Abstract

To determine the effect of carbohydrate mouth rinsing (CHO-MR) on physical and cognitive performance during repeated-sprints (RS) after 3 days of intermittent fasting (abstaining from food and fluid 14 h per day). In a randomized and counter-balanced manner 15 active healthy males in a fasted state performed a RS-protocol [RSP; 2 sets (SET1 and SET2) of 5×5 s maximal sprints, with each sprint interspersed with 25 s rest and 3 min of recovery between SET1 and SET2] on an instrumented non-motorized treadmill with embedded force sensors under three conditions: i) Control (CON; no-MR), ii) Placebo-MR (PLA-MR; 0% maltodextrin) and iii) CHO-MR (10% maltodextrin). Participants rinsed their mouth with either 10 mL of PLA-MR or CHO-MR solution for 5 s before each sprint. Sprint kinetics were measured for each sprint and reaction time (RTI) tasks (simple and complex) were assessed pre-, during- and post-RSP. There was no statistical main effect of CHO-MR on mean power, mean speed, and vertical stiffness during the sprints between the PLA-MR and CON condition. Additionally, no statistical main effect for CHO-MR on accuracy, movement time and reaction time during the RTI tasks was seen. CHO-MR did not affect physical (RSP) or cognitive (RTI) performance in participants who had observed 3 days of intermittent fasting (abstaining from food and fluid 14 h per day).

Keywords: Repeated sprint ability (RSA), Reaction time, Movement time, Accuracy, Brain

INTRODUCTION

Muslims commonly fast during the holy month of Ramadan, or on occasions three days of the month throughout the year (intermittent fasting; 3d-IF). During Islamic religious fasting, Muslims abstain from consuming both food and fluid during daylight hours. Daylight fasting has been reported to reduce physical and cognitive performance [1], although the magnitude of this response has been debated [2, 3]. Despite these fasting-mediated challenges to cognitive processes and physical performance [1] many Muslim athletes, and those that voluntarily fast, may still need/wish to train and/or compete. Within fasted participants simple strategies such as mouth rinsing (MR) with either Carbohydrate (CHO) or water have shown efficacy to acquiesce some of the fasting induced endurance [4] and high-intensity [5] exercise performance decrements. Performance improvements through CHO-MR is dependent on several debated factors, including the fasted or fed state of participants [6], a dose response to the duration of MR (5 or 10 s [7]), concentration of the CHO rinse, the rinsing frequency [8] and the exercise mode [9]. Positive effects are principally attributed to orally-mediated activation of brain regions associated with motivation [10, 11] and attentional processing [12]. Activation of higher centers in response to CHO-MR has been shown through electroencephalogram (EEG) analysis [10], specifically brain regions attributed to reward and motor control (primary and putative secondary taste cortices in the orbitofrontal cortex [12, 13]).

The ability to repeatedly express and recover from near maximal sprints [i.e. repeated-sprint-ability (RSA)] is a key physical attribute in many team-sports, with RSA central to many training programs [14]. Despite a growing number of publications regarding the effect of CHO-MR on performance during high-intensity exercise lasting ~1 h [6, 9, 15]. The effect of 10% CHO-MR on participants in a fasted state, relative to short intensive exercise (e.g. RSA) accompanied by assessment of cognitive performance (e.g. reaction time and mechanical/movement quality), has not been performed. Given the cognitive demands of both playing [16] and officiating [17] team sports match-play, whether recreationally or at an elite level, these latter cognitive considerations should also be of concern to the fasting athlete/official and their support network, in addition to physical performance related agendas.

Therefore, the present study examined the effects of CHO-MR after 3d-IF (consisting of ~14 h of total fasting per day, i.e., no ingestion of food and fluid) on RSA specific physical and cognitive performance in recreational participants. It was hypothesized that the use of CHO-MR would positively influence (i) RSA specific physical performance indices and (ii) the employed cognitive measures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fifteen healthy, recreationally active males (30.7±4 yrs, 82.8±5 kg and 181.0±6 cm, frequency of exercise 4.6±1.0 times/week) volunteered for participation giving their written informed consent. The study was approved by the Anti-Doping-Lab of Qatar (ADLQ) Ethics Committee (F2015000116).

Participants reported to the laboratory on four separate occasions: Visit 1 (familiarization): Participants were familiarized to experimental MR solutions and their procedures prior to anthropometric data, body mass (precision 0.1 kg) and height (Seca-769-digital medical) being measured. Participants were also familiarized with the cognitive testing protocol [reaction time tasks (RTI)] [18].

Given the treadmill (ADAL3D-WR, Medical Development—HEF Tecmachine, Andrézieux-Bouthéon, France) employed was operated in a motorized (first part of warm-up) and non-motorized ‘constant motor torque mode’ (last part of warm-up and repeated sprint protocol (RSP); see below and [19]) manner, specific familiarization to each mode was performed. The RSP familiarization also provided determination of a participants maximal power output during sprinting [20, 21]. This value was used to determine whether participants were expressing maximal efforts in the first sprint of each completion of the RSP (i.e. criterion value) to ensure that adoption of a prospective pacing strategy was not seen (all observed experimental values were within ± 5% of this criterion). Importantly, participants were provided with standardized strong verbal encouragement when performing sprints.

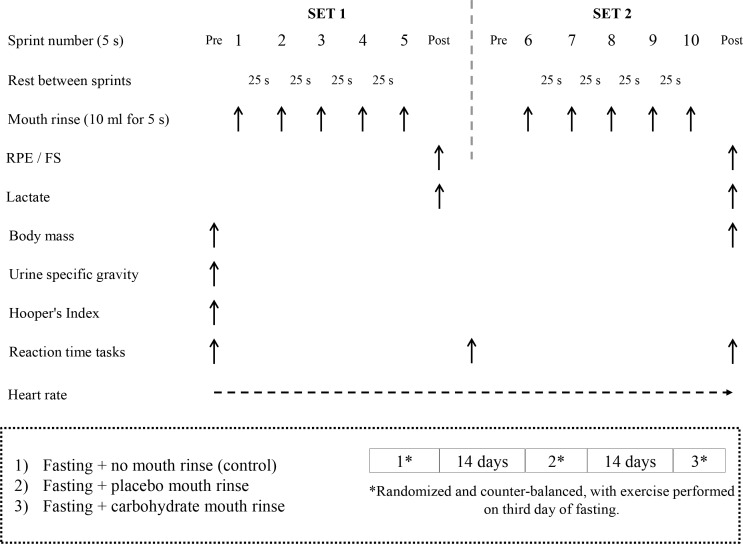

Visits 2-4 (experimental): Three conditions were employed: control (CON; no-MR), placebo-MR (PLA-MR; 0% maltodextrin), and CHO-MR (10% maltodextrin). Administered in a randomized and counter-balanced manner, separated by at least 2 weeks (see Figure 1 for schematic of experimental design). Participants reported to the laboratory in the afternoon following total fasting of 14 h per day, for the 3 prior consecutive days. All exercise trials were performed at the same time of the day (between 14:00-16:00) to avoid circadian variation [12], the first laboratory arrival time was used across each further experimental visit. Participants performed the reaction time tests (RTI; simple and complex) and repeated sprint protocol (RSP) on each visit. All experimental procedures occurred in a standardized chronological order within standardized environmental conditions (22.7±1.1ºC and 46.03±3.5% relative humidity).

FIG. 1.

Study design. Repeated-sprints protocol: [2sets: (5 x 5 s maximal sprints (25 s passive recovery between sprints) with 3 min recovery in-between sets]. A Heart rate (HR) monitor continuously recorded HR throughout the experiment. In the 2 mouth rinse trials (carbohydrate and placebo), each participant mouth rinsed the solution before each sprint. At Pre SET1: Urine and blood capillary samples (lactate) collection; body mass, Hooper’s index and height measurement; Reaction time tasks (RTI) were assessed before starting the warm up. At Post SET1 and during the 3 min of recovery: Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE), feeling scales (FS) and lactate were collected before starting the RTI test. At Post SET2: RPE, FS and lactate were collected before starting the RTI test and body mass measurement. The three experimental trials were separated by 15 days each and conducted in fasted state in a randomized and counter-balanced.

Experimental Day Procedures: Anthropometrics were assessed as previously described. Urine samples were collected upon arrival to assess urine-specific gravity (USG; Digital Pocket Refractometer, Atago 4410 PAL-10S, West Sussex, UK). If the USG value was outside of 1.005 – 1.030 [22], a participant was excluded (n = 1). Seated finger capillary blood samples were collected to determine resting pre-RSP blood lactate concentration (Lactate Scout+, Barleben, Germany). Hooper’s [23] index questionnaires (i.e., summation of the subjective ratings of sleep quality, fatigue, stress and muscle soreness) were administered to assess participant’s wellness. RTI was administered pre-RSP.

RSP and related procedures: Prior to the RSP, participants underwent a standardized warm-up: (i) 1 min at 8 km.h-1, 1 min at 9 km.h-1 and finally 8 min at 10 km.h-1 (10 min total running time) on the treadmill (motorized mode), followed by (ii) 5 to 6 min of sprint-specific dynamic stretching and skipping muscular warm-up exercises off the treadmill, and (iii) 10 to 13 min of interval treadmill-sprints (non-motorized mode) [24]. Warm-up duration was consistent within participants for the 3 conditions (total time range: 25 – 28 min). The RSP was composed of two sets (SET1 and SET2) of repeated-sprints, separated by 3 min recovery. Each SET consisted of five sprints (maximal 5 s sprints), separated by 25 s passive recovery (figure 1). Heart rate (HR; Polar S-810, Kempele, Oy, Finland) was continuously monitored, with mean peak cardiac frequency (HRpeak) calculated for each set using commercially available software (Polar Pro Trainer 5, Bethpage, NY, USA).

Treadmill: The validated instrumented treadmill ergometer allowed the participants to sprint against the resistance of a tethered belt, in the non-motorized mode [19]. The motor torque was set between 140% and 160% of the default torque necessary to overcome the friction on the belt due to the participant’s body weight. This allowed participants to sprint in a maximal manner whilst minimizing participant risk of losing balance. A belt attached to a stiff rope (1 cm in diameter, ~3 m in length) was used to tether participants to an anchor point on the wall behind them. An additional overhead safety harness with sufficient slack not to impede natural running mechanics was also fastened to the participants. When correctly attached, participants could lean forward in a crouched sprint-start position with their preferred foot forward. This starting position was standardized and consistently used in all sprint efforts. For each sprint, following a 5 s verbal and visual countdown, the treadmill was released and the belt began to accelerate as a result of participants applying a positive (i.e., propulsive) horizontal force, i.e. the start of the sprint.

The following procedures were administered post SET1 and SET2 of the RSP, whilst participants were stood on the braked treadmill. Rating of perceived exertion (RPE; 1 – 10 scale [25]) and subjective ratings for pleasantness (feeling scale; FS) using a ‘feeling scale’ (+2= very pleasant, 1= pleasant, 0= neutral, -1= unpleasant and -2= very unpleasant [26]), immediately followed by a standing capillary blood sample, after which the harness was removed. Participants then stepped off the treadmill and completed the RTI procedures in a standardized standing position, taking between 60 – 90 s. A final body mass measure was taken after the final RTI post SET2 procedure was completed. The intervention procedures (CHO-M or PLA-MR) were administered prior to each sprint (see below).

Mouth rinse solutions and protocol: A single blind design was employed, whereby all but the principal investigator were blinded to MR solution. Solutions were prepared daily by the principal investigator and kept at room temperature. The 10% CHO-MR solution (10% w/v) contained 12 g of commercially available maltodextrin powder (SIS company, Nelson, UK) dissolved in a final volume 120-ml of distilled water. The PLA-MR solution was obtained from a commercially available non-caloric effervescent tablet (GO Hydro-SIS company, Nelson, UK), one tablet per 1000 ml of distilled water. Both solutions were indistinguishable in regard to color, odor, and taste. MR consisted of rinsing with 10 mL of solution for ~5 s and then expectoration of the solution into an empty plastic cup. Participants were instructed to thoroughly swill the fluid throughout their oral cavity for the MR duration. The MR fluid was weighed before and after each rinse using an electronic balance (Ohaus, New Jersey, USA) to assess the potential quantity of solution that could have remained in the oral cavity. The fluid was expressed by mass with the assumption that 1 g of the beverage equals 1 mL [7, 13]. Pilot testing with various volumes (5, 10, 20 and 25 ml) demonstrated that the 25 ml MR volume, although used elsewhere in resting participants [10], was not compatible with the vigorous exercise associated with the RSP.

RTI: The Cambridge Battery of Tests from the Cantab software (CANTABeclipse, Cambridge, UK) and hardware suite [27] were used to assess RTI, through a touch screen computer and a button box. Participants completed these RTI tasks in a standardized standing position, within an environmentally and noise-controlled room, with standardized verbal instructions provided to participants. Specifically, the RTI test measures movement time, reaction time and response accuracy. The overall task was divided into five stages, which require increasingly complex chains of responses. The RTI test outcome measures were divided into simple and complex reaction scores. Each measure was obtained by averaging the score over four trials. In the simple-RTI, a yellow dot appeared on the black screen in one pre-determined location whilst in the complex-RTI, the yellow dot appeared in one of five pre-determined different locations. At the sight of the dot appearing on the screen, the participant had to release the button and immediately hit the dot on the screen in the fastest time possible. In line with manufacturer’s instructions, the computer software defined reaction time (as the time taken between the dot appearance on the screen and button being released), movement time (time between button release and screen touch) and response accuracy (hitting or missing the target area) as previously described [28].

Treadmill biomechanical parameters: The three-dimensional ground reaction force (GRF) and treadmill belt velocity were sampled at 1,000 Hz over the 5 s sprints, and digitally filtered with a zero phase-lag fourth-order Butterworth low-pass filter with a 30 Hz cut-off. Sprint onset was defined as the time when the belt speed exceeded 0.2 m · s-1. For each step, power in the anterior-posterior direction was computed as P = FHV, where FH is the horizontal GRF, and V is the treadmill belt velocity [21]. Vertical stiffness (Kvert) was calculated as Kvert = Fmax/ΔCOM, where Fmax is the vertical GRF peak, and ΔCOM is the maximum vertical displacement of the center of mass, which was calculated by integrating the vertical acceleration twice with respect to time [20]. All calculations were processed using a custom written Matlab (MathWorks, Version 8.4) program.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 21.0. All values are presented as means±SD. The data was screened for outliers and deviation from normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. USG and resting pre-RSP blood lactate values were not normally distributed and were thus log transformed with associated p-values based on a non-parametric equivalent (Friedman’s ANOVA). A two way repeated measures ANOVA was used to determine: the effect of condition (PLA-MR, CON, and CHO-MR) and time (sprint 1 to 10) on mean power, mean speed and vertical stiffness, and the effect of condition (PLA-MR, CON, and CHO-MR) and time (pre-, mid- and post-RSP) on cognitive parameters (RTI simple and complex). A Linear Mixed Model was performed to analyze the effect of condition on RTI parameters at mid- and post-RSP after adjusting for pre-RSP RTI parameters. If a primary significant difference was observed, the post-hoc Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used to detect where the differences occurred. The level of two tailed statistical significance was set at p<0.05 with effect sizes (ES) calculated from Partial Eta-squared. A large effect size was determined as ≥0.25, medium as >0.09 and small as ≤0.09 [29].

RESULTS

No effect of condition on all physiological measures were seen (table 1). No effect of condition (PLA-MR, CON, and CHO-MR) and time (sprint 1 to 10) on mean power (P=0.630, ES=0.032), mean speed (P=0.835, ES=0.014) and vertical stiffness (P=0.670, ES=0.030) (table 2), and on cognitive parameters (RTI simple and complex) (table 3), were observed. Specifically, no effect of condition on RTI tests of accuracy (simple P=0.357, ES=0.071; complex P=0.259, ES=0.092), movement time (simple P=0.546, ES=0.042; complex P=0.902, ES=0.007), and reaction time (simple P=0.514, ES=0.046; complex P=0.758, ES=0.020) were seen. No significant differences were present for USG, mean HR, blood lactate and RPE throughout the exercise (all p>0.05) between conditions. The mean expectorated volume per MR did not statistically differ (P=0.871) between conditions (CHO-MR: 9.97±0.15 ml; PLA-MR 9.98±0.13 ml) inclusive of saliva volume. Participants (CHO-MR 75%; PLA-MR 67%) generally reported MR solutions to be of a pleasant taste.

TABLE 1.

Physiological parameters, Hooper’s index, urine samples and sleep reported duration during the 24 h preceding the experimental testing collected at pre-RSP; Blood capillary samples (Lactate), RPE and HR taken at pre-, mid and post-RSP (mean ± SD; statistical outcome and P-value) of participants (n=15) in Control, CHO-MR and PLA-MR conditions.

| Control | CHO-MR | Placebo-MR | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Night (h) | 7.03±3.03 | 6.57±1.94 | 6.87±2.22 | 0.74 |

| Total Sleep (h) | 7.53±2.60 | 7.24±1.68 | 7.33±2.09 | 0.91 |

| Hooper’s Index (au) | 8.93±4.06 | 9.20±3.61 | 9.27±3.22 | 0.96 |

| Body mass loss (kg) | 0.46±0.14 | 0.55±0.16 | 0.50±0.12 | 0.20 |

| USG pre (au) | 1.028±0.015 | 1.023±0.002 | 1.023±0.048 | 0.96 |

| Pre-Lactate (mmol/L) | 0.93±0.44 | 1.00±0.60 | 0.89±0.34 | 0.92 |

| Mid-Lactate (mmol/L) | 9.51±2.82 | 8.51±3.22 | 10.03±3.13 | 0.31 |

| Post-Lactate (mmol/L) | 12.06±3.41 | 11.22±2.44 | 11.37±2.89 | 0.51 |

| Mid-RPE (au) | 5.00±1.56 | 5.15±2.13 | 4.80±1.21 | 0.77 |

| Post-RPE (au) | 5.87±1.64 | 5.53±1.51 | 5.50±1.40 | 0.68 |

| HR-Pre (bpm) | 81.3±15.3 | 76.0±10.1 | 74.5±9.8 | 0.29 |

| HR-Mid (bpm) | 140.5±15.5 | 136.7±16.7 | 130.7±21.3 | 0.34 |

| HR-Post (bpm) | 136.1±14.5 | 135.1±14.9 | 136.4±17.4 | 0.97 |

RPE – Rating of Perceived Exertion; HR- Heart rate; Hooper’s Index: summation of self-ratings of fatigue, stress, delayed onset muscle soreness and sleep; au: arbitrary units; CHO-MR: Carbohydrate mouth rinse solution; USG: Urine-specific gravity.

Pre: resting pre RSP, Mid: during the 3-minutes of recovery in-between 2 sets and Post: at post RSP (repeated-sprint protocol).

TABLE 2.

Average maximal power (w/kg), maximal speed (m/s) and vertical stiffness (kN/m) of the participants during the three experimental conditions (CON, CHO-MR and PLA-MR) for 10 repeated sprints (S1 to S10) of 15 participants. Values are presented as means ± SD and range (minimum - maximum).

| Sprints | Maximal Power (w/kg) | Maximal Speed (m/s) | Vertical Stiffness (kN/m) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | CHO-MR | PLA-MR | CON | CHO-MR | PLA-MR | CON | CHO-MR | PLA-MR | |

| S1 | 15.4±4.2 | 14.1±3.8 | 13.7±3.6 | 4.7±0.9 | 4.5±0.9 | 4.5±0.8 | 95.8±18.7 | 92.7±18.7 | 92.6±15.3 |

| 15.1 (6.9-22.0) | 13.3 (6.3-19.6) | 14.9 (6.0-18.7) | 3.1 (2.9-6.0) | 3.1 (2.6-5.7) | 3.2 (2.9-6.1) | 59.2 (70.0-129.2) | 61.1 (66.8-127.9) | 49.1 (63.6-112.7) | |

| S2 | 13.1±3.3 | 12.8±3.5 | 13.3±3.9 | 4.4±0.8 | 4.3±0.8 | 4.3±0.9 | 87.8±18.1 | 89.0±17.5 | 87.9±15.7 |

| 13.3 (5.8-19.1) | 12.7 (5.9-18.6) | 13.2 (5.5-18.7) | 3.0 (2.5-5.5) | 2.9 (2.5-5.4) | 3.0 (2.5-5.5) | 63.6 (69.3-132.8) | 70.9 (55.5-126.4) | 45.2 (64.8-110.0) | |

| S3 | 12.8±4.3 | 12.6±3.9 | 12.2±3.8 | 4.2±1.0 | 4.3±0.9 | 4.3±1.0 | 85.9±18.8 | 85.5±16.9 | 84.8±13.2 |

| 14.3 (4.3-18.6) | 11.8 (6.0-17.8) | 14.6 (4.1-18.7) | 3.3 (2.3-5.6) | 2.9 (2.5-5.4) | 3.3 (2.3-5.7) | 49.0 (68.3-117.3) | 62.0 (52.6-114.6) | 61.1 (54.5-115.6) | |

| S4 | 11.6±3.8 | 15.1±3.7 | 13.9±3.7 | 4.1±0.9 | 4.7±0.9 | 4.5±1.0 | 84.4±18.3 | 83.7±16.5 | 84.2±13.2 |

| 13.5 (5.2-18.9) | 12.2 (5.5-17.8) | 13.9 (4.0-17.9) | 3.0 (2.6-5.6) | 2.9 (2.5-5.4) | 3.0 (2.6-5.6) | 53.4 (66.8-120.2) | 54.7 (66.0-120.7) | 63.4 (62.4-126.1) | |

| S5 | 13.6±3.9 | 13.3±3.7 | 13.0±4.1 | 4.4±1.0 | 4.4±0.9 | 4.3±1.0 | 82.6±19.2 | 83.6±18.1 | 83.0±12.1 |

| 14.3 (4.3-18.6) | 13.1 (5.6-18.7) | 14.9 (3.2-18.1) | 3.3 (2.2-5.5) | 3.0 (2.4-5.4) | 3.3 (2.3-5.5) | 54.5 (70.2-124.7) | 66.5 (54.3-120.8) | 38.5 (65.3-103.8) | |

| S6 | 13.6±4.44 | 12.1±5.0 | 13.1±4.1 | 4.4±1.0 | 4.4±1.0 | 4.4±1.0 | 88.7±19.0 | 84.7±19.1 | 91.4±16.7 |

| 14.8 (4.2-18.9) | 13.3 (5.9-19.2) | 14.9 (4.9-19.9) | 3.6 (2.1-5.7) | 3.0 (2.5-5.5) | 3.6 (2.1-5.7) | 64.7 (63.4-128.1) | 55.4 (54.9-110.3) | 63.5 (53.6-117.1) | |

| S7 | 12.6±3.5 | 12.5±3.9 | 15.0±3.4 | 4.3±0.9 | 4.3±1.0 | 4.6±0.7 | 87.3±16.5 | 83.5±22.0 | 87.4±17.2 |

| 16.2 (2.8-19.0) | 13.5 (5.4-18.9) | 18.1 (0.0-18.1) | 4.2 (1.5-5.6) | 3.2 (2.4-5.6) | 4.1 (1.5-5.6) | 57.7 (60.1-118.4) | 48.7 (61.8-110.4) | 56.9 (55.3-112.2) | |

| S8 | 14.0±3.5 | 13.8±3.3 | 13.5±3.5 | 4.5±0.8 | 4.4±0.8 | 4.4±0.8 | 83.6±20.2 | 80.6±17.2 | 84.8±15.7 |

| 16.6 (3.3-18.9) | 14.1 (4.5-18.6) | 14.9 (3.7-18.6) | 3.7 (1.9-5.6) | 3.4 (2.1-5.5) | 3.5 (1.9-5.6) | 52.0 (65.5-117.5) | 71.3 (55.5-126.8) | 60.0 (70.3-130.3) | |

| S9 | 13.2±3.5 | 14.1±3.8 | 13.4±4.1 | 4.4±0.8 | 4.5±0.8 | 4.4±1.0 | 80.3±19.5 | 79.3±17.2 | 82.8±13.9 |

| 15.5 (3.5-19.0) | 13.7 (4.9-18.6) | 11.9 (5.4-17.3) | 3.7 (1.9-5.6) | 3.3 (2.3-5.5) | 3.7 (1.9-5.6) | 47.7 (64.6-112.3) | 67.7 (54.2-121.9) | 53.8 (55.8-126.8) | |

| S10 | 13.1±3.7 | 12.6±3.7 | 12.9±3.6 | 4.3±0.9 | 4.2±0.9 | 4.3±0.9 | 82.9±21.4 | 81.3±18.8 | 86.4±17.1 |

| 15.1 (3.6-19.0) | 12.1 (6.9-19.1) | 14.6 (2.8-17.4) | 3.4 (2.1-5.5) | 3.0 (2.7-5.7) | 3.4 (2.1-5.5) | 49.9 (61.6-111.5) | 60.1 (66.5-126.6) | 71.3 (55.5-126.8) | |

No significant difference was observed between trials (P > 0.05).

TABLE 3.

Response times during cognitive testing. Mean values (± SD) (n=15) and range (minimum - maximum) of the accuracy (%), movement time (ms) and reaction time (ms) in simple and complex reaction time test (RTI), respectively at pre, mid and post-RSP in Control, PLA-MR and CHO-MR.

| RTI Accuracy score (%) |

RTI Movement time (ms) |

RTI Reaction time (ms) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Time | Simple | Complex | Simple | Complex | Simple | Complex |

| CON | Pre | 8.6±0.6 2 (7 – 9) |

7.4±0.8 3 (5 – 8) |

302.5±196.9 715 (123-837) |

198.0±69.2 272 (134-406) |

294.9±36.8 136 (234-370) |

317.3±38.8 146 (272-418) |

| Mid | 8.5±0.5 2 (7 – 9) |

7.5±0.7 2 (6 – 8) |

188.3±75.1 283 (112-395) |

180.1±37.5 133 (117-249) |

311.7±36.5 132 (252-384) |

316.2±35.9 111 (267-378) |

|

| Post | 8.4±0.7 2 (7 – 9) |

7.6±0.6 2 (6 – 8) |

223.2±86.3 284 (112-395) |

199.9±46.8 146 (120-265) |

305.4±55.5 175 (236-411) |

312.1±36.7 135 (252-387) |

|

| PLA-MR | Pre | 8.2±0.8 5 (7 – 12) |

7.8±0.4 1 (8 – 7) |

269.7±136.8 484 (128-612) |

180.1±27.4 99 (138-237) |

279.0±52.1 220 (226-446) |

294.4±36.9 143 (248-391) |

| Mid | 8.4±0.8 2 (7 – 9) |

7.9±0.4 1 (8 – 7) |

183.6±68.4 281 (121-402) |

188.6±46.6 168 (126-295) |

313.9±66.7 228 (239-467) |

310.5±39.6 148 (247-395) |

|

| Post | 8.7±1.1 2 (8 – 10) |

7.5±0.6 2 (8 – 6) |

231.9±84.9 331 (131-463) |

210.6±61.6 228 (150-378) |

296.0±46.2 164 (228-392) |

325.6±70.4 265 (233-498) |

|

| CHO-MR | Pre | 8.8±1.2 2 (7 – 9) |

7.6±0.6 2 (6 – 8) |

373.6±286.7 1007 (122-1129) |

209.1±80.2 277 (118-395) |

299.9±45.2 164 (217-381) |

340.2±132.4 546 (263-809) |

| Mid | 8.3±0.7 2 (7 – 9) |

7.6±0.7 2 (6 – 8) |

197.1±85.9 355 (112-467) |

184.4±62.7 242 (118-360) |

303.1±43.4 140 (236-375) |

308.8±34.3 130 (241-370) |

|

| Post | 8.8±0.6 5 (7 – 12) |

7.7±0.9 4 (6 – 10) |

207.8±86.0 330 (108-438) |

172.5±42.5 167 (117-284) |

280.4±35.9 132 (217-349) |

308.3±41.5 132 (264-396) |

|

ms – milliseconds. RSP: Repeated-sprints protocol. Pre: resting pre RSP, Mid: during the 3-minutes of recovery in-between 2 sets and Post: at post RSP. No significant difference was observed between trials (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated that 10% CHO-MR for 5 s in a fasted state (third day of 3d-IF, composed ~14 h of fasting per day) during the RSP, had no significant effect on physical performance or cognitive function; thus the stated experimental hypothesis is rejected. This running based RSA based data contributes to previous specific observations that CHO-MR (6.4% CHO-MR for 10 to 15 s) following overnight fasting elicits no performance effect during anaerobically biased short duration exercises, including maximal strength and strength endurance exercise [30], and 30 s cycle sprint cycling (6.4% CHO-MR for 5 s [31]). However, such conclusions must be tempered by evidence that CHO-MR may improve high-intensity interval running capacity (1 min at 80% VO2 max interspersed with 1 min walking at 6 km.h-1) in CHO restricted, not fasted, participants [32].

Whilst it appears that CHO-MR may have specific effects dependent upon the participants fed state, with enhanced performance effects during cycling exercise (subjects were asked to maintain their highest sustainable average power output within the 60 min) when athletes were in a fasted as opposed to fed state [6]. It is important to note that CHO-MR exercise performance evidence is skewed to non-fasted [9, 12, 33] rather than fasted [4, 34] endurance exercise experimental designs. Consequently, it is difficult to critically compare the present fasted RSP data (5 min total exercise duration; 2 x 5 x 5 s maximal effort sprints = 100 s sprinting) to fasted experimental designs involving ~60 min endurance exercise [4, 6, 9]. Therefore, whilst CHO-MR is mechanistically capable of stimulating reward and/or motivation centers in the brain [12], this stimulus was insufficient to influence the cognitive and physical performance outcome variables employed within the present design. It is plausible that there is a lag time between MR and the activation of the required brain regions (‘mouth-to-muscle’ hypothesis) which when observed elsewhere has been suggested to underpin enhanced mean power in an ~1 h high-intensity time trial [12, 33]. Such a lag time may underpin the null experimental findings within the present design, however specific deductive experimental designs are required to provide empirical evidence in this regard.

To our knowledge this experiment is the first to determine the effect of repeated 10% CHO-MR on cognitive performance in a fasted state during and after RS exercise. The present data demonstrates CHO-MR (5 s before each sprint) does not influence RTI tasks. This supports other data [35] whereby 5 s of 6% CHO-MR solution was administered following an overnight fast, which failed to elicit improvement in a 20 min continuous performance task (a cognitive test requiring sustained attention, working memory, response time, and error monitoring for 20 min) at rest. Whilst significant increases in the excitability of the corticomotor pathway have been shown in response to CHO-MR (10%) for 15 to 60 s where participants fasted for 12 h overnight [36,37]. Increased brain activity such as this (orbitofrontal) in response to 6.4% CHO-MR for 20 s failed to enhance reaction time within fed participants at rest [10]. Whilst the fed or fasted state of the participants [6], and the CHO rinse concentration [5] and duration [7] all have varying efficacy to activate several higher centers [12], this activation often does not elicit improvements in a range of cognitive processes [10]; with such effects complicated by the presence and proximity of various exercise modalities [9]. Deductive experimental designs are therefore required to precisely characterize the dose response of various CHO-MR strategies, in fed and fasted states, and subsequent mechanistically underpinned effects on physical and cognitive performance. The use of EEG may provide valuable insights into the precise oropharyngeal receptors and subsequent mechanisms of activation of brain regions implicated within CHO-MR. However, with specificity to the presented RSA based experimental design, EEG utilization is challenging relative to brief very intense exercise bouts.

In this study, the expectorated volume per MR was similar in both CHO-MR [range: 3.1 (8.33 – 11.43 )] and PLA-MR [range: 1.98 (9.14 – 11.12)], as shown elsewhere [38]. This suggests a small amount of the MR solution was retained within the mouth. Whether this retained solution is exhaled during participant raised ventilation during exercise and/or swallowed cannot be determined by the present design. However, across the 20 MR procedures (CHO-MR and PLA-MR across SET1 and SET2) performed, 3 participants reported having been aware of inadvertently swallowing small quantities of solution. Although this represents only ~1.5% of the total MR procedures, it is an important consideration for participants fasting for religious reasons. An overt experimental limitation is that it is practically impossible to blind the participant to the fact that they were (i) fasting without mouth rinsing (MR) or (ii) fasting with MR. Therefore, although the presented data must be interpreted carefully relative to the above experimental limitations, the null experimental findings make it unlikely that that these limitations confounded the main findings of this research project.

CONCLUSIONS

CHO-MR (5 s, 10% CHO, 10 mL) in a fasted state (abstaining from food and fluid 14 h per day) did not affect physical (RSP) or cognitive (RTI) performance during the RSP. The lack of experimental effect may be due to insufficient stimulation (volume and duration of MR) of the implicated oral receptors.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the cooperation and participation of all of our participants in this physically demanding study.

Conflicts of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this manuscript. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The authors declare that they do not have anything to disclose regarding funding with respect to this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cherif A, Roelands B, Meeusen R, Chamari K. Effects of Intermittent Fasting, Caloric Restriction, and Ramadan Intermittent Fasting on Cognitive Performance at Rest and During Exercise in Adults. Sports Med. 2016;46(1):35–47. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0408-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tian HH, Aziz AR, Png W, Wahid MF, Yeo D, Constance Png AL. Effects of fasting during Ramadan month on cognitive function in muslim athletes. Asian J Sports Med. 2011;2(3):145–53. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.34753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reilly T, Waterhouse J. Altered sleep-wake cycles and food intake: the Ramadan model. Physiol Behav. 2007;90(2-3):219–28. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Che Muhamed AM, Mohamed NG, Ismail N, Aziz AR, Singh R. Mouth rinsing improves cycling endurance performance during Ramadan fasting in a hot humid environment. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39(4):458–64. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2013-0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Ataide e Silva T, Di Cavalcanti Alves de Souza ME, de Amorim JF, Stathis CG, Leandro CG, Lima-Silva AE. Can carbohydrate mouth rinse improve performance during exercise? A systematic review. Nutrients. 2014;6(1):1–10. doi: 10.3390/nu6010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lane SC, Bird SR, Burke LM, Hawley JA. Effect of a carbohydrate mouth rinse on simulated cycling time-trial performance commenced in a fed or fasted state. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013;38(2):134–9. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2012-0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinclair J, Bottoms L, Flynn C, Bradley E, Alexander G, McCullagh S, et al. The effect of different durations of carbohydrate mouth rinse on cycling performance. Eur J Sport Sci. 2014;14(3):259–64. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2013.785599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kulaksiz TN, Kosar SN, Bulut S, Guzel Y, Willems ME, Hazir T, et al. Mouth Rinsing with Maltodextrin Solutions Fails to Improve Time Trial Endurance Cycling Performance in Recreational Athletes. Nutrients. 2016;8(5) doi: 10.3390/nu8050269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter JM, Jeukendrup AE, Jones DA. The effect of carbohydrate mouth rinse on 1-h cycle time trial performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(12):2107–11. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000147585.65709.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Pauw K, Roelands B, Knaepen K, Polfliet M, Stiens J, Meeusen R. Effects of caffeine and maltodextrin mouth rinsing on P300, brain imaging, and cognitive performance. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2015;118(6):776–82. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01050.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bortolotti H, Pereira LA, Oliveira RS, Cyrino ES, Altimari LR. Carbohydrate mouth rinse does not improve repeated sprint performance. Rev. Bras. Cineantropom. Desempenho Hum. 2013;15:6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chambers ES, Bridge MW, Jones DA. Carbohydrate sensing in the human mouth: effects on exercise performance and brain activity. J Physiol. 2009;587(Pt 8):1779–94. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.164285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillips SM, Findlay S, Kavaliauskas M, Grant MC. The Influence of Serial Carbohydrate Mouth Rinsing on Power Output during a Cycle Sprint. J Sports Sci Med. 2014;13(2):252–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bishop D, Girard O, Mendez-Villanueva A. Repeated-sprint ability - part II: recommendations for training. Sports Med. 2011;41(9):741–56. doi: 10.2165/11590560-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ataide-Silva T, Ghiarone T, Bertuzzi R, Stathis CG, Leandro CG, Lima-Silva AE. CHO Mouth Rinse Ameliorates Neuromuscular Response with Lower Endogenous CHO Stores. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(9):1810–20. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor L, Fitch N, Castle P, Watkins S, Aldous J, Sculthorpe N, et al. Exposure to hot and cold environmental conditions does not affect the decision making ability of soccer referees following an intermittent sprint protocol. Front Physiol. 2014;5:185. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watkins SL, Castle P, Mauger AR, Sculthorpe N, Fitch N, Aldous J, et al. The effect of different environmental conditions on the decision-making performance of soccer goal line officials. Res Sports Med. 2014;22(4):425–37. doi: 10.1080/15438627.2014.948624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Racinais S, Gaoua N, Grantham J. Hyperthermia impairs short-term memory and peripheral motor drive transmission. J Physiol. 2008;586(19):4751–62. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.157420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morin JB, Tomazin K, Samozino P, Edouard P, Millet GY. High-intensity sprint fatigue does not alter constant-submaximal velocity running mechanics and spring-mass behavior. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(4):1419–28. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morin JB, Dupuy J, Samozino P. Performance and fatigue during repeated sprints: what is the appropriate sprint dose? J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(7):1918–24. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e075a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morin JB, Samozino P, Bonnefoy R, Edouard P, Belli A. Direct measurement of power during one single sprint on treadmill. J Biomech. 2010;43(10):1970–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williamson MA, Snyder LM. Wallach’s Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests. 9th ed 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hooper SL, Mackinnon LT. Monitoring overtraining in athletes. Recommendations. Sports Med. 1995;20(5):321–7. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199520050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cherif A, Meeusen R, Farooq A, Ryu J, Fenneni MA, Nikolovski Z, et al. Three Days of Intermittent Fasting: Repeated-Sprint Performance Decreased by Vertical Stiffness Impairment. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017;12(3):287–294. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2016-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14(5):377–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Backhouse SH, Biddle SJ, Bishop NC, Williams C. Caffeine ingestion, affect and perceived exertion during prolonged cycling. Appetite. 2011;57(1):247–52. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.05.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sahakian BJ, Owen AM. Computerized assessment in neuropsychiatry using CANTAB: discussion paper. J R Soc Med. 1992;85(7):399–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cherif A, Meeusen R, Farooq A, Briki W, Fenneni MA, Chamari K, et al. Repeated Sprints in Fasted State Impair Reaction Time Performance. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017;36(3):210–217. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2016.1256795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Painelli VS, Roschel H, Gualano B, Del-Favero S, Benatti FB, Ugrinowitsch C, et al. The effect of carbohydrate mouth rinse on maximal strength and strength endurance. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(9):2381–6. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-1865-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chong E, Guelfi KJ, Fournier PA. Effect of a carbohydrate mouth rinse on maximal sprint performance in competitive male cyclists. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(2):162–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasper AM, Cocking S, Cockayne M, Barnard M, Tench J, Parker L, et al. Carbohydrate mouth rinse and caffeine improves high-intensity interval running capacity when carbohydrate restricted. Eur J Sport Sci. 2016;16(5):560–8. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2015.1041063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pottier A, Bouckaert J, Gilis W, Roels T, Derave W. Mouth rinse but not ingestion of a carbohydrate solution improves 1-h cycle time trial performance. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(1):105–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Velazquez-Brizuela IE, Ortiz GG, Ventura-Castro L, Arias-Merino ED, Pacheco-Moises FP, Macias-Islas MA. Prevalence of Dementia, Emotional State and Physical Performance among Older Adults in the Metropolitan Area of Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2014;2014:387528. doi: 10.1155/2014/387528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar N, Wheaton LA, Snow TK, Millard-Stafford M. Carbohydrate ingestion but not mouth rinse maintains sustained attention when fasted. Physiol Behav. 2016;153:33–9. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Millard-Stafford M, Rosskopf LB, Snow TK, Hinson BT. Water versus carbohydrate-electrolyte ingestion before and during a 15-km run in the heat. Int J Sport Nutr. 1997;7(1):26–38. doi: 10.1123/ijsn.7.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gant N, Stinear CM, Byblow WD. Carbohydrate in the mouth immediately facilitates motor output. Brain Res. 2010;1350:151–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gam S, Guelfi KJ, Fournier PA. Opposition of carbohydrate in a mouth-rinse solution to the detrimental effect of mouth rinsing during cycling time trials. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2013;23(1):48–56. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.23.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]