Abstract

Aim: The optimal risk assessment model (RAM) to stratify the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in medical inpatients is not known. We examined and compared how well the Padua Prediction Score (PPS) and the Caprini RAM stratify VTE risk in medical inpatients.

Methods: We undertook a retrospective case-control study among medical inpatients admitted to a large general hospital in China during a 4-year period. In total, 902 cases were confirmed to have VTE during hospitalization and 902 controls were selected randomly to match cases by medical service.

Results: The VTE risk increased significantly with an increase of the cumulative PPS or Caprini RAM score. A PPS and Caprini RAM “high risk” classification was, respectively, associated with a 5.01-fold and 4.10-fold increased VTE risk. However, the Caprini RAM could identify 84.3% of the VTE cases to receive prophylaxis according to American College of Chest Physicians guidelines, whereas the PPS could only identify 49.1% of the VTE cases. In the medical inpatients studied, five risk factors seen more frequently in VTE cases than in controls in the Caprini RAM were not included in the PPS. The Caprini RAM risk levels were linked almost perfectly to in-hospital and 6-month mortality.

Conclusions: Both the PPS and Caprini RAM can be used to stratify the VTE risk in medical inpatients effectively, but the Caprini RAM may be considered as the first choice in a general hospital because of its incorporation of comprehensive risk factors, higher sensitivity to identify patients who may benefit from prophylaxis, and potential for prediction of mortality.

Keywords: Venous thromboembolism, Caprini risk assessment model, Padua Prediction Score, Medical inpatients, Mortality

See editorial vol. 25: 1087–1088

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep venous thrombosis (DVT), is a major and potentially life-threatening complication among medical inpatients. It has been reported that 50%–75% of cases of VTE in hospitalized patients occur in those being treated for medical conditions, and that the incidence of fatal PE is higher in medical patients compared with surgical patients1–4). Evidence clearly demonstrates that prophylaxis significantly reduces the incidence of VTE5–7), and most guidelines recommend the use of prophylaxis for medical inpatients at an increased risk of developing VTE8, 9). However, the administration of VTE prophylaxis in these patients continues to be largely underused2, 10–12). Accurate and individual assessment of VTE risk is therefore critical for improving this situation13, 14).

Several risk assessment models (RAMs) for VTE have been proposed to evaluate the risk of VTE in medical inpatients15–21), but consensus about which one is the best is lacking. The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis 9th edition (ACCP-9) adopted the Padua Prediction Score (PPS), which was based only on a single cohort study carried out in Italy15), to estimate the VTE risk for medical inpatients9). Questions regarding the representativeness of the included patients in the study and the failure to incorporate some important risk factors (e.g., family history of VTE) were raised subsequently by some researchers22). In addition, studies aimed at validation of this RAM in medical inpatients in other centers are rare.

The Caprini RAM was developed originally for both surgical and medical patients16). Although there have been robust evidences to show its validity in surgical patients23–26) and the ACCP-9 recommended it to evaluate the VTE risk in non-orthopedic surgical patients27), the currently available validation studies of the Caprini RAM in medical inpatients have controversial conclusions28–31). Moreover, the current strategy of risk assessment among inpatients is to use different RAMs based on the departments they are currently hospitalized in, which is not convenient (and sometimes even time-consuming) in a general hospital in which patients are moved to different departments relatively frequently. The process of risk assessment for VTE could be simplified greatly if a universal RAM was employed. The primary aim of the present study was to evaluate and compare the validities of the PPS and Caprini RAM in stratifying the risk of VTE in medical inpatients from a general hospital through a large retrospective study.

The association of these RAMs with the prognosis of VTE patients is also an interesting topic. Vardi and colleagues found PPS to be closely associated with mortality and to possibly function as a general index for comorbidity and disease severity32). Previously, our research team found the Caprini RAM to be potentially effective in predicting the risk of VTE recurrence33). It would be quite convenient and useful to obtain information about the VTE risk and prognosis of a patient through a one-time assessment with a validated RAM. In the present study, we also sought to gain insights into the association of those RAMs with mortality in the hospital and after discharge.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the West China Hospital of Sichuan University (Sichuan, China; a 4300-bed general teaching hospital). Written informed consent was obtained from all VTE cases in the follow-up study.

We undertook a case-control study among medical inpatients admitted to the West China Hospital during a 4-year period. Complementarily, a prospective 6-month follow-up study was undertaken among the VTE cases after their discharge from the hospital.

We identified all cases of VTE which occurred in all the medical departments of the hospital between January 2013 and December 2016. The approaches employed to include VTE cases have been reported31, 33). VTE patients could be enrolled via the VTE Registration Center or the Information Center of the hospital. The VTE Registration Center was founded in 2009 by the hospital to include VTE patients for study. We also searched information from the hospital's Information Center to include VTE patients who may be missed by the VTE Registration Center. Hospital ICD (International Classification of Diseases)-10 codes for VTE (I26, I80, I82) were used to select cases for review.

Inclusion criteria were confirmed VTE (DVT and/or PE), age ≥ 18 years, and hospitalization duration ≥ 2 days. Exclusion criteria were VTE or presumed VTE upon hospital admission, thrombosis in a location other than the deep veins of the legs or arms, or a coding error. DVT was validated based on positive- compression ultrasonography and/or contrast venography. PE was validated based on a positive pulmonary angiogram, spiral computed tomography, high probability ventilation/perfusion scanning, or autopsy.

Controls were selected randomly from medical inpatients (age ≥ 18 years) admitted into the same departments during the same period (same month) as cases, without an ICD-10 code for thrombosis at discharge. Exclusion criteria for controls were a coding error (occurrence of DVT and/or PE), hospitalization duration < 2 days, or data unavailability. Controls were frequency-matched to cases at a ratio of 1:1.

RAM

Each recruited patient was assessed retrospectively for VTE risk by the PPS and Caprini RAM based on the information available upon his/her admission. In the PPS, the risk profile for VTE is calculated using 11 common risk factors for VTE. Each risk factor is weighted according to a point scale. A high risk of VTE is defined as a cumulative score ≥ 4 and a low risk as one of < 49, 15). The Caprini RAM is also a weighted risk model that produces an aggregate risk score based on the presence or absence of 39 individual risk factors. When the ACCP adopted the Caprini RAM in 2012, the risk factors and weighted scores from the original 2005 version (Caprini-2005)16) were maintained, whereas the definition of the four risk levels and corresponding criteria for each risk level were modified. We evaluated the modified version of the Caprini RAM by ACCP in the present study (which is currently the most widely used version of the Caprini RAM worldwide). According to this version, patients are classified as follows: “very low risk” (score 0), “low risk” (1–2), “moderate risk” (3–4), or “high risk” (≥ 5)27). The risk factors identified by both RAMs, the points assigned, and the criteria of the risk levels are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Supplemental Table 1. Risk factors identified and definition of risk levels in the Padua Prediction Score and Caprini RAM.

| RAM | Risk Factors in the RAMs | Definition of risk levels |

|---|---|---|

| Padua Prediction Score | Score 3: Active cancer; Previous VTE (with the exclusion of superficial vein thrombosis); Reduced mobility; Already known thrombophilic condition | Low risk: < 4 High risk: ≥ 4 |

| Score 2: Recent (≤ 1 month) trauma and/or surgery | ||

| Score 1: Elderly age (≥ 70 years); Heart and/or respiratory failure; Acute myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke; Acute infection and/or rheumatologic disorder; Obesity (BMI ≥ 30); Ongoing hormonal treatment | ||

| Caprini RAM | Score 5: Stroke; Multiple trauma; Elective major lower extremity arthroplasty; Hip, pelvis or leg fracture; Acute spinal cord injury (paralysis) | According to 2005 version, four classifications: Low risk: 0–1, |

| Score 3: Age (≥ 75); History of VTE; Positive Factor V Leiden; Positive prothrombin G20210A; Elevated serum homocysteine; Positive Lupus anticoagulant; Other congenital or acquired thrombophilia; Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT); Family history of VTE; Elevated anticardiolipin antibodies | Moderate risk: 2, High risk: 3–4, Highest risk: ≥ 5; |

|

| Score 2: Age (61–74); Central venous access; Arthroscopic surgery; Major surgery; Malignancy; Laparoscopic procedure > 45 min; Patient confined to bed; Immobilizing plaster cast | According to ACCP modification, four classifications: Very low risk: 0, Low risk: 1–2, |

|

| Score 1: Age (41–60); Acute myocardial infarction; Heart failure; Varicose veins; Obesity (BMI > 25); Inflammatory bowel disease; Sepsis; COPD or abnormal pulmonary function; Severe lung disease; Oral contraceptives or HRT; Pregnancy or postpartum; History of unexpected stillborn infant, recurrent spontaneous abortion (≥ 3), premature birth with toxemia or growth-restricted infant; Medical patient currently at bed rest; Minor surgery planned; History of prior major surgery; Swollen legs | Moderate risk: 3–4, High risk: ≥ 5; |

RAM = risk assessment model; BMI = body mass index; HRT = hormone replacement therapy; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; VTE = venous thromboembolism; ACCP = American College of Chest Physicians

Data Collection

Clinical data were collected using standardized case report forms by abstractors of medical records who received in-depth training to ensure data reliability. Detailed information on the demographics, medical history, physical examination, laboratory results, and medication data were collected for all patients. Risk factors used to calculate the PPS and Caprini risk scores were captured. “VTE prophylaxis” was defined as administration of any mechanical (intermittent pneumatic compression devices or sole vein pump) or pharmacological (unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, fondaparinux sodium, etc.) prophylaxis before the diagnosis of VTE and for prevention purposes only (not for treatment). In addition, we conducted 6-month follow-ups for the VTE cases after hospital discharge by monthly phone calls combined with outpatient visits and hospitalization (if necessary).

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables with a normal distribution are described as mean values with standard deviations, and group comparisons were performed using the Student's t-test. Continuous variables with a skewed distribution are presented as median values with interquartile ranges, and group comparisons were undertaken using non-parametric tests. Discrete variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, and group comparisons were carried out using the chisquared test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were used to validate risk factors adopted by the PPS and Caprini RAM in the study population, and to calculate the odds ratio (OR) for VTE of the different risk scores and levels by the two RAMs. Also, 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) are reported.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted referring to the sensitivity and specificity of the two RAMs, and the areas under the curve (AUCs) and 95% CIs were calculated.

The time-courses for the occurrence of death after hospital discharge in VTE patients with different risk levels by the PPS and Caprini RAM were depicted as Kaplan–Meier curves. Group comparisons were made using the log-rank test.

All reported P-values are two-tailed. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS v20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the VTE Cases and Control Subjects

A total of 1395 medical inpatients were identified as having VTE at first. Then, 493 patients were excluded due to VTE/presumed VTE upon hospital admission (303 cases), age < 18 years (16), < 2-day hospital stay (116), thrombosis in a location other than the deep veins of the legs or arms (53), or a coding error (5). Finally, 902 patients were confirmed as having VTE during hospitalization and were included as cases in our study. These VTE cases were admitted into 18 medical departments (Supplemental Table 2). Among the 902 VTE cases, 285 (31.6%) had DVT only, 386 (42.8%) had PE only, and 231 (25.6%) were diagnosed with DVT and PE. A total of 902 control patients without VTE were selected randomly and matched to cases by the admitting departments (Supplemental Table 2).

Supplemental Table 2. The distribution of case and control patients by medical departments.

| Medical department | Cases (%) (n = 902) | Controls (%) (n = 902) |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory medicine | 344 (38.14) | 344 (38.14) |

| Cardiology | 80 (8.87) | 80 (8.87) |

| Geriatrics | 77 (8.54) | 77 (8.54) |

| Oncology | 73 (8.09) | 73 (8.09) |

| General internal medicine | 50 (5.54) | 50 (5.54) |

| Neurology | 45 (4.99) | 45 (4.99) |

| Nephrology | 42 (4.66) | 42 (4.66) |

| Infectious diseases | 35 (3.88) | 35 (3.88) |

| Hematology | 35 (3.88) | 35 (3.88) |

| Gastroenterology | 33 (3.66) | 33 (3.66) |

| Integrated TCM and western medicine | 27 (2.99) | 27 (2.99) |

| ICU | 26 (2.88) | 26 (2.88) |

| Rheumatology | 16 (1.77) | 16 (1.77) |

| Tuberculosis | 5 (0.55) | 5 (0.55) |

| Rehabilitation | 4 (0.44) | 4 (0.44) |

| Endocrinology | 4 (0.44) | 4 (0.44) |

| Pain management | 3 (0.33) | 3 (0.33) |

| Psychiatry department | 3 (0.33) | 3 (0.33) |

TCM = traditional Chinese medicine; ICU = intensive care unit

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the VTE cases and control subjects. There were no significant differences between the cases and controls with respect to sex, hemoglobin level, hematocrit, and platelet count upon hospital admission (all P > 0.05). However, the VTE cases were older and had a higher body mass index (BMI), higher white blood count, and D-dimer level upon hospital admission compared with the control subjects (all P < 0.05). As expected, VTE cases were 3.92-fold more likely to die during hospitalization than controls (95% CI 2.57–5.99; P < 0.001), and had a longer duration of hospital stay (14 vs. 11 days, P < 0.001). The proportion of medical inpatients receiving prophylaxis during hospitalization was surprisingly low, with only 4.1% in the cases and 6.1% in the control subjects (P = 0.054).

Table 1. Characteristics of VTE cases and controls.

| Characteristic | Cases | Controls | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 902) | (n = 902) | ||

| Male gender | 540 (59.9) | 528 (58.5) | 0.565 |

| Age (years) | 60.38 ± 17.23 | 57.35 ± 17.16 | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2)a | 22.98 ± 3.83 | 22.31 ± 3.66 | 0.004 |

| BMI > 25 | 152 (26.1) | 83 (18.5) | 0.04 |

| BMI > 30 | 32 (5.5) | 16 (3.6) | 0.145 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 123.08 ± 27.04 | 123.29 ± 24.11 | 0.866 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 37.78 ± 7.80 | 37.91 ± 6.93 | 0.710 |

| WBC (× 103 mm−3) | 8.99 ± 8.55 | 7.15 ± 4.39 | < 0.001 |

| WBC > 10 × 103 mm−3 | 271 (30.0) | 128 (14.2) | < 0.001 |

| Platelet count (× 103 mm−3) | 192.13 ± 96.05 | 196.53 ± 99.59 | 0.352 |

| D-Dimer on admission (mg/L FEU)b | 8.98 ± 32.39 | 2.50 ± 4.74 | < 0.001 |

| Mortality during hospitalization | 104 (11.5) | 29 (3.2) | < 0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 14 (9–22) | 11 (7–16) | < 0.001 |

| Patients receiving prophylaxis | 37 (4.1) | 55 (6.1) | 0.054 |

Data are presented as number of patients (%), mean ± SD, median (interquartile range)

VTE = venous thromboembolism, BMI = body mass index; WBC = white blood count

Available in 583 cases, 449 controls.

Available in 370 cases, 242 controls.

Risk Stratification by the Score of the PPS and Caprini RAM

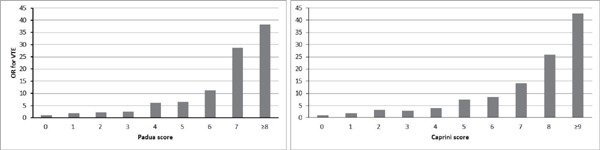

In both RAMs, the mean or median cumulative risk score in the cases was significantly higher than that in the controls (median score 3 [1–5] vs. 1 [0–3], P < 0.001 for the PPS; mean score 5.24 ± 2.90 vs. 3.28 ± 1.84, P < 0.001 for the Caprini RAM) (Table 2). The risk of VTE increased almost linearly with the increase of cumulative PPS after adjustment for VTE prophylaxis use. The same trend was observed with the Caprini RAM score (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Table 2. Risk stratification by Padua and Caprini cumulative risk scores.

| Cumulative risk score | Cases | Controls | P value | OR for VTE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 902) | (n = 902) | (95% CI)a | ||

| Padua Prediction Score | ||||

| 0 | 98 (10.9) | 281 (31.2) | < 0.001 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 1 | 153 (17.0) | 230 (25.5) | < 0.001 | 1.92 (1.41–2.61) |

| 2 | 73 (8.1) | 96 (10.6) | < 0.001 | 2.19 (1.49–3.20) |

| 3 | 135 (15.0) | 149 (16.5) | < 0.001 | 2.59 (1.87–3.59) |

| 4 | 170 (18.8) | 80 (8.9) | < 0.001 | 6.09 (4.28–8.66) |

| 5 | 80 (8.9) | 36 (4.0) | < 0.001 | 6.43 (4.08–10.16) |

| 6 | 76 (8.4) | 20 (2.2) | < 0.001 | 11.22 (6.50–19.36) |

| 7 | 50 (5.5) | 5 (0.6) | < 0.001 | 28.66 (11.11–73.98) |

| ≥ 8 | 67 (7.4) | 5 (0.6) | < 0.001 | 38.23 (14.97–97.63) |

| Average cumulative risk score, | 3 (1–5) | 1 (0–3) | < 0.001 | – |

| median (interquartile range) | ||||

| Caprini risk assessment model | ||||

| 0 | 9 (1.0) | 45 (5.0) | < 0.001 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 1 | 42 (4.7) | 117 (13.0) | 0.150 | 1.80 (0.81–3.99) |

| 2 | 91 (10.1) | 143 (15.9) | 0.003 | 3.21 (1.50–6.88) |

| 3 | 119 (13.2) | 207 (22.9) | 0.005 | 2.90 (1.37–6.15) |

| 4 | 124 (13.7) | 161 (17.8) | < 0.001 | 3.91 (1.84–8.82) |

| 5 | 163 (18.1) | 110 (12.2) | < 0.001 | 7.39 (3.47–15.74) |

| 6 | 110 (12.2) | 66 (7.3) | < 0.001 | 8.49 (3.89–18.49) |

| 7 | 78 (8.6) | 29 (3.2) | < 0.001 | 14.08 (6.11–32.46) |

| 8 | 47 (5.2) | 10 (1.1) | < 0.001 | 25.86 (9.56–69.99) |

| ≥ 9 | 119 (13.2) | 14 (1.6) | < 0.001 | 42.71 (17.27–105.63) |

| Average cumulative risk score, | < 0.001 | – | ||

| mean ± SD | 5.24 ± 2.90 | 3.28 ± 1.84 | ||

OR = odds ratio, VTE = venous thromboembolism, CI = confidence interval, SD = standard deviation

Adjusted for use of VTE prophylaxis

Fig. 1.

The risks (ORs) of VTE according to the score of the Padua and Caprini RAMs

(VTE = venous thromboembolism; OR=odds ratio; RAM= risk assessment model)

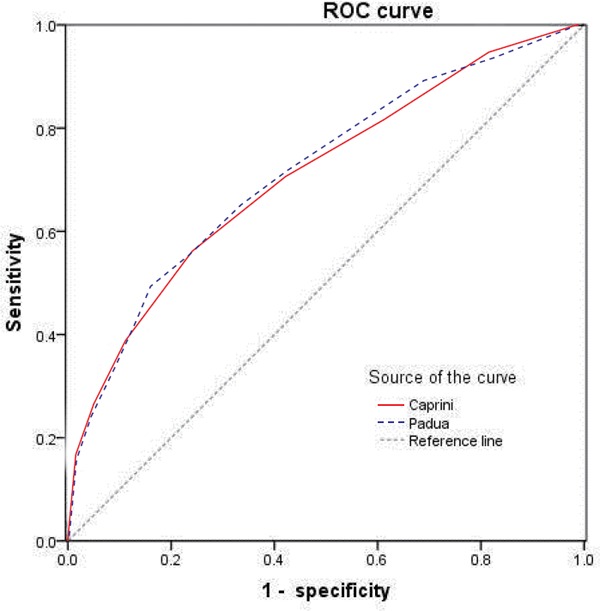

Analyses of ROC curves showed that the AUC and 95% CI of the Caprini RAM score were similarly to the PPS (AUC: 0.709 ± 0.012 vs. 0.716 ± 0.012; 95% CI 0.686–0.733 vs. 0.693–0740, P = 0.680) (Fig. 2). Both showed satisfactory accuracy for predicting in-hospital VTE in medical patients, with the best cutoff value being 4 for the PPS and 5 for the Caprini RAM score according to the ROC (which happened to be the cutoff value chosen by the PPS and Caprini RAM for high risk).

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the Caprini and Padua scores

Comparison of the PPS and Caprini RAM among Medical Inpatients

Table 3 compares the Caprini RAM score with the PPS among medical inpatients and lists the recommendations for VTE prophylaxis based on ACCP guidelines for each condition. After adjustment for use of VTE prophylaxis, a classification of “high risk” according to these two RAMs was associated with similar ORs for VTE: 4.10 (95% CI 3.34–45.00) for the Caprini RAM vs. 5.01 (95% CI 4.03–6.25) for the PPS. Based on information upon hospital admission, the Caprini RAM could be used to: identify 84.3% of VTE cases as moderate-to-high risk who should receive pharmacologic prophylaxis or mechanical prophylaxis based on the ACCP guideline; 57.1% of VTE cases as “high risk” who should receive pharmacologic prophylaxis. The PPS could be used to identify 49.1% of VTE cases as “high risk” for whom pharmacologic prophylaxis was recommended.

Table 3. Comparison of the Caprini RAM and the Padua Prediction Score among medical inpatients, with recommendations for VTE prophylaxis.

| RAMs | Caprini RAM |

The Padua Prediction Score |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with moderate to high risk (≥ 3 score), % | Patients with high risk (≥ 5 score), % | Patients with high risk (≥ 4 score), % | |

| Cases (n = 902) | 84.30% | 57.10% | 49.10% |

| Controls (n = 902) | 66.20% | 24.60% | 16.20% |

| P value | < 0.001† | < 0.001‡ | < 0.001† |

| Adjusted OR for VTE (95%CI)a | 2.75 (2.20–3.46) | 4.10 (3.34–5.00) | 5.01 (4.03–6.25) |

| Recommendations for VTE prophylaxis (if low risk of bleeding)b | Pharma.p is optional or obligatory; mech.p is optional | Pharma.p is obligatory (only or with mech.p) | Pharma.p is obligatory (only) |

RAM = risk assessment model, OR = odds ratio, VTE=venous thromboembolism, CI = confidence interval, Pharm.p=pharmacologic prophylaxis, mech.p = mechanical prophylaxis

Adjusted for use of VTE prophylaxis

Based on the ACCP-9, American College of Chest Physicians guideline, ninth edition.

Validation of Risk Factors Adopted by the PPS and Caprini RAM in the Study Population

Of the 11 risk factors listed in the PPS, nine factors (previous VTE; reduced mobility; known thrombophilic condition; recent [≤ 1 month] trauma and/or surgery; elderly age [≥ 70 years]; heart and/or respiratory failure; acute myocardial infarction and/or ischemic stroke; acute infection and/or rheumatologic disorder; and obesity [BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2]) were associated significantly with an increased risk of in-hospital VTE in the univariate analysis, whereas active cancer (P = 0.808) and ongoing hormonal treatment (P = 0.133) were not. All of these significant factors were also identified as independent risk factors for VTE by the multivariate logistic regression analysis after adjustment for use of VTE prophylaxis (Table 4).

Table 4. Validation of risk factors adopted by Padua Prediction Score in the study population, with adjusted OR of VTE.

| Risk factor in Padua Prediction Score | Relative | Cases | Controls | Crude | Adjusted ORa | Adjusteda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Score | (n = 902) | (n = 902) | P value | (95% CI) | P value | |

| Active cancerb | 3 | 164 (18.2) | 168 (18.6) | 0.808 | - | - |

| Previous VTE | 3 | 146 (16.2) | 4 (0.4) | < 0.001 | 47.89 (17.22–133.20) | < 0.001 |

| (with the exclusion of superficial vein thrombosis) | ||||||

| Reduced mobility | 3 | 373 (41.4) | 122 (13.5) | < 0.001 | 4.23 (3.29–5.43) | < 0.001 |

| Already known thrombophilic condition | 3 | 18 (2.0) | 1 (0.1) | < 0.001 | 22.44 (2.86–176.14) | 0.003 |

| Recent (≤ 1 mo) trauma and/or surgery | 2 | 56 (6.2) | 27 (3.0) | 0.001 | 1.77 (1.04–3.01) | 0.036 |

| Elderly age (≥ 70 y) | 1 | 319 (35.4) | 235 (26.1) | < 0.001 | 1.38 (1.10–1.74) | 0.006 |

| Heart and/or respiratory failure | 1 | 151 (16.7) | 83 (9.2) | < 0.001 | 1.55 (1.12–2.14) | 0.009 |

| Acute myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke | 1 | 53 (5.9) | 9 (1.0) | < 0.001 | 5.20 (2.40–11.27) | < 0.001 |

| Acute infection and/or rheumatologic disorder | 1 | 406 (45.0) | 261 (28.9) | < 0.001 | 2.06 (1.65–2.58) | < 0.001 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30)c | 1 | 32 (3.5) | 18 (2.0) | 0.045 | 2.18 (1.16–4.12) | 0.016 |

| Ongoing hormonal treatment | 1 | 10 (1.1) | 19 (2.1) | 0.133 | - | - |

| VTE prophylaxis | - | 37 (4.1) | 55 (6.1) | 0.054 | 0.42 (0.25–0.71) | 0.001 |

OR = odds ratio, VTE = venous thromboembolism, CI = confidence interval, BMI = body mass index, mo = month

Variables that had a P-value < 0.05 in univariable crude analysis were selected for inclusion in the final multivariable model and VTE prophylaxis was also included.

Cancer patients with local or distant metastases and/or in whom chemotherapy or radiotherapy had been performed in the previous 6 months

Available in 583 cases, 449 controls.

Of the 39 risk factors adopted by the Caprini RAM, 14 factors (age > 75 years; heart failure; varicose veins; obesity [BMI > 25 kg/m2]; severe lung disease; pregnancy or postpartum; history of prior major surgery [< 1 month]; swollen legs [current]; patient confined to bed [> 72 h]; history of DVT/PE; increased level of anti-cardiolipin antibodies; stroke; multiple trauma [< 1 month]; and hip, pelvis, or leg fracture [< 1 month]) were significantly associated (all P < 0.01) with an increased risk of in-hospital VTE in the univariate analysis (Table 4). Seven patients in the case group (0.8%) vs. one patient in the control group (0.1%) had a family history of VTE, but the P value was marginally different (P = 0.068). However, a multivariate analysis showed that age > 75 years, varicose veins, multiple trauma (< 1 month), and fracture of the hip, pelvis, or leg (< 1 month) may not be independent risk factors in this study population after adjustment for VTE prophylaxis (Table 5).

Table 5. Validation of risk factors adopted by Caprini RAM in the study population, with adjusted OR of VTE.

| Risk factor in Caprini RAM | Relative | Cases | Controls | Crude | Adjusted ORa | Adjusteda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Score | (n = 902) | (n = 902) | P value | (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age, 41–60 | 1 | 285 (31.6) | 315 (34.9) | 0.134 | - | - |

| Age, 61–74 | 2 | 276 (30.6) | 285 (31.6) | 0.647 | - | - |

| Age, 75+ | 3 | 210 (23.3) | 142 (15.7) | < 0.001 | 1.20 (0.90–1.60) | 0.226 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1 | 8 (0.9) | 6 (0.7) | 0.592 | - | - |

| Heart failure | 1 | 60 (6.7) | 22 (2.4) | < 0.001 | 2.07 (1.14–3.76) | 0.017 |

| Varicose veins | 1 | 33 (3.7) | 10 (1.1) | < 0.001 | 1.97 (0.84–4.63) | 0.122 |

| Obesity (BMI > 25)b | 1 | 152 (26.1) | 83 (18.5) | 0.004 | 2.00 (1.37–2.91) | < 0.001 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 1 | 3 (0.3) | 5 (0.6) | 0.723 | - | - |

| Sepsis (< 1 mo) | 1 | 16 (1.8) | 13 (1.4) | 0.574 | - | - |

| COPD or abnormal pulmonary function | 1 | 138 (15.3) | 135 (15.0) | 0.844 | - | - |

| Severe lung disease, including pneumonia (< 1 mo) | 1 | 456 (50.6) | 325 (36.0) | < 0.001 | 2.10 (1.67–2.64) | < 0.001 |

| Oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy | 1 | 12 (1.3) | 20 (2.2) | 0.154 | - | - |

| Pregnancy or postpartum (< 1 mo) | 1 | 37 (4.1) | 1 (0.1) | < 0.001 | 40.78 (5.36–310.45) | < 0.001 |

| History of unexpected stillborn infant, recurrent spontaneous abortion (≥ 3), premature birth with toxemia or growth-restricted infant | 1 | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 0.625 | - | - |

| Medical patient currently at bed rest | 1 | 96 (10.6) | 78 (8.6) | 0.151 | - | - |

| Minor surgery planned | 1 | 22(2.4) | 36(4.0) | 0.061 | - | - |

| History of prior major surgery(< 1 mo) | 1 | 37 (4.1) | 4 (0.4) | < 0.001 | 5.21 (1.61–16.86) | 0.006 |

| Swollen legs (current) | 1 | 321 (35.6) | 106 (11.8) | < 0.001 | 3.95 (3.00–5.21) | < 0.001 |

| Central venous access | 2 | 40 (4.4) | 32 (3.5) | 0.336 | - | - |

| Arthroscopic surgery | 2 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | - | - |

| Major surgery (> 45 min) | 2 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | - | - |

| Malignancy (present or previous) | 2 | 168 (18.6) | 192 (21.3) | 0.157 | - | - |

| Laparoscopic procedure > 45 min | 2 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | - | - |

| Patient confined to bed (> 72 h) | 2 | 286 (31.7) | 44 (4.9) | < 0.001 | 9.20 (6.40–13.22) | < 0.001 |

| Immobilizing plaster cast (< 1 mo) | 2 | 4 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.133 | - | - |

| History of DVT/PE | 3 | 146 (16.2) | 4 (0.4) | < 0.001 | 38.75 (13.79–108.86) | < 0.001 |

| Positive Factor V Leiden; positive prothrombin G20210A; elevated serum homocysteinec | 3 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Positive Lupus anticoagulantc | 3 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) | 3 | 4 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.133 | - | - |

| Family history of VTE | 3 | 7 (0.8) | 1 (0.1) | 0.068 | - | - |

| Elevated anticardiolipin antibodies | 3 | 18 (2.0) | 1 (0.1) | < 0.001 | 19.80 (2.45–160.27) | 0.005 |

| Stroke (< 1 mo) | 5 | 48 (5.3) | 5 (0.6) | < 0.001 | 8.71 (3.20–23.71) | < 0.001 |

| Multiple trauma (< 1 mo) | 5 | 7 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.023 | - | - |

| Elective major lower extremity arthroplasty | 5 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.317 | - | - |

| Hip, pelvis, or leg fracture (< 1 mo) | 5 | 14 (1.6) | 3 (0.3) | 0.007 | 4.42 (1.07–18.25) | 0.40 |

| Acute spinal cord injury (paralysis) (< 1 mo) | 5 | 6 (0.7) | 1 (0.1) | 0.130 | - | - |

| VTE prophylaxis | - | 37 (4.1) | 55 (6.1) | 0.054 | 0.49 (0.28–0.85) | 0.012 |

RAM = risk assessment model, OR = odds ratio, VTE = venous thromboembolism, CI = confidence interval, BMI = body mass index, mo = month

Variables that had a P-value < 0.05 in univariable crude analysis were selected for inclusion in the final multivariable model and VTE prophylaxis was also included.

Available in 583 cases, 449 controls.

These risk factors cannot be tested in the hospital.

Association of the PPS and Caprini RAM with VTE Mortality

Table 6 shows the associations of risk levels by the PPS and Caprini RAM with in-hospital and 6-month mortality in the VTE cases. Of the 902 VTE cases in the medical departments, 104 (11.5%) patients died during hospitalization. Being consistent with the PPS and Caprini RAM, the high-risk level showed a strong association with in-hospital mortality. Particularly for the Caprini RAM, an almost perfect link between the four risk levels of the RAM and inhospital mortality was observed. With an increase of risk levels from very low risk, low risk, moderate risk to high risk, the in-hospital mortality increased from 0 (0.0%), 5 (3.7%), and 14 (5.7%) to 85 (16.6%), respectively (P < 0.001).

Table 6. Associations of risk levels by Padua and Caprini RAM with in-hospital mortality and 6 month-mortality in VTE cases.

| Risk level | Number of patients (n = 902) | Mortality during hospitalization, n (%) | 6-Month mortality after discharge, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Padua Prediction Score | |||

| Low risk | 459 | 29 (6.3) | 30 (6.98) |

| High risk | 443 | 75 (16.9) | 41 (11.14) |

| P valuea | - | < 0.001 | 0.041 |

| OR (95%CI) | - | 3.02 (1.93–4.74) | 1.67 (1.02–2.74) |

| Caprini RAM | |||

| ≤ Moderate risk | 391 | 19 (4.9) | 21 (5.6) |

| High risk | 511 | 85 (16.6) | 50 (11.7) |

| P valuea | - | < 0.001 | 0.003 |

| OR (95%CI) | - | 3.91 (2.33–6.55) | 2.22 (1.31–3.78) |

| Very low risk | 9 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Low risk | 135 | 5 (3.7) | 7 (5.4) |

| Moderate risk | 247 | 14 (5.7) | 14 (6.0) |

| High risk | 511 | 85 (16.6) | 50 (11.7) |

| P valuea | - | < 0.001 | 0.023 |

RAM = risk assessment model, VTE = venous thromboembolism, OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval

chi-square

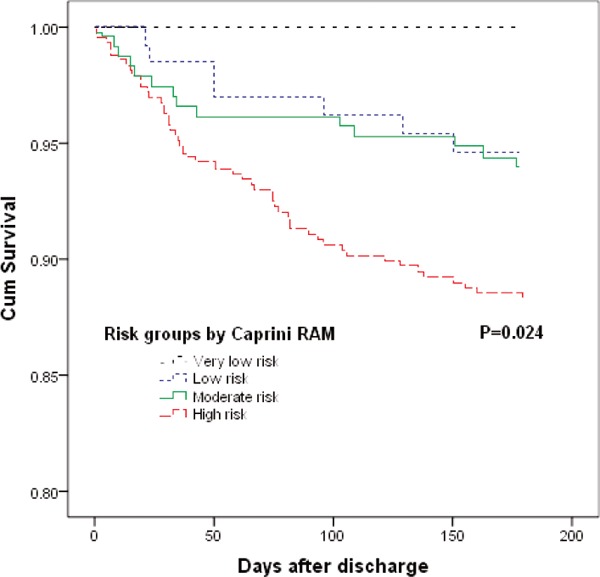

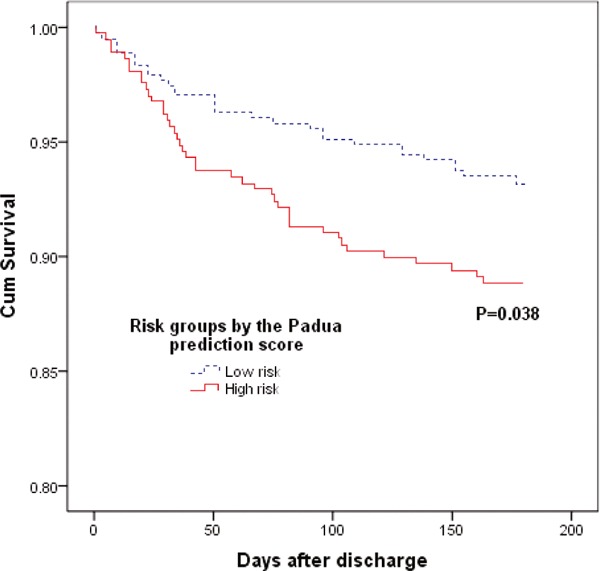

Of the surviving 798 VTE patients, 71 (8.9%) patients died during the 6-month follow-up. The mortality in each risk group by the PPS and Caprini RAM is also shown in Table 6. There was a significantly increased risk for mortality in patients with a higher VTE risk classification compared with patients with a lower risk classification according to the PPS and Caprini RAM (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. 1). The Caprini RAM exhibited an excellent value for the prediction of mortality after hospital discharge. With an increase in risk levels from very low risk, low risk, moderate risk to high risk, the mortality increased from 0 (0.0%), 7 (5.4%), and 14 (6.0%) to 50 (11.7%), respectively (P = 0.023).

Fig. 3.

Cumulative survival rates of the VTE patients after discharge by Caprini risk groups

(P value by the log-rank test for comparison of the outcome among groups at 6 months; VTE = venous thromboembolism; RAM = risk assessment model)

Supplemental Fig. 1.

Cumulative survival rates of the VTE patients after discharge by Padua risk groups (P value by the log-rank test for comparison of the outcome among groups at 6 months; VTE = venous thromboembolism)

Discussion

Medical patients have a high risk of VTE, and fatal PE occurs more frequently in medical than in surgical patients. However, the rationale for VTE prophylaxis in medical patients is not well understood compared with that in surgical patients34), as suggested by the extremely low proportion of medical inpatients who received VTE prophylaxis in our study. A widely validated RAM is critical to improve this situation.

The PPS was recommended by the ACCP-9 for medical inpatients, but it was based only on one cohort study carried out in Italy15), and some flaws in this RAM have been mentioned by some researchers22). Further validation of this RAM in other populations is needed. The Caprini RAM was developed originally for surgical and medical patients, and there are robust evidences to show its validity and practicability in surgical patients23–26). If also applied to medical inpatients, the process of VTE risk assessment would be considerably simplified in clinical practice because one RAM would be used for all unselected inpatients. In our study (which was carried out in a very large general hospital in China), we confirmed that both the PPS and Caprini RAM could effectively stratify the risk of VTE in medical inpatients. The Caprini RAM incorporated more significant risk factors of VTE and was more sensitive in being able to identify patients who needed prophylaxis. In addition, we found that the Caprini RAM could accurately predict the risk of in-hospital and 6-month mortality among VTE patients.

Few studies have tried to validate the PPS in medical patients, and a consensus has not been reached, which may be attributed to the different study populations and small sample sizes in some studies32, 35, 36). Similarly, studies employed to validate the Caprini RAM in medical inpatients have not reached consistent conclusions either4, 28–31). We found that the risk of VTE increased almost linearly with an increase in cumulative PPS and Caprini RAM risk scores after adjustment for VTE prophylaxis. High risk according to the two RAMs was associated with a significantly increased risk of VTE (OR = 5.01 for the PPS and 4.10 for the Caprini RAM). These findings suggested that the PPS and the Caprini RAM effectively stratified the risk of VTE in medical inpatients.

A few studies have compared the PPS with the Caprini RAM in medical inpatients. Previously, our research team found through a small case-control study that the Caprini-2005 RAM (the original version of the Caprini RAM) had higher sensitivity for the identification of high-risk patients than PPS31), but a more thorough analysis was not performed to draw a firm conclusion in the preliminary study. Through a retrospective case-control study similar to the present study, Liu et al. found that the AUC and Youden Index were higher in the Caprini-2005 RAM than in the PPS, thereby concluding that the Caprini-2005 RAM was more effective than the PPS for identification of medical inpatients at risk for VTE30). A modified version of the original Caprini-2005 RAM by ACCP is used more widely in clinical practice, so it would also be interesting to compare this updated Caprini RAM with the PPS in medical inpatients.

Using the information provided upon hospital admission, we found that the Caprini RAM could be used to identify 84.3% cases as moderate-to-high risk and 57.1% as high risk for VTE, to whom VTE prophylaxis (mainly pharmacologic prophylaxis if the risk of bleeding was low) was recommended according to the ACCP guidelines. The PPS could be used to identify only 49.1% of the VTE cases as high risk who would be recommended to receive VTE prophylaxis (pharmacologic prophylaxis if the risk of bleeding was low). That is, if we use the Caprini RAM to evaluate the VTE risk and guide prophylaxis in medical inpatients instead of PPS, at most an additional 35.2% of the VTE events may have a chance to be prevented by the administration of VTE prophylaxis according to ACCP guidelines.

The higher sensitivity of the Caprini RAM is attributed mostly to the comprehensive risk factors it includes: 39 known risk factors of VTE in the Caprini RAM vs. 11 risk factors in the PPS. Almost all the factors in the PPS can be seen in the Caprini RAM, with some in a slightly different form or with slightly different definitions. In our study population, nine out of 11 factors in the PPS were associated with an increased risk of VTE. The Caprini RAM included many more significant VTE risk factors not only for medical patients but also for orthopedic surgical, non-orthopedic surgical, gynecologic and obstetric, and cancer patients. In a large general hospital in China, we demonstrated that, except for the factors similar to those in the PPS, varicose veins, swollen legs (current), pregnancy or postpartum, fracture of the hip, pelvis, or leg (< 1 month), and family history of VTE (with a marginal P value) were also risk factors for medical inpatients. For example, even after adjustment for other confounding factors, pregnancy or postpartum continued to be associated with a 40.78-fold increased risk of VTE (95% CI 5.36–310.45). These results suggested that the current strategy of assessing the VTE risk of an inpatient using different RAMs based on the departments he/she is currently hospitalized in may not be effective or practical. A patient can be admitted into different departments or change departments during different periods of his/her disease course. The process of risk assessment for VTE in a hospital (especially a general hospital) would be simplified considerably if the same validated RAM, which applies to all unselected inpatients, is employed. Time can also be saved because physicians need to be familiar with only one RAM and need only to update the risk information based on the previous assessment in other departments (instead of evaluating his/her VTE risk again with a totally new RAM). Most importantly, our study showed that the Caprini RAM (which applies to medical and surgical inpatients) was not only an effective but also more sensitive RAM for VTE than PPS. We noted that the specificity of the Caprini RAM was not as good as that of PPS (24.6% of controls were classified as high risk by the Caprini RAM vs. 16.2% by the PPS). However, it is reasonable to focus more on sensitivity and sacrifice some specificity for the identification of patients who may benefit from VTE prophylaxis considering the severity of VTE occurrence if prophylaxis is not administered.

Another important reason for why we recommend the Caprini RAM instead of the PPS in medical inpatients or unselected patients is that the family history of VTE does not feature in the PPS. It is well-supported by the literature that family history is an independent and important risk factor for VTE, with a two-to-fourfold increased risk of primary VTE. Family history is a potentially useful surrogate genetic marker for VTE risk assessment. In clinical practice, family history may be more useful and practical for risk assessment than thrombophilia testing because it is easier to acquire, is linked to major or classical types of thrombophilia (e.g., defects of antithrombin, protein C/S, factor V Leiden, G20210A prothrombin), and can even be used to predict thrombophilic conditions which have yet to be recognized. In the VTE patients studied here, 0.8% had a family history of VTE compared with 0.1% in the controls, which was associated with a marginally increased risk of VTE. The prevalence of a family history of VTE reported in Caucasian VTE patients is much higher than that noted in our findings: 31.5% by Bezemer et al.37) and 20.5% by Zoller et al.38). The marginal effect in our study could be attributed to the (i) retrospective study design (which may have failed to identify family risk factors in some patients) or (ii) the relatively small sample size. The “true” incidence and effect of family history in Chinese patients may need further study; however, based on the current evidence, we favor the use of a RAM incorporating this risk factor in medical inpatients or unselected inpatients. In addition, the classifications of four risk levels by the Caprini RAM may provide more information for clinicians to guide decision-making for VTE prophylaxis based on the risk level of the patient compared with a binary low-/high-risk classification.

In our study, the in-hospital mortality of VTE patients was 11.5%, and the 6-month mortality after hospital discharge was 8.9%. It is surprising and interesting to see that the Caprini RAM can be used to precisely predict the risk of in-hospital and 6-month mortality in VTE patients. This is the first study to show that the Caprini RAM can be used to assess the prognosis in medical patients with VTE. When we look at the risk factors for VTE included in the RAM, we observe that many of them are also risk factors for a poor prognosis. This may be one of the underlying reasons why the Caprini RAM can also function as an index for comorbidities and disease severity. It will be convenient and useful if we can obtain information about the VTE risk and prognosis of a patient through a once-only assessment with a validated RAM.

Our study had three main strengths. First, we undertook a large, retrospective study involving adequate VTE cases and controls admitted into the medical departments of a 4300-bed general hospital in China during a 4-year period, supplemented by a prospective follow-up study. Second, this is the first study to validate the Caprini RAM accredited by the ACCP (not the Caprini-2005 RAM) and to compare the Caprini RAM accredited by the ACCP with the PPS in medical inpatients. Third, this is the first time the relationship between the Caprini RAM with the prognosis of VTE patients has been investigated.

Our study had three main limitations. First, the risk factors were identified in a retrospective manner that could not identify all risk factors. Second, the screening of hospitalized patients for asymptomatic VTE is not done routinely in our hospital. Thus, we may have failed to represent the prevalence of VTE in some control patients, especially those classified as high risk. However, considering that 68% of the controls received compression ultrasonography of the lower extremity before hospital discharge and that 112 controls (out of 242) were negative for D-Dimer, the potential effect is negligible. Third, matching controls to cases by the medical service added validity to the study in some regards, but made it difficult to evaluate some risk factors such as the presence of cancer31).

Conclusions

We found that both the PPS and Caprini RAM can effectively stratify the risk of VTE in medical inpatients, but the Caprini RAM may be considered as the first choice for medical inpatients from a general hospital because of: (ⅰ) the incorporation of comprehensive risk factors; (ⅱ) the higher sensitivity for the identification of patients who may benefit from prophylaxis; and (ⅲ) the potential prediction for short-term and long-term mortality. However, critics have rightfully criticized the Caprini RAM for its complexity and difficulty in taking the time to question patients with regard to all of these factors. Improved scoring methods should be explored to facilitate assessment, such as developing a patient-friendly questionnaire based on the RAM and using self-evaluation by the patient, or embedding the Caprini RAM into the electronic medical records system (which has been implemented widely) and adopting a computer-based automatic-evaluation strategy. Studies aiming to validate these two strategies of VTE risk assessment by the Caprini RAM are underway at our institution.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (for Young Scholars, grant 81600029 and 81400040) and by the National Key Research Program of China (grant 2016YFC1304202).

We greatly acknowledge the collaboration received from the staff of the VTE Registration Center and the Information Center of West China Hospital.

We are grateful for the help of Dr. Caprini (Joseph A. Caprini) for giving suggestions to the study design and paper writing.

We also want to thank Tian-xin Cong, Yang Chen, and Chao-li Shi for their work on the data collection.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1). Anderson FA, Jr., Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, Hosmer DW, Patwardhan NA, Jovanovic B, Forcier A, Dalen JE: A population-based perspective of the hospital incidence and case-fatality rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The Worcester DVT Study. Archives of internal medicine, 1991; 151: 933-938 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Goldhaber SZ, Dunn K, MacDougall RC: New onset of venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients at Brigham and Women's Hospital is caused more often by prophylaxis failure than by withholding treatment. Chest, 2000; 118: 1680-1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Goldhaber SZ, Tapson VF, Committee DFS: A prospective registry of 5,451 patients with ultrasound-confirmed deep vein thrombosis. Am J Cardiol, 2004; 93: 259-262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Abdel-Razeq HN, Hijjawi SB, Jallad SG, Ababneh BA: Venous thromboembolism risk stratification in medicallyill hospitalized cancer patients. A comprehensive cancer center experience. Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis, 2010; 30: 286-293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Dentali F, Douketis JD, Gianni M, Lim W, Crowther MA: Meta-analysis: anticoagulant prophylaxis to prevent symptomatic venous thromboembolism in hospitalized medical patients. Ann Intern Med, 2007; 146: 278-288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Alikhan R, Cohen AT: Heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in general medical patients (excluding stroke and myocardial infarction). Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2009; CD003747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Lloyd NS, Douketis JD, Moinuddin I, Lim W, Crowther MA: Anticoagulant prophylaxis to prevent asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized medical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis: JTH, 2008; 6: 405-414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Qaseem A, Chou R, Humphrey LL, Starkey M, Shekelle P, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of P : Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized patients: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med, 2011; 155: 625-632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, Cushman M, Dentali F, Akl EA, Cook DJ, Balekian AA, Klein RC, Le H, Schulman S, Murad MH: Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest, 2012; 141: e195S-e226S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Kucher N, Spirk D, Baumgartner I, Mazzolai L, Korte W, Nobel D, Banyai M, Bounameaux H: Lack of prophylaxis before the onset of acute venous thromboembolism among hospitalized cancer patients: the SWIss Venous ThromboEmbolism Registry (SWIVTER). Ann Oncol, 2010; 21: 931-935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Cohen AT, Tapson VF, Bergmann JF, Goldhaber SZ, Kakkar AK, Deslandes B, Huang W, Zayaruzny M, Emery L, Anderson FA, Jr., Investigators E : Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet, 2008; 371: 387-394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Tapson VF, Decousus H, Pini M, Chong BH, Froehlich JB, Monreal M, Spyropoulos AC, Merli GJ, Zotz RB, Bergmann JF, Pavanello R, Turpie AG, Nakamura M, Piovella F, Kakkar AK, Spencer FA, Fitzgerald G, Anderson FA, Jr., Investigators I : Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients: findings from the International Medical Prevention Registry on Venous Thromboembolism. Chest, 2007; 132: 936-945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Lester W, Freemantle N, Begaj I, Ray D, Wood J, Pagano D: Fatal venous thromboembolism associated with hospital admission: a cohort study to assess the impact of a national risk assessment target. Heart, 2013; 99: 1734-1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Spyropoulos AC, Raskob GE: New paradigms in venous thromboprophylaxis of medically ill patients. Thrombosis and haemostasis, 2017; 117: 1662-1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Barbar S, Noventa F, Rossetto V, Ferrari A, Brandolin B, Perlati M, De Bon E, Tormene D, Pagnan A, Prandoni P: A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: the Padua Prediction Score. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis: JTH, 2010; 8: 2450-2457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Caprini JA: Thrombosis risk assessment as a guide to quality patient care. Dis Mon, 2005; 51: 70-78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, Prandoni P, Bounameaux H, Goldhaber SZ, Nelson ME, Wells PS, Gould MK, Dentali F, Crowther M, Kahn SR: Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guide lines. Chest, 2012; 141: e419S-e496S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Mahan CE, Liu Y, Turpie AG, Vu JT, Heddle N, Cook RJ, Dairkee U, Spyropoulos AC: External validation of a risk assessment model for venous thromboembolism in the hospitalised acutely-ill medical patient (VTE-VALOURR). Thrombosis and haemostasis, 2014; 112: 692-699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Woller SC, Stevens SM, Jones JP, Lloyd JF, Evans RS, Aston VT, Elliott CG: Derivation and validation of a simple model to identify venous thromboembolism risk in medical patients. Am J Med, 2011; 124: 947-954 e942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Spyropoulos AC, Anderson FA, Jr., FitzGerald G, Decousus H, Pini M, Chong BH, Zotz RB, Bergmann JF, Tapson V, Froehlich JB, Monreal M, Merli GJ, Pavanello R, Turpie AGG, Nakamura M, Piovella F, Kakkar AK, Spencer FA, Investigators I : Predictive and associative models to identify hospitalized medical patients at risk for VTE. Chest, 2011; 140:706-714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Cohen AT, Alikhan R, Arcelus JI, Bergmann JF, Haas S, Merli GJ, Spyropoulos AC, Tapson VF, Turpie AG: Assessment of venous thromboembolism risk and the benefits of thromboprophylaxis in medical patients. Thrombosis and haemostasis, 2005; 94: 750-759 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Maynard G, Jenkins IH, Merli GJ: Venous thromboembolism prevention guidelines for medical inpatients: mind the (implementation) gap. J Hosp Med, 2013; 8: 582-588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Bahl V, Hu HM, Henke PK, Wakefield TW, Campbell DA, Jr., Caprini JA: A validation study of a retrospective venous thromboembolism risk scoring method. Ann Surg, 2010; 251: 344-350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Pannucci CJ, Bailey SH, Dreszer G, Fisher Wachtman C, Zumsteg JW, Jaber RM, Hamill JB, Hume KM, Rubin JP, Neligan PC, Kalliainen LK, Hoxworth RE, Pusic AL, Wilkins EG: Validation of the Caprini risk assessment model in plastic and reconstructive surgery patients. J Am Coll Surg, 2011; 212: 105-112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Stroud W, Whitworth JM, Miklic M, Schneider KE, Finan MA, Scalici J, Reed E, Bazzett-Matabele L, Straughn JM, Jr., Rocconi RP: Validation of a venous thromboembolism risk assessment model in gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol, 2014; 134: 160-163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Cassidy MR, Rosenkranz P, McAneny D: Reducing post-operative venous thromboembolism complications with a standardized risk-stratified prophylaxis protocol and mobilization program. J Am Coll Surg, 2014; 218: 1095-1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, Karanicolas PJ, Arcelus JI, Heit JA, Samama CM: Prevention of VTE in non-orthopedic surgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest, 2012; 141: e227S-e277S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Grant PJ, Greene MT, Chopra V, Bernstein SJ, Hofer TP, Flanders SA: Assessing the Caprini Score for Risk Assessment of Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitalized Medical Patients. Am J Med, 2016; 129: 528-535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Zakai NA, Wright J, Cushman M: Risk factors for venous thrombosis in medical inpatients: validation of a thrombosis risk score. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis: JTH, 2004; 2: 2156-2161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Liu X, Liu C, Chen X, Wu W, Lu G: Comparison between Caprini and Padua risk assessment models for hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: a retrospective study. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg, 2016; 23: 538-543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Zhou H, Wang L, Wu X, Tang Y, Yang J, Wang B, Yan Y, Liang B, Wang K, Ou X, Wang M, Feng Y, Yi Q: Validation of a venous thromboembolism risk assessment model in hospitalized chinese patients: a case-control study. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2014; 21: 261-272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Vardi M, Ghanem-Zoubi NO, Zidan R, Yurin V, Bitterman H: Venous thromboembolism and the utility of the Padua Prediction Score in patients with sepsis admitted to internal medicine departments. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH, 2013; 11: 467-473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Zhou HX, Peng LQ, Yan Y, Yi Q, Tang YJ, Shen YC, Feng YL, Wen FQ: Validation of the Caprini risk assessment model in Chinese hospitalized patients with venous thromboembolism. Thrombosis research, 2012; 130: 735-740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Monreal M, Kakkar AK, Caprini JA, Barba R, Uresandi F, Valle R, Suarez C, Otero R, Investigators R : The outcome after treatment of venous thromboembolism is different in surgical and acutely ill medical patients. Findings from the RIETE registry. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH, 2004; 2: 1892-1898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Nendaz M, Spirk D, Kucher N, Aujesky D, Hayoz D, Beer JH, Husmann M, Frauchiger B, Korte W, Wuillemin WA, Jager K, Righini M, Bounameaux H: Multicentre validation of the Geneva Risk Score for hospitalised medical patients at risk of venous thromboembolism. Explicit ASsessment of Thromboembolic RIsk and Prophylaxis for Medical PATients in SwitzErland (ESTIMATE). Thrombosis and haemostasis, 2014; 111: 531-538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). Bogari H, Patanwala AE, Cosgrove R, Katz M: Risk-assessment and pharmacological prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with chronic liver disease. Thrombosis research, 2014; 134: 1220-1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37). Bezemer ID, van der Meer FJ, Eikenboom JC, Rosendaal FR, Doggen CJ: The value of family history as a risk indicator for venous thrombosis. Archives of internal medicine, 2009; 169: 610-615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Zoller B, Pirouzifard M, Sundquist J, Sundquist K: Family history of venous thromboembolism and mortality after venous thromboembolism: a Swedish population-based cohort study. Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis, 2017; 43: 469-475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]