Abstract

Plants are important components of any rangeland. However, the importance of desert rangeland plant diversity has often been underestimated. It has been argued that desert rangelands of Tunisia in good ecological condition provide more services than those in poor ecological condition. This is because rangelands in good condition support a more diverse mixture of vegetation with many benefits, such as forage for livestock and medicinal plants.

Nearly one-quarter of Tunisia, covering about 5.5 million hectares, are rangelands, of which 87% are located in the arid and desert areas (45% and 42%, respectively). Here, we provide a brief review of the floristic richness of desert rangelands of Tunisia. Approximately 135 species are specific to desert rangelands. The predominant families are Asteraceae, Poaceae, Brassicaceae, Chenopodiaceae, and Fabaceae. These represent approximately 50% of Tunisian desert flora.

Keywords: Vegetation, Dryland, Species richness

1. Introduction

Rangelands cover about 40% of the world's land area (White et al., 2000) and are as ecologically important as rain forests (Casper, 2009). Arid ecosystems comprise one-third of the global land surface, support 14% of the world's inhabitants, and provide a significant share of the world's agriculture (Nicholson, 2011). Arid environments may not be the most hospitable places on Earth, but the 30% or more of the global land surface that they cover does support an ever-growing human population and has fascinated explorers and scientists for centuries (Thomas, 2011).

Desert rangelands, like other arid rangelands, suffer from severe natural disturbances such as high rates of soil degradation and extremely low rainfall distribution, which, in part, may be caused by the climate due to their geographical location (Le Houérou, 2009). These problems are generally compounded by anthropogenic factors such as overgrazing and wood harvesting (Le Houérou, 2009). Taken together, these factors contribute to decreased biological diversity and rangeland productivity, as well as high rates of erosion, all of which are widespread problems in Tunisia (Gamoun, 2012, Tarhouni et al., 2014).

Tunisia is a small country, yet has highly diverse climatic and edaphic conditions (Floret and Pontanier, 1982). Rangelands constitute the largest use of land in Tunisia, where pastoralism remains vital. Furthermore, rangelands not only provide important goods and services but also represent a tremendous source of biodiversity. Nearly one quarter of Tunisia is rangeland, occupying about 5.5 million hectares, 87% of which are located in the arid and desert areas (45% and 42%, respectively). In Northern Africa, the term “desert” is most properly applied to zones that receive less than 100 mm of average annual rainfall, are little affected by human activity, and possess a very low production potential or likelihood of future evolution (Floret and Pontanier, 1982). The majority of the rangelands of south Tunisia exhibit moderate or severe desertification, and are being damaged and made less productive by mismanagement (Nefzaoui et al., 2011). Desertification includes deterioration of ecosystems and degradation of various forms of vegetation (Le Houérou, 1969).

The causes of desertification are myriad and often interconnected. They include overgrazing and overcutting for firewood and timber, inappropriate farming, poor irrigation, and poor management, which has led to salinity problems, mining, construction of highways and utility corridors, air pollution, recreational activities, particularly off-road vehicle recreation, and climate change (Bainbridge, 2007). The underlying causes of dryland degradation are commonly economic and cultural, rather than ecological (Hallsworth, 1987, Carney and Farrington, 1998, Chambers et al., 1991). The primary causes of current degradation in some arid areas have been identified as intensified and irrational human activities and climate variability (Ouled Belgacem and Louhaichi, 2013). Overgrazing is the main cause of rangeland degradation and desertification (Le Houérou, 1996, Ibáñez et al., 2007, Gamoun, 2014, Gamoun and Hanchi, 2014). It may be driven by economic pressure, greed, desperation, and sometimes ignorance (Bainbridge, 2007). For example, Africa as a whole contributes 36% of the world's total land degraded by overgrazing and 49%–90% of the continent's rangelands are believed to already be in the process of long-term degradation (Hudak, 1999).

The primary effects of overgrazing have been reported to be mainly of a biotic nature, resulting in a decrease in plant cover, and in particular, a loss of perennials, which constitutes one of the most significant indicators of desertification (Verstraete and Schwartz, 1991, Aronson et al., 1993). The main consequences of overloading rangelands are summarized as follows: (i) an increase in cultivated land decreases rangeland area; (ii) an increase in livestock number decreases rangeland area; (iii) rangeland is degraded, decreasing both forage yield and carrying capacity (Zhao et al., 1994).

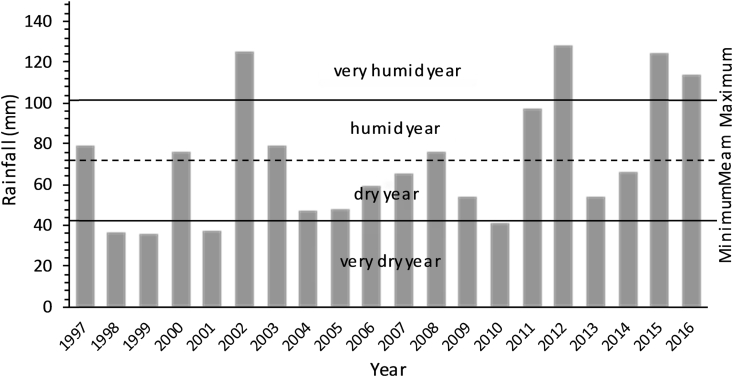

Desertification is largely a response to climatic trends and fluctuations in the availability of resources (Wang et al., 2005). Climate variability (high temperatures and low rainfall distribution) negatively affects rangeland productivity (Peters et al., 2013), and is most severe in dryland areas (Le Houérou, 1996, Darkoh, 1998, Harris, 2010, Reynolds, 2013). Sequences of dry years have been a major climatic force in the degradation of rangelands (Verner, 2013). The unreliable distribution of rainfall is an important component which contributes significantly towards the deterioration of rangeland productivity in the dry areas (Floret et al., 1978, Gamoun, 2013, Gamoun, 2014, Gamoun and Hanchi, 2014, Gamoun et al., 2016, Gamoun, 2016). Evidence of this is provided through long term annual rainfall figures in Tunisia, which reveal that desert rangelands are characterized by a dry climate, with hot dry summers and winters and very low levels of precipitation---about 75 mm---from 1997 to 2016 (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

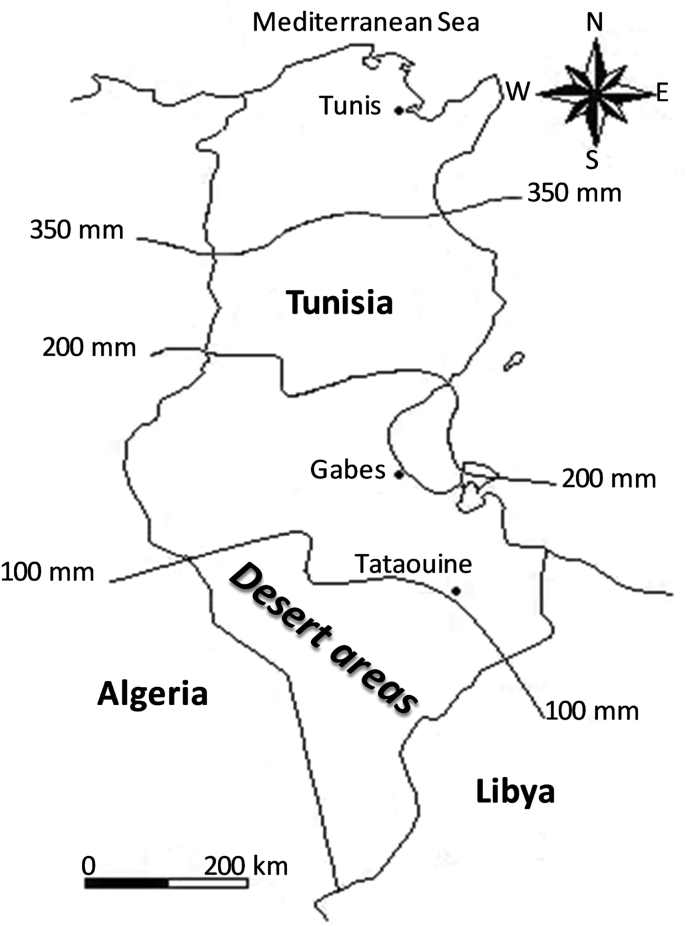

Fig. 1.

Isohyetal map of Tunisia (curves with mm values represent mean annual rainfall).

Fig. 2.

Rainfall variation between 1997 and 2016 in Southern Tunisia (Remada).

The flora of desert areas has always attracted ecologists from around the world (Ward, 2016). As a result, the arid zones of Tunisia have been extensively studied over the past fifty years; indeed, the arid zone flora, climate, ecology, hydrogeology, and soils of Tunisia are among the best known in the world.

By any measure, the world's arid rangelands qualify as modest repositories of biodiversity (Shachak et al., 2005). The biological diversity of many desert and semi-desert areas continues to be threatened by many different human activities, such as overharvesting of firewood and overgrazing (Bainbridge, 2007). In these areas, where overgrazing and wood collection drive changes in the structure and functioning of rangelands, any decrease in perennial plant cover and plant species diversity leads to changes in floristic composition, soil erosion, and modifications in nutrient, water, and energy flow (Floret et al., 1978, Jauffret and Lavorel, 2003).

In this paper, we provide a brief review of the floristic richness of part of a desert rangeland in Tunisia.

2. Rangeland diversity

Researchers in Tunisia have focused a lot of attention on rangelands as well as on plant diversity and community ecology (Ouled Belgacem et al., 2011, Tarhouni et al., 2015). Tunisia's rangelands span a wide variety of environments from the arid steppe to desert rangelands of southern Tunisia. As in all Mediterranean countries, these steppe zones were previously used mainly for grazing and have been subjected to severe pressure from an increasing population, which has slowly stabilized (Floret and Hadjej, 1977). In response to climatic conditions and grazing, the species composition, diversity and abundance, community structure, and plant life forms also changed (Ouled Belgacem et al., 2011, Tarhouni et al., 2015, Gamoun, 2016, Gamoun et al., 2016). Heavy grazing has left Tunisian ecosystems with a homogenized flora consisting only of species that are unpalatable and highly tolerant to herbivory and other forms of disturbance (Gondard et al., 2003, Jauffret and Lavorel, 2003). Sand deposits due to strong desert winds also further decrease vegetation growth by burying some plant parts, gradually decreasing the floristic variety (Bendali et al., 1990).

Sustainable rangeland management approaches have now been used to protect some sections of these desert rangelands in an effort to reduce the effects of degradation by increasing the vegetation composition, spatial distribution, and structure (Floret, 1981, Ouled Belgacem et al., 2008, Gamoun et al., 2010, Tarhouni et al., 2015). As a result, such sustainable practices have yielded diverse rangeland resources, with an abundant and rich diversity of plant species (Fig. 3, Fig. 4 and Table 1).

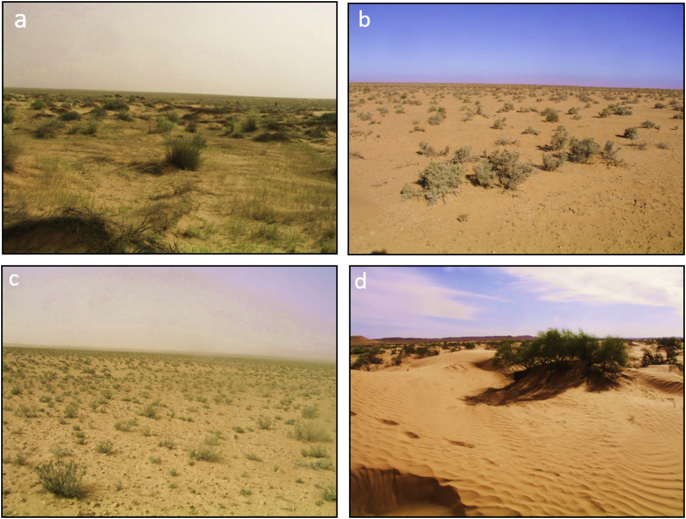

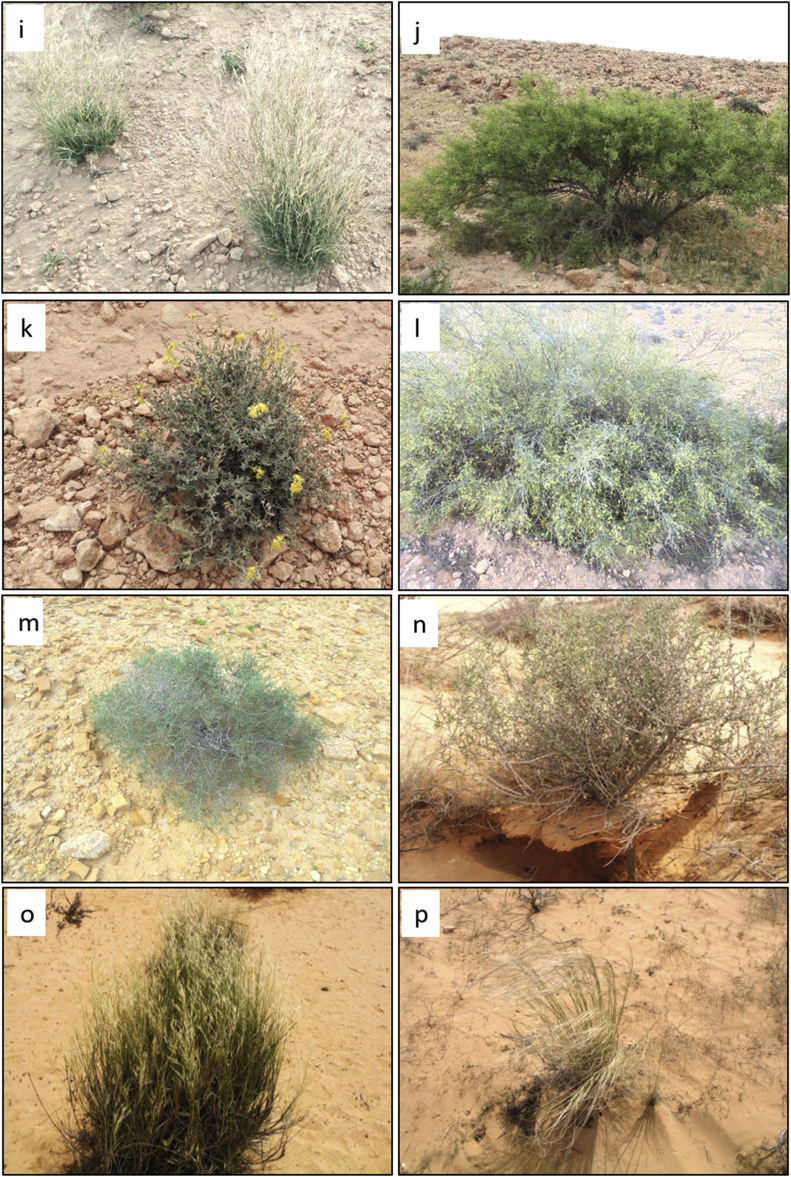

Fig. 3.

Photographs showing different rangelands types: (a) Psammophytes of Stipagrostis pungens on sand accumulation being grazed by camels from the typical desert vegetation site where protecting the vegetation promotes infiltration and minimizes runoff. (b) Example of an almost flat, sandy area unit, where the vegetation is dominated by Haloxylon schmittianum. (c) Good stand of Anthyllis henoniana community type in stony terrain showing the spacing of the shrubs. (d) Retama raetam growing on sand dunes.

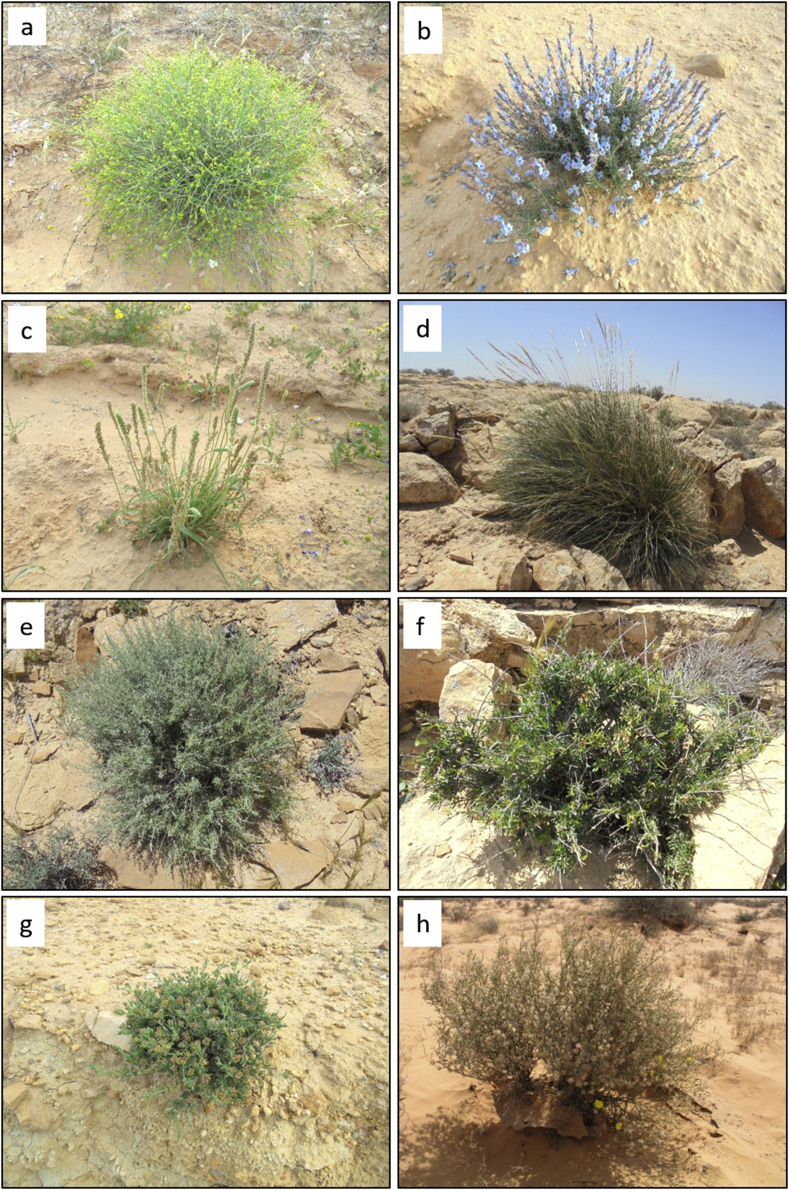

Fig. 4.

Some plant species of desert rangelands of Tunisia (photos by Mouldi Gamoun); (a) Rhanterium suaveolens Desf., (b) Echiochilon fruticosum Desf., (c) Plantago albicans L., (d) Stipa tenacissima L., (e) Artemisa herba-alba Asso, (f) Periploca angustifolia Labill., (g) Gymnocarpos decander Forssk., (h) Anthyllis henoniana Batt., (i) Stipagrostis ciliata (Desf.) de Winter (j) Ziziphus lotus (L.). Lam., (k) Helianthemum kahiricum Delile, (l) Retama raetam (Forssk.) Webb & Berthel., (m) Haloxylon scoparium Pomel., (n) Haloxylon schmittianum Pomel., (o) Stipagrostis pungens (Desf.) de Winter, (p) Stipa lagascae Roem. & Schult.

Table 1.

Family, life form, and livestock acceptability index of main desert species of Tunisia. 0: Refusal or Toxic; 1: Occasionally palatable; 2: Few palatable; 3: Palatable; 4: Very palatable; 5: Extremely palatable.

| Species | Family | Life form | Acceptability index |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthyllis henoniana Batt. | Fabaceae | Chamaephyte | 4 |

| Ajuga iva (L.) Schreb. | Lamiaceae | Therophyte | 3 |

| Allium roseum L. | Alliaceae | Geophyte | 2 |

| Anabasis oropediorum Maire. | Chenopodiaceae | Chamaephyte | 5 |

| Anacyclus clavatus (Desf.) Pers. | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 4 |

| Anacyclus monanthos ssp cyrtolepidioides (Pomel) | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 4 |

| Anarrhinum fruticosum Desf. subsp. Brevifolium | Scrophulariaceae | Chamaephyte | 1 |

| Argyrolobium uniflorum (Deene.) Jaub. & Spach. | Fabaceae | Chamaephyte | 5 |

| Arnebia decumbens (Vent.) Coss. & Kralik | Boraginaceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Artemisia campestris L. | Asteraceae | Chamaephyte | 2 |

| Artemisia herba-alba Asso | Asteraceae | Chamaephyte | 2 |

| Asphodelus refractus Boiss. | Asphodelaceae | Therophyte | 1 |

| Asphodelus tenuifolius Cav. | Asphodelaceae | Therophyte | 0 |

| Astragalus armatus Willd. | Fabaceae | Chamaephyte | 2 |

| Astragalus asterias Steven. | Fabaceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Astragalus corrugatus Bertol. | Fabaceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Atractylis cancellata L. | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 1 |

| Atractylis carduus (Forssk.) C. Chr. | Asteraceae | Chamaephyte | 0 |

| Atractylis prolifera Boiss. | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 1 |

| Atractylis serratuloides Sieber ex Cass. | Asteraceae | Hemicryptophyte | 2 |

| Atriplex halimus L. | Chenopodiaceae | Nanophanerophyte | 3 |

| Bassia muricata (L.) Asc. | Chenopodiaceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Brassica tournefortii Gouan. | Brassicaceae | Therophyte | 3 |

| Calendula tripterocarpa Rupr. | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 1 |

| Calicotome villosa (Poir.) Link. | Fabaceae | Nanophanerophyte | 3 |

| Calligonum azel Maire | Polygonaceae | Nanophanerophyte | 3 |

| Calligonum polygonoides L. | Polygonaceae | Nanophanerophyte | 4 |

| Carthamus eriocephalus (Boiss.) Greuter | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 1 |

| Centaurea furfuracea Coss. & Durieu. | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 3 |

| Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. | Cucurbitaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 0 |

| Cleome amblyocarpa Barratte & Murb. | Cleomaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 0 |

| Convolvulus supinus Coss. & Kralik. | Convolvulaceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Cuscuta epithymum (L.) L. | Cuscutaceae | Therophyte | 0 |

| Cutandia dichotoma (Forssk.) Batt. & Trab. | Poaceae | Therophyte | 4 |

| Cynara cardunculus L. subsp. Cardunculus | Asteraceae | Hemicryptophyte | 0 |

| Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. | Poaceae | Geophyte | 5 |

| Cynomorium coccineum L. | Cynomoriaceae | Geophyte | 0 |

| Daucus sahariensis Murb. | Apiaceae | Therophyte | 3 |

| Deverra denudata (Viv.) R. Pfiesterer & Podlech. | Apiaceae | Chamaephyte | 2 |

| Deverra tortuosa (Desf.) DC. | Apiaceae | Chamaephyte | 2 |

| Dipcadi serotinum (L.) Medik. | Hyacinthaceae | Geophyte | 0 |

| Diplotaxis harra (Forssk.) Boiss. | Brassicaceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Diplotaxis simplex Spreng. | Brassicaceae | Therophyte | 3 |

| Echinops spinosus L. | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 0 |

| Echiochilon fruticosum Desf. | Boraginaceae | Chamaephyte | 5 |

| Enarthrocarpus clavatus Godr. | Brassicaceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Ephedra altissima Desf. | Ephedraceae | Nanophanerophyte | 2 |

| Erodium crassifolium L’Hér. | Geraniaceae | Therophyte | 3 |

| Erodium glaucophyllum (L.) L’Hér. | Geraniaceae | Therophyte | 1 |

| Erucaria pinnata (Viv.) Täckh. & Boulos | Brassicaceae | Therophyte | 3 |

| Eryngium ilicifolium Lam. | Apiaceae | Therophyte | 0 |

| Euphorbia retusa Forssk. | Euphorbiaceae | Therophyte | 0 |

| Euphorbia terracina L. | Euphorbiaceae | Therophyte | 0 |

| Fagonia cretica L. | Zygophyllaceae | Therophyte | 0 |

| Fagonia glutinosa Delile. | Zygophyllaceae | Therophyte | 0 |

| Farsetia aegyptia Turra. | Brassicaceae | Chamaephyte | 3 |

| Filago germanica L. | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 1 |

| Gagea fibrosa (Desf.) Schult. & Schult. f. | Liliaceae | Geophyte | 0 |

| Gymnarrhena micrantha Desf. | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Gymnocarpos decander Forssk. | Caryophyllaceae | Chamaephyte | 5 |

| Halocnemum strobilaceum (Pall.) M. Bieb. | Plumbaginaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 2 |

| Haloxylon schmittianum Pomel. | Chenopodiaceae | Chamaephyte | 1 |

| Haloxylon scoparium Pomel. | Chenopodiaceae | Chamaephyte | 1 |

| Haplophyllum tuberculatum (Forssk.) Juss. | Rutaceae | Chamaephyte | 0 |

| Helianthemum kahiricum Delile. | Cistaceae | Chamaephyte | 4 |

| Helianthemum sessiliflorum (Desf.) | Cistaceae | Chamaephyte | 5 |

| Herniaria fontanesii J. Gay. | Caryophyllaceae | Chamaephyte | 3 |

| Hippocrepis areolata Desv. | Fabaceae | Therophyte | 4 |

| Ifloga spicata (Forssk.) Sch. Bip., | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 1 |

| Kickxia aegyptiaca (L.) Nábelek. | Scrophulariaceae | Chamaephyte | 2 |

| Koelpinia linearis Pall. | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 4 |

| Launaea angustifolia (Desf.) Muschl. | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 4 |

| Launaea capitata (Spreng.) Dandy | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 3 |

| Launaea fragilis (Asso) Pau. | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Launaea nudicaulis (Linn.) Hook. f. | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 4 |

| Lavandula multifida L. | Lamiaceae | Chamaephyte | 0 |

| Limoniastrum guyonianum Boiss. | Plumbaginaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 3 |

| Limoniastrum monopetalum (L.) Boiss. | Plumbaginaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 3 |

| Limonium pruinosum (L.) Chaz. | Plumbaginaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 1 |

| Linaria laxiflora Desf. | Scrophulariaceae | Therophyte | 1 |

| Lobularia libyca (Viv.) Meissn. | Brassicaceae | Therophyte | 3 |

| Lotus halophilus Boiss. & Spruner | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 3 |

| Lycium shawii Roem. & Schult. | Solanaceae | Nanophanerophyte | 2 |

| Lygeum spartum Loefl. ex L. | Poaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 2 |

| Matthiola longipetala (Vent.) DC. | Brassicaceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Medicago minima (L.) L. | Fabaceae | Therophyte | 3 |

| Moricandia arvensis (L.) DC. | Brassicaceae | Chamaephyte | 2 |

| Muricaria prostrata (Desf.) Desv. | Brassicaceae | Therophyte | 3 |

| Neurada procumbens L. | Neuradaceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Nitraria retusa (Forssk.) Asch. | Nitrariaceae | Nanophanerophyte | 2 |

| Nolletia chrysocomoides (Desf.) Cass. ex Less. | Asteraceae | Chamaephyte | 2 |

| Nonea calycina (Roem. & Schult.) Selvi | Boraginaceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Pallenis hierochuntica (Michon) Greuter. | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Paronychia arabica (L.) DC. | Caryophyllaceae | Therophyte | 1 |

| Peganum harmala L. | Zygophyllaceae | Chamaephyte | 0 |

| Pennisetum divisum (Forssk. ex J.F. Gmel.) Henrard | Poaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 3 |

| Periploca angustifolia subsp. angustifolia (Labill.) | Asclepediaceae | Nanophanerophyte | 3 |

| Plantago albicans L. | Plantaginaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 5 |

| Plantago ovata Forssk. | Plantaginaceae | Therophyte | 3 |

| Polygonum equisetiforme Sibth. et Sm. | Polygonaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 4 |

| Reaumuria vermiculata L. | Tamaricaceae | Chamaephyte | 0 |

| Reichardia tingitana (L.) Roth | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Reseda alba L. subsp. Alba | Resedaceae | Therophyte | 1 |

| Retama raetam (Forssk.) Webb & Berthel. | Fabaceae | Nanophanerophyte | 3 |

| Rhanterium suaveolens Desf. | Asteraceae | Chamaephyte | 2 |

| Rhus tripartita (Ucria) Grande | Anacardiaceae | Nanophanerophyte | 2 |

| Salsola tetragona Delile | Chenopodiaceae | Phanerophyte | 2 |

| Salsola tetrandra Forssk. | Chenopodiaceae | Phanerophyte | 2 |

| Salsola vermiculata L. | Chenopodiaceae | Chamaephyte | 3 |

| Salvia aegyptiaca L. | Lamiaceae | Chamaephyte | 3 |

| Salvia verbenaca L. | Lamiaceae | Chamaephyte | 3 |

| Savignya parviflora (Delile) Webb. | Brassicaceae | Therophyte | 3 |

| Scabiosa arenaria Forssk. | Dipsacaceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Schismus barbatus (L.) Thell. | Poaceae | Therophyte | 4 |

| Scorzonera undulata Vahl. | Asteraceae | Geophyte | 4 |

| Senecio gallicus L. | Asteraceae | Therophyte | 1 |

| Stipa capensis Thunb. | Poaceae | Therophyte | 2 |

| Stipa lagascae Roem. & Schult. | Poaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 4 |

| Stipa parviflora Desf. | Poaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 4 |

| Stipa tenacissima L. | Poaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 3 |

| Stipagrostis ciliata (Desf.) de Winter. | Poaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 4 |

| Stipagrostis obtusa (Delile) Nees. | Poaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 4 |

| Stipagrostis plumosa (L.) Munro. | Poaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 4 |

| Stipagrostis pungens (Desf.) de Winter. | Poaceae | Hemicryptophyte | 3 |

| Suaeda vermiculata Forssk. ex J.F. Gmel. | Chenopodiaceae | Chamaephyte | 3 |

| Tamarix gallica L. | Tamaricaceae | Nanophanerophyte | 2 |

| Teucrium alopecurus De Noé | Primulaceae | Chamaephyte | 1 |

| Teucrium polium L. | Lamiaceae | Chamaephyte | 2 |

| Thesium humile Vahl, Symb. | Santalaceae | Therophyte | 1 |

| Thymelaea hirsuta (L.) Endl. | Thymelaeaceae | Chamaephyte | 0 |

| Thymelaea microphylla Coss. & Durieu. | Thymelaeaceae | Chamaephyte | 2 |

| Traganum nudatum Delile. | Chenopodiaceae | Chamaephyte | 3 |

| Tribulus terrestris L. | Zygophyllaceae | Therophyte | 1 |

| Ziziphus lotus (L.) Lam. | Rhamnaceae | Nanophanerophyte | 2 |

| Zygophyllum album L. f. | Zygophyllaceae | Chamaephyte | 0 |

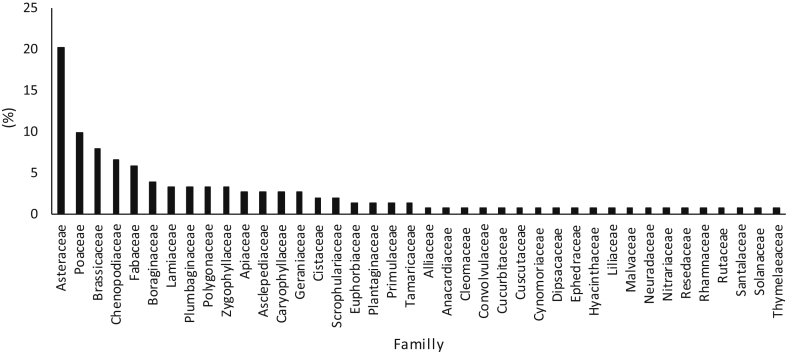

Tunisia's rangelands support 2162 species (Le Floc'h et al., 2010). In addition, rangelands in pre-Saharian Tunisia harbor a rich flora which includes about 836 species (Ferchichi, 2000). Approximately 135 of these species are specific to desert rangelands (Gamoun, 2012). Five predominant plant families, Asteraceae, Poaceae, Brassicaceae, Chenopodiaceae, and Fabaceae, represent approximately 50% of Tunisian desert flora (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Family distribution of plant species of desert rangelands of southern Tunisia (%).

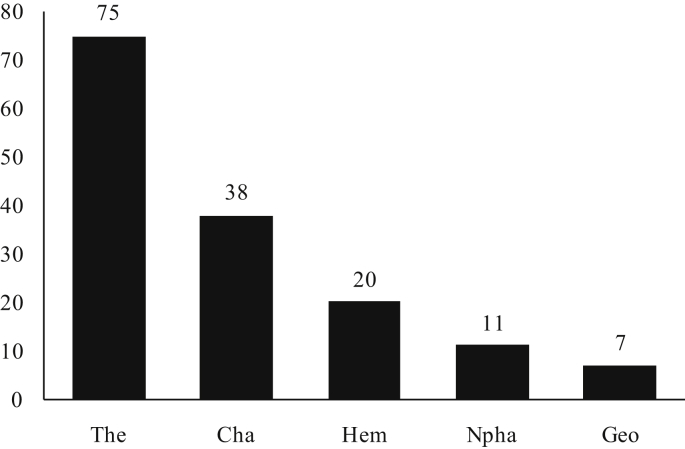

In the Tunisian desert rangelands the abundance of plant life forms includes 75 species of Therophyte (49%), 38 species of Chamaephyte (25%), 20 species of Hemicryptophyte (13%), 11 species of Nanophanerophyte (7%), 7 species of Geophytes (5%) and 2 species of Phanerophyte (1%). Anthropogenic disturbances in dry habitats have been shown to generate an increase in micro-scale species richness (Holzaphel et al., 1992). As for Therophytes, their presence may be explained in particular by the large number of micro-habitats available to annual plants that have rapid germination and growth, thus increasing their abundance (Gamoun et al., 2011, Gamoun et al., 2012). Chamaephytes are over-represented in arid rangelands because they are highly adapted to arid conditions (Raunkiaer, 1934, Orshan et al., 1984, Floret et al., 1990, Jauffret and Visser, 2003, Gamoun et al., 2012). The low abundance of Hemicryptophytes reduces competition for soil moisture to the benefit of Chamaephytes (Gamoun et al., 2011) (Fig. 6). On the other hand, the low presence of Geophytes mainly reflects the long period of drought in these arid rangelands (Gamoun et al., 2011, Gamoun et al., 2012).

Fig. 6.

Life form distribution of plant species of desert rangelands of southern Tunisia (%). The: Therophyte; Cha: Chamaephyte; Hem: Hemicryptophyte; Npha: Nanophanerophyte; Geo: Geophyte.

Grazing is not the only driver in arid ecosystems. Variable and unpredictable precipitation regimes, as well as limited soil nutrient concentrations are also major factors that determine arid ecosystem features (Noy-Meir, 1985, Walker, 1987). Gamoun et al. (2012) reported changes in the plant community composition in response to grazing and soil texture. In arid rangelands, edaphic factor availability strongly determines vegetation, and soil type has been found to limit arid plant dynamics within rangelands by affecting grazing regimes practices (Gamoun, 2012). Each soil type is characterized by specific vegetation. Range production, cover, and species richness are low and highly irregular in arid zones, and always spatially limited to sandy and gravelly soils (Gamoun, 2012). The introduction of herbivores is generally believed to reduce plant diversity. Selective grazing by livestock has been shown to negatively affect plant diversity and species composition in arid ecosystems. Heavy grazing of natural rangelands leads to loss of several highly palatable species (Louhaichi et al., 2009). However, the soil type influences the response to grazing. For example, vegetation response on sandy and gravelly soils is more diversified and more productive than on limestone and loamy soil, whereas the latter is more adapted to grazing pressure (Gamoun et al., 2011). On the whole, grazing causes a spatial homogenization of the plant community in areas dominated by Chamaephytes. Under grazed conditions, the vegetation is dominated by perennial species which are generally present in the ungrazed rangelands. These perennial species may benefit from an adaptation caused by drought and grazing (Fensham et al., 2010). The absence of perennial species such as Echiochilon fruticosum Desf., Stipa lagascae Roem. & Schult., and Stipagrostis ciliata (Desf.) de Winter. is due to their high palatability. Alternatively, perennial species may have decreased because of intensive grazing and possibly from a trampling effect from livestock in the sandy and gravelly soils of such rangelands (Gamoun et al., 2011). Otherwise, on ideal grazing land, there is a greater variety of plant species available for selective grazing and grazing animals are highly selective when given the opportunity. Thus, positive manipulation of the soil-forage plant-grazing animal complex should play a central role in any grazing management strategy for arid rangelands (Vallentine, 2001).

Few studies have evaluated the effects of controlled grazing on plant diversity in arid areas. Gamoun (2014) reported that vegetation diversity was higher in protected areas than in heavily grazed areas in the desert rangeland of southern Tunisia. In contrast, moderate grazing did not significantly affect species richness, diversity index, or species composition. In another study in the same area, Gamoun and Hanchi (2014) found that plant diversity increased as grazing intensity decreased. Ward et al. (2000) and Jauffret and Lavorel (2003), among others, have shown that palatability may play an important role in determining the effects of grazing on arid ecosystems. For these studies, however, the differences in plant diversity between the ungrazed and lightly grazed areas were small. The largest difference between the ungrazed and heavily-grazed sites was the disappearance of very palatable species under a heavy grazing treatment, including Anabasis oropediorum (Maire), Cutandia dichotoma (Forssk.) Batt. & Trab., E. fruticosum (Desf.), Helianthemum kahiricum (Delile), Helianthemum sessiliflorum (Desf.), Hippocrepis areolata Desv., Launaea nudicaulis (Linn.) Hook. f., Launaea angustifolia (Desf.) Muschl., Koelpinia linearis Pall., Polygonum equisetiforme S. & Sm., Scorzonera undulata Vahl. and S. lagascae Roem. & Schult., (Gamoun, 2014, Gamoun and Hanchi, 2014). Jauffret and Lavorel (2003) note that long-spine species such as Astragalus armatus Willd., and unpalatable, highly fibrous species such as Thymelaea hirsuta (L.) Endl., are dominant in arid Tunisian rangelands, and suggest this is a consequence of long grazing history. Similarly, unpalatable shrubs such as Haloxylon scoparium Pomel., T. hirsuta (L.) Endl., and Anabasis articulata (Forssk.) Moq., are often dominant in heavily grazed arid regions of the Middle East (Ward, 2004).

Deserts are biologically stressful environments and plants have acquired two principal strategies to cope with the harsh arid conditions and herbivory: avoidance and tolerance (Laity, 2008). These strategies allow plants to cope with heat and drought to ensure that neither internal temperatures nor tissue dehydration reach deadly levels. The majority of the flora in deserts are evaders, surviving stressful periods by living permanently or temporarily in cooler and/or moister microhabitats (Laity, 2008).

3. Conclusion

Many plants live in deserts, but it is only xerophytes that can withstand and live under long-term dry conditions. Asteraceae, Poaceae, Brassicaceae, Chenopodiaceae, and Fabaceae represent approximately 50% of Tunisian desert flora. This diversity provides many benefits that can meet the demands of both the local people for medicinal plants and fruits, as well as livestock requirements through providing forage. Mismanagement and climate change have gradually destroyed previously productive ecosystems. To reverse the degradation and desertification of these natural resources, restoration and improved management is essential.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), the Arid Regions Institute (IRA – Medenine, Tunisia) and the CGIAR Research Program on Livestock (CRP Livestock).

(Editor: Richard Corlett)

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Editorial Office of Plant Diversity.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2018.06.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Aronson J., Floret C., Le Floc'h E., Ovalle C., Pontanier R. Restoration and rehabilitation of degraded ecosystems in arid and semi-arid lands. II. Case studies in Southern Tunisia, Central Chile and Northern Cameroon. Restor. Ecol. 1993;1:168–187. [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge D.A. Island Press; Washington, DC, USA: 2007. Guide for Desert and Dryland Restoration: New Hope for Arid Lands; p. 416. [Google Scholar]

- Bendali F., Floret C., Le Floc'h E., Pontanier R. The dynamics of vegetation and sand mobility in arid regions of Tunisia. J. Arid Environ. 1990;18:21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Carney D., Farrington J. Routeldege; London: 1998. Natural Resource Management and Institutional Change; p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Casper J.K. Facts On File, Inc; 2009. Changing Ecosystems: Effects of Global Warming; p. 273. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R., Saxena N.C., Shah T. Intermediate Technology Publication; London: 1991. To the Hand of the Poor: Water and Trees; p. 273p. [Google Scholar]

- Darkoh M.B.K. The nature, causes and consequences of Desertification in the drylands of Africa. Land Degrad. Dev. 1998;9:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fensham R.J., Fairfax R.J., Dwyer J.M. Vegetation responses to the first 20 years of cattle grazing in an Australian desert. Ecology. 2010;91:681–692. doi: 10.1890/08-2356.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferchichi A. Rangelands biodiversity in presaharian Tunisia. Cah. Options Mediterr. 2000;45:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Floret C. The effects of protection on steppic vegetation in the Mediterranean arid zone of Southern Tunisia. Vegetatio. 1981;46:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Floret C., Hadjej M.S. An attempt to combat desertification in Tunisia. Ambio. 1977;6:366–368. [Google Scholar]

- Floret C., Le Floc'h E., Pontanier R., Romane F. Inst. Reg. Arides-Medenine, Dir. Ress. Eau et Sols Tunis, CEPE/CNRS Montpellier & ORSTOM; Paris, FR: 1978. Modèle écologique régional en vue de la planification et de l'aménagement agro-pastoral des régions arides. Application a la région de Zougrata; p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Floret C., Pontanier R. 1982. L'aridité en Tunisie présaharienne : Climat – sol – végétation et aménagement; p. 544. Trav. et Doc. ORSTOM, n° 150, Paris. [Google Scholar]

- Floret C., Galan M.J., Le floc’h E., Orshan G., Romane F. Growth forms and phenomorphology traits along an environmental gradient: tools for studying vegetation. J. Veg. Sci. 1990;1:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gamoun M. University of Tunis El Manar; Tunisia: 2012. The Impact of Rest from Grazing on Vegetation Dynamics: Application to Sustainable Management of Saharan Rangelands in Southern Tunisia; p. 202. PhD. thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Gamoun M. Management and resilience of Saharan rangelands: south Tunisia. Fourrages. 2013;216:321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Gamoun M. Grazing intensity effects on the vegetation in desert rangelands of Southern Tunisia. J. Arid Land. 2014;6:324–333. [Google Scholar]

- Gamoun M. Rain use efficiency, primary production and rainfall relationships in desert rangelands of Tunisia. Land Degrad. Dev. 2016;27:738–747. [Google Scholar]

- Gamoun M., Chaieb M., Ouled Belgacem A. Evolution of ecological characteristics along a gradient of soil degradation in the South Tunisian rangelands. Ecol. Mediterr. 2010;36:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gamoun M., Tarhouni M., Ouled Belgacem A., Hanchi B., Neffati M. Response of different arid rangelands to protection and drought. Arid Land Res. Manag. 2011;25:372–378. [Google Scholar]

- Gamoun M., Ouled Belgacem A., Hanchi B., Neffati M., Gillet F. Impact of grazing on the floristic diversity of arid rangelands in South Tunisia. Revue d’Écologie (Terre Vie) 2012;67:271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Gamoun M., Hanchi B. Natural vegetation cover dynamic under grazing-rotation managements in desert rangelands of Tunisia. Arid Ecosyst. 2014;4:277–284. [Google Scholar]

- Gamoun M., Essifi B., Dickens C., Hanchi B. Interactive effects of grazing and drought on desert rangelands of Tunisia. Biologija. 2016;62:105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Gondard H., Jauffret S., Aronson J., Lavorel S. Plant functional types: a promising tool for management and restoration of degraded lands. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2003;6:223–234. [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth E.G. Wiley; New York: 1987. Anatomy, Physiology and Psychology of Erosion; p. 188p. [Google Scholar]

- Harris R.B. Rangeland degradation on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau: a review of the evidence of its magnitude and causes. J. Arid Environ. 2010;74:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Holzaphel C., Schmidt W., Shmida A. Effects of human-caused distribution on the flora along a Mediterranean-desert gradient. Flora. 1992;186:261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Hudak A.T. Rangeland mismanagement in South Africa: failure to apply ecological knowledge. Hum. Ecol. 1999;27:55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez J., Martínez J., Schnabel S. Desertification due to overgrazing in a dynamic commercial livestock–grass–soil system. Ecol. Model. 2007;205:277–288. [Google Scholar]

- Jauffret S., Lavorel S. Are plant functional types relevant to describe degradation in arid, southern Tunisian steppes? J. Veg. Sci. 2003;14:399–408. [Google Scholar]

- Jauffret S., Visser M. Assigning life history traits to plant species to better qualify arid land degradation in Presaharian Tunisia. J. Arid Environ. 2003;55:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Laity J. A John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Publication; 2008. Deserts and Desert Environments; p. 357. [Google Scholar]

- Le Floc'h E., Boulos L., Véla E. 2010. Flore de Tunisie, Catalogue synonymique commenté. Tunis; p. 500. [Google Scholar]

- Le Houérou H.N. Vegetation of the Tunisian steppe (with the references to Morocco, Algeria and Libya) Ann. Inst. Natl. Rech. Agron. Tunis. (Tunisia) 1969;42(5):622. [Google Scholar]

- Le Houérou H.N. Climate change, drought and desertification. J. Arid Environ. 1996;34:133–185. [Google Scholar]

- Le Houérou H.N. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg; 2009. Bioclimatology and Biogeography of Africa; p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- Louhaichi M., Salkini A.K., Petersen S.L. Effect of small ruminant grazing on the plant community characteristics of semi-arid Mediterranean ecosystems. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2009;11:681–689. [Google Scholar]

- Nefzaoui A., Ben Salem H., El Mourid M. Innovations in small ruminants feeding systems in arid Mediterranean areas. In: Bouche R., Derkimba A., Casabianca F., editors. New Trends for Innovation in the Mediterranean Animal Production. Wageningen Academic Publishers; 2011. pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson E.S. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2011. Dryland Climatology; p. 528p. [Google Scholar]

- Noy-Meir I. Desert ecosystem structure and function. In: Evenari M., Noy-Meir I., Goodall D.W., editors. Hot Deserts and Arid Shrublands. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1985. p. 458. [Google Scholar]

- Orshan G., Montenegro G., Avila G., Aljaro M.E., Walckowiak A., Mujica A.M. Plant growth forms of Chilean matorral. A monocharacter growth form analysis along an altitudinal transect from sea level to 2000 m a.s.l. Bulletin de la Société Botanique de France. Actualités Botaniques. 1984;131:411–425. [Google Scholar]

- Ouled Belgacem A., Ben Salem H., Bouaicha A., El Mourid M. Communal rangeland rest in arid area, a tool for facing animal feed costs and drought mitigation: the case of Chenini Community, Southern Tunisia. J. Biol. Sci. 2008;8:822–825. [Google Scholar]

- Ouled Belgacem A., Tarhouni M., Louhaichi M. Effect of protection on plant community dynamics in the Mediterranean arid zone of southern Tunisia: a case study from Bou Hedma National Park. Land Degrad. Dev. 2011;24:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ouled Belgacem A., Louhaichi M. The vulnerability of native rangeland plant species to global climate change in the West Asia and North African regions. Climatic Change. 2013;119:451–463. [Google Scholar]

- Peters D.P.C., Bestelmeyer B.T., Havstad K.M., Rango A., Archer S.R., Comrie A.C., Gimblett H.R., López-Hoffman L., Sala O.E., Vivoni E.R., Brooks M.L., Brown J., Monger H.C., Goldstein J.H., Okin G.S., Tweedie C.E. Desertification of rangelands. Clim. Vulnerability. 2013;4:230–259. [Google Scholar]

- Raunkiaer C. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1934. The Life Form of Plants and Statistical Plant Geography. Collected Papers; p. 632p. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds J.F. Desertification. Encycl. Biodivers. 2013;2:479–494. [Google Scholar]

- Shachak M., Gosz J.R., Pickett S.T.A., Perevolotsky A. Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2005. Biodiversity in Drylands: toward a Unified Framework; p. p366. [Google Scholar]

- Tarhouni M., Ben Salem F., Ouled Belgacem A., Neffati M. Impact of livestock exclusion on Sidi Toui National park vegetation communities, Tunisia. Int. J. Biodivers. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Tarhouni M., Ben Hmida W., Neffati M. Long-term changes in plant life forms as a consequence of grazing exclusion under arid climatic conditions. Land Degrad. Dev. 2015;28:1199–1211. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D.S.G. third ed. A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication; 2011. Arid Zone Geomorphology: Process, Form and Change in Drylands; p. 648. [Google Scholar]

- Vallentine J.F. second ed. Academic Press; London: 2001. Grazing. Management. [Google Scholar]

- Verner D. The world bank; Washington, D.C: 2013. Tunisia in a Changing Climate: Assessment and Actions for Increased Resilience and Development; p. 184. [Google Scholar]

- Verstraete M.M., Schwartz S.A. Desertification and global change. In: Henderson-Sellers A., Pitman A.J., editors. Vegetation and Climate Interactions in Semi-arid Regions. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Belgium: 1991. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Walker B.H. A general model of savanna structure and function. In: Walker B.H., editor. Determinants of Tropical Savannas. IUBS Monograph Series No. 3. IRL Press; Oxford: 1987. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Chen F.H., Dong Z., Xia D. Evolution of the southern Mu Us desert in north China over the past 50 years: an analysis using proxies of human activity and climate parameters. Land Degrad. Dev. 2005;16:351–366. [Google Scholar]

- Ward D., Saltz D., Olsvig-Whittaker L. Distinguishing signal from noise: long-term studies of vegetation in Makhtesh Ramon erosion cirque, Negev desert, Israel. Plant Ecol. 2000;150:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ward D. The effects of grazing on plant biodiversity in arid ecosystems. In: Shachak M., Pickett S.T.A., Gosz J.R., Perevolotsky A., editors. Biodiversity in Drylands: towards a Unified Framework. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2004. pp. 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Ward D. Oxford University Press; 2016. The Biology of Deserts; p. 395. [Google Scholar]

- White R., Murray S., Rohweder M. World Resources Institute; Washington D.C: 2000. Pilot Analysis of Global Ecosystems Grassland Ecosystems. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H., Li S.G., Zhang T.H., Okhuro T., Zhou R.L. Sheep gain and species diversity in sandy grassland, Inner Mongolia. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 1994;57(2):187–190. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.