Abstract

In this work, six complexes (2–7) of Cr(III) and Co(II) transition metals with triazole ligands were synthesized and characterized. In addition, a new ligand, 3,5-bis(1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmethyl)toluene (1), was synthesized and full characterized. The complexes were obtained as air-stable solids and characterized by melting point, electrical conductivity, thermogravimetric analysis, and Raman, infrared and ultraviolet/visible spectroscopy. The analyses and spectral data showed that complexes 3–7 had 1:1 (M:L) stoichiometries and octahedral geometries, while 2 had a 1:2 (M:L) ratio, which was supported by DFT calculations. The complexes and their respective ligands were evaluated against bacterial and fungal strains with clinical relevance. All the complexes showed higher antibacterial and antifungal activities than the free ligands. The complexes were more active against fungi than against bacteria. The activities of the chromium complexes against Candida tropicalis are of great interest, as they showed minimum inhibitory concentration 50 (MIC50) values between 7.8 and 15.6 μg mL−1. Complexes 5 and 6 showed little effect on Vero cells, indicating that they are not cytotoxic. These results can provide an important platform for the design of new compounds with antibacterial and antifungal activities.

Keywords: triazole ligands, cobalt(II) and chromium(III) complexes, antibacterial activity, antifungal activity

1. Introduction

Bacteria and fungi, due to their high rate of development and adaptation, develop resistance to currently used drugs for the treatment of infectious diseases, leading to global public health problems [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Azole-derived compounds have been widely used for the treatment of fungal diseases due to their properties including broad spectrum of action, chemical stability and oral bioavailability. The mechanism of action of azoles against fungi is based on the inhibition of ergosterol [12]. Compared to azole derivatives, triazole compounds exhibit higher antifungal activity and wider spectrum of action [13]. Azoles also show antibacterial activity, inhibiting the enoyl acyl carrier protein reductase [14]. Furthermore, triazole complexes showed very good antimicrobial [15] and antitumor [16] activities. The combination of metals and azoles is a promising strategy to develop new efficient drugs, even against drug-resistant pathogens [17,18,19,20,21,22]. The development of these new drugs is related to the complexation of azole derivatives with transition metals that have low toxicity and are biocompatible [18,23,24]. Previous studies demonstrated that the resulting complexes may have higher antimicrobial activity than the corresponding free azole ligands, and, in some cases, exceeding that of standard test substances (nystatin) [25,26]. In this context, we previously studied the antibacterial and antifungal activities of cobalt(II) and copper(II) complexes derived from benzotriazole, which showed higher antimicrobial activities than the free ligands [24,27]. In line with our results, Sumrra et al. recently reported that complexes derived from triazole had antibacterial and antifungal activities higher than the corresponding ligands [28]. Two well-known theories have been presented to explain the increase in the activity in the complexes with respect to the free ligands (the overtone’s concept [17] and Tweedy’s chelation theory [29]). The coordination of triazoles to metal centers could be an interesting approach for achieving antibacterial and antifungal activities with lower concentrations of the complexes. In this work, we report the synthesis and characterization of new chromium(III) and cobalt(II) complexes derived from triazole ligands and their antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic activities.

2. Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Ligand (1)

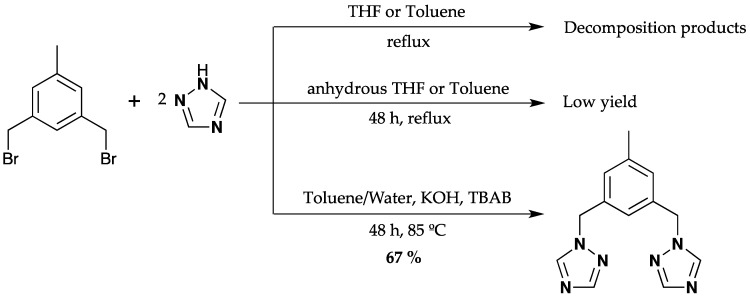

Initially, we tried to prepare the ligand 3,5-bis(1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmethyl)toluene by the direct reaction of 1,3-bis(bromomethyl)toluene with 1H-1,2,4-triazole and using THF and toluene (not anhydrous) as solvents, we obtained a mixture of decomposition products observed by NMR, which were not characterized. Later, the reaction was carried out in an inert atmosphere (nitrogen) using standard Schlenk techniques and anhydrous toluene, which afforded 1 in low yield (5%). Then, the ligand was prepared by a phase-transfer catalyzed reaction of 1,3-bis(bromomethyl)toluene with 1H-1,2,4-triazole followed by thin-layer chromatography (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the ligand (1).

The ligand was isolated as a white, air-stable solid in high yield. It was characterized by elemental analysis, mass spectrometry, and 1H and 13C-NMR, FTIR, UV-Visible and Raman spectroscopy. The 1H and 13C-NMR chemical shifts were assigned with the aid of DEPT 135 and HSQC experiments. The 1H-NMR spectrum show the methylene groups (CH2) between the central aromatic ring and the triazoles at 5.35 ppm, and the methyl group (CH3) of the toluene appears at 2.25 ppm. The three protons of toluene ring were observed between 7.02 and 8.63 ppm. This assignment was confirmed by the integrals of the peaks (Figures S3–S6 in the Supplementary Materials). The solid-state FTIR spectrum showed bands between 1346 and 1608 cm−1. The bands at 1504 and 1384 cm−1 were assigned to the stretching of the C=C and C=N bonds, respectively [30] (Figure S14 in the Supplementary Materials).

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of Metal Complexes

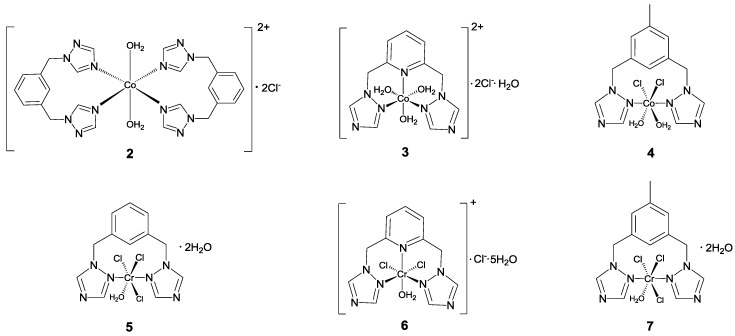

The key to the synthesis of these complexes was the choice of a suitable solvent in each reaction (Figure 1). The reactions were carried out in acetone, which dissolved both the ligand and the starting saltsbut did not solubilize the final complex. In all cases, almost immediate precipitation of the complexes was observed, and the products were washed with acetone.

Figure 1.

Possible structures of the complexes under study.

In the case of chromium complexes 5–7, reactions similar to those used to obtain the cobalt complexes were carried out. When the respective ligand was mixed with the chromium salt, 5–7 immediately precipitated. These complexes were isolated as green, non-hygroscopic, air-stable solids.

Electrical conductivity measurements were made for all the complexes and starting salts of each metal using DMSO as the solvent. For the cobalt salt, a conductivity of 48.0 µS was obtained, and the conductivity of the chromium salt was 40.2 µS. When comparing these values with those obtained for the cobalt complexes, the conductivities of 2 (52.9 µS) and 3 (50.5 µS) were higher (Table 1).

Table 1.

Electrical conductivity for 2–7 and starting salts.

| Compound | Conductivity (Ω−1 cm2 mol−1) | Type of Electrolyte (In Solution) |

|---|---|---|

| CoCl2·6H2O | 48.0 | 2:1 |

| 2 | 52.9 | 2:1 |

| 3 | 50.5 | 2:1 |

| 4 | 43.3 | No electrolyte |

| CrCl3·6H2O | 40.2 | 1:1 |

| 5 | 24.4 | No electrolyte |

| 6 | 30.3 | 1:1 |

| 7 | 27.4 | No electrolyte |

This result is probably due to the electron mobility in the π-conjugated systems of the ligands and to the presence of ionic species.

On the other hand, 4 showed a lower conductivity than that of the free cobalt salt, which indicates that this complex does not exist as electrolytes in solution [31]. The conductivity values observed for 5–7 were lower than that obtained with the initial chromium salt, which may be associated with the absence of ionic species. Although, it has been reported that showing conductivity values between 23 and 42 µS when dissolved in DMSO is characteristic of electrolyte complexes with 1:1 ratios [31]. Taking into account the conductivity results, complexes 2, 3 and 6 are probably electrolytes containing chlorides as the counterions.

2.2.1. FTIR Spectroscopy

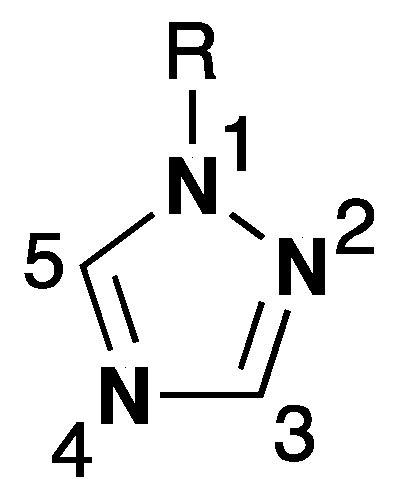

The obtained complexes were analyzed by infrared spectroscopy to observe the shifts of certain bands relative to those of the free ligands following coordination to the metal center. (Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials) summarizes the assignment of the important bands in the complexes compared to those of the free ligands. Figure 2 shows the structure of 1H-1,2,4-triazolewith its respective atom numbering to facilitate the discussion of the spectra.

Figure 2.

Atom numbering for signal assignment for 1,2,4-triazole.

In the case of L1 and its complexes (2 and 5), a shift in the band associated with the stretching of the bond (N-C) between a carbon and a nitrogen atom of the free 1,2,4-triazole was observed [32]; for L1, the band was at 1138 cm−1, while for 2 and 5 this band is shift to lower wavenumbers (1128 cm−1 and 1123 cm−1, respectively).

Such results indicate greater rigidity in the chemical bonds in the all complexes confirming the coordination of the metals to the N of the azole [27,33]. Bands are also observed at 3435 and 3429 cm−1 for 2 and 5, respectively (Figures S9 and S10 in Supplementary Materials), that correspond to the stretches of the bond (O-H) in water molecules [34]. Due to the intensity and width of these bands, it can be inferred that in 2, the H2O molecules are coordinated to the metal center, while for the chromium complex (5), the band is associated with waters of hydration.

For L2 and its complexes (3 and 6), were observed three interesting bands that can give information on how the ligand is coordinated to the metal center. First, a shift of the C-N band of the triazole was observed [32]; in the free ligand it appears at 1141 cm−1, while for 3 and 6 it appears at 1125 cm−1. Additionally, a second band that appears in the spectrum of the free ligand at 1273 cm−1 and was assigned to the N-N bond of the triazole was observed in the spectra of 3 and 6 at 1277 and 1283 cm−1, respectively (Figures S12 and S13 in the Supplementary Materials). This result confirms the possible coordination to the metal center via N2 of the triazole. The third band of interest is associated with the stretching N=C of the pyridine [35]; it was observed in the spectrum of L2 at 1512 cm−1 and at 1524 and 1533 cm−1 in those of 3 and 6, respectively. This allows us to evaluate the coordination of the nitrogen of the pyridine to the metal center. Bands associated with waters molecules of hydration were also found at 3402 cm−1 (3) and 3379 cm−1 (6). (Calculated at 3430 and 3354 cm−1, respectively, from DFT calculations). A slight shift in the band associated with the tension of the triazole ring in 1 (Exp. 891 cm−1; Calc. 830 cm−1) was observed compared with the same bands of complexes 4 and 7 (Exp. 881 and 887 cm−1, respectively, Figures S15 and S16 in the Supplementary Materials; Calc. 840 and 833 cm−1), indicating a decrease in the rigidity of this ring. The band indicative of the C-N bond of the triazole in 1 is observed at 1134 cm−1, and for 4 and 7 the band is shifted to lower wavenumbers (1128 and 1125 cm−1, respectively, Calc. 1089 and 1065 cm−1) due to the decrease in the vibrational energy of this bond by the coordination of N2 of the triazole to the metal center. It was also possible to observe a shift to greater wavenumber in the N-N triazole band, which for the free ligand (1) appears at 1261 cm−1 and for the complexes appears at 1279 cm−1 (4) and 1285 cm−1 (7) (Calculated at 1240 and 1232 cm−1). In the spectra of these complexes, bands corresponding to the bond (O-H) in water molecules are observed at 3412 cm−1 (4) and 3375 cm−1 (7) [34], and due to the intensity and width of these bands, it can be inferred that in 4, the H2O molecules are coordinated to the metal center, while for 9, the band is associated with watersmolecules of hydration.

It should be noted that for all complexes (2–7), a band associated with the M-OH2 bond was observed between 1600–1630 cm−1 [35], and this result gives an indication of the presence of coordination water molecules.

2.2.2. Raman Spectroscopy

Triazole, ligands and the obtained complexes were analyzed by Raman spectroscopy to observe the shifts in the bands of free ligands following coordination to the metal center (Supplementary Materials).

In the complexes, some bands assigned to the N-H bond were not observed at 1481, 977 and 918 cm−1, assigned to the N-H bond indicating L1, 2 and 5 were successfully prepared.

Bands were observed in the zone between 1500 and 900 cm−1 in the spectra of L1, 2 and 5, and these bands corresponded to the N-C bond of the triazole [36,37]. These bands are shifted towards lower wavenumbers in the spectra of the complexes, which indicated a decrease in the rigidity of the triazolic ring and confirmed the coordination of the metal to the N of the triazole. In addition, the bands at 1431 and 1171 cm−1 in the spectrum of L1 did not show considerable shifting in the spectra of the complexes.

On the other hand, the bands observed at 274 cm−1 (3) and 266 cm−1 (6) are assigned to the vibration (O-H) of both coordinated water and watersmolecules of hydration.

For L2 and its complexes 3 and 6, was observed an interesting band from the N-N bond, which can indicate how the ligand is coordinated to the metal center [36]. This band appears to shift to higher wavenumbers in the spectra of the complexes compared to the that of the free ligand. This result suggests the coordination of the metal to N2 of the triazole. In addition, the band at 1423 cm−1 associated with the stretching of the C=N bond of the pyridine in L2 is shifted to 1430 cm−1 (3) and 1425 cm−1 (6), indicating the coordination of the nitrogen of the pyridine to the metal center.

In the spectra of ligand 1 and its complexes (4 and 7), we observed shifts in some of the bands. These bands appear in the spectrum of 1 at 1496 cm−1 and 533 cm−1, and in that of 4, they are at 1464 cm−1 and 522 cm−1, and in that of 7, they are at 1472 cm−1 and 518 cm−1, respectively. These bands are due to the N-C bond of the triazole and confirmed the coordination of the metal to the triazole

Two bands of interest were observed at 1370 and 1013 cm−1 for 1, and they shift to 1358 and 996 cm−1 in the spectrum of 4, and at 1355 cm−1 and 997 cm−1 in that of 7. The first band is assigned to the N-C bond and the second to the N-N bond of the triazole, and these bands indicate that the coordination is via N2 of the triazole.

2.2.3. UV/Vis Spectroscopy

The UV-Vis spectra were recorded in DMSO to study the electronic properties of the complexes and to relate the properties to the possible structures. Table 2 shows some of the bands for the starting salts, ligands and complexes 2–7 that were observed in their UV/Vis spectra. For all complexes, one or two bands between 200 and 300 nm corresponding to the transitions between the π-π* orbitals of the ligand were observed. In addition, for the complexes, the most intense bands were observed in the UV zone and were not shifted relative to the bands of the free ligand, and they only increased in intensity due to the interaction of the orbitals of the ligand with those of the metal.

Table 2.

Some bands for the starting salts, ligands and complexes 2–7 observed in their UV/Vis spectra.

| Transition (nm) (ε(M−1 cm−1)) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV | Vis | |||

| Compound | ν 1 | ν 2 | ν 1 | ν 2 |

| L1 | 263(266) | |||

| 2 | 262(784) | 615(66) | 678(116) | |

| 5 | 260(3672) | |||

| L2 | 264(4423) | |||

| 3 | 264(3317) | 615(41) | 677(79) | |

| 6 | 263(7081) | |||

| 1 | 267(297) | 276(236) | ||

| 4 | 268(556) | 276(478) | 615(7) | 675(26) |

| 7 | 259(2141) | |||

| CoCl2·6H2O | 238(73) | 266(64) | 614(41) | 678(81) |

| CrCl3·6H2O | 260(2764) | |||

In the spectra of the cobalt(II) salt and its complexes (2–4), bands at 600–700 nm were observed, and these bands may be assigned to the 4T1g (F) ← 4T1g (P) transitions in a distorted octahedral geometry in solution [38].

Chromium complexes 5–7 had a green color in both the solid and solution phases. These compounds showed intense bands in the UV region of their spectra, whereas in the region between 400 and 500 nm, no bands were observed. In comparing the spectra of cobalt(II) complex 6 and L2, a small hypsochromic shift was observed. This can be explained by the charge transfer transitions of the metal to the ligand [27,33].

2.2.4. Thermal Analysis

The stages of decomposition and temperature ranges of the complexes are given in (Table S5 in the Supplementary Materials). All results are proposed based the probable mass losses because detection of the decomposition products was not possible. For all the complexes, a final residue containing metal and chlorine was observed. In addition, the thermograms show a decomposition temperature above 600 °C. TGA and derivative thermogravimetric analysis data are shown in the Supplementary Materials. In the case of 2–4, the loss of an organic fragment was found at temperatures greater than 200 °C.

For 2, a weight reduction of 44% was observed at 238–342 °C, which implies a loss of L1 plus two equivalents of H2O (42.74% calculated). It is proposed that these water molecules were bound to the metal center due to the high temperature required to remove them and based on the bands observed in the IR spectrum (3300–3600 cm−1). Subsequently, a second loss at 518 °C is attributed to the loss of a second fraction of the ligand, and finally, a third loss occurs leaving a metallic residue. In the case of complex 3, the loss of a water molecule not coordinated to the metal center was observed to 58 °C, which is consistent with the IR spectrum. A second loss of 27% was observed and assigned to one ligand molecule (L2), and the remaining material existed as a residue of CoCNCl2. The TGA of 4, initially showed a loss between 270–352 °C, which may correspond to the loss of two water molecules coordinated to the metal center because high temperatures were required for these losses to occur. Similar to the copper complexes, in the analysis of chromium complexes 5–7, it was found that a temperature greater than 200 °C was necessary to lose an organic fragment. For all these complexes, the presence of both coordinating waters and watersmolecules of hydration was observed. An initial loss of H2O at 68 °C was observed for complex 5, and this loss correspond to watersmolecules of hydration. Then, the loss of an organic fragment at 330 °C was observed, and the remaining material formed a residue of CrCl3. For 6, only two mass losses are observed; an initial loss of 4H2O (watersmolecules of hydration) at 63 °C and a second loss of 71% was observed and assigned to the ligand molecule (L2), with the remained existing as a metallic residue. In complex 7, three main losses were observed. The first one was assigned to the elimination of 3H2O, which occurs in two steps based on the two maximum DTG peaks that occur; it is proposed that, of these three molecules, two are watersmolecules of hydration and the third is coordinated. Subsequently, the elimination of most of the organic matter occurs. Finally, the remaining organic fraction (which is proposed to be the methyl of the toluene fragment present in the ligand) is lost generating CrCl3 residue.

2.3. Biological Activity

The biological activities of the ligands and metal complexes were evaluated against all the strains in three replicates. Combinations of ligands and metal salts did not exhibit antimicrobial activity. Table 3 shows the antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic activities of the ligands and complexes as determined by the broth microdilution method (MIC; μgmL−1) and colorimetric method (CC50; μgmL−1).

Table 3.

Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of ligands and complexes (MIC, CC50; μg mL−1).

| Compound | S. aureus (MIC) | S. typhimurium (MIC) | E. coli (MIC) | C. tropicalis (MIC) | C. albicans (MIC) | C. parasilopsis (MIC) | Vero Cells (CC50 ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | >2000 | 1000 | >2000 | >2000 | >2000 | >2000 | >300 |

| L2 | >2000 | 1000 | >2000 | >2000 | >2000 | >2000 | >300 |

| 1 | >2000 | 2000 | >2000 | >2000 | >2000 | >2000 | >300 |

| 2 | 1000–2000 | 1000 | >2000 | 125 | 125 | 500 | 277.07 ± 1.86 |

| 3 | 250–500 | 1000 | 1000 | 31.25 | 125 | 125 | 68.76 ± 0.97 |

| 4 | 250–500 | 1000 | 2000 | 62.50 | 125 | 125 | 193.63 ± 6.51 |

| 5 | >2000 | 1000 | 2000 | 7.81 | 62.5 | 125 | >300 |

| 6 | >2000 | >2000 | >2000 | 7.81 | 62.5 | 62.5 | >300 |

| 7 | >2000 | >2000 | >2000 | 15.62 | 31.25 | 125 | 130.60 ± 3.57 |

| Ampicillin | 0.078–0.156 | ||||||

| Gentamicin | 2.50 | 0.625 | |||||

| Amphotericin B | 0.065 | 0.31 | 0.23 | ||||

| Itraconazole | 2.0 | 0.78 | 500 | 25.22 ± 3.51 |

The results are expressed in μg mL−1 and are the average of three independent experiments.

2.3.1. Antibacterial Activity

The antibacterial activities of the ligands and their complexes were studied against Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. The ligands, metal complexes and solvent control (DMSO) were screened separately for their antibacterial activities at concentrations of 2000–1.95 μg mL−1. Standards drugs (ampicillin, gentamicin, amphotericin B and itraconazole) were evaluated following the standars recommended by the CLSI. Bacterial species were more resistant to treatments with the new complexes. However, cobalt complexes 3 and 4 showed higher antibacterial activities with MIC values of 250 and 500 μg mL−1, respectively, for S. aureus (Table 3). In addition, these complexes have higher activities than free ligands L1, L2 and 1. This finding is likely related to the better lipophilicity of the complexes, cells and slowed the normal cellular processes of the microorganisms, resulting in increased antimicrobial activities or chelating effects [23,24,39,40]. We studied the antibacterial activities of twelve complexes derived from azole that contained cobalt and copper. In previous studies carried out in our research group, it was found that metal complexes containing copper and cobalt displayed better antibacterial effects against bacterial strains than those containing zinc [27].

Some studies have shown that azoles in complexes can inhibit the bacterial DNA [41]. For 3 and 4, similar activities were observed, and this result is probably due to the central ring separator (benzene (2), pyridine (3) and toluene (4)) as the presence of toluene increased the fluidity of Gram-negative cell membranes [27]. The pyridine in the ligand increases the noncovalent interactions with DNA through intermolecular associations as it can form hydrogen bonds, which in turn increases the antibacterial activity [18,42,43]. Previous studies have shown that complexes of Co(II) and Cr(III) containing ligands derived from azoles present activities against S. aureus with MIC values between 80 and 500 μg mL−1 for Co(II) complexes [27,29,44,45] and 17 μg mL−1 for Cr(III) complexes [37]. Although only zone of inhibition results were shown [20,21,22].

2.3.2. Antifungal Activity

The antifungal activities of the ligands and their complexes were studied against Candida tropicalis, C. albicans and C. parasilopsis. The compounds, amphotericin B, itraconazole and DMSO as the solvent control were screened separately for their antifungal activities at concentrations similar to those used in the antibacterial study. The free ligands showed higher value of MIC values than the complexes. The results of the antifungal activity tests suggested that all the synthesized metal complexes were effective in at least one of the strains used here, and they showed moderate MIC values compared to the reference drug amphotericin B. The cobalt complex showed MIC values between 31.25 and 250 μg mL−1, and those of the chromium complexes were 7.81–15.62 μg mL−1. This may be because azoles have higher antifungal activities [46,47]. Cobalt complexes have been studied as antimicrobial agents and have shown potential activities against different strains of fungi [27,48,49]. Nevertheless, there are few reports of studies against C. tropicalis using Co(II) complexes. Additionally, we concluded that these complexes do not show considerable activities as they show MIC values greater than 100 μg mL−1 [45,50,51,52,53]. The complexes of Co(II) (2–4) synthesized in this work showed better results. Moreover, 5–7 have higher antifungal activities than 2–4, and the lack of reports on chromium(III) complexes with antifungal activity against C. tropicalis is notable. Further studies are necessary to elucidate the antifungal mechanism of these chromium complexes. In addition, we tested itraconazole as a reference drug against all the Candida species included in this study. Itraconazole showed higher antifungal activity than the complexes against C. parasilopsis, which was resistant to antimycotic control.

On the other hand, mammalian cells exposed to 5 and 6 did not show signs of cytotoxic effects. The complexes had little effect on Vero cells with CC50 values above of 300 μg mL−1, indicating that they presented low toxicity. Notably, although amphotericin B is more active than the complexes, it is a polyene that exhibits broad-spectrum antimicrobial effects, and it is highly nephrotoxic and thus its use is limited in immunocompromised patients [54]. In addition, the use of itraconazole is restricted specifically due to the emergence of resistant strains of Candida.

2.4. Quantum-Chemical Calculations

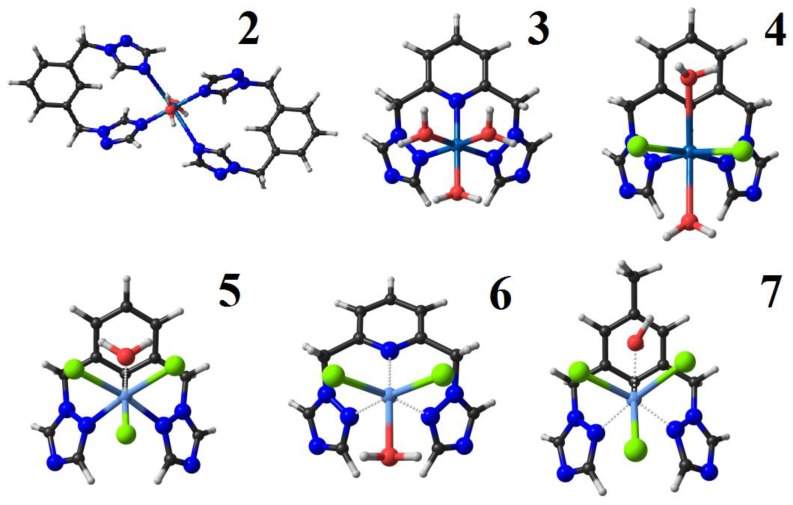

The relaxed geometries of the studied complexes (Figure 3) were obtained by density functional theory (DFT) calculations by using the ADF code [55] at the dispersion corrected BP86-D3 level of theory with all-electron TZ2P basis sets [56].

Figure 3.

Optimized geometries for complexes 2–7.

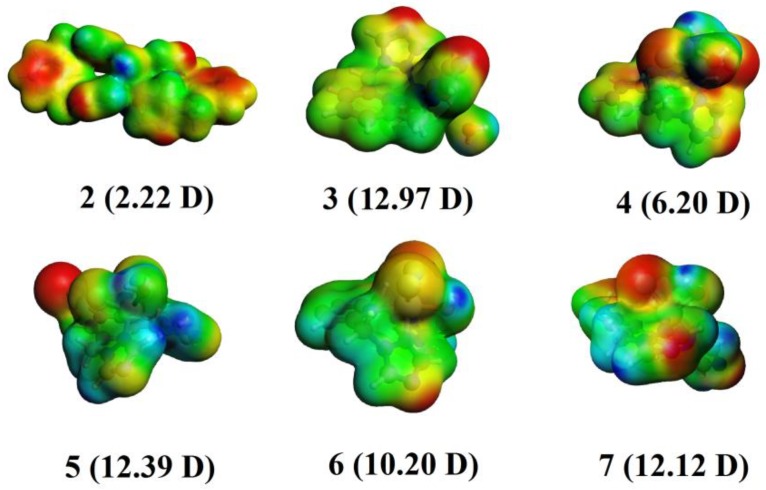

The evaluation of the relevant physicochemical properties to explain the observed differences in biological activity along the series exposed a key variation in the dipole moment, which has been early discussed as a useful parameter in drug-receptor interaction in the quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) framework [57]. The permanent molecular dipole moment (µ) is a key factor in long-range electrostatic forces, which are relevant for structure stabilization and drug-site interactions in biomolecules [58]. In this sense, the calculated molecular dipole moment at the DFT level shows values ranging from 2.22 to 22.97 Debye (D), and these values represent the charge distribution over the whole structure as observed from the molecular electrostatic potential energy surface (MEP) (Figure 4). Interestingly, the lowest MIC values corresponded to larger permanent dipole moments (µ values), and in the studies on C. tropicalis, complexes 2 and 3 showed MIC values of 125 µg mL−1 and 31.25 µg mL−1, respectively, which are in line with the difference in their dipole moments (2.22 to 12.97 D, Figure 2) from an almost centrosymmetric (2) to a noncentrosymmetric system (3), respectively. For 4, the MIC value in the same study was 62.50 µg mL−1, which appears to be connected to the decrease of in its dipole moment to 6.20 D relative to that of 3. The same trend can be deduced from other biological traits, indicating that the dipole moment can be a useful parameter to consider during the further development of biologically active complexes.

Figure 4.

Molecular electrostatic potential maps of the studied complexes denoting their permanent dipole moments in Debye (D). Blue regions indicate charge depletion, and red regions indicate charge accumulation.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Information

The starting salts CoCl2·6H2O and CrCl3·6H2O were used as received from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA). The compounds 1H-1,2,4-triazole, 3,5-bis(bromomethyl)toluene, 1,3-bis(bromomethyl)benzene, tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MI, USA) and were used as received.

1,3-Bis(1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmethyl)benzene (L1) [59] and 2,6-bis(1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmethyl)pyridine (L2) [60] were synthesized as described in the literature.

Elemental analysis (C, H and N) was performed with a Thermo Scientific™ FLASH 2000 CHNS/O Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded on a Thermo Nicolet NEXUS FTIR spectrophotometer using KBr pellets. Melting points were determined on a Mel-Temp® 1101D apparatus Electrothermal, Staffordshire, UK) in open capillary tubes and are uncorrected. Ultraviolet/visible (UV/vis) spectra were recorded on an Agilent Technologies Cary 100 spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in DMSO from 200 to 800 nm in a quartz cuvette with a path length of 1 cm. Molar conductivity measurements of the complexes were performed in a CON 700OAKTON instrument OAKTON Instruments, Vernon Hills, IL, USA) at 295 K (1 mM; dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)). Raman spectroscopy was performed in a HORIBA Yovin-Ivon spectrometer (HORIBA Scientific, Kyoto, Japan) using a laser with a wavelength of 786 nm. Thermogravimetric (TG) analyses of the complexes were conducted on a NETZSCH STA 409 PC/PG (NETZSCH, Selb, Bavaria, Germany) by evaluating 8–10 mg samples of the complexes in a nitrogen atmosphere. Samples were subjected to dynamic heating over a temperature range of 30–700 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. TG curves were analyzed to obtain the percent mass losses as a function of temperature. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker AscendTM-400 spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) at 295 K. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm relative to SiMe4 (1H) as an internal standard. 1H and 13C-NMR chemical shifts (δ) are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to TMS, with the residual solvent peak used as an internal reference; CDCl3 (1H-NMRδ: 7.26 and 13C-NMRδ: 77.2) and DMSO-d6 (1H-NMRδ: 2.50 and 13C-NMRδ: 39.5). High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data of ligand 1 was obtained on an Agilent Technologies Q-TOF 6520 spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) via electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive ion modein chloroform.

3.2. Synthesis of 3,5-Bis(1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmethyl)toluene (1)

In a Schlenk tube equipped with a reflux condenser, 1H-1,2,4-triazole (1117 mg, 16.18 mmol), potassium hydroxide (1286 mg; 22.92 mmol), tetrabutylammonium bromide (405.7 mg; 1.26 mmol), and water (8 mL) were stirred at room temperature (r.t.) for 20 min. Then, 1,3-bis(bromomethyl)toluene (2279 mg; 8.20 mmol) and toluene (50 mL) were added, and the mixture was heated for 48 h at 85 °C. The resulting mixture was treated with water and the organic layer was separated and dried with magnesium sulfate. The solution was concentrated to dryness to give a yellow oil, which was purified by silica gel column chromatography (type 60) eluting with DCM:methanol 9:1 to give a pure compound (white solid). Yield 1167 g (67%). M.p.: 135–136 °C. FTIR (KBr, cm−1): 3090, 2924, 1609, 1504, 1466, 1431, 1385, 1346, 1261, 1207, 1134, 1018, 980 953, 918, 891, 745, 725, 567, 366, 351. Raman (cm−1): 1604, 1496, 1434, 1370, 1286, 1128, 1013, 760, 533, 282.

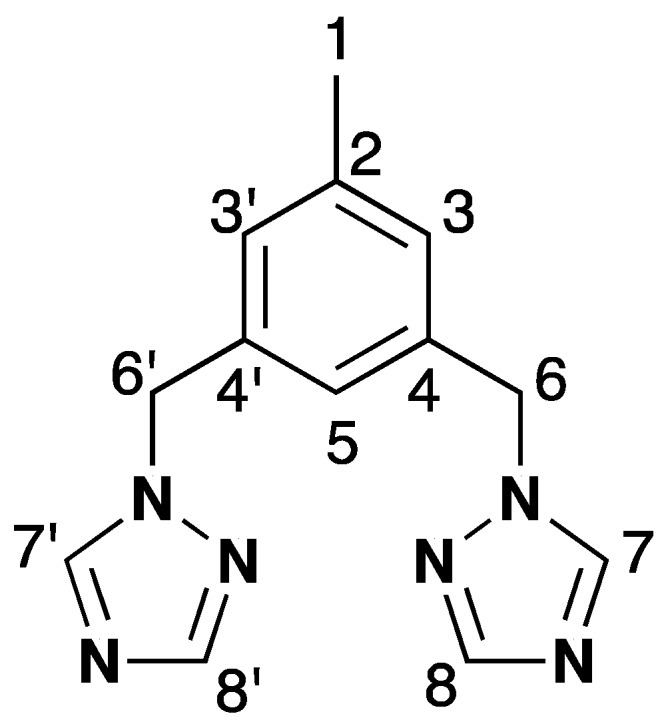

Atom numbering for ligand 1 is as follows (Figure 5):

Figure 5.

Atom numbering for signal assignment of the NMR for 1.

1H-NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.63 (s, 2H, 7, 7’), 7,97 (s, 2H, 8, 8’), 7,02 (s, 2H, 3, 3’), 7,00 (s, 1H, 5), 5,35 (s, 4H, 6, 6’), 2,25 (s, 3H, 1). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6, 101 MHz) δ 151,65 (C8, C8’), 144,16 (C7, C7’), 138,31 (C2), 136,62 (C4, C4’), 127,97 (C3, C3’), 124,38 (C5), 51,81 (C6, C6’), 20,77 (C1).

MS-ESI (m/z, ES+) calcd. For [M + H]+: 253; found: 253. UV/Vis (bands λmax, nm (ε, L mol−1 cm−1): 267 (297). Anal. Calcd. for C13H14N6: C 61.34; H 5.51; N 33.03. Found: C 60.92; H 5.58; N 33.02%.

3.3. Synthesis of the Complexes

3.3.1. Synthesis of [Co{1,3-bis((1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmethyl)benzene-N,N}(H2O)2]Cl2 (2)

L1 (0.991 mmol; 238.6 mg) was dissolved in acetone (6 mL), and CoCl2·6H2O (1.02 mmol; 241.8 mg) in acetone (8 mL) was added to this mixture. The resulting solution was stirred for 2 h at room temperature (r.t.). This mixture was centrifuged at 400 rpm for 8 min, washing with acetone, dichloromethane and ethyl ether and removing the liquid phase between each wash. Then, the solvent was evaporated to dryness to give a violet solid. Yield: 293.4 mg (90.6%). M.p.: > 400 °C. FTIR (KBr, cm−1): 3453, 3119, 1520, 1441, 1375, 1350, 1279, 1207, 1165, 1128, 1016, 988, 889, 735, 675, 650. Raman (cm−1): 1607, 1520, 1435, 1273, 1237, 1171, 1136, 1008, 753, 647, 501, 435. UV/Vis bands λmax, nm (ε, L mol−1 cm−1): 262 (784). ΛM = 52.9 µS. Anal. Calcd. for C24H28Cl2CoN12O2: C 44.55; H 4.33; N 25.99. Found: C 45.00; H 4.21; N 25.96%.

3.3.2. Synthesis of [Co{2,6-bis((1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmetil)pyridine-N,N,N}(H2O)3] Cl2·H2O (3)

(L2) (1.0 mmol; 241.2 mg) was dissolved in acetone (9 mL), and CoCl2·6H2O (1.02 mmol; 241.8 mg) in acetone (7 mL) was added to this mixture. The resulting solution was stirred for 5 h at r.t. This mixture was centrifuged at 400 rpm for 8 min, washing with acetone, dichloromethane and ethyl ether and removing the liquid phase between each wash. Then, the solvent was evaporated to give a light-blue solid. Yield: 299 mg (67.4%). M.p.: > 400 °C. FTIR (KBr, cm−1): 3402, 3119, 1603, 1576, 1524, 1460, 1435, 1277, 1207, 1125, 1013, 986, 883, 766, 746, 677, 650. Raman (cm−1): 1430, 1348, 1125, 1014, 994, 593, 522, 342, 274. UV/Vis bands λmax, nm (ε, L mol−1 cm−1): 264 (3317). ΛM = 50.5 µS. Anal. Calcd. for C11H19Cl2CoN7O4: C 29.78; H 4.29; N 22.11. Found: C 29.69; H 3.94; N 22.07%.

3.3.3. Synthesis of [Co{3,5-bis((1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmethy)toluene-N,N}(H2O)2Cl2] (4)

1 (1.12 mmol; 241.8 mg) was dissolved in acetone (7 mL), and CoCl2·6H2O (1.02 mmol; 241.8 mg) in acetone (8 mL) was added to this mixture. The resulting solution was stirred for 3 h at r.t. This mixture was centrifuged at 400 rpm for 8 min, washing with acetone, dichloromethane and ethyl ether and removing the liquid phase between each wash. Then, the solvent was evaporated to give a blue solid. Yield: 296.3 mg (69.4%). M.p.: > 400 °C. FTIR (KBr, cm−1): 3111, 1609, 1522, 1437, 1352, 1279, 1206, 1128, 1016, 988, 881, 758, 675, 652. Raman (cm−1): 1605, 1520, 1464, 1434, 1358, 1282, 1127, 996, 759, 522, 303. UV/Vis bands λmax, nm (ε, L mol−1 cm−1): 268 (556). ΛM = 43.3 µS. Anal. Calcd. for C13H18Cl2CoN6O2: C 37.12; H 4.28; N 19.99. Found: C 37.11; H 4.28; N 20.06%.

3.3.4. Synthesis of [Cr {1,3-Bis(1,2,4-triazol-1ylmethyl)benzene-N,N}(H2O)Cl3]·2H2O (5)

L1 (1.01 mmol; 241.9 mg) was dissolved in acetone (6 mL), and CrCl3·6H2O (1.0 mmol; 265.8 mg) in acetone (12 mL) was added to this mixture. The resulting solution was stirred for 2 h at r.t. This mixture was centrifuged at 400 rpm for 8 min, washing with acetone, dichloromethane and ethyl ether and removing the liquid phase between each wash. Then, the solvent was evaporated to give a light-green solid. Yield: 360.3 mg (79.8%). M.p.: > 400 °C. FTIR (KBr, cm−1): 3429, 1620, 1530, 1437, 1348, 1283, 1209, 1123, 1005, 889, 735, 673, 648. Raman (cm−1): 1609, 1528, 1430, 1362, 1278, 1237, 1172, 1123, 1000, 336, 268. UV/Vis bands λmax, nm (ε, L mol−1 cm−1): 260 (3672). ΛM = 24.4 µS. Anal. Calcd. for C12H18Cl3CrN6O3: C 31.81; H 3.98; N 18.55. Found: C 31.39; H 4.24; N 18.39%.

3.3.5. Synthesis of [Cr{2,6-bis((1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmethyl)pyridine-N,N,N}(H2O)Cl2]Cl·5H2O (6)

L2 (1.0 mmol; 241.7 mg) was dissolved in acetone (8 mL), and CrCl3·6H2O (1.01 mmol; 296.6 mg) in acetone (14 mL) was added to this mixture. The resulting solution was stirred for 2 h at r.t. This mixture was centrifuged at 400 rpm for 8 min, washing with acetone, dichloromethane and ethyl ether and removing the liquid phase between each wash. Then, the solvent was evaporated to give a light-green solid. Yield: 320 mg (63%). M.p.: > 400 °C. FTIR (KBr, cm−1): 3379, 3130, 1634, 1599, 1533, 1460, 1429, 1282, 1211, 1125, 1005, 887, 768, 673, 654. Raman (cm−1): 1425, 1366, 1121, 1084, 998, 587, 518, 338, 266. UV/Vis bands λmax, nm (ε, L mol−1 cm−1): 263 (7081). ΛM = 30.3 µS. Anal. Calcd. for C11H23Cl3CrN7O6: C 26.00; H 4.14; N 19.30. Found: C 26.05; H 4.04; N 19.19%.

3.3.6. Synthesis of [Cr{3,5-Bis(1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmethyl)toluene-N,N}(H2O)Cl3] 2H2O (7)

1 (1.16 mmol; 293.8 mg) was dissolved in acetone (7 mL), and CrCl3·6H2O (1.02 mmol; 273.3 mg) in acetone (15 mL) was added to this mixture. The resulting solution was stirred for 2 h at r.t. This mixture was centrifuged at 400 rpm for 8 min, washing with acetone, dichloromethane and ethyl ether and removing the liquid phase between each wash. Then, the solvent was evaporated to give a light-green solid. Yield: 204.3 mg (43%). M.p.: > 400 °C. FTIR (KBr, cm−1): 3375, 3130, 1612, 1531, 1439, 1348, 1285, 1209, 1125, 1005, 887, 756, 671, 650. Raman (532 nm, cm−1): 1604, 1530, 1472, 1434, 1355, 1283, 1121, 997, 757, 518, 260. UV/Vis bands λmax, nm (ε, L mol−1 cm−1): 259 (2141). ΛM = 27.4 µS. Anal. Calcd. for C13H20Cl3CrN6O3: C 33.42; H 4.29; N 17.99. Found: C 33.47; H 4.20; N 17.89%.

3.4. Biological Studies

3.4.1. Microorganisms and Mammalian Cells

Candida albicans (ATCC, 10231), C. tropicalis (ATCC, 750), and C. parasilopsis (ATCC, 22019) were grown on Sabouraud Dextroseagar (OXOID Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) at 30 °C; Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC, 11632), Escherichia coli (ATCC, 10536) and Salmonella typhimurium (ATCC, 14028) were grown on nutrient agar (OXOID Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) at 37 °C. African green monkey kidney epithelial cells “Cercopithecusactiops” (Vero, CCL-81), donated by Dr. José Arteaga of the Universidad Industrial de Santander, were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 5% inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBSi, Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity.

3.4.2. Evaluation of the Antimicrobial Activity

Experiments were performed using the broth microdilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M27A-3 and M07-A10 protocols. Dilutions of each compound under study were performed in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with (3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid) (MOPS, Sigma-Aldrich) and Mueller Hinton broth (OXOID, Basingtoke, Hampshire, England) to concentrations of 2000–1.95 μg mL−1 in a 96-well plate. Untreated controls were similarly evaluated (itraconazole and amphotericin B on fungus and gentamicin and ampicillin on bacteria were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MI, USA). An inoculum containing between 2500 and 5000 cells/mL of each strain of Candida and 105 cells/mL of bacteria was added (100 µL) to each well of the plate, and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. The MIC was visually determined as the lowest concentration capable of inhibiting the growth of the fungus. Subsequently, the minimum fungicidal and bactericidal concentrations were determined after broth microdilution tests by sub-culturing a sample from the negative wells on the surface of Sabouraud dextroseand Mueller Hinton agar to determine the number of surviving cells after 24 h of incubation, and this value is expressed as CFU mL−1. The fungicidal and bactericidal endpoints were established as the lowest concentration that kills 98–99% of the final inoculum.

3.4.3. Cytotoxicity Test on Mammalian Cells

Vero cells (3 × 105 cells/mL) were added to 96-well microplates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2until a monolayer formed. The cells were then treated with serial dilutions (1:3) of the compounds and reference drugs in concentrations of 300 μg mL−1 to 11.1 μg mL−1 for 72 h. The cell viability was evaluated using MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, Sigma-Aldrich) tetrazolium salt at a concentration of 5 mg/mL. A spectrophotometric reading was performed on a microplate reader for measuring absorbance/ELISA (BIO-RAD) using a wavelength of 580 nm. All assays were performed in triplicate in independent experiments. The cytotoxic concentrations 50 and 90 (CC50 and CC90) were determined by sigmoidal regression using the statistical program XLFit5.

4. Conclusions

In summary, three ligands derived from triazole (one new) were synthesized and fully characterized. Additionally, six new complexes of Co(II) and Cr(III) were obtained, and they were characterized by spectroscopic, elemental and thermogravimetric techniques. The analyses and spectral data showed that complexes 3–7 had 1:1 (M:L) stoichiometries and octahedral geometries, while 2 had a 1:2 (M:L), and this was supported by DFT calculations. In vitro assays showed that the chromium complexes are more active against fungi than against bacterial strains, and they exhibited high anti-C. tropicalis activity. Interestingly, the observed activities appear to be related to the permanent dipole moment of each complex. These results can facilitate the design of new antibacterial and antifungal compounds. Studies to further elucidate their structure-activity relationship are in progress.

Acknowledgments

E.N. thank the financial support by the Universidad de Ibagué (project 18-541-INT).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online.

Author Contributions

S.M.L. and M.V.R. performed the in vitro experiments. R.A.M. synthesized and characterized the ligands and complexes. A.M.-C. and E.N. carried out the DFT computational studies. All authors contributed with crucial discussions and constructive reviews. J.J.H. is the corresponding author.

Funding

The authors express their thanks to the Universidad de los Andes for the financial support from the Interfaculty project and the Faculty of Sciences. We thank the reviewers and editor for their useful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of all the compounds are available from the authors.

References

- 1.O’Neill J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. [(accessed on 7 August 2018)];2016 Available online: https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf.

- 2.Crump J.A., Ramadhani H.O., Morrissey A.B., Saganda W., Mwako M.S., Yang L.Y., Chow S.C., Morpeth S.C., Reyburn H., Njau B.N., et al. Invasive bacterial and fungal infections among hospitalized HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected adults and adolescents in northern Tanzania. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:341–348. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson M.D., Warnock D.W. Fungal Infection: Diagnosis and Management. John Wiley & Sons; West Sussex, UK: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Browning D.F., Busby S.J. Local and Global Regulation of Transcription Initiation in Bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;14:638–650. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kontoyiannis D.P., Vaziri I., Hanna H.A., Boktour M., Thornby J., Hachem R., Bodey G.P., Raad I.I. Risk Factors for Candida Tropicalis Fungemia in Patients with Cancer. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001;33:1676–1681. doi: 10.1086/323812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kothavade R.J., Kura M.M., Valand A.G., Panthaki M.H. Candida Tropicalis: Its Prevalence, Pathogenicity and Increasing Resistance to Fluconazole. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010;59:873–880. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.013227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva S., Negri M., Henriques M., Oliveira R., Williams D.W., Azeredo J. Candida Glabrata, Candida Parapsilosis and Candida Tropicalis: Biology, Epidemiology, Pathogenicity and Antifungal Resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012;36:288–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bihan C.L., Zahar J.R., Timsit J.F. Staphylococcus aureus Transmission in the Intensive Care Unit: The Potential Role of the Healthcare Worker Carriage. Ann. Infect. 2017;1:1–5. doi: 10.21037/aoi.2017.08.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Price J.R., Cole K., Bexley A., Kostiou V., Eyre D.W., Golubchik T., Wilson D.J., Crook D.W., Walker A.S., Peto T.E. Transmission of Staphylococcus aureus between Health-Care Workers, the Environment, and Patients in an Intensive Care Unit: A Longitudinal Cohort Study Based on Whole-Genome Sequencing. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017;17:207–214. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30413-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Recker M., Laabei M., Toleman M.S., Reuter S., Saunderson R.B., Blane B., Török M.E., Ouadi K., Stevens E., Yokoyama M., et al. Clonal Differences in Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia-Associated Mortality. Nat. Microbiol. 2017;2:1381–1388. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierce R., Lessler J., Popoola V.O., Milstone A.M. Meticillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Acquisition Risk in an Endemic Neonatal Intensive Care Unit with an Active Surveillance Culture and Decolonization Programme. J. Hosp. Infect. 2017;95:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kathiravan M.K., Salake A.B., Chothe A.S., Dudhe P.B., Watode R.P., Mukta M.S., Gadhwe S. The Biology and Chemistry of Antifungal Agents: A Review. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012;20:5678–5698. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bendaha H., Yu L., Touzani R., Souane R., Giaever G., Nislow C., Boone C., El Kadiri S., Brown G.W., Bellaoui M. New azole antifungal agents with novel modes of action: Synthesis and biological studies of new tridentate ligands based on pyrazole and triazole. Eur. J. Med Chem. 2011;46:4117–4124. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shrinivas D.J., Sheshagiri R.D., Uttam A.M., Tejraj A., Venkatrao H.K., Andanappa K.G. Enoyl ACP Reductase as Effective Target for the Synthesized Novel Antitubercular Drugs: A-State-of-the-Art. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2014;14:678–693. doi: 10.2174/1389557514666140820112524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh K., Singh D.P., Barwa M.S., Tyagi P., Mirza Y. Antibacterial Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) Complexes of Schiff bases Derived from Fluorobenzaldehyde and Triazoles. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2006;21:557–562. doi: 10.1080/14756360600642131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holla B.S., Poojary K.N., Rao B.S., Shivananda M.K. New bis-aminomercaptotriazoles and bis-triazolothiadiazoles as possible anticancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2002;37:511–517. doi: 10.1016/S0223-5234(02)01358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Gammal O.A., Bekheit M.M., Tahoon M. Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Activity of 2-Acetylpyridine-α-Naphthoxyacetylhydrazone Its Metal Complexes. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015;135:597–607. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2014.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurtado J., Ibarra L., Yepes D., García-Huertas P., Macías M.A., Triana-Chavez O., Nagles E., Suescun L., Muñoz-Castro A. Synthesis, crystal structure, catalytic and anti-Trypanosomacruzi activity of a new chromium(III) complex containing bis(3,5-dimethylpyrazol-1-yl)methane. J. Mol. Struct. 2017;1146:365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2017.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alaghaz A.-N.M.A., Ammar R.A. New Dimeric Cyclodiphosph(V)Azane Complexes of Cr(III), Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II), and Zn(II): Preparation, Characterization and Biological Activity Studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:1314–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarafder M.T.H., Ali M.A., Wee D.J., Azahari K., Silong S., Crouse K.A. Complexes of a Tridentate ONS Schiff Base. Synthesis and Biological Properties. Transit. Met. Chem. 2000;25:456–460. doi: 10.1023/A:1007062409973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohamed G.G., Zayed M.A., Abdallah S.M. Metal Complexes of a Novel Schiff Base Derived from Sulphametrole and Varelaldehyde. Synthesis, Spectral, Thermal Characterization and Biological Activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2010;979:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2010.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emara A.A.A. Structural, Spectral and Biological Studies of Binuclear Tetradentate Metal Complexes of N3O Schiff Base Ligand Synthesized from 4,6-Diacetylresorcinol and Diethylenetriamine. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2010;77:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2010.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kljun J., Scott A.J., LanišnikRižner T., Keiser J., Turel I. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Organoruthenium Complexes with Azole Antifungal Agents. First Crystal Structure of a Tioconazole Metal Complex. Organometallics. 2014;33:1594–1601. doi: 10.1021/om401096y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bello-Vieda N.J., Pastrana H.F., Garavito M.F., Ávila A.G., Celis A.M., Muñoz-Castro A., Restrepo S., Hurtado J.J. Antibacterial Activities of Azole Complexes Combined with Silver Nanoparticles. Molecules. 2018;23:361. doi: 10.3390/molecules23020361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pahontu E., Fala V., Gulea A., Poirier D., Tapcov V., Rosu T. Synthesis and Characterization of Some New Cu(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) Complexes with Salicylidene Thiosemicarbazones: Antibacterial, Antifungal and in Vitro Antileukemia Activity. Molecules. 2013;18:8812–8836. doi: 10.3390/molecules18088812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yousef T.A., Abu El-Reash G.M., Al-Jahdali M., El-Rakhawy E.-B.R. Synthesis, spectral characterization and biological evaluation of Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II), Zn(II) and Cd(II) complexes with thiosemicarbazone ending by pyrazole and pyridyl rings. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014;129:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2014.02.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castillo K.F., Bello-Vieda N.J., Nuñez-Dallos N.G., Pastrana H.F., Celis A.M., Restrepo S., Hurtado J.J., Ávila A.G. Metal complex derivatives of azole: A study on their synthesis, characterization, and antibacterial and antifungal activities. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2016;27:2334–2347. doi: 10.5935/0103-5053.20160130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sumrra S.H., Suleman A., Chohan Z.H., Zafar M.N., Raza M.A., Iqbal T. Triazole Metal Based Complexes as Antibacterial/Antifungal Agents. Russ. J. General Chem. 2017;87:1281–1287. doi: 10.1134/S107036321706024X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh K., Kumar Y., Puri P., Kumar M., Sharma C. Cobalt, Nickel, Copper and Zinc Complexes with 1,3-Diphenyl-1H-Pyrazole-4-Carboxaldehyde Schiff Bases: Antimicrobial, Spectroscopic, Thermal and Fluorescence Studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;52:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sundaraganesan N., Kavitha E., Sebastian S., Cornard J.P., Martel M. Experimental FTIR, FT-IR (gas phase), FT-Raman and NMR spectra, hyperpolarizability studies and DFT calculations of 3,5-dimethylpyrazole. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2009;74:788–797. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geary W.J. The Use of Conductivity Measurements in Organic Solvents for the Characterization of Coordination Compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1971;7:81–122. doi: 10.1016/S0010-8545(00)80009-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katritzky A., Ramsden C., Joule J., Zhdankin V. In: Handbook of Heterocyclic Chemistry. 3rd ed. Katritzky A.R., editor. Elsevier; Amsterdam, NY, USA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandoval-Rojas A.P., Ibarra L., Cortés M.T., Macías M.A., Suescun L., Hurtado J.J. Synthesis and characterization of copper(II) complexes containing acetate and N,N-donor ligands, and their electrochemical behavior in dopamine detection. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017;805:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2017.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larkin P.J. Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy: Principles and Spectral Interpretation. Elsevier; Amsterdam, NY, USA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Socrates G. Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies: Tables and Charts. 3rd ed. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Billes F., Ziegler I., Mikosch H. Vibrational Spectroscopic Study of Sodium-1,2,4-Triazole, an Important Intermediate Compound in the Synthesis of Several Active Substances. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2016;153:349–362. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Billes F., Endredi H., Keresztury G. Vibrational Spectroscopy of Triazoles and Tetrazole. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM. 2000;530:183–200. doi: 10.1016/S0166-1280(00)00340-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cotton F.A., Wilkinson G. Advanced Inorganic Chemistry. 6th ed. John Wiley & Sons; London, UK: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heerding D.A., Chan G., DeWolf W.E., Fosberry A.P., Janson C.A., Jaworski D.D., McManus E., Miller W.H., Moore T.D., Payne D.J., et al. 1,4-Disubstituted imidazoles are potential antibacterial agents functioning as inhibitors of enoyl acyl carrier protein reductase (FabI) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:2061–2065. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(01)00404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kabbani A.T., Hammud H.H., Ghannoum A.M. Preparation and antibacterial activity of copper and cobalt complexes of 4-chloro-3-nitrobenzoate with a nitrogen donor ligand. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 2007;55:446–450. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collin F., Karkare S., Maxwell A. Exploiting bacterial DNA gyrase as a drug target: Current state and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011;92:479–497. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3557-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McIlwain H. Pyridine-3-Sulphonic Acid and Its Amide as Inhibitors of Bacterial Growth. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1940;21:136. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider D., Parker C.D. Effect of Pyridines on Phenotypic Properties of Bordetella Pertussis. Infect. Immun. 1982;38:548–553. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.2.548-553.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bagihalli G.B., Avaji P.G., Patil S.A., Badami P.S. Synthesis, Spectral Characterization, in Vitro Antibacterial, Antifungal and Cytotoxic Activities of Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) Complexes with 1,2,4-Triazole Schiff Bases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008;43:2639–2649. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poyraz M., Sari M., Demirci F., Kosar M., Demirayak S., Büyükgüngör O. Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Biological Activity of 1-(1H-Benzoimidazol-2-Yl)-EthanoneThiosemicarbazone and Its Cobalt Complex. Polyhedron. 2008;27:2091–2096. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2008.03.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van den Bossche H., Willemsens G., Cools W., Marichal P., Lauwers W. Hypothesis on the molecular basis of the antifungal activity of N-substituted imidazoles and triazoles. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1983;11:665–667. doi: 10.1042/bst0110665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herbrecht R. Voriconazole: Therapeutic review of a new azole antifungal. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2004;2:485–497. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chohan Z.H., Hanif M. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Properties of Triazole Derived Compounds and Their Transition Metal Complexes. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2010;25:737–749. doi: 10.3109/14756360903389906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chohan Z.H., Hanif M. Antibacterial and Antifungal Metal Based Triazole Schiff Bases. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013;28:944–953. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2012.696246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carcelli M., Mazza P., Pelizzi C., Zani F. Antimicrobial and Genotoxic Activity of 2,6-Diacetylpyridine Bis(Acylhydrazones) and Their Complexes with Some First Transition Series Metal Ions. X-Ray Crystal Structure of a Dinuclear Copper(II) Complex. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1995;57:43–62. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(94)00004-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shreaz S., Sheikh R.A., Bhatia R., Neelofar K., Imran S., Hashmi A.A., Manzoor N., Basir S.F., Khan L.A. Antifungal Activity of α-Methyl Trans Cinnamaldehyde, Its Ligand and Metal Complexes: Promising Growth and Ergosterol Inhibitors. BioMetals. 2011;24:923–933. doi: 10.1007/s10534-011-9447-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bellú S., Hure E., Trapé M., Trossero C., Molina G., Drogo C., Williams P.A.M., Atria A.M., Muñoz Acevedo J.C., Zacchino S., et al. Synthesis, Structure and Antifungal Properties of Co(II)–sulfathiazolate Complexes. Polyhedron. 2005;24:501–509. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2004.12.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodríguez-Argüelles M.C., Cao R., García-Deibe A.M., Pelizzi C., Sanmartín-Matalobos J., Zani F. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity of Metal(II) Complexes of Acylhydrazones of 3-Isatin and 3-(N-Methyl)Isatin. Polyhedron. 2009;28:2187–2195. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2008.12.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pea F., Lewis R.E. Overview of antifungal dosing in invasive candidiasis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018;73:i33–i43. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.TeVelde G., Bickelhaupt F.M., Baerends E.J., Fonseca Guerra C., van Gisbergen S.J.A., Snijders J.G., Ziegler T. Chemistry with ADF. J. Comput. Chem. 2001;22:931–967. doi: 10.1002/jcc.1056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grimme S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006;27:1787–1799. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lien E.J., Guo Z.R., Li R.L., Su C.T. Use of Dipole Moment as a Parameter in Drug-Receptor Interaction and Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship Studies. J. Pharm. Sci. 1982;71:641–655. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600710611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vistoli G., Pedretti A. Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry II. Elsevier; New York, NY, USA: 2007. Molecular Fields to Assess Recognition Forces and Property Spaces; pp. 577–602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Díez-Barra E., Guerra J., López-Solera I., Merino S., Rodríguez-López J., Sánchez-Verdú P., Tejeda J. Novel Chiral and Achiral NCN Pincer Complexes Based on 1,3-Bis(1H-1,2,4-Triazol-1-Ylmethyl)Benzene. Organometallics. 2003;22:541–547. doi: 10.1021/om020764i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim E.Y., Song Y.J., Koo H.G., Lee J.H., Park H.M., Kim C., Kwon T.-H., Huh S., Kim S.-J., Kim Y. 1-D, 2-D and 3-D Coordination Polymers Assembled from PolynuclearCoII Units Based on the Isophthalate(-2) Ligand. Polyhedron. 2010;29:3335–3341. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2010.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.