Abstract

Background

Patients who have had an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) are at increased risk of recurrent cardiovascular events; however, paradoxically, high‐risk patients who may derive the greatest benefit from guideline‐recommended therapies are often undertreated. The aim of our study was to examine the management, clinical outcomes, and temporal trends of patients after ACS stratified by the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score for secondary prevention, a recently validated clinical tool that incorporates 9 clinical risk factors.

Methods and Results

Included were patients with ACS enrolled in the biennial Acute Coronary Syndrome Israeli Surveys (ACSIS) between 2008 and 2016. Patients were stratified by the TIMI risk score for secondary prevention to low (score 0–1), intermediate (2), or high (≥3) risk. Clinical outcomes included 30‐day major adverse cardiac events (death, myocardial infarction, stroke, unstable angina, stent thrombosis, urgent revascularization) and 1‐year mortality. Of 6827 ACS patients enrolled, 35% were low risk, 27% were intermediate risk, and 38% were high risk. Compared with the other risk groups, high‐risk patients were older, were more commonly female, and had more renal dysfunction and heart failure (P<0.001 for each). High‐risk patients were treated less commonly with guideline‐recommended therapies during hospitalization (percutaneous coronary intervention) and at discharge (statins, dual‐antiplatelet therapy, cardiac rehabilitation). Overall, high‐risk patients had higher rates of 30‐day major adverse cardiac events (7.2% low, 8.2% intermediate, and 15.1% high risk; P<0.001) and 1‐year mortality (1.9%, 4.6%, and 15.8%, respectively; P<0.001). Over the past decade, utilization of guideline‐recommended therapies has increased among all risk groups; however, the rate of 30‐day major adverse cardiac events has significantly decreased among patients at high risk but not among patients at low and intermediate risk. Similarly, the 1‐year mortality rate has decreased numerically only among high‐risk patients.

Conclusions

Despite an improvement in the management of high‐risk ACS patients, they are still undertreated with guideline‐recommended therapies. Nevertheless, the outcome of high‐risk patients after ACS has significantly improved in the past decade, thus they should not be denied these therapies.

Keywords: acute coronary syndrome, cardiovascular outcomes, guideline‐recommended therapies, risk score, secondary prevention

Subject Categories: Cardiovascular Disease, Quality and Outcomes, Secondary Prevention

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Despite advances in invasive and pharmacological treatment of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), high‐risk ACS patients (as determined by the TIMI risk score for secondary prevention) are still undertreated with guideline‐recommended therapies.

Nevertheless, clinical outcomes of high‐risk ACS patients have improved significantly over the past decade, whereas outcomes of low‐ and intermediate‐risk patients appear to be unchanged.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

High‐risk ACS patients (eg, elderly patients and those with renal dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, or peripheral arterial disease) should not be denied guideline‐recommended therapies.

Patient stratification after ACS will help identify patients who may benefit the most from guideline‐recommended therapies.

Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS), the acute manifestation of ischemic heart disease, remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Although percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and pharmacological treatment have improved significantly in the past decade, patients admitted with an ACS still have significant residual risk for recurrent cardiovascular events.1, 2

Optimal medical therapy with antiplatelet drugs, statins, and other guideline‐recommended therapies3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 are of paramount importance in preventing recurrent cardiovascular events in patients after an ACS.11 In addition, other strategies for risk‐factor modification and lifestyle changes such as diet, cardiac rehabilitation, exercise, and smoking cessation reduce the rate of recurrent cardiovascular events.12, 13, 14 Despite these treatment strategies, not all ACS patients receive optimal treatment. Paradoxically, patients who are at increased risk (eg, elderly, female, those with renal dysfunction and other comorbidities) are often undertreated.15

The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score for secondary prevention (TRS 2oP) is a validated tool to stratify patients after an ACS, based on their clinical characteristics and according to their risk for recurrent cardiovascular events.16 We aimed to examine the management, clinical outcomes, and temporal trends over the past decade of patients with ACS stratified by the TRS 2oP, and to identify risk groups that might particularly benefit from optimal therapy.

Methods

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure.

The ACSIS (Acute Coronary Syndrome Israel Survey) is a biennial prospective national registry of all patients with ACS hospitalized in 25 coronary care units and cardiology departments in all general hospitals in Israel over a 2‐month period (March to April).17, 18 Clinical, historical, and demographic data were recorded on prespecified forms for all admitted patients diagnosed with ACS. Admission and discharge diagnoses were recorded by the attending physicians based on electrocardiographic, clinical, and biochemical criteria. Patient management was at the discretion of the attending physicians. All patients signed an informed consent form for participating in the ACSIS registry at each medical center, and each institution received the approval of its institutional review board.

All patients enrolled in the ACSIS registry between 2008 and 2016 were included in the present study. Although the ACSIS registry has been available since 2000, the time period was chosen to describe a contemporary cohort of patients with ACS in the past decade, during which PCI has become the mainstay of treatment, and to examine relevant temporal trends.

Patients were stratified according to the TRS 2oP for recurrent cardiovascular events after an ACS.16 This score incorporates 9 simple clinical characteristics: age ≥75 years, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, current smoking, peripheral arterial disease, prior stroke, prior coronary artery bypass grafting surgery, chronic heart failure, and estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min. Patients were stratified as low risk (0–1 characteristics), intermediate risk (2 characteristics), or high risk (≥3 characteristics).

Clinical outcomes included 30‐day major adverse cardiac events (MACE; death, myocardial infarction [MI], stroke, unstable angina, stent thrombosis, and urgent revascularization) and 1‐year mortality. Data of 30‐day MACE were ascertained by hospital chart review, telephone contact, and clinical follow‐up data. Mortality data at 30 days were determined for all patients from hospital charts and by matching identification numbers of patients with the Israeli National Population Register. One‐year mortality data were ascertained through the use of the Israeli National Population Registry.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics, management, and treatment were stratified by the 3 TRS 2oP groups (Tables 1, 2–3). Differences in continuous parameters were tested using 1‐way ANOVA for normally distributed values or the Kruskal–Wallis test for nonnormally distributed values. Categorical parameters were compared using the χ2 test. Temporal trends in treatment and outcomes stratified by the 3 TRS 2oP groups (Tables 4 and 5) were calculated using the χ2 test for trend. Clinical outcomes were examined using Cox regression analysis (1‐year mortality) or logistic regression models (30‐day MACE).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| TIMI Risk Score for Secondary Prevention | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Risk (n=2421) | Intermediate Risk (n=1788) | High Risk (n=2618) | |

| Age, y, mean±SD | 56.9±10.6 | 62.9±11.5 | 70.9±12.1 |

| Sex (male) | 2082 (86.0) | 1390 (77.7) | 1881 (71.8) |

| Dyslipidemia | 1495 (62.0) | 1365 (76.6) | 2230 (85.3) |

| Hypertension | 582 (24.0) | 1339 (74.9) | 2436 (93.0) |

| Current smoking | 931 (38.5) | 799 (44.7) | 936 (35.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 149 (6.2) | 680 (38.0) | 1821 (69.6) |

| Family history of CAD | 848 (37.5) | 459 (28.9) | 512 (23.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.78 (11.0) | 29.17 (15.4) | 28.98 (16.0) |

| Prior MI | 402 (16.6) | 564 (31.6) | 1271 (48.8) |

| Prior CABG | 9 (0.4) | 66 (3.7) | 565 (21.6) |

| Prior PCI | 466 (19.3) | 588 (33.0) | 1243 (47.6) |

| CKDa | 22 (0.9) | 74 (4.1) | 729 (27.9) |

| PVD | 5 (0.2) | 39 (2.2) | 463 (17.7) |

| Status post CVA/TIA | 6 (0.2) | 55 (3.1) | 473 (18.1) |

| Prior heart failure | 7 (0.3) | 32 (1.8) | 492 (18.8) |

| eGFR mL/min, median (IQR) | 84 (74–97) | 80 (65–95) | 56 (40–77) |

| EF <30% | 49 (2.6) | 63 (4.7) | 221 (11.3) |

Values are presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified. P<0.05 for each variable. BMI indicates body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVA, cerebrovascular event; EF, ejection fraction; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IQR, interquartile range; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

CKD was defined as creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dL or creatinine clearance <50 mL/min or on dialysis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Index ACS

| TIMI Risk Score for Secondary Prevention | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Risk (n=2421) | Intermediate Risk (n=1788) | High Risk (n=2618) | ||

| STEMI on presentation | 1241 (51.3) | 773 (43.2) | 840 (32.1) | <0.001 |

| Coronary angiogram (during index hospitalization) | 2342 (96.9) | 1676 (93.6) | 2161 (82.6) | <0.001 |

| Any PCI (during index hospitalization) | 1913 (79.0) | 1340 (74.9) | 1594 (60.9) | <0.001 |

| PCI in non–STE‐ACS (during index hospitalization) | 783 (67.0) | 655 (64.7) | 925 (52.3) | <0.001 |

| CABG (during index hospitalization) | 127 (5.2) | 99 (5.5) | 144 (5.5) | 0.8 |

| GRACE score >140 | 52 (2.7) | 131 (9.1) | 851 (40.0) | <0.001 |

| Killip class III/IV on admission | 42 (1.7) | 243 (9.4) | 243 (9.4) | <0.001 |

| Radial vascular access (STEMI patients) | 445 (60.6) | 256 (56.5) | 213 (49.9) | 0.009 |

| 3‐vessel disease on angiogram | 484 (20.7) | 491 (29.5) | 970 (44.7) | <0.001 |

| TIMI grade flow after PCI | 2.83±0.61 | 2.82±0.63 | 2.68±0.81 | <0.001 |

| Peak CK values, U/L | 340.5 (134–1032) | 285.0 (112–831) | 232.0 (100–646) | <0.001 |

| Peak troponin T values, ng/L | 939 (76.8) | 686 (75.3) | 1021 (78.1) | 0.300 |

| LDL‐C on admission, mg/dL | 114.00 (90–141) | 102.50 (79–130) | 88.00 (68–113) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides on admission, mg/dL | 129.00 (90–181) | 132.00 (93–193) | 129.00 (93–184) | 0.051 |

| HDL‐C on admission, mg/dL | 38.00 (32–46) | 38.00 (31–45) | 38.00 (31–45) | 0.04 |

Values are presented as n (%), mean±SD, or median (IQR). ACS indicates acute coronary syndrome; CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; CK, creatine phosphokinase; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; IQR, interquartile range; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; non–STE‐ACS, non–ST‐segment–elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Table 3.

Medication at Discharge and Clinical Outcomes

| TIMI Risk Score for Secondary Prevention | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Risk (n=2421) | Intermediate Risk (n=1788) | High Risk (n=2618) | ||

| Medication at discharge | ||||

| Aspirin | 2349 (97.7) | 1708 (96.1) | 2367 (92.7) | <0.001 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 2116 (88.0) | 1518 (85.7) | 2048 (80.3) | <0.001 |

| Statin | 2271 (95.0) | 1693 (96.1) | 2324 (92.1) | <0.001 |

| ACEI/ARB | 1712 (70.8) | 1450 (81.0) | 1980 (75.7) | <0.001 |

| β‐Blockers | 1861 (78.8) | 1433 (81.8) | 2040 (81.0) | 0.041 |

| Anticoagulants | 68 (2.8) | 79 (4.5) | 236 (9.2) | <0.001 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| 30‐d rehospitalization | 369 (17.1) | 307 (19.3) | 430 (19.5) | 0.077 |

| 30‐d recurrent MI | 32 (1.3) | 24 (1.3) | 53 (2.0) | 0.084 |

| 30‐d MACE | 173 (7.2) | 147 (8.2) | 395 (15.1) | <0.001 |

| 30‐d mortality | 26 (1.1) | 35 (2.0) | 191 (7.3) | <0.001 |

| 30‐d MI or UAP | 96 (4.0) | 76 (4.2) | 176 (6.7) | <0.001 |

| 30‐d CVA | 3 (0.1) | 8 (0.4) | 16 (0.8) | 0.52 |

| 30‐d stent thrombosis | 17 (0.7) | 14 (0.8) | 23 (0.9) | 0.77 |

| 30‐d urgent revascularization | 90 (3.7) | 63 (3.5) | 107 (4.1) | 0.60 |

| 1‐y mortalitya | 45 (1.9) | 81 (4.6) | 409 (15.8) | <0.001 |

Values are presented as n (%). Anticoagulants include warfarin, enoxaparin, dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and fondaparinux. MACE includes death, UAP, MI, CVA, stent thrombosis, and urgent revascularization. P2Y12 inhibitors include clopidogrel, ticagrelor, and prasugrel. ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; MI, myocardial infarction; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; UAP, unstable angina pectoris.

Percentages are Kaplan–Meier rates.

Table 4.

Temporal Trends in Guideline‐Recommended Therapies

| 2008 | 2010 | 2013 | 2016 | P Trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire cohort | |||||

| n | 1716 | 1720 | 1665 | 1724 | |

| PCI during hospitalization | 1192 (69.5) | 1241 (72.2) | 1164 (69.9) | 1249 (72.4) | 0.1 |

| Statins at discharge | 1548 (91.9) | 1618 (95.0) | 1535 (92.3) | 1587 (97.8) | <0.001 |

| DAPT at discharge | 1298 (75.6) | 1421 (82.6) | 1368 (82.2) | 1446 (83.9) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac rehabilitation referral | 749 (45.8) | 864 (53.0) | 623 (50.9) | 896 (60.5) | <0.001 |

| Low risk | |||||

| n | 641 | 599 | 569 | 609 | |

| PCI during hospitalization | 503 (78.5) | 489 (81.6) | 443 (77.9) | 475 (78.0) | 0.5 |

| Statins at discharge | 598 (93.6) | 573 (95.8) | 524 (92.1) | 576 (98.5) | 0.006 |

| DAPT at discharge | 527 (82.2) | 535 (89.3) | 487 (85.6) | 542 (89.0) | 0.006 |

| Cardiac rehabilitation referral | 325 (52.9) | 358 (61.8) | 261 (61.3) | 364 (67.3) | <0.001 |

| Intermediate risk | |||||

| n | 433 | 462 | 437 | 458 | |

| PCI during hospitalization | 312 (72.1) | 355 (76.8) | 325 (74.4) | 350 (76.4) | 0.2 |

| Statins at discharge | 407 (94.9) | 441 (96.3) | 411 (94.3) | 434 (98.9) | 0.01 |

| DAPT at discharge | 332 (76.7) | 390 (84.4) | 369 (84.4) | 392 (85.6) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac rehabilitation referral | 201 (47.3) | 242 (54.8) | 174 (51.9) | 259 (66.4) | <0.001 |

| High risk | |||||

| n | 642 | 659 | 659 | 657 | |

| PCI during hospitalization | 377 (58.7) | 397 (60.2) | 396 (60.1) | 424 (64.5) | 0.04 |

| Statins at discharge | 543 (88.0) | 604 (93.2) | 600 (91.2) | 577 (96.3) | <0.001 |

| DAPT at discharge | 439 (68.4) | 496 (75.3) | 512 (77.7) | 512 (77.9) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac rehabilitation referral | 223 (37.4) | 264 (43.4) | 188 (40.7) | 273 (49.6) | <0.001 |

Values are presented as n (%). DAPT indicates dual‐antiplatelet therapy; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Table 5.

Temporal Trends in Clinical Outcomes

| 2008 | 2010 | 2013 | 2016 | P Trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire cohort | |||||

| n | 1716 | 1720 | 1665 | 1724 | |

| 30‐d MACE | 215 (12.5) | 173 (10.1) | 176 (10.6) | 151 (8.8) | 0.001 |

| 30‐d mortality | 72 (4.2) | 68 (4.0) | 61 (3.7) | 51 (3.0) | 0.05 |

| 1‐y mortality | 135 (8.0) | 133 (7.8) | 136 (8.3) | 131 (7.7) | 0.9 |

| Low risk | |||||

| n | 641 | 599 | 569 | 609 | |

| 30‐d MACE | 41 (6.4) | 36 (6.0) | 46 (8.1) | 50 (8.2) | 0.11 |

| 30‐d mortality | 7 (1.1) | 4 (0.7) | 6 (1.1) | 9 (1.5) | 0.4 |

| 1‐y mortality | 8 (1.3) | 9 (1.5) | 14 (2.5) | 14 (2.3) | 0.1 |

| Intermediate risk | |||||

| n | 433 | 462 | 437 | 458 | |

| 30‐d MACE | 39 (9.0) | 36 (7.8) | 40 (9.2) | 32 (7.0) | 0.4 |

| 30‐d mortality | 8 (1.9) | 8 (1.7) | 10 (2.3) | 9 (2.0) | 0.7 |

| 1‐y mortality | 17 (4.0) | 20 (4.4) | 24 (5.6) | 20 (4.5) | 0.5 |

| High risk | |||||

| n | 642 | 659 | 659 | 657 | |

| 30‐d MACE | 135 (21.0) | 101 (15.3) | 90 (13.7) | 69 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| 30‐d mortality | 57 (8.9) | 56 (8.5) | 45 (6.9) | 33 (5.0) | 0.004 |

| 1‐y mortality | 110 (17.2) | 104 (15.8) | 98 (15.1) | 97 (15.0) | 0.2 |

Values are presented as n (%). MACE includes death, unstable angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, stent thrombosis, and urgent revascularization. MACE indicates major adverse cardiac events.

A sensitivity analysis with the same statistical methods as for the main results included only patients who were discharged alive from their index ACS hospitalization.

Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. All analyses were performed using R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

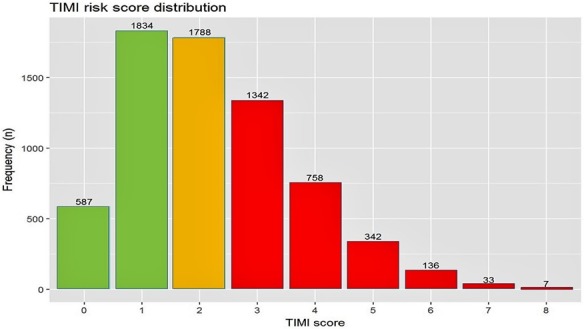

During 2008–2016, 6827 ACS patients were enrolled in the ACSIS registry. Of those, 2421 (35%) were categorized as low risk, 1788 (27%) as intermediate risk, and 2618 (38%) as high risk, according to the TRS 2oP (Figure 1). Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Compared with low‐ and intermediate‐risk patients, those at high risk were more likely to be older, to be female, and to have more comorbidities such as renal dysfunction, prior PCI, and peripheral arterial disease (P<0.001 for each). In addition, high‐risk patients presented more frequently with non–ST‐segment–elevation ACS than with ST‐segment–elevation MI and were more likely to have 3‐vessel coronary disease compared with patients at low and intermediate risk (P<0.001 for each).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score for secondary prevention in the study patients. Risk factors: age ≥75 years, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, current smoking, peripheral arterial disease, prior stroke, prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery, chronic heart failure, and estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min. Low risk: 0 to 1 risk factor; intermediate risk: 2 risk factors; high risk: ≥3 risk factors.

Patients at high risk underwent coronary angiography and stent implantation less often compared with low‐ and intermediate‐risk patients (P<0.001 for each), with no significant difference in referral for coronary artery bypass grafting (Table 2). At discharge, compared with low‐ and intermediate‐risk patients, high‐risk patients received less guideline‐recommended medical therapy, such as antiplatelet therapy and statins, and were referred less often to cardiac rehabilitation (Table 3). Among patients who underwent PCI (n=4846), high‐risk patients were treated less frequently with dual‐antiplatelet therapy (95.9%, 94.3%, and 90.7% in the low‐, intermediate‐, and high‐risk groups, respectively; P<0.001). Among patients who did not undergo PCI (n=1978), there was no difference among the groups (51.0%, 48.3%, and 50.2%, in the low‐, intermediate‐, and high‐risk groups, respectively; P=0.6).

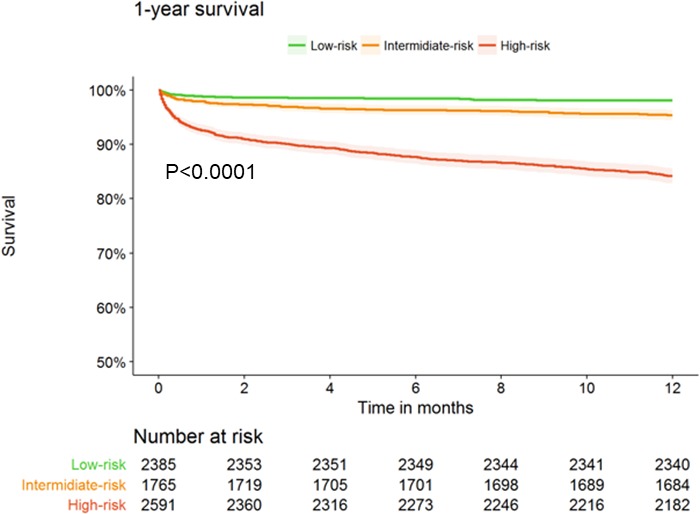

The rate of 30‐day MACE was 7.2% in patients at low risk, 8.2% in patients at intermediate risk, and 15.1% in patients at high risk (P<0.001; Table 3). Similarly, there was a graded 1‐year mortality rate by risk group (1.9% for low risk, 4.6% for intermediate risk, and 15.8% for high‐risk; P<0.001; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for 1‐year mortality in acute coronary syndrome patients according to the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score for secondary prevention.

During the past decade, there was no change in TRS 2oP (2008: median: 2.0 [interquartile range: 1.0–3.0]; mean±SD: 2.19±1.44; 2016: median: 2.0 [interquartile range: 1.0–3.0]; mean±SD: 2.22±1.44; P=0.4). Similarly, when examining only the high‐risk patients (score >2), there was no change in the TRS 2oP during that time (2008: median: 3 [interquartile range: 3.0–4.0]; mean±SD: 3.73±0.97; 2016: median: 3 [interquartile range: 3.0–4.0]; mean±SD: 3.76±0.95; P=0.4). Utilization of guideline‐recommended therapies, such as dual‐antiplatelet therapy, statins, and cardiac rehabilitation, has increased among all risk groups but remained the lowest among the high‐risk group (Table 4).

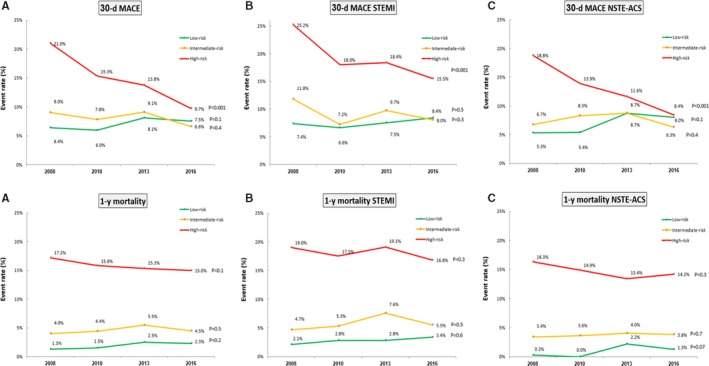

The rate of 30‐day MACE has significantly decreased among patients at high risk (from 21.0% in 2008 to 9.7% in 2016; P<0.001) but not among patients at low and intermediate risk (Figure 3A). Compared with the early period (2008–2010) and with low‐ and intermediate‐risk patients, patients at high risk had a significant decrease in 30‐day MACE in the late period (2013–2016; odds ratio: 0.54; 95% confidence interval, 0.39–0.74; P<0.001).

Figure 3.

Temporal trends of 30‐day major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and 1‐year mortality according to the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score for secondary prevention among all patients (A), patients with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (B), and patients with non‐STEMI acute coronary syndrome (NSTE‐ACS) (C).

The rate of 1‐year mortality has numerically decreased among high‐risk patients (from 17.2% in 2008 to 15.0% in 2016) but not among low‐ and intermediate‐risk patients (P=0.1; Figure 3A). In a Cox regression analysis, compared with the early period (2008–2010) and with low‐ and intermediate‐risk patients, patients at high risk had a significant decrease in 1‐year mortality in the late period (2013–2016; hazard ratio: 0.64; 95% confidence interval, 0.43–0.97; P=0.04), but this was not statistically significant after adjusting for age as a continuous variable (hazard ratio: 0.70; 95% confidence interval, 0.47–1.05; P=0.09).

Consistent qualitative results were demonstrated among patients with ST‐segment–elevation MI and non–ST‐segment–elevation ACS (Figure 3B and 3C).

In a sensitivity analysis that included only patients who were discharged alive from the index hospitalization with ACS (n=6686), consistent results were demonstrated. The rate of 30‐day MACE was 6.7% in patients at low risk, 7.3% in patients at intermediate risk, and 11.4% in patients at high risk (P<0.001). During the past decade, the rate of 30‐day MACE decreased significantly among patients at high risk (from 16.2% in 2008 to 7.7% in 2016; P<0.001) but not among patients at low and intermediate risk (Table S1). There was no significant change in the rate of 1‐year mortality among each risk group.

Discussion

In this study from a prospective biennial national registry of patients with ACS, patients at high risk for recurrent cardiovascular events based on their clinical characteristics had increased rates of 30‐day MACE and 1‐year mortality. Despite improvement in treatment strategies among all patients during the past decade, high‐risk patients were still undertreated with guideline‐recommended therapies. Most important, although the clinical outcomes of low‐ and intermediate‐risk patients admitted with an ACS have not changed over the past decade, the prognosis of high‐risk patients has significantly improved.

The term ACS encompasses several cardiac conditions that require prompt identification and appropriate treatment to reduce the risk of in‐hospital complications and future cardiovascular events. Numerous studies have demonstrated that several ACS patient populations, such as those that are elderly, are female, or have coexisting comorbidities, are still undertreated both pharmacologically and with invasive treatments, mainly because of the complexity involved in treating these patients.15 Indeed, in this study, high‐risk patients (who represented 38% of all ACS patients) were treated less frequently with guideline‐recommended therapies; paradoxically, although treatment has improved during the past decade, these patients remained undertreated. We can speculate that high‐risk patients were less likely to undergo coronary angiography, given a higher risk of contrast‐induced nephropathy, and PCI, given coronary features that increase the risk of procedural complications. In addition, high‐risk patients were treated less often with dual‐antiplatelet therapy, perhaps because of their bleeding risk and the higher use of anticoagulation. Differences in the use of other medications across the TRS 2oP groups may also be related to between‐ group differences such as the left ventricular ejection fraction. Although high‐risk patients in our study were undertreated with guideline‐recommended therapies and had worse outcomes, an analysis of temporal trends during the past decade revealed that the overall improvement in outcomes of patients with ACS derived mainly from the improvement in the outcomes of these high‐risk patients. Consequently, high‐risk patients might benefit the most from the advancement of medical and interventional treatment in comparison to patients at low and intermediate risk, for whom outcomes have not changed during the past decade.

In this study we aimed to examine risk groups that are often undertreated during and after ACS. Although there are several risk scores for cardiovascular risk estimation in patients with ACS,19, 20 we have utilized the TRS 2oP, a simple risk score based solely on the patient's clinical characteristics and not on the type of ACS, physical examination, ECG findings, or biomarkers. This score was validated in patients with prior myocardial infarction and in patients stabilized after an ACS.16 When applying this score in the IMPROVE‐IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial) study, high‐risk patients derived the greatest benefit from the addition of ezetimibe to statin therapy.21 This finding is consistent with our findings and emphasize that high‐risk patients may derive the most benefit from guideline‐recommended treatment.

Contemporary ST‐segment–elevation MI and non–ST‐segment–elevation ACS guidelines recommend treating patients similarly, regardless of their age, sex, renal status, and other clinical characteristics.22, 23 Nevertheless, our data demonstrate that clinically high‐risk patients are often undertreated in current practice. Although one may assume that patients at increased age and with additional comorbidities should be managed with a more conservative approach, our study sheds light on these patients and demonstrates they might benefit the most and should probably not be denied these therapies (medical and interventional). Nevertheless, because our study did not aim to demonstrate the causal association between treatment and outcome, future efforts should focus on further reducing the rate of recurrent cardiovascular events among high‐risk patients.

Our study has several limitations. Results are derived from the ACSIS registry, which is composed of a population admitted to cardiology wards and intensive cardiac care units nationwide with the diagnosis of ACS. Patients with less typical chest pain, although ultimately diagnosed as ACS, may have been managed in the internal medicine wards and thus are not represented in the current study. In addition, the ACSIS registry has limited follow‐up data beyond the index hospitalization with respect to long‐term medical treatment, adherence to treatment, and additional interventions. Consequently, the long‐term outcomes may be significantly influenced by these and other postdischarge intervening factors. Data regarding complete revascularization were not available. Our study utilized the TRS 2oP even though this score was developed among patients stabilized after MI and was demonstrated to predict MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death. We have extrapolated this score in the current study because it incorporates clinical characteristics and thus is very useful and readily available in clinical practice. In addition, it includes the wide spectrum of ACS patients, both non–ST‐segment–elevation ACS and ST‐segment–elevation MI. Moreover, the sensitivity analysis, which included only patients who were stabilized after ACS and were discharged alive, demonstrated consistent results.

Conclusion

Despite an improvement in the management of high‐risk ACS patients during the past decade, they are still undertreated with guideline‐recommended therapies. Nevertheless, the outcome of high‐risk ACS patients has improved significantly in the past decade; therefore, these patients should not be denied these therapies.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. Temporal Trends in Clinical Outcomes in Patients Who Survived the Index Acute Coronary Syndrome Hospitalization

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009885 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009885.)

References

- 1. Eagle KA, Hirsch AT, Califf RM, Alberts MJ, Steg PG, Cannon CP, Brennan DM, Bhatt DL. Cardiovascular ischemic event rates in outpatients with symptomatic atherothrombosis or risk factors in the United States: insights from the REACH Registry. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2009;8:91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morrow DA. Cardiovascular risk prediction in patients with stable and unstable coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2010;121:2681–2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. The Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS‐II): a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, Buring J, Hennekens C, Kearney P, Meade T, Patrono C, Roncaglioni MC, Zanchetti A. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta‐analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1849–1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dargie HJ. Effect of carvedilol on outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with left‐ventricular dysfunction: the CAPRICORN randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1385–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mehta SR, Bassand JP, Chrolavicius S, Diaz R, Eikelboom JW, Fox KA, Granger CB, Jolly S, Joyner CD, Rupprecht HJ, Widimsky P, Afzal R, Pogue J, Yusuf S. Dose comparisons of clopidogrel and aspirin in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:930–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moye LA, Basta L, Brown EJ Jr, Cuddy TE, Davis BR, Geltman EM, Goldman S, Flaker GC, Milton P, Jacques R, Jean LR, John R, John HW, Hawkins CM. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. The SAVE Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, Rouleau JL, Kober L, Maggioni AP, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Van de Werf F, White H, Leimberger JD, Henis M, Edwards S, Zelenkofske S, Sellers MA, Califf RM. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1893–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, Neaton J, Martinez F, Roniker B, Bittman R, Hurley S, Kleiman J, Gatlin M. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1309–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Rader DJ, Rouleau JL, Belder R, Joyal SV, Hill KA, Pfeffer MA, Skene AM. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, Darius H, Lewis BS, Ophuis TO, Jukema JW, De Ferrari GM, Ruzyllo W, De Lucca P, Im K, Bohula EA, Reist C, Wiviott SD, Tershakovec AM, Musliner TA, Braunwald E, Califf RM. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mukherjee D, Fang J, Chetcuti S, Moscucci M, Kline‐Rogers E, Eagle KA. Impact of combination evidence‐based medical therapy on mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2004;109:745–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anderson L, Taylor RS. Cardiac rehabilitation for people with heart disease: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(12):CD011273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, Snyder JK, Sink KM, Rocco MV, Reboussin DM, Rahman M, Oparil S, Lewis CE, Kimmel PL, Johnson KC, Goff DC Jr, Fine LJ, Cutler JA, Cushman WC, Cheung AK, Ambrosius WT. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood‐pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chow CK, Jolly S, Rao‐Melacini P, Fox KA, Anand SS, Yusuf S. Association of diet, exercise, and smoking modification with risk of early cardiovascular events after acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2010;121:750–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leonardi S, Bueno H, Ahrens I, Hassager C, Bonnefoy E, Lettino M. Optimised care of elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2018;7:287–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bohula EA, Bonaca MP, Braunwald E, Aylward PE, Corbalan R, De Ferrari GM, He P, Lewis BS, Merlini PA, Murphy SA, Sabatine MS, Scirica BM, Morrow DA. Atherothrombotic risk stratification and the efficacy and safety of vorapaxar in patients with stable ischemic heart disease and previous myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2016;134:304–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kornowski R. The ACSIS Registry and primary angioplasty following coronary bypass surgery. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;78:537–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Segev A, Matetzky S, Danenberg H, Fefer P, Bubyr L, Zahger D, Roguin A, Gottlieb S, Kornowski R. Contemporary use and outcome of percutaneous coronary interventions in patients with acute coronary syndromes: insights from the 2010 ACSIS and ACSIS‐PCI surveys. EuroIntervention. 2012;8:465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fox KA, Dabbous OH, Goldberg RJ, Pieper KS, Eagle KA, Van de Werf F, Avezum A, Goodman SG, Flather MD, Anderson FA Jr, Granger CB. Prediction of risk of death and myocardial infarction in the six months after presentation with acute coronary syndrome: prospective multinational observational study (GRACE). BMJ. 2006;333:1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morrow DA, Antman EM, Charlesworth A, Cairns R, Murphy SA, de Lemos JA, Giugliano RP, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. TIMI risk score for ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: a convenient, bedside, clinical score for risk assessment at presentation: an intravenous nPA for treatment of infarcting myocardium early II trial substudy. Circulation. 2000;102:2031–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bohula EA, Morrow DA, Giugliano RP, Blazing MA, He P, Park JG, Murphy SA, White JA, Kesaniemi YA, Pedersen TR, Brady AJ, Mitchel Y, Cannon CP, Braunwald E. Atherothrombotic risk stratification and ezetimibe for secondary prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:911–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli‐Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimsky P. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, Bax JJ, Borger MA, Brotons C, Chew DP, Gencer B, Hasenfuss G, Kjeldsen K, Lancellotti P, Landmesser U, Mehilli J, Mukherjee D, Storey RF, Windecker S, Baumgartner H, Gaemperli O, Achenbach S, Agewall S, Badimon L, Baigent C, Bueno H, Bugiardini R, Carerj S, Casselman F, Cuisset T, Erol C, Fitzsimons D, Halle M, Hamm C, Hildick‐Smith D, Huber K, Iliodromitis E, James S, Lewis BS, Lip GY, Piepoli MF, Richter D, Rosemann T, Sechtem U, Steg PG, Vrints C, Luis Zamorano J. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST‐segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST‐Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:267–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Temporal Trends in Clinical Outcomes in Patients Who Survived the Index Acute Coronary Syndrome Hospitalization