Abstract

To examine whether adding preconditioning hamstring resistance exercises to a regular warm-up prior to a repeated sprinting exercise provides protection against the sprinting-induced muscle damage. Ten female soccer players (mean ± SD age: 21.3 ± 4.5yrs; height: 171.34 ± 8.29 cm; weight: 68.53 ± 11.27 kg) participated in this study. After the familiarization visit, the subjects completed three separate randomly sequenced experimental visits, during which three different warm-up interventions were performed before the muscle-damaging protocol (12 sets of 30-m maximal repeated sprints): 1. Regular running and static stretching (Control); 2. Control with hyperextensions (HE); 3. Control with single leg Romanian deadlift (SLRD). Before (Pre), immediately (Post0), 24 hours (24hr), and 48 hours after (48hr) the sprints, hamstring muscle thickness, muscle stiffness, knee flexion eccentric peak torque, knee extension concentric peak torque, and functional hamstring to quadriceps ratios were measured. Repeated sprints have induced muscle damage (e.g., an average of 42% knee flexion eccentric strength reduction) in all three conditions. After the SLRD, hamstring muscle thickness decreased from 24hr to 48hr (p < 0.001). Additionally, muscle stiffness and eccentric strength for the SLRD showed no difference from baseline at 24hr and 48hr, respectively. When compared with the SLRD at 48hr, the muscle stiffness and the eccentric strength were greater and lower, respectively, in other protocols. The SLRD protocol had protective effect on sprinting-induced muscle damage markers than other protocols. Athletes whose competitions/training are densely scheduled may take advantage of this strategy to facilitate muscle recovery.

Keywords: Muscle damage, Eccentric contraction, Warm-up, Preconditioning, Resistance exercise

INTRODUCTION

Hamstrings strain injuries (HSIs) often occur in sporting activities which contain high-speed open kinetic chain type muscle contractions such as sprinting [1]. During the terminal swing phase of a sprint, the hip is flexing and the knee is extending rapidly, creating a situation where a large amount of force is required from the lengthening knee flexors. This eccentric portion of the sprinting activity plays an important role decreasing the hamstring muscle strength, muscle activation, and flexibility for a prolonged period of time, known as the eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage [2, 3]. Many team sports (e.g. soccer, rugby, hockey) require athletes to perform numerous intermittent and repeated sprints, which may increase the likelihood of muscle damage, thereafter leading to a decline in performance. In fact, Keane et al. [4] reported reduced countermovement jump height and sprint performance with increased muscle soreness and creatine kinase level following the repeated sprints, even in well-trained athletes [5]. Therefore, athletes who perform maximal sprinting activities on a regular basis may suffer from impaired performance. In addition, if their competitions are densely scheduled (e.g., 2-3 times per week), full muscle/performance recovery between competitions cannot be guaranteed, which not only negatively affects their sports performance, but serves as a common HSI risk factor during the competition season [2, 6, 7].

Besides eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage, other common HSI risk factors include inadequate warm-up, muscle soreness, muscle stiffness, muscle imbalance (hamstrings/quadriceps strength ratio), etc. [8]. Thus, different interventions such as stretching and resistance training have been used to improve hamstring muscle functions, in order to prevent HSIs [9, 10]. It has been reported that adequate warm-up with proper stretching exercises may improve sports performance [11], however, their influence on subsequent exercise-induced muscle damage remain controversial [12, 13]. For example, Johansson and colleagues [3] found that 4 sets of 20-s static stretching for the hamstring muscle group has no preventive effect on muscular soreness, tenderness and force loss following the muscle-damaging knee flexion eccentric exercise. On the other hand, a brief warm-up combined with static active or dynamic active stretches attenuated the symptoms of muscle damage after eccentric exercise [14].

In addition to a variety of warm-up and stretching programs, hamstring strength training has also been considered as a primary tool to improve hamstring strength, thereby reducing HSIs. For example, injury prevention programs that include the Nordic hamstring lower exercise reduced HSIs up to 51% when compared with the ones did not incorporate injury prevention programs [15]. A 10-week hip extension training also significantly increased biceps femoris long head fascicle length and muscle volume, making the hamstrings less likely to strain [16]. Considering the positive effects of chronic hamstring strength training, it would be interesting to incorporate such resistance exercises as a preconditioning bout prior to high intensity repeated sprints, and to examine whether such interventions could attenuate potential muscle damage and HSI risk factors. It has been reported that preconditioning low-intensity eccentric exercises on knee flexors and extensors could provide protection against subsequent eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage [17]. This term is referred to as the repeated bout effect, however, the effective time window between the first bout and second bout, as well as how long this effect can last, differ across a variety of populations. In addition, it is also unclear whether resistance exercises with different intensities and eccentric contractions portions would impose differential effects on sprinting-induced muscle damage [18, 19].

Therefore, the purpose of this investigation was to examine whether adding preconditioning non-fatiguing hamstring resistance exercises to the regular warm-up prior to a bout of repeated maximal sprints provide protective effects against sprint-induced muscle damage in female soccer players. Instead of the Nordic hamstring lower exercise, the hyperextension off the table (HE) and the single leg Romanian deadlift (SLRD) exercises were separately incorporated into the regular warm-up protocol, as the intensity of Nordic hamstring lower exercise is considered to be high, which may affect subsequent sports performance, and has rarely been used as a warm-up protocol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Ten female soccer players (mean ± SD age: 21.3 ± 4.5yrs; height: 171.34 ± 8.29 cm; weight: 68.53 ± 11.27 kg) voluntarily participated in this investigation. Subjects were eligible to participate if they practiced soccer at a university or recreational league level. In addition, they had to participate in at least two training sessions per week, who all had at least a year of training experience. Subjects were excluded from the study if they had any injuries on the ankles, knees, hips, low back, or hamstring muscles over the past one year. All subjects provided written informed consent before testing. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Research of the National Taiwan University. Subjects were instructed to avoid their regular training throughout the experimental period and refrained from vigorous physical activities 72 hours before each testing visit. All experimental procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Design

This investigation used a crossover design to examine the effects of different warm-up interventions on muscle damage markers following a maximal repeated sprinting protocol. All subjects visited the laboratory on 4 separate occasions. The first visit was to familiarize the subjects with all the measurement tests, as well as the different warm-up protocols. The following three experimental visits were conducted in a randomized order, during which different warm-up interventions were performed before the repeated maximal sprints: 1. Only regular running and static stretching (Control); 2. Regular running and static stretching followed by hyperextensions off table exercise (HE); 3. Regular running and static stretching followed by single leg Romanian deadlift exercise (SLRD). At least 7 days of rest were provided between consecutive experimental visits. All dependent variables were measured at the baseline (Pre), immediately (Post0), 24 hours (24hr), and 48 hours (48hr) after the maximal repeated sprints. The measurements were always performed at the dominant side of the subjects, determined by which foot the subjects would kick a soccer ball.

Procedures

At each experimental testing visit, the subjects started with a regular warm-up protocol which began with 5 minutes of running at 60-100% of their perceived maximum speed with a series of dynamic sprint drills (high knees, heel-flicks, and walking lunges). Following the running exercise, subjects were given 5 minutes to perform unassisted static stretching exercises on their gluteus, psoas, adductors, hamstrings and quadriceps muscles. Each unassisted stretching exercise was performed one time for 30 seconds to the level of mild discomfort, but not pain on each leg. A detailed description of the stretching exercises is listed in Ayala et al [20]. Following the stretching protocol, subjects were instructed to perform one of the three warm-up intervention protocols: 1) Control: during which the subjects rested for 5 minutes with the sitting position; 2) HE: the subject lay down on a hyperextension bench with the prone position. With the legs fixated by a research staff, the subject’s hip and upper body were hanging off the bench’s edge. The subject then started to bend down slowly with the back flat until a stretch is felt on the hamstrings. With one second pause at the bottom, the upper body was raised again until the hip is fully extended. The subjects performed this exercise for 12 repetitions with full range of motion and controlled manner; 3) SLRD: the subject started with the standing position on one foot and with the knee slightly flexed (10-15°), then she slowly bent the upper body forward until reaching the end range of motion of the hip flexion. The subject then simultaneously extended the knee to stretch the hamstring muscles to the point of discomfort but without pain. With one second pause at the bottom, the upper body was raised back to the standing position. This exercise was performed on each leg with 12 repetitions with controlled manner.

Following the warm-up intervention protocol, the baseline (Pre) measurements were conducted in the following order: muscle thickness, muscle stiffness, and isokinetic knee flexion/extension peak torque. The maximal repeated sprints protocol began after the baseline measurements. The subjects performed 12 sets of 30-m maximal repeated sprints, with a 10-m acceleration and a 15-m deceleration for each sprint. The rest interval between consecutive sprints were 60 seconds. Immediately (Post0), 24 hours (24hr), and 48 hours (48hr) after the sprinting exercise, dependent variables were measured again with the same order and manner as they were measured at the baseline.

Measurements

Muscle Thickness

Muscle thickness was determined from the ultrasound images taken along the longitudinal axis of the muscle belly using a two-dimensional, B-mode ultrasound equipment (Siemens ACUSON S2000™, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with a 7.5 MHz linear probe. The images were then analyzed digitally off-line. With the subjects lying in the prone position with lower limbs relaxed, the probe was placed on the subject’s dominant leg at the halfway point between the ischial tuberosity and the knee joint fold, along the line of the long head of the biceps femoris (BFlh). The muscle thickness was quantified as the mean of the vertical distances delimited by superficial and deep aponeuroses measured at both image extremities.

Muscle Stiffness

Muscle stiffness was measured in real time based on the acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) technique. Using the ARFI-based elastography examination mode to measure the shear wave velocity (SWV, m/s) provides an indicator of muscle stiffness of the BFlh. The ARFI measurement was performed with the same ultrasound system as the muscle thickness was measured. The probe was held over the BFlh, parallel to the long axis of the muscle, to obtain a valid SWV measurement.

Isokinetic Strength and Functional Hamstring to Quadriceps Ratios (f-H:Q)

An isokinetic dynamometer (Biodex System Pro 4, Biodex Medical Systems, Inc., Shirley, NY) was used to assess hamstring and quadriceps muscle strength performance. The subject sat with a comfortable position on the dynamometer. The mechanical axis of the dynamometer was aligned with the lateral epicondyle of the knee. The trunk, the waist, the thigh, and the chest were strapped with belts to minimize extraneous body movements. The range of motion of the dominant knee was set before the strength testing. The subjects performed a standardized warm-up composed of 3 submaximal (50% of perceived maximal effort) eccentric contractions at the designated angular speed before each test. After a 2-minute rest, they were asked to perform 3 maximal eccentric knee flexion contractions at the angular speed of 30°/s, and the eccentric peak torques were then recorded. A 45-second rest period was provided between consecutive maximal voluntary contractions (MVCs). Two minutes after the knee flexion eccentric strength testing, the subjects performed concentric knee extension warm-up followed by 3 maximal concentric knee extension contractions at 60°/s, and the concentric peak torques of the knee extensors were recorded. The highest peak torque of the three maximal contractions for each test was collected for data analysis. The functional hamstring to quadriceps ratios (f-H:Q) was calculated as the maximal eccentric knee flexion peak torque divided by the maximal concentric knee extension peak torque. As the ratio increases, the hamstrings have an increased functional capacity for providing stability to the knee joint [21].

Statistical Analyses

A priori power analyses (G*Power 3.1) indicated that a sample size of 9 subjects resulted in statistical power values of 0.80 or greater for all the dependent variables. Separate two-way repeated measures (time [Pre, Post0, 24hr, 48hr] × protocol: [Control, HE, SLRD] analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to examine the potential changes of each dependent variable over time among different protocols. When appropriate, follow-up tests included one-way repeated measures ANOVAs and pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustments. All statistical tests were conducted using a statistical software (IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0, Armonk, NY), with alpha set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations (SD) for hamstrings muscle thickness, muscle stiffness, knee flexion eccentric peak torque, knee extension concentric peak torque, and functional hamstring eccentric/quadriceps concentric ratio.

TABLE 1.

Mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) before (Pre), immediately after (Post-0), 24 hours after (Post-24), and 48 hours after (Post-48) the repeated sprints for muscle thickness, muscle stiffness, knee flexion eccentric peak torque, knee extension concentric peak torque, and functional hamstring to quadriceps strength ratios (f-H:Q ratio).

| Pre | Post-0 | Post-24 | Post-48 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle thickness (mm) | CON HE SLW |

17.27±2.81 17.41±3.09 17.05±2.58 |

19.16±2.46 19.21±3.03 18.70±2.44 |

19.56±2.59 21.20±1.87 20.55±1.92 |

18.79±2.54 20.63±2.25 17.57±2.05 |

| Muscle stiffness (m/s) | CON HE SLW |

1.28±0.47 1.26±0.29 1.39±0.38 |

1.59±0.32 1.64±0.39 1.61±0.45 |

1.87±0.19 1.93±0.34 1.65±0.42 |

1.88±0.20 1.89±0.21 1.47±0.39 |

| Knee flexion eccentric peak torque (N-m) | CON HE SLW |

134.84±36.96 132.20±32.71 136.67±35.07 |

66.66±25.25 67.93±12.91 99.16±17.45 |

79.97±23.12 76.76±15.86 107.23±25.23 |

95.99±23.73 94.75±23.01 134.18±29.98 |

| Knee extension concentric peak torque (N-m) | CON HE SLW |

129.40±48.07 126.61±50.77 127.11±48.61 |

107.50±43.96 109.79±47.48 113.24±40.92 |

112.10±49.36 113.49±42.42 109.22±40.30 |

111.23±53.23 112.98±38.35 116.87±44.73 |

| f-H:Q ratio | CON HE SLW |

1.12±0.36 1.18±0.46 1.17±0.37 |

0.66±0.24 0.70±0.22 0.96±0.30 |

0.78±0.27 0.76±0.30 1.07±0.31 |

1.00±0.35 0.89±0.22 1.27±0.38 |

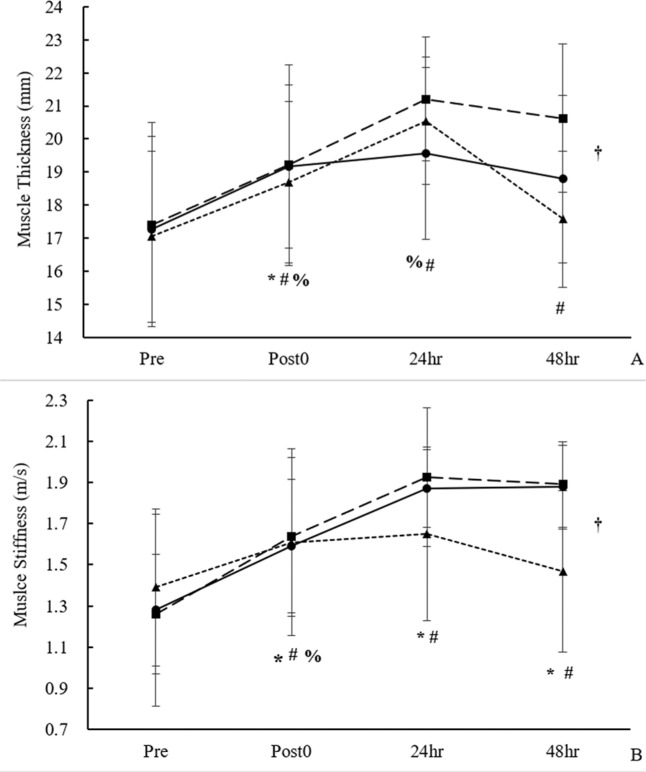

For muscle thickness, the 2-way repeated measures ANOVA indicated that there was a time × protocol interaction (p = 0.004). The follow-up analyses showed significant muscle thickness increase from Pre to 24hr for control (p = 0.037); from Pre to Post0 (p = 0.002), from Pre to 24hr (p = 0.002), from Pre to 48hr (p = 0.021), and from Post0 to 24hr (p = 0.038) for HE; and from Pre to Post0 (p = 0.029), from Pre to 24hr (p < 0.001), from Post0 to 24hr (p = 0.013), but significant decrease from 24hr to 48hr (p < 0.001) for SLRD. In addition, the muscle thickness was significantly lower for SLRD than that for HE at 48hr (p = 0.03) (Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Muscle thickness (A) and muscle stiffness (B) before (Pre), immediately after (Post0), 24 hours after (24hr), and 48 hours after (48hr) the repeated sprints.

Solid line with round dots: regular warm-up (Control); Long dash line with square dots: regular warm-up with a set of hyperextension off table exercise (HE); Short dash line with triangle dots: regular warm-up with a set of single leg Romanian deadlift (SLRD)

*: significant difference between different time points for Control (p < 0.05); #: significant difference between different time points for HE (p < 0.05); %: significant difference between different time points for SLRD (p < 0.05); †: significant difference between different protocols (p < 0.05).

For muscle stiffness, there was a significant 2-way interaction (p = 0.001). The follow-up analyses indicated that muscle stiffness significantly increased from Pre to Post0, from Pre to 24hr, from Pre to 48hr, and from Post0 to 24hr for Control and HE; and only from Pre to Post0 (p = 0.047) for SLRD. In addition, the muscle stiffness was significantly lower for SLRD than those for both Control (p = 0.031) and HE (p = 0.019) at 48hr (Figure 1B).

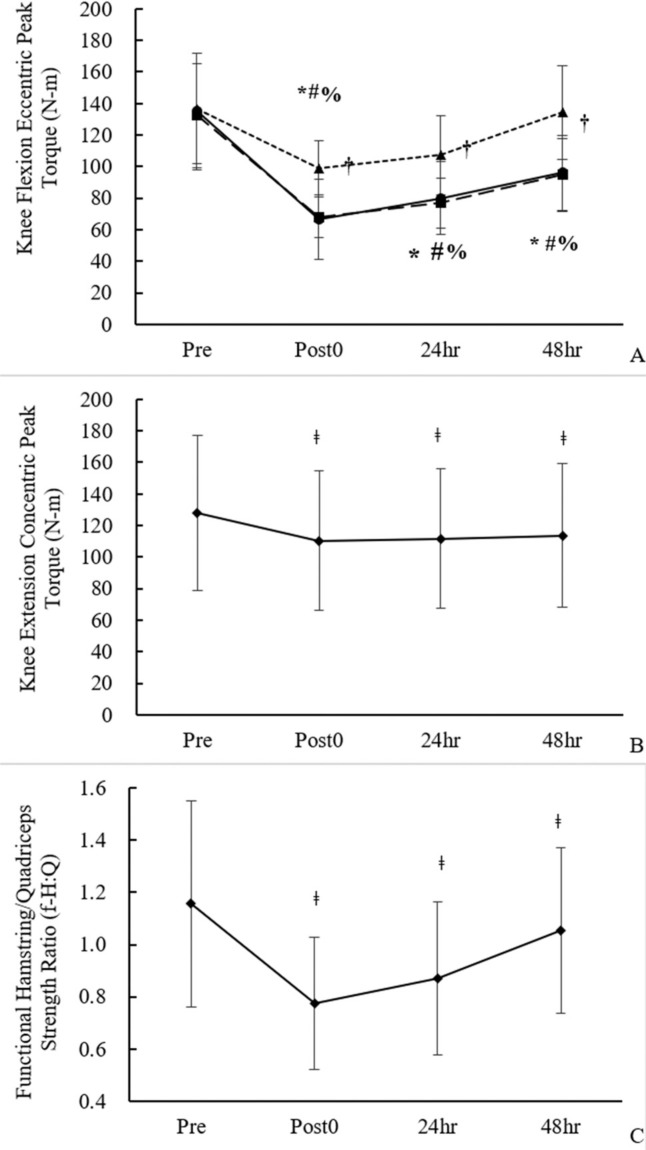

For knee flexion eccentric peak torque, there was a significant 2-way interaction (p < 0.001). The follow-up analyses revealed that the knee flexion eccentric peak torque significantly decreased from Pre to Post0, from Pre to 24hr, from Pre to 48hr, but increased from Post0 to 48hr and from 24hr to 48hr for both Control and HE. The SLRD shared the similar patterns as the other two conditions, but the peak torque at 48hr showed no significant difference from the Pre value. In addition, at Post0, 24hr, and 48hr, the peak torque values for SLRD were significantly greater than those from other protocols (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Knee flexion eccentric peak torque (A), knee extension concentric peak torque (B), and functional hamstrings/quadriceps strength ratio (C) before (Pre), immediately after (Post0), 24 hours after (24hr), and 48 hours after (48hr) the repeated sprints.

Solid line with round dots: regular warm-up (Control); Long dash line with square dots: regular warm-up with a set of hyperextension off table exercise (HE); Short dash line with triangle dots: regular warm-up with a set of single leg Romanian deadlift (SLRD)

Sub-figures B and C are demonstrating the combined mean values across three interventions (Control, HE, and SLRD).

: significant difference between different time points for combined mean values (p < 0.05)

*: significant difference between different time points for Control (p < 0.05); #: significant difference between different time points for HE (p < 0.05); %: significant difference between different time points for SLRD (p < 0.05); †: significant difference between different protocols (p < 0.05)

For knee extension concentric peak torque, the 2-way repeated measures ANOVA showed no significant interaction (p = 0.851). However, there was a significant main effect for time (p < 0.001). When collapsed across protocol, the combined mean knee extension concentric peak torque value significantly decreased from Pre to Post0 (p < 0.001), from Pre to 24hr (p = 0.012), and from Pre to 48hr (p = 0.04) (Figure 2B).

For functional hamstring/quadriceps strength ratio (f-H:Q), there was no significant 2-way interaction (p = 0.073). However, there were main effects for both time (p < 0.001) and protocol (p = 0.006). When collapsed across protocol, the combined mean ratio significantly decreased from Pre to Post0 (p < 0.001) and from Pre to 24hr (p < 0.001), but significantly increased from Post0 to 48hr (p = 0.028) and from 24hr to 48hr (p = 0.034) (Figure 2C). When collapsed across time, the combined mean ratio for SLRD was significantly greater than that for Control (p = 0.023), but a trend toward significance for HE (p = 0.053).

DISCUSSION

The main purpose of this study was to examine the effects of a regular warm-up combined with different hamstring exercises on muscle damage markers following a muscle-damaging exercise protocol (repeated maximal sprints). First of all, our results confirmed that the repeated sprints induced a large degree of muscle damage in all three interventions. This damage was qualified by indirect markers that included prolonged depression of muscle strength [22], accompanied with the elevated muscle thickness [23] and muscle stiffness [24] for at least 24 hours following the sprints.

With the presence of the sprinting-induced muscle damage, a novel finding of this investigation is that the combination of the regular warm-up exercise with one set of SLRD prior to the maximal sprints resulted in significantly less muscle damage and faster recovery than the other two conditions (Control and HE). Specifically, 48 hours following the repeated sprints, the values for muscle thickness, muscle stiffness, and knee flexion eccentric strength returned to baseline for SLRD, and they were different from the values of the other two conditions. In addition, as a common HSI risk factor, the combined (across three interventions) functional hamstring to quadriceps strength ratio returned to baseline, with the SLRD showing significantly greater treatment effect than the Control, and a near-significance greater effect than the HE. All these findings indicate the superior effects of adding 12 repetitions of SLRD on protecting against the subsequent sprinting-induced muscle damage than other two warm-up interventions.

It has been reported that low-intensity (varied between 10% and 40% of MVIC) preconditioning eccentric exercise can attenuate subsequent maximal or submaximal eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage and accelerate the recovery [25, 26]. This protective effect has been attributed to several different mechanisms, including neural, mechanical, and cellular adaptations [27]. From the same group of researchers [28], this low-intensity eccentric exercise-induced protective effect can last up to two weeks. A main difference between the current investigation and the previous studies, however, should be pointed out: unlike the previous experiments during which the researchers delivered the muscle damaging protocols at least 2 days after the preconditioning eccentric exercise, our subjects performed the repeated sprints immediately after the preconditioning exercises (HE and SLRD). As far as we know, this is the first investigation to examine the influence of adding a set of resistance exercise (HE or SLRD) to regular warm-up protocol on exercise-induced muscle damage. In addition, only 12 repetitions of SLRD was sufficient to attenuate the sprinting-induced muscle damage. Thus, the protection from adding a set of SLRD was effective immediately. Similar to the current research design, our previous experiment suggested that a bout of static active stretching right before a muscle-damaging eccentric exercise protocol can also attenuate muscle damage [14].

Unlike the SLRD, adding a set of HE seemed to exacerbate the sprint-induced muscle damage. Several mechanisms might have influenced this result. First, it could be possibly due to the different muscle activation strategies used in two exercises. According to Zebis et al. [19] the HE specifically targets the biceps femoris muscle during the concentric shortening phase, requiring relatively high level of muscle activity for the hamstring muscles (75-87% of the maximal EMG amplitude). On the other hand, electrical activity measured in the hamstring muscles during the SLRD exercise were low (<50% of the maximal EMG amplitude), with greater muscle activation recorded during the lengthening phase [18). Therefore, the SLRD could have served as a low-intensity preconditioning eccentric exercise protocol, attenuating the subsequent sprinting-induced muscle damage. However, the concentric-based HE exercise was not likely to induce the protective effect for the following muscle-damaging sprints. This hypothesis is supported by a previous report where a bout of light concentric exercise showed no effect on the recovery of subsequent eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage [29]. Second, due to the high-intensity nature of the HE, local muscle temperature probably increased more than the SLRD situation. According to Evans et al. [30] active warm-up non-fatiguing protocol (elbow flexion exercise) increased biceps muscle temperature by 1°C, but exhibited a greater circumferential increase than controls did following the muscle-damaging protocol. The authors [30] attributed this to active exercise-induced higher myotatic feedback loop activation and increased stiffness, which might have limited fiber elongation, thereby increasing the chance of fiber strain damage during eccentric exercise [31]. In addition, we have anecdotally observed that some subjects viewed the HE protocol as a relatively intense workout, which might have exacerbated the muscle-damaging effects of that exercise.

Limitations

The novel findings of this investigation must be balanced against some limitations. First and foremost, even though all the preconditioning exercises were short in duration and low in volume, we do not know for sure how long the preconditioning effect would last. If the effect could have lasted more than a week, then it indeed could have influenced the results. Second, we are not able to provide more specific details regarding the physiological mechanisms associated with the SLRD-induced protective effect. Indeed, changes in neural, mechanical, and cellular factors following low-intensity eccentric contractions could all elicit acute adaptations contributing to our results. However, considering the protective effect happened immediately, it is likely that neural factors played a more important role. Thus, future research should focus on quantifying the contribution from each factor under different exercising conditions.

CONCLUSIONS

Adding a set of SLRD to a regular warm-up protocol prior to repeated sprints has superior effect on recovery from repeated maximal sprinting-induced muscle damage than regular warm-up exercise only and the combination of regular warm-up with HE exercise. Muscle damage markers and hamstring performance retuned to baseline 48 hours after the muscle-damaging protocol. A possible explanation is that the eccentric-based SLRD exercise imposed a protective effect against the following sprinting exercise. Practically, athletes who have high density competition schedules (e.g., competing 2-3 times per week) during the competition season, adding a set of SLRD to the regular warm-up prior to the competition may help facilitate the recovery from sprint-induced muscle damage, thus to potentially enhance the sports performance and to decrease the possibility of HSIs for the following competitions.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank all the participants who took time out of their schedules to help with this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Askling CM, Tengvar M, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Acute first-time hamstring strains during high-speed running: a longitudinal study including clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):197–206. doi: 10.1177/0363546506294679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonhagen S, Nemeth G, Eriksson E. Hamstring injuries in sprinters. The role of concentric and eccentric hamstring muscle strength and flexibility. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(2):262–6. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansson PH, Lindstrom L, Sundelin G, Lindstrom B. The effects of preexercise stretching on muscular soreness, tenderness and force loss following heavy eccentric exercise. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1999;9(4):219–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1999.tb00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keane KM, Salicki R, Goodall S, Thomas K, Howatson G. Muscle Damage Response in Female Collegiate Athletes After Repeated Sprint Activity. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(10):2802–7. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howatson G, Milak A. Exercise-induced muscle damage following a bout of sport specific repeated sprints. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(8):2419–24. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181bac52e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timmins RG, Opar DA, Williams MD, Schache AG, Dear NM, Shield AJ. Reduced biceps femoris myoelectrical activity influences eccentric knee flexor weakness after repeat sprint running. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(4):e299–305. doi: 10.1111/sms.12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thelen DG, Chumanov ES, Hoerth DM, Best TM, Swanson SC, Li L, et al. Hamstring muscle kinematics during treadmill sprinting. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(1):108–14. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000150078.79120.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Croisier JL, Ganteaume S, Binet J, Genty M, Ferret JM. Strength imbalances and prevention of hamstring injury in professional soccer players: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(8):1469–75. doi: 10.1177/0363546508316764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmitt B, Tim T, McHugh M. Hamstring injury rehabilitation and prevention of reinjury using lengthened state eccentric training: a new concept. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2012;7(3):333–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aquino CF, Fonseca ST, Goncalves GG, Silva PL, Ocarino JM, Mancini MC. Stretching versus strength training in lengthened position in subjects with tight hamstring muscles: a randomized controlled trial. Man Ther. 2010;15(1):26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behm DG, Blazevich AJ, Kay AD, McHugh M. Acute effects of muscle stretching on physical performance, range of motion, and injury incidence in healthy active individuals: a systematic review. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(1):1–11. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woods K, Bishop P, Jones E. Warm-up and stretching in the prevention of muscular injury. Sports Med. 2007;37(12):1089–99. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737120-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fradkin AJ, Gabbe BJ, Cameron PA. Does warming up prevent injury in sport? The evidence from randomised controlled trials? J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9(3):214–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen CH, Chen TC, Jan MH, Lin JJ. Acute effects of static active or dynamic active stretching on eccentric-exercise-induced hamstring muscle damage. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2015;10(3):346–52. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2014-0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Attar WSA, Soomro N, Sinclair PJ, Pappas E, Sanders RH. Effect of Injury Prevention Programs that Include the Nordic Hamstring Exercise on Hamstring Injury Rates in Soccer Players: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine. 2017;47(5):907–16. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0638-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bourne MN, Duhig SJ, Timmins RG, Williams MD, Opar DA, Al Najjar A, et al. Impact of the Nordic hamstring and hip extension exercises on hamstring architecture and morphology: implications for injury prevention. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(5):469–77. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin MJ, Chen TC, Chen HL, Wu BH, Nosaka K. Low-intensity eccentric contractions of the knee extensors and flexors protect against muscle damage. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2015;40(10):1004–11. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsaklis P, Malliaropoulos N, Mendiguchia J, Korakakis V, Tsapralis K, Pyne D, et al. Muscle and intensity based hamstring exercise classification in elite female track and field athletes: implications for exercise selection during rehabilitation. Open Access J Sports Med. 2015;6:209–17. doi: 10.2147/OAJSM.S79189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zebis MK, Skotte J, Andersen CH, Mortensen P, Petersen HH, Viskaer TC, et al. Kettlebell swing targets semitendinosus and supine leg curl targets biceps femoris: an EMG study with rehabilitation implications. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(18):1192–8. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayala F, De Ste Croix M, Sainz De Baranda P, Santonja F. Acute effects of static and dynamic stretching on hamstring eccentric isokinetic strength and unilateral hamstring to quadriceps strength ratios. J Sports Sci. 2013;31(8):831–9. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2012.751119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harter RA, Osternig LR, Standifer LW. Isokinetic evaluation of quadriceps and hamstrings symmetry following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71(7):465–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warren GL, Lowe DA, Armstrong RB. Measurement tools used in the study of eccentric contraction-induced injury. Sports Med. 1999;27(1):43–59. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199927010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nosaka K, Clarkson PM. Changes in indicators of inflammation after eccentric exercise of the elbow flexors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28(8):953–61. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199608000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howell JN, Chleboun G, Conatser R. Muscle stiffness, strength loss, swelling and soreness following exercise-induced injury in humans. J Physiol. 1993;464:183–96. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen TC, Tseng WC, Huang GL, Chen HL, Tseng KW, Nosaka K. Low-intensity eccentric contractions attenuate muscle damage induced by subsequent maximal eccentric exercise of the knee extensors in the elderly. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113(4):1005–15. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2517-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavender AP, Nosaka K. A light load eccentric exercise confers protection against a subsequent bout of more demanding eccentric exercise. J Sci Med Sport. 2008;11(3):291–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McHugh MP. Recent advances in the understanding of the repeated bout effect: the protective effect against muscle damage from a single bout of eccentric exercise. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2003;13(2):88–97. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.02477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen HL, Nosaka K, Chen TC. Muscle damage protection by low-intensity eccentric contractions remains for 2 weeks but not 3 weeks. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(2):555–65. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-1999-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zainuddin Z, Sacco P, Newton M, Nosaka K. Light concentric exercise has a temporarily analgesic effect on delayed-onset muscle soreness, but no effect on recovery from eccentric exercise. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006;31(2):126–34. doi: 10.1139/h05-010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans RK, Knight KL, Draper DO, Parcell AC. Effects of warm-up before eccentric exercise on indirect markers of muscle damage. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(12):1892–9. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200212000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hardy L, Lye R, Heathcote A. Active versus passive warm up regimes and flexibility. Carnegie Res Papers. 1983;1:23–30. [Google Scholar]