Abstract

Background

2-Phenylethanol (2-PE) is a higher aromatic alcohol that is widely used in the perfumery, cosmetics, and food industries and is also a potentially valuable next-generation biofuel. In our previous study, a new strain Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 was isolated to produce 2-PE from glucose through the phenylpyruvate pathway.

Results

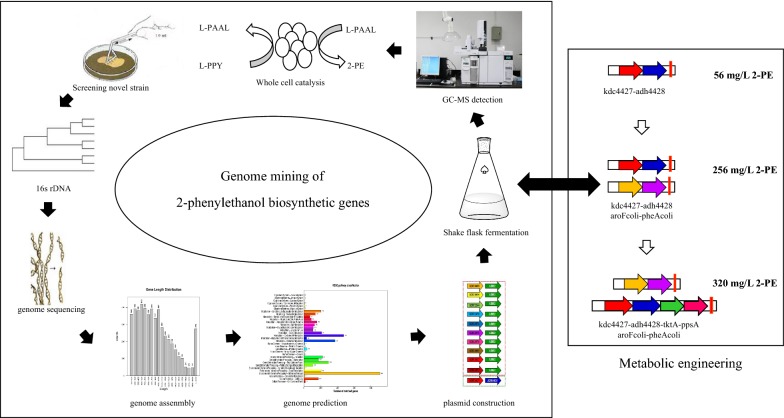

In this study, candidate genes for 2-PE biosynthesis were identified from Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 by draft whole-genome sequence, metabolic engineering, and shake flask fermentation. Subsequently, the identified genes encoding the 2-keto acid decarboxylase (Kdc) and alcohol dehydrogenase (Adh) enzymes from Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 were introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3) to construct a high-efficiency microbial cell factory for 2-PE production using the prokaryotic phenylpyruvate pathway. The enzymes Kdc4427 and Adh4428 from Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 showed higher performances than did the corresponding enzymes ARO10 and ADH2 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, respectively. The E. coli cell factory was further improved by overexpressing two upstream shikimate pathway genes, aroF/aroG/aroH and pheA, to enhance the metabolic flux of the phenylpyruvate pathway, which resulted in 2-PE production of 260 mg/L. The combined overexpression of tktA and ppsA increased the precursor supply of erythrose-4-phosphate and phosphoenolpyruvate, which resulted in 2-PE production of 320 mg/L, with a productivity of 13.3 mg/L/h.

Conclusions

The present study achieved the highest titer of de novo 2-PE production of in a recombinant E. coli system. This study describes a new, efficient 2-PE producer that lays foundation for the industrial-scale production of 2-PE and its derivatives in the future.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13068-018-1297-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: 2-Phenylethanol, Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087, 2-Keto acid decarboxylase, Alcohol dehydrogenase, Phenylpyruvate pathway, Metabolic engineering

Background

2-Phenylethanol (2-PE), an aromatic alcohol with a rose-like fragrance, is commonly used as a flavor component in the perfumery, cosmetics, and food industries, and it is also a candidate molecule for next-generation biofuels due to its high energy potential [1]. In addition, 2-PE is an important compound for the production of derivatives such as styrene, phenylethyl acetate, and other valuable compounds [2].

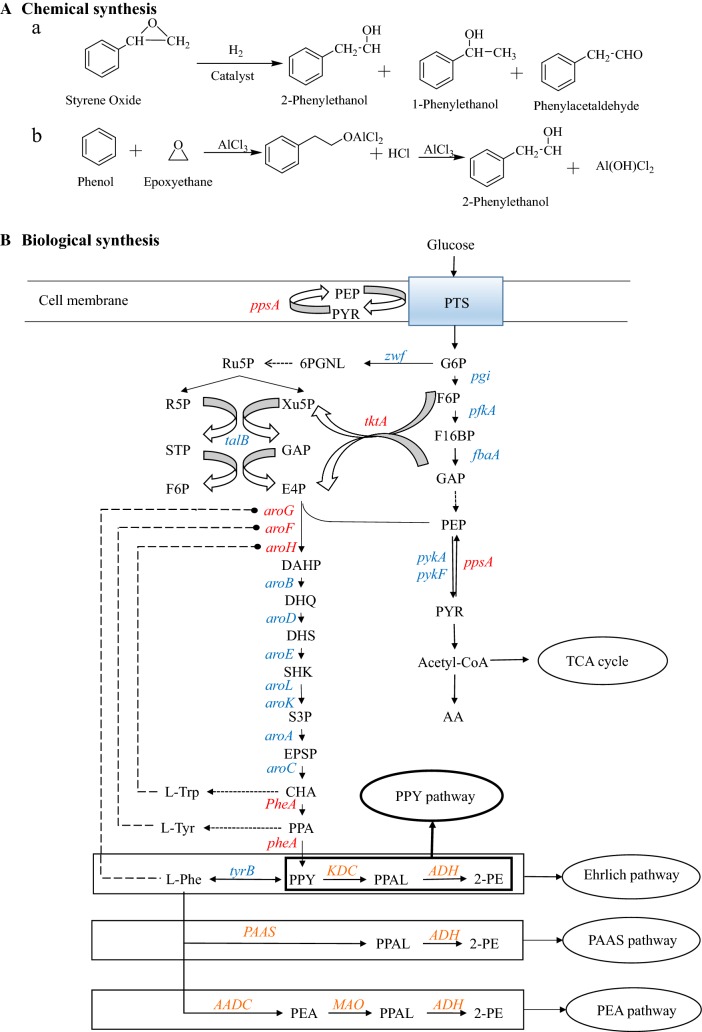

Currently, 2-PE is mainly produced by two chemical processes: (1) styrene oxide reduced with H2 to produce mixtures of 2-PE and its derivatives (Fig. 1a) [3] and (2) ethylene and benzene conversion to 2-PE in the presence of molar quantities of aluminum chloride through the Friedel–Craft reaction (Fig. 1b) [4]. In addition, 2-PE is also a byproduct of the production of propylene oxide [2, 5]. Chemical production processes are considered environmentally unfriendly due to their requirements for high temperature, high pressure, and strong acids or alkalis. Furthermore, these processes are connected with the production of unwanted byproducts, thus reducing efficiency and increasing downstream costs [5]. In addition, US and European legislations have restricted the usage of the chemically synthesized 2-PE in some applications, especially in the food industries and cosmetic products [6]. Natural 2-PE is obtained by extraction from the essential oils of plants and flowers. However, this process is costly and inefficient, and cannot satisfy the large market [7]. Therefore, the bioproduction of 2-PE by microorganisms is a promising alternative to the traditional preparation processes.

Fig. 1.

Synthetic route of 2-PE. A 2-PE chemical synthesis. a Friedel–Craft reaction of ethylene oxide. b Catalytic reduction of styrene oxide. B 2-PE biosynthesis in E. coli. Metabolite abbreviations: PTS, phosphotransferase system; G6P, glucose 6-phosphate; F6P, fructose-6-phosphate; F16BP, fructose-1,6-diphosphate; GAP, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; R5P, ribose-5-phosphate; Xu5P, ribulose-5-phosphate; STP, sedoheptulose-7-phosphate; E4P, erythrose 4-phosphate; DAHP, 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate; DHQ, 3-dehydroquinate; DHS, 3-dehydro-shikimate; SHK, shikimate; S3P, shikimate-3-phosphate; EPSP, 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate; CHA, chorismate; PPA, prephenate; PPY, phenylpyruvate; PPAL, phenylacetaldehyde; PEA, phenylethylamine; l-Phe, l-phenylalanine; l-Tyr, l-tyrosine; l-Trp, l-tryptophan. Genes and enzymes: zwf, glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase; pgi, glucose 6-phosphate isomerase; fbaA, fructose-1,6-diphosphate aldolase; pykA, pyruvate kinase II; pykF, pyruvate kinase I; ppsA, phosphoenolpyruvate synthase; tktA, transketolase; talB, transaldolase B; aroG, DAHP synthetase feedback inhibited by Phe; aroH, DAHP synthetase feedback inhibited by Trp; aroF, DAHP synthetase feedback inhibited by Tyr; aroB, 3-dehydroquinate synthase; aroD, 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase; aroE, shikimate dehydrogenase; aroL, shikimate kinase 2; aroK, Shikimate kinase 1; aroA, 3-phosphoshikimate 1-carboxyvinyltransferase; aroC, chorismate synthase; pheA, fused chorismate mutase and prephenate dehydratase; tyrB, aromatic-amino-acid aminotransferase; AADC, aromatic amino acid decarboxylase; MAO, amine oxidase; KDC, alpha-keto-acid decarboxylase; Adh, alcohol dehydrogenase; PAAS, phenylacetaldehyde synthase; TCA cycle, tricarboxylic acid cycle

In nature, there are several ways to synthesize 2-PE, including phenylacetaldehyde synthase (PAAS) pathway, Phenylethylamine (PEA) pathway and the Ehrlich pathway (Fig. 1B) [1, 2, 8–10]. PEA pathway is present in several mammalian tissues and rarely in microorganisms [11]. PAAS pathway mainly exists in plants with a unique dual functionality enzyme PAAS, which could catalyze l-Phe into phenylacetaldehyde directly [10, 12]. Among them, the Ehrlich pathway is thought to be the most significant pathway in eukaryotes. In the Ehrlich pathway, l-Phe is transaminated to phenylpyruvate (PPY) by a transaminase, which is decarboxylated to phenylacetaldehyde (PPAL) by phenylpyruvate decarboxylase, and then reduced to 2-PE by alcohol dehydrogenase [13, 14]. The most prominent microorganisms that carry out the Ehrlich pathway are yeasts, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae [15], Kluyveromyces marxianus [16], and Zygosaccharomyces rouxii [17]. Microbial bioconversion of l-Phe is an effective strategy for producing 2-PE. For instance, Kim et al. reported the use of 10 g/L l-Phe as a sole nitrogen source to produce 4.8 g/L 2-PE in S. cerevisiae by overexpressing amino acid transaminases (ARO9), phenylpyruvate decarboxylase (ARO10) and Aro80 (a member of the Zn2Cys6 proteins family, which activates expression of the ARO9 and ARO10 genes in response to aromatic amino acids) in an ALD3 (alcohol dehydrogenase, competing with 2-PE production) deletion strain [13]. In another example, a recombinant Escherichia coli harboring a coupled reaction pathway comprising of aromatic transaminase, phenylpyruvate decarboxylase, carbonyl reductase, and glucose dehydrogenase as a catalyst, produced an approximately 96% final product conversion yield of 2-phenylethanol from 40 mM l-Phe [18]. Although the Ehrlich pathway is the main method used for industrial fermentation, the conversion rate from l-Phe to 2-PE is very high, and this process is always faced with an unavoidable problem: the excessively high cost of feedstock l-Phe, which is the main limiting factor for 2-PE production by the Ehrlich pathway.

Thus, de-novo synthesis of 2-PE from glucose via the shikimate pathway is a promising pathway. Erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P) and phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) from glycolysis and the pentose-phosphate pathway, respectively, are condensed. Subsequently, the intermediates chorismate and prephenate are converted to phenylpyruvate, and then phenylpyruvate reacts through the Ehrlich pathway to synthesize 2-PE. This synthesis process is also called the phenylpyruvate pathway [2]. Compared with the Ehrlich pathway, the phenylpyruvate pathway has a great advantage due to its production of 2-PE at low cost and using renewable sugar as a raw material. Yeasts have been reported to produce 2-PE de novo from glucose; however, the final concentration of 2-PE in culture is very low. For this reason, all current fermentation methods for 2-PE use l-Phe as feedstock. In addition, the yeast fermentation process usually takes several days, which leads to low production of 2-PE [7, 19, 20].

Bacteria, especially E. coli, are an attractive host organism because they have unparalleled rapid growth kinetics, simple media requirements, high cell densities, and readily transform DNA [21]. E. coli has been successfully engineered to produce a wide range of biofuels and chemicals, including 1-propanol, 1-butanol, 1,4-butanediol, 2,3-butanediol, isopropanol, and (R)-1,2-phenylethanediol [22, 23]. In alcohol production strategies, one critical enzyme is 2-keto-acid decarboxylase (KDC), which is common in plants, yeasts and fungi but less so in bacteria [13–25]. Liao et al. engineered E. coli to produce various alcohols by overexpressing different heterologous 2-keto-acid decarboxylases (KDCs) and alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs); 2-PE was detected, and the highest titer of 2-PE (57 mg/L) was obtained when ARO10 and ADH2 from S. cerevisiae were co-expressed [24]. However, for the recombinant E. coli systems harboring the foreign genes, the overexpression of all the genes in soluble and active forms is always a bottleneck [25]. Therefore, developing new enzymes, especially finding highly specific and active phenylpyruvate decarboxylases in prokaryotes, is critical for the biosynthesis of 2-PE. Although 2-PE has been detected in the cultures of several bacterial species, including Achromobacter eurydice [26], Acinetobacter calcoaceticus [27], Pseudomonas putida [28], Nocardia sp. 239 [29], and Thauera aromatica [30], indicating that de-novo synthesis of 2-PE exists in some bacteria, no further progress has been reported.

We have previously reported the isolation and identification of a new strain, Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087, which can produce 2-PE using a de novo synthetic pathway with monosaccharide as a carbon source and NH4Cl as a nitrogen source [8]. This is the first wild bacterium validated to produce 2-PE using glucose as sole carbon source thus far. However, unlike E. coli, this wild strain is not suitable for gene manipulation and fermentation control because of the lack of engineering tools and fermentation control strategies. In addition, this wild strain produces a large amount of acetoin and acetic acid in addition to 2-PE, and these products inhibit the growth of the bacteria. Based on the above reasons, we attempted to search for the 2-PE biosynthetic pathway, specifically, the genes encoding Kdc and Adh in the whole genome of Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087. Subsequently, the genes of the 2-PE biosynthetic pathway were heterologously overexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3). Then, four upstream pathway genes aroF/aroG/aroH, pheA, tktA, and ppsA were screened and overexpressed to construct a highly efficient engineered strain for the production of 2-PE.

Results

Genome sequencing, assembly, annotation, and bioinformatic analysis

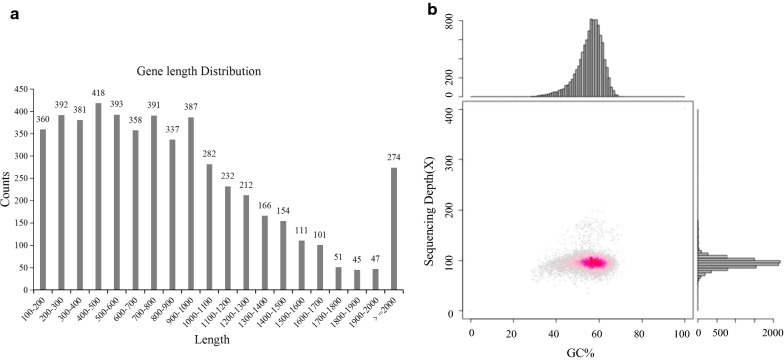

In this study, we sequenced the genome of Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 using an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencing platform (Fig. 2). A total of 504 Mb of data were produced for Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 (DDBJ/ENA/GenBank number: QFXN00000000). Based on the assembled result of Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 (Fig. 2a), we found that the genome size was 5,110,710 bp; the GC content was 55.56% (Fig. 2b); the number of scaffolds was 56, and the number of contigs was 373. Genome analysis revealed that the Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 genome contained 5112 genes; the total length of the genes was 4,505,565 bp, comprising 88.16% of the genome; the number of tRNAs was 57; and the number of rRNAs was 0. All the genes were analyzed by using the KEGG, COG, Swiss-Prot, TrEMBL, NR, and GO databases for functional annotation. By analyzing the genes’ predicted functions, nine genes related to the 2-PE biosynthesis pathway were identified by searching for similar proteins using NCBI (Additional file 2: Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Genome sequencing results for Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087. a Gene length distribution map. b Correlation analysis of GC content and depth

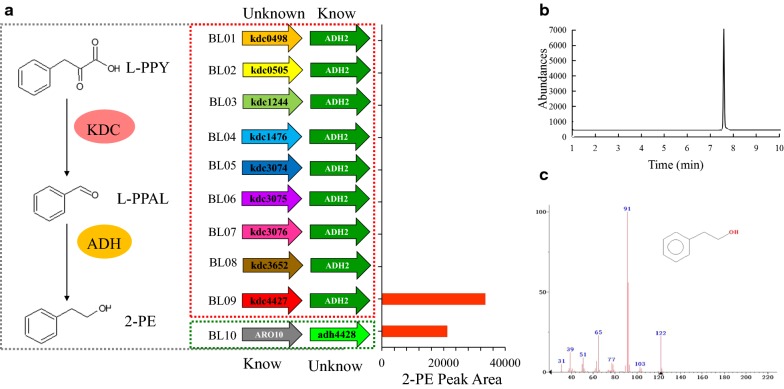

Overexpression of candidate Kdc and Adh in E. coli BL21 for the detection of 2-PE

In our previous study, Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 was validated for the production of 2-PE from phenylpyruvate through the Ehrlich pathway [8]. Therefore, candidate enzyme genes for the 2-PE pathway were predicted from the Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 genomic sequence based on their protein sequence homology with known Ehrlich pathway enzymes (Table S1). Next, the predicted candidates kdc0498, kdc0505, kdc1244, kdc1476, kdc3074, kdc3075, kdc3076, kdc3652, and kdc4427 from Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 were examined in E. coli BL21(DE3) in combination with ADH2 from S. cerevisiae. As shown in Fig. 3a, 2-PE was detected in the BL09 strain (kdc4427 and ADH2) by GC–MS, but it was not detected in the others strains; therefore, we concluded that kdc4427 is the gene encoding phenylpyruvate decarboxylase. Furthermore, 2-PE was detected in the BL11 strain (ARO10 and adh4428) by GC–MS, so we hypothesized that adh4428 is the gene encoding phenylethanol dehydrogenase.

Fig. 3.

Validation of 2-PE biosynthesis by engineered E. coli. a Engineered E. coli was cultured in LB medium and detected with GC–MS; b Graph of GC; c graph of GC–MS

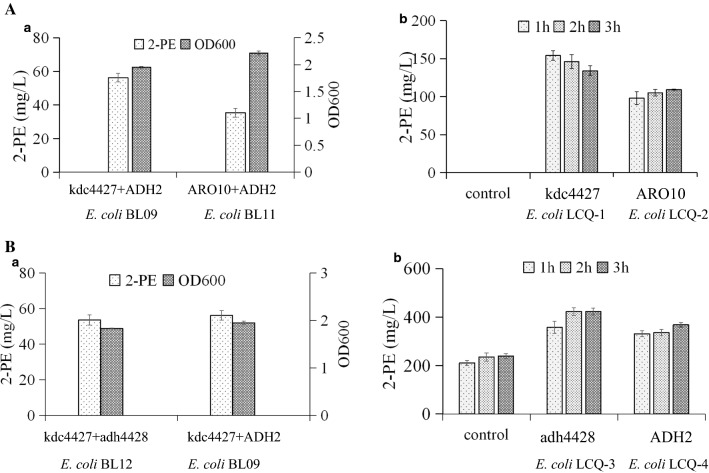

Comparison of Kdc4427 with yeast ARO10

In previous studies, it was found that ARO10, Pdc5, and Thi3 from S. cerevisiae, Kivd from Lactococcus lactis, and Pdc from Clostridium acetobutylicum can decarboxylate phenylpyruvate, with ARO10 showing the best properties [14, 24, 31]. Here, we compared ARO10 with Kdc4427. As shown in Fig. 4A.a, the expression of ADH2 with kdc4427 led to production of 56 mg/L 2-PE in the shake-flask fermentation, which was higher than the production achieved with ARO10 (35 mg/L). Based on this result, Kdc4427 is more suitable for 2-PE production than ARO10 in the host E. coli BL21(DE3).

Fig. 4.

Characterization of Kdc4427 and Adh4428. A Characterization of Kdc4427 and comparison with corresponding ARO10. a E. coli BL09 and E. coli BL11 cells were cultivated, and their cell growth (OD600) and 2-PE production titers were compared. b Phenylpyruvate decarboxylase from Kdc4427 and ARO10 in recombinant E. coli BL21(DE3) whole cells. The conversion of 1 g/L phenylpyruvate to 2-PE. B Characterization of Adh4428 and comparison with corresponding ADH2. a E. coli BL12 and E. coli BL09 cells were cultivated, and their cell growth (OD600) and 2-PE production titers were compared. b Phenylpyruvate dehydrogenase from Adh4428 and ADH2 in recombinant E. coli BL21(DE3) whole cells. The conversion of 1 g/L phenylacetaldehyde to 2-PE

A similar result was also observed in the whole-cell bioconversion. As shown in Fig. 4A.b, E. coli LC01 harboring pETDuet-kdc4427 produced more 2-PE from phenylpyruvate than did LC02 harboring pETDuet-ARO10, suggesting that Kdc4427 enzymatic activity is higher than that of ARO10 during 2-PE production with the host E. coli BL21(DE3). In addition, we found an interesting phenomenon: PAAL was not detected during conversion. One possible reason is that endogenous alcohol dehydrogenase of E. coli can catalyze the conversion of all PAAL produced by KDCs to 2-PE. In fact, three candidate genes—yqhD, yjgB, and yahK—have been identified, and yqhD has been experimentally confirmed as a broad-substrate alcohol dehydrogenase [32]. In addition, this result suggested that KDCs are rate-limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of 2-PE with E. coli BL21(DE3).

To find out the reasons why Kdc4427 is more efficient in the production of 2-PE than ARO10, the protein sequences of them were analyzed. ARO10 has three substrate-bound amino acid residues, which are I335, Q448, and M624, respectively [33]. Three substrate-bound amino acid residues of KDC4427 are predicted to be T290, A387, and I542 by using a homology model. Then comparing the Clustalw base sequences, we found that the substrate-bound sites of ARO10 and Kdc4427 are at the same position in the structure (Additional file 1: Figure S1). And Kdc4427 is also predicted to be an indolepyruvate decarboxylase (IPDC). However, why it has a higher phenylpyruvate decarboxylase activity needs to be further studied.

Comparison of Adh4428 with yeast ADH2

To better characterize Adh4428, it was compared with the commonly used alcohol dehydrogenase ADH2 from S. cerevisiae in the shake-flask fermentation and whole-cell bioconversion. As shown in Fig. 4B.a, the 2-PE yield in E. coli BL12 harboring pETDuet-kdc4427 and pACYCDuet-adh4428 was approximately the same as that in E. coli BL09 harboring pETDuet-kdc4427 and pACYCDuet-ADH2. One possible reason is that alcohol dehydrogenase is not the rate-limiting step in the biosynthesis of 2-PE. Thus, we conducted whole-cell bioconversion for comparison. Cells with no heterologous gene, LC03 cells (pACYCDuet-adh4428), and LC04 cells (pACYCDuet-ADH2) were collected in 10 mL PBS buffer, and PAAL was added to a final concentration of 1 g/L PAAL. As shown in Fig. 4B.b, the control cells produced approximately 200 mg/L 2-PE. This result confirms the previous hypothesis that endogenous alcohol dehydrogenase of E. coli can catalyze the conversion PAAL to 2-PE. Overexpression of Adh4428 in E. coli produced approximately 420 mg/L 2-PE, which was slightly higher than that produced by the overexpression of ADH2. The data were further analyzed using SPSS 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Independent samples t-tests were used to compare the differences in the catalytic efficiency of PPY to 2-PE between Adh4428 and ADH2. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The results showed that they did not have a significant difference in the catalytic efficiency of PPY to 2-PE in the first hour (p-values 0.119), meanwhile they had significant differences in the second and third hours (p-values both 0.000). Anyway, Adh4428 was preferred for the 2-PE production compared with ADH2. In addition, we also attempted to express only Kdc4427 in E. coli BL21(DE3) to produce 2-PE with relying on endogenous dehydrogenation. The 2-PE yield in E. coli LCQ-1 harboring pETDuet-kdc4427 was lower than that in E. coli BL12 harboring pETDuet-kdc4427 and pACYCDuet-adh4428 (Additional file 1: Figure S2). Therefore, though overexpression of heterogenous Adh4428 may be a burden to the host, it still necessarily needed for 2-PE production in E. coli.

Carbon flux optimization of l-Phe biosynthesis

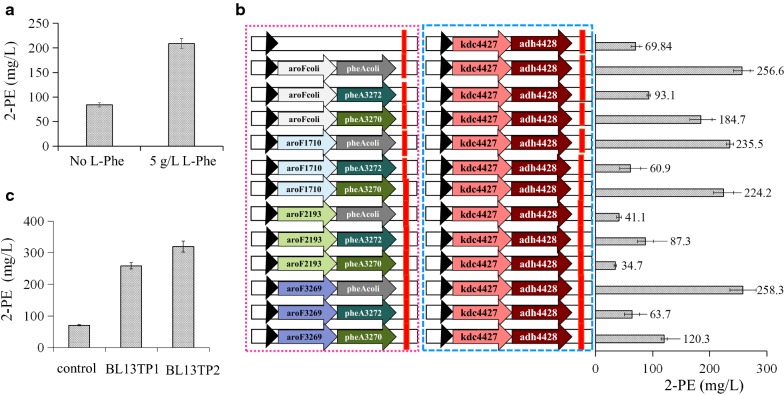

When 5 g/L l-Phe was added to the medium, 2-PE production was significantly increased from 70 to 210 mg/L in E. coli BL13 (Fig. 5a). This result suggests that the l-Phe supply is a limiting factor inside the cell, and increasing the carbon flow to l-Phe should significantly improve the yield of 2-PE via the de novo pathway.

Fig. 5.

Effects of the overexpression of key upstream genes on 2-PE production. a Effect of l-Phe addition on 2-PE production. b Effects of the overexpression of candidate aroF/aroG/aroH and pheA genes on 2-PE production. Engineered E. coli cells were cultivated, and 2-PE production titers were compared. c Effects of overexpression of the aroF, pheA, ppsA, and tktA genes on 2-PE production. Engineered E. coli cells were cultivated and 2-PE production titers were compared

DAHP synthase, which is the first committed step in general aromatic amino acid synthesis, controls carbon flow into l-Phe biosynthesis. E. coli contains three isoenzymes of DAHP synthase occur, encoded by aroF (Tyr-sensitive DAHP synthase), aroG (Phe-sensitive enzyme), and aroH (Tryptophane-sensitive enzyme), respectively [34]. According to known genome sequencing from E. coli and gene function prediction, aroG1710 may encode a Phe-sensitive DAHP synthase; aroF3269 may encode a Tyr-sensitive enzyme, and aroH2193 may encode a Tryptophane-sensitive enzyme. In an attempt to further increase 2-PE production by the E. coli strain, we examined the combinatorial effects of candidate aroF/aroG/aroH and pheA. Specifically, aroG1710, aroH2193, aroF3269, pheA3270, and pheA3272 from Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087, and aroFcoli and pheAcoli from E. coli, were evaluated for their ability to produce 2-PE. Overexpressing pheAcoli together with aroFcoli or aroF3269 generated the highest production of 2-PE among all combinations, with yields of 256 and 258 mg/L, respectively. These yields were higher than that achieved with aroG1710 (235 mg/L) and are much higher than that achieved with aroH2193 (41 mg/L). These results suggested Tyr-repressible aroF may have the greatest effect on l-Phe biosynthesis among the DAHP synthase genes (aroF, aroG, and aroH). In addition, the effects of pheAcoli, pheA3272, and pheA3270 on 2-PE production were compared. As shown in Fig. 5b, the largest outputs of 2-PE are from the strains harboring pheAcoli, followed by the strains harboring pheA3270, and then the strains harboring pheA3272. In summary, after 24 h of cultivation, the 2-PE titers reached a maximum of approximately 260 mg/L with co-expression of aroF and pheA, while the control (harboring pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 and pETDuet-1) produced approximately 70 mg/L 2-PE (Fig. 5c). These results confirmed that the aroF and pheA genes can help to improve l-Phe and l-Phe derivatives production, similar to the results reported in previous studies [35, 36].

Carbon flux optimization of carbon central metabolic pathways

According to the phenylpyruvate pathway, two molecules of PEP and one molecule of E4P from carbon central metabolism are required to produce one molecule of l-Phe. PEP is predominantly utilized in the phosphotransferase system (PTS), which is responsible for the translocation and phosphorylation of glucose, converting one PEP molecule to pyruvate (Fig. 1B). Overexpression of ppsA encoding PEP synthase can recycle pyruvate generated by PTS-mediated glucose transport to PEP, which is an important approach for increasing the carbon flux from PEP to the l-Phe pathway. Overexpression of tktA (which encodes transketolase) is an effective strategy for increasing E4P production [37]. In this study, the ppsA and tktA genes from E. coli were overexpressed in the E. coli BL13 (pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh2) in order to improve the intracellular pools of PEP and E4P, respectively, and thus enhancing 2-PE production. As shown in Fig. 5c, E. coli BL13TP2 (harboring pET-aroFcoli–pheAcoli–ppsA–tktA and pACYC-kdc4427–adh4428) accumulated 320 mg/L 2-PE after 24 h of fermentation, which represents 123% and 457% improvements in 2-PE production by E. coli BL13AP1 (harboring pET-ppsA–tktA and pACYC-kdc4427–adh4428) and E. coli BL13AP0 (harboring pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428), respectively.

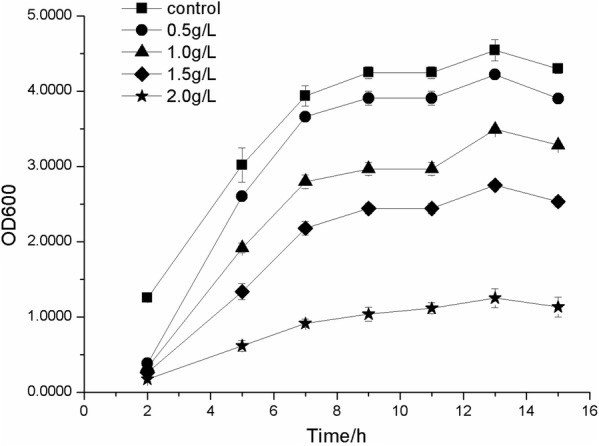

2-PE toxicity assay

To evaluate 2-PE toxicity on E. coli BL21(DE3), the effect of exogenous addition of 2-PE at different concentrations (0.5 g/L, 1 g/L, 1.5 g/L, and 2 g/L) on growing cultures was investigated. An OD600 of 4.7 was reached in the absence of 2-PE (supplemental material). When the concentration of 2-PE was 0.5 g/L, slight growth inhibition was observed. With increasing concentrations of 2-PE, bacterial cell growth inhibition became more apparent; in particular, when the concentration of 2-PE increased to 2 g/L, bacterial cells were severely inhibited, and the OD600 was maintained at approximately 1.0 (Fig. 6). In situ product removal (ISPR) can help to ease the burden of end-product toxicity on bacteria. Various kinds of solvents, such as oleic acid, oleyl alcohol, miglyol, isopropyl myristate, and polypropylene glycol, have been tested for their ability to improve the production of 2-PE compounds [13, 19, 22, 38]. In addition, ionic liquids were also used for ISPR [39] as well as solid phase extraction [40]. In the future, ISPR in combination with genetic approaches could also be used to increase 2-PE tolerance and production capacity of engineered E. coli.

Fig. 6.

Tolerance of E. coli BL21(DE3) cells to 2-PE toxicity. Growth response of E. coli BL21(DE3) cells to 0, 0.5 g/L, 1.0 g/L, 1.5 g/L, 2.0 g/L 2-PE in LB medium. Error bars represent one standard deviation from triplicate experiments

Discussion

PE is a higher aromatic alcohol widely used in the perfumery, cosmetics, and food industries and even in biofuels. In our previous study, a new strain Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 was isolated and verified to produce 2-PE using a de novo synthetic pathway with monosaccharide as a carbon source and NH4Cl as a nitrogen source [8]. To investigate the prokaryotic 2-PE biosynthesis pathway, the whole genome of Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 was sequenced, and we found that overexpression of the kdc4427 and adh4428 genes in E. coli BL21(DE3) could cause the accumulation of 2-PE. To the best of our knowledge, Kdc4427 is the only phenylpyruvate decarboxylase found and verified in bacteria thus far. To better characterize Kdc4427, ARO10 from S. cerevisiae was used for comparison in the shake-flask fermentation and in whole-cell conversion. Based on our results, Kdc4427 has higher phenylpyruvate decarboxylase activity than ARO10. In addition, we also identified and characterized Adh4428, which has higher phenylacetaldehyde dehydrogenase activity than Adh2 from S. cerevisiae. Interestingly, we found that endogenous E. coli alcohol dehydrogenase can also catalyze the conversion of PAAL to 2-PE. In this study, we describe the engineering of E. coli (kdc4427, adh4428, aroF, pheA, tktA, and ppsA) for 2-PE production from glucose, leading to a final production titer of 320 mg/L (with productivity of 13.3 g/L/h) in shake-flask fermentation, which represents a 4.6-fold improvement over the control strains (kdc4427 and adh4428). To the best of our knowledge, this is the highest titer of de novo production of 2-PE reported in engineered E. coli in shake-flask fermentation.

Previously, E. coli was also used as a cell factory to product 2-PE. For instance, Liao et al. overexpressed ARO10 and ADH2 from S. cerevisiae in E.coli BW25113/F′ [traD36, proAB+, lacIq ZΔM15], and the resulting strain produced 57 mg/L 2-PE in 40 h [24]. In this study, we also introduced ARO10 and ADH2 into E. coli and attained 35 mg/L 2-PE in 24 h. Subsequently, Hwang et al. constructed the yeast Ehrlich pathway into E. coli, but failure to overexpress all exogenous proteins in a soluble and active form prevented a high yield of 2-PE [18], and they ultimately used l-Phe as feedstock. The discovery of Kdc4427 compensates for the lack of prokaryotic phenylpyruvate decarboxylases and provides new genes for the bioengineering of 2-PE and its derivatives in the future. Recently, Kang et al. attempted to construct a heterologous pathway to produce 2-PE in E. coli by overexpressing ADH1 from S. cerevisiae, KDC from Pichia pastoris GS115, pheAfbr and aroFwt, and this modified strain ultimately produced 285 mg/L 2-PE in semisynthetic medium containing 0.4 g/L l-Tyr and 3 g/L yeast extract (2% l-Phe). This study also introduced pheA and aroF into E. coli BL13, and the resulting strain produced 260 mg/L 2-PE in a synthetic medium. Although the 2-PE titer was slightly lower than previously reported due to the different compositions of the medium, this study really achieved de novo production of 2-PE from glucose in engineered E. coli. Furthermore, after the stain was modified to be E. coli BL13TP2 (harboring pET-aroFcoli–pheAcoli–ppsA–tktA and pACYC-KDC4427–Adh4428), the de novo production of 2-PE was achieved as high as 320 mg/L after only 24 h of fermentation.

The maximum theoretical yield coefficients maxYPhe/Glc were calculated to be 0.55 g/g based on the known stoichiometry of l-Phe biosynthesis from glucose, in an engineered strain in which either the PTS was inactive or PYR was recycled back to PEP [41, 42]. Moreover, based on the hypothesis that complete conversion of all endogenously produced l-Phe to 2-PE is possible, the maximum theoretical yield (eng. maxY2-PE/Glc) was calculated to be 0.41 g/g. According to this value, E. coli BL13TP2 (320 mg/L) strains reached yields of 0.053 g/g, corresponding to 12.9% of the eng. maxY2-PE/Glc. The above data indicate that it is possible to achieve a higher yield. Major challenges may come from low enzymatic activity and flux imbalance.

Although Kdc4427 has higher enzymatic activity than ARO10, Kdc4427 is still the rate-limiting enzyme in the engineered 2-PE biosynthesis pathway because PAAL titers were observed to remain low or disappear throughout, indicating that almost all of the synthesized PAAL catalyzed by Kdc4427 was quickly converted to 2-PE by the endogenous alcohol dehydrogenase of E. coli (Fig. 4A.b). Therefore, methods to improve the activity of KDCs should be considered first. Significant achievements have been made via protein engineering, such as the combination of rational design and directed evolution [43–47]. Metabolic flow imbalance is another problem that needs to be solved to improve 2-PE production. To address this problem, rational strategies to regulate gene expression have been developed, such as the application of inducible promoters, the use of non-native RNA polymerase [46], and replacement of the ribosome binding site [47], as well as multivariate modular metabolic engineering [48]. In addition, biosensors [49, 50], modular scaffold strategies [50], and the compartmentalization of enzymes [51] have been employed to regulate metabolic flux.

Conclusions

This study obtained a phenylpyruvate decarboxylase (Kdc4427) and phenylacetaldehyde dehydrogenase (Adh4428) from Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087. Next, we introduced kdc4427 and adh4428 into E. coli BL(DE3), resulting in a 2-PE titer of 56 mg/L from glucose in shake flask cultures, which was higher than that achieved in E. coli BL(DE3) harboring Aro10 and ADH2 from S. cerevisiae (35 mg/L) under the same conditions. Then the upstream shikimate pathways genes aroF and pheA were overexpressed in the E. coli BL13 strain, which led to final 2-PE production at a titer of 258 mg/L in shake-flask fermentation, which representing a 369% improvement in 2-PE production over that achieved in the E. coli BL13 strain. Moreover, when we continued to overexpress the central metabolic pathway genes tktA and ppsA, the engineered E. coli BL13TP2 produced 320 mg/L 2-PE (Fig. 7). To the best of our knowledge, this is the highest titer of de novo 2-PE production in engineered E. coli from shake-flask cultures.

Fig. 7.

General flow chart of this study

Materials and methods

Strains, media, and reagents

All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli DH5ɑ was used as the host for DNA manipulation. E. coli BL21(DE3) was used as the host to express protein and produce 2-PE. Strains were grown routinely in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth (supplemented with suitable amounts of antibiotics if necessary). To evaluate 2-PE production in shake-flask fermentation, strains were grown in a modified M9 medium consisting of the following components: Na2HPO4, 6 g/L; KH2PO4 3 g/L; NaCl, 0.5 g/L; NH4Cl, 1 g/L; MgSO4·7H2O, 0.492 g/L; CaCl2, 0.11098 g/L; thiamine–HCl, 0.01 g/L; glucose, 15 g/L and 1 mL/L trace element solution that includes 0.37 g/L (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O, 0.29 g/L ZnSO4·7H2O, 2.47 g/L H3BO4, 0.25 g/L CuSO4·5H2O, and 1.58 g/L MnCl2·4H2O. DNA polymerase and DNA marker were purchased from TransGen Biotech (Beijing, China). Restriction enzymes and DNA ligase were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Shanghai, China).

Table 1.

Plasmids and strains used in this study

| Name | Relevant characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pETDuet-1 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7 | Novagen |

| pETDuet-KDC0498 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-kdc0498 | This work |

| pETDuet-KDC0505 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-kdc0505 | This work |

| pETDuet-KDC1244 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-kdc1244 | This work |

| pETDuet-KDC1476 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-kdc1476 | This work |

| pETDuet-KDC3074 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-kdc3074 | This work |

| pETDuet-KDC3075 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-kdc3075 | This work |

| pETDuet-KDC3076 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-kdc3076 | This work |

| pETDuet-KDC3652 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-kdc3652 | This work |

| pETDuet-KDC4427 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-kdc4427 | |

| pETDuet-KDC4472 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-kdc4472 | This work |

| pETDuet-Aro10 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-ARO10 | This work |

| pETDuet-aroFcoli–pheAcoli | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-aroFcoli–pheAcoli | Reference [37] |

| pETDuet-aroFcoli-pheA3272 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-aroFcoli-pheA3272 | This work |

| pETDuet-aroFcoli-pheA3270 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-aroFcoli-pheA3270 | This work |

| pETDuet-aroG1710-pheAcoli | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-aroG1710-pheAcoli | This work |

| pETDuet-aroG1710-pheA3272 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-aroG1710-pheA3272 | This work |

| pETDuet-aroG1710-pheA3270 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-aroG1710-pheA3270 | This work |

| pETDuet-aroH2193-pheAcoli | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-aroH2193-pheAcoli | This work |

| pETDuet-aroH2193-pheA3272 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-aroH2193-pheA3272 | This work |

| pETDuet-aroH2193-pheA3270 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-aroH2193-pheA3270 | This work |

| pETDuet-aroF3269-pheAcoli | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-aroF3269-pheAcoli | This work |

| pETDuet-aroF3269-pheA3272 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-aroF3269-pheA3272 | This work |

| pETDuet-aroF3269-pheA3270 | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-aroF3269-pheA3270 | This work |

| pTrcHis2B-AtPAL-FDC1-ppsA–tktA | pBR322 ori; Ampr; PTrc-AtPAL-FDC1-ppsA–tktA | Reference [37] |

| pETDuet-aroFcoli–pheAcoli–ppsA–tktA | ColE1(pBR322) ori; Ampr; PT7-aroFcoli–pheAcoli–ppsA–tktA | This work |

| pACYCDuet-1 | P15A origin; CmR; PT7 | Novagen |

| pACYCduet-ADH2 | P15A origin; CmR; PT7-ADH2 | This work |

| pACYCduet-adh4428 | P15A origin; CmR; PT7-adh4428 | This work |

| pACYCduet-kdc4427–adh4428 | P15A origin; CmR; PT7-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| Strains | ||

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | E. coli B dcm ompT hsdS(rB−mB−) gal | Takara |

| E. coli DH5α | deoR, recA1, endA1, hsdR17(rk−, mk+), phoA, supE44, λ−, thi−1, gyrA96, relA1 | Invitrogen |

| E. coli BL01 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-kdc0428 and pACYCDuet-ADH2 | This work |

| E. coli BL02 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-kdc0505 and pACYCDuet-ADH2 | This work |

| E. coli BL03 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-kdc1244 and pACYCDuet-Adh2 | This work |

| E. coli BL04 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-kdc1476 and pACYCDuet-ADH2 | This work |

| E. coli BL05 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-kdc3074 and pACYCDuet-ADH2 | This work |

| E. coli BL06 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-kdc3075 and pACYCDuet-ADH2 | This work |

| E. coli BL07 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-kdc3076 and pACYCDuet-Adh2 | This work |

| E. coli BL08 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-kdc3653 and pACYCDuet-ADH2 | This work |

| E. coli BL09 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-kdc4427 and pACYCDuet-ADH2 | This work |

| E. coli BL10 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-ARO10 and pACYCDuet-Adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL11 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-ARO10 and pACYCDuet-ADH2 | This work |

| E. coli BL12 | E. coli BL21(DE3) pETDuet-kdc4427 and pACYCDuet-adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13AP1 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-aroFcoli–pheAcoli and pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13AP2 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-aroFcoli–pheA3272 and harboring pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13AP3 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-aroFcoli–pheA3270 and pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13AP4 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-aroG1710-pheAcoli and pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13AP5 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-aroG1710–pheA3272 and pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13AP6 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-aroG1710–pheA3270 and pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13AP7 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-aroH2193-pheAcoli and pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13AP8 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-aroH2193–pheA3272 and pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13AP9 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-aroH2193–pheA3270 and pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13AP10 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-aroF3269–pheAcoli and pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13AP11 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-aroF3269–pheA3272 and pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13AP12 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-aroF3269–pheA3270 and pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13TP1 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-tktA–ppsA and pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli BL13TP2 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-tktA–ppsA–aroFcoli–pheAcoli and pACYCDuet-kdc4427–adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli LCQ-1 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-kdc4427 | This work |

| E. coli LCQ-2 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-ARO10 | This work |

| E. coli LCQ-3 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-adh4428 | This work |

| E. coli LCQ-4 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pETDuet-ADH2 | This work |

Genome sequencing, genome assembly, and gene prediction

Genomic DNA of Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 was extracted utilizing the E.Z.N.A. Bacterial DNA Kit (Omega, Beijing, China). The genome was sequenced using high-throughput Solexa paired-end sequencing technology at the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) (Shenzhen, China). Genomic DNA was fragmented randomly, and then DNA fragments of the required length were retained by electrophoresis. After this, we ligated adapters to the DNA fragments and conducted cluster preparation prior to sequencing. Before assembling the fragments, we used k-mer analysis to estimate the size of the genome (the assembled result was the real genome size), the degree of heterozygosity and the degree of duplication. Gene ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and Swiss-Port database were used for gene annotation.

Plasmid construction for 2-PE functional gene identification

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1 and the primers used are listed in Table 2. Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087 was used as template for cloning candidate KDC genes, the Adh gene, aroF/aroH/aroG genes and pheA genes. Aro10 from S. cerevisiae was synthesized by GenScript (Beijing, China). Adh2 from S. cerevisiae was cloned by PCR. TktA, ppsA, aroF coli, and pheA coli from E. coli BL21(DE3) were cloned by PCR. All constructed plasmids were verified by both colony PCR and Sanger sequencing.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primers | Nucleotide sequencea |

|---|---|

| pETDuet-kdc0498-F | CGCggatcctATGAATCACATGAATAAAC |

| pETDuet-kdc0498-R | CCCaagcttATGCGCTTGTAAGACC |

| pETDuet-kdc0505-F | CGCggatcctGTGGCAAAAGTGGAACCCG |

| pETDuet-kdc0505-R | cgaattcTCATGCCATCCCCTTCGC |

| pETDuet-kdc1244-F | CGCggatcctATGAAACGACTCATTGTTGG |

| pETDuet-kdc1244-R | CCCaagcttCAGGCCCCTTGCCAGCG |

| pETDuet-kdc1476-F | CGCggatcctATGAACACCTTCGACAAAC |

| pETDuet-kdc1476-R | CCCaagcttACAGGTTATCTGGAAAG |

| pETDuet-kdc3074-F | CGCggatcctATGACGGGGGCAACGGGC |

| pETDuet-kdc3074-R | CCCaagcttCAAATGCCATCTTTATTCTC |

| pETDuet-kdc3075-F | CGCggatcctATGGCATTTGATGATTTGAG |

| pETDuet-kdc3075-R | cagagctcTTATTGACGTGCTGCCAGC |

| pETDuet-kdc3076-F | CGCggatcctATGATTTGTCCACGTTGTGC |

| pETDuet-kdc3076-R | CCCaagcttACAGCAGCGGCGGGATTG |

| pETDuet-kdc3652-F | CGCggatcctATGATTAAATCATTAACGTCC |

| pETDuet-kdc3652-R | cgaattcTCAATCTGCGGAAATGGC |

| pETDuet-kdc4427-F | CGCggatcctATGCGTACCCCATACTGC |

| pETDuet-kdc4427-R | ATAAGAATgcggccgcCAGGCGCTATTGCGCGC |

| pETDuet-ARO10-F | CGCggatcctATGGCACCTGTTACAATTG |

| pETDuet-ARO10-R | cagagctCTATTTTTTATTTCTTTTAAGTG |

| pACYC-ADH2-F | catcagatctccatcaccatcatcaccacATGTCTATTCCAGAAACTC |

| pACYC-ADH2-R | cggggtaccTTATTTAGAAGTGTCAAC |

| pACYC-adh4428-F | GAagatctCATGGGTTATCAGCCGGACA |

| pACYC-adh4428-R | CCGctcgagTTATTTTGAGCTGTTCAGGATTG |

| pheA3272-F | GA agatctc ATGACACCGGAAAACCCGTTAC |

| pheA3272-R | CCGctcgag TTAGGCCGGGTCAACCG |

| pheA3270-F | GA agatctc ATGGTTGCTGAATTGACCG |

| pheA3270-R | CCGctcgag TTACTGGCGACTGTCATTTG |

| aroG1710-F | GCggatcctATGAATTATCAGAACGACGATTTACGCAT |

| aroG1710-R | ATAAGAATgcggccgcTTAGCCGCGACGCGCTTTTA |

| aroH2193-F | GCggatcctATGAATAAAACCGATGAACTCCG |

| aroH2193-R | ATAAGAATgcggccgcTTAGAAGCGAGAATCAACCG |

| aroF3269-F | GCg gat cct TTGAGGAAAACAACTATCGCA |

| aroF3269-R | ATAAGAATgcggccgc TTAAGCCAGACGCGTCG |

| ppsA–tktA-F | TCCGctcgagTTAAGGAGGTATATATTAATGTCCAACAATGGCTCGT |

| ppsA–tktA-R | TCCGcctaggTTACAGCAGTTCTTTTGCTTTCG |

Cultivation conditions and whole-cell conversion conditions

Shake-flask fermentation: A seed culture was prepared by cultivating the strain in 5 mL of LB medium with appropriate antibiotics at 37 °C and 250 rpm overnight. Then, 1 mL of the seed culture was then transferred into a 600-mL salt water bottle containing 100 mL of fermentation medium at 37 °C and 200 rpm. When the cell density reached an OD600 of 0.6–0.8, the cultures were induced with 0.4 mM of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), closed with a plug, and then incubated at 30 °C for an additional 24–48 h.

Whole-cell bioconversion: cells were collected after 6 h of culture (resulting in an OD600 of ~ 2), centrifuged at 8000×g for 5 min, washed with ice-cold PBS buffer (pH = 7.0) twice, and suspended in 10 mL PBS buffer. Finally, the appropriate substrate, PPA or PAAL, was added to the suspension at a final concentration of 1 g/L. Each suspension was then shaken at 32 °C for a total of 3 h. Samples (1 mL) were taken every hour and centrifuged, and 750 mL of supernatant was collected and filtered through 0.22-μm polyether sulfone membranes for HPLC analysis to monitor the production of either 2-PE or PAAL.

Quantification of 2-PE

After fermentation, the cultures were centrifuged at 8000×g for 1 min, and 50 ml of supernatant was extracted with 10 mL of n-heptane. Then, the extract was filtered through 0.22-μm nylon membranes and analyzed by GC–MS to qualify the biosynthesis of 2-PE. M9 medium left uninoculated and treated with the same procedures was used as the control. GC–MS analysis used a previously described procedure [8]. 2-PE production was quantified by GC, with following program: 50 °C for 1 min, which was increased at 20 °C/min to 240 °C and held for 1 min.

The concentrations of PAAL and 2-PE were measured by an HPLC (Waters 1525 series, USA) system with a 250 × 4.6 mm Bio-Rad column (California, USA), a standard 2707 autosampler (Waters, USA) and a Waters 2998 photodiode array detector (PAD) (Waters, USA). Analysis was performed at 30 °C with a mobile phase comprising 70% acetonitrile in water at a flow rate of 0.35 mL/min, and analytes were detected at OD210nm.

2-PE toxicity assay

A total of 1 mL of seed culture was transferred into a 100-mL triangular flask containing 50 mL LB medium and 2-PE at different concentrations (0, 0.5 g/L, 1.0 g/L, 1.5 g/L, or 2 g/L, respectively). The flasks were incubated at 30 °C and 200 rpm. Cell growth was determined by OD600 measurements using a UV/Vis spectrophotometer.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Protein sequences alignment of the Kdc4427 and ARO10 (ClustalX2). Figure S2. E. coli LCQ-1 and E. coli BL12 cells were cultivated, and 2-PE production titers were compared.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Candidate genes and their function prediction in this study.

Authors’ contributions

MX, HBZ, CQL conceived the original research plans; MX and HBZ supervised the project and experiments; CQL performed most of the experiments; KZ and WYC participated in shake-flask fermentation; GZ and GQC participated in gene cloning and expression; HYY performed HPLC; HBL, QW provided technical assistance to CQL; CQL wrote the manuscript; MX and HBZ supervised and complemented the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSF No. 31400084), Hainan’s Key Project of Research and Development Plan (NO. ZDYF2017155), Taishan Scholars Climbing Program of Shandong (No. TSPD20150210), and Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (No. 2017252). We thank Dr. Xinglin Jiang of Technical University of Denmark for reading the manuscript and providing many valuable comments.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mo Xian, Phone: 86-532-80662681, Email: xianmo@qibebt.ac.cn.

Haibo Zhang, Phone: 86-532-80662681, Email: zhanghb@qibebt.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Keasling JD, Chou H. Metabolic engineering delivers next-generation biofuels. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:298–299. doi: 10.1038/nbt0308-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Etschmann MM, Bluemke W, Sell D, Schrader J. Biotechnological production of 2-phenylethanol. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;59:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-0992-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamaguchi K, Ebitani K, Kaneda K. Hydrotalcite-catalyzed epoxidation of olefins using hydrogen peroxide and amide compounds. Cheminform. 2010;30:2966–2968. doi: 10.1021/jo982347e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedoukian PZ. Perfumery and flavoring synthetics. Biochem. 1967;24:5907–5918. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hua D, Xu P. Recent advances in biotechnological production of 2-phenylethanol. Biotechnol Adv. 2011;29:654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu P, Hua D, Ma C. Microbial transformation of propenylbenzenes for natural flavour production. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25:571–576. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mei J, Min H, Lü Z. Enhanced biotransformation of l -phenylalanine to 2-phenylethanol using an in situ product adsorption technique. Process Biochem. 2009;44:886–890. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2009.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang H, Cao M, Jiang X, Zou H, Wang C, Xu X, Xian M. De novo synthesis of 2-phenylethanol by Enterobacter sp. CGMCC 5087. BMC Biotechnol. 2014;14:30. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-14-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panoutsopoulos GI, Kouretas D, Gounaris EG, Beedham C. Enzymatic oxidation of 2-phenylethylamine to phenylacetic acid and 2-phenylethanol with special reference to the metabolism of its intermediate phenylacetaldehyde. Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2010;95:273–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2004.t01-1-pto950505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaminaga Y, Schnepp J, Peel G, Kish CM, Ben-Nissan G, Weiss D, Orlova I, Lavie O, Rhodes D, Wood K, Porterfield DM, Cooper AJL, Schloss JV, Pichersky E, Vainstein A, Dudareva N. Plant phenylacetaldehyde synthase is a bifunctional homotetramericenzyme that catalyzes phenylalanine decarboxylation and oxidation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23357–23366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602708200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakajima T, Kakimoto Y, Sano I. Formation of beta-phenylethylamine in mammalian tissue and its effect on motor activity in the mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 1964;143:319–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Achmon Y, Zelas BB, Fishman A. Cloning Rosa hybrid, phenylacetaldehyde synthase for the production of 2-phenylethanol in a whole cell Escherichia coli system. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:3603–3611. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5269-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim B, Cho BR, Hahn JS. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the production of 2-phenylethanol via Ehrlich pathway. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014;111:115–124. doi: 10.1002/bit.24993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen L, Nishimura Y, Matsuda F, Ishii J, Kondo A. Overexpressing enzymes of the Ehrlich pathway and deleting genes of the competing pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for increasing 2-phenylethanol production from glucose. J Biosci Bioeng. 2016;122:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2015.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hazelwood LA, Daran J-M, van Maris AJ, Pronk JT, Dickinson JR. The Ehrlich pathway for fusel alcohol production: a century of research on Saccharomyces cerevisiae metabolism. Appl Environ Microb. 2008;74:2259–2266. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02625-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fonseca GG, Heinzle E, Wittmann C, Gombert AK. The yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus and its biotechnological potential. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;79:339–354. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sluis CVD, Rahardjo YSP, Smit BA, Kroon PJ, Hartmans S, Schure EGT, Tramper J, Wijffels R. Concomitant extracellular accumulation of alpha-keto acids and higher alcohols by Zygosaccharomyces rouxii. J Biosci Bioeng. 2002;93:117–124. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(02)80002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang JY, Park J, Seo JH, Cha M, Cho BK, Kim J, Kim BG. Simultaneous synthesis of 2-phenylethanol and l-homophenylalanine using aromatic transaminase with yeast Ehrlich pathway. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;102:1323–1329. doi: 10.1002/bit.22178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Etschmann M, Schrader J. An aqueous-organic two-phase bioprocess for efficient production of the natural aroma chemicals 2-phenylethanol and 2-phenylethylacetate with yeast. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;71:440–443. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang P, Yang X, Lin B, Huang J, Tao Y. Cofactor self-sufficient whole-cell biocatalysts for the production of 2-phenylethanol. Metab Eng. 2017;44:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye L, Lv X, Yu H. Engineering microbes for isoprene production. Metab Eng. 2016;38:125–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho C, Choi SY, Luo ZW, Lee SY. Recent advances in microbial production of fuels and chemicals using tools and strategies of systems metabolic engineering. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33:1455–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atsumi S, Liao JC. Metabolic engineering for advanced biofuels production from Escherichia coli. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;19:414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atsumi S, Hanai T, Liao JC. Non-fermentative pathways for synthesis of branched-chain higher alcohols as biofuels. Nature. 2008;451:86–89. doi: 10.1038/nature06450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen X, Liu Z, Zhang J, Zhang W, Kowal P, Wang PG. Reassembled biosynthetic pathway for large-scale carbohydrate synthesis: alpha-Gal epitope producing “superbug”. ChemBioChem. 2015;3:47–53. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020104)3:1<47::AID-CBIC47>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asakawa T, Wada H, Yamano T. Enzymatic conversion of phenylpyruvate to phenylacetate. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1968;170:375. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(68)90017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barrowman MM, Fewson CA. Phenylglyoxylate decarboxylase and phenylpyruvate decarboxylase from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. Curr Microbiol. 1985;12:235–239. doi: 10.1007/BF01573337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo Z, Goswami A, Mirfakhrae KD, Patel RN. Asymmetric acyloin condensation catalyzed by phenylpyruvate decarboxylase. Tetrahedron-Asymmetry. 1999;10:4667–4675. doi: 10.1016/S0957-4166(99)00548-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boer LD, Harder W, Dijkhuizen L. Phenylalanine and tyrosine metabolism in the facultative methylotroph Nocardia sp. 239. Arch Microbiol. 1988;149:459–465. doi: 10.1007/BF00425588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider S, Mohamed ME, Fuchs G. Anaerobic metabolism of l-phenylalanine via benzoyl–CoA in the denitrifying bacterium Thauera aromatica. Arch Microbiol. 1997;168:310–320. doi: 10.1007/s002030050504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romagnoli G, Luttik MA, Kötter P, Pronk JT, Daran JM. Substrate specificity of thiamine pyrophosphate-dependent 2-oxo-acid decarboxylases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:7538. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01675-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarboe LR. YqhD: a broad-substrate range aldehyde reductase with various applications in production of biorenewable fuels and chemicals. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;89:249–257. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2912-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kneen MM, Stan R, Yep A, Tyler RP, Choedchai S, Mcleish MJ. Characterization of a thiamin diphosphate-dependent phenylpyruvate decarboxylase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Febs J. 2011;278:1842–1853. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sprenger GA. Amino acid biosynthesis ~ pathways, regulation and metabolic engineering. Berlin: Springer; 2006. Aromatic amino acids; pp. 93–127. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang C, Zhang J, Kang Z, Du G, Yu X, Wang T, Chen J. Enhanced production of l-phenylalanine in Corynebacterium glutamicum due to the introduction of Escherichia coli wild-type gene aroH. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;40:643–651. doi: 10.1007/s10295-013-1262-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Konstantinov KB, Nishio N, Seki T, Yoshida T. Physiologically motivated strategies for control of the fed-batch cultivation of recombinant Escherichia coli for phenylalanine production. J Ferment Bioeng. 1991;71:350–355. doi: 10.1016/0922-338X(91)90349-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu C, Men X, Chen H, Li M, Ding Z, Chen G, Wang F, Liu H, Wang Q, Zhu Y, Zhang H, Xian M. A systematic optimization of styrene biosynthesis in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:14. doi: 10.1186/s13068-018-1017-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serp D, Stockar UV, Marison IW. Enhancement of 2-phenylethanol productivity by Saccharomyces cerevisiae in two-phase fed-batch fermentations using solvent immobilization. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2003;82:103–110. doi: 10.1002/bit.10545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sendovski M, Nir N, Fishman A. Bioproduction of 2-phenylethanol in a biphasic ionic liquid aqueous system. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:2260–2265. doi: 10.1021/jf903879x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao F, Daugulis AJ. Polymer–solute interactions in solid–liquid two-phase partitioning bioreactors. J Chem Technol Biot. 2010;85:302–306. doi: 10.1002/jctb.2297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baez-Viveros JL, Osuna J, Hernandez-Chavez G, Soberon X, Bolivar F, Gosset G. Metabolic engineering and protein directed evolution increase the yield of l-phenylalanine synthesized from glucose in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;87:516–524. doi: 10.1002/bit.20159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patnaik R, Liao JC. Engineering of Escherichia coli central metabolism for aromatic metabolite production with near theoretical yield. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3903–3908. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.11.3903-3908.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eriksen DT, Lian J, Zhao H. Protein design for pathway engineering. J Struct Biol. 2014;185:234–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quin MB, Schmidtdannert C. Engineering of biocatalysts: from evolution to creation. Acs Catal. 2011;1:1017. doi: 10.1021/cs200217t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Röthlisberger D, Khersonsky O, Wollacott AM, Jiang L, Dechancie J, Betker J, Gallaher JL, Althoff EA, Zanghellini A, Dym O. Kemp elimination catalysts by computational enzyme design. Nature. 2008;453:190–195. doi: 10.1038/nature06879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mutka SC, Carney JR, Yaoquan Liu A, Kennedy J. Heterologous production of epothilone C and D in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1321–1330. doi: 10.1021/bi052075r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salis HM, Mirsky EA, Voigt CA. Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:946. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yadav VG, De MM, Lim CG, Ajikumar PK, Stephanopoulos G. The future of metabolic engineering and synthetic biology: towards a systematic practice. Metab Eng. 2012;14:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dahl RH, Zhang F, Alonso-Gutierrez J, Baidoo E, Batth TS, Redding-Johanson AM, Petzold CJ, Mukhopadhyay A, Lee TS, Adams PD, Keasling JD. Engineering dynamic pathway regulation using stress-response promoters. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:1039–1046. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dueber JE, Wu GC, Malmirchegini GR, Moon TS, Petzold CJ, Ullal AV, Prather KL, Keasling JD. Synthetic protein scaffolds provide modular control over metabolic flux. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:753–759. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee H, DeLoache WC, Dueber JE. Spatial organization of enzymes for metabolic engineering. Metab Eng. 2012;14:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Protein sequences alignment of the Kdc4427 and ARO10 (ClustalX2). Figure S2. E. coli LCQ-1 and E. coli BL12 cells were cultivated, and 2-PE production titers were compared.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Candidate genes and their function prediction in this study.