Abstract

Obesity constitutes a major global health threat. Despite the success of bariatric surgery in delivering sustainable weight loss and improvement in obesity-related morbidity, effective non-surgical treatments are urgently needed, necessitating an increased understanding of body weight regulation. Neuroimaging studies undertaken in people with healthy weight, overweight, obesity and following bariatric surgery have contributed to identifying the neurophysiological changes seen in obesity and help increase our understanding of the mechanisms driving the favourable eating behaviour changes and sustained weight loss engendered by bariatric surgery. These studies have revealed a key interplay between peripheral metabolic signals, homeostatic and hedonic brain regions and genetics. Findings from brain functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have consistently associated obesity with an increased motivational drive to eat, increased reward responses to food cues and impaired food-related self-control processes. Interestingly, new data link these obesity-associated changes with structural and connectivity changes within the central nervous system. Moreover, emerging data suggest that bariatric surgery leads to neuroplastic recovery. A greater understanding of the interactions between peripheral signals of energy balance, the neural substrates that regulate eating behaviour, the environment and genetics will be key for the development of novel therapeutic strategies for obesity. This review provides an overview of our current understanding of the pathoaetiology of obesity with a focus upon the role that fMRI studies have played in enhancing our understanding of the central regulation of eating behaviour and energy homeostasis.

Introduction

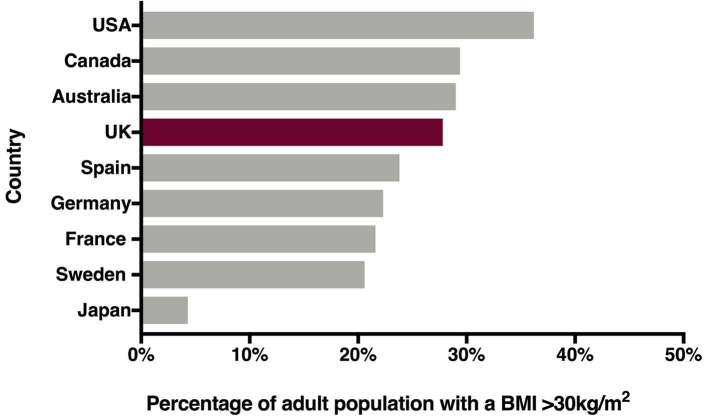

The worldwide prevalence of overweight and obesity is rising. It is estimated that worldwide more than 650 million people were obese in 2016.1 In the United Kingdom, 63.7% of the population were overweight or obese in 2016 and 27.8% obese (Figure 1).2 Prevalence is set to continue to rise with a consequential increase in associated morbidity, such as Type 2 diabetes (T2D), cardiovascular disease and certain cancers, as well as mortality.1 Management of the obesity epidemic hence poses a major and urgent challenge.

Figure 1.

Obesity prevalence across different populations in 2016 Chart illustrating rates of obesity across different countries, defined by a body mass index >30 kg m–2. Data from World Health Organisation global health observatory.2 Abbreviations United States of America (USA), United Kingdom (UK).

Weight loss induced by lifestyle interventions that engender an energy deficit is usually not durable in the long term, as a consequence of the powerful compensatory biological mechanisms that occur as a response to weight loss.3 To date, bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for severe obesity, resulting in marked and sustained weight loss in the long term.4 Accessibility and cost, however, pose barriers to surgery, calling for a greater understanding of the physiological processes underpinning the success of bariatric surgery and development of effective non-invasive treatment options. Following bariatric surgery, weight loss is driven by reduced energy intake as a consequence of post-operative changes in appetite, gustatory and olfactory function, as well as a change in food preference away from energy-dense foods.5 Moreover, bariatric surgery alters the perception and hedonic value of food, an observation that has inspired studies into both structural and functional processes that regulate eating behaviour within the central nervous system (CNS).

Studies using brain fMRI have begun to provide insights into the effect of overweight, obesity and weight loss upon CNS responsiveness. By measuring the degree of blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) contrast, which signals activity-related change in neural activity, fMRI allows detection of event-related transient neuronal activity.6 Food cues, acting as conditioned stimuli, are hence commonly incorporated into fMRI experimental paradigms, to trigger central responses and motivate food consumption.6

A growing body of evidence suggests that obesity leads to changes in both structure and connectivity within the brain.7–9 Interestingly, several of these obesity-associated neural changes have been linked to obesity-related metabolic abnormalities and may predispose individuals to overeating. However to date, the interplay between neural and metabolic signals and their ultimate effect upon eating behaviour and body weight remain incompletely understood. Here, we review current insights gained into the understanding of the pathophysiology of obesity as well as the changes engendered by bariatric surgery through brain fMRI studies.

Body weight regulation

Body weight regulation is a complex process involving integration of information from homeostatic and reward-related pathways. A multitude of factors determine the decision to eat: physiological signals of energy availability, reward-related responses, sensory cues, social and emotional aspects, as well as cognitive processes.10 Interestingly, metabolic signals from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract modulate activity in both homeostatic and hedonic brain centres controlling eating behaviour.10

Long-term energy availability signals feedback information regarding adiposity-related energy stores via insulin and leptin secretion.11 Both of these peptides have an established role in energy homeostasis, with appetite-suppressing effects. Short-term signals of energy availability originating in the GI tract relate to nutrient- and meal-derived energy availability and regulate perceptions of hunger and satiety.10 Nutrient ingestion alters the secretion of a variety of metabolically active peptides in the GI tract. Circulating levels of ghrelin, an orexigenic hormone secreted primarily by the gastric fundus, increase in the fasted state, generating perceptions of hunger and promoting meal initiation.12 In response to nutrient intake, ghrelin levels rapidly decline, whilst enteroendocrine L-cells secrete the anorectic hormones peptide YY3-36 (PYY), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and oxyntomodulin.13–15 Somatosensory vagal afferents convey information on gastric distension.16 Once nutritional needs are met, these factors generate satiety signals in the CNS. Bile acids are synthesised in the liver and secreted in response to nutrient ingestion; they directly facilitate the absorption of dietary fat and when secreted into the intestinal environment directly impact upon the microbiome.17 The intestinal microbiome, made up of a large number of diverse, symbiotic microbial cells, in turn is speculated to contribute toward nutrient absorption by influencing intestinal permeability.15 However, the desire to eat can persist beyond meeting nutritional requirements, driven by hedonic responses and emotional factors. In an environment of high energy availability, the decision to eat, subsequent calorie intake and ultimately body weight are determined by factors beyond homeostasis.

Regulation of eating behaviour: insights from brain fMRI studies

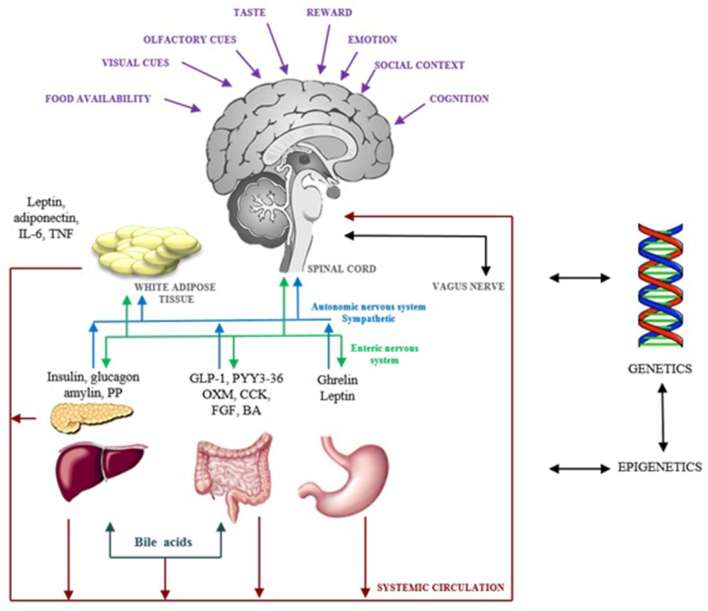

Eating behaviour is controlled by three interrelated neural networks: the homeostatic network, regulated via the gut–brain axis; the appetitive network, which includes reward-related pathways; and higher level cognitive processes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Regulation of eating behaviour Schematic diagram illustrating the major processes involved in regulating eating behaviour. Neural and metabolic signals continuously feed back information regarding nutrient availability and the intestinal milieu to homeostatic centres in the hypothalamus and brain stem. The appetitive network integrates information from food cues, such as sight, taste and smell, reward-related information and social and emotional factors with cognitive processes.10 Both homeostatic and hedonic drivers for eating behaviour are subject to individual predisposition from genetic and epigenetic factors. Abbreviations: interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumour necrosis factor (TNF), pancreatic polypeptide (PP), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), peptide YY3-36 (PYY), oxyntomodulin (OXM), cholecystokinin (CCK), fibroblast growth factors (FGF), bile acids (BA).

The gut–brain axis

Gut hormones act upon central circuits regulating eating behaviour (Table 1). Cognate receptors, specific for gut hormones including PYY, GLP-1 and ghrelin, are present throughout the CNS.10 Multiple fMRI studies have utilised gut hormones to delineate the brain regions that regulate eating behaviour.6, 18 These studies have revealed a direct link between circulating gut hormone levels and modulation of neural activity within brain regions controlling appetite.18 For instance, peripheral ghrelin administration was shown to increase neural responses to food cues; activation of the amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), anterior insula and striatum correlate with plasma ghrelin levels in healthy adults.19 Peripheral administration of ghrelin following a meal also enhances neural activity and responses to food cues comparable to those seen in fasting conditions in normal weight adults.20 Conversely, reductions in post-meal circulating ghrelin levels correspond to attenuated food-cue responsiveness in the same areas.21 Insulin and glucose also have established effects on appetite circuits.18 Hypoglycaemia induced by administering i.v. insulin leads to activation in the hypothalamus, insula, putamen and caudate nucleus, thereby increasing the desire to eat, whereas euglycaemia activates the medial prefrontal cortex.22 A series of brain fMRI studies have revealed a negative correlation between plasma insulin levels and BOLD activity in the hypothalamus, thalamus, insula, amygdala and the limbic system.23–25 A study investigating food-cue reactivity and leptin showed a positive correlation between leptin levels and ventral tegmental area (VTA) BOLD activity in response to viewing food images.26

Table 1.

| Brain area | Role in eating behaviour |

| Hypothalamus | Homeostatic control |

| Hippocampus | Learning and memory Links energy balance to incentive behaviour |

| Amygdala | Emotional learning, assigning of value Encodes palatability of foods Link between homeostatic and hedonic interactions |

| Insula | “ingestive” and “gustatory” cortex Encodes sensory information of taste, integrated with sensory cues to form flavour Responds to food cues and gut hormones |

| Nucleus of the solitary tract | Afferent target for vagus nerve |

| Ventral tegmental area | Dopaminergic neurons Encodes nutritional and reward values of food Generated value and motivational signals |

| Cerebellum | Integrates and coordinates somatic–visceral responses to food |

| Striatum: Caudate nucleus Putamen Nucleus accumbens | Encodes motivational and incentive properties of food Anticipatory reward Connected to all other brain regions of eating behaviour Links motivation to action |

| Orbitofrontal cortex | Reward encoding Integration of sensory, cognitive and reward aspects |

| Cingulate cortex | Decision-making |

| Prefrontal cortex | Translation of internal and external cues to behaviour |

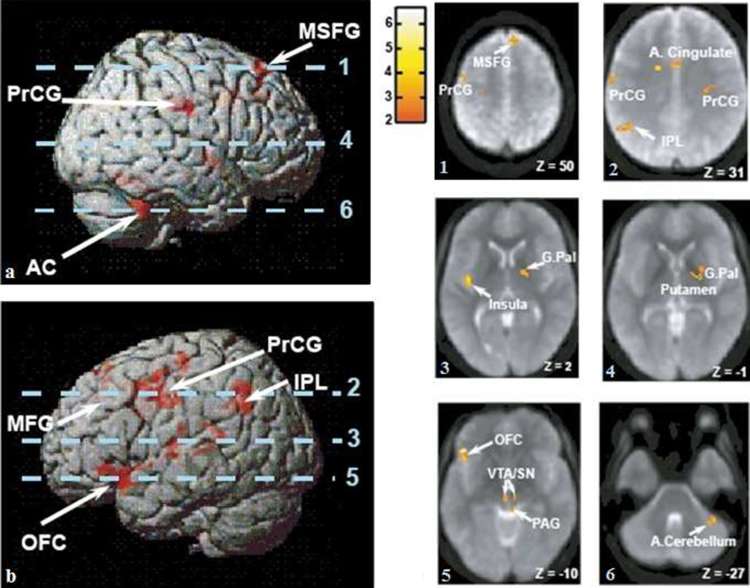

In contrast, biochemical signals generated in response to nutrient ingestion feed back to homeostatic brain centres with a subsequent reduction in food-related reward. For example, in normal weight individuals, brain reactivity to food images is diminished following glucose administration.24 Furthermore, the satiety gut hormone PYY mediates its anorectic effects by acting on central appetite-regulating circuits (Figure 3).27 In a cross-over study investigating the effects of PYY versus placebo (saline) infusion in fasted healthy volunteers, infusion of PYY resulted in activation of the caudolateral OFC as well as the brain stem parabrachial nucleus, ventral tegmental area (VTA), insula, anterior cingulate cortices and ventral striatum. Plasma PYY levels correlated negatively with activity in the right middle frontal gyrus and right angular gyrus, whereas activity in these areas increased with saline infusion.27 Furthermore, PYY administration led to a 24.8 ± 4.1% decrease in energy intake and a significant reduction in acylated ghrelin levels. During saline infusion, when PYY levels were low, hypothalamic activity correlated with subsequent energy intake. In contrast, following PYY infusion in conditions mimicking the fed state, OFC activity predicted energy intake, indicating that PYY switches the control of eating behaviour changes from homeostatic to hedonic centres.27

Figure 3.

Brain activation by gut hormone PYY Brain areas activated by intravenous infusion of PYY are illustrated.27 Parts a and b demonstrate surface-rendered views of the left and right hemispheres with superimposed areas of functional activity in response to PYY, with the depth of activation illustrated by image saturation (red). The axial slices illustrated in images 1–6 are indicated by dotted lines. 1–6: Axial slices with superimposed group functional activity from averaged echo planar images. The scale represents the functional activity T value and Z the Talairach Z co-ordinate of the axial slice. Abbreviations: anterior cerebellum (AC), anterior cingulate (A. cingulate), globus pallidus (G.Pal), inferior parietal lobule (IPL), middle frontal gyrus (MFG), medial superior frontal gyrus (MSFG), caudolateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), peptide YY3-36 (PYY), peri-aqueductal grey (PAG), precentral gyrus (PrCG), substantia nigra (SN), ventral tegmental area (VTA). Figure adapted from Batterham et al27.

Leidy et al demonstrated a negative correlation between amygdala, hippocampal and para-hippocampal activity and rising circulating PYY levels.28 A study utilising PYY and GLP-1 infusions separately and together and comparing them to the effects of a meal on fMRI brain activations revealed that PYY and GLP-1 induced changes in brain activity and reduced energy intake comparable to a meal.29 Douglas et al demonstrated that consumption of a high protein meal led to rises in PYY and GLP-1 levels and reduced anterior cingulate and insular activity.30 Taken together, these findings demonstrate that PYY and GLP-1 synergistically modulate the appetitive brain network and reduce the reward value of food.

Beyond homeostasis

In environments where high-energy dense foods are readily available, eating behaviour and energy intake are controlled largely by aspects beyond homeostatic control, such as cognition, reward and emotional and social factors.10 Taste and smell have a major impact upon food choice and enjoyment whereas visual, gustatory and olfactory cues can influence the motivation and decision to eat.31 The motivation to eat can result from recall of a previous reward response generated by the same stimulus, which can motivate eating in the absence of an energy need.10 Interestingly, exposure to food cues in isolation, without energy intake, can elicit de novo metabolic responses. Receptors for insulin, leptin, ghrelin, PYY and GLP-1 have been detected in saliva and their cognate receptors on taste buds and olfactory neurons, suggesting these may have a role in modulating taste and smell perception.31 Circulating ghrelin levels rise in anticipation of a planned meal and when subjects are instructed to anticipate food.32 Ghrelin levels have been correlated with olfactory function and modulate olfactory responsiveness by increasing CNS responses to olfactory stimuli.33 In addition, hedonic responses to food images have been directly correlated to ghrelin levels.34 However, cue reactivity is also subject to cognitive modulation. A number of fMRI studies have examined the impact of cognition upon brain responses elicited by food cues and suggest that appetite and reward-related responses can be suppressed depending on a goal or cognitive context.35–37

Physiology of weight gain

Weight gain occurs when energy intake chronically exceeds energy needs. In addition to accumulation of adipose tissue, weight gain also leads to dysregulation of the homeostatic signals that control energy balance.38 Resistance to leptin and insulin, attenuated postprandial secretion of PYY and GLP-1 and dysregulated ghrelin secretion, reduced bile acids and changes in the intestinal microbiome occur as a result of obesity.38, 39 Furthermore, decreased gustatory and olfactory sensitivity are seen, in addition to exacerbated reward responses to food.40–42 Individuals with obesity rate energy dense foods as more pleasurable, and foods high in sugar and fat elicit higher reward responses in obese compared to lean individuals.43–45

Furthermore, weight gain leads to structural and connectivity changes within the CNS. Structural changes identified include grey matter shrinkage, reduced hippocampal volume and decreased white matter integrity, which have been linked to impaired insulin and glucose metabolism.24,46–50 A study investigating OFC volumes in obesity showed lower grey and associated white matter volumes in obese compared to lean individuals.51 Global brain connectivity (GBC) is a measure of brain network integrity, measured by the number of connections between functional units within brain networks. GBC associates with cognitive function and cerebral metabolism. fMRI studies demonstrate a linear association between reductions in GBC and increasing body mass index (BMI).8, 9,49 A study by Geha et al compared GBC at rest and during milkshake consumption in 15 healthy weight and 15 obese individuals.7 GBC consistently decreased in the ventromedial and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, insula and caudate nucleus and increased in premotor areas, superior parietal lobule and visual cortex in obese individuals at rest and during milkshake consumption. This suggested a state-independent alteration in the balance of GBC between regions monitoring orosensory and reward value of food and regions related to orientation towards these stimuli in the external environment. The authors concluded that GBC in obesity is impaired between areas monitoring internal milieu and external environment.7 Furthermore, reduced striatal activation in response to milkshake exposure was associated with obesity and future weight gain.7 Cumulatively, these findings suggest that obesity leads to reorganisation of brain connectivity. Although the directionality of this effect remains to be established, altered GBC may influence food choice, motivation to eat and ultimately contribute to weight gain.

Hence, with continuous weight gain, eating behaviour and appetite become disjointed from hunger and satiety; the resulting altered metabolic and neurological responses to food subsequently predispose individuals with obesity to further weight gain.38, 45

However, not all individuals are equally susceptible to weight gain. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have concluded that at least 85% of BMI variability is heritable and an increasing body of evidence links genetic markers of obesity predisposition with unfavourable metabolic profiles.52, 53 For instance, mutations in the central melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R), which has a key role in integrating peripheral signals into neural networks and activates a satiety-inducing pathway in a PYY- and GLP-1-dependent manner, result in hyperphagia, insulin resistance, preference for high fat foods and obesity.54, 55 A cluster of SNPs within the first intron of the fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene have been associated with increased adiposity. Of these SNPs, rs9939609 is the most consistently studied in European populations and the obesity-risk A-allele has been found to correlate with increased adiposity across different ages.56 Homozygous A-allele individuals (AA) have a higher energy intake and are predisposed to obesity, whereas a TT genotype has a protective effect.56 Normal weight AA individuals have attenuated postprandial ghrelin and hunger suppression and increased food-cue reactivity in homeostatic and reward areas on fMRI in fasted and fed conditions, changes which may predispose to excess energy intake leading to weight gain.57

In addition to genetics, epigenetic factors in utero and early childhood can trigger a predisposition to weight gain later in life.58, 59 Obesity hence is the consequence of an interaction between genetic predisposition and a high-risk environment of excess energy availability.

The role of brain imaging in understanding obesity

A series of brain fMRI studies have provided insights into obesity-related changes in brain responses to food cues and improved our understanding of the biological and behavioural substrates that predispose to overeating and obesity. Greater BOLD activity in response to food cues, both in emotional and physiological responses, has been a consistent finding in obesity.9, 60,61 In addition to previous evidence demonstrating greater salivation, insulin release, appetite and energy intake, a number of studies displaying food images during fMRI scanning have consistently shown increased activation in response to high-calorie food images in reward-related areas (striatum, hippocampus, insula and OFC) in obese compared to lean individuals.61–64 In obese individuals, this effect is augmented by consumption of glucose.65 Furthermore, the degree of BOLD activation is independent of appetite and hunger,66 and positively correlates with increasing BMI.60

Gustatory and olfactory cue delivery is being increasingly incorporated into fMRI study paradigms. Stronger reward responses to taste are seen in obesity.65, 67,68 In a study delivering quinine, glucose and milkshake in-scan, stronger activation was detected in various cortical (anterior cingulate cortex, insular and opercular cortices, OFC) and subcortical (amygdala, nucleus accumbens, putamen and pallidum) areas with all stimuli in obese compared to lean individuals.69 A study of 26 individuals with overweight and obesity showed augmented reward-related responses to delivery of a high-calorie beverage, which additionally correlated with a higher number of binge-eating symptoms.60 An fMRI study investigating odour perception demonstrated that obese and overweight individuals perceived these to be stronger when hungry, which correlated with ghrelin levels and BOLD responses in the cerebellum.70 Cumulatively, these data suggest that obese individuals demonstrate increased food-cue reactivity, which may drive a higher energy intake.

Furthermore, fMRI paradigms have also investigated goal-driven behaviour and control of motivated behaviour in obesity. These have associated obesity with impaired self-control and executive function.37, 63,71 The prefrontal cortex has been implicated as a control centre for motivated behaviour. A systematic review of studies investigating executive function in adults with obesity suggests that individuals with obesity show difficulties in decision-making, planning and problem-solving compared to lean controls.68 It has been implied that reduced prefrontal cortex function may compromise self-control and predispose to overeating.

Obesity treatment

Physiological barriers to weight loss

Lifestyle interventions, the cornerstone of weight management strategies, aim to create a state of negative energy balance, whereby energy expenditure consistently exceeds intake. However, whilst weight loss is readily achievable, weight recidivism occurs in the majority of people. A state of negative energy balance results in compensatory biological changes that aim to defend the higher body weight, in the form of decreased energy expenditure, reduced circulating leptin, GLP-1 and PYY levels with increased ghrelin levels.3, 72 These biological changes lead to increased hunger coupled with reduced satiety, a heightened food-cue reactivity and increase motivation to eat.

Bariatric surgery

Bariatric surgery to date is the only effective therapeutic intervention for people with severe obesity, defined by a BMI ≥ 40 kg m–2 or ≥ 35 kg m–2 with an associated co-morbidity. Currently, the most commonly performed procedures are the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and sleeve gastrectomy (SG).73 Both procedures produce significant sustained weight loss and lead to improvement or resolution of complications, including Type 2 diabetes, hypertension, fatty liver disease and obesity-associated infertility, as well as reduced mortality.4 Bariatric procedures were initially intended to cause weight loss through either physically restricting energy intake, such as in gastric banding, and/or reducing energy absorption through malabsorption, such as in the duodenal switch.74 However, the changes in gastrointestinal anatomy in both RYGB and SG result in a number of physiological adaptations which drive weight loss independent of malabsorption and restriction, hence this classification is no longer applied to RYGB or SG.74, 75 Although these remain to be fully understood, they drive weight loss by means of changing eating behaviour, which in turn reduces energy intake.

Following bariatric surgery, in addition to increased satiety and reduced hunger levels, a marked change in food choice is seen.76, 77 People report a change in food preference away from foods high in sugar and fat, which commonly cause aversions.78–81 Furthermore, people post-bariatric surgery commonly report a new preference for healthier foods.81 These changes occur immediately following surgery and prior to weight loss, suggesting a procedure-related effect.

Taste and olfactory changes are also common, which have been subject to growing research interest.80, 82 An increased taste sensitivity, measured by assessing the ability to detect tastes, is seen after bariatric surgery, particularly for sweet and salty stimuli.83, 84 Furthermore, people assign lower hedonic values and reduced liking scores to tastes previously perceived as pleasant. Desire to eat and tendencies towards food-addictive behaviour also decrease following bariatric surgery.5 Studies examining post-olfactory changes have yielded inconclusive results, although improved olfactory sensitivity has been associated with SG.84, 85 Furthermore, taste changes have been demonstrated to predict weight loss following RYGB and appetite changes post-SG. In conjunction, these findings suggest that appetite, taste and smell changes contribute to altered food preference and eating behaviour, which results in a reduced energy intake, the main driver for weight loss.86

Biological mediators of weight loss following bariatric surgery

A robust and growing body of evidence into the mechanisms mediating weight loss after bariatric surgery has emerged over recent years, which, albeit incompletely understood, demonstrate that bariatric surgery alters the GI milieu and engenders an array of physiological changes. These include altered gut hormone profiles, changes in bile acid secretion and the intestinal microbiome.15

RYGB and SG are anatomically distinct procedures and therefore also differentially impact upon GI physiology. Altered and accelerated nutrient flow within the GI tract brings upon a multitude of changes in gut-derived signals. For instance, enhanced nutrient stimulation of the intestinal enteroendocrine L-cells is believed to result in the increased secretion of PYY and GLP-1 seen after bariatric surgery. Enhanced meal stimulated PYY and GLP-1 secretion are seen following both procedures; however, this is more marked post-RYGB. PYY and GLP-1 have been demonstrated to have a causal role in the reduced energy intake observed after RYGB.87 Supporting this is the recent finding that combined blockage of GLP-1 and PYY following RYGB increases food intake by 20%.88 Reductions in circulating ghrelin levels are also observed; however, given the majority of ghrelin-secreting cells are removed in SG, a more marked and sustained reduction is seen compared to RYGB.

RYGB and SG both lead to increased bile acid secretion and changes in the composition of bile acid, which in turn have been linked to improved glucose and lipid metabolism.89 Furthermore, it has been suggested that bariatric surgery creates a new interplay between bile acids, gut hormones and the microbiome. Bile acids can stimulate L-cell receptors and trigger gut hormone secretion.15 For instance, oral bile acid administration resulted in PYY and GLP-1 secretion in fasted individuals.90 Bile acids and gut hormones impact upon the intestinal microbiome, and reversal of obesity-related changes in the microbiota has been seen following bariatric surgery.15

However, despite the success of bariatric surgery, it has to be borne in mind that weight loss follows a wide normal distribution.91 Studying patients with differential responses to surgery provides key insights into the mechanisms mediating weight loss and will aid in the development of future non-operative therapies.

Neuroimaging insights following bariatric surgery

A series of fMRI studies undertaken in the bariatric surgery population are beginning to shed light into the biological mechanisms that underpin changes in eating behaviour, as well as the interplay between the gut and brain that contribute to the successful outcomes of bariatric surgery (Table 2).

Table 2.

Key neuroimaging studies in the bariatric surgery population

| Neuroimaging studies investigating food preference and taste | ||||

| Study | Sample | Intervention | Main results | |

| Frank et al92 | 12 RYGB 12 Obese control Both groups with T2D | High-calorie and low-calorie food images Liking and wanting scores Behavioural surveys | Lower liking and wanting ratings and lower scores in eating behaviour-related traits post-RYGB had higher activation in visual, frontal control, somatosensory, motor, memory-related and gustatory regions. Control group had higher activation in inhibition and reward areas | RYGB alters food-related reward-activation in the brain in subjects with diabetes |

| Faulconbridge et al93 | 22 RYGB 18 Sleeve gastrectomy 19 Weight-stable obese control | Response to images of high- calorie (HCF) versus low-calorie foods (LCF) | Baseline liking of HCF higher than LCF in all groups. At 6 months, lower HCF liking score in RYGB and SG. Significant decline in VTA BOLD responses for HCF vs LCF post-RYGB Fasting circulating ghrelin correlated with VTA BOLD responses in RYGB and SG | The VTA is a crucial site for modulating liking of highly palatable foods after bariatric surgery. Ghrelin is a potential mediator for these changes |

| Goldstone et al94 | 11 RYGB (7 completed) 9 Band 10 Non-obese weight-stable control | Octreotide administration Progressive ratio Task Food Images VAS | Octreotide-suppressed GLP-1, PYY, insulin and FGF19 and increased reward area BOLD responses, which correlated with circulating PYY level reduction | Reduced hedonic value of food may be mediated by anorectic effects of elevated circulating gut hormones |

| Ten Kulve et al95 | 10 RYGB | Visual Cues Taste Delivery (chocolate milk) Exendin 9–39 administration | Reduced BOLD activity in response to viewing and tasting palatable foods post-RYGB GLP-1R blockade led to higher BOLD activity in reward areas in response to food images and taste | GLP-1 may mediate the reduced reward activation to visual and gustatory food cues post-RYGB |

| Wang et al96 | 13 RYGB (6 completed) 7 Non-obese nonsurgical control | Taste delivery (sweet and salty stimuli) | Significant decrease in reward centre BOLD activation in response to sweet taste post-RYGB (same effect seen in control groups) Significant increase in reward centre and gustatory BOLD activity in response to salty taste post-RYGB | fMRI BOLD responses do not always correlate with subjective reports. RYGB may mediate changes in salt taste |

| Neuroimaging studies investigating structural and connectivity changes | ||||

| Olivo et al97 | 16 RYGB 12 Non-obese controls | Resting-state connectivity after overnight fast and 260kCal load VAS | Connectivity between regions involved in food-related saliency attribution and reward-driven eating behaviour stronger in obese people pre-surgery compared to controls and weakened post-RYGB changes in cognitive control of eating at 1 year Early reduced connectivity between emotional control and social cognition regions post-RYGB, but increased by 12 months. Presurgery findings predict weight loss | RYGB may reshape the brain’s functional connectivity. Changes in cognitive control of eating could play a major role in the success of surgery |

| Zhang et al98 | 15 SG 18 Normal weight controls | Fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, grey and white matter densities | Decreased FA values, GM/WM densities and increased MD value in brain regions associated with food intake and cognitive-emotion regulation | SG leads to acute partial neuroplastic structural recovery, which may drive behavioural changes in eating post-SG |

BOLD, blood oxygen-level dependent; FA, fractional anisotropy; GM, grey matter; HCF, high-calorie foods; LCF, low-calorie foods; MD, mean diffusivity; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG, sleeve gastrectomy; VTA, ventral tegmental area; VAS, visual analogue scale; WM, white matter.

Reward responses to food cues have been investigated in a small number of studies, which suggest that the enhanced food-cue responsivity seen in people with severe obesity resolves following bariatric surgery.92, 99,100 More recently, three studies have coupled food-cue fMRI responses with circulating gut hormone levels. In a prospective study, people with severe obesity underwent fMRI imaging before and after RYGB (n = 22), SG (n = 19) compared to a control group with weight-stable severe obesity (n = 19) who were imaged twice, 6 months apart. High- and low-calorie food images were displayed during scanning. 6 months from surgery, liking for high-calorie images had significantly reduced in the RYGB and SG groups.93 BOLD responses in the VTA to high-calorie versus low-calorie images declined significantly after RYGB but not in SG, and fasting circulating ghrelin levels correlated with VTA BOLD responses in RYGB and SG, but not in control subjects. The second study combined in-scanner food-cue evaluation with octreotide administration—a somatostatin analogue with widespread endocrine inhibitory effects, including gut hormone blockade—in participants post-RYGB.94 Octreotide increased both appetitive food reward and appeal, and reward-area BOLD signals correlated with reductions in circulating PYY.94 The third study investigated the role of GLP-1 by utilizing the specific GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) antagonist exendin 3–39, in 10 females during food picture viewing and chocolate milk consumption before and after RYGB.95 BOLD responses in the caudate nucleus in response to food images, and in the insula in response to tasting chocolate milk were reduced post-RYGB. However, GLP-1R inhibition resulted in increased activation in the same areas, postulating a role for GLP-1R in reduced reward response to taste stimuli.95 Although data remain limited, studies utilising in-scan delivery of gustatory stimuli are beginning to provide key insights into the neural and endocrine substrates for taste changes observed after bariatric surgery. A prospective study of RYGB patients and non-obese controls showed reduced reward centre activation to taste post-RYGB. However, this study was not conclusive, as a similar reduction in BOLD signal was also observed in the control group.96 Cumulatively, these studies suggest a role for gut hormones in mediating the altered eating behaviour seen post-RYGB.

Interesting data are emerging regarding the effects of bariatric surgery upon brain structure and connectivity.101 Excitingly, a study into brain structure before and after SG suggested neuroplastic recovery 1month after surgery.98 In addition, a longitudinal study in RYGB showed weakened connectivity between areas controlling food intake and reward regions within 1 year from surgery and showed that connectivity in areas of emotional control and social interaction predicted weight loss.97 In conjunction, these findings imply that bariatric surgery restores obesity-related structural and connectivity abnormalities, which may relate to the changes in eating behaviour and the altered brain responses to food after bariatric surgery.

Novel medical management of obesity—future considerations

Bariatric surgery has brought about an unprecedented success in the management of people with severe obesity. Accessibility to surgery however is limited, calling for development of novel non-surgical approaches. The increasing knowledge of the biological changes engendered by bariatric surgery is catalysing a new era in the medical management of obesity, aiming to replicate the post-bariatric surgery milieu. For instance, the GLP-1R agonist liraglutide is now a licenced treatment for obesity in the United Kingdom. The data demonstrating synergistic action of gut peptides however are likely to lead to pharmacological approaches involving gut hormone combinations. fMRI studies have demonstrated the importance of food-cue responsivity in obesity pathogenesis, a finding likely to inspire therapeutic strategies tackling the motivational drive to eat.

Conclusion

In recent years, human neuroimaging studies have shown that eating behaviour is regulated by a complex network of homeostatic, reward and executive control brain regions interacting with peripheral signals of energy balance, the external environment and modulated by a person’s genetics. However, in order to develop effective weight management strategies, additional studies are now needed, focused upon delineating the impact of overweight, obesity, weight loss and bariatric surgery upon the CNS regions that regulate eating behaviour and, more importantly, the biological mediators of these changes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Roxanna Zakeri and Friedrich Jassil for their critical review of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Janine M Makaronidis, Email: j.makaronidis@ucl.ac.uk.

Rachel L Batterham, Email: r.batterham@ucl.ac.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. Obesity and overweight. Factsheet. 2017. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/

- 2.WHO. Global health observatory (GHO) data. 2016. Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/overweight_obesity/obesity_adults/en/

- 3.Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, Purcell K, Shulkes A, Kriketos A, et al. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 1597–604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med 2013; 273: 219–34. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathes CM, Spector AC. Food selection and taste changes in humans after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a direct-measures approach. Physiol Behav 2012; 107: 476–83. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neseliler S, Han JE, Dagher A. The use of functional magnetic resonance imaging in the study of appetite and obesity : Harris RBS, Appetite and food intake: central control. Boca Raton, FL: The British Institute of Radiology.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geha P, Cecchi G, Todd Constable R, Abdallah C, Small DM. Reorganization of brain connectivity in obesity. Hum Brain Mapp 2017; 38: 1403–20. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doornweerd S, van Duinkerken E, de Geus EJ, Arbab-Zadeh P, Veltman DJ, IJzerman RG. Overweight is associated with lower resting state functional connectivity in females after eliminating genetic effects: a twin study. Hum Brain Mapp 2017; 38: 5069–81. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.García-García I, Jurado MÁ, Garolera M, Marqués-Iturria I, Horstmann A, Segura B, et al. Functional network centrality in obesity: a resting-state and task fMRI study. Psychiatry Res 2015; 233: 331–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berthoud HR. Metabolic and hedonic drives in the neural control of appetite: who is the boss? Curr Opin Neurobiol 2011; 21: 888–96. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dokken BB, Tsao T-S. The physiology of body weight regulation: are we too efficient for our own good? Diabetes Spectrum 2007; 20: 166–70. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.20.3.166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Müller TD, Nogueiras R, Andermann ML, Andrews ZB, Anker SD, Argente J, et al. Ghrelin. Mol Metab 2015; 4: 437–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manning S, Batterham RL. The role of gut hormone peptide YY in energy and glucose homeostasis: twelve years on. Annu Rev Physiol 2014; 76: 585–608. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batterham RL, Cowley MA, Small CJ, Herzog H, Cohen MA, Dakin CL, et al. Gut hormone PYY3–36 physiologically inhibits food intake. Nature 2002; 418: 650–4. doi: 10.1038/nature00887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seeley RJ, Chambers AP, Sandoval DA. The role of gut adaptation in the potent effects of multiple bariatric surgeries on obesity and diabetes. Cell Metab 2015; 21: 369–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Browning KN, Fortna SR, Hajnal A. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass reverses the effects of diet-induced obesity to inhibit the responsiveness of central vagal motoneurones. J Physiol 2013; 591: 2357–72. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.249268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brighton CA, Rievaj J, Kuhre RE, Glass LL, Schoonjans K, Holst JJ, et al. Bile acids trigger GLP-1 release predominantly by accessing basolaterally located G protein-coupled bile acid receptors. Endocrinology 2015; 156: 3961–70. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zanchi D, Depoorter A, Egloff L, Haller S, Mählmann L, Lang UE, et al. The impact of gut hormones on the neural circuit of appetite and satiety: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017; 80: 457–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malik S, McGlone F, Bedrossian D, Dagher A. Ghrelin modulates brain activity in areas that control appetitive behavior. Cell Metab 2008; 7: 400–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstone AP, Prechtl CG, Scholtz S, Miras AD, Chhina N, Durighel G, et al. Ghrelin mimics fasting to enhance human hedonic, orbitofrontal cortex, and hippocampal responses to food. Am J Clin Nutr 2014; 99: 1319–30. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.075291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun X, Veldhuizen MG, Wray AE, de Araujo IE, Sherwin RS, Sinha R, et al. The neural signature of satiation is associated with ghrelin response and triglyceride metabolism. Physiol Behav 2014; 136: 63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Page KA, Seo D, Belfort-DeAguiar R, Lacadie C, Dzuira J, Naik S, et al. Circulating glucose levels modulate neural control of desire for high-calorie foods in humans. J Clin Invest 2011; 121: 4161–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI57873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Gao JH, Liu HL, Fox PT. The temporal response of the brain after eating revealed by functional MRI. Nature 2000; 405: 1058–62. doi: 10.1038/35016590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroemer NB, Krebs L, Kobiella A, Grimm O, Vollstädt-Klein S, Wolfensteller U, et al. (Still) longing for food: insulin reactivity modulates response to food pictures. Hum Brain Mapp 2013; 34: 2367–80. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallner-Liebmann S, Koschutnig K, Reishofer G, Sorantin E, Blaschitz B, Kruschitz R, et al. Insulin and hippocampus activation in response to images of high-calorie food in normal weight and obese adolescents. Obesity 2010; 18: 1552–7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grosshans M, Vollmert C, Vollstädt-Klein S, Tost H, Leber S, Bach P, et al. Association of leptin with food cue-induced activation in human reward pathways. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012; 69: 529–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Batterham RL, ffytche DH, Rosenthal JM, Zelaya FO, Barker GJ, Withers DJ, et al. PYY modulation of cortical and hypothalamic brain areas predicts feeding behaviour in humans. Nature 2007; 450: 106–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leidy HJ, Ortinau LC, Douglas SM, Hoertel HA. Beneficial effects of a higher-protein breakfast on the appetitive, hormonal, and neural signals controlling energy intake regulation in overweight/obese, "breakfast-skipping," late-adolescent girls. Am J Clin Nutr 2013; 97: 677–88. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.053116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Silva A, Salem V, Long CJ, Makwana A, Newbould RD, Rabiner EA, et al. The gut hormones PYY 3-36 and GLP-1 7-36 amide reduce food intake and modulate brain activity in appetite centers in humans. Cell Metab 2011; 14: 700–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Douglas SM, Lasley TR, Leidy HJ. Consuming beef vs. Soy protein has little effect on appetite, satiety, and food intake in healthy adults. J Nutr 2015; 145: 1010–6. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.206987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cummings DE. Taste and the regulation of food intake: it's not just about flavor. Am J Clin Nutr 2015; 102: 717–8. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.120667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simon JJ, Wetzel A, Sinno MH, Skunde M, Bendszus M, Preissl H, et al. Integration of homeostatic signaling and food reward processing in the human brain. JCI Insight 2017; 2. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.92970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loch D, Breer H, Strotmann J. Endocrine modulation of olfactory responsiveness: effects of the orexigenic hormone ghrelin. Chem Senses 2015; 40: 469–79. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjv028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroemer NB, Krebs L, Kobiella A, Grimm O, Pilhatsch M, Bidlingmaier M, et al. Fasting levels of ghrelin covary with the brain response to food pictures. Addict Biol 2013; 18: 855–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00489.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giuliani NR, Mann T, Tomiyama AJ, Berkman ET. Neural systems underlying the reappraisal of personally craved foods. J Cogn Neurosci 2014; 26: 1390–402. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hollmann M, Hellrung L, Pleger B, Schlögl H, Kabisch S, Stumvoll M, et al. Neural correlates of the volitional regulation of the desire for food. Int J Obes 2012; 36: 648–55. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez RB, Milyavskaya M, Hofmann W, Heatherton TF. Motivational and neural correlates of self-control of eating: a combined neuroimaging and experience sampling study in dieting female college students. Appetite 2016; 103: 192–9. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lean MEJ, Malkova D. Altered gut and adipose tissue hormones in overweight and obese individuals: cause or consequence? Int J Obes 2016; 40: 622–32. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenbaum M, Knight R, Leibel RL. The gut microbiota in human energy homeostasis and obesity. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2015; 26: 493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frank GK, Shott ME, Keffler C, Cornier MA. Extremes of eating are associated with reduced neural taste discrimination. Int J Eat Disord 2016; 49: 603–12. doi: 10.1002/eat.22538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Q, Jin R, Yu H, Lang H, Cui Y, Xiong S, et al. Enhancement of neural salty preference in obesity. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017; 43: 1987–2000. doi: 10.1159/000484122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maliphol AB, Garth DJ, Medler KF. Diet-induced obesity reduces the responsiveness of the peripheral taste receptor cells. PLoS One 2013; 8: e79403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shin AC, Townsend RL, Patterson LM, Berthoud HR. "Liking" and "wanting" of sweet and oily food stimuli as affected by high-fat diet-induced obesity, weight loss, leptin, and genetic predisposition. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2011; 301: R1267–R1280. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00314.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rissanen A, Hakala P, Lissner L, Mattlar CE, Koskenvuo M, Rönnemaa T. Acquired preference especially for dietary fat and obesity: a study of weight-discordant monozygotic twin pairs. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002; 26: 973–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barkeling B, King NA, Näslund E, Blundell JE. Characterization of obese individuals who claim to detect no relationship between their eating pattern and sensations of hunger or fullness. Int J Obes 2007; 31: 435–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gonzales MM, Tarumi T, Miles SC, Tanaka H, Shah F, Haley AP. Insulin sensitivity as a mediator of the relationship between BMI and working memory-related brain activation. Obesity 2010; 18: 2131–7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karlsson HK, Tuulari JJ, Hirvonen J, Lepomäki V, Parkkola R, Hiltunen J, et al. Obesity is associated with white matter atrophy: a combined diffusion tensor imaging and voxel-based morphometric study. Obesity 2013; 21: 2530–7. doi: 10.1002/oby.20386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu J, Li Y, Lin H, Sinha R, Potenza MN. Body mass index correlates negatively with white matter integrity in the fornix and corpus callosum: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Hum Brain Mapp 2013; 34: 1044–52. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.García-García I, Jurado MA, Garolera M, Segura B, Marqués-Iturria I, Pueyo R, et al. Functional connectivity in obesity during reward processing. Neuroimage 2013; 66: 232–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raji CA, Ho AJ, Parikshak NN, Becker JT, Lopez OL, Kuller LH, et al. Brain structure and obesity. Hum Brain Mapp 2010; 31: 353–64. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shott ME, Cornier MA, Mittal VA, Pryor TL, Orr JM, Brown MS, et al. Orbitofrontal cortex volume and brain reward response in obesity. Int J Obes 2015; 39: 214–21. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, Justice AE, Pers TH, Day FR, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 2015; 518: 197–206. doi: 10.1038/nature14177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maes HH, Neale MC, Eaves LJ. Genetic and environmental factors in relative body weight and human adiposity. Behav Genet 1997; 27: 325–51. doi: 10.1023/A:1025635913927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Panaro BL, Tough IR, Engelstoft MS, Matthews RT, Digby GJ, Møller CL, et al. The melanocortin-4 receptor is expressed in enteroendocrine L cells and regulates the release of peptide YY and glucagon-like peptide 1 in vivo. Cell Metab 2014; 20: 1018–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hardy R, Wills AK, Wong A, Elks CE, Wareham NJ, Loos RJ, et al. Life course variations in the associations between FTO and MC4R gene variants and body size. Hum Mol Genet 2010; 19: 545–52. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, Zeggini E, Freathy RM, Lindgren CM, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science 2007; 316: 889–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karra E, O'Daly OG, Choudhury AI, Yousseif A, Millership S, Neary MT, et al. A link between FTO, ghrelin, and impaired brain food-cue responsivity. J Clin Invest 2013; 123: 3539–51. doi: 10.1172/JCI44403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Dijk SJ, Molloy PL, Varinli H, Morrison JL, Muhlhausler BS, Members of EpiSCOPE. Epigenetics and human obesity. Int J Obes 2015; 39: 85–97. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stöger R. Epigenetics and obesity. Pharmacogenomics 2008; 9: 1851–60. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.12.1851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Filbey FM, Myers US, Dewitt S. Reward circuit function in high BMI individuals with compulsive overeating: similarities with addiction. Neuroimage 2012; 63: 1800–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.08.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pursey KM, Stanwell P, Callister RJ, Brain K, Collins CE, Burrows TL. Neural responses to visual food cues according to weight status: a systematic review of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Front Nutr 2014; 1: 7. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2014.00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stice E, Spoor S, Bohon C, Veldhuizen MG, Small DM. Relation of reward from food intake and anticipated food intake to obesity: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Abnorm Psychol 2008; 117: 924–35. doi: 10.1037/a0013600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hays NP, Roberts SB. Aspects of eating behaviors "disinhibition" and "restraint" are related to weight gain and BMI in women. Obesity 2008; 16: 52–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wardle J. Conditioning processes and cue exposure in the modification of excessive eating. Addict Behav 1990; 15: 387–93. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90047-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Connolly L, Coveleskie K, Kilpatrick LA, Labus JS, Ebrat B, Stains J, et al. Differences in brain responses between lean and obese women to a sweetened drink. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2013; 25: 579–e460. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rothemund Y, Preuschhof C, Bohner G, Bauknecht HC, Klingebiel R, Flor H, et al. Differential activation of the dorsal striatum by high-calorie visual food stimuli in obese individuals. Neuroimage 2007; 37: 410–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bohon C. Brain response to taste in overweight children: a pilot feasibility study. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0172604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fitzpatrick S, Gilbert S, Serpell L. Systematic review: are overweight and obese individuals impaired on behavioural tasks of executive functioning? Neuropsychol Rev 2013; 23: 138–56. doi: 10.1007/s11065-013-9224-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Szalay C, Aradi M, Schwarcz A, Orsi G, Perlaki G, Németh L, et al. Gustatory perception alterations in obesity: an fMRI study. Brain Res 2012; 1473: 131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.07.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun X, Veldhuizen MG, Babbs AE, Sinha R, Small DM. Perceptual and brain response to odors is associated with body mass index and postprandial total ghrelin reactivity to a meal. Chem Senses 2016; 41: 233–48. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjv081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kumar S, Grundeis F, Brand C, Hwang HJ, Mehnert J, Pleger B. Differences in insula and pre-/frontal responses during reappraisal of food in lean and obese humans. Front Hum Neurosci 2016; 10: 233. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leibel RL, Hirsch J. Diminished energy requirements in reduced-obese patients. Metabolism 1984; 33: 164–70. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(84)90130-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Formisano G, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2013. Obes Surg 2015; 25: 1822–32. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1657-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Buchwald H. The evolution of metabolic/bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2014; 24: 1126–35. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1354-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Odstrcil EA, Martinez JG, Santa Ana CA, Xue B, Schneider RE, Steffer KJ, et al. The contribution of malabsorption to the reduction in net energy absorption after long-limb Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 92: 704–13. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Coluzzi I, Raparelli L, Guarnacci L, Paone E, Del Genio G, le Roux CW, et al. Food intake and changes in eating behavior after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg 2016; 26: 2059–67. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-2043-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Laurenius A, Larsson I, Bueter M, Melanson KJ, Bosaeus I, Forslund HB, et al. Changes in eating behaviour and meal pattern following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Int J Obes 2012; 36: 348–55. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thomas JR, Marcus E. High and low fat food selection with reported frequency intolerance following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2008; 18: 282–7. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9336-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ullrich J, Ernst B, Wilms B, Thurnheer M, Schultes B. Roux-en Y gastric bypass surgery reduces hedonic hunger and improves dietary habits in severely obese subjects. Obes Surg 2013; 23: 50–5. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0754-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Graham L, Murty G, Bowrey DJ. Taste, smell and appetite change after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg 2014; 24: 1463–8. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1221-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Molin Netto BD, Earthman CP, Farias G, Landi Masquio DC, Grotti Clemente AP, Peixoto P, et al. Eating patterns and food choice as determinant of weight loss and improvement of metabolic profile after RYGB. Nutrition 2017; 33: 125–31. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tichansky DS, Boughter JD, Madan AK. Taste change after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2006; 2: 440–4. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Altun H, Hanci D, Altun H, Batman B, Serin RK, Karip AB, et al. Improved gustatory sensitivity in morbidly obese patients after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2016; 125: 536–40. doi: 10.1177/0003489416629162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Holinski F, Menenakos C, Haber G, Olze H, Ordemann J. Olfactory and gustatory function after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2015; 25: 2314–20. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1683-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jurowich CF, Seyfried F, Miras AD, Bueter M, Deckelmann J, Fassnacht M, et al. Does bariatric surgery change olfactory perception? Results of the early postoperative course. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014; 29: 253–60. doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1795-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Makaronidis JM, Neilson S, Cheung WH, Tymoszuk U, Pucci A, Finer N, et al. Reported appetite, taste and smell changes following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: effect of gender, type 2 diabetes and relationship to post-operative weight loss. Appetite 2016; 107: 93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yousseif A, Emmanuel J, Karra E, Millet Q, Elkalaawy M, Jenkinson AD, et al. Differential effects of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic gastric bypass on appetite, circulating acyl-ghrelin, peptide YY3-36 and active GLP-1 levels in non-diabetic humans. Obes Surg 2014; 24: 241–52. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1066-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Svane MS, Jørgensen NB, Bojsen-Møller KN, Dirksen C, Nielsen S, Kristiansen VB, et al. Peptide YY and glucagon-like peptide-1 contribute to decreased food intake after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Int J Obes 2016; 40: 1699–706. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pournaras DJ, Glicksman C, Vincent RP, Kuganolipava S, Alaghband-Zadeh J, Mahon D, et al. The role of bile after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in promoting weight loss and improving glycaemic control. Endocrinology 2012; 153: 3613–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-2145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nielsen S, Svane MS, Kuhre RE, Clausen TR, Kristiansen VB, Rehfeld JF, et al. Chenodeoxycholic acid stimulates glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion in patients after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Physiol Rep 2017; 5: e13140. doi: https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.13140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Manning S, Pucci A, Carter NC, Elkalaawy M, Querci G, Magno S, et al. Early postoperative weight loss predicts maximal weight loss after sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc 2015; 29: 1484–91. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3829-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Frank S, Heinze JM, Fritsche A, Linder K, von Feilitzsch M, Königsrainer A, et al. Neuronal food reward activity in patients with type 2 diabetes with improved glycemic control after bariatric surgery. Diabetes Care 2016; 39: 1311–7. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Faulconbridge LF, Ruparel K, Loughead J, Allison KC, Hesson LA, Fabricatore AN, et al. Changes in neural responsivity to highly palatable foods following roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or weight stability: an fMRI study. Obesity 2016; 24: 1054–60. doi: 10.1002/oby.21464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goldstone AP, Miras AD, Scholtz S, Jackson S, Neff KJ, Pénicaud L, et al. Link between increased satiety gut hormones and reduced food reward after gastric bypass surgery for obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016; 101: 599–609. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ten Kulve JS, Veltman DJ, Gerdes VEA, van Bloemendaal L, Barkhof F, Deacon CF, et al. Elevated postoperative endogenous GLP-1 levels mediate effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on neural responsivity to food cues. Diabetes Care 2017; 40: 1522–9. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang JL, Yang Q, Hajnal A, Rogers AM. A pilot functional MRI study in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients to study alteration in taste functions after surgery. Surg Endosc 2016; 30: 892–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4288-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Olivo G, Zhou W, Sundbom M, Zhukovsky C, Hogenkamp P, Nikontovic L, et al. Resting-state brain connectivity changes in obese women after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a longitudinal study. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 6616. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06663-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhang Y, Ji G, Xu M, Cai W, Zhu Q, Qian L, et al. Recovery of brain structural abnormalities in morbidly obese patients after bariatric surgery. Int J Obes 2016; 40: 1558–65. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ochner CN, Kwok Y, Conceição E, Pantazatos SP, Puma LM, Carnell S, et al. Selective reduction in neural responses to high calorie foods following gastric bypass surgery. Ann Surg 2011; 253: 502–7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318203a289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Scholtz S, Miras AD, Chhina N, Prechtl CG, Sleeth ML, Daud NM, et al. Obese patients after gastric bypass surgery have lower brain-hedonic responses to food than after gastric banding. Gut 2014; 63: 891–902. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tuulari JJ, Karlsson HK, Antikainen O, Hirvonen J, Pham T, Salminen P, et al. Bariatric surgery induces white and grey matter density recovery in the morbidly obese: a voxel-based morphometric study. Hum Brain Mapp 2016; 37: 3745–56. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]