Abstract

Rationale: Previous studies have identified defects in bacterial phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages (AMs) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), but the mechanisms and clinical consequences remain incompletely defined.

Objectives: To examine the effect of COPD on AM phagocytic responses and identify the mechanisms, clinical consequences, and potential for therapeutic manipulation of these defects.

Methods: We isolated AMs and monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) from a cohort of patients with COPD and control subjects within the Medical Research Council COPDMAP consortium and measured phagocytosis of bacteria in relation to opsonic conditions and clinical features.

Measurements and Main Results: COPD AMs and MDMs have impaired phagocytosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae. COPD AMs have a selective defect in uptake of opsonized bacteria, despite the presence of antipneumococcal antibodies in BAL, not observed in MDMs or healthy donor AMs. AM defects in phagocytosis in COPD are significantly associated with exacerbation frequency, isolation of pathogenic bacteria, and health-related quality-of-life scores. Bacterial binding and initial intracellular killing of opsonized bacteria in COPD AMs was not reduced. COPD AMs have reduced transcriptional responses to opsonized bacteria, such as cellular stress responses that include transcriptional modules involving antioxidant defenses and Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2)-regulated genes. Agonists of the cytoprotective transcription factor Nrf2 (sulforaphane and compound 7) reverse defects in phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae and nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae by COPD AMs.

Conclusions: Patients with COPD have clinically relevant defects in opsonic phagocytosis by AMs, associated with impaired transcriptional responses to cellular stress, which are reversed by therapeutic targeting with Nrf2 agonists.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, macrophage, phagocytosis, antioxidant, nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2)

At a Glance Summary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) macrophages have defective phagocytosis, but the mechanism and clinical relevance remain unknown.

What This Study Adds to the Field

COPD alveolar macrophages have a specific defect in opsonic phagocytosis that correlates with clinical phenotype. COPD alveolar macrophages fail to engage an antioxidant transcriptional module after exposure to opsonized bacteria. Agonists of a key transcriptional regulator of antioxidant host defense, Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2), reverse the opsonic phagocytosis defect in COPD and offer a potential therapeutic approach to correct the defect.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic inflammatory lung condition characterized by progressive airflow limitation (1, 2). COPD is associated with increased susceptibility to bacterial airway infection. Exacerbations cause acute worsening of symptoms, leading to hospitalization (3) and to disease progression (4). Approximately 50% of exacerbations are due to bacterial infection (5), and, in a long-term cohort study, the lower airways were chronically colonized with Streptococcus pneumoniae in one-third of patients (6). Individuals living with COPD are also at increased risk of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) with increased mortality, most often caused by S. pneumoniae (7). This suggests that COPD leads to an innate immune defect against S. pneumoniae and other bacteria.

Alveolar macrophages (AMs) are the resident phagocytes enabling bacterial clearance from the lung, but COPD AMs have demonstrated reduced phagocytosis of Haemophilus influenzae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8, 9), and COPD monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) have also shown impaired phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae in previous studies (10). Bacterial phagocytosis by macrophages involves both nonopsonic and opsonic pathways (11, 12). Previous studies of COPD macrophages have examined nonopsonic or complement-mediated phagocytosis, but phagocytosis in the presence of opsonizing antibody has not been studied in detail. A specific defect in opsonic phagocytosis would be particularly relevant to capsulated microorganisms, such as S. pneumoniae, which require opsonization for efficient phagocytosis (13), involving both IgG and complement present in alveolar fluid (14).

We investigated mechanisms underlying phagocytic defects in the COPD lung. In patients with COPD, opsonization fails to enhance AM phagocytosis, although it enhances MDM phagocytosis. The degree of AM opsonic phagocytosis was strongly associated with clinical and microbiological phenotype. AM responses to opsonized S. pneumoniae activated cellular stress transcriptional responses to antioxidant responses, but these were abrogated in COPD AMs. Agonists of the antioxidant transcription factor, nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (NFE2L2) or Nrf2, a prominent component of antioxidant transcriptional responses, corrected the defect in AM opsonic phagocytosis in COPD. Some of the results of these studies were previously reported in the form of an abstract (15).

Methods

Macrophage Donors

Patients with COPD, free from exacerbation, were recruited from the U.K. Medical Research Council (MRC) COPDMAP consortium with written approved consent, as outlined in the online supplement.

Cells and Infection

AMs were isolated from BAL as previously described (13). Cells were more than 95% AMs as assessed by DIFF-QUIK staining (Dade Behring) visualized by light microscopy (Leica DMRB 1000; Leica Microsystems). Human MDMs were differentiated for 14 days from peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from donors (with written informed consent) by using Percoll gradient (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Lonza) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum with low LPS (Lonza). Some cells were incubated with 10 μM sulforaphane, 0.065 μM Compound 7, a selective inhibitor of the KEAP1 (Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1)–Nrf2 interaction (16), or with vehicle control, for 16 hours before challenge with bacteria.

Bacteria

Serotype 14 S. pneumoniae (NCTC 11902; National Collection of Type Cultures) is a serotype commonly causing infection in COPD (17). Stocks were grown as previously described (18). Nontypeable H. influenzae (NTHi; NCTC 1269; National Collection of Type Cultures) was cultured as outlined in the online supplement. Macrophages were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 10:1. S. pneumoniae were opsonized for 15 minutes with immune serum obtained from volunteers vaccinated with pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, and with detectable antibody concentrations against S. pneumoniae, before macrophage challenge (13). Viable intracellular bacteria were measured at 4 hours after challenge as a measure of bacterial internalization using a gentamicin protection assay (GPA) as previously described (19). For assessment of early S. pneumoniae killing, macrophages were challenged for 4 hours before GPA, and additional wells were placed in media containing 0.75 μg/ml vancomycin before GPA at the designated time points.

Bacterial Binding

Bacterial binding and internalization were assessed by fluorescence microscopy (Leica DMRB 1000) (13). Detailed information can be found in the online supplement.

Cell Surface Marker Expression

Cell surface marker expression was measured by flow cytometry, as described in the online supplement.

Transcriptomic Analysis

RNA was extracted and hybridized onto the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were analyzed in R using affyPML and limma (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Enrichment analysis of Gene Ontology (GO) terms using a hypergeometric model and the GOstats package in R was performed for differentially expressed genes. False discovery rates were corrected with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. More detailed information is included in the online supplement.

Western Blot Analysis

Whole-cell extracts were isolated using sodium dodecyl sulfate lysis buffer and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis, as described in the online supplement.

Statistics

Results are recorded as mean and SEM. Sample sizes were informed by SEs obtained from similar assays in prior publications (13, 18). Decisions on use of parametric or nonparametric tests were based on results of D’Agostino-Pearson normality tests. Comparisons were made by paired Student’s t tests, and correlations were determined by Spearman’s test using Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc.). Significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Demographic Data for Macrophage Donors

The demographic features for the COPDMAP macrophage donors are listed in Table 1. The patients with COPD had a significantly greater number of pack-years of cigarette exposure. Sixteen of 42 patients with COPD (38.1%) had a history of frequent exacerbations (≥2/yr). Vaccine history was available in 69%, and of these, 83% of patients with COPD had received a pneumococcal vaccine.

Table 1.

Demographics of Macrophage Donors

| Healthy Nonsmokers | Healthy Ex-smokers | Subjects with COPD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects | 12 | 6 | 42 |

| Age, yr | 56 (43–65) | 58 (48–69) | 66 (53–77) |

| Sex, female/male | 6/6 | 2/4 | 7/35 |

| FEV1, L | 3.19 (2.25–4.77) | 2.99 (2.50–3.70) | 1.88 (1.00–2.72) |

| FEV1, % predicted | 110 (74–127) | 108 (84–121) | 50.8 (32–67) |

| FVC, L | 3.76 (2.25–5.6) | 4.19 (3.45–5.2) | 3.49 (1.86–5.24) |

| GOLD stage* | N/A | N/A | 9 GOLD A |

| 14 GOLD B | |||

| 4 GOLD C | |||

| 10 GOLD D | |||

| Nonfrequent/frequent | N/A | N/A | NF, n = 26 (0 exacerbations, n = 19; 1 exacerbation, n = 7) |

| F, n = 16 (2 exacerbations, n = 3; 3 exacerbations, n = 7; >3 exacerbations, n = 6) | |||

| Pack-years | N/A | 18 (10–35) | 50 (32–67) |

| Smoking status: current/ex/never | 0/0/12 | 0/6/0 | 7/35/0 |

| Inhaled corticosteroid use | 0 | 0 | 35 |

| Vaccine history | N/A | N/A | 24 yes, 5 no, 13 N/A |

| SGRQ total score | N/A | N/A | 39.8 (6–83) |

| CAT | N/A | N/A | 16.3 (4–33) |

| 6-minute-walk distance, m | N/A | N/A | 400 (264–496) |

Definition of abbreviations: CAT = COPD Assessment Test; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; F = frequent; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; MRC = Medical Research Council; N/A = not applicable; NF = nonfrequent; SGRQ = St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

Five donors did not have CAT or MRC data and therefore could not be classified A–D.

COPD AMs Have Selective Defects in Phagocytosis of Opsonized S. pneumoniae

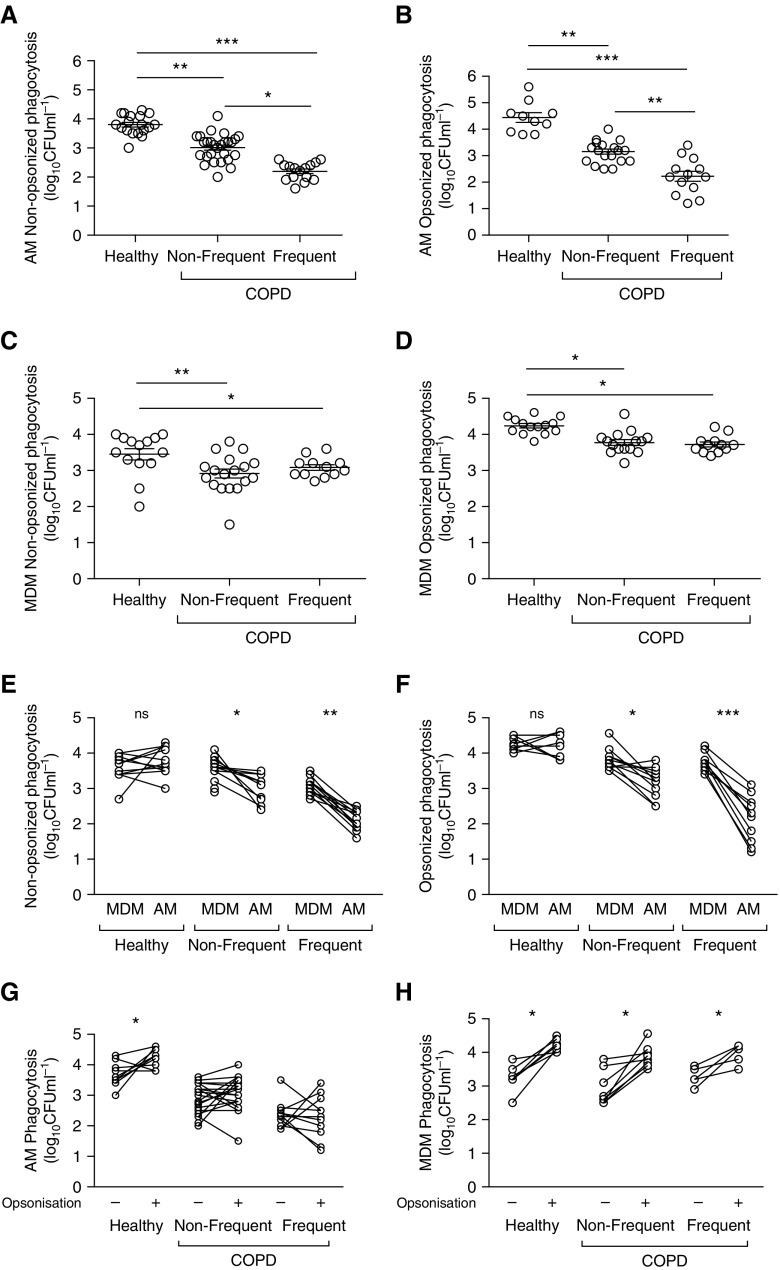

Both COPD AMs and MDMs demonstrated reduced intracellular numbers of S. pneumoniae compared with healthy control subjects, regardless of opsonic conditions (Figures 1A–1D). COPD AMs (but not MDMs) from frequent exacerbators had reduced intracellular bacteria, regardless of opsonic conditions (Figures 1A–1D). Frequent exacerbations was set at two or more exacerbations per year, and, as shown in Figure E1 in the online supplement, patients with only one exacerbation did not have a reduction in bacteria uptake, whereas those with two or more exacerbations per year did. Paired analysis of intracellular bacteria numbers, comparing MDMs with AMs from the same donor, showed that intracellular S. pneumoniae was lower in AMs than in MDMs in COPD (but not in healthy groups), regardless of opsonic condition or exacerbation frequency (Figures 1E and 1F). Opsonization significantly increased numbers of intracellular bacteria in all MDM groups, but it significantly increased numbers only in healthy, not COPD, AMs (Figures 1G and 1H).

Figure 1.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) alveolar macrophages (AMs) show deficient opsonic bacterial phagocytosis that correlates with exacerbation frequency. (A–D) AMs (A and B) or monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) (C and D) from healthy or COPD (nonfrequent [NF] and frequent [F] exacerbators) were challenged with either nonopsonized (A and C) or opsonized (B and D) serotype 14 Streptococcus pneumoniae. At 4 hours after challenge, viable intracellular bacteria were assessed. n values for healthy/COPD-NF/COPD-F, respectively: (A) n = 18/27/15; (B) n = 10/19/13; (C) n = 14/18/12; (D) n = 14/15/12. ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA. (E and F) A pairwise comparison of phagocytosis of nonopsonized (E) and opsonized (F) bacteria in MDMs and AMs from matched donors. ns = not significant. n values for healthy/COPD-NF/COPD-F, respectively: (E) n = 11/12/12; (F) n = 10/11/12. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, paired t test. (G and H) A pairwise comparison of phagocytosis of nonopsonized and opsonized S. pneumoniae in matched AM (G) or MDM (H) donors. n values for healthy/COPD-NF/COPD-F, respectively: (G) n = 10/20/11; (H) n = 7/8/5. *P < 0.05, paired t test.

The number of viable intracellular S. pneumoniae is influenced by both phagocytosis and the rate of early intracellular killing (13). To establish that lower intracellular viable bacteria in COPD AMs were not due to alterations in bactericidal activity, we measured the kinetics of intracellular killing. Opsonization did not alter the rate of bacterial killing in any macrophages (Figures E2A–E2D). Opsonization appropriately increased both the percentage of healthy AM-binding bacteria and the number of internalized bacteria binding per macrophage, but it did not enhance uptake in COPD (Figure E3). Binding of nonopsonized or opsonized S. pneumoniae was not altered by COPD or exacerbation frequency. Surface expression of the Fcγ receptors CD16, CD32, and CD64 was similar in AMs/MDMs of patients with COPD and control subjects (Figures E4A and E4B). Studies have demonstrated a central role for the exchange protein activated by cAMP-1 (Epac-1) in the inhibition of Fcγ receptor–mediated phagocytosis (20). However, AM expression of Epac-1, or of its primary target Rap-1 (21), was unaltered by S. pneumoniae challenge or by COPD (Figures E4C and E4D). Similarly, there was no difference in expression of Rac1, a Rho-family GTP-binding protein that regulates lamellipodia formation and membrane ruffling in Fcγ receptor–mediated phagocytosis in AMs (22).

Because COPD AMs demonstrate a specific defect in opsonic phagocytosis, we confirmed if patient BAL fluid samples had significant concentrations of antipneumococcal antibodies. We measured antibodies against the 13 serotypes included in PREVNAR 13 (Pfizer Limited), a licensed protein conjugate vaccine, using a sensitive multiplex immunoassay. Unconcentrated BAL samples had detectable pneumococcal antibodies to 2.9 ± 0.5 serotypes, and 72% of samples had antibodies against at least one serotype, with a range of 0–9 serotypes. Antibodies were most common to serotype 3 (38%), serotype 14 (45%), and serotype 19A (45%) (see Figure E5). More specifically, for the COPD sample, 73% had detectable antibodies to one or more serotypes.

Decreased Opsonic Phagocytosis in COPD Is Associated with Bacterial Colonization and Correlates with Clinical Features

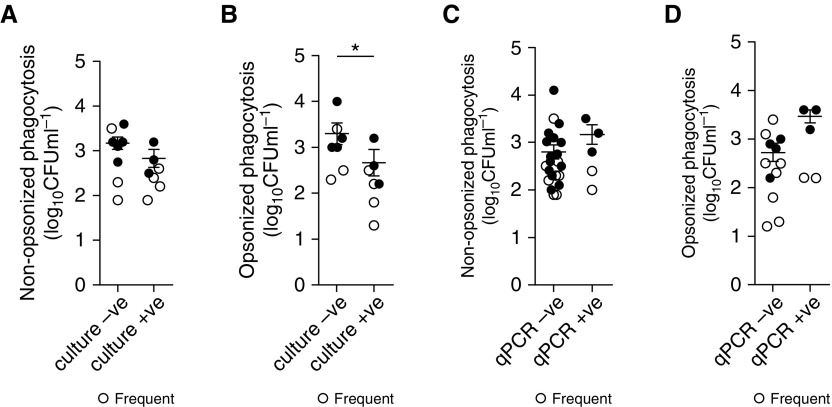

COPD lungs are often colonized with bacteria, most often H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae (23), and colonization is associated with increased exacerbation frequency (6). Because AMs are essential mediators of pulmonary innate immunity (24), we established whether AM phagocytic defects were associated with bacterial colonization. We found that patients with COPD who were culture positive for pathogenic microorganisms in their sputum had significantly lower degrees of AM phagocytosis for opsonized, but not nonopsonized, S. pneumoniae compared with culture-negative patients (Figures 2A and 2B). In contrast, using quantitative PCR to identify pathogenic microorganisms in BAL, we determined that PCR-positive samples were not associated with lesser degrees of opsonic or nonopsonic AM phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae (Figures 2C and 2D).

Figure 2.

Defects in phagocytosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease alveolar macrophages are associated with bacterial colonization in the lung. (A–D) Nonopsonic (A and C) and opsonic (B and D) phagocytosis was stratified into groups dependent on whether the donor had negative (−ve) or positive (+ve) sputum culture (A and B, n = 15 and n = 14, respectively) or −ve or +ve (defined as >104 copies/ml) quantitative PCR of BAL (C and D, n = 27 and n = 26, respectively) results indicative of bacterial colonization, *P < 0.05, Student’s t test. Open circles indicate frequent exacerbations; solid circles indicate nonfrequent exacerbations.

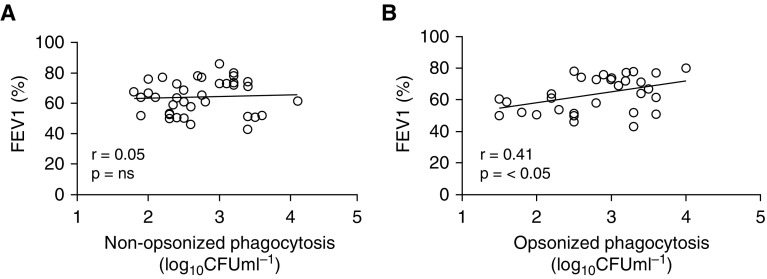

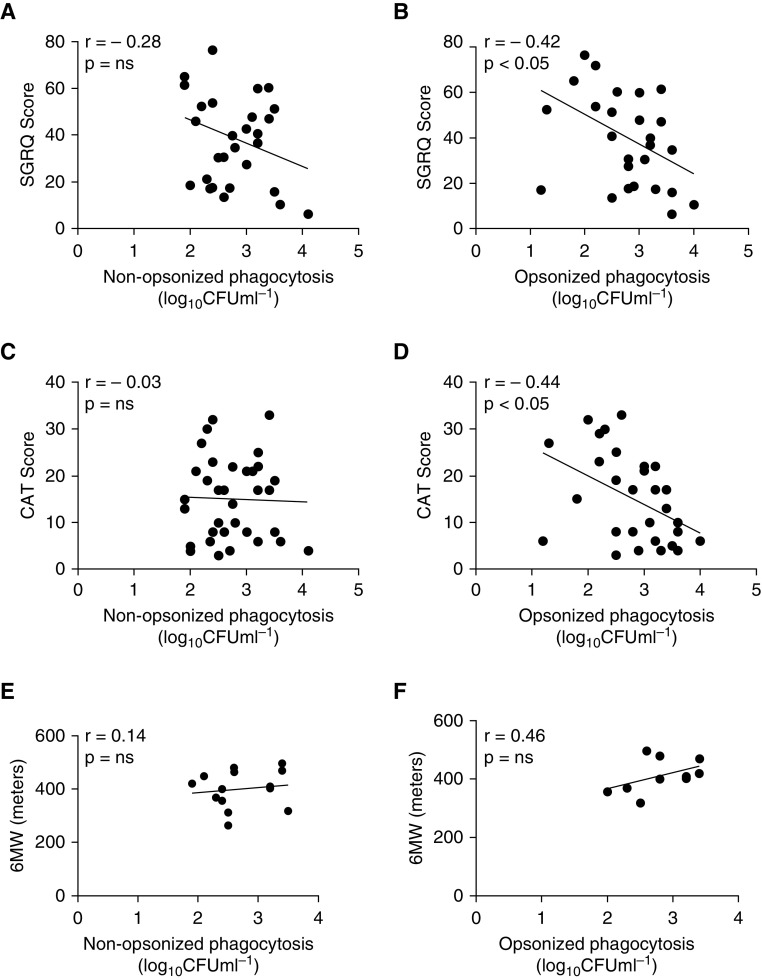

Correlation analysis of nonopsonized and opsonized phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae against FEV1 showed that there was a significant relationship between FEV1 and degrees of opsonic phagocytosis but not of nonopsonic phagocytosis (Figures 3A and 3B). However, because FEV1 correlates poorly with symptoms in COPD (25), we also looked to see if AM phagocytosis degrees were related to scores derived from health-related quality-of-life instruments: the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), the COPD Assessment Test (CAT), or the 6-minute-walk distance. For the SGRQ and CAT scores (although not for the 6-minute-walk distance), there was a significant correlation between impaired opsonic phagocytosis and scores representative of increased symptom severity, but, in contrast, nonopsonic uptake was not correlated with any health-related quality-of-life score, suggesting that it was less tightly associated with COPD symptoms (Figures 4A–4F).

Figure 3.

Opsonic phagocytosis correlates with FEV1. (A) Nonopsonic and (B) opsonic phagocytosis rates were correlated against patient FEV1 score. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) and P values are shown, with correlation deemed significant if P < 0.05. Nonopsonic, n = 36; opsonic, n = 32. ns = not significant.

Figure 4.

Opsonic phagocytosis correlates with markers of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) severity. (A, C, and E) Nonopsonic and (B, D, and F) opsonic rates of phagocytosis were correlated against patient scores for a variety of markers of COPD severity: (A and B) the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) (nonopsonic, n = 29; opsonic, n = 27), (C and D) the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) (nonopsonic, n = 34; opsonic, n = 30), or (E and F) the 6-minute-walk distance (6MW) (nonopsonic, n = 14; opsonic, n = 10). Values for Pearson’s (r) correlation coefficient and P values are shown, with correlation deemed significant if P < 0.05. ns = not significant.

COPD AMs Have Reduced Transcription of Antioxidant Genes Induced in Response to Opsonized Bacteria

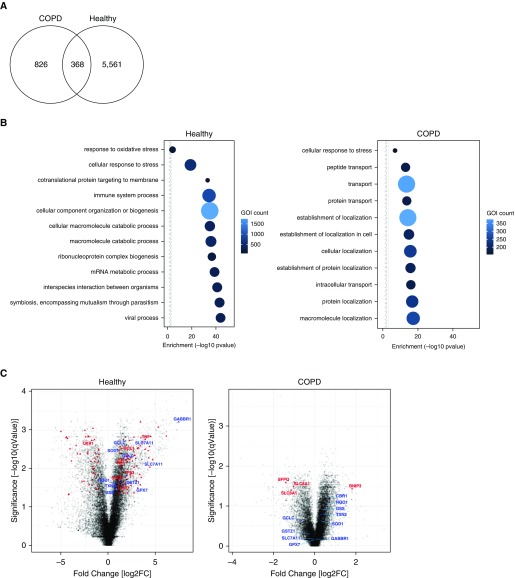

To provide further insights into the mechanisms influencing the selective defect in opsonic phagocytosis in AMs, we next looked at the transcriptional response of AMs to opsonized S. pneumoniae. There were significantly fewer differentially expressed genes in the COPD AMs in response to infection than in healthy AMs (Figure 5A). Tables E1 and E2 show the top 10 upregulated and downregulated gene probes in healthy and COPD AMs, respectively. We reviewed the enriched GO terms and noted fewer terms differentially regulated in COPD and lesser degrees of induction (Figure 5B). We also observed that, within the biological processes differentially regulated, although the GO term relating to the cellular response to stress was prominently enriched in healthy AMs, it comprised significantly fewer components in the COPD AMs (Table E3). Included in this response are a series of genes regulating antioxidant defense, which were prominent in the genes altered in healthy AMs (Figure 5C, Figure E6, and Table E4), but these showed comparatively less differential regulation in COPD. Although these responses are not recognized as a major feature of innate host responses to bacteria, antioxidant responses modulate inflammatory responses. These antioxidant responses are activated by a variety of sources of oxidative stress, including microbicidal responses to bacteria, and baseline reductions in antioxidant responses were previously described in COPD (26).

Figure 5.

Transcriptional response of alveolar macrophages (AMs) reveals less differential gene expression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in response to infection. AMs from healthy subjects or patients with COPD were challenged with opsonized serotype 14 Streptococcus pneumoniae (n = 3 in each group). At 4 hours after challenge, cell total RNA was collected for transcriptional analysis. (A) Venn diagram showing the number of probes differentially expressed in response to infection (moderated t test, <0.05; false discovery rate, <0.05). (B) Plots represent the top 10 enriched Gene Ontology (GO) biological process terms and the cellular response to stress terms; in addition, the response to oxidative stress term is plotted in the healthy AMs. The x-axis represents enrichment by a hypergeometric test [−log10(P value)]. The size of the circle and color represent the number of differentially expressed genes of interest in that term. Figures were generated using NIPA (available from: https://github.com/ADAC-UoN/NIPA). (C) Volcano plots represent the probe sets identified from the transcriptomic analysis. In the left plot, which displays findings for healthy AMs, the red triangles are the differentially expressed probes related to the “Cellular response to stress term” with some representative terms named. In blue are the terms associated with the Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2) pathway in the analysis of healthy AMs. In the right plot, which displays COPD AMs, the red triangles are the differentially expressed probes related to the “Cellular response to stress” GO term. In blue are the terms associated with the Nrf2 pathway seen in the healthy AM analysis. GOI = gene of interest.

Activation of Nrf2 Increases Phagocytosis of Nonopsonized and Opsonized S. pneumoniae in AMs but Not MDMs

Increased oxidative stress in the COPD lung has been associated with impairment of phagocytosis of nonopsonized unencapsulated bacteria and apoptotic bodies (27, 28). The transcription factor Nrf2 is a key regulator of cytoprotective proteins, including antioxidants (29, 30), and treatment of macrophages with a pharmacological activator of Nrf2, sulforaphane, increases phagocytosis of NTHi and P. aeruginosa in COPD AMs (8). Within the differentially expressed genes in AM after pneumococcal challenge, we identified multiple Nrf2-regulated genes in healthy AMs, but these were not differentially regulated in COPD AMs (Figure 5C and Table E5).

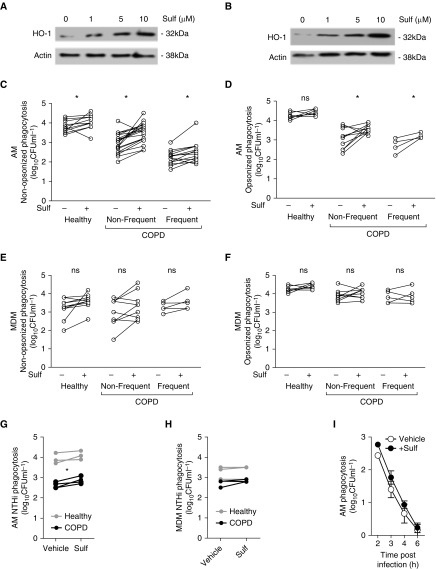

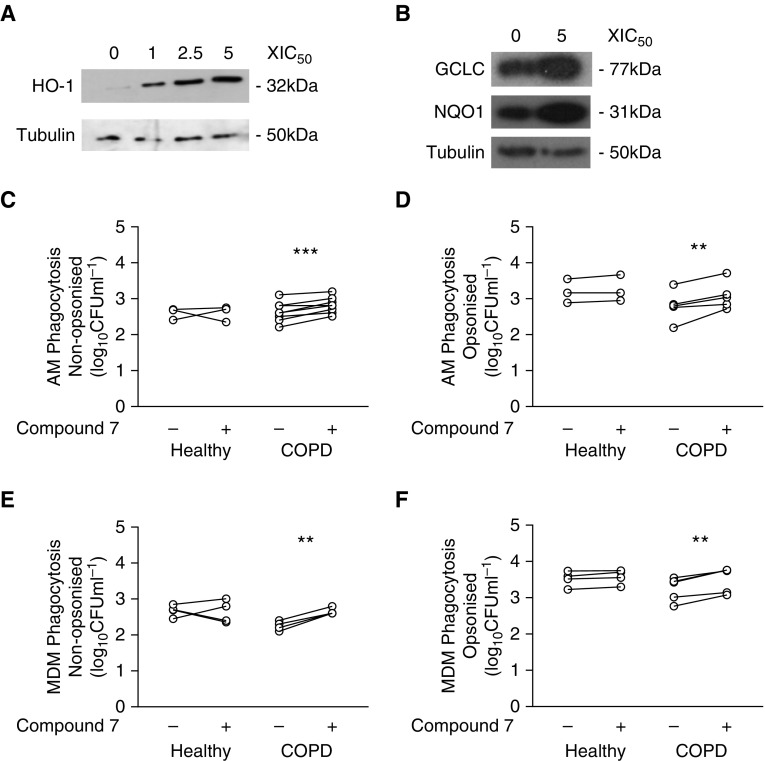

Because we identified impairment of an antioxidant transcriptional module, we next tested whether sulforaphane modulated phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae. We confirmed that sulforaphane activated heme oxygenase (HO)-1, an Nrf2 target gene, in COPD macrophages (Figures 6A and 6B) and did not induce either apoptosis or necrosis in macrophages (Figure E7). Sulforaphane significantly increased numbers of intracellular bacteria after challenge with nonopsonized S. pneumoniae in both healthy and COPD AMs (Figure 6C), but only in COPD (not healthy) AMs after challenge with opsonized S. pneumoniae (Figure 6D). In contrast, we failed to demonstrate an uplift in MDM ingestion under any of the conditions studied (Figures 6E and 6F). To determine if this pattern occurred with other bacteria, we confirmed that sulforaphane also increased intracellular numbers of NTHi in COPD AMs but not in healthy AMs/MDMs or COPD MDMs (Figures 6G and 6H). We also confirmed that sulforaphane did not alter the rate of early intracellular killing of S. pneumoniae in COPD AMs (Figure 6I). Moreover, sulforaphane did not significantly induce Fcγ receptor expression (CD16, CD32, or CD64) in either AMs or MDMs (Figure E8). To determine if the uplift in phagocytosis was sulforaphane specific, cells were also treated with a more specific Nrf2 agonist, Compound 7. This is a recently described potent and selective inhibitor of the KEAP1–Nrf2 protein–protein interaction (16). Treatment with Compound 7 also induced expression of HO-1 in COPD MDMs in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 7A) and, importantly, GCLC (glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit) and NQO1 (NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase 1), two of the Nrf2-regulated targets upregulated by infection, in AMs (Figure 7B). Compound 7 significantly increased phagocytosis of opsonized and nonopsonized S. pneumoniae by COPD (but not healthy) AMs and MDMs (Figures 7C–7F). As with sulforaphane, Compound 7 treatment did not induce cytotoxic effects (Figure E7B). To complete the data set with Compound 7 (and for healthy donors shown in Figure 6G), we added some additional patients recruited outside COPDMAP whose demographics are shown in Table E6. These findings illustrate the potential to reverse opsonic phagocytic defects with Nrf2 agonists.

Figure 6.

Treatment with the Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2) agonist sulforaphane increases nonopsonic and opsonic phagocytosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) alveolar macrophages (AMs) but not in monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs). (A) AMs and (B) MDMs were pretreated with the designated dose of sulforaphane (Sulf) for 16 hours before cells were lysed and probed for expression of heme oxygenase (HO)-1 and actin (n = 3). (C–F) AMs (C and D) or MDMs (E and F) from healthy (H) or COPD nonfrequent (NF) or frequent (F) exacerbators were pretreated with vehicle (Sulf−) or sulforaphane (Sulf+) for 16 hours before cells were challenged with nonopsonized (C and E) or opsonized (D and F) serotype 14 Streptococcus pneumoniae. Four hours after challenge, numbers of intracellular viable bacteria were measured, and n values for H/COPD-NF/COPD-F, respectively, were as follows: (C) n = 11/19/14; (D) n = 8/10/4; (E) n = 9/9/5; (F) n = 8/9/5. *P < 0.05, paired t test. (G and H) AMs (G) and MDMs (H) from patients with COPD or healthy (H) donors were pretreated with sulforaphane before being challenged with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi). Four hours after challenge, the numbers of intracellular viable bacteria were measured, and n values for H/COPD, respectively, were as follows: (G) n = 3/4; (H) n = 3/3. *P < 0.05, paired t test. (I) COPD AMs were pretreated with sulforaphane (+Sulf) before being challenged with nonopsonized serotype 14 S. pneumoniae for 4 hours before extracellular bacteria were killed by the addition of antimicrobials. At the designated time after addition of antimicrobials, viable bacteria in duplicate wells were measured (n = 3), with no significant difference between vehicle and sulforaphane. ns = not significant.

Figure 7.

The Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2) agonist Compound 7 also increases phagocytosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) alveolar macrophages (AMs). (A and B) COPD monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) (A) or AMs (B) were pretreated with the Nrf2 agonist Compound 7 for 16 hours at the designated dose before cells were lysed and probed for the expression of heme oxygenase (HO)-1, GCLC (glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit), or NQO1 (NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase 1) by Western blotting. (C and D) Healthy donor and COPD AMs were pretreated with Compound 7 at 5 × IC50 (0.065 μM) for 16 hours before being challenged with nonopsonized (n = 3 healthy; n = 5 COPD) (C) or opsonized (n = 3 healthy; n = 10 COPD) (D) serotype 14 Streptococcus pneumoniae for 4 hours, after which numbers of intracellular viable bacteria were assessed. **P < 0.01, paired t test. (E and F) Healthy donor and COPD MDMs were pretreated with Compound 7 and challenged with nonopsonized (E) or opsonized (F) S. pneumoniae as was done for AMs. All n = 4. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, paired t test. IC50 = half-maximal inhibitory concentration.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that COPD macrophages have reduced phagocytosis of bacteria. Although we observed defects in MDM phagocytic function, failure to induce phagocytic uplift by opsonization was unique to COPD AMs and was the specific defect that was most predictive of clinical phenotype. COPD AMs exposed to opsonized bacteria had decreased transcriptional responses involving antioxidant defenses. Importantly, AM defects in bacterial uptake were reversed with Nrf2 agonists.

Several prior publications have demonstrated that COPD is associated with impaired macrophage phagocytosis of bacteria and apoptotic cells (8–10, 31). These studies suggest that there is both a local AM defect and a systemic defect in macrophage function, which may arise from a combination of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors. Our study extends prior understanding by showing an additional select defect in AM function that inhibits phagocytosis of opsonized bacteria.

Both complement and immunoglobulin are present in alveolar lining fluid (14). Pneumococcus-specific IgG is detected in human BAL (32) and is required for optimal phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae by AMs (13). Our study also confirms the presence of antipneumococcal antibodies in unconcentrated BAL in a COPD population in which available data showed greater than 80% vaccination uptake and in an age-matched population, some of whom would have had vaccine on the basis of their age. Therefore, a defect in opsonic uptake could reduce the efficacy of vaccination despite the presence of pneumococcal antibodies in the airway. In a murine model, cigarette smoke reduced complement-mediated S. pneumoniae uptake but not phagocytosis of IgG-coated beads (33). Impaired phagocytosis of opsonized S. pneumoniae and other encapsulated bacteria is likely to contribute to COPD pathogenesis. S. pneumoniae remains a leading cause of exacerbations in COPD (5), and in one study, monoculture of S. pneumoniae proved a specific risk factor for exacerbation (17). S. pneumoniae also have indirect effects on exacerbations because they promote growth, biofilm formation, and synergy in inflammatory responses with other bacteria causing exacerbations (34–36). In addition, S. pneumoniae is the major cause of CAP in these patients (37), and COPD increases the susceptibility and risk of complications with CAP (7).

Recent observations involving polymeric immunoglobulin receptor–deficient mice illustrate how bacterial persistence drives inflammation and small airway remodeling in a model of COPD (38). Bacterial colonization of the airways is linked to decline in lung function (6, 39), and recently, bacterial phagocytosis has been shown to correlate with FEV1 in both COPD (40) and severe asthma (41). Reduced phagocytosis of opsonized bacteria by AMs was observed in patients who were culture positive, although PCR positivity in BAL was not associated with the degree of phagocytosis. It would be of interest in the future to determine if opsonic phagocytosis correlates with quantitation of PCR, but our numbers did not allow this analysis. We used a threshold of greater than 104 copies per milliliter to define positivity. On one hand, although this threshold ensures sensitivity and a high negative predictive value in studies on the detection of lower respiratory tract infection due to organisms such as S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae (42, 43), it may underestimate colonization. On the other hand, the detection of colonization by PCR with lower PCR thresholds is problematic, and diagnostic accuracy may be influenced by increasing numbers of false-positive results. Therefore, the sputum detection may have been more predictive of colonization status. The defect in AM phagocytosis of opsonized bacteria was more severe in patients with COPD with frequent exacerbations, a factor associated with more rapid decline in FEV1 (44). This could explain the correlations we observed with more significant impairment of opsonic phagocytosis observed in patients with lower FEV1 or more severe symptoms with quality-of-life assessments. Assessment scales are widely used to describe COPD patient cohorts and stratify them for interventions, such as pulmonary rehabilitation (45), and to predict survival (46). Quality-of-life scales are complementary to FEV1 in describing disability (e.g., MRC dyspnea scale) or severity of dyspnea symptoms (e.g., CAT) in patients living with COPD, and it was noteworthy that the SGRQ and CAT scores correlated with the defect for phagocytosis of opsonized bacteria. FEV1 provides a measure of COPD stage, but it correlates poorly with symptoms (25). This implies that the phagocytic defect may be related both to stage and to symptoms.

Future studies will need to identify if the phagocytic defect for opsonized bacteria is related to a specific receptor pathway or cytoskeletal rearrangement. A prior study identified a defect in macrophage receptor with collagenous structure (MARCO)-mediated phagocytosis in COPD (8). This important study identified impaired phagocytosis of two nonopsonized bacteria (NTHi and P. aeruginosa) in COPD AMs and mice exposed to cigarette smoke and showed that sulforaphane corrected the defect via an Nrf2-dependent mechanism through enhanced MARCO expression. Our study in a population with very few current smokers is consistent with these findings, confirming a defect in phagocytosis of nonopsonized bacteria (S. pneumoniae and NTHi), which is improved by Nrf2 agonists. We extend these findings by showing an additional defect for opsonized S. pneumoniae. In contrast to the study by Harvey and colleagues (8), our study highlights transcriptional changes associated with infection in healthy and COPD AMs rather than the transcriptional effects of sulforaphane, but it also highlights reductions in Nrf2-mediated responses in COPD AMs. The range of particles, including both opsonized and nonopsonized bacteria and apoptotic bodies, for which defects have been identified in COPD argues against involvement of any single receptor system underlying all these defects. Although MARCO likely contributes to defects in uptake of nonopsonized bacteria (8), it would not be anticipated to explain the impairment of opsonized bacteria by AMs. An unbiased approach is more likely to identify mechanisms underpinning the broad systemic defect in phagocytosis and the more localized pulmonary defect for opsonized bacteria.

The transcriptional responses seen in the healthy AMs in response to S. pneumoniae included prominent transcriptional responses involving immunometabolism. The acute responses to bacteria result in a shift to increased glucose uptake and glycolytic metabolism (47), whereas glucose diversion via the pentose phosphate pathway is a well-recognized mechanism of oxidative stress resistance (48). Among differentially expressed metabolic genes increased in healthy but not COPD AMs was sirtuin (silent mating type information regulation 2 homologs)-1, a deacetylase involved in host responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (49). Antioxidant responses were prominently upregulated in healthy AMs after bacterial infection. Nrf2-regulated genes included GCLC, GSTZ-1 (glutathione-S-transferase zeta 1), glutathione peroxidase 7 (GPX7), and the SLC7A11 gene product xCT (light chain subunit of the Xc−) glutamine/cysteine antiporter required, all involved in glutathione maintenance and use; CBR1 (carbonyl reductase 1), NQO1, and TXN2 (thioredoxin 2) detoxifying oxidoreductase enzymes; and SOD1 (superoxide dismutase 1) (48). Foxo-regulated targets, including SOD2, were upregulated, whereas p53 was also upregulated. Of all these antioxidant responses, only p53 was significantly upregulated in COPD AMs after bacterial challenge. We identified upregulation of a series of genes involved in regulation of ubiquitination (including ubiquitin-conjugating E2 enzymes B, D3, and N), a process controlling signaling via pattern recognition receptors, in healthy AMs after bacterial challenge (50). Collectively, these antioxidant responses have the potential to alter cytokine-induced activation of specific phagocytic pathways, expression of receptors or molecules involved in signaling cascades associated with receptors, or the susceptibility of the cytoskeleton to rearrangements altered by oxidative stress required for particular phagocytic pathways. It was noteworthy that the transcriptional response in healthy AMs involved downregulation of the class B scavenger receptor CD36, a receptor for unopsonized particles (51), which was not observed in COPD AMs.

The Nrf2 transcription factor regulates a cluster of antioxidant, cytoprotective, and detoxifying genes and influences susceptibility to COPD in murine models involving cigarette smoke exposure by modifying inflammation and tissue injury (52). We confirmed prior observations suggesting that Nrf2 agonists correct the phagocytic defect in COPD (8), but we extend these by showing that they also modulate phagocytosis of opsonized bacteria. Because this also influenced uptake of nonopsonized particles, it is likely that Nrf2 agonists have pleiotropic effects in the modulation of phagocytosis. Nrf2 agonists represent a promising class of agents with which to modulate oxidative stress in conditions such as COPD, particularly with the development of highly selective agents that bind to the Kelch domain of KEAP1 and prevent Nrf2 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (16). Whereas sulforaphane activates Nrf2 by targeting cysteine residues in the BTB domain of KEAP1 and can potentially interact with other targets (53), we demonstrate significant enhancement of phagocytosis in COPD macrophages with the selective Nrf2 agonist Compound 7, suggesting that this could represent a potent pharmacological approach with which to correct the COPD-associated defects in phagocytosis.

In conclusion, we have identified that, although COPD induces a systemic defect in a range of forms of phagocytosis, a specific defect in phagocytosis of opsonized bacteria is observed specifically in AMs and correlates closely with clinical phenotype in COPD. Moreover, this defect is amenable to therapeutic targeting with novel and selective inhibitors of the KEAP1–Nrf2 protein–protein interaction.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Prof. Ian Sabroe for setting up ethics approvals for research bronchoscopies and for discussions on pulmonary host defense. This report is independent research supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) South Manchester Respiratory and Allergy Clinical Research Facility at University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust and the NIHR Clinical Research Facility at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Funded by the Medical Research Council and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry through support for the COPDMAP consortium, and by Wellcome Trust (WT) grant 076945 (D.H.D.) and WT Clinical Research Training Fellowship 104437/Z/14/Z (J.C.).

Author Contributions: M.A.B., J.M., and E.R.: performed killing assays, flow cytometry, and microscopy and collected data; M.A.B., J.M., and J.C.: produced figures; R.C.B., E.R., U.K., P.C., and D.S.: coordinated and performed bronchoscopies to obtain patient samples; R.C.B., U.K., and G.B.: performed clinical phenotyping; J.C., E.R., and R.D.E.: performed transcriptomic analysis; I.T. and G.A.M.B.: provided multiplex immunoassays on BAL; W.R. and Y.S.: provided compounds and input into experimental design; G.D., J.A.W., S.R.W., I.K., L.E.D., P.J.B., D.S., and C.E.B.: coordinated collection of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patient cohort and control subjects, shared expertise in assays, and provided reagents; M.A.B., M.K.B.W., and D.H.D.: designed and conceived of the experiments; M.A.B., M.K.B.W., and D.H.D.: wrote the manuscript with input from all other authors.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201705-0903OC on March 16, 2018

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: on behalf of COPDMAP

References

- 1.Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report: GOLD Executive Summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:557–582. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes PJ. Alveolar macrophages in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2004 50 Online Pub:OL627–OL637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, Locantore N, Müllerova H, Tal-Singer R, et al. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) Investigators. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1128–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Paul EA, Bestall JC, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Effect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1418–1422. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9709032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sapey E, Stockley RA. COPD exacerbations. 2: aetiology. Thorax. 2006;61:250–258. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.041822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel IS, Seemungal TA, Wilks M, Lloyd-Owen SJ, Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA. Relationship between bacterial colonisation and the frequency, character, and severity of COPD exacerbations. Thorax. 2002;57:759–764. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.9.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Restrepo MI, Mortensen EM, Pugh JA, Anzueto A. COPD is associated with increased mortality in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:346–351. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00131905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey CJ, Thimmulappa RK, Sethi S, Kong X, Yarmus L, Brown RH, et al. Targeting Nrf2 signaling improves bacterial clearance by alveolar macrophages in patients with COPD and in a mouse model. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:78ra32. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berenson CS, Wrona CT, Grove LJ, Maloney J, Garlipp MA, Wallace PK, et al. Impaired alveolar macrophage response to Haemophilus antigens in chronic obstructive lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:31–40. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1461OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor AE, Finney-Hayward TK, Quint JK, Thomas CM, Tudhope SJ, Wedzicha JA, et al. Defective macrophage phagocytosis of bacteria in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:1039–1047. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00036709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palecanda A, Kobzik L. Receptors for unopsonized particles: the role of alveolar macrophage scavenger receptors. Curr Mol Med. 2001;1:589–595. doi: 10.2174/1566524013363384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aderem A, Underhill DM. Mechanisms of phagocytosis in macrophages. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:593–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon SB, Irving GR, Lawson RA, Lee ME, Read RC. Intracellular trafficking and killing of Streptococcus pneumoniae by human alveolar macrophages are influenced by opsonins. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2286–2293. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2286-2293.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicod LP. Lung defences: an overview. Eur Respir Rev. 2005;14:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bewley MA, Budd R, Singh D, Barnes PJ, Donnelly LE, Dockrell DH, et al. COPD alveolar macrophages have a defect in opsonic phagocytosis of serotype 14 Streptococcus pneumoniae [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:A1011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies TG, Wixted WE, Coyle JE, Griffiths-Jones C, Hearn K, McMenamin R, et al. Monoacidic inhibitors of the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (KEAP1:NRF2) protein–protein interaction with high cell potency identified by fragment-based discovery. J Med Chem. 2016;59:3991–4006. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bogaert D, van der Valk P, Ramdin R, Sluijter M, Monninkhof E, Hendrix R, et al. Host-pathogen interaction during pneumococcal infection in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Infect Immun. 2004;72:818–823. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.2.818-823.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dockrell DH, Lee M, Lynch DH, Read RC. Immune-mediated phagocytosis and killing of Streptococcus pneumoniae are associated with direct and bystander macrophage apoptosis. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:713–722. doi: 10.1086/323084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marriott HM, Ali F, Read RC, Mitchell TJ, Whyte MK, Dockrell DH. Nitric oxide levels regulate macrophage commitment to apoptosis or necrosis during pneumococcal infection. FASEB J. 2004;18:1126–1128. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1450fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aronoff DM, Canetti C, Serezani CH, Luo M, Peters-Golden M. Cutting edge: macrophage inhibition by cyclic AMP (cAMP): differential roles of protein kinase A and exchange protein directly activated by cAMP-1. J Immunol. 2005;174:595–599. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Rooij J, Zwartkruis FJ, Verheijen MH, Cool RH, Nijman SM, Wittinghofer A, et al. Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature. 1998;396:474–477. doi: 10.1038/24884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castellano F, Montcourrier P, Chavrier P. Membrane recruitment of Rac1 triggers phagocytosis. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2955–2961. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.17.2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wedzicha JA, Donaldson GC. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Care. 2003;48:1204–1213. [Discussion, p. 1213–1215.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dockrell DH, Whyte MKB, Mitchell TJ. Pneumococcal pneumonia: mechanisms of infection and resolution. Chest. 2012;142:482–491. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agusti A, Calverley PM, Celli B, Coxson HO, Edwards LD, Lomas DA, et al. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) investigators. Characterisation of COPD heterogeneity in the ECLIPSE cohort. Respir Res. 2010;11:122. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuder RM, Petrache I. Pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2749–2755. doi: 10.1172/JCI60324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martí-Lliteras P, Regueiro V, Morey P, Hood DW, Saus C, Sauleda J, et al. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae clearance by alveolar macrophages is impaired by exposure to cigarette smoke. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4232–4242. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00305-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richens TR, Linderman DJ, Horstmann SA, Lambert C, Xiao YQ, Keith RL, et al. Cigarette smoke impairs clearance of apoptotic cells through oxidant-dependent activation of RhoA. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:1011–1021. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200807-1148OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goven D, Boutten A, Leçon-Malas V, Marchal-Sommé J, Amara N, Crestani B, et al. Altered Nrf2/Keap1-Bach1 equilibrium in pulmonary emphysema. Thorax. 2008;63:916–924. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.091181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao H, Eguchi S, Alam A, Ma D. The role of nuclear factor-erythroid 2 related factor 2 (Nrf-2) in the protection against lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2017;312:L155–L162. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00449.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hodge S, Hodge G, Scicchitano R, Reynolds PN, Holmes M. Alveolar macrophages from subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are deficient in their ability to phagocytose apoptotic airway epithelial cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2003;81:289–296. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2003.t01-1-01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eagan R, Twigg HL, III, French N, Musaya J, Day RB, Zijlstra EE, et al. Lung fluid immunoglobulin from HIV-infected subjects has impaired opsonic function against pneumococci. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1632–1638. doi: 10.1086/518133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phipps JC, Aronoff DM, Curtis JL, Goel D, O’Brien E, Mancuso P. Cigarette smoke exposure impairs pulmonary bacterial clearance and alveolar macrophage complement-mediated phagocytosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2010;78:1214–1220. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00963-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bosch AA, Biesbroek G, Trzcinski K, Sanders EA, Bogaert D. Viral and bacterial interactions in the upper respiratory tract. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003057. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratner AJ, Aguilar JL, Shchepetov M, Lysenko ES, Weiser JN. Nod1 mediates cytoplasmic sensing of combinations of extracellular bacteria. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:1343–1351. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tikhomirova A, Kidd SP. Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae: living together in a biofilm. Pathog Dis. 2013;69:114–126. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torres A, Dorca J, Zalacaín R, Bello S, El-Ebiary M, Molinos L, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a Spanish multicenter study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:1456–1461. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.5.8912764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richmond BW, Brucker RM, Han W, Du RH, Zhang Y, Cheng DS, et al. Airway bacteria drive a progressive COPD-like phenotype in mice with polymeric immunoglobulin receptor deficiency. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11240. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hill AT, Campbell EJ, Hill SL, Bayley DL, Stockley RA. Association between airway bacterial load and markers of airway inflammation in patients with stable chronic bronchitis. Am J Med. 2000;109:288–295. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berenson CS, Kruzel RL, Eberhardt E, Sethi S. Phagocytic dysfunction of human alveolar macrophages and severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:2036–2045. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liang Z, Zhang Q, Thomas CM, Chana KK, Gibeon D, Barnes PJ, et al. Impaired macrophage phagocytosis of bacteria in severe asthma. Respir Res. 2014;15:72. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blaschke AJ. Interpreting assays for the detection of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 4):S331–S337. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abdeldaim GM, Strålin K, Korsgaard J, Blomberg J, Welinder-Olsson C, Herrmann B. Multiplex quantitative PCR for detection of lower respiratory tract infection and meningitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria meningitidis. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:310. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donaldson GC, Seemungal TA, Bhowmik A, Wedzicha JA. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002;57:847–852. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.10.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wedzicha JA, Bestall JC, Garrod R, Garnham R, Paul EA, Jones PW. Randomized controlled trial of pulmonary rehabilitation in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients, stratified with the MRC dyspnoea scale. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:363–369. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12020363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nishimura K, Izumi T, Tsukino M, Oga T. Dyspnea is a better predictor of 5-year survival than airway obstruction in patients with COPD. Chest. 2002;121:1434–1440. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J, Palsson-McDermott EM, McGettrick AF, Goel G, et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1β through HIF-1α. Nature. 2013;496:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature11986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gorrini C, Harris IS, Mak TW. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:931–947. doi: 10.1038/nrd4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng CY, Gutierrez NM, Marzuki MB, Lu X, Foreman TW, Paleja B, et al. Host sirtuin 1 regulates mycobacterial immunopathogenesis and represents a therapeutic target against tuberculosis. Sci Immunol. 2017;2:eaaj1789. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaj1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zinngrebe J, Montinaro A, Peltzer N, Walczak H. Ubiquitin in the immune system. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:28–45. doi: 10.1002/embr.201338025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Febbraio M, Hajjar DP, Silverstein RL. CD36: a class B scavenger receptor involved in angiogenesis, atherosclerosis, inflammation, and lipid metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:785–791. doi: 10.1172/JCI14006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rangasamy T, Cho CY, Thimmulappa RK, Zhen L, Srisuma SS, Kensler TW, et al. Genetic ablation of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1248–1259. doi: 10.1172/JCI21146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu C, Eggler AL, Mesecar AD, van Breemen RB. Modification of Keap1 cysteine residues by sulforaphane. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:515–521. doi: 10.1021/tx100389r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]