Abstract

Introduction

To characterize the reduction in intraocular pressure (IOP) and IOP-lowering medication use following goniotomy via trabecular meshwork excision performed using the Kahook Dual Blade as a stand-alone procedure in adult eyes with glaucoma uncontrolled on a regimen of 1–3 topical IOP-lowering medications.

Methods

In this retrospective analysis, data from consecutive patients undergoing goniotomy with the Kahook Dual Blade by 11 surgeons were analyzed. Preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative follow-up data through 6 months of follow-up were collected. The primary efficacy endpoint was IOP reduction from preoperative baseline; reduction in IOP-lowering medication use was a secondary endpoint.

Results

Data were collected from 53 eyes of 42 subjects. Mean (± SE) preoperative IOP was 23.5 ± 1.1 mmHg, and from day 1 through 6 months of postoperative follow-up mean IOP reductions of 7.0–10.3 mmHg (29.8–43.8%; p < 0.001 at each time point) were observed. Mean preoperative medication use was 2.5 ± 0.2 medications per eye and was reduced by month 6 to 1.5 ± 0.2 (a 40.0% reduction; p < 0.05). Eyes with higher baseline IOP experienced mean IOP reductions of 13.7 mmHg (− 46.4%) at month 6, while eyes with lower baseline IOP experienced mean IOP reductions of 3.8 mmHg (− 21.0%) at month 6. Mean medications were reduced by 1.3 medications in high-IOP eyes and by 0.9 in low-IOP eyes at month 6. No significant sight-threatening adverse events were observed.

Conclusions

Goniotomy via trabecular meshwork excision performed using the Kahook Dual Blade effectively and safely lowered IOP when performed as a stand-alone procedure in eyes with glaucoma. The significant drop in IOP met or exceeded the recommended targets for these glaucoma patients.

Funding

New World Medical, Inc.

Keywords: Glaucoma, Goniotomy, Intraocular pressure, Micro-incisional glaucoma surgery, Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery, Ophthalmology

Introduction

The trabecular meshwork (TM) is the site of greatest resistance to aqueous outflow, and this outflow resistance is increased in glaucomatous eyes [1]. The concept of modern trabeculectomy was based on this observation and the desire to remove the obstruction to improve aqueous outflow. Cairns envisioned the excision of a block of trabecular tissue as a means to shunt aqueous directly into the two cut ends of Schlemm’s canal, thus restoring the normal outflow pathway [2]. Many successful trabeculectomy surgeries, however, do not result in removal of TM tissue [3, 4]. In reality, trabeculectomy lowers intraocular pressure (IOP) by creating an external fistula into the subconjunctival space. The ensuing filtering bleb provides significant reduction in IOP, but comes at the cost of serious and potentially blinding long-term complications such as hypotony, maculopathy, and endophthalmitis [5].

In recent years, multiple investigators have revisited Cairns’ original notion of bypassing the TM to shunt aqueous humor into Schlemm’s canal using various procedures and/or devices. Some approaches achieve trabecular bypass by incising the TM with little or no actual tissue removal (Trabectome, Trab360, gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy), some by utilizing small-diameter shunts to facilitate flow of aqueous humor across the TM (iStent, Glaukos Corp., San Clemente, CA, USA; Hydrus, Ivantis Inc., Irvine, CA, USA), and some by making small incisions to access Schlemm’s canal for dilation (canaloplasty and VISCO360, Sight Sciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA). Head-to-head trials of these various minimally invasive ab interno glaucoma surgeries have not been widely performed.

Goniotomy via TM excision performed with the Kahook Dual Blade (KDB) is a relatively recent method for trabecular bypass and involves the removal of a strip of TM tissue providing a wide area of unimpeded flow from the anterior chamber into Schlemm’s canal, with no permanent device implanted in the eye. Goniotomy with the KDB is intended to be used for both stand-alone procedures to lower IOP as well as combined with cataract surgery. When goniotomy with the KDB is performed in conjunction with cataract surgery, mean IOP reduction of 26% and mean medication reduction of 44% have been reported at 6 months postoperatively [6]. Here, we report the 6-month outcomes of a retrospective analysis of goniotomy with the KDB as a stand-alone procedure in eyes with glaucoma.

Methods

This was a retrospective analysis of data collected from the medical records of patients with medically treated glaucoma undergoing stand-alone goniotomy via TM excision performed using the KDB for the reduction of IOP. A de-identified data set was analyzed, and the study was granted a waiver of informed consent from a central ethics committee. Data were collected from 11 surgeons at nine sites within the USA and one site in Mexico. The study was not registered as the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) guidelines did not require it.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Subjects included in this analysis were 18–90 years of age, with any form and severity of glaucoma and inadequate IOP control using a stable medical regimen (unchanged for at least 3 months) of at least one and up to three IOP-lowering medications. Indications for surgery included reduction of IOP, reduction of IOP-lowering medications, or both. Both phakic and pseudophakic eyes were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria included recent (within 3 months) laser trabeculoplasty, iridotomy, or initiation of systemic beta-blocker therapy; any eyes with previous intraocular incisional glaucoma surgery; and any uncontrolled systemic conditions that might confound study measurements. Both eyes of a given patient were included if both met these eligibility criteria.

As this was a retrospective study, there was no protocol-specified surgical technique. Each investigator performed goniotomy using the KDB according to the manufacturer’s directions for use. Goniotomy via TM excision performed with the KDB has been described elsewhere [6]. The KDB has a distal tip that pierces the TM, enters Schlemm’s canal, and as it is advanced along the trajectory of the canal, elevates and guides the TM up a ramp and toward two parallel blades that excise a full strip of TM, leaving a clear path for aqueous humor to drain into Schlemm’s canal and the distal collector channels.

Preoperative data collected included patient demographic information (age, gender, ethnicity), glaucoma type and severity, current IOP-lowering medications, past ocular surgical history, relevant systemic medical history, and baseline visual acuity and IOP. Operative data included adverse events. Postoperative data collected was focused on time periods that bracketed postoperative visits (day 1, week 1, months 1, 3, and 6) and included current ocular and systemic medications, visual acuity, IOP, any new adverse events, and any secondary surgical interventions for IOP control. Data through 6 months of follow-up are included in this analysis.

The primary efficacy endpoint for this analysis was reduction in IOP from baseline. A mixed regression model accounting for fellow-eye correlation in bilaterally enrolled subjects was utilized to evaluate IOP changes over time and was adjusted for multiplicity using Bonferroni’s method. Reduction in IOP-lowering medications was a secondary efficacy endpoint and was analyzed using a similar mixed regression model approach. To best characterize success in meeting individual subject goals, a subgroup analysis was conducted to characterize IOP changes and medication changes over time in two subgroups: those with IOP greater than or equal to the median IOP, and those with IOP less than the median IOP. Because the indication for surgery was not uniformly recorded in this retrospective study, it is assumed that the IOP reduction in the higher IOP subgroup approximates the IOP reductions expected in eyes undergoing surgery primarily for IOP reduction, while the medication reduction in the lower IOP subgroup approximates the medication reductions expected in eyes undergoing surgery for medication reduction. Means are reported ± standard error (SE). Safety analysis consisted of the incidence of intraoperative and postoperative adverse events. As the study endpoints are descriptive rather than designed to test a specific hypothesis, formal power and sample size calculations were not performed.

Results

A total of 53 eyes of 42 subjects were included in this analysis. Examining the distribution of data from eyes across the sites: four sites contributed data from 1 eye each, one site contributed data from 3 eyes, one site contributed data from 6 eyes, two sites contributed data from 7 eyes each, one site contributed data from 10 eyes, and one site contributed data from 15 eyes. Baseline demographic and glaucoma status are given in Table 1. The majority of subjects were Caucasian, female, and had mild or moderate primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG).

Table 1.

Patient demographic and baseline glaucoma status

| n = 42 patients | |

| Age, years (mean ± SE) | 71.4 ± 1.6 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 23 (54.8) |

| Male | 19 (45.2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 32 (76.2) |

| Black | 7 (16.7) |

| Hispanic | 3 (7.1) |

| n = 53 eyes | |

| Glaucoma type, n (%) | |

| Primary open-angle | 49 (92.5) |

| Pigmentary | 1 (1.9) |

| Normal tension | 1 (1.9) |

| Exfoliation | 1 (1.9) |

| Angle closure | 1 (1.9) |

| Severity, n (%) | |

| Mild | 13 (24.5) |

| Moderate | 31 (58.5) |

| Severe | 9 (17.0) |

| Study eye, n (%) | |

| Right eye | 28 (52.8) |

| Left eye | 25 (47.2) |

| Pseudophakic eye, n (%) | |

| Yes | 32 (60.4) |

| No | 21 (39.6) |

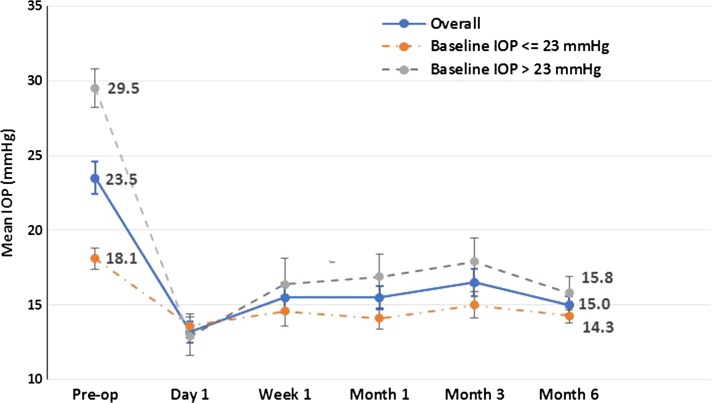

Mean IOP at baseline was 23.5 ± 1.1 mmHg in study eyes and from day 1 through 6 months of postoperative follow-up ranged from 13.2 ± 0.7 to 16.5 ± 0.9 mmHg, representing reductions of 7.0–10.3 mmHg (29.8–43.8%; p < 0.001 at each time point versus baseline) (Table 2; Fig. 1). Reductions in IOP were evident as soon as day 1 postoperatively and were maintained throughout follow-up. At month 6, 88.7% (47/53) of patients had achieved a target IOP ≤ 18 mmHg and 69.8% (37/53) had achieved a ≥ 20% IOP reduction from baseline. At the time of surgery, study eyes required a mean of 2.5 ± 0.2 IOP-lowering medications. At the 6 month visit, a mean of 1.5 ± 0.2 IOP-lowering medications were being used, representing a 1.0 (40.0%) medication reduction from preoperative baseline (Table 3; p < 0.05). By month 6, 67.9% (36/53) of eyes were able to discontinue the use of one or more IOP-lowering medications.

Table 2.

Mean IOP over time: all eyes and low- and high-IOP subgroups

| All eyes (n = 53) | Baseline IOP ≤ 23 mmHg (n = 28) | Baseline IOP > 23 mmHg (n = 25) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean IOP (mmHg) ± SEa | Mean difference (mmHg) | IOP change (%) | Mean IOP (mmHg) ± SE | Mean difference (mmHg) | IOP change (%) | Mean IOP (mmHg) ± SE | Mean difference (mmHg) | IOP change (%) | |

| Baseline (n = 53) | 23.5 (1.1) | – | – | 18.1 (0.7) | – | – | 29.5 (1.3) | – | – |

| Day 1 (n = 53) | 13.2 (0.7) | − 10.3 | − 43.8 | 13.6 (0.8) | − 4.5 | − 24.9 | 12.9 (1.3) | − 16.6 | − 56.3 |

| Week 1 (n = 51) | 15.5 (1.0) | − 8.0 | − 34.0 | 14.6 (1.0) | − 3.5 | − 19.3 | 16.4 (1.7) | − 13.1 | − 44.4 |

| Month 1 (n = 52) | 15.5 (0.8) | − 8.0 | − 34.0 | 14.1 (0.7) | − 4.0 | − 22.1 | 16.9 (1.5) | − 12.6 | − 42.7 |

| Month 3 (n = 43) | 16.5 (0.9) | − 7.0 | − 29.8 | 15.0 (0.9) | − 3.1 | − 17.1 | 17.9 (1.6) | − 11.6 | − 39.3 |

| Month 6 (n = 53) | 15.0 (0.6) | − 8.5 | − 36.2 | 14.3 (0.5) | − 3.8 | − 21.0 | 15.8 (1.1) | − 13.7 | − 46.4 |

aReported are least squares means and associated standard errors from a mixed model for repeated measure analysis. Per Bonferroni pairwise comparison, the difference from baseline in mean IOP is statistically significant at each follow-up visit (p < 0.001)

Fig. 1.

Mean IOP over time (with standard error bars) for patients with medically uncontrolled glaucoma undergoing goniotomy using the Kahook Dual Blade

Table 3.

Mean medications over time: all eyes and low- and high-IOP subgroups

| All eyes (n = 53) | Baseline IOP ≤ 23 mmHg (n = 28) | Baseline IOP > 23 mmHg (n = 25) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean medication (n) ± SEa | Mean difference (n) | Medication change (%) | Mean medication (n) ± SE | Mean difference (n) | Medication change (%) | Mean medication (n) ± SE | Mean difference (n) | Medication change (%) | |

| Baseline (n = 53) | 2.5 (0.2) | – | – | 2.5 (0.2) | 2.6 (0.3) | ||||

| Day 1 (n = 53) | 1.7 (0.2) | − 0.8 | − 32.0 | 1.6 (0.3) | − 0.9 | − 36.0 | 1.9 (0.3) | − 0.7 | − 26.9 |

| Week 1 (n = 51) | 1.8 (0.2) | − 0.7 | − 28.0 | 1.7 (0.3) | − 0.8 | − 32.0 | 1.9 (0.3) | − 0.7 | − 26.9 |

| Month 1 (n = 52) | 1.8 (0.2) | − 0.7 | − 28.0 | 1.7 (0.3) | − 0.8 | − 32.0 | 2.0 (0.3) | − 0.6 | − 23.1 |

| Month 3 (n = 43) | 1.5 (0.2) | − 1.0 | − 40.0 | 1.4 (0.3) | − 1.1 | − 44.0 | 1.5 (0.3) | − 1.1 | − 42.3 |

| Month 6 (n = 53) | 1.5 (0.2) | − 1.0 | − 40.0 | 1.6 (0.3) | − 0.9 | − 36.0 | 1.3 (0.3) | − 1.3 | − 50.0 |

aReported are least squares means and associated standard errors from a mixed model for repeated measure analysis. Per Bonferroni pairwise comparison, the difference from baseline in mean medications is statistically significant at each follow-up visit (p < 0.05) except for month 1 (p = 0.100)

To better assess subject-specific goals, the efficacy analysis was repeated in two subgroups: those with baseline IOP ≤ 23 mmHg (the median IOP of the full group), and those with baseline IOP > 23 mmHg (Tables 2, 3). In the lower-IOP group, the primary goal of surgery is assumed to be medication reduction. In this group, medications were reduced by a mean of 0.8–1.1 medications across time points, with a mean medication reduction of 0.9 medications at month 6, at which time 64% of subjects had reduced their medication burden by one or more medications. This was achieved with no compromise of IOP control, as mean IOP was in fact decreased by 3.1–4.5 mmHg across time points (− 3.8 mmHg at month 6) and 53.6% of these eyes achieved at least a 20% IOP reduction at month 6. In the higher-IOP group, where IOP reduction was likely the primary goal of surgery, mean IOP reductions ranged from 12.9 to 17.9 mmHg (39.3–56.3%), with mean IOP at month 6 being reduced by 13.7 mmHg (46.4%) and 88% of subjects achieving a minimum IOP reduction of 20%. These IOP reductions were accompanied by reductions in medications ranging from 0.6 to 1.3 medications, with subjects using a mean of 1.3 fewer medications at month 6 and 72% reducing their medication regimen by at least one medication.

Goniotomy using the KDB was generally regarded as safe and well tolerated. The only intraoperative complication reported was a single case of a localized tear in Descemet’s membrane, which did not require treatment or further intervention. Additionally, blood reflux was an intraoperative observation in eight eyes, with these being noted as microhyphemas in six of the eight eyes (75%). In seven eyes, this was resolved before the week 1 visit and by 1 month in one eye. Overall, seven adverse events were reported for the duration of follow-up. Three cases of IOP elevation were noted. In one case, an IOP rise of 5 mmHg was noted on postoperative day 1 and treated successfully with oral acetazolamide administered short-term. Two others appeared at month 3, were associated with surgical failure, and resulted in subsequent glaucoma surgery. The remaining adverse events were mild to moderate and resolved spontaneously or became clinically insignificant. The incidence of adverse events is given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Incidence of adverse events through 6 months of follow-up

| Adverse event | Incidence, n (%) |

|---|---|

| IOP spikes | 3 (5.7%) |

| Descemet’s membrane tear | 2 (3.8) |

| Corneal edema | 1 (1.9%) |

| Posterior vitreous detachment | 1 (1.9%) |

Discussion

This study demonstrates that goniotomy with the KDB as a stand-alone procedure provides significant reduction in both IOP and dependence on IOP-lowering medications in eyes with glaucoma. The IOP reductions provided by goniotomy with the KDB are consistent with recommendations for initial management of early and moderate glaucoma. On the basis of findings from major clinical trials [7–10], the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Preferred Practice Pattern for Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma recommends an initial IOP reduction of 25% for many patients with POAG [11]. On a similar basis, the European Glaucoma Society recommends an initial 20–30% IOP reduction for mild to moderate POAG [12]. Further, an incremental IOP reduction of 20% in eyes progressing at current IOP reduces the risk of future visual field loss [13]. Mean IOP reduction of 8.5 mmHg (36.2%) and mean medication reduction of 1.0 medications (40.0%) were seen at the 6-month postoperative visit, making this form of IOP lowering a viable option for eyes with glaucoma independent of concomitant cataract extraction.

The IOP reductions seen in this study are consistent with a prior study of stand-alone goniotomy with the KDB in eyes with severe and refractory glaucoma, in which mean IOP reductions of 24% were observed, medication reduction was 36.6%, and nearly 60% of eyes achieved a minimum 20% IOP reduction [14]. These results also compare favorably with other blebless, stand-alone, ab interno procedures. The Trabectome procedure lowered IOP by 33% at 6 months in its pivotal study [15]. In a non-randomized case series, the CyPass supraciliary microstent device lowered mean IOP by 29.4% at 6 months, 34.7% at 12 months, and by 31.4% at 24 months, with medication use reduced by 28.6% at 2 years; adverse events included cataract progression (12%), IOP spikes (11%), and hyphema (6%) [16, 17]. The CyPass device has recently been voluntarily recalled from the global marketplace because of safety concerns related to 5-year corneal endothelial cell loss [18]. A retrospective analysis of iStent implantation in pseudophakic eyes found mean IOP reductions of 19% and medication reductions of 13% at 12 months, although this device is not approved for stand-alone implantation in the USA [19]. Other angle-based procedures have been reported in combination with cataract surgery, but their results are not comparable to this stand-alone study in which all observed IOP and medication reductions are directly attributable to the procedure itself and not to the known effects of cataract surgery on IOP and medication reduction [20].

Goniotomy with the KDB addresses the primary cause of elevated IOP and removes the obstruction to aqueous outflow at the level of the diseased TM, thus re-establishing the normal flow of aqueous into Schlemm’s canal and the distal outflow pathway. This is accomplished without the formation of a bleb, thus avoiding the well-documented complications associated with blebs [5]. This procedure also avoids the implantation of a permanent device, which in turn eliminates the risks of erosion or migration. Also, by excising a full-width strip of meshwork, the risk of closure due to reapproximation of leaflet edges (as can occur with incisional goniotomy) may be minimized. In this study, no sight-threatening complications were observed. The most common observation in the trial of blood reflux was not unexpected. As Schlemm’s canal is unroofed, it is anticipated that some degree of blood reflux will initially be observed with the direct exposure of collector channels to the anterior chamber.

In this study, subjects underwent surgery to lower IOP, to reduce the medication burden, or both. To identify subject-specific outcomes, we have separately analyzed those with lower baseline IOP (who likely sought to achieve primarily medication reduction) and those with higher baseline IOP (who likely sought to achieve primarily IOP reduction). Eyes with lower baseline IOP in fact had meaningful reductions in both IOP [reduced by approximately 4 mmHg (~ 20%)] and medication use [reduced by 0.9 medications (~ 36%)] at month 6. Likewise, eyes with higher baseline IOP had substantially larger IOP reductions [reduced by ~ 14 mmHg (~ 45%)] and comparable medication reductions [reduced by 1.3 medications (~ 50%)] at month 6.

The retrospective nature of this study and the lack of a control group are limitations of the design. Specifically, the lack of a control group raises the possibility that observed IOP reductions are attributable in part to regression to the mean. The magnitude of IOP reductions observed in this study, however, far exceed any expected regression to the mean and likely represent therapeutic effect. As the study was retrospective, and some subjects were seen only once preoperatively (in consultation for surgery), the characterization of baseline IOP for this analysis was at a single preoperative time point, which is admittedly less robust than assessing IOP at several time points on different days. An additional limitation is the unequal enrollment across study sites, with four sites enrolling a single eye each; lacking a sound methodological justification for excluding these eyes, they were included in this analysis. The evaluation of this technique as a stand-alone procedure—rather than combined with cataract surgery—is a strength in view of most micro-incisional ab interno glaucoma implants lacking such published data. Cataract surgery alone is known to reduce both IOP and the need for IOP-lowering medications in eyes with glaucoma. In a recent meta-analysis, the mean IOP reduction seen in eyes with glaucoma 6 months after cataract surgery was 12% and the reduction in mean number of IOP-lowering medications used was 0.6 [20]. Thus, in studies of glaucoma procedures combined with cataract surgery, it is difficult to assess the relative contribution of each procedure on the final outcome.

In summary, goniotomy with the KDB effectively and safely lowers IOP and the need for IOP-lowering medications when performed as a stand-alone procedure in eyes with glaucoma. The magnitude of IOP reduction meets or exceeds the recommended targets for most patients with glaucoma. Further studies—including longer-term follow-up as well as prospective, randomized, head-to-head comparisons with other minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries—are warranted and are underway.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

New World Medical, Inc. provided funding for the study, medical writing assistance, article processing charges and the open access fee.

Editorial Assistance

We would like to thank Anthony D. Realini, MD, MPH for assisting in writing the manuscript. Dr. Realini, Hypotony Holdings, LLC, is an independent consultant to New World Medical. New World Medical provided funding for the medical writing assistance.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

John Berdahl declares that he has received lecture and consulting fees from Alcon, Allergan, Glaukos, consulting fees from Johnson & Johnson Vision, Avedro, Bausch & Lomb, Clarvista, Digisight, Envisia, New World Medical, Ocular Therapeutix, Vittamed, and Mobius, is an equity owner of Equinox, Omega Ophthalmic, Ocular Surgical Data, and Vision 5, has received consulting fees and royalties from Imprimis, and was a consultant to New World Medical for the conduct of this study. He has also received research support from New WORLD Medical in the past. Mayo Clinic does not endorse specific products or services included in this article. Mark J. Gallardo declares that he has received consulting and speaker fees from Ellex, Alcon, Glaukos, and Ivantis, speaker fees from Allergan, and research support from Ellex, Alcon, Glaukos, Ivantis, New World Medical (for the conduct of this study), and Sight Science. Mohammed K. ElMallah declares that he has received consulting fees and research report from New World Medical for the conduct of this study and research support from Glaukos, Ivantis, and Unity. Blake K. Williamson declares that he has received consulting fees and research support from New World Medical for the conduct of this study and consulting fees from Alcon, Allergan, Bausch + Lomb, Biotissue, Diopsys, Glaukos, Johnson & Johnson Vision, Shire, Sight Sciences, and Zeiss. Malik Y. Kahook declares he has received consulting fees from Allergan, patent royalties and consulting fees from Alcon and New World Medical, and is the inventor of the KDB device. Ahad Mahootchi declares he has received consulting and speaking fees from Bausch + Lomb, Ellex, Imprimis, Iridex, and STAAR, and research support from Bausch + Lomb and New World Medical for the conduct of this study. Leonard A. Rappaport declares he has received research support from New World Medical for this project. Daniela Diaz-Robles declares she has no disclosure to report. Gabriel S. Lazcano-Gomez declares that he has received consulting fees from New World Medical, was a consultant to New World Medical for the conduct of this study, and has received research support from New World Medical in the past. Syril K. Dorairaj declares that he has received consulting fees from New World Medical, was a consultant to New World Medical for the conduct of this study, and has received research support from New World Medical in the past.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.7145831.

References

- 1.Johnson M. What controls aqueous humour outflow resistance? Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:545–557. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cairns JE. Trabeculectomy. Preliminary report of a new method. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968;66:673–679. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(68)91288-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhry HA, Dueker DK, Simmons RJ, Bellows AR, Grant WM. Scanning electron microscopy of trabeculectomy specimens in open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;88:78–92. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(79)90759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castelbuono AC, Green WR. Histopathologic features of trabeculectomy surgery. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2003;101:119–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zahid S, Musch DC, Niziol LM, Lichter PR, Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study Group Risk of endophthalmitis and other long-term complications of trabeculectomy in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study (CIGTS) Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155:674–680, 80 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenwood MD, Seibold LK, Radcliffe N, et al. Goniotomy with the Kahook Dual Blade: short term results of an interventional case series. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2017;43:1197–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2017.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heijl A, Leske MC, Bengtsson B, Hyman L, Bengtsson B, Hussein M. Reduction of intraocular pressure and glaucoma progression: results from the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1268–1279. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.10.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.AGIS Study Group The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 4. Comparison of treatment outcomes within race. Seven-year results. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1146–1164. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)97013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lichter PR, Musch DC, Gillespie BW, et al. Interim clinical outcomes in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study comparing initial treatment randomized to medications or surgery. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1943–1953. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(01)00873-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group Comparison of glaucomatous progression between untreated patients with normal-tension glaucoma and patients with therapeutically reduced intraocular pressures. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:487–497. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(98)00223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Academy of Ophthalmology . Primary open-angle glaucoma: preferred practice pattern. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Glaucoma Society . Terminology and guidelines for glaucoma. 4. Savona: PubliComm; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chauhan BC, Mikelberg FS, Artes PH, et al. Canadian Glaucoma Study: 3. Impact of risk factors and intraocular pressure reduction on the rates of visual field change. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1249–1255. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salinas L, Chaudhary A, Berdahl JP, et al. Goniotomy using the Kahook Dual Blade in severe and refractory glaucoma: six month outcomes. J Glaucoma. 2018 doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minckler D, Baerveldt G, Ramirez MA, et al. Clinical results with the Trabectome, a novel surgical device for treatment of open-angle glaucoma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2006;104:40–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Feijoo J, Hoh H, Uzunov R, Dickerson JE., Jr Supraciliary microstent in refractory open-angle glaucoma: two-year outcomes from the DUETTE Trial. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2018 doi: 10.1089/jop.2018.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Feijoo J, Rau M, Grisanti S, et al. Supraciliary micro-stent implantation for open-angle glaucoma failing topical therapy: 1-year results of a multicenter study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(1075–81):e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alcon announces voluntary global market withdrawal of CyPass Micro-Stent for surgical glaucoma. https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/alcon-announces-voluntary-global-market-withdrawal-cypass-micro-stent-surgical-glaucoma. Accessed Aug 29, 2018.

- 19.Ferguson TJ, Berdahl JP, Schweitzer JA, Sudhagoni R. Evaluation of a trabecular micro-bypass stent in pseudophakic patients with open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2016;25:896–900. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong JJ, Wasiuta T, Kiatos E, Malvankar-Mehta M, Hutnik CM. The effects of phacoemulsification on intraocular pressure and topical medication use in patients with glaucoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 3-year data. J Glaucoma. 2017;26:511–522. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.