Streptococcus mutans is a major pathogen associated with dental caries and also implicated in systemic infections, in particular, infective endocarditis. The Cnm adhesin of S. mutans is an important virulence factor associated with systemic infections and caries severity. Despite its role in virulence, the regulatory mechanisms governing cnm expression are poorly understood. Here, we describe the identification of two independent regulatory systems controlling the transcription of cnm and the downstream pgfS-pgfM1-pgfE-pgfM2 operon. A better understanding of the mechanisms controlling expression of virulence factors like Cnm can facilitate the development of new strategies to treat bacterial infections.

KEYWORDS: Streptococcus mutans, adhesins, host cell invasion, virulence regulation

ABSTRACT

Cnm is a surface-associated protein present in a subset of Streptococcus mutans strains that mediates binding to extracellular matrices, intracellular invasion, and virulence. Here, we showed that cnm transcription is controlled by the global regulators CovR and VicRKX. In silico analysis identified multiple putative CovR- and VicR-binding motifs in the regulatory region of cnm as well as in the downstream gene pgfS, which is associated with the posttranslational modification of Cnm. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays revealed that CovR and VicR specifically and independently bind to the cnm and pgfS promoter regions. Quantitative real-time PCR and Western blot analyses of ΔcovR and ΔvicK strains as well as of a strain overexpressing vicRKX revealed that CovR functions as a positive regulator of cnm, whereas VicRKX acts as a negative regulator. In agreement with the role of VicRKX as a repressor, the ΔvicK strain showed enhanced binding to collagen and laminin and higher intracellular invasion rates. Overexpression of vicRKX was associated with decreased rates of intracellular invasion but did not affect collagen or lamin binding activities, suggesting that this system controls additional genes involved in binding to these extracellular matrix proteins. As expected, based on the role of CovR in cnm regulation, the ΔcovR strain showed decreased intracellular invasion rates, but, unexpectedly collagen and laminin binding activities were increased in this mutant strain. Collectively, the results presented here expand the repertoire of virulence-related genes regulated by CovR and VicRKX to include the core gene pgfS and the noncore gene cnm.

IMPORTANCE Streptococcus mutans is a major pathogen associated with dental caries and also implicated in systemic infections, in particular, infective endocarditis. The Cnm adhesin of S. mutans is an important virulence factor associated with systemic infections and caries severity. Despite its role in virulence, the regulatory mechanisms governing cnm expression are poorly understood. Here, we describe the identification of two independent regulatory systems controlling the transcription of cnm and the downstream pgfS-pgfM1-pgfE-pgfM2 operon. A better understanding of the mechanisms controlling expression of virulence factors like Cnm can facilitate the development of new strategies to treat bacterial infections.

INTRODUCTION

Streptococcus mutans is a major pathogen associated with dental caries and also implicated in extraoral infections, in particular, infective endocarditis (IE) (1, 2). Once in the bloodstream, S. mutans must first escape host surveillance mechanisms and then rely on its ability to interact with components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in order to adhere to and colonize nonoral tissues (3). In S. mutans, Cnm (collagen binding protein of S. mutans) is a surface adhesin that mediates strong binding to both collagen and laminin (4, 5). Notably, the expression of Cnm has been associated with a variety of systemic infections and conditions, such as IE, hemorrhagic stroke, cerebral microbleeds, and IgA nephropathy, among others (6–8). The cnm gene is found in approximately 15% of clinical isolates and is particularly prevalent in strains isolated from blood and specimens of heart valves (2, 9). Although Cnm can be found in the four S. mutans serotypes (serotypes c, e, f, and k), it is more commonly present in strains of the serotypes with a low oral prevalence (serotypes e, f, and k) and rarely in strains of the more prevalent serotype c (4, 5). Initial studies from our group revealed that Cnm is directly responsible for intracellular invasion of human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAEC) and virulence in Galleria mellonella, an invertebrate model of systemic infection (5, 10). More recently, we used Lactococcus lactis as a heterologous expression system to demonstrate that the expression of Cnm mediates the virulence of an otherwise nonpathogenic organism in a rabbit IE model (11). Moreover, mounting evidence from both clinical and laboratory studies indicates that expression of Cnm is associated with increased caries levels and severity (12–14), conferring a particular advantage for S. mutans to colonize and persist in multiple niches in the oral cavity (12). Finally, we have also shown that Cnm is a glycoprotein that is posttranslationally modified by pgfS, a putative glycosyltransferase that is part of the S. mutans core genome and cotranscribed with cnm (15).

To succeed as a pathogen, bacteria must sense and rapidly adapt to the environmental conditions encountered during the invasion and colonization process. This adaptive process often relies on signal transduction of two-component systems (TCS), which are typically comprised of an environmental sensing membrane-bound histidine kinase (HK) that activates a response regulator (RR), which is a DNA binding protein that modulates expression of target genes when phosphorylated by the HK. In the cnm-negative S. mutans strain UA159, 14 complete TCS have been described (16, 17), including a TCS designated VicRKX (Vic, for virulence control) as well as an orphan RR named CovR (control of virulence; also known as GcrR). In S. mutans, vicR is an essential gene, whereas strains lacking vicK are viable and have been used to characterize the VicRKX system in this organism (18). In the type strain UA159, VicR and CovR regulate genes implicated in the synthesis of and interaction with extracellular polysaccharides (18–21), which are major components of the dental biofilm matrix and directly associated with S. mutans pathogenicity (22, 23). For example, gbpB (glucan binding protein B) was found to be positively regulated by VicR (21, 24), while gtfB and gtfC (glucosyltransferases B and C, respectively) and gbpC (glucan binding protein C) are repressed by CovR (20). More recently, CovR and VicRK were shown to contribute to the ability of S. mutans to interact with components of the immune system (25–27). Specifically, CovR was shown to regulate susceptibility to complement immunity and survival in blood, which was strongly associated with increased expression of genes involved in interactions with sucrose-derived extracellular polysaccharides (gbpB and epsC) (26). On the other hand, a vicK mutant strain showed reduced susceptibility to deposition of C3b of complement, low binding to serum immunoglobulin G (IgG), and a low frequency of opsonophagocytosis by polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) in a sucrose-independent fashion (25). In addition, the ΔvicK strain showed a strong interaction with human fibronectin, another important component of the host ECM (25).

Because Cnm is an important surface-associated virulence factor of S. mutans responsible for tight interactions with ECM components, which have also been shown to interfere with complement activation (5, 28), and given that CovR and VicRKX are critical regulators of surface-associated virulence genes of S. mutans, we wondered if cnm was regulated by CovR, by VicRKX, or by both. Through in silico analysis, we identified CovR and VicR consensus motifs in the regulatory regions located upstream of cnm and in the downstream pgfS-pgfM1-pgfE-pgfM2 operon. Using molecular genetic approaches, we demonstrated that CovR and VicRKX are directly and specifically involved in the transcriptional regulation of cnm and pgfS. CovR was shown to function as a positive regulator of both cnm and pgfS, while the VicRKX system functioned as a negative regulator. The results presented here expand the repertoire of virulence-related genes regulated by CovR and VicRKX to include new core genes, pgfS-pgfM1-pgfE-pgfM2, as well as a noncore gene, cnm. In addition, our findings further underscore the importance of Cnm in S. mutans-host interactions.

RESULTS

CovR and VicRK are involved in regulation of cnm and pgfS.

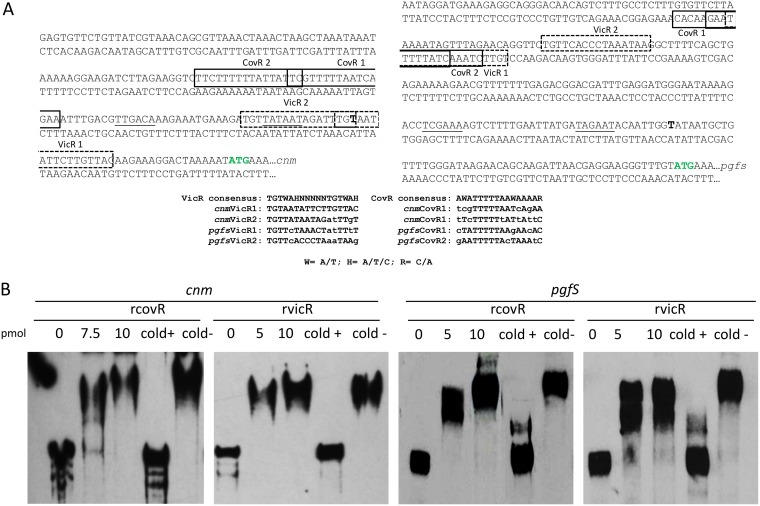

To explore the mechanisms governing the transcription of cnm, we first used 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE)-PCR to determine the transcription start sites of cnm and the downstream pgfS-pgfM1-pgfE-pgM2 operon (Fig. 1A). Of note, previous studies have indicated that in cnm-positive strains, the transcription of pgfS is driven by the distal cnm promoter as well as a second promoter immediately upstream of pgfS (15). Our RACE-PCR analysis revealed that transcription of cnm begins at a thymidine residue located 32 bp upstream from the translational start site. From the +1 site, we predicted the −10 and −35 sites of the cnm promoter, the sequences of both of which had 100% consensus to the canonical −10 (TATAAT) and −35 (TTGACA) sequences. For the pgf operon, transcription initiated at a thymidine residue located 51 bp upstream from the pgfS translational start site. The annotated −10 (TAGAAT) and −35 (TCGAAA) sequences of the pgf promoter differed from the consensus sequence by 1 and 2 bp, respectively (Fig. 1A). In S. mutans, the VicRKX phosphotransfer system and the orphan response regulator CovR have been shown to control the transcription of several surface-associated proteins (18–21, 24). For this reason, we wondered if CovR and/or VicR could also regulate expression of cnm as well as the downstream pgf operon. Through in silico analyses, we identified at least two putative CovR- and VicR-binding sequences (Fig. 1A) in each of the regulatory regions of cnm and pgfS that either were a perfect match or differed from the consensus sequences (17, 21) by as many as 6 bases (Fig. 1A).

FIG 1.

Analysis of the cnm and pgfS promoter regions and interactions of CovR and VicR with cnm and pgfS promoters. (A) Mapping of the transcription start site of cnm and pgfS genes by RACE-PCR. Translational start sites are marked with green letters, and transcription start sites are shown in bold black font. Putative CovR and VicR binding sites are shown in solid and dashed boxes, respectively. Consensus sequence matches for both CovR and VicR are shown in uppercase letters, whereas the mismatches present in the putative binding sites were assigned in lowercase letters. Underlined letters indicate −10 and −35 regions. (B) VicR and CovR directly interact with the promoter regions of cnm and pgfS. Recombinant CovR (rCovR) and VicR (rVicR) proteins bind to the promoter regions of cnm and pgfS, as determined by EMSA. The specificity of binding was confirmed in competitive assays using excess unlabeled specific DNA (cold+) or excess unlabeled unspecific DNA (cold−). The data shown are representative of those from at least three independent experiments.

Next, we used purified recombinant CovR (rCovR) and recombinant VicR (rVicR) to determine whether these proteins can directly and specifically interact with the respective cnm and pgfS promoters in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs). The results revealed that both CovR and VicR specifically bind to the regulatory regions of cnm and pgfS, an effect that was reversed by addition of excess unlabeled (cold) DNA probe, whereas addition of the same molar excess (200-fold) of nonspecific DNA did not interfere with protein-DNA binding (Fig. 1B). These findings were further validated using covR (CovR-autoregulated) and gbpB (VicR-regulated) DNA probes as positive controls and gtfD and covR DNA probes as negative controls for rCovR and rVicR, respectively (data not shown).

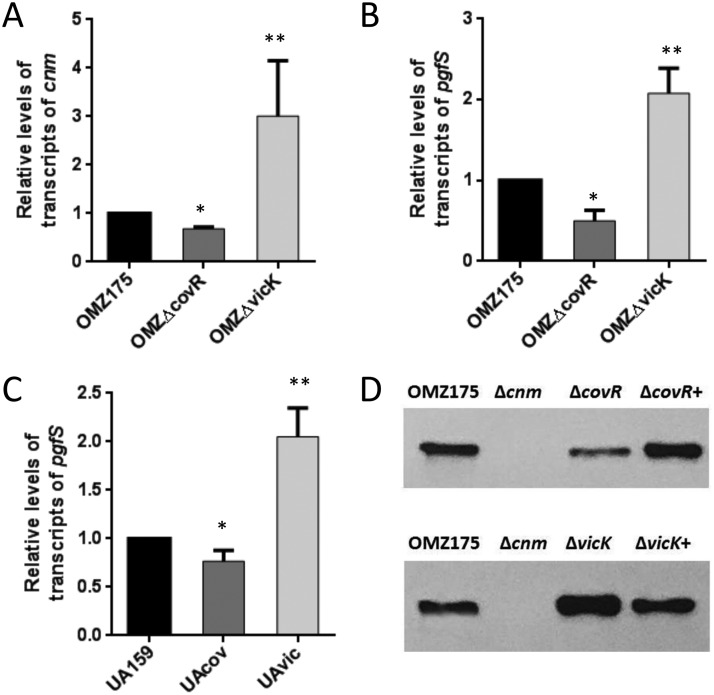

To conclusively demonstrate that CovR and VicRKX regulate transcription of cnm and pgfS, the covR and vicK genes from the cnm-positive strain OMZ175 were inactivated to generate, respectively, the ΔcovR and ΔvicK strains. Of note, vicR is an essential gene in S. mutans (18), and studies on the role of the VicRKX system in this organism have resorted to phenotypic characterizations of vicK mutants as well as in vitro promoter binding assays using recombinant VicR (18, 21, 29, 30). The relative levels of cnm and pgfS transcripts were significantly lower (∼50% reduction, P < 0.05) in the ΔcovR strain than in the parent strain (Fig. 2A and B). Conversely, expression of cnm and pgfS was increased by 3- and 2-fold (P < 0.01), respectively, in the ΔvicK strain compared to the parent OMZ175 strain. In addition to OMZ175, we also determined the transcription levels of pgfS in ΔcovR and ΔvicK mutants of the cnm-negative strain UA159 and observed patterns of regulation similar to those found in OMZ175; i.e., pgfS was downregulated in the ΔcovR strain and upregulated in the ΔvicK strain (Fig. 2C), indicating that regulation of the core gene pgfS by CovR and VicR is conserved among S. mutans strains.

FIG 2.

Transcription levels of cnm and pgfS and abundance of Cnm in S. mutans OMZ175 and derivatives. The relative levels of gene transcripts of cnm (A) and pgfS (B) in ΔcovR and ΔvicK mutant strains of OMZ175 and pgfS in mutant strains of the cnm-negative strain UA159 (C) were determined by qRT-PCR. Columns and bars indicate averages and standard deviations from at least three independent experiments, respectively. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to the parent strain (analysis of variance with a post hoc Dunnett's test; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (D) Detection of Cnm in cell extracts of S. mutans strains by Western blotting. The Δcnm strain was used as a negative control. The blots shown are representative of those from three independent experiments.

Next, we performed Western blot analysis to compare Cnm levels in OMZ175 and its ΔcovR and ΔvicK derivatives. In agreement with the results of quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis, the levels of Cnm were reduced by ∼50% in the ΔcovR strain and elevated by ∼2-fold in the ΔvicK mutant compared to those in OMZ175 (Fig. 2D). Notably, Cnm levels were restored to wild-type levels in the complemented covR (ΔcovR+) and vicK (ΔvicK+) strains.

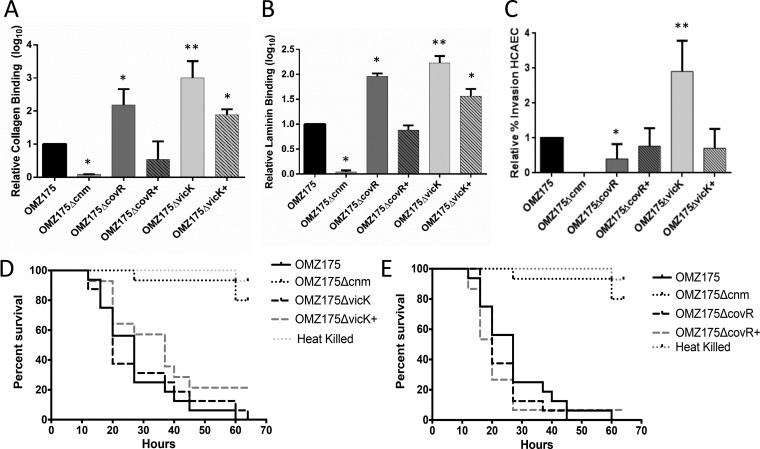

Inactivation of covR and vicK affects the expression of Cnm-dependent phenotypes.

The results described above revealed that CovR and VicR directly and independently control cnm expression in S. mutans. Here, we tested whether the different levels of Cnm production in the mutant strains would be reflected in the expression of phenotypes that are associated with Cnm expression. Specifically, we determined the capacity of the ΔcovR and ΔvicK strains to bind to collagen or laminin in vitro, invade HCAEC, and kill larvae of the wax moth Galleria mellonella. Compared to the parent strain, the ΔvicK mutant showed increased binding to either collagen or laminin (>250-fold) and increased HCAEC invasion rates (2.5-fold) (Fig. 3A to C). These results are in good agreement with the negative role of VicRKX in cnm transcription (Fig. 2). However, virulence in G. mellonella was not significantly altered in the ΔvicK strain (Fig. 3D), which may be associated with the broader regulatory role of VicR in virulence gene expression in S. mutans. Compatible with the central role of Cnm in intracellular invasion, a 50% reduction in HCAEC invasion rates was observed with the ΔcovR strain (Fig. 3C), but this mutant strain displayed an enhanced ability to bind to collagen or laminin (20- and 10-fold, respectively) (Fig. 3A and B). Similar to the ΔvicK strain, the virulence of the ΔcovR strain in G. mellonella was not altered (Fig. 3E). Given the unexpected finding that inactivation of CovR, a positive regulator of cnm, led to increases in collagen/laminin binding activities, we investigated the effect of covR inactivation of the collagen and laminin binding efficiency in S. mutans B14, a serotype e cnm-positive strain also shown to avidly bind to collagen and laminin in a Cnm-dependent manner (5). We found that the B14 ΔcovR strain displayed collagen- and laminin-binding profiles similar to those of the OMZ175 ΔcovR strain, i.e., enhanced binding compared to that of the parent strain (data not shown).

FIG 3.

Contribution of CovR and VicRKX to Cnm-mediated phenotypes associated with systemic virulence in OMZ175. (A, B) Relative collagen (A) and laminin (B) binding of covR and vicK mutants and their respective complemented strains, OMZ175 ΔcovR+ and OMZ175 ΔvicK+, compared to wild-type OMZ175. (C) Percent HCAEC invasion by covR and vicK mutants and the complemented strains in relation to that by OMZ175. Bacteria were recovered from the intracellular compartment of HCAEC after 3 h of infection. (A to C) Columns and bars represent means and standard deviations from at least three independent experiments, respectively. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to the wild type (the Kruskal-Wallis test with a post hoc Dunn's test; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (D, E) Percent survival of G. mellonella larvae infected with OMZ175 ΔvicK (OMZΔvicK) (D) and OMZ175 ΔcovR (OMZΔcovR) (E) mutants and their respective complemented strains. Heat-killed OMZ175 was used as a negative control of infection. The results are representative of those from experiments performed at least in triplicate. The results were plotted as Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and differences in survival were compared using the log-rank test (P < 0.05).

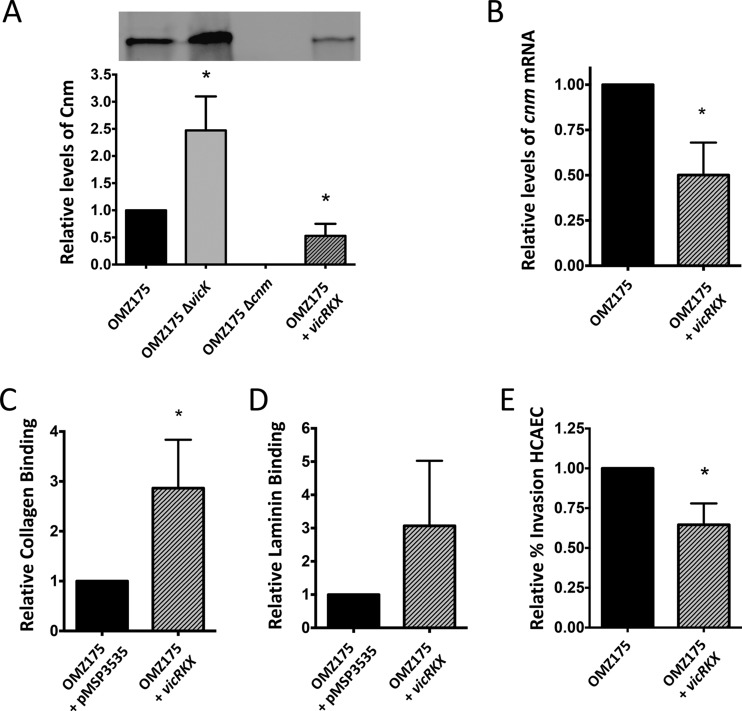

Overexpression of VicRKX results in decreased Cnm-dependent phenotypes.

Given that vicR is an essential gene in S. mutans, we created a vicRKX-overexpressing strain in the OMZ175 background to further explore the contribution of VicRKX in the control of Cnm-mediated phenotypes. In agreement with the assigned function of VicRKX as a cnm repressor, Western blot analyses and qRT-PCR revealed that Cnm protein and cnm transcript levels were significantly lower (∼50% less) in the vicRKX-overexpressing strain than in OMZ175 (Fig. 4A and B). Interestingly, compared to OMZ175, the vicRKX-overexpressing strain had increased levels of collagen binding (Fig. 4C) (P ≤ 0.05), and while the same trend was observed in regard to laminin binding, the difference was not statistically significant due to sample variations (Fig. 4D). Consistent with the role of VicR as a negative regulator of cnm, we observed a significant reduction (∼40%) in HCAEC invasion rates, a phenotype that is entirely Cnm dependent, in the vicRKX-overexpressing strain compared to OMZ175 (Fig. 4E).

FIG 4.

Overexpression of vicRKX results in reduced Cnm expression levels. (A) Western blot and densitometry analysis of Cnm expression in OMZ175, OMZ175 ΔvicK, the Δcnm strain, and OMZ175 vicRKX using an anti-Cnm-specific antibody. (B) qRT-PCR of cnm transcript levels in OMZ175 and OMZ175 vicRKX. (C to E) Collagen binding (C), laminin binding (D), and HCAEC invasion rates (E) in the vicRKX-overexpressing strain in relation to those in OMZ175. Columns and bars represent means and standard deviations from at least three independent experiments, respectively. Asterisks indicate significant differences in relation to the corresponding wild type (Kruskal-Wallis with post hoc Dunn's test; *, P < 0.05).

CovR phosphorylation is independent of VicK in S. mutans OMZ175.

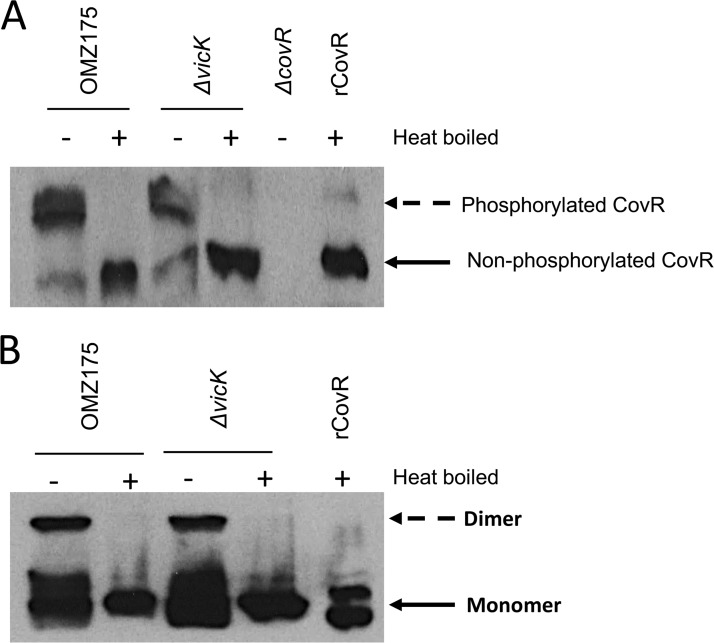

In S. mutans, CovR is considered an orphan response regulator, as its kinase partner is not genetically linked. Considering that VicRKX regulates several genes that are also regulated by CovR, we wondered whether VicK can cross-phosphorylate CovR. Thus, to address this possibility, we assessed the phosphorylation status of CovR in vivo in the parent and ΔvicK strains using a CovR-specific antibody. Based on the results shown in Fig. 5A, we conclude that VicK does not phosphorylate CovR, as the ΔvicK strain displayed the same phosphorylation pattern of CovR observed in the parent OMZ175 strain. Furthermore, CovR phosphorylation probably occurs via Asp53, as it proves to be heat labile (Fig. 5A) (31). We also observed that phosphorylated CovR has a strong tendency to form dimers, as only monomeric CovR was detected in samples that were heat treated, separated by SDS-PAGE, and developed using anti-CovR antibodies (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5.

Determination of phosphorylation status of CovR. Western blot analysis of CovR protein of OMZ175, OMZ175 ΔvicK, and OMZ175 ΔcovR loaded (at 20 μg protein per lane) onto either a 10% Phos-tag SDS-PAGE gel (A) or 10% SDS-PAGE gel (B). Purified recombinant CovR (rCovR) was used as a control for unphosphorylated CovR. Dimer and Monomer, dimeric and monomeric CovR, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In S. mutans, Cnm is a surface-associated glycoprotein, present in approximately 15% of clinical isolates, that mediates robust adhesion to collagen and laminin as well as invasion of endothelial cells (4, 5). In addition to these attributes, we and others have shown that Cnm is a virulence factor that contributes to systemic virulence in the G. mellonella invertebrate model (5), infectivity in a rabbit model of infective endocarditis (11, 32), and caries severity in a rat model (12). However, the mechanisms regulating expression of cnm remain unknown, in large part because previous studies on S. mutans gene regulation mainly focused on serotype c cnm-negative strains, such as UA159. Moreover, the recognition and appreciation of the importance of the pan-genome of S. mutans are relatively nascent (33–35). Recently, we showed that cnm, a noncore gene, can be cotranscribed with the downstream core gene pgfS in OMZ175, which encodes a putative glycosyltransferase involved in the O-glycosylation of Cnm (15). Because glycosylation confers increased stability to Cnm, the inactivation of pgfS led to a decrease in several Cnm-mediated phenotypes (15). In the present study, we showed that both cnm and pgfS are directly regulated by CovR and VicRKX, providing the first evidence of the direct regulation of a noncore gene, cnm, by these global regulators of virulence gene expression. From an evolutionary standpoint, it is intriguing that a noncore gene, possibly acquired by lateral gene transfer, is governed by regulatory systems that are part of the S. mutans core genome. Because CovRS (or the orphan regulator CovR in S. mutans) and VicRKX are conserved among streptococci and other Gram-positive species, it is important to investigate the regulation of cnm orthologues by these regulators in other species. The VicR homolog of S. aureus, known as WalR, was shown to bind to a conserved DNA motif consisting of two hexanucleotide direct repeats separated by 5 nucleotides [5′-TGT(A/T)A(A/T/C)-N5-TGT(A/T)A(A/T/C)-3′] (36). More recently, a VicR consensus binding site almost identical to the one present in S. aureus was described in S. mutans [5′-TGT(A/T)(A/T)(T/A)A(A/T)(T/A)(T/A)(T/C)(A/G)(T/A)N(A/T)] (17). In S. mutans, VicR was shown to control, either directly or indirectly, the expression of genes involved in the synthesis of exopolysaccharides (gtfBC and gtfD) and glucan-binding proteins (gbpB), cell wall biogenesis (smaA, lysM, and wapE), competence (comC, comDE, and comX), mutacin production (nlmAB, nlmC, and nlmD) (18, 21, 29, 30), and the synthesis of proteases associated with the degradation of complement components (SMU.399 and pepO) (21, 25). While the VicRKX system typically acts as a direct activator of genes involved in biofilm formation (18, 21), this system has been shown to function as a repressor of genes involved in this process at times (21, 25). In the cnm-negative strain UA159, CovR was shown to contribute to the transcription of ∼6.5% of the entire genome (37), and previous studies revealed a significant overlap between the CovR and VicRKX regulons in the UA159 strain (21, 30). Interestingly, CovR and VicR often regulate the same gene in an opposite manner, whereby one regulator functions as an activator and the other functions as a repressor (17, 20, 21). Consistent with the roles of CovR and VicRKX in coordinating the expression of virulence genes, we identified cnm and pgfS to be new virulence-related genes that are coregulated, in an opposite manner, by CovR and VicRKX. The location of the CovR and VicR consensus binding sequences in the cnm regulatory region provided some clues of the functional roles of each regulator. Usually, transcriptional activators bind upstream of the −35 region, such that RNA polymerase interactions with DNA are facilitated by the transcriptional regulator-DNA interaction. On the other hand, repressors often compete with the RNA polymerase for binding to the promoter region, such that consensus binding sequences of repressors are often located close to or overlap the −35 and −10 sequences. The two consensus binding sequences for CovR, shown to function as a positive regulator for cnm, were located ∼10 bp upstream of the −35 region. On the other hand, the consensus sequences for VicR, shown to function as a negative regulator, overlapped the transcriptional start site, potentially allowing VicR to interfere with RNA polymerase recognition of the promoter sequence. In the pgfS regulatory region, putative CovR and VicR binding motifs overlap each other, are located in a distal site from the −35 region, and overlap each other by 7 bp. The overlapping location of both the VicR and CovR binding sites in the pgfS promoter suggests that these regulators compete for the same DNA region. It is important to note that due to the fact that the CovR and VicR consensus motifs are A/T rich and that S. mutans is a low-GC organism, several other near-consensus DNA sequences can be identified in these two promoter regions. Thus, it is possible that both CovR and VicR interact with more than one sequence present in the cnm and pgfS promoters.

Although CovR is an orphan response regulator in S. mutans, it can be phosphorylated by a noncognate phosphodonor (Fig. 5A) (31, 38). It is interesting to note that although CovR forms dimers in its phosphorylated form (Fig. 5B), phosphorylation as well as dimerization does not appear to be essential for its activity (31). Independent DNA binding experiments by Khara et al. (31) revealed that the phosphorylation of CovR changes the affinity toward DNA either positively or negatively, depending on the different promoter, compared to that of unphosphorylated CovR. An in vitro phosphorylation study by Downey et al. (38) indicated that CovR phosphorylation by VicK is modest and occurs only in the presence of manganese. More recently, Khara et al. showed that acetyl phosphate, an intracellular phosphodonor molecule, can phosphorylate CovR (31). Here, we showed that the absence of VicK does not affect the phosphorylation status of CovR (Fig. 5A), indicating that in OMZ175 the phenotypes of the vicK mutant are unrelated to the CovR phosphorylation status.

In bacteria, protein glycosylation contributes to protein folding and secondary structure formation, cell adhesion, thermodynamic stability, modulation of immune recognition, and protection against proteolytic degradation (39, 40). While only Cnm and WapA, a surface-associated adhesin that is part of the core genome of S. mutans and that is mainly involved in biofilm formation and collagen binding (41), have been identified to be protein targets of Pgf-mediated glycosylation to date (42), it is likely that the Pgf glycosylation machinery modifies additional proteins in S. mutans. Thus, the regulation of pgfS by both CovR and VicRKX suggests that the protein glycosylation profiles of S. mutans may vary according to environmental cues that trigger CovR and VicRKX regulatory activities. Despite a major role of the CovR and VicR regulators in controlling multiple functions involved in S. mutans oral and systemic virulence, the environmental signals activating these regulators in this species remain to be deciphered. However, the findings that both systems coordinate expression of multiple genes for biofilm formation (16, 18, 21), as well as genes for evasion of host immune components and survival in human blood (25, 26), are compatible with their involvement in Cnm regulation.

The evidence that VicRKX serves as a transcriptional repressor of cnm was in agreement with the expression of Cnm-related phenotypes in the ΔvicK strain. When analyzing the vicRKX-overexpressing OMZ175 strain, however, the relationship was much less clear. While expressing significantly less Cnm and showing a significant decrease in invasion rates, the vicRKX-overexpressing strain was able to bind collagen and laminin at levels that were similar to or even higher than those observed in the parent strain. The downregulation of cnm in the ΔcovR strain was consistent with the impaired ability of this mutant strain to invade HCAEC, though it stood in contrast to the increased collagen and laminin binding activities observed for this strain. While we do not have a clear explanation for these conflicting results, we speculate that global regulation by CovR and VicRKX might affect bacterial traits that compensate or even overcompensate for the alterations in the Cnm level, thereby exposing the limitations of attempts to link the phenotypes of global regulators to a single gene locus. There are at least two additional surface proteins in S. mutans, namely, SpaP and WapA, that have been shown to interact with collagen in vitro (41, 43, 44). Thus, we wondered if expression of one or both proteins was upregulated in the ΔcovR strain, thereby providing an explanation for the unexpected increase in the collagen binding activity of the ΔcovR strain. Western blot analysis using anti-WapA- and anti-SpaP-specific antibodies (a gift from L. J. Brady, University of Florida) revealed that expression of either SpaP or WapA was not altered in the ΔcovR strain compared to the parent OMZ175 strain (data not shown), suggesting that the unexpected collagen binding activity of the ΔcovR strain is not due to increases in SpaP and WapA production.

Collectively, the present study identifies CovR and VicRKX to be direct regulators of cnm and pgfS in S. mutans, thereby expanding the repertoire of virulence-related genes regulated by these two global regulators. To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify mechanisms regulating Cnm production, thereby providing the first insight into how S. mutans governs this important virulence factor during infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All E. coli strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C. When required, kanamycin (100 μg ml−1) or ampicillin (100 μg ml−1) was added to LB broth or agar plates. Strains of S. mutans were routinely cultured in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. When required, kanamycin (1,000 μg ml−1), erythromycin (10 μg ml−1), or spectinomycin (1,500 μg ml−1) was added to BHI broth or agar plates.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Serotype | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. mutans | |||

| OMZ175 | f | Dental plaque | B. Guggenheim |

| OMZ175 Δcnm | f | Δcnm::Kanr | 5 |

| OMZ175 ΔcovR | f | ΔcovR::Ermr | This study |

| OMZ175 ΔvicK | f | ΔvicK::Ermr | This study |

| OMZ175 ΔcovR+ | f | pMC340B::SMU.1924 Kanr | This study |

| OMZ175 ΔvicK+ | f | ΔvicK::Ermr/pDL278::SMU.1516 Specr | This study |

| OMZ175/pMSPVicRKX | f | pTG001::SMU.1515-SMU.1517 Ermr | This study |

| B14 | e | Dental plaque | A. Bleiweis |

| B14 ΔcovR | e | ΔcovR::Ermr | This study |

| UA159 | c | Dental plaque | University of Alabama |

| UA159 Δcov | c | ΔcovR::Ermr | 27 |

| UA159 Δvic | c | ΔvicK::Ermr | 24 |

| E. coli | |||

| BL21/pETrCovRSmu | pET22B::covR | 21 | |

| BL21/pETrVicRSmu | pET22B::vicR | 21 |

Genetic manipulation of S. mutans OMZ175.

Mutations of covR and vicK in OMZ175 were generated by amplifying the appropriate regions from the mutant strains that had previously been created in the S. mutans UA159 background strain, in which the gene coding regions were replaced by an erythromycin resistance cassette (24, 27). Then, 100 ng of the PCR product was used to transform OMZ175 in the presence of the ComX-inducing peptide (XIP) as described elsewhere (45). Transformants were selected on plates containing erythromycin, and gene inactivations were confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing analysis. To construct a covR-complemented strain, the full-length covR gene was cloned into the integration vector pMC340B (46). The resulting plasmid (pMCcovR) was then transformed into the covR mutant strain (OMZ175 ΔcovR) for integration at the mtlA1 locus. Complemented strains were selected on plates containing kanamycin, and positive clones were confirmed by PCR and sequencing of the mltA1 locus. To complement the OMZ175 vicK mutant strain, the plasmid pDL278-vicK, previously used to complement the vicK mutant in UA159 (24), was used to transform the OMZ175 ΔvicK strain. Transformants were selected on plates containing spectinomycin and screened by PCR. To create the vicRKX-overexpressing OMZ175 strain, the entire vicRKX coding region was amplified using primers VicRKXfwd and VicRKXrev (Table 2). The amplified PCR product was digested with BamHI and XhoI and ligated to the nisin-inducible shuttle vector pTG001, a modified version of pMSP3535 (47) with an optimized ribosome binding site and additional restriction cloning sites (a gift from Anthony O. Gaca from Harvard Medical School). All primers used for the genetic manipulation of S. mutans are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer purpose and primer | Sequencea | Product size (bp) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutant construction | |||

| P1 covR | 5′-CGTTCTATGAAACCTGTTGA-3′ | 2,038 | 27 |

| P4 covR | 5′-CTGCCAACTCATCCATAAC-3′ | ||

| P1 vicK | 5′-TTACCAGATGCTTTTGTTGCT-3′ | 2,036 | 24 |

| P4 vicK | 5′-CTCTTGCCGTCTTTCATCAG-3′ | ||

| C1 covR-SphI | 5′-CCTCTACCCAGCATGCCAATGGAAC-3′ | 1,039 | This study |

| C2 covR-XhoI | 5′-GTCCAATTTCTCGAGTTATCGCGTG-3′ | ||

| VicRKXfwd | 5′-CGCGGATCCTTAGTTAGTTAGAGGAGG TATTCATAATGAAG-3′ | ||

| VicRKXrev | 5′-GCGCTCGAGCTAGATTTTTGCTAATGG-3′ | 2,894 | This study |

| qRT-PCR | |||

| covR-RTF | 5′-CGAAATATGGCACGAACAC-3′ | 185 | 21 |

| covR-RTR | 5′-AGAGATGGACGGGTATGAA-3′ | ||

| vicK-RTF | 5′-CGGCGTGATGAATATGATGAA-3′ | 185 | 21 |

| vicK-RTR | 5′-GAGGTTAATGGTGTCCGCAGT-3′ | ||

| pgfS-RTF | 5′-CACCCTCCTGCTCTCATTCC-3′ | 166 | This study |

| pgfS-RTR | 5′-TGCCATCTGTTAACTGCACAT-3′ | ||

| cnm-CF | 5′-CTGAGGTTACTGTCGTTAAA-3′ | 137 | 13 |

| cnm-CR | 5′-CACTGTCTACATAAGCATTC-3′ | ||

| EMSA | |||

| SMU.22-gbpB-F | 5′-TTGACAGCTTATCCTTTAAATG-3′ | 300 | 21 |

| SMU.22-gbpB-R | 5′-TTTACAGCTGATAATGTTGTCG-3′ | ||

| SMU.910-gtfD-F | 5′-TCTCTCCTGACCACTCCCTTA-3′ | 324 | 21 |

| SMU.910-gtfD-R | 5′-TACCCAGTGCTTTTTAACCTTG-3′ | ||

| SMU.1924-covR-F | 5′-AGATGTCCTCTACCCATTGA-3′ | 356 | 21 |

| SMU.1924-covR-R | 5′-CCTCATATCCTTCATGTTGTA-3′ | ||

| cnm-EMSA-F | 5′-CTTCAAGCCAGTCATCTG-3′ | 340 | This study |

| cnm-EMSA-R | 5′-CAAAATGATGGCAACGGTT-3′ | ||

| SMU.2067-pgfS-F | 5′-CTTGCAGCTGTCTCAATG-3′ | 350 | This study |

| SMU.2067-pgfS-R | 5′-TCAATCATTTTTTCTTCATTG-3′ | ||

| RACE-PCR | This study | ||

| cnmGSP1 | 5′-CGCTGGTAACTTGGAGCTG | This study | |

| cnmGSP2 | 5′-GCAAGCCAGTAATACTGT | This study | |

| pgfsGSP1 | 5′-TCTCCCTTACGGTCACGCTGACCGCTGACA | This study | |

| pgfsGSP2 | 5′-GACAACATCATAACCTTCC |

Underlined sequences indicate restriction enzyme sites.

qRT-PCR analysis.

RNA was extracted from cultures grown to mid-exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], ∼0.3) as previously described (48). Briefly, cDNA from 0.5 μg of RNA was synthesized using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcriptase kit containing random primers (Applied Biosystems). Gene-specific primers for the cnm and pgfS coding sequences (Table 2) were designed using Beacon Designer (version 2.0) software (Premier Biosoft International) to amplify a region of each gene 85 to 200 bp in length. Quantitative real-time PCRs (qRT-PCRs) were performed in an iCycler apparatus (Bio-Rad).

Western blot analysis.

Whole-cell protein lysates were obtained by homogenization in the presence of 0.1-mm glass beads using a bead beater (Biospec). The protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce). Twenty micrograms of protein lysates was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore). Cnm detection was performed using a rabbit anti-recombinant CnmA (recombinant A domain of Cnm) polyclonal antibody (10) diluted 1:2,000 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus 0.01% Tween 20 and anti-rabbit immunoglobulin horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-coupled antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). The Western blots were quantified using ImageJ software. The protein concentration (usually 20 μg) of the lysates used in Western blot analyses was validated by either loading of proteins on a separate SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie blue or staining of the blot with Ponceau S just after transfer from the SDS-PAGE gel (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Production of rCovR and rVicR.

To obtain His-tagged rCovR and rVicR proteins, Escherichia coli BL21 harboring the expression vector pET-covR or pET-vicR (21) was grown in LB to an OD600 of 0.5 and expression of rCovR or rVicR was induced for 3 h with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyrosinide (IPTG). After cell lysis, recombinant proteins were purified by affinity chromatography with Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen). Eluted recombinant proteins were dialyzed overnight in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C. Aliquots of purified proteins were stored at −20°C in 10% glycerol. Protein samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie blue staining. The concentrations of rCovR and rVicR were determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. To confirm the identity of the purified recombinant proteins, mass spectrometry analysis was performed in the UF ICBR Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry core facility.

EMSA.

Amplicons of the promoter regions of cnm, pgfS, gbpB (VicR positive control), covR (CovR positive control and VicR negative control), and gtfD (CovR negative control) were obtained with specific primers (Table 2) and biotinylated using a biotin 3′ end DNA labeling kit (Thermo Scientific). Binding reactions of labeled DNA (∼20 fmol) with rCovR or rVicR (0, 5, 7.5, 10 pmol) were carried out in volumes of 20 μl containing 1× binding buffer (100 mM Tris, 500 KCl, 10 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.5), poly-l-lysine (50 ng μl−1), and an unspecific competitor [poly-d(I·C)]. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 45 min, and DNA-protein complexes were separated in nondenaturing 6% acrylamide gels in 0.5× TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) buffer (pH 8.0). Protein-DNA complexes were electrotransferred to positively charged nylon membranes (Thermo Scientific Fisher) and detected with a LightShift chemiluminescent electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) kit using stabilized streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Thermo Scientific), according to the manufacturer's instructions. To assess the specificity of binding, a 200-fold excess of unlabeled test fragment (cold DNA) was incubated with rCovR or rVicR in each reaction mixture.

ECM binding assay.

In vitro assays to determine collagen and laminin binding ability were performed as described elsewhere (10). Briefly, 100 μl of PBS-washed bacterial suspensions containing approximately 1 × 109 CFU ml−1 was added to each well of a microtiter plate that had been previously coated for 18 h at 4°C with 40 μg ml−1 type I collagen from rat tail (Sigma-Aldrich) or 50 μg ml−1 mouse laminin (Becton Dickinson). Adherent cells were stained with 0.05% crystal violet (CV) solution and detected by determination of the absorbance at 575 nm.

HCAEC invasion assay.

Antibiotic protection assays were performed to assess the capacity of the mutant strains to invade human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAEC) (5, 49). Briefly, primary HCAEC (Lonza) suspensions containing 0.5 × 105 endothelial cells were seeded into the wells of 24-well flat-bottomed tissue culture plates and incubated in the presence of gentamicin and endothelial growth factor supplements (Lonza) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere until they reached 80 to 90% confluence. Overnight bacterial cultures were washed twice in PBS (pH 7.2) and resuspended in endothelial cell basal medium (EBM-2) (Lonza) containing 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) without antibiotics. One milliliter of 2% FBS–EBM-2 containing 1 × 107 CFU ml−1 of S. mutans was used to infect HCAEC-containing wells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100:1 for 2 h in the absence of antibiotics, followed by 3 h of incubation in 1 ml of 2% FBS–EBM-2 containing 300 μg ml−1 gentamicin and 50 μg ml−1 penicillin G to kill extracellular bacteria. After incubation with antibiotics, HCAEC were lysed with 1 ml of sterile water, and the mixture of lysed HCAEC and S. mutans was plated onto tryptic soy agar to determine the number of intracellular bacteria. The percent invasion for each strain was calculated on the basis of the initial inoculum and the number of intracellular bacteria recovered from HCAEC lysates.

5′ RACE.

To determine the transcription start site of the cnm and pgfS genes, we performed 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) according to the manufacturer's protocol (5′ RACE system; Invitrogen). Briefly, 2 μg of RNA was used as the template for reverse transcription with gene-specific primer 1 (cnmGSP1, pgfsGSP1) (Table 2) and SuperScript II reverse transcriptase, followed by RNase treatment and 3′ poly(dC) tail addition with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase. The dC-tailed cDNA was then PCR amplified using a nested gene-specific primer 2 (cnmGSP2, pgfsGSP2) (Table 2) and an abridged anchor primer (AAP). The transcription start site was determined by sequencing this amplified cDNA.

Phos-tag SDS-PAGE.

To determine the in vivo phosphorylation state of CovR, the OMZ175, ΔcovR, and ΔvicK strains were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth with 0.3% yeast extract (THYE) supplemented with 15 mM MgCl2 to stimulate phosphorylation (42) to an OD600 of 0.6. Cell lysates were prepared by bead beating harvested cells in chilled lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, and 150 mM NaCl with 1× Halt protease inhibitor cocktail [Thermo Scientific]). The lysates were either boiled for 5 min (to remove Asp phosphorylation) or left on ice before mixing with SDS loading buffer for 5 min at room temperature. Twenty micrograms of protein lysate was separated using 10% Phos-tag SDS-PAGE containing 100 μM Phos-tag solution (Wako Chemicals USA Inc.) and 200 μM MnCl2 for 90 min at 150 V and 4°C. The gels were washed in transfer buffer containing 1 mM EDTA for 15 min before transfer to a PVDF membrane. Detection of CovR was performed by Western blotting using anti-CovR primary antibody (21).

Galleria mellonella infection.

Cultures of S. mutans grown overnight were washed twice in sterile saline. Five microliters of the washed culture (∼1 × 108 CFU/ml) was injected into the hemocoel via the last left proleg of G. mellonella larvae (weight, 0.2 to 0.3 g) (48). Larvae injected with heat-inactivated S. mutans OMZ175 (30 min at 80°C) or sterile saline were used as controls. After injection, the larvae were kept in the dark at 37°C, and survival was recorded at selected intervals.

Statistical analysis.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to verify the significance of binding and the invasion assays. Kaplan-Meier killing curves were plotted for G. mellonella infection assays, and estimates of differences in survival were compared using the log rank test. P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIDCR R01 DE022559 to J.A. and J.A.L. and by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP grant 2015/12940-3) to R.O.M.-G. L.A.A. was supported by FAPESP (fellowships 2015/07237-1 and 2016/17216-4).

We also thank Anthony O. Gaca (Harvard Medical School) for providing the pTG001 plasmid.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00141-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banas JA. 2004. Virulence properties of Streptococcus mutans. Front Biosci 9:1267–1277. doi: 10.2741/1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakano K, Ooshima T. 2009. Serotype classification of Streptococcus mutans and its detection outside the oral cavity. Future Microbiol 4:891–902. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nobbs AH, Lamont RJ, Jenkinson HF. 2009. Streptococcus adherence and colonization. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73:407–450. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00014-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakano K, Nomura R, Taniguchi N, Lapirattanakul J, Kojima A, Naka S, Senawongse P, Srisatjaluk R, Gronroos L, Alaluusua S, Matsumoto M, Ooshima T. 2010. Molecular characterization of Streptococcus mutans strains containing the cnm gene encoding a collagen-binding adhesin. Arch Oral Biol 55:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abranches J, Miller JH, Martinez AR, Simpson-Haidaris PJ, Burne RA, Lemos JA. 2011. The collagen-binding protein Cnm is required for Streptococcus mutans adherence to and intracellular invasion of human coronary artery endothelial cells. Infect Immun 79:2277–2284. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00767-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakano K, Hokamura K, Taniguchi N, Wada K, Kudo C, Nomura R, Kojima A, Naka S, Muranaka Y, Thura M, Nakajima A, Masuda K, Nakagawa I, Speziale P, Shimada N, Amano A, Kamisaki Y, Tanaka T, Umemura K, Ooshima T. 2011. The collagen-binding protein of Streptococcus mutans is involved in haemorrhagic stroke. Nat Commun 2:485. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misaki T, Naka S, Hatakeyama R, Fukunaga A, Nomura R, Isozaki T, Nakano K. 2016. Presence of Streptococcus mutans strains harbouring the cnm gene correlates with dental caries status and IgA nephropathy conditions. Sci Rep 6:36455. doi: 10.1038/srep36455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tonomura S, Ihara M, Kawano T, Tanaka T, Okuno Y, Saito S, Friedland RP, Kuriyama N, Nomura R, Watanabe Y, Nakano K, Toyoda K, Nagatsuka K. 2016. Intracerebral hemorrhage and deep microbleeds associated with cnm-positive Streptococcus mutans; a hospital cohort study. Sci Rep 6:20074. doi: 10.1038/srep20074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakano K, Nemoto H, Nomura R, Homma H, Yoshioka H, Shudo Y, Hata H, Toda K, Taniguchi K, Amano A, Ooshima T. 2007. Serotype distribution of Streptococcus mutans a pathogen of dental caries in cardiovascular specimens from Japanese patients. J Med Microbiol 56:551–556. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aviles-Reyes A, Miller JH, Simpson-Haidaris PJ, Lemos JA, Abranches J. 2014. Cnm is a major virulence factor of invasive Streptococcus mutans and part of a conserved three-gene locus. Mol Oral Microbiol 29:11–23. doi: 10.1111/omi.12041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freires IA, Aviles-Reyes A, Kitten T, Simpson-Haidaris PJ, Swartz M, Knight PA, Rosalen PL, Lemos JA, Abranches J. 2017. Heterologous expression of Streptococcus mutans Cnm in Lactococcus lactis promotes intracellular invasion, adhesion to human cardiac tissues and virulence. Virulence 8:18–29. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1195538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller JH, Aviles-Reyes A, Scott-Anne K, Gregoire S, Watson GE, Sampson E, Progulske-Fox A, Koo H, Bowen WH, Lemos JA, Abranches J. 2015. The collagen binding protein Cnm contributes to oral colonization and cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans OMZ175. Infect Immun 83:2001–2010. doi: 10.1128/IAI.03022-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nomura R, Nakano K, Taniguchi N, Lapirattanakul J, Nemoto H, Gronroos L, Alaluusua S, Ooshima T. 2009. Molecular and clinical analyses of the gene encoding the collagen-binding adhesin of Streptococcus mutans. J Med Microbiol 58:469–475. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.007559-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esberg A, Sheng N, Marell L, Claesson R, Persson K, Boren T, Stromberg N. 2017. Streptococcus mutans adhesin biotypes that match and predict individual caries development. EBioMedicine 24:205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aviles-Reyes A, Miller JH, Simpson-Haidaris PJ, Hagen FK, Abranches J, Lemos JA. 2014. Modification of Streptococcus mutans Cnm by PgfS contributes to adhesion, endothelial cell invasion, and virulence. J Bacteriol 196:2789–2797. doi: 10.1128/JB.01783-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biswas I, Drake L, Erkina D, Biswas S. 2008. Involvement of sensor kinases in the stress tolerance response of Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 190:68–77. doi: 10.1128/JB.00990-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chong P, Drake L, Biswas I. 2008. Modulation of covR expression in Streptococcus mutans UA159. J Bacteriol 190:4478–4488. doi: 10.1128/JB.01961-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Senadheera MD, Guggenheim B, Spatafora GA, Huang YC, Choi J, Hung DC, Treglown JS, Goodman SD, Ellen RP, Cvitkovitch DG. 2005. A VicRK signal transduction system in Streptococcus mutans affects gtfBCD, gbpB, and ftf expression, biofilm formation, and genetic competence development. J Bacteriol 187:4064–4076. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.12.4064-4076.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato Y, Yamamoto Y, Kizaki H. 2000. Construction of region-specific partial duplication mutants (merodiploid mutants) to identify the regulatory gene for the glucan-binding protein C gene in vivo in Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol Lett 186:187–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biswas S, Biswas I. 2006. Regulation of the glucosyltransferase (gtfBC) operon by CovR in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 188:988–998. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.3.988-998.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stipp RN, Boisvert H, Smith DJ, Hofling JF, Duncan MJ, Mattos-Graner RO. 2013. CovR and VicRK regulate cell surface biogenesis genes required for biofilm formation in Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One 8:e58271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowen WH, Koo H. 2011. Biology of Streptococcus mutans-derived glucosyltransferases: role in extracellular matrix formation of cariogenic biofilms. Caries Res 45:69–86. doi: 10.1159/000324598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein MI, Hwang G, Santos PH, Campanella OH, Koo H. 2015. Streptococcus mutans-derived extracellular matrix in cariogenic oral biofilms. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 5:10. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2015.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duque C, Stipp RN, Wang B, Smith DJ, Hofling JF, Kuramitsu HK, Duncan MJ, Mattos-Graner RO. 2011. Downregulation of GbpB, a component of the VicRK regulon, affects biofilm formation and cell surface characteristics of Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun 79:786–796. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00725-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alves LA, Harth-Chu EN, Palma TH, Stipp RN, Mariano FS, Hofling JF, Abranches J, Mattos-Graner RO. 2017. The two-component system VicRK regulates functions associated with Streptococcus mutans resistance to complement immunity. Mol Oral Microbiol 32:419–431. doi: 10.1111/omi.12183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alves LA, Nomura R, Mariano FS, Harth-Chu EN, Stipp RN, Nakano K, Mattos-Graner RO. 2016. CovR regulates Streptococcus mutans susceptibility to complement immunity and survival in blood. Infect Immun 84:3206–3219. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00406-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Negrini TC, Duque C, Vizoto NL, Stipp RN, Mariano FS, Hofling JF, Graner E, Mattos-Graner RO. 2012. Influence of VicRK and CovR on the interactions of Streptococcus mutans with phagocytes. Oral Dis 18:485–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang M, Ko YP, Liang X, Ross CL, Liu Q, Murray BE, Hook M. 2013. Collagen-binding microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecule (MSCRAMM) of Gram-positive bacteria inhibit complement activation via the classical pathway. J Biol Chem 288:20520–20531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.454462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Senadheera DB, Cordova M, Ayala EA, Chavez de Paz LE, Singh K, Downey JS, Svensater G, Goodman SD, Cvitkovitch DG. 2012. Regulation of bacteriocin production and cell death by the VicRK signaling system in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 194:1307–1316. doi: 10.1128/JB.06071-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ayala E, Downey JS, Mashburn-Warren L, Senadheera DB, Cvitkovitch DG, Goodman SD. 2014. A biochemical characterization of the DNA binding activity of the response regulator VicR from Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One 9:e108027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khara P, Mohapatra SS, Biswas I. 2018. Role of CovR phosphorylation in gene transcription in Streptococcus mutans. Microbiology 164:704–715. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otsugu M, Nomura R, Matayoshi S, Teramoto N, Nakano K. 2017. Contribution of Streptococcus mutans strains with collagen-binding proteins in the presence of serum to the pathogenesis of infective endocarditis. Infect Immun 85:e00401-. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00401-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song L, Wang W, Conrads G, Rheinberg A, Sztajer H, Reck M, Wagner-Dobler I, Zeng AP. 2013. Genetic variability of mutans streptococci revealed by wide whole-genome sequencing. BMC Genomics 14:430. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cornejo OE, Lefebure T, Bitar PD, Lang P, Richards VP, Eilertson K, Do T, Beighton D, Zeng L, Ahn SJ, Burne RA, Siepel A, Bustamante CD, Stanhope MJ. 2013. Evolutionary and population genomics of the cavity causing bacteria Streptococcus mutans. Mol Biol Evol 30:881–893. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meng P, Lu C, Zhang Q, Lin J, Chen F. 2017. Exploring the genomic diversity and cariogenic differences of Streptococcus mutans strains through pan-genome and comparative genome analysis. Curr Microbiol 74:1200–1209. doi: 10.1007/s00284-017-1305-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dubrac S, Boneca IG, Poupel O, Msadek T. 2007. New insights into the WalK/WalR (YycG/YycF) essential signal transduction pathway reveal a major role in controlling cell wall metabolism and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 189:8257–8269. doi: 10.1128/JB.00645-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dmitriev A, Mohapatra SS, Chong P, Neely M, Biswas S, Biswas I. 2011. CovR-controlled global regulation of gene expression in Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One 6:e20127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Downey JS, Mashburn-Warren L, Ayala EA, Senadheera DB, Hendrickson WK, McCall LW, Sweet JG, Cvitkivicth DG, Spatafora GA, Goodman SD. 2014. In vitro manganese-dependent cross-talk between Streptococcus mutans VicK and GcrR: implications for overlapping stress response pathways. PLoS One 9:e115975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szymanski CM, Wren BW. 2005. Protein glycosylation in bacterial mucosal pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:225–237. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu H, Zeng M, Fives-Taylor P. 2007. The glycan moieties and the N-terminal polypeptide backbone of a fimbria-associated adhesin, Fap1, play distinct roles in the biofilm development of Streptococcus parasanguinis. Infect Immun 75:2181–2188. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01544-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Love RM, McMillan MD, Jenkinson HF. 1997. Invasion of dentinal tubules by oral streptococci is associated with collagen recognition mediated by the antigen I/II family of polypeptides. Infect Immun 65:5157–5164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horstmann N, Saldan M, Sahasrabhojane P, Yao H, Su X, Thompson E, Koller A, Shelburne SA III. 2014. Dual-site phosphorylation of the control of virulence regulator impacts group A streptococcal global gene expression and pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004088. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han TK, Zhang C, Dao ML. 2006. Identification and characterization of collagen-binding activity in Streptococcus mutans wall-associated protein: a possible implication in dental root caries and endocarditis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 343:787–792. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sciotti MA, Chatenay-Rivauday C, Yamodo I, Ogier J. 1997. The N-terminal half part of the oral streptococcal antigen I/IIf contains two distinct functional domains. Adv Exp Med Biol 418:699–701. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1825-3_163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim JN, Stanhope MJ, Burne RA. 2013. Core-gene-encoded peptide regulating virulence-associated traits in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 195:2912–2920. doi: 10.1128/JB.00189-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jung CJ, Zheng QH, Shieh YH, Lin CS, Chia JS. 2009. Streptococcus mutans autolysin AtlA is a fibronectin-binding protein and contributes to bacterial survival in the bloodstream and virulence for infective endocarditis. Mol Microbiol 74:888–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bryan EM, Bae T, Kleerebezem M, Dunny GM. 2000. Improved vectors for nisin-controlled expression in gram-positive bacteria. Plasmid 44:183–190. doi: 10.1006/plas.2000.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kajfasz JK, Rivera-Ramos I, Abranches J, Martinez AR, Rosalen PL, Derr AM, Quivey RG, Lemos JA. 2010. Two Spx proteins modulate stress tolerance, survival, and virulence in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 192:2546–2556. doi: 10.1128/JB.00028-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abranches J, Zeng L, Belanger M, Rodrigues PH, Simpson-Haidaris PJ, Akin D, Dunn WA Jr, Progulske-Fox A, Burne RA. 2009. Invasion of human coronary artery endothelial cells by Streptococcus mutans OMZ175. Oral Microbiol Immunol 24:141–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2008.00487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.