Abstract

Background

The measurements used to define pulmonary hypertension (PH) etiology, pulmonary arterial wedge pressure (PAWP), and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) vary in clinical practice. We aimed to identify clinical features associated with measurement discrepancy between PAWP and LVEDP in patients with PH.

Methods

We extracted clinical data and invasive hemodynamics from consecutive patients undergoing concurrent right and left heart catheterization at Vanderbilt University between 1998 and 2014. The primary outcome was discordance between PAWP and LVEDP in patients with PH in a logistic regression model.

Results

We identified 2,270 study subjects (median age, 63 years; 53% men). The mean difference between PAWP and LVEDP was −1.6 mm Hg (interquartile range, −15 to 12 mm Hg). The two measurements were moderately correlated by linear regression (R = 0.6, P < .001). Results were similar when restricted to patients with PH. Among patients with PH (n = 1,331), older age (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.23-2.45) was associated with PAWP underestimation in multivariate models, whereas atrial fibrillation (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.08-2.84), a history of rheumatic valve disease (OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.36-3.52), and larger left atrial diameter (OR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.24-2.32) were associated with PAWP overestimation of LVEDP. Results were similar in sensitivity analyses.

Conclusions

Clinically meaningful disagreement between PAWP and LVEDP is common. Atrial fibrillation, rheumatic valve disease, and larger left atrial diameter are associated with misclassification of PH etiology when relying on PAWP alone. These findings are important because of the fundamental differences in the treatment of precapillary and postcapillary PH.

Key Words: hemodynamics, pulmonary hypertension, right heart catheterization

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; LHC, left heart catheterization; LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; PAWP, pulmonary arterial wedge pressure; PH, pulmonary hypertension; RHC, right heart catheterization

Distinguishing precapillary and postcapillary pulmonary hypertension (PH) requires invasive hemodynamic measurements. It is important to accurately diagnose these conditions because their underlying pathophysiology and clinical management differ markedly.1, 2, 3

In clinical practice, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure (PAWP) are used as surrogates for left atrial pressure. Many clinicians rely solely on PAWP obtained during right heart catheterization (RHC) because measurement of LVEDP requires an additional procedure with arterial access.2, 3 PAWP closely approximates LVEDP in many cases, but recent literature has suggested that overreliance on this metric may misclassify PH etiology.4, 5, 6 In a large referral cohort, Halpern and Taichman7 found that nearly 50% of patients are misclassified using PAWP alone, but no demographic or clinical data were reported to help identify individuals at risk of misclassification. Mascherbauer et al8 recently reported that low diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide is a determinant of PAWP/LVEDP discordance in patients with heart failure. Other studies examining discordance between PAWP and LVEDP have been limited by small sample sizes and/or homogeneous populations.4, 5 Little is known about patient characteristics in which LVEDP and PAWP are discordant in an unselected referral population. A better understanding of these characteristics is important because it may help identify patients at risk of PH misclassification and provide guidance on which patients may benefit from measurement of LVEDP in addition to PAWP.

We sought to determine the frequency and predictors of PAWP and LVEDP discordance in a richly phenotyped cohort of unselected patients referred for simultaneous RHC and left heart catheterization (LHC).

Methods

Study Population

This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University institutional review board (No. 140544). Data for this retrospective cohort study were extracted from Vanderbilt’s Synthetic Derivative database, a deidentified version of Vanderbilt’s electronic medical record originating in 1995. The design and implementation of the Synthetic Derivative have been previously described,9, 10 and findings from this cohort have been previously reported.11, 12, 13 During the deidentification process, protected health information is removed and dates are randomly shifted up to ± 365 days while remaining internally consistent for a given patient.

Hemodynamic Data and Group Definitions

We queried the Synthetic Derivative for all patients who underwent simultaneous RHC and LHC between 1998 (when digital catheterization reports became available) and 2014. A unique algorithm using regular expressions and pattern matching was developed to extract structured, quantitative data from all catheterization reports. For this study, if a patient had multiple catheterizations or provocative testing, only resting data from the first procedure were analyzed. Inpatients and outpatients were included in this study, but patients with values suggestive of acute decompensation (eg, shock, vital signs suggesting imminent death) or cardiac-related critical illness (eg, hypertensive crisis) were excluded, as previously described.12 These patients were excluded because the intent of this study was to examine the relationship between wedge pressure and LVEDP in a more controlled setting (not during extreme critical illness) to identify predictable scenarios in which they differ. Nonphysiologic data suggestive of entry error (eg, arterial saturation > 100%, negative cardiac output) were deleted, and missing or deleted data were imputed for regression analyses (see Statistical Analysis for details). No PAWP, LVEDP, or mean pulmonary arterial pressure values were imputed.

Patients were categorized according to contemporary guidelines by the hemodynamic values on the RHC and LHC reports.1 PH was defined as a mean pulmonary arterial pressure ≥ 25 mm Hg. Precapillary and postcapillary PH were defined as mean pulmonary arterial pressure ≥ 25 mm Hg and divided into concordant (LVEDP and PAWP agree) and discordant (LVEDP and PAWP disagree) around a threshold of 15 mm Hg. Values for this study represent the computer-generated mean, which we have shown to have strong agreement with manual review in our catheterization laboratory.12

Clinical and Outcome Data

Demographic and hemodynamic data were obtained on the date of RHC. Hemodynamic variables were extracted from the catheterization report. The thermodilution method was used when cardiac output and index were reported with both Fick and thermodilution methods. Comorbidity, echocardiographic, and laboratory data were restricted to 6 months before or after RHC, and the temporally closest values were used. We defined comorbidities based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision coding or validated algorithms, as previously reported.11, 12, 14 We extracted laboratory values that reflect disease severity (brain natriuretic peptide) or comorbid conditions (glomerular filtration rate, hemoglobin A1c).

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as median, 25th percentile, and 75th percentile for continuous variables and absolute value and percentages for categorical variables, unless stated otherwise. PAWP and LVEDP relationships were assessed by scatterplot, linear prediction plot, and Bland-Altman analysis. To identify invalid data, we used histograms and cross-referenced published cohorts to evaluate outliers,15 removing values thought to be nonphysiologic. To minimize the bias associated with missing data, we imputed 20 datasets for all regression analyses using multiple imputation with additive regression, bootstrapping, and predictive mean matching.16 The variance-covariance matrix for parameter estimates was adjusted for the variability introduced by myocardial infarction. Multiple logistic regression was used to identify covariates associated with PAWP and LVEDP discordance around the threshold of 15 mm Hg. Models included only patients with hemodynamic PH for whom discrepancies between PAWP and LVEDP were most clinically meaningful. To avoid overfitting the model, we selected 10 demographic, clinical, laboratory, and hemodynamic covariates a priori. Results are reported as ORs with 95% CI and P values. We performed additional sensitivity analyses including restricting our cohort to (1) patients with PAWP or LVEDP between 13 and 17 mm Hg to identify sources of large error, which is more informative clinically; and (2) patients with pulmonary vascular resistance > 3 Wood units. Models for sensitivity analyses included fewer variables to avoid overfitting. Variables for sensitivity analyses were selected based on clinical knowledge and performance in the primary analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using R (R version 3.3.1; R Foundation) and Stata for Macintosh (Version 14.0; StataCorp).

Results

Cohort Characteristics

Among 5,797 unique patients referred for RHC, we excluded 585 individuals for incomplete data and 861 patients for prespecified exclusion criteria (Fig 1). Of the remaining 4,351 individuals, 2,270 were referred for RHC and LHC and had complete hemodynamic data, constituting our final cohort. The median age of the cohort was 63 years (interquartile range [IQR], 53-71), and 53% were men and 85% were white (Table 1). There was a high prevalence of medical comorbidities, particularly cardiovascular disease, and 42% of the cohort was obese. The most common indications for RHC (e-Table 1) were coronary artery disease (38%), valvular heart disease (18%), and congestive heart failure (16%). Compared with patients referred for RHC only, those referred for both RHC and LHC were older and had a higher prevalence of cardiopulmonary comorbidities (e-Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of final cohort. This schematic represents the initial cohort and subsequent exclusions. LHC = left heart catheterization; LVEDP = left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; mPAP = mean pulmonary arterial pressure; NoPH = no pulmonary hypertension; PA = pulmonary artery; PAWP = pulmonary artery wedge pressure; PH = pulmonary hypertension; RHC = right heart catheterization; RV = right ventricle.

Table 1.

Cohort Clinical and Hemodynamic Characteristics (N = 2,270)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, y | 62 ± 14 |

| Sex, male | 53 |

| Race | |

| White | 85 |

| Black | 11 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (n = 1,847) | 30.0 ± 7.3 |

| Comorbidities | |

| Obese | 42 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 37 |

| Coronary artery disease | 79 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 31 |

| Hypertension | 81 |

| Congenital heart disease | 13 |

| Heart failure | 43 |

| COPD | 13 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 17 |

| OSA | 10 |

| Valve disease | |

| Mitral | 49 |

| Aortic | 30 |

| Tricuspid | 15 |

| Pulmonic | 4 |

| Laboratory | |

| Brain natriuretic peptide, pg/mL (n = 1,257) | 649 ± 955 |

| Glomerular filtration rate, mL/min/1.73 m2 (n = 2,212) | 69 ± 28 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL (n = 2,213) | 13.0 ± 2.0 |

| Hemodynamics | |

| Right atrial pressure, mm Hg | 8 ± 6 |

| Pulmonary arterial systolic pressure, mm Hg | 43 ± 18 |

| Pulmonary arterial diastolic pressure, mm Hg | 18 ± 10 |

| Pulmonary arterial mean pressure, mm Hg | 27 ± 12 |

| Pulmonary arterial wedge pressure, mm Hg | 15 ± 8 |

| Cardiac index, L/min/m2 | 3.0 ± 0.9 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance, Wood units | 2.6 ± 2.3 |

| Left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, mm Hg | 16 ± 8 |

| Echocardiogram | |

| Left ventricular internal diameter at end-diastole, mm (n = 1,734) | 50 ± 11 |

| Left atrial diameter, mm (n = 1,674) | 43 ± 9 |

| Ejection fraction, % (n = 1,708) | 47 ± 16 |

| Left atrial enlargement | 55 |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 33 |

Numbers are mean ± SD or percent.

Agreement and Correlation of PAWP and LVEDP

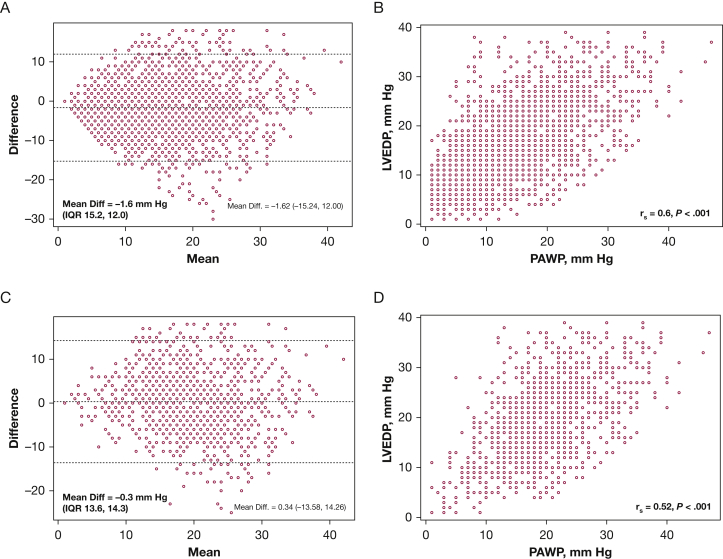

Among the 2,270 patients with both measurements, the mean difference between PAWP minus LVEDP was −1.6 mm Hg (IQR, −15 to 12 mm Hg); however, the range was wide (−18 to 30 mm Hg) (Fig 2A). The two measurements were moderately correlated by linear regression (R2 = 0.36, P < .001) (Fig 2B). PAWP tended to underestimate LVEDP at low LVEDP values and overestimate LVEDP at high LVEDP values (Fig 2B). The two variables had especially poor agreement as the mean of PAWP and LVEDP increased. In total, 42% and 64% of patients differed by > 5 mm Hg or > 20%, respectively.

Figure 2.

A-D, Agreement and correlation between pulmonary artery wedge pressure and LVEDP in the entire cohort (A and B) and those with pulmonary hypertension (C and D). Diff = difference; IQR = interquartile range. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviation.

Among individuals with hemodynamic PH (n = 1,331), the mean difference between PAWP and LVEDP was 0.3 mm Hg (IQR, −14 to 14 mm Hg), with a range of −18 to 25 mm Hg. The measurements were less correlated than the cohort as a whole (R2 = 0.27, P < .001) and also showed especially poor agreement at higher mean values (Figs 2C, 2D).

Concordance of PAWP and LVEDP in Diagnosing Precapillary and Postcapillary PH

Consensus guidelines recommend the use of a PAWP or LVEDP > 15 mm Hg to classify a patient as having postcapillary PH and PAWP or LVEDP ≤ 15 mm Hg to diagnose precapillary PH. In the 1,331 patients with PH, 138 patients (11%) and 220 patients (17%) would be misclassified as Precapillary and postcapillary PH, respectively, when left atrial pressure was assessed with PAWP instead of LVEDP (Table 2). In unadjusted group comparisons, patients in whom the wedge overestimated LVEDP (PAWP > 15 mm Hg, LVEDP ≤ 15 mm Hg) were older, had more left ventricular remodeling on echocardiography, and higher v waves compared with patients with concordant precapillary PH. Moreover, 49% of patients in whom the wedge pressure was overestimated had LVEDP values between 13 and 15 mm Hg. Patients in whom the wedge underestimated LVEDP (PAWP < 15 mm Hg, LVEDP ≥ 15 mm Hg) had more favorable hemodynamics (lower right atrial pressure and higher cardiac index) compared with patients with concordant postcapillary PH, but clinical characteristics were similar between the two groups.

Table 2.

Clinical and Hemodynamic Comparisons of Patients With Pulmonary Hypertension Based on Hemodynamic Classification

| Variable | Wedge/LVEDP Concordant |

Wedge/LVEDP Discordant |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precapillary PH |

Postcapillary PH |

Wedge Overestimation of LVEDP |

Wedge Underestimation of LVEDP |

|

| (PAWP and LVEDP ≤ 15 mm Hg) | (PAWP and LVEDP > 15 mm Hg) | (PAWP > 15 mm Hg, LVEDP ≤ 15 mm Hg) | (PAWP ≤ 15 mm Hg, LVEDP > 15 mm Hg) | |

| No. (%) | 206 (17) | 668 (55) | 201 (17) | 138 (11) |

| Age, y | 60 ± 14 | 62 ± 13 | 65 ± 14a | 63 ± 13 |

| Sex, female | 56 | 43 | 56 | 51 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29 ± 7 | 32 ± 8 | 29 ± 8 | 31 ± 8 |

| RAP, mm Hg | 7 ± 4 | 13 ± 6 | 10 ± 5a | 8 ± 4b |

| mPAP, mm Hg | 36 ± 13 | 37 ± 9 | 34 ± 8 | 30 ± 7 |

| PAWPv, mm Hg | 13 ± 5 | 28 ± 9 | 26 ± 8 | 15 ± 4 |

| PAWP, mm Hg | 11 ± 4 | 24 ± 6 | 20 ± 4 | 13 ± 2 |

| LVEDP, mm Hg | 10 ± 4 | 24 ± 6 | 12 ± 3 | 21 ± 5 |

| PVR, WU | 5.5 ± 4.7 | 2.9 ± 1.8 | 3.3 ± 2.5a | 3.4 ± 1.9b |

| Cardiac index, mL/min/m2 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 2.8 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 3.0 ± 0.9b |

| LVH | 36 | 52 | 54a | 54 |

| IVSD, cm | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| LVEDD, mm | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 5.2 ± 1.1 | 5.0 ± 1.1a | 5.0 ± 1.1b |

| LA diameter, mm | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 4.8 ± 0.9a | 4.2 ± 0.7b |

| BNP, pg/mL | 573 ± 910 | 818 ± 1,051 | 875 ± 1,041a | 878 ± 1,218 |

| GFR, mL/min | 73 ± 29 | 65 ± 30 | 61 ± 25a | 69 ± 31 |

| Diabetes | 30 | 51 | 34 | 42 |

| HTN | 72 | 87 | 81a | 83 |

| CAD | 67 | 85 | 79a | 88 |

| AF | 27 | 40 | 57a | 20b |

| COPD | 21 | 13 | 14 | 17 |

Numbers are mean ± SD, percent, or as otherwise indicated. AF = atrial fibrillation; BNP = brain natriuretic peptide; CAD = coronary artery disease; GFR = glomerular filtration rate per 1.73 m2; HTN = hypertension; IVSD = interventricular septal dimension; LA = left atrium; LVEDD = left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVEDP = left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; LVH = left ventricular hypertrophy; mPAP = mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PAWP = pulmonary arterial wedge pressure; PAWPv = v wave of pulmonary arterial wedge pressure tracing; PH = pulmonary hypertension; PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP = right atrial pressure; WU = Wood unit.

P < .05 for wedge overestimation of LVEDP vs precapillary PH.

P < .05 for wedge underestimation of LVEDP vs postcapillary PH.

We performed multivariate logistic regression to identify clinical features associated with misclassification of PH etiology, building separate models for PAWP over- and underestimation of LVEDP (Table 3). These models included only individuals with PH because accurate estimation of left ventricular filling pressure is most clinically important in that subgroup. Older age (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.23-2.45) was associated with PAWP underestimation in multivariate models. Atrial fibrillation (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.08-2.84), a history of rheumatic valve disease (OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.36-3.52), and larger left atrial diameter (OR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.24-2.32) were associated with PAWP overestimation of LVEDP. Higher BMI was associated with protection against PAWP overestimation of LVEDP (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.35-0.92).

Table 3.

Association between Clinical Variables and PAWP/LVEDP Discrepancy at a Threshold of 15 mm Hg

| Variable | PAWP Underestimation of LVEDP |

PAWP Overestimation of LVEDP |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORa | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CI | |

| Age | 1.77b | 1.28-2.45 | 1.01 | 0.73-1.41 |

| Sex (M:F) | 0.86 | 0.55-1.36 | 0.57b | 0.35-0.92 |

| BMI | 1.01 | 0.75-1.36 | 0.64b | 0.45-0.90 |

| AF | 0.46b | 0.28-0.78 | 1.75b | 1.08-2.84 |

| COPD | 0.98 | 0.56-1.71 | 1.19 | 0.64-2.19 |

| OSA | 0.95 | 0.48-1.90 | 0.81 | 0.36-1.84 |

| Hypertension | 1.19 | 0.67-2.10 | 0.90 | 0.47-1.73 |

| Hemoglobin | 1.31 | 0.96-1.80 | 1.24 | 0.90-1.71 |

| Rheumatic valve disease | 0.60b | 0.37-0.98 | 2.19b | 1.36-3.52 |

| Left atrial diameter | 0.69b | 0.47-1.00 | 1.70b | 1.24-2.32 |

F = female; M, male. See Table 2 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Effect sizes for continuous variables represent the difference between the 25th and 75th percentiles.

P < .05.

Sensitivity Analysis

Modest discrepancies between PAWP and LVEDP may not be clinically meaningful. Therefore, in sensitivity analyses, we excluded subjects with PAWP or LVEDP between 13 and 17 mm Hg to identify clinical features that may alter a subject’s hemodynamic diagnosis and therapeutic approach. In this model (n = 721) (e-Table 3), atrial fibrillation, rheumatic valve disease, and larger left atrial diameter remained strong predictors of PAWP overestimation of LVEDP. Finally, when restricting the cohort to patients with pulmonary vascular resistance > 3 Wood units and PAWP or LVEDP values outside the range 13 to 17 mm Hg (n = 483) (e-Table 4), older age was associated with PAWP underestimation and atrial fibrillation, rheumatic valve disease, and larger left atrial diameter remained associated with PAWP overestimation.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to identify clinical features associated with PH misclassification arising from discrepancy between the PAWP and the gold standard surrogate, LVEDP. Although PAWP/LVEDP discrepancies are well described, patient characteristics associated with PAWP/LVEDP disagreement have not been examined in large, well-phenotyped cohorts. The mean disagreement between PAWP and LVEDP was modest in our cohort (1.6 mm Hg); however, the range of disagreement was wide and misclassification of PH etiology would have occurred in nearly 30% of patients if RHC alone were performed. Importantly, features associated with misclassification of precapillary or postcapillary PH were consistent when subjects with values near 15 mm Hg and low pulmonary vascular resistance were excluded. Older age was associated with wedge underestimation of LVEDP, whereas wedge overestimation of LVEDP was more likely to be observed in patients with atrial fibrillation, a diagnosis of rheumatic valve disease, and larger left atrial diameter. These findings are important to patients and their providers because they provide insight into risk factors for PH etiology misdiagnosis.

Prior work has confirmed that discrepancies between PAWP and LVEDP are common in clinical practice. Using a large hemodynamic registry (N = 11,523), Halpern and Taichman7 observed that PAWP/LVEDP discrepancies around the 15 mm Hg threshold are common and are likely to lead to misdiagnosis in a substantial proportion of patients, including over one-half of individuals with pulmonary arterial hypertension based on PAWP measurement alone. Bitar et al5 made a similar observation in a cohort of 101 US veterans as did Oliveira et al4 in 122 subjects with suspected PH. More recently, Mascherbauer et al8 examined pulmonary function test parameters associated with PAWP/LVEDP gradient in 173 subjects with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Lower diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide was associated with a higher gradient using stepwise multivariate linear regression. This study highlights a group at risk of PAWP/LVEDP discrepancy; however, pulmonary function parameters are not available in many patients referred for catheterization. These studies bring important awareness to clinically meaningful measurement discrepancies but are limited by lack of rich demographic and clinical information to ascertain which patients are at risk of PH misclassification.4, 5, 7 Although discrepancies may be attributable in part to unique physiologic mechanisms (eg, atrial fibrillation), human error also likely contributes. We observed that PAWP and LVEDP differed by at least 20% in nearly two-thirds of our cohort, which is difficult to blame solely on physiology. These measurements require meticulous attention to waveforms, timing, and zeroing practices, among other considerations. We were unable to assess variability in discrepant measurements across operators, but this is an important consideration for future studies and in the interpretation of hemodynamic data in clinical practice.

We identified several important associations that may assist clinicians in the decision of whether or not to refer for concurrent LVEDP measurement. Older age was associated with PAWP underestimation of LVEDP in our primary analysis, but did not remain significant when borderline values were excluded. The mechanism for how PAWP underestimates LVEDP with increasing age is unclear, but the observation is consistent with the current understanding of PH epidemiology and our prior report that group II PH is the predominant PH phenotype in older adults.17 In our cohort, atrial fibrillation and presence of an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision code for rheumatic valvular disease were consistently associated with higher PAWP than LVEDP. These observations may reflect a true difference between left atrial and left ventricular diastolic pressures based on the unique physiology of these conditions. In rheumatic mitral valve disease, atrial and ventricular pressures are dissociated because of a stenotic valve, but elevated left atrium pressure is transmitted to the pulmonary vasculature.

Our data confirm prior studies reporting that PAWP is often higher than LVEDP in patients with atrial fibrillation at the time of RHC.18, 19 These results reflect the physiology of atrial fibrillation (reduced atrial compliance and impaired transport function) but are also strongly influenced by measurement technique.20, 21, 22, 23 Our dataset reports computer-generated mean pressures, which are averaged over the cardiac cycle and therefore include contributions of the v wave. This may elevate PAWP compared with LVEDP, which is an end-diastolic measure only. The relative contribution of the v wave to the computer-generated mean pressure is exaggerated in atrial fibrillation because the a wave is absent.24 Our study confirms the importance of recognizing this phenomenon in clinical practice because 31% of our cohort had a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.

As pointed out by others, the clinical utility of PAWP and LVEDP depends on the clinical scenario and the question being asked.21, 23 The observation that PAWP overestimates LVEDP as left atrial diameter increases reflects adverse atrial remodeling in response to chronically elevated left ventricular filling pressure. This also raises the notion that PAWP better reflects pressure transmitted to the pulmonary circulation and is likely the more informative measurement when assessing the symptomatic patient. Recent data from Mascherbauer et al8 support this notion by showing that PAWP is more strongly associated with outcomes in patients with heart failure. Further studies are warranted examining the prognostic associations of PAWP and LVEDP in a larger, unselected population.

We did not observe expected PAWP/LVEDP discrepancies in subjects with COPD or interstitial lung disease, which may lead to intrapleural pressure changes that dissociate PAWP and LVEDP.25, 26 A potential explanation—in addition to a true finding—is that our dataset uses the computer-generated mean for PAWP and LVEDP measurements. We did observe, in both primary and sensitivity analyses, that higher BMI was associated with PAWP overestimation of LVEDP. A potential mechanism for this observation is that obesity increases pleural pressure,26 which may compress the thin-walled atrium (increasing pressure), but not the thicker left ventricle; however, this is speculation.

These data should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Vanderbilt University is a referral center for both complex cardiovascular disease and pulmonary vascular disease, making these conditions overrepresented in our cohort compared with the general population. Our PAWP and LVEDP measurements were extracted directly from the medical record, not through manual review of hemodynamic tracings. In prior work, we have demonstrated generally good correlation between manual reading and computer interpretations within this electronic medical record-based cohort.12 We examined only clinical data that are routinely available in patients referred for RHC, including echocardiographic parameters of cardiac structure and function. It is likely that additional end points, including pulmonary function test parameters, would have provided additional insight, but those data were not available in our cohort.

Conclusions

This study identified clinical scenarios in which clinicians should consider the addition of LVEDP measurement to standard RHC measurements in patients at risk of PH. These findings are important because of the fundamental differences in the pathophysiology and treatment of pre- and postcapillary PH.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: E. L. B. is the guarantor and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work. A. R. H. and T. R. A. helped with study design, collected and analyzed the data, performed statistical analysis, and revised drafts of the manuscript. A. R. O. helped with study design and revised drafts of the manuscript. M. X. helped with study design and collected and analyzed the data. L. N. D. helped with study design and revised drafts of the manuscript. E. F. E. and Q. S. W. helped with study design and collection of the data. E. L. B. helped with study design, collected and analyzed the data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote initial and final drafts of the manuscript. All authors approved the final submitted version of the manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: A. R. H. reported serving as a consultant for Pfizer, United Therapeutics, Bayer, and Actelion; and has received research support from United Therapeutics to study pulmonary hypertension. None declared (A. R. O., T. R. A., M. X., L. N. D., E. F. E., Q. S. W., E. L. B.).

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information: The e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health [Grant U01 HL125212-01 to A. R. H.], the American Heart Association [Grant 13FTF16070002 to E. L. B.], and the Gilead Scholars Program in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension [E. L. B.]. The dataset(s) used for the analyses described were obtained from Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Synthetic Derivative, which is supported by institutional funding and by the Clinical and Translational Science Award [Grant UL1TR000445] from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/National Institutes of Health.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Hoeper M.M., Bogaard H.J., Condliffe R. Definitions and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 suppl):D42–D50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vachiery J.L., Adir Y., Barberà J.A. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 suppl):D100–D108. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simonneau G., Galiè N., Rubin L.J. Clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(12 suppl S):5S–12S. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliveira R.K., Ferreira E.V., Ramos R.P. Usefulness of pulmonary capillary wedge pressure as a correlate of left ventricular filling pressures in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(2):157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bitar A., Selej M., Bolad I., Lahm T. Poor agreement between pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure in a veteran population. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LeVarge B.L., Pomerantsev E., Channick R.N. Reliance on end-expiratory wedge pressure leads to misclassification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):425–434. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00209313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halpern S.D., Taichman D.B. Misclassification of pulmonary hypertension due to reliance on pulmonary capillary wedge pressure rather than left ventricular end-diastolic pressure. Chest. 2009;136(1):37–43. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mascherbauer J., Zotter-Tufaro C., Duca F. Wedge pressure rather than left ventricular end-diastolic pressure predicts outcome in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(11):795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roden D.M., Pulley J.M., Basford M.A. Development of a large-scale de-identified DNA biobank to enable personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84(3):362–369. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pulley J., Clayton E., Bernard G.R., Roden D.M., Masys D.R. Principles of human subjects protections applied in an opt-out, de-identified biobank. Clin Transl Sci. 2010;3(1):42–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2010.00175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assad T.R., Hemnes A.R., Larkin E.K. Clinical and biological insights into combined post- and pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(23):2525–2536. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.09.942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Assad T.R., Brittain E.L., Wells Q.S. Hemodynamic evidence of vascular remodeling in combined post- and precapillary pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2016;6(3):313–321. doi: 10.1086/688516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assad T.R., Maron B.A., Robbins I.M. Prognostic effect and longitudinal hemodynamic assessment of borderline pulmonary hypertension. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(12):1361–1368. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.3882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottesman O., Kuivaniemi H., Tromp G. The Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) Network: past, present, and future. Genet Med. 2013;15(10):761–771. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robbins I.M., Hemnes A.R., Pugh M.E. High prevalence of occult pulmonary venous hypertension revealed by fluid challenge in pulmonary hypertension. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7(1):116–122. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schafer J.L., Graham J.W. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(2):147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pugh M.E., Sivarajan L., Wang L., Robbins I.M., Newman J.H., Hemnes A.R. Causes of pulmonary hypertension in the elderly. Chest. 2014;146(1):159–166. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickinson M.G., Lam C.S., Rienstra M. Atrial fibrillation modifies the association between pulmonary artery wedge pressure and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(11):1483–1490. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaye D.M., Silvestry F.E., Gustafsson F. Impact of atrial fibrillation on rest and exercise haemodynamics in heart failure with mid-range and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(12):1690–1697. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramu B., Houston B.A., Tedford R.J. Pulmonary vascular disease: hemodynamic assessment and treatment selection-focus on Group II pulmonary hypertension. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2018;15(2):81–93. doi: 10.1007/s11897-018-0377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy Y.N., El-Sabbagh A., Nishimura R.A. Comparing pulmonary arterial wedge pressure and left ventricular end diastolic pressure for assessment of left-sided filling pressures. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(6):453–454. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright S.P., Moayedi Y., Foroutan F. Diastolic pressure difference to classify pulmonary hypertension in the assessment of heart transplant candidates. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10(9):e004077. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Houston B.A., Tedford R.J. What we talk about when we talk about the wedge pressure. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10(9):e004450. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Houston B.A., Tedford R.J. Is pulmonary artery wedge pressure a Fib in A-Fib? Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(11):1491–1494. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice D.L., Awe R.J., Gaasch W.H., Alexander J.K., Jenkins D.E. Wedge pressure measurement in obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest. 1974;66(6):628–632. doi: 10.1378/chest.66.6.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Behazin N., Jones S.B., Cohen R.I., Loring S.H. Respiratory restriction and elevated pleural and esophageal pressures in morbid obesity. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(1):212–218. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91356.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.