Abstract

Purpose:

We sought to examine how ambivalence manifests in women’s lives after confirmation of a new pregnancy by exploring women’s feelings, attitudes, and experiences regarding pregnancy intentions, the news itself, and related pregnancy decision making.

Study Design:

We recruited women aged 15 to 44 and at less than 24 completed weeks of gestational age from urban, walk-in pregnancy testing clinics in New Haven, Connecticut, from June 2014 to June 2015. We obtained quantitative and qualitative data via an enrollment survey and face-to-face, semistructured interviews, respectively. Transcripts were analyzed using framework analysis.

Results:

The sample included 84 women. Participants had a mean age of 26 years and were on average 7 weeks estimated gestational age at enrollment. Most identified as Black (54%) or Hispanic (20%), were unmarried (92%), and had at least one other child (67%). More than one-half (55%) described feelings of ambivalence regarding their current pregnancy. We identified ambivalence as a frequent and complex thread that represented distinct but overlapping perspectives about pregnancy: ambivalent pregnancy intentions, ambivalent response to new diagnosis of pregnancy, and ambivalence as uncertainty or conflict over pregnancy decision-making. Sources of ambivalence included relationship status, pregnancy timing, and maternal or fetal health problems.

Conclusions:

This study improves on previous findings that focus only on ambivalence related to pregnancy intention or to decision making, and explores women’s mixed, fluctuating, or unresolved feelings and attitudes about pregnancy before many participants had completed pregnancy decision making. Acknowledging and exploring sources of ambivalence regarding pregnancy may help health providers and policymakers to comprehensively support women with respect to both their experiences and reproductive goals.

Ambivalence about pregnancy is often defined as “unresolved or contradictory feelings about whether one wants to have a child at a particular moment” (Higgins, Popkin & Santelli, 2012). Pregnancy ambivalence is an independent risk factor for high-risk sexual behavior, inconsistent or no contraceptive use, unintended pregnancy, and antepartum risk behaviors (Miller & Jones, 2010), such as increased incidence of smoking and alcohol use (Mercier, Garrett, Thorp & Siega-Riz, 2013). Ambivalence is associated with poor pregnancy outcomes, such as an increased likelihood of premature rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, and delivering a low birth weight infant (Gipson, Koenig & Hindin, 2008; Mohllajee, Curtis, Morrow & Marchbanks, 2007). For these reasons, pregnancy ambivalence has been identified as a potential distinct risk factor for pregnancy-related complications, but research suggests that a more comprehensive understanding of pregnancy-related ambivalence is necessary if we are to offer effective interventions (Hellerstedt et al., 1998).

Current descriptions of pregnancy ambivalence are limited by retrospective assessments that elicit perspectives on pregnancy after completed or terminated pregnancies and, therefore, may be subject to recall bias (Askelson, Losch, Thomas & Reynolds, 2015; Kavanaugh & Schwarz, 2009; Santelli et al., 2003), inconsistent or narrowly defined definitions (Higgins et al., 2012), and reliance on oversimplified dichotomous measurements (e.g., intended or unintended pregnancy categories; Aiken, Borrero, Callegari & Dehlendorf, 2017; Borrero et al., 2015). For example, researchers have classified heterosexually active women who do not intend to become pregnant but are not using contraception as ambivalent (Zabin, 1999). Such characterizations do not account for women who have other reasons for avoiding contraception, such as religious dictums, concerns over potential side effects, or intended abstinence, which might obviate a perceived need for contraception. Recent qualitative studies reveal that researchers’ and clinicians’ assignment of the term “ambivalence” may be inaccurate. For instance, Aiken, Dillaway, and Mevs-Korff (2015) reported that women express happiness at the idea of pregnancy while simultaneously and earnestly trying to prevent conception. These researchers noted that the concepts of intentions and happiness can be distinct, are not mutually exclusive, and propose that characterizing these women as ambivalent may inadvertently obscure women’s intentions and desires for contraceptiondin both the clinical and research settings. For example, a healthcare provider may inaccurately assume that women who express happiness at the prospect of a pregnancy must not want contraception and may withhold contraceptive counseling from women who indeed want and need it. Conversely, women who have unprotected intercourse cannot be assumed to be happy about a new pregnancy.

Finally, there is a knowledge gap about pregnancy ambivalence as it applies to different time points. Current descriptions of pregnancy ambivalence are almost exclusively focused on ambivalence regarding contraceptive use and nonuse (Crosby et al., 2002; Frost & Darroch, 2008; Higgins et al., 2012; Schwarz, Lohr, Gold & Gerbert, 2007; Yoo, Guzzo & Hayford, 2014) and pregnancy intention, planning, and desire (Borrero et al., 2015; McQuillan, Greil & Shreffler, 2011; Miller, Barber & Gatny, 2013). Less is known about ambivalence after a pregnancy diagnosis or pregnancy decision making (abortion, adoption, parenthood; Miller, 1994; Wikman, Jacobsson, Joelsson & von Schoultz, 1993).

In this paper, we address the concept of ambivalence as it relates to confirmation of a new pregnancy among a diverse cohort of pregnant women. We explored women’s attitudes, feelings, and experiences about ambivalence related to pregnancy intentions, the confirmation of the pregnancy itself, and subsequent pregnancy decision making.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a qualitative study to explore the impact of a new pregnancy on women’s lives. We recruited women who presented for pregnancy testing at two clinical sites in New Haven, Connecticut, from June 2014 to June 2015. Clinical staff referred interested women with positive pregnancy tests to the research team. Research staff screened interested women for eligibility and offered study participation to all eligible women. Women were eligible if they were Spanish or English speaking, at less than 24 completed weeks of gestational age, 15 to 44 years of age, and completed study enrollment within 1 week of their positive pregnancy test. Of 271 women with a positive pregnancy test, 225 were interested and screened regarding study participation, and 46 were uninterested or left before speaking with research staff. After screening, 152 were eligible and interested in participating. Twenty-six were unable to stay for enrollment or were lost to follow-up within 1 week of contact; thus, 126 women were ultimately enrolled. Two individuals enrolled with an initial positive pregnancy test were later determined to have had a false-positive test. One individual consented to study participation, but did not complete the enrollment survey. Of the 123 remaining study participants, 85 completed the quantitative portion of the study during enrollment in English, and within this group 1 individual did not complete the qualitative interview. Thus, this analysis includes the 84 English-language interviews; women who chose to participate in Spanish will be analyzed separately to ensure cross-language credibility (Squires, 2009). Participant demographics (including age, race/ethnicity, relationship status), measures of pregnancy intention, and plans for pregnancy were assessed in the enrollment survey. Specifically, with respect to pregnancy intention, the enrollment survey included the following questions: “Just before I became pregnant.a) I intended to get pregnant, b) My intentions kept changing, or c) I did not intend to get pregnant; Just before I became pregnant. a) I wanted to have a baby, b) I had mixed feelings about having a baby, or c) I did not want to have a baby” (Gariepy et al., 2017). The Yale University Human Research Protection Program reviewed and approved the study protocol.

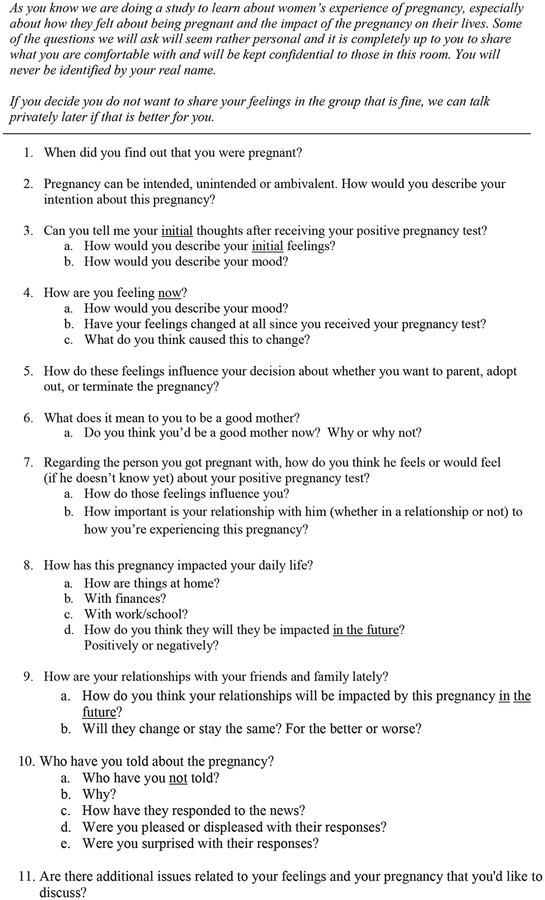

Eligible women were offered the option of participating in a one-on-one interview or a focus group. (A total of four women preferred to be interviewed in focus groups, which occurred as two groups of two women each.) Interviews were audio recorded and facilitated by one of three interviewers who used a semistructured guide (Figure 1) to explore women’s pregnancy intention and initial reaction to learning about the pregnancy, and to follow up on feelings about the impact of the new pregnancy on their lives and decisions. Of note, two interviewers were White/Hispanic women and one interviewer was a White/non-Hispanic woman; two were bilingual in English and Spanish. Audio files were transcribed. Each woman’s interview was read in its entirety to understand the comprehensive narrative. A systematic coding structure was developed using framework analysis to identify key concepts and specific domains (Gale, Heath, Cameron & Rashid, 2013). This process was used to identify both commonalities and differences in qualitative data, as well as any relationships among the data that could describe or explain the themes that emerged. We developed a shared coding strategy, created a list of specific codes to flag key concepts and the context in which they occurred, and then approved a final code list as a group. To assess intercoder reliability, four coders initially analyzed and coded the same six interviews and then met as a group to discuss major themes and reconcile any coding discrepancies. After reaching consensus on a final code list, two independent coders then coded the remaining transcripts. Atlas.ti (Berlin, Germany) software was used to organize, code, and analyze all transcripts.

Figure 1.

Focus group and individual interview guide.

The topic of ambivalence was identified from the data and served as an ex post facto analysis. Although only one interview question directly asked about ambivalence as related to perceived pregnancy intention (“Pregnancy can be intended, unintended or ambivalent. How would you describe your intention about this pregnancy?”), many women raised issues related to ambivalence over the course of the interview and this information was analyzed as well. For example, women described ambivalence in response to general questions about their immediate reactions to their positive pregnancy tests, the evolution of their thoughts and feelings since their positive pregnancy tests, the impact of sharing their news with others, and whether their feelings were influencing their decisions to pursue parenthood, adoption, or abortion.

Results

Participants averaged 26 years of age and 7 weeks estimated gestational age at enrollment. Most identified as Black, non-Hispanic (54%) or Hispanic (20%). The majority (92%) were unmarried (of whom 23% were living with a partner and 18% were divorced or separated) and 67% had at least one other child. When asked in the survey about the time just before becoming pregnant, 61% indicated they did not intend to get pregnant and 19% indicated their intentions kept changing. At enrollment, 65% planned to parent, 19% planned abortion, 2% planned adoption, and 14% were unsure.

During their interviews, 46 women (55% of the sample) described feelings of ambivalence in response to questions about their pregnancy intentions, response to confirmation of a new pregnancy, or decision making about the pregnancy. These feelings were often interconnected and often conflicting. Women cited many reasons for their ambivalence, including shock, relationship status, and availability of resources to care for children.

Distinct but overlapping categories of pregnancy-related ambivalence emerged and will be discussed in depth—ambivalent pregnancy intention, ambivalent response to new pregnancy, and ambivalence as uncertainty over pregnancy decision making—as well as sources of ambivalence.

Ambivalent Pregnancy Intentions

In response to a question that asked women to characterize their pregnancy as intentional, unintentional, or ambivalent, many women described their pregnancies as ambivalent perhaps only for lack of a better word: “It wasn’t intended and it wasn’t unintended, so that third one [ambivalent] is the best answer for me.”

In keeping with findings from prior studies (Aiken et al., 2015), women illustrated that lack or inconsistent use of birth control did not uniformly align with their concept of intention:

Um I was protecting myself but not really since I’ve been with my partner, we’ve been going on 3 years now, so kinda using when we want, not using when we don’t. So, kinda seen it comin’ but it really wasn’t, like, I wasn’t gunning to get pregnant.

Some women cited the role of fate and divine intervention, rendering the concept of intention somewhat meaningless or inapplicable:

God planned everything and this being a blessing…. And if it’s meant, it’s meant and if it’s not, it’s not. So it must have been meant so that’s why I’m trying to take it as best that I can, be happy about it. Cuz it was meant, children are always blessings.

Ambivalent Response to New Pregnancy

When asked what they immediately felt after being told they were pregnant, women reported a range of feelings, including happy, sad, scared, worried, mad and, commonly, surprised or shocked. Many expressed seemingly contradictory feelings (e.g., happy and sad) or more mixed emotions such as “feeling in the middle”:

“I’m not that excited and I’m not like that sad. I’m like in the middle. so, like in the middle of happy and sad.”

Some women reflected that their pregnancy intention didn’t necessarily match their current attitudes about being pregnant:

I think it was intended but now that it’s happened, it’s kind of …uhhh, OK. (laughs) We’ll sit down and talk and decide what we’ll do from here on out.

It’s just… it was exciting but… it was like sad at the same time. Only because it wasn’t… really planned. Nothing was planned. I didn’t want to be pregnant.

It wasn’t planned but we knew basically… I was having baby fever. And then when it happened, I was like, uh, I don’t think this is the right time.

Many women expressed uncertainty upon learning they were pregnant, which may represent unresolved or evolving feelings: “I don’t know. I just don’t know. I really don’t have all my thoughts together on it right now, like I said my feelings are like scattered at this point.” The idea of not knowing how to feel or react was also very common among women; some were fatalistic:

I didn’t know what to think, I just cry (laughs)…. I didn’t know how to react. I just cry. It was like I don’t know how to answer what am I gonna do, how to feel about this? I didn’t know whether to be upset or happy, but now after I thought about it I mean I’m kinda happy. I mean everything happens for a reason.

Ambivalence as Uncertainty over Pregnancy Decision Making

Many women expressed ambivalence regarding what to do about the pregnancy and described uncertainty over the decision to parent, adopt, or terminate. Women explicitly described decisional conflict:

I don’t know if I want to get rid of it or keep it… I, right now I just don’t know what to think. Because I don’t know what I’m going to do.

I kinda want to [parent] but then I kinda don’t want to. I want to but then I don’t want to.

Women’s decisions to have or to not have another child were deeply rooted in their sense of themselves as good mothers, often defined in relation to existing children who required their time, attention, love, and resources:

I don’t want to bring another child into this world. I still be living with my grandmother, you know, my daughter she’s 6 and, you know, she’s at an age where she’s “Oh, mommy,” she wants to live on our own, she wants her own room. So it kinda does, it kinda somewhat does make me think that you know maybe you aren’t ready for another one. But I feel like I am, because I feel like I shouldn’t get rid of my baby if I want it.

Um, like I said, um, just, I have a son that’s 3, he’s special …it’d probably be different if he wasn’t special needs and my life was not as complicated and it was like a regular um thing but I’ve just gotten some good space. His health has finally gotten some good space. So we’re finally OK. So I don’t know if um is it fair to bring another child in at this time?

I don’t know like last night I cried, its more of like I don’t know, you know like I don’t know where I’m gonna go from here, I know I just want to keep it… so I feel all kind of ways, like I’m a happy feeling then it’s a sad feeling then its you know, just all the emotions at once like I can’t really… because I do go through a lot with the three children I have.… Like, how am I gonna kinda deal with this like I have a son who has asthma, have an older son who has behavioral problems… how am I gonna balance all this with a new baby?

Women often cited other contributory factors such as beliefs about abortion, potential impact on their future goals, and lack of financial or relationship stability.

I know [my partner’s] happy and I guess deep inside of me I’m happy about it, too, but I’m so scared that I… I don’t want it. Not that I don’t want it, but… I guess having it would make me feel better about myself but I know it’s not the right time for me. I’m still trying to finish school. And I don’t have like my own house with [my partner] or stuff like that so there’s no point.

I have like a thousand thoughts running through my mind, like uh you know, how are my parents gonna take it? Am I ready to bring another child into this world? Cause I am living on my own, I am sleeping on a couch, so it’s like I’m still like kinda yes and no about it, you know, ‘cause I want to be stable.

I would never give my child up for adoption. As far as abortion, I’m not against it, but I have a lot to consider right now. I got a lot going on, on my plate so I really have to weigh my options cuz my personal life is not where I want it to be, and financially I’m not where I would like to be. So it’s a lot of things I have to take into consideration besides my own feelings and, you know, everything else.

Sources of Ambivalence

When expressing pregnancy-related ambivalence, women cited various sources, including prior fertility and pregnancy experiences, current children, relationship status, social support, maternal–fetal health, and the pregnancy’s potential impact on a woman’s relationships and finances. Participants voiced concerns about how this pregnancy would realistically fit into their current lives and impact their current goals and dreams. Many women expressed that they did not feel ready to have another child or be a mother and regretted that the timing was not different. Others expressed that the prospect of an additional child was at odds with their ideal family composition or size, leading them to feel ambivalent about a new pregnancy diagnosis:

I was on the fence about it, I wasn’t sure about it being that I have two kids already. Just, my oldest daughter is 10 and then my youngest daughter is 6, just about starting over again. So I was a little nervous about that part.… I didn’t try to get pregnant, so I guess it was unintended.

Women discussed how having a (or another) child would realistically fit into their current lives, especially if they felt they lacked relationship or financial stability, and how having a child would impact their goals and dreams:

I feel like I’m young and I still wanna accomplish things in my life that I haven’t accomplished. And I wanna be able to, when I have a kid in the future, I wanna be able to give my kid something I didn’t have. So just wanna make sure like if I do have a kid I’m with the right person and you know, we have a stable home and… you know just everything I didn’t have.… I would prefer for me to be in school now and you know to be working and have a career instead of having a job and having a kid.

It’s bad timing, it’s really bad timing. I wish this was like next year and I was like in my apartment already, and me and my boyfriend been together for a while and we both are stable, then I would definitely you know reconsider. But… right now it’s just like I’m trying to move up. I’m not trying or move down or move backwards, I’m trying to move forward and this is just gonna put a halt in everything.

Discussion

A new pregnancy can have a substantial impact on diverse aspects of women’s lives. Our findings suggest that expressions of ambivalence about pregnancy occur at different time points, including prepregnancy intentions, the confirmation of the pregnancy itself, and subsequent pregnancy decision making. Ambivalence after a pregnancy diagnosis may be common and should be considered in the ongoing work to understand women’s experiences and feelings about pregnancy from a patient-centered perspective. Additionally, our findings support prior studies that question standard mutually exclusive binary assessments of pregnancy (e.g., intended vs. unintended; wanted vs. unwanted) (Borrero et al., 2015; Aiken et al., 2016).

This study furthers understanding of pregnancy-related ambivalence in several respects. By capturing women’s thoughts shortly after receiving their positive pregnancy tests, and prospective to pregnancy resolution (spontaneous or induced abortion, birth) our study improves on previous studies that assessed ambivalence only retrospectively, which may be limited by recall and selection bias (Gerber, Pennylegion, Spice & Plough, 2002; Higgins et al., 2012; Kavanaugh & Schwarz, 2009; Kennedy, Grewal, Roberts & Steinauer, 2014). Unlike previous studies limited to women seeking abortion (Biggs, Gould & Foster, 2013; Kirkman, Rowe, Hardiman & Mallett, 2009; Husfeldt, Hansen, Lyngberg & Nøddebo, 1995), our examination of ambivalence in pregnancy includes women who stated in their interviews that they unequivocally planned to parent and women who stated they unequivocally planned to terminate, as well as women who expressed ambivalence about pregnancy decision making. Our study addresses a gap in the literature on both of these topics. Study participants also reflect diversity in race, relationship status, parity, and pregnancy intention, which is an additional strength of this study. Finally, our study identifies and more completely defines and describes ambivalence through women’s own words, which is an important contribution to the existing literature, especially in light of recent calls for more women-centered strategies to be incorporated into reproductive life planning counseling (Aiken et al., 2016).

Our study may be limited by social desirability bias (Stuart & Grimes, 2009). Although interviewers underwent specific training to encourage open dialogue, women’s responses may reflect what they believe interviewers wanted to hear, as opposed to their true feelings. This may matter particularly in a society such as ours where women may feel pressured to be mothers and to view pregnancy as unequivocally positive, and abortion and adoption as less so (Astbury-Ward & Parry, 2012; Ridgeway & Correll, 2004). Our data are affected by cross-racial interviewing (e.g., White/non-Hispanic or White/Hispanic interviewer and Black interviewee), which could bias the interactions between participants and interviewers (Rhodes, 1994; Sands, Bourjolly & Roer-Strier, 2007). Additionally, although the concept of ambivalence emerged as common in our interviews on feelings about a new pregnancy, ambivalence was not the focus of the study. A directed qualitative exploration of concepts related to ambivalence could yield further insights regarding ambivalence in pregnancy. It is also worth noting that our assessment of prepregnancy perspectives (e.g., pregnancy intention) was measured in women who were already (if newly) pregnant. Although a limitation, our assessment does improve on conventional measures of pregnancy intention and planning, which traditionally have been assessed after birth, sometimes up to 5 years postpartum (Mumford, Sapra, King, Louis, & Buck Louis, 2016; Santelli, Lindberg, Orr, Finer, & Speizer, 2009). The study may be limited by a sample comprising primarily unmarried women (92%), and findings may differ among a group of married women; the study may also be limited by selection bias because some eligible women may have chosen not to participate. Finally, although data from our two focus groups are not fully comparable units of analysis to data from our interviews, a review of the data did not reveal significant differences in the themes elicited between the two types of data collection, so both focus group and interview data are reported.

Understanding and defining ambivalence about pregnancy from women’s perspectives is critical, especially given the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ proposal to use One Key Question (OKQ)—”Would you like to become pregnant in the next year?”—as a tool to help women consider and identify their reproductive goals as well as to identify women at risk for unintended pregnancy (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, 2016, One Key Question). Although the framework for OKQ does allow for ambivalent responses (e.g., “I’m OK either way” or “I’m not sure”), its focus remains on prepregnancy intentions, desires, and feelings. The question loses applicability once a woman becomes pregnant, at which point prepregnancy intentions, desires, and feelings—to say nothing of life circumstances and relationships—may change or cease to be relevant. For example, among low-income African American and White women, “decisions about the acceptability of a pregnancy are often determined after the pregnancy has already occurred” (Borrero et al., 2015). As time elapses between contemplating a pregnancy, becoming pregnant, and making decisions about pregnancy management, changes in partner relationships, financial instability, or deteriorating health can affect how women experience and contextualize their pregnancy (Gariepy et al., 2017). Furthermore, for women who have ambivalent feelings about pregnancy, their answers to OKQ may well vary month to month, day to day, or even minute to minute.

Pregnancy-related ambivalence may reflect the irrelevance of “pregnancy planning” for some women (Borrero et al., 2015), a woman’s difficult adjustment to the significant life event that pregnancy confers, or simply a more realistic and honest perspective about pregnancy and the decision making it requires. Expressions of ambivalence may signal the presence of internal or external conflicts; in our cohort, several women expressed positive feelings about the pregnancy, but had serious concerns about how they were going to financially support a (nother) baby without additional help. Others expressed negative feelings about the pregnancy, but felt pressure to accept it as a blessing or fate, similar to findings by Borrero et al. (2015), Aiken et al. (2015), Jones, Frohwirth, and Blades (2016). Comprehensive options counseling is a patient-centered intervention that addresses the possibility of ambivalence regarding pregnancy continuation or decision making but, for obvious reasons, is usually conducted early in a pregnancy timeline (Perrucci, 2012). Furthermore, data on the topic of options counseling is limited (Singer, 2004). Future research is needed to improve on current reproductive life planning frameworks to include women who hold ambivalent feelings about being pregnant (Callegari et al., 2017).

Aiken et al. (2016) have recently called for more women-centered strategies to be incorporated into reproductive health planning counseling, and have proposed a new conceptual model that acknowledges ambivalence as part of an effort to more comprehensively support individual women and their reproductive goals. Pointing out the nonspecificity and irrelevance of conventional planning paradigms for many women, the authors propose that emotional orientations (which offer indications of the psychosocial stress that might accompany a new pregnancy and thus, for instance, contribute to ambivalence) may be more important than timing-based orientations (dichotomous concepts such as intention, timing, and wantedness) in predicting negative maternal and fetal outcomes (Blake et al., 2007; Sable et al., 1997). For instance, it is conceivable that a woman who is unhappy (emotional orientation) about a planned (timing-based orientation) pregnancy may be at greater risk of negative pregnancy-related outcomes than a woman who is happy about an unplanned pregnancy. Future research to assess whether ambivalence (of any type, at any time) is associated with poor maternal and fetal outcomes (including delayed entry to care for abortion or prenatal services) warrants further investigation.

Implications for Policy and/or Practice

Screening questions that focus on planning or intention may not adequately identify women who will experience ambivalence during a pregnancy. Acknowledging and exploring sources of ambivalence regarding pregnancy may help health providers and policymakers to comprehensively support women with respect to both their experiences and their reproductive goals.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that, to support and assist women in their reproductive lives, we need to be mindful of ambivalence in all its forms and at various time points—not just before pregnancy, but also during pregnancy. Health care providers should be aware that many women hold ambivalent views about both theoretical and actual pregnancy, and they should not assume that expressions of ambivalence mean that women are necessarily unhappy about their pregnancies or planning to terminate. It may mean, however, that women who express ambivalence about pregnancy are more likely to be grappling with decision making and life circumstances that, although common, are complex and thus warrant close attention and individual support.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: Dr. Gariepy was supported by funding from National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Awards (NIH CTSA) UL1 TR000142 and the Albert McKern Scholar Awards for Perinatal Research, which also supported Dr. Lundsberg, during the conduct of the study. Funding sources had no involvement in the study or manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Gariepy reports grants from NIH CTSA UL1 TR000142, which also supported Dr. Lundsberg, during the conduct of the study. All other authors report no competing financial interests exist.

Academic appointment as of September 1, 2017.

References

- Aiken ARA, Dillaway C, & Mevs-Korff N (2015). A blessing I can’t afford: Factors underlying the paradox of happiness about unintended pregnancy. Social Science & Medicine, 132, 149–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken ARA, Borrero S, Callegari LS, & Dehlendorf C (2016). Rethinking the pregnancy planning paradigm: Unintended conceptions or unrepresentative concepts? Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 48(3), 147–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. (2016). Committee Opinion No. 654: Reproductive Life Planning to Reduce Unintended Pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 127(2), e66–e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askelson NM, Losch ME, Thomas LJ, & Reynolds JC (2015). “Baby? Baby not?”: Exploring women’s narratives about ambivalence towards an unintended pregnancy. Women & Health, 55(7), 842–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astbury-Ward E, & Parry O (2012). Stigma, abortion, and disclosuredFindings from a qualitative study. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(12), 3137–31347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs MA, Gould H, & Foster DG (2013). Understanding why women seek abortions in the US. BMC Women’s Health, 13, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake SM, Kiely M, Gard CC, El-Mohandes AAE, El-Khorazaty MN, & NIH-DC Initiative. (2007). Pregnancy intentions and happiness among pregnant black women at high risk for adverse infant health outcomes. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 39(4), 194–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrero S, Nikolajski C, Steinberg JR, Freedman L, Akers AY, Ibrahim S, & Schwarz EB (2015). “It just happens”: A qualitative study exploring low-income women’s perspectives on pregnancy intention and planning. Contraception, 91(2), 150–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callegari LS, Aiken ARA, Dehlendorf C, Cason P, & Borrero S (2017). Addressing potential pitfalls of reproductive life planning with patient-centered counseling. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 216, 129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby RA, Diclemente RJ, Wingood GM, Davies SL, & Harrington K (2002). Adolescents’ ambivalence about becoming pregnant predicts infrequent contraceptive use: A prospective analysis of nonpregnant African American females. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 186(2), 251–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost JJ, & Darroch JE (2008). Factors associated with contraceptive choice and inconsistent method use, United States, 2004. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 40(2), 94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, & Redwood S (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13, 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gariepy A, Lundsberg LS, Vilardo N, Stanwood N, Yonkers K, & Schwarz EB (2017). Pregnancy context and women’s health-related quality of life. Contraception, 95(5), 491–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber A, Pennylegion M, Spice C, & Plough AP (2002). If it happens, it happens: A qualitative study of unintended pregnancy among low income women living in king county. Seattle and King County, WA: Family Planning Program. [Google Scholar]

- Gipson JD, Koenig MA, & Hindin MJ (2008). The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: A review of the literature. Studies in Family Planning, 39(1), 18–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellerstedt WL, Pirie PL, Lando HA, Curry SJ, McBride CM, Grothaus LC, & Nelson JC (1998). Differences in preconceptional and prenatal behaviors in women with intended and unintended pregnancies. American Journal of Public Health, 88(4), 663–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JA, Popkin RA, & Santelli JS (2012). Pregnancy ambivalence and contraceptive use among young adults in the United States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 44(4), 236–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husfeldt C, Hansen SK, Lyngberg A, Nøddebo M, & Petersson B (1995). Ambivalence among women applying for abortion. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 74(10), 813–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RK, Frohwirth LF, & Blades NM (2016). “If I know I am on the pill and I get pregnant, it’s an act of God”: Women’s views on fatalism, agency and pregnancy. Contraception, 93(6), 551–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh ML, & Schwarz EB (2009). Prospective assessment of pregnancy intentions using a single-versus a multi-item measure. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 41(4), 238–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, Grewal M, Roberts EM, Steinauer J, & Dehlendorf C (2014). A qualitative study of pregnancy intention and the use of contraception among homeless women with children. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 25(2), 757–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkman M, Rowe H, Hardiman A, Mallett S, & Rosenthal D (2009). Reasons women give for abortion: A review of the literature. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 12(6), 365–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan J, Greil AL, & Shreffler KM (2011). Pregnancy intentions among women who do not try: Focusing on women who are okay either way. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15(2), 178–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier RJ, Garrett J, Thorp J, & Siega-Riz AM (2013). Pregnancy intention and postpartum depression: Secondary data analysis from a prospective cohort. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 120(9), 1116–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WB (1994). Reproductive decisions: How we make them and how they make us. Advances in Population: Psychosocial Perspectives, 2, 1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WB, & Jones J (2010). The effects of preconception desires and intentions on pregnancy wantedness. Journal of Population Research, 26(4), 327–357. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WB, Barber JS, & Gatny HH (2013). The effects of ambivalent fertility desires on pregnancy risk in young women in the USA. Population Studies, 67(1), 25–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohllajee AP, Curtis KM, Morrow B, & Marchbanks PA (2007). Pregnancy intention and its relationship to birth and maternal outcomes. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 109(3), 678–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumford SL, Sapra KJ, King RB, Louis JF, & Buck Louis GM (2016). Pregnancy intentions: A complex construct and call for new measures. Fertility and Sterility, 106(6), 1453–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- One Key Question, Available at: http://www.onekeyquestion.org/. Accessed: November 1, 2016.

- Perrucci AC (2012). Decision assessment and counseling in abortion care: Philosophy and practice. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes PJ (1994). Race-of-interviewer effects: A brief comment. Sociology,28(2), 547–558. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway CL, & Correll SJ (2004). Motherhood as a status characteristic.Journal of Social Issues, 60(4), 683–700. [Google Scholar]

- Sable MR, Spencer JC, Stockbauer JW, Schramm WF, Howell V, & Herman AA (1997). Pregnancy wantedness and adverse pregnancy outcomes: Differences by race and Medicaid status. Family Planning Perspectives, 29(2), 76–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands RG, Bourjolly J, & Roer-Strier D (2007). Crossing cultural barriers in research interviewing. Qualitative Social Work, 6(3), 353–372. [Google Scholar]

- Santelli J, Rochat R, Hatfield-Timajchy K, Gilbert BC, Curtis K, Cabral R, … Unintended Pregnancy Working Group (2003). The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35(2), 94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Lindberg LD, Orr MG, Finer LB, & Speizer I (2009). Toward a multidimensional measure of pregnancy intentions: Evidence from the United States. Studies in Family Planning, 40(2), 87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz EB, Lohr PA, Gold MA, & Gerbert B (2007). Prevalence and correlates of ambivalence towards pregnancy among nonpregnant women. Contraception, 75(4), 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer J (2004). Options counseling: Techniques for caring for women with unintended pregnancies. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 49(3), 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires A (2009). Methodological challenges in cross-language qualitative research: A research review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(2), 277–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GS, & Grimes DA (2009). Social desirability bias in family planning studies: A neglected problem. Contraception, 80(2), 108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikman M, Jacobsson L, Joelsson I, & von Schoultz B (1993). Ambivalence towards parenthood among pregnant women and their men. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 72(8), 619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Guzzo KB, & Hayford SR (2014). Understanding the complexity of ambivalence toward pregnancy: Does it predict inconsistent use of contraception? Biodemography and Social Biology, 60(1), 49–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabin LS (1999). Ambivalent feelings about parenthood may lead to inconsistent contraceptive use–and pregnancy. Family Planning Perspectives, 31(5), 250–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]