Abstract

To study the epidemiological, pathological characters and determine survival in patients diagnosed of having thyroid gland malignancies. Retrospective chart review of patients having thyroid gland malignancies, which were managed by the two senior authors at our tertiary care institute from January 2000 to December 2006, were performed and evaluated in terms of various clinical, operative and histological parameters. Patients in which follow up of at least 10 years are available were included in the study. Survival was enquired telephonically in those patients who got cured and did not consent to come for follow up. Slides were reviewed. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS statistical software. Kaplan–Meier method was used for calculating survival. A total of 182 patients were included in the study. Papillary carcinoma was the commonest malignant lesion with a frequency of 87.91% followed by follicular carcinoma (7.69%), medullary carcinoma (3.29%) and anaplastic carcinoma (1.09%). Female predominance was seen (F:M–5.06:1). The 5 year and 10 year survival rates were 89% and 73% respectively. The most common postoperative squeal was transient hypocalcaemia, seen in (27/182) 15% patients which was followed by permanent hypocalcaemia 16/182 (8.79%), transient recurrent laryngeal nerve paresis 12/182 (6.59%) and permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy 8/182 (4.39%). Thyroid malignancies affect all age groups and have good long term prognosis. Management yields promising results and hence early and adequate treatment is emphasized.

Keywords: Thyroid gland malignancies, Survival in thyroid gland cancers, Metastasis in thyroid cancers, Diagnostic disparities in thyroid gland lesions, Differentiated and dedifferentiated thyroid gland cancers

Introduction

Malignancies of thyroid gland are the most common malignancies of the endocrine system. Thyroid nodules are approximately four times more common in women than in men. The median age at diagnosis is 47 years, with a peak in women at 45–49 years and in men at 65–69 years [1]. Papillary carcinoma is the most common type of thyroid malignancy, accounting for 65–80% of all thyroid cancers. New nodules develop at a rate of approximately 0.1% per year beginning in early life, but at a much higher rate (~ 2% per year) after exposure to head and neck irradiation [2, 3]. They can be follicular, papillary, medullary, anaplastic and other rare varieties like mucinous, squamous cell and mucoepidermoid carcinomas. Although papillary thyroid cancers are not associated with goiter, follicular and anaplastic thyroid cancers occur more commonly in areas of endemic goiter. Additionally, two particularly important risk factors, exposure to radiation and a family history of thyroid cancer, have been studied extensively in world literature. Prolonged survival, even with recurrent disease, has led to controversy regarding the extent of thyroidectomy for patients with well-differentiated thyroid carcinomas. Total thyroidectomy is considered as the surgical option for papillary and medullary carcinomas and hemithyroidectomy is considered as the surgical option for follicular and hurthle cell neoplasms. The 10-year relative survival rates for patients with papillary, follicular, and hurthle cell carcinomas were 93%, 85%, and 76%, respectively [4]. This study aimed to retrospectively review the cases of thyroid malignancies operated in a tertiary care center with 10 years of follow up to study the epidemiological and pathological profile and survival rates in various thyroid malignancies.

Materials and Methods

Cases of thyroid malignancies previously operated in our institute with at least 10 years of follow up were included in the study by reviewing the hospital records retrospectively. A total of 182 patients with age ranging from 28 to 75 years that had been managed as per institutional protocol were included. All the patients were evaluated with a detailed history and clinical examination at the time of presentation and then investigated with the routine hemogram, serum electrolytes, liver and renal function tests along with thyroid function tests, radiological evaluation with ultrasonography of neck and computerized tomography of neck (whenever indicated), fine needle aspiration cytological examinations and radioiodine scans preoperatively in cases of hyperthyroid patients. The work up also included routine work up for general anesthesia and detailed metastatic work up preoperatively. Total thyroidectomy was done in all cases of thyroid cancers irrespective of the size and type of tumor except in two cases of anaplastic thyroid cancers, where only palliative treatment was given. Neck dissections were done along with the primary surgery in all those patients with clinically palpable FNAC proven cervical lymphadenopathy and in patients with clinically suspicious involved lymph nodes intra-operatively. Surgical specimens were analyzed histopathologically. Post operatively patients were kept on follow up till now and were routinely investigated with serial ultrasonography of neck, thyroglobulin levels and radioiodine scans. Majority of the surviving patients are still under institutional follow up.

Results

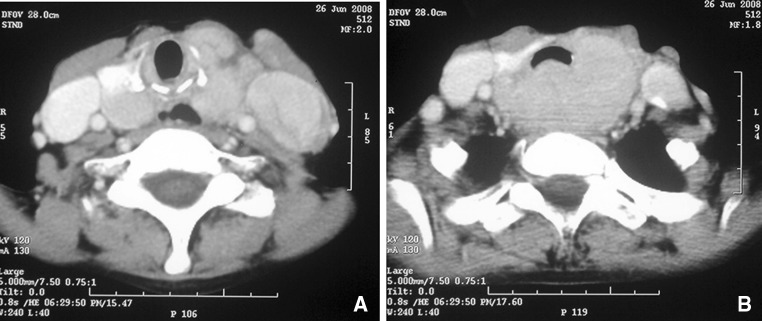

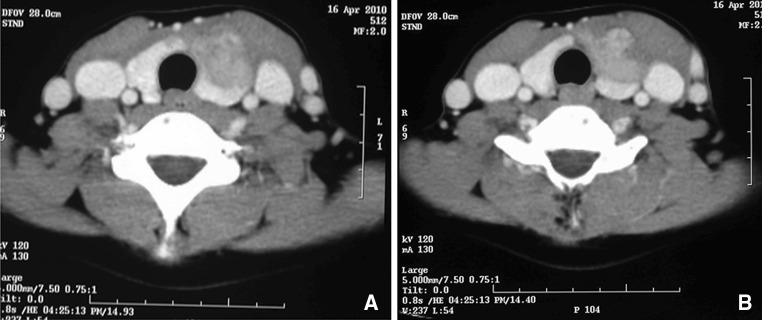

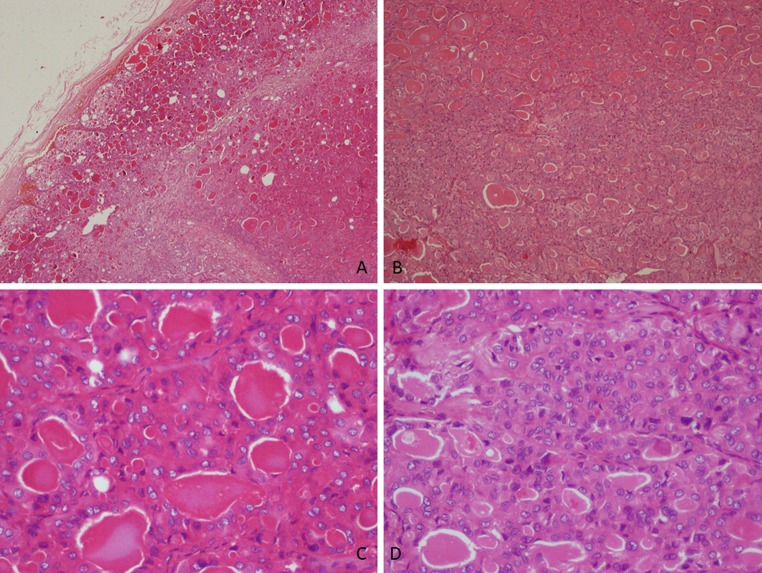

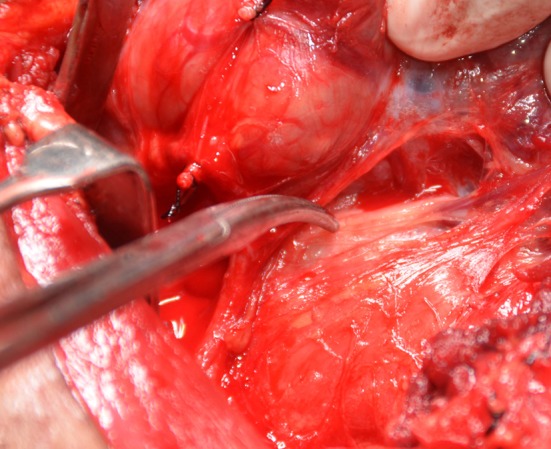

A total of 182 patients were included in the study by retrospective hospital record review. The age of the patients ranged from 18 to 75 years with 30 males (16%) and 152 (84%) females. Thyroid function tests were done and showed euthyroid state in 174 patients. Six patients were found to be hyperthyroid and two patients were hypothyroid. Total thyroidectomy was done in 180 patients. Rest two patients of anaplastic carcinoma were treated with palliative treatment. Post-operative histopathology showed papillary carcinoma to be the most common malignant lesion with a frequency of 87.91% (160/182) followed by follicular carcinoma in 7.69% (14/182) of patients, medullary carcinoma 3.29% (6/182) of patients and anaplastic carcinoma in 1.09% (2/182) of patients (Table 1). Laryngo-tracheal framework invasion was found in 33 patients. Lymph node metastases were found in 56 patients and among them 23 patients had bilateral lymph node metastases. Figure 1 demonstrates a case of bulky lymph node disease with extensive involvement of tracheoesophageal groove. Figure 2 demonstrates a case of medullary carcinoma thyroid with gross extra thyroidal extension with involvement of strap muscles of neck and loss of fat planes with internal jugular vein. Lymph node metastasis without obvious thyromegaly was found in 16 patients and systemic metastasis was found in 23 patients. Among them bone was the most common site involved in (10/23) 43.47% of cases followed by lungs in (9/23) 39.13% of cases and liver in (3/23) 13.04% of cases (Table 1). Metastasis to kidney was seen in one case. Retrosternal extension was found in 18 patients and discrepancy between pre-operative FNAC and postoperative histopathology was found in 21 patients. These 21 cases included only those cases where the FNA diagnosis was either benign or had a different variant of malignancy compared to that of the histological diagnoses. Other than these there were 11 cases where the FNA was papillary carcinoma thyroid but post op histology was benign and we had excluded them from our study as we were studying only those cases where final diagnosis was malignancy of thyroid gland. At least one parathyroid was preserved in 52 patients and parathyroid re-implantation was done in 15 patients. Coexistent Lymphocytic thyroiditis was seen on histopathological examination in 38 patients. Figure 3 demonstrates the histopathological features of a case of follicular variant of papillary carcinoma thyroid. Clinical evaluation, thyroglobulin monitoring, serial USG and radioiodine scanning were done for postoperative monitoring. 92 Patients underwent radioiodine ablation and 26 patients underwent radioiodine ablation for the second time. The postoperative squeal involved temporary hypocalcaemia in (27/182) 15% of patients and permanent hypocalcaemia in 16 (8.79%) of patients. Attempt was made in every case to identify and preserve the recurrent laryngeal nerve (Fig. 4). Temporary recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy was observed in 12 (6.59%) patients and permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy was observed in 8 (4.39%) patients. Postoperative hematoma was observed in four patients. Average 5 years and 10 years disease free survival rates observed in differentiated thyroid carcinomas were 89% and 73% respectively.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Total no of patients | 182 |

| Females | 152 |

| Males | 30 |

| Histological variants | |

| Papillary carcinoma | 160 |

| Follicular carcinoma | 14 |

| Medullary carcinoma | 6 |

| Anaplastic carcinoma | 2 |

| Extra thyroidal extension | 61 |

| Invasion of laryngo-tracheal framework | 30 |

| Strap muscle invasion | 28 |

| Both strap muscle and laryngo-tracheal framework invasion | 3 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 56 |

| Bilateral LN metastasis | 23 |

| LN metastasis without thyromegaly | 16 |

| Systemic metastasis | 23 |

| Bone | 10 |

| Lung | 9 |

| Liver | 3 |

| Kidney | 1 |

Fig. 1.

A case of papillary carcinoma thyroid with bulky lymph nodal involvement (a) and with extensive infiltration into the trachea-esophageal groove (b)

Fig. 2.

A case of medullary carcinoma thyroid with gross extra-thyroidal extension and involvement of the surrounding soft tissues and strap muscles of neck (a) and with loss of fat planes with IJV (b)

Fig. 3.

Histological pictures of a case of follicular variant of papillary carcinoma thyroid (a–d)

Fig. 4.

Demonstrating recurrent laryngeal nerve in a case of Ca thyroid while dissection

Discussion

Epidemiologic studies have shown the prevalence of palpable thyroid nodules to be approximately 5% in women and 1% in men living in iodine-sufficient parts of the world [5, 6]. Palpable nodules increase in frequency throughout life, reaching a prevalence of approximately 5% in the population aged 50 years and older [7, 8]. Thyroid malignancies occur in 5–15% of thyroid neoplasms [7, 9]. As with thyroid nodules, thyroid carcinoma occurs 2–3 times more often in women than in men. With the incidence increasing by 6.2% per year, thyroid carcinoma is currently the sixth most common malignancy diagnosed in women [10, 11]. Although thyroid carcinoma can occur at any age, the peak incidence lies near age 45–49 years in women and 65–69 years in men [11, 12]. Thyroid carcinoma has 3 main histologic types: differentiated (including papillary, follicular, and Hurthle cell), medullary, and anaplastic (aggressive undifferentiated tumor). Differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC), which includes papillary and follicular cancer, comprises the vast majority (90%) of all thyroid cancers [13]. Of 53,856 patients treated for thyroid carcinoma between 1985 and 1995, 80% had papillary carcinoma, 11% had follicular carcinoma, 3% had Hurthle cell carcinoma, 4% had medullary carcinoma, and 2% had anaplastic thyroid carcinoma [4]. Although thyroid carcinoma occurs more often in women, mortality rates are higher for men, probably because men are usually older at diagnosis [14, 15]. Exposure to ionizing radiation is the only known environmental cause of thyroid carcinoma, usually causing papillary carcinoma. The thyroid gland is the only organ linked to risks of developing cancers related in a linear way (down to 0.10 Gys) to ionizing radiation exposures in childhood by convincing evidence particularly those younger than 15 years with an excess relative risk of 7.7 per Gy of radiation (ERR/Gy) and 88% of attributable risk percent at 1 Gy2. RET rearrangements were found in PTCs induced by radiation [16]. Family history and long standing goiter are other studied risk factors. The loss of chromosomes or aneuploidy has been noted in 10% of all papillary carcinomas but is present in 25–50% of all patients who die as a result of these lesions [17]. BRAF V600E mutation positivity almost always is associated with papillary carcinomas [18, 19]. Similarly, the development of follicular adenomas is associated with a loss of the short arm of chromosome 11 (11p), and transition to a follicular carcinoma seems to involve deletions of 3p, 7q, and 22q [20]. Follicular thyroid cancers harbor RAS mutations or PAX8/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) rearrangements [21]. Loss of heterozygosity involving multiple chromosomal regions is much more prevalent in follicular adenomas and carcinomas than in papillary carcinomas [22]. Mutations within the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway are involved in malignant transformation to papillary thyroid cancer and activation of RET or BRAF proto-oncogenes can also activate MAPK leading to papillary thyroid cancer [23]. Other genetic changes have also been associated with certain types of thyroid carcinoma. Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutations have been recently described (associated with distant metastases and reduced survival) in papillary and follicular carcinomas, as well as in poorly differentiated and undifferentiated carcinoma and TP53 mutations which were previously thought to be restricted to less differentiated carcinomas have also been detected in papillary and follicular carcinoma and its presence found to carry a guarded prognosis [23].

Differentiated (i.e., papillary, follicular, or Hurthle cell) thyroid carcinoma is usually asymptomatic for long periods and commonly presents as a solitary thyroid nodule. Approximately 50% of the malignant nodules are discovered during a routine physical examination, by serendipity on imaging studies, or during surgery for benign disease. The other 50% are usually noticed first by the patient, usually as asymptomatic nodules [8, 14, 24]. Ultrasonography of neck is considered the first gold standard radiological tool for evaluation of suspicious thyroid nodules. Suspicious criteria found using ultrasound include central hyper vascularity, microcalcifications, and irregular borders [25, 26]. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is the preferred first procedure for evaluating suspicious thyroid nodules [10, 17, 25]. Cytological examination of an FNA specimen is typically categorized as (a) nondiagnostic/unsatisfactory; (b) benign; (c) atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance (AUS/FLUS); (d) follicular neoplasm/suspicious for follicular neoplasm (FN/SFN), a category that also encompasses the diagnosis of Hurthle cell neoplasm/suspicious for Hurthle cell neoplasm; (e) suspicious for malignancy (SUSP), and (f) malignant [27, 28]. FNAC examination is also found to have limitations like false positive and false negative papillary carcinomas [29–31], difficulty in differentiating Hurthle cell from medullary and follicular carcinomas and difficulty in differentiating anaplastic carcinomas from medullary carcinoma, thyroid lymphoma and poorly differentiated metastatic thyroid lesions [32]. FNA is far less able to discriminate follicular and Hurthle cell carcinomas from benign adenomas, be-cause diagnosis of these malignancies requires demonstration of vascular or capsular invasion [33].

Depending on initial therapy and other prognostic variables, approximately 30% of patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma have tumor recurrences during several decades; 66% of these recurrences occur within the first decade after initial therapy. In one large study, central neck recurrences were seen most often in the cervical lymph nodes (74%), followed by the thyroid remnant (20%), and then the trachea or muscle (6%). Of the group with local recurrences, 8% eventually died of cancer. Distant metastases were the sites of recurrence in 21% of this patient cohort, most often (63%) in the lungs alone. Of the patients with distant metastases, 50% died of cancer [4].

Prognosis is less favorable in men, but the difference is usually small. It’s been found that gender was an independent prognostic variable for survival and that the risk for death from cancer was approximately twice as high in men as in women [4, 15]. Although the prognosis in children with thyroid carcinoma is favorable for long-term survival (90% at 20 years), the standardized mortality ratio is much higher than predicted [34].

Up to 10% of differentiated thyroid carcinomas invade through the outer border of the gland/lymph nodes and grow directly into surrounding tissues, increasing both morbidity and mortality. Recurrence rates are two times higher with locally invasive tumors, and as many as one-third of patients with these tumors die of cancer within a decade [4, 35, 36]. In one review, nodal metastases were found in 36% of 8029 adults with papillary carcinoma, 17% of 1540 patients with follicular carcinoma, and up to 80% of children with papillary carcinoma [37]. An enlarged cervical lymph node may be the only sign of thyroid carcinoma. In these patients, multiple nodal metastases are usually found at surgery [38]. Almost 10% of patients with papillary carcinoma and up to 25% of those with follicular carcinoma develop distant metastases. Approximately 50% of these metastases are present at diagnosis [37]. The sites of reported distant metastases among 1231 patients in 13 studies were lung (49%), bone (25%), both lung and bone (15%), and the central nervous sys-tem (CNS) or other soft tissues (10%) [39]. The main predictors of outcome for patients with distant metastases are patient age and the tumor’s metastatic site, ability to concentrate 131I, and morphology on chest radiograph, persisting elevated human thyroglobulin levels after one (131)I therapy, age greater than 45 and gender in follicular cancer [35, 40].

In terms of treatment total thyroidectomy is considered the preferred surgical option for papillary carcinomas. A study in more than 5000 patients found that survival of patients after partial thyroidectomy was similar to survival after total thyroidectomy for both low- and high-risk patients [41, 42]. However, another study in 2784 patients with differentiated thyroid cancer (86% with papillary thyroid cancer) found that total thyroidectomy was associated with increased survival in high-risk patients [43]. Another study including 52,173 patients found that, compared with lobectomy, total thyroidectomy improves survival in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma greater than 1 cm [44]. Adjuvant radioiodine ablation (30–100 mCi) to destroy residual thyroid function is recommended for suspected (based on pathology, postoperative Tg, and intraoperative findings) or proven thyroid bed uptake in patients who have undergone total thyroidectomy and have no gross residual disease in the neck. Radioiodine treatment is not needed for patients with Tg levels less than 1 ng/mL, negative radioiodine imaging, and negative anti-Tg antibodies [45]. Intravenous bisphosphonate (pamidronate or zoledronic acid) therapy may be considered for symptomatic bone metastases, and embolization of metastases can also be considered [46, 47].

The FNA cyto-logic diagnosis of follicular neoplasm is a benign follicular adenoma in 80% of cases. However, 20% of patients with follicular neoplasms are ultimately diagnosed with follicular thyroid carcinoma when the final pathology is assessed. Because most patients with follicular neoplasms have benign disease, total thyroidectomy is recommended only if invasive cancer or metastatic disease is apparent at surgery or if the patient chooses total thyroidectomy to avoid a second procedure if cancer is found at pathologic review. Completion thyroidectomy is also recommended for tumors that, on final histologic sections after lobectomy plus isthmusectomy, are minimally invasive follicular carcinomas; minimally invasive cancer is characterized as a well-defined tumor with microscopic capsular and/or a few foci of vascular invasion, and often requires examination of at least 10 histologic sections [48].

A Hürthle cell tumor (also known as oxyphilic cell carcinoma) is usually assumed to be a variant of follicular thyroid carcinoma, although the prognosis of Hurthle cell carcinoma is worse [49]. The Hurthle cell variant of papillary carcinoma is rare and seems to have a prognosis similar to follicular thyroid carcinoma [50]. The management of hurthle cell carcinoma is similar to follicular carcinoma except that it can present with associated lymphadenopathy and need neck dissection along with primary surgery and metastatic hurthle cell lesions are less like to concentrate 131I. In hurthle cell cancers, radioiodine therapy (100–150 mCi) should be considered after thyroidectomy for patients with stimulated Tg levels of more than 10 ng/mL even with negative scans [49].

Total thyroidectomy is the treatment of choice in patients with medullary carcinoma because the lesions have a high incidence of multi-centricity and an aggressive disease course. Patients with familial medullary carcinoma thyroid or MEN II should have the entire gland removed, even in the absence of a palpable mass. When the primary lesion is greater than 1 cm (> 0.5 cm for MEN IIB patients), or when central compartment lymph node metastases are present, elective ipsilateral comprehensive neck dissection should be considered because nodal metastases may be present in more than 60% of these patients [51].

Anaplastic thyroid carcinomas are aggressive undifferentiated tumors, with a disease-specific mortality approaching 100% [52]. Patients with anaplastic carcinoma are older than those with differentiated carcinomas, with a mean age at diagnosis of approximately 71 years [53]. No effective therapy exists for anaplastic carcinoma. The median survival from diagnosis ranges from 3 to 7 months [54–57].

Conclusion

Thyroid malignancies affect all age groups with gender and age acting as independent prognostic factors. Trends are changing towards young males being diagnosed with malignancies. Laryngotracheal involvement is not uncommon. Regional and distant metastasis predicts recurrence and survival rates. Early diagnosis and aggressive therapeutic approach can improve survival outcomes with low recurrence rates, in patients of thyroid gland malignancies. Better treatment strategies are still needed to manage anaplastic carcinoma patients. Rigorous follow-up protocols are a must for better outcomes in patients of thyroid malignancies.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hayat MJ, Howlader N, Reichman ME, Edwards BK. Cancer statistics, trends, and multiple primary cancer analyses from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) program. Oncologist. 2007;12(1):20–37. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-1-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ron E, Lubin JH, Shore RE, et al. Thyroid cancer after exposure to external radiation: a pooled analysis of seven studies. Radiat Res. 1995;141(3):259–277. doi: 10.2307/3579003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider AB, Bekerman C, Leland J, et al. Thyroid nodules in the follow-up of irradiated individuals: comparison of thyroid ultrasound with scanning and palpation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(12):4020–4027. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hundahl SA, Fleming ID, Fremgen AM, Menck HR. A National Cancer Data Base report on 53,856 cases of thyroid carcinoma treated in the U.S., 1985–1995 [see comments] Cancer. 1998;83(12):2638–2648. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19981215)83:12<2638::AID-CNCR31>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tunbridge WM, Evered DC, Hall R, et al. The spectrum of thyroid disease in a community: the Whickham survey. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1977;7(6):481–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1977.tb01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vander JB, Gaston EA, Dawber TR. The significance of nontoxic thyroid nodules. Final report of a 15-year study of the incidence of thyroid malignancy. Ann Intern Med. 1968;69(3):537–540. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-69-3-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hegedus L. Clinical practice. The thyroid nodule. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(17):1764–1771. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp031436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, et al. Management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2006;16(2):109–142. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandel SJ. A 64-year-old woman with a thyroid nodule. JAMA. 2004;292(21):2632–2642. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.21.2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(4):225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferlay J. Cancer IAfRo. GLOBOCAN, Cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altekruse S, Das A, Cho H, Petkov V, Yu M. Do US thyroid cancer incidence rates increase with socioeconomic status among people with health insurance? An observational study using SEER population-based data. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009843. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherman SI. Thyroid carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;361(9356):501–511. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazzaferri EL, Jhiang SM. Long-term impact of initial surgical and medical therapy on papillary and follicular thyroid cancer. Am J Med. 1994;97(5):418–428. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonklaas J, Nogueras-Gonzalez G, Munsell M, et al. The impact of age and gender on papillary thyroid cancer survival. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):E878–E887. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ushenkova LN, Koterov AN, Biryukov AP. Pooled analysis of RET/PTC gene rearrangement rate in sporadic and radiogenic thyroid papillary carcinoma. Radiat Biol Radioecol. 2015;55(4):355–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sozzi G, Bongarzone I, Miozzo M, et al. Cytogenetic and molecular genetic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1992;5(3):212–218. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870050307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarashchenko YN, Kovalenko AE, Bolgov MY, et al. Braf-status of papillary thyroid carcinomas and strategy of surgical treatment. Klin Khir. 2015;6:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang L, Chu H, Zheng H. B-Raf mutation and papillary thyroid carcinoma patients. Oncol Lett. 2016;11(4):2699–2705. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitamura Y, Shimizu K, Tanaka S, Emi M. Genetic alterations in thyroid carcinomas. Nihon Ika Daigaku Zasshi. 1999;66(5):319–323. doi: 10.1272/jnms.66.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song YS, Lim JA, Park YJ. Mutation profile of well-differentiated thyroid cancer in Asians. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2015;30(3):252–262. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2015.30.3.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sobrinho-Simoes M, Preto A, Rocha AS, et al. Molecular pathology of well-differentiated thyroid carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2005;447(5):787–793. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-0065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grubbs EG, Rich TA, Li G, et al. Recent advances in thyroid cancer. Curr Probl Surg. 2008;45(3):156–250. doi: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Majumder KR, Karmakar R, Karim SS, Al-Mamun A. Malignancy in solitary thyroid nodule. Mymensingh Med J. 2016;25(1):39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frates MC, Benson CB, Charboneau JW, et al. Management of thyroid nodules detected at US: Society of radiologists in ultrasound consensus conference statement. Radiology. 2005;237(3):794–800. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2373050220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brander AE, Viikinkoski VP, Nickels JI, Kivisaari LM. Importance of thyroid abnormalities detected at US screening: a 5-year follow-up. Radiology. 2000;215(3):801–806. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.3.r00jn07801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baloch ZW, Cibas ES, Clark DP, et al. The National Cancer Institute Thyroid fine needle aspiration state of the science conference: a summation. Cytojournal. 2008;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1742-6413-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cibas ES, Ali SZ. The bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132(5):658–665. doi: 10.1309/AJCPPHLWMI3JV4LA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bestepe N, Ozdemir D, Tam AA, et al. Malignancy risk and false-negative rate of fine needle aspiration cytology in thyroid nodules ≥ 4.0 cm. Surgery. 2016;160:405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao H, Kao RH, Hsieh MC. Comparison of core-needle biopsy and fine-needle aspiration in screening for thyroid malignancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:1291–1301. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2016.1170674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeh MW, Demircan O, Ituarte P, Clark OH. False-negative fine-needle aspiration cytology results delay treatment and adversely affect outcome in patients with thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2004;14(3):207–215. doi: 10.1089/105072504773297885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barabadze E, Burkadze G, Munjishvili V. Accurate diagnosis of thyroid nodules: a review of diagnostic dilemmas on thyroid fine-needle aspiration biopsies. Georgian Med News. 2016;252:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Layfield LJ, Cibas ES, Gharib H, Mandel SJ. Thyroid aspiration cytology: current status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(2):99–110. doi: 10.3322/caac.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Qurayshi Z, Hauch A, Srivastav S, Aslam R, Friedlander P, Kandil E. A national perspective of the risk, presentation, and outcomes of pediatric thyroid cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142:472–478. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eichhorn W, Tabler H, Lippold R, Lochmann M, Schreckenberger M, Bartenstein P. Prognostic factors determining long-term survival in well-differentiated thyroid cancer: an analysis of four hundred eighty-four patients undergoing therapy and aftercare at the same institution. Thyroid. 2003;13(10):949–958. doi: 10.1089/105072503322511355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Veronese N, Luchini C, Nottegar A, et al. Prognostic impact of extra-nodal extension in thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112(8):828–833. doi: 10.1002/jso.24070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazzaferri EL. Management of a solitary thyroid nodule. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(8):553–559. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302253280807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pingpank JF, Jr, Sasson AR, Hanlon AL, Friedman CD, Ridge JA. Tumor above the spinal accessory nerve in papillary thyroid cancer that involves lateral neck nodes: a common occurrence. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128(11):1275–1278. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.11.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruegemer JJ, Hay ID, Bergstralh EJ, Ryan JJ, Offord KP, Gorman CA. Distant metastases in differentiated thyroid carcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic variables. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;67(3):501–508. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-3-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sisson JC, Giordano TJ, Jamadar DA, et al. 131-I treatment of micronodular pulmonary metastases from papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;78(10):2184–2192. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19961115)78:10<2184::AID-CNCR21>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haigh PI, Urbach DR, Rotstein LE. Extent of thyroidectomy is not a major determinant of survival in low- or high-risk papillary thyroid cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12(1):81–89. doi: 10.1007/s10434-004-1165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haigh PI, Urbach DR, Rotstein LE. AMES prognostic index and extent of thyroidectomy for well-differentiated thyroid cancer in the United States. Surgery. 2004;136(3):609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jonklaas J, Sarlis NJ, Litofsky D, et al. Outcomes of patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma following initial therapy. Thyroid. 2006;16(12):1229–1242. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY, et al. Extent of surgery affects survival for papillary thyroid cancer. Ann Surg. 2007;246(3):375–381. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31814697d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDougall IR, Hay ID. ATA guidelines: do patients with stage I thyroid cancer benefit from (131)I? Thyroid. 2007;17(6):595–596. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eustatia-Rutten CF, Romijn JA, Guijt MJ, et al. Outcome of palliative embolization of bone metastases in differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(7):3184–3189. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muresan MM, Olivier P, Leclere J, et al. Bone metastases from differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15(1):37–49. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson LD, Wieneke JA, Paal E, Frommelt RA, Adair CF, Heffess CS. A clinicopathologic study of minimally invasive follicular carcinoma of the thyroid gland with a review of the English literature. Cancer. 2001;91(3):505–524. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010201)91:3<505::AID-CNCR1029>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lopez-Penabad L, Chiu AC, Hoff AO, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with Hurthle cell neoplasms of the thyroid. Cancer. 2003;97(5):1186–1194. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herrera MF, Hay ID, Wu PS, et al. Hurthle cell (oxyphilic) papillary thyroid carcinoma: a variant with more aggressive biologic behavior. World J Surg. 1992;16(4):669–674. doi: 10.1007/BF02067351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Block MA. Surgical treatment of medullary carcinoma of the thyroid. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 1990;23(3):453–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Are C, Shaha AR. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: biology, pathogenesis, prognostic factors, and treatment approaches. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(4):453–464. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kebebew E, Greenspan FS, Clark OH, Woeber KA, McMillan A. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Treatment outcome and prognostic factors. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1330–1335. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Untch BR, Olson JA., Jr Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, thyroid lymphoma, and metastasis to thyroid. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2006;15(3):661–679. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Venkatesh YS, Ordonez NG, Schultz PN, Hickey RC, Goepfert H, Samaan NA. Anaplastic carcinoma of the thyroid. A clinicopathologic study of 121 cases. Cancer. 1990;66(2):321–330. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900715)66:2<321::AID-CNCR2820660221>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kwon J, Kim BH, Jung HW, Besic N, Sugitani I, Wu HG. The prognostic impacts of postoperative radiotherapy in the patients with resected anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2016;59:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lennon P, Deady S, Healy ML, et al. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: Failure of conventional therapy but hope of targeted therapy. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E1122–E1129. doi: 10.1002/hed.24170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]