Abstract

The creation of intergeneric somatic hybrids between Citrus and Poncirus is an efficient approach for citrus rootstock breeding, offering the possibility of combining beneficial traits from both genera into novel rootstock lineages. These somatic hybrids are also used as parents for further tetraploid sexual breeding. In order to optimize these latter breeding schemes, it is essential to develop knowledge on the mode of inheritance in the intergeneric tetraploid hybrids. We assessed the meiotic behavior of an intergeneric tetraploid somatic hybrid resulting from symmetric protoplast fusion of diploid Citrus reticulata and diploid Poncirus trifoliata. The analysis was based on the segregation patterns of 16 SSR markers and 9 newly developed centromeric/pericentromeric SNP markers, representing all nine linkage groups of the Citrus genetic map. We found strong but incomplete preferential pairing between homologues of the same ancestral genome. The proportion of gametes that can be explained by random meiotic chromosome associations (τ) varied significantly between chromosomes, from 0.09 ± 0.02 to 0.47 ± 0.09, respectively, in chromosome 2 and 1. This intermediate inheritance between strict disomy and tetrasomy, with global preferential disomic tendency, resulted in a high level of intergeneric heterozygosity of the diploid gametes. Although limited, intergeneric recombinations occurred, whose observed rates, ranging from 0.09 to 0.29, respectively, in chromosome 2 and 1, were significantly correlated with τ. Such inheritance is of particular interest for rootstock breeding because a large part of the multi-trait value selected at the teraploid parent level is transmitted to the progeny, while the potential for some intergeneric recombination offers opportunities for generating plants with novel allelic combinations that can be targeted by selection.

Keywords: Citrus, somatic hybrid, tetraploid, disomic, tetrasomic, intermediate inheritance, SSR markers, SNP markers

Introduction

Polyploidization is a major evolutionary pathway (Ramsey and Schemske, 2002; Adams and Wendel, 2005; Soltis et al., 2009) with important implications for breeding. In plants, polyploid lineages arise naturally through the union of unreduced gametes (Harlan and deWet, 1975; Ramsey and Schemske, 1998) and chromosome doubling of somatic cells (Aleza et al., 2011). They can also be artificially produced by treatment of cell tissue with colchicine (Aleza et al., 2009) or somatic hybridization (Grosser et al., 2000). Natural polyploidization is often associated with hybridization between species, resulting in allopolyploidy. Allopolyploids typically show strict preferential pairing in meiosis, resulting in disomic inheritance, without an opportunity for interspecific recombination (Soltis and Soltis, 2000; Pairon and Jacquemart, 2005). In allotetraploids, disomic inheritance leads diploid gametes to display interspecific heterozygosity throughout the genome. However, it has been recognized that even allopolyploids that combine strongly diverged parental genomes may have occasional nonhomologous chromosome pairing, leading to nonstrict disomic inheritance and intergenomic recombination (Stebbins, 1947; Sybenga, 1994, 1996; Udall and Wendel, 2006; Stift et al., 2008; Jeridi et al., 2012). Differential chromosome pairing affinities is therefore an essential component determining species evolution in natural polyploid populations. It is also a key parameter to design efficient polyploid breeding strategies, as it strongly impacts the inheritance of chromosome fragments and agronomical traits. Molecular marker analysis is a powerful approach to study the genetic structures of gametes produced by allopolyploid organisms, and in turn to estimate the preferential pairing pattern and its impacts on genome fragment inheritance and recombination (Allendorf and Danzmann, 1997; Barone et al., 2002; Jannoo et al., 2004; Bousalem et al., 2006; Landergott et al., 2006).

In citrus, polyploidy has been described to improve adaptation to different stresses and resilience (Mouhaya et al., 2010; Podda et al., 2013; Allario et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2017; Dutra de Souza et al., 2017; Oliveira et al., 2017; Oustric et al., 2017, 2018), and several teams worldwide have been developing rootstock breeding at the tetraploid level (Grosser and Chandler, 2000; Grosser et al., 2000, 2015; Ollitrault et al., 2000, 2007; Guo et al., 2007; Grosser and Gmitter, 2010; Dambier et al., 2011; Guerra et al., 2016). Many of these programs focus on combinations of Citrus species with Poncirus, a related genus. Poncirus and Citrus species are sexually compatible (Spiegel-Roy and Goldschmidt, 1996). However, molecular phylogenic studies based on whole genome resequencing data have demonstrated substantial genetic differentiation (Carbonell-Caballero et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2018). Poncirus has agriculturally useful traits such as cold adaptation, tolerances to Phytophthora species and nematodes, and resistance to the citrus tristeza virus (CTV; Yang et al., 2001). It has also been described to provide some tolerance to Huanglongbing, a devastating citrus disease caused by the phloem bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter sp. (Stover et al., 2010). However, Poncirus suffers iron chlorosis on alkaline soils and it is susceptible to salinity, which limits its use in some areas, particularly in the Mediterranean Basin (Spiegel-Roy and Goldschmidt, 1996). Rootstock breeding programs attempt to combine beneficial Poncirus traits with abiotic stress tolerance traits present in Citrus species. Although some interesting diploid intergeneric sexual hybrids [e.g., citrange (P. trifoliata × C. sinensis) and citrumelo (P. trifoliata × C. paradisi)] have been produced, the long generation times, partial apomixes, and segregation of beneficial allelic combinations due to the high heterozygosity of parental genotypes (Herrero et al., 1996; Ollitrault et al., 2003; Barkley et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2018) limit the efficiency of conventional diploid breeding. Somatic hybridization is an efficient alternative for citrus rootstock breeding as it allows breeders to combine favorable parental genes regardless of their heterozygosity level (Ollitrault et al., 1998; Grosser and Gmitter, 2010; Dambier et al., 2011; Ruiz et al., 2018). In citrus, somatic hybridization has also been successfully applied to diversify the tetraploid gene pool used as parent for triploid breeding (Grosser et al., 2000; Ollitrault et al., 2007, 2008) and to generate hybrids (Aleza et al., 2016b). The “Tetrazyg” approach (Grosser and Gmitter, 2010) was introduced to breed new tetraploid rootstock by sexual hybridization using selected allotetraploid somatic hybrid rootstock as parent material. In order to optimize the efficiency of the “Tetrazyg” strategy, it is essential to develop knowledge on the mode of inheritance in the allotetraploid hybrids.

Previous studies on tetraploid citrus revealed different meiotic behavior. Weak or no preferential pairing of homologous chromosomes (i.e., mostly tetrasomic inheritance) with bivalents and quadrivalent meiotic configurations was observed for a mandarin + lemon somatic hybrid (Kamiri et al., 2011), for a somatic hybrid between tangelo and pummelo (Xie et al., 2015), and doubled-diploid clementine (Aleza et al., 2016a). By contrast, the doubled-diploid “Mexican” lime had predominantly disomic segregation (Rouiss et al., 2018). However, no data were available on the inheritance mode of tetraploid Citrus-Poncirus intergeneric hybrids.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the mode of inheritance in a tetraploid intergeneric somatic hybrid called Flhorag1 obtained through protoplast fusion between Citrus reticulata cv “Willowleaf” mandarin and Poncirus trifoliata cv “Pomeroy” (Ollitrault et al., 2000). This somatic hybrid provided improved agronomic traits when used as rootstock with sweet orange (Dambier et al., 2011). For this purpose, a triploid progeny population (2n = 3x = 27) resulting from “Chandler” pummelo × Flhorag1 sexual hybridization was genotyped at 19 simple sequence repeat (SSR) and 9 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) loci to infer the allelic constitution of gametes produced by the somatic hybrid. The likelihood-based approaches proposed by Stift et al. (2008) for multi allelic loci and Aleza et al. (2016a) for di-allelic loci in duplex tetraploid were applied to analyze the meiotic behavior of Flhorag1. The implications for citrus rootstock breeding are discussed with a special focus on intergeneric heterozygosity restitution.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

An intergeneric somatic hybrid between a diploid (2n = 2x = 18) Citrus reticulata Blanco (“Willowleaf” mandarin SRA 133, hereafter called WLM) and a diploid (2n = 2x = 18) Poncirus trifoliata L. (“Pomeroy” trifoliate orange SRA 1074, hereafter called PON) was previously obtained by protoplast electrofusion (Ollitrault et al., 2000). To assess the inheritance of the tetraploid somatic hybrid (2n = 4x = 36; hereafter called Flhorag1), we performed a cross with diploid Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr (2n = 2x = 18) (“Chandler” pummelo SRA 608, hereafter called CHA), using Flhorag1 as pollen donor. The pollen was collected on the mother tree of Flhorag1 (the plant directly regenerated from protoplast fusion).

CHA was chosen because it is self-incompatible, not apomictic, and it is genetically well differentiated from both WLM and PON. Cross was performed at the San Giuliano Research Station (Corsica, France). Recovered mature seeds were germinated in vitro in MT medium (Murashige and Tucker, 1969) supplemented with 30 g l-1 sucrose and 1 mg l-1 GA3 (Ollitrault et al., 1996). The obtained plants were grafted on “Volkamer” lemon (C. limonia Osbeck) and further grown in a growth chamber.

Flow Cytometry and Cytogenetic Analyses

The ploidy of the progeny was determined by flow cytometry and confirmed by chromosome counts. For flow cytometry, approximately 0.5 cm2 of plantlet leaf and a similar amount of leaf tissue from a diploid reference C. madurensis (2n = 2x = 18) were chopped with a sharp razor blade in 250 μl of extraction buffer (Partec Cystain UV PreciseP) to isolate intact nuclei. After filtering the resulting suspension (30 μm pore size), 800 μl of DAPI (4-6-diamine-2-phenylindol) staining buffer was added (Partec, Cystain UV Precise P Staining Buffer). Samples were analyzed with a PA-I flow cytometer (Partec, Germany). We followed the protocol of D’Hont et al. (1996) for chromosome preparations. Briefly, fresh young leaf tissues were treated in 0.04% hydroxyquinoline for 4 h at room temperature and fixed for 48 h in 3:1 ethanol:acetic acid and stored at 4°C in 70% ethanol. The preparations were then treated for 20 min in 5N HCl and washed with distilled water. Finally, the tissue was deposited on microscope slides, stained with a drop of DAPI staining buffer (Partec, Cystain UV Precise P Staining Buffer), and squashed. Chromosomes were counted under an Eclipse 80i fluorescence microscope (Nikon Instruments, France).

DNA Extraction

DNA was extracted from leaves using a modified mixed alkyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (MATAB) procedure (Gawel and Jarret, 1991). The DNA concentration was determined using the Hoechst 33258 (Sigma Chemical Co., MO, United States) protocol (Sambrook and Russell, 2006). Samples were diluted with MQ sterile water and stored at -20°C until use.

SSR Amplification

From previously identified, characterized, and mapped SSR loci (Froelicher et al., 2008; Luro et al., 2008; Ollitrault et al., 2010, 2012), we selected 19 loci (Table 1) that (i) were polymorphic between WLM and PON (diploid parents of the tetraploid somatic hybrid) and the seed parent CHA, and (ii) represented each of the nine linkage groups of the clementine genetic map (Ollitrault et al., 2012). Primers were labeled with WELLRED fluorochrome PA-2(dye2), PA-3(dye3), or PA-4(dye4) (Beckman-Coulter, CA, United States) and synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich (France). Among the selected markers, the mCrCIR02F12 locus was known to have a frequent null allele in Poncirus accessions (unpublished data), and the PON parent was suspected to be heterozygous (A0).

Table 1.

Characteristics of selected SSR markers used for the Willowleaf mandarin + Pomeroy Poncirus somatic hybrid (Flhorag1) allelic inheritance.

| Locus | EMBL | Linkage Group | Primer Sequence (5′–3′) | Tm (C°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CiBE5055 | ET111355 | 1 | F:AACAGTGGTTCTGGGAAATAG | 55 |

| R:GGTGGTCTCAAAGTCATCATC | ||||

| MEST431 | FC883898 | 1 | F: GAGCTCAAAACAATAGCCGC | 55 |

| R: CATACCTCCCCGTCCATCTA | ||||

| mCrCIR02D09 | FR677569 | 2 | F:AATGATGAGGGTAAAGATG | 55 |

| R:ACCCATCACAAAACAGA | ||||

| MEST46 | FC901824 | 2 | F: AACCAGAATCAGAACCCGA | 55 |

| R: GGTGAGCATCTGGACGACTT | ||||

| mCrCIR02G12 | FR677575 | 3 | F:AAACCGAAATACAAGAGTG | 55 |

| R:TCCACAAACAATACAACG | ||||

| mCrCIR02D04b | FR677564 | 4 | F:CTCTCTTTCCCCATTAGA | 50 |

| R:AGCAAACCCCACAAC | ||||

| mCrCIR03D12a | FR677577 | 4 | F:GCCATAAGCCCTTTCT | 50 |

| R:CCCACAACCATCACC | ||||

| mCrCIR07D06 | FR677581 | 4 | F:CCTTTTCACAGTTTGCTAT | 55 |

| R:TCAATTCCTCTAGTGTGTGT | ||||

| mCrCIR03F05 | FR692364 | 4 | F:CTAAGGAAGAGTAGAGAGCA | 50 |

| R:TAAAATCCAAGGTTCCA | ||||

| mCrCIR01F08a | AM489737 | 5 | F:ATGAGCTAAAGAGAAGAGG | 50 |

| R:GGACTCAACACAACACAA | ||||

| mCrCIR07E12 | AM489750 | 5 | F:TGTAGTCAAAAGCATCAC | 50 |

| R:TCTATGATTCCTGACTTTA | ||||

| mCrCIR02F12 | FR677570 | 6 | F:GGCCATTTCTCTGATG | 55 |

| R:TAACTGAGGGATTGGTTT | ||||

| mCrCIR02D03 | FR692360 | 7 | F:CAGACAACAGAAAACCAA | 55 |

| R:GACCATTTTCCACTCAA | ||||

| mCrCIR07E05 | AM489749 | 7 | F:GGAGAACAAAACACAATG | 50 |

| R:ATCTTTCGGACAATCTT | ||||

| mCrCIR02A09 | FR677568 | 8 | F:ACAGAAGGTAGTATTTTAGGG | 50 |

| R:TTGTTTGGATGGGAAG | ||||

| mCrCIR07B05 | AM489747 | 8 | F:TTTGTTCTTTTTGGTCTTTT | 50 |

| R:CTTTTCTTTCCTAGTTTCCC | ||||

| mCrCIR02G02 | FR677572 | 8 | F:CAATAAGAAAACGCAGG | 55 |

| R:TGGTAGAGAAACAGAGGTG | ||||

| mCrCIR07C09 | AJ567410 | 9 | F:GACCCTGCCTCCAAAGTATC | 55 |

| R:GTGGCTGTTGAGGGGTTG | ||||

| mCrCIR02B07 | AJ567403 | 9 | F:CAGCTCAACATGAAAGG | 50 |

| R:TTGGAGAACAGGATGG |

EMBL, accession number in the EMBL–EBI database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/).

PCR reactions were performed in 20 μl with 1× Taq buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.8 U Taq DNA polymerase, 0.5 ng/μl template DNA, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.4 μM forward primer, and 0.4 μM reverse primer in an AG Primus 96 plus thermocycler (MWG, Germany). The PCR program consisted of 5 min initial denaturation (94°C), followed by 40 cycles of 30 s denaturation (94°C), 1 min primer annealing (50 or 55°C depending on the primers, Table 1), and 45 s extension (72°C), and a final extension of 4 min (72°C). Fragment analysis and allele calling were done by capillary electrophoresis using the CEQ 8800 genetic analyzer and software (Beckman Coulter, CA, United States). As CHA is totally differentiated from the WLM + PON tetraploid parent, the diploid gamete genotypes were directly inferred from the triploid hybrid genotypes by removing the specific CHA alleles.

Centromeric SNP Development and Analysis

We have developed new SNP markers in centromeric region of the nine citrus chromosomes. “Pomeroy” trifoliate, “Willow leaf” mandarin and “Chandler” pummelo whole genome resequencing data (available, respectively, with SRX2442480, SRX372685, and SRX372688 SRA number in NCBI database) were mapped on the haploid clementine reference genome (Wu et al., 2014) using “BWA-MEM, v0.7.12-r1039” (Li and Durbin, 2010) and variant calling was performed with GATK (McKenna et al., 2010). To be able to infer the intergeneric gamete structure from the genotyping of the triploid issued from diploid Chandler diploid X (Willow Leaf + Pomeroy) tetraploid hybridizations, we selected SNPs homozygous for “Willow leaf” (AA), “Chandler” (AA), and “Pomeroy” (BB) in gene sequences of the identified centromeric/pericentromeric regions (Wu et al., 2014; Aleza et al., 2015). The genetic distances to the centromeres were inferred from available genetic mapping data (Ollitrault et al., 2012; Aleza et al., 2015) considering the flanking markers in the physical sequence (Wu et al., 2014). We were able to select efficient markers located at less than 1 cM for seven chromosomes, at less than 2 cM for chromosome 5 and less than 5cM for chromosome 8 (Table 2). The selected SNPs were analyzed with KASParTM Genotyping System (a competitive, allele-specific dual Förster resonance energy transfer–based assay). Primers were designed by LGC Genomics from the SNP locus flanking sequence (Supplementary Material 1). Detailed explanation on the specific conditions and reagents used can be found in Cuppen (2007). Identification of allele dosages in heterozygous triploid hybrids was carried out on the basis of relative allele signals, as described by Cuenca et al. (2013). For the nine SNP markers, the allelic configuration was as follow: “Chandler” (AA) × ”Flhorag1” (AABB) producing AAA, AAB, and ABB triploid progenies with direct inference of the “Flhorag1” diploid gametes (AA, AB, and BB, respectively).

Table 2.

Location of nine centromeric/pericentromeric SNP loci fully distinguishing “Pomeroy” poncirus from “willow leaf” mandarin and “Chandler” pummel.

| Marker | Scaffold | Position | SNP | Gene ID | D/Cent (cM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1_16582061 | 1 | 16582061 | [C/T] | Ciclev10007229m.g | <1 |

| P2_19903193 | 2 | 19903193 | [T/C] | Ciclev10014147m.g | <1 |

| P3_16287238 | 3 | 16287238 | [T/C] | Ciclev10024301m.g | <1 |

| P4_9505439 | 4 | 9505439 | [A/G] | Ciclev10031824m.g | <1 |

| P5_20142568 | 5 | 20142568 | [T/A] | Ciclev10000575m.g | <2 |

| P6_3130249 | 6 | 3130249 | [G/A] | Ciclev10011214m.g | <1 |

| P7_15458045 | 7 | 15458045 | [A/G] | Ciclev10025280m.g | <1 |

| P8_16631925 | 8 | 16631925 | [A/T] | Ciclev10030352m.g | <5 |

| P9_12062066 | 9 | 12062066 | [C/T] | Ciclev10006749m.g | <1 |

SNP positions, gene ID, and flanking position came from the haploid clementine reference sequence (Wu et al., 2014; https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html#!info?alias=Org_Cclementina).

Data Analysis

Pluri-allelic SSR markers: first we tested if the SSR allele frequencies observed in gametes deviated from those expected based on the parental genotypes (chi-square goodness-of-fit test), which would indicate the presence of null alleles or selection against particular alleles. Subsequently, we applied a likelihood based approach that simultaneously estimates two parameters: (1) τ – the proportion of gamete allelic constitutions that can be explained by random tetrasomic segregation and (2) β – the double reduction frequency relative to τ (Stift et al., 2008). This was done for each preferential pairing scenario (e.g., for a marker displaying the ABCD genotype for WLM + PON, we evaluated three pairing scenarios: A with B, C with D; A with C, B with D; A with D, B with C). For parameter estimation, we used the constrained non-linear regression (CNLR) function implemented in SPSS 15.0 (SPSS syntax file1). We then used a likelihood ratio test (LRT) evaluated against a compound distribution of (Self and Liang, 1987) to determine if the model with the estimated τ explained the data significantly better than a random null model (i.e., a model with strict tetrasomic segregation, τ = 1). For loci for which “Flhorag1” had less than four alleles, we considered the possibility of null alleles using a G-test for contingency tables to evaluate the most probable constitution. In case of three alleles, we compared abc0 and abcc (for parents of the somatic hybrid genotyped ab and cc), and in the case of two allele aabb, aab0, abb0, or ab00 (parents of the somatic hybrid aa and bb).

Di-allelic centromeric/pericentromeric SNP markers: for centromeric diallelic markers the segregation model for duplex tetraploid parents (AABB configuration) is greatly simplified because the double reduction effect can be missed and the segregation pattern is a direct function of τ. Therefore, for these markers τ was estimated by the maximum likelihood approach proposed by Aleza et al. (2016a).

Genetic dissimilarities between diploid gametes were estimated with the DARwin 6.0 software (Perrier and Jacquemoud-Collet, 2006) using the “simple matching” dissimilarity index using the pluriallelic SSRs markers to integrate intergeneric and intraspecific polymorphisms.

Results

Ploidy Level Determination

The cross between the diploid maternal parent (CHA) and the tetraploid somatic hybrid (“Flhorag1”) resulted in 63 fully developed seeds collected from 41 fruits, from which 59 plantlets germinated. Flow cytometry indicated that the plantlets were triploid, with one tetraploid exception (data not shown). Chromosome counts (Supplementary Material 2) confirmed the flow cytometry results. The segregation analyses were performed for the 58 triploid hybrids.

SSR Genotyping

For 15 out of the 19 SSRs markers, allele frequencies observed in the gametes did not significantly differ from expected frequencies based on the “Flhorag1” genotype, that is, there was no segregation distortion. This confirmed the correct determination of allele doses in the somatic hybrid and the absence of null alleles. For one marker (mCrCIR02F12), a scenario assuming the previously suspected presence of a null allele in the PON genome could explain the observed allele frequencies. Moreover, the “microsatellite DNA allele counting—peak ratios” (MAC-PR) method based on relative areas of the peaks of the different alleles provided additional evidence of a null allele at this locus.

At the three remaining loci (mCrCIR02D03, mCrCIR07C09, and mCrCIR03F05), the progeny allele frequencies were significantly distorted (P < 0.05) and remained so when scenarios were considered involving null alleles in either WLM or PON (Table 3). In addition, MAC-PR provided no evidence for null alleles at these loci. They were excluded from further analyses, so the segregation analyses were performed with 16 loci with Mendelian segregation. For these 16 SSR markers, the MAC-PR analysis of “Flhorag1” confirmed a full addition of parental (WLM and PON) alleles.

Table 3.

Distribution of inferred diploid gamete genotypes that produced CHA × (WLM + PON) progeny at the 19 studied loci.

| Locus | Linkage Group | Parental Genotypes |

Inferred Genotypes of Diploid Gametes | Allelic Distortion p Value | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WLM | PON | |||||||||||||||||

| Segregation with two or three different alleles | AA | AB | AC | BB | CC | BC | ||||||||||||

| CiBE5055 | 1 | BC | AA | 5 | 22 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.68 | ||||||||

| MEST431 | 1 | BB | AA | 5 | 46 | n.a. | 7 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.68 | ||||||||

| mCrCIR02D09 | 2 | AB | CC | 1 | 0 | 25 | 1 | 1 | 30 | 0.79 | ||||||||

| MEST46 | 2 | BB | AA | 2 | 56 | n.a. | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.71 | ||||||||

| mCrCIR02G12 | 3 | CC | AB | 2 | 3 | 25 | 1 | 0 | 27 | 0.54 | ||||||||

| mCrCIR02D04b | 4 | AA | BC | 5 | 28 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.66 | ||||||||

| mCrCIR03D12a | 4 | AA | BC | 1 | 28 | 24 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.66 | ||||||||

| mCrCIR07D06 | 4 | AB | CC | 0 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 6 | 26 | 0.54 | ||||||||

| mCrCIR03F05 | 4 | BB | AC | 2 | 27 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 17 | 0.02∗ | ||||||||

| mCrCIR01F08a | 5 | BB | AA | 3 | 50 | n.a | 5 | n.a | n.a | 0.71 | ||||||||

| mCrCIR07E12 | 5 | AC | BB | 0 | 26 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 25 | 0.79 | ||||||||

| mCrCIR02D03 | 7 | AB | AC | 1 | 5 | 28 | 1 | 1 | 22 | 1.14E-06∗ | ||||||||

| mCrCIR07E05 | 7 | BB | AA | 4 | 51 | n.a. | 3 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.85 | ||||||||

| mCrCIR02A09 | 8 | CC | AB | 1 | 1 | 28 | 0 | 2 | 26 | 0.87 | ||||||||

| mCrCIR07B05 | 8 | BB | AA | 1 | 55 | n.a. | 2 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.85 | ||||||||

| mCrCIR07C09 | 9 | AC | BC | 1 | 20 | 7 | 1 | 11 | 18 | 0.04∗ | ||||||||

| mCrCIR02B07 | 9 | AC | BB | 0 | 25 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 23 | 0.97 | ||||||||

| Segregation with four different alleles | AA | AB | AC | AD | BB | BC | BD | CC | CD | DD | ||||||||

| mCrCIR02G02 | 8 | AB | CD | 0 | 2 | 23 | 7 | 0 | 13 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.14 | ||||

| Segregation including a null allele | AA | AB | AC | A0 | BB | BC | B0 | CC | C0 | 00 | ||||||||

| mCrCIR02F12 | 6 | AB | C0 | 0 | 3 | 14 | 10 | 0 | 21 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.16 | ||||

WLM, Citrus reticulata cv Willowleaf mandarin; PON, Poncirus trifoliata cv Pomeroy; Flhorag1, Citrus reticulata cv Willowleaf mandarin + Poncirus trifoliata cv Pomeroy; A. B. C. D, allele length (A represents the longest allele); 0, null allele. For three of these loci, allelic distortion was observed (∗). Corresponding P values for allelic distortion are given.

SSR Inheritance in the Flhorag1 Tetraploid Somatic Hybrid

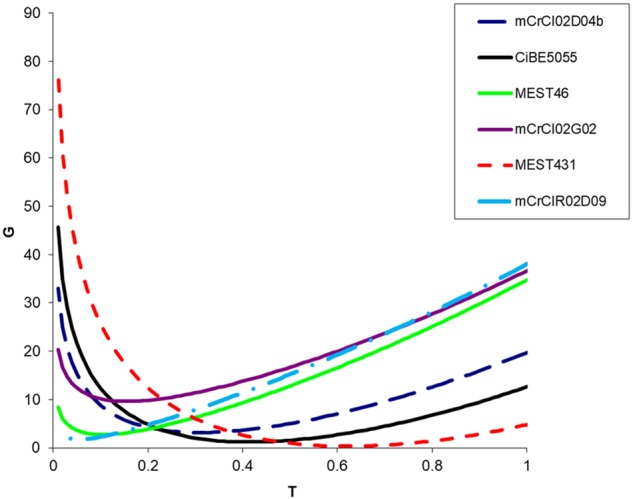

For all 16 analyzed loci, the estimated value of τ (proportion of gametes that can be explained by random meiotic chromosome associations) ranged from 0.07 to 0.58 (Figure 1 and Table 4). For each marker, fits between full tetrasomic inheritance model (τ = 1) and the best fitting intermediate model were compared. The LRT values were all highly significant, with p values ranging from 7.56E-09 to 1.78E-02 (Table 4). Preferential pairing was always between homologous chromosomes (between chromosomes derived from the same parental genome; i.e., mandarin or Poncirus).

FIGURE 1.

Example of deviance (G) for six observed SSR loci segregations in the “Flhorag1” somatic hybrid gametes with inheritance models ranging from τ = 0 (full disomic) to τ = 1 (full tetrasomic). Among the 16 analyzed SSRs markers Mest431 and mCrCIR02D09 display, respectively, the higher (0.58) and lower (0.07) τ values.

Table 4.

Fitting the inheritance model and intraparental and interparental heterozygosity rates on the segregation of 16 SSR loci in the “Flhorag1” diploid gametes.

| SSR | LG | WLM | PON | Pref Pairing | Best model |

% Heterozygosity |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | τ | LRT | p value | Intra-specific | Inter-generic | |||||

| CiBE5055 | 1 | BC | AA | BC/AA | – | 0.41 | 5.79 | 8.04E-03 | 5% | 86% |

| MEST431 | 1 | AA | BB | AA/BB | – | 0.58 | 4.41 | 1.78E-02 | 0% | 79% |

| mCrCIR02D09 | 2 | AB | CC | AB/CC | 0.07 | 0.07 | 20.03 | 4.00E-06 | 2% | 95% |

| MEST46 | 2 | BB | AA | AA/BB | – | 0.1 | 32.04 | 7.56E-09 | 0% | 97% |

| mCrCIR02G12 | 3 | CC | AB | CC/AB | 0.05 | 0.21 | 12.74 | 1.79E-04 | 5% | 90% |

| mCrCIR02D04b | 4 | AA | BC | AA/BC | – | 0.31 | 8.39 | 1.89E-03 | 2% | 90% |

| mCrCIR03D12a | 4 | AA | BC | AA/BC | 0.04 | 0.23 | 11.42 | 3.64E-04 | 5% | 90% |

| mCrCIR07D06 | 4 | AB | CC | AB/CC | – | 0.31 | 8.39 | 1.89E-03 | 0% | 90% |

| mCrCIR01F08a | 5 | BB | AA | AA/BB | – | 0.41 | 11.45 | 3.57E-04 | 0% | 86% |

| mCrCIR07E12 | 5 | AC | BB | AC/BB | – | 0.36 | 7.01 | 4.06E-03 | 9% | 88% |

| mCrCIR02F12 | 6 | AB | C0 | AB/C0 | – | 0.21 | 11.73 | 3.07E-04 | 7% | 93% |

| mCrCIR07E05 | 7 | BB | AA | AA/BB | – | 0.36 | 13.86 | 9.90E-05 | 0% | 88% |

| mCrCIR02A09 | 8 | CC | AB | CC/AB | 0.03 | 0.14 | 14.19 | 8.20E-05 | 2% | 93% |

| mCrCIR07B05 | 8 | BB | AA | AA/BB | – | 0.16 | 27.26 | 8.88E-08 | 0% | 95% |

| mCrCIR02G02 | 8 | AB | CD | AB/CD | – | 0.16 | 13.79 | 1.02E-04 | 5% | 95% |

| mCrCIR02B07 | 9 | AC | BB | AC/BB | 0.07 | 0.38 | 6.34 | 5.89E-03 | 5% | 83% |

Comparisons of fit were performed between the tetrasomic null model and the best fitting intermediate model. LRT values were evaluated as described in the Materials and methods and were significant at the indicated level. WLM, Citrus reticulata cv Willowleaf mandarin; PON, Poncirus trifoliata cv Pomeroy; A. B. C. D, allele length (A represents the longest allele); 0, null allele.

The double reduction rate could only be estimated at 10 loci. Indeed, for MEST046, MEST431, mCrCIR01F08a, mCrCIR07B05, and mCrCIR07E05 markers, WLM and PON were both homozygous with a double homoduplex conformation (AA, BB). For the mCrCIR02F12 locus, null alleles prevented double reduction gamete identification. Double reduction was detected for five loci (mCrCIR02D09, mCrCIR02G12, mCrCIR03D12a, mCrCIR02A09, and mCrCIR 02B07) with β estimates ranging from 0.03 to 0.07 (Table 4).

SNP Inheritance in the Flhorag1 Tetraploid Somatic Hybrid

For each SNP locus, “Flhorag1” was heterozygous with equilibrated allelic doses (AABB). No allelic distortion was observed for the nine diallelic SNPs. They revealed similar intergeneric heterozygosity restitution and τ values than the ones estimated on the same LGs with SSRs (Table 5). Intergeneric heterozygosity varied between 86% in LGs 1 and 9 to 97% in LG 2. In accordance, the lower τ value (0.11) was inferred for LG2 and the higher (0.42) for LG1 and LG9.

Table 5.

Fitting the inheritance model and intergeneric heterozygosity rates on the segregation of nine centromeric SNP loci in the “Flhorag1” diploid gametes.

| Parental Genotypes | Diploid Gametes | Allelic Distortion p value | τ | Intergeneric Heterozygosity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotypes |

||||||||||

| LG | WLM | PON | Flhorag1 | AA | AB | BB | ||||

| P1_16582061 | 1 | AA | BB | AABB | 5 | 50 | 3 | 0.71 | 0.42 | 86% |

| P2_19903193 | 2 | AA | BB | AABB | 1 | 56 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.11 | 97% |

| P3_16287238 | 3 | AA | BB | AABB | 3 | 54 | 1 | 0.71 | 0.21 | 93% |

| P4_9505439 | 4 | AA | BB | AABB | 4 | 52 | 2 | 0.71 | 0.31 | 90% |

| P5_20142568 | 5 | AA | BB | AABB | 2 | 52 | 4 | 0.71 | 0.31 | 90% |

| P6_3130249 | 6 | AA | BB | AABB | 2 | 55 | 1 | 0.85 | 0.16 | 95% |

| P7_15458045 | 7 | AA | BB | AABB | 2 | 52 | 4 | 0.71 | 0.31 | 90% |

| P8_16631925 | 8 | AA | BB | AABB | 1 | 55 | 2 | 0.85 | 0.16 | 95% |

| P9_12062066 | 9 | AA | BB | AABB | 5 | 50 | 3 | 0.71 | 0.42 | 86% |

Distribution of τ Variations of SSR and SNP Loci Among the Different LGs

Loci belonging to the same linkage group (LG) tended to have similar τ values with significant differences between LGs. LG1 (CiBE5055, MEST431, P1_16582061; τ = 0.47 ± 0.09); LG2 (mCrCIR02D09, MEST046, P2_19903193; τ = 0.09 ± 0.02); LG3 (mCrCIR02G12, P3_16287238; τ = 0.21 ± 0.00); LG4 (mCrCIR02D04b, mCrCIR03D12a, mCrCIR07D06, P4_9505439; τ = 0.29 ± 0.03); LG5 (mCrCIR01F08a, mCrCIR07E12, P5_20142568; τ = 0.36 ± 0.05); LG6 (mCrCIR02F12; P6_3130249; τ = 0.18 ± 0.04); LG7 (mCrCIR07E05; P7_15458045; τ = 0.34 ± 0.03); LG8 (mCrCIR02A09, mCrCIR07B05, mCrCIR02G02, P8_16631925; τ = 0.15 ± 0.01); LG9 (mCrCIR02B07, P9_12062066; τ = 0.40 ± 0.02. Therefore, we can consider that LG1 has an intermediary inheritance while the other LGs had a preferential disomic tendency highly marked for LG2 and LG8.

Heterozygosity Transmission and Gamete Diversity

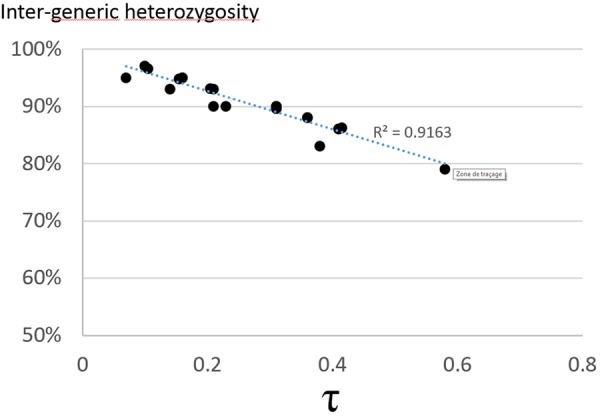

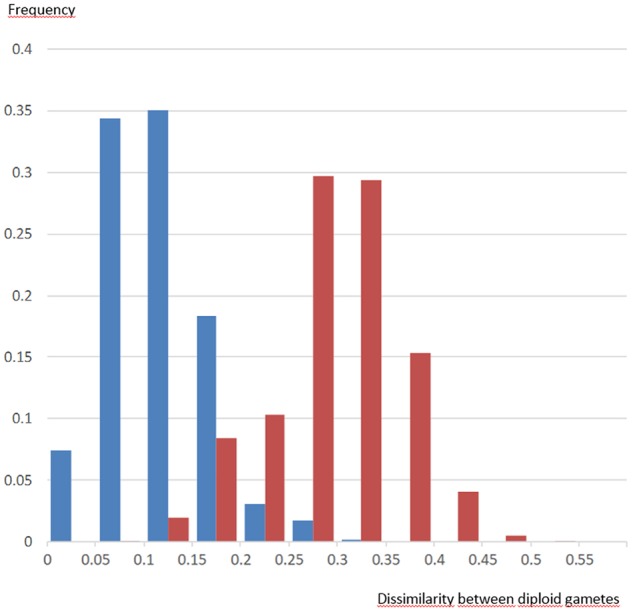

Diploid gametes from this tetraploid intergeneric somatic hybrid transmitted both intraspecific and intergeneric heterozygosity. The intergeneric heterozygosity transmission rate was directly linked with τ, and decreased linearly from 97 to 79% with increasing τ values (Figure 2). When analyzing the multilocus gametic structure over the 25 loci with complete allelic differentiation between Citrus and Poncirus, we found five diploid gametes (among the 58 analyzed) with complete intergeneric heterozygosity (Supplementary Material 3). The average intergeneric and intrageneric heterozygosity transmission were, respectively, 90.3 and 4.1%. Intergeneric recombinations were detected from multiloci pattern within each LG (Supplementary Material 3), whose frequencies (0.29, 0.09, 0.14, 0.24, 0.26, 0.10, 0.16, 0.14, 0.26 in LGs 1 to 9, respectively) were significantly related (R2 = 0.82) with the τ average values by LGs. We compared the distribution of dissimilarities between gametes considering all SSR alleles (intraspecific and intergeneric diversity) or solely the intergeneric origin of alleles (i.e., only two alleles considered: a poncirus allele P and a mandarin allele M and therefore segregation between PP, MM, and PM genotypes). Preferential pairing and consecutive predominant intergeneric heterozygosity transmission resulted in a relatively low intergeneric diversity contribution and gamete genetic diversity seemed to be mainly due to parental intraspecific diversity segregation (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Correlation between the intergeneric heterozygosity transmission rate and the τ value for the 16 SSR and 9 SNP markers.

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of genetic dissimilarities between diploid gametes of the Flhorag1 somatic hybrid based on intergeneric segregation (blue) and all allele segregation (red).

Discussion

Intermediate Inheritance With a Preferential Disomic Trend Detected in the C. reticulata + P. trifoliata (Flhorag1) Intergeneric Tetraploid Somatic Hybrid

All 16 SSR and 9 SNP markers studied displayed intermediate inheritance with a preferential disomic tendency. The gamete proportions explained by random meiotic chromosome association (τ) ranged from 7 to 58%, and for all markers preferential pairing occurred between chromosomes derived from the same parent (i.e., WLM or PON). Such intermediate inheritance with a disomic tendency was also described for a doubled-diploid “Mexican lime” (Rouiss et al., 2018) belonging to C. x aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle, a species of interspecific origin (C. micrantha Wester x C. medica L.; Nicolosi et al., 2000; Curk et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2018). The levels of preferential pairing revealed for “Flhorag1” and the doubled-diploid “Mexican lime” are much higher than that observed for (i) an interspecific somatic hybrid (C. reticulata + C. lemon) within the Citrus genus, where random tetrasomic inheritance (τ = 1) could only be rejected for 8 out of 17 markers, with τ ranging from 0.24 to 0.95 (Kamiri, et al. 2011), and (ii) a doubled-diploid clementine displaying tetrasomic segregation for five chromosomes, intermediate segregation with a tetrasomic tendency for three chromosomes and intermediate segregation with a disomic tendency for only one chromosome (Aleza et al., 2016a). Preferential pairing variations between tetraploid citrus reveal different levels of divergence between their constitutive genomes.

Cytogenetic study of meiosis behavior is another approach to analyze chromosome affinity in polyploids. Indeed, tetravalent formation testifies for chromosome homology between parents while they should be precluded in wide allotetraploids (assuming the absence of large structural variation). Few cytogenetic studies were performed in tetraploid somatic hybrids and most concerned interspecific hybrids within the Citrus genus. Del Bosco et al. (1999) were the first to report the microsporogenesis in a Citrus interspecific tetraploid somatic hybrid between “Valencia” sweet orange and “Femminello” lemon. They observed frequent tetravalents. One of these tetravalents by meiotic cell was related to a reciprocal translocation in sweet-orange but the additional tetravalents were considered as a consequence of intergenomic pairing. Similar observation for frequent tetravalents were reported for “Hamlin” sweet orange + “Rough” Lemon and “Key” lime + “Valencia” sweet orange (Chen et al., 2004) and “Willow leaf” mandarin + “Eureka” lemon (Kamiri et al., 2011). For the last somatic hybrid, this cytogenetic observation was associated with preferential tetrasomic inheritance of molecular markers. However, as previously mentioned, reciprocal or inverted translocations can result in tetravalent formation even in diploid parents as observed in “Valencia” sweet orange (Del Bosco et al., 1999) or Mexican lime (Rouiss et al., 2018). Therefore, cytogenetic observations should be associated with marker segregation analysis for a full understanding of tetraploid meiosis behavior. In the case of mandarin + poncirus somatic hybrids, the predominant preferential pairing between homologous chromosomes inferred in “Flhorag1” from molecular marker segregation data is in agreement with the previous cytogenetic study conducted in an intergeneric citrus somatic hybrid between “Cleopatra” mandarin and “Argentine” poncirus (unpublished results mentioned in Chen et al., 2004). Indeed, they observed a high percentage of bivalents, suggesting low chromosome homology between the fusion parents.

Recent whole nuclear genome resequencing data revealed an important differentiation of Poncirus trifoliata from the Citrus species clade (Wu et al., 2018). This genomic differentiation level is in line with the preferential disomic inheritance observed for our C. reticulata + P. trifoliata intergeneric somatic hybrid. Interestingly, our finding that preferential pairing was not complete (i.e., inheritance is not fully disomic and intergeneric recombinations are observed in our study), indicated that the remaining homology is still enough to allow Citrus and Poncirus chromosome pairing, and helps understand the long-known intergeneric sexual compatibility at the diploid level (Cameron and Garber, 1968). Moreover, comparative studies of Citrus and Poncirus genetic maps revealed a high level of synteny and collinearity of markers. From unsaturated maps, Chen et al. (2008) observed only a few inversions between shared loci. Bernet et al. (2010) reported high collinearity between Fortune “mandarin” and Poncirus trifoliata. More recently, the availability of reference whole genome sequence allowed to compare genetic and physical maps and globally confirmed the good conservation of marker order between P. trifoliata and “Sunki” mandarin (Curtolo et al., 2018) and P. trifoliata and sweet orange (Huang et al., 2018).

Although inheritance was consistently intermediate between disomic and tetrasomic for all markers, there was considerable variation in the degree of preferential pairing. Such variation among loci is common, and has for example been observed in autotetraploid Pacific oysters (Curole and Hedgecock, 2005) and sugarcane (Jannoo et al., 2004). Variation among markers could merely reflect stochasticity, but also true differences in homology for different parts of the genome. Significant differences of the τ values were observed between LGs. LG1 displayed the higher value of random association (close to 50%) while the other LGs had a preferential disomic tendency. Disomy was very high for LG2 and LG8 with more than 85% of preferential chromosome pairing. Although an analysis of more markers would be needed to confirm the pattern, our results suggest that the divergence between “Willow leaf” mandarin and “Pomeroy” poncirus varies between chromosomes.

Double Reduction Rates and Heterozygosity Transmission

Gametes resulting from double reduction have been detected in five loci. Double reduction implies multivalent formation and a crossover between the considered locus and its centromere with further adjacent segregation (Haynes and Douches, 1993). It results in increased homozygosity and its maximum frequency (1/6) is reached in case of systematic quadrivalent formation at meiosis (Stift et al., 2008). Our progeny sample size was not enough for accurate estimation of the double reduction rate but highlighted the possibility of tetravalent formation in the intergeneric somatic hybrid.

The diploid gametes produced by tetraploid somatic hybrids are highly heterozygous. Under tetrasomic inheritance, they should transmit either intraparental or interparental heterozygosity (Ollitrault et al., 2008), in contrast to strict disomic inheritance, which leads to exclusive transmission of interparental heterozygosity for wide interspecific somatic hybrids. When inheritance is intermediate, as found in the intergeneric Citrus-Poncirus Flhorag1 somatic hybrid, transmission of intraspecific and intergeneric heterozygosity depends on the degree of preferential chromosome pairing and the double reduction rates in case of tetravalent formation. As no double reduction is possible in centromeric areas, they should display higher intergeneric restitution values. Assuming preferential pairing between parental homologous chromosomes, interparental heterozygosity transmission decreases with increasing τ values. Therefore, it is logical that the interparental heterozygosity transmission (in this case intergeneric heterozygosity) observed in the intergeneric Flhorag1 somatic hybrid (90%) was much higher than the 64.1% observed for a C. reticulata + C. lemon interspecific somatic hybrid (Kamiri et al., 2011). As a consequence of this high level of intergeneric heterozygosity inheritance, the genetic diversity of the gamete population results mainly from parental intraspecific diversity segregation. However, these conclusions for genetic markers should not be extrapolated for phenotypic traits because phenotypic differentiation at the intergeneric level is very high compared with the intra-poncirus or mandarin variability.

Implications for Breeding

Citrus breeding is hampered by complex genome structures, features of reproductive biology and the long juvenile phase, but can take advantage of vegetative propagation including apomictic seeds for rootstock multiplication, allowing clonal propagation of elite genotypes whatever its genome complexity (Ollitrault and Navarro, 2012). Therefore, breeding strategies are generally based on one (or very few) cycle of variability induction followed by direct selection of cultivars or rootstock. In such context, it is essential to optimize the transfer to the progenies, of the genetic gains obtained by phenotypic selection at the parental level. In case of Citrus-Poncirus intergeneric polyploid breeding, most of the genetic value comes from the combination of favorable traits from Citrus (tolerance to abiotic stresses such as salinity, water deficit, calcareous soils) and Poncirus (resistance/tolerance to diseases and pests such as tristeza virus, Phytophthora, nematodes; cold tolerance). It is based on dominant inheritance in highly intergeneric heterozygous structures. For further breeding using these intergeneric tetraploids as sexual parents (tetrazyg strategy; Grosser and Gmitter, 2010), it is therefore essential to transmit a large part of the parental intergeneric heterozygosity to the progenies in order to prevent overall breakage of the favorable complex multilocus genotypic structure selected at the allotetraploid parental level. From this work, it appears that the differentiation between C. reticulata and Poncirus trifoliata genomes results in preferential homologous pairing and predominantly intergeneric heterozygosity transmission. Most of the value of the somatic hybrid should thus be transmitted to its progeny. Moreover, the infrequent occurrence of non-homologous chromosome pairing offers an opportunity for intergeneric recombination, and the generation of novel allelic combinations. Several Citrus × Poncirus diploid intergeneric hybrids such as citrumello (C. paradisi × P. trifoliata), citrange (C. sinensis × P. trifoliata), and citrandarin (C. reticulata × P. trifoliata) proved their interest as rootstock and are widely used worldwide. Taking advantage of spontaneous chromosome doubling in nuclear cells, doubled diploid lines were selected for most of them (Aleza et al., 2011). If they display similar preferential disomic tendency than the “Flhorag1” somatic hybrid, they should produce gametes in which a very high proportion of the genome of the initial diploid intergeneric hybrid has been transferred. Thus, the high phenotypic value deeply selected at the diploid intergeneric parent level should have a very marked positive impact on the products of the “Tetrazyg” strategy when using these doubled-diploid parents.

Author Contributions

PO, YF, and TK designed the experiment. DD created and provided the parental somatic hybrids the parental somatic hybrid. MK and GC performed the SSRs analysis. MK and MS analyzed the results. MK, MS, YF, and PO wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. The Domaines Abbes Kabbage, Agadir (Morocco), and the Comité Mixte Inter Universitaire Franco-Marocain (Program Volubils, MA/08/196) funded a grant awarded to MK. This study was also supported by the Collectivité Territoriale de Corse (CTC), “Sélection de Porte-Greffe pour le Développement d’une Agrumiculture Durable” ARR-15-05332 and ARR-17001001.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.01557/full#supplementary-material

References

- Adams K. L., Wendel J. F. (2005). Polyploidy and genome evolution in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 8 135–141. 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleza P., Cuenca J., Hernandez M., Juarez J., Navarro L., Ollitrault P. (2015). Genetic mapping of centromeres in the nine Citrus clementina chromosomes using half-tetrad analysis and recombination patterns in unreduced and haploid gametes. BMC Plant Biol. 15:80. 10.1186/s12870-015-0464-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleza P., Cuenca J., Juárez J., Navarro L., Ollitrault P. (2016a). Inheritance in doubled-diploid clementine and comparative study with SDR unreduced gametes of diploid clementine. Plant Cell Rep. 35 1573–1586. 10.1007/s00299-016-1972-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleza P., Froelicher Y., Schwarz S., Agustí M., Hernández M., Juárez J., et al. (2011). Tetraploidization events by chromosome doubling of nucellar cells are frequent in apomictic citrus and are dependent on genotype and environment. Ann. Bot. 108 37–50. 10.1093/aob/mcr099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleza P., Garcia-Lor A., Juárez J. (2016b). Recovery of citrus cybrid plants with diverse mitochondrial and chloroplastic genome combinations by protoplast fusion followed by in vitro shoot, root, or embryo micrografting. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 126 205–217. 10.1007/s11240-016-0991-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aleza P., Juárez J., Ollitrault P., Navarro L. (2009). Production of tetraploid plants of non-apomictic citrus genotypes. Plant Cell Rep. 28 1837–1846. 10.1007/s00299-009-0783-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allario T., Brumos J., Colmenero-Flores J. M., Iglesias D. J., Pina J. A., Navarro L., et al. (2013). Tetraploid Rangpur lime rootstock increases drought tolerance via enhanced constitutive root abscisic acid production. Plant Cell Environ. 36 856–868. 10.1111/pce.12021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allendorf F. W., Danzmann R. G. (1997). Secondary tetrasomic segregation of MDH-B and preferential pairing of homeologues in rainbow trout. Genetics 145 1083–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley N. A., Roose M. L., Krueger R. R., Federici C. T. (2006). Assessing genetic diversity and population structure in a citrus germplasm collection utilizing simple sequence repeat markers (SSRs). Theor. Appl. Genet. 112 1519–1531. 10.1007/s00122-006-0255-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone A., Li J., Sebastiano A., Cardi T., Frusciante L. (2002). Evidence for tetrasomic inheritance in a tetraploid Solanum commersonii (+) S. tuberosum somatic hybrid through the use of molecular markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 104 539–546. 10.1007/s00122-001-0792-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernet G. P., Fernandez Ribacoba J., Carbonell E. A., Asins M. J. (2010). Comparative genome-wide segregation analysis and map construction using a reciprocal cross design to facilitate citrus germplasm utilization. Mol. Breed. 25 659–673. 10.1007/s11032-009-9363-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bousalem M., Arnau G., Hochu I., Arnolin R., Viader V., Santoni S., et al. (2006). Microsatellite segregation analysis and cytogenetic evidence for tetrasomic inheritance in the American yam Dioscorea trifida and a new basic chromosome number in the Dioscoreae. Theor. Appl. Genet. 113 439–451. 10.1007/s00122-006-0309-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J. W., Garber M. J. (1968). Identical-twin hybrids of Citrus x Poncirus from strictly sexual seed parents. Am. J. Bot. 55 199–205. 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1968.tb06962.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell-Caballero J., Alonso R., Ibañez V., Terol J., Talon M., Dopazo J. A. (2015). Phylogenetic analysis of 34 chloroplast genomes elucidates the relationships between wild and domestic species within the genus Citrus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32 2015–2035. 10.1093/molbev/msv082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. L., Guo W. W., Yi H. L., Deng X. X. (2004). Cytogenetic analysis of two interspecific citrus allotetraploid somatic hybrids and their diploid fusion parents. Plant Breed. 123 332–337. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2004.00972.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Bowman K. D., Choi Y. A., Dang P. M., Rao M. N., Huang S., et al. (2008). EST-SSR genetic maps for Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata. Tree Genet. Genomes 4 1–10. 10.1007/s11295-007-0083-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca J., Aleza P., Navarro L., Ollitrault P. (2013). Assignment of SNP allelic configuration in polyploids using competitive allele-specific PCR: application to citrus triploid progeny. Ann. Bot. 111 731–742. 10.1093/aob/mct032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuppen E. (2007). Genotyping by allele-specific amplification (KASPar). CSH Protoc. 2007:4841. 10.1101/pdb.prot4841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curk F., Ollitrault F., Garcia-Lor A., Luro F., Navarro L., Ollitrault P. (2016). Phylogenetic origin of limes and lemons revealed by cytoplasmic and nuclear markers. Ann. Bot. 117 565–583. 10.1093/aob/mcw005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curole J. P., Hedgecock D. (2005). Estimation of preferential pairing rates in second-generation autotetraploid pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas). Genetics 171 855–859. 10.1534/genetics.105.043042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtolo M., Soratto T. A. T., Gazaffi R., Takita M. A., Machado M. A., Cristofani-Yaly M. (2018). High-density linkage maps for Citrus sunki and Poncirus trifoliata using DArTseq markers. Tree Genet. Genomes 14:5 10.1007/s11295-017-1218-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dambier D., Benyahia H., Pensabene-Bellavia G., Aka K., Froelicher Y., Belfalah Z., et al. (2011). Somatic hybridization for Citrus rootstock breeding: an effective tool to solve some important issues of the Mediterranean citrus industry. Plant Cell Rep. 30 883–900. 10.1007/s00299-010-1000-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Bosco S. F., Tusa N., Conicella C. (1999). Microsporogenesis in a Citrus interspecific tetraploid somatic hybrid and its fusion parents. Heredity 83 373–377. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6885770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Hont A., Grivet L., Feldmann P., Rao S., Berding N., Glaszmann J. C. (1996). Characterisation of the double genome structure of modern sugarcane cultivars (Saccharum spp.) by molecular cytogenetics. Mol. Gen. Genet. 250 405–413. 10.1007/BF02174028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra de Souza J., de Andrade Silva E. M., Coelho Filho M. A., Morillon R., Bonatto D., Micheli F., et al. (2017). Different adaptation strategies of two citrus scion/rootstock combinations in response to drought stress. PLoS One 12:e0177993. 10.1371/journal.pone.0177993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froelicher Y., Dambier D., Bassene J. B., Costantino G., Lotfy S., Didout C., et al. (2008). Characterization of microsatellite markers in mandarin orange (Citrus reticulata Blanco). Mol. Ecol. Resour. 8 119–122. 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01893.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawel N. J., Jarret R. L. (1991). A modified CTAB DNA extraction procedure for Musa and Ipomoea. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 9 374–380. 10.1007/BF02672076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grosser J., Gmitter F. (2010). Protoplast fusion for production of tetraploids and triploids: applications for scion and rootstock breeding in citrus. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 104 343–357. 10.1007/s11240-010-9823-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grosser J. W., Barthe G. A., Castle B., Gmitter F. G., Jr., Lee O. (2015). The development of improved tetraploid citrus rootstocks to facilitate advanced production systems and sustainable citriculture in Florida. Acta Hortic. 1065 319–327. 10.17660/ActaHortic.2015.1065.38 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grosser J. W., Chandler J. L. (2000). Somatic hybridization of high yield, cold-hardy and disease resistant parents for citrus rootstock improvement. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 75 641–644. 10.1080/14620316.2000.11511300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grosser J. W., Ollitrault P., Olivares-Fuster O. (2000). Somatic hybridization in citrus: an effective tool to facilitate variety improvement. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 36 434–439. 10.1007/s11627-000-0080-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra D., Schifino-Wittmann M. T., Schwarz S. F., Weiler R. L., Dahmer N., Dutra Souza P. V. (2016). Tetraploidization in citrus rootstocks: effect of genetic constitution and environment in chromosome duplication. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 16 35–41. 10.1590/1984-70332016v16n1a6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W. W., Wu R. C., Cheng Y. J., Deng X. X. (2007). Production and molecular characterization of Citrus intergeneric somatic hybrids between red tangerine and citrange. Plant Breed. 126 72–76. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2006.01315.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harlan J. R., deWet J. M. (1975). On O. Winge and a prayer: the origins of polyploidy. Bot. Rev. 41 361–390. 10.1007/BF02860830 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes K. G., Douches D. S. (1993). Estimation of the coefficient of double reduction in the cultivated tetraploid potato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 85 857–862. 10.1007/BF00225029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero R., Asins M. J., Pina J. A., Carbonell E. A., Navarro L. (1996). Genetic diversity in the orange subfamily Aurantioideae. II. Genetic relationships among genera and species. Theor. Appl. Genet. 93 1327–1334. 10.1007/BF00223466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M., Roose M., Yu Q., Du D., Zhang Y., Deng Z., et al. (2018). Construction of high-density genetic maps and detection of QTLs associated with Huanglongbing infection in citrus. bioRxiv [Preprint] 10.1101/330753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannoo N., Grivet L., David J., D’Hont A., Glaszmann J. C. (2004). Differential chromosome pairing affinities at meiosis in polyploid sugarcane revealed by molecular markers. Heredity 93 460–467. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeridi M., Perrier X., Rodier-Goud M., Ferchichi A., D’Hont A., Bakry F. (2012). Cytogenetic evidence of mixed disomic and polysomic inheritance in an allotetraploid AABB Musa genotype. Ann. Bot. 1108 1593–1606. 10.1093/aob/mcs220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiri M., Stift M., Srairi I., Costantino G., El Moussadik A., Hmyene A., et al. (2011). Evidence for non-disomic inheritance in a Citrus interspecific tetraploid somatic between C. reticulata and C. lemon hybrid using SSR markers and cytogenetic analysis. Plant Cell Rep. 30 1415–1425. 10.1007/s00299-011-1050-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landergott U., Naciri Y., Schneller J. J., Holderegger R. (2006). Allelic configuration and polysomic inheritance of highly variable microsatellites in tetraploid gynodioecious Thymus praecox agg. Theor. Appl. Genet. 113 453–465. 10.1007/s00122-006-0310-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R. (2010). Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26 589–595. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luro F., Costantino G., Terol J., Argout X., Allario T., Wincker P., et al. (2008). Transferability of the EST-SSRs developed on Nules clementine(Citrus clementina Hort ex Tan) to other Citrus species and their effectiveness for genetic mapping. BMC Genomics 9:287. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A., Hanna M., Banks E., Sivachenko A., Cibulskis K., Kernytsky A., et al. (2010). The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20 1297–1303. 10.1101/gr.107524.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouhaya W., Allario T., Brumos J., Andrés F., Froelicher Y., Luro F., et al. (2010). Sensitivity to high salinity in tetraploid citrus seedlings increases with water availability and correlates with expression of candidate genes. Funct. Plant Biol. 37 674–685. 10.1071/FP10035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T., Tucker D. P. H. (1969). Growth factor requirements of tissue culture. Proc. First Int. Citrus Symp. 3 1155–1161. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolosi E., Deng Z. N., Gentile A., Malfa La S., Continella G., Tribulato E. (2000). Citrus phylogeny and genetic origin of important species as investigated by molecular markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 100 1155–1166. 10.1007/s001220051419 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira T. M., Ben Yahmed J., Dutra J., Maserti B. E., Talon M., Navarro L., et al. (2017). Better tolerance to water deficit in doubled diploid ‘Carrizo citrange’ compared to diploid seedlings is associated with more limited water consumption and better H2O2 scavenging. Acta Physiol. Plant. 39:e204 10.1007/s11738-017-2497-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ollitrault F., Terol J., Pina J. A., Navarro L., Talon M., Ollitrault P. (2010). Development of SSRs markers from Citrus clementina (Rutaceae) BAC end sequences and interspecific transferability in Citrus. Am. J. Bot. 97 124–129. 10.3732/ajb.1000280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollitrault P., Dambier D., Allent V., Luro F., Jacquemond C. (1996). “In vitro rescue and selection of spontaneous triploids by flow cytometry for easy peeler Citrus breeding,” in Proceedings of the Eighth International Citrus Congress International Society of Citriculture Vol. 2 Sun City: 913–917. [Google Scholar]

- Ollitrault P., Dambier D., Froelicher Y., Bakry F., Aubert B. (1998). Rootstock breeding strategies for the Mediterranean citrus industry: the somatic hybridization potential. Fruits 53 335–344. [Google Scholar]

- Ollitrault P., Dambier D., Luro F., Froelicher Y. (2008). “Ploidy manipulation for breeding seedless triploid citrus,” in Plant Breeding Reviews Vol. 30 ed. Janick J. (Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley; ) 323–352. [Google Scholar]

- Ollitrault P., Froelicher Y., Dambier D., Seker M. (2000). “Rootstock breeding by somatic hybridization for the Mediterranean citrus industry,” in Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Citrus Biotechnology Eilat: 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ollitrault P., Guo W., Grosser J. W. (2007). “Somatic hybridization,” in Citrus Genetics, Breeding and Biotechnology ed. Khan I. A. (Wallingford: CAB International; ) 235–260. 10.1079/9780851990194.0235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ollitrault P., Jacquemond C., Dubois C., Luro F. (2003). “Citrus,” in Genetic Diversity of Cultivated Tropical Plants eds Hamon P., Seguin M., Perrier X., Glaszmann J.-C. (Montpellier: CIRAD; ) 193–217. [Google Scholar]

- Ollitrault P., Navarro L. (2012). “Citrus,” in Fruit Breeding eds Badenes M. L., Byrne D. H. (New York, NY: Springer; ) 623–662. 10.1007/978-1-4419-0763-9_16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ollitrault P., Terol J. F., Chen C., Federici C. T., Lotfy S., Hippolyte I., et al. (2012). A reference genetic map of C. clementina hort. ex Tan.; citrus evolution inferences from comparative mapping. BMC Genomics 13:593. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oustric J., Morillon R., Luro F., Herbette S., Lourkistia R., Giannettini J., et al. (2017). Tetraploid Carrizo citrange rootstock (Citrus sinensis Osb. × Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.) enhances natural chilling stress tolerance of common clementine (Citrus clementina Hort. ex Tan). J. Plant Physiol. 214 108–115. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oustric J., Morillon R., Ollitrault P., Herbette S., Luro F., Froelicher Y., et al. (2018). Somatic hybridization between diploid Poncirus and Citrus improves natural chilling and light stress tolerances compared with equivalent doubled-diploid genotypes. Trees 32 883–895. 10.1007/s00468-018-1682-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pairon M. C., Jacquemart A. L. (2005). Disomic segregation of microsatellites in the tetraploid Prunus serotina Ehrh. (Rosaceae). J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 130 729–734. [Google Scholar]

- Perrier X., Jacquemoud-Collet J. P. (2006). DARwin Software. Available at: http://darwin.cirad.fr/darwin [Google Scholar]

- Podda A., Checcucci G., Mouhaya W., Centeno D., Rofidal V., Del Carratore R., et al. (2013). Salt-stress induced changes in the leaf proteome of diploid and tetraploid mandarins with contrasting Na(+) and Cl(-) accumulation behaviour. J. Plant Physiol. 170 1101–1112. 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey J., Schemske D. W. (1998). Pathways, mechanisms, and rates of polyploid formation in flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 29 467–501. 10.1104/pp.16.01768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey J., Schemske D. W. (2002). Neopolyploidy in flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 33 589–639. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.010802.150437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rouiss H., Bakry F., Froelicher Y., Navarro L., Aleza P., Ollitrault P. (2018). Origin of C. latifolia and C. aurantiifolia triploid limes: the preferential disomic inheritance of doubled-diploid ’Mexican’ lime is consistent with an interploid hybridization hypothesis. Ann. Bot. 121 571–585. 10.1093/aob/mcx179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz M., Pensabene-Bellavia G., Quinones A., Garcia-Lor A., Morillon R., Ollitrault P., et al. (2018). Molecular characterization and stress tolerance evaluation of new allotetraploid somatic hybrids between carrizo citrange and Citrus macrophylla W. rootstocks. Front. Plant Sci. 9:901. 10.3389/fpls.2018.00901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Russell D. W. (eds) (2006). “Fluorometric quantitation of DNA using hoechst 33258,” in The Condensed Protocols from Molecular Cloning: a Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; ) 742–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self S. G., Liang K. Y. (1987). Asymptotic properties of maximum likelihood estimators and likelihood ratio tests under nonstandard conditions. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 82 605–610. 10.1080/01621459.1987.10478472 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis D. E., Albert V. A., Leebens-Mack J., Bell C. D., Paterson A. H., Zheng C., et al. (2009). Polyploidy and angiosperm diversification. J. Bot. 96 336–348. 10.3732/ajb.0800079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis P. S., Soltis D. E. (2000). The role of genetic and genomic attributes in the success of polyploids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 7051–7057. 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel-Roy P., Goldschmidt E. E. (1996). Biology of Citrus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 10.1017/CBO9780511600548 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins G. (1947). Types of polyploids: their classification and significance. Adv. Genet. 1 403–429. 10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60490-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stift M., Berenos C., Kuperus P., Van Tienderen P. (2008). Segregation models for disomic, tetrasomic and intermediate inheritance in tetraploids: a general procedure applied to Rorippa (yellow cress) microsatellite data. Genetics 179 2113–2123. 10.1534/genetics.107.085027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover E., Shatters R., McCollum G., Hall D. G., Duan Y. (2010). Evaluation of Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus titer in field-infected trifoliate cultivars: preliminary evidence for HLB resistance. Proc. Fla. State Hortic. Soc. 123 115–117. [Google Scholar]

- Sybenga J. (1994). Preferential pairing estimates from multivalent frequencies in tetraploids. Genome 37 1045–1055. 10.1139/g94-149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sybenga J. (1996). Chromosome pairing affinity and quadrivalent formation in polyploids: do segmental allopolyploids exist? Genome 39 1176–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan F. Q., Tu H., Liang W. J., Long J. M., Wu X. M., Zhang H. Y., et al. (2015). Comparative metabolic and transcriptional analysis of a doubled diploid and its diploid citrus rootstock (C. junos cv. Ziyang xiangcheng) suggests its potential value for stress resistance improvement. BMC Plant Biol. 15:89. 10.1186/s12870-015-0450-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan F. Q., Tu H., Wang R., Wu X. M., Xie K. D., Chen J. J., et al. (2017). Metabolic adaptation following genome doubling in citrus doubled diploids revealed by non-targeted metabolomics. Metabolomics 13:143 10.1007/s11306-017-1276-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Udall J. A., Wendel J. F. (2006). Polyploidy and crop improvement. Crop Sci. 46 3–14. 10.2135/cropsci2006.07.0489tpg [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G. A., Prochnik S., Jenkins J., Salse J., Hellsten U., Murat F., et al. (2014). Sequencing of diverse mandarin, pummelo and orange genomes reveals complex history of admixture during citrus domestication. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014 656–662. 10.1038/nbt.2906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G. A., Terol J. F., Ibáñez V., López-García A., Pérez-Román E., Borredá C., et al. (2018). Genomics of the origin and evolution of Citrus. Nature 554 311–316. 10.1038/nature25447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie K. D., Xia Q. M., Wang X. P., Liang W. J., Wu X. M., Grosser J. W., et al. (2015). Cytogenetic and SSR-marker evidence of mixed disomic, tetrasomic, and intermediate inheritance in a citrus allotetraploid somatic hybrid between ‘Nova’ tangelo and ‘HB’ pummelo. Tree Genet. Genomes 11:112 10.1007/s11295-015-0940-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. N., Ye X. R., Choi S., Molina J., Moonan F., Wing R. A., et al. (2001). Construction of a 1.2-Mb contig including the citrus tristeza virus resistance gene locus using a bacterial artificial chromosome library of Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. Genome 44 382–393. 10.1139/g01-021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.