Abstract

Gender roles depend on the attitudes and beliefs about them, which at the same time facilitate the formation of stereotypes that will foster violence in interpersonal relationships in couples. The assessment tools used tend to represent the sexist attitude towards women, without taking into account that men can also be recipients of the same behavior from their partner. The objective of the study is to provide an improved scale for the assessment of gender role attitudes, based on the theoretical perspective of gender equality. The sample comprises 2,136 young Spanish men and women, students in Vocational Training (Spanish acronym FP) and at university in the age range 15-26 years old. The results show the existence of a single bipolar factor - transcendent attitudes vs. sexist attitudes - fulfilling psychometric fit indices, and providing the basis for modifying attitudes depending on the difficulty of the items for such modification. The implications for intervention are oriented based on the perspective of prevention and changing sexist gender attitudes.

KEYWORDS: Attitudes, Role, Evaluation, Sexism, Instrumental study

Resumen

Los roles de género dependen de las actitudes y creencias acerca de los mismos, lo que al mismo tiempo facilita la formación de estereotipos que favorecerán la violencia en las relaciones interpersonales de pareja. Los instrumentos de evaluación utilizados tienden a representar la actitud sexista hacia las mujeres sin tener presente que los hombres pueden ser también receptores del mismo comportamiento por parte de su pareja. El objetivo del estudio es crear una escala mejorada para la evaluación de las actitudes de rol de género, tomando como base la perspectiva teórica de la igualdad de género. La muestra está formada por 2.136 jóvenes españoles de ambos sexos, estudiantes de Formación Profesional (FP) y Universitarios, cuyas edades están en el rango de 15 a 26 años. Los resultados muestran la existencia de un único factor bipolar -actitudes trascendentes vs. actitudes sexistas- cumpliendo los índices de ajuste psicométricos, y ofreciendo las bases de la modificación de las actitudes en función de la dificultad de los ítems para dicho cambio. Las implicaciones para la intervención se orientan en base a la perspectiva de la prevención y el cambio de actitudes sexistas de género.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Actitudes, rol, evaluación, sexismo, estudio instrumental

Beliefs or attitudes are among the factors that have a bearing on violent conduct of any type in affective interpersonal relationships in couples. Attitudes facilitate the appearance of gender roles that assign the roles and responsibilities that men and women have in society; they are based on beliefs and opinions that facilitate a stereotyped view and thus encourage discrimination (Ferrer et al., 2006, López-Cepero et al., 2013). In turn, these gender roles demonstrate their differential effect through variables such as age, sex or level of education (Díaz and Sellami, 2014, Ferrer et al., 2006).

Traditional gender roles involve the allocation of tasks differentiated by sex, mirroring the inequality between males and females taken on by them in the social context. This fact is linked not only to possible violence directed at the partner within affective relationships, but also encourages the justification of abusive behavior. Along the same lines hostile sexism, characterized by distrust and adversarial feelings towards the partner, legitimizes the abuse of women, approving its practice and at the same time placing the blame for this conflict situation on their shoulders (Herrera et al., 2012, Lila et al., 2013, Lila et al., 2014). It is possible that this has a bearing on the labeling of the very situations experienced in affective relationships, offering a perception of their consideration as abuse independently of recognizing specific behavior as abusive (Cortés et al., 2014, López-Cepero et al., in press). In turn, women's behavior as regards their partner status in affective relationships will influence the attitudes or perceptions of others. Herrera et al. (2012) state that when women do not accept their partner's decisions they are assessed more negatively, particularly by men with a traditional sexist attitude.

This reality leads to an assessment of sexist attitudes based on the assumption that they have taken shape in a single direction, i.e. the assessment of discriminatory attitudes towards a feminine gender role. Examples of such scales are, amongst others: Hostility Towards Women Scales (Check, Malamuth, Elias, & Barton, 1985), Gender Role Conflict Scale (O’Neil, Helms, Gable, David, & Wrightsman, 1986), Adversarial Heterosexual Beliefs Scale (Lonsway & Fitzgerald, 1995), Rape Myth Acceptance Scale (Burt, 1980), and the Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale (Payne, Lonsway, & Fitzgerald, 1999), these latter focusing particularly on sexual aggression and its acceptance. It is true that the literature reports extensive information on discrimination against women, but we must not overlook the fact that although there is less research in this area, women can also have sexist attitudes towards men, i.e. attitudes based on hostility towards their partner or on traditional beliefs that take shape through roles allocated by gender or even sex (Rodríguez Castro et al., 2010, Swim and Hyers, 1999, Travaglia et al., 2009).

Similarly, we must not overlook that in contrast to sexist attitudes towards role, there are also transcendent attitudes that must be assessed as defenders of equality from an egalitarian perspective (Baber and Tucker, 2006, López-Cepero et al., 2013). Other instruments that aim to measure inequality between men and women are the Attitudes Toward Men Inventory (AMI; Glick & Fiske, 1999) and the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI) (Glick & Fiske, 1996), this inequality being able to be expressed in a hostile or benevolent manner. In contrast, there is an instrument which in addition to measuring inequality also assesses equality between sexes, defining an attitudinal typology based on role characteristics: the Social Roles Questionnaire (SRQ-R; Baber & Tucker, 2006), assessing sexist and egalitarian attitudes and pointing out that both sexes can equally be recipients. The differences in each type of attitude must be emphasized, since the literature has highlighted the possible relationship between these attitudes and a higher or lower tolerance of potential abuse situations (Rodríguez-Franco, Antuña, López-Cepero, Rodríguez-Díaz, & Bringas, 2012). This leads us to propose as an objective the preparation of a new scale for the assessment of gender role attitudes using the approaches offered by the theoretical perspective of gender equality, having an effect on the contribution of how sexist attitudes may be modified.

Method

Participants

The sample is made up of 2,136 young Spanish people aged 15 to 26 years old (M= 19.43; SD= 1.98) who have had a dating relationship lasting at least one month. Distribution by sex is 838 males (39.2%) and 1,298 females (60.8%), by educational level, students in Vocational Training (n= 1,225) 57.4%, within which 635 males (51.8%) and 590 females (48.2%), and university students (n= 911) 42.6%, within which 203 males (22.3%) and 708 females (77.7%). The low level of employment among the sample is to be noted: 88 males and 129 females are in employment (10.7% and 10.1%, respectively), by educational level there are 115 FP students (9.6%) and 102 university students (11.2%) in paid employment.

Instruments

Initial assessment was by an ad hoc sociodemographic questionnaire which gathered relevant personal data for the research: age, sex, educational level and academic year (Rodríguez-Franco et al., 2010). The starting point for the Gender Role Attitudes Scale (GRAS) was to select a set of items described as indicators of sexism by young victims in dating relationships; unanimous statements of identification functions - egalitarian and/or expressing a sexist function in the relationship - for their aggressors. The study participants have identified 20 items out of a total of 50 - taken mainly from those used in the Social Role Questionnaire (SRQ-R; Baber & Tucker, 2006), the Inventario de Pensamientos Distorsionados sobre la Mujer [Inventory of Distorted Thinking about Women] (PDM; Echeburúa & Fernández-Montalvo, 1998), the scale of Ideología de Rol de Género [Gender Role Ideology] (EIG; Moya, Expósito, & Padilla, 2006) and the Escala de Actitudes del Alumno hacia la Coeducación [Scale of Student Attitudes to Coeducation] (SDG; García-Pérez et al., 2010) -making changes to the formulation of the items. These items reflect attitudes which identify the gender role to be played in society as regards equality (e.g. “People should be treated equally, regardless of their sex”) or sexism in social functions (e.g. “I think it is worse for a man to cry than for a woman”), employment (e.g. “Only some kinds of job are equally appropriate for men and women”) and family (e.g. “Mothers should make most of the decisions about how to bring up their children”). The attitudes scale offers five answer options, graded using a Likert scale from 1 to 5, where 1 is (Totally agree) and 5 is (Totally disagree). See Appendix 1.

Data analysis

The items discrimination study is carried out using the corrected item-test correlation (Moreno, Martínez, García-Cueto, Fidalgo de las Heras, & Muñiz, 2005), whilst reliability is calculated using Cronbach's alpha coefficient for ordinal data (Elosua & Zumbo, 2008) and the score normality study using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test. Establishing validity evidence is carried out by randomly dividing the sample into three approximately equal groups of 702, 740 and 694 participants respectively. The first of these has been used to undertake an exploratory factor analysis. Used as input is the matrix of polychoric correlations between items; the pertinence of performing factor analysis on data is calculated using Bartlett's test index and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test, the extraction method being unweighted least squares. The number of factors is determined by Optimal Implementation of Parallel Analysis (PA) (Timmerman & Lorenzo-Seva, 2011) with 10,000 resampling operations, the goodness-of-fit of the data to the model is established through percentage of total variance explained by the factors, the goodness-of-fit index (GFI) and Root Mean Square of Residuals (RMSR) (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2006). The other two random groups permit performance of a confirmatory factor analysis using the cross-validity method in order to take modeling error correlations in the first sample into account and keep them in the second sample to find the best fit; the factor extraction method used was robust maximum likelihood on a matrix of polychoric correlations, data fit to model established by χ2/g.l., the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Root Mean Square of Residuals (RMSR) (Kline, 2005).

Subsequently, and in order to have evidence of the accuracy of measurement and the possibility of some indication of the viability of changing attitudes towards gender role, the data are analyzed using IRT hypotheses (Samejima's graded response model). The graded response model is a particular instance of the 2-parameter logistic model (Samejima, 1969), which through the results offers: 1) information on test measurement accuracy for participant scores across all the latent continuous variables (θ) being studied using the test information function; 2) the discriminatory capacity of each item in the score calculation for each person in the variable. Value of parameter a of the model; 3) the value of parameter b indicates, for a given level of the variable measured, the likelihood of choosing a specific response category or a higher one. Specifically, Samejima (1969) used a cumulative process in which the characteristic curve for category “k” indicates the likelihood of reaching this category or the next ones, dependent on the location of the subject in the trait (P(Xi≥ k |θ); therefore, a possible interpretation applied depends on the values taken on by this parameter thus revealing which items/traits it would be “easier” to intervene on in order to modify this aspect. The traits easiest to modify will be those for which the difference between b4–b1 is lower, so lower values indicate greater ease for making this change.

Lastly, a differential analysis of the sample is undertaken, both by sex and by educational level, for which the Mann-Whitney U test has been used, at the same time as grading the data on a T-score scale (M = 50, SD = 10).

Data analysis is carried out using SPSS 19.0, FACTOR 9.2, Mplus 6.12 and MULTILOG 7.03.

Results

The items discrimination index (corrected item-test correlation) ranges between .92 and .39, i.e. all are within acceptable values. The test is highly reliable, with an alpha coefficient of .99. In turn, the results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test do not permit the univariate normality hypothesis to be maintained either for item scores or total scale score.

The results of the exploratory factor analysis using the Parallel Analysis carried out recommend the extraction of a single factor, both Bartlett's test statistics (13104.9 -g.l. = 190, p = .000010-) and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test (0.97) indicating that the data meet the correct conditions for undergoing factor analysis as regards item intercorrelations; the total variance percentage explained by the factor (67.5%) and the values of both GFI (.999) and RMSR (.048) show a good fit of data in a one-dimensional model.

The confirmatory factor analysis carried out with each of the remaining random samples enables us to confirm that the values obtained indicate excellent goodness-of-fit of the data to the one-dimensional model (Table 1).

Table 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis fit index.

| Sample 2 (n = 740) | Sample 3 (n = 694) | |

|---|---|---|

| RMSEA | .053 | .055 |

| CFI | .969 | .969 |

| SRMR | .045 | .034 |

Using the complete sample, the factor weights of each one of the variables were calculated. The results show very high factor weights of the factor items, ranging from .45 to .98 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factor weights of each of the items in the transcendent vs. sexism gender role attitude bipolar factor.

| Items | Factor weights | Items | Factor weights |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | .68 | 11 | .91 |

| 2 | .94 | 12 | .91 |

| 3 | .84 | 13 | .80 |

| 4 | .94 | 14 | .96 |

| 5 | .86 | 15 | .44 |

| 6 | .86 | 16 | .56 |

| 7 | .62 | 17 | .58 |

| 8 | .97 | 18 | .74 |

| 9 | .94 | 19 | .64 |

| 10 | .91 | 20 | .89 |

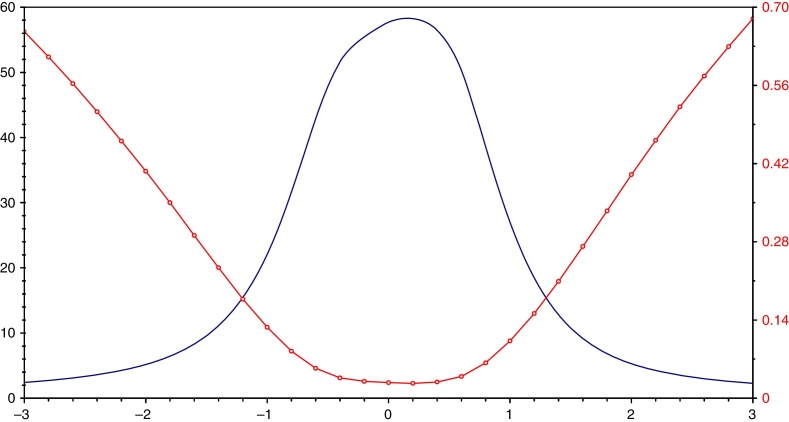

On the other hand, data analysis by ITR using Samejima's graded response model produces the Test Characteristic Curve (TCC) where the unbroken line is the information function and the dotted line is typical measurement error. The x-axis represents score in the variable studied. In this way and as can be seen, the test is more accurate, with greater information and lower typical error for the central values of the variable (see Figure 1). Likewise, the results shown in Table 3 reveal that the idea most easy to change would be “People should be treated equally, regardless of their sex” (item 2) and the most stubbornly held and hardest to change and intervene on would be “I think it is right that in my circles of friends, my future domestic activity is considered more important than my professional activity” (item 14).

Figure 1.

Item information function.

Table 3.

Parameters a and b of IRT.

| a | b1 | b2 | b3 | b4 | B4–b1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 1.36991 | -1.07325 | -0.21389 | 0.34558 | 1.1924 | 2.26565 |

| Item 2 | 3.72031 | -0.08025 | 0.17132 | 0.25014 | 0.42775 | 0.508 |

| Item 3 | 2.38667 | -0.69709 | -0.11694 | 0.23921 | 0.76675 | 1.46384 |

| Item 4 | 4.01777 | -0.31007 | 0.09629 | 0.22963 | 0.4864 | 0.79647 |

| Item 5 | 2.68059 | -0.47539 | -0.06124 | 0.16072 | 0.45724 | 0.93263 |

| Item 6 | 2.64285 | -0.65041 | -0.04473 | 0.28362 | 0.75836 | 1.40877 |

| Item 7 | 1.32302 | -1.52765 | -0.41346 | 0.23908 | 1.24827 | 2.77592 |

| Item 8 | 5.90929 | -0.34766 | 0.00874 | 0.2038 | 0.48051 | 0.82817 |

| Item 9 | 4.20431 | -0.48493 | -0.0753 | 0.25774 | 0.58006 | 1.06499 |

| Item 10 | 3.25398 | -0.5872 | -0.09205 | 0.25975 | 0.71086 | 1.29806 |

| Item 11 | 3.41359 | -0.54328 | -0.06917 | 0.22506 | 0.67992 | 1.2232 |

| Item 12 | 4.94607 | -0.5249 | -0.07064 | 0.20622 | 0.55144 | 1.07634 |

| Item 13 | 3.19205 | -0.49083 | -0.04626 | 0.2795 | 0.69061 | 1.18144 |

| Item 14 | 0.81575 | -2.90303 | -1.31193 | 0.52083 | 2.05563 | 4.95866 |

| Item 15 | 1.07494 | -2.23988 | -0.99342 | 0.64453 | 2.03316 | 4.27304 |

| Item 16 | 1.11501 | -1.69191 | -0.68638 | 0.40014 | 1.59072 | 3.28263 |

| Item 17 | 1.73942 | -1.02961 | -0.29231 | 0.28892 | 0.92026 | 1.94987 |

| Item 18 | 2.09579 | -1.15711 | -0.39673 | 0.34092 | 1.13044 | 2.28755 |

| Item 19 | 1.33572 | -1.60666 | -0.62556 | 0.37871 | 1.49916 | 3.10582 |

| Item 20 | 2.82315 | -0.82244 | -0.33483 | 0.20289 | 0.76698 | 1.58942 |

Lastly, interindividual differential analysis using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test will show statistically significant differences depending on the educational level of study participants - university vs. Vocational Training - (p<.001), with a value of Z= -30.16, and between males and females (p=.014), with a value of Z= -2.46. The grading can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Grading of Gender Role Attitudes Scale by sex on T-score scale (M = 50, SD = 10) and centiles.

| Males | Females | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | T | C | PD | T | C | PD | T | C | PD | T | C |

| 20 | 30 | 1 | 61 | 54 | 72 | 20 | 36 | 1 | 61 | 50 | 52 |

| 21 | 31 | 1 | 62 | 54 | 73 | 21 | 36 | 1 | 62 | 50 | 52 |

| 22 | 31 | 1 | 63 | 55 | 74 | 22 | 36 | 2 | 63 | 51 | 53 |

| 23 | 31 | 1 | 64 | 56 | 75 | 23 | 37 | 3 | 64 | 51 | 53 |

| 24 | 32 | 1 | 65 | 56 | 75 | 24 | 37 | 5 | 65 | 51 | 53 |

| 25 | 33 | 1 | 66 | 57 | 76 | 25 | 37 | 7 | 66 | 52 | 53 |

| 26 | 33 | 1 | 67 | 57 | 77 | 26 | 38 | 8 | 67 | 52 | 53 |

| 27 | 34 | 1 | 68 | 58 | 77 | 27 | 38 | 11 | 68 | 52 | 53 |

| 28 | 35 | 2 | 69 | 58 | 78 | 28 | 38 | 13 | 69 | 53 | 53 |

| 29 | 35 | 3 | 70 | 59 | 79 | 29 | 39 | 15 | 70 | 53 | 53 |

| 30 | 36 | 4 | 71 | 60 | 80 | 30 | 39 | 17 | 71 | 53 | 53 |

| 31 | 36 | 5 | 72 | 60 | 80 | 31 | 39 | 20 | 72 | 54 | 54 |

| 32 | 37 | 7 | 73 | 61 | 82 | 32 | 40 | 23 | 73 | 54 | 54 |

| 33 | 38 | 9 | 74 | 61 | 82 | 33 | 40 | 25 | 74 | 55 | 54 |

| 34 | 38 | 10 | 75 | 62 | 83 | 34 | 41 | 27 | 75 | 55 | 54 |

| 35 | 39 | 11 | 76 | 63 | 84 | 35 | 41 | 29 | 76 | 55 | 54 |

| 36 | 39 | 13 | 77 | 63 | 85 | 36 | 41 | 33 | 77 | 56 | 55 |

| 37 | 40 | 15 | 78 | 64 | 85 | 37 | 42 | 35 | 78 | 56 | 55 |

| 38 | 40 | 17 | 79 | 64 | 86 | 38 | 42 | 37 | 79 | 56 | 56 |

| 39 | 41 | 19 | 80 | 65 | 88 | 39 | 42 | 38 | 80 | 57 | 57 |

| 40 | 42 | 21 | 81 | 65 | 88 | 40 | 43 | 40 | 81 | 57 | 57 |

| 41 | 42 | 24 | 82 | 66 | 90 | 41 | 43 | 42 | 82 | 57 | 58 |

| 42 | 43 | 26 | 83 | 67 | 91 | 42 | 43 | 43 | 83 | 58 | 60 |

| 43 | 43 | 30 | 84 | 67 | 91 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 84 | 58 | 61 |

| 44 | 44 | 33 | 85 | 68 | 93 | 44 | 44 | 46 | 85 | 58 | 62 |

| 45 | 44 | 36 | 86 | 68 | 95 | 45 | 44 | 46 | 86 | 59 | 64 |

| 46 | 45 | 38 | 87 | 69 | 96 | 46 | 45 | 47 | 87 | 59 | 66 |

| 47 | 46 | 40 | 88 | 70 | 97 | 47 | 45 | 48 | 88 | 59 | 69 |

| 48 | 46 | 43 | 89 | 70 | 97 | 48 | 45 | 48 | 89 | 60 | 73 |

| 49 | 47 | 46 | 90 | 71 | 98 | 49 | 46 | 49 | 90 | 60 | 75 |

| 50 | 47 | 49 | 91 | 71 | 98 | 50 | 46 | 49 | 91 | 60 | 78 |

| 51 | 48 | 53 | 92 | 72 | 99 | 51 | 46 | 50 | 92 | 61 | 81 |

| 52 | 49 | 55 | 93 | 72 | 99 | 52 | 47 | 50 | 93 | 61 | 84 |

| 53 | 49 | 57 | 94 | 73 | 99 | 53 | 47 | 51 | 94 | 62 | 86 |

| 54 | 50 | 60 | 95 | 74 | 99 | 54 | 48 | 51 | 95 | 62 | 89 |

| 55 | 50 | 62 | 96 | 74 | 100 | 55 | 48 | 51 | 96 | 62 | 92 |

| 56 | 51 | 64 | 97 | 75 | 100 | 56 | 48 | 52 | 97 | 63 | 94 |

| 57 | 51 | 66 | 98 | 76 | 100 | 57 | 49 | 52 | 98 | 63 | 96 |

| 58 | 52 | 67 | 99 | 77 | 100 | 58 | 49 | 52 | 99 | 63 | 98 |

| 59 | 53 | 69 | 100 | 78 | 100 | 59 | 49 | 52 | 100 | 64 | 100 |

| 60 | 53 | 71 | 60 | 50 | 52 | ||||||

Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of the study has been to construct an improved scale for the assessment of gender role attitudes. Based on the existing scales in the literature on sexist attitudes, we have tried to include in our proposal the principal processes in our socialization - family, social interrelations and employment. To do so, items from different scales have been taken into account, in addition to other elements considered in the literature or in questionnaires previously used with victims of violence experienced within an affective relationship, and that reflected both egalitarian and sexist attitudes.

The result is the GRAS made up of 20 items with five answer options for each item. Items are classified in terms of attempting to identify attitudes held by both males and females that encourage aggressive behavior within dating relationships among adolescents, (Baber and Tucker, 2006, Glick and Fiske, 1996, Glick and Fiske, 1999, López-Cepero et al., 2013). This grouping has been distributed into two categories - transcendent attitudes vs. sexist attitudes - which in turn are subdivided into three areas: family, social interrelations and employment. The final vision of the instrument has been set up as a scale representing a bipolar dimension classified by the research team into: two items of Transcendent Attitudes in Family Function; four showing Transcendent Attitudes in Social Interrelation Function; the same number showing Sexism in Family Function and Social Function; and lastly six for Sexism in Employment Function.

At the same time as confirming the existence of a single factor which fulfills all the necessary fit indices (percentage of explained variance, GFI, RMSR, RMSEA, CFI, and SRMR), the psychometric properties of the scale offer a reliability coefficient of .99. Similarly, the factor weights results for each of the variables show high values, without this meaning that their relevance for determining the factor is lessened.

On the one hand, the results obtained, in addition to confirming their repetition, show the commonality found in the information in our scale for each of the categories set out in the different areas considered. On the other, accepting that a change in behavior first requires a change in attitude, we have attempted to discover what positions of the instrument used offer the highest likelihood of being able to be changed. In this respect, we have seen that the easiest idea to change belongs to the category Transcendent Attitude in Social Function: “People should be treated equally, regardless of their sex”; likewise, two other attitudes liable to be changed belong to this same category: “Boys have the same obligations to help with household chores as girls” and “Household chores must not be allocated by sex”. These statements show that treating both sexes equally could mean lower likelihood of aggressive behavior by either partner in adolescent dating relationships.

Bearing in mind that our study population sample is young, the results obtained invite us to be cautiously optimistic and think that upbringing styles appear to be changing in our society (Ferrer et al., 2006). This opens up the possibility of developing a more egalitarian gender role attitude, which we will need to confirm in subsequent studies where both members of the couple exclude violent conduct from their behavioral repertory.

By contrast, the category which appears to be most resistant to change is that shown by the items of Sexism in Social Function: “I think it is right that in my circles of friends, my future domestic activity is considered more important than my professional activity”, followed by those in the Employment Function grouping: “A father's main responsibility is to help his children financially”, and “Some jobs are not appropriate for women”, which may be a true reflection of the reality observed in our context - it is, furthermore, reasonable to think that it really is very difficult to change this belief and this attitude to role so deeply embedded in the gender roles to be performed by each sex. That is to say, these attitudes involve the most deeply rooted positions where gender is imposed by power - males vs. females - encouraging discrimination, particularly in employment. This is coherent with the studies of Herrera et al. (2012), Lila et al. (2014) and López-Cepero et al. (2013), who all point out a greater predisposition towards violence within affective relationships as a product of such attitudes, which should make victimization and perception of abuse possible in the world in which we live.

In sum, it is important to highlight the use of a sample made up of young people, since very little research has been carried out on this group. Using the knowledge acquired in the area, this is highly relevant for preventing the appearance and upholding of attitudes that have a negative bearing on relationships in couples and are the precursor to acceptance of violent behavior. Another strength of the research lies in the instrument designed to carry it out, which attempts to offer a wide perspective on attitudes by organizing them into two categories (egalitarian and sexist) and looking at three different contexts (family, social and employment). Also worth noting are the differences existing around two important variables (sex and educational level), our GRAS offering better information on attitudes for assessing change, one of its strengths being that it includes males and females (without segregating the information) and, on the other, that it allows the researcher to work without having to take the sexual orientation of the person being assessed into account, which has practical implications in the healthcare area. To sum up, the analysis enables the attitudes more liable to be changed to be identified, proposing the alternatives possible in order to set out the guidelines for designing prevention and intervention programs for dealing with abuse situations.

We are aware that these implications have a limitation that needs to be corrected in future studies in this area of research, insofar as establishing its construct validity and discrimination capacity will be included in more extensive assessments of abuse perceived or unperceived by victims, or its relationship with the presence or absence of violent behavior suffered or received in dating relationships between young couples.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Health, Social Policy and Equality (SUBMINMU012/009).

Footnotes

Available online 27 November 2014

Appendix 1. Gender Role Attitudes Scale (GRAS).

| 1. SFT | People can be aggressive and understanding, regardless of their sex [Las personas pueden ser tanto agresivas y comprensivas, independientemente de su sexo] |

| 2. SFT | People should be treated equally, regardless of their sex [Se debería tratar a las personas igual, independientemente del sexo al que pertenezcan] |

| 3. SFT | Children should be given freedom depending on their age and how mature they are, not depending on their sex [A los niños se les debería dar libertad en función de su edad y nivel de madurez, y no por el sexo de pertenecía] |

| 4. FFT | Boys have the same obligations to help with household chores as girls [Los chicos tienen las mismas obligaciones de ayudar en las tareas del hogar que las chicas] |

| 5. FFT | Household chores should not be allocated by sex [Las tareas domésticas no deberían asignarse por sexos] |

| 6. SFT | We should stop thinking about whether people are men or women and focus on other characteristics [Deberíamos dejar de pensar si las personas son hombre o mujer y centrarnos en otras características] |

| 7. FFS | My partner thinking that I am responsible for doing the household chores would cause me stress [El que mi pareja considere que yo soy la responsable de las tareas domésticas me crearía tensión] |

| 8. FFS | The husband is responsible for the family so the wife must obey him [El marido es el responsable de la familia por lo que la mujer le debe obedecer] |

| 9. SFS | A woman must not contradict her partner [Una mujer no debe llevar la contraria a su pareja] |

| 10. SFS | I think it is worse to see a man cry than a woman [Me parece que es más lamentable ver a un hombre llorar que a una mujer] |

| 11. SFS | Girls should be more clean and tidy than boys [Una chica debe ser más limpia y ordenada que un chico] |

| 12. EFS | Men should occupy posts of responsibility [Es preferible que los puestos de responsabilidad los ocupen los hombres] |

| 13. FFS | I think boys should be brought up differently than girls [Creo que se debe educar de modo distinto a los niños que a las niñas] |

| 14. SFS | I think it is right that in my circles of friends, my future domestic activity is considered more important than my professional activity [Considero correcto que en mis círculos de amistades se valore más mi actividad familiar futura que la profesional] |

| 15. EFS | A father's main responsibility is to help his children financially [La principal responsabilidad de un padre es ayudar económicamente a sus hijos] |

| 16. EFS | Some jobs are not appropriate for women [Algunos trabajos no son apropiados para las mujeres] |

| 17. EFS | I accept that in my circle of friends, my partner's future job is considered more important than mine [Acepto que en mi círculo de amistades el trabajo futuro de mi pareja se valore más que el mío] |

| 18. FFS | Mothers should make most of the decisions on how to bring up their children [Las madres deberían tomar la mayor parte de las decisiones sobre cómo educar a los hijos] |

| 19. EFS | Only some kinds of job are equally appropriate for men and women [Solo algunos tipos de trabajo son apropiados tanto para hombres como para mujeres] |

| 20. EFS | In many important jobs it is better to contract men than women [En muchos trabajos importantes es mejor contratar a hombres que a mujeres] |

Note. Family Function Transcendent (FFT); Social Function Transcendent (SFT); Family Function Sexism (FFS); Social Function Sexism (SFS); Employment Function Sexism (EFS).

References

- Baber K.M., Tucker C.J. The social roles questionnaire: A new approach to measure attitudes toward gender. Sex Roles. 2006;54:459–467. [Google Scholar]

- Burt M.R. Cultural myths and supports for rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;38:217–230. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.38.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Check J.V.P., Malamuth N.M., Elias B., Barton S.A. On hostile ground: Do you have feelings of hostility toward the opposite sex? Psychology Today, April. 1985:56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés L., Bringas C., Rodríguez-Franco L., Flores M., Ramiro T., Rodríguez F.J. Unperceived dating violence among Mexican students. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2014;14:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz A., Sellami K. Traits and roles in gender stereotypes: A comparison between Moroccan and Spanish native samples. Sex Roles. 2014;70:457–467. [Google Scholar]

- Echeburúa E., Fernández-Montalvo J. Hombres maltratadores. Aspectos teóricos. In: Echeburúa E., Corral P., editors. Manual de violencia familiar. Siglo XXI; Madrid: 1998. pp. 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Elosua P., Zumbo B.D. Coeficientes de fiabilidad para escalas de respuesta categórica ordenada. Psicothema. 2008;20:896–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer V.A., Bosch E., Ramis C., Torres G., Navarro C. La violencia contra las mujeres en la pareja: Creencias y actitudes en estudiantes universitarios. Psicothema. 2006;18:359–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Pérez R., Rebollo M.A., Buzón O., González-Piñal R., Barragán R., Ruiz E. Actitudes del alumnado hacia la igualdad de género. Revista de Investigación Educativa. 2010;28:217–232. [Google Scholar]

- Glick P., Fiske S.T. The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:491–512. [Google Scholar]

- Glick P., Fiske S.T. The ambivalence toward men inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent beliefs about men. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1999;23:519–536. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera M.C., Expósito F., Moya M. Negative reactions of men to the loss of power in gender relations: Lilith vs. Eve. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context. 2012;4:17–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kline R.B. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. [Google Scholar]

- Lila M., Gracia E., García F. Ambivalent sexism, empathy and law enforcement attitudes towards partner violence against women among male police officers. Psychology, Crime and Law. 2013;19:907–919. [Google Scholar]

- Lila M., Oliver A., Catalá A., Galiana L., Gracia E. The intimate partner violence responsibility attribution scale (IPVRAS) The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context. 2014;6:29–36. doi: 10.5093/ejpalc2014a4. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsway K.A., Fitzgerald L.F. Attitudinal antecedents of rape myth acceptance: A theoretical and empirical reexamination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:704–711. [Google Scholar]

- López-Cepero J., Rodríguez-Franco L., Rodríguez-Díaz F.J., Bringas C. Validación de la versión corta del Social Roles Questionnaire (SRQ-R) con una muestra adolescente y juvenil española. Revista Electrónica de Metodología Aplicada. 2013;18:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- López-Cepero, J., Rodríguez-Franco, L., Rodríguez-Díaz, F.J., Bringas, C., & Paíno, S. (in press). Indicadores conductuales y holísticos en el etiquetado de violencia en el noviazgo de adolescentes y adultos jóvenes españoles. Percepción de la victimización. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud.

- Lorenzo-Seva U., Ferrando P.J. FACTOR: A computer program to fit the exploratory factor analysis model. Behavior Research Methods. 2006;38:88–91. doi: 10.3758/bf03192753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno R., Martínez R., García-Cueto E., Fidalgo de las Heras A.M., Muñiz J. La Muralla; Madrid: 2005. Análisis de los ítems. [Google Scholar]

- Moya M., Expósito F., Padilla J.L. Revisión de las propiedades psicométricas de las versiones larga y reducida de la escala sobre ideología de género. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2006;6:709–727. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil J.M., Helms B.J., Gable R.K., David L., Wrightsman L.S. Gender-role conflict scale: College men's fear of femininity. Sex Roles. 1986;14:335–350. [Google Scholar]

- Payne D.L., Lonsway K.A., Fitzgerald L.F. Rape myth acceptance: Exploration of its structure and its measurement using the Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale. Journal of Research in Personality. 1999;33:27–68. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Castro Y., Lameiras M., Carrera M.V., Faílde J.M. Evaluación de las actitudes sexistas en estudiantes españoles/as de educación secundaria. Psicología: Avances de la Disciplina. 2010;4:11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Franco L., Antuña M.A., López-Cepero J., Rodríguez-Díaz F.J., Bringas C. Tolerance towards dating violence in Spanish adolescents. Psicothema. 2012;24:236–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Franco L., López-Cepero J., Rodríguez F.J., Bringas C., Antuña M.A., Estrada C. Validación del cuestionario de violencia entre novios (CUVINO) en jóvenes hispanohablantes: Análisis de resultados en España, México y Argentina. Anuario de Psicología Clínica y de la Salud. 2010;6 45-33. [Google Scholar]

- Samejima F. Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. Psychometrika Monograph. 1969:17. [Google Scholar]

- Swim J.K., Hyers L.L. Excuse Me-What Did you just say? !Women's Public and private responses to sexist remarks. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1999;35:66–88. [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman M.E., Lorenzo-Seva U. Dimensionality Assessment of Ordered Polytomous Items with Parallel Analysis. Psychological Methods. 2011;16:209–220. doi: 10.1037/a0023353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travaglia L.K., Overall N.C., Sibley C.G. Benevolent and hostile sexism and preferences romantic partners. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47:599–604. [Google Scholar]