate. When comparing accumulation of cells, acetate, propionate, and acetoacetate were the most potent attractants, drawing around 110,000 cells to the capillary. Pyruvate and glycolate followed, with 85,000 and 74,000 cells, respectively. Formate and butyrate ranked last, accumulating only 35,000 to 36,000 cells per capillary on average (Fig. 3). To attribute the observed accumulation of bacteria to chemotaxis, a strain lacking all nine chemoreceptors, RU13/149, was tested in the chemotaxis assay at concentrations of peak attraction for four representative compounds, namely, formate, acetate, propionate, and butyrate (Fig. 4). As predicted, chemotaxis to each of the four compounds tested was completely abolished (Fig. 4). Together, these data demonstrate that one- to four-carbon carboxylates are chemoattractants for S. meliloti.

FIG 3.

S. meliloti wild-type chemotaxis responses to carboxylates in the capillary assay. (A) Dose-response curves for acetate (blue), glycolate (violet), acetoacetate (green), and formate (brown). The last data point of the acetoacetate curve corresponds to a concentration of 250 mM. (B) Dose-response curves for propionate (red), pyruvate (orange), and butyrate (green). The numbers of bacteria accumulated in control capillaries are subtracted from those in the test capillaries to account for random movement of bacteria into capillaries. Values are the means and standard deviations from three biological replicates.

FIG 4.

Chemotaxis responses of S. meliloti wild type (black) and a strain lacking all nine chemoreceptors (che; gray) to carboxylates in the capillary assay at peak concentrations of attraction. Chemotaxis data of the wild-type response are taken from Fig. 3. Values are the means and standard deviations from three biological replicates.

McpV mediates carboxylate chemotaxis in S. meliloti.

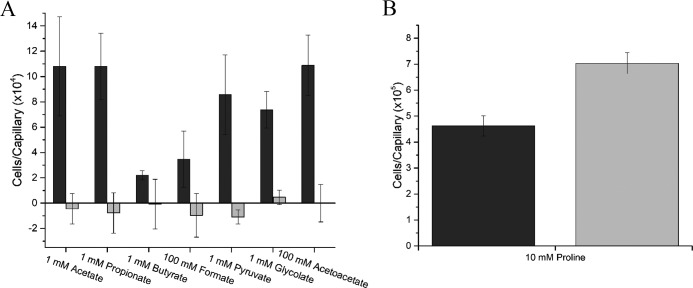

The DSF analysis identified McpV as a potential chemoreceptor for carboxylates. To assess the impact of mcpV on carboxylate chemotaxis, a strain lacking mcpV, RU11/830, was tested at concentrations of peak attraction for all seven carboxylates (Fig. 5A). In the absence of mcpV, chemotaxis to carboxylates was not detected. We next verified that the deletion of mcpV had no negative impact on chemotaxis in general. When proline chemotaxis was compared for the wild type and mcpV deletion strains, no reduction of proline attraction was observed. It should be noted that chemotaxis to 10 mM proline was improved by 1.5-fold in the absence of mcpV. For comparison to carboxylate taxis, chemotaxis of S. meliloti wild type to 10 mM l-proline drew about 460,000 bacteria to the capillary, which was more than four times that of any of the carboxylates (Fig. 5B). Therefore, carboxylates are less effective as attractants than proline.

FIG 5.

Chemotaxis responses of S. meliloti wild type (black) and a strain lacking mcpV (gray) in the capillary assay. (A) Chemotaxis responses of the wild type and ΔmcpV to the peak concentration of acetate, propionate, butyrate, formate, pyruvate, glycolate, and acetoacetate. Chemotaxis data of the wild-type response is taken from Fig. 3. (B) Chemotaxis responses of the wild type and ΔmcpV to 10 mM proline. Note the difference in scale between panels A and B. Values are the means and standard deviations from three biological replicates.

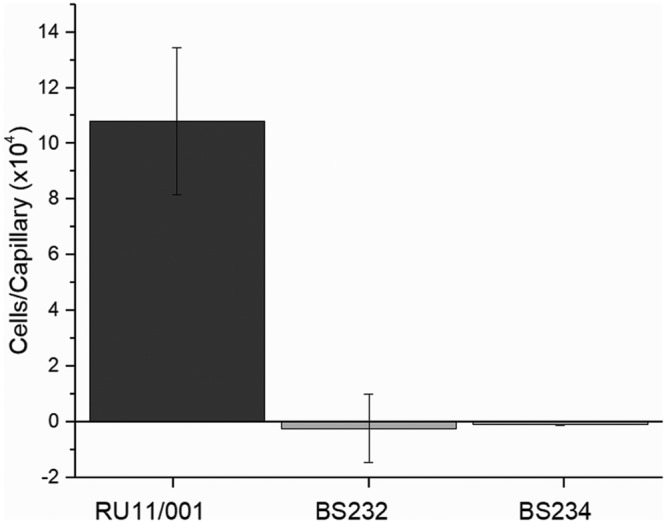

The homology model of McpVPR revealed several conserved residues that appear to play a role in ligand binding. To test the role of two of these residues, S. meliloti strains harboring a Y143A (BS232) or H103E (BS234) substitution in McpV were constructed and tested in the capillary assay. Neither mutant strain exhibited any chemotaxis to 1 mM propionate, establishing a role of mcpV in carboxylate chemotaxis in S. meliloti (Fig. 6). In addition, residues Tyr143 and His103 are essential components of the McpV ligand-binding pocket.

FIG 6.

S. meliloti wild-type, BS232 (McpVY143A), and BS234 (McpVH103E) chemotaxis responses to 1 mM propionate in the capillary assay. Chemotaxis data of the wild-type response is taken from Fig. 3. Values of the mutant responses are the means and standard deviations from two biological replicates.

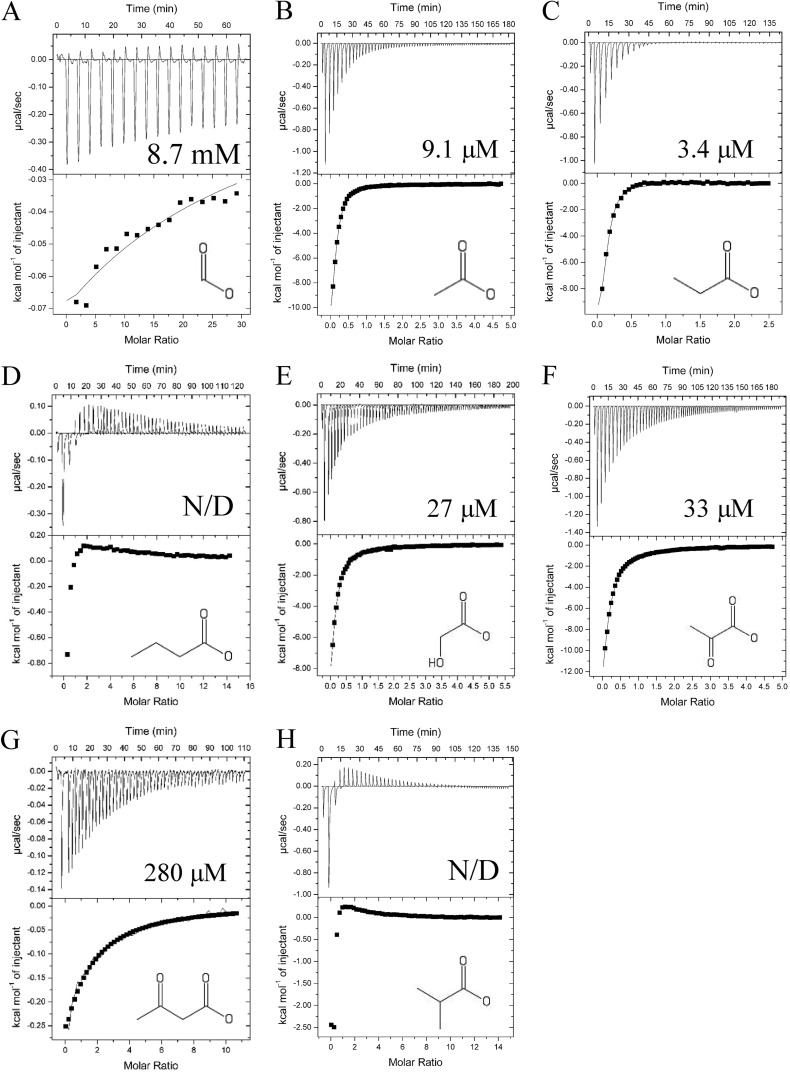

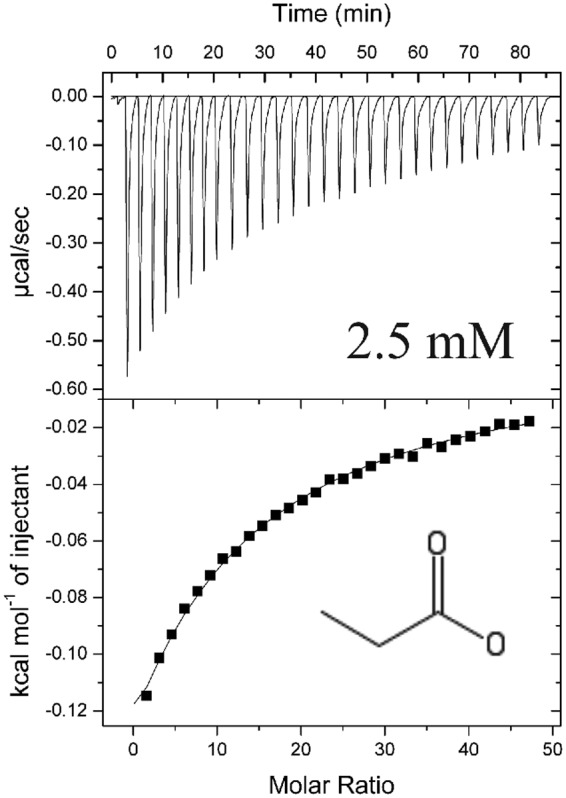

Isothermal titration calorimetry demonstrates direct binding of carboxylates to McpVPR.

To validate that carboxylate chemotaxis in S. meliloti is mediated through direct binding to McpV and to determine binding parameters, we performed isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) at 25°C (except for acetoacetate, which was titrated at 28°C). All compounds displayed binding through the generation of exothermic binding reactions. Data were fitted using the “one-binding-site” model, and dissociation constants (Kd) were calculated. Propionate and acetate exhibited the tightest binding, with Kd values of 3.4 and 9.1 μM, respectively (Fig. 7B and C). The next tightest binding occurred for glycolate and pyruvate, with Kd values of 27 and 33 μM each, followed by acetoacetate, with a Kd of 280 μM (Fig. 7E to G). Lastly, formate had the lowest affinity, with a Kd of approximately 8.7 mM (Fig. 7A). Butyrate and isobutyrate titrations resulted in an exothermic isotherm that quickly transitioned into endothermic reactions (Fig. 7D and H). For isobutyrate, this pattern of interaction occurred at 28, 25, and 15°C. Dissociation constants were not determined for these two compounds because the shape of the curve could not be fitted appropriately with the one-binding-site model. To confirm the capillary assay results obtained for strains with mutations in the McpV binding pocket, purified McpVY143A-PR at a concentration of 75 μM was titrated against 15 mM propionate. The dissociation constant for propionate was approximately 2.5 mM, 1,000-fold lower than that of the wild type (Fig. 7C and 8). Together, the ITC data validated results gained from DSF experiments, established direct binding of carboxylates to McpVPR, and enabled ranking of the compounds by affinity. Furthermore, the data support the homology model based on the Adeh_3718 structure and the involvement of residue Tyr143 in ligand coordination.

FIG 7.

Isothermal titration calorimetry of 75 μM recombinant McpVPR with carboxylates. The top panels depict the raw titration data and the Kd. The lower panels are the isotherms derived by integrating peaks from the raw data and the chemical structure of the titrant. (A) Ten millimolar formate; (B) 2 mM acetate; (C) 2 mM propionate; (D) 5 mM butyrate; (E) 2 mM glycolate; (F) 2 mM pyruvate; (G) 5 mM acetoacetate; (H) 5 mM isobutyrate. N/D, not determined. Titrations of ligand into buffer without protein were performed to subtract heats of dilution. Dissociation constants were reported from curves generated using the MicroCal version of Origin 7.0 software using the one-binding-site model (Origin Lab, Northampton, MA).

FIG 8.

Isothermal titration calorimetry of 75 μM recombinant McpVY143A-PR with 15 mM propionate. The top panel depicts the raw titration data and the Kd. The lower panel depicts the isotherm derived by integrating peaks from the raw data and the chemical structure of the titrant. Titrations of ligand into buffer without protein were performed to subtract heats of dilution. Dissociation constants were reported from curves generated using the MicroCal version of Origin 7.0 software using the one-binding-site model (Origin Lab, Northampton, MA).

Glycolate is present in alfalfa seed exudates.

The discovery that carboxylates are sensed by McpV led us to question if they are exuded by germinating alfalfa seeds. We first used a global metabolite profiling platform (ultraperformance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry [UPLC-QTOF MS]) to determine if the carboxylates acetate, propionate, pyruvate, butyrate, glycolate, acetoacetate, and/or isobutyrate were present in the seed exudate. This analysis identified glycolate as the only carboxylate of interest detectable in the seed exudate, and we proceeded to quantify the amount of glycolate in the seed exudate. Our resulting UPLC-MS analysis showed that alfalfa seed exudates contain 290 ± 94 pmol/seed. With an average seed volume of 2.17 μl, the concentration of glycolate at the surface of the seed is calculated to be 132 ± 42 μM (15). This concentration of glycolate on the seed surface is relevant for chemotaxis (Fig. 3A).

DISCUSSION

Chemotaxis has been thoroughly established as a critical facet of nodule occupancy and competition in symbiotic rhizobacteria (15–25, 35). Plants exude a plethora of compounds, such as amino acids, sugars, organic acids, flavonoids, lipids, and ions (20, 21, 36–38). The sensory repertoire of a bacterium as mediated by MCPs encompasses the range of compounds that are important to its lifestyle. Logically, the sensing profiles of root-associated organisms should evolve around the exudation profiles of their respective hosts.

The traditional capillary assay is a robust method of quantifying and comparing chemotaxis responses to different attractants (34). Using this technique, we identified and compared seven new attractants of S. meliloti (Fig. 3). It should be noted that, because of diffusion, the bacteria in the pond are sensing a concentration that is always less than that loaded into the capillary (39). Acetate and propionate recruited the largest number of cells, caused the greatest shift in Tm of McpVPR in the DSF assay, and had the tightest interactions each, as determined by ITC with a Kd in the micromolar range (Fig. 2 and 7B and C and Table 1). Glycolate and pyruvate drew slightly fewer cells to the capillary. The Tm of McpVPR in the presence of pyruvate was closer to that of acetate and propionate, while that of glycolate was slightly lower than the previous three (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The Kd values of glycolate and pyruvate were similar, in the 10 μM range (Fig. 7E and F). Acetoacetate recruited bacteria in quantities similar to acetate and propionate. The concentration eliciting peak chemotaxis, however, was 100 times greater than that for acetate and propionate (100 mM versus 1 mM) (Fig. 3). The ΔTm of McpVPR in the presence of acetoacetate was 2-fold lower than those in the presence of acetate and propionate. Correspondingly, the Kd of acetoacetate was the second highest among the six that were determined, in the 100 μM range (Fig. 2A and 7G). Formate drew relatively few cells at its peak concentration of attraction, which is likely a result of its comparatively weak Kd of about 8.7 mM (Fig. 2A and 7A) It should be noted that ITC is unfit to monitor interactions with affinities higher than 10 mM (40). Butyrate also elicited one of the lowest attractant responses (Fig. 2B). The affinity of this molecule and its isomer, isobutyrate, to McpV could not be determined because of apparent conflicting interactions detected in the ITC experiments. It is possible that the protein construct interacts with those molecules by a mechanism that is not physiologically relevant, in addition to an association in the canonical binding pocket (Fig. 7D and H). Interestingly, a titration with 10 mM trichloroacetate also produced a similar multiphasic isotherm (data not shown). When comparing the behavioral and in vitro binding data, attractant strength does not necessarily correlate with Kd. Instead, it appears that Kd matches more closely with peak concentration of attraction. Similarly, when the PR of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa chemoreceptor was fused to the signaling domain of the Tar chemoreceptor to create a chimera in E. coli, correlations were found between ligand affinity and signal output or attractant utilization using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay (41). However, this pattern does not hold for all systems, such as the Pseudomonas putida chemoreceptors for TCA intermediates (McpS) and cyclic carboxylates (PcaY_PP) that do not show a distinct difference in ligand-binding affinity for differently utilized attractants (42, 43). In conclusion, small carboxylates are a new class of attractants for S. meliloti that are directly sensed by McpV.

Combining DSF with Biolog PM plates is an effective and facile method for screening the ligand profile of a chemoreceptor (30, 33). While not as robust as ITC, this technique has the advantage of being high throughput and does not require large amounts of protein or ligand. A significant ΔTm was determined to be 3°C because it was clearly larger than the ΔTm of McpVPR in the presence of most other compounds (Fig. 2). This boundary does not appear to define whether or not a compound serves as a ligand. When screening a single-point variant of McpVPR, significant Tm shifts were still identified, while ITC data showed that the variant protein bound to propionate with a 1,000-fold lower affinity, but did not interact with isobutyrate (Fig. 7C and 8 and Table 1; data not shown). Studies of protein-ligand interactions in vitro suggest that the minimum requirement for binding to McpV is a carboxylate group. In summary, DSF is an excellent first screen for the putative ligands of proteins, but it requires validation through other in vitro studies.

Formate, butyrate, and isobutyrate had weak or unorthodox interactions with McpVPR, which is supported by data showing that chemotaxis to the former two required a copy of mcpV (Fig. 5A and 7A, D, and H). Both four-carbon carboxylates are likely too large to properly fit into the binding pocket of McpV. Formate interacts weakly with McpV, while butyrate and isobutyrate may interact with McpV in a more complicated manner. Together, these data indicate that formate and butyrate are very ineffective attractants.

Homologues of McpV have been characterized in two separate species of Pseudomonas (29, 30). McpP of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 was reported to mediate taxis to and directly bind l-lactate, acetate, propionate, and pyruvate. Propionate and pyruvate elicited the highest magnitude of chemotaxis. In ITC studies propionate, pyruvate and acetate all bound to McpP with very similar Kd values between 30 and 40 μM (29). In Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidae, PscD was characterized as a small-carboxylate chemoreceptor using capillary assays, ITC, and protein crystallography. The dissociation constants for glycolate, acetate, propionate, and pyruvate were 23, 31, 101, and 356 μM, respectively. Glycolate had the highest attractant response in this study, while the other three attractants examined were found to draw similar numbers of bacteria. Neither study tested acetoacetate chemotaxis or binding of the Pseudomonas chemoreceptors to acetoacetate. Therefore, the homologue in S. meliloti is the only known acetoacetate chemoreceptor. The sensor domain of PscD was crystallized in the presence of propionate, defining the ligand-binding pocket and coordination sites (30). Both Pseudomonas sensors contain the conserved residues involved in ligand binding, as identified for McpV in Fig. 1B. The comparison of these three homologues begs the question of why homologous sensors in the respective organisms have different preferences. Another interesting avenue to investigate is the structural basis for the differences in chemotactic potency of an attractant and in vitro ligand affinity.

Navigation to the root is a key first step in the interaction between S. meliloti and its host, alfalfa (44, 45). Only glycolate, and none of the other carboxylate attractants tested, was detected in the exudate of alfalfa seeds. We predict that pyruvate and acetoacetate are either not exuded or were not detected because of their instability. UPLC-MS revealed that the concentration of glycolate at the surface of a germinating alfalfa seed is within the sensing range of S. meliloti (Fig. 3A). We previously reported that alfalfa seedlings also exude proline and choline in sufficient quantities to be effectively sensed by McpU and McpX, the respective sensors in S. meliloti (16, 17). Taking into account the exudation profile of alfalfa seedlings, it appears that short-chain carboxylates are not a major avenue of host seed sensing. The exudation of the small carboxylates sensed by McpV in different spatiotemporal contexts should not be ruled out. Acetate, formate, and lactate were detected in the root exudates of two species of the legume genus Lupinus during both flowering and fruiting periods (46).

McpV is clearly a critical chemoreceptor because we recently determined that it is the most abundant chemoreceptor in S. meliloti, accounting for 70% of the total pool of chemoreceptors (47). Perhaps this explains the 1.5-fold increase in chemotaxis to proline in the ΔmcpV strain. The elimination of McpV from the chemoreceptor array could result in an overrepresentation of the remaining chemoreceptors and their respective signals. Most of the McpV ligands analyzed are not exuded by alfalfa seeds, so their purpose in S. meliloti may not be limited to host-microbe interaction. We hypothesize that taxis to these carbon sources is critical to the survival of the bacterium in the bulk soil, which contains many different organic acids (48–50). Acetate, acetoacetate, and propionate have been identified as carbon sources utilizable by S. meliloti (51–53). Interestingly, formate acts as an electron donor during the chemoautotrophic growth of S. meliloti on carbonate (54). The genomes of S. meliloti 1021 and RU11/001 have a putative glcDEF operon, which may allow the use of glycolate in the glyoxylate shunt (55–58).

The characterization of McpV adds a new class of compounds to the known sensory repertoire of S. meliloti. Currently, this includes proteogenic and nonproteogenic amino acids, quaternary ammonium compounds, and two- to four-carbon carboxylates. The function of the remaining five receptors remains to be elucidated. McpY exhibits similarity to receptors involved in energy taxis—the phenomenon where bacteria accumulate in regions rich in compounds that can act as electron donors—and IcpA is annotated to contain a HemAT domain, which is involved in sensing oxygen (5, 23, 59, 60). The periplasmic regions of McpT, McpW, and McpZ remain to be annotated, and the receptors have yet to be characterized. The range of compounds sensed by an individual chemoreceptor can be expanded through indirect sensing via interaction with periplasmic binding proteins. In E. coli, maltose-bound maltose binding protein interacts with Tar, which permits maltose taxis. Bacillus subtilis senses multiple amino acids via indirect and direct binding to McpC (61–63). The elucidation of chemoreceptor function in attractant sensing will increase our knowledge of plant-microbe interactions and bacterial lifestyles. Root exudates are a major avenue for plants and microbes to exchange nutrients and information. Understanding the establishment and maintenance of microbial communities in the rhizosphere is a critical objective of improving modern agriculture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

S. meliloti strains are highly motile MVII-1 derivatives and are listed in Table 2. Derivatives of E. coli K-12 strains and plasmids used for molecular techniques are also listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Species, strain, or plasmid | Characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | recA1 endA1 | 76 |

| M15/pREP4 | Kmr expression strain, lac mtl | Qiagen |

| S17-1 | recA endA thi hsdR RP4-2 Tc::Mu::Tn7 Tpr Smr | 68 |

| S. meliloti | ||

| RU11/001 | Smr, spontaneously streptomycin-resistant wild-type strain | 77 |

| RU11/830 | Smr ΔmcpV | 23 |

| RU13/149 | Smr ΔmcpS ΔmcpT ΔmcpU ΔmcpV ΔmcpW ΔmcpX ΔmcpY ΔmcpZ ΔicpA | 23 |

| BS232 | Smr mcpV-Y143A | This work |

| BS234 | Smr mcpV-H103D | This work |

| Plasmid | ||

| pK18mobsacB | Kmr lacZ mob sacB | 78 |

| pQE60 | Apr, expression vector | Qiagen |

| pBS377 | Apr, pQE60 with mcpV bp 33–471 NcoI/BamHI PCR fragment containing mcpV bp 96–567 (aa 33–189) | This work |

| pBS1151 | Apr, pQE60 with mcpV bp 33–471 NcoI/BamHI PCR fragment containing mcpV bp 96–567 (aa 33–189) with Y143A substitution | This work |

aa, amino acid.

Media and growth conditions.

E. coli was grown using lysogeny broth (LB) at 37°C (64). TYC medium was used to grow S. meliloti at 30°C and contained 0.5% tryptone, 0.3% yeast extract (BD, Sparks, MD), and 6 mM CaCl2 (Fisher, Fairlawn, NJ) with 600 μg/ml streptomycin. Minimal medium used for S. meliloti was Rhizobium basal medium (RB) and contained 0.1 mM NaCl, 0.01 Na2MoO4, 6.1 mM K2HPO4, 3.9 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1 μM FeSO4, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 20 μg/liter d-biotin, and 10 μg/liter thiamine (65). Low-nutrient Bromfield plates were prepared according to Sourjik and Schmitt (66). Ampicillin and kanamycin concentrations used were 100 μg/ml and 25 μg/ml, respectively. Authentic organic acid standards were purchased from Supelco (Bellefonte, PA), except for lithium acetoacetate and glycolic acid, which were supplied from TCI (Tokyo, Japan).

Preparation of seed exudates.

M. sativa Guardsman II variety seeds (0.1 g) were rinsed four times with sterile water and then soaked in 3% H2O2 for 12 min. The seeds were rinsed four more times with sterile water and placed into a 125-ml Erlenmeyer flask with 3 ml of sterile water. Seeds were examined by eye, and exudates were viewed under a microscope for contamination. Exudate (200 μl) was plated onto TYC to check for contamination. Samples that appeared visually clear were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. If no growth was observed on the TYC plates the following day, samples were thawed on ice, sonicated for 10 min in 30- to 40-s pulses, and centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min, and supernatants were withdrawn to yield seed exudates.

Quantification of organic acids in seed exudate.

Global metabolite profiling to determine if carboxylates were present in the seed exudate was performed on a I-class Acquity UPLC interfaced with a Synapt G2-S mass spectrometer operated in high resolution mode (Waters Corp., Milford, MA). The UPLC was fitted with a Waters BEH C18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 by 50 mm). Mobile phase A consisted of water plus 0.1% formic acid and mobile phase B consisted of acetonitrile plus 0.1% formic acid. The flow rate was 0.2 ml/min, and the 10-min gradient was initially 2 min at 0.5% B, followed by 6 min at 10% B, 8.5 min at 90% B, and 9 to 10 min of reequilibration at 0.5% B. Mass spectrometer data collection was performed in both positive and negative modes with an m/z range of 50 to 1,800, capillary voltage of 2.2 kV, cone voltage of 10 V, desolvation gas flow of 450 liters/h, and cone gas flow of 45 liters/h. Presence and absence of the carboxylates was determined by extracting the ion mass of the carboxylate from the total ion chromatogram ([M-H]− glycolate, m/z 75.0088; pyruvate, m/z 87.0088; butyrate and isobutyrate, m/z 87.0452; acetate, m/z 61.0284; propionate, m/z 73.0295; and [M+H]+ acetoacetate, m/z 103.0390).

Glycolic acid quantification was performed using a Waters H-class Acquity UPLC interfaced with a Xevo-MS mass spectrometer (Waters Corp., Milford, MA). The UPLC was equipped with a Rezex ROA organic acid column maintained at 55°C with a mobile phase of water with 0.5% formic acid at a flow rate of 0.25 ml/min for 10 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in selected ion recording (SIR) mode with unit resolution set to detect at 75.0 m/z, cone voltage of 24 V, and dwell time of 1.15 s. A glycolic acid standard was purchased from Supelco (Bellefonte, PA) and used to establish a calibration curve from 0.25 to 2.5 μg/ml.

Mutant construction and genetic manipulation.

Single point mutations in mcpV were made in vitro using overlap extension PCR (67). Allelic exchange mutagenesis was used to construct markerless mutants according to previous protocols (68, 69). DNA isolation and cleanup were performed with Wizard kits from Promega according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Capillary assay.

Capillary assays were performed as originally described by Adler (34), with minor modifications for S. meliloti (17). Motile S. meliloti cells were obtained by diluting stationary-phase TYC cultures into 10 ml of RB overlain onto Bromfield agar plates and then incubating at 30°C for 15 h. Cells were harvested between an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.16 and 0.18 and sedimented by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 5 min before being suspended to a final OD600 of 0.15. A culture amount of 375 μl was placed into a pond formed from a U-shaped glass tube between two glass plates. Microcap glass capillaries (1 μl; Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA) were sealed at one end over a flame and placed into a ligand solution in a vacuum chamber. A vacuum was created in the chamber to allow the solution to fill the capillary after the air was removed and the vacuum was released. Capillaries were placed into the bacterial ponds and left to incubate at room temperature for 2 h. The capillaries were then removed, broken at the sealed tip, and their contents expelled into RB. Serial dilutions were plated in duplicates onto TYC plates containing streptomycin, and colonies were counted after 3 days of growth. The counts of a control capillary were subtracted from all test capillaries to account for accumulation due to random movement of bacteria into the capillary. Three technical replicates were performed for each of three biological replicates.

Homology modeling.

To construct the model of McpV-PR, the amino acid sequence of McpV between Gln33 and Gln189 was uploaded to the SWISS-MODEL server (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics) (70–74). The template used was PDB entry 4K08, a crystallized product of recombinant Adeh_3718, from the soil bacterium Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans (32).

Overexpression and purification of McpVPR.

E. coli M15/pREP4 was transformed with pBS377, and expression cultures were grown to an OD600 between 0.7 and 0.9 before induction with 0.6 mM isopropyl-thiogalactopyranoside. Cultures were further incubated either for 4 h at 25°C or for 16 h at 16°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 9,500 × g for 9 min at 4°C. Cell pellets were suspended in a binding buffer consisting of 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 1 mM phenylmethane sulfonyl fluoride, and 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4). The cells were lysed by two to three passages through a French pressure cell at 16,000 lb/in2 (SLM Aminco, Silver Spring, MD). Lysates were centrifuged at 56,000 × g for 50 min at 4°C, followed by filter sterilization. The clarified lysate was then applied to a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) affinity column (GE Healthcare), and the column was washed with binding buffer. To elute the protein, an elution buffer composed of 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM sodium phosphate, 0.5 M imidazole, and a pH of 7.4 was applied to the column in an increasing linear gradient. Protein elution was monitored by UV absorbance and confirmed by SDS-PAGE. Pooled fractions containing protein were further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-300 HR column (GE Healthcare) in 100 mM NaCl and 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) for DSF experiments, or 0.4 M NaCl and 25 mM HEPES (pH 8.0) for ITC experiments. When appropriate, the protein was concentrated using an Amicon ultrafiltration system and regenerated cellulose membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Protein concentration was determined using UV spectrometry, and a theoretical extinction coefficient of 37,930 M−1 · cm−1 was obtained from the ExPASy online ProtParam tool (75).

Differential scanning fluorimetry.

Compounds in a PM1 microplate (Biolog, Hayward, CA) were dissolved in a master mix of 10 μM McpVPR and 1.4× Sypro Orange in the same size exclusion buffer used to purify the protein. According to the manufacturer, each well contains 0.5 to 1 μmol of compound, making the final concentrations between 7 and 15 mM. A volume of 30 μl from each well was transferred to a 96-well plate reader for use in an ABI 7300 real-time PCR system. The temperature gradient began at 10°C and increased in 0.5°C steps every 30 s to 90°C. The melting temperature (Tm) of the protein in each well was defined as the peak of the first derivative of the fluorescence curve. The melting temperature shift (ΔTm) was determined by subtracting the Tm of the control well containing no ligand from the Tm of each test well. The screen was performed in triplicate using three Biolog plates. For the mutant protein, the screen was performed once.

Isothermal titration calorimetry.

Direct binding studies were performed with a MicroCal VP-ITC microcalorimeter (Malvern, Westborough, MA). McpVPR was used at 75 μM and titrated against 2 to 15 mM each carboxylate. The experiment was performed at 25°C for all compounds except acetoacetate, for which it was performed at 28°C. Prior to experiments, both protein and ligand solution were degassed at a temperature 2 to 3°C above the experimental temperature. All ligand solutions were made with the same batch of 0.4 M NaCl and 25 mM HEPES (pH 8.0) used for the final protein purification step. For baseline titrations, the ligand was titrated into the buffer without protein, which was used a reference subtraction for the respective titrations with protein. Association constants were reported from curves generated using the MicroCal version of Origin 7.0 software using the one-binding-site model (Origin Lab, Northampton, MA).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by NSF grant MCB-1253234 to B.E.S. The Virginia Tech Mass Spectrometry Incubator is maintained with funding from the Fralin Life Science Institute of Virginia Tech as well as from NIFA (Hatch Grant 228344 and VA-160085).

We are indebted to Florian Schubot for sharing the ABI 7300 real-time PCR system and for support with protein modeling.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hazelbauer GL, Falke JJ, Parkinson JS. 2008. Bacterial chemoreceptors: high-performance signaling in networked arrays. Trends Biochem Sci 33:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkinson JS, Hazelbauer GL, Falke JJ. 2015. Signaling and sensory adaptation in Escherichia coli chemoreceptors: 2015 update. Trends Microbiol 23:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bi S, Lai L. 2015. Bacterial chemoreceptors and chemoeffectors. Cell Mol Life Sci 72:691–708. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1770-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krell T, Lacal J, Munoz-Martinez F, Reyes-Darias JA, Cadirci BH, Garcia-Fontana C, Ramos JL. 2011. Diversity at its best: bacterial taxis. Environ Microbiol 13:1115–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller LD, Russell MH, Alexandre G. 2009. Diversity in bacterial chemotactic responses and niche adaptation. Adv Appl Microbiol 66:53–75. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(08)00803-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacal J, Garcia-Fontana C, Munoz-Martinez F, Ramos JL, Krell T. 2010. Sensing of environmental signals: classification of chemoreceptors according to the size of their ligand binding regions. Environ Microbiol 12:2873–2884. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scharf BE, Hynes MF, Alexandre GM. 2016. Chemotaxis signaling systems in model beneficial plant-bacteria associations. Plant Molecular Biology 90:549–559. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewin NJ. 1991. Development of the legume root nodule. Annu Rev Cell Biol 7:191–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.07.110191.001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kondorosi E, Mergaert P, Kereszt A. 2013. A paradigm for endosymbiotic life: cell differentiation of Rhizobium bacteria provoked by host plant factors. Annu Rev Microbiol 67:611–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haag AF, Arnold MF, Myka KK, Kerscher B, Dall'Angelo S, Zanda M, Mergaert P, Ferguson GP. 2013. Molecular insights into bacteroid development during Rhizobium-legume symbiosis. FEMS Microbiol Rev 37:364–383. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drogue B, Dore H, Borland S, Wisniewski-Dye F, Prigent-Combaret C. 2012. Which specificity in cooperation between phytostimulating rhizobacteria and plants? Res Microbiol 163:500–510. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Rhijn P, Vanderleyden J. 1995. The Rhizobium-plant symbiosis. Microbiol Rev 59:124–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Agricultural Statistics Service. 2017. Crop production 2016 summary. National Agricultural Statistics Service, United States Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC: http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/usda/nass/CropProdSu//2010s/2017/CropProdSu-01-12-2017.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindeman WC, Glover CR, Flynn R, Idowu J. 2015. Nitrogen fixation by legumes, guide A-129. New Mexico State University Cooperative Extension, Las Cruces, NM: http://aces.nmsu.edu/pubs/_a/A129/. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webb BA, Helm RF, Scharf BE. 2016. Contribution of individual chemoreceptors to Sinorhizobium meliloti chemotaxis towards amino acids of host and nonhost seed exudates. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 29:231–239. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-12-15-0264-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webb BA, Hildreth S, Helm RF, Scharf BE. 2014. Sinorhizobium meliloti chemoreceptor McpU mediates chemotaxis toward host plant exudates through direct proline sensing. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:3404–3415. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00115-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webb BA, Compton KK, Castaneda Saldana R, Arapov T, Ray WK, Helm RF, Scharf BE. 2017. Sinorhizobium meliloti chemotaxis to quaternary ammonium compounds is mediated by the chemoreceptor McpX. Mol Microbiol 103:333–346. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernabeu-Roda L, Calatrava-Morales N, Cuellar V, Soto MJ. 2015. Characterization of surface motility in Sinorhizobium meliloti: regulation and role in symbiosis. Symbiosis 67:79–90. doi: 10.1007/s13199-015-0340-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller LD, Yost CK, Hynes MF, Alexandre G. 2007. The major chemotaxis gene cluster of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae is essential for competitive nodulation. Mol Microbiol 63:348–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moe LA. 2013. Amino acids in the rhizosphere: from plants to microbes. Am J Bot 100:1692–1705. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1300033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbour WM, Hattermann DR, Stacey G. 1991. Chemotaxis of Bradyrhizobium japonicum to soybean exudates. Appl Environ Microbiol 57:2635–2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson EB. 2004. Microbial dynamics and interactions in the spermosphere. Annu Rev Phytopathol 42:271–309. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.121603.131041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meier VM, Muschler P, Scharf BE. 2007. Functional analysis of nine putative chemoreceptor proteins in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol 189:1816–1826. doi: 10.1128/JB.00883-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier VM, Scharf BE. 2009. Cellular localization of predicted transmembrane and soluble chemoreceptors in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol 191:5724–5733. doi: 10.1128/JB.01286-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webb BA, Compton KK, Del Campo JSM, Taylor D, Sobrado P, Scharf BE. 2017. Sinorhizobium meliloti chemotaxis to multiple amino acids is mediated by the chemoreceptor McpU. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 30:770–777. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-04-17-0096-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ortega A, Zhulin IB, Krell T. 2017. Sensory repertoire of bacterial chemoreceptors. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 81:e00033-. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00033-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anantharaman V, Aravind L. 2000. Cache—a signaling domain common to animal Ca2+-channel subunits and a class of prokaryotic chemotaxis receptors. Trends Biochem Sci 25:535–537. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01672-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Upadhyay AA, Fleetwood AD, Adebali O, Finn RD, Zhulin IB. 2016. Cache domains that are homologous to, but different from PAS domains comprise the largest superfamily of extracellular sensors in prokaryotes. PLoS Comput Biol 12:e1004862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia V, Reyes-Darias JA, Martin-Mora D, Morel B, Matilla MA, Krell T. 2015. Identification of a chemoreceptor for C2 and C3 carboxylic acids. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:5449–5457. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01529-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brewster JL, McKellar JL, Finn TJ, Newman J, Peat TS, Gerth ML. 2016. Structural basis for ligand recognition by a Cache chemosensory domain that mediates carboxylate sensing in Pseudomonas syringae. Sci Rep 6:35198. doi: 10.1038/srep35198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finn RD, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Mistry J, Mitchell AL, Potter SC, Punta M, Qureshi M, Sangrador-Vegas A, Salazar GA, Tate J, Bateman A. 2016. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D279–D285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pokkuluri PR, Dwulit-Smith J, Duke NE, Wilton R, Mack JC, Bearden J, Rakowski E, Babnigg G, Szurmant H, Joachimiak A, Schiffer M. 2013. Analysis of periplasmic sensor domains from Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans 2CP-C: structure of one sensor domain from a histidine kinase and another from a chemotaxis protein. Microbiologyopen 2:766–777. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKellar JLO, Minnell JJ, Gerth ML. 2015. A high-throughput screen for ligand binding reveals the specificities of three amino acid chemoreceptors from Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae. Mol Microbiol 96:694–707. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adler J. 1973. A method for measuring chemotaxis and use of the method to determine optimum conditions for chemotaxis by Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol 74:77–91. doi: 10.1099/00221287-74-1-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Owen AG, Jones DL. 2001. Competition for amino acids between wheat roots and rhizosphere microorganisms and the role of amino acids in plant N acquisition. Soil Biol Biochem 33:651–657. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00209-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones DL, Darrah PR. 1994. Amino-acid influx at the soil-root interface of Zea mays L. and its implications in the rhizosphere. Plant Soil 163:1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00033935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones DL, Edwards AC, Donachie K, Darrah PR. 1994. Role of proteinaceous amino-acids released in root exudates in nutrient acquisition from the rhizosphere. Plant Soil 158:183–192. doi: 10.1007/BF00009493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Odunfa VSA. 1979. Free amino-acids in the seed and root exudates in relation to the nitrogen requirements of rhizosphere soil Fusaria. Plant Soil 52:491–499. doi: 10.1007/BF02277944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Futrelle RP, Berg HC. 1972. Specification of gradients used for studies of chemotaxis. Nature 239:517–518. doi: 10.1038/239517a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiseman T, Williston S, Brandts JF, Lin LN. 1989. Rapid measurement of binding constants and heats of binding using a new titration calorimeter. Anal Biochem 179:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reyes-Darias JA, Yang YL, Sourjik V, Krell T. 2015. Correlation between signal input and output in PctA and PctB amino acid chemoreceptor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 96:513–525. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lacal J, Alfonso C, Liu XX, Parales RE, Morel B, Conejero-Lara F, Rivas G, Duque E, Ramos JL, Krell T. 2010. Identification of a chemoreceptor for tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates. J Biol Chem 285:23126–23136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fernandez M, Matilla MA, Ortega A, Krell T. 2017. Metabolic value chemoattractants are preferentially recognized at broad ligand range chemoreceptor of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Front Microbiol 8:990. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ames P, Bergman K. 1981. Competitive advantage provided by bacterial motility in the formation of nodules by Rhizobium-meliloti. J Bacteriol 148:728–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gulash M, Ames P, Larosiliere RC, Bergman K. 1984. Rhizobia are attracted to localized sites on legume roots. Appl Environ Microbiol 48:149–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lucas Garcia JA, Barbas C, Probanza A, Barrientos ML, Manero FJG. 2001. Low molecular weight organic acids and fatty acids in root exudates of two Lupinus cultivars at flowering and fruiting stages. Phytochem Anal 12:305–311. doi: 10.1002/pca.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zatakia HM, Arapov TD, Meier VM, Scharf BE. 2018. Cellular stoichiometry of methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol 200:e00614-17. doi: 10.1128/JB.00614-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cieslinski G, Van Rees KCJ, Szmigielska AM, Krishnamurti GSR, Huang PM. 1998. Low-molecular-weight organic acids in rhizosphere soils of durum wheat and their effect on cadmium bioaccumulation. Plant Soil 203:109–117. doi: 10.1023/A:1004325817420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Hees PAW, Dahlen J, Lundstrom US, Boren H, Allard B. 1999. Determination of low molecular weight organic acids in soil solution by HPLC. Talanta 48:173–179. doi: 10.1016/S0039-9140(98)00236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li XL, Chen XM, Liu X, Zhou LC, Yang XQ. 2012. Characterization of soil low-molecular-weight organic acids in the Karst rocky desertification region of Guizhou Province, China. Front Environ Sci Eng 6:195–203. doi: 10.1007/s11783-012-0391-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Charles TC, Cai GQ, Aneja P. 1997. Megaplasmid and chromosomal loci for the PHB degradation pathway in Rhizobium (Sinorhizobium) meliloti. Genetics 146:1211–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dunn MF. 1998. Tricarboxylic acid cycle and anaplerotic enzymes in rhizobia. FEMS Microbiol Rev 22:105–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Biondi EG, Tatti E, Comparini D, Giuntini E, Mocali S, Giovannetti L, Bazzicalupo M, Mengoni A, Viti C. 2009. Metabolic capacity of Sinorhizobium (Ensifer) meliloti strains as determined by phenotype MicroArray analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:5396–5404. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00196-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pickering BS, Oresnik IJ. 2008. Formate-dependent autotrophic growth in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol 190:6409–6418. doi: 10.1128/JB.00757-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pellicer MT, Badia J, Aguilar J, Baldoma L. 1996. glc locus of Escherichia coli: characterization of genes encoding the subunits of glycolate oxidase and the glc regulator protein. J Bacteriol 178:2051–2059. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2051-2059.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lord JM. 1972. Glycolate oxidoreductase in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta 267:227–237. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(72)90111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Capela D, Barloy-Hubler F, Gouzy J, Bothe G, Ampe F, Batut J, Boistard P, Becker A, Boutry M, Cadieu E, Dreano S, Gloux S, Godrie T, Goffeau A, Kahn D, Kiss E, Lelaure V, Masuy D, Pohl T, Portetelle D, Puhler A, Purnelle B, Ramsperger U, Renard C, Thebault P, Vandenbol M, Weidner S, Galibert F. 2001. Analysis of the chromosome sequence of the legume symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti strain 1021. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:9877–9882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161294398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wibberg D, Blom J, Ruckert C, Winkler A, Albersmeier A, Puhler A, Schluter A, Scharf BE. 2013. Draft genome sequence of Sinorhizobium meliloti RU11/001, a model organism for flagellum structure, motility and chemotaxis. J Biotechnol 168:731–733. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schweinitzer T, Josenhans C. 2010. Bacterial energy taxis: a global strategy? Arch Microbiol 192:507–520. doi: 10.1007/s00203-010-0575-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hou SB, Larsen RW, Boudko D, Riley CW, Karatan E, Zimmer M, Ordal GW, Alam M. 2000. Myoglobin-like aerotaxis transducers in Archaea and Bacteria. Nature 403:540–544. doi: 10.1038/35000570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Glekas GD, Mulhern BJ, Kroc A, Duelfer KA, Lei V, Rao CV, Ordal GW. 2012. The Bacillus subtilis chemoreceptor McpC senses multiple ligands using two discrete mechanisms. J Biol Chem 287:39412-8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.413518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Richarme G. 1982. Interaction of the maltose-binding protein with membrane vesicles of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 149:662–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koiwai O, Hayashi H. 1979. Studies on bacterial chemotaxis. IV. Interaction of maltose receptor with a membrane-bound chemosensing component. J Biochem 86:27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bertani G. 1951. Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 62:293–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Götz R, Limmer N, Ober K, Schmitt R. 1982. Motility and chemotaxis in 2 strains of Rhizobium with complex flagella. J Gen Microbiol 128:789–798. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sourjik V, Schmitt R. 1996. Different roles of CheY1 and CheY2 in the chemotaxis of Rhizobium meliloti. Mol Microbiol 22:427–436. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.1291489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bryksin AV, Matsumura I. 2010. Overlap extension PCR cloning: a simple and reliable way to create recombinant plasmids. Biotechniques 48:463–465. doi: 10.2144/000113418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simon R, O'Connell M, Labes M, Pühler A. 1986. Plasmid vectors for the genetic analysis and manipulation of rhizobia and other gram-negative bacteria. Methods Enzymol 118:640–659. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)18106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. 1983. A broad host range mobilisation system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Nat Biotechnol 1:783–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Biasini M, Bienert S, Waterhouse A, Arnold K, Studer G, Schmidt T, Kiefer F, Gallo Cassarino T, Bertoni M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. 2014. SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res 42:W252–W258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. 2006. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peitsch MC, Schwede T, Guex N. 2000. Automated protein modelling—the proteome in 3D. Pharmacogenomics 1:257–266. doi: 10.1517/14622416.1.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kiefer F, Arnold K, Kunzli M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. 2009. The SWISS-MODEL repository and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res 37:D387–D392. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guex N, Peitsch MC, Schwede T. 2009. Automated comparative protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-PdbViewer: A historical perspective. Electrophoresis 30:S162–S173. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, Bairoch A. 2005. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPaASy server, p 571–607. In Walker JM. (ed), The proteomics handbook. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hanahan D, Meselson M. 1983. Plasmid screening at high colony density. Methods Enzymol 100:333–342. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)00066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pleier E, Schmitt R. 1991. Expression of two Rhizobium meliloti flagellin genes and their contribution to the complex filament structure. J Bacteriol 173:2077–2085. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.2077-2085.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schäfer A, Tauch A, Jager W, Kalinowski J, Thierbach G, Pühler A. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]