Abstract

Introduction

This study was designed to assess real-world outcomes of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who were stable on interferon (IFN) beta therapy in the year prior to switching to another IFN beta therapy versus those who continued on the initial treatment.

Methods

This study used administrative claims from MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, from January 1, 2010, to March 31, 2015, to identify MS patients aged 18–64 years who remained relapse free for at least 1 year while continuously treated with an IFN beta therapy. Stable patients remaining on their initial IFN beta therapy (no-switch patients) were matched with stable patients who switched IFN beta therapy (switch patients) using propensity score matching (first claim = index date). Outcome measures included annualized relapse rate (ARR), the percentage of patients who relapsed, medication possession ratio, and the proportion of days covered and were measured during the year following the index date.

Results

This study identified 531 patients in the no-switch group and 177 patients in the switch group, with subsets of 270 patients in the no-switch group and 90 patients in the switch group stable on intramuscular (IM) IFN beta-1a therapy. All outcomes during the follow-up year were significantly better in the no-switch group than in the switch group. For all patients, ARR in the switch group was more than twice that in the no-switch group (P = 0.002). For patients stable on IM IFN beta-1a at baseline, ARR was twice as high in the switch group as in the no-switch group (P = 0.012).

Conclusion

Among all patients stable on IFN beta therapy and the subset stable on IM IFN beta therapy in particular, those who remained on therapy had significantly better outcomes than those who switched to another IFN beta therapy.

Funding

Biogen (Cambridge, MA, USA).

Keywords: Efficacy, Interferon beta-1a, Neurology, Outcomes, Relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic and often disabling disease affecting approximately 400,000 people in the USA [1]. The most common clinically presenting type of MS, relapsing–remitting MS, is characterized by intermittent relapses with intervening periods of clinical remission; in most patients, there is an accumulation of sustained disability over time [1, 2]. Although no cure exists, treatment with disease-modifying therapy (DMT) may reduce the number of relapses a patient experiences and slow the rate of disability accumulation [1, 3].

Interferon (IFN) beta therapies are recommended as first-line DMTs for relapsing forms of MS in more than 80 countries. These therapies are self-administered subcutaneously (SC) or intramuscularly (IM), with a dosing frequency ranging from three times a week to once every 2 weeks depending on the medication formulation [4–8]. Adherent use of DMTs provides benefit for long-term patient outcomes by reducing relapses and delaying sustained worsening [1, 9], enhancing quality of life [10, 11], and reducing the impact of MS on healthcare resources and costs [9, 12].

Despite the established efficacy of IFN beta therapy, long-term adherence and persistence remain a challenge [3, 10, 11, 13, 14]. Discontinuation rates for nonadherent patients in previous studies have ranged from less than 20% to 50% [1], with the risk of treatment discontinuation highest within the first 6 months to 2 years of therapy [15, 16]. Barriers to persistence with IFN beta therapy include psychological factors (e.g., depression and anxiety), clinical factors (e.g., symptomatic and metabolic tolerability), cognitive impairment, treatment fatigue, complex or frequent dosing regimens, disease worsening, the presence of neutralizing antibodies, and financial and physical factors (e.g., co-payments and the need for self-injections) [1, 10, 11, 17, 18].

While many physicians advocate switching treatments once a patient with MS experiences one or more relapses while using an injectable DMT, it is not clear how switching IFN beta therapy affects outcomes in stable patients with MS who are relapse free.

The present study used real-world data from a US claims database to identify patients with MS who were stable (relapse free for 1 year prior) on any IFN beta therapy and a subset of patients who were stable on IM IFN beta-1a and assessed their outcomes after switching IFN beta therapy versus staying on the initial IFN beta therapy. Outcomes were measured by annualized relapse rate (ARR), the percentage of patients who relapsed, treatment adherence, and persistence.

Methods

Data Acquisition

This study involved a retrospective analysis of approximately 174 million unique de-identified patients (from as early as 1995) in the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (CCE) Database, a medical and drug insurance claims database, including active employees, early retirees, COBRA continuers, and dependents insured by employer-sponsored plans. The database was established in 1988 and contains inpatient admission records, outpatient services, prescription drugs, populations, eligibility status, and costs of services [19].

Patient Selection and Study Design

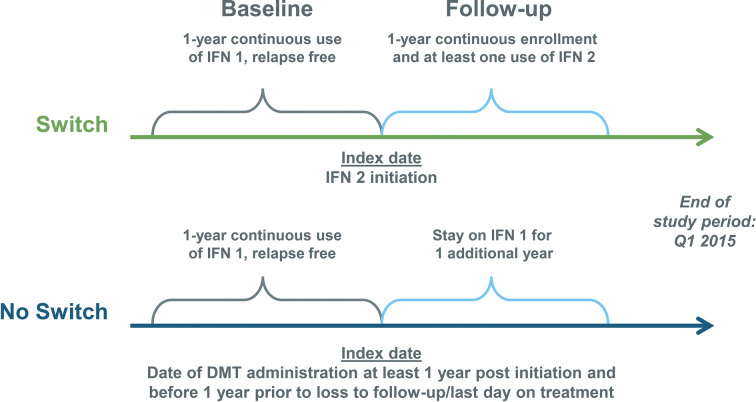

The study population was identified from the MarketScan CCE Database using administrative claims data, from January 1, 2010, to March 31, 2015, for patients with MS (defined as having at least one MS diagnosis [ICD-9: 340] within the year prior to initiating an IFN beta therapy), aged 18–64 years, who were relapse free for at least 1 year while continuously treated with IFN beta therapy (SC IFN beta-1a, SC IFN beta-1b, or IM IFN beta-1a). Patients also had to be continuously enrolled for 1 year prior to the index date (first claim = index date; baseline) and 1 year after the index date (follow-up) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study design. DMT disease-modifying therapy, IFN 1 initial interferon therapy, IFN 2 second interferon therapy

Patient Matching

Patients were propensity score matched 3:1, using the greedy method, for those who stayed on their baseline therapy (no-switch) versus those who switched to another IFN therapy (switch). Exact matching was based on the following: age category, sex, month/year of index date (first claim = index date), previous IFN used, and the prior year’s adherence category (medication possession ratio [MPR], < 0.6, 0.6–0.7, ≥ 0.8).

Among switch patients who were matched in terms of the above categories, the three closest no-switch patients were selected on the basis of a logistic propensity model using the above characteristics, as well as insurance plan type, the number of doctor visits in the year prior to the index date, total medical costs (log transformed), and MS symptoms as defined by experts in the field.

Among patients in each group, the Charslon comorbidity index [20] was using to assess the extent of comorbidities.

Adherence

Adherence was assessed using patient refill records to ascertain the MPR (defined as the sum of all days’ supplies for all fills of the drug in a particular time period [pre or post index date], divided by the number of days in the time period) and the proportion of days covered (PDC; defined as the number of covered days in a particular time period divided by the total number of days in the time period).

Relapses

The operational definition of relapses, adapted from Chastek et al. [2], included any inpatient hospital stay with a primary diagnosis of MS or any outpatient visit (either an emergency room or office visit) with the use of corticosteroids (high dose of oral steroid [daily dose of ≥ 500 mg prednisone] or intravenous steroid), adrenocorticotropic hormone, or total plasma exchange within 30 days after the stay and/or visit.

Statistical Analysis

Outcomes were compared for switch versus no-switch groups for patients stable on any IFN beta therapy at baseline and then for the subset of patients stable on IM IFN beta-1a at baseline. Descriptive statistics were provided for cohorts before and after matching. Mean and standard deviation were presented for continuous measures, and count and proportion were presented for categorical measures.

Statistical testing was conducted to detect statistically significant difference (i.e., P < 0.05) between switch and no-switch groups before and after matching. Comparisons between treatment groups were analyzed using the chi-squared test or Fisher exact test for categorical measures and nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous measures (e.g., costs).

Ethics

The data contained in the MarketScan CCE Database are statistically de-identified and have been certified to satisfy the conditions set forth in section 164.514 (a)–(b)1ii of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. As such, the patient information used in this study is exempt from the US Department of Health and Human Services regulations that require institutional review board approval, and patient consent was not deemed necessary.

Results

Patients

After matching patients stable on any IFN beta therapy (SC IFN beta-1a, SC IFN beta-1b, or IM IFN beta-1a), there were 531 patients in the no-switch group and 177 patients in the switch group. For the subgroup of patients stable on IM IFN beta-1a therapy, after matching there were 270 patients in the no-switch group and 90 patients in the switch group.

Baseline characteristics were well matched between groups (Table 1). The time between the previous claim and the index claim was similar for switch and no-switch patients (e.g., there was no gap in treatment when switching therapies in the switch group).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Patients stable on any IFN beta therapy | Patients stable on IM IFN beta-1a therapy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before matching | After matching | Before matching | After matching | |||||

| No switch (n = 11,488) | Switch (n = 188) | No switch (n = 531) | Switch (n = 177) | No switch (n = 5673) | Switch (n = 93) | No switch (n = 270) | Switch (n = 90) | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 49.3a (9.2) | 46.3a (9.9) | 47.5 (9.9) | 46.9 (9.6) | 50.4 (8.8) | 46.0a (10.1) | 47.3 (9.9) | 46.5 (9.9) |

| Female, % | 75.8 | 77.1a | 78.5 | 78.5 | 78.0 | 79.6 | 80.0 | 80.0 |

| Baseline treatment, % | ||||||||

| IM IFN beta 1a (Avonex®) | 49.4 | 49.5 | 50.8 | 50.8 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| SC IFN beta 1a (Rebif®) | 31.6 | 24.5 | 24.9 | 24.9 | – | – | – | – |

| SC IFN beta 1b (Betaseron®) | 19.0 | 26.1 | 24.3 | 24.3 | – | – | – | – |

| Any inpatient stays at baseline, % | 3.3 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 2.2 |

| Any ER visits at baseline, % | 13.9 | 15.4 | 15.6 | 15.3 | 13.6 | 11.8 | 12.2 | 11.1 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, % | ||||||||

| 0 | 78.5 | 77.7 | 76.1 | 78.5 | 78.6 | 79.6 | 77.4 | 81.0 |

| 1 | 8.1 | 6.9 | 8.5 | 7.3 | 8.0 | 6.5 | 8.5 | 7.0 |

| 2 | 9.7 | 11.2 | 12.1 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 12.9 | 9.6 | 11.0 |

| 3+ | 3.7 | 4.3 | 3.4 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 1.1 | 4.4 | 1.0 |

| Interval between last pill access and index date, mean, days | 9.1 | 14.3 | 15.3 | 20.5 | 7.5 | 11.3 | 10.3 | 17.1 |

For the IM IFN beta-1a therapy group, the three patients that were unmatched were significantly younger than the matched population

ER emergency room, IFN interferon, IM intramuscular, SC subcutaneous, SD standard deviation

aP < 0.05 versus no-switch group

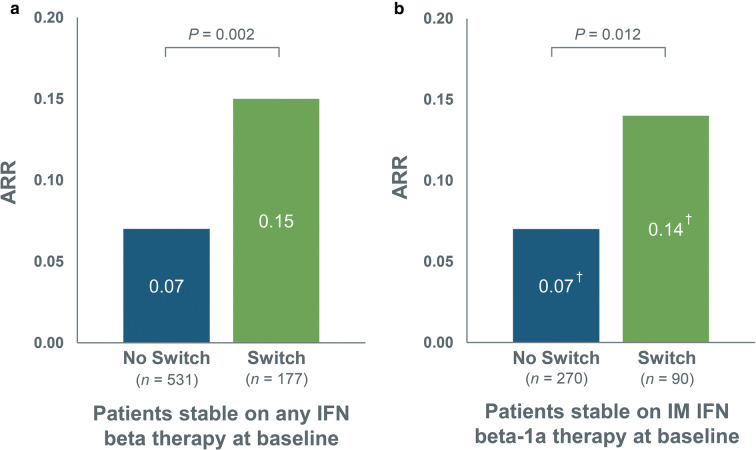

ARR

For patients who were stable on any IFN beta therapy at baseline, the ARR in the switch group was more than twice that in the no-switch group (P = 0.002). In the subgroup of patients who were stable on IM IFN beta-1a therapy at baseline, the ARR was twice as high in the switch group as in the no-switch group (P = 0.012) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Annualized relapse rate during 1-year follow-up for no-switch and switch patients among a patients stable on any IFN beta therapy* at baseline and b patients stable on IM IFN beta-1a therapy at baseline. IFN interferon, IM intramuscular, SC subcutaneous, SD standard deviation. *SC IFN beta-1a, SC IFN beta-1b, or IM IFN beta-1a. †SD = 0.30 for no-switch group and SD = 0.35 for switch group; SD unavailable for IM IFN beta-1a subgroup

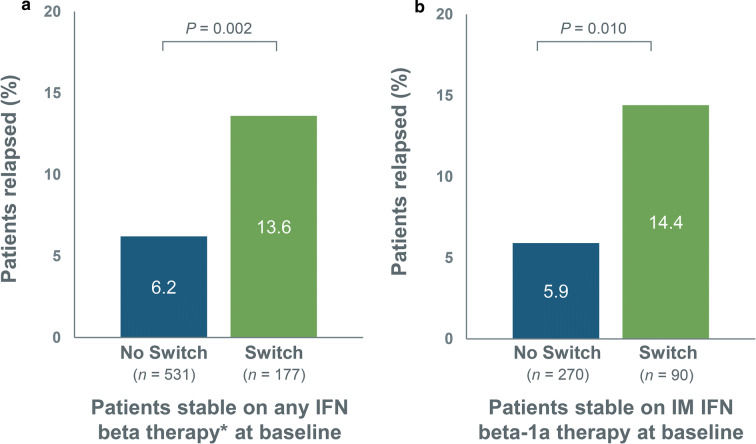

Percentage of Patients Relapsed

The percentage of patients experiencing a relapse during the follow-up year was significantly higher in the switch group than in the no-switch group for patients stable on any IFN beta therapy at baseline, as well as in the subset of patients stable on IM IFN beta-1a therapy at baseline (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of patients relapsed during 1-year follow-up for no-switch and switch groups among a patients stable on any IFN beta therapy* at baseline and b patients stable on IM IFN beta-1a therapy at baseline. IFN interferon, IM intramuscular, SC subcutaneous. *SC IFN beta-1a, SC IFN beta-1b, or IM IFN beta-1a

Among patients stable on any IFN beta therapy at baseline, switch patients were 1.9 times more likely than no-switch patients to have at least one relapse (P = 0.002). Similarly, in the subgroup of patients stable on IM IFN beta-1a therapy at baseline, switch patients were 2.4 times more likely than no-switch patients to have at least one relapse (P = 0.010).

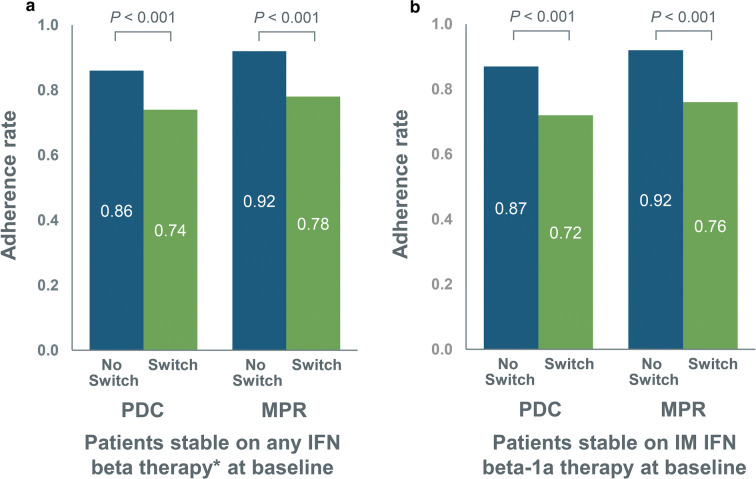

Adherence

Patients who were stable on any IFN beta therapy at baseline who switched had significantly lower MPR and PDC post index date than no-switch patients (Fig. 4a). Since MPR was categorically used as a matching variable, baseline adherence rates were similar; however, the switch cohort had a significantly lower MPR post index than the no-switch cohort (0.78 vs. 0.92; P < 0.001). An alternate measure, PDC, showed similar findings. This was driven by the switch patients not being persistently adherent to the switch medication (e.g., not staying on their medication for the entire 1-year follow-up).

Fig. 4.

Adherence rates during 1-year follow-up for no-switch and switch patients among a patients stable on any IFN beta therapy* at baseline and b patients stable on IM IFN beta-1a therapy at baseline. IFN interferon, IM intramuscular, MPR medication possession ratio, PDC proportion of days covered, SC subcutaneous. *SC IFN beta-1a, SC IFN beta-1b, or IM IFN beta-1a

Similar results were seen for the subgroup stable on IM IFN beta-1a therapy at baseline, with the switch group having significantly lower MPR and PDC post index date than the no-switch group (Fig. 4b). As MPR was categorically used as a matching variable, baseline adherence rates were similar; however, the switch cohort had a significantly lower MPR post index than the no-switch group (0.76 vs. 0.92; P < 0.001). Adherence measured using PDC showed similar results. Again, this was driven by the switch patients not being persistently adherent to the second medication.

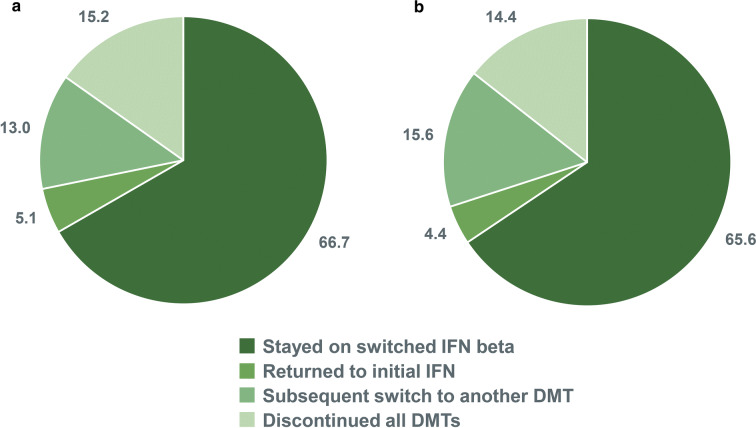

Treatment Persistence for the Switch Group

During the follow-up period, the majority of switch patients continued with the second IFN therapy (Fig. 5); approximately one-third discontinued or switched to another DMT, and 4–5% returned to treatment with their initial IFN beta therapy.

Fig. 5.

DMTs administered during the follow-up period (as percentage of patients) in a patients stable on any IFN beta therapy* at baseline and b patients stable on IM IFN beta-1a therapy at baseline (switch cohort only). DMT disease-modifying therapy, IFN interferon, IM intramuscular. *IFN beta therapies included SC IFN beta-1a, SC IFN beta-1b, and IM IFN beta-1a

Of the patients who stayed on the switched DMT (66.7%), approximately 12% experienced a relapse. The ARR was 0.12.

Discussion

All clinically stable IFN beta therapy patients who remained on their initial therapy had significantly better outcomes than those who switched to another IFN, with a 54% lower percentage of patients who relapsed and a 53% lower ARR compared with patients who switched. The subset of patients stable on IM IFN beta-1a who remained on therapy had similar results and showed significantly better outcomes than those who switched to another IFN (i.e., a lower percentage of patients experiencing a relapse [5.9% vs. 14.4%; P = 0.010] and a lower ARR [0.07 vs. 0.14; P = 0.012]).

It is important to note that almost half of the stable IFN patients in this study were on IM IFN beta-1a therapy, which may have driven the results, including higher adherence [11]. Published research has demonstrated that patients taking IM IFN beta-1a have higher adherence rates than patients taking other injectable DMTs, which may be in part the result of a lower injection frequency [11, 21].

Patients who switched exhibited poorer adherence to the new treatment during the follow-up period. Approximately one-third of the patients made a further DMT switch returned to their baseline IFN/IM IFN beta-1a therapy or discontinued DMT therapy altogether. For those patients who continued on the switched DMT, the ARR remained still higher relative to those patients who did not switch, suggesting that these outcomes may not be solely driven by adherence to the switch medication.

The current study appears to be the first to assess the effects of remaining on initial IFN beta therapy compared with switching to another IFN beta therapy. In contrast to the results of our study, in a study of patients who switched from first-line IFN beta therapy (SC IFN beta-1a, IM IFN beta-1a, or SC IFN beta-1b) or SC glatiramer acetate to either a different IFN beta or a second-line therapy following a relapse or disability progression, there was no difference among switching groups in terms of time to relapse or time to an Expanded Disability Status Scale score of 4.0 [22]. This latter patient population differs from that in our study in that our cohort had been clinically stable prior to the medication switch.

Limitations of the Study

One limitation of the study is that administrative claims data do not distinguish between the different subtypes of MS. In addition, baseline disease severity was not available to use as a matching criterion. Information on patients’ reasons for switching was also not available in the claims data. Reasons for switching other than disease activity may have included occurrence of new side effects or changes in insurance or clinician. Some patients may have switched IFN type because of disease activity not captured in this study, such as a change in magnetic resonance imaging scans or a mild relapse that did not result in acute intervention with corticosteroids, adrenocorticotropic hormone, or plasma exchange. This may have led to an underestimation of relapses and their impact of ARR. Finally, determination of the stage of disease progression and disability status among patients was not possible.

Our data, derived from commercial health insurance claims, may not be generalizable to that obtained from other types of health insurance or from chart reviews from clinic settings. Finally, there was no patient- or physician-reported effectiveness measure that could have been incorporated to confirm relapse occurrence or its severity.

Conclusions

This study, which used real-world claims data to compare outcomes in patients with MS, demonstrates the benefits of stable (relapse-free) patients remaining on their current IFN beta therapy. These data also suggest that IFN beta therapies may not be interchangeable in stable patients, which would support having multiple IFN beta choices available (e.g., no formulary limitations) in clinical practice. The results of this study are of value in demonstrating that the practice of switching stable patients to a different in-class medication may be of significant detriment to patients’ well-being, at least as indicated by the increased risk of relapses. These data may aid in future treatment decision-making for relapse-free MS patients and their healthcare providers.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The study was sponsored by Biogen (Cambridge, MA, USA). Biogen also funded the article processing charges and open access fees associated with publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. All authors were involved in reviewing the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, had full editorial control of the manuscript, and provided final approval of the submitted version.

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance

The authors wish to thank Jonathan Kendter, who helped to design the study. The authors were assisted in the preparation of the manuscript by Jenna Steere, Nicholas White, and Joshua Safran of Ashfield Healthcare Communications (New York, NY, and Middletown, CT, USA). Writing and editorial support, including editing and creation of figures and tables, were funded by the study sponsor.

Disclosures

S. Cohan has received research support from, has received speaking honoraria from, and/or serves on advisory boards for Acorda, Biogen, Mallinckrodt, MedDay, Novartis, Opexa, Roche-Genentech, and Sanofi Genzyme. K. Smoot has received honoraria for speaking from Acorda, Biogen, Genentech, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, and Teva (advisory meetings). K. Kresa-Reahl has received honoraria for speaking from Biogen, EMD Serono, Genentech, Mallinckrodt, Novartis, and Teva (advisory meetings). R. Garland was an employee of Biogen at the time the study was carried out and is a Biogen stockholder. W-S. Yeh was an employee of Biogen at the time of these analyses. N. Wu was an employee of Biogen at the time of these analyses. C. Watson was an employee of Biogen at the time of these analyses. W-S. Yeh is now an employee of Genentech and owns stock in Roche. N. Wu is now an employee of NeoPath Healthcare Analytics Inc. C. Watson is now an employee of Atara Biotherapeutics and owns stock in Biogen. Genentech, NeoPath Healthcare Analytics, and Atara Biotherapeutics were not involved in these analyses.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The data contained in the MarketScan CCE Database are statistically de-identified and have been certified to satisfy the conditions set forth in Sects. 164.514 (a)–(b)1ii of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. As such, the patient information used in this study is exempt from the US Department of Health and Human Services regulations that require institutional review board approval, and patient consent was not deemed necessary.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.7127132.

References

- 1.Steinberg SC, Faris RJ, Chang CF, Chan A, Tankersley MA. Impact of adherence to interferons in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a non-experimental, retrospective, cohort study. Clin Drug Investig. 2010;30(2):89–100. 10.2165/11533330-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chastek BJ, Oleen-Burkey M, Lopez-Bresnahan MV. Medical chart validation of an algorithm for identifying multiple sclerosis relapse in healthcare claims. J Med Econ. 2010;13(4):618–25. 10.3111/13696998.2010.523670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lafata JE, Cerghet M, Dobie E, et al. Measuring adherence and persistence to disease-modifying agents among patients with relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(6):752–7. 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avonex [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Biogen Inc.; 1996.

- 5.Betaseron [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; 1993.

- 6.Plegridy [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Biogen Inc.; 2014.

- 7.Rebif [package insert]. Rockland, MA: EMD Serono, Inc.; 1996.

- 8.Extavia [package insert]. Montville, NJ: Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals; 1993.

- 9.Ivanova JI, Bergman RE, Birnbaum HG, Phillips AL, Stewart M, Meletiche DM. Impact of medication adherence to disease-modifying drugs on severe relapse, and direct and indirect costs among employees with multiple sclerosis in the US. J Med Econ. 2012;15(3):601–9. 10.3111/13696998.2012.667027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Treadaway K, Cutter G, Salter A, et al. Factors that influence adherence with disease-modifying therapy in MS. J Neurol. 2009;256(4):568–76. 10.1007/s00415-009-0096-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devonshire V, Lapierre Y, Macdonell R, et al. The Global Adherence Project (GAP): a multicenter observational study on adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18(1):69–77. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03110.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan H, Cai Q, Agarwal S, Stephenson JJ, Kamat S. Impact of adherence to disease-modifying therapies on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with multiple sclerosis. Adv Ther. 2011;28(1):51–61. 10.1007/s12325-010-0093-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menzin J, Caon C, Nichols C, White LA, Friedman M, Pill MW. Narrative review of the literature on adherence to disease-modifying therapies among patients with multiple sclerosis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19:S24–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen K, Schussel K, Kieble M, et al. Adherence to disease modifying drugs among patients with multiple sclerosis in Germany: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133279. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tremlett HL, Oger J. Interrupted therapy: stopping and switching of the beta-interferons prescribed for MS. Neurology. 2003;61(4):551–4. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000078885.05053.7D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rio J, Porcel J, Tellez N, et al. Factors related with treatment adherence to interferon beta and glatiramer acetate therapy in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(3):306–9. 10.1191/1352458505ms1173oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beer K, Muller M, Hew-Winzeler AM, et al. The prevalence of injection-site reactions with disease-modifying therapies and their effect on adherence in patients with multiple sclerosis: an observational study. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:144. 10.1186/1471-2377-11-144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costello K, Kennedy P, Scanzillo J. Recognizing nonadherence in patients with multiple sclerosis and maintaining treatment adherence in the long term. Medscape J Med. 2008;10(9):225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (USA): B.R.I.D.G.E. to data. http://www.bridgetodata.org/node/987. Accessed November 14, 2016.

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen C, Baraban E, Stuchiner T, Kime E, Suh K, Cohan SL. Evaluating medication adherence to disease modifying therapy (DMT) and the associated factors using data from the Pacific Northwest Multiple Sclerosis Registry. Copenhagen: European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Amico E, Leone C, Zanghi A, Fermo SL, Patti F. Lateral and escalation therapy in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a comparative study. J Neurol. 2016;263(9):1802–9. 10.1007/s00415-016-8207-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]