Abstract

A lack of well-trained clinical oncologists can result in significant cancer health disparities. The magnitude of this problem around the world is poorly described in the literature. A comprehensive global survey of the clinical oncology workforce was conducted. Data on the number of clinical oncologists in 93 countries were obtained from 30 references. The mortality-to-incidence ratio was estimated by using data on incidence and mortality rates from the GLOBOCAN 2012 database; the ratio was > 70% in 26 countries (28%), which included 21 countries in Africa (66%) and five countries in Asia (26%). Eight countries had no clinical oncologist available to provide care for patients with cancer. In 22 countries (24%), a clinical oncologist would provide care for < 150 patients with a new diagnosis of cancer. In 39 countries (42%), a clinical oncologist would provide care for > 500 patients with cancer. In 27 countries (29%), a clinical oncologist would provide care for > 1,000 incident cancers, of which 25 were in Africa, two were in Asia, and none were in Europe or the Americas. The economic and social development status of a country correlates closely with the burden of cancer and the shortage of human resources. Addressing the shortage of clinical oncologists in regions with a critical need will help these countries meet the sustainable development goals for noncommunicable diseases by 2030.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, cancer is the second leading cause of death.1 Although we know that cancer mortality rates are dropping in United States, even within the country, glaring cancer health disparities exist.2 In countries with less advanced health care facilities, cancer incidence and mortality continues to rise.1 In most of these regions, the mortality-to-incidence ratio is distressingly high, resulting in a profound burden on public health and the economy. Cancer accounts for > 200 million disability-adjusted life years worldwide.3

A lack of access to resources to diagnose and treat cancer is a major hindrance to the equitable delivery of cancer care. In several regions of the world, access to cancer prevention and early diagnosis are suboptimal. The poor quality of cancer registries in low and middle-income countries results in a glaring knowledge deficit that adversely impacts cancer health care delivery. Access to affordable cancer treatment using chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or radiotherapy is another major impediment to global cancer control. In addition to these tremendous challenges, inadequate availability of health care professionals contributes to cancer health disparities. A shortage of > 2,300 medical oncologists in the United States is anticipated in 2025.4 It is an undeniable fact that there is a profound shortage of oncologists in several parts of the world; however, the magnitude of this problem is poorly described in the literature. The aim of this study was to survey and describe the availability of clinical oncologists around the world.

METHODS

Articles that provided data on the number of clinical oncologists that were published after January 1, 2007, and that provided data over any time period during the last 10 years were identified by using searches on PubMed and Google Scholar. In addition, searches were performed on professional society Web sites, documents, and government records that were obtained from the ministry of health Web sites of various countries. Data obtained from professional societies, government or health authority sources, research surveys, and expert opinions were considered to be valid for the purpose of this study. If there are multiple sources of data for a specific country, the most recent data were used if the source was deemed to be more reliable than the previous one. Because a nonsystematic search was conducted, a flow diagram will not be reported. Given the nature of the research question, such a search strategy is not expected to impact the validity of the study findings.

To obtain estimates on cancer incidence and mortality rates at the country level, the GLOBOCAN model—produced by International Agency for Research on Cancer—was used.5 It provides estimates on cancer incidence and mortality for 2012. The ratio of newly diagnosed patients with cancer per clinical oncologist was ascertained for each country. For the purpose of this study, the mortality-to-incidence ratio was computed from the incidence and mortality estimates for 2012 provided by the GLOBOCAN model. The economic status of countries was classified into low-, lower middle-, upper middle-, and high-income groups on the basis of gross national income by per capita calculated by using the World Bank Atlas method.6 The social development of a country was defined by the Sociodemographic Index (SDI), which was derived from measures of education, income, and fertility, and classified into low, low-middle, middle, high-middle, and high SDI categories.3

RESULTS

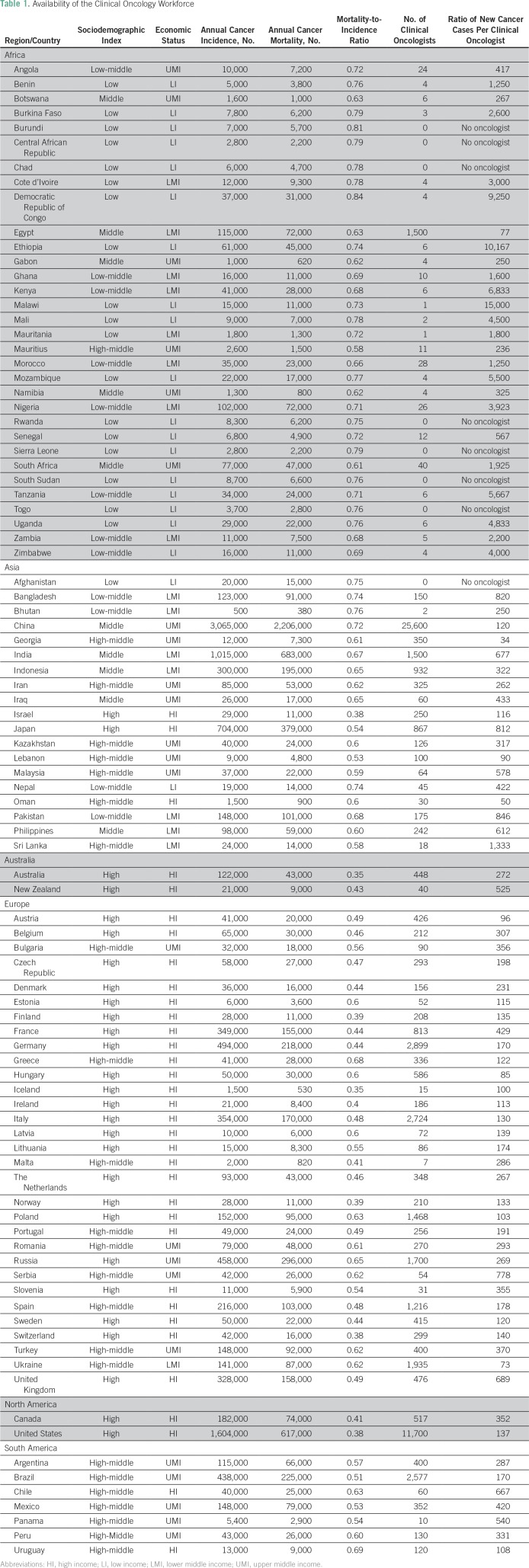

Data on the number of clinical oncologists were obtained for 93 countries from 30 unique references7-36 (Tables 1 and 2). It included 32 countries in Africa, 21 from Asia and Australia, 31 from Europe, and nine from North and South America.

Table 1.

Availability of the Clinical Oncology Workforce

Table 2.

Details of the Survey

Economic Status and SDI

The economic status of 20 countries was categorized as low income, and 19 were categorized as low SDI. Two countries were categorized as low economic income but had low-middle SDI (Zimbabwe and Nepal). Two countries that were categorized as low SDI were deemed lower middle–income countries using the World Bank definition (Cote d’Ivoire and Mauritania).

Mortality-to-Incidence Ratio

The mortality-to-incidence ratio was > 70% in 26 countries (28%) and < 50% in 23 (25%). In Africa, the mortality-to-incidence ratio was > 70% in 21 countries (66%) and < 50% in none. In Asia, the mortality-to-incidence ratio was > 70% in five countries (26%) and < 50% in three (16%). The mortality-to-incidence ratio was > 70% in none of the countries in Europe or the Americas. The mortality-to-incidence ratio was > 50% in 13 countries (42%) in Europe and seven countries (100%) in South America.

Ratio of New Diagnosed Patients With Cancer Per Clinical Oncologist

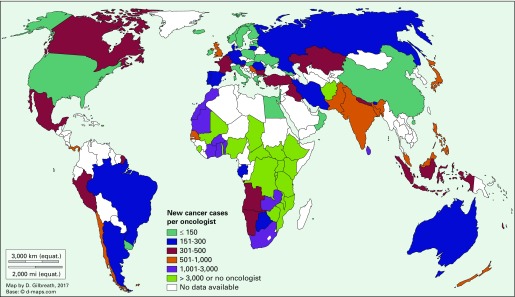

There were eight countries with no clinical oncologist available to provide care for patients with cancer (Fig 1). In 22 countries (24%), a clinical oncologist would provide care for < 150 patients with a new diagnosis of cancer. In 39 countries (42%), a clinical oncologist would provide care for > 500 patients with cancer, of which 26 countries were in Africa (81%), nine were in Asia (47%), two were in Europe (6%), and two were in South America (29%). An extreme shortage of clinical oncologists—> 1,000 incident cancers per clinical oncologist—existed in 25 countries in Africa (78%) and two countries (11%) in Asia. None of the countries in Europe or North or South America faced such an extreme shortage of clinical oncologists.

Fig 1.

Graphical summary of availability of oncologists.

DISCUSSION

This study identifies significant disparity in the availability of clinical oncologists among the 93 countries surveyed. To my knowledge, this is the most comprehensive survey of the clinical oncology workforce in the world. In addition to highlighting the critical burden of cancer in Africa, the study identifies an extreme shortage of clinical oncologists on the continent as well. The situation was only slightly better in Asia. Compared with the burden of cancer in Africa and Asia, the situation in Europe and the Americas seems to be better; however, there are major disparities among the countries on these continents too. The majority of countries in South America had a mortality-to-incidence ratio of > 50%. Similarly, 42% of countries in Europe had a mortality-to-incidence ratio of > 50%; however, compared with Africa and Asia, the availability of the clinical oncology workforce seems to be better in Europe and North and South America.

This global survey study has several limitations. Although the study is comprehensive and provides data for 93 countries, there are no data on the number of clinical oncologists for several countries; however, previous studies on the oncology workforce shortage have focused on specific countries or regions and do not provide a global overview of the issue as the current study does.9,23,25,30,31 Data are collated from different types of sources. Some are from professional societies or government sources; however, some are based on the opinion of experts. Most expert opinions are from individuals who collectively provide the estimates within the purview of a symposium or a survey, but some are individual perspectives that are based on personal experience working in a country. Oncology is not a recognized subspecialty in several countries, and, therefore, accurate estimates are hard to obtain; however, the data on the number of clinical oncologists are for individuals who exclusively care for patients with cancer. In some countries, such as India, it is possible that data on clinical oncologists include radiotherapists, who are more qualified in administering radiation than in prescribing chemotherapy. The training program for clinical oncologists and radiotherapists are different in both duration and scope; therefore, it is possible that the data for such countries are an overestimate. Data on the number of oncologists are collated over a 10-year period. With the exception of three countries, data on number of clinical oncologists are collated over a 5-year period (2011 to 2015). Regardless, it is unlikely that the pattern of the oncology workforce shortage will be any different if the time period was restricted to a single year. Finally, the estimates for annual cancer incidence and mortality that were obtained from GLOBOCAN 2012 could be imprecise as the data are obtained from cancer registries with variable quality. Nevertheless, the incidence and mortality data from GLOBOCAN 2012 is recognized universally as the best estimates on cancer burden currently available in a public domain.

There are several ways that we can improve the situation of the shortage of clinical oncologists. International organizations, such as the WHO and Union for International Cancer Control, and professional societies, such as ASCO and the European Society of Medical Oncology, can collaborate to conduct a global study on the availability of human resources for tackling cancer. Such a study should ideally involve a precise estimation of not just the clinical oncology workforce, but also of radiotherapists and surgical oncologists. An accurate estimation of human resources and the strengthening of cancer registries will be an important step toward reaching the sustainable development goal of reducing noncommunicable disease by one third by 2030. Training programs must be instituted in regions with an extreme shortage of clinical oncologists. Governments in countries with a shortage of clinical oncologists will need to urgently design measures to address challenges within their regions. Nontraditional approaches, such as training and equipping primary care providers and nurses, can be considered in these countries. Countries such as Egypt and India that have a well-established oncology workforce can be tapped to train the health care professionals in their region. Instead of utilizing scholarship programs to train doctors and nurses from low-income countries by sending them to high-income countries, the funds could be used to enhance regional collaborations. Similarly, oncology workforce development can be significantly aided by collaborations between institutions and universities in high- and low-income countries.

The economic status of a country and its social development status correlate closely with the mortality-to-incidence ratio and the availability of clinical oncologists. Of these three, improving the human resource capacity of a country would be a low-hanging fruit for the global oncology community. Increasing the availability of clinical oncologists may not improve the quality of cancer care. Nevertheless, easier access to a trained health care professional will positively influence the society. Patients will likely be diagnosed at an earlier stage. Various precancerous conditions can be diagnosed and managed effectively. Curable cancers will be treated with curative intent. Eventually, more patients with cancer will survive the disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I acknowledge the contribution of Donna Gilbreath of the Markey Cancer Center Research Communications Office, who assisted with preparing the figure in the manuscript, and Brigitte Engelmann, MD, and Lloyd Panjikaran, MD, who provided input during data collection.

AUTHOR’S DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Aju Mathew

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1459–1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:524–548. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang W, Williams JH, Hogan PF, et al. Projected supply of and demand for oncologists and radiation oncologists through 2025: An aging, better-insured population will result in shortage. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:39–45. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Agency for Research on Cancer GLOBOCAN: 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr

- 6.The World Bank World Bank income classification. http://www.databank.worldbank.org/data/download/site-content/CLASS.xls

- 7.Nelson AM, Milner DA, Rebbeck TR, et al. Oncologic care and pathology resources in Africa: Survey and recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:20–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.9767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stefan DC, Elzawawy AM, Khaled HM, et al. Developing cancer control plans in Africa: Examples from five countries. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e189–e195. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parikh PM, Raja T, Mula-Hussain L, et al. Afro Middle East Asian symposium on cancer cooperation. South Asian J Cancer. 2014;3:128–131. doi: 10.4103/2278-330X.130452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan C, Cira M, Karagu A, et al. The Kenya cancer research and control stakeholder program: Evaluating a bilateral partnership to strengthen national cancer efforts. J Cancer Pol. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpo.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boutayeb S, Taleb A, Belbaraka R, et al. The practice of medical oncology in Morocco: The National Study of the Moroccan Group of Trialist in Medical Oncology (EVA-Onco) ISRN Oncol. 2013;2013:341565. doi: 10.1155/2013/341565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Foundation for Cancer Care in Tanzania Meeting the challenge of cancer care in northern Tanzania: A program for comprehensive and sustainable care http://tanzaniacancercare.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/FCCT-White-Paper.pdf

- 13.Are C. Cancer on the global stage: Incidence and cancer-related mortality in Afghanistan. http://www.ascopost.com/issues/january-25-2016/cancer-on-the-global-stage-incidence-and-cancer-related-mortality-in-afghanistan/

- 14.Yang LL, Zhang XC, Yang XN, et al. Lung cancer treatment disparities in China: A question in need of an answer. Oncologist. 2014;19:1084–1090. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silbermann M, editor. Cancer Care in Countries and Societies in Transition: Individualized Care in Focus. New York, NY: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Awofeso N, Rammohan A, Asmaripa A. Exploring Indonesia’s “low hospital bed utilization-low bed occupancy-high disease burden” paradox. J Hosp Adm. 2013;1:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bayat M, Harirchi I, Zalani GS, et al. Estimation of oncologists’ active supply in Iran: Three sources capture-recapture method. Iranian Red Crescent Med J. 2017;19:e56126. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Efrati I. As number of cancer patients in Israel grows, oncology experts on decline. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/culture/health/1.660449

- 19.Takiguchi Y, Sekine I, Iwasawa S, et al. Current status of medical oncology in Japan: Reality gleaned from a questionnaire sent to designated cancer care hospitals. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44:632–640. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyu059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piana R. Initiatives bring gradual improvements to cancer care in Lebanon. http://www.ascopost.com/issues/september-1-2012/despite-challenges-initiatives-bring-gradual-improvements-to-cancer-care-in-lebanon/

- 21.Daily Express 64 oncologists and nearly half women. http://www.dailyexpress.com.my/read.cfm?NewsID=868

- 22.Noh D-Y, Roh JK, Kim YH, et al. Symposium: “Oncology Leadership in Asia”. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49:283–291. doi: 10.4143/crt.2017.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Medical practitioners workforce 2015. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/workforce/medical-practitioners-workforce-2015/contents/what-types-of-medical-practitioners-are-there

- 24.Bidwell S, Simpson A, Sullivan R, et al. A workforce survey of New Zealand medical oncologists. N Z Med J. 2013;126:45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Azambuja E, Ameye L, Paesmans M, et al. The landscape of medical oncology in Europe by 2020. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:525–528. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eurostat Cancer statistics. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Cancer_statistics

- 27.Russian Society of Clinical Oncology Home. http://www.rosoncoweb.ru/en/society/

- 28.Rivera F, Andres R, Felip E, et al. Medical oncology future plan of the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology: Challenges and future needs of the Spanish oncologists. Clin Transl Oncol. 2017;19:508–518. doi: 10.1007/s12094-016-1595-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chekhun VF, Shepelenko IV. Cancer education in Ukraine. Ecancermedicalscience. 2013;7:369. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2013.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canadian Medical Association Medical oncology profile. https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/Medical-Oncology-e.pdf

- 31.Vose J. The state of cancer care in America 2016. https://www.asco.org/research-progress/reports-studies/cancer-care-america-2016#/executive-summary-0

- 32.Costanzo MV, Nervo A, Lopez C, et al. Adjuvant breast cancer treatment in Argentina: Disparities between prescriptions and funding requirements—A survey. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl):17571. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strasser-Weippl K, Chavarri-Guerra Y, Villarreal-Garza C, et al. Progress and remaining challenges for cancer control in Latin America and the Caribbean. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1405–1438. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jimenez de la Jara J, Bastias G, Ferreccio C, et al. A snapshot of cancer in Chile: Analytical frameworks for developing a cancer policy. Biol Res. 2015;48:10. doi: 10.1186/0717-6287-48-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goss PE, Lee BL, Badovinac-Crnjevic T, et al. Planning cancer control in Latin America and the Caribbean. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:391–436. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Artac M. The state of cancer care in Turkey. https://gicasym.org/state-cancer-care-turkey