Abstract

Objective:

To assess the influence of endorectal filling (EF) on rectal cancer staging.

Methods:

47 patients who underwent a staging MRI of rectal cancer in the period from 2011 to 2014 were included. The MRI protocol included T2 weighted fast spin echo sequences without and with EF at 3 T (EF-MRI). Images were scored by two readers for T-stage, distance of the lower pole of the tumour to the anorectal junction, distance to the mesorectal fascia (MRF), and number of (suspicious) lymph nodes. Agreement in T-staging was calculated using the Cohen’s κ value. Comparison of continuous variables was performed using Wilcoxon matched pairs signed-rank test.

Results:

The interobserver agreement for T-staging with and without EF-MRI showed a poor agreement between both readers (weighted κ = 0.156, weighted κ = 0.037, respectively). Tumours tended to be overstaged more prominently with EF-MRI. The accuracy of predicting the pathological T-stage slightly improved from 55% with EF to 64% without EF for Reader 1 and from 59 to 68% for Reader 2, respectively. The distance of the tumour to the anorectal junction increased from 33.9 to 49.3 mm (p < 0.001) after EF for Reader 2. EF-MRI did not significantly influence the number of (suspicious) lymph nodes and distance to the mesorectal fascia.

Conclusion:

EF-MRI did not lead to an improved tumour staging and it has the potential to influence the distance to a key anatomical landmark. EF-MRI is therefore not recommended in primary staging rectal cancer.

Advances in knowledge:

EF-MRI may not be used as an additional tool to stage rectal cancer patients, as it does not seem to facilitate in locoregionally staging the disease.

Introduction

In rectal cancer, the treatment of choice is surgical resection of the primary tumour according to the principle of total mesorectal excision (TME).1 Tumour bulkiness, the presence of lymph nodes, EMVI and “threatened/involved” mesorectal fascia (MRF) are well-known risk factors for local recurrence and distant spread of the disease.2, 3 The role of MRI in the primary work-up of rectal cancer is well established and by identifying these risk factors with non-invasive imaging, MRI stratifies locally advanced rectal cancer into a preoperative treatment.4

The recently published revision of the ESGAR rectal cancer consensus guidelines dictates that a state-of-the-art MR protocol should consist of high resolution T2 weighted (T2W) fast spin echo (FSE) sequences in three planes, sagittal, coronal and axial. The axial planes should be perpendicular to the tumour axis to allow for accurate assessment of the extension of tumour outside the bowel wall within the mesorectal fat and accurate measurement of the shortest distance between the tumour and MRF. The T2W FSE sequences should include the entire mesorectum from promontorium level to pelvic floor including the anal sphincter complex, to allow for accurate assessment of the nodes. That is to evaluate the total number of lymph nodes and the number of suspicious lymph nodes. Although there is general consensus on the recommended MR sequences and planes, there is no consensus regarding the use of endorectal filling (EF-MRI) in a standard protocol and the evidence for its benefit is very weak.5, 6

Many centres favour the use of EF-MRI in the standard MR protocol. It is reported to improve the accuracy of localizing the tumour on rectal MRI and to enable a better overview of intraluminal lesions.7 It is also reported to reduce susceptibility artefacts on diffusion-weighted imaging caused by bowel gas by replacing the gas with gel.5, 8 Others claim that EF-MRI results in distension of the rectal wall that could stretch the tumour and especially in lower rectal cancer could lead to overestimation of an involved MRF anteriorly as a result of thinning of the mesorectal fat. Furthermore, it is hypothesized that evaluation of the nodes may be difficult because of compression of the mesorectal fat.9

In the current study, we aim to evaluate the influence of the use of EF-MRI in an MR rectal staging protocol.

Methods AND mATERIALS

Study design

Patients who underwent a clinical MRI scan of the rectum with and without EF-MRI and subsequent surgery in the period between July 2011 and September 2014 were retrospectively included in this study. The use of EF-MRI was standard clinical care at the institution during this time period. All patients had a biopsy-proven adenocarcinoma of the rectum and underwent a primary staging MRI scan with and without EF-MRI within one session. Patients were clinically diagnosed with Stage I– IV rectal cancer. Treatment of the patients varied from straight surgery to various neoadjuvant treatment schemes followed by surgery. All patients were evaluated for an initial comparison between the MR images with and without EF-MRI. Patients with straight surgery and patients with neoadjuvant short course 5 × 5 Gray radiotherapy followed by immediate TME were included for a comparison with pathological T-staging. All patients who underwent an MRI for primary rectal cancer staging were included for a comparison of the height of the tumour, the distance to MRF and the number of (suspicious) nodes. In case of insufficient quality of the MR examination or because of incomplete MR sequences, the scans were excluded for evaluation. This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board with a waiver of informed consent.

MRI

MRI imaging was performed at 3 T (Siemens Magnetom® Trio, Erlangen, Germany) using a spine coil and a phased-array body coil. Patients were placed in a supine, feet first position and received antispasmodic medication prior to the MRI examination unless a contraindication was present. The standard protocol started with an axial T2W pulse sequence: turbo (fast) spin echo (TSE), repetition time/echo time 3600–3850/93 ms, 3.0 mm slice thickness, two signal averages, field of view 200 × 200, matrix 448 × 448. After this sequence, approximately 100 cc ultrasound gel (Aquasonic® 100 ultrasound transmission gel) was endorectally administered to the patient on the MRI table in a lateral decubitus position with the knees towards the chest. After gel administration, the patient was repositioned in the MRI scanner to continue the clinical examination. The axial T2W TSE scan was repeated and three-dimensional T1W VIBE and T2W SPACE sequences were performed. As only the axial T2W TSE sequence was performed with and without EF, this was the only sequence that could be used for a comparison. The three-dimensional MR sequences unfortunately could not be used for an evaluation.

Evaluation of the MRI scans

The MR images were evaluated by two experienced radiologists specialized in abdominal imaging. Reader 1 and Reader 2 have 7 and 20 years of experience in reading rectal MRI, respectively. Reader 1 is experienced in evaluating MR images using EF-MRI. Reader 2 has no experience with this approach. The readers were blinded to the clinical data, histology and each other’s findings.

EF-MRI data sets were read first independently for all patients by both radiologists. After reading all EF-MRI images, the non-EF-MRI data sets were evaluated. All MR images were read on the same day, but due to the number of cases and the order of reading (EF-MRI first), it was unlikely that the non-EF-MRI reading was influenced by the previous EF-MRI reading of the same patients.

A standardized scoring form was used including the distance of the lower pole of the tumour to the anorectal junction, the shortest distance of the tumour to the MRF, the number of suspicious lymph nodes, the total number of lymph nodes, location of the tumour and the T- and N-stage. The distance to the MRF was only measured for patients with invasive growth through the rectal wall (cT3-4 tumours). The distance of the lower pole of the tumour to the anorectal junction was measured by the sum of the thickness of all axial MR slices from the anorectal junction to the lower pole of the tumour. An additional interslice distance of 10% for the transverse T2W MR images was taken into account.

Histopathological examination

Resection specimens were evaluated according to the method described by Quirke et al.10 The circumferential resection margin was considered positive when the distance of the resection margin to the tumour was ≤1 mm.11 The resected specimens were classified according to the Fifth American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging. Clinical and pathological T-stages were eventually compared in patients who were treated with straight surgery or with short course radiotherapy followed by immediate surgery.

Statistical analysis

The measurements of both radiologists regarding the distance of the tumour to the MRF and to anorectal junction and the number of (suspicious) nodes with and without EF-MRI were first analysed separately. Differences between these variables were calculated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The MR T-stages of the rectal tumours for both readers with and without EF-MRI were assessed in multiple cross tabulations. The agreement of the T-stages of the tumour between MR with and without EF-MRI and between readers was measured by calculating the Cohen’s κ value [agreement was: poor if intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) or κ ≤ 0.20, fair if 0.21 ≤ ICC or κ ≤ 0.40, moderate if 0.41 ≤ ICC or κ ≤ 0.60, substantial if 0.61 ≤ ICC or κ ≤ 0.80, good if ICC or κ > 0.80]. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (SPSS Inc., v. 22, Chicago, IL).

Results

The MR examinations of 65 patients were retrieved. MRIs of 18 patients were excluded because of an incomplete MRI examination or because of insufficient quality of either the MRI with or without EF-MRI. Ultimately 47 patients were eligible, who had MRI examinations both with and without EF-MRI. 25 patients underwent immediate TME, 8 patients had a short course (5 × 5 Gy) of radiotherapy followed by TME, 3 patients had a short course radiotherapy followed by TME after a prolonged time interval and 11 patients underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery. Surgery consisted of an anterior resection (32), abdominoperineal excision (9) or local excision (5). One patient underwent a wait and see approach after chemoradiotherapy.

Clinical parameters

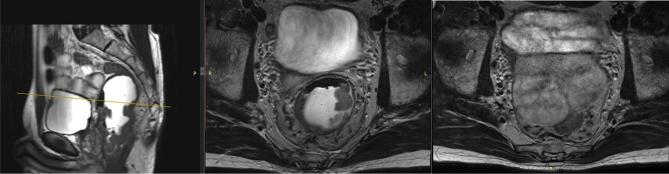

Table 1 shows the outcomes of the radiological assessment using the standardized score form. For Reader 1, there was no significant difference in the mean MR distance from the lower pole of the tumour to the anorectal junction with or without EF. There was no difference for the mean MR distance from the tumour to the MRF with EF-MRI as well as without EF-MRI. For Reader 2, a similar trend was observed, but with Reader 2 the mean MR distance of the lower pole of the tumour to the anorectal junction was significantly larger with EF-MRI as compared to without EF-MRI (p < 0.001). An example of this displacement is seen in Figure 1. The number of suspicious nodes and total number of nodes did not differ in the two different protocols and for both readers in 43 patients (Reader 1) and 42 patients (Reader 2), respectively. Reader 2 detected significantly more (suspicious) lymph nodes than Reader 1 with and without EF-MRI (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Measurements done by using the standardized score form

| Reader 1 | Reader 2 | |||||

| Without gel | With gel | p-valuea | Without gel | With gel | p-valuea | |

| Distance to anorectal junction (mm) | 41,6 (0–97,5) | 43,7 (0–93,6) | 0.313 | 33,9 (0–101,4) | 49,3 (0–113,1) | <0.001 |

| Distance to MRF (mm) | 5,3 (0–18) | 4,0 (0–13) | 0.115 | 4,4 (0–15) | 4,1 (0–15) | 0.109 |

| Suspicious nodes (mean per patient) | 1,8 (0–7) | 1,9 (0–18) | 0.691 | 4,8 (0–23) | 4,5 (0–29) | 0.512 |

| Total nodes (mean per patient) | 7,0 (0–25) | 7,0 (1–22) | 0.850 | 11,0 (1–33) | 10 (0–15) | 0.308 |

MRF, mesorectal fascia.

Calculated with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Figure 1.

Example of displacement of the tumour due to EF-MRI. In the left image, the cancer is displayed in the sagittal plane. The yellow bar in the left image presents the height of the middle and right images in the axial plane with and without EF-MRI. Due to EF-MRI—middle image—the proximal part of the tumour is still visible (white arrow). The absence of EF-MRI—right image—causes the rectum (white arrow) to collapse in the pelvis. EF, endorectal filling.

Staging the primary tumour

The agreement between the two readers for T-staging without EF-MRI was 46% (weighted κ 0.156) and the agreement between the two readers with EF-MRI was 41% (weighted κ 0.037). The intraobserver agreement for evaluating MRI with and without EF-MRI was good for Reader 1 (89% agreement, weighted κ 0.828) and fair for Reader 2 (63% agreement; weighted κ 0.346).

The accuracy of predicting the pathological T-stage for Reader 1 with EF-MRI was 55% (weighted κ 0.101) and the figures without EF-MRI were accurate in 64% (weighted κ 0.259). The accuracy for T-staging for Reader 2 with EF-MRI was 59% (weighted κ 0.208). Without EF-MRI, accuracy was 68% (weighted κ 0.528) with frequent overstaging seen for both readers. The 2 × 2 table for the comparison of clinical staging and the comparison with pathological staging with and without EF-MRI are given in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Comparison of the clinical (rows) and pathological (columns) T-stages for Reader 1 with and without endorectal filling

| Reader 1 | Pathological T-stage | Pathological T-stage | |||||||

| pT1-T2 | pT3 | Total | pT1-T2 | pT3 | Total | ||||

| Clinical T-stage with gel | cT1–cT2 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

Clinical T-stage without gel |

cT1–cT2 | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| cT3 | 10 | 13 | 23 | cT3 | 8 | 13 | 21 | ||

| cT4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | cT4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 14 | 16 | 30 | Total | 13 | 15 | 28 | ||

Table 3.

Comparison of the clinical (rows) and pathological (columns) T-stages for Reader 2 with and without endorectal filling

| Reader 2 | Pathological T-stage | Pathological T-stage | |||||||

| pT1–T2 | pT3 | Total | pT1–T2 | pT3 | Total | ||||

| Clinical T-stage with gel | cT1–cT2 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

Clinical T-stage without gel |

cT1-cT2 | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| cT3 | 11 | 13 | 24 | cT3 | 6 | 12 | 18 | ||

| cT4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | cT4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 14 | 13 | 27 | Total | 13 | 12 | 25 | ||

Discussion

This study investigated the influence of EF-MRI of rectal cancer on radiological staging of the disease. Two experienced readers evaluated multiple variables, leading to quite some heterogeneity in results. EF-MRI showed a significant difference towards an increased distance from the lower pole of the tumour to the anorectal junction in the reader without any previous experience in evaluating EF-MRI. EF-MRI showed no differences for the distances from the tumour to the MRF. There was also no difference in the number of (suspicious) lymph nodes between the two protocols, but the number of detected nodes varied significantly between the two readers. The accuracy for the assessment of the pathological T stage was lower with than without EF-MRI. Overstaging of the tumour frequently occurred with EF-MRI, and was most prominent in the reader without experience in evaluating EF-MRI. Because of the reading order (all EF-MRI data first), overstaging was not influenced by the MRI data without EF.

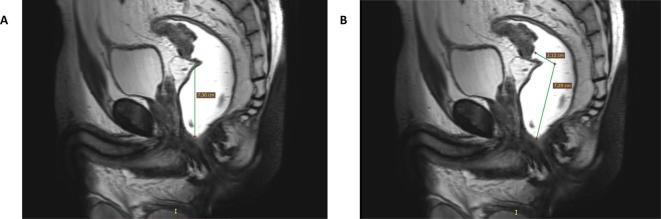

Of interest is that EF-MRI caused a longer distance of the tumour to the anorectal junction for one of the two readers. An explanation for an enlarged distance could be that due to EF, gel accumulates distally from the tumour. This could cause the rectum to stretch and the tumour to be pushed upwards. Also, at the proximal part of the rectum the mesorectal fat is more abundant, which spatially allows the rectum to expand. In the current study, the distances were measured by the sum of the axial slice thickness from the anorectal junction to lower pole of the tumour. Generally, this distance is measured on sagittal images (Figure 2), on which the curvature of the rectum can be taken into account. Therefore, the true distance may be even longer than when deducing this from axial slices. This means that EF-MRI can potentially overestimate the distance of distal rectal tumours with potential effect on treatment.12 The resected part of the rectum in TME surgery is, among other things, dependent on the distance of the lower pole of the tumour to the anorectal junction.13 Proximal or middle rectal tumours are preferably treated with an anterior resection and distal rectal tumours with an abdominoperineal excision.14–18 The use of EF-MRI may therefore have implications for clinical decision-making and thus, a proper estimation is desirable.

Figure 2.

Two T2 weighted sagittal images display how the distance of the lower pole of the tumour to the anorectal junction can be measured. (a) A sagittal representation of how the distance was measured in the current study, by counting the number of slices in the axial plane. (b) The distance of the lower pole of the tumour to the anorectal junction is measured by taking the curvature of the rectum into account when measuring the distance, recommended by the ESGAR consensus meeting.8

The results of our study also revealed that the use of EF-MRI did not significantly shorten the distance from the tumour to the MRF compared to without EF-MRI. Literature is controversial to perform filling of the rectum because of possible overestimation of involvement of the MRF.9 Ye et al19 observed a shortened distance of the rectal wall to the MRF, but at the site of the tumour the distance towards the MRF was not reduced. This could be explained by possible fibrotic changes and desmoplastic reactions at the site of the tumour which may lead to a stiffened environment and thus may not have an effect on the expansion.

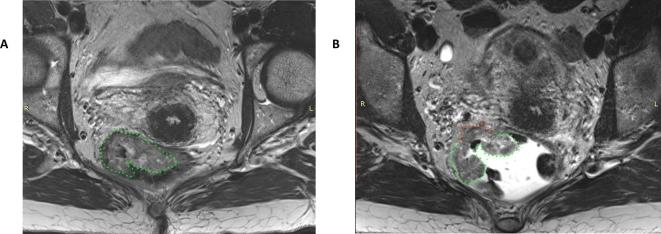

A frequently used argument propagating for EF is that it aids in detecting and delineating the tumour and consequently could aid in assessment of the pT stage.20 In our study, the admission of EF in this study negatively impacted the accuracy of T-staging for the reader with inexperience in scoring EF-MRI, of which an example is displayed in Figure 3. Reader 1 tended to overstage 71% of the pT1-2 tumours without EF-MRI and in 62% of the pT1-2 tumours with EF-MRI. For Reader 2, not using EF-MRI led to overstaging pT1-2 tumours in 46% and this percentage increased to 79% of the tumours when staged with EF-MRI. The use of EF-MRI led to a more frequent overstaging for this reader in early tumours, which are in general more difficult to stage using MRI.21 The current results could not confirm other’s observations of an improved T-staging,19 potentially due to the expansion of the rectum together with compression of the mesorectal fat. This expansion and compression can lead to a closer positioning of the rectum tumour towards surrounding structures, which can hypothetically induce overstaging especially in early tumours.9 Moreover, the filling may cause the rectal wall to be stretched suggesting the rectal wall to be thinner which may lead to an exaggeration of the invasive growth.

Figure 3.

Two axial T2 weighted images of a patient with mid-rectal, partly mucinous—delineated—rectal cancer without (a) and with (b) EF-MRI. Without EF-MRI (a), the tumour seems to be limited to the rectal wall (green). With EF-MRI the rectum is stretched, altering the impression of the tumour (arrow). Reader 2 staged the non-EF-MRI image a cT2 tumour and the EF-MRI image a cT3b tumour with the potential to threaten the MRF. Pathologic evaluation revealed a pT2 tumour.

The rectal distention by EF-MRI in our series did not affect the visualization and detection of the nodes independent of size and location, which was in line with other studies.19, 22 Lymph node staging on MRI remains challenging and this is again reflected in the current study by the difference in detected lymph nodes between the two readers. The revised recommendations of the ESGAR consensus meeting established new guidelines including the evaluation of the total number of suspicious vs total number of visible nodes as a criterion for metastatic nodes together with morphological and size features.6 In our study, Reader 1 detected a lower total number of nodes than Reader 2. We hypothesize that the performance of nodal staging may be dependent on the reader’s experience, however, this was not validated in our study.

This study had some limitations. One limitation is that only axial images were used for the comparison between the two protocols.5 Therefore, the distance of the lower pole of the tumour to the anorectal junction could be underestimated. Another limitation is that the scanned region of the (meso)rectum varied. The proximal margin of the field of view was not consistently set to a specific anatomical landmark. This varied not only between the patients, but could also vary within the same patient. As a result, the comparison for the lymph nodes could not be performed in four patients. Nor did we include the influence of EF on diffusion-weighted MRI.

In conclusion, the admission of EF in a standard MR protocol of rectal cancer could influence the measured distances of tumour to the anorectal junction and MRF. Our small study suggests a tendency towards overestimation of the height of a tumour for the reader with inexperience in evaluating EF-MRI, which not affected the experienced reader. Furthermore, the use of EF could not improve T-staging. Although validation is needed in a larger cohort, our study does not generate stronger arguments for the use of EF in a standard MR protocol.

Footnotes

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Radboudumc.

Contributor Information

Rutger CH Stijns, Email: R.Stijns@radboudumc.nl.

Tom WJ Scheenen, Email: Tom.Scheenen@radboudumc.nl.

Johannes HW de Wilt, Email: Hans.deWilt@radboudumc.nl.

Jurgen J Fütterer, Email: Jurgen.Futterer@radboudumc.nl.

Regina GH Beets-Tan, Email: r.beetstan@nki.nl.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heald RJ, Ryall RD. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet 1986; 1: 1479–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91510-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eriksen MT, Wibe A, Haffner J, Wiig JN. Norwegian Rectal Cancer Group Prognostic groups in 1,676 patients with T3 rectal cancer treated without preoperative radiotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum 2007; 50: 156–67. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0757-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosch SL, Vermeer TA, West NP, Swellengrebel HA, Marijnen CA, Cats A, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics predict lymph node metastases in ypT0-2 rectal cancer after chemoradiotherapy. Histopathology 2016; 69: 839–48. doi: 10.1111/his.13008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MERCURY Study Group. Diagnostic accuracy of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging in predicting curative resection of rectal cancer: prospective observational study. BMJ 2006; 333: 779. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38937.646400.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beets-Tan RG, Lambregts DM, Maas M, Bipat S, Barbaro B, Caseiro-Alves F, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for the clinical management of rectal cancer patients: recommendations from the 2012 European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) consensus meeting. Eur Radiol 2013; 23: 2522–31. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2864-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beets-Tan RGH, Lambregts DMJ, Maas M, Bipat S, Barbaro B, Curvo-Semedo L, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for clinical management of rectal cancer: Updated recommendations from the 2016 European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) consensus meeting. Eur Radiol 2018; 28: 1465-1475. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5026-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SH, Lee JM, Lee MW, Kim GH, Han JK, Choi BI. Sonography transmission gel as endorectal contrast agent for tumor visualization in rectal cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 191: 186–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaur H, Choi H, You YN, Rauch GM, Jensen CT, Hou P, et al. MR imaging for preoperative evaluation of primary rectal cancer: practical considerations. Radiographics 2012; 32: 389–409. doi: 10.1148/rg.322115122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slater A, Halligan S, Taylor SA, Marshall M. Distance between the rectal wall and mesorectal fascia measured by MRI: Effect of rectal distension and implications for preoperative prediction of a tumour-free circumferential resection margin. Clin Radiol 2006; 61: 65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2005.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quirke P, Palmer T, Hutchins GG, West NP. Histopathological work-up of resection specimens, local excisions and biopsies in colorectal cancer. Dig Dis 2012; 30(Suppl 2): 2–8. doi: 10.1159/000341875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Netherlands Dwggtocct. National guideline on colorectal cancer. 2014. Available from: www. oncoline.nl [last update 16 April 2014].

- 12.Keller DS, Paspulati R, Kjellmo A, Rokseth KM, Bankwitz B, Wibe A, et al. MRI-defined height of rectal tumours. Br J Surg 2014; 101: 127–32. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bujko K, Rutkowski A, Chang GJ, Michalski W, Chmielik E, Kusnierz J. Is the 1-cm rule of distal bowel resection margin in rectal cancer based on clinical evidence? A systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19: 801–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2035-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott N, Jackson P, al-Jaberi T, Dixon MF, Quirke P, Finan PJ. Total mesorectal excision and local recurrence: a study of tumour spread in the mesorectum distal to rectal cancer. Br J Surg 1995; 82: 1031–3. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagtegaal ID, Knijn N, Hugen N, Marshall HC, Sugihara K, Tot T, et al. Tumor deposits in colorectal cancer: improving the value of modern staging-A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 1119–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.9091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson H, Petrelli N, Carlin A, Couture J, Fleshman J, Guillem J, et al. National Cancer Institute Expert Panel Guidelines 2000 for colon and rectal cancer surgery. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001; 93: 583–96. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.8.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Law WL, Chu KW. Anterior resection for rectal cancer with mesorectal excision: a prospective evaluation of 622 patients. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 260–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glimelius B, Tiret E, Cervantes A, Arnold D. ESMO Guidelines Working Group Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2013; 24(Suppl 6): vi81–vi88. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye F, Zhang H, Liang X, Ouyang H, Zhao X, Zhou C. JOURNAL CLUB: Preoperative MRI Evaluation of Primary Rectal Cancer: Intrasubject Comparison With and Without Rectal Distention. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2016; 207: 32–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.15383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tapan U, Ozbayrak M, Tatlı S. MRI in local staging of rectal cancer: an update. Diagn Interv Radiol 2014; 20: 390–8. doi: 10.5152/dir.2014.13265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Sukhni E, Milot L, Fruitman M, Beyene J, Victor JC, Schmocker S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of MRI for assessment of T category, lymph node metastases, and circumferential resection margin involvement in patients with rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19: 2212–23. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2210-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim MJ, Lim JS, Oh YT, Kim JH, Chung JJ, Joo SH, et al. Preoperative MRI of rectal cancer with and without rectal water filling: an intraindividual comparison. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004; 182: 1469–76. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.6.1821469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]