Abstract

Current FDA-approved permanent female sterilization procedures are invasive and/or require the implantation of non-biodegradable materials. These techniques pose risks and complications, such as device migration, fracture, and tubal perforation. We propose a safe, non-invasive biodegradable tissue scaffold to effectively occlude the Fallopian tubes within 30 days of implantation. Specifically, the Fallopian tubes are mechanically de-epithelialized, and a tissue scaffold is placed into each tube. It is anticipated that this procedure can be performed in less than 30 minutes by an experienced obstetrics and gynaecology practitioner. Advantages of this method include the use of a fully bio-resorbable polymer, low costs, lower risks, and the lack of general anaesthesia. The scaffold devices are freeze-cast allowing for the custom-design of structural, mechanical, and chemical cues through material composition, processing parameters, and functionalization. The performance of the biomaterial and de-epithelialization procedure was tested in an in vivo rat uterine horn model. The scaffold response and tissue-biomaterial interactions were characterized microscopically post-implantation. Overall, the study resulted in the successful fabrication of resilient, easy-to-handle devices with an anisotropic scaffold architecture that encouraged rapid bio-integration through notable angiogenesis, cell infiltration, and native collagen deposition. Successful tubal occlusion was demonstrated at 30 days, revealing the great promise of a sterilization biomaterial.

INTRODUCTION

Female sterilization has attracted increased research interest over the last several decades [1]. Persistent efforts led to the development of multiple open surgical techniques to physically alter the Fallopian tubes and prevent fertilization [2]. The morbidity associated with these invasive approaches, however, results from infection risks, complications accompanying general anaesthesia, and difficult patient recovery/rehabilitation. Advances in laparoscopic, or minimally invasive, surgery have mitigated these drawbacks, albeit without eliminating them [1,3].

Recently, considerable advances in catheteral technologies have motivated transcervical female sterilization, because it eliminates the need for incisions or general anaesthesia [1,2]. Limited to only luminal or internal access to the Fallopian tubes, the general mechanism for permanent sterilization is the damaging of the tubal epithelium and connective tissue, followed by the proliferation of scar tissue that effectively and durably blocks the tubes. Attempts to damage the tubes typically fall into one or more of the following categories: mechanical, thermal, and chemical [3]. While chemical methods, such as sclerosing drugs and agents, have been pursued, they have not yet been translated into the clinic. Thermal methods, such as radiofrequency ablation, are not commercially available [1]. Lastly, a successful mechanical approach was achieved by a clinically available implant known as Essure®. This device consists of a shape memory nickel-titanium coil, which, when deployed, expands to cause tubal pressure and damage and is coupled with an inner PET (polyethylene terephthalate brush) for scar tissue irritation; the implants are placed bilaterally in each Fallopian tube and occlusion is achieved within three months [1,2,4]. While largely successful, complications in thousands of patients, including device migration, tubal perforation, and intraperitoneal damage, have in several cases necessitated hysterectomies and invasive surgery [1,5,6].

We have developed a new device that shows great promise for female sterilization. After mechanical de-epithelization of the tube, a novel biodegradable tissue scaffold manufactured by freeze casting is deposited to integrate cells and tissue. Freeze casting allows for the careful control over the structure and properties of a porous material, allowing for the custom design for a specific biomedical application [7–9]. To test our biomaterial in vivo, we have developed the rat uterine horn animal model. Characterization of the scaffold for preliminary assessments of our new methodology was performed with confocal microscopy and histopathology before and after implantation, respectively.

MATERIAL & METHODS

Scaffold manufacture

A 2% (w/v) collagen in 0.05 M acetic acid slurry was prepared from purified Type I bovine achilles tendon collagen (Advanced Biomatrix, Carlsbad, CA), swelled at 4°C, and homogenized (Fisher Scientific™ Homogenizer 152, Fisher Scientific International, Inc., Hampton, NH) for one hour on ice. Prior to freeze casting, the appropriate amount of stock solution was shear mixed (Speed Mixer™, DAC 150FVZ-K, FlackTek, Landrum, SC) and deposited into 4 mm cylindrical bores in a Teflon mold with a copper mold bottom via needle and syringe. After equilibrating the mold to 4°C, the slurry was cooled at a rate of 1°C/min until frozen with a standard freeze-casting system [7]. Samples were subsequently lyophilized at 0.008 mBar for at least 24 hours. Lyophilized scaffolds were gently stirred in 200 proof ethanol solution containing 33 mM 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) and 6 mM N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) for 6 hours. After crosslinking, samples were gently stirred in distilled water for 1, 12, and 1 hour washes; samples were palpated between each wash cycle to remove residual fluid. Samples were subsequently flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilized (Freezone 6 Plus, Labconco, Kansas City, MO) at 0.008 mBar for at least 24 hours. For the surgical implants, scaffolds were briefly soaked in distilled water, flash frozen, punched with a 2 mm biopsy punch, lyophilized, cut to length (4 mm), and sterilized with ethylene oxide.

Structural Characterization with Scanning Electron and Confocal Microscopy

Dry crosslinked scaffolds were sectioned, sputter coated, and imaged with a Tescan VEGA3 SEM (Tescan, Brno–Kohoutovice, Czech Republic). For imaging of fully hydrated scaffolds, pre-punched crosslinked scaffolds were briefly soaked in a 10 mg/mL fluorescein solution for 6 hours, followed by soaking in fresh distilled water for at least 18 additional hours (scaffolds were gently pressed to remove residual fluorescein prior to further soaking). Images were taken with a Nikon A1 Confocal Microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Surgery and Histology

All animal work was performed as approved by Dartmouth’s IACUC and was in accordance with the NIH’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Small incisions were made in the uterine horn(s) of anesthetized Lewis rats (2–3 months, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) followed by gentle mechanical de-epithelialization of the horn with a 1.5 mm stainless-steel micro brush (10–15 seconds). The scaffold was implanted distally (towards the ovary). Animals were humanely euthanized at the designated timepoint prior to uterine horn resection. Explanted uterine horns were fixed in formalin, sectioned, processed, microtomed, and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Optical micrographs were obtained with an Olympus BX50 transmission light microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and SPOT software.

RESULTS

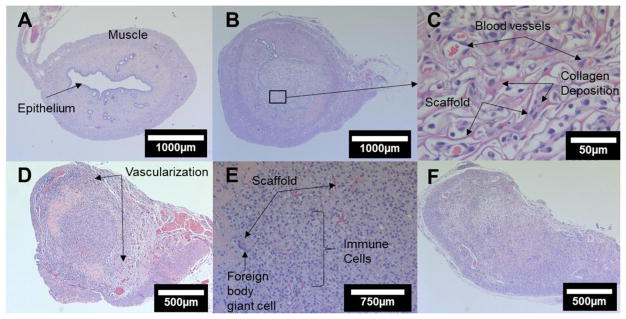

Scaffolds were imaged with a confocal microscope to reveal the microstructure in the fully hydrated state. The crosslinked samples were found to absorb fluid well and retain a resilient structure, while uncrosslinked samples were unable to conserve their macrostructure in the wet state. The transverse confocal micrographs (Figure 1) of the crosslinked Type I bovine collagen scaffold reveal a largely uniform pore size, structure, aspect ratio, and distribution.

Figure 1.

Confocal microscopy of the crosslinked collagen scaffold; (A) high and (B) low magnification transverse micrographs displaying longitudinal porosity.

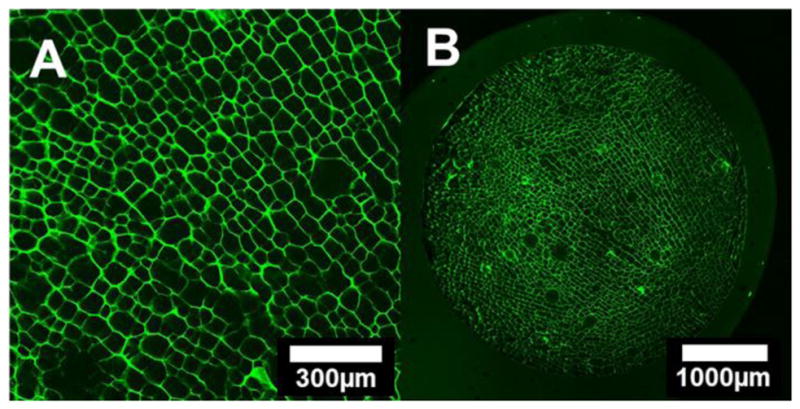

The pore size ranges from 50 to 80 μm in length. Directional pore alignment and fibrillar bridges along and between the pores are also visible (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(A) SEM micrograph of a longitudinal cross-section and (B) 3D transverse section confocal reconstruction (box dimensions: 1280 μm × 1280 μm × 330 μm) of the scaffold; anisotropic pore alignment and fibrillar bridges along and between pores are visible.

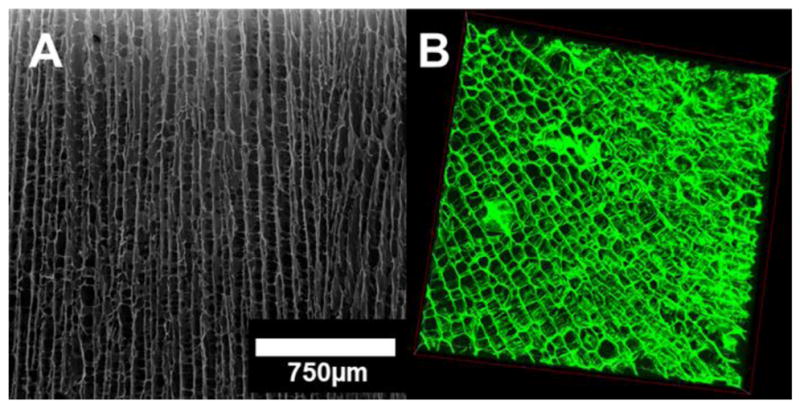

Histological examination of the scaffolds in situ in the rat uterine horn revealed considerable progression in the scaffold response from initial cell infiltration to tubal occlusion (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

H&E sections; A) untreated control horn; (B) low and (C) high magnification 6-day images displaying angiogenesis, immune cells, and collagen deposition; (D) low and (E) high magnification 12-day images with degrading scaffold material and immune cells; D) 30-day occluded horn.

The untreated control uterine horn (Figure 3A) displayed the typical epithelialized lumen, mucosal connective tissue and secretory glands, and two layers of muscles perpendicularly oriented to one another. Histopathology of the treated horns revealed that no uterine horns sustained a functional epithelium around the scaffold implant site at any of the timepoints (6, 12, or 30 days); importantly, secretory glandular tissue was visibly degenerating or absent. Angiogenesis and initial immune cell and fibroblast infiltration were visible at 6 days; collagenous deposits were also shown within the pores (Figure 3B&C). Significant tubal obstruction and peripheral vascularization was seen at 12 days (Figure 3D) with a degrading scaffold material present and a lumen filled with immune cells (Figure 3E). Lastly, at 30 days occlusion was apparent with low immune cell density and the presence of significant collagen deposition (Figure 3F).

DISCUSSION

Design of a biomaterial requires a thorough understanding of the in situ environment. The uterine horn, like the human Fallopian tube, is a moist tubal environment with dynamic fluid secretion and absorption and a virtual and corrugated lumen, requiring a conformable implant. An EDS-NHS crosslinked, porous collagen scaffold unlocked the functionalities of fluid absorption and resiliency to fill the uterine space without compaction of the porosity; these properties are a result of the covalent bonds formed through chemical crosslinking [10]. The conserved porosity was visible both under confocal microscopy (Figure 1A) and in situ (Figure 3B), validating that our structure is robust for this application. Tailoring of the mechanical properties and composition can further improve performance.

The longitudinal freeze casting technique was successful in manufacturing porous, resilient, and implantable structures for the cell integration in tubal tissue. While the anisotropy of the scaffold was expected to favour infiltration primarily along the pore alignment direction, the de-epithelialization for site preparation was designed to extend longer than the scaffold length to allow for cell proliferation into the material both from the ends and through the cylindrical surface. In addition, the open surface porosity of the scaffold could also facilitate the tissue-biomaterial interface. Areas for future investigation are an alternative pore size, alignment, and/or aspect ratio, which can be readily achieved through freeze casting [11]. Fibroblasts require an adequate and nearby blood supply to proliferate; this interplay includes tissue, cell, and protein interactions [12]. While notable angiogenesis and fibroplasia are visible throughout the different timepoints, tested in subsequent work will be scaffolds with more equiaxed or radial pore features to better facilitate cell and tissue integration both longitudinally (at the implant ends) and transversely (at the interface between the tubal interior and scaffold’s exterior surface). Longer timepoints will also need to be studied to better understand scar tissue formation and durability. Such investigations are predicted to improve integration and occlusion outcomes for this biomaterial approach. Lastly, the rat uterine horn was found to be an attractive model; the tubal tissue introduces sizing, anatomic, and morphological constraints, which are similar to those in the human Fallopian tube. While used in early sterility investigations [13], we have revived the model for tubal occlusion studies and demonstrated its promise for the translational testing and assessment of our freeze-cast biomaterial.

CONCLUSION

Recent failures in commercially available clinical devices for non-surgical permanent female sterilization have illustrated the need for a new biomaterial solution to achieve tubal occlusion. We have developed a biomaterial and procedure, utilizing simple tubal site preparation followed by a biodegradable freeze-cast collagen scaffold for integration of cells and tissue. Tubal occlusion in the in vivo rat uterine horn animal model was achieved in 30 days, demonstrating the great promise of the approach. Future work will be pursued to understand structure-property-processing correlations that will both help optimize the biomaterial for the desired application and support further investigations of the longer term in vivo outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge research support through NIH-NICHD award number R21HD087828. They thank Scott Paulisoul, David Beck, and Ann Lavanway for experimental assistance and the Thayer and Dartmouth College Electron Microscopy facilities, the Center for Comparative Medicine and Research, the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine, and Dartmouth’s Life Sciences Center. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Bartz D, Greenberg JA. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1(1):23–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman L, Magos A. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5(4):525–537. doi: 10.1586/17434440.5.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veersema S. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29(7):940–950. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer SN, Greenberg JA. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(2):84–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerritse MB, Veersema S, Timmermans A, Brölmann HA. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(3):930. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albright CM, Frishman GN, Bhagavath B. Contraception. 2013;88(3):334–336. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wegst UGK, Schecter M, Donius AE, Hunger PM. Philos Transact A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2010;368(1917):2099–2121. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2010.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wegst UGK, Bai H, Saiz E, Tomsia AP, Ritchie RO. Nat Mater. 2015;14(1):23–36. doi: 10.1038/nmat4089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Divakar P, Trembly BS, Moodie KL, Hoopes PJ, Wegst UGK. Proc SPIE. 2017;100066:100660A–1. doi: 10.1117/12.2255843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu X, Tang C, Xiong S, Yuan Q, Gu Z, Li Z, Hu Y. Curr Org Chem. 2016;20(17):1797–1812. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunger PM, Donius AE, Wegst UGK. Acta Biomat. 2013;9(5):6338–6348. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Assoian RK, Smith JM, Roche NS, Wakefield LM, Heine UI, Liotta LA, Falanga V, Kehrl JH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(12):4167–4171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaudhury RR, Tarak TK. Br Med J. 1965;1(5426):31. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5426.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]