Abstract

Introduction

The patellar tendon graft has long been the gold standard for ACL reconstruction. Recently semitendinosus and gracilis tendons graft have been used increasingly. We hypothetise that the Bone-Patella Tendon-Bone graft is a good and economical graft for the Indian population with no adverse effects of anterior knee pain or patellar tendon shortening. We believe that the early squatting and cross-legged sitting causes early and constant stretching of the tendon in our patients. This is responsible for the lesser incidences of adverse effects in the Indian population.

Material and Method

In a retrospective study, the hospital database was scrutinized to shortlist patients who had undergone a bone-patella tendon-bone harvest for ACL or PCL reconstruction before 2013. Each patient was evaluated using the Lysholm score and the KOOS Score. VAS was also used, to evaluate for the amount of pain experienced by patients. The analysis of the quadriceps power along with the presence or absence of any extensor lag was made too. The modified Insall Salvati index was also calculated.

Results

Forty-seven patients were shortlisted of which 25 patients were followed up with an average follow up of 94.5 months. Although some patients did complain of occasional pain with the average VAS score of 1.45; on analyzing the data it was evident that all our patients had excellent quadriceps power (5/5) with no extensor lag. The mean Lysholm score was 95.55, while the mean KOOS score was 94.17. The mean Insall index of 1.05 showed no significant patella baja in any of our patients.

Conclusion

It is ascertained that no significant retro-patellar pain or shortening of the patellar tendon occurs following a bone patella tendon bone harvest. The bone patella bone tendon graft is a suitable graft for ligament reconstruction with good functional outcome, and no significant adverse effect of patella baja or anterior knee pain in the Indian patients.

Level of Evidence

Level IV.

Keywords: Bone-patella tendon-bone graft, Patella baja, Anterior knee pain

1. Introduction

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) acts as the primary stabilizer against anterior translation and plays a significant role in counter balancing rotational and valgus stresses around the knee.1 Following injury to the ACL, patients complain of multiple episodes of instability, pain, swelling and reduced or restriction of functional activity.2 Reconstruction of the ACL deficient knee is unanimously accepted as the treatment of choice for athletic patients and individuals experiencing instability in day to day activities.3

Patella tendon graft has been the gold standard for ACL reconstruction. However, recently semitendinosus and gracilis tendon graft have been used increasingly. The several ill effects of the patellar tendon graft harvest described in literature have nourished this trend towards popularization of the hamstring grafts.4

Various morbidities have been described as a consequence of harvesting the central third of the patellar tendon and its bony attachments. Patellar fracture, rupture of the extensor mechanism, contracture of the remaining patella tendon inducing patella baja, quadriceps weakness, and patella subluxation are few of the common complications sited.5 Anterior knee pain following ACL reconstruction has also been attributed to harvesting of the patellar tendon grafts occurring as a result of weakening of the extensor apparatus, patella femoral strain, and pressure.6

We, however, have not observed many of our patients coming back to us complaining of anterior knee pain or an extensor lag following a bone-patella tendon-bone graft reconstruction. Also, there have been very few studies on Indian patients who have special demands of squatting, sitting cross-legged and kneeling daily. We aimed to evaluate patients with a follow up of at least two years or more following a bone-patella tendon-bone harvest, for their complaints of anterior knee pain, extensor lag and knee function. We believe that because of the constant stretching of the post-surgical scar due to early squatting and cross-legged sitting demanded by the lifestyle of most of our patients, there is no scar contracture or retro-patellar fat pad fibrosis causing shortening of the patellar tendon.

2. Material and method

In a retrospective study, we scrutinized the hospital database to shortlist patients who had undergone a bone-patella tendon-bone harvest for ACL or PCL reconstruction before 2013. All patients were contacted telephonically and called for follow up. Patients were enrolled for the study irrespective of having undergone a single ligament, multiple ligaments or a revision ligament reconstruction. Patients with pre surgery arthritic changes were however excluded from the study. This study was performed with clearance from the ethical committee. An informed consent was taken from every patient before being enrolled in the study.

The same surgeon had operated all patients with the knee flexed on the table at 90°. The central third of the tendon along with bone plugs on both ends were harvested using either a single incision or two small incisions. For ACL reconstruction the bone plug at both ends were kept at 25 mm. Whereas for PCL reconstruction the patellar bone plug was kept at 20 mm to ease maneuvering through the killer turn and the tibial plug was kept longer at 45–55 mm to attain sufficient length. The average length of the tendon being approximately 30 mm. Interference screw was used for fixation at both ends.

Each patient was evaluated for the functional result using the Lysholm7 score and the KOOS8 Score. The Visual Analogue Scale9 (VAS) was used to evaluate for the amount of pain experienced by patients. A special note was made regarding the ability of the patient to kneel and squat.

The analysis of the quadriceps power along with the presence or absence of any extensor lag was also made. The patients were also subjected to plain antero-posterior, lateral and merchant’s roentgenograms to rule out any degenerative changes in the tibio-femoral as well as the patellofemoral joint. The modified Insall Salvati index10 was also calculated of both limbs to evaluate for any patella baja or alta in comparison to the contra-lateral side.

The data was analyzed using descriptive statistics. The statistical data was extrapolated, and followed by discussing its clinical significance.

3. Rehabilitation protocol

Most of our ligament surgeries using Bone-Patella tendon-Bone grafts have been for ACL reconstruction. In a patient with isolated ACL reconstruction we allowed full weight bearing from second post-operative day along with active quadriceps and straight leg raise in brace only. At our center we follow an open chain physiotherapy protocol, allowing high sitting knee bending once quadriceps have a good control. In a multiple ligament reconstruction patient we allowed full weight bearing in extension brace from the 10th post-operative day. The same was followed in patients with an associated meniscus injury. We allowed only prone knee bending in patients who had undergone PCL reconstruction, isolated or with any other ligament. On achieving active 90° flexion with good quadriceps control, we started with resistive training program. The average time for this was around 6–8 weeks. Sports specific training and agility training was started after 3 months in isolated ACL reconstruction patients, which was however delayed to 5–6 months in a patient with multiple ligament or PCL reconstruction.

4. Results

Forty-seven patients were shortlisted of which only thirty could be contacted. Five refused to come for follow up for various reasons and we managed to follow up 25 patients (Table 1) who had undergone arthroscopic ligament reconstruction surgery of the knee using bone patella tendon bone as a graft material before 2013. The average follow up was of 94.5 months ranging from 23 to 228 months. Twenty of the patients followed up were males and five females, with an average age of 40.5 years.

Table 1.

Long term follow up of 25 patients with Bone-Patella tendon-bone graft harvest for ligament reconstruction surgery.

| S.No | Age/Sex | Injury | Associated Surgery | Follow-up (in months) | VAS (for anterior knee pain) | KOOS | Lysholm | Insall Salvati Index (N = 0.8–1.2) | Cartilage Injury (As Per ICRS) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37Y/F | ACL/MM | MM Debridement | 87 | 3 | 71 | 74.4 | 1.07 | MFC/MTC/LTC Grd III-IV | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag/Missed PLC |

| 2 | 42Y/M | ACL | 120 | 0 | 99 | 100 | 1.09 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 3 | 44Y/M | ACL | 41 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0.86 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 4 | 35Y/M | ACL/PCL/PLC | PCL reconstruction/PLC reconstruction | 99 | 0 | 99 | 92.1 | 1.32 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | |

| 5 | 34Y/M | ACL/MM | MM Debridement | 36 | 2 | 95 | 92.9 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 6 | 20Y/M | ACL/PLC | PLC reconstruction | 35 | 3 | 95 | 93.5 | 0.76 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | |

| 7 | 23Y/F | ACL/PCL/LM | PCL augmentation/LM repair | 24 | 4 | 90 | 82.1 | 1.37 | MTC/LTC Grd III-IV | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag/ |

| 8 | 48Y/M | PCL | 80 | 1 | 99 | 100 | 1.37 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 9 | 20Y/M | ACL/LM | LM repair | 25 | 0 | 100 | 92.9 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 10 | 47Y/M | ACL/MM | MM debridement | 56 | 2 | 100 | 94.6 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 11 | 32Y/M | ACL/PLC | PLC augmentation | 25 | 2 | 100 | 100 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 12 | 51Y/M | Rev ACL | 101 | 0 | 98 | 94.8 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | |||

| 13 | 30Y/M | ACL | 120 | 4 | 100 | 94.6 | 0.94 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 14 | 32Y/M | ACL | 120 | 0 | 100 | 100 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | |||

| 15 | 48Y/M | ACL/PLC | PLC reconstruction | 116 | 1 | 98 | 94.8 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 16 | 45Y/M | ACL | 228 | 3 | 94 | 93.5 | MTC Grd III | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 17 | 37Y/M | ACL | 181 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0.89 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 18 | 55Y/M | ACL | 174 | 1 | 99 | 98.5 | 0.98 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 19 | 44Y/M | ACL/PCL | PCL reconstruction | 156 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 1.02 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | |

| 20 | 55Y/M | ACL/LM | LM debridement | 204 | 0 | 98 | 98.5 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 21 | 50Y/F | ACL/PCL/MCL | PCL reconstruction | 112 | 0 | 96 | 98 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 22 | 42Y/M | ACL | 2Y9M | 2 | 98 | 99 | 0.92 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | ||

| 23 | 53Y/M | ACL/PCL/MM | PCL augmentation/MM repair | 2Y | 2 | 96 | 98.5 | 1.2 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | |

| 24 | 32Y/M | ACL/PCL | PCL reconstruction | 6Y3M | 2 | 86 | 82.1 | MFC/MTC Grd III-IV | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag | |

| 25 | 57Y/F | ACL | 4Y | 2 | 96 | 98 | No Quad weakness/No extensor lag |

ACL: Anterior Cruciate Ligament.

PCL: Posterior Cruciate Ligament.

PLC: Postero-lateral Corner.

MM: Medial Meniscus.

LM: Lateral Meniscus.

VAS: Visual Analogue Scale.

KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score.

MFC: Medial Femoral condyle.

MTC: Medial Tibial Condyle.

LTC: Lateral Tibial Condyle.

Quad: Quadriceps.

Thirty two percent of the patients followed up were involved in active sports, while 24% participated in recreational sport activities. Forty four percent required to squat on the ground on a regular basis for their day to day activities or religious offerings. Thirty two percent were using Indian type of toilets, which demands squatting.

Although four patients did complain of occasional pain with the average VAS score of 1.45; on analyzing the data it was evident that all our patients had excellent quadriceps power (5/5) with no extensor lag. The occasional pain was described as more of discomfort in the knee rather than anterior knee pain, which did not interfere with any activity. It was also evident that patients with a poor VAS score had associated articular cartilage damage at the time of surgery.

The mean Lysholm score was 95.55, while the mean KOOS score was 94.17. Except four, none of our patients complained of any difficulty in squatting. Only one complained of instability due to an associated lateral injury, which was missed during the previous surgery. None of the patients had any difficulty in climbing stairs or complained of locking. Five gave history of occasional episodes of swelling after a full day of rigorous activity or extremely strenuous exercise, which settled within 1–2 days. The occurrence of swelling was however not constant and did not occur after every such incident. We could not figure out any explanation for this in three of the patients, clinical examination showed no ligament laxity.

The roentgenograms made it evident that there were no osteoarthritic changes in the patella-femoral joint or the medial tibio-femoral joint in most patients except four. Two of the patients although were not diagnosed of patella-femoral alterations pre-operatively, intraoperative grade I–II affection was found. The patients with the arthritic changes had associated articular cartilage damage during surgery. The mean Insall index of 1.05 showed no significant patella baja in any of our patients, despite an average seven years follows up with regular sitting on the ground and squatting. One patient although had an Insall index of 0.76, had no complaints in his knee. Three of the patients showed an Insall index more than 1.2, however when compared to their opposite knees, the index of both sides were comparable. There was no patello-femoral crepitus in any of our patients or any effusion at the time of clinical examination during the follow up visit (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

A young man operated for ACL reconstruction with a 10 years follow up having full extension with good range of motion. The Insall Salavati index shows no patella baja.

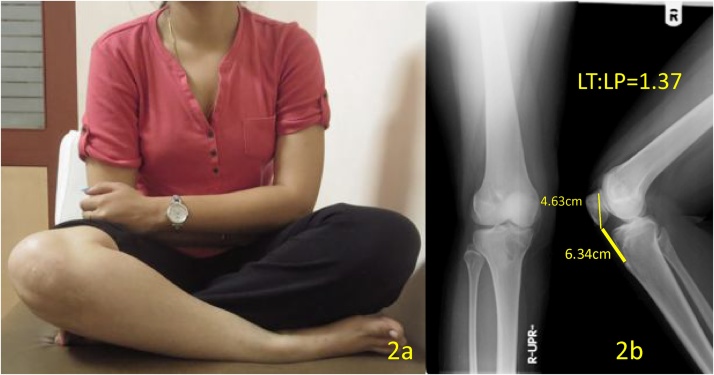

Fig. 2.

A 23 year old female operated almost 2 years back with a good range of motion and no complaint of anterior knee pain. The Insall Index of 1.37 was comparable to her opposite knee.

Fig. 3.

A 108 kg man operated 10 years back for ACL reconstruction using the long incision for graft harvest with no pain and good range of motion. There is no patella baja.

5. Discussion

The incidence of anterior knee pain as reported in literature varies from 4 to 60%.11 In our series only two patients out of 25 complained of pain under the patella after an episode of extremely strenuous activity or rigorous exercise. This occurrence was however not a constant phenomenon and occurred only occasionally. A few patients complained of pain along the medial joint line, these patients however, had associated articular cartilage damage to the grade of III–IV at the time of arthroscopy. In most of the patients who complained of pain, it was described as more of discomfort rather than true pain felt only after very strenuous activity or at the end of the day. None of the patients complained of restriction of activity due to the pain or discomfort in knee. Almost all our patients sit on the ground in cross legged position for their daily activities still there was no clinical evidence of patella-femoral articular changes.

Pain may be related to patella-femoral cartilage affection, patella tendinopathy of the donor site or injury to the infra-patellar branches of the saphenous nerve. In our series only three complained of numbness around the graft harvest scar. As shown by Kartus et al.12 and Tsuda et al.13, small incision approach to harvest the graft spares the nerve, thus decreasing chances of neuroma and hence anterior knee pain. Tsuda et al.13 advocated using transverse incisions and dissecting the retinaculum. They suggested, by using horizontal incisions the chance of potential injury to neurologic structures is reduced. It also provides better access to the tendon width. We however used a vertical incision due our familiarity with the technique. In our study, the incidence of pain was lower in patients with a small incision used to harvest the graft.

On analyzing Lysholm and KOOS score, it was evident that the patients were doing excellent functionally. The mean Lysholm score was 95.55 ranging from 71 to 100. The poor score in four of the patients were due to associated injuries or incidences of repeat injuries following the primary surgery and not as a result of the primary graft harvest. The mean KOOS score in our series was 94.17, representing a good to excellent level of function. The patients in our study were greatly satisfied with their results and the functionality of their knees. Four of the patients however had poor scores due to repeat injury in three and a missed PLC injury with associated articular cartilage injury in all four. Eriksson et al.14 showed significant improvement in knee function, activity level and IKDC and Lysholm scores in their study.

Dandy and Desai15 showed six percent shortening of the patellar tendon due to harvesting of the bone patella tendon bone graft. Retro-patellar fat pad fibrosis due to the surgical trauma, scar contraction and quadriceps weakness were the possible causes put forward by them leading to patella baja. Quadriceps inhibition weakness following surgery could also be the reason for delayed rehabilitation, causing extension deficit and abnormal patellofemoral joint stresses. All our patients were able to do active quadriceps with straight leg raise from the second post-operative day without any trouble.

Shelbourne et al.16 in a series of 71 patients showed patellar tendon shortening of less than one percent, all patients in their series had undergone identical patellar tendon ACL reconstruction, operated by the same surgeon, and underwent the same rehabilitation program. Patellar tendon shortening of 0.51% was reported by Krosser et al.17 in a study of 55 patients, in all the patients the mid-third of the tendon was harvested and had the defect sutured. In their series the maximum reported shortening was of 4.3%.

Hantes et al.18 found that in patients with ACL reconstruction with Hamstring tendons, a minimal shortening of the patellar tendon occurs; even without any direct trauma to the patellar tendon. In several studies, the shortening of the patellar tendon has been related with anterior knee pain.15, 19, 20

In our series of 25 patients, however only one patients showed minimal patella baja with an insall index of 0.76, which was however comparable to the contralateral limb. There were no complaints of pain or restriction of daily activities. In 14 of our patients the tendon was harvested with a long incision and with a small incision in 11. Despite the length of incision, none of the patients showed patellar tendon shortening except one nor significant pain. Two of our patients had a grade I–II patella-femoral cartilage affection at the time of surgery, these patients have in-fact reported an improvement in their quality of life after their ligament reconstruction surgery.

5.1. Limitations

The follow up is varied, ranging from 23 to 228 months. We also have a significant loss to follow up. Due to change in contact details a lot of patients could not be contacted. In addition, including isolated ACL, PCL reconstructions along with multi-ligament reconstruction patients in the same series may be a source of bias. We also could not attain the Insall-Salvati index of all the patients who were followed up, as not everyone agreed for a repeat plain radiograph.

6. Conclusion

Our study ascertains that no significant shortening of the patellar tendon occurs following a bone patella tendon bone harvest even after many years of strenuous activities. The bone patella tendon bone is a suitable and economical graft for ligament reconstruction with good functional outcome, with no significant adverse effect of patella baja or anterior knee pain in the Indian patients.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The authors did not receive any financial aid from any person or pharmaceutical company or surgical implant company for this study.

Disclosure

The authors did NOT receive any financial aid from any person, pharmaceutical company or surgical implant company for this study.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Dhiren Shah M.D. (Radiodiagnosis).

References

- 1.Butler D.L., Noyes F.R., Grood E.S. Ligamentous restraints to anterior-posterior drawer in the human knee: a biomechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:259–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson R.J., Eriksson E., Haggmark T., Pope M.H. Five- to ten-year follow-up evaluation after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Clin Orthop. 1984;183:122–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howe J.G., Johnson R.J., Kaplan M.J., Fleming B., Jarvinen M. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using quadriceps patellar tendon graft. Part I. Long-term follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:447–457. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keays S., Bullock-Saxton J., Keays A., Newcombe P. Muscle strength and function before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using semitendonosus and gracilis. Knee. 2001;8:229–234. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0160(01)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonatus T.J., Alexander A.H. Patellar fracture and avulsion of the patellar ligament complicating arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop Rev. 1991;20:770–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daluga D., Johnson C., Bach B.R. Primary bone grafting following graft procurement for anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency. J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 1990;6:205–208. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(90)90076-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lysholm J., Gillquist J. Evaluation of knee ligament surgery results with special emphasis on use of a scoring scale. Am J Sports Med. 1982;10:150–154. doi: 10.1177/036354658201000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roos Ewa M., Stefan Lohmander L. The knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:64. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawker Gillian A., Mian Samra, Kendzerska Tetyana, French Melissa. Measures of adult pain: visual analog scale for pain (VAS pain), numeric rating scale for pain (NRS pain), McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ), short-form McGill pain questionnaire (SF-MPQ), chronic pain grade scale (CPGS), short form-36 bodily pain scale (SF-36 BPS), and measure of intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain (ICOAP) Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(November (S11)):S240–S252. doi: 10.1002/acr.20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grelsamer R.P., Meadows S. The modified Insall-Salvati ratio for assessment of patellar height. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(September (282)):170–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaieb M.D., Kan D.M., Chang S.K., Marumoto J.M., Richardson A.B. A prospective randomized comparison of patellar tendon versus semitendinosus and gracilis tendon autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:214–220. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300021201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kartus J., Ejerhed L., Sernert N., Brandsson S., Karlsson J. Comparison of traditional and subcutaneous patellar tendon harvest. A prospective study of donor site-related problems after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using different graft harvesting techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:328–335. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280030801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuda E., Okamura Y., Ishibashi Y., Otsuka H., Toh S. Techniques for reducing anterior knee symptoms after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using a bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:450–456. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290041201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eriksson K., Anderberg P., Hamberg P. A comparison of quadruple semitendinosus and patellar tendon grafts in reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;(83-B):348–354. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b3.11685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dandy D.J., Desai S.S. Patellar tendon after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76:198–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shelbourne K.D., Trumper R.V. Preventing anterior knee pain after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:41–47. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krosser B.I., Bonamo J.J., Sherman O.H. Patellar tendon length after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A prospective study. Am J Knee Surg. 1996;9:158–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hantes M.E., Zachos V.C., Bargiotas K.A., Basdekis G.K., Karantanas A.H., Malizos K.N. Patellar tendon length after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a comparative magnetic resonance imaging study between patellar and hamstring tendon autografts. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(June (6)):712–719. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chase J.M., Hennrikus W.L., Cullison T.R. Patella infera following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Contemp Orthop. 1994;28:487–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breitfuss H., Frohlich R., Povacz P., Resch H., Wicker A. The tendon defect after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using the midthird patellar tendon—a problem for the patellofemoral joint? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1996;4:194–198. doi: 10.1007/BF01466615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]