Abstract

Various subtypes of breast cancer defined by estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) exhibit etiological differences in reproductive factors, but associations with other risk factors are inconsistent. To clarify etiological heterogeneity, we pooled data from nine cohort studies. Multivariable, joint Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for molecular subtypes. Of 606,025 women, 11,741 invasive breast cancers with complete tissue markers developed during follow-up: 8,700 luminal A-like (ER+ or PR+/HER2-), 1,368 luminal B-like (ER+ or PR+/ HER2+), 521 HER2-enriched (ER-/PR-/HER2+), and 1,152 triple-negative (ER-/PR-/HER2-) disease. Ever parous compared to never was associated with lower risk of luminal A-like (HR=0.78, 95% CI 0.73 – 0.83) and luminal B-like (HR=0.74, 95% CI 0.64 – 0.87) as well as a higher risk of triple negative disease (HR=1.23, 95% CI 1.02 – 1.50; p-value for overall tumor heterogeneity <0.001). Direct associations with luminal-like, but not HER2-enriched or triple negative, tumors were found for age at first birth, years between menarche and first birth, and age at menopause (p-value for overall tumor heterogeneity <0.001). Age-specific associations with baseline body mass index differed for risk of luminal A-like and triple-negative breast cancer (p-value for tumor heterogeneity=0.02). These results provide the strongest evidence for etiological heterogeneity of breast cancer to date from prospective studies.

Keywords: etiological heterogeneity, breast cancer, risk factors, parity, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, HER-2/neu, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Despite advances in risk factor identification, screening, and treatment, breast cancer is still a leading cause of cancer incidence and death worldwide. Few breast cancer risk factors have been identified that are easily modifiable or strongly associated with incidence. Current risk prediction models incorporate multiple risk factors but have limited ability to predict fatal breast cancer (1). The heterogeneous nature of invasive breast cancer at the molecular level (2, 3) necessitates the need for subtype-specific models (1), including for triple negative breast cancer (defined by the lack of expression of estrogen receptor-alpha (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)/neu status) that have a poor 5-year prognosis (4). Creating subtype-specific risk prediction models first requires clarification of the subtype associations with known risk factors and identification of novel subtype-specific risk factors (1).

Accumulating epidemiologic data support a dual effect of reproductive factors, including parity, age at first birth, and breastfeeding, on risk of ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancer (5–10). Other hormonal factors might also have different associations by molecular subgroups of breast cancer. A recent systematic review of 11 established breast cancer risk factors and their association with breast cancer risk by molecular subtype defined by ER, PR, and HER2 concluded there were insufficient data to draw conclusions about etiological heterogeneity for other risk factors (11). Family history of breast cancer was the only risk factor consistently associated with increased risk of all breast cancer subtypes (11). Risk factors for luminal A-like breast cancer (ER+ or PR+/HER2-), representing about 70% of all breast cancers, closely mirrored those for breast cancer overall. Limited knowledge has been gained regarding risk factors for luminal B-like (ER+ or PR+/ HER2+), HER2-enriched (ER-/PR-/HER2+), or triple negative breast cancers, due to their small numbers in any individual study (11), and regarding the value of HER2 to identify etiological heterogeneity (12). More recently, a linkage analysis of the Danish Cancer Registry and a parity database found possible age interactions for reproductive risk factor-subtype associations (13).

To estimate risk factor associations with breast cancer molecular subtypes with more precision, we utilized a harmonized dataset of nine prospective cohort studies in the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cohort Consortium with over 11,000 cases with molecular subtype based on ER, PR, and HER2 status data from 606,025 study participants. We also examined age interactions with parity and BMI. In secondary analyses, we explored etiological heterogeneity of HER2 status, including assessing risk factor associations by ER/PR status only.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study Population.

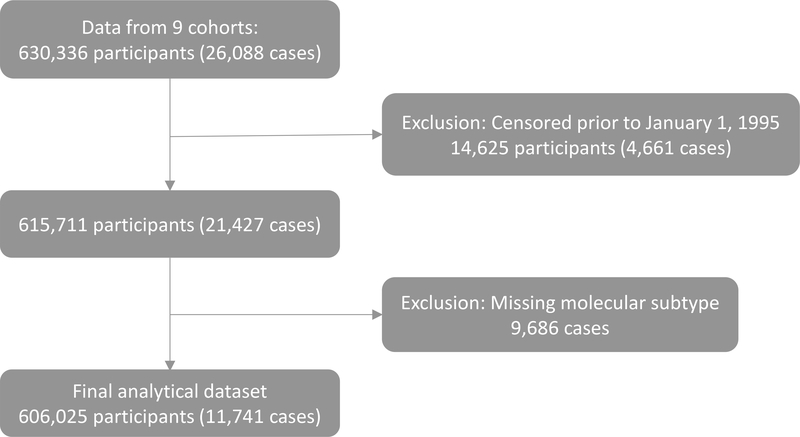

Nine member studies of the NCI Cohort Consortium that had breast cancer cases with ER and PR, or HER2 data agreed to participate: the Cancer Prevention Study-II (CPS-II) Nutrition Cohort, the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study (MCCS), the National Institutes of Health-AARP (NIH-AARP) Diet and Health Study cohort study, the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), the Nurses’ Health Study-II (NHS2), the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening cohort, the Swedish Mammographic Cohort (SMC), the Swedish Women’s Lifestyle and Health Study (SWLH), and the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study (WHI-OS; Table 1). Individual-level data for 630,336 women (Figure 1) were provided for each cohort after excluding males and those with a personal history of cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer) at baseline, or with other cohort-specific exclusions. Further exclusions are described in the Statistical Analysis section as part of the calculation of person-time.

Table 1.

Description of nine cohort studies that contributed to the pooled analysis of risk factors by risk invasive breast cancer subtypes in the National Cancer Institute Cohort Consortium

| Study Name (Acronym) | Year of Questionnaire |

Age at Questionnaire, Mean (SD) |

Follow-up Years, Mean (SD) |

Total N |

Case N |

Parous, % |

Age at First Birth, Mean (SD) |

Body Mass Index, Mean (SD) |

1° family history % |

HR+ Cases, % |

HER2+ Cases, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Prevention Study-II (CPSII) | 1992–1993 | 62.6 (6.5) | 11.9 (4.0) | 70,039 | 1,375 | 92.5 | 23.9 (4.0) | 25.6 (4.8) | 13.7 | 88.7 | 14.6 |

| Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study (MCCS) | 1990–1994 | 54.8 (8.6) | 15.2 (2.3) | 22,569 | 577 | 86.3 | 25.0 (4.5) | 26.7 (4.9) | N/A | 81.6 | 16.3 |

| NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study (NIH-AARP) | 2004–2006 | 69.9 (5.4) | 1.9 (0.4) | 97,635 | 253 | 84.2 | 23.2 (4.2) | 27.1 (5.9) | 14.5 | 85.4 | 15.0 |

| Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) | 1979 | 46.3 (7.2) | 11.8 (2.7) | 75,164 | 1,992 | 94.4 | 25.1 (3.3) | 24.4 (4.4) | 6.4 | 85.6 | 16.8 |

| Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS2) | 1989 | 34.6 (4.7) | 13.0 (2.5) | 110,043 | 1,368 | 69.8 | 25.5 (4.0) | 24.0 (4.7) | 2.0 | 83.9 | 17.5 |

| Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO) | 1993–2001 | 63.0 (5.4) | 8.6 (2.5) | 67,545 | 2,120 | 92.5 | 23.1 (4.3) | 27.2 (5.6) | 13.7 | 85.5 | 18.1 |

| Swedish Mammography Cohort (SMC) | 1997 | 61.8 (9.3) | 13.0 (2.7) | 35,581 | 552 | 90.5 | 24.0 (4.9) | 25.0 (3.9) | 8.8 | 88.8 | 12.0 |

| Swedish Women’s Lifestyle and Health Study (SWLH) | 1991–1992 | 39.6 (5.8) | 17.6 (0.9) | 47,706 | 768 | 88.3 | 25.4 (4.7) | 23.5 (3.7) | 16.6 | 86.5 | 15.4 |

| Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study (WHI-OS) | 1993–1997 | 63.7 (7.3) | 9.7 (3.2) | 79,743 | 2,736 | 86.9 | 24.4 (2.4) | 27.2 (5.8) | 17.8 | 85.6 | 15.1 |

| Overall | 54.3 (14.3) | 10.6 (5.1) | 606,025 | 11,741 | 85.9 | 24.3 (4.1) | 25.6 (5.2) | 10.8 | 85.8 | 16.1 |

Note: HR+, hormone receptor positive (estrogen receptor positive or progesterone receptor positive); N/A, not available

Figure 1.

Exclusion cascade resulting in an analytical dataset of 606,025 participants of which 11,741 were breast cancer cases in a pooled analysis of nine prospective cohort studies

Written informed consent was obtained from study participants at entry into each cohort or was implied by participants’ return of the enrollment questionnaire. The present investigation was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at each participating institution or was considered within the scope of the original IRB protocol.

Exposure Information.

De-identified data from the baseline questionnaire (i.e., exposures were not updated) were provided for known breast cancer risk factors using a common data dictionary. Data were harmonized, and variables were categorized a priori, including a category for missing or unknown values (see distribution of missing values in Supplemental Table 1 and categorizations in Supplemental Table 2). We calculated the years between menarche and first live birth using the ages of the respective life events. Age at menopause was reported based on age at natural or surgical menopause. Information on type of menopause, breastfeeding, or detailed postmenopausal hormone use was not requested from the individual cohorts.

Case Definition.

Cases were defined as incident, invasive breast cancers diagnosed after cohort enrollment and confirmed through cancer registry linkage or medical record/pathology report. For reported breast cancer deaths, breast cancer had to be listed as a primary or contributory cause of death (ICD-9: 174 or ICD-O, ICD-10: C50). ER, PR, and HER-2 status (positive or negative) was provided by the individual cohorts from the medical record/ pathology report or cancer registry data. For the main analyses, molecular subtype of the breast cancer was defined as luminal A-like (ER+ or PR+/HER2-), luminal B-like (ER+ or PR+/ HER2+), HER2-enriched (ER-/PR-/HER2+), or triple negative (ER-/PR-/HER2-). For the secondary analyses based only on ER and PR status, cases were defined as hormone receptor positive (ER+ or PR+) or hormone receptor negative (ER- and PR-).

Statistical Model.

The start of person-time was determined based on the date of the return of the baseline survey or January 1, 1995, whichever date was later. This entry date was selected because this was the year of diagnosis for the first case with HER-2 data in our dataset (14,625 women, 4,661 of whom were cases, were censored before entry; Figure 1). For the main analyses, we further excluded cases with incomplete data on ER and PR, or HER2 (n=9,686; Figure 1). For the secondary analyses by hormone receptor status, we further excluded cases with incomplete data on hormone receptor status (n=2,760) from the 615,711 eligible participants (Figure 1), resulting in 612,951 participants. The end of person-time was the date of the first-occurrence: invasive breast cancer diagnosis, diagnosis of carcinoma in situ of the breast, death, or end of follow-up of that cohort.

A joint Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) (14). The joint Cox proportional model is based on a competing risk model, and utilizes time-to-event data, different baseline hazard functions for each tumor subtype, and direct comparison of associations with tumor subtypes (14). Calendar time was used as the underlying time scale to accommodate studies that began after 1995, and to more efficiently control for secular trends (15). All Cox models were stratified on cohort study and single year of age at the start of follow-up, and adjusted for race.

Since ER, PR, and HER2 status were not available for all cases (n=9,686; Figure 1) in the main analyses, we compared the magnitude of risk factor associations using cases with and without tumor markers using the joint Cox proportional hazard model as a supplemental analysis. An interaction variable for cases with and without complete subtype information was modeled and compared to a model without the interaction variable using the difference in the −2 log likelihood.

Multivariable-adjusted models included the variables under study: menopausal status, age at menopause, age at menarche, parity, age at first birth, first-degree family history of breast cancer, personal history of benign breast disease, ever oral contraceptive use, ever menopausal hormone use, BMI, alcohol consumption, and smoking status. Variables were coded as in Table 2. Missing values were treated differently based on whether modeling the variable as the main exposure of interest (subjects dropped from analysis) or as a covariate (subjects retained as separate missing category). To minimize the number of covariates with subtype-interaction variables, we only include interaction terms for covariates in the multivariate models that showed evidence of tumor heterogeneity in initial joint Cox models (14), including the following variables: age at menopause, parity, age at first birth, benign breast disease, and alcohol intake. Effect modification by attained age (dichotomized using 55 years of age as the cut-point because 99% of women aged ≥55 were postmenopausal at baseline) was evaluated for BMI and parity. Associations with BMI by age were also examined among never users of menopausal hormones.

Table 2.

Multivariate1-adjusted associations of known and suspected breast cancer risk factors with invasive breast cancer risk by status of the estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER-2/neu in a pooled analysis of nine prospective cohort studies

| Risk Factor Categorization | Luminal A-like |

Luminal B-like |

HER2-Enriched |

Triple Negative |

p-value3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case N | HR (95% CI) | Case N | HR (95% CI) | p-value2 | Case N | HR (95% CI) | p-value2 | Case N | HR (95% CI) | p-value2 | ||

| Parity | ||||||||||||

| Nulliparous | 1,163 | 1.00 | 192 | 1.00 | 57 | 1.00 | 109 | 1.00 | ||||

| Parous | 7,523 | 0.78 (0.73, 0.83) | 1,174 | 0.74 (0.63, 0.87) | 0.61 | 427 | 1.00 (0.76, 1.32) | 0.07 | 954 | 1.23 (1.02, 1.50) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Number of live births among parous women | ||||||||||||

| 1 births | 891 | 1.00 | 135 | 1.00 | 50 | 1.00 | 120 | 1.00 | ||||

| 2 births | 2,646 | 1.04 (0.96, 1.12) | 398 | 0.99 (0.81, 1.21) | 155 | 1.05 (0.75, 1.46) | 350 | 0.97 (0.78, 1.20) | ||||

| 3 births | 2,117 | 1.01 (0.93, 1.09) | 351 | 1.05 (0.85, 1.29) | 124 | 1.03 (0.72, 1.46) | 290 | 0.96 (0.77, 1.20) | ||||

| 4+ births | 1,849 | 0.91 (0.83, 0.99) | 284 | 0.85 (0.68, 1.06) | 127 | 1.09 (0.76, 1.57) | 274 | 0.92 (0.73, 1.16) | ||||

| Continuous | 0.96 (0.94, 0.98) | 0.95 (0.89, 1.01) | 0.76 | 1.02 (0.92, 1.14) | 0.24 | 0.97 (0.91, 1.04) | 0.66 | 0.64 | ||||

| Age at first live birth among parous women | ||||||||||||

| <20 | 488 | 1.00 | 75 | 1.00 | 42 | 1.00 | 73 | 1.00 | ||||

| 20–24 | 3,882 | 1.09 (0.98, 1.20) | 624 | 1.16 (0.91, 1.49) | 253 | 0.90 (0.63, 1.26) | 578 | 1.08 (0.84, 1.40) | ||||

| 25–29 | 1,978 | 1.30 (1.17, 1.44) | 317 | 1.38 (1.06, 1.78) | 103 | 0.78 (0.54, 1.13) | 247 | 1.09 (0.83, 1.43) | ||||

| 30+ | 994 | 1.58 (1.41, 1.77) | 132 | 1.38 (1.03, 1.84) | 50 | 0.90 (0.59, 1.38) | 100 | 1.03 (0.76, 1.40) | ||||

| Continuous | 1.04 (1.03, 1.04) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.04) | 0.17 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | 0.001 | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Age at menarche | ||||||||||||

| <12 | 1,860 | 1.00 | 276 | 1.00 | 114 | 1.00 | 256 | 1.00 | ||||

| 12 | 2,655 | 0.99 (0.93, 1.05) | 441 | 1.08 (0.93, 1.26) | 147 | 0.89 (0.69, 1.14) | 355 | 0.97 (0.83, 1.15) | ||||

| 13 | 2,136 | 0.96 (0.90, 1.03) | 333 | 1.07 (0.91, 1.26) | 123 | 1.00 (0.77, 1.29) | 267 | 0.90 (0.76, 1.07) | ||||

| 14+ | 1,998 | 0.93 (0.87, 0.99) | 309 | 1.00 (0.85, 1.18) | 131 | 1.05 (0.81, 1.35) | 270 | 0.95 (0.80, 1.13) | ||||

| Continuous age | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 0.44 | 1.03 (0.95, 1.12) | 0.20 | 0.98 (0.92, 1.03) | 0.91 | 0.56 | ||||

| Years between menarche and first birth among parous women | ||||||||||||

| 0–7.9 | 1,185 | 1.00 | 197 | 1.00 | 103 | 1.00 | 203 | 1.00 | ||||

| 8–9.9 | 1,289 | 1.11 (1.02, 1.20) | 207 | 1.05 (0.86, 1.27) | 77 | 0.75 (0.55, 1.01) | 173 | 0.86 (0.70, 1.06) | ||||

| 10–11.9 | 1,545 | 1.15 (1.06, 1.24) | 239 | 1.09 (0.90, 1.32) | 105 | 0.92 (0.69, 1.22) | 206 | 0.87 (0.71, 1.07) | ||||

| 12–14.4 | 1,563 | 1.22 (1.13, 1.32) | 263 | 1.24 (1.03, 1.51) | 66 | 0.57 (0.42, 0.79) | 220 | 0.97 (0.80, 1.19) | ||||

| 14.5–79 | 1,721 | 1.53 (1.42, 1.65) | 236 | 1.25 (1.03, 1.52) | 95 | 0.91 (0.68, 1.21) | 194 | 0.97 (0.79, 1.19) | ||||

| Continuous | 1.03 (1.03, 1.04) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) | 0.11 | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | <0.001 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Age at menopause | ||||||||||||

| <50 | 2,338 | 1.00 | 379 | 1.00 | 120 | 1.00 | 267 | 1.00 | ||||

| 50–54 | 2,309 | 0.81 (0.76, 0.86) | 343 | 0.73 (0.62, 0.85) | 135 | 0.92 (0.71, 1.19) | 357 | 1.07 (0.90, 1.26) | ||||

| 55+ | 689 | 1.13 (1.04, 1.24) | 98 | 1.00 (0.80, 1.26) | 31 | 1.04 (0.69, 1.55) | 66 | 0.95 (0.72, 1.24) | ||||

| Continuous | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.05) | 0.43 | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.22 | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Ever use of menopausal hormones | ||||||||||||

| Never | 4,650 | 1.00 | 727 | 1.00 | 300 | 1.00 | 652 | 1.00 | ||||

| Ever | 3,854 | 1.21 (1.15, 1.28) | 624 | 1.32 (1.15, 1.51) | 0.24 | 210 | 1.04 (0.83, 1.31) | 0.20 | 483 | 1.09 (0.94, 1.27) | 0.20 | 0.17 |

| Ever use of oral contraceptives | ||||||||||||

| Never | 4,274 | 1.00 | 654 | 1.00 | 251 | 1.00 | 537 | 1.00 | ||||

| Ever | 4,402 | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) | 710 | 1.04 (0.93, 1.18) | 0.59 | 268 | 0.95 (0.78, 1.16) | 0.60 | 613 | 1.03 (0.90, 1.18) | 0.72 | 0.87 |

| First-degree family history of breast cancer | ||||||||||||

| No | 5,709 | 1.00 | 882 | 1.00 | 346 | 1.00 | 721 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 1,299 | 1.35 (1.26, 1.44) | 230 | 1.68 (1.44, 1.96) | 0.01 | 78 | 1.39 (1.07, 1.80) | 0.83 | 183 | 1.59 (1.34, 1.89) | 0.08 | 0.04 |

| Personal history of benign breast disease | ||||||||||||

| No | 3,873 | 1.00 | 578 | 1.00 | 230 | 1.00 | 486 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 1,757 | 1.28 (1.21, 1.36) | 333 | 1.55 (1.34, 1.78) | 0.01 | 110 | 1.36 (1.08, 1.72) | 0.60 | 231 | 1.33 (1.13, 1.56) | 0.66 | 0.10 |

| Alcohol intake at baseline | ||||||||||||

| Not current | 2,188 | 1.00 | 373 | 1.00 | 151 | 1.00 | 362 | 1.00 | ||||

| <1 drink/day | 4,635 | 1.12 (1.06, 1.18) | 713 | 1.03 (0.90, 1.17) | 275 | 0.94 (0.76, 1.15) | 584 | 0.87 (0.76, 1.00) | ||||

| 1–2 drinks/day | 843 | 1.34 (1.23, 1.46) | 137 | 1.31 (1.07, 1.59) | 37 | 0.87 (0.61, 1.24) | 88 | 0.86 (0.68, 1.09) | ||||

| 2+ drinks/day | 295 | 1.55 (1.37, 1.76) | 45 | 1.33 (0.98, 1.82) | 13 | 0.98 (0.55, 1.73) | 30 | 0.98 (0.67, 1.43) | ||||

| Continuous | 1.15 (1.11, 1.20) | 1.16 (1.04, 1.29) | 0.97 | 0.98 (0.79, 1.21) | 0.11 | 1.03 (0.90, 1.18) | 0.10 | 0.17 | ||||

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||||||||||

| Never | 4,477 | 1.00 | 731 | 1.00 | 271 | 1.00 | 589 | 1.00 | ||||

| Former | 3,115 | 1.07 (1.02, 1.13) | 469 | 1.00 (0.88, 1.12) | 187 | 1.14 (0.94, 1.37) | 403 | 1.14 (1.00, 1.30) | ||||

| Current | 1,108 | 1.04 (0.97, 1.12) | 168 | 0.95 (0.80, 1.14) | 0.43 | 63 | 0.97 (0.73, 1.29) | 0.68 | 160 | 1.19 (0.99, 1.42) | 0.38 | 0.55 |

Multivariable-adjusted models were stratified on age at enrollment (continuous) and cohort study and adjusted for race, education, age at menopause (categorical), age at menarche (continuous), parity, age at first birth, family history of breast cancer, benign breast disease, ever oral contraceptive use, ever menopausal hormone use, BMI (per 2 kg/m2), alcohol (categorical), and smoking status as well as subtype interactions with age at menopause, parity, age at first birth, benign breast disease, and alcohol intake.

p-value for heterogeneity of that subtype compared to luminal A

p-value for overall subtype heterogeneity

Between-study heterogeneity was evaluated using a likelihood ratio test comprising models with and without interaction terms for exposure and cohort.

Estimates based on fewer than 10 cases were not reported. Reported p-values were two-sided and considered statistically significant if <0.05. Interpretations of tumor heterogeneity results were based on p-values for the continuous variables, where applicable. Analyses were performed using R (version 3.3.1).

RESULTS

During follow-up (median of 10.4 years) of 606,025 study participants in this analysis, 11,741 invasive breast cancer cases were diagnosed and had complete information on tumor markers, including 8,700 luminal A-like (ER+ or PR+/HER2-), 1,368 luminal B-like (ER+ or PR+/ HER2+), 521 HER2-enriched (ER-/PR-/HER2+), and 1,152 triple-negative (ER-/PR-/HER2-) subtypes. For participants included in the analysis, the mean age at baseline was 54.7 years, the mean BMI was 25.6, 85.9% were parous and the mean age at first birth was 24.3 years (Table 1; Supplemental 1).

As shown in Supplemental Table 2, associations among women in the analytical cohort (first column of HRs) were similar to those among women excluded from analyses due to a lack of ER, PR, and HER2 data (second column of HRs).

Considering cases only with complete data for ER, PR, and HER2, associations of reproductive factors with risk differed by molecular subtypes of breast cancer (Table 2). Being parous was associated with 22–26% lower risk of luminal-like subtypes, but a 23% higher risk of triple negative breast cancer (p-value for heterogeneity compared with luminal A <0.001; Table 2). The difference between associations for risk HER2-enriched and triple negative breast cancer were not statistically significant (p-value for tumor heterogeneity=0.23; data not in tables). The association between being parous and risk of triple negative breast cancer differed by attained age, such that the association was stronger with parity for women aged 55 years or older (HR=1.56, 95% CI 1.21 – 2.01) than for younger women (HR=0.81, 95% CI 0.58 – 1.14; p-value for age interaction=0.002; Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate1-adjusted associations of parity and BMI with invasive breast cancer risk by status of the estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER-2/neu and attained age in a pooled analysis of nine prospective cohort studies

| Categories of Subtype and Attained Age |

Parity |

Body Mass Index (kg/m2) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nulliparous |

Parous |

18.5–22.4 |

22.5–24.9 |

25–24.9 |

30+ |

Per 5 |

||||||||

| Cases | HR (95% CI) |

Cases | HR (95% CI) |

Cases | HR (95% CI) |

Cases | HR (95% CI) |

Cases | HR (95% CI) |

Cases | HR (95% CI) |

HR (95% CI) |

||

| Luminal A-like | ||||||||||||||

| Age <55 | 291 | 1.00 | 745 | 0.87 (0.76, 1.00) | 498 | 1.02 (0.87, 1.19) | 246 | 1.00 | 192 | 1.02 (0.85, 1.24) | 82 | 0.89 (0.69, 1.15) | 0.95 (0.89, 1.02) | |

| Age 55+ | 872 | 1.00 | 6778 | 0.81 (0.75, 0.87) | 1,801 | 0.87 (0.82, 0.93) | 1864 | 1.00 | 2388 | 1.05 (0.99, 1.12) | 1,492 | 1.20 (1.12, 1.28) | 1.10 (1.08, 1.12) | |

| p-value for age interaction | 0.39 | 0.06 | 7.06E-05 | |||||||||||

| Luminal B-like | ||||||||||||||

| Age <55 | 64 | 1.00 | 131 | 0.68 (0.50, 0.92) | 103 | 1.35 (0.94, 1.96) | 39 | 1.00 | 37 | 1.20 (0.77, 1.89) | 13 | 0.83 (0.44, 1.55) | 0.91 (0.77, 1.08) | |

| Age 55+ | 128 | 1.00 | 1043 | 0.84 (0.70, 1.01) | 290 | 0.98 (0.83, 1.16) | 267 | 1.00 | 361 | 1.10 (0.94, 1.29) | 237 | 1.28 (1.07, 1.53) | 1.09 (1.03, 1.14) | |

| p-value for age interaction | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.06 | |||||||||||

| p-value for tumor heterogeneity2 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 0.47 | |||||||||||

| HER2-enriched | ||||||||||||||

| Age <55 | 16 | 1.00 | 64 | 1.41 (0.80, 2.46) | 43 | 1.02 (0.61, 1.70) | 22 | 1.00 | 11 | 0.64 (0.31, 1.31) | 4 | N/C | 0.79 (0.61, 1.01) | |

| Age 55+ | 46 | 1.00 | 394 | 0.90 (0.67, 1.23) | 116 | 0.98 (0.76, 1.28) | 109 | 1.00 | 135 | 0.97 (0.76, 1.25) | 78 | 0.95 (0.71, 1.28) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) | |

| p-value for age interaction | 0.17 | 0.91 | 0.07 | |||||||||||

| p-value for tumor heterogeneity2 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.07 | |||||||||||

| Triple negative | ||||||||||||||

| Age <55 | 51 | 1.00 | 117 | 0.81 (0.58, 1.14) | 73 | 0.81 (0.56, 1.17) | 47 | 1.00 | 25 | 0.66 (0.41, 1.08) | 22 | 1.14 (0.68, 1.89) | 1.09 (0.94, 1.26) | |

| Age 55+ | 64 | 1.00 | 919 | 1.56 (1.21, 2.01) | 223 | 0.90 (0.75, 1.08) | 230 | 1.00 | 340 | 1.16 (0.98, 1.38) | 175 | 1.02 (0.84, 1.24) | 1.04 (0.98, 1.10) | |

| p-value for age interaction | 0.002 | 0.63 | 0.58 | |||||||||||

| p-value for tumor heterogeneity2 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |||||||||||

| p-value for overall tumor heterogeneity3 | <0.001 | 0.63 | 0.04 | |||||||||||

Multivariable-adjusted models were stratified on age at enrollment (continuous) and cohort study and adjusted for race, education, age at menopause (categorical), age at menarche (continuous), parity (1=nulliparous, 0=parous), age at first birth (continuous variable centered on median value among parous with the nulliparous and missing coded as that median value), family history of breast cancer, benign breast disease, ever oral contraceptive use, ever menopausal hormone use, BMI (per 2 kg/m2), alcohol (categorical), age at smoking initiation (continuous) as well as subtype interactions with age at menopause, parity, age at first birth, benign breast disease, and alcohol intake.

p-value for heterogeneity of that subtype compared to luminal A

p-value for overall subtype heterogeneity

N/C=not calculated

For parous women, the association for each additional live birth did not differ by molecular subtype of the tumor (p-value for overall tumor heterogeneity=0.64). However, the association for age at first birth did (p-value for overall tumor heterogeneity <0.001). An older age at first live birth was associated with higher risk of luminal A-like. Similar associations were found for risk of luminal B-like subtypes (p-value for heterogeneity=0.06), but not with HER2-enriched (p-values for heterogeneity=0.001) or triple negative breast cancers (p-values for heterogeneity <0.001; Table 2). We found evidence of study-specific differences for subtype-specific associations with number of live births (p=0.007; Supplemental Table 3).

Age at menarche associations did not vary by molecular subtype (p-value for overall heterogeneity=0.56; Table 2). However, for parous women, greater number of years between menarche and first birth was associated with higher risk of luminal A-like (per year HR=1.03, 95% CI 1.03 – 1.04) and luminal B-like breast cancer (per year HR=1.02, 95% CI 1.01 – 1.03), but not with the other subtypes (p-value for heterogeneity <0.0001).

Age at menopause was differentially associated with breast cancer molecular subtypes (p-value for overall heterogeneity =0.007). A one-year increase in age at menopause was associated with a 3–4% increase in risk for luminal-like cancers, while associations were null for HER2-enriched or triple negative breast cancers.

While there was no evidence of between-subtype variation (p-value for overall heterogeneity=0.17; Table 2), the direct association with use of menopausal hormones was statistically-significant only for luminal-like tumors. No significant associations were observed between ever use of oral contraceptives and breast cancer risk, overall or by molecular subtype.

Family history of breast cancer and a personal history of benign breast disease were associated with increased risk of all molecular subtypes; however, the strength of the association between both risk factors and risk of luminal B-like breast cancer was slightly stronger than for risk of luminal A-like breast cancer (p-value for tumor heterogeneity=0.01). No statistically significant differences in the magnitude of the association for these risk factors were found comparing risk of HER2-enriched and triple negative breast cancer (p-value for tumor heterogeneity >0.4; Supplemental Table 4).

Alcohol consumption (per drink per day) was associated with 16% higher risk of luminal cancers but not with other subtypes, although the differences by subtype were not statistically significant (p-value for overall tumor heterogeneity=0.17). Associations with smoking status were null for all subtypes (overall p-value for heterogeneity=0.55).

BMI was associated with increased risk of luminal A-like and luminal B-like tumors in women aged 55 and older but not in younger women (Table 3). BMI was not associated with risk of triple negative (p-value for tumor heterogeneity compared to risk of luminal A-like tumors =0.02) in either age group. Associations of BMI with breast cancer subtypes in women who never took menopausal hormones (Supplemental Table 5) were similar to those in Table 3. By hormone receptor status (Table 4), associations with BMI among women <55 years of age were not statistically different (p-value for tumor heterogeneity=0.09). In the older women, the direct association with BMI was slightly stronger for hormone receptor positive breast cancer, but not statistically significant than that for ER-/PR- breast cancer.

Table 4.

Multivariate1-adjusted associations of known and suspected breast cancer risk factors with invasive breast cancer risk by joint estrogen and progesterone receptors in a pooled analysis of nine prospective cohort studies

| ER+ or PR+ | ER-/PR- | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | HR (95% CI) | Cases | HR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Parity | ||||||

| No | 2,065 | 1.00 | 298 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 13,905 | 0.78 (0.75, 0.82) | 2,378 | 1.04 (0.92, 1.17) | <0.001 | |

| Number of live births among parous women | ||||||

| 1 births | 1,631 | 1.00 | 287 | 1.00 | ||

| 2 births | 4,879 | 1.04 (0.98, 1.10) | 798 | 0.93 (0.81, 1.06) | ||

| 3 births | 4,009 | 1.04 (0.98, 1.10) | 681 | 0.95 (0.82, 1.10) | ||

| 4+ births | 3,334 | 0.92 (0.86, 0.98) | 603 | 0.90 (0.77, 1.05) | ||

| Continuous | 0.96 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.02) | 0.61 | |||

| Age at first birth among parous women | ||||||

| <20 | 942 | 1.00 | 187 | 1.00 | ||

| 20–24 | 6,979 | 1.11 (1.04, 1.19) | 1,253 | 1.01 (0.86, 1.18) | ||

| 25–29 | 3,892 | 1.32 (1.22, 1.42) | 631 | 1.03 (0.87, 1.22) | ||

| 30+ | 1,790 | 1.54 (1.42, 1.67) | 248 | 1.03 (0.85, 1.25) | ||

| Continuous | 1.03 (1.03, 1.04) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | <0.001 | |||

| Age at menarche | ||||||

| <12 | 3,378 | 1.00 | 595 | 1.00 | ||

| 12 | 4,571 | 0.98 (0.93, 1.02) | 739 | 0.93 (0.83, 1.04) | ||

| 13 | 4,140 | 0.98 (0.94, 1.03) | 679 | 0.94 (0.84, 1.06) | ||

| 14+ | 3,790 | 0.95 (0.90, 1.00) | 645 | 0.97 (0.86, 1.09) | ||

| Continuous | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.66 | |||

| Years between menarche and first birth among parous women | ||||||

| 0–7.9 | 2,304 | 1.00 | 476 | 1.00 | ||

| 8–9.9 | 2,418 | 1.09 (1.03, 1.15) | 430 | 0.92 (0.80, 1.05) | ||

| 10–11.9 | 2,890 | 1.17 (1.10, 1.23) | 474 | 0.89 (0.78, 1.02) | ||

| 12–14.4 | 2,717 | 1.21 (1.14, 1.28) | 429 | 0.89 (0.78, 1.02) | ||

| 14.5–79 | 3,185 | 1.46 (1.38, 1.54) | 498 | 1.03 (0.91, 1.18) | ||

| Continuous | 1.03 (1.03, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | <0.001 | |||

| Age at menopause | ||||||

| <50 | 4,477 | 1.00 | 635 | 1.00 | ||

| 50–54 | 4,256 | 0.80 (0.77, 0.84) | 754 | 0.96 (0.86, 1.08) | ||

| 55+ | 1,260 | 1.13 (1.06, 1.20) | 166 | 1.05 (0.89, 1.25) | ||

| Continuous | 1.03 (1.02, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | <0.001 | |||

| Ever use of menopausal hormones | ||||||

| Never | 8,494 | 1.00 | 1,548 | 1.00 | ||

| Ever | 7,086 | 1.25 (1.20, 1.30) | 1,056 | 1.06 (0.96, 1.17) | 0.003 | |

| Ever use of oral contraceptives | ||||||

| Never | 8,052 | 1.00 | 1,292 | 1.00 | ||

| Ever | 7,869 | 1.03 (0.99, 1.07) | 1,377 | 1.05 (0.97, 1.15) | 0.60 | |

| First-degree family history of breast cancer | ||||||

| No | 10,720 | 1.00 | 1,764 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 2,488 | 1.42 (1.36, 1.49) | 409 | 1.50 (1.34, 1.68) | 0.37 | |

| Personal history of benign breast disease | ||||||

| No | 7,637 | 1.00 | 1,220 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 3,374 | 1.31 (1.25, 1.36) | 583 | 1.39 (1.25, 1.53) | 0.29 | |

| Alcohol intake at baseline | ||||||

| Not current | 4,078 | 1.00 | 793 | 1.00 | ||

| <1 drink/day | 8,272 | 1.10 (1.06, 1.14) | 1,336 | 0.93 (0.85, 1.02) | ||

| 1–2 drinks/day | 1,432 | 1.31 (1.23, 1.40) | 193 | 0.92 (0.79, 1.08) | ||

| 2+ drinks/day | 545 | 1.45 (1.32, 1.59) | 71 | 0.95 (0.74, 1.21) | ||

| Continuous | 1.14 (1.10, 1.17) | 1.00 (0.91, 1.09) | 0.005 | |||

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||||

| Never | 8,227 | 1.00 | 1,406 | 1.00 | ||

| Former | 5,639 | 1.07 (1.03, 1.11) | 915 | 1.08 (0.99, 1.17) | ||

| Current | 2,123 | 1.04 (0.99, 1.09) | 357 | 1.01 (0.89, 1.14) | 0.88 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) among women <55 years of age at baseline | ||||||

| 18.5–22.4 | 1,073 | 1.01 (0.91, 1.12) | 208 | 0.87 (0.70, 1.09) | ||

| 22.5–24.9 | 571 | 1.00 | 131 | 1.00 | ||

| 25.0–29.9 | 431 | 0.98 (0.86, 1.11) | 88 | 0.85 (0.65, 1.11) | ||

| ≥30 | 182 | 0.89 (0.75, 1.05) | 47 | 0.95 (0.68, 1.32) | ||

| Per 5 kg/m2 | 0.96 (0.91, 1.00) | 1.05 (0.95, 1.16) | 0.09 | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) among women ≥55 years of age at baseline | ||||||

| 18.5–22.4 | 3,247 | 0.91 (0.87, 0.95) | 540 | 0.96 (0.85, 1.08) | ||

| 22.5–24.9 | 3,278 | 1.00 | 523 | 1.00 | ||

| 25.0–29.9 | 4,315 | 1.07 (1.02, 1.12) | 713 | 1.08 (0.97, 1.21) | ||

| ≥30 | 2,585 | 1.19 (1.13, 1.26) | 388 | 1.04 (0.91, 1.19) | ||

| Per 5 kg/m2 | 1.09 (1.07, 1.10) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.09) | 0.08 | |||

Multivariable-adjusted models were stratified on age at enrollment (continuous) and cohort study and adjusted for race, education, age at menopause (categorical), age at menarche (continuous), parity (1=nulliparous, 0=parous), age at first birth (continuous variable centered on median value among parous with the nulliparous and missing coded as that median value), family history of breast cancer, benign breast disease, ever oral contraceptive use, ever menopausal hormone use, BMI (per 2 kg/m2), alcohol (categorical), age at smoking initiation (continuous) as well as subtype interactions with age at menopause, parity, age at first birth, benign breast disease, and alcohol intake.

Secondary analyses by hormone receptor status (not accounting for HER2) included 15,989 hormone receptor positive cases and 2,678 hormone receptor negative cases (Table 4). Parity, age at first birth, years between menarche and first birth among parous women, age at menopause, and alcohol intake were differentially associated by hormone receptor status (Table 4) as well as molecular subtype based on ER, PR, and HER2 status (Table 2). Associations with ever use of menopausal hormones and alcohol varied by hormone receptor status (p-value for tumor heterogeneity=0.003 and <0.001, respectively; Table 4), but not molecular subtype (Table 2). For family history of breast cancer, associations differed by molecular subtype (Table 2) but not hormone receptor status (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

In our pooled analysis of nine cohort studies with prospective data on 606,025 study participants including 11,741 invasive breast cancer cases with ER, PR, and HER2 status, we found evidence of etiological heterogeneity across tumor molecular subtypes. In general, the patterns of etiological heterogeneity were similar whether stratified by hormone receptor (ER/PR) status or molecular subtype approximated by ER, PR, and HER2 status. Established breast cancer risk factors were associated with luminal A-like breast cancer risk in the direction established for overall breast cancer risk. Risk factors associations with luminal B-like tumors, with the exception of family history of breast cancer and personal history of benign breast disease, were in the same direction as, and of similar magnitude to, those for luminal A-like tumors. To the contrary, the pattern of association with parity-related factors, age at menopause, and BMI differed for risk of triple-negative cancers.

The well-documented protection of parity-related factors with respect to breast cancer risk overall was limited to luminal-like/ hormone receptor positive breast cancer, while ever parous was associated with an increased risk of triple negative breast cancer in our pooled analysis. The duality of the parity association has been consistently reported in the largest previous studies (6, 9, 13, 16, 17). However, a recent meta-analysis of 14 cohort or case-control studies reported no association between ever parous and risk of triple negative breast cancer (pooled odds ratio=1.01, 95% CI 0.87 – 1.17) (10). Between-study heterogeneity was observed in the meta-analysis (I2=30%). Some of the between-study heterogeneity might be due to effect modification by attained age and different distributions of age among study participants. However, the direction of potential age interaction has been inconsistent across our pooled analysis, the Danish study (13), and a pooled analysis of data from African-American study participants (9). In the largest study of reproductive factors by age to date, the Danish registry study with 9,123 ER-/HER2- cases found that parity was directly associated with risk of ER- breast cancer (HR=1.36, 95% CI 1.04 – 1.77), but not with risk of ER+ breast cancer (HR=1.03, 95% CI 0.84 – 1.26) among women <50 years of age (13). With 1,083 ER- cases, the African American Breast Cancer Epidemiology and Risk (AMBER) Consortium reported direct associations between parity and ER- disease of similar magnitude across four age strata (p-value for interaction=0.68). Both of these reported findings are inconsistent with the 56% higher risk of triple negative breast cancer (n=1,151) associated with parity among women ≥ 55 years of age in our study. Furthermore, other studies have found that breastfeeding might ameliorate the higher risk of triple negative breast cancer associated with parity (7, 10), and differences in breastfeeding rates among studies might also contribute to between-study heterogeneity. The biological underpinnings of associations between parity and breast cancer subtypes might provide important understandings of early breast carcinogenesis.

In our study, onset of menopause at older ages was associated with a higher risk of luminal-like breast cancers but not HER2-enriched or triple negative breast cancers. While prior results varied across studies (18), our results are consistent with the incidence patterns by ER expression (19, 20), in which the incidence of ER- tumors flattens out after menopause (21), whereas the incidence of ER+ tumors continues to increase after menopause (22). Type of menopause (surgical or natural) should be considered in future analyses.

Reports of associations between BMI and breast cancer subtypes for older/ postmenopausal women have been inconsistent (11, 23), perhaps due in part to recall bias, small sample size, as well as differences in age distributions, BMI cut-points and reference group selection, and screening patterns across studies. Our results support a direct association between BMI and risk of luminal tumors for women ≥55 years, and no association with risk of triple-negative breast cancer. We selected 55 years as the age cut-point to minimize women in the menopausal transition among the older women at the expense of a more heterogenous group of younger women (<55 years of age). Despite this limitation, we still observed inverse associations between BMI and risk of luminal and HER2-enriched tumors for women <55 years of age, and a direct association with risk of triple-negative breast cancer. Our results are consistent with reviews of associations by ER, PR, and HER2 (24) and by ER/PR status (25–27). However, the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) investigators found direct associations for ER- (as well as ER+) breast cancers with BMI (23). It is unclear how the large proportion of missing data (43%) influenced results from the BCSC. Disentangling the biological pathways perturbed with obesity (25) driving these associations will require pooled analyses of studies with prospectively-collected biospecimens and well-characterized tumor characteristics.

First-degree family history of breast cancer varied by molecular subtype with the strongest association found for risk of luminal B cancers, but no difference was found by ER/PR status alone in our study. Our results might have been biased by the large percentage of missing values for this exposure, or the large percentage range across studies for first-degree family history (2.0–17,8%). However, the magnitude of our results is consistent with a synopsis of prior studies reporting that risk estimates associated with a positive family history range between 1.5 and 2.0 for each of the molecular subtypes (11), and we found no evidence of between-study heterogeneity for the associations between family history and molecular subtypes. We were not able to examine the association of number, year of onset, and bilaterality of affected relatives, or by BRCA1/2 mutation status, which might refine a possible relationship between family history of breast cancer and molecular subtypes. In the future, pooled analyses should include detailed family history and risk of breast cancer subtypes, which might improve risk assessment models that incorporate tumor pathology.

Personal history of benign breast disease is an indicator of higher risk of subsequent breast cancer overall (28), and is an integral part of some risk assessment models {Gail, 1989 #4174;Tyrer, 2004 #4175;Tice, 2015 #4723}. In our study, benign breast disease was a risk factor for all breast cancer subtypes with stronger magnitude of association with risk of luminal B-like breast cancer. In smaller studies, benign breast disease was associated consistently with risk of luminal A tumors, but not for other subtypes (16, 31). A better understanding of the clinical characteristics of breast cancers after a benign biopsy could inform risk assessment models to identify women who might benefit from risk-reducing strategies.

Our results suggest that ER status explains much of the etiological heterogeneity of breast cancer, consistent with trends in national incidence rates (12, 19, 22, 32). The minor differences in associations of family history of breast cancer or benign breast disease between luminal A and luminal B are likely not clinically relevant enough to warrant distinction.

Furthermore, reliance primarily on immunohistochemical stains for ER, PR, and HER2 to classify breast cancer molecular subtypes likely led to misclassification of outcomes. Historical changes in immunohistochemical thresholds for positivity and interpretation criteria over the time of case diagnoses (2, 3) likely led to misclassification of up to 20% of cases (33, 34). Additionally, use of these surrogate markers to assign intrinsic subtypes also introduces misclassification, particularly for luminal B-like and HER2-enriched subtypes (35). The St. Gallen International Breast Cancer Conference expert panel (36) recommends using grade or ki67 status to improve classification using surrogate markers, but we implemented commonly-used definitions based solely on ER, PR, and HER-2/neu status to compare our results with those from other epidemiologic studies. Misclassification of subtype is likely to be unrelated to risk factors, and the bias would tend to minimize true differences in association, for at least dichotomous variables, by subtype, as shown in a recent analysis of etiological heterogeneity (17). Despite this potential bias, we did observe differences in associations of benign breast disease and family history of breast cancer between luminal A-like and B-like disease.

Our study benefitted from the existing pooled data with ten exposures by subtype. However, examination of more detailed risk factor information and other risk factors not available here (e.g., physical inactivity, breastfeeding) might reveal further evidence of etiological heterogeneity. Furthermore, we did not harmonize updated information on exposure; this limitation may have led to misclassification of exposure and attenuated associations. We did use statistical methods that allowed us to carefully control for risk factor*subtype interactions and assess between-subtype heterogeneity overall and relative to the most common subtype (14).

In summary, our results are based on the largest study of prospective data to date and contribute to the accumulating evidence that etiological heterogeneity exists in breast carcinogenesis. Pooled analyses of studies with more detailed exposure and tumor classification are likely to be increasingly informative about etiology and risk factor identification (37). More precise estimates of risk factor associations will be required to improve risk assessment models with clinicopathological data.

Supplementary Material

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE.

Findings comprise the largest study of prospective data to date and contribute to the accumulating evidence that etiological heterogeneity exists in breast carcinogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The statements contained herein are solely those of the authors and do not represent or imply concurrence or endorsement by National Cancer Institute or the American Cancer Society.

The authors thank the study participants from all the cohorts for their invaluable contributions to this research. The Cancer Prevention Study-II (CPS-II) investigators thank the Study Management Group for their invaluable contributions to this research, and acknowledge the contribution to this study from central cancer registries supported through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Program of Cancer Registries, and cancer registries supported by the National Cancer Institute Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results program. The Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study (MCCS) was made possible by the contribution of many people, including the original investigators and the diligent team who recruited the participants and who continue working on follow-up. We would also like to express our gratitude to the many thousands of Melbourne residents who continue to participate in the study. We would like to thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and Nurses’ Health Study 2 (NHS2) for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

We thank Drs. Christine Berg and Philip Prorok (Division of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute), the Screening Center investigators and staff of the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial, Tom Riley and staff (Information Management Services, Inc.), Barbara O’Brien and staff (Westat, Inc.), and Jackie King (Bioreliance, Rockville) for their contributions to making this study possible. The authors thank the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) investigators and staff for their dedication, and the study participants for making the program possible. A full listing of WHI investigators can be found at: https://www.whi.org/researchers/Documents%20%20Write%20a%20Paper/WHI%20Investigator%20Short%20List.pdf

Funding: The pooling project was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute’s Cohort Consortium and funded by the intramural research program at the American Cancer Society. The American Cancer Society funds the creation, maintenance, and updating of the Cancer Prevention Study-II (CPS-II) cohort. The Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study (MCCS) receives core funding from the Cancer Council Victoria and is additionally supported by grants from the Australian NHMRC (209057, 251533, 396414, and 504715). The NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study (AARP) was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS1) was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (UM1CA186107 and P01CA087969). The Nurses’ Health Study 2 (NHS2) was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (UM1CA176726 and R01 CA050385). The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial is supported by contracts from the National Cancer Institute. The Swedish Mammography Cohort (SMC) was supported by the Swedish Research Council, Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research and the Swedish Cancer Foundation. The Swedish Women’s Lifestyle and Health Study (SWLH) was supported by the Swedish Research Council (grant number 521–2011-2955) and a Distinguished Professor Award at Karolinska Institutet to Hans-Olov Adami, grant number: 2368/10–221. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201100046C, HHSN268201100001C, HHSN268201100002C, HHSN268201100003C, HHSN268201100004C, and HHSN271201100004C.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sherman ME, Ichikawa L, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Relationship of Predicted Risk of Developing Invasive Breast Cancer, as Assessed with Three Models, and Breast Cancer Mortality among Breast Cancer Patients. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0160966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406(6797):747–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(19):10869–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(20):1938–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma H, Bernstein L, Pike MC, Ursin G. Reproductive factors and breast cancer risk according to joint estrogen and progesterone receptor status: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(4):R43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang XR, Chang-Claude J, Goode EL, et al. Associations of breast cancer risk factors with tumor subtypes: a pooled analysis from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(3):250–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Islami F, Liu Y, Jemal A, et al. Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk by receptor status--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(12):2398–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colditz GA, Rosner BA, Chen WY, Holmes MD, Hankinson SE. Risk factors for breast cancer according to estrogen and progesterone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(3):218–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer JR, Viscidi E, Troester MA, et al. Parity, lactation, and breast cancer subtypes in African American women: results from the AMBER Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambertini M, Santoro L, Del Mastro L, et al. Reproductive behaviors and risk of developing breast cancer according to tumor subtype: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;49:65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnard ME, Boeke CE, Tamimi RM. Established breast cancer risk factors and risk of intrinsic tumor subtypes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1856(1):73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullooly M, Murphy J, Gierach GL, et al. Divergent oestrogen receptor-specific breast cancer trends in Ireland (2004–2013): Amassing data from independent Western populations provide etiologic clues. Eur J Cancer. 2017;86:326–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson WF, Pfeiffer RM, Wohlfahrt J, et al. Associations of parity-related reproductive histories with ER+/− and HER2+/− receptor-specific breast cancer aetiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue X, Kim MY, Gaudet MM, et al. A comparison of the polytomous logistic regression and joint cox proportional hazards models for evaluating multiple disease subtypes in prospective cohort studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(2):275–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffin BA, Anderson GL, Shih RA, Whitsel EA. Use of alternative time scales in Cox proportional hazard models: implications for time-varying environmental exposures. Stat Med. 2012;31(27):3320–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamimi RM, Colditz GA, Hazra A, et al. Traditional breast cancer risk factors in relation to molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131(1):159–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holm J, Eriksson L, Ploner A, et al. Assessment of Breast Cancer Risk Factors Reveals Subtype Heterogeneity. Cancer Res. 2017;77(13):3708–3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson KN, Schwab RB, Martinez ME. Reproductive risk factors and breast cancer subtypes: a review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson WF, Chatterjee N, Ershler WB, Brawley OW. Estrogen receptor breast cancer phenotypes in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;76(1):27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yasui Y, Potter JD. The shape of age-incidence curves of female breast cancer by hormone-receptor status. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10(5):431–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Menashe I, Mitani A, Pfeiffer RM. Age-related crossover in breast cancer incidence rates between black and white ethnic groups. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(24):1804–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Prat A, Perou CM, Sherman ME. How many etiological subtypes of breast cancer: two, three, four, or more? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerlikowske K, Gard CC, Tice JA, et al. Risk Factors That Increase Risk of Estrogen Receptor-Positive and -Negative Breast Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnard ME, Boeke CE, Tamimi RM. Established breast cancer risk factors and risk of intrinsic tumor subtypes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Picon-Ruiz M, Morata-Tarifa C, Valle-Goffin JJ, Friedman ER, Slingerland JM. Obesity and adverse breast cancer risk and outcome: Mechanistic insights and strategies for intervention. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(5):378–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munsell MF, Sprague BL, Berry DA, Chisholm G, Trentham-Dietz A. Body mass index and breast cancer risk according to postmenopausal estrogen-progestin use and hormone receptor status. Epidemiol Rev. 2014;36:114–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierobon M, Frankenfeld CL. Obesity as a risk factor for triple-negative breast cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137(1):307–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(3):229–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(24):1879–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyrer J, Duffy SW, Cuzick J. A breast cancer prediction model incorporating familial and personal risk factors. Stat Med. 2004;23(7):1111–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaudet MM, Press MF, Haile RW, et al. Risk factors by molecular subtypes of breast cancer across a population-based study of women 56 years or younger. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130(2):587–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson WF, Pfeiffer RM, Dores GM, Sherman ME. Comparison of age distribution patterns for different histopathologic types of breast carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(10):1899–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College Of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(16):2784–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3997–4013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allott EH, Cohen SM, Geradts J, et al. Performance of Three-Biomarker Immunohistochemistry for Intrinsic Breast Cancer Subtyping in the AMBER Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(3):470–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldhirsch A, Winer EP, Coates AS, et al. Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(9):2206–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nichols HB, Schoemaker MJ, Wright LB, et al. The Premenopausal Breast Cancer Collaboration: A Pooling Project of Studies Participating in the National Cancer Institute Cohort Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(9):1360–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.