Abstract

Anterior knee pain in active young adults is commonly related to patellofemoral pain syndrome, which can be broadly classified into patellar malalignment and patellar maltracking. Imaging is performed to further elucidate the exact malalignment and maltracking abnormalities and exclude other differentials. This article details the role of the stabilizers of the patellofemoral joint, findings on conventional and multimodality imaging aiding in patellofemoral pain syndrome diagnosis and characterization, and current perspectives of various treatment approaches.

Introduction

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is the most common cause of anterior knee pain in active young adults. PFPS is defined as anterior knee pain involving the patella, retinaculum and adjacent soft tissues, after excluding intra-articular pathology of the knee. It is a chronic disease caused by overuse and misuse, rather than acute trauma and is broadly classified into two categories, patellar malalignment and patellar maltracking.1 PFPS is a challenging diagnosis for clinicians and radiologists alike, and many differential considerations exist. Radiographic, CT and MRI evaluations are commonly employed to further elucidate the PFPS-related lesions2, 3 and exclude other related differential diagnoses, such as lateral meniscus tear, extensor tendon tear, anterior tenosynovial giant cell tumour and plica syndrome. This article comprehensively discusses the role of many static and dynamic stabilizers involved in the biomechanics of the PF joint, findings on conventional radiography and cross-sectional imaging that aids in the diagnosis and characterization of PFPS, and current perspectives of various management (conservative and surgical) approaches.

Anatomy and biomechanics

The patella is a sesamoid bone within the substance of the quadriceps tendon and acts as a fulcrum for the extensor mechanism of the knee joint, increasing the quadriceps power by 33–50%.4 Related to considerable load bearing capacity, patellar articular cartilage is the thickest in the body, measuring up to 4–6 mm in a young healthy adult. At rest, the upper three-fourth of the posterior patella articulates with the femoral trochlear sulcus while its contact area with trochlea changes throughout its range of motion. It rests laterally in full extension, engages in the trochlea at 30° of flexion, and moves more distally with increasing flexion. The lateral femoral condyle is larger than the medial condyle in anteroposterior (AP) dimensions, which prevents the lateral translation of the patella acting as a static stabilizer. Surrounding the patella, are three distinct fat pads (Hoffa’s, quadriceps, and pre-femoral fat pads) and three distinct bursae (pre-patellar, superficial infrapatellar and deep infrapatellar bursae). Anatomic and developmental variations of patellar shape and height are common and these include variations in size of patellar facets (Wiberg types), odd facet, which is an additional medial facet (innermost) that articulates with the femur beyond 120°,5 and inferior pole elongation.6 Bipartite patella represents an accessory ossicle, which may be present along its superolateral, inferior or medial borders. Generally, thicker the patellar facet, thicker the overlying cartilage. Therefore, the lateral facet (Wiberg Type II and III) usually has the thickest cartilage while odd facet exhibits the thinnest cartilage.

Patellar stability mainly relies on soft tissue constraints around the anterior knee. From 0 to 30° of flexion, the quadriceps tendon, the medial and lateral retinaculae, and the patellar tendon act as the static stabilizers, supported by vastus medialis obliquus muscle, which provides dynamic stability limiting the maltracking.7 The medial retinaculum has central thickenings, which are named according to structures they connect along its craniocaudal direction, i.e. the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL), medial patellomeniscal ligament and medial patellotibial ligament.7 The MPFL is the most important soft tissue static constraint to lateral displacement of the patella contributing about 53%.8 At >30° of flexion, the stability relies mainly on bony constraints.9 As the knee flexes, the primary restraint is the height and slope of the lateral femoral condyle. Increasing trochlear dysplasia is associated with lesser energy required for lateral dislocation of patella.10

Pathophysiology

The exact genesis of pain in PFPS is still unclear. The pain is hypothesized to be generated at the insertions of the extensor muscles, retinacula, Hoffa’s fat pad and subchondral bone.11–14

Central mechanisms may also contribute to pain in PFPS. A decreased pain threshold and abnormal sensory mechanisms have been found to play a role in pain genesis.15, 16

Psychological contributions to pain in PFPS such as high levels of mental stress, altered pain experience and coping mechanisms have also been shown to play an important role.17, 18

Secondary gain in underperforming young athletes has been identified as a causative factor.14

Patellofemoral disorders and clinical features

Patellofemoral (PF) malalignment refers to the relationship between the patella and the trochlear groove in the static position which is not centrally congruent, but becomes lateral or medial, or abnormally high or low position of the patella, namely patella alta and baja, respectively. PF maltracking refers to abnormal translation of the patella with respect to the trochlea on extension or flexion—similar to malalignment, but in a dynamic position. It usually occurs laterally due to the greater pull exerted by the quadriceps on the lateral aspect (tut vastus lateralis obliquus), but can sometimes be medial as well. PF impingement refers to abnormal contact of the patella with the femur leading to friction with the fat pads and subsequent cartilage loss. The most common height abnormalities are patella alta and baja.1, 2 Patella alta refers to a high-riding patella, which can be associated with lateral patellar subluxation and tilt, as the elongated patellar tendon allows increased mediolateral translational mobility and axial rotation of patella due to suboptimal engagement in the apex of trochlear sulcus. It also predisposes to chondromalacia patellae, stripping of patella along its anterior surface (enthesopathy) and patellar tendon rupture. A low-riding patella (patella baja) is seen in the settings of quadriceps tendon rupture, neuromuscular disorders, achondroplasia and after surgical realignment of the tibial tuberosity. The other abnormalities include excessive patellar tilt, painful bipartite patella, tight lateral retinaculum and excessively loose medial retinaculum.

The typical clinical presentation is an active young adult with gradual onset of anterior knee pain associated with a grinding sensation perceived on movement. The pain is often bilateral, usually more on one side, and is typically worsened by climbing or squatting activity, described by the patient “giving away or slipping”, which is due to the inhibition of the quadriceps.19 It is difficult to localize and the patient may just place their hand on the knee or circumscribe the patella, referred to as the circle sign.20 A locking or catching sensation after prolonged flexion of the knee (rising from a seated posture) is observed, referred to as the “movie theatre sign”.13, 21

On physical examination, one may identify several deformities, which can cause malalignment anatomy and PFPS. The typical “miserable malalignment syndrome” refers to the combination of internal rotation or antetorsion of the femur, “squinting” patellae which is due to femoral anteversion causing the patellae to point inwards, proximal tibial varus/external rotation, knee valgus and pes planus. Distal vastus medialis atrophy may be apparent.

The Q angle is the angle between the line joining the anterior superior iliac spine and the centre of the patella, and the second line joining the centre of the patella to the tibial tubercle. It can be measured both at flexion (15–20°) and extension, however, it may not be accurate in extension due to lateral patellar displacement. Traditionally measured with the patient supine and quadriceps relaxed, there has not yet been a standardization of the position and state of muscle contraction while measuring the Q angle.22, 23 It is an indicator of the net lateral force exerted on the patella by the quadriceps and the patellar tendon.24 Q angle of more than 14° in males and more than 17° in females suggests abnormal lateralization of the tibial tubercle.25, 26 Dynamic valgus may be observed on one-legged squats. Abnormal foot pronation and altered position of patella, as seen from side and front are helpful clues. The tubercle Sulcus angle can be measured with the patient sitting with knees flexed to 90°. A line perpendicular to the palpable transepicondylar axis is compared to line passing through the centre of the patella and tibial tubercle. An angle >10° is abnormal.

Radiological evaluation

Radiography (X-ray)

The initial evaluation typically involves standard AP and lateral views. AP view of both knees primarily evaluates the tibiofemoral joint but may show multipartite patella, gross patella alta and lateromedial subluxation. Patellar height is best assessed on the lateral view and qualitatively, the patellar height should approximate patellar tendon height. The commonly evaluated Insall-Salvati ratio (ISR) and Blackburne-Peel ratio are described in Table 127, 28 (Figures 1 and 2). An ISR ratio of >1.2 indicates alta and <0.8 indicates baja. Some literature suggests values of 1.5 and 0.74 respectively.28 The ISR does not account for variations in patellar morphology. To compensate for this, Grelsamer et al described a modified index in which the distance between the inferior articular surface of the patella and the patellar ligament insertion is divided by the length of the patella articular surface, and patella alta, with modified ISR, is defined as a ratio of >2.29 The Blackburne-Peel ratio similarly provides a better representation of the position of the patella and a ratio of >1.0 indicates alta and <0.8 indicates baja.27

Table 1.

Commonly used patellofemoral joint measurements

| Measurement | Normal value | Definitions |

| Insall-Salvati ratio | 0.8–1.2 | The ratio of the patellar tendon height (inferior pole of patella to middle to tibial tubercle notch) to the patellar height (oblique distance including the whole patella and exclusion of the osteophyte). |

| Blackburne-Peel ratio | 0.8–1.0 | The ratio of the distance measured from the inferior patellar articular surface to the horizontal line along the tibial plateau to the height of patellar articular surface. |

| Patellar tilt | <8° | The PF angle formed between the lines drawn along posterior condyles of the femur at the level of thickest trochlear cartilage and the lateral patellar facet. |

| Patellar subluxation | <2 mm | The lateral or medial displacement of the patella with respect to the trochlear groove, >2 mm distance between the margins of medial pole of patella and medial trochlear facet; or median ridge of patella with respect to apex of the trochlear sulcus. |

| Lateral trochlear inclination | >11° | The angle formed between the lines drawn along posterior condyles of the femur at the level of thickest trochlear cartilage and the lateral trochlear facet. |

| Trochlear depth | >3–5 mm | The depth of the trochlear groove, best measured at 3 cm above the tibial platue or at the femoral physeal scar. |

| TT–TG distance | <9 mm | Distance from centre of tibial tubercle to the apex of trochlear groove parallel to the tangential lines drawn through the posterior femoral condyle. |

| Sulcus angle | 138 ± 6° | The angle formed between the lines along the anterior tips of the medial and lateral femoral condyles to the deepest point of the intercondylar sulcus. |

TG, trochlear groove; TT, tibial tubercle.

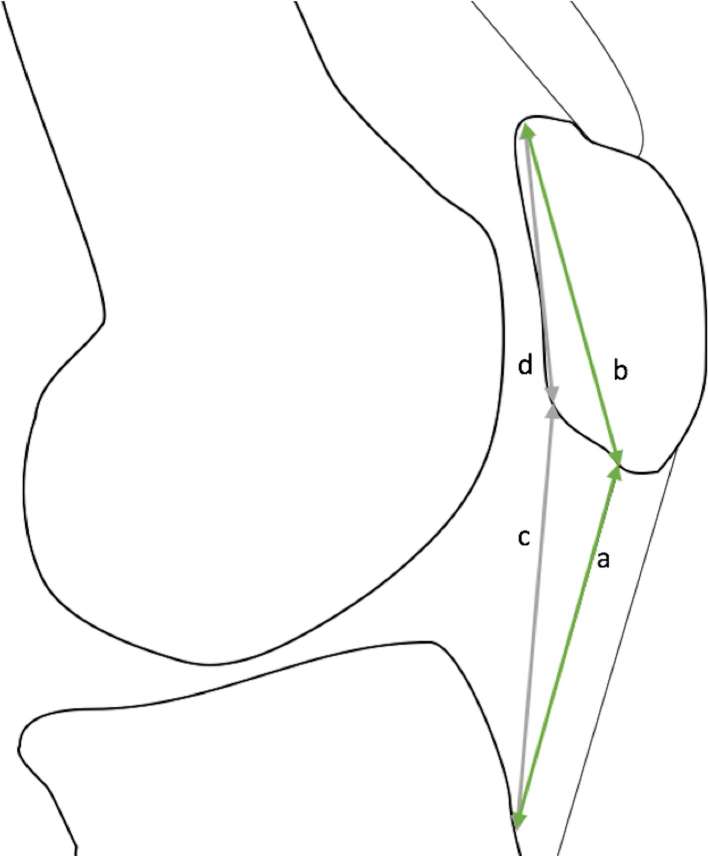

Figure 1.

Insall-Salvati ratio: patellar tendon length/patellar length (a/b). (c) Modified Insall-Salvati ratio: c/d. Normal value: 0.8–1.2.

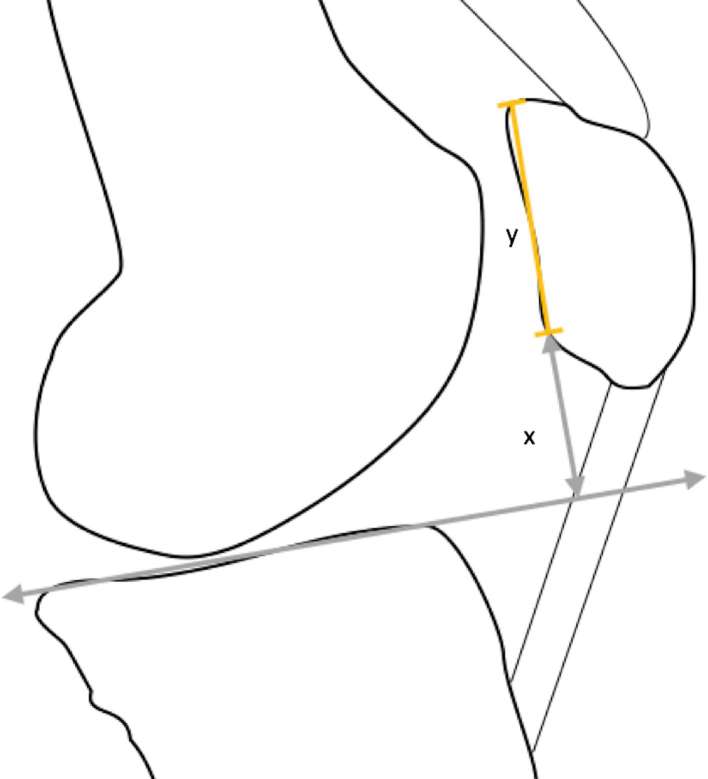

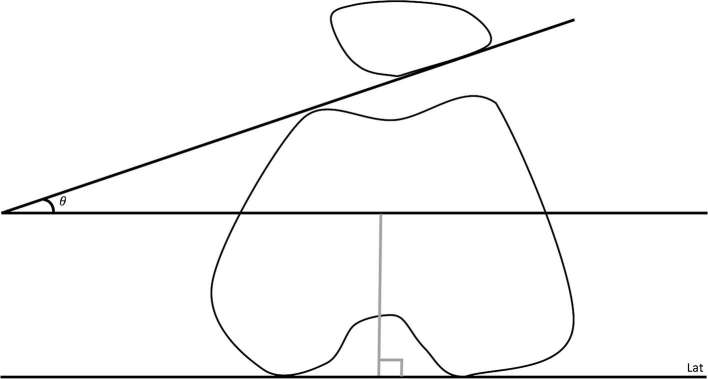

Figure 2.

Blackburne-Peel ratio: distance from the inferior patellar articular surface to the horizontal line along the tibial plateau/the height of patellar articular surface: x/y. Normal value: 0.8–1.0.

Axial radiograph of the PF joint shows patellar translation and axial rotation along with morphology of the trochlea. The Merchant view30 is obtained with the knee flexed at 45° and the X-ray beam aimed caudal 30° from the plane of the femur, making the positioning of X-ray tube easier and the technique more reproducible. It is also easier to perform in the obese or those with large tibial tubercles when other views may not be as informative. A standing, loaded Merchant view has been found to be superior in the evaluation of PFPS due to a more accurate representation of joint kinematics.31 Laurin view is obtained with the knee flexed at 20° and, even though difficult to obtain, detects not just severe abnormalities but also subtle changes in patellar tracking.32 Patellar translation measurement is described in Table 11, 33 and more than 2 mm is abnormal. The congruence angle is another less frequently used measurement to evaluate patellar translation. It is formed by a line drawn from the median ridge of the patella to the deepest point of the intercondylar sulcus and a line bisecting the trochlear sulcus angle.30 The angle lying towards the medial side is expressed as a negative, with the normal range being −8 to −14, and >14° suggests lateral subluxation of the patella. Patella can axially rotate especially with tight lateral retinaculum (aka excessive lateral pressure syndrome). Qualitatively, the patellar body and femur condyle should be parallel. The PF angle should open laterally and more than 8° is normal. With increasing patellar tilt, it becomes negative and opens medially.

Trochlear morphology affects PF joint stability. Shallow trochlear groove and/or prominent lateral ridge can result in malalignment.34 Qualitatively, a triangle of trochlear facets should be seen on axial view and the patella should fit within the apex of the trochlear sulcus. The lateral trochlear facet should not be more than 60% of the overall anterior trochlear articular width. While measurements of trochlear inclination and depth have been described (Table 1) (Figures 3 and 4), a simple measurement is the “sulcus angle”, drawn between the lines along the anterior margins of the trochlear facets to the deepest point of the intercondylar sulcus. The normal angle ranges from 138° ± 6°, and an angle measuring >144° indicates trochlear dysplasia.35 It allows greater reproducibility as it is reasonably insensitive to the angulation between the beam and the femur. A trochlear depth <3–5 mm also indicates dysplasia.33, 34

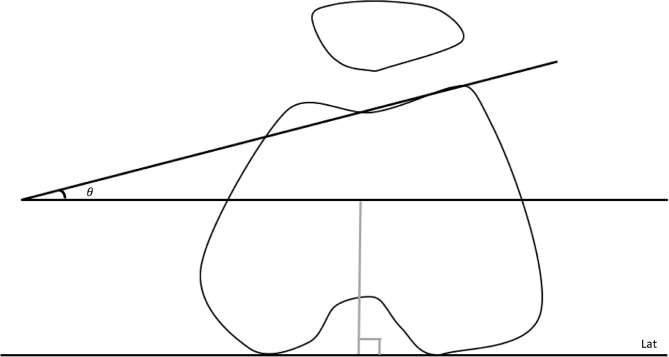

Figure 3.

Trochlear inclination: angle between the lines drawn along posterior condyles of the femur at the level of thickest trochlear cartilage and the lateral trochlear facet. Normal value: >11°.

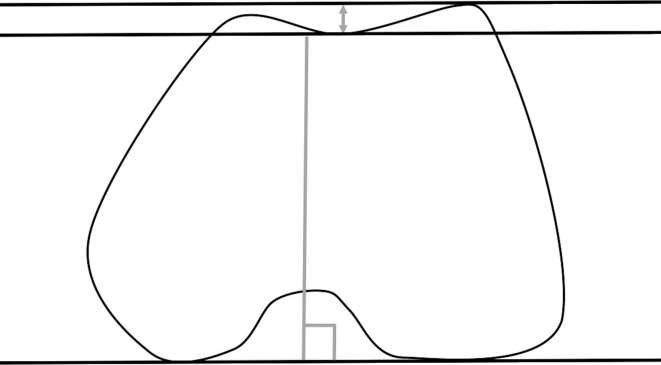

Figure 4.

Trochlear depth: the depth of the trochlear groove, best measured at 3 cm above the tibial platue or at the femoral physeal scar. Normal value: >3–5 mm.

When the patella becomes displaced only during active contraction, as in the case of mild to moderate maltracking, static X-rays often fail to diagnose it.36 As the degree of flexion decreases, skyline views become progressively more difficult to obtain and significant abnormalities may, therefore be overlooked.37 Thus, it has been suggested that the skyline view alone should not be used to make surgical decisions.38 Figure 5 shows various PF pathologies commonly seen on plain radiographs.

Figure 5.

X-ray demonstration of various patellofemoral and extensor compartment abnormalities. (a) Patella alta, (b) lateral patellar tilt, (c) inferior bipartite patella, (d) patellar dislocation, (e) quadriceps tear, (f) patellar tendon tear, (g) patellar dislocation with avulsion fracture and (h) patellar fractures.

Cross-sectional imaging

CT and MRI present multiple advantages over radiography and provide both static and dynamic data. Static CT and MR images allow evaluation of patellar and trochlear morphology and above described measurements on two-dimensional and three-dimensional scans, while MRI provides superior assessment of soft tissues including PF cartilage abnormalities, active anterior patellar enthesopathy, patellar and quadriceps tendinopathy/tears, retinacular assessment including MPFL integrity, friction-related superolateral and pre-patellar fat pad oedema (which is indicative of maltracking), and pre-patellar or deep infrapatellar bursitis39, 40 (Figures 6–8). MRI is also radiation free and allows evaluation of plica, lateral meniscus and other synovial abnormalities that can mimic symptoms of PFPS. For the required degrees of flexion, the back of the knee may be raised, or devices may be used to bring about passive flexed position. The axial radiograph typically evaluates the inferior portion of the trochlear groove, not where the high-riding patella would articulate. Therefore, trochlear morphology is best assessed on cross-sectional imaging. In addition, the surrogate marker of tibial tuberosity lateralization, i.e. Q angle is altered by the patient position, rotation of the limb and the degree of knee flexion. It is better and indirectly assessed on cross-sectional imaging using the tibial tubercle–trochlear groove (TT–TG) distance41, 42 which can be measured on both axial CT and MRI43, 44 (Figure 9). The normal TT–TG distance is <9mm, and >20 mm is considered indicative of symptomatic lateralization of tibial tubercle, where surgery can correct it.45 It is highly sensitive to the femoral alignment and femorotibial rotation, and errors in measurement are possible if the protocols for obtaining axial images are not standardized.46 MRI combines the accuracy of CT with the ability to visualize soft tissues and also directly depicts the articular cartilage lesions,1, 47 and can aid in individually tailored treatment plan.48 Post-operatively, MRI can be used to evaluate the status of the repaired tissue and complications (Figure 10).

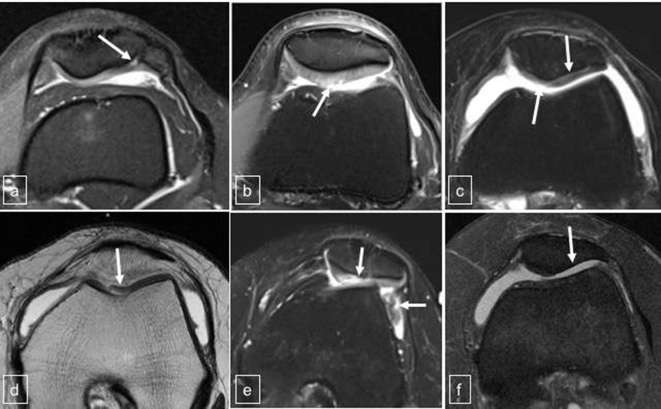

Figure 6.

Spectrum of patellar cartilage abnormalities on MRI. (a) Chondromalacia and bipartite patella, (b) cartilage fissures and small defects, (c) large cartilage lap, (d) delamination, (e) large full-thickness defect with cartilage fragments in lateral gutter and (f) complete denudation.

Figure 7.

MRI of extensor mechanism abnormalities leading to PFPS. (a) Jumper’s knee with patellar tendon tear, (b) chronic tendinopathy, (c) symptomatic bipartite patella, (d) acute on chronic enthesopathy, (e) quadriceps fat pad oedema, (f) superolateral and pre-femoral fat pad oedema. PFPS, patellofemoral pain syndrome.

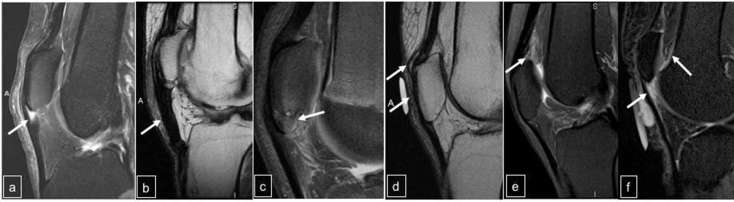

Figure 8.

MRI of vastus medialis and patellar retinaculum pathologies. (a) Axial T1W image showing vastus medialis atrophy (arrow), (b) Axial T2W fat suppressed image showing MPFL tear from the patella (arrow), (c) Axial T2W image showing MPFL tear from femur (arrow), (d) Axial T1W image showing subacute MPFL tear with haematoma. MPFL, medial patellofemoral ligament.

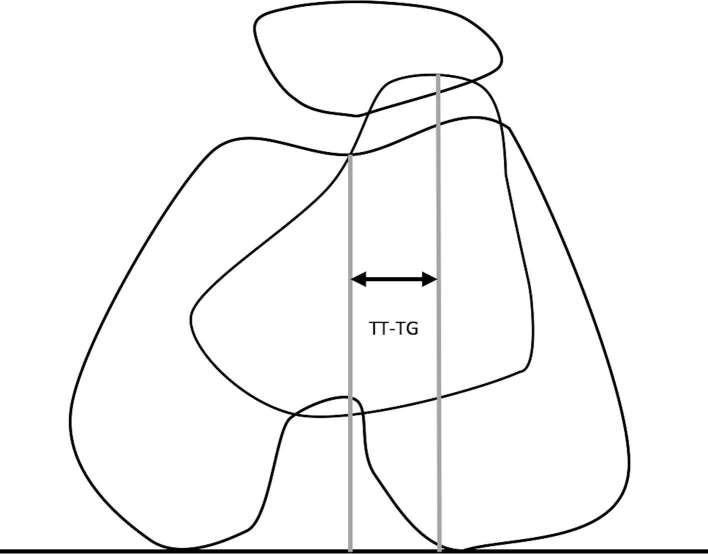

Figure 9.

TT–TG distance: distance from centre of tibial tubercle to the apex of trochlear groove parallel to the tangential lines drawn through the posterior femoral condyle. Normal value: <9 mm

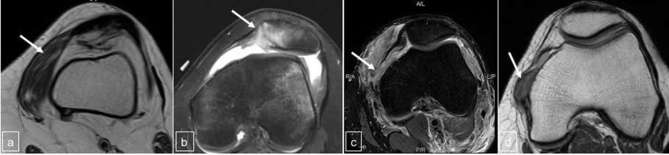

Figure 10.

Spectrum of post-surgical changes related to patellofemoral compartment. (a) Lateral retinacular release, (b) patellectomy, (c) patellar tendon repair with small post-operative ossification, (d) quadriceps tendon repair with remodelling.

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Drew et al, certain imaging findings were shown to have a higher correlation with PFPS than others, namely, an increase in the CT congruence angle, both weighted and non-weighted, when measured at 15° flexion and an increase in the MRI bisect offset when measured under load and with no flexion.49 Lankhorst et al concluded that PFPS patients exhibit a larger Q angle, sulcus angle and patellar tilt angle (Figure 11).50

Figure 11.

Patellar tilt: angle between the lines drawn along posterior condyles of the femur at the level of thickest trochlear cartilage and the lateral patellar facet. Normal value: <8°

Dynamic imaging

Static imaging does not evaluate the effect of active muscle contraction on the patellar position, expected during knee movements. Dynamic imaging allows assessment of the PF joint kinematics and evaluation of real-time interplay of soft tissue and bony constraints.2, 51,52 However, due to the needed technical expertize and time limitations, dynamic imaging is not routine. It is generally employed to investigate suspected patellar maltracking in patients with PFPS symptoms without, otherwise, evident anatomic malalignment. It is also used to assess subclinical patellar subluxation and the impact of treatment in patients with recurrent subluxations.53 This method requires a good degree of patient compliance and the examination may not be possible in patients with severe pain. Kinematic MRI using gradient echo or steady-state sequences using a surface coil can produce the desired T1W or T2W contrasts, respectively, and these techniques can produce 3–6 images per second, which can easily capture PF kinematics while patient actively flexes and extends the knee in the MR gantry.54 Four-dimensional CT (4DCT) can show similar motion where three-dimensional CT volume acquisitions of the knee are performed during flexion–extension motions. Typically, a 256-slice multidetector CT can generate 16-cm long field of view. Four-dimensional CT has been shown to be feasible in evaluation of PF joint for altered biomechanics and risk stratification for development of osteoarthritis2 (Figure 12). However, it involves radiation exposure as opposed to MRI. It remains to be seen, whether widespread use of these advanced techniques can improve patient outcomes.

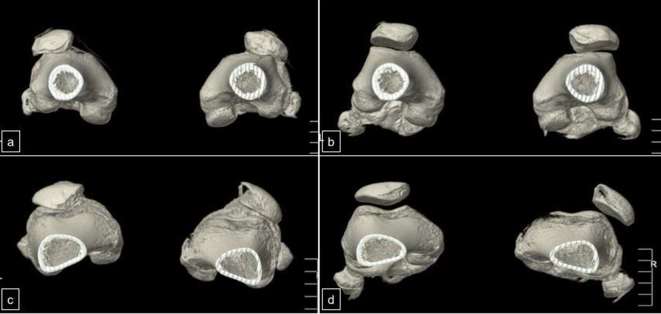

Figure 12.

4DCT of Knee with cine captures showing patellar maltracking. Patient 1: (a) extended position showing bilateral patellar tilt and subluxation, (b) flexed position showing near normal alignment, right > left. Patient 2: (c) extended position showing bilateral patellar tilt and subluxation, (d) flexed position showing near normal alignment of the right knee, and further patellar dislocation of the left knee. 4DCT, four-dimensional CT.

Treatment

The aim of treatment is to address various underlying factors contributing to the patient’s symptoms and restore dynamic balance, thereby correcting the improper kinematics and alignment. The treatments are divided into conservative and surgical approaches. Conservative treatment for 3–6 months is the management of choice in the initial stages, but failure of conservative management may necessitate the surgical management.

Conservative treatment

Patients with PFPS may demonstrate lower hip abduction and external rotation strength, and lower peak knee extension torque.50 Conservative treatment options for patients with PFPS include improving the lower extremity biomechanics and modifying lifestyle through enhancing flexibility, correcting gait and retraining with proper techniques and adequate rest, all of which necessitate sufficient pain control.55, 56 Quadriceps strengthening program is a common rehabilitation technique, which attempts to strengthen the knee extension weakness and has consistently been shown to aid in improvement.57 The vastus medialis, particularly obliquous, draws a lot of attention due to its role in the medial stabilization of the patella. There is some evidence that selective muscle strengthening resolves pain and improves knee function, and is also helpful to prevent relapses.58 However, it has largely been agreed upon that overall quadriceps strengthening shows no difference in the short-term outcomes.56, 57,59 Patellar taping (McConnell method) aims to control the patellar tilt, glide and/or spin, and causes an inferolateral PF shift leading to wider distribution of forces.60, 61 Braces and orthotics are all regarded as adjuvant to PF rehabilitation and quadriceps strengthening. Patellar stabilizing bracing is best used in the “maltracking” patients.62 Semi-rigid foot orthotics absorb shock and provide medial longitudinal arch support leading to pain reduction and improved functional performance.63 Lower baseline functional scores, increased midfoot mobility, reduced ankle dorsiflexion and the use of less supportive shoes are all predictors of positive response with the use of orthotics.63, 64 Cryotherapy, ultrasound, phonophoresis, iontophoresis, neuromuscular electrical stimulation etc. for pain control have been not been found to have any significant benefit in PFPS.65 Patients with unilateral symptoms, low body height and young age tend to respond better to the conservative treatments.66

Surgical treatment

Surgical treatment may be considered when there is a clear identifiable or correctable lesion and if the patient exhibits no improvement after strict adherence to conservative therapy for >6 months. A “tool-box” approach is typically followed with treatment tailored as per every individual patient’s needs, which, along with patient selection, is important to ensure a successful outcome with minimum complications. To consider surgery, one of the following documented findings must be present apart from failure of conservative management: malalignment (abnormal Q angle or increased TT–TG distance), tight lateral retinaculum (patellar tilt/translation), or articular cartilage lesions. Arthroscopy is used prior to the definitive procedures to localize and quantify chondral lesions, isolate and debride chondral flaps, identify and resect plica, and to rule out other intra-articular pathologies. Lateral release is indicated for truly tight and symptomatic lateral retinaculum (lateral patellar compression syndrome). While technically simple, it has gradually fallen out of favour as an isolated procedure as it does not produce lasting effects.67 Tibial tubercle realignment is a more favoured procedure in skeletally mature patients to offload the lateral PF joint and different techniques exist (Table 2).68–71

Table 2.

Tibial tubercle realignment procedures

| Procedure | Direction of TT transfer | Result | Remarks |

| Elmslie-Trillat–transverse osteotomy | Medial | Restores TT–TG | Contraindications: medial facet chondral injury, varus knee, medial compartment OA, medial meniscectomy |

| Maquet-Long transverse osteotomy, using bone graft | Anterior | Unloads PF joint | Suited for: PFPS, OA |

| Fulkerson–oblique osteotomy | Anterior + medial | Combined | Suited for: PF instability with lateral/distal chondral injuries |

| Hauser (historical) | Posterior + medial | Overloads PF joint Due to posterior displacement |

In symptomatic patients with an insufficient MPFL, it can be reconstructed by multiple techniques. However, some controversies do exist regarding graft selection, fixation, position and tension and there is, yet, no consensus on the best approach. Fixation of auto- or allograft to the patella is the main challenge, which can be done by sutures, suture anchors or bone tunnels. Anatomic placement of the graft is ideal. A recent systemic review identified the complication rate of MPFL reconstruction at 26.1%. The major complications were patellar fracture, postoperative instability, flexion loss and persistent pain.72

Conclusion

Anterior knee pain due to PFPS is a common problem among the young. Its definitive diagnosis and treatment are challenging due to the complex interplay of multiple anatomical and developmental variations. Good clinical and radiological evaluation is integral to its management and the treatment must be individualized to the patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the clinical insight provided by Dr Katherine Coyner with respect to pathophysiology of patellofemoral pain disorders.

Contributor Information

Aishwarya Gulati, Email: aish1313@gmail.com.

Christopher McElrath, Email: Christopher.McElrath@utsouthwestern.edu.

Vibhor Wadhwa, Email: vibhorwadhwa90@gmail.com.

Jay P Shah, Email: Jay.Shah@utsouthwestern.edu.

Avneesh Chhabra, Email: avneesh.chhabra@utsouthwestern.edu.

Disclosures

AC: Consultant ICON Medical, Royalties: Jaypee, Wolters.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chhabra A, Subhawong TK, Carrino JA. A systematised MRI approach to evaluating the patellofemoral joint. Skeletal Radiol 2011; 40: 375–87. doi: 10.1007/s00256-010-0909-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demehri S, Thawait GK, Williams AA, Kompel A, Elias JJ, Carrino JA, et al. Imaging characteristics of contralateral asymptomatic patellofemoral joints in patients with unilateral instability. Radiology 2014; 273: 821–30. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas S, Rupiper D, Stacy GS. Imaging of the patellofemoral joint. Clin Sports Med 2014; 33: 413–36. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2014.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufer H. Mechanical function of the patella. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1971; 53: 1551–60. doi: 10.2106/00004623-197153080-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mihalko WM, Boachie-Adjei Y, Spang JT, Fulkerson JP, Arendt EA, Saleh KJ. Controversies and techniques in the surgical management of patellofemoral arthritis. Instr Course Lect 2008; 57: 365–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wibeeg G. Roentgenographs and anatomic studies on the femoropatellar joint: with special reference to chondromalacia patellae. Acta Orthop Scand 1941; 12: 319–410. doi: 10.3109/17453674108988818 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panagiotopoulos E, Strzelczyk P, Herrmann M, Scuderi G. Cadaveric study on static medial patellar stabilizers: the dynamizing role of the vastus medialis obliquus on medial patellofemoral ligament. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2006; 14: 7–12. doi: 10.1007/s00167-005-0631-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conlan T, Garth WP, Lemons JE. Evaluation of the medial soft-tissue restraints of the extensor mechanism of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993; 75: 682–93. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199305000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farahmand F, Naghi Tahmasbi M, Amis A. The contribution of the medial retinaculum and quadriceps muscles to patellar lateral stability--an in-vitro study. Knee 2004; 11: 89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2003.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farr J. Distal realignment for recurrent patellar instability. Oper Tech Sports Med 2001; 9: 176–82. doi: 10.1053/otsm.2001.25168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wojtys EM, Beaman DN, Glover RA, Janda D. Innervation of the human knee joint by substance-P fibers. Arthroscopy 1990; 6: 254–63. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(90)90054-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchis-Alfonso V, Roselló-Sastre E. Immunohistochemical analysis for neural markers of the lateral retinaculum in patients with isolated symptomatic patellofemoral malalignment. A neuroanatomic basis for anterior knee pain in the active young patient. Am J Sports Med 2000; 28: 725–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dye SF. The pathophysiology of patellofemoral pain: a tissue homeostasis perspective. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005; 436: 100–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petersen W, Ellermann A, Gösele-Koppenburg A, Best R, Rembitzki IV, Brüggemann GP, et al. Patellofemoral pain syndrome. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014; 22: 2264–74. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2759-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen R, Hystad T, Baerheim A. Knee function and pain related to psychological variables in patients with long-term patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2005; 35: 594–600. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2005.35.9.594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rathleff MS, Roos EM, Olesen JL, Rasmussen S, Arendt-Nielsen L. Lower mechanical pressure pain thresholds in female adolescents with patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2013; 43: 414–21. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2013.4383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomeé P, Thomeé R, Karlsson J. Patellofemoral pain syndrome: pain, coping strategies and degree of well-being. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2002; 12: 276–81. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2002.10226.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen R, Hystad T, Kvale A, Baerheim A. Quantitative sensory testing of patients with long lasting patellofemoral pain syndrome. Eur J Pain 2007; 11: 665–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Post WR. Clinical evaluation of patients with patellofemoral disorders. Arthroscopy 1999; 15: 841–51. doi: 10.1053/ar.1999.v15.015084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dixit S, DiFiori JP, Burton M, Mines B. Management of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Am Fam Physician 2007; 75: 194–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heintjes E, Berger MY, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Bernsen RM, Verhaar JA, Koes BW. Pharmacotherapy for patellofemoral pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; 3: CD003470. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003470.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guerra JP, Arnold MJ, Gajdosik RL. Q angle: effects of isometric quadriceps contraction and body position. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1994; 19: 200–4. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1994.19.4.200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez HM, Sanchez EG, Baraúna MA, Canto RS. Evaluation of Q angle in differents static postures. Acta Ortop Bras 2014; 22: 325–9. doi: 10.1590/1413-78522014220600451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mizuno Y, Kumagai M, Mattessich SM, Elias JJ, Ramrattan N, Cosgarea AJ, et al. Q-angle influences tibiofemoral and patellofemoral kinematics. J Orthop Res 2001; 19: 834–40. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00008-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brattström H. Patella alta in non-dislocating knee joints. Acta Orthop Scand 1970; 41: 578–88. doi: 10.3109/17453677008991549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aglietti P, Insall JN, Cerulli G. Patellar pain and incongruence. I: measurements of incongruence. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1983; 176: 217–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berg EE, Mason SL, Lucas MJ. Patellar height ratios. A comparison of four measurement methods. Am J Sports Med 1996; 24: 218–21. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shabshin N, Schweitzer ME, Morrison WB, Parker L. MRI criteria for patella alta and baja. Skeletal Radiol 2004; 33: 445–50. doi: 10.1007/s00256-004-0794-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grelsamer RP, Meadows S. The modified insall-salvati ratio for assessment of patellar height. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992; 282: 170–6. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199209000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merchant AC, Mercer RL, Jacobsen RH, Cool CR. Roentgenographic analysis of patellofemoral congruence. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1974; 56: 1391–6. doi: 10.2106/00004623-197456070-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim TH, Sobti A, Lee SH, Lee JS, Oh KJ. The effects of weight-bearing conditions on patellofemoral indices in individuals without and with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Skeletal Radiol 2014; 43: 157–64. doi: 10.1007/s00256-013-1756-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laurin CA, Dussault R, Levesque HP. The tangential X-ray investigation of the patellofemoral joint: X-ray technique, diagnostic criteria and their interpretation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1979; 144: 16–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elias DA, White LM. Imaging of patellofemoral disorders. Clin Radiol 2004; 59: 543–57. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2004.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfirrmann CW, Zanetti M, Romero J, Hodler J. Femoral trochlear dysplasia: MR findings. Radiology 2000; 216: 858–64. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00se38858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davies AP, Costa ML, Shepstone L, Glasgow MM, Donell S, Donnell ST. The sulcus angle and malalignment of the extensor mechanism of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000; 82: 1162–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.82B8.10833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muhle C, Brossmann J, Heller M. Functional MRI of the femoropatellar joint. Radiologe 1995; 35: 117–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skalley TC, Terry GC, Teitge RA. The quantitative measurement of normal passive medial and lateral patellar motion limits. Am J Sports Med 1993; 21: 728–32. doi: 10.1177/036354659302100517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker C, Cassar-Pullicino VN, Vaisha R, McCall IW. The patello-femoral joint--a critical appraisal of its geometric assessment utilizing conventional axial radiography and computed arthro-tomography. Br J Radiol 1993; 66: 755–61. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-66-789-755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conway WF, Hayes CW, Loughran T, Totty WG, Griffeth LK, el-Khoury GY, et al. Cross-sectional imaging of the patellofemoral joint and surrounding structures. Radiographics 1991; 11: 195–217. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.11.2.2028059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McNally EG, Ostlere SJ, Pal C, Phillips A, Reid H, Dodd C. Assessment of patellar maltracking using combined static and dynamic MRI. Eur Radiol 2000; 10: 1051–5. doi: 10.1007/s003300000358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dejour H, Walch G, Nove-Josserand L, Guier C. Factors of patellar instability: an anatomic radiographic study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 1994; 2: 19–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01552649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balcarek P, Jung K, Frosch KH, Stürmer KM. Value of the tibial tuberosity-trochlear groove distance in patellar instability in the young athlete. Am J Sports Med 2011; 39: 1756–62. doi: 10.1177/0363546511404883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saudan M, Fritschy D. AT-TG (anterior tuberosity-trochlear groove): interobserver variability in CT measurements in subjects with patellar instability. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 2000; 86: 250–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hinckel BB, Gobbi RG, Filho EN, Pécora JR, Camanho GL, Rodrigues MB, et al. Are the osseous and tendinous-cartilaginous tibial tuberosity-trochlear groove distances the same on CT and MRI? Skeletal Radiol 2015; 44: 1085–93. doi: 10.1007/s00256-015-2118-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tecklenburg K, Feller JA, Whitehead TS, Webster KE, Elzarka A. Outcome of surgery for recurrent patellar dislocation based on the distance of the tibial tuberosity to the trochlear groove. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92: 1376–80. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B10.24439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yao L, Gai N, Boutin RD. Axial scan orientation and the tibial tubercle-trochlear groove distance: error analysis and correction. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014; 202: 1291–6. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wittstein JR, Bartlett EC, Easterbrook J, Byrd JC. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of patellofemoral malalignment. Arthroscopy 2006; 22: 643–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diederichs G, Issever AS, Scheffler S. MR imaging of patellar instability: injury patterns and assessment of risk factors. Radiographics 2010; 30: 961–81. doi: 10.1148/rg.304095755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drew BT, Redmond AC, Smith TO, Penny F, Conaghan PG. Which patellofemoral joint imaging features are associated with patellofemoral pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016; 24: 224–36. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lankhorst NE, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, van Middelkoop M. Factors associated with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2013; 47: 193–206. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mariani S, La Marra A, Arrigoni F, Necozione S, Splendiani A, Di Cesare E, et al. Dynamic measurement of patello-femoral joint alignment using weight-bearing magnetic resonance imaging (WB-MRI). Eur J Radiol 2015; 84: 2571–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tanaka MJ, Elias JJ, Williams AA, Demehri S, Cosgarea AJ. Characterization of patellar maltracking using dynamic kinematic CT imaging in patients with patellar instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2016; 24: 3634–41. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4216-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muhle C, Brossmann J, Heller M. Kinematic CT and MR imaging of the patellofemoral joint. Eur Radiol 1999; 9: 508–18. doi: 10.1007/s003300050702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borotikar BS, Sheehan FT. In vivo patellofemoral contact mechanics during active extension using a novel dynamic MRI-based methodology. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013; 21: 1886–94. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Powers CM. Rehabilitation of patellofemoral joint disorders: a critical review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1998; 28: 345–54. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.5.345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dutton RA, Khadavi MJ, Fredericson M. Update on rehabilitation of patellofemoral pain. Curr Sports Med Rep 2014; 13: 172–8. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Syme G, Rowe P, Martin D, Daly G. Disability in patients with chronic patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomised controlled trial of VMO selective training versus general quadriceps strengthening. Man Ther 2009; 14: 252–63. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2008.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramazzina I, Pogliacomi F, Bertuletti S, Costantino C. Long term effect of selective muscle strengthening in athletes with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Acta Biomed 2016; 87(Suppl 1): 60–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dursun N, Dursun E, Kiliç Z. Electromyographic biofeedback-controlled exercise versus conservative care for patellofemoral pain syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 82: 1692–5. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.26253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Derasari A, Brindle TJ, Alter KE, Sheehan FT. McConnell taping shifts the patella inferiorly in patients with patellofemoral pain: a dynamic magnetic resonance imaging study. Phys Ther 2010; 90: 411–9. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barton C, Balachandar V, Lack S, Morrissey D. Patellar taping for patellofemoral pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate clinical outcomes and biomechanical mechanisms. Br J Sports Med 2014; 48: 417–24. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arazpour M, Notarki TT, Salimi A, Bani MA, Nabavi H, Hutchins SW. The effect of patellofemoral bracing on walking in individuals with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Prosthet Orthot Int 2013; 37: 465–70. doi: 10.1177/0309364613476535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barton CJ, Menz HB, Crossley KM. Effects of prefabricated foot orthoses on pain and function in individuals with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a cohort study. Phys Ther Sport 2011; 12: 70–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2010.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vicenzino B, Collins N, Cleland J, McPoil T. A clinical prediction rule for identifying patients with patellofemoral pain who are likely to benefit from foot orthoses: a preliminary determination. Br J Sports Med 2010; 44: 862–6. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.052613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lake DA, Wofford NH. Effect of therapeutic modalities on patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review. Sports Health 2011; 3: 182–9. doi: 10.1177/1941738111398583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Natri A, Kannus P, Järvinen M. Which factors predict the long-term outcome in chronic patellofemoral pain syndrome? A 7-yr prospective follow-up study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998; 30: 1572–7. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199811000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clifton R, Ng CY, Nutton RW. What is the role of lateral retinacular release? J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92: 1–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B1.22909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karamehmetoğlu M, Oztürkmen Y, Azboy I, Caniklioğlu M. Fulkerson osteotomy for the treatment of chronic patellofemoral malalignment. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2007; 41: 21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sherman SL, Erickson BJ, Cvetanovich GL, Chalmers PN, Farr J, Bach BR, et al. Tibial tuberosity osteotomy: indications, techniques, and outcomes. Am J Sports Med 2014; 42: 2006–17. doi: 10.1177/0363546513507423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grawe B, Stein BE. Tibial tubercle osteotomy: indication and techniques. J Knee Surg 2015; 28: 279–84. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1544973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Maugans CJ, Scuderi MG, Werner FW, Haddad SF, Cannizzaro JP. Tibial tubercle osteotomy: a biomechanical comparison of two techniques. Knee 2017; 24: 264–70. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2016.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shah JN, Howard JS, Flanigan DC, Brophy RH, Carey JL, Lattermann C. A systematic review of complications and failures associated with medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction for recurrent patellar dislocation. Am J Sports Med 2012; 40: 1916–23. doi: 10.1177/0363546512442330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]