Key Points

Question

To what extent can clonal hematopoiesis (CH) lead to misclassification of blood-derived somatic mutations as tumor-derived somatic mutations in clinical next-generation sequencing performed in the absence of a matched blood control?

Findings

In this gene-sequencing study including a cohort of 17 469 patients with advanced cancer, paired next-generation sequencing results show that 5% of the patients would have at least 1 CH-associated mutation misattributed as tumor derived in the absence of matched blood sequencing.

Meaning

As a subset of CH-derived alterations involve actionable cancer genes, failure to recognize such mutations as blood derived may lead to erroneous treatment recommendations; sequencing matched blood can be used to distinguish frequent CH somatic mutations from those in the solid-tumor cells and perhaps lead to more accurate precision therapy.

This gene-sequencing study identifies and quantifies clonal hematopoiesis–related mutations in patients with solid-tumor cancers using matched tumor-blood sequencing and examines the proportion that would be misattributed to the tumor based on tumor-only sequencing (unmatched analysis).

Abstract

Importance

Although clonal hematopoiesis (CH) is well described in aging healthy populations, few studies have addressed the practical clinical implications of these alterations in solid-tumor sequencing.

Objective

To identify and quantify CH-related mutations in patients with solid tumors using matched tumor-blood sequencing, and to establish the proportion that would be misattributed to the tumor based on tumor-only sequencing (unmatched analysis).

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective analysis of samples from 17 469 patients with solid cancers who underwent prospective clinical sequencing of DNA isolated from tumor tissue and matched peripheral blood using the MSK-IMPACT assay between January 2014 and August 2017.

Main Outcomes and Measures

We identified the presence of CH-related mutations in each patient’s blood leukocytes and quantified the fraction of DNA molecules harboring the mutation in the corresponding matched tumor sample.

Results

The mean age of the 17 469 patients with cancer at sample collection was 59.2 years (range, 0.3-98.9 years); 53.6% were female. We identified 7608 CH-associated mutations in the blood of 4628 (26.5%) patients. A total of 1075 (14.1%) CH-associated mutations were also detectable in the matched tumor above established thresholds for calling somatic mutations. Overall, 912 (5.2%) patients would have had at least 1 CH-associated mutation erroneously called as tumor derived in the absence of matched blood sequencing. A total of 1061 (98.7%) of these mutations were absent from population scale databases of germline polymorphisms and therefore would have been challenging to filter informatically. Annotating variants with OncoKB classified 534 (49.7%) as oncogenic or likely oncogenic.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study demonstrates how CH-derived mutations could lead to erroneous reporting and treatment recommendations when tumor-only sequencing is used.

Introduction

Clinical next-generation sequencing (NGS) of tumor samples is increasingly used to identify targetable genomic alterations and guide treatment selection in patients with cancer.1,2,3 While patient-matched blood control samples are required to distinguish between somatic and inherited variants, practical challenges in the implementation of clinical NGS have led to the frequent use of assays that analyze unmatched tumors (“tumor-only”).2,4 While this is generally sufficient to identify cancer mutational hot spots,4 for more comprehensive assays, the identification and filtering of germline variants can be challenging. Strategies to filter presumptive germline variants include the removal of common variants based on population frequencies and the retention of actionable variants.5

Clonal hematopoiesis (CH) is the somatic acquisition of genomic alterations in hematopoietic stem and/or progenitor cells, leading to clonal expansion.6 In patients with cancer, CH is a common occurrence, associated with aging, smoking, and radiation therapy.7 Clonal hematopoiesis is associated with increased risk of therapy-related hematologic malignant neoplasms, and genes frequently mutated in CH are also commonly altered in hematological malignant neoplasms.7,8 Recent reports of JAK2 V617F, a common leukemia mutation, in solid tumors9,10 prompted us to examine the degree to which high prevalence of CH in patients with cancer could confound the results of tumor-only genomic profiling due to the presence of infiltrating leukocytes.10 Herein, we studied whether CH mutations may be misattributed as somatic tumor variants in patients when a matched normal sample is not sequenced and that some are actionable alterations, which could result in erroneous treatment recommendations.11

Methods

We analyzed deep-coverage targeted NGS data of paired blood and tumor samples, as described previously,7 from 17 469 patients with advanced solid malignant neoplasms sequenced using the MSK-IMPACT platform between January 2014 and August 2017. This study was approved by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (IRB), and written consent was obtained from most participants. An IRB waiver was obtained to include patients who did not sign the consent form.

To identify the prevalence of CH alterations detected in solid-tumor specimens, we considered variants passing our detection thresholds for somatic mutation calling in tumor NGS data.12 We retained CH alterations with a read depth of at least 20, alternate allele depth of at least 8, and a variant allele fraction (VAF) of at least 0.02 in the tumor sample. Alterations were annotated with population frequencies from 1000 Genomes, ExAC, and gnomAD databases to identify variants that would be potentially filtered out by tumor-only sequencing.

Clonal hematopoiesis alterations detected in solid tumors were annotated with OncoKB, a knowledge base that identifies oncogenic alterations and ranks potentially actionable alterations based on the level of evidence supporting that alteration as a predictive biomarker of drug sensitivity to US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved or investigational therapies for a defined cancer type.11

A generalized linear model was used to correlate patient age with the presence of CH mutations in solid tumors (CH-ST), correcting for sex and cancer type. P ≤ .05 was considered significant. Fisher exact test followed by Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate assessment was used to look for associations between tumor type and presence of CH-ST variants. Tumor types with a false discovery rate of 0.05 or less were considered significant.

Results

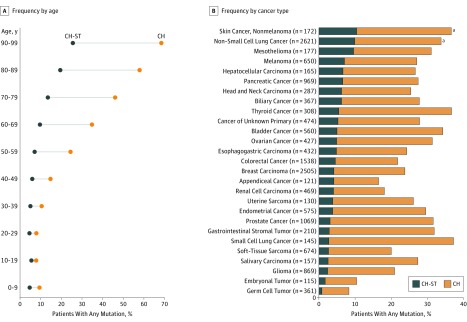

We first examined MSK-IMPACT sequencing data of matched tumor and blood samples of 17 469 patients with cancer with 69 cancer types (eTable in Supplement 1). The median coverage was 723× for tumor samples and 486× for blood samples. The mean patient age at sample collection was 59.2 years (range, 0.3-98.9 years). Mutational analysis of hematopoietic cells identified 7608 presumptive somatic, nonsilent mutations in 396 genes from 4628 patients (26.5%). This led to identification of 1075 mostly nonrecurrent CH mutations (14.1%) (eSpreadsheet in Supplement 2) in solid tumors (CH-ST) from 912 patients (5.2%) with a median VAF of 0.04 (range, 0.02-0.21) in the solid-tumor samples and 0.16 (range, 0.04-0.53) in the matched blood samples. The incidence of CH-ST mutations increased with age (P < .001) as with CH (Figure 1A) and were most commonly observed in patients with skin cancer and non–small cell lung cancer (Figure 1B). The most commonly altered genes were DNMT3A, TET2, and PPM1D (Figure 2A).

Figure 1. Clonal Hematopoiesis (CH)-Derived Mutations Observed in Solid Tumors (CH-ST).

A, Frequency of CH-ST mutations, identified by analyzing matched normal blood and solid-tumor data, increases with patient age. B, Nonmelanoma skin cancer, lung cancer, and mesothelioma have the highest rates of CH-ST mutations observed.

aTumor types in which significant enrichment is observed for CH-ST mutations (Fisher exact test, Benjamini-Hochberg corrected P = .03 for nonmelanoma skin cancer and P < .001 for non–small cell lung cancer).

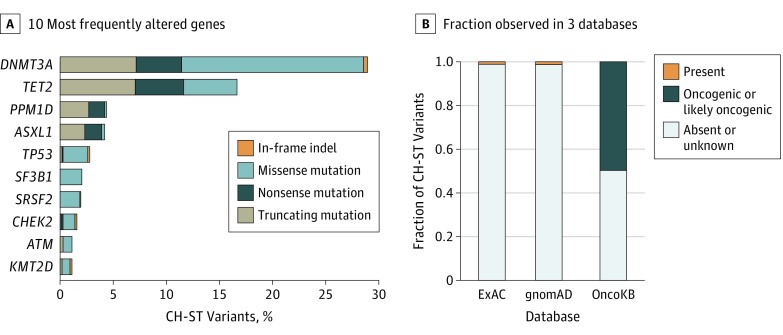

Figure 2. Characteristics of Clonal Hematopoiesis in Solid Tumor (CH-ST) Mutations.

A, Top 10 frequently altered genes with CH-ST mutations. B, Fraction of CH-ST mutations observed in ExAC, gnomAD, and OncoKB databases.

Next, we sought to determine what proportion of these variants would have been retained by a tumor-only variant calling pipeline. Comparison of population frequencies in ExAC and gnomAD indicated that 1061 (98.7%) of these mutations were absent from the general population. Annotating CH-ST variants with OncoKB classified 534 (49.7%) CH variants as oncogenic or likely oncogenic (Figure 2B). Seventeen of 534 (3.2%) CH-ST mutations were associated with approved or investigational therapies (Table). Several of these are mutations common to both hematologic and solid cancers, such as IDH1/2, and can be used as biomarkers of targeted therapy. One example is a KRAS G12R mutation observed in a 77-year-old woman with colorectal cancer, which we identified as arising from CH based on higher VAF in blood than in tumor (blood VAF = 0.087; tumor VAF = 0.041) (Table and eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). Given that FDA-approved therapies require wild-type status for KRAS, misattribution of this mutation in the tumor without a matched-blood sample could lead to the withholding of treatment that could benefit the patient.

Table. Clonal Hematopoiesis in Solid Tumor Mutations With Treatment Implications Based on OncoKB Database.

| Sex/Age at Blood Sampling, y | Gene | Amino Acid Change | VAF | Cancer Type | Highest OncoKB Levela | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | Tumor | |||||

| M/84 | BRCA2 | Q3156* | 0.344 | 0.118 | Melanoma | 2B |

| M/74 | IDH2 | R140Q | 0.405 | 0.082 | Pancreatic | 2B |

| F/72 | IDH2 | R140Q | 0.298 | 0.063 | NSCLC | 2B |

| M/68 | IDH2 | R140Q | 0.162 | 0.048 | NSCLC | 2B |

| M/76 | IDH2 | R140Q | 0.270 | 0.039 | NSCLC | 2B |

| F/59 | BRCA1 | E1836Q | 0.332 | 0.036 | Endometrial | 2B |

| F/74 | NRAS | G12R | 0.442 | 0.119 | NSCLC | 3B |

| F/80 | NRAS | G12V | 0.081 | 0.037 | Uterine sarcoma | 3B |

| F/83 | IDH1 | R132H | 0.077 | 0.033 | Melanoma | 3B |

| F/70 | IDH1 | R132C | 0.048 | 0.022 | Melanoma | 3B |

| M/43 | PTEN | D24G | 0.348 | 0.174 | Colorectal | 4 |

| F/50 | NF1 | R2616* | 0.237 | 0.095 | Breast carcinoma | 4 |

| M/68 | KRAS | G60D | 0.297 | 0.094 | Prostate | 4 |

| M/55 | NF1 | X1554_splice | 0.105 | 0.049 | Melanoma | 4 |

| M/79 | NF1 | F256Lfs* | 0.141 | 0.043 | Prostate | 4 |

| M/78 | KRAS | A146P | 0.132 | 0.035 | Skin cancer, nonmelanoma | 4 |

| F/77 | KRAS | G12R | 0.087 | 0.041 | Colorectal | R1 |

Abbreviations: FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer; VAF, variant allele fraction.

Level 2B indicates alterations that are standard-of-care biomarkers of response to an FDA-approved drug in another indication. Level 3B indicates compelling clinical evidence supporting the biomarker as being predictive of response to a drug in another indication. Level 4 indicates compelling biological evidence supporting the biomarker as being predictive of response to a drug. Level R1 indicates standard-of-care biomarker predictive of resistance to an FDA-approved drug in this indication.

Another example of a targetable alteration is a presumed CH-associated BRCA2 Q3156* mutation observed in an 84-year-old man with melanoma and a history of pancreatic cancer at 0.118 VAF in the tumor (eFigure 2A and B in Supplement 1); this might have incorrectly prompted consideration of PARP (poly adenosine diphosphate ribose polymerase) inhibitor therapy. However, given the patient’s history of multiple cancers and the blood VAF of 0.344, we considered the possibility that the BRCA2 mutation was a pathogenic germline variant with loss of heterozygosity in the tumor. Allele-specific copy number analysis by FACETS13 revealed retention of both alleles, ruling out loss of heterozygosity in the tumor cells (eFigure 2C in Supplement 1). Sanger sequencing of the patient’s blood, tumor sample, saliva, buccal swap, and normal colon tissues confirmed that the variant was acquired in the hematopoietic compartment (eFigure 2D in Supplement 1). Taken together, these results demonstrate the perils of both tumor-only sequencing platforms and blood-only germline sequencing,14 where CH-ST mutations can confound results and lead to misguided clinical management.

Discussion

As the application of NGS technologies continues to expand in clinical settings, it is important to identify sources of potential discrepancies and misleading results. While the use of population scale databases strengthened by cancer databases is a common method of identifying presumptive somatic mutations with tumor-only sequencing, it should be noted that different methodologies can differentially affect reporting and clinical decisions. Even then, correctly attributing hot spot mutations common to both solid tumors and hematological malignant neoplasms to the correct cell of origin, such as mutations in IDH1/2 and KRAS, is difficult in the absence of paired tumor-blood sequencing. This is further exemplified in a recent report10 in which activating JAK2 V617F mutations were described in the context of lung cancer based on unmatched tumor sequencing. Because JAK2 mutations have not been identified by other large-scale sequencing studies, the finding of JAK2 V617K mutations in that study likely represents an artifact resulting from detection of CH-ST mutations in tumor due to leukocyte infiltration.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is that laboratories could establish different criteria for their variant filters, such as reporting only hot-spot mutations or using internal databases to identify recurrent likely germline mutations. While these could help with identifying CH-ST mutations, neither would eliminate them completely.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the largest report on CH-ST based on a population of patients with advanced cancer. While a small fraction of patients are affected overall, we show that the prevalence of CH-ST is higher in older patients and that tumor-only sequencing results should be evaluated carefully, especially if treatment decisions are based on the variant results.

eFigure 1. Details of the KRAS mutation identified as CH-ST

eFigure 2. Sequencing of matched tumor and tissue samples confirms CH derived origin of variant found with high VAF in blood

eTable. List of cancer types included in the study along with patient counts, minimum age, median age, maximum age, and median tumor content for each cancer type

eSpreadsheet. List of all CH-ST mutations identified in this study along with counts of patients each mutation is observed in

References

- 1.Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med. 2017;23(6):703-713. doi: 10.1038/nm.4333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartmaier RJ, Albacker LA, Chmielecki J, et al. High-throughput genomic profiling of adult solid tumors reveals novel insights into cancer pathogenesis. Cancer Res. 2017;77(9):2464-2475. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sholl LM, Do K, Shivdasani P, et al. Institutional implementation of clinical tumor profiling on an unselected cancer population. JCI Insight. 2016;1(19):e87062. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.87062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boland GM, Piha-Paul SA, Subbiah V, et al. Clinical next generation sequencing to identify actionable aberrations in a phase I program. Oncotarget. 2015;6(24):20099-20110. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiltemann S, Jenster G, Trapman J, van der Spek P, Stubbs A. Discriminating somatic and germline mutations in tumor DNA samples without matching normals. Genome Res. 2015;25(9):1382-1390. doi: 10.1101/gr.183053.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busque L, Patel JP, Figueroa ME, et al. Recurrent somatic TET2 mutations in normal elderly individuals with clonal hematopoiesis. Nat Genet. 2012;44(11):1179-1181. doi: 10.1038/ng.2413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coombs CC, Zehir A, Devlin SM, et al. Therapy-related clonal hematopoiesis in patients with non-hematologic cancers is common and associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21(3):374-382.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2488-2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J, Axilbund J, Dalton WB, et al. . A polycythemia vera jak2 mutation masquerading as a duodenal cancer mutation. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(12):1495-1498. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li SD, Ma M, Li H, et al. Cancer gene profiling in non-small cell lung cancers reveals activating mutations in JAK2 and JAK3 with therapeutic implications. Genome Med. 2017;9(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0478-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips SM, et al. OncoKB: a precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis Oncol. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): a hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing clinical assay for solid tumor molecular oncology. J Mol Diagn. 2015;17(3):251-264. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen R, Seshan VE. FACETS: allele-specific copy number and clonal heterogeneity analysis tool for high-throughput DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(16):e131. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weitzel JN, Chao EC, Nehoray B, et al. Somatic TP53 variants frequently confound germ-line testing results [published online November 30, 2017]. Genet Med. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Details of the KRAS mutation identified as CH-ST

eFigure 2. Sequencing of matched tumor and tissue samples confirms CH derived origin of variant found with high VAF in blood

eTable. List of cancer types included in the study along with patient counts, minimum age, median age, maximum age, and median tumor content for each cancer type

eSpreadsheet. List of all CH-ST mutations identified in this study along with counts of patients each mutation is observed in