Abstract

A retrospective study of kids’ meals purchased at Walt Disney World was conducted to determine acceptance rates for healthy sides and beverages. Purchase data from all 145 Walt Disney World restaurants were analyzed using a log-linear model and a Poisson regression. Across all restaurants, 47.9% and 66.3% of guests accepted healthy default sides and beverages, respectively. Acceptance rates of sides and beverages were higher at quick-service restaurants (49.4% and 67.8%, respectively) compared to table-service restaurants (40.3% and 45.6%, respectively). The healthy defaults reduced calories (21.4%), fat (43.9%), and sodium (43.4%) for kids’ meal sides and beverages. This study contributes by examining the use of kids’ meal healthy defaults in quick-service and table-service restaurant formats at the world’s largest theme park, a previously unstudied setting, and by providing the largest ever healthy default data set. The results suggest that healthy defaults can shift food and beverage selection patterns toward healthier options.

Childhood obesity has increased remarkably in the past 30 years, in parallel with dramatic changes in the American lifestyle and the food and physical activity environments in which our children live (Hill and Peters 1998; Wang and Beydoun 2007). Particular attention has been paid to the relatively poor nutritional quality, including higher calories, fat, sugar, and salt content of food provided with kids’ meals in restaurants (Poti and Popkin 2011; Batada et al. 2012; Hearst et al. 2013; Powell and Nguyen 2013; Kirkpatrick et al. 2014), and its association with obesity in youth. Much effort is being devoted to understanding how to halt the progression of obesity among our youth. Some of the most promising approaches are taking aim at providing better availability and access to healthy food in settings including restaurants and, more recently, changing the behavioral choice options available to children and their parents (Story et al. 2008; Gittlesohn and Lee 2013). There are widely differing opinions, however, about whether the food industry itself can facilitate healthy eating (Brownell 2012; Freedman 2013).

Behavioral economics research has revealed a number of human decision biases that would seem to work against a person’s long-term best interests (Thaler and Sunstein 2008; Thorgeirsson and Kawachi 2013). Among these biases is a tendency for people to accept the status quo, in this case the default offering, under conditions where additional cognitive investment would be required (increased transaction cost) to make a different choice (Samuelson and Zeckhauser 1988; Korobkin 1998). Altering the default option of a choice set can be highly effective at changing behavior outcomes without restricting freedom of choice (Thaler and Sunstein 2003, 2008). For example, participation in organ donation and flu vaccination is dramatically increased when the participation policy is changed from opt in to opt out (Gimbel et al. 2003; Johnson and Goldstein 2004; Halpern, Ubel, and Asch 2007; Chapman et al. 2010).

While behavioral economic approaches have been examined for school lunch programs, nutrition assistance programs, and hospital cafeterias (Just, Mancino, and Wansink 2007; Thorndike et al. 2012), few studies have examined healthy defaults as applied to food selection in different types of restaurants. In one study in a sandwich shop, selection of healthy sandwiches was increased by 44% when the healthy options were presented on page one of the menu and the unhealthy sandwiches were on another page. This made ordering unhealthy sandwiches less convenient, increasing the transaction cost (Wisdom et al. 2010). In another study of a quick-service restaurant, the default side items and dessert were changed from fried potatoes and either a fried dessert or a toy, to either rice or beans and an applesauce option (McCluskey, Mittelhammer, and Asiseh 2012). Purchase of fries and fried desserts was statistically reduced when the healthy options were provided and promoted, but the effect was much stronger for altering dessert selection than for changing side item selection (McCluskey et al. 2012). Finally, two studies examined changing default side items and beverages in children’s meals. One study showed that, postimplementation, orders of healthy meals, milk and juice, and strawberry and vegetable side dishes increased significantly (p < .0001), while orders of soft drinks and french fries decreased significantly (p < .0001; Anzman-Frasca et al. 2015). The other study showed that providing healthy default side items and beverages in children’s meal bundles resulted in an average of 18.8% fewer calories per meal and a greater percentage (4.9%) of meals including milk as the beverage as compared to before the introduction of healthy defaults (Wansink and Hanks 2014).

Beginning in October 2006, the Walt Disney Company changed the default side item and beverage offered with all complete kids’ lunch and dinner meals (including those offering healthy and classic entrées) served in its domestic US theme parks and resorts (Walt Disney Company 2013). Prior to this date, kids’ meals were served with french fries and a regular soft drink as the default side and beverage. Default choices were changed to servings of fruit (grapes, apple slices, or unsweetened applesauce) or vegetables (baby carrots) while beverage choices changed to low-fat milk, water, or 100% juice (apple, orange, or fruit punch). Customers could substitute french fries or a soft drink upon request. In other words, they could opt out of the healthy side and beverage defaults. Pricing for kids’ meals with healthy defaults was the same as for meals with french fries and soft drink. Point-of-sale picture boards displaying the meals showed only the meal with the healthy default items, though all potential substitutes were listed on the menu board.

In addition to the kids’ meal healthy defaults for sides and beverages, Disney began offering a broader array of entrées that would be considered healthier than typical kids’ meal fare because they were reduced in calories, fat, and sodium. These entrées were offered as opt-in selections at restaurants.

In the present postintervention analysis, meal item sales data were analyzed from Walt Disney World (WDW) theme park and resort in the United States, located in Orlando, Florida. Data were analyzed for three fiscal years for which Disney had relatively complete point-of-sale data at WDW. Travel industry sources estimate annual domestic US attendance at WDW at over 17 million people (TEA/AECOM 2012), thus providing a large data set for analysis. Disney did not have complete data for Disneyland, located in Anaheim, California; therefore, Disneyland is not part of this analysis.

The primary focus of this investigation was to study consumer opt-out behavior by comparing the percent of kids’ meal items purchased with healthy side items or beverages compared with the percent of kids’ meal items purchased with a classic side and drink. In addition, we assessed the purchase frequency of healthier kids’ meal entrées that were not part of the healthy default program and required the consumer to specifically request the healthy item. This study contributes to present knowledge by examining the use of kids’ meal healthy defaults in the context of both quick-service and table-service restaurant formats at the world’s largest theme park (Walt Disney World), a previously unstudied setting for the use of healthy defaults with kids’ meal bundles. In addition, the large size of the data set and large number of restaurants included provide the single largest data set on healthy defaults ever reported.

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

Sales data for kids’ menu items were provided by the Walt Disney Company for the 145 restaurants located at WDW. The total comprised 94 quick-service restaurants (QSRs) and 51 table-service restaurants (TSRs). The data set included sales data during the period from October 2009 through October of 2012, representing fiscal years 2010, 2011, and 2012. The Walt Disney Parks and Resorts kids’ menus are intended for children ages 3–9. Although raw sales data were provided for this analysis, access to these data was provided with the understanding that only the percentages of different kids’ meal items sold, as a function of the total meal items sold, would be published. Likewise, WDW did not provide data for the number of children who visited the park for fiscal years 2010–12 or the absolute number of kids’ meal items sold during that period. Reporting percentages is not uncommon in the literature because of the proprietary nature of absolute numerical data for commercial businesses (Wansink and van Ittersum 2012; Laroche et al. 2014). In such cases where a company will not provide absolute numerical sales, the general convention has been to report differences in terms of percentages instead of as absolute numbers (Wansink 2012). Such an approach is common in health economics (Just and Wansink 2011, 2014) and psychology (Wansink and van Ittersum 2012, 2013).

We organized, aggregated, and analyzed the sales data according to restaurant type. Menu item unit purchase data were analyzed by month and year and composite for the 3-year observation period. Because of the manner in which the point-of-sale system at WDW captures data for QSRs (as individual items vs. bundled meals), it was not possible to assign specific kids’ side item or kids’ beverage purchases to specific kids’ meal entrée selections. Thus, the data are represented as percentages of total items purchased for each category of food (side, beverage, or entrée). At TSRs, Disney had incomplete data on beverage purchases because they are not always entered as individual sales (as are entrées) in this restaurant format. For example, TSRs offer water with all meals in addition to any other beverage, and these servings of water are not recorded with the beverage numbers. Because of this, the percentage of consumers who opted in to the healthy beverage option at TSR locations does not include consumers who consumed water as their beverage.

To determine the consumer acceptance rates for healthy default sides and beverages (under the opt-out scenario) and the selection rates for healthy entrées (under the opt-in scenario), the labels “classic” or “healthy” were assigned in the data set to each type of meal item, entrée, side, and beverage. For example, items such as french fries, regular soft drink, and hamburgers would be designated as “classic” kids’ meal items, whereas carrots, low-fat milk, and grilled chicken pasta were designated as “healthy” kids’ meal items. All meal items designated as healthy had significantly improved nutritional profiles for calories, fat, sodium, and sugar compared to the classic meal items offered as opt-in selections. Healthy default consumer acceptance rates were calculated based on the total number of kids’ meals sold minus the number of classic kids’ sides and beverages sold and expressed as a percentage of the total meals sold. The opt-in rate for selection of healthy entrées was calculated based on the total number of healthy kids’ entrées sold expressed as a percentage of the total number of kids’ entrées sold.

DATA ANALYSIS

Numbers of orders were first summarized from the database per measuring time (fiscal year) and TSR or QSR. The proportion of healthy orders for side, beverage, and entrée were then analyzed using log-linear modeling. Specifically, the number of healthy orders was modeled using a Poisson regression (Coxe, West, and Aiken 2009). Predictors included measuring time and TSR or QSR settings, along with their interaction. In addition, the log-transformed total number of orders (healthy plus classic orders) was used as an offset in order to model the proportion of healthy orders. Least-square means were used to estimate the proportion of healthy orders. Contrasts were used to test the between-restaurant format difference at each fiscal year, within restaurant format change from fiscal year to fiscal year, as well as the between-restaurant format difference with respect to the change from year to year. Statistical significance for comparisons between meal component selection by restaurant format and over time was set at p < .05. SAS procedure Proc GEMOD was used for analysis (SAS Institute, Inc., 100 SAS Campus Drive, Cary, NC 27513).

RESULTS

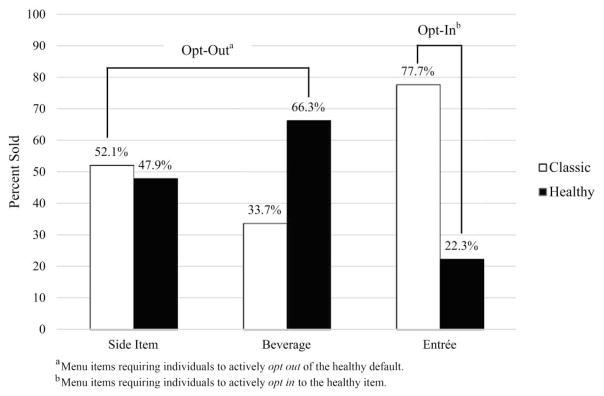

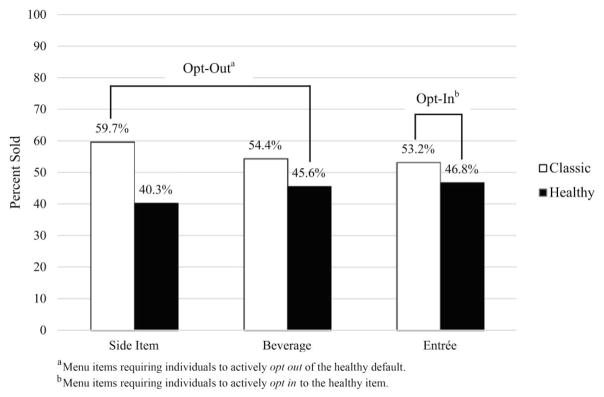

Percentages of kids’ menu items sold at the different locations are displayed for all restaurants (fig. 1), for QSRs (fig. 2), and for TSRs (fig. 3). The majority of all kids’ menu items were purchased from QSR locations at WDW, the remainder coming from TSR establishments. This distribution was relatively stable across the 3-year period studied (see table 1). The proportion of kids’ meals sold from fiscal year 2010 to fiscal year 2012 increased by 2.1% in TSR establishments and 22.8% in QSR establishments.

Figure 1.

Percent of healthy and classic kids’ menu items sold at all Walt Disney World restaurants.

Figure 2.

Percent of healthy and classic kids’ menu items sold at all Walt Disney World quick-service restaurants.

Figure 3.

Percent of healthy and classic kids’ menu items sold at all Walt Disney World table-service restaurants.

Table 1.

Percent of Healthy Default Items Accepted and Percent of Healthy Entrées Selected in Aggregate and by Restaurant Type

| FY2010 | FY2011 | FY2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 145 restaurants): | |||

| Side | 48.1a | 46.9a | 48.8a |

| Beverage | 65.8a | 65.4a | 67.6a |

| Entrée | 20.5a | 22.1a | 24.1a |

| QSR (n = 94 restaurants): | |||

| Side | 49.6a | 48.2a | 50.5a |

| Beverage | 67.7a | 67.2a | 69.0a |

| Entrée | 11.8a | 15.4a | 18.3a |

| TSR (n = 51 restaurants): | |||

| Side | 40.0a, b | 40.2a, b | 40.7a |

| Beverage | 47.8a | 42.6a | 46.8a |

| Entrée | 48.3a | 47.0a | 43.7a |

Note.—FY = fiscal year; QSR = quick-service restaurant; TSR = table-service restaurant.

p < .0001 for change in acceptance rates over the 3-year period (FY2010 to FY2011, FY2010 to FY2012, and FY2011 to FY2012) for healthy default sides and beverages and selection of healthy entrées.

p = .0413 for change in acceptance rates for healthy default sides at TSRs between FY2010 and FY2011.

The primary outcome examined was the percentage of total side and beverage items purchased that were healthy defaults (table 1). The percentages of healthy defaults accepted are shown in aggregate and for both restaurant types for each fiscal year. Also shown is the selection rate of healthier entrées as a percentage of total entrées purchased. Healthy entrées were not default options; rather, consumers had to opt in to select the healthy entrées.

Average yearly healthy default acceptance rates were statistically significantly different from one another, likely due to the large sample size (p < .0001 for all except default side acceptance rates at TSRs between FY2010 and FY2011, where p = .0413). There were no significant temporal trends in acceptance rates for the different meal items across the years.

The nutritional impact on the food purchase of the healthy default side and beverage as compared to the original defaults was substantial. The nutritional savings are based on the types of foods offered and purchased, not on actual food consumption, which was not measured. For example, in QSR restaurants, which represent the largest fraction of total item sales, replacing the classic french fry default side with any of the fruit or vegetable options greatly reduced the meal’s total calories, fat, saturated fat, and sodium. This information is shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Nutritional Proile of Classic and Healthy Default Menu Side Items at Quick-Service Restaurants

| Serving size (oz) | kcal | Fat (g) | Saturated fat (g) | Sugar (g) | Sodium (mg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QSR classic defaults: | ||||||

| French fries | 2.0 | 114 | 6.0 | 2.0 | .0 | 330 |

| Regular soft drink | 12.0 | 152 | .0 | .0 | 39.0 | 48 |

| QSR healthy defaults: | ||||||

| Grapes | 2.0 | 38 | .0 | .0 | 10.0 | 2 |

| Baby carrots | 1.6 | 20 | .0 | .0 | 2.0 | 44 |

| Apple slices | 2.2 | 30 | .0 | .0 | 6.0 | 0 |

| Unsweetened applesauce | 8.0 | 94 | .2 | .02 | 21.0 | 4 |

| 1% milk | 8.0 | 98 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 11.0 | 118 |

| 100% orange juice | 8.0 | 102 | .5 | .06 | 19.1 | 2 |

| 100% apple juice | 8.0 | 105 | .3 | .05 | 21.9 | 10 |

| 100% fruit punch juice | 8.0 | 96 | .4 | .05 | 21.0 | 11 |

Calorie savings ranged from 20 to 94 kilocalories (kcals) per serving. Replacing a soft drink with water or juice (and reducing serving size) had a significant impact on reducing sugar (18–28 grams) and calorie (50 kcals) intake. Replacing french fries with any of the vegetable or fruit selections saved 286 to 328 milligrams (mgs) of sodium per serving.

We estimated the potential magnitude of calorie, fat, saturated fat, sugar, and sodium reductions this program delivered over the 3 years studied as compared to leaving the original french fries and soft drink defaults in place. Prior to implementation of the healthy defaults, french fries and a soft drink were the only available options. Therefore, these estimates compare the nutritional values based on 100% of individuals selecting french fries and soft drink defaults versus the percent of individuals in this sample who actually selected the healthy defaults once they were implemented. Based on selection of the different healthy sides and beverages provided under the default program (i.e., number of servings of carrots, applesauce, grapes, low-fat milk, water, and juice, which replaced the original defaults of a regular soft drink and french fries), along with the nutritional values shown in table 2, the estimated total savings for total calories, fat (grams), saturated fat (grams), sugar (grams), and sodium (mgs) are shown in table 3. These savings reflect changes in the nutrient content of the foods purchased and do not reflect actual food consumption, which was not collected in this theme-park setting. Other studies have shown a high correspondence between food purchased and actual food consumption, especially in the case of lunch and snacks (Wansink and Johnson 2014).

Table 3.

Estimated Nutritional Savings Resulting from Selection of Healthy Defaults

| Nutrient | Amount consumed with selection classic default | Amount consumed with selection of healthy default | Amount saved with selection of healthy default | % change from selecting healthy default |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy intake (kcals) | 3,148,748,628 | 2,476,865,605 | 671,883,023 | −21.3% |

| Fat (grams) | 86,988,060 | 48,762,314 | 38,225,746 | −43.9% |

| Saturated fat (grams) | 28,996,020 | 16,595,602 | 12,400,418 | −42.8% |

| Sugar (grams) | 383,853,816 | 370,322,453 | 13,513,363 | −4.0% |

| Sodium (mgs) | 5,256,756,612 | 2,975,506,506 | 2,281,250,106 | −43.4% |

Note.—Nutritional savings are for the entire 3-year period (FY2010 to FY2012).

DISCUSSION

These results show that healthy defaults can be used in restaurant settings to improve diet quality. This is consistent with literature from other fields showing that default choice architecture can have a powerful and positive impact on consumer behavior (Loewenstein, Brennan, and Volpp 2007; Downs, Loewenstein, and Wisdom 2009; Wansink and Hanks 2014). Under a variety of conditions, consumers will accept the default choice versus opting out, which requires cognitive energy and decision making (Johnson and Goldstein 2003; Loewenstein et al. 2007; Downs et al. 2009; Wansink and Hanks 2014). The present report provides evidence that providing healthy choices as defaults on kids’ menus can positively influence food-choice behavior, at least within the setting of restaurants in a theme park. Nearly half (48%) of the side items and two-thirds (66%) of beverages purchased with kids’ meals at WDW over the 3 years examined were healthy. These findings are encouraging and are in line with other evidence (Anzman-Frasca et al. 2014) indicating that most children report nonnegative attitudes about fruit and vegetable side dishes when served with kids’ meals in restaurant settings. Currently, few restaurant chains serve healthy sides with kids’ meals as a default offering (Anzman-Frasca et al. 2014). Results of the current study provide support for testing healthy defaults in other food-service and community settings beyond theme parks both in the United States and in other countries.

Acceptance rates for the default choices for sides and beverages were different between the two restaurant types, with healthy beverage acceptance being 67.8% in the QSR setting compared to 45.6% in the TSR setting. Likewise, healthy side acceptance was 49.4% in QSR compared to 40.3% in TSR locations. The reason for the greater acceptance of healthy sides and beverages in the QSR setting cannot be determined from the data available. It is possible that in the QSR setting the entrée item (e.g., burger, pizza) dominates the purchase decision while the side and beverage items are not the focus of consumer attention. Another possibility is that QSRs in theme parks are likely more crowded and decisions are more rushed than in a normal QSR or a TSR, which could result in parents or children choosing the healthy default without actively realizing they were ordering a healthy option. In addition, one parent may stand in line while the other parent and the child(ren) wait to the side, which could result in miscommunication between the parent and child regarding the choice of the healthy default versus selecting a classic side and beverage (french fries and a soft drink).

The implementation of healthy defaults was limited to sides and beverages served with kids’ meals. In contrast, healthy entrées were offered as opt-in selections for kids’ meals at both QSR and TSR establishments. The healthy entrée opt-in selection rate in aggregate was only 22.3%, much lower than healthy default item acceptance rates for sides or beverages. At least part of the explanation for this low rate could be due to the specific set of choices presented to the consumer, namely, they had to ask for the healthy entrée as opposed to automatically receiving the healthy entrée unless they chose to opt out. The bias toward accepting the default option has been seen in a variety of settings for different consumer choices (Halpern et al. 2007; Downs et al. 2009; Chapman et al. 2010; Wansink and Hanks 2014; Anzman-Frasca et al. 2015). Although the aggregate healthy entrée selection rate was low, it was quite different between QSR and TSR establishments. Healthy entrée opt-in rates were only 14.7% in QSRs, whereas healthy entrée opt-in rates were 46.8% in TSRs. Again, the available data preclude determining an explanation for these findings. It is reasonable to hypothesize that consumers are looking for a different experience at these different restaurant types. Most QSRs across the food-service industry tend to design menus around a relatively limited selection of appealing entrées (e.g., burgers, pizza) while TSRs may have a menu with more diverse entrée selections (Celentano 2015). The greater diversity of choices in TSRs may facilitate the purchase of more entrées that are nutritionally healthier and still appealing to kids.

Disney intentionally engaged in several actions when they launched the healthy default kids’ menu program in 2006 that may have contributed to its early success (personal communication, Disney Food and Beverage Manager, 2013). Menu changes were introduced without any substantial public relations campaign, avoiding a potentially negative consumer response if consumers perceived that healthy items may not taste as good or be as fun (Berning, Couinard, and McCluskey 2011) or if consumers perceived that the use of healthy defaults threatened their freedom, resulting in consumers intentionally opting out of the healthy defaults in order to counteract this perceived threat (Pham, Mandel, and Morales 2016). This allowed consumers to become accustomed to the new offerings before the changes were deliberately brought to the public’s attention. It is possible that the addition of healthy menu items resulted in more health-conscious consumers attending WDW parks, thus increasing the success of the healthy defaults; however, as the changes were not widely publicized, it is unlikely that word-of-mouth regarding the healthy menu items significantly affected the acceptance of healthy defaults. In addition to limiting publicity of the menu changes, the decision to make small, discrete changes over time in the nutritional profile of the kids’ menu items may have reduced the likelihood of disrupting consumer preference and is in keeping with a small-changes approach to improving health behaviors (Hill, Peters, and Wyatt 2009). For example, making small sequential changes over time in formulations for improving nutritional profile has been applied to reducing the salt content of processed foods (Dotsch et al. 2009). Finally, in keeping with the concept of asymmetric paternalism (Thaler and Sunstein 2003, 2008; Loewenstein et al. 2007), consumers were given the option to ask for the nondefault (less healthy) side or beverage, which maintained freedom of choice.

Based on the successful implementation of healthy defaults in the real-world context of a large theme park, it seems reasonable to investigate this same strategy in other, more prevalent contexts such as QSRs and TSRs in local communities around the United States as well as in other countries. However, there are a number of elements of the Disney context that might distinguish it from individual restaurants in communities. Guests visiting Disney parks and resorts are generally on holiday and often stay on property a week or more, making them a captive audience. Because all Disney restaurants adopted the healthy default menus for kids, it created a kind of local healthy environment. Further research is needed to document whether results similar to the Disney example would be seen in a broader sample of food-service settings. In addition, it is important to note that, prior to offering healthy defaults, Disney did not include these healthy items on the menu; therefore, the separate effects of offering healthy items as defaults from the effects of adding healthy items to the menu as opt-in choices cannot be determined. While the Disney context may be distinct from a typical restaurant setting, there have been two studies examining the use of healthy defaults in large restaurant chains (Wansink and Hanks 2014; Anzman-Frasca et al. 2015). Results from these studies showed significant increases in orders of healthy meals, sides, and beverages (p < .0001; Anzman-Frasca et al. 2015) and an 18.8% decrease in the average number of calories per kids’ meal purchased (Wansink and Hanks 2014), suggesting that healthy defaults can be effective in a “real-world” context distinct from that of Walt Disney World. Recent announcements from large national fast-food chains indicate that the healthy default approach for improving the nutritional value of items served with kids’ meals is gaining ground (Bowerman 2015).

Debate about the role of the food industry in reducing obesity and improving consumer nutrition is well documented. Some have suggested that the food industry is not trustworthy, has little desire to make positive contributions to improve nutrition and reduce obesity, and must be regulated (Brownell 2012). Others argue that engaging the food industry in public-private partnerships can accelerate the reduction of obesity (Freedman 2013). The current study provides evidence relevant to this discussion and describes an example where a large publicly held company voluntarily made changes that were significant on a large scale, sustainable, and financially viable. This is an encouraging move in the marketplace, as it provides other restaurants a potential model for how to make nutritional improvements to their kids’ menus in ways that preserve consumer acceptance without negatively affecting the bottom line.

There are a number of limitations to the present study, including its nonexperimental design, which limits the ability to identify and understand the relative importance of factors contributing to the observed outcomes. Based on the way purchase data were captured at WDW, it was not possible to identify which specific sides and beverages were paired with which entrées. Such data would have allowed a more in-depth examination of consumer behaviors. Additional research examining the overall meal, as opposed to individual meal components, is warranted. In addition, we were unable to distinguish the difference between the effects of offering healthy items as defaults versus offering healthy items as opt-in choices. Finally, WDW represents a unique context distinct from everyday life, which potentially limits the application of these findings to other settings. However, as previously mentioned, findings from Wansink and Hanks (2014) and recent announcements by large chain restaurants (Bowerman 2015) support the notion that healthy defaults can be successfully applied in “real-world” settings.

Findings from this study show that the use of healthy defaults significantly improved the nutritional value of kids’ meals purchased at WDW and suggest the need to test the healthy default paradigm in other non-theme-park settings. Utilizing healthy defaults in restaurants is a promising means to improve consumer food selection without limiting freedom of choice while maintaining consumer satisfaction.

THE LARGER THEME: THE OPPORTUNITIES AND BOUNDARIES OF CHANGING DEFAULTS

The notion of changing menu defaults as a strategy for improving the nutritional intake of children (and adults) is appealing both because of its apparent simplicity as well as its ability to preserve consumer autonomy. However, while this strategy seems promising, it is not without practical challenges for implementation. Included among these challenges are food-supply-chain issues, changing restaurant operating practices and training, economics, and the general acceptability of healthy defaults by consumers. In addition, healthy defaults may not work equally well across the many different food-service contexts prevalent in the marketplace today.

One of the most compelling features of the healthy default approach is that nutritional profiles of meals purchased can be improved without the need for extensive consumer knowledge or education. Simply offering a healthy option as a default meal item can increase the probability that consumers will purchase the healthy item. This may be particularly important when considering the current childhood obesity epidemic. Small changes in caloric intake can reduce excessive weight gain over time, which might help reverse current trends. Healthy defaults are a noninvasive approach to reducing caloric intake among children. In addition, for those consumers who may be looking to select a healthy item, having healthy defaults can reduce cognitive load such that consumers do not need to spend cognitive energy when trying to select a healthy choice from multiple menu items.

Another compelling feature of this approach is that it can potentially be cost neutral for both consumers and food-service providers. While overall cost neutrality has been demonstrated in some settings (e.g., present study; personal communication, Disney Food and Beverage Manager, 2013; Anzman-Frasca et al. 2015), it is too early to generalize such findings to all restaurant settings. Large food-service establishments, such as chain restaurants, that deal with substantial food volume may have greater flexibility in their food-supply-chain, storage, and waste-disposal systems such that changing ingredient purchase and inventory may have little impact on overall food-purchase economics. Smaller establishments with more limited scope and capacity may struggle with the impact of substantial changes in ingredient purchase due to, for example, shorter shelf life, and the need to refrigerate fresh ingredients. In addition, making substantial menu changes of any kind requires changes in staff training and operating procedures, as well as changes in menu boards and menus and, potentially, advertising. In addition to the operational requirements imposed by adopting healthy defaults, food establishments will need to invest in identifying which particular defaults would be most acceptable to consumers within the context of their establishments. Such consumer testing may not be typical, especially in smaller establishments, and this may add to the overall investment required to make a menu change. All of these financial costs would need to be accounted for in the overall economic model for healthy defaults.

The impact of restaurant context on consumer acceptance and effectiveness of healthy defaults is also an area that needs further exploration. Healthy defaults were more widely accepted in QSR establishments compared to TSR locations in Walt Disney World theme park, as reported in this article. While it was not possible to determine the reason for this difference, the healthy default paradigm may fit better with the quick-service format where speed and convenience are main drivers of purchase behavior. In the QSR setting, consumers don’t want to invest a lot of time and energy in making a food selection, thereby providing an ideal context for using healthy defaults. The TSR context is different and may be seen by consumers as more of an “indulgent” or special setting, which may mean that elements other than speed and convenience drive decision making. Successfully implementing healthy defaults in the TSR setting may require a different approach, such as improving the nutritional composition of menu items in small incremental ways over time such that menu changes are less prominent and potentially more likely to be consumer acceptable.

The present study captures food selection behavior at different restaurant types, but it does not capture actual food consumption. Along with affecting the selection of healthy defaults, contextual differences between QSRs and TSRs can potentially affect consumers’ consumption of healthy defaults (and food in general). For example, one study examining the effect of plate material on food consumption revealed that serving food on disposable plates results in greater food waste and less food consumption, whereas the reverse is true when serving food on permanent plates (Williamson, Block, and Keller 2016). Since QSRs typically provide food in disposable containers/plates and TSRs typically provide food on permanent plates, the absolute amount of food consumed could vary based on the plate/restaurant type. The unit size of food (such as the size of a pizza slice) and the size of the table at which food is served may also affect consumption. One study showed that serving food in a smaller unit size decreased calorie consumption; however, when the food (pizza) was served on a larger table, participants consumed more calories than when the food was served on a smaller table (Davis, Payne, and Bui 2016). Therefore, both the unit size of food and the size of the table at which the food is served can also affect food consumption. Additional research focusing on healthy defaults could also examine how manipulating these contexts affects the actual consumption (as opposed to the selection) of healthy defaults.

Healthy defaults have been described as one way to “nudge” consumers into making a healthy choice without taking away their autonomy to “opt out” and select something other than the default (Thaler and Sunstein 2008). The notion of preserving consumer choice in this context would seem to be a strong argument that the default strategy does not violate any ethical boundaries. However, not everyone agrees with this point of view, and there are objections to implementation of nudges (White 2013), especially when there is general distrust of the party doing the nudging (e.g., the government) or when the nudges are out of line with widely held social values, or are seen as illicit or unambiguously manipulative (Sunstein 2015). However, potential ethical objections concerning healthy defaults would seem to be rather weak as long as it is clear to consumers at the point of purchase that they have freedom to choose something else instead. Furthermore, the current defaults in restaurants were not selected by some kind of democratic process but were likely the outcome of market forces so that individuals were only indirectly involved (through their purchasing behavior) in selections that appear on the menu. If a restaurant chooses to change its default menu offerings, it would seem to be perfectly within the scope of their authority to do so. Some may object to the government playing this role because it is not seen as a player in the free market and may raise the specter of a “nanny state.”

One example of such government involvement was the implementation on March 12, 2013, in New York City of a ban on the sale of soft drinks greater than 16 ounces in volume (Lerner 2012; the ban on large soft drinks was later rejected by the state’s highest court in June of 2014). This situation is different from that of a healthy default, as consumers did not have a choice to opt out to select a larger size. By contrast, the recent ordinance passed in Davis, California (Doan 2015), requiring that all kids’ meals be served with water or milk is different because it allows parents to opt out of the default and to select juice or a soft drink if they desire.

Despite mounting evidence that healthy defaults can positively affect food choice in restaurant and food-service settings, there are still a number of questions that warrant further research. For example, most studies to date have looked only at food selection, not actual food consumption. It is possible that healthy defaults are accepted by consumers but are not actually consumed and find their way into the waste stream. More data are needed on whether healthy defaults work equally well for adult meals in different restaurant settings including chain restaurants, single-site establishments, and across different food genres (e.g., American, Italian). Can healthy defaults work in community restaurants that have repeat customers once the initial novelty wears off and people are more aware of the default scheme? Research examining the scalability of healthy defaults is also needed. What is the breaking point at which these defaults are not a financially viable option for restaurant owners and/or consumers? For example, what volume of food turnover and customer turnover is required to make healthy defaults cost neutral?

Whether or not healthy defaults in restaurants will be more broadly adopted in the future remains to be seen. As with most social change movements (Economos et al. 2001), the process of change takes time and involves many small local experiments to build the evidence base for the consumer appeal, net benefit, and economic viability of the change. Healthy defaults are in the early stages of being explored in different restaurant settings across the country. The successful expansion of such efforts may be aided by the larger social movement underway that is focused on improving the nutritional value of the food supply (Hysjulien 2012). This movement will depend on the same critical elements for success as for healthy defaults, namely, consumer acceptability and economic viability.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Walt Disney Company and by the National Institutes of Health (grant no. DK48520). The Walt Disney Company and the National Institutes of Health had no role in the design, analysis, or writing of this article.

Footnotes

JP made substantial contributions to study design and acquisition of study data, assisted in interpretation of data, wrote the first draft of the article, and reviewed all subsequent drafts. JB assisted in data analysis and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. JL and ZP were involved in analysis and interpretation of the data. MC and KA participated in study design and data interpretation and reviewed all article drafts. JH participated in study conception, design, and acquisition of study data; assisted in interpretation of data; and reviewed all article drafts.

Full disclosure: JH is a consultant for the Walt Disney Company and for McDonalds; KA is a consultant for the Walt Disney Company.

Contributor Information

JOHN PETERS, Professor, Anschutz Health and Wellness Center, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, 12348 E. Montview Blvd., Mailbox C263, Aurora, CO 80045.

JIMIKAYE BECK, Professional research assistant, Anschutz Health and Wellness Center, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, 12348 E. Montview Blvd., Mailbox C263, Aurora, CO 80045.

JAN LANDE, Professional research assistant, Anschutz Health and Wellness Center, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, 12348 E. Montview Blvd., Mailbox C263, Aurora, CO 80045.

ZHAOXING PAN, Associate professor, Department of Pediatrics, 13001 E. 17th Place, B119, Aurora, CO 80045.

MICHELLE CARDEL, Assistant professor, Department of Outcomes and Policy, University of Florida, 1329 SW 16th Street, Gainseville, FL 32608.

KEITH AYOOB, Associate clinical professor, Department of Pediatrics, Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University, Louis and Dora Rousso Building, 1165 Morris Park Ave., Room 438, Bronx, NY 10461.

JAMES O. HILL, Professor, Anschutz Health and Wellness Center, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, 12348 E. Montview Blvd., Mailbox C263, Aurora, CO 80045

References

- Anzman-Frasca Stephanie, Dawes Franciel, Sliwa Sarah, Dolan Peter R, Nelson Miriam E, Washburn Kyle, Economos Christina D. Healthier Side Dishes at Restaurants: An Analysis of Children’s Perspectives, Menu Content, and Energy Impacts. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2014;11(1):81. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzman-Frasca Stephanie, Mueller Megan P, Sliwa Sarah, Dolan Peter R, Harelick L, Roberts Susan B, Washburn Kyle, Economos Christina D. Changes in Children’s Meal Orders Following Healthy Menu Modifications at a Regional US Restaurant Chain. Obesity. 2015;23(5):1055–62. doi: 10.1002/oby.21061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batada Ameena, Bruening Meg, Marchlewicz Elizabeth H, Story Mary, Wootan Margo G. Poor Nutrition on the Menu: Children’s Meals at America’s Top Chain Restaurants. Childhood Obesity. 2012;8(3):251–54. doi: 10.1089/chi.2012.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berning Joshua P, Couinard Hayley H, McCluskey Jill J. Do Positive Nutrition Shelf Labels Affect Consumer Behavior? Findings from a Field Experiment with Scanner Data. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2011;93(2):364–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman Mary. Wendy’s Removes Soda Option from Kids’ Meal. USA Today. 2015 Jan 15; [Google Scholar]

- Brownell Kelly D. Thinking Forward: The Quicksand of Appeasing the Food Industry. PLoS Med. 2012;9(7):e1001254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celentano Domenick. Restaurant Formats—Starting a Restaurant? Here Are the Basics. 2015 http://foodbeverage.about.com/od/StartingAFoodBusiness/qt/Restaurant-Formats-Starting-A-Restaurant-Here-Are-The-Basics.htm.

- Chapman Gretchen B, Li Meng, Colby Helen, Yoon Haewon. Opting In vs. Opting Out of Influenza Vaccination. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304(1):43–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxe Stefany, West Stephen G, Aiken Leona S. The Analysis of Count Data: A Gentle Introduction to Poisson Regression and Its Alternatives. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2009;91(2):121–36. doi: 10.1080/00223890802634175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis Brennan, Payne Collin R, Bui My. Making Small Food Units Seem Regular: How Larger Table Size Reduces Calories to Be Consumed. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research. 2016;1(1) in this issue. [Google Scholar]

- Doan Claire. Davis Makes Water, Milk Default in Kids’ Meals. 2015 http://www.kcra.com/news/local-news/news-sacramento/davis-makes-water-milk-default-in-kids-meals/33252540.

- Dotsch Mariska, Busch Johanneke, Batenburg Max, Liem Gie, Tareilus Erwin, Mueller Rudi, Meijer Gert. Strategies to Reduce Sodium Consumption: A Food Industry Perspective. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2009;49(10):841–51. doi: 10.1080/10408390903044297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs Julie S, Loewenstein George, Wisdom Jessica. Strategies for Promoting Healthier Food Choices. American Economic Review. 2009;99(2):159–64. doi: 10.1257/aer.99.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economos Christina D, Brownson Ross C, DeAngelis Michael A, Foerster Susan B, Foreman Carol Tucker, Gregson Jennifer, Kumanyika Shiriki K, Pate Russell R. What Lessons Have Been Learned from Other Attempts to Guide Social Change? Nutrition Reviews. 2001;59(3 Part 2):S40–S65. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2001.tb06985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman David H. How Junk Food Can End Obesity. Atlantic. 2013 Jul-Aug [Google Scholar]

- Gimbel Ronald W, Strosberg Martin A, Lehrman Susan E, Gefenas Eugenijus, Taft Frank. Presumed Consent and Other Predictors of Cadaveric Organ Donation in Europe. Progress in Transplant. 2003;13(1):17–23. doi: 10.1177/152692480301300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittlesohn Joel, Lee Katherine. Integrating Educational, Environmental, and Behavioral Economic Strategies May Improve the Effectiveness of Obesity Interventions. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. 2013;35(1):52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern Scott D, Ubel Peter A, Asch David A. Harnessing the Power of Default Options to Improve Health Care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(13):1340–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb071595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearst Mary O, Harnack Lisa J, Bauer Katherine W, Earnest Alicia A, French Simone A, Michael Oakes J. Nutritional Quality at Eight U.S. Fast-Food Chains: 14-Year Trends. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44(6):589–94. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill James O, Peters John C. Environmental Contributions to the Obesity Epidemic. Science. 1998;280(5368):1371–74. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5368.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill James O, Peters John C, Wyatt Holly R. Using the Energy Gap to Address Obesity: A Commentary. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2009;109(11):1848–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hysjulien Liam. master’s thesis. University of Tennessee; Knoxville: 2012. Growing a Local Movement: New Social Movements, Food, and Activism. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Eric J, Goldstein Daniel G. Medicine: Do Defaults Save Lives? Science. 2003;302(5649):1338–39. doi: 10.1126/science.1091721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Eric J, Goldstein Daniel G. Defaults and Donation Decisions. Transplantation. 2004;78(12):1713–16. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000149788.10382.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just David R, Mancino Lisa, Wansink Brian. Economics Research Report No. 43. Economic Research Service, US Department of Agriculture; Washington, DC: 2007. Could Behavioral Economics Help Improve Diet Quality for Nutrition Assistance Participants? [Google Scholar]

- Just David R, Wansink Brian. The Flat-Rate Pricing Paradox: Conflicting Effects of ‘All-You-Can-Eat’ Buffet Pricing. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2011;93(1):193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Just David R, Wansink Brian. One Man’s Tall Is Another Man’s Small: How the Framing of Portion Size Influences Food Choice. Health Economics. 2014;23(7):776–91. doi: 10.1002/hec.2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick Sharon I, Reedy Jill, Kahle Lisa L, Harris Jennifer L, Ohri-Vachaspati Punam, Krebs-Smith Susan M. Fast-Food Menu Offerings Vary in Dietary Quality, but Are Consistently Poor. Public Health Nutrition. 2014;17(4):924–31. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012005563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korobkin Russell. The Status Quo Bias and Contract Default Rules. Cornell Law Review. 1998;83(3):608–87. [Google Scholar]

- Laroche Helena H, Ford Christopher, Hansen Kate, Cai Xueya, Just David R, Hanks Andrew S, Wansink Brian. Concession Stand Makeovers: A Pilot Study of Offering Healthy Foods at High School Concession Stands. Journal of Public Health (Oxford) 2014 Mar;:1–9. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdu015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner George. New York Health Board Approves Ban on Large Sodas. 2012 http://www.cnn.com/2012/09/13/health/new-york-soda-ban/

- Loewenstein George, Brennan Troyen, Volpp Kevin G. Asymmetric Paternalism to Improve Health Behaviors. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(20):2415–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCluskey Jill J, Mittelhammer Ron C, Asiseh Fafanyo. From Default to Choice: Adding Healthy Options to Kids’ Menus. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2012;94(2):338–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pham Nguyen, Mandel Naomi, Morales Andrea C. Messages from the Food Police: How Food-Related Warnings Backfire among Dieters. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research. 2016;1(1) in this issue. [Google Scholar]

- Poti Jennifer M, Popkin Barry M. Trends in Energy Intake among US Children by Eating Location and Food Source, 1977–2006. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2011;111(8):1156–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell Lisa M, Nguyen Binh T. Fast-Food and Full-Service Restaurant Consumption among Children and Adolescents: Effect on Energy, Beverage, and Nutrient Intake. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics. 2013;167(1):14–20. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson William, Zeckhauser Richard. Status Quo Bias in Decision Making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 1988 Mar;1:7–59. [Google Scholar]

- Story Mary, Kaphingst Karen M, Robinson-O’Brien Ramona, Glanz Karen. Creating Healthy Food and Eating Environments: Policy and Environmental Approaches. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008 Apr;29:253–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein Cass R. Do People Like Nudges? 2015 http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2604084.

- TEA/AECOM. Global Attractions Attendance Report 2011. Themed Entertainment Association and the Economics Practice at AECOM. 2012 http://www.teaconnect.org/images/files/TEA_26_543179_140617.pdf.

- Thaler Richard H, Sunstein Cass R. Libertarian Paternalism. American Economic Review. 2003;93(2):175–79. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler Richard H, Sunstein Cass R. Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thorgeirsson Tryggvi, Kawachi Ichiro. Behavioral Economics: Merging Psychology and Economics for Lifestyle Interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44(2):185–89. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike Anne N, Riis Jason, Sonnenberg Lillian M, Barraclough Susan, Levy Douglas E. A 2-Phase Labeling and Choice Architecture Intervention to Improve Healthy Food and Beverage Choices. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(3):527–33. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walt Disney Company. The Walt Disney Company. 2013 http://thewaltdisneycompany.com/citizenship/responsible-content/magic-healthy-living.

- Wang Youfa, Beydoun May A. The Obesity Epidemic in the United States—Gender, Age, Socioeconomic, Racial/Ethnic, and Geographic Characteristics: A Systematic Review and Meta-regression Analysis. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2007;29(1):6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink Brian. Package Size, Portion Size, Serving Size … Market Size: The Unconventional Case for Half-Size Servings. Marketing Science. 2012;31(1):54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wansink Brian, Hanks Andrew S. Calorie Reductions and within-Meal Calorie Compensation in Children’s Meal Combos. Obesity. 2014;22(3):630–32. doi: 10.1002/oby.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink Brian, Johnson Katherine A. The Clean Plate Club: About 92% of Self-Served Food Is Eaten. International Journal of Obesity. 2014 Jul;39:371–74. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink Brian, van Ittersum Koert. Fast Food Restaurant Lighting and Music Can Reduce Calorie Intake and Increase Satisfaction. Psychological Reports. 2012;111(1):228–32. doi: 10.2466/01.PR0.111.4.228-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink Brian, van Ittersum Koert. Portion Size Me: Plate-Size Induced Consumption Norms and Win-Win Solutions for Reducing Food Intake and Waste. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 2013;19(4):320–32. doi: 10.1037/a0035053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Mark D. The Manipulation of Choice: Ethics and Libertarian Paternalism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson Sara, Block Lauren G, Keller Punam A. Of Waste and Waists: The Effect of Plate Material on Food Consumption and Waste. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research. 2016;1(1) in this issue. [Google Scholar]

- Wisdom Jessica, Downs Julie S, Loewenstein George. Promoting Healthy Choices: Information Versus Convenience. American Economic Journal—Applied Economics. 2010;2(2):164–78. [Google Scholar]